1. Introduction

In lower limb amputees, especially those with transfemoral amputations, the prosthetic system typically consists of a prosthetic foot, knee, and socket [

1]. Among these components, the prosthetic socket plays a critical role as the interface between the human body and the artificial limb, enabling the transmission of body weight and forces during ambulation [

2]. A well-designed socket aims to optimally distribute load to avoid stress peaks while ensuring safe and comfortable use [

3]. Improper socket fit can lead to excessive stress, piston movement (vertical displacement within the socket), skin irritation, ulceration, and in severe cases, re-amputation [

4,

5]. Therefore, socket design and fabrication are considered the most crucial aspects of the prosthetic manufacturing process [

6].

Modern transfemoral sockets are designed to provide adequate pressure distribution and support during use. However, the fabrication process remains largely manual and qualitative, relying heavily on the experience and skill of certified prosthetists [

7,

8,

9]. The acquisition and transfer of the expertise required to produce a well-fitting socket are time-consuming, posing challenges for training and standardization. To address this, there is growing interest in developing quantitative support systems that can assist less experienced prosthetists by integrating anatomical data and biomechanical modeling into the design process [

10].

The most important parameter for evaluating socket comfort is the contact pressure at the interface between the socket and the residual limb [

11]. Several studies have attempted to measure internal socket pressures using various sensor technologies, including strain gauges, sheet-type sensors, and triaxial force sensors [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. While many of these investigations have focused on transtibial (below-knee) amputees, research targeting transfemoral (above-knee) sockets remains limited. This is partly due to the increased complexity of transfemoral biomechanics, which involve the loss of the knee joint and greater variability in residual limb geometry and soft tissue composition [

20].

Historically, transfemoral sockets have been categorized into two main types: the quadri-lateral (QL) socket and the ischial-ramal containment (IRC) socket [

21]. The QL socket, developed in the 1950s, features a wide mediolateral (M-L) dimension and narrow anteroposterior (A-P) diameter, aiming to stabilize the femur through anterior and posterior walls [

22]. However, its lack of ischial support often leads to abduction of the prosthesis during mid-stance, causing discomfort and lateral instability [

23]. To overcome these limitations, the IRC socket was introduced, incorporating the concept of normal shape–normal alignment (NSNA) to replicate the adduction of the femur seen in the intact limb [

24]. The IRC socket provides enhanced lateral stability by narrowing the M-L dimension and encapsulating the ischium, thereby improving load transfer and reducing unwanted motion [

25].

Finite element method (FEM) has emerged as a powerful tool for analyzing socket–limb interactions, enabling simulation of complex geometries, material properties, and loading conditions [

26]. Numerous FEM studies have modeled the residual limb, yet most have focused on generic soft tissue representations and static loading scenarios, often excluding critical anatomical structures such as the pelvis and ischium [

27]. This omission undermines the accuracy of pressure predictions, particularly in IRC sockets where ischial support is fundamental. Only a few studies have explicitly modeled the pelvis, and among them, only one has successfully predicted peak pressure beneath the ischium in agreement with experimental observations [

28].

Recent advances in soft tissue modeling have improved our understanding of mechanical loads transmitted during socket use and their implications for tissue viability and integrity [

29]. However, experimental validation of transfemoral FEM models remains scarce, with only two studies attempting such verification, both yielding limited predictive accuracy. The challenges of modeling transfemoral limbs include complex tissue composition, difficulty in defining socket design criteria due to variable fat distribution, and instability in simulations involving hyperelastic soft tissue materials.

To address these limitations, we have developed a comprehensive workflow for socket design that combines internal pressure quantification on the residual limb, anatomical and tissue characterization from MRI data, and finite element simulation of socket–limb interactions. This study introduces a hybrid modeling framework that integrates FEM with machine learning–based segmentation to assess interface pressure. By incorporating key anatomical landmarks such as the ischium and validating pressure data experimentally, the framework supports a reproducible and data-driven approach to socket design.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Measurements

2.1.1. Participants

Four adult unilateral transfemoral amputees (one female and three males) participated in this study (

Table 1). All participants were able to ambulate independently without assistive devices while wearing their own prostheses, which were fitted to custom sockets. Prosthetic alignment and socket fitting were verified by a certified and experienced prosthetist prior to data collection. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.1.2. Imaging

To acquire internal tissue information for constructing residual limb models, MRI scans were obtained from all four unilateral transfemoral amputee participants. During imaging, participants were positioned in the supine posture. To minimize deformation of the residual limb due to gravity and contact with the scanner bed, a soft blanket was placed beneath the limb. All scans were performed using a Magnetom Symphony Maestro Class 1.5 T MRI system (SIEMENS, Germany).

MRI data were acquired in the transverse plane with the following parameters: 512 × 512 pixel matrix, pixel size of 0.78 mm, and inter-slice spacing of 1 mm. All participants were scanned without wearing their prosthetic sockets. Additionally, for participants S1 and S2, supplementary scans were conducted while wearing IRC sockets, which had been aligned and fitted by a certified prosthetist prior to imaging.In total, 1,812 MRI slices were collected and used to construct a dataset for machine learning. Prior to model training, image preprocessing was performed, including noise reduction and contrast enhancement to improve tissue boundary clarity.

2.1.3. Pressure Measurement

To validate the pressure values estimated through simulation, direct measurements of socket-induced pressure on the residual limb were conducted by embedding triaxial force sensors (PD3-32-05-015, NITTA Corporation, Japan) into the inner wall of the prosthetic socket. These sensors are capable of resolving force in three directions, including two shear components parallel to the skin surface and one normal stress component perpendicular to it.

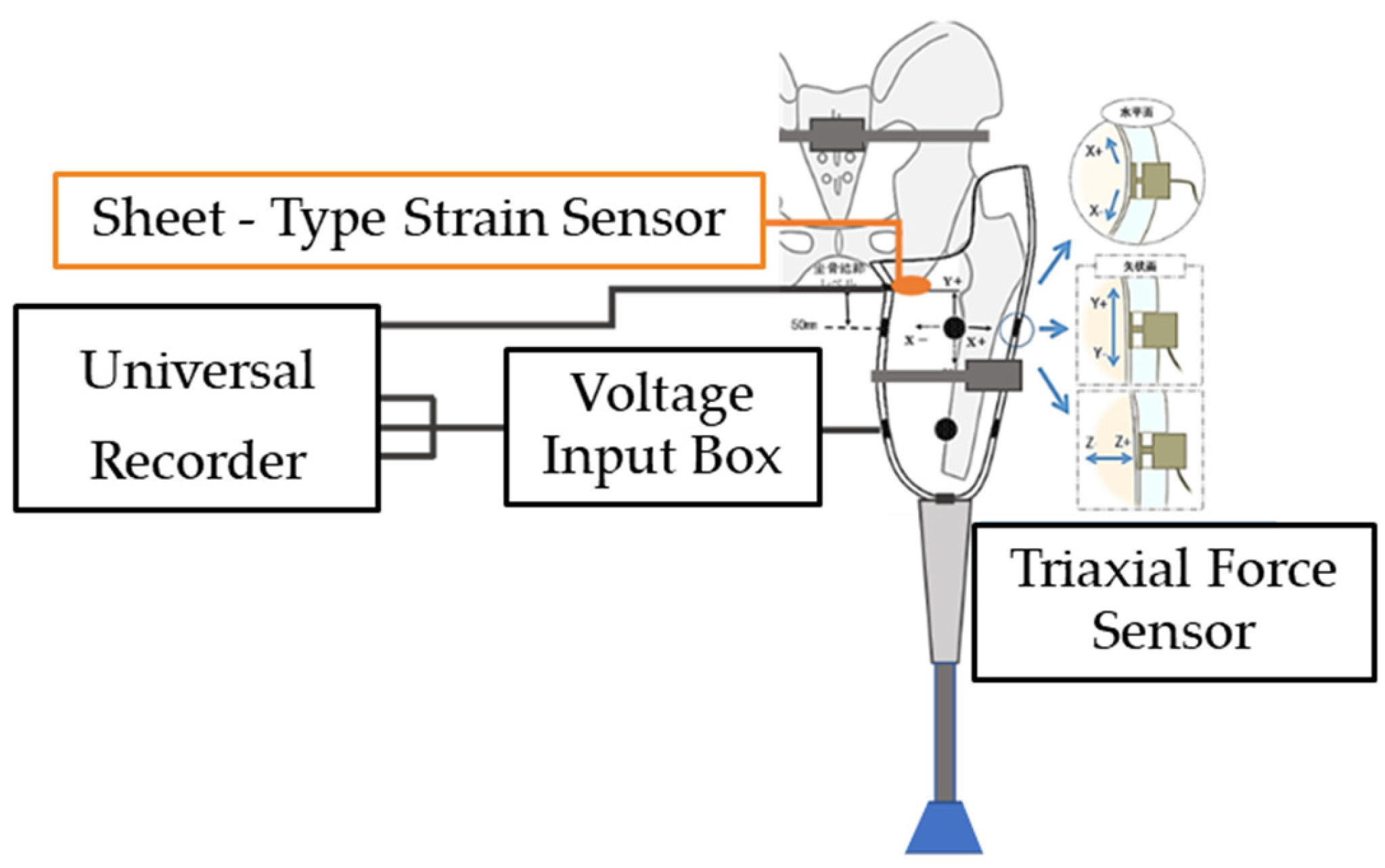

In addition, because embedding a triaxial force sensor directly beneath the ischial tuberosity (IS region) was impractical due to durability and positional constraints, a sheet-type strain sensor (PS-C sensor, Kyowa Electronic Instruments Co., Ltd., Japan) was installed at this location to measure pressure. The system configuration for socket wall pressure measurement is shown in

Figure 1, which also includes the use of a universal recorder (EDX-200A, Nihon Linix Co., Ltd., Japan) and a voltage input box (VI-8A, Kyowa Electronic Instruments Co., Ltd.) for data acquisition.

Although four unilateral transfemoral amputees participated in the imaging phase of this study, pressure measurements were performed on only one participant. This decision was based on practical constraints, including the cost of instrumentation and the physical burden placed on participants during sensor installation and extended data collection.

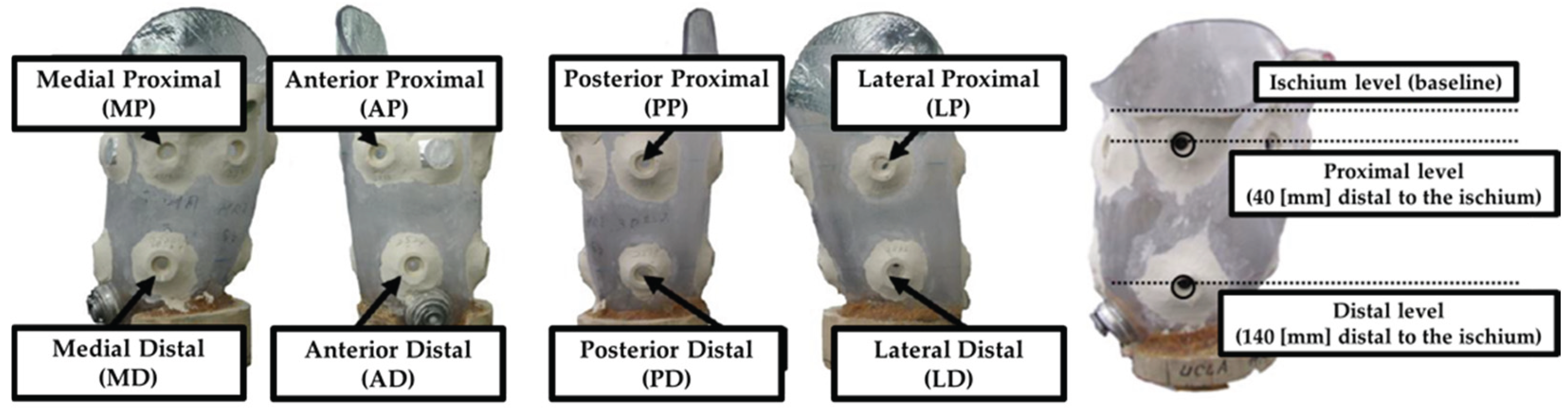

Eight sensors were embedded into the socket: four at the proximal level and four at the distal level, positioned on the anterior, posterior, medial, and lateral surfaces (

Figure 2). The vertical placement of the sensors was referenced to the level of the ischial tuberosity, with the proximal sensors located 40 mm distal to this landmark and the distal sensors placed 140 mm below it.

Each sensor was powered by a 5 V supply and provided triaxial force output. However, since the finite element simulation focused on estimating normal stress (i.e., pressure) acting perpendicular to the tissue surface, only the Z-axis component of the measured data was extracted and analyzed for validation purposes. Pressure measurements were conducted in a quiet standing. This condition was recorded for 15 seconds, and the average pressure over this duration was used as the experimental reference for comparison with simulation-derived values.

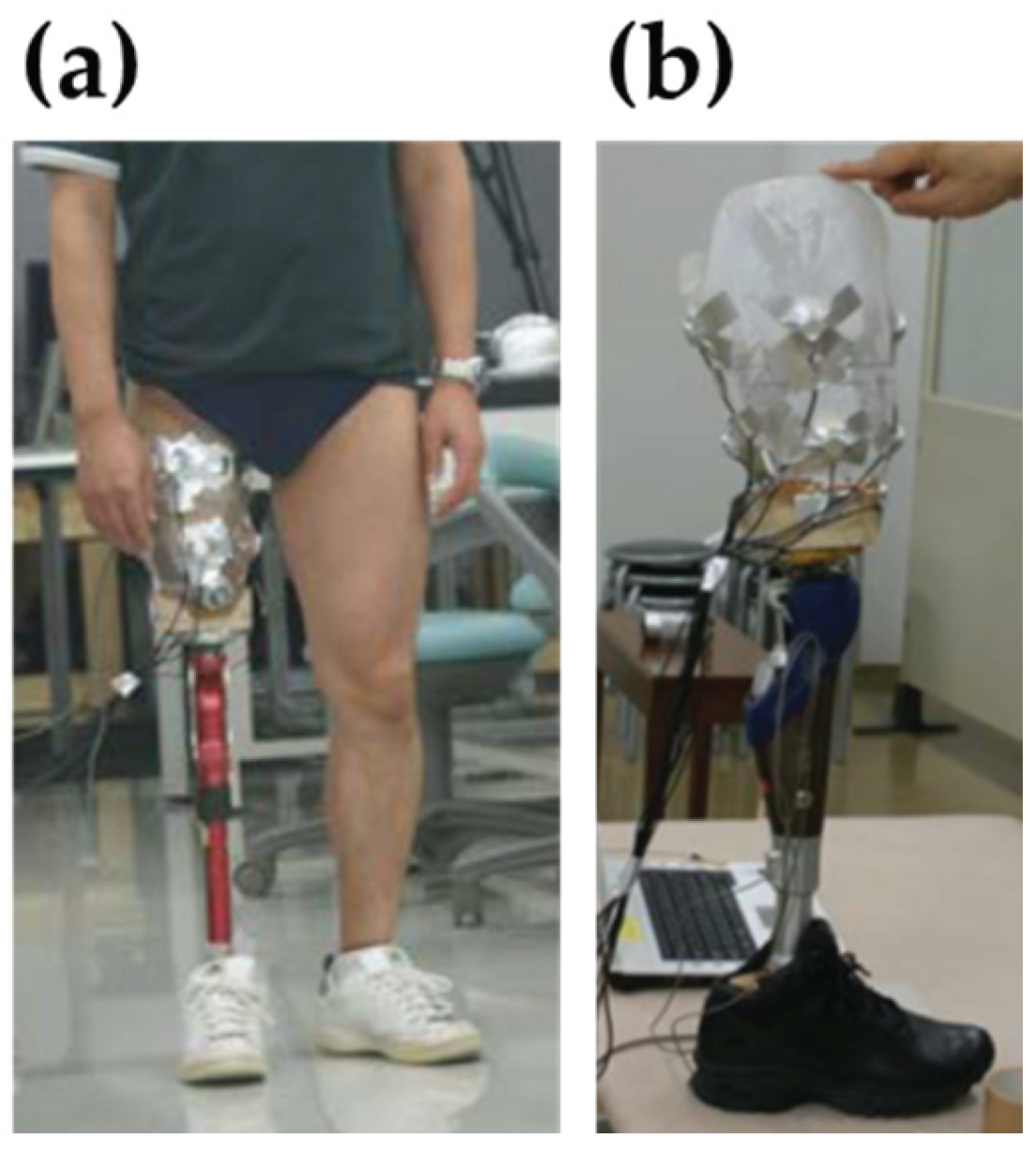

Figure 3 illustrates the pressure measurement setup during quiet standing, along with the prosthetic socket embedded with sensors.

2.2. Image Segmentation

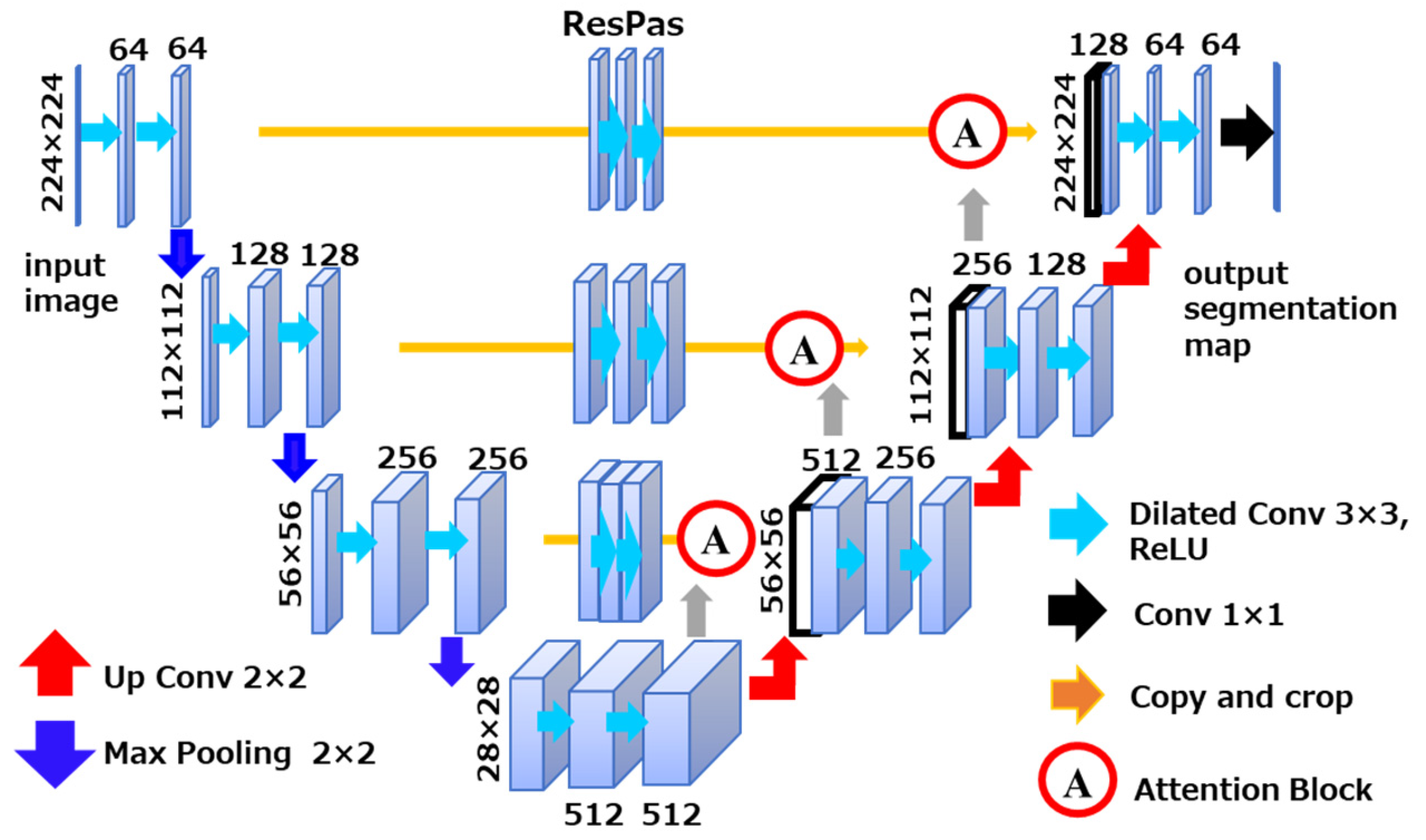

To construct a 3D model of the residual limb from the acquired MRI images, a machine learning–based image segmentation algorithm was developed. The segmentation model was built upon the U-Net architecture, which is widely used for biomedical image segmentation due to its ability to achieve high accuracy even with limited datasets. This characteristic makes it particularly suitable for this study, where the number of available MRI slices was relatively small.

To further enhance segmentation performance, the model was augmented with attention mechanisms and dilated convolutions. The attention mechanism enables the network to selectively focus on spatially relevant features while suppressing less informative regions. This is especially beneficial when dealing with imbalanced datasets such as MRI scans, where certain anatomical structures—like the ischium—appear less frequently compared to adipose tissue or the femur. Without such mechanisms, low-frequency regions are prone to under-segmentation. The inclusion of attention helps mitigate this issue by dynamically weighting feature importance during training.

Additionally, dilated convolutions were incorporated to expand the receptive field of the network, allowing it to capture broader contextual information without increasing the number of parameters. The combined use of attention and dilation within the U-Net framework contributed to improved segmentation accuracy across all tissue types. An overview of the model architecture used for training is shown in

Figure 4.

Model training was conducted on a workstation running Ubuntu 20.04 LTS, equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 SUPER GPU (8 GB VRAM). The segmentation model was implemented using PyTorch 1.9.0 with CUDA 10.2 and Python 3.8.11.

To generate training labels for supervised learning, we employed Efficient Interactive Segmentation (EISeg), a user-guided annotation tool that enables iterative refinement of model predictions. EISeg allows users to correct segmentation outputs and provide feedback, thereby improving model performance through minimal manual intervention. This hybrid approach—combining automated segmentation with targeted user input—facilitated the creation of high-quality annotations across all MRI slices.

Using this method, three anatomical structures—adipose tissue, ischium, and femur—were labeled in each MRI image. Muscle tissue was defined as the region enclosed by adipose tissue but excluding the femur and ischium. This definition was adopted to minimize computational cost and avoid interference between overlapping tissue boundaries during segmentation.

2.3. Finite Element Modeling of the Residual Limb

A finite element (FE) model of the residual limb was constructed based on internal tissue information obtained through machine learning. To extract spatial information from the segmented tissues in the residual limb, MATLAB R2023a (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA) was used. This process generated point cloud data containing spatial coordinates for each segmented tissue within the MRI slices, which served as the basis for subsequent modeling.

However, the segmented MRI images of the residual limb were acquired as horizontal slices, providing only two-dimensional information (X and Y axes). To reconstruct the full three-dimensional geometry, the known slice thickness of 1 mm was utilized to incrementally assign Z-axis coordinates to each slice, starting from the distal end of the residual limb. By stacking the slices in this manner, a complete 3D spatial representation of the residual limb was obtained.

Using the reconstructed 3D data, the FE model of the residual limb was generated in Rhinoceros 8 (Robert McNeel & Associates, Seattle, WA, USA). Prior to modeling, data cleaning was performed to remove outliers and impute missing values resulting from the machine learning-based segmentation process. A mesh was then created from the cleaned point cloud, and smoothing techniques were applied to ensure a continuous and anatomically realistic surface geometry. In addition, the FE model of the transfemoral prosthetic socket was created by scanning a physical socket using a 3D scanner (Eva, Artec Inc.).

2.4. Socket Fitting Simulation Using FEM

To evaluate the pressure exerted on the residual limb during transfemoral prosthetic socket application, simulations were conducted using LS-DYNA (Ansys Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA), a finite element analysis software. LS-DYNA discretizes spatial domains using the finite element method and solves nonlinear problems via an explicit time integration scheme based on central difference. It is capable of handling a wide range of analyses, including dynamic problems such as impact and collision, as well as quasi-static processes such as plastic forming.

The material properties assigned to each tissue in the residual limb model are summarized in

Table 2.

Table 2.

Material properties of FE models.

Table 2.

Material properties of FE models.

| Tissue Type |

Material Model |

Density [kg/m3] |

Young’s Modulus [MPa] |

Poisson’s Ratio |

| Socket [30,31] |

ELASTIC |

1000 |

15000 |

0.3 |

| Ischium, Femur [31,32] |

ELASTIC |

1000 |

12000 |

0.3 |

| Tissue Type |

Material Model |

Density [kg/m3] |

Mooney-Rivlin Material Constants |

Spring Stiffness |

Damper Relaxation Time |

Bulk Modulus |

| C1 [kPa] |

C2 [kPa] |

S1 |

S2 |

T1 [ms] |

T2 [ms] |

K [MPa] |

| Adipose [33,34] |

SOFT_TISSUE_VISCO |

920 |

0.19 |

0.18 |

1 |

0.9 |

10 |

84 |

20 |

Muscle

[34,35] |

SOFT_TISSUE_VISCO |

1060 |

0.12 |

0.25 |

1.2 |

0.8 |

23 |

63 |

20 |

The simulation was divided into two phases: (1) socket application, (2) quiet standing. Each phase was simulated over a duration of 0.1 s to balance computational cost and resolution. The socket was modeled using shell elements, while the adipose tissue, muscle, femur, and ischium were modeled using solid elements. Gravity was applied as a constant acceleration of 9.8 m/s².

During the socket application phase, the socket was displaced proximally by 120 mm through enforced displacement. Frictional contact between the socket and adipose tissue was defined, with a static coefficient of friction of 0.05 and a dynamic coefficient of 0.07. In the quiet standing phase, a proximal load of 308.7 N—representing half of the subject’s body weight—was applied to a single element on the bottom surface of the socket. For quite standing phase, the frictional interaction between the socket and adipose tissue was defined with a static coefficient of 0.20 and a dynamic coefficient of 0.10.

In typical clinical scenarios, when a transfemoral amputee wears a prosthetic socket, the displaced adipose tissue is naturally constrained by the contralateral thigh and perineal structures. However, in this study, the residual limb model was constructed from MRI data of a single limb, and therefore did not include the anatomical boundaries provided by the opposite leg or surrounding soft tissues near the hip joint. As a result, during socket application, the adipose tissue tended to escape medially into the open space, leading to unrealistic deformation and excessive void formation within the socket.

To address this modeling limitation, a constraint condition was applied to the medial soft tissue region near the hip joint. This boundary condition restricted tissue displacement in the XY plane, effectively simulating the anatomical confinement that would be present in a full-body context. This approach prevented the adipose tissue from escaping inward and allowed it to be pushed back into the socket, thereby improving the fidelity of the socket–limb interface and ensuring a more realistic pressure distribution.

Pressure values were extracted at eight sensor locations embedded in the residual limb model, corresponding to the actual measurement points used in physical experiments. These simulated pressure values were then compared with the experimentally measured data to assess the accuracy of the FE model.

3. Results

3.1. Pressure Measurement Results

The pressure values obtained from eight triaxial force sensors embedded in the prosthetic socket are presented in

Table 3. This figure illustrates the distribution of normal stress acting on the residual limb during quiet standing. Negative pressure readings indicate the presence of suction forces at the socket–limb interface, which may suggest the formation of vacuum zones due to localized separation between the socket wall and the residual limb. Such suction forces are considered to contribute to suspension by enhancing adherence at the interface.

Notably, the pressure value recorded at the IS location, situated directly beneath the ischial tuberosity, was substantially higher than those at other measurement points. This deviation is consistent with the structural characteristics of the IRC socket, in which the ischial seat serves as the primary load-bearing region during standing. The elevated pressure at this site reflects concentrated force transmission through the ischium, supporting the intended biomechanical function of the socket design.

3.2. Estimation Results Using Machine Learning

To segment anatomical structures within the residual limb, a machine learning–based approach was employed. This method enabled automated classification of key tissue regions from MRI data, facilitating integration with the finite element model.

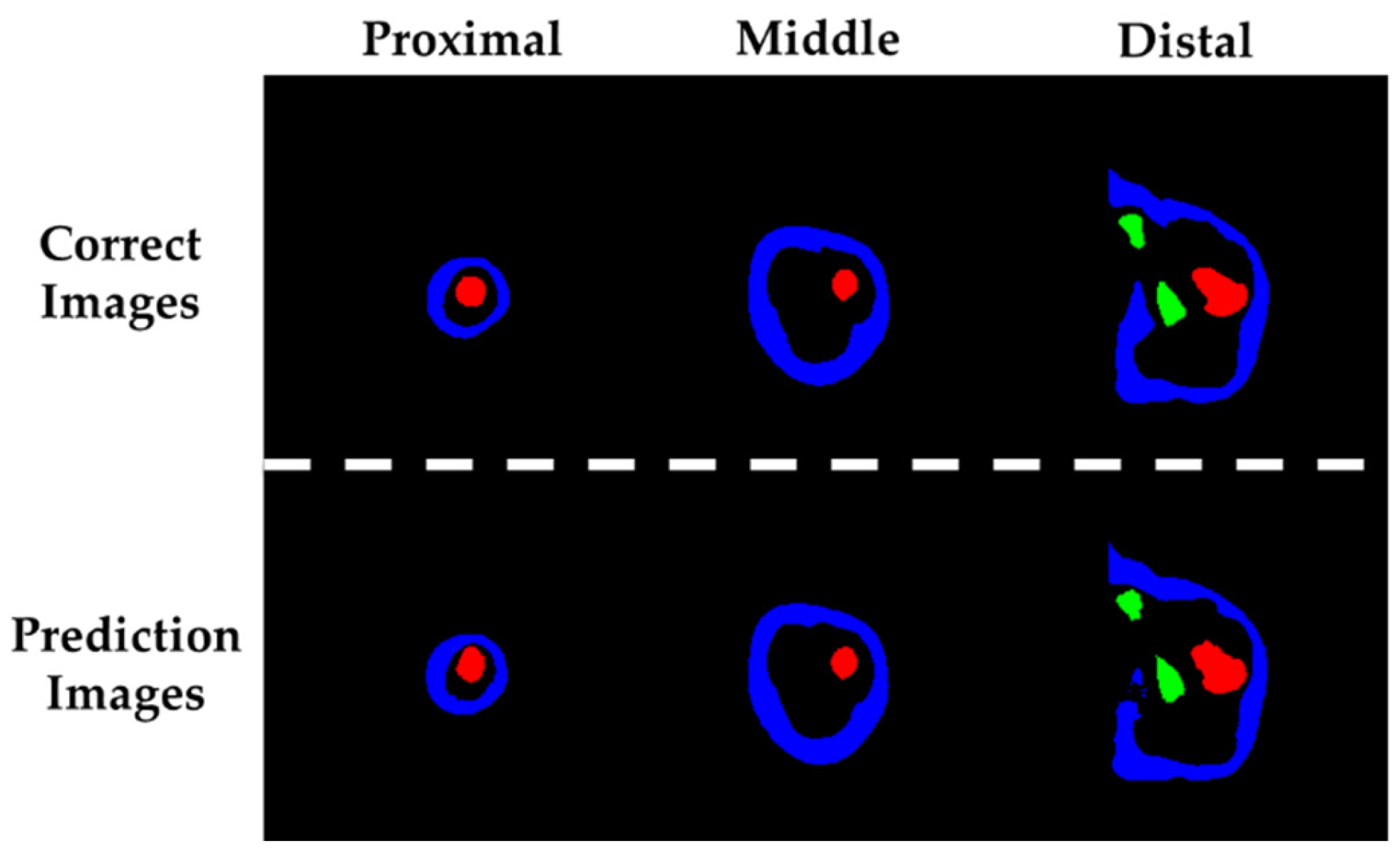

Figure 5 presents the segmentation results of residual limb tissues estimated using machine learning, alongside the corresponding ground truth images used for supervised training. Representative examples from the proximal, middle, and distal regions are shown for both the predicted and reference images. In these images, blue regions indicate adipose tissue, red regions represent the femur, and light green regions correspond to the ischium.

To evaluate the accuracy of the machine learning–based segmentation, a confusion matrix was first constructed to define the classification outcomes, as shown in

Table 4. In this matrix, true positives (TP) represent correctly identified target tissues, while true negatives (TN) correspond to correctly excluded non-target tissues. False positives (FP) and false negatives (FN) denote misclassifications of non-target and target tissues, respectively.

Based on these definitions, the F-measure (also referred to as the F1 score) was employed to assess segmentation performance. This metric is commonly used to evaluate classification models and is defined as the harmonic mean of precision and recall. The calculation methods for precision, recall, and F-measure are provided in Equations (1)–(3). This metric is particularly effective in scenarios involving class imbalance, as it reflects the balance between prediction accuracy and completeness. A higher F-measure indicates that the model successfully identifies true positives while minimizing false detections.

Table 5 summarizes the F-measure values for adipose tissue, femur, and ischium. All scores exceeded 0.85, indicating high segmentation accuracy. Values closer to 1 suggest better performance in tissue classification.

3.3. Finite Element Model of the Fabricated Stump

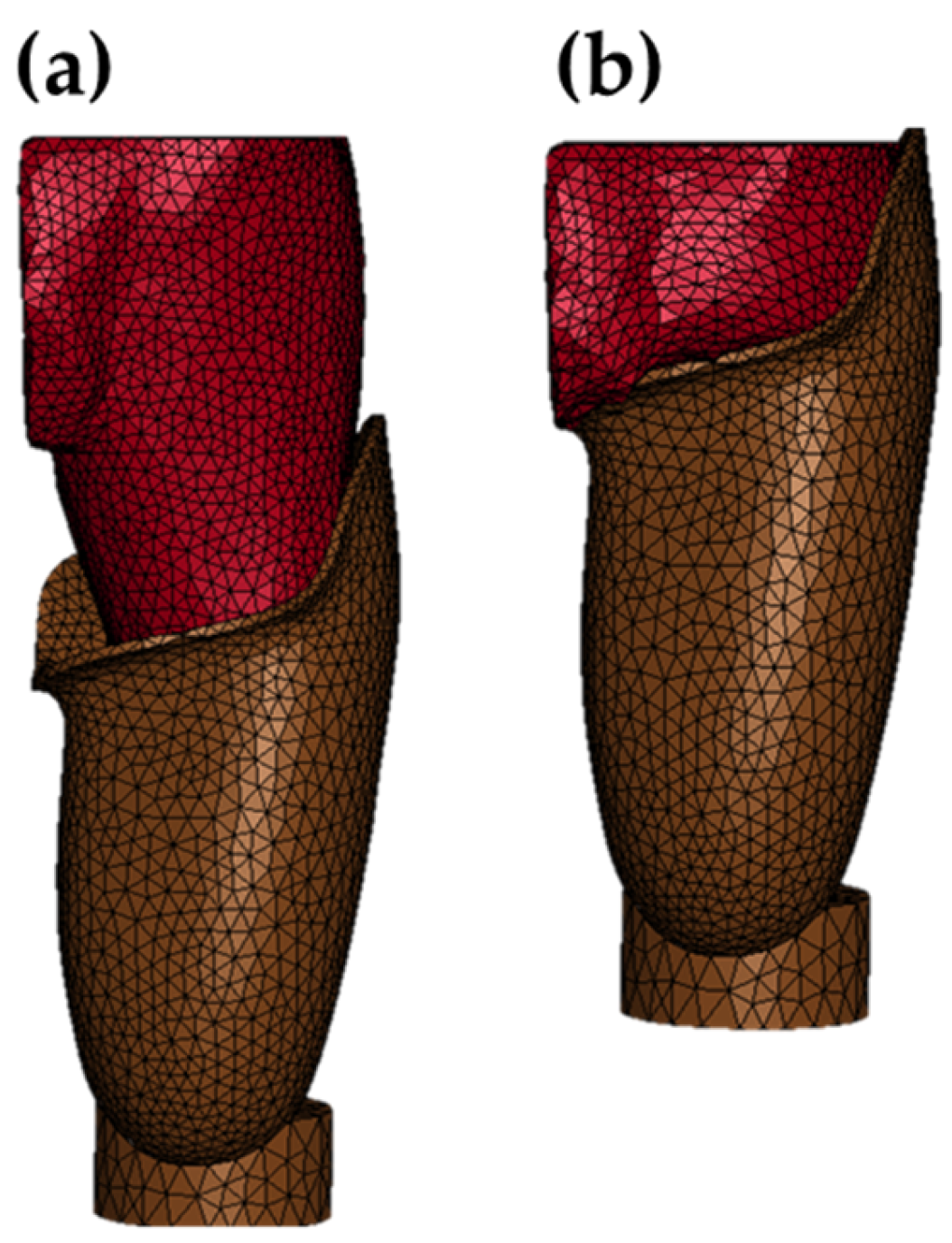

Based on the segmentation results obtained through machine learning, 3D models of the residual limb tissues were constructed, as shown in

Figure 6. The adipose tissue, femur, and ischium models were generated by stacking the spatial coordinates derived from the segmentation output. The prosthetic socket model was created using shape data acquired via a 3D scanner.

The muscle region was defined as the inner volume of the adipose tissue model, excluding the femur and ischium. This differential modeling approach allowed for the generation of a muscle model without direct segmentation, significantly reducing computational cost. Additionally, it prevented initial mesh interference between adjacent tissues such as adipose and muscle. All anatomical and prosthetic components were meshed using tetrahedral elements. The total number of elements across all models was 64,885.

To define the interactions between anatomical components and the prosthetic socket, appropriate contact conditions were assigned within the finite element model. The interface between the socket and the adipose tissue was modeled using CONTACT_AUTOMATIC_SURFACE_TO_SURFACE, which automatically detects and resolves contact between two surfaces. This general-purpose contact definition is well-suited for complex geometries and ensures stable computation during deformation.

For internal tissue interfaces—specifically between adipose tissue and muscle, muscle and femur, and muscle and ischium—CONTACT_TIED_SURFACE_TO_SURFACE was applied. This contact type constrains relative displacement between elements to zero, effectively bonding the components together. By doing so, it prevents interpenetration that may occur with automatic contact definitions, especially under large deformations. This approach ensures that, even when the adipose tissue is dynamically compressed and displaced during socket fitting, the underlying muscle and bone structures remain physically consistent and do not penetrate each other.

3.4. Pressure Values Estimated from FEM Simulations

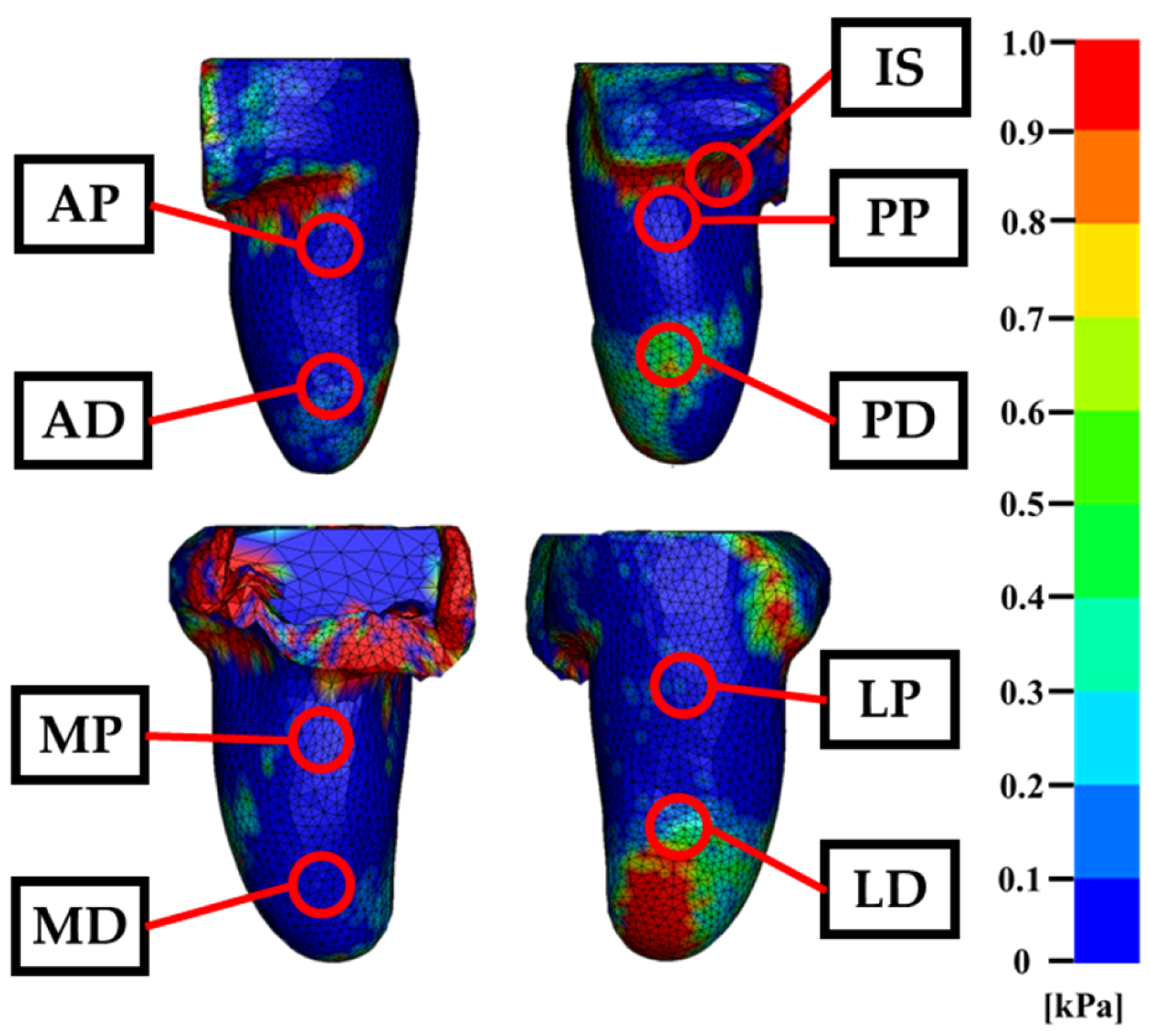

The simulation of socket fitting using the FEM yielded detailed insights into the pressure distribution across the residual limb. As part of this analysis, the overall simulation results are shown in

Figure 7, while the corresponding pressure map is presented in

Figure 8. In this map, red regions indicate areas of concentrated pressure, whereas blue regions represent zones with minimal or negative pressure. In addition, the pressure values estimated by FEM at nine measurement points are summarized in

Table 6. These nine points correspond to the sensor locations used in the experimental measurements.

No element penetration or mesh interference was detected during the socket fitting simulation, indicating that the model successfully reproduced the mechanical behavior of the residual limb under load. The pressure distribution map shown in

Figure 7 reveals a distinct concentration of pressure in the medial region near the hip joint. This phenomenon is attributed to the constraint condition applied to the inner soft tissue boundary, which was introduced to prevent unrealistic medial displacement of adipose tissue—an issue arising from the absence of contralateral anatomical structures in the MRI-based model.

As the socket was applied, displaced soft tissue was redirected toward the constraint surface, resulting in elevated pressure values in that region. In addition to the medial hip area, localized pressure concentrations were observed beneath the ischial tuberosity and along the lateral distal end of the residual limb. Outside these regions, pressure remained relatively low and evenly distributed. These findings suggest that the ischium model functioned effectively as a load-bearing structure, limiting excessive pressure to anatomically appropriate contact zones and contributing to a realistic simulation of socket–limb interaction.

4. Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to establish a quantitative evaluation framework for pressure distribution on the residual limb during transfemoral socket fitting by integrating machine learning–based segmentation with finite element modeling. To validate the accuracy of the FEM-based simulation, pressure measurements were obtained using eight embedded triaxial force sensors positioned along the inner wall of the prosthetic socket, as well as one sheet-type strain sensor placed directly beneath the ischial tuberosity. These experimental values were then compared with the simulated pressure outputs.

In the initial phase, pressure data were successfully acquired from all nine sensor locations. The highest pressure was recorded at the ischial tuberosity (IS) region, reaching 54.873 kPa, while the lowest was observed at the lateral distal (LP) region (−0.967 kPa). All eight measurement points other than the IS region showed values below 1 kPa. This indicates that the majority of load support during quiet standing in the IRC socket is concentrated around the ischial seat.

Furthermore, negative pressure values were observed at three locations—LP, anterior proximal (AP), and medial distal (MD)—suggesting the formation of localized vacuum zones within the socket. This phenomenon is likely attributable to soft tissue deformation during socket application, which may have created voids between the residual limb and the socket wall.

Previous studies have reported similar findings in transtibial prostheses. Schoepp et al. [

36] demonstrated that sockets equipped with mechanical elevated vacuum pumps generated negative internal air pressure during ambulation, confirming that vacuum-assisted suspension can actively produce sub-atmospheric pressure conditions. Beil et al. [

37] further observed that minimum interface pressures fell below zero when comparing suction and vacuum-assisted sockets during walking, highlighting that negative pressure is not only a transient phenomenon but can be consistently measured under dynamic loading. Likewise, Chino et al. [

38] reported negative pressure during the swing phase in below-knee prostheses with sleeve suspension, reinforcing the notion that localized vacuum zones are a reproducible outcome across different suspension strategies. Collectively, these studies support the interpretation that negative pressure can contribute to enhanced adherence between the socket and residual limb, thereby improving suspension and load transfer efficiency.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that all of these prior investigations were conducted in transtibial prostheses, where socket geometry and limb biomechanics differ substantially from transfemoral designs. The IRC transfemoral socket used in the present study has distinct contouring and load-bearing characteristics compared to below-knee sockets, and thus it cannot be conclusively stated that the same mechanisms of negative pressure formation apply. While the observation of localized negative pressure in our measurements aligns with clinical expectations for suction-based suspension systems, further validation is required to determine whether these findings can be generalized across different socket types and amputation levels.

In the subsequent phase of this study, a machine learning–based image processing algorithm was developed to automatically segment internal tissues of the residual limb from MRI scans of a transfemoral amputee. This approach enabled rapid and accurate segmentation of key anatomical structures, specifically the adipose tissue, femur, and ischium. The segmentation performance was quantitatively evaluated using the F-measure, with the femur achieving the highest score of 0.934. This result is likely due to the relatively consistent morphology of the femur across MRI slices, which reduces the complexity of pattern recognition during training. The adipose tissue yielded the second-highest F-measure of 0.925. Although its shape varied more significantly in the proximal region compared to the femur, the large spatial coverage of adipose tissue in the MRI images may have mitigated the impact of local segmentation errors, resulting in stable overall performance. The lowest segmentation accuracy was observed for the ischium, which can be attributed to class imbalance in the training data. In a typical MRI dataset consisting of approximately 300 axial slices at 1 mm intervals, the ischium appears in only about 80 proximal slices. This limited representation, combined with the complex geometry of the ischial region—particularly the hemispherical acetabular cavity—likely contributed to reduced prediction accuracy. Despite these limitations, minor geometric discrepancies in the segmented ischium were corrected during the modeling process, and did not significantly affect the subsequent FEM simulations. Therefore, the machine learning–based segmentation framework demonstrated sufficient reliability for anatomical reconstruction and biomechanical analysis.

In the third phase of the workflow, the segmented tissue data obtained from machine learning were used to construct three-dimensional models for finite element analysis. This process involved extracting two-dimensional spatial coordinates along the X and Y axes from each MRI slice and stacking them to reconstruct the volumetric geometry of the residual limb. During this reconstruction, outlier predictions and irregular contours—often resulting from segmentation noise—were systematically removed. Surface smoothing was applied to eliminate jagged boundaries that could otherwise lead to element stretching, mesh entanglement, or numerical instability during simulation. As a result, anatomically accurate and simulation-ready models of the residual limb tissues were successfully generated. However, due to the lower segmentation accuracy of the ischium, the resulting ischial tuberosity appeared slightly smaller than its actual anatomical counterpart. This discrepancy may have contributed to a marginal underestimation of pressure values in the ischial region during FEM simulation. Nevertheless, the overall geometric fidelity of the reconstructed models was sufficient to preserve the biomechanical behavior of the residual limb under socket loading conditions.

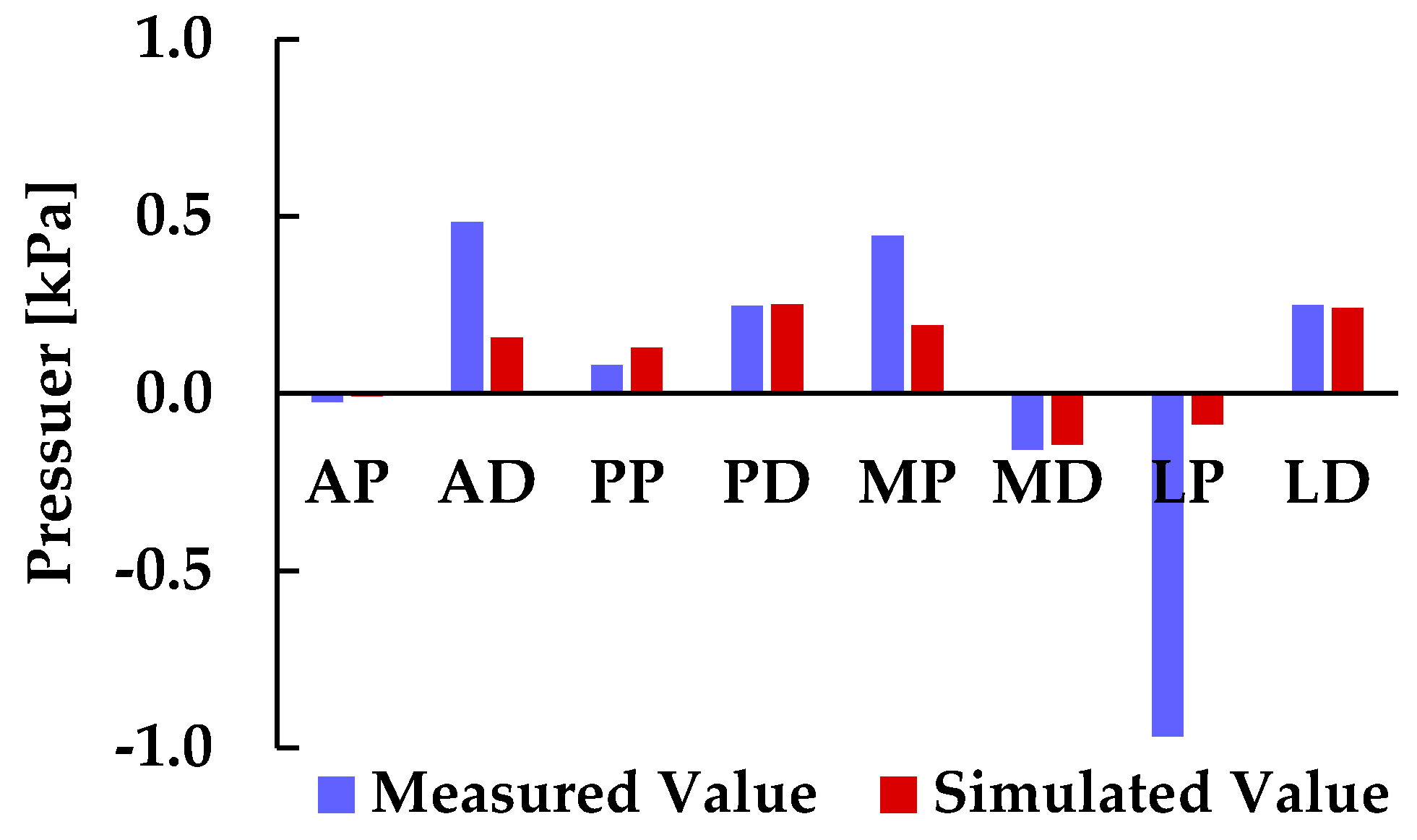

In the final phase of this study, pressure values on the residual limb were quantitatively evaluated using FEM simulations based on 3D anatomical models derived from machine learning segmentation. Simulated pressure data were extracted at nine locations corresponding to the sensor positions used in physical measurements. All simulated values at the eight points other than the ischial tuberosity (IS) region were below 1 kPa, consistent with the trend observed in the experimental data. The highest pressure was recorded at the IS region (21.814 kPa), while the lowest was observed at the medial distal (MD) region (−0.123 kPa). To assess the validity of the FEM-based predictions, a direct comparison was conducted between the simulated pressure values and the experimental measurements obtained from triaxial force sensors embedded in the socket. Because the IS region exhibited markedly higher values compared to the other eight points, pressure comparison between simulation and measurement was performed excluding the IS region, as shown in

Figure 9. Across all eight evaluation points, the sign (positive or negative) of pressure values matched, demonstrating a high degree of consistency between simulation and measurement. This agreement supports the reliability of the FEM-based approach for estimating socket–limb interface pressure. Notably, regions with positive pressure values showed close numerical correspondence between simulated and measured data, particularly near the ischium and pelvis. This suggests that the reconstructed soft tissue geometry in these regions allowed the ischium to function effectively as a load-bearing structure, contributing to realistic pressure patterns.

However, it should be noted that the negative pressure values observed in the FE simulation reflect the sign convention of LS-DYNA, in which compressive stresses are positive and tensile stresses are negative. Conventional FE analysis does not account for fluid–structure interaction; therefore, these values do not directly represent sub-atmospheric air pressure within the socket. Instead, the negative values indicate localized tissue deformation and potential separation at the socket–limb interface. Nevertheless, the significant correlation between simulated and measured pressures suggests that, despite the differing physical interpretations of “negative pressure” in simulation and sensor measurements, the computational framework is capable of capturing clinically relevant interface dynamics.

In addition, a notable discrepancy was observed between the pressure values obtained at the ischial tuberosity (IS) region: the sheet-type strain sensor recorded 54.873 kPa, whereas the FEM simulation yielded 21.814 kPa. This difference may be attributable to the boundary conditions applied to the medial soft tissue near the hip joint, which were introduced to prevent the adipose tissue from escaping toward the contralateral side and to maintain socket adherence. As a result, the constrained medial soft tissue was pressed against the restricted area, leading to concentrated pressure values of approximately 102.623 kPa in the medial region rather than directly beneath the ischium. While such constraints are necessary to avoid unrealistic tissue displacement toward the contralateral side—which was not modeled in this study—they may inadvertently cause excessive pressure concentration on the medial surface. Therefore, future work should explore boundary conditions that limit tissue displacement without imposing complete fixation, thereby preventing undue pressure concentration while preserving realistic socket–limb contact.

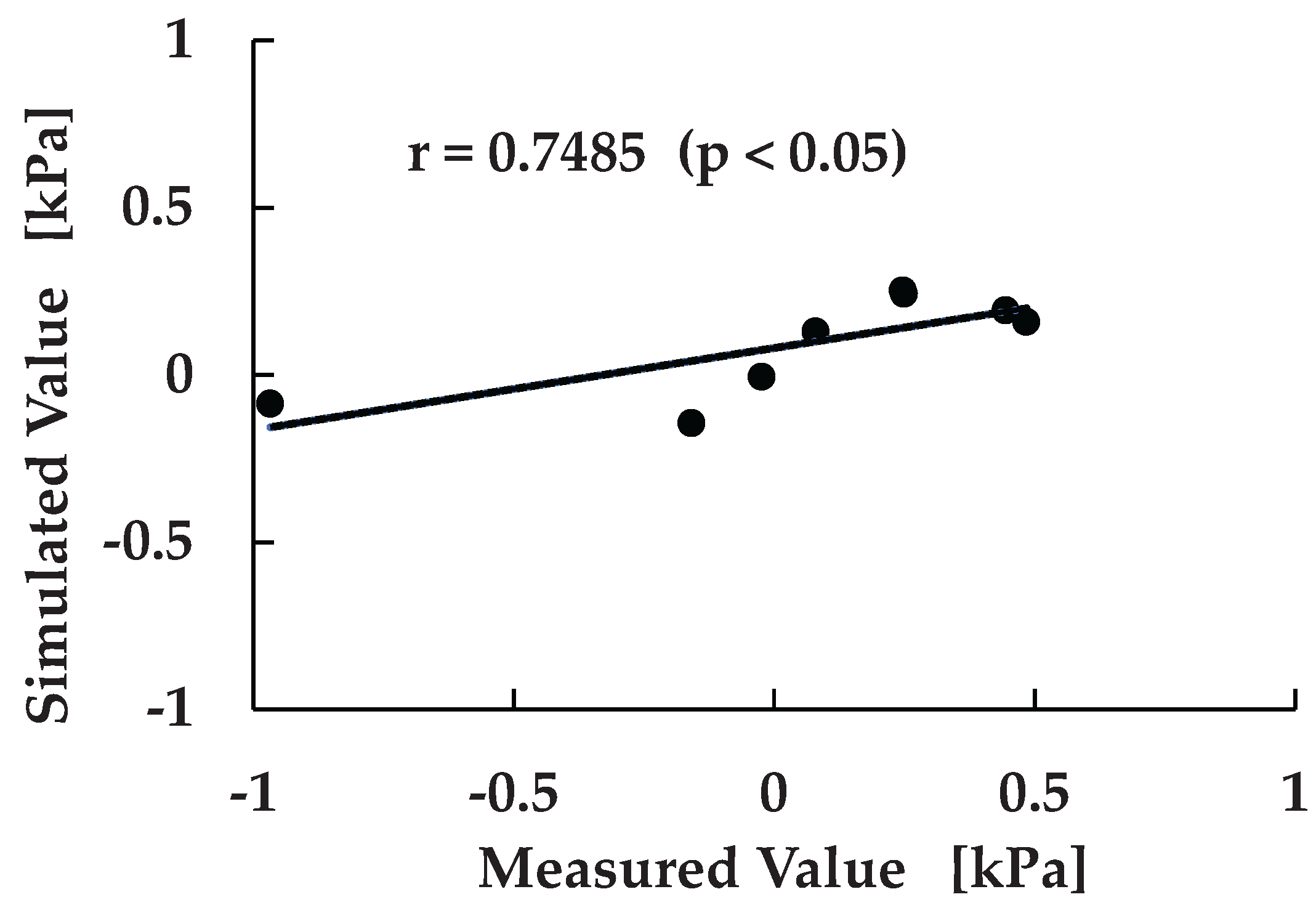

To further evaluate the consistency between experimental measurements and FEM-based predictions, a correlation analysis was conducted. As shown in

Figure 10, similar to

Figure 9, the relationship between measured and simulated pressure values was assessed across eight sensor locations excluding the IS region. This analysis was performed to quantitatively verify the predictive capability of the simulation framework and to identify systematic trends in pressure estimation. The resulting correlation coefficient was r = 0.7485, with a p-value < 0.05, indicating a statistically significant and moderately strong positive correlation between the two datasets.

This finding suggests that, despite localized discrepancies such as those observed at the lateral proximal (LP) region, the simulation model reliably captures the overall pressure distribution pattern. The alignment in both magnitude and polarity across multiple anatomical sites reinforces the validity of the machine learning–driven FEM approach and its potential for clinical application. Moreover, the observed correlation supports the feasibility of using simulation outputs as surrogate indicators for physical measurements, which could reduce the need for extensive sensor instrumentation in future socket design workflows.

The framework presented in this study offers a promising foundation for future developments in personalized prosthetic fitting, enabling efficient, data-driven assessment of socket–limb interaction with minimal manual intervention.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a comprehensive framework for quantitatively evaluating socket–limb interface pressure in transfemoral amputees by integrating machine learning–based MRI segmentation with finite element modeling (FEM). The proposed workflow enabled automated extraction of internal tissue structures, accurate 3D reconstruction of the residual limb, and simulation-based pressure estimation under socket loading conditions. Experimental validation using embedded triaxial force sensors demonstrated that the simulated pressure values were consistent in polarity and magnitude with measured data, particularly in load-bearing regions such as the ischium and pelvis.

While a discrepancy was observed at the ischial tuberosity (IS) region, where the measured and simulated pressure values differed due to the medial boundary conditions applied near the hip joint, the overall agreement between simulation and measurement supports the reliability of the FEM-based approach. Moreover, at the eight sensor locations excluding the IS region, positive pressure values showed close numerical correspondence between simulated and measured data. This indicates that the reconstructed soft tissue geometry in these regions allowed the ischium to function effectively as a load-bearing structure, thereby contributing to realistic pressure patterns that align with clinical expectations.

Taken together, this study highlights the feasibility of using machine learning–driven FEM simulations for personalized prosthetic socket design. The framework offers a scalable and data-driven alternative to manual modeling, with potential applications in clinical assessment, socket optimization, and digital twin development for amputee care.

Author Contributions

R.S. was the principal investigator and contributed to the analysis, data collection, and summarization. S.K. developed the image processing algorithm used for tissue segmentation. Y.A. served as the fabrication leader for the experimental prosthetic socket. K.O. and H.O. contributed to the socket design studies and provided interpretive insights on key biomechanical aspects. H.S. was responsible for experimental pressure measurements. A.H., M.T., and S.Y. contributed to methodological validation, manuscript revision, and approval of the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Shibaura Institute of Technology (approval code: 25-016, date of approval: 7 May 2025) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon reasonable request to authors.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used Microsoft Copilot for language and grammar improvement. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FEM |

Finite Element Method |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| LS-DYNA |

Livermore Software Dynamic Nonlinear Analysis |

| AP |

Anterior Proximal |

| AD |

Anterior Distal |

| PP |

Posterior Proximal |

| PD |

Posterior Distal |

| MP |

Medial Proximal |

| MD |

Medial Distal |

| LP |

Lateral Proximal |

| LD |

Lateral Distal |

References

- Henao, S.C.; Orozco, C.; Ramírez, J. Influence of Gait Cycle Loads on Stress Distribution at the Residual Limb/Socket Interface of Transfemoral Amputees: A Finite Element Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4985. [CrossRef]

- Brodie, M.; Murray, L.; McGarry, A. Transfemoral Prosthetic Socket Designs: A Review of the Literature. J. Prosthet. Orthot. 2021, 34, e73–e92. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, G.; Comotti, C.; Redaelli, D.F.; Regazzoni, D.; Rizzi, C.; Vitali, A. A Method to Improve Prosthesis Leg Design Based on Pressure Analysis at the Socket-Residual Limb Interface. In Proceedings of the ASME 2016 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (IDETC/CIE), Charlotte, NC, USA, 21–24 August 2016; Paper No: DETC2016-60131; V01AT02A068. [CrossRef]

- Reiber, G.E. Who Is at Risk of Limb Loss and What to Do about It? J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 1994, 31, 357–362.

- Dou, P.; Jia, X.; Suo, S.; Wang, R.; Zhang, M. Pressure Distribution at the Stump/Socket Interface in Transtibial Amputees during Walking on Stairs, Slope and Non-Flat Road. Clin. Biomech. 2006, 21, 1067–1073. [CrossRef]

- Vitali, A.; Regazzoni, D.; Rizzi, C.; Colombo, G. Design and Additive Manufacturing of Lower Limb Prosthetic Socket. In Proceedings of the ASME 2017 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition (IMECE), Tampa, FL, USA, 3–9 November 2017. [CrossRef]

- Górski, F.; Wichniarek, R.; Kuczko, W.; Żukowska, M. Study on Properties of Automatically Designed 3D-Printed Customized Prosthetic Sockets. Materials 2021, 14, 5240. [CrossRef]

- Tiesler, L.M.; Edel, M.; Wang, F.; Pieroh, P.; Drossel, W.-G.; Carabello, A.; Zipplies, D.; Heyde, C.-E.; Schleifenbaum, S. Objective Measurement Methods for the Evaluation of Socket Comfort in Patients with Transfemoral Amputation: A Systematic Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1576729. [CrossRef]

- Binedell, T.; Subburaj, K.; Wong, Y.; Blessing, L.T.M. Leveraging Digital Technology to Overcome Barriers in the Prosthetic and Orthotic Industry: Evaluation of Its Applicability and Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2020, 7, e23827. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, G.; Comotti, C.; Redaelli, D.F.; Regazzoni, D.; Rizzi, C.; Vitali, A. A Method to Improve Prosthesis Leg Design Based on Pressure Analysis at the Socket-Residual Limb Interface. In Proceedings of the ASME 2016 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (IDETC/CIE), Charlotte, NC, USA, 21–24 August 2016; Paper No: DETC2016-60131; V01AT02A068. [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.C.; Zhang, M.; Mak, A.F. Regional Differences in Pain Threshold and Tolerance of the Transtibial Residual Limb: Including the Effects of Age and Interface Material. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005, 86, 641–649. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.E.; Zachariah, S.G.; Jacobsen, A.K.; Fergason, J.R. Changes in Interface Pressures and Shear Stresses over Time on Trans-Tibial Amputee Subjects Ambulating with Prosthetic Limbs: Comparison of Diurnal and Six-Month Differences. J. Biomech. 2005, 38(8), 1566–1573. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.E.; Daly, C.H. Measurement of Stresses in Three Orthogonal Directions at the Residual Limb–Prosthetic Socket Interface. IEEE Trans. Rehabil. Eng. 1993, 1(2), 79–85. [CrossRef]

- Zachariah, S.G.; Sanders, J.E. Finite Element Estimates of Interface Stress in the Trans-Tibial Prosthesis Using Gap Elements Are Different from Those Using Automated Contact. J. Biomech. 2000, 33(7), 895–899. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Turner-Smith, A.R.; Tanner, A.; Roberts, V.C. Clinical Investigation of the Pressure and Shear Stress on the Transtibial Stump with a Prosthesis. Med. Eng. Phys. 1998, 20(3), 188–198. [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.-Z.; Lee, W.C.C.; Zhang, M. A Numerical Approach to Evaluate the Fatigue Life of Monolimb. Med. Eng. Phys. 2006, 28(3), 290–296. [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.C.C.; Zhang, M. Design of Monolimb Using Finite Element Modelling and Statistics-Based Taguchi Method. Clin. Biomech. 2005, 20(7), 759–766. [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, G.; Mitrogiannis, C.; Nianios, G.; Fiedler, G. Assessment of Amputee Socket–Stump–Residual Bone Kinematics during Strenuous Activities Using Dynamic Roentgen Stereogrammetric Analysis. J. Biomech. 2010, 43(5), 871–878. [CrossRef]

- Faustini, M.C.; Neptune, R.R.; Crawford, R.H. The Quasi-Static Response of Compliant Prosthetic Sockets for Transtibial Amputees Using Finite Element Methods. Med. Eng. Phys. 2006, 28(2), 114–121. [CrossRef]

- Messaad, T.; Baltach, A.; Zagane, M.E.S.; Boudjemaa, I.; Messaad, M. Biomechanical Analysis of Prosthetic Liners in Transfemoral Amputees Using Finite Element Modeling. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2025, 47, 59. [CrossRef]

- Devinuwara, K.; Dworak-Kula, A.; O’Connor, R.J. Rehabilitation and Prosthetics Post-Amputation. Orthop. Trauma 2018, 32(4), 234–240. [CrossRef]

- Radcliffe, C.W. Functional Considerations in the Fitting of Above-Knee Prostheses. Artif. Limbs 1955, 2(1), 35–60.

- Lehneis, H.R. Beyond the Quadrilateral. Clin. Prosthet. Orthot. 1985, 9(4), 6–8.

- Hachisuka, K.; Umezu, Y.; Ogata, H.; Ohmine, S.; Shinkoda, K.; Arizono, H. Subjective Evaluations and Objective Measurements of the Ischial-Ramal Containment Prosthesis. J. UOEH 1999, 21(2), 107–118. [CrossRef]

- Hachisuka, K.; Arizono, H.; Ogata, H.; Ohmine, S.; Shinkoda, K. Clinical Indication of the Ischial-Ramal Containment Socket for the Above-Knee Amputation. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2000, 24(2), 97–102. [CrossRef]

- Behforootan, S.; Chatzistergos, P.; Naemi, R.; Chockalingam, N. Finite Element Modelling of the Foot for Clinical Application: A Systematic Review. Med. Eng. Phys. 2017, 39, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- van Heesewijk, A.; Crocombe, A.; Cirovic, S.; Taylor, M.; Xu, W. Evaluating the Effect of Changes in Bone Geometry on the Trans-Femoral Socket–Residual Limb Interface Using Finite Element Analysis. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering, Prague, Czech Republic, 3–8 June 2018; IFMBE Proceedings, Volume 68/2; pp. 587–591. [CrossRef]

- Fougeron, N.; Rohan, P.-Y.; Rose, J.-L.; Bonnet, X.; Pillet, H. Finite Element Analysis of the Stump–Ischial Containment Socket Interaction: A Technical Note. Med. Eng. Phys. 2022, 105, 103829. [CrossRef]

- Young, P.R.; Hebert, J.S.; Marasco, P.D.; Carey, J.P.; Schofield, J.S. Advances in the Measurement of Prosthetic Socket Interface Mechanics: A Review of Technology, Techniques, and a 20-Year Update. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2023, 20(9), 729–739. [CrossRef]

- Surapureddy, R. Predicting Pressure Distribution Between Transfemoral Prosthetic Socket and Residual Limb Using Finite Element Analysis. Master’s Thesis, University of North Florida, Jacksonville, FL, USA, 2014.

- Ramasamy, E.; Avci, O.; Dorow, B.; Chong, S.Y.; Gizzi, L.; Steidle, G.; Schick, F.; Röhrle, O. An Efficient Modelling-Simulation-Analysis Workflow to Investigate Stump-Socket Interaction Using Patient-Specific, Three-Dimensional, Continuum-Mechanical, Finite Element Residual Limb Models. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 126. [CrossRef]

- Steer, J.W.; Worsley, P.R.; Browne, M.; Dickinson, A.S. Predictive Prosthetic Socket Design: Part 1—Population-Based Evaluation of Transtibial Prosthetic Sockets by FEA-Driven Surrogate Modelling. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2020, 19, 1331–1346. [CrossRef]

- Al-Dirini, R.M.A.; Reed, M.P.; Hu, J.; Thewlis, D. Development and Validation of a High Anatomical Fidelity FE Model for the Buttock and Thigh of a Seated Individual. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 44, 2805–2816. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Deng, B. Characterization of the Lower Limb Soft Tissues in Pedestrian Finite Element Models. In Proceedings of the 2005 International Research Council on the Biomechanics of Injury (IRCOBI), Prague, Czech Republic, 21–23 September 2005.

- Hedenstierna, S.; Halldin, P.; Brolin, K. Evaluation of a Combination of Continuum and Truss Finite Elements in a Model of Passive and Active Muscle Tissue. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 2008, 11, 627–639. [CrossRef]

- Schoepp, K.R.; Schofield, J.S.; Home, D.; Dawson, M.R.; Lou, E.; Keri, M.; Marasco, P.D.; Hebert, J.S. Real-time monitoring of transtibial elevated vacuum prostheses: A case series on socket air pressure. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2020, 44(5), 356–364. [CrossRef]

- Beil, T.L.; Street, G.M.; Covey, S.J. Interface pressures during ambulation using suction and vacuum-assisted prosthetic sockets. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2002, 39(6), 693–700.

- Chino, N.; Pearson, J.R.; Cockrell, J.L. Negative pressure during swing phase in below-knee prostheses with rubber sleeve suspension. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1975, 56(1), 22–26.

Figure 1.

System configuration for measuring pressure on the prosthetic socket wall.

Figure 1.

System configuration for measuring pressure on the prosthetic socket wall.

Figure 2.

Pressure measurement points by sensors. Eight triaxial force sensors were embedded in the inner wall of the prosthetic socket to measure pressure at specific anatomical locations: Medial Proximal (MP), Medial Distal (MD), Anterior Proximal (AP), Anterior Distal (AD), Posterior Proximal (PP), Posterior Distal (PD), Lateral Proximal (LP), and Lateral Distal (LD).

Figure 2.

Pressure measurement points by sensors. Eight triaxial force sensors were embedded in the inner wall of the prosthetic socket to measure pressure at specific anatomical locations: Medial Proximal (MP), Medial Distal (MD), Anterior Proximal (AP), Anterior Distal (AD), Posterior Proximal (PP), Posterior Distal (PD), Lateral Proximal (LP), and Lateral Distal (LD).

Figure 3.

Overview of the experimental pressure measurement setup used for validation: (a) Measurement configuration during quiet standing, showing the participant wearing the instrumented prosthetic socket. (b) Close-up view of the prosthetic socket with embedded triaxial force sensors and associated wiring components.

Figure 3.

Overview of the experimental pressure measurement setup used for validation: (a) Measurement configuration during quiet standing, showing the participant wearing the instrumented prosthetic socket. (b) Close-up view of the prosthetic socket with embedded triaxial force sensors and associated wiring components.

Figure 4.

Overview of the segmentation architecture used for model training. The model is based on U-Net and incorporates attention mechanisms to focus on relevant features in imbalanced MRI data. Dilated convolutions are used to expand the receptive field and improve segmentation accuracy.

Figure 4.

Overview of the segmentation architecture used for model training. The model is based on U-Net and incorporates attention mechanisms to focus on relevant features in imbalanced MRI data. Dilated convolutions are used to expand the receptive field and improve segmentation accuracy.

Figure 5.

Comparison between machine learning–based tissue segmentation and ground truth labels.

Figure 5.

Comparison between machine learning–based tissue segmentation and ground truth labels.

Figure 6.

3D models of residual limb and socket for finite element analysis.

Figure 6.

3D models of residual limb and socket for finite element analysis.

Figure 7.

Finite element simulation of socket fitting on the residual limb: (a) Residual limb model prior to socket application. (b) Residual limb model after socket application, showing deformation due to contact pressure.

Figure 7.

Finite element simulation of socket fitting on the residual limb: (a) Residual limb model prior to socket application. (b) Residual limb model after socket application, showing deformation due to contact pressure.

Figure 8.

Pressure distribution on the residual limb during socket fitting. Color map of contact pressure across the residual limb surface. Red regions indicate high-pressure zones, while blue regions represent low or negligible pressure. The red circles mark the locations of nine sensors used for experimental pressure measurements.

Figure 8.

Pressure distribution on the residual limb during socket fitting. Color map of contact pressure across the residual limb surface. Red regions indicate high-pressure zones, while blue regions represent low or negligible pressure. The red circles mark the locations of nine sensors used for experimental pressure measurements.

Figure 9.

Comparison of measured and simulated pressure values at socket–limb interface.

Figure 9.

Comparison of measured and simulated pressure values at socket–limb interface.

Figure 10.

Correlation between measured and simulated Scatter plot showing the relationship between experimentally measured and FEM-simulated pressure values across eight anatomical locations. A linear regression line is fitted to the data, yielding a correlation coefficient of r = 0.7485 with p < 0.05, indicating a statistically significant and moderately strong positive correlation.

Figure 10.

Correlation between measured and simulated Scatter plot showing the relationship between experimentally measured and FEM-simulated pressure values across eight anatomical locations. A linear regression line is fitted to the data, yielding a correlation coefficient of r = 0.7485 with p < 0.05, indicating a statistically significant and moderately strong positive correlation.

Table 1.

Amputees’ general information.

Table 1.

Amputees’ general information.

| Subject |

Gender |

Age |

Amputated limb |

Height[cm] |

Weight[kg] |

| S1 |

Male |

35 |

Left |

169 |

63 |

| S2 |

Male |

56 |

Right |

162 |

80 |

| S3 |

Male |

47 |

Right |

167 |

61 |

| S4 |

Female |

46 |

Right |

163 |

68 |

Table 3.

The pressure values obtained from eight triaxial force sensors and one sheet-type strain sensor embedded in the prosthetic socket.

Table 3.

The pressure values obtained from eight triaxial force sensors and one sheet-type strain sensor embedded in the prosthetic socket.

| |

AP |

AD |

PP |

PD |

MP |

MD |

LP |

LD |

IS |

Measured Values

[kPa]

|

-0.024 |

0.484 |

0.080 |

0.247 |

0.444 |

-0.158 |

-0.967 |

0.249 |

54.873 |

Table 4.

Confusion matrix for tissue classification and definition of evaluation metrics.

Table 4.

Confusion matrix for tissue classification and definition of evaluation metrics.

| |

Prediction Value |

| Target Tissue |

Non-Target Tissue |

| Correct Value |

Target Tissue |

TP True Positive |

FN False Negative |

| Non-Target Tissue |

FP False Positive |

TP True Negative |

Table 5.

Segmentation accuracy for adipose tissue, femur, and ischium in the residual limb.

Table 5.

Segmentation accuracy for adipose tissue, femur, and ischium in the residual limb.

| Target |

Evaluation Criteria |

| Precision |

Recall |

F-measure |

| Adipose Tissue |

0.913 |

0.938 |

0.925 |

| Femur |

0.914 |

0.955 |

0.934 |

| Ischium |

0.850 |

0.870 |

0.860 |

Table 6.

The pressure values estimated by FEM at nine measurement points.

Table 6.

The pressure values estimated by FEM at nine measurement points.

| |

AP |

AD |

PP |

PD |

MP |

MD |

LP |

LD |

IS |

Simulated Values

[kPa]

|

-0.006 |

0.158 |

0.129 |

0.252 |

0.192 |

-0.145 |

-0.087 |

0.242 |

21.814 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).