1. Introduction

Hyperkalemia is a common electrolyte abnormality in patients with heart failure (HF) and is associated with increased mortality, higher hospitalization rates, and clinical decompensation, particularly when serum potassium levels are markedly elevated (1). International reports show wide variability in the incidence of hyperkalemia among individuals with HF, with substantially higher rates in those with chronic kidney disease (CKD) or multiple comorbidities (1,2).

Several studies have consistently identified major risk factors for hyperkalemia in this population, including CKD, diabetes mellitus, advanced age, hypertension, and the use of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi) or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) (2,3). Beyond its clinical impact, hyperkalemia is a key barrier to optimal HF therapy, as it frequently leads to dose reduction, underuse, or discontinuation of RAASi/MRA, thereby preventing patients from reaching guideline-recommended target doses and contributing to therapeutic inertia (2).

Despite extensive international evidence, local data remain scarce. In Costa Rica, little is known about the frequency of hyperkalemia among patients with HF or its relationship with clinical risk factors. In this context, the present study provides real-world information on the observed proportion of hyperkalemia episodes treated with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS) and describes the clinical characteristics of affected patients, thereby contributing to a better understanding of this complication in a private healthcare setting.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed an observational, descriptive, and retrospective design conducted at the Heart Failure Clinic of Hospital Clínica Bíblica (San José, Costa Rica). The analysis covered a ten-year period from June 2015 to June 2025.

2.1. Case Identification

The identification of cases was performed in two steps. First, the institutional dispensing registry for sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS) was used to identify patients who had potentially experienced hyperkalemia and received SPS treatment. This registry-based approach is not intended to be a sensitive detection method; rather, it captures only episodes managed with SPS and therefore likely underestimates the true frequency of hyperkalemia. Second, the corresponding medical records were reviewed to confirm a formal diagnosis of heart failure, as documented by the treating cardiologist.

This identification strategy captured only hyperkalemia episodes treated with SPS; therefore, the findings describe this specific subgroup and do not reflect all hyperkalemia events occurring in the broader patient population. Episodes managed solely with medication adjustments, diuretics, dietary interventions, or treatment at other healthcare facilities were not included.

2.2. Population and Eligibility Criteria

To describe the frequency of SPS-treated hyperkalemia, the denominator consisted of all unique patients with a confirmed diagnosis of heart failure who were registered in the hospital’s electronic medical record during the same period. This value (n = 11,805) reflects individual patients rather than clinical encounters or repeated visits. Based on this population, the cumulative proportion of patients who developed a hyperkalemia episode requiring SPS was calculated. Because case identification relied exclusively on SPS use, this proportion does not represent the true incidence of hyperkalemia in the heart failure population but rather the frequency of episodes detected through this specific mechanism.

All patients with confirmed heart failure were eligible for inclusion. Those with stage V chronic kidney disease, those receiving dialysis, or those with incomplete medical records were excluded. Hyperkalemia was classified according to institutional criteria: mild (5.0–5.5 mEq/L), moderate (5.6–6.0 mEq/L), and severe (>6.0 mEq/L).

2.3. Data Collection

Data were extracted through direct review of the institutional electronic medical record. The variables collected included demographic characteristics, relevant comorbidities (including CKD stage), heart failure classification based on left ventricular ejection fraction, pharmacologic therapy (RAAS inhibitors, MRA, and other HF medications), and laboratory values—particularly serum potassium and renal function parameters. Clinical management decisions during each episode, such as continuation, dose adjustment, or discontinuation of RAASi/MRA and SPS administration, were also documented. The review and extraction of medical record data were conducted between October and November 2025, after ethical approval had been obtained.

2.4. Medication Exposure Definition

Information on pharmacologic therapy was obtained from the chronic treatment lists documented in the electronic medical record. Because prescription dates and duration of medication use were not consistently available, it was not possible to define a precise temporal exposure window. Therefore, medication exposure was defined as therapy recorded as active in the medical record at the time of the index hyperkalemia episode. This definition reflects real-world documentation practices in retrospective chart reviews and allows descriptive assessment of treatment patterns, but it does not permit inference regarding temporal or causal relationships between medication use and hyperkalemia.

2.5. Data Handling and Analysis

All extracted data were compiled into an electronic spreadsheet and manually verified to ensure accuracy and completeness. Given the descriptive nature of the study, results are presented as absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables and as measures of central tendency and dispersion for continuous variables.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the University of Costa Rica (protocol CEC-UCR-348-2025; approved on September 17, 2025). Given its retrospective design and the exclusive use of information contained in medical records, patient confidentiality was ensured and individual informed consent was not required.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Selection

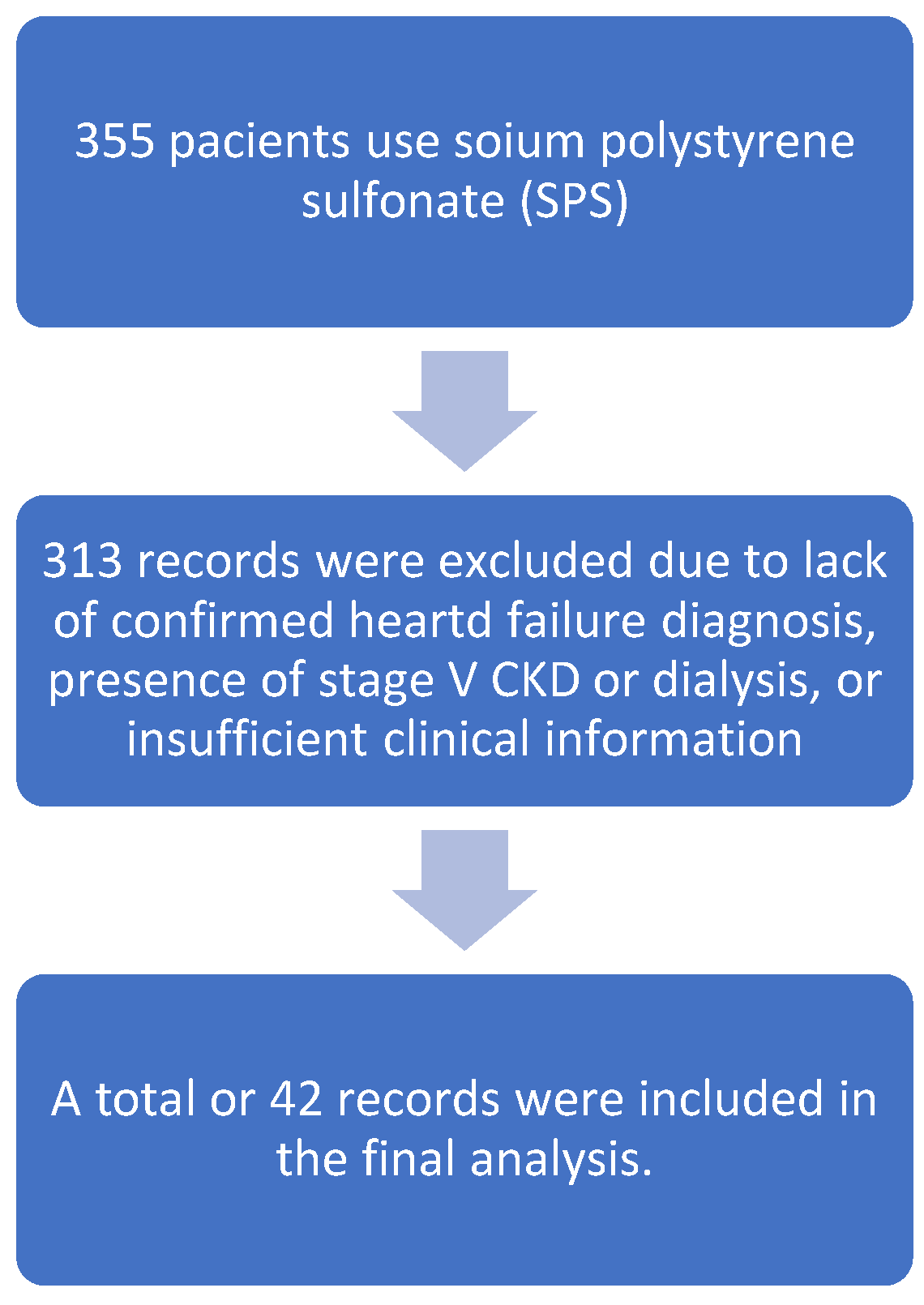

During the period from June 2015 to June 2025, a total of 355 dispensations of sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS) were identified. After reviewing medical records, patients without a confirmed diagnosis of heart failure, those with stage V chronic kidney disease or undergoing dialysis, and cases with insufficient clinical information were excluded. Ultimately, 42 patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis (

Figure 1).

3.2. Observed Proportion of SPS-Treated Hyperkalemia

Among the 11,805 unique patients with a documented diagnosis of heart failure in the hospital database during the study period, the observed proportion of hyperkalemia episodes managed with SPS was 0.37 percent, with annual fluctuations between 0.26 percent and 2.1 percent. This proportion reflects only episodes captured through SPS dispensing and does not represent the true incidence of hyperkalemia in the heart failure population, as it includes only treated cases rather than all hyperkalemia events.

3.3. Demographic Characteristics

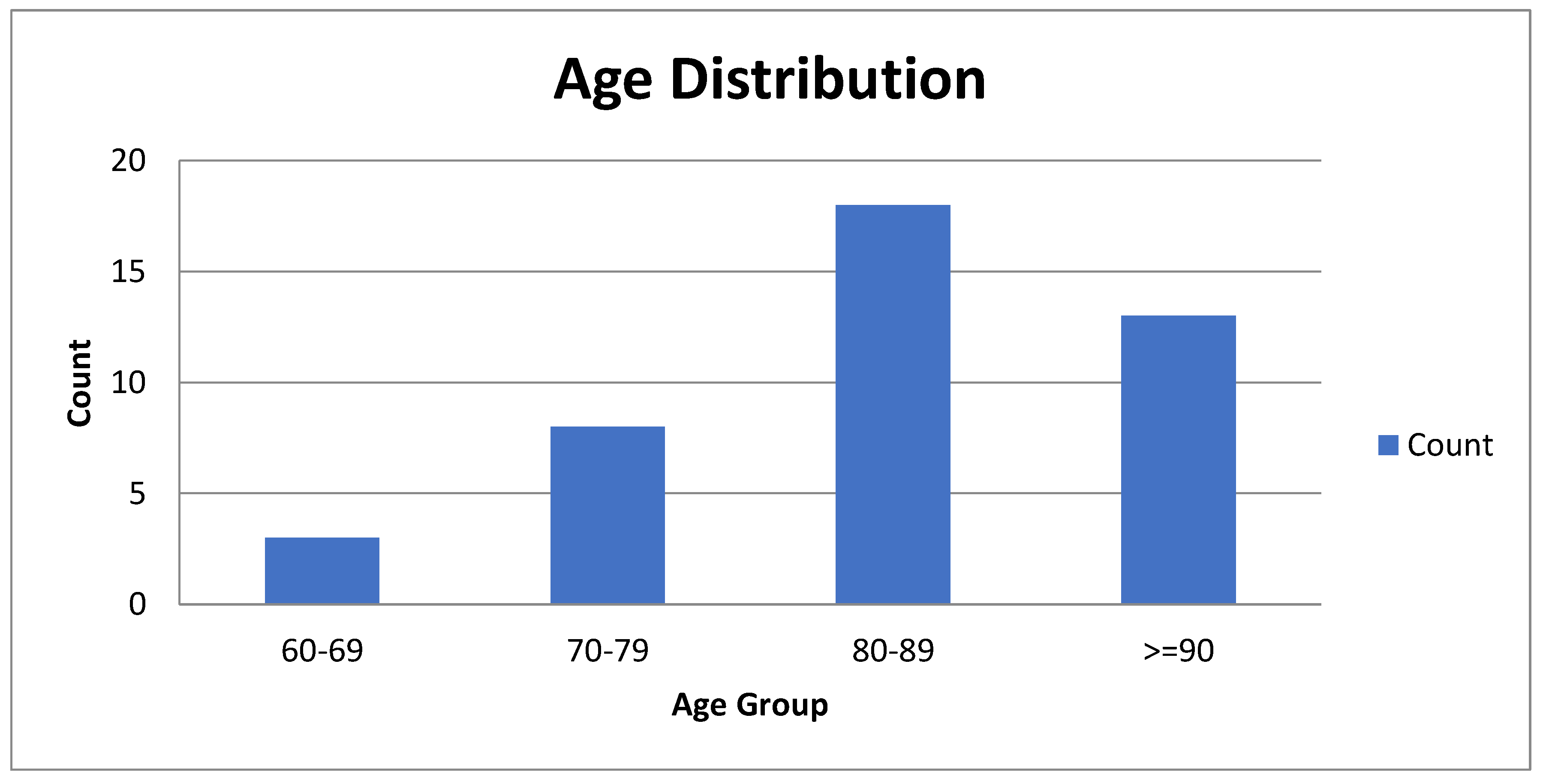

The age distribution was markedly skewed toward advanced age, with no cases documented in individuals younger than 60 years. Three patients (7.1%) were aged 60–69 years, eight (19%) were 70–79 years, 18 (42.9%) were 80–89 years, and 13 (31%) were 90 years or older. Overall, 74% of the cohort consisted of patients aged 80 years or more (

Figure 2). The sex distribution was balanced, with no meaningful differences between men and women.

3.4. Heart Failure Classification

Based on left ventricular ejection fraction, 22 patients (52.4%) had heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), 14 (33.3%) had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), and five (11.9%) had heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF). In one patient (2.4%), the ejection fraction could not be determined due to incomplete information.

3.5. Chronic Kidney Disease Classification

Chronic kidney disease was highly prevalent in the cohort. Of the 42 patients included, 35 had documented CKD, predominantly in advanced stages. Classification was based on the estimated glomerular filtration rate calculated using the CKD-EPI equation incorporating age, serum creatinine, and sex. Approximately half of the cases corresponded to stage 4 CKD, about one-fifth to stage 3b, and roughly 12% to stage 3a. Two cases of acute kidney injury were identified, and in one patient CKD stage could not be determined due to incomplete information.

3.6. Severity and Serum Potassium Levels

Hyperkalemia severity was determined according to the highest serum potassium value recorded during the index episode. Among the 42 patients, four (9.5%) had mild hyperkalemia, 12 (28.6%) moderate hyperkalemia, and 26 (61.9%) severe hyperkalemia. The high proportion of severe cases likely reflects the SPS-based identification method, which tends to capture more clinically significant episodes (

Table 1).

Serum potassium at presentation showed a median of 6.28 mmol/L, a mean of 6.29 mmol/L, and a range from 5.16 to 7.61 mmol/L, consistent with the predominance of moderate to severe episodes.

3.7. Comorbidities

Among the included patients, 35 had CKD (mainly stages 3 and 4), 21 had diabetes mellitus, and a substantial proportion had hypertension, reflecting a high burden of cardiovascular and metabolic multimorbidity.

3.8. Pharmacologic Treatment

At the time of hyperkalemia or during early follow-up, 30 patients (71.4%) were receiving renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi), 21 (50%) mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), and 16 (38.1%) were on both drug classes. The most frequent intervention was the discontinuation of spironolactone, whereas RAASi were generally maintained or dose-adjusted, with complete discontinuation being uncommon (

Table 2).

3.9. Management of Hyperkalemia

All included patients received sodium polystyrene sulfonate, as its dispensing constituted the initial identification criterion. SPS use was documented primarily in moderate and severe episodes, and no adverse events attributable to the medication were documented in the available records; however, underreporting is possible given the retrospective nature of the study and the absence of systematic surveillance for medication-related complications.

3.10. Hospitalizations

Hospitalization was documented in all 42 patients at the time of the index hyperkalemia episode. Admissions were primarily related to heart failure decompensation and/or the management of hyperkalemia, according to clinical records.

3.11. Outcomes

Two deaths occurred during follow-up. In both cases, the documented cause was decompensated heart failure, with no arrhythmias reported prior to death.

3.12. Exploratory Analysis

An exploratory logistic regression analysis was conducted to evaluate potential factors associated with hyperkalemia severity. Given the small sample size and the very low event-per-variable ratio, the model does not meet statistical assumptions and must be interpreted strictly as hypothesis-generating.

Age showed a possible association with both moderate and severe hyperkalemia, and diabetes mellitus demonstrated a signal of association with moderate hyperkalemia. No consistent patterns were observed for sex, chronic kidney disease, MRA use, or RAAS inhibitor use. The wide confidence intervals reflect the limited statistical power of the model (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

4.1. Observed Proportion of Hyperkalemia

In this registry, an observed proportion of SPS-treated hyperkalemia of 0.37 percent was identified among patients with heart failure. Although this value appears lower than rates described in international studies (2–4), such comparisons must be interpreted with caution, as most published cohorts report all hyperkalemia episodes identified through systematic laboratory surveillance. In contrast, our study captured only episodes treated with SPS. The observed proportion therefore reflects a treatment-based subset rather than the true epidemiologic burden of hyperkalemia and likely underestimates its actual frequency.

Several factors may explain the low observed proportion. The identification method, based exclusively on SPS dispensing, misses mild or moderate episodes managed with therapeutic adjustments or dietary or diuretic interventions, as well as cases treated outside the private center. The exclusion of patients with stage V CKD, who are at particularly high risk for hyperkalemia further reduces case capture. Additionally, patients receiving outpatient care in the private sector may seek emergency care in the public system during acute decompensations, contributing to underreporting. For these reasons, the observed proportion should not be interpreted as an epidemiologic rate.

4.2. Patient Profile

Patients in this study were predominantly older adults with a high burden of comorbidities, particularly CKD (35 of 42 cases), consistent with international evidence linking CKD to both hyperkalemia and adverse outcomes in heart failure (5–8). The coexistence of CKD, diabetes mellitus, and advanced age parallels reports showing elevated hyperkalemia prevalence in multimorbid patients (6,9). These characteristics, rather than isolated biochemical derangements, may reflect increased clinical vulnerability, as supported by literature describing hyperkalemia as a marker of frailty and higher hospitalization risk (9–11).

4.3. Age as a Risk Factor

Patients with hyperkalemia were predominantly older adults, aligning with findings by Sriperumbuduri et al., who reported higher hyperkalemia incidence and recurrence in older individuals with multiple comorbidities (12). In our population, 74 percent aged 80 years or older age likely reflects accumulated pathophysiologic burden rather than an independent risk factor (12). Although the exploratory regression suggested a possible association between older age and greater severity, the limited sample size precludes inferential conclusions; these findings should be considered hypothesis-generating only.

4.4. Predominance of Severe Hyperkalemia

Severe hyperkalemia predominated in this cohort (over 60 percent of episodes), a pattern expected given the SPS-based capture method, which preferentially identifies clinically significant events (8,13). The predominance of severe cases is also consistent with the cohort’s multimorbidity profile, including CKD and advanced age, which reduce physiologic reserve and increase susceptibility to marked potassium elevations.

4.5. Absence of Sex Differences

No sex-related differences were observed in the occurrence or severity of hyperkalemia. This finding aligns with literature reporting minimal clinically meaningful differences between men and women once comorbidities are considered (9). However, the small sample size limits the ability to detect subtle differences.

4.6. Mortality

Two deaths occurred during follow-up, both attributed to heart failure decompensation. No arrhythmias were documented before death, although undetected events cannot be excluded. This pattern aligns with evidence indicating that progression of heart failure, rather than hyperkalemia itself, accounts for most mortality in patients with HF (1,13). Given case-capture limitations and sample size, the relationship between hyperkalemia severity and mortality cannot be inferred.

4.7. Use of RAAS Inhibitors and MRAs

RAAS inhibitors and MRAs are foundational therapies in HF management, though their use is associated with an increased risk of hyperkalemia. Evidence indicates that discontinuation of these therapies following hyperkalemia may worsen outcomes (1,9,10,14–17). In our cohort, MRA discontinuation was common, while RAAS inhibitors were generally maintained or dose-adjusted, a pattern consistent with prior reports (6,15,18,19). These findings underscore the need for strategies that support continuation of neurohormonal therapy, particularly MRAs, in patients with high hyperkalemia risk, though the retrospective nature of the study limits inference regarding causality.

4.8. Relevance of New Therapies and Modern Management of Hyperkalemia

New potassium binders and non-steroidal MRAs have demonstrated benefits in facilitating continuation of RAAS-modifying therapies in high-risk patients (15,19–21). Likewise, SGLT2 inhibitors and ARNIs have been associated with lower hyperkalemia risk and improved treatment optimization (5,20). In Costa Rica, where CKD and diabetes prevalence is high and SPS has historically been the primary potassium-lowering option (18,22,23), these therapies could help reduce MRA discontinuation. However, limited access remains a barrier (21). These considerations contextualize the observed treatment patterns but extend beyond the dataset’s scope.

4.9. Clinical Implications for Costa Rica

The clinical profile observed in this cohort mirrors national reports documenting frequent multimorbidity among patients with HF, including diabetes, hypertension, and CKD (22). A recent Costa Rican study similarly found that HF patients with diabetes exhibit greater frailty and heightened susceptibility to electrolyte disturbances (23). Within this context, the high prevalence of CKD and the observed patterns of therapy discontinuation highlight ongoing challenges in optimizing HF management in the country.

4.10. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Its retrospective design relied on the completeness of medical records, and case capture was restricted to SPS-treated episodes, potentially omitting many hyperkalemia events. Patients treated at other facilities would not be captured, and exclusion of individuals with stage V CKD further reduces representativeness (24). The small sample size limited statistical power; therefore, the regression analysis is exploratory only. The absence of time-at-risk data precludes incidence calculation. Additionally, incomplete documentation regarding medication changes and follow-up constrained evaluation of management decisions. Comparisons with international cohorts must be interpreted cautiously, as methodological differences, particularly case-capture strategies limit direct comparability.

4.11. Strengths

Strengths of this study include its real-world context, decade-long time frame, clinically grounded inclusion criteria, detailed documentation of management strategies, and the novelty of being the first systematic description of SPS-treated hyperkalemia in HF patients in Costa Rica.

5. Conclusions

In this registry from a private center in Costa Rica, the observed proportion of hyperkalemia episodes treated with sodium polystyrene sulfonate among patients with heart failure was low compared with values reported internationally. However, this difference likely reflects methodological variability rather than true epidemiologic differences. Studies reporting higher frequencies typically identify all hyperkalemia episodes through systematic laboratory surveillance, whereas our SPS-based approach captures only clinically significant events managed with this medication. Accordingly, these findings represent treatment-captured cases and should not be interpreted as estimates of hyperkalemia incidence in the broader heart failure population.

The episodes identified occurred predominantly in older adults with multimorbidity and a high prevalence of chronic kidney disease, underscoring the clinical vulnerability of this subgroup. The predominance of severe hyperkalemia and the need for hospitalization further emphasize the relevance of the detected events. Two deaths occurred during follow-up, both related to heart failure decompensation, consistent with literature describing heart failure progression as the leading cause of mortality in this population.

Regarding management, discontinuation of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists was common, whereas renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors were generally maintained or dose-adjusted. This pattern highlights the ongoing challenge of balancing hyperkalemia risk with the need to preserve evidence-based neurohormonal therapies.

Overall, these findings underscore the need for strategies that support the continuation of guideline-directed medical therapy, including close monitoring, individualized dose adjustments, and, when available, therapeutic options that enable safe maintenance of MRAs. The results also highlight the importance of future multicenter studies that incorporate both public and private healthcare settings and include patients with advanced CKD to better characterize the true burden of hyperkalemia in individuals with heart failure in Costa Rica.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, José Miguel Chaverri-Fernández and Esteban Zavaleta-Monestel; methodology, José Miguel Chaverri-Fernández; validation, Sebastián Arguedas-Chacón, Jeaustin Mora-Jiménez, and Kevin José Mora-Cruz; formal analysis, Sebastián Arguedas-Chacón; investigation, Esteban Zavaleta-Monestel and Sofía Suárez-Sánchez; resources, José Miguel Chaverri-Fernández; data curation, Sofía Suárez-Sánchez, Jeaustin Mora-Jiménez, and Kevin José Mora-Cruz; writing—original draft preparation, Kevin José Mora-Cruz and José Miguel Chaverri-Fernández; writing—review and editing, José Miguel Chaverri-Fernández, Esteban Zavaleta-Monestel, and Sofía Suárez-Sánchez; visualization, Jeaustin Mora-Jiménez; supervision, José Miguel Chaverri-Fernández; project administration, José Miguel Chaverri-Fernández, Esteban Zavaleta-Monestel; funding acquisition.

Funding

This research was funded by AstraZeneca, grant number not applicable. The article processing charge (APC) was funded by AstraZeneca.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the University of Costa Rica (Comité Ético Científico de la Universidad de Costa Rica) under protocol number CEC-UCR-348-2025, approved on 17 September 2025. The analysis relied exclusively on pre-existing medical records, and no data were accessed prior to ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed Consent Statement: Patient consent was waived because the study involved the retrospective analysis of pre-existing medical records, with no direct patient contact and no identifiable information included in the dataset.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study consist of confidential medical records and cannot be shared publicly due to ethical and privacy restrictions. All data used in the analysis are presented within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. AstraZeneca provided financial support for this study; however, the funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HF |

Heart failure |

| CKD |

Chronic kidney disease |

| SPS |

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate |

| RAASi |

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors |

| MRA |

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists |

| HFpEF |

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HFmrEF |

heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction |

| CKD-EPI |

Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation |

| SGLT2 |

sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 |

| ARNI |

angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

References

- Lima IGCV, Nunes JT, de Oliveira IH, Ferreira SMA, Munhoz RT, Chizzola PR, et al. Association of potassium disorders with the mode of death and etiology in patients with chronic heart failure: the INCOR-HF study. Sci Rep. 2024 Dec 4;14(1):30167. [CrossRef]

- Rakisheva A, Marketou M, Klimenko A, Troyanova-Shchutskaia T, Vardas P. Hyperkalemia in heart failure: Foe or friend? Clin Cardiol. 2020 Jul;43(7):666–75. [CrossRef]

- AlSahow A, AbdulShafy M, Al-Ghamdi S, AlJoburi H, AlMogbel O, Al-Rowaie F, et al. Prevalence and management of hyperkalemia in chronic kidney disease and heart failure patients in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). J Clin Hypertens. 2023 Mar;25(3):251–8. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-López A, Franco-Gutiérrez R, Pérez-Pérez AJ, Regueiro-Abel M, Elices-Teja J, Abou-Jokh-Casas C, et al. Impact of hyperkalemia in heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: A retrospective study. J Clin Med. 2023 May 22;12(10):3595. [CrossRef]

- Clinical Management of Hyperkalemia—ClinicalKey [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.clinicalkey.es/#!/content/playContent/1-s2.0-S0025619620306182.

- Ismail U, Sidhu K, Zieroth S. Hyperkalaemia in heart failure. Card Fail Rev. 2021 May 12;7:e10. [CrossRef]

- Recomendaciones para el manejo de la hiperpotasemia en urgencias. Emergencias [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 24]. Available from: https://revistaemergencias.org/.

- Banerjee D, Rosano G, Herzog CA. Management of heart failure patient with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021 Jul;16(7):1131–9. [CrossRef]

- Beavers CJ, Greene SJ. Hyperkalemia in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: Implications and management. Heart Fail Rev. 2025;30(6):1291–305. [CrossRef]

- Cañas AE, Troutt HR, Jiang L, Tonthat S, Darwish O, Ferrey A, et al. A randomized study to compare oral potassium binders in the treatment of acute hyperkalemia. BMC Nephrol. 2023 Apr 5;24:89. [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulos A, Papamichail A, Briasoulis A, Loritis K, Bourazana A, Magouliotis DE, et al. Heart failure in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Clin Med. 2023 Sep 21;12(18):6105. [CrossRef]

- Dai D, Sharma A, Alvarez PJ, Woods SD. Multiple comorbid conditions and healthcare resource utilization among adult patients with hyperkalemia: a retrospective observational cohort study using association rule mining. J Multimorb Comorbidity. 2022 Nov;12:26335565221098832. [CrossRef]

- Sriperumbuduri S, McArthur E, Hundemer GL, Canney M, Tangri N, Leon SJ, et al. Initial and recurrent hyperkalemia events in patients with CKD in older adults: A population-based cohort study. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2021 Jan;8:20543581211017408. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto N, Sakaguchi Y, Hattori K, Kawano Y, Kawaoka T, Doi Y, et al. Discontinuing renin–angiotensin system inhibitors after incident hyperkalemia and clinical outcomes: Target trial emulation. Hypertens Res. 2025 Jul;48(7):2034–44. [CrossRef]

- Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in heart failure: An individual patient-level meta-analysis—ClinicalKey [Internet]. [cited 2025 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.clinicalkey.es/#!/content/playContent/1-s2.0-S0140673624017331.

- Sethi R, Vishwakarma P, Pradhan A. Evidence for aldosterone antagonism in heart failure. Card Fail Rev. 2024 Nov 12;10:e15. [CrossRef]

- Mann DL, Givertz MM, Vader JM, Starling RC, Shah P, McNulty SE, et al. Effect of treatment with sacubitril/valsartan in patients with advanced heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2022 Jan 1;7(1):17–25.

- Scicchitano P, Iacoviello M, Massari F, De Palo M, Caldarola P, Mannarini A, et al. Optimizing therapies in heart failure: The role of potassium binders. Biomedicines. 2022 Jul 16;10(7):1721. [CrossRef]

- Oshima A, Imamura T, Narang N, Kinugawa K. Management of hyperkalemia in chronic heart failure using sodium zirconium cyclosilicate. Clin Cardiol. 2021 Sep;44(9):1272–5. [CrossRef]

- Butler J, Usman MS, Khan MS, Greene SJ, Friede T, Vaduganathan M, et al. Efficacy and safety of SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure: Systematic review and meta-analysis. ESC Heart Fail. 2020 Dec 22;7(6):3298–309. [CrossRef]

- Kanda E, Rastogi A, Murohara T, Lesén E, Agiro A, Arnold M, et al. Clinical impact of suboptimal RAAS inhibitor therapy following an episode of hyperkalemia. BMC Nephrol. 2023 Jan 19;24:18.

- Speranza Sánchez MO, Quesada Chaves D, Castillo Chaves G, Laínez Sánchez L, Mora Tumminelli L, Brenes Umaña CD, et al. Registro nacional de insuficiencia cardíaca de Costa Rica: El estudio RENAIC CR. Rev Costarric Cardiol. 2017;19(1–2):21–34.

- Chaves DQ, Sánchez MS, Chaves GC, Sánchez LL, Tumminelli LM, Umaña CB, et al. Diabetes mellitus en pacientes con insuficiencia cardíaca en Costa Rica: Un estudio retrospectivo. Rev Costarric Cardiol. 2024;26(2):33–40.

- Chang HH, Chiang JH, Tsai CC, Chiu PF. Predicting hyperkalemia in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease using the XGBoost model. BMC Nephrol. 2023 Jun 12;24:169. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).