1. Introduction

While highly effective front-line therapies have become available for multiple myeloma (MM), nearly all patients eventually relapse and become refractory to treatment, and the five-year overall survival (OS) rate remains around 50% [

1,

2,

3]. Outcomes are particularly poor for patients with relapsed or refractory MM (RRMM), as the durability of responses decreases with each successive line of therapy. Therefore, identifying therapeutic options that can prolong OS in RRMM patients is still needed. Treatment regimens incorporating monoclonal antibodies have demonstrated durable responses and extended progression-free survival. However, final OS analyses for these therapies have thus far only been reported for a few randomised controlled trials (RCTs) [

1,

2,

3]. Although lenalidomide and dexamethasone combination therapy is considered the standard of care (SOC), the addition of a third agent, such as daratumumab or elotuzumab, has been investigated in recent years.

Daratumumab is a human monoclonal antibody that targets CD38, a cell surface receptor which is highly expressed on multiple myeloma (MM) cells. It exerts its effects via direct anti-tumour and immunomodulatory mechanisms. Elotuzumab is a first-in-class humanised immunoglobulin G1 immunostimulatory monoclonal antibody with multiple mechanisms of action against MM cells, including direct natural killer (NK) cell activation, NK cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, and macrophage-mediated antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis [

1].

In order to summarise the current state of research on these two agents, we employed an artificial intelligence (AI) tool: the IPDFROMKM method [

4,

5]. This method is designed to reconstruct individual patient data (IPD) from published Kaplan–Meier curves. This tool extracts information from time-to-event curves to create a database of “reconstructed” patients that includes follow-up time and event status at patient level. This “reconstructed” IPD dataset enables researchers to simulate comparative analyses between treatments, even when “real” comparative trials are unavailable.

In the present report, we conducted an indirect comparison of daratumumab plus standard of care (SOC) versus elotuzumab plus SOC using reconstructed IPD.

2. Materials and Methods

Study design: First, we identified RCTs evaluating daratumumab or elotuzumab in combination with standard of care (SOC) versus SOC alone. Then, we applied the IPDfromKM method to reconstruct the trial populations. Finally, we compared the two triple treatment regimens based on the aggregated, reconstructed datasets.

Literature search and inclusion criteria: To identify relevant RCTs, we searched PubMed, Scopus and Embase according to standard literature search procedures. Our inclusion criteria were: (i) randomised trial in patients with RRMM; (ii) a time-to-event endpoint, where the event was death from any cause; (iii) availability of a Kaplan–Meier graph comparing the treatment group with the standard of care.

Data analysis and statistical comparisons. We used the IPDfromKM method [

4,

5] to reconstruct IPD from Kaplan-Meier curves. Firstly, we digitised each Kaplan-Meier graph using WebPlotDigitizer (version 4,

https://apps.automeris.io/). Then, the AI algorithm reconstructed the IPD for each curve evaluated in the analysis using the x-y coordinates of the digitised curves [

4]. Once these databases of reconstructed patients had been created, we made indirect comparisons between each triple regimen and the standard of care, and between daratumomab and elotuzumab, using the same statistical tests (e.g. the Cox multiple regression model) as in studies based on “real” patients.

In terms of the design of our analysis, as RCTs were selected as the source of the clinical material, we first evaluated the degree of between-trial heterogeneity by undertaking an analysis that included each of the two control arms. Next, we conducted an indirect comparison between the daratumomab arm, the elotuzumab arm, and the two SOC arms pooled together. In these indirect comparisons, we determined hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) firstly between each triple treatment versus the two SOC arms pooled together, and then between daratumomab plus SOC versus and elotuzumab plus SOC.

3. Results

Our PubMed search identified two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that met our inclusion criteria: POLLUX [

3] and ELOQUENT-2 [

4]. The main characteristics of these two trials are summarised in

Table 1. In the real patient datasets from these two RCTs, the magnitude of the overall survival (OS) benefit was greater for daratumumab (HR=0.73) than for elotuzumab (HR=0.82); likewise, the statistical significance of this benefit was higher for daratumumab (p=0.0044) than for elotuzumab (p=0.041).

Our OS analysis based on reconstructed patients showed that the HRs estimated from reconstructed patients were very close to those reported in real trials (daratumumab according to the POLLUX trial: HR from reconstructed patients = 0.7873, 95% CI, 0.6193 to 1.001 versus HR from real patients = 0.73, 95% CI, 0.58 to 0.91; elotuzumab according to the ELOQUENT-2 trial: HR from reconstructed patients = 0.8447, 95% CI 0.6926 to 1.03 versus HR from real patients = 0.820, 95% CI 0.676 to 0.995). Furthermore, when the two SOC arms were indirectly compared based on reconstructed patients, the ELOQUENT-2 trial controls were found to fare worse than the POLLUX trial controls.

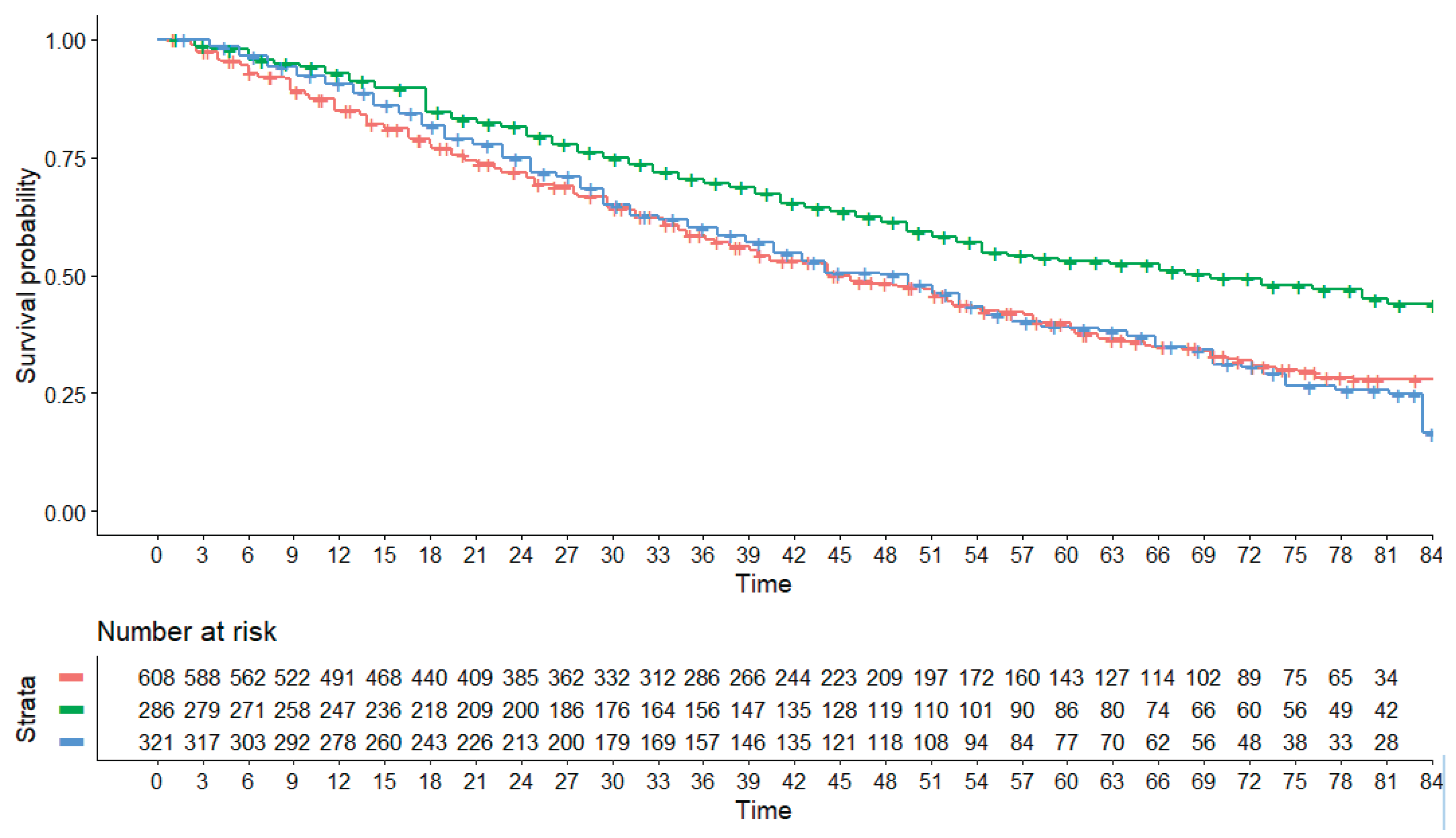

The results of the indirect comparisons generated by our main analysis are shown in

Figure 1. The following HRs were estimated in the comparison between each of the two triple treatments versus SOC: daratumumab vs SOC, HR = 0.6373 (95% CI, 0.5186 to 0.7831); elotuzumab vs SOC, HR = 1.0826 (95% CI, 0.9112 to 1.2862). In the reconstructed datasets, the OS curve for elotuzumab, which was at the limits of statistical significance in real patients in the Eloquent-2 trial, was found to be not statistically different to the OS for SOC. More interestingly, this curve was almost identical to the OS curve for the two pooled control groups. This can be explained by the fact that the OS for the two pooled control groups was better than that for the controls in the ELOQUENT-2 trial and is consistent with the finding that the controls in the POLLUX trial fared significantly better than the controls in the ELOQUENT-2 trial (HR = 0.72411; 95% CI: 0.5851 to 0.896).

Finally, our main analysis showed a significant difference favouring daratumumab in the indirect comparison of daratumumab plus SOC vs elotuzumab plus SOC (HR = 0.589, 95% CI: 0.450 to 0.770). This is the most relevant result of our investigation.

4. Discussion

This investigation is a typical example of how the IPDfromKM method [

4,

5] can be used to reconstruct individual patient data and generate original findings in terms of indirect comparisons in situations where randomised controlled trials (RCTs) based on “real”' patients are lacking. As well as generating original findings, these indirect comparisons help to improve the interpretation of results from “real” patients and explain some controversial results. The pros and cons of this approach have been widely debated in previous studies based on this method. In brief, good-quality comparisons can be made between treatments that have not been directly compared in real trials. However, some intrinsic limitations of this approach are unavoidable, particularly because subgroup analyses cannot be performed unless separate Kaplan-Meier curves have been reported for each subgroup in the published articles, which unfortunately occurs quite rarely.

In conclusion, our investigation provided important evidence favouring daratumumab over elotuzumab as a third agent in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with RRMM.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Sorgiovanni I, Del Giudice ML, Galimberti S, Buda G. Monoclonal Antibodies in Relapsed-Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2025 Jan 22;18(2):145. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos MA, San-Miguel J, Belch A, White D, Benboubker L, Cook G, Leiba M, Morton J, Ho PJ, Kim K, Takezako N, Moreau P, Kaufman JL, Sutherland HJ, Lalancette M, Magen H, Iida S, Kim JS, Prince HM, Cochrane T, Oriol A, Bahlis NJ, Chari A, O'Rourke L, Wu K, Schecter JM, Casneuf T, Chiu C, Soong D, Sasser AK, Khokhar NZ, Avet-Loiseau H, Usmani SZ. Daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: updated analysis of POLLUX. Haematologica. 2018 Dec;103(12):2088-2096. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos MA, Lonial S, White D, Moreau P, Weisel K, San-Miguel J, Shpilberg O, Grosicki S, Špička I, Walter-Croneck A, Magen H, Mateos MV, Belch A, Reece D, Beksac M, Spencer A, Oakervee H, Orlowski RZ, Taniwaki M, Röllig C, Einsele H, Matsumoto M, Wu KL, Anderson KC, Jou YM, Ganetsky A, Singhal AK, Richardson PG. Elotuzumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone in RRMM: final overall survival results from the phase 3 randomized ELOQUENT-2 study. Blood Cancer J. 2020 Sep 4;10(9):91. [CrossRef]

- Liu N, Zhou Y, Lee JJ. IPDfromKM: reconstruct individual patient data from published Kaplan-Meier survival curves. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21:111. [CrossRef]

- Messori A. Reconstruction of individual-patient data from the analysis of Kaplan-Meier curves: this method is widely used in oncology and cardiology –List of 57 studies in oncology and 66 in cardiology (preprint), Open Science Framework. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).