Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- ➢

- Natural fiber for composite materials, technical textiles, or biodegradable packaging.

- ➢

- Residual biomass for biogas or biochar production.

- ➢

- Substrates for microbial cultures in biotechnology.

- – agro-industrial start-ups oriented toward the bioeconomy,

- – applied research projects in chemical, environmental, and biotechnological fields,

- – the cosmetic-pharmaceutical supply chain, increasingly committed to sustainability and traceability.

2. The Glycyrrhiza Plant: Botanical and Chemical-Physical Characteristics

- China: The leading producer of licorice, accounting for about 80% of global production. Chinese licorice is used both for medicinal purposes and confectionery.

- Iran: The second-largest producer, with extensive licorice cultivation across several provinces. Iran exports licorice to many countries.

- Turkey: Also, an important producer and exporter of licorice root.

- Syria and Afghanistan: These countries also contribute significantly to global licorice production.

- a)

- Color: Dried licorice root is dark brown externally and golden yellow internally. Concentrated licorice extract tends to have a dark hue due to glycyrrhizin and other compounds [28].

- b)

- Solubility: Glycyrrhizin and other compounds are water-soluble, which is why traditional licorice extraction is performed by infusing or boiling roots in water. Aqueous extracts are viscous and have a syrup-like consistency [29].

- c)

- Taste: Licorice has a distinctive flavor, sweet and slightly bitter, mainly due to glycyrrhizin, which is about 50 times sweeter than sugar [29].

- d)

- Density: Dried licorice root has relatively low density and is easily crumbled, facilitating grinding into powder [28].

- e)

- Thermal behavior: Licorice root has moderate heat resistance, but the extraction of glycyrrhizin and other bioactive compounds can be affected by high temperatures. For this reason, extraction processes are carried out under controlled temperatures to avoid thermal degradation of active principles [30].

- f)

- Viscosity: Concentrated licorice extracts, particularly those containing glycyrrhizin, may have a viscous consistency, making them suitable for use in candies, syrups, and other confectionery products [31].

- g)

- Stability: Licorice extracts tend to be stable over time, but their stability can be compromised by factors such as humidity and high temperature. The combined use of ultrasound and cold plasma has significantly improved the yield and concentration of bioactive compounds compared to traditional methods. The study also highlights the effect of temperature and extraction time on the stability of glycyrrhizin [32].

3. Preliminary Stages in the Licorice Supply Chain: Cultivation and Harvesting, Cleaning, and Drying

3.1. Stage 1: Cultivation and Harvesting

3.2. Stage 2: Root Cleaning

3.3. Stage 3: Root Drying

4. Industrial Processing of Licorice Root

- I.

- Licorice juice extraction, which allows the desired compounds (such as glycyrrhizin and other flavonoids) to be obtained from the root, producing a juice suitable for various applications in the food, medical, and pharmaceutical sectors, as will be examined in detail in the following sections.

- I.

- II. Physical residue (waste), consisting of fibers denatured by the boiling process and non-usable parts. This highlights the need to find solutions for reusing these residues within a circular sustainability framework, which is the focus of this study.

4.1. Licorice Juice Extract

- – Water extraction: This is the most common method, where dried or fresh roots are immersed in hot or boiling water for a period of time. Heat facilitates the solubilization of active compounds, dissolving soluble components such as glycyrrhizin [39]. Hot extraction increases solubility and extraction speed, allowing a more concentrated final product to be obtained in a shorter time compared to other extraction methods.

- – Solvent extraction: Ethanol, a polar solvent, can extract a wider range of compounds, including those not water-soluble. Ethanol use enables a more complete extract, containing both water-soluble and less polar compounds [40]. Another approach is the use of water-alcohol mixtures, which optimize extraction by balancing compound solubility. Mixtures can be adjusted depending on the compounds targeted. Water and ethanol are generally considered safe and accessible for use in food and herbal extracts, and are fundamental solvents for extraction processes due to their low cost and safety [41].

- a)

- Simple filtration, used to separate insoluble solids from a solution. For example, after solvent extraction, it can remove solid particles [40].

- b)

- Vacuum filtration, employed for faster and more efficient separations. A pump creates a vacuum that accelerates liquid passage through the filter [43].

- c)

- Membrane filtration, which uses porous membranes to separate compounds based on size. It can be useful for concentrating or purifying liquid extracts [44].

- d)

- Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC), used for monitoring extractions and preliminary compound separation. Licorice residues may include root fragments, powders, resins, or other plant materials not fully extracted during preparation. These physical residues may still contain bioactive compounds such as flavonoids, saponins, alkaloids (e.g., glycyrrhizin), and other phenolic substances, which could be of interest for recovering additional products or for quality evaluation [45].

- e)

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), one of the most advanced techniques for compound separation and purification. It uses high pressure to force solvent through a column packed with adsorbent material. It is highly effective for analyzing active components of licorice root [46].

- f)

- Ion-Exchange Chromatography, used to separate ionic compounds. It can be useful for isolating flavonoids. Beyond chromatography, this study also explores how carbonized licorice residues (char) can be used for adsorption purposes, a theme that may integrate with ion-exchange chromatography applications [47].

| Historical Period | Main Technique | Short Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical Period | Main Technique | Short Description | Advantages | Limitations |

| 1950 [40] | Simple Filtration | Separation of insoluble solids using filter paper or sieves | Easy, inexpensive | Low selectivity, does not remove fine particles |

| 1960 [43] | Vacuum Filtration | Use of a vacuum pump to accelerate filtration | Faster and more efficient | Still limited in purity |

| 1970 [44] | Membrane Filtration | Porous membranes separate molecules by size (microfiltration, ultrafiltration) | Juice concentration and purification | Higher cost, risk of membrane fouling |

| 1980 [45] | Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) | Qualitative analysis of compounds (flavonoids, glycyrrhizin) | Quick, inexpensive, useful for screening | Not quantitative, low resolution |

| 1990 [46] | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Quantitative analysis and precise separation of active compounds | High sensitivity and accuracy | Requires costly instrumentation |

| 2000 [47] | Ion Exchange Chromatography | Separation of ionic compounds such as glycyrrhizin and salts | High selectivity | Operational complexity |

| 2020 [45,46,47] | Combined Techniques (HPLC-MS, advanced membranes, preparative chromatography) | Integrated approaches for standardized and pure extracts | Maximum efficiency, industrial standardization | High costs, need for technical expertise |

- – Food industry: It is used as a natural sweetener in candies and other food products thanks to its distinctive flavor and sweetness, which is about 50 times greater than that of regular sugar. It is also often used in dietary supplements for its potential health benefits, including modulation of the immune system. In addition, it is employed in some alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages to provide a unique flavor, such as in certain beers, liqueurs, and teas [21].

- – Herbal medicine and traditional medicine: Licorice is known for its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and digestive properties. It is used in infusions and teas to relieve gastrointestinal disorders, coughs, and sore throats. It is also employed in herbal and phytotherapeutic preparations for its anti-inflammatory, expectorant, and digestive effects [49].

- – Cosmetic industry: Licorice extract (Glycyrrhiza glabra) is widely used in cosmetics for its soothing, anti-inflammatory, and especially skin-lightening properties, due to compounds such as glabridin and liquiritin, which modulate melanin production and reduce skin hyperpigmentation [50].

- – Pharmaceutical industry: Licorice extract is an ingredient in certain medicines for the treatment of respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders [49]. Glycyrrhizin, an active compound of licorice, also has antiviral effects. It is important to note that licorice consumption should be moderate, as excessive intake may lead to side effects such as hypertension [51].

| Historical Period | Sector | Main Applications | Notes / Added Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient Times – Middle Ages 19th–Early 20th Century Mid-20th Century (1950s–1970s) |

Herbal medicine e Traditional medicine |

Infusions, decoctions for cough, sore throat, digestive disorders | Widely used in Ayurveda, Traditional Chinese Medicine, and Greco-Roman herbalism |

| Food industry | Natural sweetener in candies, syrups, teas, and beverages | Glycyrrhizin recognized as ~50x sweeter than sucrose | |

| Pharmaceutical industry | Syrups for cough, gastroprotective preparations, anti-inflammatory remedies | Standardization of extracts begins | |

| Late 20th Century (1980s–1990s) 2000s |

Cosmetic industry | Skin-soothing creams, anti-inflammatory gels, whitening agents for hyperpigmentation | Glabridin and liquiritin studied for skin-lightening |

| Nutraceuticals and Functional foods | Dietary supplements, immune-modulating formulations, antioxidant beverages | Growing demand for natural health products | |

| 2010s 2020s Historical Period Ancient Times – Middle Ages |

Broader food and beverage industry | Flavoring in beers, liquors, herbal teas, functional drinks | Expansion into craft beverages and niche markets |

| Integrated applications | Combined use in food, pharma, cosmetics, nutraceuticals, veterinary medicine, and biotechnology | Research on antiviral properties, nanocarriers for cosmetics, and sustainable valorization of by-products | |

| Sector | Main Applications | Notes / Added Value | |

| Herbal medicine e Traditional medicine | Infusions, decoctions for cough, sore throat, digestive disorders | Widely used in Ayurveda, Traditional Chinese Medicine, and Greco-Roman herbalism | |

| 19th–Early 20th Century Mid-20th Century (1950s–1970s) |

Food industry | Natural sweetener in candies, syrups, teas, and beverages | Glycyrrhizin recognized as ~50x sweeter than sucrose |

| Pharmaceutical industry | Syrups for cough, gastroprotective preparations, anti-inflammatory remedies | Standardization of extracts begins |

4.2. Industrial Residue Waste

- a)

- b)

- c)

- d)

- e)

- f)

- g)

- h)

- Environmental impact and sustainable construction: Licorice root processing residues, rich in cellulose and lignin, can be transformed into bioplastics, compostable materials, and biocomposites for green building. Recent studies, including that of L. Madeo [75], have demonstrated the validity of this approach within the framework of the circular bioeconomy.

- i)

- Smoke filtration: Standardized extracts of Glycyrrhiza glabra root [76,77] (in powder, block, or liquid form) are used in cigarette filters and additives for their flavoring, humectant, and partly antioxidant properties. However, there is no consolidated evidence that the tobacco industry employs industrial licorice residues as toxic attenuators; this remains under study.

- j)

| Sector of Use | Development Period | Indicative Years | Market Phase | Future Prospects (2025–2035) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fertilizer / Compost [54,55,56] | Historical → Current | <2000 – present | Already widespread in organic farming | Certified compost, integration with biochar, green agricultural market |

| Biomass for energy [57,58,59,60] | Initial development → Current | 2005 – present | Pilot plants and research | Second-generation bioethanol, advanced gasification |

| Food industry [61,62,63,64] | Historical → Current | <1980 – present | Widely used as flavoring | New “clean label” products, standardized natural additives |

| Cosmetics [65,66,67] | Current | 2010 – present | Growth in the natural cosmetics market | Eco-friendly product lines for hair and scalp |

| Phytotherapy (ointments, creams) [68,69] | Historical → Current | <2000 – present | Consolidated use in herbal medicine | Certified dermatological creams, innovative topical products |

| Biomaterials / Bioplastics [70,71] | Initial development → Current | 2015 – present | Prototypes and industrial research | Compostable packaging, green start-ups, sustainable construction |

| Bioremediation and water purification [72,73,74] | Current | 2018 – present | Advanced studies and pilot applications | Industrial bio-adsorbents for water treatment plants and industries |

| Sustainable green building [75] | Current (Madeo 2025) | 2020 – present | First applications in green construction | Certified insulating panels, EU incentives, sustainable building market |

| Smoke filtration (treated residues) [76,77] | Historical → Current | <1970 – present | Use of standardized extracts | Research on alternative natural filters |

| Textile industry (fiber, dye, antimicrobial) [78,79,80,81] | Current | 2020 – present | Research and initial applications | Antimicrobial fabrics for sports/medical use, sustainable fashion |

5. Fiber: Characteristics and Potential Applications

- – Green building and construction materials – use of the fiber as reinforcement in insulating panels, lightweight plasters, and eco-compatible composites.

- – Eco-friendly paper and cardboard – employment of fibers as an alternative raw material for paper production, reducing dependence on wood-derived cellulose.

- – Agriculture and organic substrates – direct or composted use as a soil amendment, improving soil structure, water retention, and resilience under saline conditions.

- – Sustainable textiles – valorization of the fiber as a source of natural pigments and as reinforcement in technical fabrics with antimicrobial and fire-resistant properties.

- – Biodegradable packaging – integration of the fiber into biopolymers for the production of lightweight, compostable, and environmentally friendly packaging.

5.1. Green Building and Construction Materials

5.2. Eco-Friendly Paper and Cardboard

5.3. Agriculture and Organic Substrates

5.4. Sustainable Textiles

5.5. Biodegradable Packaging

5.6. Comparison among the Main Application Sectors of Licorice Fiber

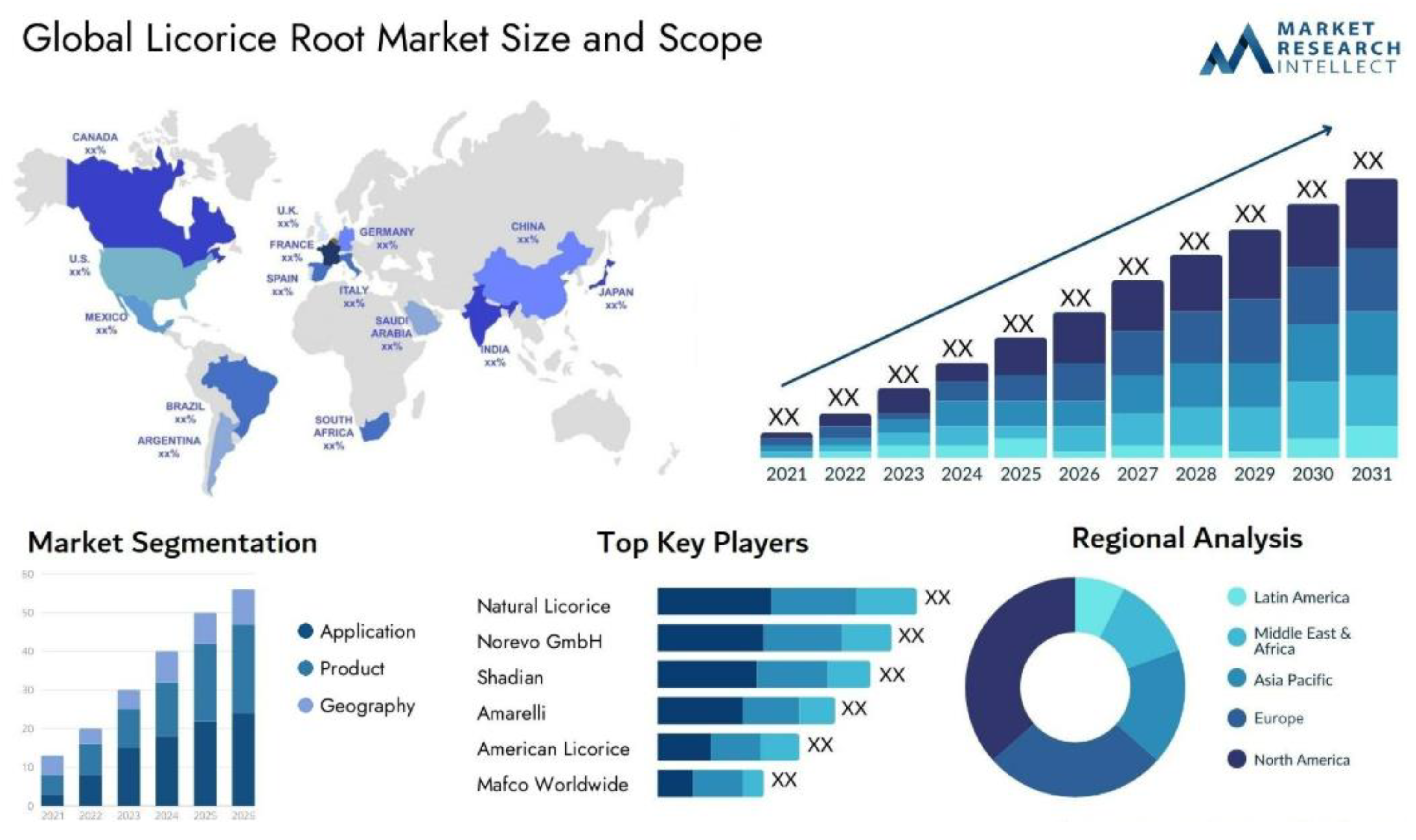

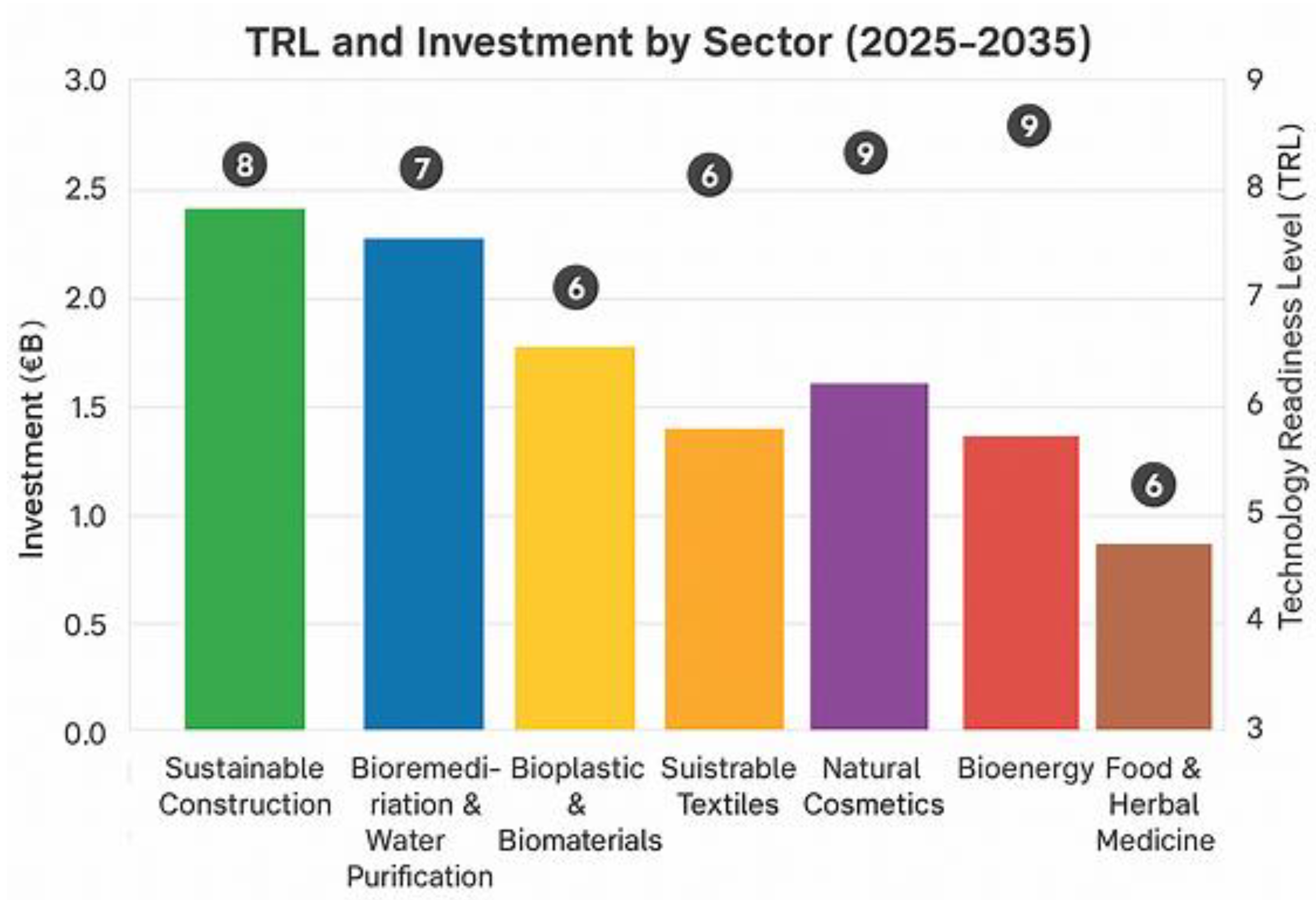

6. Market Outlook and Future Investments

- i.

- Industrial scalability, with pilot plants and modular lines for biomaterials and green building.

- i.

- ii. Supply chain integration, through supply agreements, traceability, and quality standards.

- i.

- iii. Green finance, leveraging European programs (Horizon Europe, LIFE, Innovation Fund) and ESG instruments to reduce CAPEX and OPEX.

- Mature sectors (food, phytotherapy, fertilizers), characterized by consolidated technologies, reduced CAPEX, and moderate growth.

- Emerging high-potential sectors (bioplastics, green building, bioremediation, sustainable textiles), with high CAGR, strong scientific interest, and medium-to-high investment requirements, but with significant return prospects.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- INSTM. Bilancio di Sostenibilità 2023: innovazione, ricerca e impatti delle attività. Available online: https://www.instm.it/bilancio_di_sostenibilita_2023_innovazione_ricerca_e_impatti_delle_attivita_instm.aspx (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- INSTM. Materiali sostenibili per l’industria. Available online: https://www.instm.it/materiali_sos_industria.aspx (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- European Commission. Circular Economy Action Plan. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:9903b325-6388-11ea-b735-01aa75ed71a1.0020.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Egamberdieva, D.; Nam, N.A.M. Potential Use of Licorice in Phytoremediation of Salt Affected Soils. In Plants, Pollutants and Remediation; 2019; pp. 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, B.; Bleischwitz, R. Resource Targets in Europe and Worldwide: An Overview. Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment, Energy 2015, 4(3), 597–620. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.M.; Alan, R.L. Performance of ash from Amazonian biomasses as an alternative source of essential plant nutrients. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 360, 132145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugaian, L. Circular economy: concepts and principles. J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 3, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, B.H. E-waste: An assessment of global production and environmental impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 408(2), 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zuhairy, M.A.H.M. Influence of different levels of liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra Inn.) and garlic (Allium sativum) mixture powders supplemented diet on broiler productive traits. Iraqi J. Vet. Med. 2015, 39(1), 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, H. The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun; London, 1923. [Google Scholar]

- Matthioli, P.A. The Discourses of M. Pietro Andrea Matthioli; Venice, 1712. [Google Scholar]

- Morese, G. The Lucanian Ionian landscape. Landscape History 2014, 35, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Saeed, S.M. The Pharmacology of Glycyrrhizin: A Review. Pharmacology 2018, 102(3), 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Market Research Intellect. Global Licorice Root Market Size and Forecast. Available online: https://www.marketresearchintellect.com/it/product/global-licorice-root-market-size-and-forecast/ (accessed on March 2025).

- Cerulli, A.; Pomponi, M.M.; et al. Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra, G. uralensis, and G. inflata) and Their Constituents as Active Cosmeceutical Ingredients. Cosmetics 2022, 9(2), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; Bilz, M.; Leaman, D.J.; Miller, R.M.; Timoshyna, A.; Window, J. European Red List of Medicinal Plants; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFO. Glycyrrhiza glabra. Available online: http://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-0000212813 (accessed on October 2025).

- Acta Plantarum. Flora d’Italia. Available online: https://www.actaplantarum.org/flora/flora_info.php?id=3582 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Pignatti, S. Flora d’Italia; Edagricole: Bologna, 2017; Vol. 2, p. 495. [Google Scholar]

- Chiavazza, P.M. Analisi dei componenti bioattivi estratti da radice di Glycyrrhiza glabra. ResearchGate. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313636482 _ANALISI_DEI_COMPONENTI_BIOATTIVI_ESTRATTI_DA_RADICE_DI_GLYCYRRHIZA_GLABRA.

- Nassiri-Asl, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Review of pharmacological effects of Glycyrrhiza sp. and its bioactive compounds. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22(6), 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, C.; Eisenhut, M.; Krausse, R.; Ragazzi, E.; Pellati, D.; Armanini, D.; Bielenberg, J. Antiviral effects of Glycyrrhiza species. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22(2), 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AF, A.-M. The physiological effect of liquorice roots on the antioxidant status of local female quail. Mesopotamia J. Agric. 2019, 47(1), 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, M. Study of flavonoid components in Glycyrrhiza glabra. Northern Pharmacology 2013, 10(7), 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. Glycyrrhizin and glycyrrhetinic acid: pharmacological and toxicological effects. Molecules 2015, 20(3), 6130–6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taarji, N.; Bouhoute, M.; Hafidi, A.; Kobayashi, I.; Neves, M.A.; Tominaga, K.; Isoda, H.; Nakajima, M. Interfacial and emulsifying properties of purified glycyrrhizin and non-purified glycyrrhizin-rich extracts from liquorice root. Food Chem. 2021, 333, 127949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makino, T.; Ota, M. History and the immunostimulatory effects of heat-processed licorice root products with or without honey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 292, 115108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panja, P.; Mukhopadhyay, M. A novel process for extraction of natural sweetener from licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) roots. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 63(3), 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-C.; Baek, J.-Y.; Lee, J.-M. Extraction of nutraceutical compounds from licorice roots with subcritical water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 63(3), 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmir, J.; Zaidul, I.S.M.; Rahman, M.M.; et al. Techniques for extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials: A review. J. Food Eng. 2013, 117(4), 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiman, A.; et al. Advancing the Physicochemical Properties and Therapeutic Potential of Plant Extracts Through Amorphous Solid Dispersion Systems. Polymers 2024, 16, 3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh Samani, B. Advanced Extraction of Glycyrrhiza. Nature (DOI not available). 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Durak, H. Hydrothermal liquefaction of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. (Liquorice): Effects of catalyst on variety compounds and chromatographic characterization. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 2020, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, D.R.L.H.D.J.M.D.M.F.J.J.J.A. Effect of plant density and depth of harvest on the production and quality of licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) root harvested over 3 years. N.Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2004, 32, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, H. Effects of Different Drying Methods on Drying Characteristics and Quality of Glycyrrhiza uralensis (Licorice). Foods 2023, 12, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattioli, E. Liquirizia. Nutrition Foundation Italia, 2024. Available online: https://nutrition-foundation.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Liquirizia-APB_3_24.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Ota, M.; Makino, T. History and the immunostimulatory effects of heat-processed licorice root products with or without honey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 292, 115108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panja, P.; Mukhopadhyay, M. A novel process for extraction of natural sweetener from licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) roots. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 63, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-C.; Baek, J.-Y.; Lee, J.-M. Extraction of nutraceutical compounds from licorice roots with subcritical water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 63, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmir, J.; Zaidul, I.S.M.; Rahman, M.M.; et al. Techniques for extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials: A review. J. Food Eng. 2013, 117(4), 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Mumper, R.J. Plant phenolics: Extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules 2010, 15(10), 7313–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xu, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Liang, H.; Lv, J. Preparative Purification of the Major Flavonoid Glabridin from Licorice Roots by Solid Phase Extraction and Preparative High Performance Liquid Chromatography. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K. Quality Control of Herbal Drugs: An Approach to Evaluation of Botanicals. In Business Horizons; 2008; ISBN 978-8190646710. [Google Scholar]

- Curci, M. Tesi di Laurea: Studio sulla liquirizia. Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, 2013. Available online: https://amslaurea.unibo.it/id/eprint/22133/1/Curci_Marco_tesi.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Avula, B.; Bae, J.-Y.; Chittiboyina, A.G.; Wang, Y.-H.; Wang, M.; Zhao, J.; Ali, Z.; Brinckmann, J.A.; Li, J.; Wu, C.-H.; Khan, I.A. Chemometric analysis and chemical characterization for the botanical identification of Glycyrrhiza species using LC-QTOF-MS. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 112, 104679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Chang, Z.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Hu, X.; Liu, H. Simultaneous Determination of Glycyrrhizic Acid and Liquiritin in Glycyrrhiza uralensis Extract by HPLC with ELSD Detection. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2007, 29, 2387–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmi, S.; Hatamipour, M.S.; Sadeh, P.; Najafipour, I.; Mehranfar, F. Activated carbon produced from Glycyrrhiza glabra residue for the adsorption of nitrate and phosphate: batch and fixed-bed column studies. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Yan, H.; Row, K.H. Simultaneous extraction and separation of liquiritin, glycyrrhizic acid, and glabridin from licorice root with analytical and preparative chromatography. Biotechnol. Bioproc. Eng. 2009, 13, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastorino, G.; Cornara, L.; Soares, S.; Rodrigues, F.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra): A phytochemical and pharmacological review. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32(12), 2323–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draelos, Z.D. Skin lightening preparations and the hydroquinone controversy. Dermatol. Ther. 2007, 20(5), 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sotto, A. La liquirizia: l’oro nero non sempre luccica. SIF Magazine, 2023. Available online: https://www.sifweb.org/sif-magazine/articolo/la-liquirizia-l-oro-nero-non-sempre-luccica-2023-06-29 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Noochuay, A.; Kumphai, P.; Suangtho, S.; Antika, K.S. Scouring Cotton Fabric by Water-Extracted Substance from Soap Nut Fruits and Licorice. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 535, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Deng, R.; et al. Agricultural Waste. Water Environ. Res. (DOI not available). 2013, 85, 1377–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinifarahi, M.; Yousefi, A.; Kamyab, F.; Jowkar, M.M. Effects of Organic Amendment with Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) Root Residue and Humic Acid on the Vegetative Growth, Fruit Yield, and Mineral Absorption of Bell Pepper (Capsicum annuum). J. Plant Nutr. 2024, 47(8), 1262–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamediyeva, D.; et al. Modeling the Use of Sweet Licorice Root to Improve the Physicochemical Properties of Saline Soils. AIP Conf. Proc., The 4th International Conference on Sustainable Engineering Techniques (ICSET), (DOI not available). Baghdad, Iraq, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Egamberdieva, D.; Ma, H.; Alaylar, B.; Zoghi, Z.; Kistaubayeva, A.; Wirth, S.; Bellingrath-Kimura, S.D. Biochar Amendments Improve Licorice (Glycyrrhiza uralensis) Growth and Nutrient Uptake under Salt Stress. Plants 2021, 10(10), 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarova, E.I.; et al. Advancing Carbon Adsorbents from Biomass: Physicochemical Analysis of Licorice Root Waste. AIP Conf. Proc., (DOI not available). 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Prestipino, M. IRIS UniMe Repository Record. 2022. Available online: https://iris.unime.it/retrieve/handle/11570/3105434/149914 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Fraunhofer Institute. Biomass Gasification – Conversion of Forest Residues into Heat, Electricity and Base Chemicals. Fraunhofer Publica Reports (DOI not available). 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, H. Decarbonising Bioenergy through Biomass Utilisation in Chemical Looping Combustion and Gasification. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21(5), 2893–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, M.; Abdel-Moneim, A.; El-Hafez, A. Valorization of Licorice Root Residues: Extraction of Bioactive Compounds and Potential Applications in Food and Nutraceuticals. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 412, 137002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Yu, C.; et al. Green Extraction of Flavonoids from Glycyrrhiza glabra Residues Using Ultrasound-Assisted Methods and Their Application as Natural Food Additives. Food Chem. 2022, 388, 132981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; et al. Circular Bioeconomy Approaches for Herbal Processing Residues: Case Study on Licorice Root Waste for Functional Food Applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 389, 129842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Substances Added to Food (formerly EAFUS): Licorice Extract (Glycyrrhiza spp.). 2025. Available online: https://www.cfsanappsexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=FoodSubstances&id=LICORICEEXTRACTGLYCYRRHIZASPP (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Cerulli, A.; Masullo, M.; Montoro, P.; Piacente, S. Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra, G. uralensis, and G. inflata) and Their Constituents as Active Cosmeceutical Ingredients. Cosmetics 2022, 9(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR). Safety Assessment of Glycyrrhiza (Licorice)-Derived Ingredients as Used in Cosmetics. Int. J. Toxicol. 2021, 40 Suppl. 1, 5S–29S. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.G. Herbal Cosmeceuticals for Scalp and Hair Care: An Overview. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. (DOI not available). 2020, 9(5), 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Fatoki, T.H.; Ajiboye, B.O.; Aremu, A.O. In Silico Evaluation of the Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Dermatocosmetic Activities of Phytoconstituents in Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.). Cosmetics 2023, 10(3), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, C.D.; More, R.U.; Bhandare, P.S. Hydrotropic Cream Preparation from Licorice Extract: Formulation and Skin Effects. Int. J. Trend Sci. Res. Dev. (DOI not available). 2019, 3(5), 707–710. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli, S.; Caviglia, M.; Pastore, G.; Marcantoni, E.; Nobili, F.; Bottoni, L.; Catorci, A.; Bavasso, I.; Sarasini, F.; Tirillò, J.; et al. Chemical, Thermal and Mechanical Characterization of Licorice Root, Willow, Holm Oak, and Palm Leaf Waste Incorporated into Maleated Polypropylene (MAPP). Polymers 2022, 14, 4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, S.; Das, A.K.; Matkawala, F.; Patidar, M.K. An Insight Overview of Bioplastics Produced from Cellulose Extracted from Plant Material: Applications and Degradation. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 5(4), 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Ke, T.; Zhu, H.; Xu, P.; Wang, H. Efficient Removal of Heavy Metals from Aqueous Solution Using Licorice Residue-Based Hydrogel Adsorbent. Gels 2023, 9(7), 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonker, S.F.; Azad, A.B.M.; et al. Recent Trends on Bioremediation of Heavy Metals: An Insight with Reference to the Potential of Natural and Microbial Systems. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21(12), 9763–9774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.Z.; Zhang, N.D.; Mao, M.Z.; Huang, K.T. Preparation of Bio-Absorbents by Modifying Licorice Residue via Chemical Methods and Removal of Copper Ions from Wastewater. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 84(12), 3528–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeo, L.M.A.C.S.D.L.P. Recovery of Vegetable Fibers from Licorice Processing Waste and a Case Study for Their Use in Green Building Products. Clean Technol. 2025, 7(3), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ). Additives in Tobacco Products: Liquorice Extract. 2012. Available online: https://www.dkfz.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Krebspraevention/Download/pdf/FS/FS_2012_PITOC_Additives-in-Tobacco-Products_Liquorice-Extract.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Lermines, E.L.L.R.G.C. Toxicologic Evaluation of Licorice Extract as a Cigarette Ingredient. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2005, 43(9), 1303–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santulli, C.R.M.P.D.G.S.T.L.M.E. Characterization of Licorice Root Waste for Prospective Use as Filler in More Eco-Friendly Composite Materials. Processes 2020, 8(6), 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeel, S.K.S.A.M.B.F.H.M.A.N. Sustainable Isolation of Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.)-Based Yellow Natural Colorant for Dyeing of Bio-Mordanted Cotton. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29(21), 31270–31277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.X.H. The Antimicrobial Potential of Plant-Based Natural Dyes for Textile Dyeing: A Systematic Review. UTEX Res. J. (DOI not available). 2024, 24(1), 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzicato, B.P.S.C.D.M.G.R.-M.M. Advancements in Sustainable Natural Dyes for Textile Applications: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28(16), 5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.Z.M.K.A.M.B.Z. Environmental Impacts of Hazardous Waste, and Management Strategies to Reconcile Circular Economy and Eco-Sustainability. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrielli, S.C.M.P.G.N.F.; Santulli, S.C. Chemical, Thermal and Mechanical Characterization of Licorice Root Waste in Composites. Polymers 2022, 14(20), 4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.Z.G.; Deng, Y. Enhanced Extraction of Flavonoids from Licorice Residues by Solid-State Mixed Fermentation. Waste Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 4481–4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamediyeva, D.; et al. Modeling the Use of Sweet Licorice Root to Improve the Physicochemical Properties of Saline Soils. AIP Conf. Proc. 2025, 3347(1), 020048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El Mageed, S.A. Integrative Application of Licorice Root Extract and Melatonin Improves Faba Bean Growth and Production in Cd-Contaminated Saline Soil. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25(26), 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DergiPark. Investigation of Flame Retardancy Effect of Licorice Root in Textile Applications. J. Textile Res. (DOI not available). 2023, 45(2), 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. 2020. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/6e6be661-6414-11ea-b735-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- European Commission. EU Bioeconomy Strategy Progress Report. (DOI not available). 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pharma, TES. Scientific Research Agreement between Foro delle Arti Srl, TES Pharma Srl and Fondo XGEN Venture. 2024. Available online: https://www.tespharma.com/news/solomeo-hamlet-of-arts-crafts-and-science/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Jafarzadeh, A.; Rahman, M. Glycyrrhiza glabra: A Comprehensive Review on Its Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 278, 114244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Journal of Plant Production. Current Status of Licorice Cultivation in the World. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2019, 13(4), 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Market Research Intellect. Global Licorice Root Market Size and Forecast. Available online: https://www.marketresearchintellect.com/it/product/global-licorice-root-market-size-and-forecast/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Maffè, S.; Paffoni, P.; Colombo, M.L.; Davanzo, F. Cardiotossicità da Erbe Selvatiche. G. Ital. Cardiol. 2013, 14(6), 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Application sector | Fiber treatment | Obtained characteristics | Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-construction and building materials [75,83] | Drying, grinding, mixing with natural binders (lime, gypsum, starches) | Thermal and acoustic insulation, lightness, breathability, good mechanical strength | Reduces the use of synthetic materials with high carbon footprint; contributes to sustainable construction and housing comfort |

| Eco-friendly paper and cardboard [63,78] | Mild mechanical or chemical pulping to separate cellulose; pressing and drying | Good mechanical strength, biodegradability, natural coloration without intensive bleaching | Alternative to virgin cellulose; reduces deforestation and valorizes agro-industrial residues |

| Agriculture and organic substrates [84,85,86] | Crushing, composting, direct use as soil amendment | High water retention capacity, supply of organic matter, improvement of soil structure, reduction of salinity | Improves soil fertility and resilience; supports crops under water or saline stress conditions |

| Sustainable textiles [79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87] | Extraction of natural pigments (water or eco-compatible solvents); use of raw fiber as reinforcement | Natural yellow-brown dyes, antimicrobial properties, potential flame retardancy | Provides ecological alternatives to synthetic dyes; enhances safety and durability of fabrics |

| Biodegradable packaging [75,78,83] | Drying, grinding, pressing; combination with biopolymers (PLA, starches) | Lightness, biodegradability, good mechanical strength, reduction of fossil-based plastics | Promotes the development of compostable and circular packaging; reduces the environmental impact of traditional plastics |

| Utilization sector | Estimated market value | CAGR (2025–2030) | Required CAPEX | Technological maturity (TRL) | Scientific interest | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fertilizer / Compost | ~€2 billion | 4–5% | Low (composting plants already widespread) | TRL 8–9 (consolidated technology) | Moderate: studies on organic amendments and biochar | ||||

| Biomass for energy | ~€10 billion | 6–7% | Medium-high (gasification/digestion plants) | TRL 6–7 (pilot/industrial) | High: research on bioethanol and bioenergy from lignocellulosic residues | ||||

| Food industry (flavorings, additives) | ~€12 billion | 3–4% | Low (extraction and standardization) | TRL 9 (consolidated use) | High: numerous studies on natural extracts and clean label products | ||||

| Natural cosmetics (shampoo, conditioner) | ~€50 billion | 5–6% | Medium (extraction and formulation lines) | TRL 7–8 (pre-commercial/industrial) | High: growing research on licorice bioactives (antioxidants, soothing agents) | ||||

| Phytotherapy (ointments, creams) | ~€8 billion | 3–4% | Low | TRL 9 (consolidated use) | Moderate: clinical and pharmacognostic studies | ||||

| Biomaterials / Bioplastics | ~€15 billion | 10–12% | High (biopolymer and compounding plants) | TRL 5–6 (advanced research, prototypes) | Very high: strong academic interest in lignin and cellulose from residues | ||||

| Bioremediation / Water purification | ~€200 billion | 7–8% | Medium (water treatment plants) | TRL 5–6 (pilot) | Very high: recent studies on natural adsorbents and licorice-derived biochar | ||||

| Eco-sustainable construction (Bio-construction) | ~€600 billion | 8–9% | High (production lines for panels and composites) | TRL 6–7 (pilot/industrial) | Very high: works by Madeo et al. (2025) and others on biocomposites | ||||

| Smoke filtration (extracts, not residues) | ~€5 billion | Stable (0–1%) | Low | TRL 9 (consolidated use) | Low: few studies, more related to additives than residues | ||||

| Textile industry (fiber, dye, antimicrobial) | ~€40 billion | 6–7% | Medium (natural spinning and dyeing plants) | TRL 5–6 (research and prototypes) | High: recent studies on natural dyes and plant fibers | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).