1. Introduction

Rain is frequently accompanied by wind, and indeed it has been argued that “.. wind-driven rain is the primary form of natural rainfall.” (An et al. 2022, p2) [

1]. This ‘wind-driven rain’ (hereafter WDR) typically exhibits drop trajectories that are not vertical, as seen in still air, but which approach the ground obliquely. Whilst wind and rain are recorded as separate parameters at meteorological ground stations, their combined influence on rain droplet trajectories is not usually recorded or analysed. Likewise, the angle of inclination of WDR is not routinely recorded, despite its significance, which is considered further below. This is likely to reflect the lack of suitable apparatus for recording the angle at which droplets following oblique trajectories strike the ground. A solution to this is introduced in the present work.

In the context of fields including geomorphology, pedology, and hydrology, two key attributes of WDR are the angle (or inclination) of oblique arrival of drops deflected by the wind, and the potentially greater impact velocity and droplet kinetic energy conferred by wind acceleration of the droplets. In WDR, drop speeds can exceed their still-air terminal fall velocity. Particularly if the wind vector at the ground surface is directed broadly in the upslope direction, upslope splash transport and particle creep may exceed downslope transport, and surface runoff may be slowed by the upslope wind and droplet-impact drag. The reverse may occur with downslope-directed WDR. Infiltration and sediment transport in overland flow can both also be affected. Additional details are provided in

Section 1.2. Before introducing the new apparatus for recording rain inclination, we begin with some necessary additional background to the characteristics of WDR.

1.1. The Behaviour of Rainfall Affected by Wind

Given that terminal raindrop fall speeds in still air are < 10 m s

-1 even for very large drops of 5 mm diameter (Gunn and Kinzer 1949) [

2], horizontal wind speed can easily exceed the droplet fall speed. A wind speed of 10 m s

-1 only reaches the ‘fresh breeze’ category in the Beaufort scale. The ‘strong breeze’ class extends to 13.6 m s

-1, and ‘gale’ extends to > 20 m s

-1. Tropical cyclones traversing Queensland, Australia are frequently associated with heavy rainfall and large total depths. Direct observation has shown that peak 10-minute wind speeds can exceed 50 m s

-1 (O’Grady et al. 2024) [

3]. Clearly, wind speeds can greatly exceed the terminal velocity of even the largest drops, such that drops can strike the ground surface or vegetation not only obliquely but also at considerable speed.

This can be understood from the finding that horizontal speeds of droplets deflected by wind tend broadly to match the wind speed (Fu et al. 2015 [

4], Lu et al. 2019 [

5]), with scatter in the relationship to be expected as a result of wind gustiness, turbulence, and the drop size distribution (DSD). Departures of droplet speed from wind speed can occur because wind speeds may be lower close to the ground than at higher elevations where surface frictional drag is less. As a result of their inertia, larger droplets falling toward the ground from areas of higher wind speed aloft may have a horizontal speed that exceeds the wind speed close to the ground (Fu et al. 2015 [

4]), and will be deflected less by the wind. Nevertheless, the speeds of droplets up to 5 mm diameter can track fluctuating wind speeds quite rapidly, over just seconds, though smaller drops respond more rapidly than do larger ones (refer to data presented in Figure 5 in Fu et al. 2015 [

4]).

Under steady, unidirectional wind, and assuming that the drop velocity matches the wind speed fairly closely, the angle of inclination of the drop trajectories toward the ground

(usually expressed in terms of angle of departure from the vertical) can be estimated as the vector sum of the wind speed (v, ms

-1) and the fall speed of a droplet (normally taken as the still-air fall speed, u, m s

-1). Thus, the angle of inclination from the vertical is given by

The trajectory of a droplet having a terminal velocity of 6.5 m s

-1 in a wind of 1.5 m s

-1 would thus nominally be inclined at ~ 13° from the vertical. Van Heerden (1961) [

6] argued for the term ‘deviation’ for oblique drop trajectories, to emphasise that it was a departure from the ‘normal’ vertical trajectory. This term appears not to have found common use in the literature, and angle specified in Equation [

1] is referred to here as the inclination of the rain.

Because u can take the same value as v, the inclination of droplet trajectories from the vertical can readily reach 45° or more. For instance, a 1 mm diameter droplet has a terminal velocity of ~ 4 m s

-1, and reaching

= 45° therefore only requires a wind speed of ~ 4 m s

-1 (~ 14 km h

-1). To reach 45° inclination, even a larger 4 mm drop would require a wind speed of only ~ 9 m s

-1 (~ 32 km h

-1) in the Beaufort ‘fresh breeze’ range. Mean monthly 3 pm wind speeds at Cairns, Australia (in the trade winds region where the rain inclination data reported below were collected) lie between 4–5.5 m s

-1 (15–20 km h

-1) but a significant proportion lie between ~ 5.5 m s

-1–8 m s

-1 (20–30 km h

-1)(Bureau of Meteorology, Australia, 2025 [

7]) Thus, it is to be expected that during trade wind showers in this region, or in other wind-exposed areas globally, many droplets arrive obliquely at the ground. Belcher et al. (2023) [

8] presented a climatology of extreme WDR for the south-eastern USA. They reported that 50-year return period winds concurrent with moderately intense rain of ≥ ~ 15 mm h

-1 exceeded 45 m s

-1. Under those conditions, even a very large drop with a terminal velocity of 10 m s

-1 would be deflected more than 77° from the vertical (a very oblique trajectory inclined at just ~ 13° from level ground). Thus, in areas of the world where there are persistent winds, such as the trade wind belts, WDR must be common and rain inclinations can be very steep indeed.

Figure 1 illustrates the form of the relationship between

and wind speed for droplets of 1.5 mm diameter and wind speeds to 10 m s

-1, based on droplet terminal velocities from Gunn and Kinzer (1949) [

2]. This assumes a wind parallel to the ground and that droplet fall speed is unaffected by the wind. The relationship becomes flatter at higher wind speeds as the droplets asymptotically approach alignment with the horizontal wind vector and each increment in wind speed contributes a diminishing increase droplet speed. The relationship in

Figure 1 is unlikely to correspond exactly to droplet behaviour in nature. This is not least because whilst falling, the larger droplets deform and depart from the spherical form of very small droplets, thereby increasing the drag coefficient through the air (Lu et al. 2019) [

5]. Deformation is likely to be reduced for a droplet moving at the same speed as the air, owing to lack of frictional drag. Thus, it cannot be assumed that droplet fall speeds in windy conditions correspond with still-air values determined experimentally. For instance, Testik and Bolek (2023) [

9] reported that of almost 27,000 drops measured in a study in Texas, USA, 18.5% showed sub-terminal fall speeds, and 9.5% were super-terminal, effects that were related to the influence of wind and turbulence. Drop speeds may also be affected by other microphysical processes, including drop oscillation, that again influence frictional drag effects (Testik and Barros 2007) [

10]. Testik and Pei (2017) [

11] used data collected in Okalhoma USA, using video and Parsivel disdrometers, to show that as wind speed increased small droplets became more common and large droplets less common. They concluded that the reduced number of large drops in higher wind speeds was attributable to the collisional breakup of drops. The resulting changes in the DSD with wind speed, especially when wind speed fluctuates, and linked with the mix of sub- and super-terminal drops (Montero-Martínez and García-García 2016, [

12] Testik and Bolek 2023) [

9] make the estimation of DSDs from empirical relationships linking DSD and intensity (e.g., as employed by Herwitz and Slye 1992) [

13], or using other empirical relationships that neglect wind and turbulence in order to estimate rain inclinations, considerably less certain. The details of how these effects on droplet behaviour vary with wind speed and other atmospheric conditions, including air density, remain in need of additional study.

Given the range of drop diameters present in rain, it can be reasoned that WDR includes droplets falling at a range of inclinations. The smallest droplets can often be seen blowing almost horizontally. Van Heerden (1961) [

6] described the ‘waves of mist’ (comprised of these small droplets) that can be seen passing though oblique rain composed of larger drops. Given the apparatus used, with gauges mounted at multiple angles of tilt (see Plate 1 in Van Heerden 1961) [

6], he indicated that measurement of the inclination of rainfall could be based on the inclination at which the largest event rain depth is recorded.

1.2. What Effects Arise at the Soil Surface During WDR?

The focus of this paper is on a new measurement technique. However, a brief commentary on the impact of WDR at the landsurface is provided to illustrate some important aspects of the geomorphic and hydrologic significance of WDR.

The angle at which the droplets finally strike the ground depends on the gradient of the landsurface, and the relative directions of the maximum slope direction and the incident wind azimuth. Hillslopes directly facing the wind would experience smaller effective rain inclinations at the ground, and on steep slopes facing the wind, WDR could strike orthogonally to the ground. More complex conditions can arise in the landscape, where not only does hillslope steepness and azimuth of fall vary, but also the wind and WDR can be steered by interaction with topographic barriers, the orientation of valleys, etc. (Hamilton 1954, [

14] Sharon 1980, [

15] Mao et al. 2023) [

16]. The importance of exposure to WDR in relation to landform and geomorphic development has been illustrated from a field study of biancana badlands (Tuscany, Italy, Marsico et al. 2021 [

17]), and in relation to rill cutting on spoil heaps (Belgium and France, Beullens et al. 2014 [

18]).

Experimental studies of processes including soil splash have established that in WDR, the kinetic energy of rain can be larger than expected for still air (Pedersen and Hasholt 1995 [

19], Helming 2001 [

20]) however as just noted, the impact at the ground depends on the topography. Thus, slopes facing the wind may experience increased splash detachment of soil particles, though the speed of overland flow may be lower owing to the upslope-directed wind (Schmidt et al. 2017 [

21], An et al. 2022, [

1] 2023 [

22]). Slopes inclined away from the wind can experience reduced droplet impact and rainfall intensity. Rather than being carried out in the field under natural rain and wind, the available studies seeking to understand and quantify splash and sediment transport under WDR have primarily been made in indoor flumes where simulated wind and rain can be generated together using fans and spray nozzles (Lyles et al. 1969 [

23], Lyles 1976 [

24], Erpul et al. 2003 [

25], 2004 [

26], An et al. 2022 [

1], Kalehhouei et al. 2023 [

27], Fidari et al. 2024 [

28]). Portable wind and rain facilities have also been used on soil surfaces in the field (Ries et al. 2014 [

29], Kuhn et al. 2014 [

30]), sometimes with wind erosion and water erosion studied separately, in an attempt to evaluate their relative importance (Marzen et al. 2019 [

31]). These studies have contributed an understanding of the diverse outcomes of WDR at the soil surface, and highlighted the importance of WDR to various surface processes. For instance, Lyles et al. (1969) [

23] showed that up to 66% more soil mass was dislodged from clods exposed to rain and wind at 13.4 m s

-1 than under rain of the same intensity but without wind. Despite findings such as this, flume studies do not fully capture all important aspects of natural events, where there may be intensity bursts during rainfall, strong wind gusts rather than constant wind speeds (Choi 2001 [

32]), and a three-dimensional landsurface. Intensity bursts can be critical to particle dislodgement (Dunkerley 2019 [

33]), and it is important to recall that in nature, wind gusts, with attendant changes in rain inclination and raindrop kinetic energy, are likely to be virtually ubiquitous and to add to the local variability of rain impact at the soil surface. Furthermore, as emphasized by Ries et al. (2014) [

29], flume studies generally use trays or flumes of repacked soil, with no vegetation or litter cover, and no realistic microtopography, macropores from faunal activity, intact biological soil crusts, intact distributions of pore sizes, or other features relevant to surface processes. Measurements of splash under natural rainfall, made using splash cups or similar methods to record particle motion (Pedersen and Hasholt 1995 [

19], Zambon et al. 2020 [

34]), are less common and have lacked a means to record the changing inclination of rain during storms. In pioneering work on rainfall in hilly terrain, Sharon (1980) [

15] pointed out that rain inclination cannot be regarded as constant under natural storm conditions.

1.3. WDR Is Typically Not Targeted in Field Experiments Using Rainfall Simulation

Experimental studies of hydro-geomorphic processes of infiltration, surface runoff, and sediment entrainment and transport made in the field would ideally be made under natural rainfall (Liu et al. 2022) [

35]. However, controlled experimental conditions are often preferred, and frequently rely on constant-intensity rainfall simulation over small experimental plots. Generally, wind is of necessity excluded through the use of shields and other forms of enclosure (Williams et al. 1998 [

36], Humphry et al. 2002 [

37], Sangüesa et al. 2010 [

38], Lascano et al. 2019 [

39], Lazarus et al. 2023 [

40]) such that the droplets fall vertically toward the soil surface. This is done in order that the simulated rain is not swept aside to fall partly outside the margins of the experimental plot. However, the exclusion of wind also precludes the documentation of the potentially important role of WDR in surface processes. One of the very few studies that provide direct observational evidence of the role of WDR observed in the field is the work of Vieira et al. (2004) [

41] in Portugal. This study used marked tracer particles to document upslope particle transport under WDR driving in that direction. Clearly, the incorporation of wind effects (and WDR) in field and laboratory rainfall simulation studies would better reflect the conditions commonly found in nature. The laboratory flume studies that have included both fan-driven wind and rainfall simulation appear to be vastly out-numbered by field and laboratory studies where simulated rain alone is used, with wind exclusions and drops all falling vertically to the ground surface or soil tray. The geomorphic and hydrologic effects of WDR therefore warrant additional study, and this would be most informative if carried out under field conditions where the various microphysical influences on DSD discussed earlier, together with wind gustiness and rain intensity fluctuations, would automatically be incorporated. The limited attention to WDR in areas such as soil erosion is reflected in published literature, as a few examples will show. In their analyses of raindrop impact and interrill erosion, Nouhou Bako et al. (2016 [

42], 2017 [

43]) did not mention wind, only considering vertical drop impacts. A review of rainfall, erosion and sediment transport (Giráldez et al. 2022 [

44]) includes only a single paragraph on wind effects. A discussion of global rainfall erosivity scenarios for 2050 and 2070 (Panagos et al. 2022 [

45]) does not mention wind or WDR at all, despite the evident importance of WDR and the documented secular changes in global wind speeds (Zeng et al. 2019 [

46], Zha et al. 2021 [

47]) and related changes in DSDs and kinetic energy at the soil surface that may well influence future erosivity.

1.4. Some Hydrologic Effects of WDR

In addition to effects on overland flow, particle splash, and sediment movement, there are further hydrological roles for oblique WDR. For example, Herwitz and Slye (1992) [

13] working in North Queensland, Australia, documented changes in stemflow production on rainforest trees under wind-driven rain. This could be anticipated as under WDR, the trunk or foliage area that interacts with rain droplets is not the vertically projected area, but the potentially much larger area exposed to oblique rain falling through canopy gaps. A similar study was reported by Van Stan et al. (2011) [

48], who investigated stemflow from WDR on temperate tree species in eastern North America. In both studies, rain inclinations were based on calculated median drop diameters and observed wind speeds, rather than by direct measurement. This applies also to the nomograph presented by de Lima (1990) [

49], for which drop diameters and wind speeds are assumed to remain constant in time.

The foregoing brief review points to the potential value of further field-based studies of the surface processes under WDR. The present paper presents the design and deployment of a novel and relatively inexpensive apparatus that allows rain inclination to be monitored continuously in the field and logged into data files. Some field data are presented to illustrate the performance of the new device. The instrument is small and readily portable by hand in the field. The variation of rain inclination during a rainfall event can be recorded at intervals of seconds, and statistics of the rain inclination (mean, variability, maxima, and so on) can be calculated and employed as explanatory variables in studies of infiltration, overland flow, sediment movement and related surface processes. This device provides researchers with the opportunity to record rain inclination adjacent to experimental runoff or erosion plots, thereby acquiring more useful information than can be obtained from a rain gauge alone.

2. Approaches to the Measurement of Rain Inclination

Brief comments are provided on prior methods used to estimate rain inclination.

The recording of WDR, especially on hillsides exposed to strong wind, has long attracted research attention (Koschmieder 1934 [

50], Pagliuca 1934 [

51], Riesbol 1938 [

52], Hayes 1944 [

53], Helmers 1954 [

54], Poreh and Mechrez 1984 [

55]). Many variant rain gauge designs have been tested in the field—as is well illustrated in the photo of a very diversely instrumented slope on “Rain-gage hill” in California (Storey and Hamilton 1943 [

56]).

Direct measurements of rain inclination have been based on the use of paired or multiple gauges, one of whose orifices was set horizontal (as in a standard meteorological rain gauge) and the other rotated 90°, so that the orifice opening was in a vertical plane. This latter gauge would collect little or nothing in still air, and an increasingly large catch from rain inclined at an angle to the vertical. The relationship of equation [

1] could then simply used in the form where the rain vector was computed from the two recorded rainfall depth, as follows:

where

is the rainfall depth (mm) recorded by the gauge with a vertical orifice, and

is the rainfall depth (mm) from the gauge with a conventional horizontal orifice. A dual-orifice gauge of the form just described can be seen in Figure 7 of Hamilton (1954) [

14]. A few results from gauges of this kind are presented here by way of illustration. Hamilton (1954) [

14] presented rain inclination data from the San Gabriel Mountains northeast of Los Angeles (California, USA). He reported that northerly storm events (that had less intense rain and lower wind speeds) had a mean inclination of 19° from the vertical, while more intense southerly storms had a mean inclination of 35°. From data collected at Pretoria (South Africa), Van Heerden (1961) [

6] reported inclinations in the range 10°–47°. At a field site 21 km north-east of Wellington, New Zealand, Aldridge (1975) [

57] employed a vectopluviometer to record inclinations extending to > 70° from the vertical, although more commonly values were < 45°.

A vectopluviometer is used to record wind direction as well as rain inclination. Both parameters are important in hilly or rugged terrain. Figure 8 in Hamilton (1954) [

14] shows a vectopluviometer with four vertical orifices as well as one horizontal orifice, designed to record also the azimuth from which the inclined rainfall arrived. This is the type of device used by Aldridge (1975) [

57]. There are other forms of vectopluviometer, such as the ‘pole vectopluviometer’ described by Crockford et al. (1991) [

58] that directed rain intercepted by a vertical, grooved pole ~ 2 m tall into several separate containers fed by sectors of the pole facing different compass directions, and from which the intercepted rain depth could be measured. A separate standard gauge was used to represent the horizontal orifice. There have been vectopluviometers that act as wind vanes, such that the vertical orifice always faces directly into the wind (refer to the photograph in

Figure 1 of Van Heerden 1961) [

6]. Other similar devices were used by Storey and Hamilton (1943) [

56], Lacy (1951) [

59], Rose and Farbrother (1960) [

60] and others. Frumau et al. (2011) [

61] presented a further gauge design, and collected data allowing rain inclination to be related to wind speed, the relationship showing wide scatter (refer to their

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Camuffo et al. (2022) [

62] illustrated a number of contrasting devices (refer to their

Figure 1). None of these earlier devices allows rain inclinations to be monitored continuously during a WDR event, all being dependent on the volume of rain caught in some nominated interval.

In some prior studies, rain inclination was calculated on the basis of an estimate of the median drop size in rain, and the mean wind speed. Herwitz and Slye (1992) [

13] used this approach for instance to estimate an inclination value for a day for which a mean wind speed value was estimated from the total daily wind run (645.3 km, equivalent to a mean of ~ 7.5 m s

-1). Median drop size was estimated from rainfall intensity using the empirical relation set out by Laws and Parsons (1943) [

63], and the corresponding fall velocity was then estimated from the data of Gunn and Kinzer (1949) [

2]. The estimated mean rain inclination reported by Herwitz and Slye (1992) [

13] was 51.6° from the vertical.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Designing a New Instrument for the Acoustic Recording of Rain Inclination

Considerable interest in acoustic methods for observing and recording rainfall has developed in recent years (Trono et al. 2012 [

64], Ferroudj et al. 2014 [

65], Guico et al. 2018 [

66], Avanzato and Beritelli 2020 [

67], Dunkerley 2020 [

68], 2022 [

69], 2023 [

70], Chen et al. 2022 [

71], Wang et al. 2022 [

72], 2024 [

73], Emmanuel et al. 2023 [

74], Alkhatib et al. 2024 [

75], Xavier et al. 2024 [

76]).

Given the success of acoustic measurement of rainfall arrival, that can easily achieve a temporal resolution of seconds (Dunkerley 2023) [

70], this method was extended to the measurement of rain inclination. As shown above, the resolution of rain vectors has previously only been attempted using measured rain gauge catches after a prolonged period (e.g., rainfall event, calendar day) of rain. In the new method proposed here, the continuous recording of inclination during rainfall is achieved by solving the rain vectors every few seconds, or other interval, as required. The apparent sound intensity on two matched acoustic sensors, one mounted horizontally and the other vertically, provides the data. The acoustic signal (a voltage output suitable for data logging) is analysed instead of the rainfall depth recorded through a much longer time. The relationship is:

where

is the rainfall acoustic signal (volts) recorded by the sensor with a vertical droplet detection surface, and

is the rainfall acoustic signal (volts) from the gauge with a horizontal droplet detection surface.

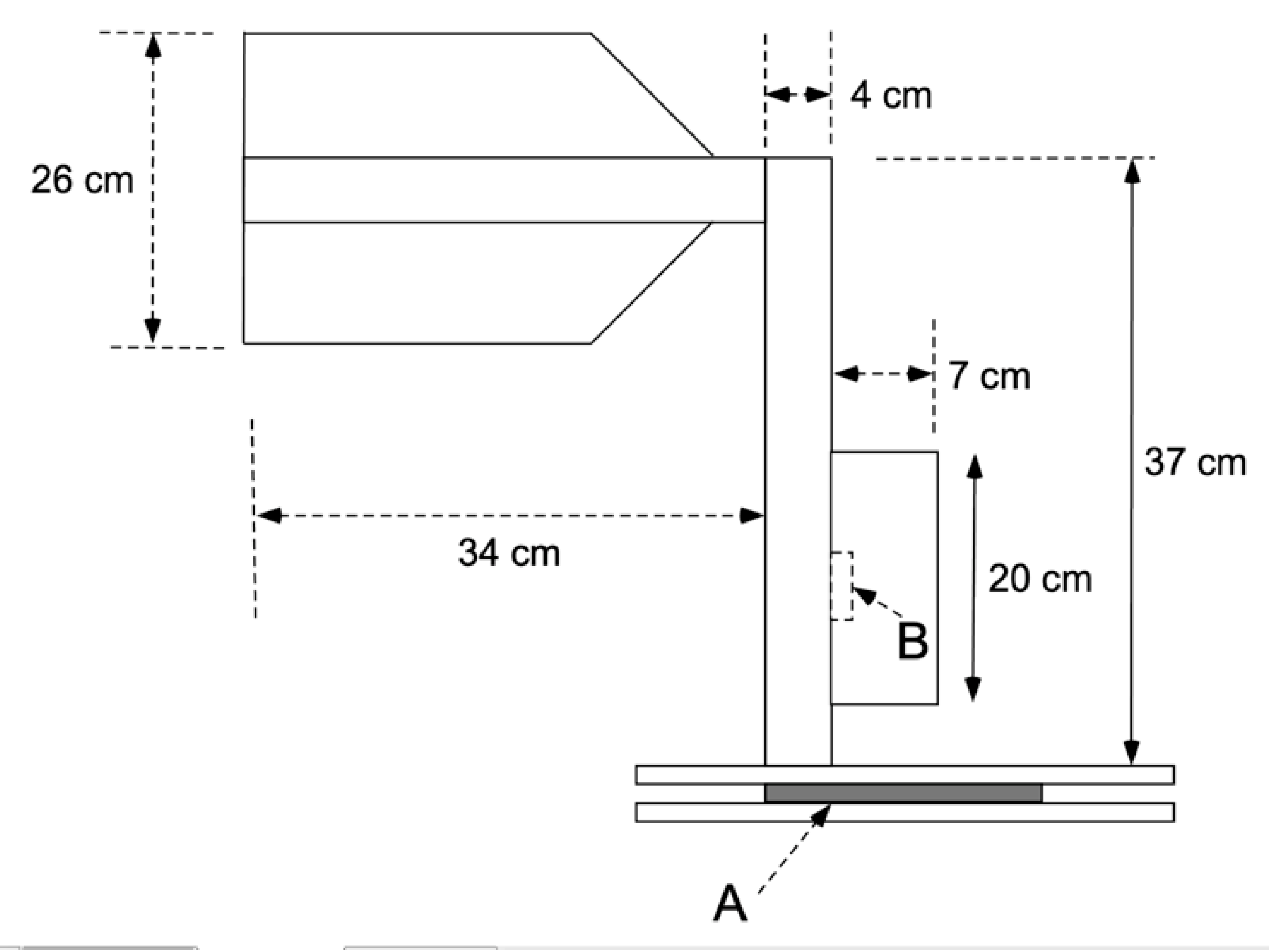

3.2. The Acoustic Sensors

The acoustic sensors consisted of a polymer drum skin 200 mm in diameter, mounted on a circular wooden drum frame (

Figure 1). A tightly-strung, resonant drum skin produces a loud impact sound when struck by even a small falling water droplet. Each drum skin was then fitted tightly over a PVC cylinder of appropriate tight-fitting diameter. The cylinder was closed by a circular plate at one end, in order to form a closed chamber in which sound energy reflected from the closed end prolonged vibration of the drum skin. Mounted within the base of the PVC cylinder was a small circuit board containing an electret microphone capsule and associated electronic amplification and signal processing circuitry, the microphone facing outwards toward the drum skin. Power and signal cables were routed through a waterproof cable gland mounted on the base of the PVC cylinder. The physical dimensions and construction of the two acoustic sensors were the same, with identical drum skins, microphones, and amplifier circuitry were used in both. This is an important aspect of the method: the two acoustic sensors must have the same performance characteristics. Therefore, the amplifier gain in the two acoustic sensors was set not using adjustable potentiometers as might often be done, but rather using fixed-value, 1% tolerance resistors (470 k ohm) having low resistance change with ambient temperature. Adjustable gain would increase the difficulty of ensuring that both sensors had the same response to drop impacts.

The acoustic sensor signal is the sum of the sounds generated on the drum skin by all incident drops striking the surface at any moment, and the energy reflected toward the drum skin by the other, closed end of the acoustic enclosure. However, blowing mist droplets of very small size produce effectively no impact sound. According to Dunkerley (2021) [

77], in rain at 5 mm h

-1, typical drop arrival rate can reach ~ 3700 impacts m

-2 s

-1 so that any period of 1 s, in still air there would be up to ~ 100 drops striking the area of the 200 mm diameter horizontal sensor. Large drops produce a large sound signal, and smaller drops, a smaller sound signal. The overall voltage output is therefore affected by the DSD of the rain. However, because the calculation of rain inclination depends on the ratio of the two acoustic transducer signals, and not their absolute values, it is not directly affected by rainfall intensity nor by DSD, provided the droplet arrival rate is sufficient to generate a measurable voltage, and the two sensors are sufficiently close together that they record the same rainfall field. In heavier rain, the acoustic signal is simply larger for both sensors, and the ratio of the two output voltages, which is proportional to the rain inclination (equation [

3]), is essentially unchanged.

The circuitry within the acoustic sensors included some amplification of the microphone signal, a precision rectifier to convert the AC signal to DC to suit a voltage data logging system, and an envelope follower circuit as described by Dunkerley (2020) [

68]. The voltage output from the envelope follower tracks the peak signal voltage. This output was logged by an in-house data logging system that wrote the microphone signal voltage, at any nominated interval, to an SD card. A file name was also automatically created from the date and time that the logging commenced. This was stored on the card, as were the full Gregorian date and time, with resolution of one milli-second, for each logged microphone voltage signal. The logger scan interval could be set to any value from a few ms to minutes or hours. The logger was housed in a weatherproof instrument case, with all cables routed through waterproof cable connectors to the acoustic sensors placed on the ground nearby. The entire system was powered from a 12 V battery. In the field, this allows the use of power derived from a motor vehicle via the cigarette lighter socket or directly from the battery. A 5 V regulator was used to supply the power required by the microphone circuitry within the acoustic sensor housing. Signal voltages were logged with an analog-to-digital converter resolution of 12 bits, equivalent to ~ 0.1 mV. To achieve this, a separate, temperature-compensated precision 5.0 V voltage reference circuit (AD584, Analog Devices Inc., USA) was used to supply an external reference voltage to the data logger. The logging system was based on an Arduino model R4 Minima, running at 48 Mhz. An SD card having 32 Gb storage capacity was used. A separate, battery-backed real-time clock circuit was employed to provide calendar and timing data, and this was calibrated against the internet time standard (NIST) prior to each field deployment.

The face of the vertical acoustic sensor must be oriented directly into the wind. Owing to turbulence and gustiness, the direction is never strictly constant. A rotating platform was therefore built (

Figure 1) with a vertical shaft to which the acoustic sensor was attached. A large wind vane was fabricated from light and weather-resistant core flute material, and attached to the rotating platform. This was able to respond rapidly to changes in wind direction, and to keep the acoustic sensor facing in the direction of drop arrival. The horizontal acoustic sensor located 50 cm away remained in a fixed position. Dimensions of the rotating vertical acoustic sensors are shown in

Figure 2.

Less than two meters from the acoustic sensors, wind speed (Rika Sensor 3-cup anemometer, model RK100-02) and direction sensors (Rika Sensor wind-direction sensor, model RK110-02) were mounted at about the same height above the ground. These both generated signals in the range 0–5 V, logged on a separate in-house data logger of the same design as used for the acoustic data, and also housed in a weatherproof enclosure. The clocks of both data loggers were synchronised prior to data collection, and both loggers were set to the same scan interval. A tipping-bucket rain gauge was also located within 2 m of the acoustic sensors. This gauge had a sensitivity of 0.2 mm, and was used to estimate rainfall rates from the unaggregated inter-tip times of the bucket mechanism (Dunkerley 2024) [

78]. The rain gauge data logger clock was synchronised to those of the acoustic sensor logger and the wind sensor logger before each deployment.

At the conclusion of a period of observation, the SD cards were removed and the data read into Excel files for further processing, including the calculation of rain inclinations for every data point, and the calculation and graphing of running means of the acoustic sensor voltages.

Data files at the 2 s scan intervals used here occupied approximately 90 kB h

-1, which is small in comparison with full audio recording at 41 kHz, which commonly results in file sizes in the Mb min

-1 range, or Gb per day. Fortunately, full audio recording of acoustic data is not necessary to record rainfall arrival and to estimate intensity, as reported by Dunkerley (2023) [

70].

It may be useful to provide an indication of the cost of components for the complete acoustic system as deployed here. Neglecting labour costs for fabrication and assembly, this amounts to about A$400, which includes the two data loggers and their SD data cards.

3.3. Effect of Wind Obstruction by the Vertical Acoustic Sensor on Droplet Deflection

The vertical acoustic sensor faces directly into the wind. Though the sensor diameter is small, the flat surface undoubtedly disrupts airflow to some extent. This phenomenon has been widely-studied in relation to the measurement of WDR on building facades (Yu and Zheng 2025 [

79]). The stalling of airflow, or deflection around the edges of an obstacle, are known to affect small (low-mass) droplets more strongly than large droplets (Karagiozis et al. 1997) [

80]. Though there are computational models of these processes under restricted conditions such as unidirectional airflow, there has been no validation by direction measurement in the field. It has to be assumed that the vertical acoustic sensor would deflect airflow to some extent, and hence cause some droplets to be swept aside and past the sensor, and not be measured acoustically. Large drops, having the greatest mass and momentum, would be deflected least. This is advantageous for the present method, since the large drops probably account for most of the impact energy and resulting microphone signal. Planar vertical rain collectors of about the same size as the current acoustic sensors are almost universally relied upon for measuring WDR on the vertical faces of buildings (Blocken and Carmeliat 2006) [

81].

In the present method, however, there would be little effect on droplet trajectories from the horizontal sensor, which lies close to and parallel with the ground surface. Recall that a ratio calculation is used here to calculate rain inclination (eqn. 3). Thus, it is possible that the vertical sensor signal is slightly smaller than it would be in the absence of the effects of the sensor on airflow and droplet impact on the sensor. This means that any rain inclination calculated using eqn. 3 will result in an under-estimate of rain inclination. In other words, the values reported below from field trials of the new device provide conservative estimates of rain inclination, which must be at least as large as calculated, but which might actually be somewhat larger.

3.4. Field Deployment and Data Collection

The new device was deployed for testing and evaluation at a field station near the township of Millaa Millaa, located on the Atherton Tablelands of far northern Queensland, Australia. The site was located about 40 km inland (westward) from the coastline, which for much of the year is exposed to south-easterly trade winds. The field site has an annual rainfall of ~ 3000 mm, and during the trade winds, the rain can readily be observed to fall at an oblique angle, comprising persistent WDR. Mists of fine droplets blowing almost horizontally are also frequently observed. The field site was only about 15 km from the site used for data collection by Herwitz and Slye (1992) [

13] already referred-to. The area is dominantly covered in tropical rainforest, but the acoustic and other instruments were set up in a large area of mowed grass on a private property, on an elevated area to which the trade winds had unobstructed access. The field site was located at ~ 700 m above sea level. Data were collected over several months in 2025.

Some hours of acoustic sensor data were also logged during rainless periods but when the trade winds were still blowing. This was done to assess the extent of any sensitivity of the device to wind noise, or to vibration generated as the vertical sensor rotated on the wind vane to which it was attached. This moved on smooth ball bearing races, and little vibration was expected, but field tests were undertaken to verify the extent of any noise. Indoor tests were also conducted to document any small residual voltage generated by the circuitry in rainless, calm conditions.

3.5. A Note on Data Processing

As shown in equation [

3], the rain inclination is calculated from the ratio of the voltages from the two acoustic sensors. During rain, and with the particular amplifier gain settings used in the present study, these voltages were normally in the range 0.5–3 V. However, the voltage signal from blowing mist or very light drizzle, especially during periods of moderate wind speeds, was near the limit of detection. Under these conditions, small output signals of up to 40 mV could be generated by both sensors (partly comprised of residual noise in the electronic circuitry), and being close to the same value, these small signals would tend always to indicate an inclination of ~ 45°. Being located within sealed enclosures, the acoustic sensors were largely shielded from external noise, but this shielding still allowed very small signals to be generated by nearby noise sources. Small residual signals of a few tens of mV could be caused by nearby bird vocalisations, vehicle noises, etc., but only if they were active during the brief moment when the signal voltages were logged. Such small signals could still be present during periods of intermittency, when there was no rain and hence no inclination. During periods of silence and no rain, perfect noise-free amplifiers protected from all ambient noise, would generate a signal of 0 V, and the ratio of the two sensors would then be indeterminate. For all these reasons, only when voltages > 0.04 V were generated simultaneously by both acoustic sensors were the data used for the calculation of inclination. Gaps in the processed inclination records thus reflect either the temporary cessation of rain (intermittency), or else periods of drizzle or blowing mist incapable of generating a sufficiently large acoustic signal.

At the 2 s logger scan interval used in the field trials, the data amount to 7200 data points per hour of data collection: 1800 readings for each channel (horizontal acoustic sensor, vertical acoustic sensor, wind speed, and wind direction). To aid interpretation, the volume of data was reduced, and the signals smoothed, by the use of 5-minute running means fitted to the raw data. This reduces the complex cloud of data points that otherwise makes plots of data less easy to read and interpret. The raw voltage signal from the horizontal acoustic sensor is retained in some diagrams, to illustrate the temporal resolution that it is possible to achieve.

4. Results

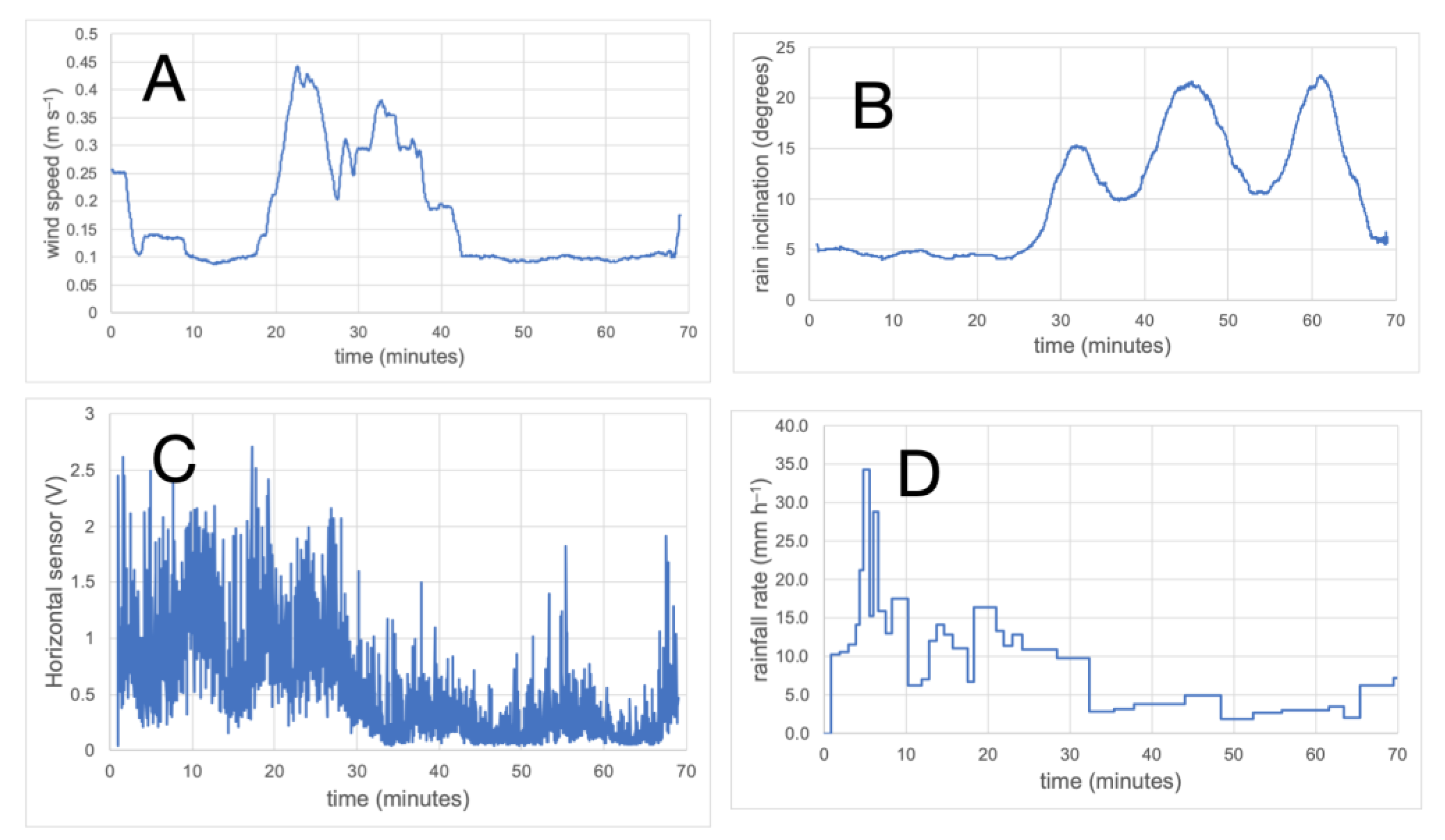

Tests of instrumental noise resulting from wind alone are presented first, followed by two sets of field measurements, one on a windy day with rain of low to moderate rainfall rates (13 August 2025) and the second on a day of light winds and rainfall of varying rate, including a period of quite high intensities (1 August 2025).

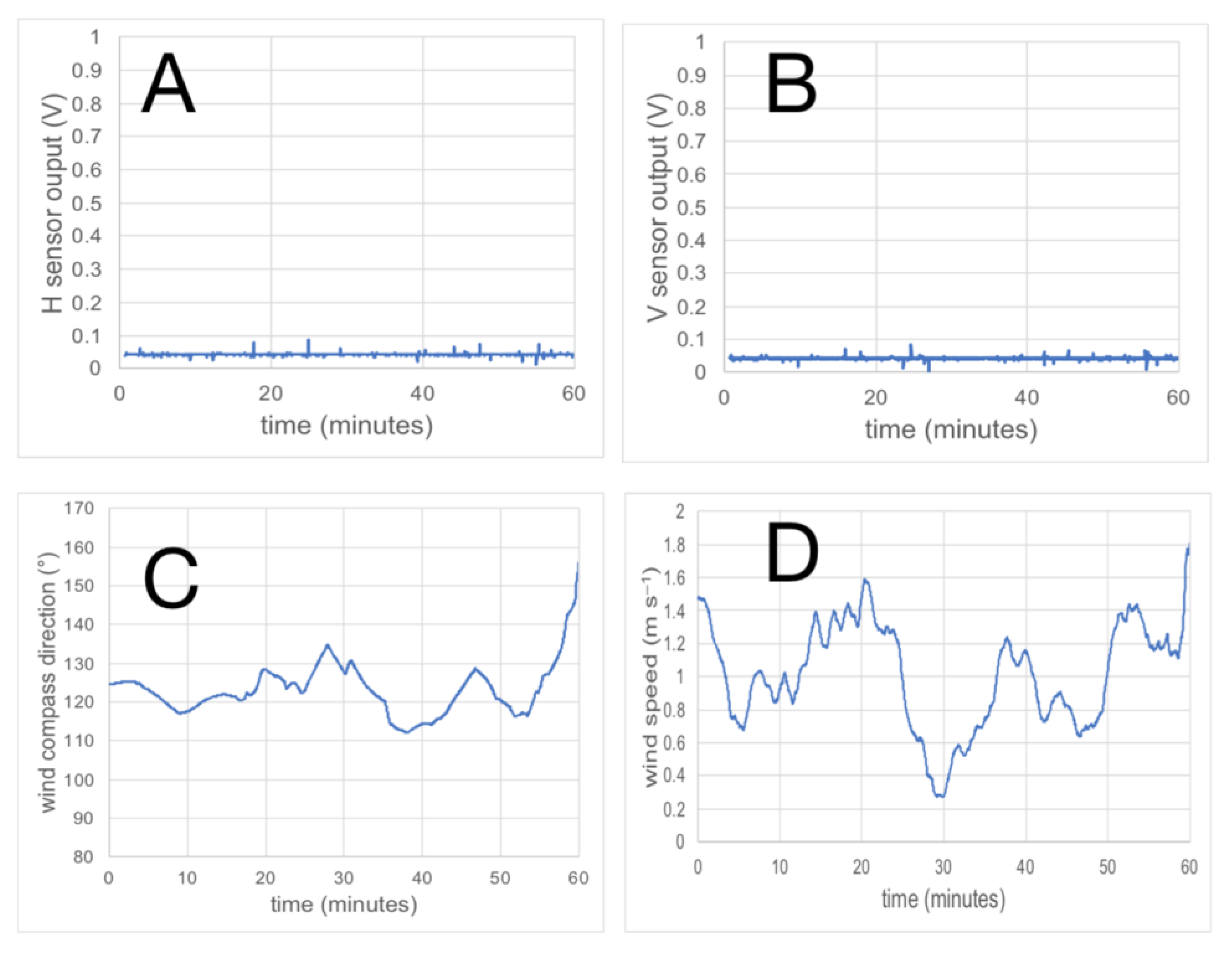

4.1. Noise Levels in The absence of Rain But Under Windy Conditions

In order to assess the level of noise that might be generated by the rotation of the wind vane carrying the vertical acoustic sensor, data from both acoustic sensors were collected during windy but rainless conditions. Statistical results are presented in

Table 1.

The wind speed showed a mean of 1.0 m s

–1 and a maximum of 1.8 m s

–1. Wind direction averaged ~ 123° (magnetic compass direction) but swung more than 55° to the south and more than 35° to the north, through a range of more than 90° (

Table 1). There was thus considerable rotation of the vertical acoustic sensor on its bearings. The data are presented graphically in

Figure 3.

The data for this hour of data show that acoustic noise levels in both sensors are closely comparable, averaging just ~ 0.04 V, with a maximum of ~ 0.08 V. These values are small in relation to the full sensor range of 5.0 V, and to the signal ranges in the 1 August 2025 data of 2.71 V (horizontal sensor) and 0.65 V (vertical sensor) or the 13 August 2025 data of 0.69 V (horizontal sensor) and 0.91 V (vertical sensor).

Importantly, the small signal voltages recorded include not only bearing noise as the wind vane rotated, but also any noise created by wind turbulence around the acoustic sensors themselves, and other nearby sources of noise, including bird vocalisations in the nearby rainforest. Thus, given the very small signal resulting from these combined influences, calculated rain inclinations can be considered to be essentially immune from external influences, at least under the conditions of the field site used here, and can be accepted as reflecting the rain inclination.

4.2. Sample Rain Inclination Data from Continuous Field Monitoring

Data gathered on two days of contrasting weather conditions are presented here to illustrate the kinds of data that can be derived from the new acoustic device. Summary statistical data for both days are set out in

Table 2.

4.3. Rain Inclination and Related Data from 13 August 2025

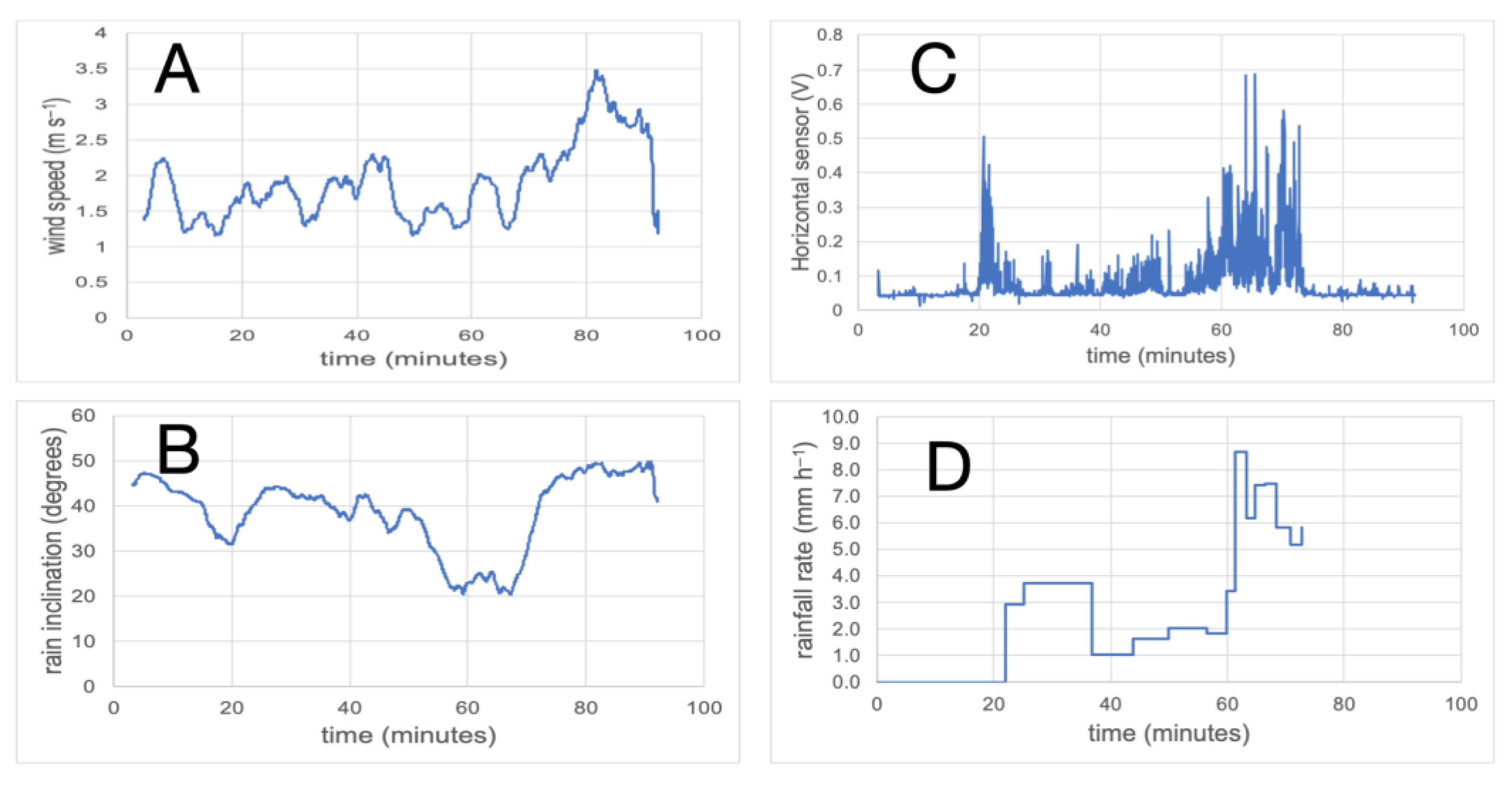

The data from this date include the period 11:40 to 13:13 local time, an interval of ~ 90 minutes (

Figure 4). For most of this period, the wind speed was in the range 1.5–2.5 m s

-1, but peaked at about 3.5 m s

-1 late in the period. Rainfall was essentially continuous from about 20 minutes to 75 minutes after the commencement of recording. There were two principal intervals of relatively heavy rain, from about 20–27 minutes elapsed time, the first reaching ~ 4 mm h

-1 and the second, more intense period reaching almost 9 mm h

-1. These two periods were separated by light rain of 1– 2 mm h

-1.

Figure 4.

Data collected on 13 August 2025 through a duration of 90 minutes. A: wind speed in m s-1. B: rain inclination in degrees from vertical. C: raw voltage output signal from the horizontal acoustic sensor. D: rainfall rate derived from the tipping-bucket rain gauge. There were no tip events logged after ~ 72 minutes. All times are expressed as minutes after the commencement of data logging at 11:40 local time. The data in panels A and B are 5-minute moving averages of the raw 2 sec data.

Figure 4.

Data collected on 13 August 2025 through a duration of 90 minutes. A: wind speed in m s-1. B: rain inclination in degrees from vertical. C: raw voltage output signal from the horizontal acoustic sensor. D: rainfall rate derived from the tipping-bucket rain gauge. There were no tip events logged after ~ 72 minutes. All times are expressed as minutes after the commencement of data logging at 11:40 local time. The data in panels A and B are 5-minute moving averages of the raw 2 sec data.

Rain inclinations were greatest, reaching almost 50°, in the intervals of very light rain prior to 20 minutes elapsed time, and after ~ 75 min elapsed time, when no further tip events were logged by the rain gauge. The raw data from the horizontal acoustic sensor however, having much higher temporal resolution, nevertheless confirm that there was light rain in both periods, and continuing until the end of data collection. Rain inclination declined to ~ 30° in the first period of rain, and declined further to ~ 20° in the second, more intense period of rain. The periods of reduced inclination are clearly synchronous with the periods of more intense rain, as confirmed by both the rain gauge and the acoustic sensor data. Whilst there is a clear relationship between rainfall rate and inclination, there is little evident influence of wind speed on the rain inclination.

5. Discussion

Both periods of rain inclination data presented here show notable fluctuations in rain inclination, falling between about 5° and 22° on 1 August 2025 (average 10.5°), when winds were light (average 0.17 m s

-1), and between 20° and 50° on 13 August (average 38.7°, when wind speeds were considerably higher (average 1.9 m s

-1). The mean wind speed on 13 August averaged more than an order-of-magnitude faster than on 1 August. Thus, a possible relationship between wind speed and rain inclination is suggested by the results. However, on both days, the major fluctuations in rain inclination seem to be strongly linked to fluctuations in rainfall rate, heavier rainfall showing smaller inclinations, and lighter rainfall showing higher inclinations. This can be interpreted in terms of the drop sizes to be expected in rain of different intensities. Heavier rain is associated with a larger median drop size, with higher fall speed, and light rain with a smaller median drop size having a smaller fall speed (Marshall and Palmer 1948) [

82]. Therefore, consistent with equation [

3], larger drops can be anticipated to exhibit a lower inclination than smaller drops, for any given wind speed. Thus, in the absence of wide variations in wind speed, rainfall rate has the capacity to dominate the variation in rain inclination.

As deployed during the field trials just reported, the inclination was logged at 2 s intervals (1800 data points per hour). These data constitute the first virtually continuously collected data able to quantify the variation of rain inclination during a rainfall event minute-by-minute. Interestingly, the typical rain inclinations measured, ranging from 10° to > 50° from the vertical, are comparable to the single value reported by Herwitz and Slye (1992) [

13] of 51.6° from vertical on a single day for which rainfall and wind run data were available, at a field site only about 30 km from the location used in the present study. That site also experiences trade-wind showers driven by strong winds dominantly from the south-east.

The rain inclinations measured acoustically must reflect at least two factors: the wind speed responsible for deflecting drops from the vertical still-air trajectory (and the speed with which they strike the acoustic sensors), and the changing drop size associated with fluctuations in the rainfall intensity from moment-to-moment. It can be hypothesised that the same rain inclination might then result either under intense rain with high wind speeds (capable of deflecting large drops), or light rain with lower wind speeds (sufficient to deflect smaller drops). Depending on the nature and strength of the co-variation of wind speed and rainfall drop sizes, the influence of these factors may tend to reduce the dependence of rain inclination on wind speed. There may be instances of heavy rain with low wind speeds, for instance, or the reverse. This is a subject that requires further study. It is important to remember that with the present acoustic method, it is the ratio of the horizontal and vertical acoustic sensor voltages, and not the absolute values of the voltages, from which the inclination is calculated. Therefore, even though on different occasions there might be high winds speeds in heavy rain (with large median drop size) or lighter winds and less intense rain (with smaller median drop size), the inclination might be similar in both circumstances, despite larger or smaller absolute sensor voltages.

An unresolved question is just how the sensors respond to the impact of drops of varying size. Future research will explore this. It seems reasonable to hypothesise that the sound produced by droplet impact might be mostly attributable to the larger drops. Indeed, the inclination would be expected to differ for different drop sizes during WDR, given the interaction of droplet fall speed and wind speed. Greatest sensitivity to the larger sizes would probably be appropriate for application of the inclination data in studies of splash dislodgment of soil particles and related studies, since these droplets would deliver a large impact energy to the soil surface.

Rainfall depth data collected with a conventional meteorological rain gauge will lead to under-estimated rainfall depth and intensity when rain arrives obliquely to sloping ground. As explained above, this arises because the notional area of the rain gauge collecting funnel cannot be correctly applied to oblique rainfall. A smaller effective collecting area would need to be used. Both depth and intensity errors can be corrected if the rain inclination and azimuth is known, but not without such information. For plot-scale experimental work on infiltration, runoff, nutrient loss, soil erosion, or related processes, an under-estimate of the intensity can be particularly important, as short-lived peaks in intensity are known to be key drivers of surface processes (Dunkerley 2019) [

33]. Significantly, runoff and erosion plots are likely always to be established on slopes rather than flat ground, in order to be able to study overland flow and erosion. It is in research of this kind that the proposed acoustic system may prove helpful.

Under oblique rain on level ground, the effective rain gauge collecting area declines in comparison with the vertically-projected collecting area according to the cosine of the rain inclination. Therefore, in order to record hydrologically-effective rainfall requires either a gauge tilted so as to be orthogonal to the ground surface (Sharon 1980) [

15], or data on rain inclination, with which the rainfall data could be corrected.

There remain several limitations of the acoustic measurement approach presented here, as well as some opportunities for further refinement. Very light drizzle, containing only small drop sizes, is difficult to measure owing to the small impact sounds produced at the acoustic sensors. Furthermore, under those conditions, any extraneous noise such as vehicle or other anthropogenic noise sources, or nearby bird vocalisations, may make the acoustic signal that is sought more difficult to isolate.

A further issue yet to be investigated is the importance of the area of the acoustic sensors that faces the oblique rain. The area of the devices tested here was 314 cm2, approximately the same as that of a standard rain gauge funnel, but both larger and smaller devices could readily be made.

For long-term deployment under harsh conditions, possible deterioration of the drum skins may prove to be a limitation. In that case, it might be necessary to find a material resistant to ultra-violet radiation, as well as to progressive deterioration from the effects of prolonged wetness.

Further developments of the device are also possible. Switch-selectable amplifier gain could be added, such that gain could be increased in areas dominated by light rain, and reduced in areas dominated by heavy rain, as required to avoid clipping in the circuitry. This would arise when the voltage output approached the supply voltage (5 volts in the present case). It would also be straightforward to add a small 3-axis accelerometer chip to the wind vane of the vertical acoustic sensor, in order to log the compass direction toward which the sensor was pointing. This would effectively make the device a complete digital vectopluviometer, and would remove the need for a separate wind direction sensor. Given that ongoing secular change in climate is likely to also involve changes to wind speeds (Snaiki and Wu 2020, [

83] Pakkala and Lahdensivu 2023 [

84], Pu et al. 2023 [

85]) and hence to WDR, better devices for field measurement may be helpful in detecting and quantifying such secular changes.

Finally, it is worth noting that an acoustic sensor can be regarded as a rainfall sensor in the manner described by Dunkerley (2020) [

68]. The voltage signal from the horizontal acoustic sensor could be calibrated using intensity data from a nearby rain gauge. In addition, the acoustic sensors indicate clearly when rain begins and ends, and their voltage output can therefore be used to estimate true rainfall durations, as well as to detect true intermittency in rainfall. These events are hard to detect with precision using conventional rain gauges such as tipping-bucket gauges, owing to their finite bucket filling times.