Introduction

Adolescents who exhibit both obsessive-compulsive symptoms and fluctuating mood remain difficult to treat, especially when selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) threaten to provoke manic or mixed states in youngsters with latent bipolarity [

1,

2]. Intravenous ketamine can relieve depression, OCD, and bipolar depression within hours [

3,

4], but its dissociative effects, cost, and need for monitored infusions restrict routine use in this age-group. A growing body of work therefore explores oral combinations that reproduce ketamine's shift from NMDA- to AMPA-dominated glutamatergic signaling [

5].

We report a 17-year-old male who had childhood ADHD, longstanding checking rituals, persistent family stress, and, while studying overseas, developed ruminative anxiety, mood lability, and passive suicidal thoughts. Low-dose risperidone plus Deanxit produced little change. A modified "Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen" was then started: dextromethorphan (NMDA antagonist) potentiated with fluoxetine 10 mg nightly to inhibit CYP2D6, together with piracetam as an AMPA positive allosteric modulator. After titration to twice-daily, and later an afternoon "as-needed" dose, the patient showed rapid and sustained improvement in mood, intrusive ruminations, and daily functioning. This case offers real-world evidence that a fully oral NMDA–AMPA strategy may stabilise mixed affective-obsessive presentations in adolescents while avoiding high serotonergic exposure.

Methods

This report details the ordinary outpatient management of one adolescent followed at Cheung Ngo Medical Limited, Hong Kong SAR, from December 2024 to December 2025. Care began with a face-to-face assessment in Hong Kong and continued via encrypted video link while the patient was attending high school in Canada.

The patient and his mother (legal guardian) provided written consent for anonymous publication of all clinical information, serial rating-scale results and medication adjustments. The treatment plan reflected routine, individualised practice; no investigational procedures were introduced.

At every contact—office or remote—the patient completed two self-report measures: the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to track depressive symptoms and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) to gauge anxiety. The clinician supplemented these scores with an unstructured psychiatric interview, a mental-state examination, collateral input from the patient's mother, and a review of interim updates sent through secure messaging. Each encounter included specific questions about mood swings, suicidal thinking, obsessive–compulsive phenomena (particularly checking rituals and feelings of incompleteness), sleep pattern and possible medication side-effects.

Drug changes were made solely on the basis of observed benefit and tolerability. All prescriptions were filled at the clinic and shipped to Canada as necessary. Because no conventional mood stabiliser was used at therapeutic doses, routine laboratory surveillance (full blood count, hepatic and renal panels, serum valproate, lithium, etc.) was not required, and neither dextromethorphan/dextrorphan plasma concentrations nor CYP2D6 genotyping were obtained.

After the final review on 9 December 2025, the author extracted data for this case retrospectively from the electronic medical record, contemporaneous clinical notes and the secure-message archive.

Case Presentation

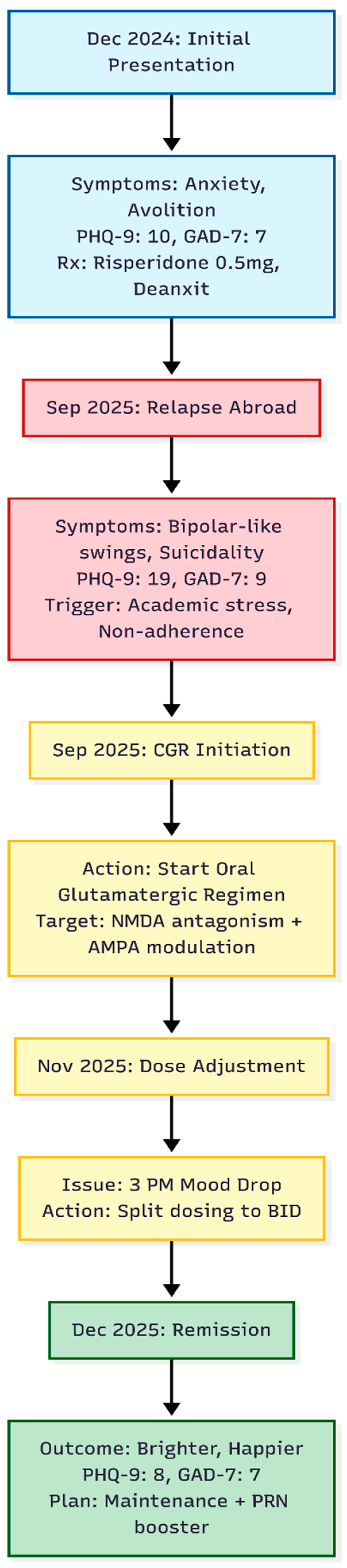

A 17-year-old male, enrolled in high school in Canada, was first seen in our Hong Kong outpatient service while visiting home in December 2024 (

Figure 1). His past history included mild attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, diagnosed and treated in the public sector during primary school, and obsessive-compulsive behaviours—chiefly repetitive packing and checking—first noted in Primary 5. Childhood bullying and longstanding parental conflict were also reported.

Initial Visit – December 2024

Over the preceding winter he had developed a return of anxiety characterised by alternating spells of avolition and intense rumination or, at times, a "blank mind." Ruminative loops centred on counterfactual thoughts about past decisions. Additional stress arose from his mother's recent cancer surgery. On assessment his Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) score was 10 and Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) score was 7. Low-dose risperidone 0.5 mg nightly and Deanxit (flupentixol/melitracen) were started to target ruminative anxiety.

Relapse While Abroad – September 2025

In mid-September 2025 the patient's mother contacted the clinic from Canada, describing pronounced mood swings—"bipolar-like" shifts between days of irritability and days of profound avolition. During a video consultation on 20 September he confirmed two months of deterioration, intrusive suicidal thoughts without plan, and anxiety regarding university promotion. He admitted poor adherence to the December regimen. Scores had risen to PHQ-9 = 19 and GAD-7 = 9.

Introduction of an Oral Glutamatergic Regimen

Because symptoms were resistant and prominently ruminative, a modified glutamatergic stack was prescribed and couriered to Canada:

Dextromethorphan 30 mg (two 15 mg tablets) nightly

Piracetam 600 mg (half a 1200 mg tablet) nightly

Fluoxetine 10 mg nightly, selected to inhibit CYP2D6 and prolong dextromethorphan exposure

Follow-Up - November 2025

By early November the patient felt generally better but experienced a predictable "mood drop" and uneasiness at about 15:00 each day. The schedule was therefore changed: dextromethorphan and piracetam were given twice daily (morning and night), while fluoxetine remained once daily at night.

Follow-Up – December 2025

At an in-person review on 9 December 2025 he appeared brighter and described himself as "better" and "happier," denying current low mood. Ratings had fallen to PHQ-9 = 8 and GAD-7 = 7. A residual sensation that "something is undone" still surfaced around 15:00. An additional as-needed afternoon dose of dextromethorphan and piracetam was supplied, leaving the twice-daily baseline intact. Fluoxetine 10mg, Risperidone 0.5mg and Deanxit was continued nightly.

Discussion

The favourable course following dextromethorphan–piracetam, supported only by minimal fluoxetine, is striking for three reasons.

First, remission occurred without conventional mood stabilisers. Apart from risperidone 0.5 mg nocte—an anxiolytic dose rather than an antimanic one [

6]—agents such as lithium, valproate, lamotrigine, or higher-dose atypical antipsychotics were never introduced. Yet the severe "bipolar-like" swings and suicidal ideation that had emerged abroad subsided within weeks and did not recur during ongoing academic pressure or long-haul travel. Experimental work shows that sustained NMDA antagonism followed by AMPA enhancement restores prefrontal–limbic synaptic density through BDNF–mTOR pathways, thereby normalising mood regulation [

7,

8,

9]. Our observations support the notion that ketamine-class plasticity induction can confer mood-stabilising effects independent of traditional GABA- or dopamine-directed drugs [

5].

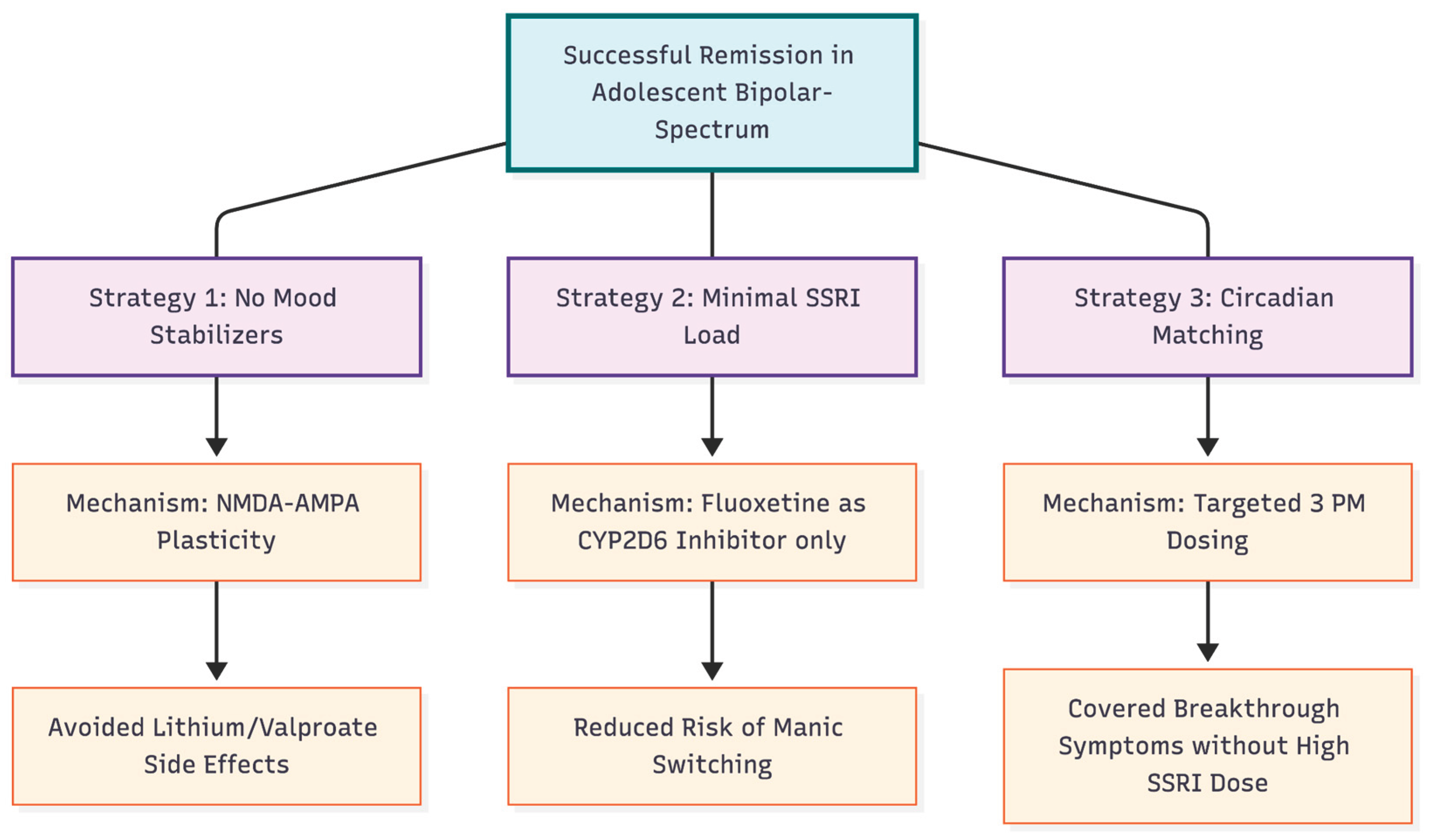

Figure 2.

Therapeutic Rationale and Advantages. The figure outlines the three pillars of the successful treatment strategy. 1. Reliance on glutamatergic plasticity rather than traditional mood stabilizers avoided heavy sedation. 2. Using Fluoxetine strictly as a metabolic inhibitor rather than a primary antidepressant minimized the risk of inducing mania. 3. Flexible dosing matched the patient's specific diurnal symptom pattern.

Figure 2.

Therapeutic Rationale and Advantages. The figure outlines the three pillars of the successful treatment strategy. 1. Reliance on glutamatergic plasticity rather than traditional mood stabilizers avoided heavy sedation. 2. Using Fluoxetine strictly as a metabolic inhibitor rather than a primary antidepressant minimized the risk of inducing mania. 3. Flexible dosing matched the patient's specific diurnal symptom pattern.

Second, we were able to maintain a minimal dose of fluoxetine (10mg) once glutamatergic doses were optimised. Fluoxetine had been included solely to extend dextromethorphan exposure, mirroring bupropion's role in Auvelity [

10]. When an afternoon slump appeared, we increased only dextromethorphan and piracetam while leaving fluoxetine unchanged. This approach lessened cumulative serotonergic burden, a prudent step given the high risk of antidepressant-induced mood switching in youths with bipolar diathesis [

11,

2]. The patient's continued progress once fluoxetine was minimised suggests that the regimen's therapeutic drive stemmed principally from NMDA–AMPA modulation rather than serotonin re-uptake blockade [

5].

Third, the flexible schedule—morning, evening, and targeted 3 p.m. dosing—matched the diurnal pattern of breakthrough symptoms. Such tailoring may optimise synaptic AMPA/NMDA balance across the waking day while keeping total drug exposure low. Similar adjustments have been described in earlier anecdotal reports of the regimen in adults with schizoaffective disorder or refractory OCD [

12,

13]. The implementation of this strategy, instead of adding a morning dose of fluoxetine, may also help prevent serotonin toxicity [

13].

In summary, this case expands previous adult studies of the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen to a younger demographic [

12,

13,

5]. The ability to quickly control mood and anxiety without using standard mood stabilizers, as well as the successful reduction of SSRI load, highlights the potential of targeted glutamatergic polypharmacy for complex adolescent cases.

Funding Declaration

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Declaration

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding Statement

None declared.

References

- Amerio A, Stubbs B, Odone A, et al. The prevalence and predictors of comorbid bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2015;186:99–109.

- De Prisco M, Tapoi C, Oliva V, et al. Clinical features in co-occuring obsessive-compulsive disorder and bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2024;80:14–24. [CrossRef]

- Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biological Psychiatry 2000;47(4):351–354. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. Randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Proof-of-concept. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013;38(12):2475–2483. [CrossRef]

- Cheung N. DXM, CYP2D6-inhibiting antidepressants, piracetam, and glutamine: Proposing a ketamine-class antidepressant regimen with existing drugs. Preprints.org 2025. [CrossRef]

- Li N, Lee B, Liu RJ, et al. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science 2010;329(5994):959–964. [CrossRef]

- Maeng S, Zarate CA Jr, Du J, et al. Cellular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of ketamine: Role of AMPA receptors. Biological Psychiatry 2008;63(4):349–352.

- Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, et al. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature 2016;533(7604):481–486. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy B, Bunn H, Santalucia M, et al. Dextromethorphan-bupropion (Auvelity) for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience 2023;21(4):609–616. [CrossRef]

- Amerio A, Costanza A, Aguglia A. Differentiating comorbid bipolar disorder and OCD. Psychiatric Times 2020. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/differentiating-comorbid-bipolar-disorder-and-ocd.

- Cheung N. An oral "ketamine-like" NMDA/AMPA modulation stack restores cognitive capacity in a young man with schizoaffective disorder—Case report. Preprints.org 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cheung N. Case series: Marked improvement in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive symptoms with over-the-counter glutamatergic augmentation in routine clinical practice. Preprints.org 2025. [CrossRef]

- de Filippis R, Aguglia A, Costanza A, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder as an epiphenomenon of comorbid bipolar disorder? An updated systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024;13(5):1230.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).