1. Introduction

Ionizing irradiation in patients who have undergone radiotherapy for head and neck cancer (HNC) compromises tissue vascularization, impairing healing of soft and hard tissues after dental procedures . The mandible is highly sensitive to radiotherapy (RT), due to differences in blood supply and anatomical structure, and osteoradionecrosis (ORN) remains one of the most serious complications of treatment [

1,

2].

The definition of ORN most consistently endorsed in the literature is ‘‘irradiated bone that becomes devitalized and exposed through overlying skin or mucosa without healing for more than three months, without recurrence of cancer” [

2]. Its incidence ranges from 5% to 15% across studies, and there is still considerable controversy regarding the management of mandibular dentition before radiotherapy [

3,

4].

In most cases, ORN is associated with soft-tissue necrosis, followed by bone exposure. Teeth that cannot be restored due to caries, periodontal disease, or root lesions may lead to bone infection and contribute to the development of ORN, as irradiated tissues have reduced vascularization and impaired repair capacity [

5,

6].

Patients who receive radiotherapy are at high risk of poor bone healing after surgical interventions [

7]. The same applies to those treated with intravenous bisphosphonates—drugs commonly prescribed for bone disorders characterized by increased bone resorption, such as Paget’s disease, osteoporosis, hypercalcemia, multiple myeloma, and bone metastases. As tissue damage—both soft and hard—depends on the intensity of surgical trauma, preventive strategies for irradiated patients prioritize specific management protocols [

7]. These include the prior removal of any potential sources of infection in patients scheduled to undergo head and neck cancer radiotherapy, aiming to ensure adequate oral health and reduce the risk of ORN associated with oral trauma or subsequent surgical procedures. For teeth severely compromised following radiotherapy, the literature indicates that postponing extractions for 9 to 12 months after completing irradiation may lower the associated risk. Although post-extraction socket healing has been widely documented in the literature, standardized procedures for comparing healing under different conditions—such as after RT in the head and neck region—remain scarce [

2,

7].

Identifying treatment strategies that enhance mucosal repair and simultaneously reduce surgical trauma remains a critical priority, especially in patients who have received high doses (65 to 80 Gy) [

1] of RT, given that adverse effects appear to increase with dose, or in those who cannot delay tooth extraction. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is an autologous blood product obtained by centrifuging whole blood to isolate a platelet-rich fraction. Platelets contain growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and matrix glycoproteins (such as thrombospondin-1) during at least 7 days in vitro [

8,

9]. PRP has been widely promoted to enhance the survival of bone grafts in dental implantology, aesthetic surgery, and orthopedic procedures. It has been hypothesized that PRP could help to counteract the damage caused by RT to the affected soft tissues, improving mucosal healing and preventing post-extraction bone exposure. Improved mucosal healing with accelerated alveolar closure could, subsequently, act as a barrier against potential bone exposure, which in irradiated patients may worsen over time and progress to ORN. [

7,

10,

11].

Despite the strong theoretical rationale for its efficacy, the use of PRP remains controversial, as most published studies are case series or unblinded trials. Systematic reviews have not demonstrated a consistent benefit of PRP in sinus bone grafting, facelift surgery, or fracture healing [

3].

In the available literature, many studies [

3,

10,

12,

13] evaluate the effects of a specific type of autologous plasma concentrate (APC), such as plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF), PRP, and leukocyte-rich fibrin (L-PRP), individually. However, there is no record of a systematic review that includes all APC, which justifies the present study.

Therefore, the objective of this systematic review is to assess the effectiveness of APCs as biotechnological adjuncts for enhancing post-extraction alveolar healing in patients who have undergone head and neck RT.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 guidelines [

14,

15]. A detailed protocol was designed before the start of this study and registered on PROSPERO (CRD420251151452). Access link:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251151452).

2.1. PICO Question

The main research question of this systematic review was developed using the PICO framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes), as recommended in evidence-based practice.

Population: Adult patients (≥18 years) requiring tooth extraction who are currently receiving or have previously received radiotherapy for head and neck cancer.

Intervention: Application of an autologous platelet concentrate (e.g., PRGF, PRP, L-PRP) placed in the extraction site immediately following tooth removal.

Comparison: Either placement of a placebo in the extraction socket or allowing natural healing through maintenance of the blood clot alone.

Outcome of interest: Post-extraction tissue repair including reduced healing time, decreased risk of osteoradionecrosis (ORN), and improved soft-tissue quality.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria for the studies: Controlled clinical trials, randomized clinical trials (RCT), cohort studies, and case series/reports involving adult HNC patients treated with RT and undergoing tooth extraction with APC application. [

3,

10,

12,

13].

Exclusion criteria: Narrative or systematic reviews were excluded to avoid duplicate data, while in vitro and animal studies were excluded because they do not reflect clinical outcomes in humans. Studies that did not report post-extraction outcomes were excluded, as they did not provide relevant data. Articles not published in English were excluded due to translation limitations and to ensure consistency in study selection.

2.3. Outcome Measures

Outcome measures included indicators of improved tissue repair after tooth extraction, such as postoperative pain, the incidence and timing of ORN, mucosal healing quality, bone exposure, and postsurgical complications.

2.4. Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted in MEDLINE (via PubMed), Scopus, and the Cochrane CENTRAL database for English-language articles published between January 2010 and June 2025. The search strategy incorporated MeSH terms, keywords, and additional free-text terms, combined using Boolean operators (OR, AND). Tailored search strategies were created for each database, following the structure of the MEDLINE search, which began with: “(socket) AND (radiotherapy OR cancer) AND (platelet-rich plasma OR prp OR platelet-rich fibrin OR prf OR leukocyte and platelet-rich fibrin OR lprf OR l-prf OR advanced platelet-rich fibrin OR injectable platelet-rich fibrin OR iprf OR growth factors)”.

Additional unpublished studies were sought on the OpenGrey database, and reference lists of included articles were manually screened for further eligible studies.

2.5. Assessment of Validity and Data Extraction

Two reviewers (J.D-R. and A.T-M.) independently performed study identification, screening, and eligibility assessment. Data extraction was also carried out in duplicate by the same reviewers. In cases of disagreement, consensus was reached through discussion; if necessary, a third investigator was available for arbitration (J.L-L).

Extracted data included study design, patient characteristics, intervention details, outcomes, and follow-up.

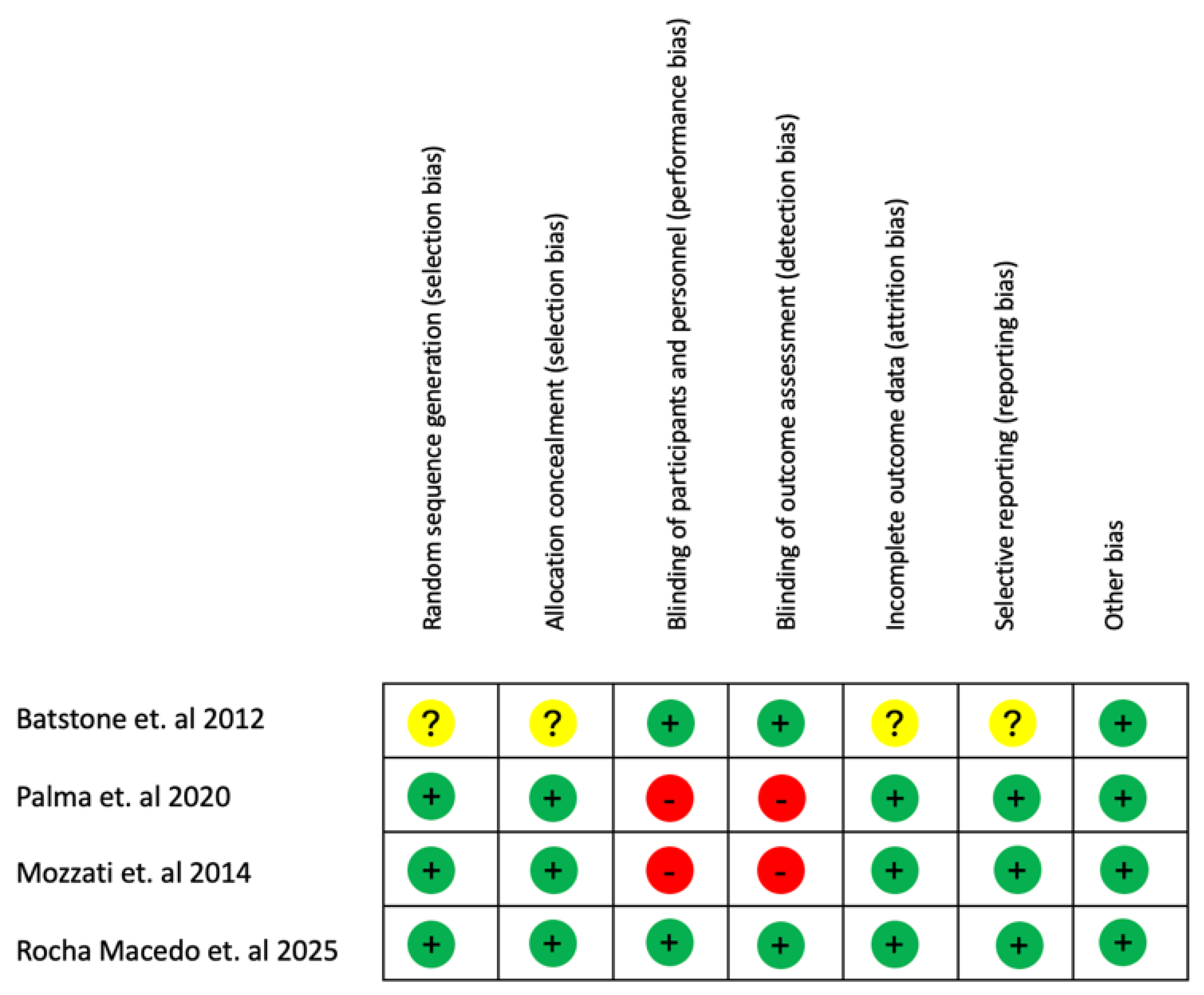

2.6. Quality Assessment and Assessment of the Risk of Bias in Included Studies

The risk of bias of each randomized clinical trial included in the review was assessed (J.D.R.) using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (17). Each domain was rated as low (+), high (−), or unclear (?). The evaluation included the following criteria: (1) adequacy of the randomization sequence; (2) concealment of allocation; (3) blinding of participants and personnel; (4) blinding of outcome assessors; (5) completeness of outcome data; (6) selective reporting; and (7) any additional potential sources of bias. Based on these evaluations, studies were categorized as having low, high, or unclear risk of bias. A low risk of bias was assigned when all domains were rated as low, indicating that bias was unlikely to significantly influence the results. A high risk of bias was assigned when one or more domains were judged as high, suggesting that the identified bias could undermine confidence in the findings. An unclear risk of bias was considered when one or more domains were classified as unclear, raising uncertainty regarding the reliability of the outcomes. In addition, all non-randomized controlled clinical trials were automatically regarded as presenting a higher risk of bias due to their intrinsic methodological limitations.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The synthesis of results used descriptive statistics to summarize the main findings of each study. Comparative effect measures, including odds ratio (OR) and relative risk (RR), were calculated when applicable to evaluate differences between the intervention (APC) and control groups.

3. Results

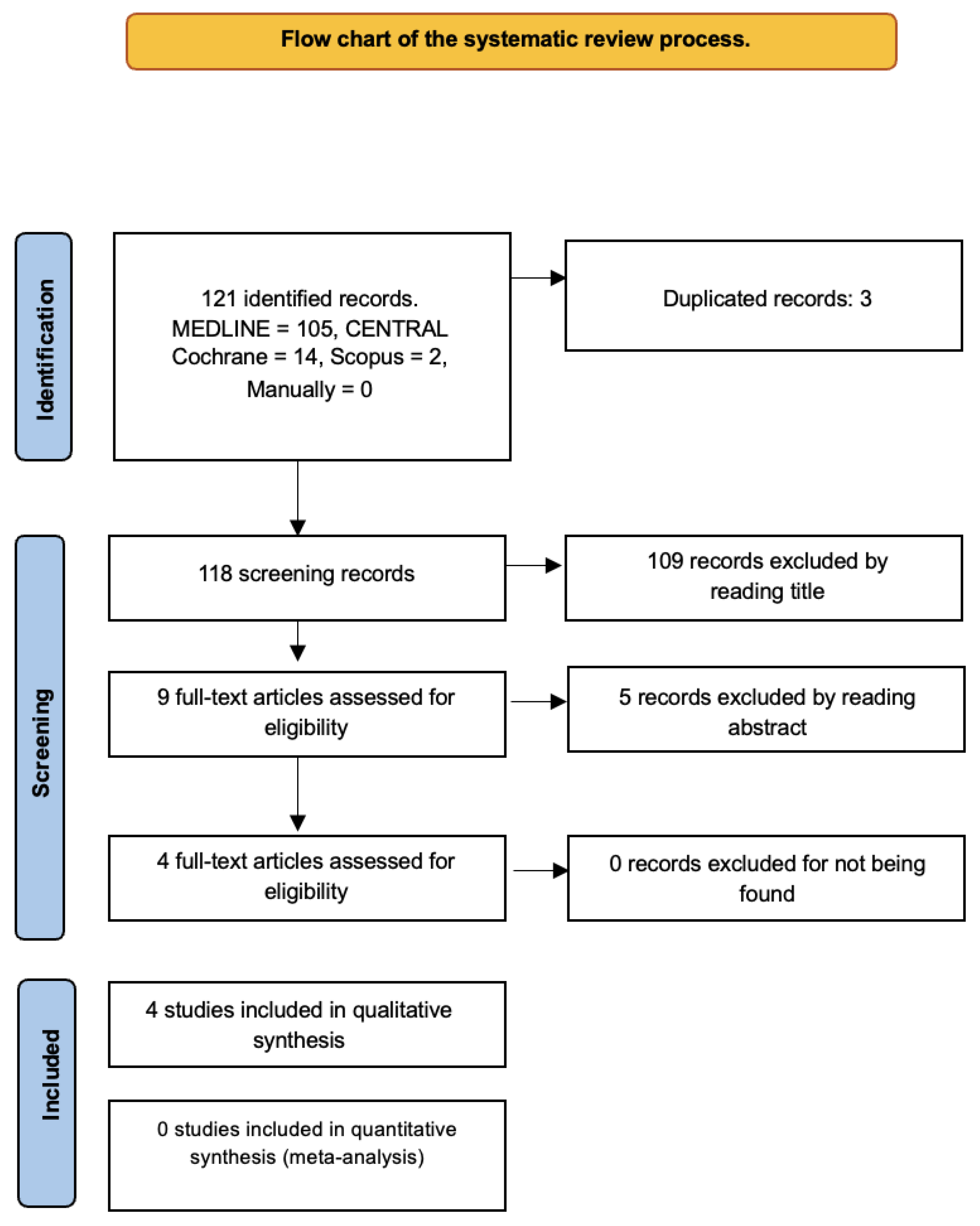

The search yielded 121 records. After excluding duplicates and considering titles and abstracts, only four studies [

3,

10,

12,

13] initially met the criteria for this systematic review (

Figure 1).

3.1. Study Characteristics

Of the included studies, 95 patients were involved: 75 male (78.95%) and 20 female (21.05%), and 315 tooth extractions were performed. Among them, 157 sockets (49.84%) received a platelet concentrate, while 158 (50.16%) healed naturally without adjunctive material. The effect of platelet concentrate application was therefore compared to natural healing without any external aid. The mean follow-up period across studies was 23.5 months. The reviewed periods were up to 12 months. Data extracted from each included study are summarized in

Table 1

3.2. Included Studies

In total, four randomized clinical trials were selected for the qualitative synthesis, as no other studies meeting our inclusion criteria (controlled trials, cohort studies, or case series/reports) were identified. These included: an Australian double-blind split-mouth trial using PRP [

3], which reported a 5-year follow-up following 44 mandibular extractions in 22 patients. In addition, a Brazilian parallel-group study using L-PRF [

13] reported a 180-day follow-up after 23 mandibular or maxillary extractions in 23 patients. Another study, which included PRGF [

10], was performed in Torino, Italy, as a prospective split-mouth study with a follow-up of 1 to 24 months after 114 mandibular or maxillary extractions in 20 patients. Finally, a Brazilian double-blind randomized clinical trial used A-PRF (advanced platelet-rich fibrin) [

12] and reported a 4-month follow-up after 134 mandibular and maxillary extractions in 30 patients (

Table 1).

3.3. Risk of Bias in the Included Trials

Concerning the risk of bias of the included studies, one study was identified as “not clear or medium risk” [

3], two of them [

10,

13] as “high risk”[

10], and another study was included as “low risk”[

12] (

Figure 2).

3.4. Individual Outcomes of Studies: Pain

Across all four studies, postoperative pain was consistently low to negligible in both intervention (PRP/PRGF/L-PRF/A-PRF) and control groups. All studies used 0–10 scales (VAS or Likert) to assess postoperative pain at various follow-up points. Most patients achieved pain resolution within the first week, with no significant differences between groups at any time point, except for an isolated case [

10] of pain at 30 days in one control patient due to healing failure with bone exposure.

3.5. ORN

Overall, ORN occurred in 3.16% (3/95) of the patients and in 1.27% (4/315) of the extraction sites. There was a 0.63% (1/158) incidence of ORN in the control sites and 1.91% (3/157) in the PRP-treated sites.

3.6. Healing Index

Two of the included studies [

10,

12] calculated a healing index (HI) based on different outcome measures. PRGF accelerated early healing and slightly reduced complications, while A-PRF showed no differences from controls, with both groups maintaining excellent healing throughout follow-up.

3.7. Other Outcome Measures

Some variables were measured in only a single study. Bleeding, tissue color, suppuration, consistency, wound closure (WC), and bone exposure were assessed in only one study [

12]. The residual socket volume (RSV) was evaluated in another included study [

10].

The bleeding, tissue color, suppuration, and consistency were assessed using a modified HI for each of the parameters above, with scores ranging from 1 to 3 at each evaluation period, with the final score being the HI (subsequently evaluated), at 7, 14, 30, 60, 90, and 120 days after surgical intervention. The A-PRF and control group reported median values of 1 in each follow-up.

WC, bone exposure, and edema were assessed in the same trial [

12] at 7, 14, 30, 60, 90, and 120 days after surgical intervention. A-PRF and control group frequency data showed that WC was achieved progressively in both groups, reaching 100% by day 90. However, the control group demonstrated significantly greater closure at 7 and 14 days (

p< 0.05). At 7 days, the odds ratio (OR) of WC was 0.42, and the relative risk (RR) of WC was 0.84. The study’s findings, when analyzing WC, showed that the extraction procedure was safe and that A-PRF did not affect the healing process in the short- or medium-term. Bone exposure was minimal in the experimental group (≤3% at 30–60 days) and completely absent in controls. Edema was reported only on day 7, affecting 6% of patients in both groups, and resolved thereafter.

The RSV was assessed in one of the included studies (10) as the ratio of (maximum mesiodistal (MD) x buccolingual (BL) extension x socket depth)x t to the value (MD x BL x socket depth)t = 0 evaluated post-extraction (perfect closure corresponds to RSV = 0.00) assessed during the first three follow-up visits, conducted at 7, 14, and 21 days post-intervention. RSVs were consistently smaller on the PRGF side than on the control side at all follow-up sessions, with statistically significant differences throughout. Despite a progressive reduction of RSVs and an increasing number of sockets achieving closure over time, the PRGF group showed faster healing. By day 7, RSV had reduced to <10% of the initial volume in 15 PRGF sockets, compared with 5 controls (p= 0.03). At day 14, 33% of PRGF sockets and 22% of controls had reached <1% RSV, increasing to 77% and 74%, respectively, by day 21. Complete closure was observed in 15% of PRGF sockets and 12% of controls at day 14, rising to 75% and 70% at day 21.

No sensitivity analyses were performed, as the limited number of included studies did not allow for robustness assessment of the synthesized results. No formal evaluation of the certainty of the evidence (e.g., GRADE) was performed due to the limited number and heterogeneity of the included studies.

4. Discussion

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of APCs (PRP, PRGF, L-PRF, A-PRF) in enhancing post-extraction alveolar healing in patients previously treated with head and neck RT. Although this review focused on post-extraction healing in irradiated patients, evidence from other clinical contexts supports PRF's beneficial role in tissue repair. However, these data do not involve irradiated extraction sockets and cannot be extrapolated. For example, PRF membranes have been shown to improve healing of the Schneiderian membrane in sinus lift procedures, stimulating periosteal-like behavior and potentially increasing or stabilizing bone volume around implants [

18]. This biomaterial appears to accelerate physiologic healing due to its fibrin matrix, polymerized in a tetramolecular structure, which incorporates platelets, leukocytes, cytokines, and circulating stem cells [

19].

Multiple benefits have been reported when platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) is used to fill extraction sockets. Although the number of studies remains limited, PRF is considered an optimal material for post-extraction applications, promoting bone healing and regeneration, preserving the quality and density of the residual alveolar ridge, reducing infection risk, and decreasing surgical time compared to conventional membrane coverage. These advantages are further supported by its low cost and minimal associated complications. PRF may also be applied around immediately placed implants to fill residual gaps or to enhance soft-tissue wound healing. Nonetheless, there is a pressing need for well-designed studies to evaluate dimensional changes associated with PRF use in diverse clinical scenarios [

20,

21,

22,

23].

Overall, our findings indicate that these biotechnological adjuncts may be safe and well tolerated, however the clinical benefits over natural healing appear modest and current evidence remains uncertain. Postoperative pain across all studies was generally minimal and typically resolved within the first week. In the PRP study [

3], mean pain scores were low at all follow-up points (2 weeks to 12 months) and comparable to those of the control group, despite some missing data due to patient dropouts. The L-PRF [

13] and A-PRF [

12] groups also reported minimal pain at early- and mid-term follow-ups, with no significant differences compared to controls, except for a single case of pain at day 30 in one control patient, associated with severe healing failure.

In a separate cohort of 100 irradiated patients with cancers of the oral cavity, oropharynx, and nasopharynx, osteonecrosis developed in 19 of 78 dentulous and in 3 of 22 edentulous patients, most commonly more than one year after treatment. The main predisposing factor was the radiation dose to bone, particularly in the less vascularized mandible. Notably, no cases occurred below 6500 rads, whereas the incidence increased substantially above 7500 rads. Furthermore, the risk of osteonecrosis was significantly higher after RT than before treatment or in patients without extractions [

24]. These observations reinforce the critical role of radiation dose and timing of dental interventions in the pathogenesis of ORN.

Beyond platelet concentrates, other preventive therapies have also been described in the literature to reduce the risk of ORN. Among them, a prospective randomized trial comparing hyperbaric oxygen therapy with systemic antibiotics demonstrated that, in a high-risk population requiring tooth removal in irradiated mandibles, prophylactic hyperbaric oxygen significantly reduced the incidence of ORN to 5.4% compared with 29.9% in the antibiotic group (

p= 0.005) [

25]. Therefore, hyperbaric oxygen should be considered a valuable prophylactic approach when post-irradiation dental procedures involving tissue trauma are indicated.

Post-surgical complications were uncommon and mild. In the study by Palma LF et al. [

13], no cases of edema, alveolitis, suture dehiscence, persistent bleeding, or oronasal communication were observed at day 3 (phone) and day 7 (in-person). Similarly, Mozzati et al.’s investigation [

10] reported high complication-free rates during the first month, with 100% in the PRGF group and 96.5% in controls. Macedo et al. [

12] also found minimal adverse events related to edema, bleeding, tissue color, consistency, or suppuration. Overall, these findings indicate that APCs are safe for use in irradiated patients and do not increase the risk of postoperative complications compared with standard healing.

The HI provides additional support for the role of platelet concentrates in the early postoperative recovery period. PRGF [

10] demonstrated accelerated healing, accompanied by a slight reduction in minor complications compared with controls. Similarly, several studies have reported enhanced soft-tissue healing and early epithelialization with the use of PRF and L-PRF, likely due to their sustained release of growth factors and the stability of their fibrin matrix [

9,

19]. In contrast, A-PRF [

12] showed no significant differences; however, both groups consistently maintained excellent healing outcomes across all follow-up periods. Altogether, these observations suggest that while specific platelet formulations, such as PRGF, may enhance early tissue repair, the overall healing trajectory remains favorable regardless of the adjunctive material used.

Limitations of the included studies include small sample sizes, heterogeneous interventions and outcome measures, and variability in follow-up periods; in one of the trials [

13] only two follow-up assessments were performed for pain and other postoperative complications (day 3 by phone and day 7 in person), with no further in-person evaluations, potentially leading to underreporting of complications and limiting the reliability and generalizability of the findings. In addition, missing information on pain due to patient loss at follow-ups was found [

3].

Furthermore, conducting a meta-analysis was not feasible due to considerable heterogeneity among the included studies in outcome definitions, measurement techniques, and data reporting. Variations in follow-up duration, evaluation criteria, and quantitative data presentation further limited the comparability of results and precluded a meaningful statistical synthesis.

Another potential source of bias in the included studies is the heterogeneity of platelet concentrates used. A comparative investigation [

26] evaluated growth factor release from PRP, PRF, and advanced-PRF (A-PRF), showing that while PRP releases higher levels of growth factors during the initial phases, while PRF and A-PRF ensure a slower, sustained release for as long as 10 days. Notably, A-PRF demonstrated significantly greater cumulative growth factor release than standard PRF, suggesting potential advantages for regenerative applications. These differences in biologic behavior underscore the importance of considering the specific type of platelet concentrate when interpreting clinical outcomes and highlight the need for future studies to evaluate their effects on cell behavior and in vivo healing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D.R., A.T.M. and B.T.C.; Methodology and Software, J.D.R., A.T.M, B.T.C., J.P.M, J.L.L. and S.E.M.; Validation, J.L.L.; Formal Analysis, S.E.M. and J.L.L.; Investigation, J.D.R. and A.T.M.; Resources, Does not apply; Data Curation, J.D.R., A.T.M. and B.T.C.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.D.R., A.T.M., B.T.C. and J.L.L. ; Writing—Review & Editing, J.D.R., A.T.M., B.T.C., J.P.M and J.L.L. ; Visualization, J.D.R., A.T.M., B.T.C. and J.L.L.; Supervision, A.T.M. and J.L.L.; Project Administration, Does not apply; Funding Acquisition, Does not apply. All authors have reviewed and approved the submitted version.