Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

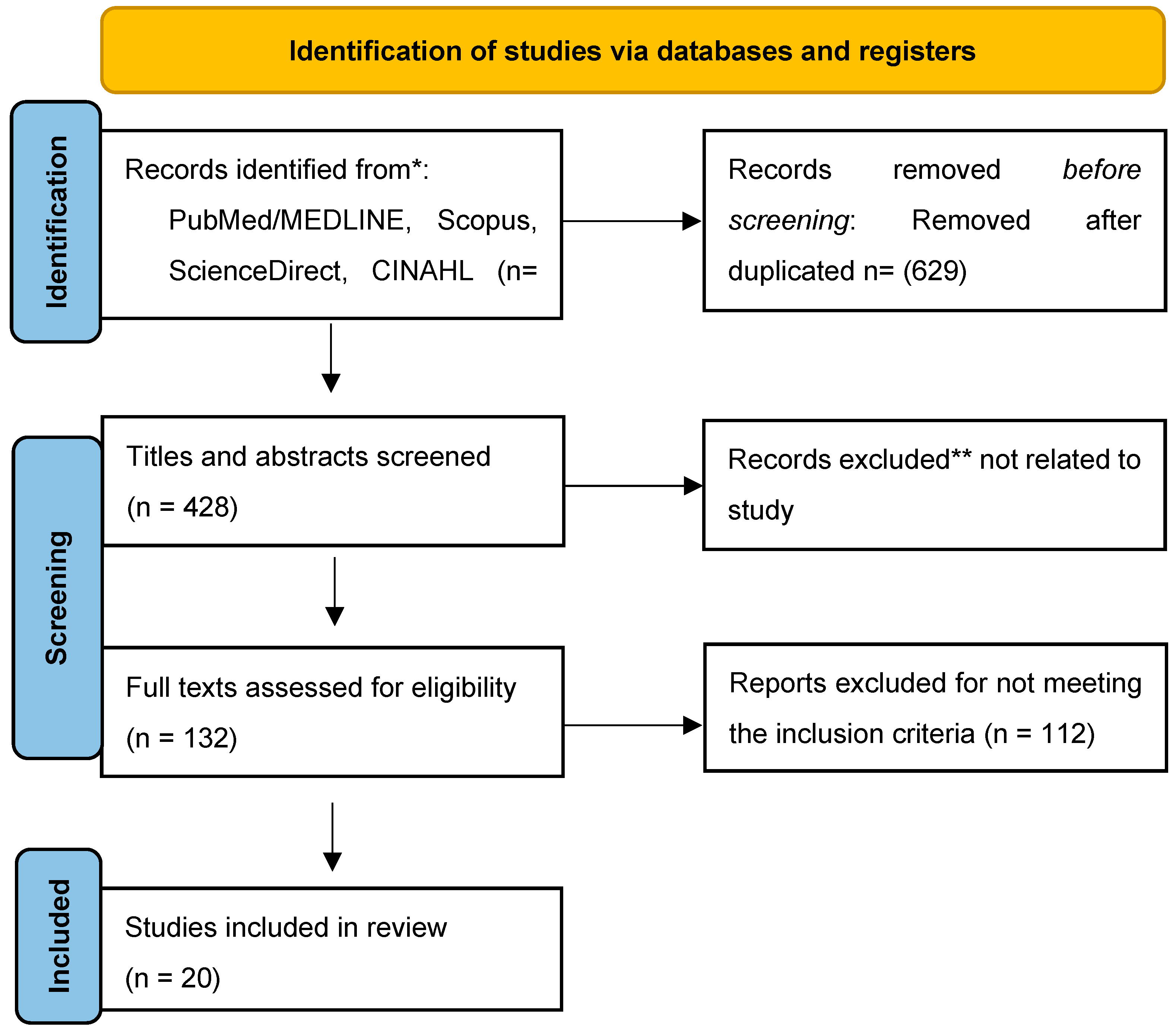

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Quality Assessment and Data Analysis

3. Results

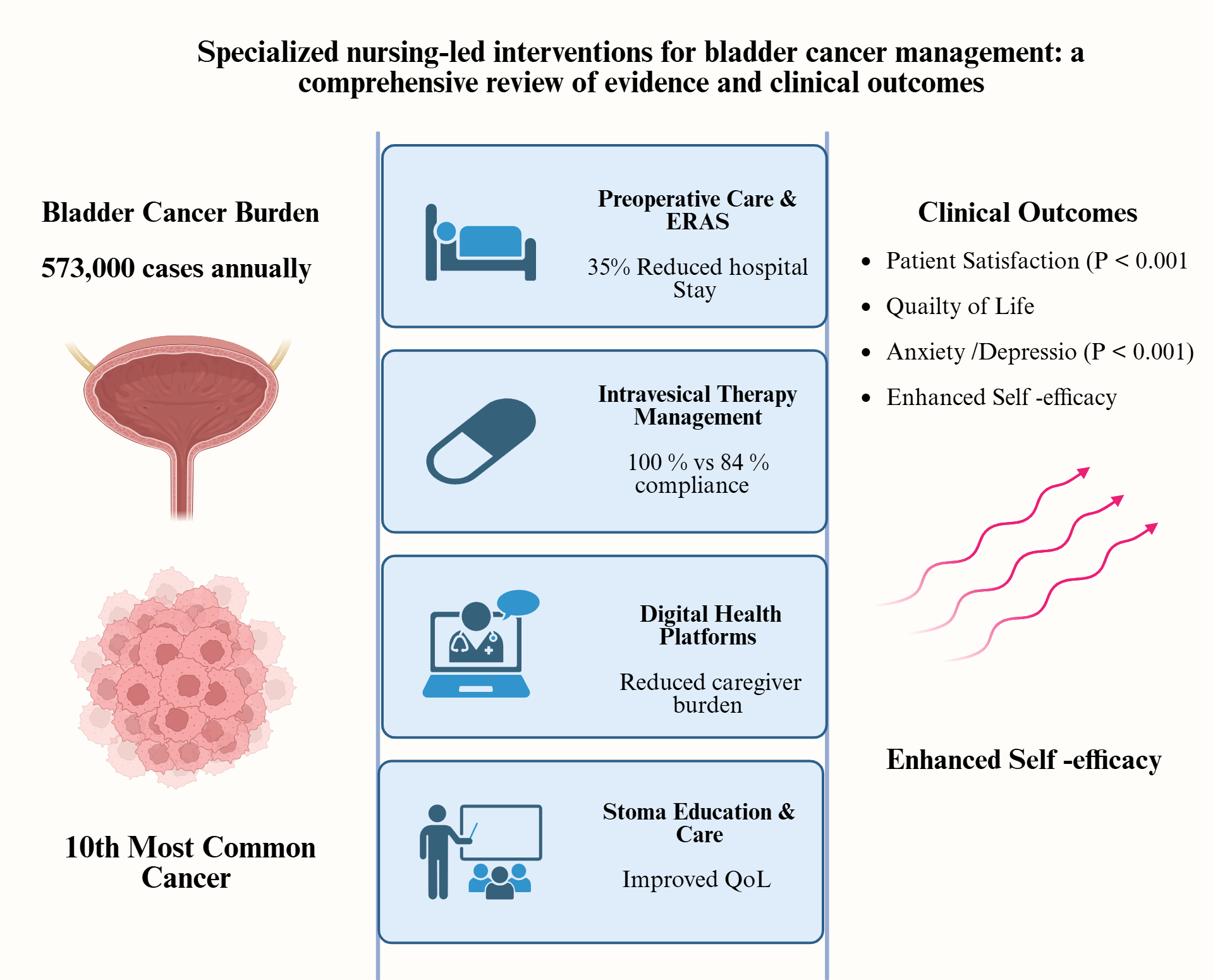

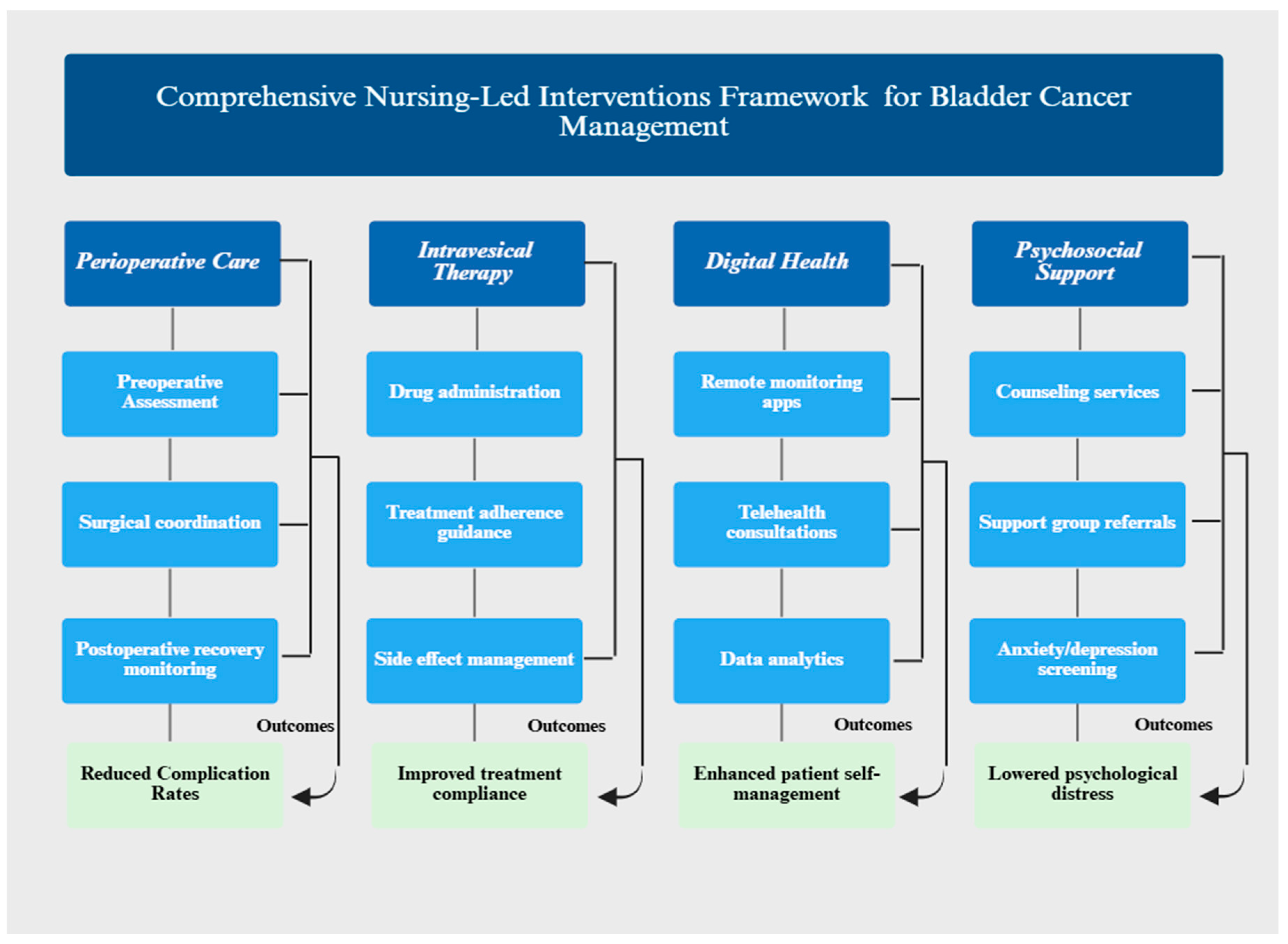

3.1. Perioperative Care and Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Protocols

3.2. Intravesical Therapy Management: Treatment Compliance and Patient Satisfaction

3.3. Digital Health and Telehealth Interventions: Implementation and Outcomes

3.4. Stoma and Ostomy Care Management: Education and Self-Care Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Psychosocial Support and Mental Health Interventions: Addressing Critical Care Gaps (Table 6)

| Authors/years | Study type | Population (N) | Interventions/key findings | Statistical significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bessa (2021) [30] | Systematic review |

BC patients (literature) |

Critical gap identified: BC-specific mental health interventions found | Highlights urgent need for intervention development |

| Grassi (2023) [40] | Clinical practices guidelines |

Adult cancer patients |

Recommended CBT and mindfulness-based interventions; anxiety /depression underrecognized | Guidelines-level evidence; expert consensus |

| Qian (2024)[51] | Comparative study | 80 BC patients | Gratitude nursing program: improve QoL, reduced fear /depression/anxiety | Significant improvement vs routine care (P˂0.05) |

| Peng (2024) [28] | Comparative study | 80 BC patients | People-oriented nursing model: reduced anxiety /depression, improved QoL | Anxiety /depression reduction statistically significant (P˂0.05) |

| Thomas (2024) [44] | Systematic review of 17 studies |

2,572 patients | Risk factors identified (advanced stage, younger age, female sex); social support protective | Meta-analysis of psychological distress outcomes |

4.2. Clinical Outcomes: Quantifiable Benefits

4.3. Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO): Quality of Life and Psychological Benefits

4.4. Caregiver-Related Outcomes: Extended Impact Beyond Patients

4.5. Comparative Effectiveness: Nursing Interventions vs. Standard Care

- Complication rates: 8% (specialized nursing care) vs 38% (standard care); RR=0.41 (95% CI: 0.18-0.93)

- Treatment compliance: 100% (specialized nursing care) vs 84% (standard care); P<0.05

- Hospital length of stay: 11 days (specialized nursing care) vs 17 days (standard care); 35% reduction

- Patient satisfaction: Significantly higher with specialized nursing interventions across all dimensions (P<0.001)

4.6. Nursing Interventions Effectiveness

- Perioperative ERAS protocols: 35% reduction in hospital length of stay; 38% reduction in complications.

- Integrated nursing support during intravesical therapy: Patient satisfaction improvement (Cohen's d=−6.39; P<0.001); 100% treatment compliance; anxiety/depression reduction (P<0.001).

- Extended nursing services with systemic therapy: Renal function preservation; quality of life enhancement; caregiver burden reduction (P<0.05)

- Digital health platforms: Continuous support delivery; caregiver burden reduction; disease knowledge improvement; feasible implementation during COVID-19 pandemic

- Comprehensive stoma education: Stoma knowledge improvement (Cohen's d=−1.60; P<0.001); self-efficacy enhancement; quality of life improvement

- Structured psychosocial interventions: Anxiety reduction (Cohen's d=5.51; P<0.001); depression reduction (Cohen's d=4.76; P<0.001); fear of recurrence reduction.

4.7. Evidence Gaps and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | Full Form |

| BC | Bladder Cancer |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CRIS | Cancer Resource and Information System |

| ERAS | Enhanced Recovery After Surgery |

| ESMO | European Society of Medical Oncology |

| GSES | General Self Efficacy Scale Scores |

| HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| LOS | Length Of Stay |

| MIBC | Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer |

| N | Number |

| NMIBC | Non- Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer |

| P | Probability (P-Value) |

| PRO | Patient Reported Outcomes |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| RR | Risk Ratio |

| SAS | Self-Rating Anxiety Scale |

| SDS | Self-Rating Depression Scale |

| UI | Urinary Incontinence |

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2021;71(3):209-49. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Rumgay H, Li M, Yu H, Pan H, Ni J. The global landscape of bladder cancer incidence and mortality in 2020 and projections to 2040. Journal of global health. 2023;13:04109. [CrossRef]

- Antoni S, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Znaor A, Jemal A, Bray F. Bladder cancer incidence and mortality: a global overview and recent trends. European urology. 2017;71(1):96-108. [CrossRef]

- Saginala K, Barsouk A, Aluru JS, Rawla P, Padala SA, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of bladder cancer. Medical sciences. 2020;8(1):15. [CrossRef]

- Khaled H. Schistosomiasis and cancer in Egypt: Review. J Adv Res. 2013 Sep;4(5):461-6. PMID: 25685453; PMCID: PMC4293882. [CrossRef]

- Zuo J, Chen J, Tan Z, Zhu X, Wang H, Fu S, Wang J. Analysis of long-term trends and 15-year predictions of smoking-related bladder cancer burden in China across different age and sex groups from 1990 to 2021. Discover Oncol. 2025 Mar 27;16:408. [CrossRef]

- Kiebach J, Beeren I, Aben KKH, Witjes JA, van der Heijden AG, Kiemeney LALM, Vrieling A. Smoking behavior and the risks of tumor recurrence and progression in patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2025;156(2):E123-E132. PMID: 39521345. [CrossRef]

- Chorbińska J, Krajewski W, Nowak Ł, Bardowska K, Żebrowska-Różańska P, Łaczmański Ł, Pacyga-Prus K, Górska S, Małkiewicz B, Szydełko T. Is the urinary and gut microbiome associated with bladder cancer? Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2023;17:11795549231206796. [CrossRef]

- Hussein AA, Smith G. The association between the urinary microbiome and bladder cancer. Urol Clin North Am. 2023;50(1):81-9. [CrossRef]

- Gherasim RD, Chibelean C, Porav-Hodade D, Todea-Moga C, Tătaru SO, Reman TL, Vida AO, Ghirca MV, Ferro M, Martha OKI. Microbiome shifts in bladder cancer: a narrative review of urobiome composition, progression, and therapeutic impact. Medicina (Kaunas). 2025;61(8):1401. [CrossRef]

- Stamatakos PV, Fragkoulis C, Zoidakis I, Ntoumas K, Kratiras Z, Mitsogiannis I, Dellis A. A review of urinary bladder microbiome in patients with bladder cancer and its implications in bladder pathogenesis. World J Urol. 2024;42:457. [CrossRef]

- Roje B, Zhang B, Mastrorilli E, Kovačić A, Sušak L, Ljubenkov I, Ćosić E, Vilović K, Meštrović A, Lozo Vukovac E, Bučević-Popović V, Puljiz Ž, Karaman I, Terzić J, Zimmermann M. Gut microbiota carcinogen metabolism causes distal tissue tumours. Nature. 2024;632(8019):580-586. [CrossRef]

- Mani S. Gut microbiome and bladder cancer: A new link through nitrosamine metabolism. Cell Host Microbe. 2024;32(8):1001-1003. [CrossRef]

- Ginwala R, Bukavina L, Sindhani M, Nachman E, Peri S, Franklin J, Drevik J, Christianson S, Geynisman DM, Kutikov A, Abbosh PH. Bladder cancer microbiome and its association with chemoresponse. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1506319. [CrossRef]

- Liang Z, Wang X, Xie B, Zhu Y, Wu J, Li S, Meng S, Zheng X, Ji A, Xie L. Pesticide exposure and risk of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016 Oct 11;7(41):66959-66970. PMID: 27689300; PMCID: PMC5341990. [CrossRef]

- Lucchesi CA, Vasilatis DM, Mudryj M, Ghosh PM. Pesticides and bladder cancer: mechanisms leading to anti-cancer drug chemoresistance and new chemosensitization strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(14):11395. PMID: 37510855; PMCID: PMC10372773. [CrossRef]

- Botteman MF, Pashos CL, Redaelli A, Laskin B, Hauser R. The health economics of bladder cancer: a comprehensive review of the published literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21(18):1315-30.

- Sylvester RJ, Van Der Meijden AP, Oosterlinck W, Witjes JA, Bouffioux C, Denis L, et al. Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: a combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur Urol. 2006;49(3):466-77. [CrossRef]

- https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/.

- Mohamed NE, Pisipati S, Lee CT, Goltz HH, Latini DM, Gilbert FS, et al., editors. Unmet informational and supportive care needs of patients following cystectomy for bladder cancer based on age, sex, and treatment choices. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations; 2016: Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Smith AB, Jaeger B, Pinheiro LC, Edwards LJ, Tan HJ, Nielsen ME, et al. Impact of bladder cancer on health-related quality of life. BJU international. 2018;121(4):549-57. [CrossRef]

- Cerruto MA, D'Elia C, Siracusano S, Gedeshi X, Mariotto A, Iafrate M, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of non RCT's on health related quality of life after radical cystectomy using validated questionnaires: Better results with orthotopic neobladder versus ileal conduit. Eur J Surg Oncol (EJSO). 2016;42(3):343-60. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Chen Y, Gu J. Effectiveness of integrated nursing interventions in enhancing patient outcomes during postoperative intravesical instillation for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: A comparative study. Medicine. 2024;103(11):e36871. [CrossRef]

- Grant M, Economou D, Ferrell B. Oncology nurse participation in survivorship care. Clin J Oncol Nursing. 2010;14(6):709. [CrossRef]

- Charalambous A, Wells M, Campbell P, Torrens C, Östlund U, Oldenmenger W, et al. A scoping review of trials of interventions led or delivered by cancer nurses. Int J Nursing studies. 2018;86:36-43. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Yang K, Gong F, Wu Y, Tang S. Application of rapid rehabilitation nursing in perioperative period of laparoscopic radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer patients. J Nanomaterials. 2021;2021(1):9934539. [CrossRef]

- Fearon KCH, Ljungqvist O, Von Meyenfeldt M, Revhaug A, Dejong CHC, Lassen K, Nygren J, Hausel J, Soop M, Andersen J, Kehlet H. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a consensus review of clinical care for patients undergoing colonic resection. Clin Nutr. 2005;24(3):466-477. PMID: 15896435. [CrossRef]

- Peng F, Meng Y, Sun L, Dong B, Xu G, Liu S, et al. People-Oriented Nursing Mode on the Negative Emotions and Psychological Status of Patients with Bladder Cancer. Iran J Public Health. 2024;53(5):1087. [CrossRef]

- Fan X, Li H, Lai L, Zhou X, Ye X, Xiao H. Impact of internet plus health education on urinary stoma caregivers in coping with care burden and stress in the era of COVID-19. Front Psychol. 2022;13:982634. [CrossRef]

- Bessa A, Rammant E, Enting D, Bryan RT, Shamim Khan M, Malde S, et al. The need for supportive mental wellbeing interventions in bladder cancer patients: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0243136. [CrossRef]

- MacLennan SJ, MacLennan S. How do we meet the supportive care and information needs of those living with and beyond bladder cancer? Front Oncol. 2020;10:465.

- Shaffer KM, Turner KL, Siwik C, Gonzalez BD, Upasani R, Glazer JV, et al. Digital health and telehealth in cancer care: a scoping review of reviews. Lancet Digital Health. 2023;5(5):e316-e27. [CrossRef]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009 Jul 21;6(7):e1000097. PMID: 19621072; PMCID: PMC2707599. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. PMID: 33782057; PMCID: PMC8005924. [CrossRef]

- Song Y, Ren P, Wu Y, Zhang B, Wang J, Li Y. Efficacy of long-term extended nursing services combined with atezolizumab in patients with bladder cancer after endoscopic bladder resection. Medicine. 2022;101(38):e30690. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Guo S, Gan S, Xu Q. “Internet Plus” continuous nursing for patients with advanced bladder cancer: A retrospective observational study. Medicine. 2024;103(15):e37822. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf W, Hamid A, Malik SA, Khawaja R, Para SA, Wani MS, et al. Integrated enhanced recovery after surgery protocol in radical cystectomy for bladder tumour—A retroprospective study. BJUI compass. 2024;5(11):1183-94. [CrossRef]

- Zhang T, Qi X. Enhanced Nursing Care for Improving the Self-Efficacy & Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with a Urostomy. J Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2023:297-308. [CrossRef]

- Leow JJ, Catto JW, Efstathiou JA, Gore JL, Hussein AA, Shariat SF, et al. Quality indicators for bladder cancer services: a collaborative review. Euro Urol. 2020;78(1):43-59. [CrossRef]

- Grassi L, Caruso R, Riba M, Lloyd-Williams M, Kissane D, Rodin G, et al. Anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline. ESMO open. 2023;8(2):101155. [CrossRef]

- Diefenbach MA, Marziliano A, Siembida EJ, Mistretta T, Pfister H, Yacoub A, et al. Cancer Resource and Information Support (CRIS) for bladder cancer survivors and their caregivers: development and usability testing study. JMIR Formative Research. 2023;7:e41876. [CrossRef]

- Kim Y, Lee H, Park J, Lee S. A mobile-based mental health improvement program for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer patients: Program development and feasibility protocol. Euro Psychiatry. 2023;66(S1):S362-S3. [CrossRef]

- Lemiński A, Kaczmarek K, Bańcarz A, Zakrzewska A, Małkiewicz B, Słojewski M. Educational and psychological support combined with minimally invasive surgical technique reduces perioperative depression and anxiety in patients with bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy. Int J Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(24):13071. [CrossRef]

- Thomas KR, Joshua C, Ibilibor C. Psychological Distress in Bladder Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Cancer medicine. 2024;13(22):e70345. [CrossRef]

- Wulff-Burchfield EM, Potts M, Glavin K, Mirza M. A qualitative evaluation of a nurse-led pre-operative stoma education program for bladder cancer patients. Supp Care in Cancer. 2021;29(10):5711-9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang T, Qi X. Caregiver Burden in Bladder Cancer Patients with Urinary Diversion Post-Radical Cystectomy and the Need for Comprehensive Nursing Education: A Narrative Literature. J Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2024:3825-34. [CrossRef]

- Ding J-Y, Pan T-T, Lu X-J, You X-M, Qi J-X. Effects of peer-led education on knowledge, attitudes, practices of stoma care, and quality of life in bladder cancer patients after permanent ostomy. Front Medicine. 2024;11:1431373. [CrossRef]

- Solera-Gomez S, Benedito-Monleon A, LLinares-Insa LI, Sancho-Cantus D, Navarro-Illana E, editors. Educational needs in oncology nursing: a scoping review. Healthcare. 2022: MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Xu M, Chen S, Liu X, Luo Y, Wang D, Lu H, et al. Best evidence for rehabilitation management of urinary incontinence in patients with bladder cancer following orthotopic neobladder reconstruction. Asia-Pacific J Oncol Nursing. 2025;12:100647. [CrossRef]

- Biswas J, Bhuiyan AKMMR, Alam A, Chowdhury MK. Effect of perceived social support on cancer patients: a narrative review. Acad Oncol. 2025 Apr 29;2025:7681. [CrossRef]

- Qian L, Zhang Y, Chen H, Pang Y, Wang C, Wang L, et al. The clinical effect of gratitude extension-construction theory nursing program on bladder cancer patients with fear of cancer recurrence. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1364702. [CrossRef]

- Alqaisi O, Subih M, Joseph K, Yu E, Tai P. Oncology Nurses' Attitudes, Knowledge, and Practices in Providing Sexuality Care to Cancer Patients: A Scoping Review. Curr Oncol. 2025;32(6):337-46. PMID: 40558280; PMCID: PMC12191979. [CrossRef]

- Alqaisi O, Al-Ghabeesh S, Tai P, Wong K, Joseph K, Yu E. A narrative review of nursing roles in addressing sexual dysfunction in oncology patients. Curr Oncol. 2025;32(8):457-75. PMID: 40862826; PMCID: PMC12384569. (impact factor 3.4). [CrossRef]

- Woo BFY, Lee JXY, Tam WWS. The impact of the advanced practice nursing role on quality of care, clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, and cost in the emergency and critical care settings: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):63. PMID: 28893270; PMCID: PMC5594520. [CrossRef]

| Author/year | Purpose | Settings | Sample size | Study design | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang (2024) [23] | Evaluate effectiveness of integrated nursing intervention on patient outcomes during postoperative intravesical installations for NMIBC | Hospital oncology ward | n= 100 NMIBC patients | Comparative RCT | Integrated nursing interventions significantly improved patients’ satisfaction (P˂0.001), treatment compliance, self- efficacy, and QoL; reduced anxiety and depression. |

| Song (2022) [35] | Assess efficacy of long- term extended nursing services combined with atezolizumab in BC patients after endoscopic bladder resection | Hospital urology department | N=126 BC patients | Randomized controlled trial | Extended nursing services improved renal function, QoL, and satisfaction; reduced caregiver burden, anxiety and depression (P˂0.05) |

| Zhang (2024) [36] | Evaluate continuous nursing interventions via internet plus platform for advanced BC patients with hematuria | Tertiary hospital | N=43 advanced BC patients | Retrospective observational study |

Internet plus nursing improved coping style, disease knowledge, reduced caregiver burden, increased patients’ satisfaction. |

| Ashraf (2024) [37] | Compare integrated ERAS protocol with traditional preoperative care in radial cystectomy | Tertiary referral urology center | N=94 BC patients | Retrospective comparative | ERAS significantly reduced hospital stay (11 vs. 17 days, p˂), faster recovery, reduced complications by 38% |

| Bessa (2021) [30] | Systematic review supportive mental wellbeing intervention for BC patients | Literature review (multiple centers) | Systematic review |

Systematic review and synthesis | No BC-specific mental health interventions found; identified critical gap in psychosocial support* |

| Zhang & Qi (2023) [38] | Synthesize evidence on enhanced nursing care for self-efficacy and HRQoL in urostomy patients | Literature review (multiple centers) | Systematic review of 10 studies |

Systematic review | Preoperative education critical for psychological preparation; postoperative interventions improved self-efficacy and HRQoL. |

| Charalambous (2018) [25] | Scope trials of cancer nurse-led intervention across cancer care continuum | Multiple cancer centers globally | Scoping review of 214 studies | Scoping review | Most interventions during treatment phase; focused in education and counseling; improve multiple outcomes. |

| Leow (2019) [39] | Develop and validate quality indicators for bladder cancer services | Multidisciplinary BC care centers | Mutli- stakeholder collaboration | Guideline development | Established quality indicators for NMIBC/MIBC ; emphasizes preoperative counseling, stoma marking ERAS protocols |

| Grassi (2023) [40] | Provide ESMO guideline on managing anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients | Guideline development consensus |

Expert consensus | Clinical practice guideline (ESMO) | Recommend cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness; anxiety/depression common but underrecognized |

| Diefenbach (2023) [41] | Evaluate gratitude nursing program on fear of cancer recurrence in BC patients | Hospital oncology unit | N= 80 BC patients | Comparative study | Improved QoL, reduced fear, depression, anxiety; improved treatment compliance vs. routine care |

| Peng (2024) [28] | Assess people-oriented nursing mode on psychological status of BC patients | Hospital oncology department | N=80 BC patients | Comparative study | Reduced anxiety and depression, improved QoL vs. conventional nursing |

| Lee (2023) [42] | Develop and test mobile based mental health program for NMIBC patients | Ambulatory urology clinic |

Pilot feasibility study | Protocol and feasibility | Mobile program via Kakao talk demonstrated feasibility; potential for mental health improvement |

| Leminski (2021) [43] | Evaluate combined educational and psychological support reducing perioperative anxiety in MIBC patients | Tertiary cancer center | n= 148 MIBC patients | Comparative study | Cystocare program significantly reduced perioperative depression (P˂0.001) and anxiety |

| Thomas (2024) [44] | Systematic review psychological distress and identify risk factors in BC patients | Literature review (multiple studies) | Systematic review of 17 studies (n=2.572) | Systematic review | Risk factors: advanced stage younger age, female sex, preoperative; protective: social support |

| Wulff-Burchfield, (2024) [45] | Qualitatively evaluate nurse-led preoperative stoma education for BC patients | Preoperative education clinic | N=24, patients and caregiver | Qualitative evaluation | Interactive education with patients advocates optimally preppers for ostomy and reduce distress |

| Zhang (2024) [46] | Narrative review caregiver burden nursing education for BC patients with urinary diversion | Literature review (2018-2023) | Narrative review | Narrative literature review | Nurse-led stoma education enhanced caregiver comprehension and reduced burden/stress |

| Ding (2024) [47] | Evaluate peer-led education on stoma care and QoL in BC patients with permanent ostomy | Hospital stoma care clinic | N= 340 BC patients with ostomy | Randomized controlled trial | Peer-led intervention improved stoma care knowledge (P˂0.001) attitude, practices, and QoL |

| Solera-Gomez (2022) [48] | Scope educational needs for oncology nurses | Literature review (oncology settings) | Scoping review of multiple studies | Scoping review | Key needs: communication, coping, stress, prevention, continuous, technical skill development |

| Xu (2024) [49] | Synthesize best evidence for urinary incontinence management post-neobladder | Literature review | Evidence synthesis of multiple studies | Evidence synthesis | Comprehensive UI assessment, conservative, treatment, nursing equipment use, structured follow-up |

| Fan (2022) [29] | Evaluate internet plus health education on caregiver burden in COVID-19 era | Virtual and home-based platform | N= 80 caregiver of stoma patients | Randomized controlled trial | Internet plus education reduced caregiver burden and enhanced coping ability (P˂0.05) |

| Authors /years | Study designs | Sample size (n) | Primary outcomes | Effect size/statistical significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashraf (2024) (23)[32] | Retrospective comparative | 94 | Hospital stays reduction (11 vs. 17 days); complication reduction | 35% LOS reductions;38% complication reduction (p˂0.05) |

| Leminski, A. (2021) (29)[43] | Comparative study | 148 | Perioperative anxiety /depression reduction | Significant reduction in anxiety /depression scores (P˂0.001) |

| Leow (2019) (25)[39] | Clinical guideline development | Experts’ consensus | Quality indicators establishment | Preoperative counseling, stoma marking, ERAS protocols standardized |

| Author /years | Study design | Sample size (n) | Main findings | Effect size/statistical significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang (2024) [23] | Randomized controlled trial | 100 | Patients’ satisfaction compliance, self-efficacy, QoL improvement | Satisfaction Cohen’s d= - 6.39 (P˂0.001); compliance 100% vs 84%; anxiety reduction (Cohen’s d= 5.51, P˂0.001) |

| Song (2022) [35] |

Randomized controlled trial | 126 | Renal function preservation, reduced caregiver burden | Improved renal function, reduced burden /anxiety /depression (P˂0.05) |

| Authors /years | Intervention type | Population (N) | Outcomes | Implementation feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang (2024) [36] | Internet plus continuous nursing platform | Advanced BC with hematuria (43) | Improved coping, disease knowledge, reduced caregiver burden | Successfully implemented in hospital settings: scalable |

| Kim (2023) [42] | Mobile-based mental health (Kakao talk) | NMIBC patients’ pilot (n= feasibility) | Feasibility demonstrated; potential for mental health improvement | Pilot phase; ready for expansion |

| Diefenbach (2023) [41] | Web-based CRIS platform | BC survivor (7) | High usability; addresses practical /psychosocial /educational needs | User-friendly interface; practical information accessible |

| Fan (2022) [29] | Internet plus health education for caregivers | Caregivers of stoma patients (80) | Reduced caregiver burden; enhanced coping ability (P˂0.05) | Effective during COVID-19 pandemic; widely applicable |

| Authors/years | Study design | Sample size (n) | Key findings | Effect size/impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang (2023) [38] | Systematic review of 10 studies | 10 studies reviewed | Preoperative education critical; postoperative care improved self-efficacy and HRQoL | Consistent improvement across studies; moderate to strong effect sizes |

| Wulff-Burchfield (2024) [45] | Qualitative evaluation | 24 (patients & caregivers) | Interactive education optimally prepared patients; reduced distress | Qualitative evidence of psychological benefit and preparedness |

| Wang (2024) [23] | Randomized controlled trial | 340 | Peer-led education improved knowledge, attitudes, practices, QoL | Stoma knowledge Cohen’s d=1.60 (P˂0.001); sustained improvement |

| Zhang and Qi (2025) [46] | Narrative review | Literature 2018- 2023 | Enhanced caregiver comprehension; reduced burden/stress | Systematic evidence synthesis; reproducible outcomes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).