Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and immunologic divergence

1.2. Clinical dilemma and objective of this review

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Reporting Standards

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Results and Discussion

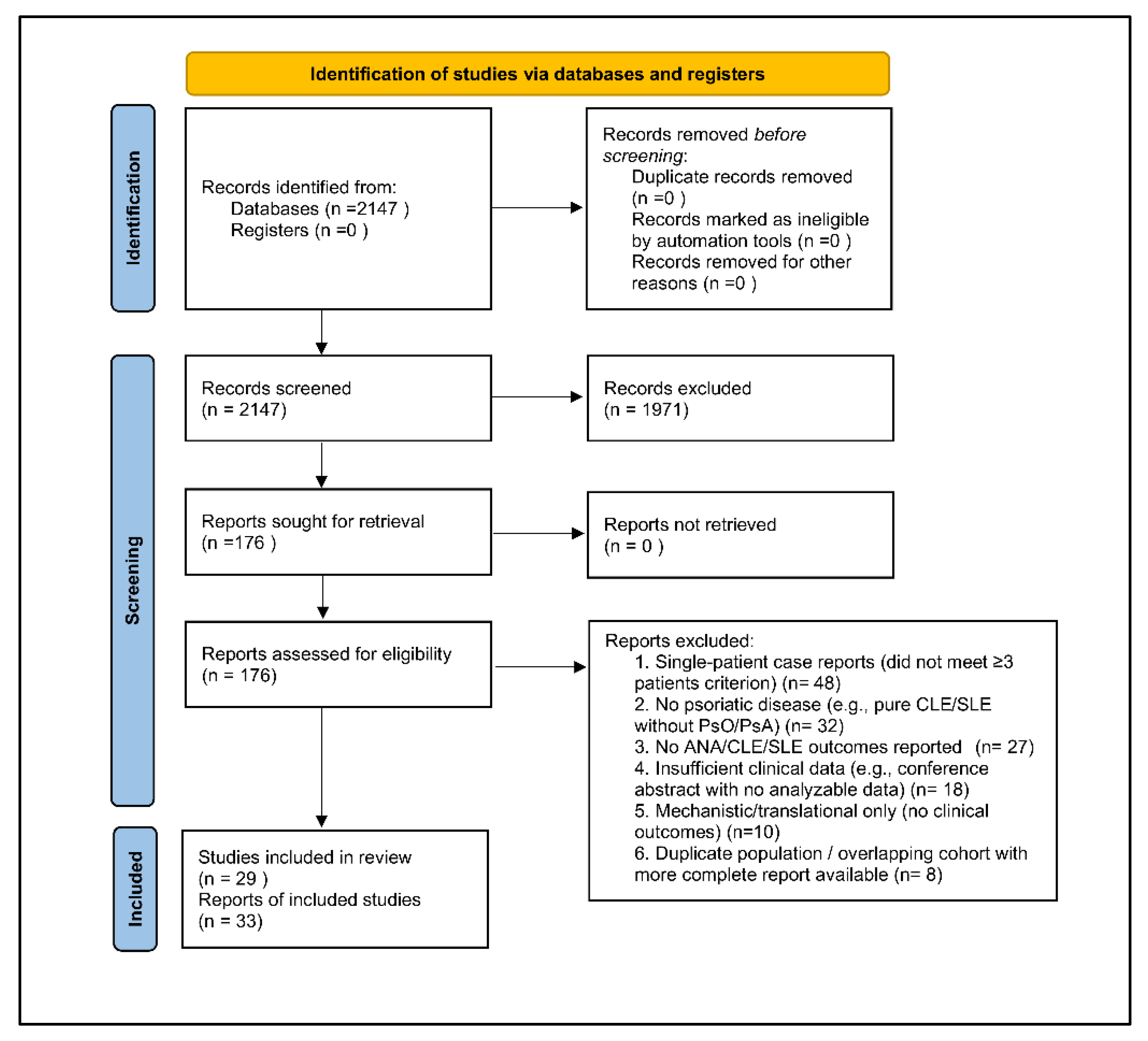

3.1. Study Selection

| Study Type | Assessment Tool | Number of Studies | Risk of Bias Category | Common Sources of Bias Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) | Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 | 2 | Low to moderate | Lack of blinding in outcome assessment; small sample sizes in lupus-specific subgroups |

| Prospective Cohort Studies | Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) | 9 | Low to moderate | Incomplete follow-up; non-standardized ANA/CLE outcome definitions; limited adjustment for confounding |

| Retrospective Cohort Studies | Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) | 10 | Moderate | Selection bias, incomplete documentation of lupus-related outcomes, variability in biologic exposure duration |

| Registry Studies | Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) | 2 | Low to moderate | Missing data on lupus activity indices; potential reporting bias |

| Case Series (≥3 patients) | Murad Methodological Quality Tool | 10 | Moderate to high | Lack of comparator groups; selective reporting; inconsistent serologic measurements; variable diagnostic rigor for CLE/SLE |

| Overall Summary | — | 33 included papers (29 unique studies) | Predominantly moderate risk of bias | Heterogeneity in study design, inconsistent lupus outcome reporting, non-standardized ANA thresholds, small subsample sizes in CLE/SLE phenotypes |

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

| Subgroup | Study ID (with inline reference) | Country | Design | Biologic(s) | Sample Size | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Psoriasis + ANA Positivity (No Lupus) | Pink 2010 [35] | UK | Prospective cohort | Etanercept | n=16 | ANA induction; no CLE/SLE |

| Pirowska 2015 [36] | Poland | Prospective cohort | Infliximab, Adalimumab | n=30 | 20% ANA seroconversion; no clinical autoimmunity | |

| Bardazzi 2014 [37] | Italy | Cohort | Anti-TNF | n=48 | ANA ↑; no lupus-like disease | |

| Oter-López 2017 [38] | Spain | Retrospective cohort | Anti-TNF | n=21 | ANA changes | |

| Yanaba 2016 [39] | Japan | Prospective | Ustekinumab | n=14 | Rare ANA rise; benign | |

| Miki 2019 [40] | Japan | Prospective | Secukinumab | n=10 | No lupus-like events | |

| Kutlu 2020 [41] | Turkey | Case series | Anti-TNF; Ustekinumab | n=9 | ANA monitoring; no autoimmune sequelae | |

| Sugiura 2021 [42] | Japan | Cohort | Ixekizumab | n=17 | ANA stable | |

| Miyazaki 2023 [43] | Japan | Case series | Guselkumab | n=7 | ANA elevation without CLE/SLE | |

| B. Psoriasis + Cutaneous Lupus (CLE) | Staniszewska 2025 [44] | Poland | Case series | Various | n=4 | PsO + CLE; PsA + CLE; SCLE/DLE phenotypes |

| García-Arpa 2019 [45] | Spain | Case series | Anti-TNF | n=3 | TNF-induced CLE; PsA cases included | |

| De Souza 2012 [46] | Canada | Case series | Anti-TNF | n=2 | Classic TNF-induced CLE | |

| Sachdeva 2020 [47] | USA | Case report / small series | Anti-TNF | n=1 | TNF-induced CLE; photosensitive eruption | |

| Prieto-Barrios 2017 [48] | Spain | 21-patient cohort | Etanercept, Adalimumab | CLE subset = 2 | 2 developed CLE-like lesions | |

| Zalla & Muller 1996 [49] | USA | Retrospective chart review | NA | CLE subset = 2 | Oldest known PsO + CLE record; PsA included | |

| C. Psoriasis + Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | Prieto-Barrios 2017 [48] | Spain | Mixed cohort | Etanercept, Adalimumab | SLE subset = 4 | Overlaps PsO + CLE |

| Zalla & Muller 1996 [49] | USA | Retrospective | NA | n=6 | Overlaps CLE + PsA | |

| Hays 1984 [50] | USA | Case series | NA | n=5 | First PsO + SLE documentation | |

| Tselios 2017 [51] | Canada | Case series | NA | n=4 | PsO before SLE | |

| Ali 2025 [52] | USA | Cureus | Anti-TNF | n=3 | Overlaps PsA + CLE | |

| Walhelm 2025 [53] | Sweden | Lupus Sci Med | Anti-TNF | n=2 | Anti-TNF–related SLE flare | |

| D. Psoriatic Arthritis + ANA Positivity | Johnson 2005 [55] | Canada | Cohort | Anti-TNF | n=28 | ANA induction only |

| Silvy 2015 [56] | France | Cohort | Anti-TNF | n=63 | ANA ↑ without lupus | |

| Viana 2010 [54] | Brazil | Cohort | Anti-TNF | n=17 | ANA-only PsA | |

| Kara 2025 [57] | Turkey | Case series | Anti-TNF | n=6 | ANA+ PsA; no lupus | |

| Eibl 2023 [58] | Germany | EULAR abstract | Anti-TNF | n=54 | ANA serology reported | |

| E. Psoriatic Arthritis + Cutaneous Lupus (CLE) | Staniszewska 2025 [44] | Poland | Case series | Various | PsA + CLE = 2 | Derived from PsO + CLE |

| Walz LeBlanc 2020 [59] | USA | Case report | Anti-TNF | n=1 | TNF-induced CLE | |

| Ali 2025 [52] | USA | Cureus | Anti-TNF | n=2 | Overlaps PsO + SLE | |

| García-Arpa 2019 [45] | Spain | Case report | Anti-TNF | n=1 | Overlaps PsO + CLE | |

| F. Psoriatic Arthritis + Systemic Lupus (SLE) | Avriel 2007 [61] | Israel | Case series | NA | n=2 | First report of true PsA + SLE |

| Bonilla 2016 [62] | USA | Retrospective SLE cohort | Various / mixed | n=20 | High PsA rate among SLE pts | |

| Korkus 2021 [63] | Israel | Population case–control | Real-world DMARDs/biologics | n=18 | PsA pts have 2.3× higher SLE prevalence | |

| Sato 2020 [64] | Japan | Case report | Secukinumab (IL-17i) | n=1 | PsA improved; SLE stable | |

| Venetsanopoulou 2025 [65] | Greece | Case-based series + review | Various | n=7 | IL-17 axis & treatment dilemmas |

3.3. Biologic Agents and Exposure Patterns

3.4. Treatment Patterns and Clinical Outcomes Across Subgroups

3.4.1. Psoriasis With ANA Positivity (No Clinical Lupus)

3.4.2. Psoriasis With Cutaneous Lupus (CLE)

3.4.3. Psoriasis With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

3.4.4. PsA With ANA Positivity

3.4.5. PsA With Cutaneous Lupus (CLE)

3.4.6. PsA With Systemic Lupus (SLE)

3.5. Comparative Safety Signals

| Therapeutic Class | ANA Seroconversion | dsDNA Induction | CLE Worsening / Induction | SLE Flares / Drug-Induced Lupus (DIL) | Psoriasis/PsA Flares | Other Relevant Safety Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α inhibitors | High (15–30%) [35,36,37,38] | Frequent [10,18,45,46,47,48,49] | Documented TNF-i–induced DLE/SCLE [45,46,47,48,49] | Highest risk (6–15% DIL; true SLE flares reported) [10,18,48,49,50,51,52,53] | None | Strongly associated with autoantibody activation; avoid in CLE/SLE [10,18,35,36,37,38,45,46,47,48,49,52,53] |

| IL-17 inhibitors | Low–moderate [40,42] | Rare [28,29,30,31,32,33] | Strongest signal; multiple reports of DLE/SCLE induction or worsening [28,29,30,31,32,33] | Very rare [28,29,30,31,32,33] | None | Mechanistically may unmask IFN-dominant pathways; avoid in active CLE [9,20,28,29,30,31,32,33] |

| IL-23 inhibitors | Very low [12,13,14,43] | Very low [12,13,14] | No signal to date [12,13,14,43] | No SLE flares; no DIL [12,13,14] | None | Most favorable cross-disease safety profile [12,13,14,43] |

| IL-12/23 inhibitor (ustekinumab) | Very low [39,46] | Minimal [46] | None reported [39,46] | Safe across Phase II/III SLE trials; no DIL [46] | None | Stable safety despite inconsistent SLE efficacy [46,48] |

| TYK2 inhibitor (deucravacitinib) | Very low [25,26,27] | None [25,26,27] | Improves CLE molecular features [26] | Potential benefit in SLE (Phase II trial) [25,26,27] | None | Dual IL-23 and IFN-I pathway suppression; promising in overlap disease [25,26,27] |

| PDE4 inhibitor (apremilast) | None [16] | None [16] | None reported [16] | None [16] | None | Very safe across ANA+, CLE, and SLE populations [16] |

| Methotrexate (MTX) | None [6,11] | None [6,11] | Neutral [6,11] | Safe in SLE; reduces flare frequency [6,11] | None | Useful when lupus activity predominates [6,11] |

| Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) | None [6,11] | None [6,11] | Improves CLE lesions [6,11,20] | Standard SLE therapy; protective [6,11] | None | Preferred in SLE-dominant PsO/PsA overlap [6,11,20] |

| Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) | None [47,51] | None [47,51] | Beneficial for CLE [47,51] | Standard SLE therapy [6,11] | Known trigger of psoriasis flares [47,51] | Avoid in active psoriasis/PsA unless lupus dominates [47,51] |

| Rituximab | None; may reduce pathogenic autoantibodies [59] | Often lowers anti-dsDNA titers [59] | Can improve refractory CLE/SLE skin disease [59] | Effective for severe SLE and systemic autoimmune disease [59] | Paradoxical de novo psoriasis or flares [59] | Multiple reports show worsening psoriasis after rituximab, improving after withdrawal; may shift immune balance toward IL-23/Th17 axis [59] |

| Phototherapy (UVB/NB-UVB) | May increase ANA in high-titer patients [20] | None | Can provoke CLE (photo-induced DLE/SCLE) [9,20] | Contraindicated in SLE [9,20] | None | UV enhances IFN-I signaling; use cautiously in ANA-high/ENA+ patients [9,20,47] |

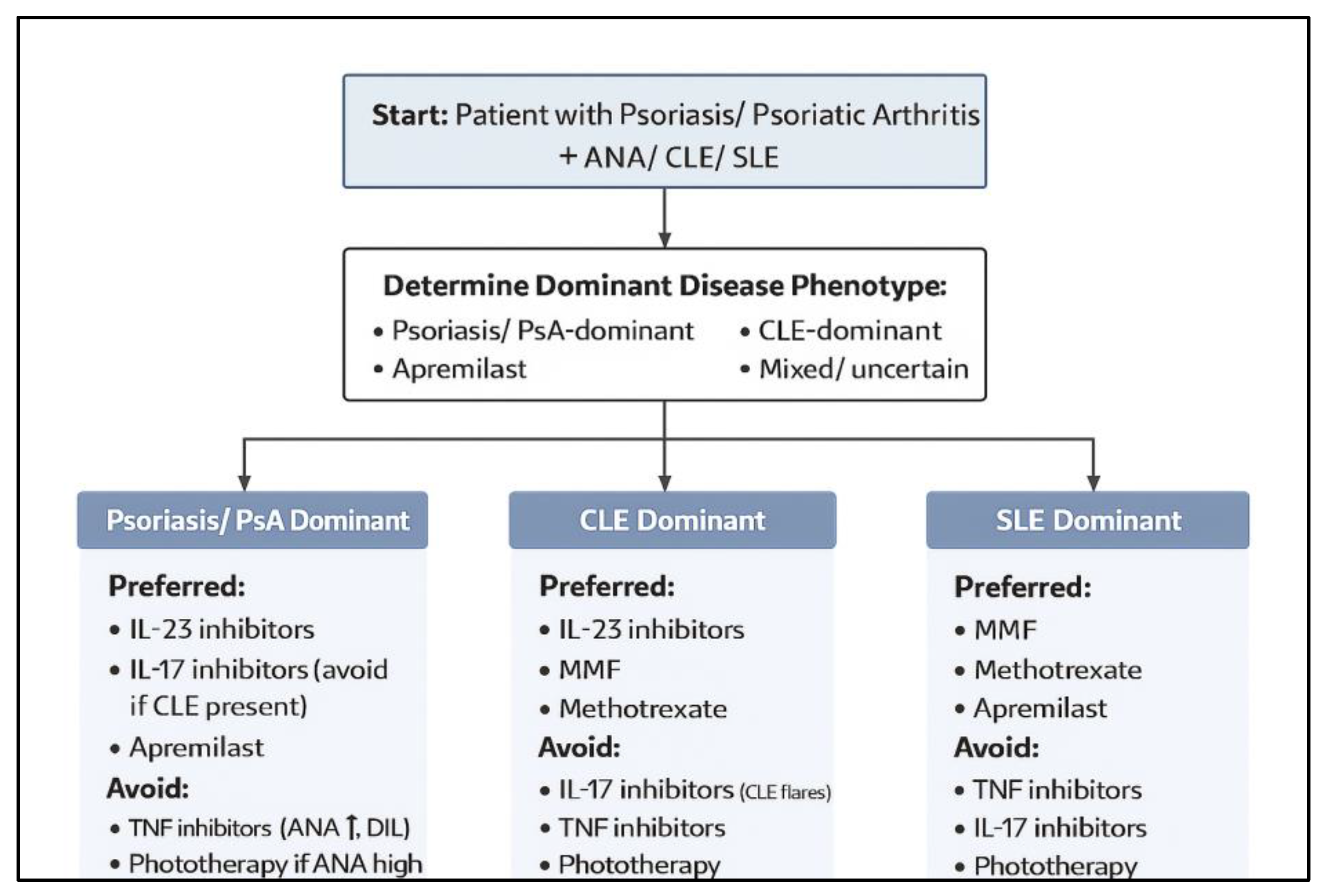

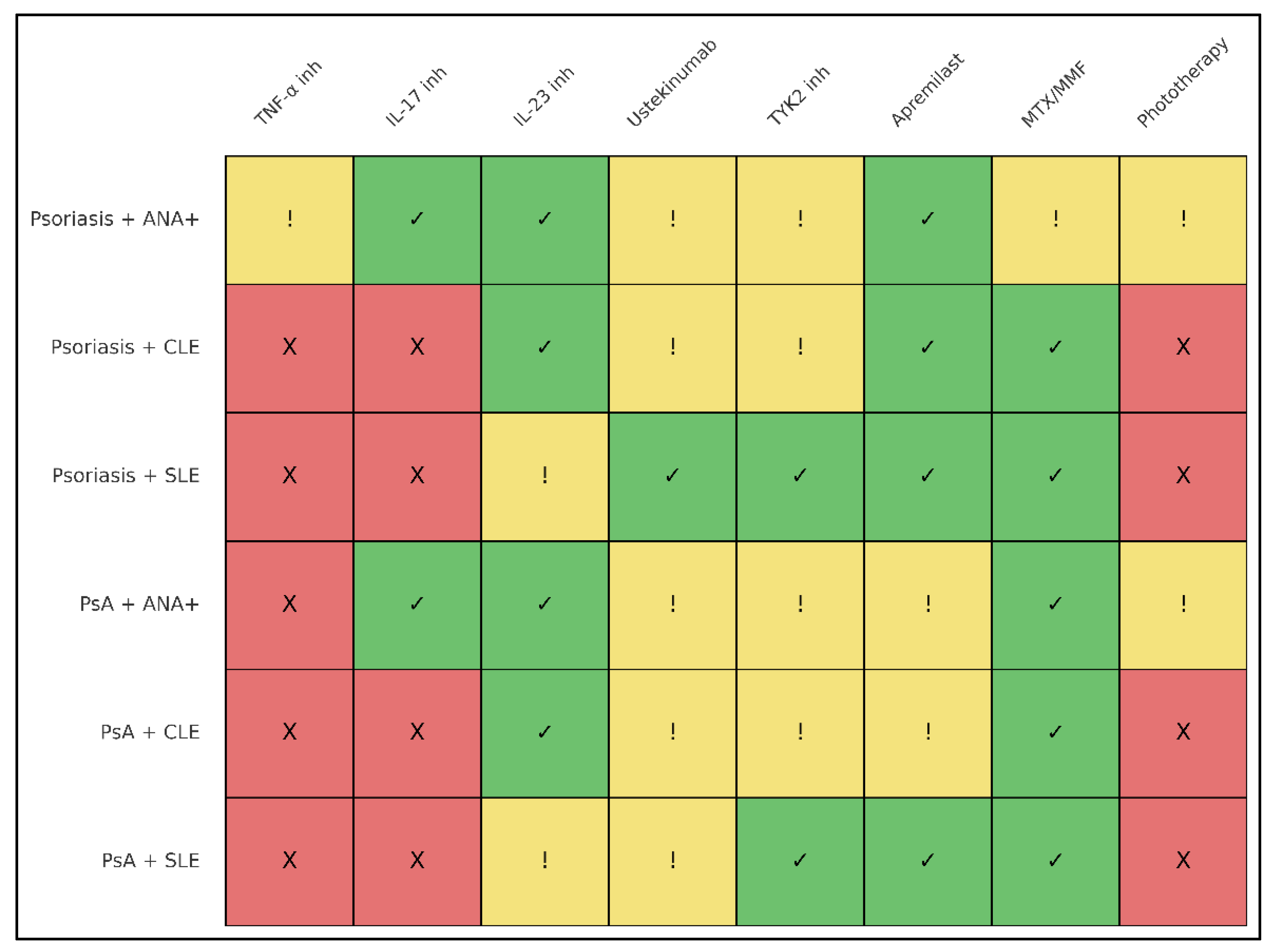

3.6. Summary of Therapeutic Suitability by Subgroup

| Patient Subgroup | Preferred Therapies | Acceptable / Conditional Options | Contraindicated / Use with Strong Caution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis + ANA positivity | IL-23 inhibitors [12,13,14,43]; IL-17 inhibitors [40,42]; apremilast [16] | Methotrexate [6,11]; narrowband UVB in low-titer ANA, no lupus features [20] | TNF-α inhibitors [10,18,35,36,37,38]; high-dose / broad-spectrum phototherapy in high-titer ANA or ENA-positive patients [9,20,47] |

| Psoriasis + CLE | IL-23 inhibitors [12,13,14,43]; apremilast [16]; methotrexate [6,11] | Ustekinumab (IL-12/23) [39,46]; low-dose systemic steroids (short-term) [6,11] | IL-17 inhibitors (CLE induction/worsening) [28,29,30,31,32,33]; TNF-α inhibitors [45,46,47,48,49]; hydroxychloroquine if psoriasis active [47,51]; intensive phototherapy [9,20] |

| Psoriasis + SLE | Mycophenolate mofetil [6,11]; methotrexate [6,11]; apremilast [16]; TYK2 inhibitor (deucravacitinib) [25,26,27]; ustekinumab (safe, modest efficacy) [46] | IL-23 inhibitors in stable SLE [12,13,14]; hydroxychloroquine if psoriasis mild & monitored [47,51] | TNF-α inhibitors [10,18,48,49,50,51,52,53]; IL-17 inhibitors [28,29,30,31,32,33]; phototherapy in established SLE or active CLE [9,20,47] |

| Psoriatic arthritis + ANA positivity | IL-17 inhibitors [40,42]; IL-23 inhibitors [12,13,14,43]; methotrexate [6,11] | Apremilast [16]; low-dose systemic steroids as bridge [6,11] | TNF-α inhibitors (autoantibody induction, DIL risk) [10,18,54,55,56,57] |

| Psoriatic arthritis + CLE | Mycophenolate mofetil [6,11]; methotrexate [6,11]; IL-23 inhibitors [12,13,14,43] | Ustekinumab [39,46,48]; apremilast [16] | IL-17 inhibitors (CLE flare risk) [28,29,30,31,32,33]; TNF-α inhibitors [45,46,47,48,49]; hydroxychloroquine (psoriasis/PsA flare risk) [47,51] |

| Psoriatic arthritis + SLE | Mycophenolate mofetil [6,11]; methotrexate [6,11]; apremilast [16]; TYK2 inhibitor (deucravacitinib) [25,26,27] | IL-23 inhibitors in stable SLE [12,13,14]; cautious hydroxychloroquine if psoriatic disease quiescent [47,51] | TNF-α inhibitors [10,18,52,53,63]; hydroxychloroquine when psoriasis/PsA active [47,51]; phototherapy in SLE [9,20] |

| Sub-group | TNF-α inhibitors | IL-17 inhibitors | IL-23 inhibitors | Ustekinumab (IL-12/23) | TYK2 inhibitor | Apremilast | Methotrexate (MTX) | Mycophenolate (MMF) | Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) | Phototherapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis + ANA+ (no lupus) | Conditional (effective but ANA rise, DIL risk) [10,18,35,36,37,38] | Preferred [40,42] | Preferred [12,13,14,43] | Conditional [39,46] | Conditional (limited data, mechanistically favorable) [25,26,27] | Preferred [16] | Conditional [6,11] | Conditional (rarely needed if no SLE) [6,11] | Conditional (if no psoriasis flare history) [47,51] | Conditional (NB-UVB only; avoid ANA high-titer/ENA+) [9,20,47] |

| Psoriasis + CLE | Avoid (CLE induction/worsening) [10,18,45,46,47,48,49] | Avoid (strong CLE risk) [28,29,30,31,32,33] | Preferred [12,13,14,43] | Conditional (neutral-safety, modest data) [39,46,48] | Conditional (promising in CLE, limited overlap data) [25,26,27] | Preferred [16] | Preferred [6,11] | Preferred if SLE/CLE-active [6,11,20] | Conditional (avoid if psoriasis flares) [47,51] | Avoid (photosensitive CLE risk) [9,20] |

| Psoriasis + SLE | Avoid [10,18,48,49,50,51,52,53] | Avoid [28,29,30,31,32,33] | Conditional (use only in stable SLE) [12,13,14] | Preferred for safety (modest efficacy) [46] | Preferred (improves SLE & CLE biology) [25,26,27] | Preferred [16] | Preferred [6,11] | Preferred [6,11] | Conditional (only if psoriasis mild, SLE-dominant) [47,51] | Avoid [9,20,47] |

| PsA + ANA+ | Avoid (autoantibody induction, DIL risk) [10,18,54,55,56,57] | Preferred [40,42] | Preferred [12,13,14,43] | Conditional [39,46] | Conditional [25,26,27] | Conditional [16] | Preferred [6,11] | Conditional [6,11] | Conditional (if PsA mild, lupus absent) [47,51] | Conditional (only if low-titer ANA, no lupus features) [9,20] |

| PsA + CLE | Avoid [10,18,45,46,47,48,49] | Avoid [28,29,30,31,32,33] | Preferred [12,13,14,43] | Conditional [39,46,48] | Conditional–Preferred (CLE benefit; limited PsA data) [25,26,27] | Conditional [16] | Preferred [6,11] | Preferred [6,11,20] | Avoid (psoriasis/PsA flare risk) [47,51] | Avoid [9,20] |

| PsA + SLE | Avoid [10,18,52,53,63] | Avoid [28,29,30,31,32,33] | Conditional (stable SLE only) [12,13,14] | Conditional [39,46,48] | Preferred (dual PsA/SLE biology) [25,26,27] | Preferred [16] | Preferred [6,11] | Preferred [6,11] | Conditional (only if PsA quiescent) [47,51] | Avoid [9,20] |

3.7. Discussion

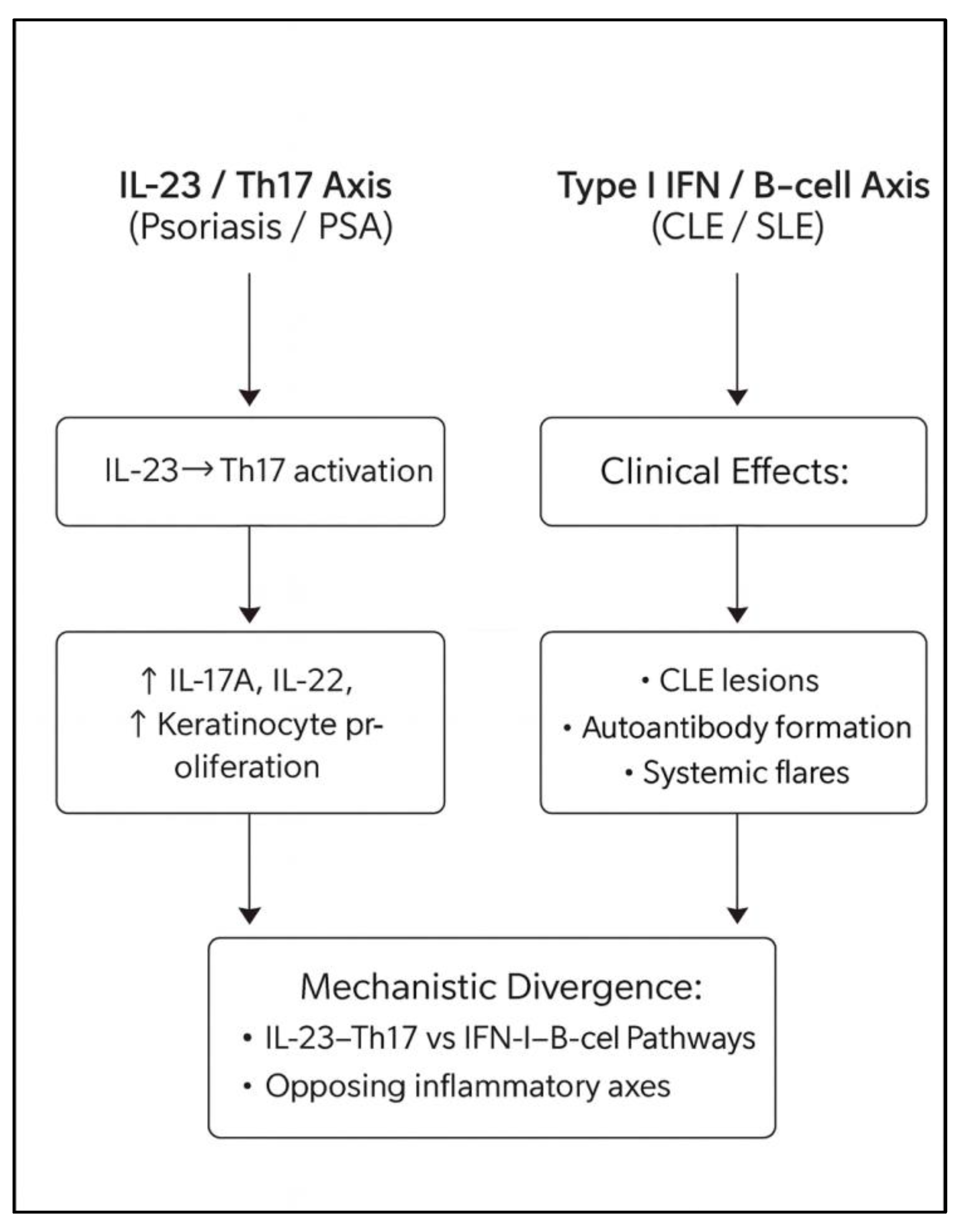

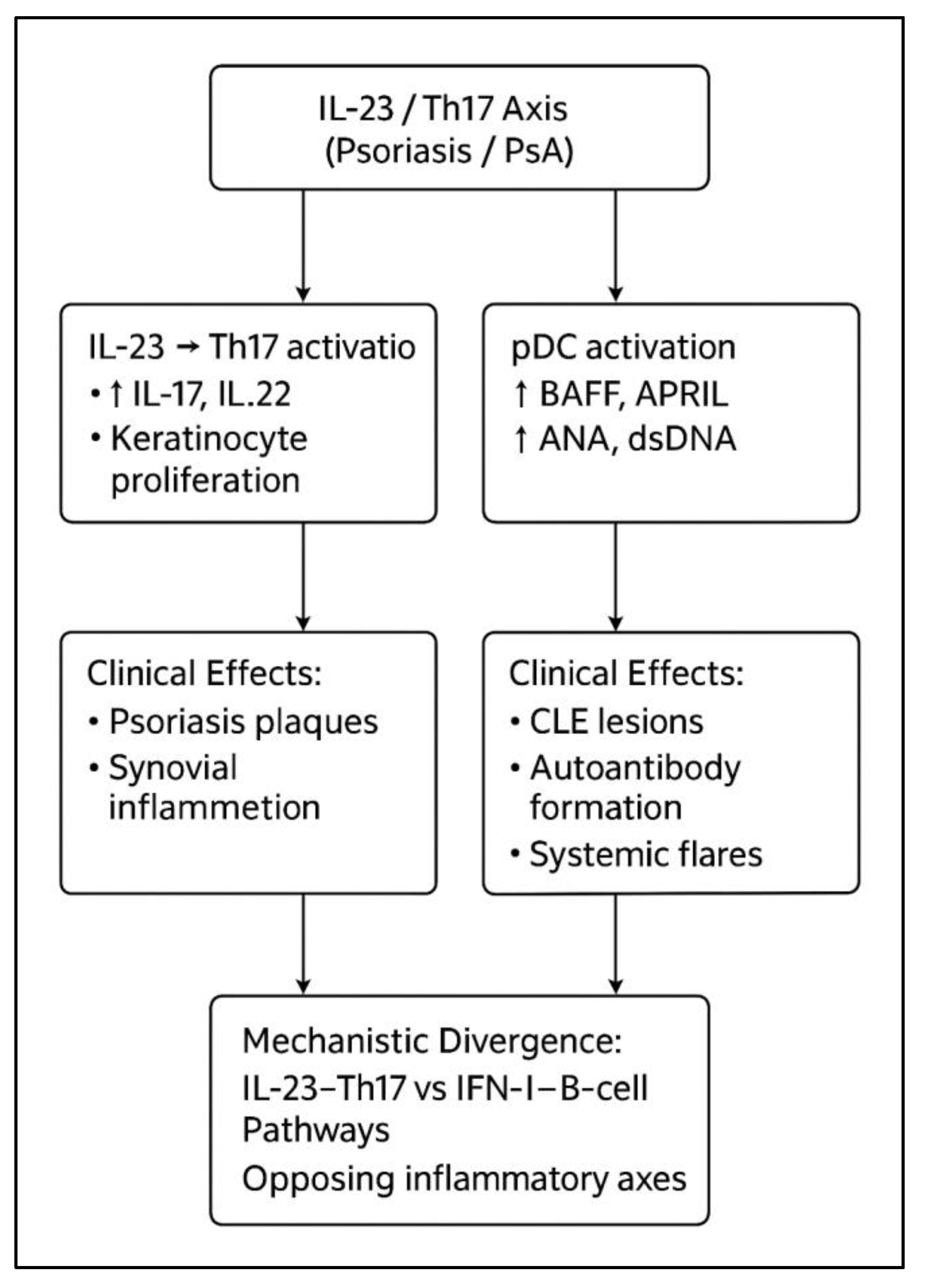

3.8. The Central Immunologic Paradox of Psoriasis–Lupus Overlap

3.9. Differential implications for SLE versus CLE, particularly DLE

3.10. The Cross-Disease Safety Advantage of IL-23 Inhibition

| Immunologic Axis / Drug Class | Primary Mediators / Targets | Dominant Disease Context | Effect on Psoriasis/PsA | Effect on CLE/SLE | Therapeutic Implications in Overlap Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th17/IL-23 Axis | IL-23, IL-17A/F, IL-22, TNF-α | Psoriasis, PsA | Central driver of keratinocyte activation and synovial inflammation [1,2,3,4,5] | Indirect, usually minor role [9,17] | Blocking this axis improves psoriatic disease; downstream risk depends on IFN-I shifts [9,12,13,14,20] |

| Type I IFN / B-cell Axis | IFN-α/β, BAFF, ANA, dsDNA, immune complexes | CLE, SLE | Can be secondarily activated but not primary driver [6,7,8,9,17] | Central to cutaneous & systemic lupus activity [6,7,8,9,17] | Therapies amplifying IFN-I or autoantibody production increase lupus risk; IFN-suppressive agents are protective [9,17,20] |

| TNF-α inhibitors | TNF-α blockade | Psoriasis, PsA, RA | Highly effective [1,2,3,4,5] | Promotes ANA ↑, dsDNA ↑, DIL, CLE flares [10,18,35,36,37,38,45,46,47,48,49,52,53] | Should be avoided in CLE/SLE or high-risk ANA+ patients despite psoriatic efficacy [10,18,35,36,37,38,45,46,47,48,49,52,53] |

| IL-17 inhibitors | IL-17A/F blockade | Psoriasis, PsA | Very strong skin/joint efficacy [2,4,40,42] | Associated with de novo or worsened SCLE/DLE [28,29,30,31,32,33] | Useful in severe psoriatic disease but risky in CLE-prone patients; avoid active DLE/SCLE [28,29,30,31,32,33] |

| IL-23 inhibitors | IL-23 p19 blockade (upstream of Th17) | Psoriasis, PsA | Excellent psoriatic control [12,13,14,43] | Neutral or potentially protective; no lupus signal to date [12,13,14,43] | Best overall safety in psoriatic–lupus overlap; preferred biologic class [12,13,14,43] |

| IL-12/23 inhibitor (ustekinumab) | p40 blockade | Psoriasis, PsA; tested in SLE | Effective in psoriasis/PsA [39] | Safe in SLE (Phase II/III) though modest efficacy [46] | Good option when IL-23 inhibitors unavailable; safe for stable SLE with psoriasis [39,46,48] |

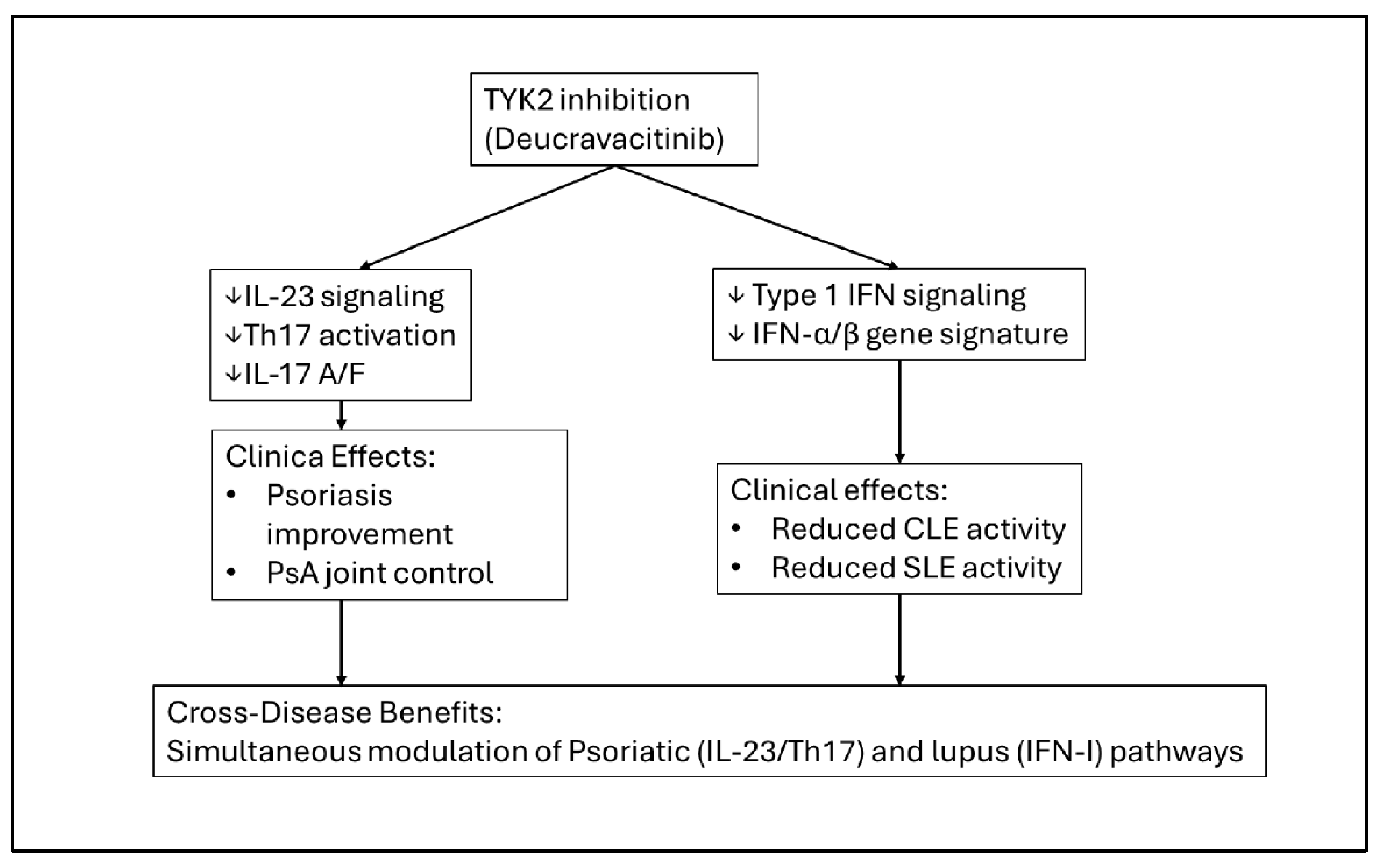

| TYK2 inhibitor (deucravacitinib) | TYK2 signaling (IL-23, IFN-I, IL-12 pathways) | Psoriasis; emerging in SLE/CLE | Effective in psoriasis & PsA [25,26,27] | Suppresses IFN-I signatures; improves CLE/SLE endpoints [25,26,27] | First cross-disease targeted agent; promising for PsO/PsA + CLE/SLE [25,26,27] |

| PDE4 inhibitor (apremilast) | cAMP-mediated cytokine modulation | Psoriasis, PsA | Moderate efficacy [16] | Neutral to slightly favorable in lupus [16] | Safe oral option in ANA+ and lupus-prone patients [16] |

| Methotrexate (MTX) | Antimetabolite; T- and B-cell modulation | Psoriasis, PsA, SLE arthritis | Good joint/skin response [6,11] | Beneficial for SLE musculoskeletal disease [6,11] | Foundational option for SLE-dominant overlap [6,11] |

| Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) | Inhibits lymphocyte proliferation | SLE, CLE | Modest effect on psoriasis/PsA [6,11] | Strongly effective in SLE/CLE [6,11,20] | First-line systemic option for SLE/CLE-dominant presentation [6,11,20] |

| Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) | TLR7/9 & IFN-I modulation | CLE, SLE | May worsen psoriasis [47,51] | Beneficial for CLE/SLE [6,11,47,51] | Mainstay for lupus; avoid in active psoriasis/PsA [47,51] |

| Phototherapy (NB-UVB/UVB) | UV-induced keratinocyte apoptosis & neo-antigen exposure | Psoriasis | Effective in psoriasis [22] | Can trigger CLE via IFN-I upregulation [9,20] | Acceptable only for low-risk ANA+ patients; contraindicated in CLE/SLE [9,20,47] |

| Therapeutic Class | Primary Drug-Induced Autoimmune Signal(s) | Strength of Evidence | Typical Clinical Phenotype | Reversibility After Drug Withdrawal | Overall Risk Rating for Drug-Induced Autoimmunity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α inhibitors | ANA seroconversion; anti-dsDNA induction; ATIL; CLE-like eruptions [10,18,35,36,37,38,45,46,47,48,49,52,53] | High – multiple cohorts, case series, pharmacovigilance [10,18,35,36,37,38,45,46,47,48,49] | Photosensitive rash; SCLE/DLE-like lesions; arthritis/serositis; ANA ± dsDNA; occasionally full SLE [45,46,47,48,49,52,53] | Usually improves/resolves after withdrawal ± steroids or HCQ [45,46,47,48,49] | High risk – avoid in CLE/SLE or strong lupus diathesis; use only exceptionally [10,18,35,36,37,38,45,46,47,48,49,52,53] |

| IL-17 inhibitors | New-onset or worsening CLE (SCLE/DLE); rare lupus-like events [28,29,30,31,32,33] | Moderate – increasing case reports and series [28,29,30,31,32,33] | Disseminated DLE/SCLE; photo-exacerbated plaques; ANA elevation with minimal systemic signs [28,29,30,31,32,33] | Improves after IL-17 withdrawal; switch to IL-23 or non-Th17 agents [28,29,30,31,32,33] | Moderate cutaneous risk – avoid active CLE/DLE; may use cautiously in stable SLE without CLE [28,29,30,31,32,33] |

| IL-23 inhibitors | Occasional ANA changes; no consistent lupus/CLE signal [12,13,14,43] | Low – pooled trials + real-world [12,13,14,43] | Isolated autoantibody changes; lupus events rare, not clearly drug-related [12,13,14] | Withdrawal usually not needed | Low risk – preferred for ANA+, CLE, stable SLE [12,13,14,43] |

| IL-12/23 inhibitor (ustekinumab) | Rare lupus-like or autoimmune phenomena; neutral in SLE trials [39,46] | Low–moderate – Phase II/III SLE + psoriasis data [39,46] | Stable SLE activity; no CLE or systemic flares [46] | Withdrawal rarely required [46] | Low–moderate risk – mechanistically neutral; reasonable for psoriasis + stable SLE [39,46,48] |

| TYK2 inhibitor (deucravacitinib) | Reduction of IFN-driven autoimmunity; improves CLE/SLE markers [25,26,27] | Emerging – early SLE/CLE trials + transcriptomics [25,26,27] | ↓ IFN signatures; improved CLE/SLE scores; no de novo lupus [25,26,27] | Not typically associated with drug-induced autoimmunity | Low / potentially protective – attractive for PsO/PsA + CLE/SLE [25,26,27] |

| PDE4 inhibitor (apremilast) | Minimal autoimmunity signal; rare nonspecific events [16] | Low – extensive psoriasis/PsA use; few lupus reports [16] | Mild, nonspecific immune findings; no ANA/CLE/SLE pattern [16] | Generally reversible; therapy often continued | Very low risk – safe oral option for ANA+ & lupus-prone pts [16] |

| Methotrexate (MTX) | No DIL signature; may reduce SLE activity [6,11] | Low – long clinical use [6,11] | Improves joint/skin + systemic inflammation [6,11] | N/A – not a lupus inducer | Low risk – foundational in SLE-dominant PsA/PsO [6,11] |

| Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) | Treats SLE/CLE; no DIL [6,11,20] | Low – standard SLE/CLE therapy [6,11] | Decreases CLE lesions + SLE activity [6,11,20] | N/A – therapeutic rather than inductive | Very low / protective – preferred in SLE/CLE-dominant cases [6,11,20] |

| Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) | Psoriasis flares; paradoxical psoriatic autoimmunity [47,51] | Moderate – multiple psoriatic flare reports [47,51] | New-onset psoriasis or worsening existing disease; usually no lupus induction [47,51] | Improves after HCQ withdrawal | Low lupus risk, moderate psoriasis risk – avoid in active psoriasis/PsA [47,51] |

| Rituximab | SLE improvement; paradoxical psoriasis induction [59] | Moderate – case reports + series [59] | De novo psoriasis or flares; SLE improves [59] | Psoriasis improves after rituximab withdrawal [59] | Low lupus risk, moderate psoriasis risk – use cautiously in PsO-risk patients [59] |

| Phototherapy (NB-UVB/UVB) | Photo-induced CLE/DLE/SCLE; IFN-signature amplification [9,20,47] | Moderate – well-documented UV-triggered CLE [9,20] | New or worsening CLE in sun-exposed areas; no systemic flare necessarily [9,20,47] | Improves after cessation + photoprotection [9,20] | Moderate cutaneous autoimmunity risk – avoid or minimize in ANA-high, ENA+, CLE-prone pts [9,20,47] |

3.11. IL-17 Inhibitors: High Efficacy but Distinct Cutaneous Lupus Risk

3.12. TNF-α Inhibitors: Strongest Evidence for Lupus Induction and Autoantibody Conversion

3.13. Ustekinumab (IL-12/23): Stable Safety Despite Mixed SLE Efficacy

3.14. TYK2 Inhibition: A Mechanistically Bidirectional Therapy

| Agent | Study / Population | Design & Sample | Key Efficacy Findings in SLE/CLE | Safety Signals | Implications for Psoriasis/PsA with Lupus-Spectrum Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ustekinumab (IL-12/23 inhibitor) | Phase II SLE trial [46] | Randomized, placebo-controlled; moderate-to-severe SLE | Improved SRI-4 responses vs placebo; benefit in musculoskeletal & mucocutaneous domains [46] | No increase in lupus flares; no DIL; no new safety concerns [46] | Demonstrates biologic activity in SLE with reassuring safety, supporting use in psoriasis/PsA with stable or mild SLE when IL-23 inhibitors are unavailable [39,46,48] |

| Phase III SLE trial [46] | Randomized, placebo-controlled; multicenter SLE cohort | Failed primary BICLA endpoint; modest improvement in secondary outcomes (e.g., SRI-6) [46] | Safety similar to placebo; no lupus activation [46] | Confirms stable safety but inconsistent SLE efficacy; ustekinumab can be considered “neutral-safe” in overlap disease, not a primary lupus therapy [46,48] | |

| Case reports / small CLE series [46,48] | SCLE/DLE patients treated off-label | Variable but sometimes favorable CLE lesion control in refractory cases [46,48] | No CLE worsening; no systemic lupus induction [46] | Suggests ustekinumab is unlikely to exacerbate CLE in psoriatic patients; evidence limited, non-randomized [46,48] | |

| Deucravacitinib (TYK2 inhibitor) | Phase II SLE trial [25,26,27] | Randomized, placebo-controlled; active SLE (multi-organ involvement) | Improved PROs and global disease activity; reduction in IFN-I–driven gene signatures [25,26,27] | No DIL signal; no major flares; well tolerated [25,26,27] | Provides proof-of-concept that TYK2 targeting improves SLE activity while modulating IFN-I pathways—highly relevant to overlap patients [25,26,27] |

| CLE transcriptomic study [26] | CLE patients; mechanistic/transcriptomic | Decreased IFN-I–regulated transcripts; reduced CLE inflammatory signature [26] | No new safety concerns [26] | Indicates direct CLE benefit, supporting use when CLE coexists with psoriasis/PsA [26] | |

| Real-world PsO + PsA + SLE case [25] | Single-patient, refractory overlap treated with deucravacitinib + MMF + HCQ | Concurrent improvement in psoriasis, PsA, SLE; steroid-sparing [25] | No lupus activation; no psoriasis flare [25] | First real-world evidence of cross-disease control → TYK2 inhibition as important systemic option [25] | |

| Psoriasis Phase III trials (contextual) [25,26,27] | Phase III PsO RCTs | High PASI-75/90 rates; durable efficacy [25,26,27] | No CLE/SLE signal in PsO trials [25,26,27] | Confirms strong psoriatic efficacy with safety compatible for lupus-prone individuals; supports cautious use pending more overlap studies [25,26,27] |

3.15. Phototherapy: A Reassessment in ANA-Positive and CLE-Prone Disease

| Clinical Setting | Phototherapy Modality | Psoriasis/PsA Efficacy | Lupus / Autoimmunity Risk | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis / PsA, ANA-negative | NB-UVB, BB-UVB | High efficacy for plaque psoriasis; useful for PsA with skin-dominant disease [22] | No specific lupus risk | Standard indication; may be used freely if no lupus features or autoimmune history |

| Psoriasis / PsA, low-titer ANA+ (no ENA, no lupus symptoms) | NB-UVB preferred; avoid high cumulative doses | Good psoriasis control; may reduce systemic drug burden [22] | Theoretical IFN-I upregulation & autoantibody evolution, but clinical risk appears low [9,20] | Acceptable with caution: use NB-UVB, limit exposure, monitor for CLE-like lesions or systemic symptoms [9,20] |

| Psoriasis / PsA, high-titer ANA+ or ENA+; no overt lupus | NB-UVB only in exceptional cases; avoid PUVA/high-dose UVB | Effective for psoriasis, but safer systemic alternatives exist [6,11] | Elevated risk of UV-provoked autoimmunity; UV can trigger CLE-like changes & IFN signature [9,20,47] | Use only when systemic options are contraindicated; short courses; close skin/serologic monitoring with rheumatology input [9,20,47] |

| Psoriasis + CLE (SCLE/DLE) | NB-UVB/BB-UVB; PUVA | May improve psoriasis, but CLE is highly photosensitive [9,20,47] | High risk of CLE flare, new lesions, increased IFN-I activity [9,20] | Generally not recommended; prefer IL-23 inhibitors, MMF, MTX, apremilast [6,11,12,13,14,16]; strict photoprotection required |

| PsA + CLE | NB-UVB/BB-UVB; PUVA | Limited data; psoriasis/PsA may improve | Same high risk of CLE exacerbation [9,20,47] | Avoid phototherapy; prioritize MMF, MTX, IL-23 inhibitors [6,11,12,13,14] |

| Psoriasis / PsA + SLE (± CLE) | NB-UVB/BB-UVB; PUVA | May help psoriasis; no benefit for SLE [22] | Well-documented photosensitive SLE flares; CLE flares; UV is a classic trigger [9,20,47] | Contraindicated in most cases; avoid phototherapy and ensure strict photoprotection [9,20,47] |

| Isolated CLE / SLE without psoriasis/PsA | ANY UV-based therapy | Not indicated for lupus [6,11] | High risk of cutaneous + systemic SLE/CLE flares [9,20,47] | Not appropriate; rely on HCQ, MMF, MTX, biologics with IFN-safe profiles [6,11,20] |

3.16. Treatment Strategy by Disease Combination

3.17. The Need for Prospective and Mechanistic Trials

3.18. Clinical Implications

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| ANA | Antinuclear antibody |

| anti-dsDNA | Anti–double-stranded DNA antibody |

| ATIL | Anti–TNF–induced lupus |

| CLE | Cutaneous lupus erythematosus |

| DIL | Drug-induced lupus |

| DLE | Discoid lupus erythematosus |

| ENA | Extractable nuclear antigen |

| HCQ | Hydroxychloroquine |

| IFN-I | Type I interferon |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IL-17i | IL-17 inhibitor |

| IL-23i | IL-23 inhibitor |

| IL-12/23i | IL-12/23 inhibitor (ustekinumab) |

| MMF | Mycophenolate mofetil |

| MTX | Methotrexate |

| NB-UVB | Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy |

| PsA | Psoriatic arthritis |

| PsO | Psoriasis |

| PUVA | Psoralen plus ultraviolet A therapy |

| pDC | Plasmacytoid |

Appendix A

| Section & Topic | Item # | PRISMA 2020 Checklist Item | Location in Manuscript |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Title page |

| ABSTRACT | 2 | PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | Abstract |

| INTRODUCTION | 3 | Rationale: Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | Section 1 |

| 4 | Objectives: Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) the review addresses. | Section 1 (final paragraph) | |

| METHODS | 5 | Eligibility criteria: Specify inclusion and exclusion criteria and how studies were grouped. | Section 2.2 |

| 6 | Information sources: List all databases, registers, and other sources; include search dates. | Section 2.3 | |

| 7 | Search strategy: Present full search strategies for all databases and registers. | Supplementary Table S1 | |

| 8 | Selection process: Describe methods used to assess study eligibility, including reviewers and automation tools. | Section 2.1 | |

| 9 | Data collection process: Describe methods used to collect data from included studies. | Section 2.5 | |

| 10a | Data items (outcomes): List and define primary/secondary outcomes. | Section 2.5 | |

| 10b | Data items (variables): List and define all other variables (e.g., participant characteristics). | Section 2.5 | |

| 11 | Study risk of bias assessment: Describe tools and methods used. | Section 2.6 | |

| 12 | Effect measures: Specify effect measures for each outcome. | Not applicable (narrative review) | |

| 13a | Synthesis methods: Eligibility for synthesis. | Section 2.7 | |

| 13b | Synthesis methods: Methods for data preparation. | Section 2.7 | |

| 13c | Synthesis methods: Methods for tabulation or visual display. | Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9; Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 | |

| 13d | Synthesis methods: Methods used to synthesize results. | Narrative synthesis only | |

| 13e | Exploration of heterogeneity. | Not applicable | |

| 13f | Sensitivity analyses. | Not applicable | |

| 14 | Reporting bias assessment. | Section 2.6 | |

| RESULTS | 15 | Study selection: Provide screening numbers and reasons for exclusions; include flow diagram. | Section 3.1; Figure 1 |

| 16a | Study characteristics: Present characteristics of included studies. | Table 1 | |

| 16b | Excluded studies with reasons. | Section 3.1 | |

| 17 | Risk of bias in included studies. | Section 3.x; Table 9 | |

| 18 | Results of individual studies. | Section 3; Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 | |

| 19 | Results of syntheses. | Sections 3.2–3.18 | |

| 20 | Reporting biases. | Section 3.x | |

| DISCUSSION | 23a | Interpretation of results in context of other evidence. | Section 3 |

| 23b | Limitations of included evidence. | Section 3 | |

| 23c | Limitations of review processes. | Section 3.9 | |

| 23d | Implications for practice, policy, and future research. | Section 4 | |

| OTHER INFORMATION | 24 | Registration and protocol. | PROSPERO ID |

| 25 | Support and funding. | Funding section | |

| 26 | Competing interests. | COI section | |

| 27 | Availability of data, code, and materials. | Data Availability section |

Appendix B. PRISMA 2020 Abstract Checklist

| Item # | PRISMA for Abstracts Checklist Item (Full Wording) | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Abstract |

| 2 | Provide an explicit statement of the main objective(s) or question(s). | Abstract |

| 3 | Eligibility criteria: Specify inclusion and exclusion criteria. | Abstract |

| 4 | Information sources: Specify the databases and dates of searches. | Abstract |

| 5 | Risk of bias: Indicate methods used to assess risk of bias. | Abstract |

| 6 | Synthesis of results: Indicate methods used for synthesizing results. | Abstract |

| 7 | Included studies: Report the number and type of included studies and participants. | Abstract |

| 8 | Results: Present summary of key findings. | Abstract |

| 9 | Limitations: Report limitations of the evidence and/or review. | Abstract |

| 10 | Interpretation: Provide general interpretation and implications. | Abstract |

| 11 | Funding: Specify primary source of funding. | Abstract |

| 12 | Registration: Provide registration info (e.g., PROSPERO ID). | Abstract |

References

- Christophers, E. Psoriasis--epidemiology and clinical spectrum. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001, 26, 314–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mease, P.J.; McInnes, I.B.; Kirkham, B.; Kavanaugh, A.; Rahman, P.; van der Heijde, D.; et al. Secukinumab Inhibition of Interleukin-17A in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373, 1329–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebwohl, M.; Strober, B.; Menter, A.; Gordon, K.; Weglowska, J.; Puig, L.; et al. Phase 3 Studies Comparing Brodalumab with Ustekinumab in Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373, 1318–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoreschi, K.; Balato, A.; Enerbäck, C.; Sabat, R. Therapeutics targeting the IL-23 and IL-17 pathway in psoriasis. Lancet. 2021, 397, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogdie, A.; Weiss, P. The Epidemiology of Psoriatic Arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015, 41, 545–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dubois’ Lupus Erythematosus and Related Syndromes., 9th ed.; Wallace, DJ, Hahn, BH, Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Petri, M.; Orbai, A.M.; Alarcón, G.S.; Gordon, C.; Merrill, J.T.; Fortin, P.R.; et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 64, 2677–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Doria, A.; Zen, M.; Canova, M.; Bettio, S.; Bassi, N.; Nalotto, L.; et al. SLE diagnosis and treatment: when early is early. Autoimmun Rev. 2010, 10, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, J. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: new insights into pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019, 15, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Casals, M.; Brito-Zerón, P.; Soto, M.J.; Cuadrado, M.J.; Khamashta, M.A. Autoimmune diseases induced by TNF-targeted therapies. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008, 22, 847–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benucci, M.; Gobbi, F.L.; Del Rosso, A.; Cesaretti, S.; Niccoli, L.; Cantini, F. Disease activity and antinucleosome antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand J Rheumatol. 2003, 32, 42–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papp, K.A.; Blauvelt, A.; Bukhalo, M.; Gooderham, M.; Krueger, J.G.; Lacour, J.P.; et al. Risankizumab versus Ustekinumab for Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2017, 376, 1551–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blauvelt, A.; Papp, K.A.; Griffiths, C.E.; Randazzo, B.; Wasfi, Y.; Shen, Y.K.; et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: Results from the phase III, double-blinded, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017, 76, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menter, A.; Strober, B.E.; Kaplan, D.H.; Kivelevitch, D.; Prater, E.F.; Stoff, B.; et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019, 80, 1029–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, D.J.; Gudsoorkar, V.S.; Weisman, M.H.; Venuturupalli, S.R. New insights into mechanisms of therapeutic effects of antimalarial agents in SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012, 8, 522–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanaugh, A.; Mease, P.J.; Gomez-Reino, J.J.; Adebajo, A.O.; Wollenhaupt, J.; Gladman, D.D.; et al. Treatment of psoriatic arthritis in a phase 3 randomised, placebo-controlled trial with apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014, 73, 1020–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaul, A.; Gordon, C.; Crow, M.K.; Touma, Z.; Urowitz, M.B.; van Vollenhoven, R.; et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016, 2, 16039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Sawalha, A.H. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus: an update on drugs and mechanisms. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018, 30, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mease, P.J.; Ory, P.; Sharp, J.T.; Ritchlin, C.T.; Van den Bosch, F.; Wellborne, F.; et al. Adalimumab for long-term treatment of psoriatic arthritis: 2-year data from the Adalimumab Effectiveness in Psoriatic Arthritis Trial (ADEPT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2009, 68, 702–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Teboul, A.; Arnaud, L.; Chasset, F. Recent findings about antimalarials in cutaneous lupus erythematosus: What dermatologists should know. J Dermatol 2024, 51, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aringer, M.; Costenbader, K.; Daikh, D.; Brinks, R.; Mosca, M.; Ramsey-Goldman, R.; et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019, 78, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalb, R.E.; Fiorentino, D.F.; Lebwohl, M.G.; Toole, J.; Poulin, Y.; Cohen, A.D.; et al. Risk of Serious Infection With Biologic and Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis: Results From the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015, 151, 961–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, Z.; Chen, F.; Wu, H.; Peng, C.; et al. Prioritizing drug targets in systemic lupus erythematosus from a genetic perspective: a druggable genome-wide Mendelian randomization study. Clin Rheumatol. 2024, 43, 2843–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lorenzo-Vizcaya, A.; Isenberg, D.A. Clinical trials in systemic lupus erythematosus: the dilemma-Why have phase III trials failed to confirm the promising results of phase II trials? Ann Rheum Dis. 2023, 82, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gewiss, C.; Steinmetz, O.M.; Roth, L.; Augustin, M.; Ben-Anaya, N. Effective management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus using deucravacitinib, mycophenolate mofetil and hydroxychloroquine. Skin Health Dis. 2025, 5, 403–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wasserer, S.; Seiringer, P.; Kurzen, N.; Jargosch, M.; Eigemann, J.; Aydin, G.; et al. Tyrosine kinase 2 inhibition improves clinical and molecular hallmarks in subtypes of cutaneous lupus. British Journal of Dermatology 2025, 193, 1192–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosca, M.; Arnaud, L.; Askanase, A.; Hobar, C.; Becker, B.; Singhal, S.; et al. Deucravacitinib, an oral, selective, allosteric, tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor, in patients with active SLE: efficacy on patient-reported outcomes in a phase II randomised trial. Lupus Science & Medicine 2025, 12, e001517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Liu, D.; Tu, C.; Yan, S.; Liu, Y. Secukinumab-Aggravated Disseminated Discoid Lupus Erythematosus Misdiagnosed as Psoriasis. Cureus. 2024, 16, e72698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hsieh, C.Y.; Tsai, T.F. Aggravation of discoid lupus erythematosus in a patient with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis during treatment of secukinumab: A case report and review of literature. Lupus. 2022, 31, 891–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaler, J.; Kaeley, G.S. Secukinumab-Induced Lupus Erythematosus: A Case Report and Literature Review. J Clin Rheumatol. 2021, 27, S753–S754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conforti, C.; Retrosi, C.; Giuffrida, R.; Vezzoni, R.; Currado, D.; Navarini, L.; et al. Secukinumab-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Ther. 2020, 33, e13417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzimichail, G.; Zillikens, D.; Thaçi, D. Secukinumab-induced chronic discoid lupus erythematosus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020, 6, 362–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ávila-Ribeiro, P.; Lopes, A.R.; Martins-Martinho, J.; Nogueira, E.; Antunes, J.; Romeu, J.C.; et al. Secukinumab-induced systemic lupus erythematosus in psoriatic arthritis. In ARP Rheumatol.; English, 2023; Volume 2, pp. 265–268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.H.; Cons Molina, F.; Aroca, G.; Tektonidou, M.G.; Mathur, A.; Tangadpalli, R.; et al. Secukinumab in active lupus nephritis: Results from phase III, randomised, placebo-controlled study (SELUNE) and open-label extension study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2025, keaf536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pink, A.E.; Fonia, A.; Allen, M.H.; Smith, C.H.; Barker, J.N. Antinuclear antibodies associate with loss of response to antitumour necrosis factor-alpha therapy in psoriasis: a retrospective, observational study. Br J Dermatol. 2010, 162, 780–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirowska, M.M.; Goździalska, A.; Lipko-Godlewska, S.; Obtułowicz, A.; Sułowicz, J.; Podolec, K.; et al. Autoimmunogenicity during anti-TNF therapy in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015, 32, 250–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bardazzi, F.; Odorici, G.; Virdi, A.; Antonucci, V.A.; Tengattini, V.; Patrizi, A.; et al. Autoantibodies in psoriatic patients treated with anti-TNF-α therapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014, 12, 401–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oter-López, B.; Llamas-Velasco, M.; Sánchez-Pérez, J.; Dauden, E. Induction of Autoantibodies and Autoimmune Diseases in Patients with Psoriasis Receiving Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors. Actas Dermosifiliogr. English, Spanish. 2017, 108, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanaba, K.; Umezawa, Y.; Honda, H.; Sato, R.; Chiba, M.; Kikuchi, S.; et al. Antinuclear antibody formation following administration of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents in Japanese patients with psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2016, 43, 443–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, M.; Endo, C.; Naka, Y.; Fukuya, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Kawashima, M.; et al. Increase in antinuclear antibody levels through biologic treatment for psoriasis. J Dermatol 2019, 46, e50–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlu, Ö.; Çetinkaya, P.; Şahin, T.; Ekşioğlu, H.M. The Effect of Biological Agents on Antinuclear Antibody Status in Patients with Psoriasis: A Single-Center Study. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020, 11, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sugiura, R.; Terui, H.; Shimada-Omori, R.; Yamazaki, E.; Tsuchiyama, K.; Takahashi, T.; et al. Biologics modulate antinuclear antibodies, immunoglobulin E, and eosinophil counts in psoriasis patients. J Dermatol 2021, 48, 1739–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, S.; Ozaki, S.; Ichiyama, S.; Ito, M.; Hoashi, T.; Kanda, N.; et al. Change in Antinuclear Antibody Titers during Biologic Treatment for Psoriasis. J Nippon Med Sch. 2023, 90, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staniszewska, I.; Mądrzak, L.; Piekarczyk, H.; Baran, M.; Kalińska-Bienias, A. A Systematic Review of Case Reports on the Co-occurrence of Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus and Psoriasis. Dermatol Rev/Przegl Dermatol. 2025, 112, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Arpa, M.; Flores-Terry, M.A.; Ramos-Rodríguez, C.; Franco-Muñoz, M.; González-Ruiz, L.; Ramírez-Huaranga, M.A. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus, morphea profunda and psoriasis: A case report. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed). 2020, 16, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, A.; Ali-Shaw, T.; Strober, B.E.; Franks, A.G., Jr. Successful treatment of subacute lupus erythematosus with ustekinumab. Arch Dermatol. 2011, 147, 896–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdeva, M.; Mufti, A.; Maliyar, K.; Lytvyn, Y.; Yeung, J. Hydroxychloroquine effects on psoriasis: A systematic review and a cautionary note for COVID-19 treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020, 83, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Prieto-Barrios, M.; Castellanos-González, M.; Velasco-Tamariz, V.; Burillo-Martínez, S.; Morales-Raya, C.; Ortiz-Romero, P.; et al. Two poles of the Th 17-cell-mediated disease spectrum: Analysis of a case series of 21 patients with concomitant lupus erythematosus and psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017, 31, e233–e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalla, M.J.; Muller, S.A. The coexistence of psoriasis with lupus erythematosus and other photosensitive disorders. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1996, 195, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hays, S.B.; Camisa, C.; Luzar, M.J. The coexistence of systemic lupus erythematosus and psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984, 10, 619–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tselios, K.; Yap, K.S.; Pakchotanon, R.; Polachek, A.; Su, J.; Urowitz, M.B.; et al. Psoriasis in systemic lupus erythematosus: a single-center experience. Clin Rheumatol. 2017, 36, 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Abdullah, S.; Abdulhameed, Y.; Elbadawi, F. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Psoriasis Overlap: A Case Series. Cureus 2025, 17, e84760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Walhelm, T.; Parodis, I.; Enerbäck, C.; Arkema, E.; Sjöwall, C. Comorbid psoriasis in systemic lupus erythematosus: a cohort study from a tertiary referral centre and the National Patient Register in Sweden. Lupus Sci Med. 2025, 12, e001504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Viana, V.S.; de Carvalho, J.F.; de Moraes, J.C.; Saad, C.G.; Ribeiro, A.C.; Gonçalves, C.; et al. Autoantibodies in patients with psoriatic arthritis on anti-TNFα therapy. Rev Bras Reumatol. English, Portuguese. 2010, 50, 225–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.R.; Schentag, C.T.; Gladman, D.D. Autoantibodies in biological agent naive patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005, 64, 770–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Silvy, F.; Bertin, D.; Bardin, N.; Auger, I.; Guzian, M.C.; Mattei, J.P.; et al. Antinuclear Antibodies in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis Treated or Not with Biologics. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0134218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kara, M.; Alp, G. Antinuclear Antibody Status and Effect of Biological Therapy in Psoriatic Arthritis Patients: A Single-Center Study. Medical Journal of İzmir Hospital 2025, 29, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Eibl, J.; Klotz, W.; Herold, M. AB0277 Antinuclear antibodies in patients with tnf- inhibitors. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2013, 72, A871. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003496724471598. [CrossRef]

- Wohl, Y.; Brenner, S. Cutaneous LE or psoriasis: a tricky differential diagnosis. Lupus. 2004, 13, 72–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walz LeBlanc, B.A.; Gladman, D.D.; Urowitz, M.B. Serologically active clinically quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus--predictors of clinical flares. J Rheumatol. 1994, 21, 2239–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Avriel, A.; Zeller, L.; Flusser, D.; Abu Shakra, M.; Halevy, S.; Sukenik, S. Coexistence of psoriatic arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Isr Med Assoc J. 2007, 9, 48–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bonilla, E.; Shadakshari, A.; Perl, A. Association of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Orthop Med. 2016, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkus, D.; Gazitt, T.; Cohen, A.D.; Feldhamer, I.; Lavi, I.; Haddad, A.; et al. Increased Prevalence of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Comorbidity in Patients With Psoriatic Arthritis: A Population-based Case-control Study. J Rheumatol. 2021, 48, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Aizaki, Y.; Yoshida, Y.; Mimura, T. Treatment of psoriatic arthritis complicated by systemic lupus erythematosus with the IL-17 blocker secukinumab and an analysis of the serum cytokine profile. Mod Rheumatol Case Rep. 2020, 4, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venetsanopoulou, A.I.; Katsigianni, I.; Skouvaklidou, E.; Vounotrypidis, P.; Voulgari, P.V. Uncommon Coexistence of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Psoriatic Arthritis: A Case-Based Review. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2025, 21, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkus, D.; Gazitt, T.; Cohen, A.D.; Feldhamer, I.; Lavi, I.; Haddad, A.; et al. Increased Prevalence of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Comorbidity in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis: A Population-Based Case–Control Study. J. Rheumatol. 2021, 48, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, K.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Chen, T.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; et al. Causal associations between both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and multiple autoimmune diseases: a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front Immunol. 2024, 15, 1422626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fijałkowska, A.; Wojtania, J.; Woźniacka, A.; Robak, E. Psoriasis and Lupus Erythematosus-Similarities and Differences between Two Autoimmune Diseases. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tsai, T.F.; Wang, T.S.; Hung, S.T.; Tsai, P.I.; Schenkel, B.; Zhang, M.; et al. Epidemiology and comorbidities of psoriasis patients in a national database in Taiwan. J Dermatol Sci. 2011, 63, 40–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Fits, L.; Mourits, S.; Voerman, J.S.; Kant, M.; Boon, L.; Laman, J.D.; et al. Imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice is mediated via the IL-23/IL-17 axis. J Immunol. 2009, 182, 5836–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovd, A.-M.; Kanapathippillai, P.; Ursvik, A.; Skagen, T.; Figenschau, S.; Bjørlo, I.E.; et al. Imiquimod-induced onset of disease in lupus-prone nzb/w f1 mice. The Journal of Rheumatology 2025, 52, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.D.; Cheng, H.; Wang, Z.X.; Zhang, A.P.; Wang, P.G.; Xu, J.H.; et al. Association analyses identify six new psoriasis susceptibility loci in the Chinese population. Nat Genet. 2010, 42, 1005–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).