1. Introduction

Plague is a disease of wild rodents, which only accidentally crosses over to humans [

1]. However, these accidents were the cause of at least three known pandemics and cost humanity more than 200 million lives [

2,

3]. The World Health Organization (WHO), a key player in pandemic preparedness and response [

4], has released a list of prioritized pathogens posing the greatest emerging epidemic threats. WHO draws the attention of the global community to the need to accelerate research in the development and clinical trials of vaccines against these priority pathogens [

5,

6]. This list contains five bacterial pathogens, including

Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of the plague. Although the success in the fight against the third plague pandemic was largely due to the application of the first generation of plague vaccines (e.g., a killed plague vaccine developed in 1897 by Waldemar Mordecai Haffkine (1860-1930)) [

7,

8] there is still no generally accepted plague vaccine that meets all WHO requirements [

9]. A number of researchers continue to develop plague vaccines using various technological platforms [

10,

11]. Advances in molecular bacteriology have made it possible to develop a wide range of plague vaccine candidates that appear to be superior to the first-generation vaccines

in vitro and in animal comparative studies [

12]. Recently, Roy Curtiss 3

rd's team proposed an original methodology for controlled delayed attenuation of bacterial pathogens [

13,

14,

15,

16]. This technology has been applied to

Y. pestis strain KIM5+ (subsp.

pestis bv. Medievalis) in a mouse model and has shown superiority over traditional knockout mutagenesis [

17]. However, the safety and efficacy of the strains with delayed attenuation in humans is not yet known.

Currently, ethical considerations prohibit the use of standard research methodologies like randomized controlled trials or cohort studies for evaluating plague vaccines. This is because failure to vaccinate the control group would expose its members to unacceptable risk. Therefore, the authorization of plague vaccines for use in humans should be conducted utilizing the FDA's Animal Rule [

18]. This rule facilitates the licensing of products for which traditional potency testing methodologies are deemed unethical. Specifically, the Animal Rule is applied in situations, where an infective agent exhibits extremely high pathogenicity and the rarity of the infection it causes precludes the feasibility of conducting field studies (21 CFR 601.91 Subpart H, “Approval of Biological Products When Human Efficacy Studies Are Not Ethical or Feasible”) [

19]. One of the four essential requirements for the application of the FDA Animal Rule is that the vaccine's effects (survival or prevention of serious disease) must be observed in more than one animal species, which is expected to be more likely to reflect human responses.

The aim of this study was to verify the vaccine properties of the PBAD-crp mutant generated on the basis of a phylogenetically different parent strain and to evaluate its properties not only in mice but also in guinea pigs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in

Table 1.

Escherichia coli DH5α was used for plasmid propagation.

Y. pestis cells were grown routinely at 28 °C in BHI, HiMedia, India) or on BHI agar at pH 7.2.

E. coli cells were grown routinely at 37 °C in Luria Bertani (LB) broth or on agar plates at pH 7.2. Ampicillin (100 µg/mL, Amp), chloramphenicol (20 µg/mL, Cm), polymyxin B (50 μg/mL, Pol), L-arabinose (200 µg/mL, Ara) were supplemented as appropriate. BHI agar containing 10% sucrose was used for

sacB-based counterselection in the allelic exchange experiments. MacConkey agar with 0.5% maltose was used to indicate sugar fermentation and

crp gene expression.

2.2. Animals

Six-week-old outbred mice (Lab of Biomodels breeding unit, SCRAMB, Moscow Region, Russia) and four-week-old guinea pigs («Andreevka» branch of the Scientific Center of Biomedical Technologies of the Federal Medical and Biological Agency of Russia) were used in all studies. All animal experiments were approved by the State Research Center for Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology Bioethics Committee (Permit No: VP-2025/1 on 30/04/2025) and were performed in compliance with the NIH Animal Welfare Insurance #A5476-01 issued on 02/07/2007, and the European Union guidelines and regulations on handling, care and protection of Laboratory Animals (

https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/chemicals/animals-science_en (accessed on 18 November 2025).

2.3. Construction of the Plasmids

The primers used in this work are listed in

Table 2.

A primer set of Crp-NdeI/Crp-XhoI was used for amplifying the gene sequence of crp. The resulting PCR product was digested with NdeI and XhoI and ligated with plasmid pET-24b(+) digested with the same restriction enzymes to construct plasmid pET24-crp. E. coli BL21(DE3) was transformed with the plasmid pET24-crp.

Primer sets of Crp-HindIII/Crp-SphI and Crp-XbaI/Crp-SalI were used for amplifying URcrp (upstream region gene sequence of crp, from −664 to −110 bp) and the gene sequence of crp with the Shine-Dalgarno sequence, from -36 to +633 bp, respectively. A primer set of Pbad-SphI/Pbad-XbaI was used for amplifying the araC PBAD promoter from strain E. coli DH5α. The resulting PCR products were digested with appropriate restriction enzymes and ligated with pUC57 digested with HindIII and SalI to construct the plasmid pUC57-URcrp-araC Pbad-crp.

A primer set of Lt0-SphIF/Lt0-SphIR was used for amplifying the transcription terminator t0 from bacteriophage λ (Lt0TT). The resulting PCR product was digested with SphI and ligated with the plasmid pUC57-URcrp-araC Pbad-crp digested with the same restriction enzyme to construct the plasmid pUC57-URcrp-Lt0TT-araC Pbad-crp. The plasmid pUC57-URcrp-Lt0TT-araC Pbad-crp was digested with SmaI and ligated with the suicide vector pCVD442 digested with the same restriction enzyme to construct the plasmid pCVD442-URcrp-Lt0TT-araC Pbad-crp.

All the plasmid constructions were verified through sequencing.

2.4. Mutagenesis

The

crp gene deletion was constructed in the

Y. pestis EV strain by λRed-mediated mutagenesis [

21] and confirmed by PCR (

Table 2). The

Y. pestis EVΔ

crp::

cat DNA fragment containing the respective deletion was then subcloned into the pCVD442 plasmid [

23]. The pCVD442-Δ

crp::

cat plasmid was transferred from an

E. coli S17-1

λpir donor strain into a recipient wild type

Y. pestis strain 231 by conjugation. Elimination of the suicide vector and selection of

Y. pestis clones were performed in the presence of 5% sucrose and chloramphenicol [

23]. The resistance cassette was eliminated to produce FRT scar mutants by introducing pCP20 [

22].

The procedure for constructing the

Y. pestis 231P

BAD-

crp mutant was performed using the standard method [

23]. In brief, the suicide plasmid pCVD442-URcrp-Lt0TT-

araC P

BAD-

crp was conjugationally transferred from

E. coli S17-1 λpir to

Y. pestis 231. A single-crossover insertion strain was isolated on BHI agar plates containing ampicillin. Loss of the suicide vector after the second recombination between the homologous regions was selected using the

sacB-based sucrose sensitivity counter-selection system. The colonies were screened for Amp

S and verified by PCR using the primers Crp-KF/Crp-KR.

The isogenic pPst-plasmid-cured strain of

Y. pestis 231P

BAD-

crp(pPst¯) was generated as described earlier. It was cloned from the 231P

BAD-

crp strain after 10 serial passages caused in BHI broth media at +5 °C [

24]. Clones lacking the 9.5-kb pPst plasmid were detected by PCR and confirmed by a fibrinolysis assay [

25].

The presence of all

Y. pestis resident plasmids [

26,

27,

28,

29] was confirmed via PCR amplification.

2.5. Preparation of Crp Antiserum

Full-length His-tagged Crp was expressed from E. coli BL21(DE3)/pET24-crp and isolated by nickel chromatography. His-tagged protein was produced and used to obtain anti-protein mouse antiserum for Western blot analyses.

2.6. Animal Challenges

Y. pestis strains were grown at 28°C for 48 h on BHI plus L-arabinose (200 µg/mL), diluted to an appropriate concentration in PBS. The challenge doses were determined by serial dilutions in PBS and plating on BHI agar.

To demonstrate the loss of virulence, mice (n = 6/per group) and guinea pigs (n = 6/per group) were challenged subcutaneously (s.c.) with the 231Δcrp, 231PBAD-crp or 231PBAD-crp(pPst¯) strains. Each strain was inoculated at different 10-fold doses at 0.2 mL aliquots (102 CFU - 107 CFU per mouse, 102 - 109 CFU per guinea pig). At the same time, 4 additional groups of 6 mice or guinea pigs were used to control the virulence of the wild type Y. pestis 231. Then the animals were monitored for 28 days to assess the survival rate.

For vaccine studies, groups of 6 outbred mice or 6 guinea pigs were vaccinated via the subcutaneous (s.c. route with serial dilutions of the Y. pestis 231 strain PBAD-crp(pPst¯) or only with PBS buffer as a placebo. Blood was collected on day 28 postimmunization for antibody measurement. On day 30, animals were injected s.c. with 200 LD100 (400 CFU for mice, 6 × 103 CFU for guinea pigs) of the wild-type Y. pestis strain 231. All animals were observed over a 30-day period.

2.7. ELISA

ELISA was used to assay serum IgG antibodies against recombinant LcrV and F1 proteins and

Y. pestis 231 whole-cell lysate (YPL) [

30]. Polystyrene 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates (Dynatech Laboratories Inc., Chantilly, VA, USA) were coated with 1 μg/well recombinant protein or 0.5 μg/well YPL in 0.3 N sodium carbonate buffer [pH 9.6]. The procedures were the same as those described previously [

31].

2.8. In Vivo Cytokine Analysis

Outbred mice and guinea pigs were inoculated s.c. with 104 CFU of Y. pestis 231(PBAD-crp)/pPst¯. A group of uninfected mice served as the negative control (0 day). Samples were taken from mice inoculated s.c. on days 2, 4, and 6 postinoculation. The sera were filtered through 0.22-μm syringe filters and cultured on BHI plates to confirm their sterility. The levels of cytokines were measured using an ELISA with Guinea pig Interferon-γ ELISA Kit (#EGP0017), Guinea pig TNF-α ELISA Kit (#EGP0049), Mouse IFN-γ ELISA Kit (#EM0093), and Mouse TNF-α ELISA Kit (#EM0183), all according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Wuhan Fine Biotech Co., Ltd., China).

2.9. Statistics

The LD

50 and 95% confidence intervals of the isogenic

Y. pestis strains for mice and guinea pigs were calculated using the Kärber method [

23]. T-test of unpaired samples, ANOVA and Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test were used. A p-value below 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

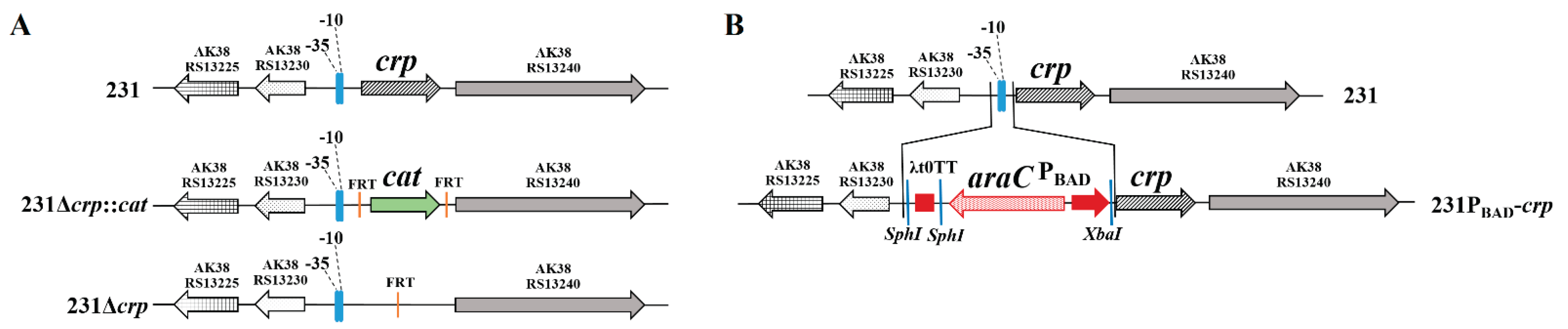

3.1. Construction of the Deletion-Insertion Mutation to Achieve Regulated Delayed Attenuation

The Δ

crp mutant of

Y. pestis strain 231 was generated by replacing the

crp gene with the chloramphenicol resistance gene

cat and curing the resistance cassette to produce a FRT scar (

Figure 1A). The P

BAD crp mutant of

Y. pestis strain 231 was constructed by replacing 74 nucleotides containing the

crp gene promoter region from -110 to -37 bp with the transcription terminator t0 from bacteriophage λ (Lt0TT) and the

araC P

BAD promoter from

E. coli strain DH5α (

Figure 1B). The deletion of the

crp gene from wild type 231 and the promoter replacement with P

BAD-

crp were confirmed by PCR analysis using specific primers (

Table 2) as well as by DNA sequencing of the flanking regions of the

crp gene on the chromosome. The above-mentioned genetic manipulations resulted in creation of the isogenic Δ

crp and P

BAD-

crp mutants of

Y. pestis strain 231.

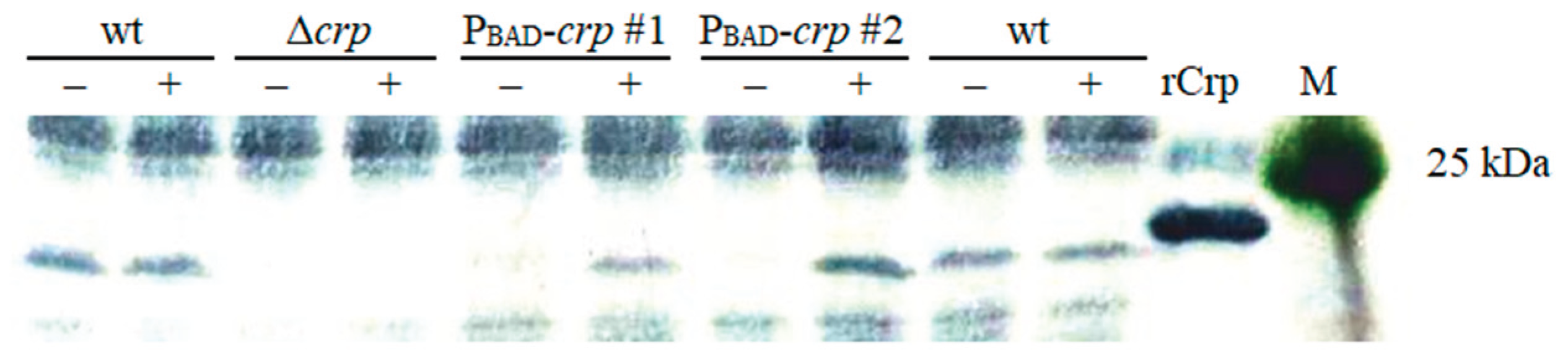

The growth of the P

BAD-

crp mutant strain in the presence of arabinose leads to transcription of the

crp gene, but gene expression stopped in the absence of arabinose. The presence of the Crp protein in

Y. pestis mutant strains was tested by Western blot using mouse antibodies raised against the His-tagged recombinant protein. Crp was not detected in the either 231Δ

crp or 231 P

BAD-

crp mutants grown in the absence of arabinose (

Figure 2). After arabinose addition, the P

BAD-

crp strain synthesized approximately the same amount of Crp as the parent wild-type

Y. pestis strain 231.

The Δcrp and the PBAD-crp strains without arabinose grew more slowly than the parent Y. pestis strain 231 in BHI medium (data not shown). When 0.2% arabinose was added to the nutrient medium, PBAD-crp grew at the same rate as the wild type strain.

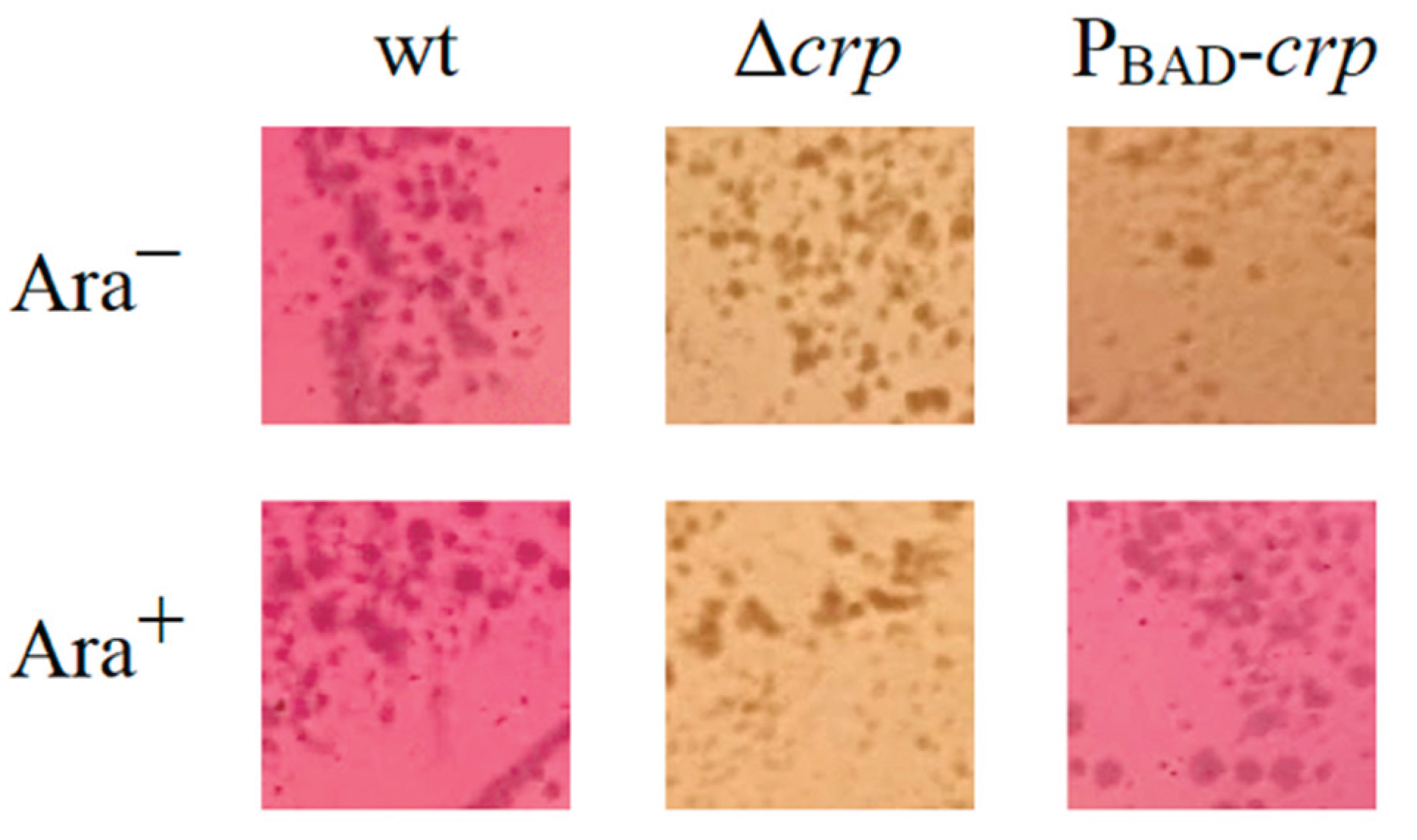

Crp increased expression of

malT, the transcriptional activator of maltose metabolism [

32]. The test of maltose fermentation can readily display the Crp activity. We analyzed the growth of wild-type 231, 231Δ

crp, P

BAD-

crp on MacConkey maltose agar without and with 0.2% arabinose (

Figure 3). The parent wild-type strain of

Y. pestis was able to ferment maltose to acid, which was accompanied by a decrease in pH, and as a result, the colonies changed color on MacConkey medium containing a red indicator with a neutral pH. The

Y. pestis 231Δ

crp mutant did not grow with maltose as the sole carbon source. The

Y. pestis 231P

BAD-

crp strain could ferment maltose only when grown in the presence of arabinose, but not in the absence of it.

3.2. Attenuation of Mutant Strains in s.c. Challenged Mice and Guinea Pigs

To investigate the contribution of Crp to

Y. pestis 231 strain virulence, we infected outbred mice and guinea pigs s.c. with

Y. pestis 231, 231Δ

crp, or 231P

BAD-

crp.

Y. pestis 231P

BAD-

crp strain was grown with arabinose prior to inoculation. The strain 231Δ

crp was nonlethal at doses of ≤ 10

7 CFU in mice. The LD

50 of 231Δ

crp strain in guinea pigs increased at least by 10

7-fold (LD

50 = 2.1 × 10

8 CFU) compared with that of the wild-type strain (LD

50 = 3 CFU) (

Table 3). The LD

50s of the 231P

BAD-

crp mutant in mice and guinea pigs were approximately 10

4-fold and 10

7-fold higher than those of

Y. pestis 231, respectively.

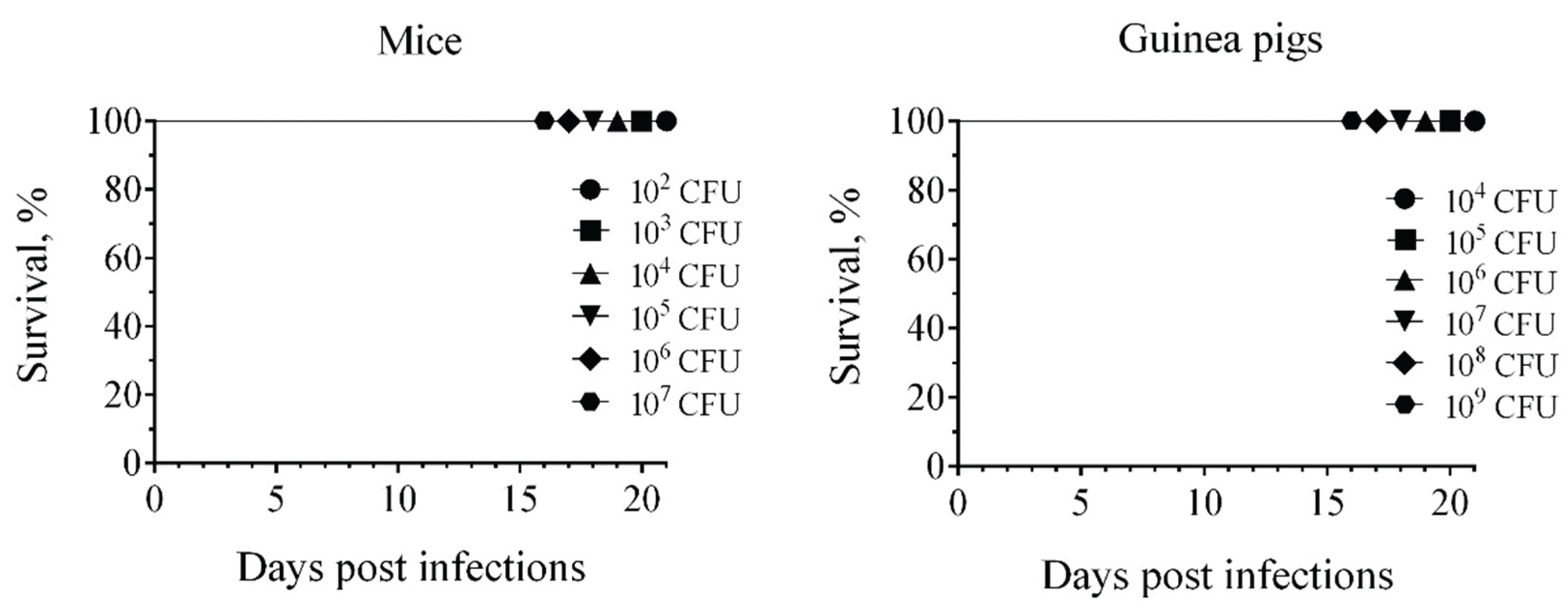

The degree of attenuation of the 231(P

BAD-

crp) mutant strain was increased by eliminating the pPst plasmid. We tested the ability of the plasmid-cured strain to infect outbred mice and guinea pigs. The 231P

BAD-

crp(pPst¯) strain was nonlethal at doses of approximately ≤ 10

7 CFU in mice and ≤ 10

9 CFU in guinea pigs (

Figure 4).

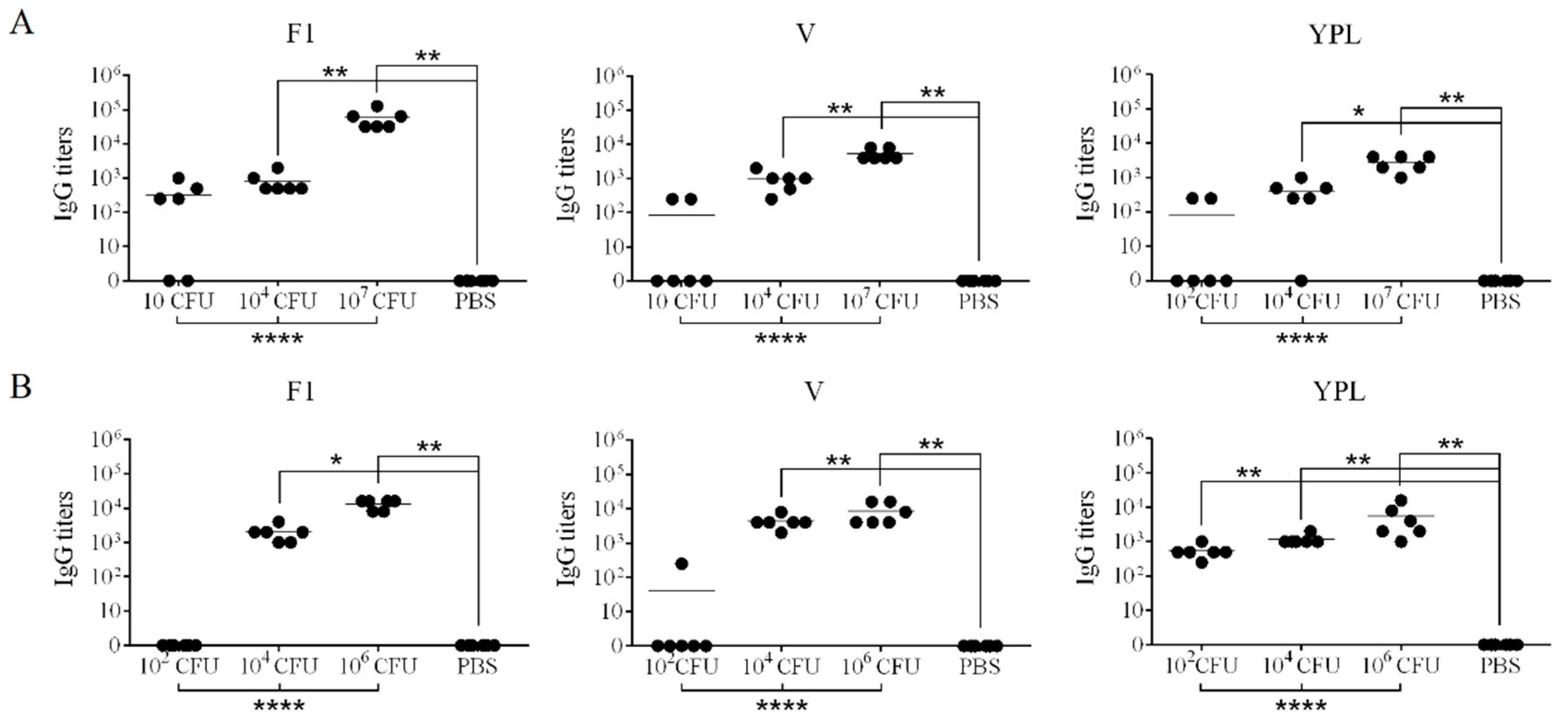

3.3. Humoral Immune Responses

Sera were collected from vaccinated mice and guinea pigs 28 days after immunization. The levels of serum IgG titers against two main immunodominant

Y. pestis protective antigens (F1 and LcrV) and

Y. pestis whole-cell lysate (YPL) were determined via ELISA (

Figure 5). Anti-F1 (

p < 0.0001), anti-LcrV (

p < 0.0001), and anti-YPL (

p < 0.0001) IgG titers in mice and guinea pigs increased in a dose-dependent manner when the levels of IgG induced by different immunized doses were compared. The differences in the levels of IgG to

Y. pestis antigens in the sera of mice and guinea pigs immunized with 10

2 CFU were insignificant (

p > 0.05).

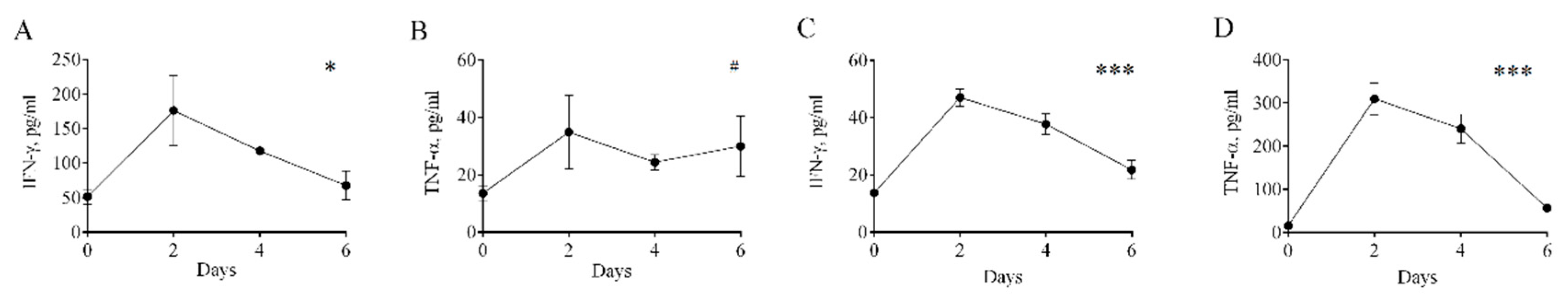

3.4. Cell-Mediated Immune Response

Then we measured the levels of the cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ in sera of mice and guinea pigs at various times after immunization with

Y. pestis strain 231P

BAD-

crp(pPst¯) (

Figure 6). In s.c.-immunized mice and guinea pigs, induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α followed similar kinetics. The levels of cytokines increased significantly by 48 h. Then the level of IFN-γ in the serum of mice and guinea pigs and TNF-α in guinea pigs decreased. In the serum of mice, the level of TNF-α remained almost at the same level from the second to the sixth day after the immunization with

Y. pestis strain 231P

BAD-

crp(pPst¯).

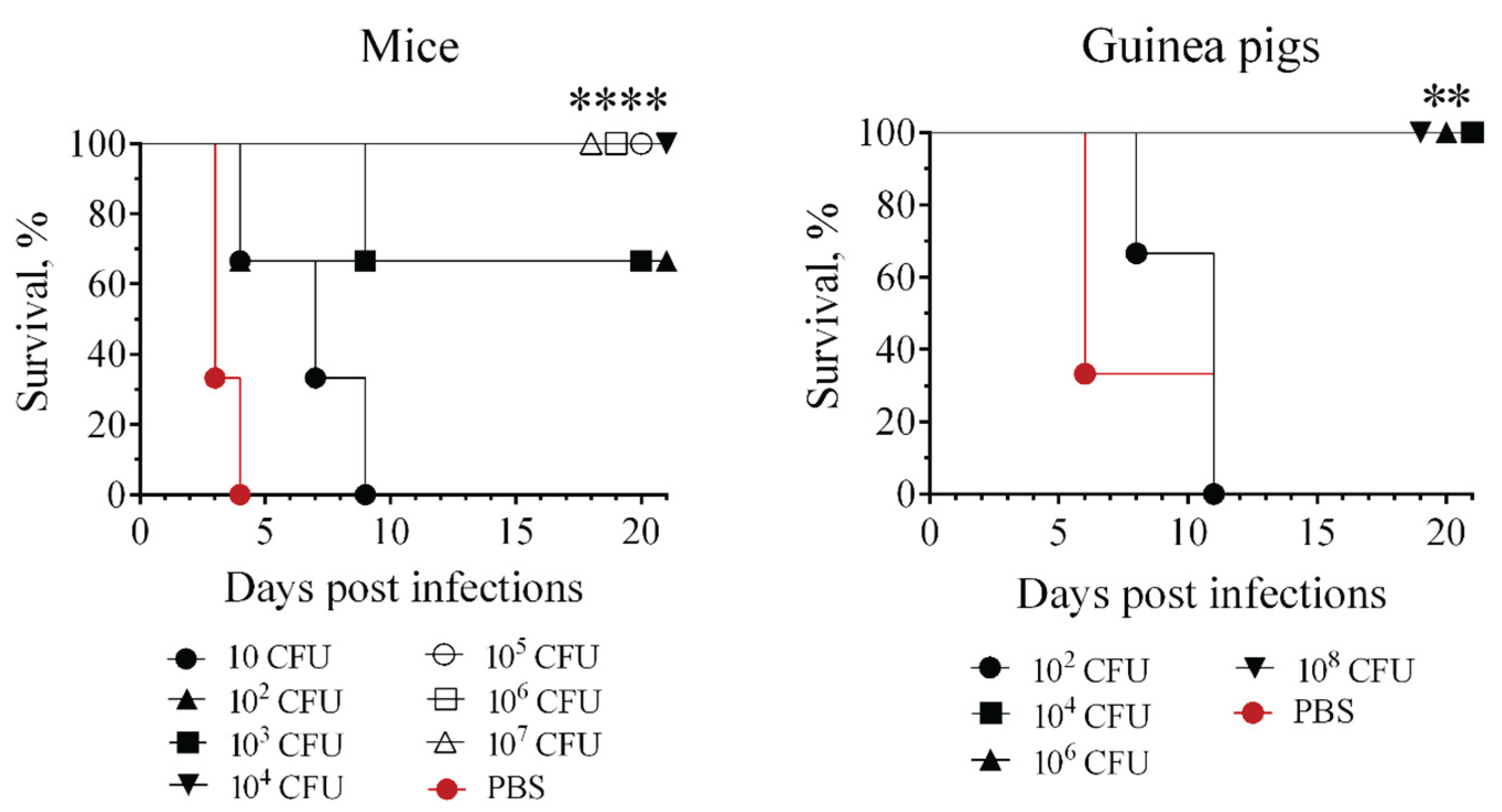

3.5. Abilities of s.c. Administered Strain with araC PBAD-Regulated crp Gene to Induce Protective Immunity to s.c. Challenge with Wild-Type Y. Pestis Strain 231

Groups of mice and guinea pigs were subcutaneously immunized with 10-fold or 100-fold (respectively) dilution doses of Y. pestis strain 231PBAD-crp(pPst¯) and challenged subcutaneously 30 days later with 200 LD100 (400 CFU for mice, 6 × 103 CFU for guinea pigs) of the wild-type strain 231.

Mice immunized with 10 CFU of the

Y. pestis 231P

BAD-

crp(pPst¯) mutant succumbed to plague after being challenged with 200 LD

100 of the WT

Y. pestis strain 231, but the post-infection lifespan of animals in this group was significantly increased compared with that of the naïve mice. 66.6% of the mice immunized subcutaneously with 10

2 or 10

3 CFU survived after challenge with 200 LD

100 of the WT

Y. pestis. 10

2 CFU, the lowest immunizing dose of the strain 231P

BAD-

crp(pPst¯), did not protect guinea pigs against infection with 200 LD

100 of the wild type

Y. pestis strain 231. The immunizing doses of ≥10

4 CFU were sufficient to ensure 100% survival of both animal species (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

Developing live bacterial vaccines presents a significant challenge: ensuring safety without compromising the ability to protect vaccinated individuals [

33]. However, traditional attenuation methods often result in bacteria becoming overly susceptible to the host's innate immunity, which prevents the development of a strong immune response. To overcome these limitations, researchers have engineered bacterial strains that initially exhibit the behavior of virulent wild-type bacteria, allowing them to effectively colonize the host’s tissues. Subsequently, these strains undergo a precisely controlled and delayed attenuation process within the host. This strategy prevents the disease while still triggering a powerful immune response. This regulated delayed attenuation can be accomplished through various genetic modifications [

14].

One approach involves substituting promoters of essential for virulence genes (

fur, crp, phoPQ,

rpoS) with an arabinose-dependent

araC P

BAD cassette [

13]. This ensures that expression of these genes relies on the presence of available arabinose during growth. Upon colonization of host tissues, arabinose deprivation halts the synthesis of these genes’ products, leading to gradual attenuation and preventing disease manifestations.

Relative evaluation of the

Y. pestis Δ

crp knockout mutant with its isogenic

araC P

BAD crp variant with arabinose-dependent regulated expression of the

crp gene showed that, compared with the parental KIM5+ strain (bv. Medievalis), both strains were significantly attenuated upon s.c. infection of Swiss Webster mice [

17]. LD

50 of the Δ

crp (3 × 10

7 CFU) and

araC P

BAD crp (4.3 × 10

5 CFU) mutants were approximately 10

6 and 10

4 times higher than those of the parent

Y. pestis strain KIM5+ (< 10 CFU), respectively. In our experiments conducted on derivatives of the

Y. pestis strain 231 from another phylogenetic group (bv. Antiqua), we obtained similar results. Compared with the parent strain (LD

50= 3 CFU for both animals), the LD

50 of the Δ

crp knockout mutant increased for outbred mice and guinea pigs by approximately six and seven orders of magnitude, while the virulence of the delayed-attenuation 231P

BAD-

crp variant decreased by approximately 1.9 × 10

4 and 1.5× 10

7 times.

However, according to the Russian national guidelines [

34]

Y. pestis candidate vaccine strains should not cause death in mice infected subcutaneously with 10

7 CFU and guinea pigs infected subcutaneously with 2 × 10

9 CFU and even 1,5 × 10

10 CFU. The Δ

crp mutant and the less attenuated isogenic P

BAD-

crp mutant didn’t meets these criteria.

At the same time, it is known that means for achieving regulated delayed attenuation can be combined with other mutations, which together may yield safe efficacious recombinant attenuated bacterial vaccines [

35]. The combination of different mutagenesis methods allows uniting diverse strategies for the rational approach to design of attenuated strains of pathogenic bacteria, candidates for vaccine strains [

36]. In our study, we took advantage of the fact that in some cases, the loss of the ability to produce plasminogen activator is accompanied by significant attenuation, and the plasmid encoding Pla does not contain genes for protective antigens [

37]. After low-temperature cultivation, we were able to select a pPst¯ clone of P

BAD-

crp mutant that reduced its virulence compared to the wild-type strain by at least 7 orders of magnitude in mice and at least 9 orders of magnitude in guinea pigs.

Isn't the path we've chosen to develop candidate vaccine strains too complex? Perhaps we could have stopped at one of the intermediate stages? Or, on the contrary, should we have continued editing the genome to remove or modify genes encoding proteins that are undesirable from a vaccinological perspective? Do our mutants combine safety with effective protection for immunized individuals belonging to different species or phylogenetic groups? Below we will try to answer some of these questions.

It is known that different animals react differently to

Y. pestis antigens [

38]. A mixed vaccine including the strains with special efficacy in rats and in guinea pigs protects both animal species better than the monocomponent ones. A multivalent vaccine, containing strains proven effective against both rats and guinea pigs, offers superior protection for these two animal species compared to vaccines targeting only a single strain. The efficacy of plague vaccines has been demonstrably enhanced through various combinatorial approaches. Studies have shown that administering live attenuated vaccines (#46-S, M #74, or MP-40) in conjunction with the existing EV vaccine significantly amplifies their protective effect [

39].

The generation of antibodies specific to

Y. pestis is crucial in fighting off infection [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. However, a strong and effective immune response against this pathogen also requires the activation of cellular immune mechanisms [

45,

46,

47,

48]. Immunization of mice and guinea pigs with 231P

BAD-

crp(pPst¯) elicits anti-F1, anti-LcrV, and anti-YPL serum IgG in a dose-dependent manner. The induction of cellular immunity against

Y. pestis by 231P

BAD-

crp(pPst¯) is confirmed by the observed increase in TNF-α and IFN-γ production levels in mice and guinea pigs immunized subcutaneously. Thus,

Y. pestis 231P

BAD-

crp(pPst¯) seems to stimulate both humoral and cellular immunity. Mice and guinea pigs immunized subcutaneously with a single dose (10

4 CFU) of the 231P

BAD-

crp(pPst¯) mutant were completely protected against a subcutaneous challenge with 200 LD

100 of the wild type

Y. pestis strain.

The strain 231PBAD-crp(pPst¯) is of interest as a vaccine candidate. It is possible that its predecessor with the pPst plasmid has a greater ability to protect animals due to greater residual virulence, but its ability to cause death in some infected individuals at doses of no more than 107 CFU excludes it from potential vaccine candidates.

5. Conclusions

Our results confirm that arabinose-dependent regulated expression of crp in combination with elimination of the pPst plasmid is an effective strategy for attenuating Y. pestis while maintaining high immunogenicity, providing protection a murine and guinea pig models against bubonic plague.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.P.A.; data curation: A.P.A., S.V.D.; formal analysis: A.S.T., A.S.V., E.M.M., T.V.G., N.A.L., R.Z.Sh., S.A.I., and P.Kh.K.; funding acquisition: A.P.A. and S.V.D.; investigation: A.S.V., M.E.P., A.S.T., T.V.G., E.M.M., N.A.L., R.Z.Sh., S.A.I., and P.Kh.K.; methodology: S.V.D., P.Kh.K., and M.E.P.; project administration: A.P.A. and S.V.D.; resources: A.P.A., S.V.D., and P.Kh.K.; software: A.S.V., A.S.T., E.M.M., and M.E.P.; supervision: S.V.D., A.S.V., and A.S.T.; validation: S.V.D., A.S.V., A.S.T., T.V.G., M.E.P., E.M.M., N.A.L., R.Z.Sh., and S.A.I.; visualization: A.S.V., A.S.T., T.V.G., N.A.L., R.Z.Sh., and S.A.I.; writing—original draft preparation: A.P.A., S.V.D., A.S.V., A.S.T., and N.A.L.; writing—review and editing: A.P.A., and S.V.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the State Research Center for Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (Permit No: VP-2025/1 on 30/04/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data will be provided on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zeppelini, C.G.; De Almeida, A.M.P.; Cordeiro-Estrela, P. Zoonoses As Ecological Entities: A Case Review of Plague. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016, 10, e0004949. [CrossRef]

- Gage, K.L.; Kosoy, M.Y. NATURAL HISTORY OF PLAGUE: Perspectives from More than a Century of Research. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2005, 50, 505–528. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, R.; Signoli, M.; Chevé, D.; Costedoat, C.; Tzortzis, S.; Aboudharam, G.; Raoult, D.; Drancourt, M. Yersinia Pestis: The Natural History of Plague. Clin Microbiol Rev 2020, 34, e00044-19. [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.A.; Jones, C.H.; Welch, V.; True, J.M. Outlook of Pandemic Preparedness in a Post-COVID-19 World. npj Vaccines 2023, 8, 178. [CrossRef]

- Updated WHO List of Emerging Pathogens for a Potential Future Pandemic: Implications for Public Health and Global Preparedness. Infez Med 2024, 4. [CrossRef]

- https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/consultation-rdb/prioritization-pathogensv6final.pdf?sfvrsn=c98effa7_9&download=true.

- Butler, T. Plague History: Yersin’s Discovery of the Causative Bacterium in 1894 Enabled, in the Subsequent Century, Scientific Progress in Understanding the Disease and the Development of Treatments and Vaccines. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2014, 20, 202–209. [CrossRef]

- D’Amelio, E.; Salemi, S.; D’Amelio, R. Anti-Infectious Human Vaccination in Historical Perspective. International Reviews of Immunology 2016, 35, 260–290. [CrossRef]

- Workshop WHO. Efficacy trials of Plague vaccines: endpoints, trial design, site selection. Retrieved June 7, 2021, from Who.int website: https://www.who.int/blueprint/what/norms-standards/PlagueVxeval_FinalMeetingReport.pdf; 2018.

- Adamovicz, J.J.; Andrews, G.P. Plague Vaccines. In Biological Weapons Defense; Lindler, L.E., Lebeda, F.J., Korch, G.W., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2005; pp. 121–153 ISBN 978-1-58829-184-4.

- Sun, W. Plague Vaccines: Status and Future. In Yersinia pestis: Retrospective and Perspective; Yang, R., Anisimov, A., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2016; Vol. 918, pp. 313–360 ISBN 978-94-024-0888-1.

- Rosenzweig, J.A.; Hendrix, E.K.; Chopra, A.K. Plague Vaccines: New Developments in an Ongoing Search. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2021, 105, 4931–4941. [CrossRef]

- Curtiss, R.; Wanda, S.-Y.; Gunn, B.M.; Zhang, X.; Tinge, S.A.; Ananthnarayan, V.; Mo, H.; Wang, S.; Kong, W. Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium Strains with Regulated Delayed Attenuation In Vivo. Infect Immun 2009, 77, 1071–1082. [CrossRef]

- Curtiss Iii, R.; Xin, W.; Li, Y.; Kong, W.; Wanda, S.-Y.; Gunn, B.; Wang, S. New Technologies in Using Recombinant Attenuated Salmonella Vaccine Vectors. Crit Rev Immunol 2010, 30, 255–270. [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Rodríguez, M.D.; Yang, J.; Kader, R.; Alamuri, P.; Curtiss, R.; Clark-Curtiss, J.E. Live Attenuated Salmonella Vaccines Displaying Regulated Delayed Lysis and Delayed Antigen Synthesis To Confer Protection against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Infect Immun 2012, 80, 815–831. [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Rodríguez, M.D.; Yang, J.; Kader, R.; Alamuri, P.; Curtiss, R.; Clark-Curtiss, J.E. Live Attenuated Salmonella Vaccines Displaying Regulated Delayed Lysis and Delayed Antigen Synthesis To Confer Protection against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Infect Immun 2012, 80, 815–831. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Roland, K.L.; Kuang, X.; Branger, C.G.; Curtiss, R. Yersinia Pestis with Regulated Delayed Attenuation as a Vaccine Candidate To Induce Protective Immunity against Plague. Infect Immun 2010, 78, 1304–1313. [CrossRef]

- Allio, T. The FDA Animal Rule and Its Role in Protecting Human Safety. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety 2018, 17, 971–973. [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.K.; Saviolakis, G.A.; Welkos, S.L.; House, R.V. Advanced Development of the rF1V and rBV A/B Vaccines: Progress and Challenges. Advances in Preventive Medicine 2012, 2012, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Kislichkina, A.A.; Krasil’nikova, E.A.; Platonov, M.E.; Skryabin, Y.P.; Sizova, A.A.; Solomentsev, V.I.; Gapel’chenkova, T.V.; Dentovskaya, S.V.; Bogun, A.G.; Anisimov, A.P. Whole-Genome Assembly of Yersinia Pestis 231, the Russian Reference Strain for Testing Plague Vaccine Protection. Microbiol Resour Announc 2021, 10, 10.1128/mra.01373-20. [CrossRef]

- Datsenko, K.A.; Wanner, B.L. One-Step Inactivation of Chromosomal Genes in Escherichia Coli K-12 Using PCR Products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000, 97, 6640–6645. [CrossRef]

- Cherepanov, P.P.; Wackernagel, W. Gene Disruption in Escherichia Coli: TcR and KmR Cassettes with the Option of Flp-Catalyzed Excision of the Antibiotic-Resistance Determinant. Gene 1995, 158, 9–14. [CrossRef]

- Donnenberg, M.S.; Kaper, J.B. Construction of an Eae Deletion Mutant of Enteropathogenic Escherichia Coli by Using a Positive-Selection Suicide Vector. Infect Immun 1991, 59, 4310–4317. [CrossRef]

- Lawton, W.D.; Stull, H.B. Gene Transfer in Pasteurella Pestis Harboring the F′ Cm Plasmid of Escherichia Coli. J Bacteriol 1972, 110, 926–929. [CrossRef]

- Bahmanyar M, Cavanaugh DC (1976) Plague Manual. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO).

- Ferber, D.M.; Brubaker, R.R. Plasmids in Yersinia Pestis. Infect Immun 1981, 31, 839–841. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Gurion, R.; Shafferman, A. Essential Virulence Determinants of Different Yersinia Species Are Carried on a Common Plasmid. Plasmid 1981, 5, 183–187. [CrossRef]

- Portnoy, D.A.; Falkow, S. Virulence-Associated Plasmids from Yersinia Enterocolitica and Yersinia Pestis. J Bacteriol 1981, 148, 877–883. [CrossRef]

- Protsenko, O.A., Anisimov P.I., Mozharov O.T., Konnov N.P., Popov Iu.A. Detection and characterization of Yersinia pestis plasmids determining pesticin I, fraction I antigen, and "mouse" toxin synthesis. Genetika 1983, 19, 7, 1081-1090.

- Okan, N.A.; Mena, P.; Benach, J.L.; Bliska, J.B.; Karzai, A.W. The smpB-ssrA Mutant of Yersinia Pestis Functions as a Live Attenuated Vaccine To Protect Mice against Pulmonary Plague Infection. Infect Immun 2010, 78, 1284–1293. [CrossRef]

- Dentovskaya, S.V.; Vagaiskaya, A.S.; Platonov, M.E.; Trunyakova, A.S.; Krasil’nikova, E.A.; Mazurina, E.M.; Gapel’chenkova, T.V.; Lipatnikova, N.A.; Shaikhutdinova, R.Z.; Ivanov, S.A.; et al. Protection Elicited by Glutamine Auxotroph of Yersinia Pestis. Vaccines 2025, 13, 353. [CrossRef]

- Steinsiek, S.; Bettenbrock, K. Glucose Transport in Escherichia Coli Mutant Strains with Defects in Sugar Transport Systems. J Bacteriol 2012, 194, 5897–5908. [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.A.; Henderson, L.M. New Technology for Improved Vaccine Safety and Efficacy. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 2001, 17, 585–597. [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, T.I.; Sayapina, L.V.; Sergeeva, G.M.; Isupov, I.V.; Beloborodov, R.A.; Samoilova, L.V.; Anisimov, A.P.; Ledvanov, M.Y.; Shvedun, G.P.; Zadumina, S.Y.; et al. Main Requirements for Vaccine Strains of the Plague Pathogen: Methodological Guidelines MU 3.3.1.1113-02; Federal Centre of State Epidemic Surveillance of Ministry of Health of Russian Federation: Moscow, Russia, 2002.

- Sun, W.; Six, D.; Kuang, X.; Roland, K.L.; Raetz, C.R.H.; Curtiss, R. A Live Attenuated Strain of Yersinia Pestis KIM as a Vaccine against Plague. Vaccine 2011, 29, 2986–2998. [CrossRef]

- Mba, I.E.; Sharndama, H.C.; Anyaegbunam, Z.K.G.; Anekpo, C.C.; Amadi, B.C.; Morumda, D.; Doowuese, Y.; Ihezuo, U.J.; Chukwukelu, J.U.; Okeke, O.P. Vaccine Development for Bacterial Pathogens: Advances, Challenges and Prospects. Tropical Med Int Health 2023, 28, 275–299. [CrossRef]

- Sebbane, F.; Uversky, V.N.; Anisimov, A.P. Yersinia Pestis Plasminogen Activator. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1554. [CrossRef]

- Anisimov, A.P.; Vagaiskaya, A.S.; Trunyakova, A.S.; Dentovskaya, S.V. Live Plague Vaccine Development: Past, Present, and Future. Vaccines 2025, 13, 66. [CrossRef]

- Korobkova, E.I. Live antiplague vaccine. Medgiz Mosc. 1956, 206.

- Hill, J.; Copse, C.; Leary, S.; Stagg, A.J.; Williamson, E.D.; Titball, R.W. Synergistic Protection of Mice against Plague with Monoclonal Antibodies Specific for the F1 and V Antigens of Yersinia Pestis. Infect Immun 2003, 71, 2234–2238. [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Rogers, D.; Russell, P.; Stagg, A.J.; Bell, D.L.; Eley, S.M.; Titball, R.W.; Williamson, E.D. The SCID/Beige Mouse as a Model to Investigate Protection against Yersinia Pestis. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology 1999, 23, 107–113. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, E.D.; Flick-Smith, H.C.; Waters, E.; Miller, J.; Hodgson, I.; Le Butt, C.S.; Hill, J. Immunogenicity of the rF1+rV Vaccine for Plague with Identification of Potential Immune Correlates. Microbial Pathogenesis 2007, 42, 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.D.; Macleod, C.; Henning, L.; Krile, R.; Chou, Y.-L.; Laws, T.R.; Butcher, W.A.; Moore, K.M.; Walker, N.J.; Williamson, E.D.; et al. Predictors of Survival after Vaccination in a Pneumonic Plague Model. Vaccines 2022, 10, 145. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zheng, B.; Lu, J.; Wu, H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Jiao, L.; Pan, H.; Zhou, J. Evaluation of Human Antibodies from Vaccinated Volunteers for Protection against Yersinia Pestis Infection. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12, e01054-24. [CrossRef]

- Smiley, S.T. Immune Defense against Pneumonic Plague. Immunological Reviews 2008, 225, 256–271. [CrossRef]

- Parent, M.A.; Wilhelm, L.B.; Kummer, L.W.; Szaba, F.M.; Mullarky, I.K.; Smiley, S.T. Gamma Interferon, Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha, and Nitric Oxide Synthase 2, Key Elements of Cellular Immunity, Perform Critical Protective Functions during Humoral Defense against Lethal Pulmonary Yersinia Pestis Infection. Infect Immun 2006, 74, 3381–3386. [CrossRef]

- Levy, Y.; Flashner, Y.; Tidhar, A.; Zauberman, A.; Aftalion, M.; Lazar, S.; Gur, D.; Shafferman, A.; Mamroud, E. T Cells Play an Essential Role in Anti-F1 Mediated Rapid Protection against Bubonic Plague. Vaccine 2011, 29, 6866–6873. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, E.D.; Kilgore, P.B.; Hendrix, E.K.; Neil, B.H.; Sha, J.; Chopra, A.K. Progress on the Research and Development of Plague Vaccines with a Call to Action. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 162. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram depicting the chromosomal structure of the crp deletion mutation and deletion-insertion mutations resulting in the arabinose-regulated crp gene.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram depicting the chromosomal structure of the crp deletion mutation and deletion-insertion mutations resulting in the arabinose-regulated crp gene.

Figure 2.

Crp synthesis in Y. pestis crp mutants. Strains were grown in BHI without (–) and with 0.2% arabinose (+) at 37°C overnight, and Crp synthesis was detected by Western blotting using anti-Crp sera. M, protein marker; rCrp – recombinant Crp; wt, wild type.

Figure 2.

Crp synthesis in Y. pestis crp mutants. Strains were grown in BHI without (–) and with 0.2% arabinose (+) at 37°C overnight, and Crp synthesis was detected by Western blotting using anti-Crp sera. M, protein marker; rCrp – recombinant Crp; wt, wild type.

Figure 3.

Phenotypes of Y. pestis strains with crp deletion-insertion mutations streaked on MacConkey maltose agar without (Ara−) and with 0.2% arabinose (Ara+).

Figure 3.

Phenotypes of Y. pestis strains with crp deletion-insertion mutations streaked on MacConkey maltose agar without (Ara−) and with 0.2% arabinose (Ara+).

Figure 4.

Virulence of Y. pestis strain 231PBAD-crp(pPst¯) for subcutaneously infected outbred mice (n = 6) and guinea pigs (n = 6).

Figure 4.

Virulence of Y. pestis strain 231PBAD-crp(pPst¯) for subcutaneously infected outbred mice (n = 6) and guinea pigs (n = 6).

Figure 5.

Antibody responses in sera of mice and guinea pigs immunized s.c. with 231PBAD-crp(pPst¯) at day 28 post immunization. Y. pestis whole-cell lysate (YPL) and recombinant F1 and LcrV were used as the coating antigens. T-test of unpaired samples and ANOVA were used. * – p < 0,05; **– p < 0,005; **** – р < 0,0001.

Figure 5.

Antibody responses in sera of mice and guinea pigs immunized s.c. with 231PBAD-crp(pPst¯) at day 28 post immunization. Y. pestis whole-cell lysate (YPL) and recombinant F1 and LcrV were used as the coating antigens. T-test of unpaired samples and ANOVA were used. * – p < 0,05; **– p < 0,005; **** – р < 0,0001.

Figure 6.

Cytokine levels in the sera of mice (A, B) and guinea pigs (C, D) immunized s.c. with 104 CFU of Y. pestis strain 231PBAD-crp(pPst¯). Serum samples were collected from 3 mice and 3 guinea pigs on days 2, 4, and 6 p.i. Values were calculated as picograms of cytokine per ml of blood. All experiments were performed twice with similar results. ANOVA was used. # – p > 0,05; * – p < 0,05; *** – р < 0,005.

Figure 6.

Cytokine levels in the sera of mice (A, B) and guinea pigs (C, D) immunized s.c. with 104 CFU of Y. pestis strain 231PBAD-crp(pPst¯). Serum samples were collected from 3 mice and 3 guinea pigs on days 2, 4, and 6 p.i. Values were calculated as picograms of cytokine per ml of blood. All experiments were performed twice with similar results. ANOVA was used. # – p > 0,05; * – p < 0,05; *** – р < 0,005.

Figure 7.

Survival of outbred mice (A) and guinea pigs (B) subcutaneously challenged with 200 LD100 of the WT Y. pestis strain 231 30 days after subcutaneous immunization with Y. pestis PBAD-crp(pPst¯) grown in the presence of arabinose. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used. ** – p < 0.05, **** – p < 0.0001.

Figure 7.

Survival of outbred mice (A) and guinea pigs (B) subcutaneously challenged with 200 LD100 of the WT Y. pestis strain 231 30 days after subcutaneous immunization with Y. pestis PBAD-crp(pPst¯) grown in the presence of arabinose. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used. ** – p < 0.05, **** – p < 0.0001.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain, plasmid |

Relevant attributes |

Source |

| Y. pestis |

|

| 231 |

0.ANT3 phylogroup, wild-type strain, universally virulent (LD50 for mice ≤ 10 CFU, for guinea pigs ≤ 10 CFU); Pgm+, pMT1+, pPst+, pCD+, parental strain |

SCPM-O1 [20] |

| EV |

1.ORI3 phylogroup, vaccine strain, Pgm—, pMT1+, pPst+, pCD+

|

SCPM-O |

| EVΔcrp::cat

|

Δcrp derivative of EV, CmR

|

|

| 231Δcrp

|

Δcrp derivative of 231, CmS

|

This study |

| 231PBAD-crp

|

ΔPcrp::araC PBAD crp derivative of Y. pestis 231 |

This study |

| 231PBAD-crp(pPst¯) |

ΔPcrp::araC PBAD crp pPst¯ derivative of Y. pestis 231PBAD-crp

|

This study |

| E. coli |

|

| DH5α |

F-, gyrA96(Nalr), recA1, relA1, endA1, thi-1, hsdR17(rk-, mk+), glnV44, deoR, Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169, [φ80dΔ(lacZ)M15], supE44

|

SCPM-O

|

| S17-1 λpir

|

thi pro hsdR−hsdM+ recA RP4 2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7(TpRSmRPmS) |

SCPM-O |

| BL21(DE3) |

F–ompT hsdSB (rB– mB–) gal dcm (DE3) |

SCPM-O |

| Plasmid |

|

|

| pKD46 |

bla araC PBADgam bet exo pSC101 oriTS |

[21] |

| pKD3 |

bla FRT cat FRT PS1 PS2 oriR6K |

[21] |

| pCP20 |

bla cat cI857 PRflp pSC101 oriTS |

[22] |

| pET-24b (+) |

kan pBR322 ori PT7

|

(Novagene) |

| pET24-crp

|

kan pBR322 ori PT7 crp

|

This study |

| pUC57 |

bla pUC ori

|

(Thermo Scientific) |

| pUC57-URcrp-araC Pbad-crp |

bla pUC ori araC PBAD crp

|

This study |

| pUC57-URcrp-Lt0TT-araC PBAD-crp

|

bla pUC ori bacteriophage Lambda t0 transcriptional terminator PBAD crp

|

This study |

| pCVD442 |

ori R6K mob RP4 bla sacB

|

[23] |

| pCVD442-Δcrp::cat

|

bla R6K ori RP4 mob sacB Δcrp::cat

|

This study |

| pCVD442-URcrp-Lt0TT- araC PBAD-crp

|

bla R6K ori RP4 mob sacB bacteriophage Lambda t0 transcriptional terminator PBAD crp

|

This study |

Table 2.

Primers used in this study.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study.

| crp Primers for Mutant Construction and Screening |

| Crp1F |

ATGGTTCTCGGTAAGCCACAAACAGACCCGACTCTCGAATGGTTCCTGTCTCATTATGGGAATTAGCCATGGTCC |

| Crp1R |

TTAACGGGTGCCGTAAACGACGATCGTTTTACCGTGTGCGGAGATCAAGTTTTGAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| Crp2F |

TAACAACAAAGATACAGCCC |

| Crp2R |

AGTAACAAAATTGTGCCACC |

| Crp-KF |

GACTTCGCGTACCTCAAAGC |

| Crp-KR |

TACATAACCGGAACCACAAC |

| Primers for pCVD442-URcrp-Lt0TT-PBAD-crp Construction |

| Pbad-SphI |

GCGGCATGCATAATGTGCCTGTCAAATGG |

| Pbad-XbaI |

GCGTCTAGAGAGAAACAGTAGAGAGTTGC |

| Lt0-SphIF |

AGCGCATGCTGACTCCTGTTGATAGATCC |

| Lt0-SphIR |

TTTGCATGCGACAAGTTGCTGCGATTCTC |

| Crp-Hind |

CCTAAGCTTCCCGGGTCGGCTGATAGATCAACTGC |

| Crp-SphI |

GAAGCATGCGCCGAAAGGTATAGCCAAGG |

| Crp-XbaI |

GCGTCTAGAAAGTTAGGCAGCGATAACAAC |

| Crp-SalI |

CTTGTCGACTTAACGGGTGCCGTAAAC |

| Primers for pET24-crp Construction |

| Crp-NdeI |

TAGTATCATATGGTTCTCGGTAAGCCACA |

| Crp-XhoI |

TACTCGAGACGGGTGCCGTAAACGACGAT |

| Screening for pCD1 |

| yscFPlus |

ACACCATATGAGTAACTTCTCTGGATTTACG |

| yscFMinus |

ATTCTCGAGTGGGAACTTCTGTAGGATG |

| Screening for pMT |

| caf1Plus |

AGTTCCGTTATCGCCATTGC |

| caf1Minus |

GGTTAGATACGGTTACGGTTAC |

| Screening for pPst |

| PstF |

CAATCATATGTCAGATACAATGGTAGTG |

| PstR |

CTCCTCGAGTTTTAACAATCCACTATC |

Table 3.

Virulence of Y. pestis strains in subcutaneously infected outbred mice and guinea pigs.

Table 3.

Virulence of Y. pestis strains in subcutaneously infected outbred mice and guinea pigs.

|

Y. pestis strains |

LD50, CFU |

| Mice |

Guinea pigs |

| 231 |

3 (1÷12) |

3 (1÷12) |

| 231Δcrp

|

> 107

|

2.1 × 108

|

| 231PBAD-crp

|

5.6 × 104

(1.4 × 104 ÷ 2.2 × 105) |

4.6 × 107

|

| 231PBAD-crp(pPst¯) |

> 107

|

> 109

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).