1. Introduction

Osteoporosis, characterized by reduced areal bone mineral density (BMD) and elevated risk of fractures, represents a major global public health concern [

1,

2]. Although commonly associated with older age, early-life factors, including peak bone mass acquisition during growth, play a critical role in lifelong fracture prevention and susceptibility. Research suggests that a 10% increase in peak bone mass during growth can reduce fracture risk by up to 50% later in life [

3,

4].

Among modifiable factors influencing bone development, physical activity is particularly important [

5,

6]. Exercise enhances bone strength by applying mechanical loads through gravitational forces and muscle tension at tendon insertion points [

7]. Numerous studies have shown that consistent physical activity during childhood and adolescence enhances bone mineral accumulation [

4,

6,

8], with dynamic, weight-bearing activities providing the most significant site-specific improvements [

4,

6,

9].

Artistic gymnastics imposes high dynamic mechanical loads on the skeleton up to 15 times body weight during jumps, landings, and acrobatic maneuvers, providing a potent stimulus for bone accrual during growth. This makes gymnastics an excellent model for studying long-term skeletal adaptations to weight-bearing physical activity [

7,

10,

11]. The early exposure to gymnastics is linked to structural benefits in the proximal femur and distal radius (as higher trabecular density, and favorable bone geometry), highlighting the positive impact of gymnastics on skeletal health [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Therefore, children and adolescents engaged in gymnastics generally develop higher bone density compared with peers involved in low-impact sports or those who remain inactive [

10,

11,

13,

14,

15,

16]. These benefits extend into adulthood, with former gymnasts maintaining higher bone mineral content than physically inactive individuals [

14,

17,

18,

19] and those engaged in other sports [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

However, research on BMD retention in middle-aged and older populations, when the risks of osteopenia and osteoporosis are heightened, remains scarce. Most studies on former gymnasts have focused on younger, particularly at elite levels, populations. Bass et al. [

20] found that retired elite gymnasts (~25 years old) had significantly higher BMD than matched controls, with no decline years after retiring. Similarly, Scerpella et al. [

19,

25] observed increased forearm BMD in gymnasts both before and after menarche, with benefits persisting up to four years post-training. Zanker et al. [

14] reported 6–10% greater BMD in former gymnasts aged 20–32, while Eser et al. (2009) documented greater bone mass and geometry in young females ~6 years post-retirement. Long-term bone benefits were further confirmed by Erlandson et al. [

21,

22] in individuals who trained between ages 8 and 15.

Only a few studies have examined BMD in adults ≥45 years. Kirchner et al. [

26] studied premenopausal females (29–45 years) and found higher BMD in former gymnasts compared to controls, even after adjusting for other physical activity. Pollock et al. [

17] evaluated former female collegiate gymnasts approaching menopause (45 ± 3 years) and reported that, 24 years post-retirement, former gymnasts exhibited higher BMD than controls, although the relative decline was similar in both groups. These findings suggest that early gymnastics practice can retain bone mineralization into early adulthood and potentially mitigate osteoporosis risk. However, similar studies are lacking in individuals over 45 despite the accelerated osteopenia/osteoporosis and increased fracture risk in this age group.

While evidence consistently supports the long-term bone health benefits of early gymnastics participation, the paucity of research involving older populations remains a notable gap, particularly considering their increasing relevance in the context of accelerated age-related bone loss. Thus, further investigation is needed to determine whether former gymnasts, particularly postmenopausal females, maintain sufficient BMD to lower the risk of osteoporosis. Supporting this link would strengthen the hypothesis that higher peak BMD achieved through youth gymnastics may offer protection against osteopenia in later life.

To address this gap, the present study compared bone mineralization and the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis in individuals aged 45 and older with a history of competitive artistic gymnastics to those in a control group. Physical activity over the past 10 years was also considered. Additionally, former gymnasts’ BMD was compared to normative data from large population-based cohorts. We hypothesized that former gymnasts would demonstrate higher BMD and a lower prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis than age-matched non-gymnasts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

The group of former gymnasts consisted of individuals aged 45 or older who had competed in artistic gymnastics between 1960 and 1990 in Brazil or Portugal. Recruitment was conducted through the Brazilian Gymnastics Confederation, the Portuguese Gymnastics Federation, and the Gymnastics Federation of the State of Rio de Janeiro, as well as directly contacting former athletes, coaches, and training centers in Brazil and Portugal. A control group, matched by age and body mass, was recruited from participants in university extension projects in Brazil and Portugal, through outreach via social media. For comparing BMD in former gymnasts with population values, data from the FIBRA Network (Frailty in Brazilian Older Adults, Brazil) and the Research Center for Physical Activity, Health, and Leisure — CIAFEL (Faculty of Sport, University of Porto, Portugal) were used. The FIBRA Network is a multicenter, multidisciplinary longitudinal study focused on investigating the prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors of frailty in the Brazilian population. The CIAFEL conducts prominent research on physical activity for older adults, including regular bone densitometry assessments.

Exclusion criteria included: (a) chronic conditions known to significantly affect bone mineralization (e.g., Cushing’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, skeletal malignancies, or Crohn’s disease); (b) history of chemotherapy or radiotherapy; (c) current pregnancy; and (d) diagnosis of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. All participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Rio de Janeiro State (CAAE: 67021322.6.0000.5259).

2.2. Study Design

Data were collected during a single visit to the research centers between June 2023 and April 2025. Initially, participants were screened for eligibility by inquiring about their medical history, menopause status, eating disorders, and medication use. Each visit lasted approximately 40 minutes. Participants first completed a questionnaire assessing physical activity during youth and in the past 10 years. Former gymnasts also reported competitive level, age of initiation, and training volume. Body weight and height were measured, and participants underwent a bone densitometry exam (full body and non-dominant femur). DXA reports were provided to participants and sent electronically.

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Bone Densitometry

Body composition was assessed using Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA) – Laboratory of Physical Activity and Health Promotion (LABSAU, Brazil, Lunar Prodigy Advance

TM, GE Healthcare, Madison, WI, USA); CIAFEL (Portugal, Hologic

TM Explorer QDR model, Hologic, Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA). Full-body scans were conducted by certified professionals with participants lying on their backs. The BMD per area (g/cm²) obtained through DXA is considered the gold standard for osteoporosis diagnosis and overall bone health, given its reproducibility, minimal radiation, and validated predictive value in large cohorts [

2,

3,

27,

28]. In this study, BMD was determined for the whole body and the non-dominant proximal femur, including the femoral neck. The procedures adhered to the official guidelines of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry [

28].

Participants were instructed to arrive 30 minutes prior to their scheduled appointment. Each scan took approximately 30 minutes. For the full-body measurement, participants remained relaxed on their backs, with their legs extended and arms by their sides. For the non-dominant femur measurement, participants were positioned on their backs with the hip flexed at 90° and abducted at 45°, ensuring the central beam was perpendicular to the thigh root. Prior to each scan, the device was calibrated using a “phantom” model. The precision and Least Significant Change were determined, with 2.5% and 6.9% set as the minimum acceptable values for BMD determination in the femoral neck.

For participants with surgical implants, such as metal prostheses or surgical staples, half of their body should be scanned for the full-body exam, and the results from the selected half were doubled – this happened in just one case. The number of individuals in the exam room was limited to two: the evaluator and the participant in LABSAU and only the participant in CIAFEL. In both places, the room temperature was maintained between 21 and 24 °C, and the relative humidity between 60-70%. Participants were advised to wear light, comfortable clothing, as thin as possible, to optimize the test and ensure comfort. Shoes and any metal objects, such as earrings, rings, bracelets, watches, glasses, or belts, were removed. Fasting was not required, but participants were asked to avoid alcohol and suspend calcium-containing medications 24 hours prior to the exam.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999-2004 normative databases, adjusted for white, black, and Hispanic males and females, were used as the reference for whole-body bone mineral content (BMC) based on a four-compartment model. The reference standard for calculating the T-score was the database for white females aged 20-29 years from NHANES III [

2]. According to these standards, the World Health Organization defines osteoporosis as a T-score of -2.5 or lower at the femoral neck, with T-scores between -1.5 and -2.5 indicating osteopenia.

2.3.2. Anthropometric Measurements

Height and body weight were measured by a trained researcher, with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using wall-mounted stadiometers. Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using an electronic scale – LABSAU (FilizolaTM, São Paulo, SP, Brazil) and CIAFEL (SECATM 899, Hamburg, Germany). The body mass index (BMI) was calculated (kg/m²).

2.3.3. Appendicular Muscle Mass Index – Sarcopenia Classification

Appendicular muscle mass was calculated as the lean mass of arms and legs (kg) and was used to calculate the Appendicular Skeletal Muscle Mass (ASM) index [ASM (kg) / height (m²)] [

29]. Cut-off points of ASM index were used to identify potential sarcopenia (5.45 Kg/m

2 for females and 7.26 Kg/m

2 for males) [

29]. Those cut-off values were defined as two standard deviations below sex-specific means of reference data obtained in the Rosetta Study with adults aged 18-40 years [

30].

2.3.4. Physical Activity Inventory

Physical activity during youth (10-20 years) (PA-Youth) and in the past 10 years (PA-10) were estimated using questions adapted from a previous study on former gymnasts aged 35-40 years [

26]. Participants were asked about the frequency (times per week), duration (minutes per session), and intensity (rated on a scale from 1 = light to 4 = very hard) of physical activity during each period.

In addition to intensity, training volume was also estimated, considering the number of years practiced, months per year, days per week, and hours per day. From this, total hours of physical activity were calculated, as well as an estimate of hours per week for each activity at the specified intensities. Former gymnasts were also asked about the duration of their competitive artistic gymnastics career and the training volume during that time, including training frequency and duration. The instruments used for data collection are provided as

supplementary material [Supplementary Material, Text 1].

2.3.5. Statistical Analysis

Normality was tested for each outcome using the full dataset within each group, applying the Shapiro–Wilk test and supported by standard normal probability plots. The W statistic rejected the normality assumption for some variables (T-scores, Z-scores, whole-body BMC), but never across all groups. In these cases, the plot of z-values (calculated from ordered deviations from the mean, i.e., residuals) against expected values from a Gaussian distribution showed a general lack of fit, with the data forming a distinct S-shaped pattern. Nevertheless, the normality assumption was considered sufficiently met to justify the use of parametric tests.

Differences between Brazilian and Portuguese former gymnasts were tested using the independent samples Student’s t-test. Differences in categorical variables were assessed using the chi-square test (χ²). Comparisons between former gymnasts and control groups for all variables were also performed using t-tests. Additionally, potential differences in bone mineralization variables were adjusted for PA-10 and age using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA).

Stratified comparisons between former gymnasts and controls were also conducted by age group (45–59 years and ≥ 60 years). Comparisons with the Brazilian and Portuguese reference populations were carried out using the independent samples t-test, for both the total sample and age-stratified groups. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05 for all analyses, which were conducted using SPSS version 20 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

Post hoc statistical power for the primary outcomes (bone densitometry variables) was assessed using G*Power version 3.1.5 (University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany), based on comparisons with control groups and reference populations. Effect sizes were calculated as Cohen’s d (using pooled standard deviations from independent t-tests) and partial eta squared (ηp²) for ANCOVA analyses. Statistical power was then estimated assuming α = 0.05 and the respective sample sizes.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Gymnasts in Brazil and Portugal

A total of 65 former gymnasts participated in the study, 45 from Brazil and 20 from Portugal, aged 45–84 years (32 males; 59 White, 3 Asian, 3 Black). Of these, 41 competed internationally and 24 at national/regional levels. Overall, participants from both countries showed equivalent profiles in demographic, clinical, and physical activity variables [

Supplement Material, Table S1]. Whole-body BMC and BMD, femoral BMD (neck and total), and related Z- and T-scores were also statistically equivalent and generally above age norms. No osteoporosis was found. Osteopenia (femoral neck) occurred more in females than males: Brazil (7 females, 1 male), Portugal (4 females, 0 male). Appendicular skeletal muscle mass index was comparable, with only two Brazilian males classified with sarcopenia. Data on gymnastics training (age of beginning, duration, volume) were also consistent across countries, supporting their inclusion as a single group for further comparisons.

3.2. Comparison Between Gymnasts and Controls

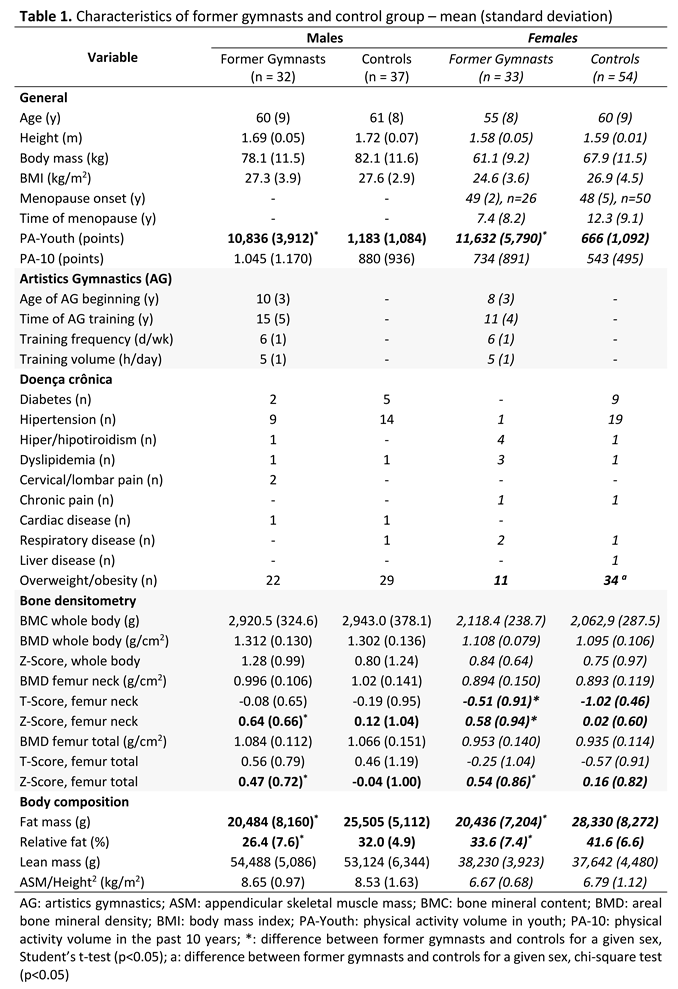

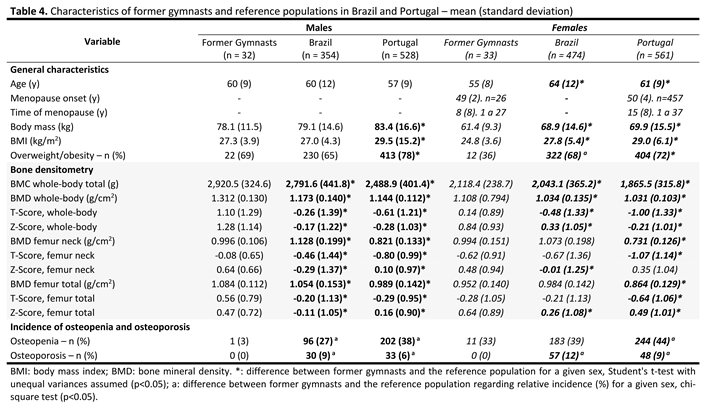

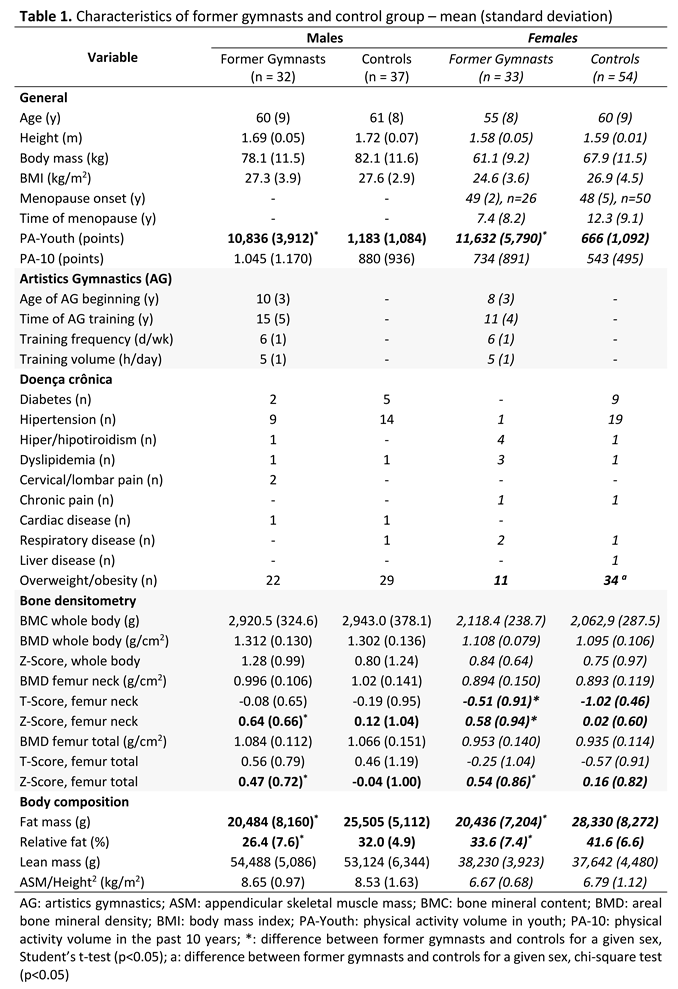

Table 1 summarizes data for 65 former gymnasts and 91 control participants (37 males; 68 White, 23 Black, age 45–87 years). Both groups were similar in age, height, body mass, and BMI, generally within normal or overweight ranges. Among females, 26 former gymnasts (4 months–27 years of onset) and 50 controls (6 months–37 years of onset) were postmenopausal, with comparable age at menopause and wide variability in time since onset. Nine former gymnasts (1–16 years) and seven controls (1–18 years) reported hormone or calcium therapy.

A full description of PA-10 and PA-Youth by sex is provided in the

Supplementary Material [Table S2]. As expected, PA-Youth differed significantly between groups, while PA-10 showed no significant differences, though former gymnasts trended toward higher activity. For PA-10, 10 former gymnasts (2 males, 8 females) and 10 controls (5 males, 5 females) reported inactivity. Among active participants, common activities of former gymnasts were strength training, walking/running, and dance for females; and walking/running, strength training, and cycling for males. In the control group, among other activities, control females reported strength training, walking/running, and aquatic exercise; males reported strength training, running/walking, and cycling. Activity profiles did not differ significantly between groups.

During youth, most former gymnasts (n = 56) practiced only artistic gymnastics; international-level gymnasts reported no other physical activity, while regional/national athletes also engaged in dance, tumbling, and swimming, among others. In this group, PA-Youth was higher than PA-10, with gymnastics being systematically classified as high intensity, frequency >5 sessions/week, 5–8 h/week. Among controls, PA-Youth was more variable and significantly lower than in former gymnasts (p < 0.001), reflecting unstructured, low-frequency leisure activity (≈2.5 days/week). No PA-Youth was reported by 24 female controls; others practiced ballet/dance, swimming, or volleyball. All but three control males reported some activity, mostly soccer, walking/running, and calisthenics.

Chronic conditions were reported by 27 former gymnasts (11 females, 16 males), and 55 controls (33 females, 22 males). Cardiovascular issues, musculoskeletal pain, and thyroid disorders were most common. The prevalence of chronic diseases was similar across groups. Overweight/obesity rates were comparable among males, but significantly higher among control females. Former gymnasts had lower fat mass and body fat percentage (p < 0.05), though lean and muscle mass did not differ. Obesity was more common in control females (10 vs. 4, p < 0.05), while the difference among males was not significant. DXA-confirmed fat percentages ranged from 45.6–55.8% in obese females and 30.4–41.9% in males. Total and relative fat mass were higher in controls, but ASM and lean mass were similar. Sarcopenia was more prevalent in controls (11 cases: 5 females or 9.3% and 6 males or 16.2%, 50-74 years) than in gymnasts (2 males or 3.1%, 66 and 84 years).

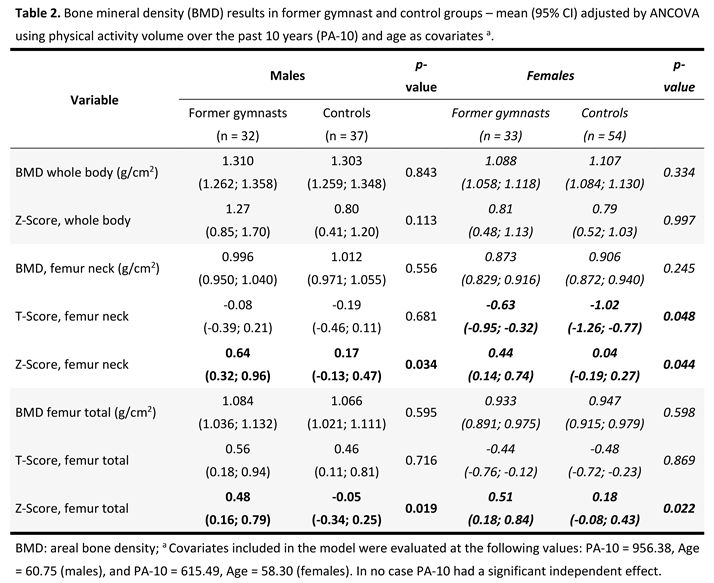

Bone densitometry comparisons revealed distinct patterns by sex and anatomical site. Significant differences were limited to the femoral neck T-score in females and to the Z-scores at the femoral neck and total femur in both sexes. Female gymnasts showed T-scores nearly twice as high as controls, and both male and female gymnasts exhibited Z-scores 5–10 times greater than those of their respective control groups. Effect sizes and corresponding statistical power for bone densitometry are available in the

Supplementary Material [Table S3]. Among males, the femoral neck Z-score showed a moderate effect size (d = 0.56; power = 0.67), and the total femur Z-score a similar magnitude (d = 0.56; power = 0.68). In females, the femoral neck T-score demonstrated a moderate-to-large effect (d = 0.68; power = 0.94), and the Z-score at the same site an even stronger difference (d = 0.79; power = 0.99). The total femur Z-score also showed a moderate effect (d = 0.49; power = 0.55). All other comparisons, including whole-body and femoral BMD, BMC, and T-scores, showed small effect sizes (|d| ≤ 0.33) and low statistical power (< 0.37), indicating no meaningful differences between groups.

Overall, these findings indicate that former gymnastics participation confers lasting, site-specific skeletal benefits, particularly in weight-bearing regions of the femur. No gymnast met the criteria for osteoporosis, whereas three control participants did. The prevalence of osteopenia or osteoporosis was lower among gymnasts (males: 3.1% vs. 16.2%, p = 0.01; females: 36.4% vs. 51.8%, p = 0.05).

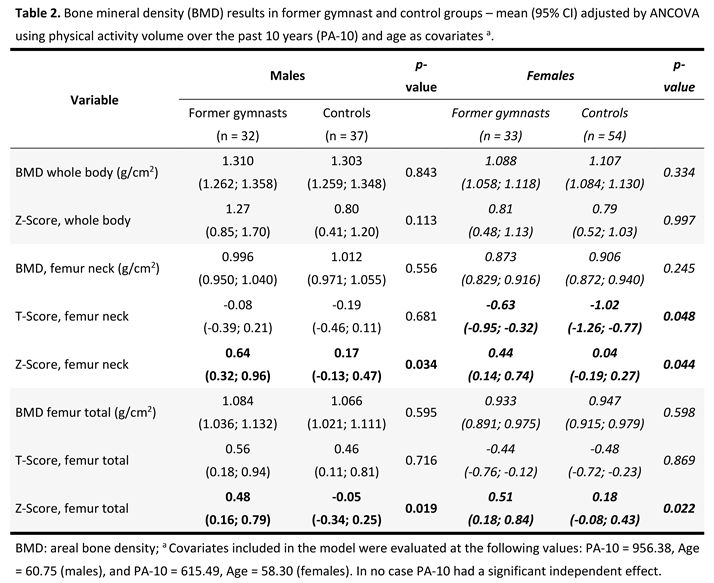

ANCOVA results (Table 2), adjusted for age and PA-10, confirmed higher femoral T- and Z-scores in former gymnasts. In any case PA-10 had a significant independent effect upon comparisons, while a few adjustments occurred due to age, however not changing the differences between former gymnasts and controls. Among males, partial eta squared values ranged from negligible to moderate (ηp² = 0.000–0.126), with corresponding statistical power between 0.05 and 0.72. The largest effects were observed for the total femur Z-Score (ηp² = 0.126; power = 0.72) and femoral neck Z-Score (ηp² = 0.102; power = 0.67). In females, ηp² values were generally small (0.000–0.090) with power up to 0.55, indicating modest group differences. The most notable effects in this sex were found for the femoral neck T-Score (ηp² = 0.078; power = 0.48), the femoral neck Z-Score (ηp² = 0.084; power = 0.53), and the total femur Z-Score (ηp² = 0.090; power = 0.55), all indicating a trend toward higher bone mineral density in former gymnasts [

Supplemental Material, Table S4]. These results suggest limited but consistent evidence of higher femoral bone density indices among former gymnasts, implying lasting skeletal adaptations despite adjustment for age and physical activity.

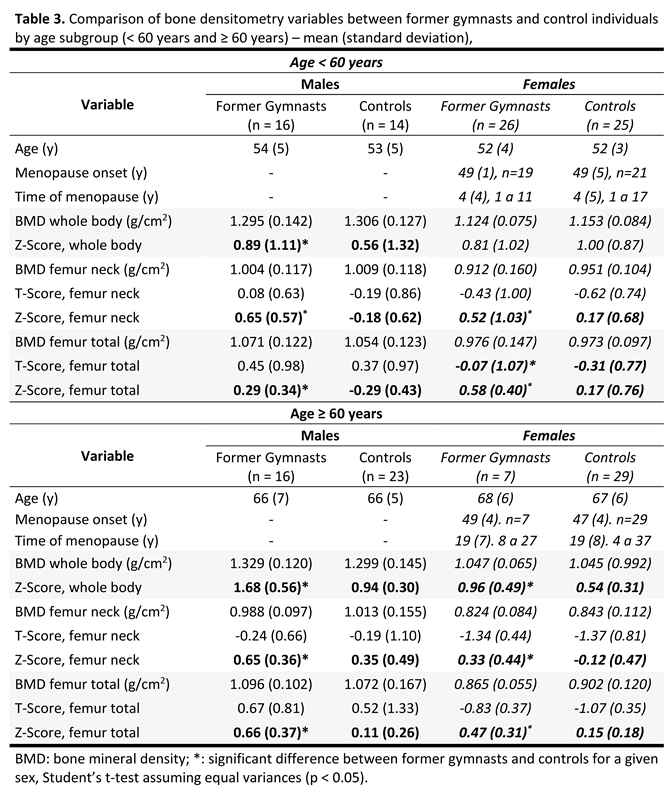

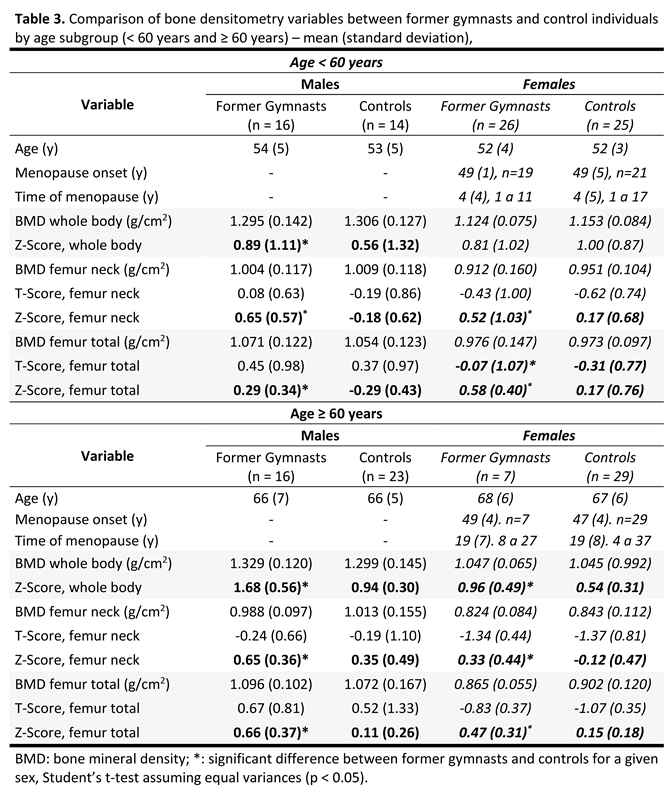

Given the isolated effect of age in several comparisons, an additional stratified analysis (Table 3) was performed for participants aged 45–59 and ≥60 years. Bone mineralization advantages were most pronounced in the younger group but persisted, though attenuated, in older participants.

To address the potential impact of hormone or calcium replacement therapy on bone mineralization, BMD and related indices were compared between postmenopausal former gymnasts and controls in additional analyses stratified by replacement therapy status

[Supplement Material, Table S5]. No consistent association between replacement therapy and bone outcomes was identified in either group. Former gymnasts receiving therapy showed marginally higher whole-body Z-scores, but this was not observed at other skeletal sites or among controls. Femoral neck Z-scores were consistently higher in gymnasts than in controls, irrespective of therapy status. Among non-users, gymnasts were younger and had a shorter time since menopause, which may have contributed to differences. Overall, replacement therapy appeared to exert a limited influence on BMD compared with prior gymnastics participation.

3.3. Comparison with Reference Populations

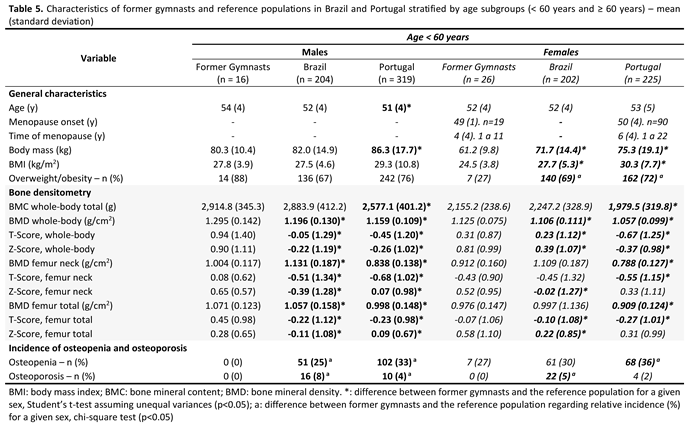

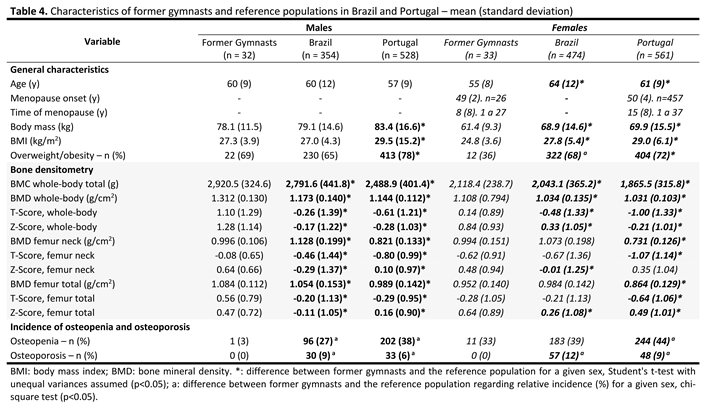

Table 4 summarizes femoral BMD data comparing former gymnasts with two reference populations: a Brazilian cohort (n = 828; 354 males; mixed ethnic backgrounds; age range 45–96 years) and a Portuguese cohort (n = 1,089; 528 males; all White; age range 45–88 years). Former female gymnasts were younger and had lower body mass and BMI than both reference groups. Among males, ages were comparable across groups, but former gymnasts exhibited lower body mass and BMI than their Portuguese counterparts. Overweight and obesity were more prevalent in the reference populations, particularly in females. Significant differences in males were observed only in comparison with the Portuguese data.

Bone densitometry analyses showed moderate to very large effect sizes in most comparisons, associated with statistical power values approaching 1.0, indicating robust differences between former gymnasts and the reference populations. A complete summary of effect sizes and statistical power is provided in the

Supplementary Material [Table S6].

Former gymnasts consistently exhibited higher whole-body BMC and BMD, with markedly elevated T- and Z-scores (up to fourfold greater than those of the reference populations), a difference that remains noteworthy even after accounting for the younger age of female gymnasts. In males, these differences were evident across all bone variables (d = 1.01–1.44 for whole-body and d = 0.74–1.46 for femoral sites, power > 0.98), confirming substantially greater bone density and preserved mass in load-bearing regions. The advantage was most pronounced relative to the Portuguese cohort (d ≈ 0.65–1.46, power = 0.95–1.00), whereas differences compared with the Brazilian population were moderate (d ≈ 0.22–0.86, power = 0.45–0.99). Among females, the effects were smaller but remained meaningful: former gymnasts exhibited higher whole-body and femoral neck mineralization compared with the Portuguese population (d = 0.65–1.89, power > 0.95), while their values were largely comparable to those of Brazilian counterparts (d < 0.55, power < 0.85).

In general, the large effect sizes and high statistical power support the conclusion that a background in gymnastics related to greater bone mass and density, particularly among males and relative to the Portuguese cohort. In consequence, osteopenia was notably less frequent among former gymnasts — especially males — and no cases of osteoporosis were observed, contrasting with the 6–12% prevalence reported in the reference populations. These findings highlight the long-term osteogenic benefits of impact-based training for preserving skeletal health with advancing age.

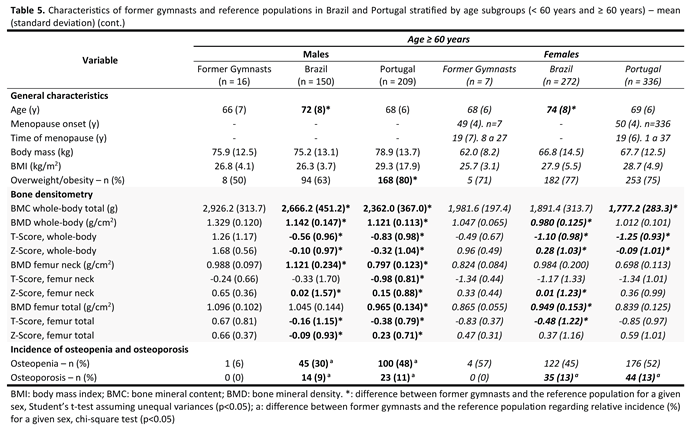

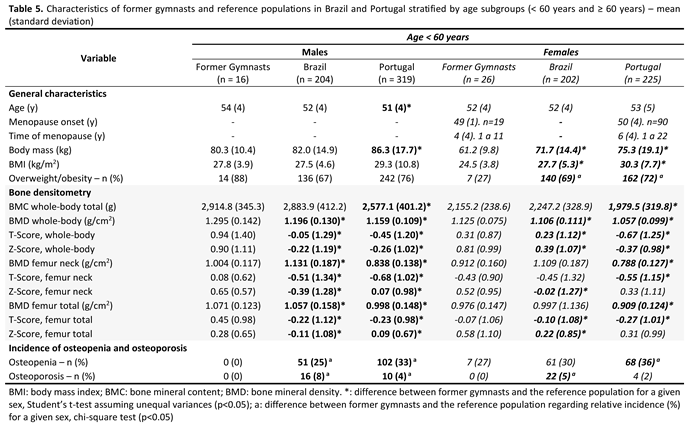

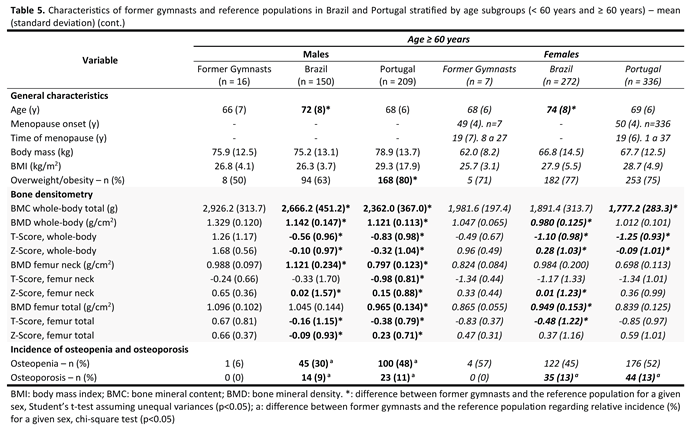

To account for age effects, a stratified analysis was conducted for participants <60 and ≥60 years (Table 5). In the <60 group, anthropometric characteristics were similar, though female gymnasts had significantly lower overweight/obesity prevalence. Both male and female gymnasts under 60 showed higher BMD, T-, and Z-scores than Brazilian and Portuguese peers. Osteopenia was notably less frequent in male gymnasts and moderately lower among female gymnasts. No osteoporosis was observed in any gymnast, while reference population rates ranged from 2–8%.

Among participants ≥60, Brazilian controls were older, and Portuguese males had slightly higher obesity prevalence than gymnasts. Former gymnasts maintained higher whole-body BMD and BMC, though differences were less pronounced. Male gymnasts continued to show superior femoral Z-scores (4–6 times higher), while advantages in females were smaller, particularly versus Portuguese controls. Osteopenia remained substantially lower in male gymnasts; among females, prevalence was moderate and statistically similar (57% vs. 45–52%). No gymnast showed osteoporosis, contrasting with 9–13% prevalence in the reference groups.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that adults aged ≥45 years with a history of competitive artistic gymnastics exhibit superior bone health compared with age-matched non-athletes and population-based references. Former gymnasts had higher femoral BMD, favorable T- and Z-scores, and lower prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis, supporting the concept of a “bone bank” established during youth through high-impact, osteogenic activities.

Gymnastics produces ground reaction forces up to 10–15 times body weight, offering potent mechanical stimuli that promote bone accrual during growth [

2,

6,

7,

16]. These high-impact forces drive skeletal adaptations such as increased cortical thickness, enhanced trabecular density, and favorable geometric changes [

8,

12], all of which contribute to greater fracture resistance, a key factor in maintaining skeletal health across the lifespan [

4,

15,

21,

22]. Notably, these structural benefits may persist for decades after training ceases, highlighting the long-term impact of early-life participation in high-impact sports. Evidence suggests that even after the discontinuation of training and competition, a portion of these skeletal adaptations is retained [

8].

Similarly, high-impact sports involving jumping, landing, and weight-bearing activities induce lasting structural changes in bone [

12,

13,

23,

24]. Early participation in such activities has been shown to enhance peak bone mass and produce residual improvements in bone mineralization and architecture that may persist well into adulthood [

4,

13,

14,

15,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

25].

Sex-specific patterns were evident: males retained skeletal benefits more consistently, while protection in females ≥60 years was attenuated, likely due to postmenopausal estrogen decline. Although whole-body BMD did not differ significantly, former female gymnasts consistently displayed higher femoral scores than their age-matched controls, highlighting clinically relevant protection during accelerated bone loss after menopause [

1,

27]. Early high-impact training appears to partially offset hormonal declines, contributing to a lower prevalence of osteopenia in females. In males, advantages were more consistent across ages, reflecting the absence of abrupt hormonal changes [

6,

31].

Former gymnasts also exhibited healthier body composition than controls, with lower fat mass and preserved lean mass. Although modest, these differences are clinically meaningful, as muscle–bone interactions play a key role in reducing frailty and fracture risk [

32,

33] and may enhance musculoskeletal resilience through synergistic effects on bone [

9,

24].

Current PA-10 levels were similar between groups, whereas former gymnasts reported higher PA-Youth, reinforcing adolescence as a critical window for maximizing peak bone mass [

6,

34]. Longitudinal studies suggest that up to 50% of adult BMD derives from peak values attained in youth [

4,

35], particularly at fracture-prone sites such as the hip, femoral neck, and lumbar spine [

31,

35]. ANCOVA confirmed that skeletal benefits persisted after adjusting for age and PA-10, emphasizing the cumulative advantage model, whereby higher peak bone mass provides a long-term skeletal resilience [

4,

31,

36].

Hormone and calcium therapy, known to influence bone mineralization in postmenopausal females [

37,

38], had minimal influence on BMD in our sample due to their low prevalence. No consistent BMD differences were observed between users and non-users. Whole-body Z-scores were higher in gymnasts on therapy, but this was not replicated at other sites or in controls. Femoral neck Z-scores remained higher in gymnasts regardless of therapy, suggesting that athletic history exerted a stronger effect. Non-users among gymnasts were younger with shorter menopause duration, which may have conferred additional protection given the steep early postmenopausal decline [

5,

27]. These findings confirm that impact exercise during youth yield lasting benefits, comparable to hormone therapy. A recent review [

32] concluded that both interventions help preserve BMD, though combined therapy is most effective. Given safety concerns with hormone therapy, exercise remains a cornerstone of osteoporosis prevention.

Comparisons with large population-based cohorts reinforced these results: Former gymnasts exhibited higher whole-body and femoral BMD, more favorable T- and Z-scores, and lower prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis than Brazilian and Portuguese references. Notably, no gymnast was diagnosed with osteoporosis, compared with 6–12% prevalence in the general population. Benefits were most evident before age 60; in females ≥60 years, protection was attenuated by prolonged postmenopausal bone loss, whereas males retained advantages across all ages. These sex-specific trajectories highlight interactions between early skeletal loading and hormonal influences on aging, consistent with functional reserve and cumulative advantage concepts [

4,

5,

36,

39].

Previous studies demonstrated that gymnasts retained skeletal benefits into midlife [

17,

26]. The present study originally extends this evidence to individuals ≥60 years, showing advantages even after decades of withdrawal from sport. These adaptations likely explain the absence of osteoporosis and the reduced prevalence of osteopenia in our sample [

4,

11]. In participants under 60 years, former gymnasts consistently displayed higher BMD, positive T- and Z-scores, and no osteoporosis, supporting the concept of a “bone bank” accrued during youth [

22,

34,

36,

40].

Among participants ≥60 years, male gymnasts maintained clear BMD advantages and low osteopenia prevalence, reflecting a lower susceptibility to bone loss [

41]. In females, those benefits appeared reduced: osteopenia prevalence reached 57%, aligning with rates observed in reference populations, while osteoporosis remained undetected. Although the small sample of older females limits interpretation, these findings provide novel evidence of skeletal preservation associated with early gymnastics. The absence of osteoporosis in both sexes, contrasting with 9–13% prevalence in Brazilian and Portuguese cohorts, further support to the hypothesis that high mechanical loading in youth protects against severe demineralization later in life [

3,

4,

6,

9,

24,

34,

36].

Sex differences were evident, with males retaining youth-acquired skeletal benefits more consistently, whereas reproductive aging constrained long-term protection in females. Similar patterns have been observed in other high-impact cohorts [

40,

42]. The abrupt estrogen decline at menopause accelerates bone loss, explaining why early training cannot fully offset postmenopausal deficits [

5,

39,

41]. Thus, mechanical loading during growth enhances peak bone mass, but these long-term effects seem to be modulated by hormonal changes across the lifespan.

Taken together, the findings suggest that early participation in competitive artistic gymnastics is associated with more favorable bone mineral density and body composition in later life. Benefits appear more robust in males, while reproductive aging, particularly postmenopausal estrogen decline partially attenuate in females. Lifelong physical activity remains important for preserving musculoskeletal health, but structural advantages gained through high-impact exercise during youth seem to play a foundational role.

This study has strengths and limitations. Strengths include the use of standardized DXA assessments, comparisons with large population databases, and a relatively large sample compared to previous studies on former gymnasts. However, limitations should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference, and the small subgroup sizes, especially among females aged 60 and over, limit statistical power and increase susceptibility to individual variability. Physical activity was assessed retrospectively, and key factors such as hormonal status, medication use, dietary intake, and lifestyle behaviors were not systematically controlled. Finally, direct comparisons with reference populations must be interpreted with caution, as the datasets were obtained in different methodological and temporal contexts and are influenced by cultural, nutritional, and socioeconomic differences beyond the scope of this study’s control.

5. Conclusion

Former gymnasts aged ≥ 45 years exhibited superior bone health compared to both age-matched controls and large reference populations from Brazil and Portugal, with higher femoral and whole-body BMD, lower prevalence of osteopenia, and no cases of osteoporosis. Benefits were most pronounced in females aged 45–60 years, while skeletal protection in females ≥ 60 was attenuated likely due to prolonged postmenopausal bone loss. Males retained advantages across all ages, suggesting durable bone reserves established through early-life training.

These findings reinforce the importance of promoting high-impact physical activity, such as artistic gymnastics, during youth to optimize peak bone mass and mitigate age-related skeletal decline. Early-life participation in artistic gymnastics may confer measurable and enduring protection against age-related skeletal decline, particularly during midlife. Nevertheless, ongoing bone health strategies remain critical in later life, particularly for postmenopausal females, who remain at elevated risk for bone loss despite earlier benefits. Future longitudinal, multicenter studies with comprehensive tracking of hormonal, nutritional, and behavioral factors are needed to clarify the magnitude and duration of these protective effects, and whether they can be enhanced through continued physical activity or targeted interventions.

6. Implications for Health Promotion

Our findings indicate that early engagement in high-impact, weight-bearing exercise is associated with sustained skeletal benefits, supporting the concept that mechanical loading during youth contributes to long-term bone health. Participation in activities such as artistic gymnastics, jumping, or other multidirectional sports aligns with recommendations from organizations including the World Health Organization, the American College of Sports Medicine, and the International Osteoporosis Foundation, which emphasize vigorous, osteogenic exercise to enhance peak bone mass and lower fracture risk later in life.

The prepubertal and pubertal periods appear to be critical windows for bone accrual; accordingly, structured high-impact exercise performed three to four times per week under supervised and safe conditions may be beneficial. In adulthood, particularly following menopause, combined exercise programs incorporating moderate-impact, resistance, and balance training have been shown to help maintain bone mass and attenuate postmenopausal bone loss. Overall, these findings support a lifespan approach to skeletal health, in which early mechanical loading contributes to the establishment of a robust skeletal framework that, when maintained through continued physical activity, may reduce the risk of osteopenia and osteoporosis in later life.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

PAAF: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Investigation, Project Administration, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review and Editing; CS: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Review and Editing; RZ: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Review and Editing; LAC: Methodology, Writing – Review and Editing; JM: Methodology, Data Curation, Funding Acquisition, Writing – Review and Editing; IM: Data Curation, Writing – Review and Editing; JC: Supervision, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review and Editing; NSLS: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – Review and Editing; PF: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Formal Analysis; Funding Acquisition, Supervision, Project Administration, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially supported by grants from CAPES (88881.846590/2023-01, recipient Patricia Farinatti), CNPq (305262/2023-8, recipient Paulo Farinatti), and FCT (UID/00617/2025, recipient Rodrigo Zacca).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Rio de Janeiro State (CAAE: 67021322.6.0000.5259, opinion 6.057.170, May 12th 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Dr. Roberto Lourenço and Prof. Dr. Flávia Fiorucci from the State University of Rio de Janeiro for granting access to the FIBRA Project database. We also thank Adriano Oliveira, Caio Ramado, Gabriela Paz, Carlos Aiello, Jeferson Rocha, José Cristiano Paes Leme, and Michel Silva, for the valuable support during the data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AG |

Artistic gymnastics |

| ANCOVA |

Analysis of covariance |

| ASM |

Appendicular skeletal muscle mass |

| BMC |

Bone mineral content |

| BMD |

Bone mineral density |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| CIAFEL |

Research Center for Physical Activity, Health, and Leisure |

| DXA |

Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry |

| FIBRA |

Frailty in Brazilian Older Adults |

| LABSAU |

Laboratory of Physical Activity and Health Promotion |

| NHANES |

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| PA-Youth |

Physical activity volume during youth (10-20 years) |

| PA-10 |

Physical activity volume in the past 10 years |

| DBP |

Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| HR |

Heart Rate |

| HRV |

Heart Rate Variability |

| LABSAU |

Laboratory of Physical Activity and Health Promotion |

References

- Radominski, S.C.; Bernardo, W.; Paula, A.P.; Albergaria, B.H.; Moreira, C.; Fernandes, C.E.; Castro, C.H.M.; Zerbini, C.A.F.; Domiciano, D.S.; Mendonca, L.M.C.; et al. Brazilian guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Revista brasileira de reumatologia 2017, 57 Suppl 2, 452-466. [CrossRef]

- Kanis, J.A.; Cooper, C.; Rizzoli, R.; Reginster, J.Y.; Scientific Advisory Board of the European Society for, C.; Economic Aspects of, O.; the Committees of Scientific, A.; National Societies of the International Osteoporosis, F. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA 2019, 30, 3-44. [CrossRef]

- Bonjour, J.P.; Chevalley, T.; Ferrari, S.; Rizzoli, R. The importance and relevance of peak bone mass in the prevalence of osteoporosis. Salud publica de Mexico 2009, 51 Suppl 1, S5-17. [CrossRef]

- Pageau, A.G.; Burt, L.A.; Gabel, L.; Boyd, S.K.; Whittier, D.E. The association between physical activity during growth and bone microarchitecture at peak bone mass. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2025. [CrossRef]

- Demontiero, O.; Vidal, C.; Duque, G. Aging and bone loss: new insights for the clinician. Therapeutic advances in musculoskeletal disease 2012, 4, 61-76. [CrossRef]

- Min, S.K.; Oh, T.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, J.; Chung, H.Y.; Park, D.H.; Kim, C.S. Position statement: Exercise guidelines to increase peak bone mass in adolescents. Journal of bone metabolism 2019, 26, 225-239. [CrossRef]

- Kohrt, W.M.; Bloomfield, S.A.; Little, K.D.; Nelson, M.E.; Yingling, V.R.; American College of Sports, M. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand: physical activity and bone health. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 2004, 36, 1985-1996. [CrossRef]

- Gunter, K.B.; Almstedt, H.C.; Janz, K.F. Physical activity in childhood may be the key to optimizing lifespan skeletal health. Exercise and sport sciences reviews 2012, 40, 13-21. [CrossRef]

- Kopiczko, A.; Baldyka, J.; Adamczyk, J.G.; Nyrc, M.; Gryko, K. Association between long-term exercise with different osteogenic index, dietary patterns, body composition, biological factors, and bone mineral density in female elite masters athletes. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 9167. [CrossRef]

- Exuperio, I.N.; Agostinete, R.R.; Werneck, A.O.; Maillane-Vanegas, S.; Luiz-de-Marco, R.; Mesquita, E.D.L.; Kemper, H.C.G.; Fernandes, R.A. Impact of artistic gymnastics on bone formation markers, density and geometry in female adolescents: ABCD-Growth Study. Journal of bone metabolism 2019, 26, 75-82. [CrossRef]

- Burt, L.A.; Greene, D.A.; Naughton, G.A. Bone health of young male gymnasts: A systematic review. Pediatric exercise science 2017, 29, 456-464. [CrossRef]

- Gruodyte-Raciene, R.; Erlandson, M.C.; Jackowski, S.A.; Baxter-Jones, A.D. Structural strength development at the proximal femur in 4- to 10-year-old precompetitive gymnasts: a 4-year longitudinal hip structural analysis study. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2013, 28, 2592-2600. [CrossRef]

- Jurimae, J.; Gruodyte-Raciene, R.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.G. Effects of gymnastics activities on bone accrual during growth: A systematic review. J Sports Sci Med 2018, 17, 245-258.

- Zanker, C.L.; Osborne, C.; Cooke, C.B.; Oldroyd, B.; Truscott, J.G. Bone density, body composition and menstrual history of sedentary female former gymnasts, aged 20-32 years. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA 2004, 15, 145-154. [CrossRef]

- Erlandson, M.C.; Runalls, S.B.; Jackowski, S.A.; Faulkner, R.A.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.G. Structural strength benefits observed at the hip of premenarcheal gymnasts are maintained into young adulthood 10 years after retirement from the sport. Pediatric exercise science 2017, 29, 476-485. [CrossRef]

- Maïmoum, L.; Coste, O.; Philibert, P.; Briot, K.; Mura, T.; Galtier, F.; Mariano-Goulart, D.; Paris, F.; Sultan, C. Peripubertal female athletes in high-impact sports show improved bone mass acquisition and bone geometry. Metabolism: clinical and experimental 2013, 62, 1088-1098. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, N.K.; Laing, E.M.; Modlesky, C.M.; O’Connor, P.J.; Lewis, R.D. Former college artistic gymnasts maintain higher BMD: a nine-year follow-up. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA 2006, 17, 1691-1697. [CrossRef]

- Eser, P.; Hill, B.; Ducher, G.; Bass, S. Skeletal benefits after long-term retirement in former elite female gymnasts. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2009, 24, 1981-1988. [CrossRef]

- Scerpella, T.A.; Dowthwaite, J.N.; Rosenbaum, P.F. Sustained skeletal benefit from childhood mechanical loading. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA 2011, 22, 2205-2210. [CrossRef]

- Bass, S.; Pearce, G.; Bradney, M.; Hendrich, E.; Delmas, P.D.; Harding, A.; Seeman, E. Exercise before puberty may confer residual benefits in bone density in adulthood: studies in active prepubertal and retired female gymnasts. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 1998, 13, 500-507. [CrossRef]

- Erlandson, M.C.; Kontulainen, S.A.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Arnold, C.M.; Faulkner, R.A.; Baxter-Jones, A.D. Former premenarcheal gymnasts exhibit site-specific skeletal benefits in adulthood after long-term retirement. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2012b, 27, 2298-2305. [CrossRef]

- Erlandson, M.C.; Kontulainen, S.A.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Arnold, C.M.; Faulkner, R.A.; Baxter-Jones, A.D. Higher premenarcheal bone mass in elite gymnasts is maintained into young adulthood after long-term retirement from sport: a 14-year follow-up. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2012a, 27, 104-110. [CrossRef]

- Mudd, L.M.; Fornetti, W.; Pivarnik, J.M. Bone mineral density in collegiate female athletes: comparisons among sports. J Athl Train 2007, 42, 403-408.

- Tenforde, A.S.; Fredericson, M. Influence of sports participation on bone health in the young athlete: a review of the literature. PM R 2011, 3, 861-867. [CrossRef]

- Scerpella, T.A.; Bernardoni, B.; Wang, S.; Rathouz, P.J.; Li, Q.; Dowthwaite, J.N. Site-specific, adult bone benefits attributed to loading during youth: A preliminary longitudinal analysis. Bone 2016, 85, 148-159. [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, E.M.; Lewis, R.D.; O’Connor, P.J. Effect of past gymnastics participation on adult bone mass. Journal of applied physiology 1996, 80, 226-232. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J.C. Effect of early menopause on bone mineral density and fractures. Menopause 2007, 14, 567-571. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, D.; Tanner, S.B.; Szalat, A.; Malabanan, A.; Prout, T.; Lau, A.; Rosen, H.N.; Shuhart, C. DXA Reporting Updates: 2023 Official Positions of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry. J Clin Densitom 2024, 27, 101437. [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.N.; Koehler, K.M.; Gallagher, D.; Romero, L.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Ross, R.R.; Garry, P.J.; Lindeman, R.D. Epidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New Mexico. Am J Epidemiol 1998, 147, 755-763. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, D.; Visser, M.; De Meersman, R.E.; Sepulveda, D.; Baumgartner, R.N.; Pierson, R.N.; Harris, T.; Heymsfield, S.B. Appendicular skeletal muscle mass: effects of age, gender, and ethnicity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1997, 83, 229-239. [CrossRef]

- Strope, M.A.; Nigh, P.; Carter, M.I.; Lin, N.; Jiang, J.; Hinton, P.S. Physical activity-associated bone loading during adolescence and young adulthood Is positively associated with adult bone mineral density in men. American journal of men’s health 2015, 9, 442-450. [CrossRef]

- Platt, O.; Bateman, J.; Bakour, S. Impact of menopause hormone therapy, exercise, and their combination on bone mineral density and mental wellbeing in menopausal women: a scoping review. Front Reprod Health 2025, 7, 1542746. [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; He, Y.; Liu, K.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y. Priority interventions for the prevention of falls or fractures in patients with osteoporosis: A network meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2024, 127, 105558. [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Rodriguez, G. How does exercise affect bone development during growth? Sports Med 2006, 36, 561-569. [CrossRef]

- Bielemann, R.M.; Domingues, M.R.; Horta, B.L.; Menezes, A.M.; Goncalves, H.; Assuncao, M.C.; Hallal, P.C. Physical activity throughout adolescence and bone mineral density in early adulthood: the 1993 Pelotas (Brazil) Birth Cohort Study. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA 2014, 25, 2007-2015. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M.K.; Nordqvist, A.; Karlsson, C. Physical activity increases bone mass during growth. Food & nutrition research 2008, 52. [CrossRef]

- Sheedy, A.N.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Hovey, K.M.; LaMonte, M.J. Discontinuation of hormone therapy and bone mineral density: does physical activity modify that relationship? Menopause 2023, 30, 1199-1205. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, C. Association of hormone preparations with bone mineral density, osteopenia, and osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2018. Menopause 2023, 30, 591-598. [CrossRef]

- Riggs, B.L.; Melton Iii, L.J., 3rd; Robb, R.A.; Camp, J.J.; Atkinson, E.J.; Peterson, J.M.; Rouleau, P.A.; McCollough, C.H.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Khosla, S. Population-based study of age and sex differences in bone volumetric density, size, geometry, and structure at different skeletal sites. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2004, 19, 1945-1954. [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; McKay, H.A.; Haapasalo, H.; Bennell, K.L.; Forwood, M.R.; Kannus, P.; Wark, J.D. Does childhood and adolescence provide a unique opportunity for exercise to strengthen the skeleton? Journal of science and medicine in sport 2000, 3, 150-164. [CrossRef]

- Seeman, E. Pathogenesis of bone fragility in women and men. Lancet 2002, 359, 1841-1850. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C.J.; Beaupre, G.S.; Carter, D.R. A theoretical analysis of the relative influences of peak BMD, age-related bone loss and menopause on the development of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA 2003, 14, 843-847. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).