1. Introduction

The genus

Adansonia, part of the

Bombacoideae subfamily in the

Malvaceae family, includes eight existing species of tall deciduous trees globally. Among these, six species are endemic to Madagascar, while the remaining two are distributed in mainland Africa and Australia, respectively [

1]. All components of the baobab tree, including its fruit, leaves, seeds, roots, and bark, serve as valuable food sources [

2]. Additionally, they are utilized in traditional medicine for treating ailments like diarrhea, dysentery, and fever [

3], highlighting their considerable edible, medicinal, and economic importance. In 2008, the European Commission approved dried baobab fruit pulp as a novel food. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved baobab fruit pulp as a food ingredient in 2009.The drastic decline in suitable habitats for Adansonia trees, caused by global climate change and habitat destruction, has garnered significant attention from the scientific community and the public concerning their conservation.

Adansonia suarezensis, a species indigenous to Madagascar, was classified as threatened on the IUCN Red List in December 2015 [

4]. Two decades ago, the Jubao Lin Seedling Planting Professional Cooperative introduced

Adansonia suarezensis to Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, which have now developed trunks of substantial girth, approximately requiring three adults with joined arms to encircle. In 2023, the tree successfully bore fruit for the first time through artificial pollination. The fruits are oval-shaped, measuring approximately 30–35 cm in length and 15–20 cm in width when mature. This introduction has demonstrated the species’ ability to adapt to the local climate in Zhanjiang and its capacity to successfully bear fruit following artificial pollination.

Research indicates that natural polysaccharides exhibit a range of biological activities, including antioxidant, immunomodulatory, antiviral, antitumor, anti-aging, and hypolipidemic effects [

5]. Compared to chemically synthesized drugs, polysaccharides derived from natural plant sources exhibit minimal side effects [

6]. Consequently, increasing research efforts are dedicated to identifying naturally active polysaccharides capable of replacing synthetic drugs. The composition and bioactivity of baobab fruit polysaccharides may vary significantly depending on their growth environments. Previous research has shown that baobab fruit polysaccharides exhibit significant antioxidant, antihyperglycemic, antimicrobial, antihypertensive, and anti-inflammatory properties. The study by Bougatef et al. Polysaccharides extracted from baobab (

Adansonia digitata) fruit pulp in southern Mauritania showed a DPPH radical scavenging rate of 97.09 ± 0.01% at 5 mg/mL, an ABTS radical scavenging rate of 96.85%, and a ferrous ion chelating capacity of 75.50%.The polysaccharides also showed significant inhibitory effects against

Salmonella enterica,

Salmonella thyphi,

Klebsiella pneumoniac,

Escherichia coli,

Micrococcus luteus,

and Staphylococcus aureus. Additionally, the IC₅₀ value for angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibitory activity was determined to be 0.29 mg/mL [

7]. Song et al. extracted two polysaccharides, ADPs40-F3 and ADPs60-F3, from baobab fruit powder (

Adansonia digitata) through a process of graded ethanol precipitation. At a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL, ADPs40-F3 and ADPs60-F3 exhibited DPPH radical scavenging rates of 68.32 ± 0.92% and 73.90 ± 0.73%, respectively. Their ABTS radical scavenging activities were 65.21 ± 0.55% and 75.73 ± 1.21%, while their FRAP reducing powers were 58.80 ± 0.84% and 63.41 ± 0.25%, respectively. At 5 mg/mL, ADPs40-F3 and ADPs60-F3 inhibited α-glucosidase by 76.22% ± 5.02% and 82.78% ± 2.02%, and α-amylase by 80.87% ± 2.80% and 86.94% ± 5.20%, respectively. In vivo mouse experiments revealed that the high-dose ADPs60-F3 group exhibited a substantial reduction in blood glucose levels, closely matching the effects of metformin. The decrease was approximately 44% at 60 minutes and 29% at 120 minutes, indicating notable anti-diabetic properties [

8]. To date, no domestic studies have reported on the structural characteristics or bioactivities of polysaccharides from baobab fruit that has been locally acclimatized in China.

This study systematically examined the physicochemical properties and biological activities of polysaccharides extracted from Adansonia suarezensis fruit pulp using various methods, including hot water, acid, alkaline, and ultrasound-assisted techniques. The aim was to provide a theoretical foundation for the potential application of Adansonia suarezensis fruit in pharmaceuticals and functional foods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

Adansonia suarezensis fruit pulp was obtained from Jubaolin Planting Professional Cooperative (Zhanjiang, Guangdong province, China).Monosaccharide standards including L-Ara, D-Man, D-Gal, D-GluA, D-Glu, D-GalA, L-Fuc, D-Xyl, Rha, along with pNPG (4-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside), were sourced from Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).α-glucosidase was sourced from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. in St. Louis, Missouri, USA. All reagents and chemicals utilized in this study were of analytical or chromatographic grade.

2.2. Preparation of ASPs

The shells of Adansonia suarezensis fruit were broken, and the pulp was separated from the shells. Subsequently, the pulp was ground, sieved through a 60-mesh, and dried. The powder was combined with distilled water, 0.1 M sodium hydroxide, and 0.1 M hydrochloric acid at a 1:25 (w/v) ratio, then processed using either hot water extraction with stirring at 65 °C for 1 hour or ultrasonic-assisted extraction at 350 W for 1 hour. After cooling, the mixtures were filtered through 200-mesh gauze to collect the supernatants. The pH of the supernatants from the acid and alkali extractions was adjusted to 7. The supernatants were vacuum-filtered and concentrated to 1/3-1/4 of their initial volume using a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure. Concentrates were mixed with five times their volume of absolute ethanol and stored at 4 °C for 12 hours to induce precipitation. The precipitates were collected by filtration through 200-mesh gauze, redissolved in water, and concentrated again by rotary evaporation to remove residual ethanol. The solutions underwent dialysis against water for 72 hours using a 3500 Da molecular weight cut-off bag. Finally, the contents were freeze-dried for 72 hours to obtain six polysaccharide samples: hot water-extracted polysaccharides (ASP-HW), acid-extracted polysaccharides (ASP-AC), alkali-extracted polysaccharides (ASP-AL), ultrasonic-assisted hot water-extracted polysaccharides (ASP-HWU), ultrasonic-assisted acid-extracted polysaccharides (ASP-ACU), and ultrasonic-assisted alkali-extracted polysaccharides (ASP-ALU).

2.3. Chemical Composition Analysis

Neutral sugar content was measured via the phenol–sulfuric acid method, using D-xylose as the standard [

9]. Contents of uronic acid were analyzed by the meta-hydroxydiphenyl method with galacturonic acid as standard [

10]. The protein content was determined by the Bradford method, using bovine serum albumin as the standard [

11]. The content of total phenolic was determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu method using gallic acid as the standard [

12].

The monosaccharide composition of ASPs was determined via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone (PMP) pre-column derivatization using an Arc HPLC system (Waters, USA) [

13]. A 2 mL sample solution (2 mg/mL) was combined with 2 mL of 4 M trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in an ampoule bottle, sealed, and hydrolyzed at 110 °C for 8 hours. After cooling, the mixture was evaporated to dryness using a rotary evaporator. To fully eliminate TFA, 1 mL of methanol was added and evaporated repeatedly for a total of six cycles. The residue was then redissolved in 2 mL of ultrapure water. Subsequently, 0.5 mL of the polysaccharide hydrolysate or standard solution was combined with 0.5 mL of 0.6 M NaOH and 1 mL of 0.5 M PMP methanol solution. The mixture was sealed and derivatized in a 70 °C water bath for 100 minutes. The solution was neutralized with 1 mL of 0.3 M HCl after cooling. The mixture was vortexed for extraction after adding 3 mL of chloroform. The lower chloroform phase was discarded. This liquid-liquid extraction step was repeated six times. The final aqueous phase was passed through a 0.22 µm microporous membrane filter before HPLC analysis. The analysis utilized an Agilent ZORBAX SB-C18 column (5 µm, 4.6 × 250 mm). The mobile phase, consisting of sodium phosphate buffer (0.02 M, pH 6.7) and acetonitrile (83:17, v/v), was run at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The temperature of the column was kept at 30 °C. The injection volume was 10 µL, and the detection wavelength was set at 250 nm.

2.4. Molecular Weight Determination (Mw)

HPGPC was employed to assess homogeneity and relative average molecular weight as described by Li et al. [

14].Samples at a 5 mg/mL concentration were filtered through a 0.22 μm aqueous microporous filter prior to analysis by HPGPC (U3000, Thermo, USA) with a RI detector and a BRT105–103-101 tandem gel column (8.0× 300 mm) (RID-20A, Shimadzu, Japan).Mobile Phase: 0.2 M NaCl; Flow Rate: 0.7 mL/min; Column Temperature: 40 °C; Injection Volume: 50 μL.

2.5. Particle Size Analysis

ASP samples were diluted to 1 mg/mL with deionized water, filtered through a 0.45 μm aqueous membrane, and analyzed for particle size using a NanoBrook Omni laser particle size and zeta potential analyzer (Brookhaven, USA) [

15].

2.6. Ultraviolet Analysis (UV)

An aqueous ASP solution with a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL was prepared for UV-Vis spectroscopy analysis. The absorbance spectrum was measured from 190 to 600 nm using a Cary 60 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent, USA).

2.7. Fourier Transform-Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) Analysis

FT-IR spectra (TENSOR27, Bruker, Germany) of the ASPs were acquired by the KBr pellet method, which involved mixing the sample with KBr at a 1:100 ratio, followed by thorough grinding, compression into a pellet, and scanning within the 4000–400 cm⁻¹ range.

2.8. The Congo Red Test

The triple-helical structure of ASPs was investigated using the Congo red method. A solution of ASPs at 1 mg/mL was combined with an equal volume of Congo red solution at the same concentration. Subsequently, varying amounts of 5 M NaOH solution were introduced to the mixtures to reach final concentrations of 0, 0.1 M, 0.2 M, 0.3 M, 0.4 M, and 0.5 M. After 30 minutes, the UV-Vis absorption spectra were measured between 400 and 600 nm, and the maximum absorption wavelengths (λ

max) were recorded. A Congo red solution mixture was used as the negative control, whereas the combination of curdlan and Congo red served as the positive control [

16].

2.9. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

A scanning electron microscope (JSM-7610F, JEOL, Japan) was used to examine the ASPs morphologically at 300x magnification. Before observation, the dried sample was secured to the stub with conductive adhesive, gently purged with a rubber bulb to remove excess powder, and subjected to gold sputtering.

2.10. Thermal Stability Analysis

The thermal stability of ASPs was assessed using a simultaneous thermal analyzer (SA449F3, Netzsch, Germany) as per the method outlined by Nawrocka et al. [

17] with minor modifications. Approximately 10 mg of the ASPs sample was placed in an alumina crucible. The measurements were conducted under a high-purity nitrogen atmosphere at a flow rate of 20 mL/min. Samples were heated from 40 °C to 500 °C at a constant rate of 10 K/min to assess degradation temperature and weight loss.

2.11. Antioxidant Capacities Analysis

(1) DPPH• scavenging activity

A 0.2 mM solution of DPPH in methanol was prepared. Then, equal volume of the sample solution and the DPPH solution was mixed. The mixture was allowed to react in the dark for 30 minutes. The absorbance at 517 nm was recorded as A₁. The absorbance of a mixture with equal volumes of ultrapure water and DPPH solution was measured as A₀ (control). The absorbance, A₂, of a mixture comprising equal volumes of the sample solution and absolute ethanol was measured as the sample background. L-Ascorbic acid served as the positive control. The DPPH radical scavenging activity of the samples was determined using formula (1) [

18].

(2) ABTS•+ scavenging activity

The ABTS•+ scavenging assay was performed as described by Gao et al. [

19], with slight modifications. A 7 mmol/L ABTS stock solution was combined with a 2.45 mmol/L potassium persulfate solution in a 1:1 ratio and stored in the dark for 12 hours to produce the ABTS working solution. The solution was diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) to achieve an absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm.1 mL of the sample solution at various concentrations was mixed with 4 mL of the diluted ABTS working solution. The reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 min, after which their absorbance at 734 nm was measured and recorded as A₁. The control absorbance (A₀), indicating the initial color of the ABTS radical, was determined by substituting the sample with ultrapure water. The background absorbance (A₂), reflecting the sample’s intrinsic color, was determined by substituting the ABTS working solution with PBS.L-Ascorbic acid served as the positive control. The ABTS radical scavenging activity was determined using formula (2).

2.12. α-Glucosidase Inhibition Activity

The α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was assessed using the method outlined by Tang et al. [

20] with slight adjustments. Briefly, 30 μL of sample solutions ranging from 0 to 1 mg/mL were combined with 30 μL of α-glucosidase solution at a concentration of 0.2 U/mL. The mixture was pre-incubated for 10 minutes, after which 30 μL of p-NPG solution (10 mmol/L) was added to initiate the reaction. Following a 15-minute incubation at 37 °C, the reaction was halted by introducing 100 μL of a 0.1 mol/L Na₂CO₃ solution. Absorbance was ultimately measured at 405 nm. Acarbose served as the positive control in the assay. A blank was prepared by replacing the α-glucosidase solution with PBS. The α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was determined using formula (3).

A1 represents the light absorption of the buffer solution, A2 denotes the light absorption of the α-glucosidase and p-NPG mixture, A3 indicates the light absorption of the ASPs solution, and A4 signifies the light absorption of the mixture containing ASPs, α-glucosidase, and p-NPG.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted on all data using SPSS software (version 27.0). Experiments were conducted in triplicate, and results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. A one-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Duncan’s and LSD tests for multiple comparisons. A significance level of p < 0.05 was established. Figures were generated using Origin software (version 2025).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Yields and Composition of ASPs

Table 1 compares the yields and fundamental chemical compositions of ASPs obtained through various extraction methods. The results indicated that extraction solvent significantly influenced the polysaccharide yield (

p < 0.05). Among the methods, ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction achieved higher yield of 62.5 ± 1.67%, while hot water extraction resulted in the lower yield of 50.5 ± 0.31%. Ultrasound treatment alone did not exhibit a significant influence on polysaccharides yield. Studies have revealed that acidic extraction can more effectively cleave glycosidic bonds in polysaccharides and increase the production of bioactive low-molecular-weight polysaccharides. Alkaline solutions disrupt hydrogen bonds between cellulose and hemicellulose in plants, facilitating the release and conversion of insoluble polysaccharides into soluble forms, thus increasing polysaccharide yield [

21]. Consequently, the polysaccharide yields obtained through acidic and alkaline extraction methods are significantly higher than those achieved via water extraction.

The six ASPs exhibited neutral sugar contents ranging from 19.15 ± 0.20% to 20.87 ± 0.69%, and uronic acid contents between 70.91 ± 0.3% and 79.93 ± 1.05%, indicating that all six polysaccharides are acidic. The total phenolic content varied from 2.98 ± 0.08% to 3.93 ± 0.07%, while the protein content ranged from 0.83 ± 0.03% to 4.17 ± 0.07%.

Among them, ASP-HWU and ASP-HW demonstrated higher neutral sugar and uronic acid contents (

p < 0.05). In contrast, ASP-AL and ASP-ALU showed lower uronic acid contents, but higher protein and total phenolic contents (

p < 0.05). The hydroxide ions in the alkaline solution likely cause the raw material’s cell walls to swell and disrupt component linkages, enhancing the dissolution of proteins and polyphenols [

22].Consequently, this process leads to a reduction in neutral sugar and uronic acid contents, which is consistent with observations reported for polysaccharides extracted from

Coreopsis tinctoria Buds [

23] and blackberry fruit [

24] using alkaline solutions.

The monosaccharide composition of ASPs was determined by PMP-HPLC method, and the results are presented in

Table 2. The findings reveal that all ASPs consist of galacturonic acid, xylose, arabinose, and galactose. Galacturonic acid was the most abundant monosaccharide, with a molar percentage ranging from 67.23% to 72.87%, followed by xylose at 12.26% to 15.82%. Galactose and arabinose were present in smaller quantities, with molar percentages ranging from 7.25% to 8.46% and 6.70% to 8.56%, respectively. The results align with the neutral sugar and uronic acid content, verifying that all ASPs are acidic pectic polysaccharides. Furthermore, different extraction methods only influenced the proportional composition of the individual monosaccharides without altering the types of monosaccharides present in the polysaccharides. This observation differs from the findings reported by Shen et al.[

8] and Maria et al.[

25], suggesting variations in the monosaccharide composition of baobab fruit from different geographical origins and varieties.

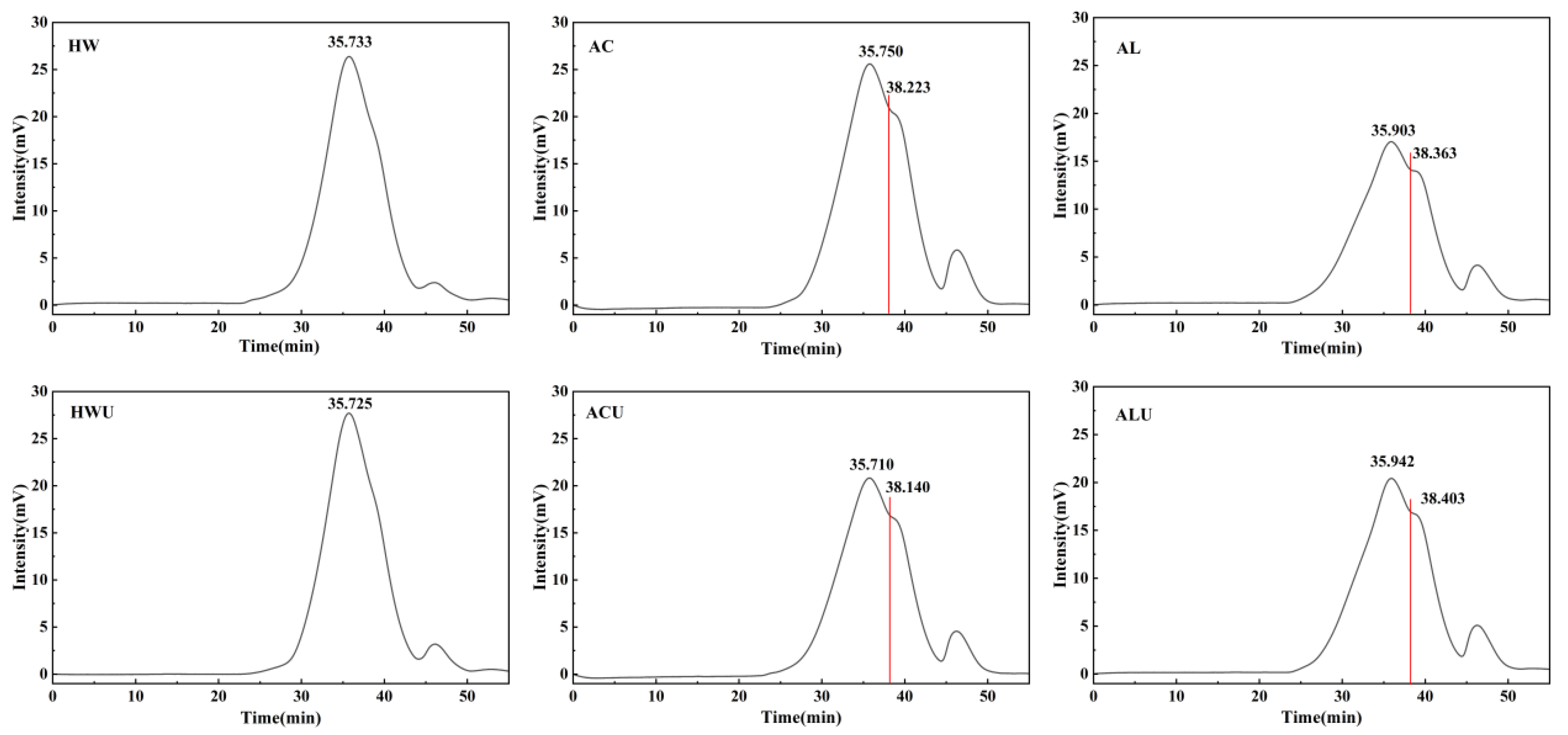

3.2. Molecular Weight Analysis

The weight-average molecular weights (Mw) of the ASPs, presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 1, followed a descending order: ASP-HWU (24,750 Da) > ASP-HW (24,686 Da) > ASP-ACU (20,997 Da) > ASP-AC (20,595 Da) > ASP-AL (19,813 Da) > ASP-ALU (19,600 Da). On the HPGPC chromatograms, ASP-HWU and ASP-HW exhibited symmetrical single peaks. In contrast, the acid and alkaline-extracted polysaccharides showed the presence of additional peaks corresponding to lower molecular weights, which is likely attributable to the cleavage of some polysaccharide chains by the acidic and alkaline solutions, resulting in shorter polymer chains. Based on the monosaccharide composition results, the ASPs are identified primarily as acidic pectic polysaccharides. Alkaline extraction is known to cause more severe disruption to the structure of pectic polysaccharides via β-elimination reactions [

26]. In contrast, acid extraction predominantly degrades neutral sugar side chains, while leaving esterified groups on the pectic polysaccharides relatively well preserved [

27]. As a result, alkaline-extracted polysaccharides exhibited lower molecular weights compared to those extracted with acid.

The polydispersity index (Mw/Mn) was 1.02 for both ASP-HWU and ASP-HW, while it ranged between 1.15 and 1.16 for the other ASPs. This indicates that although acid and alkaline extraction induced partial degradation of polysaccharide chains, the resulting extracts still displayed a relatively homogeneous molecular weight distribution.

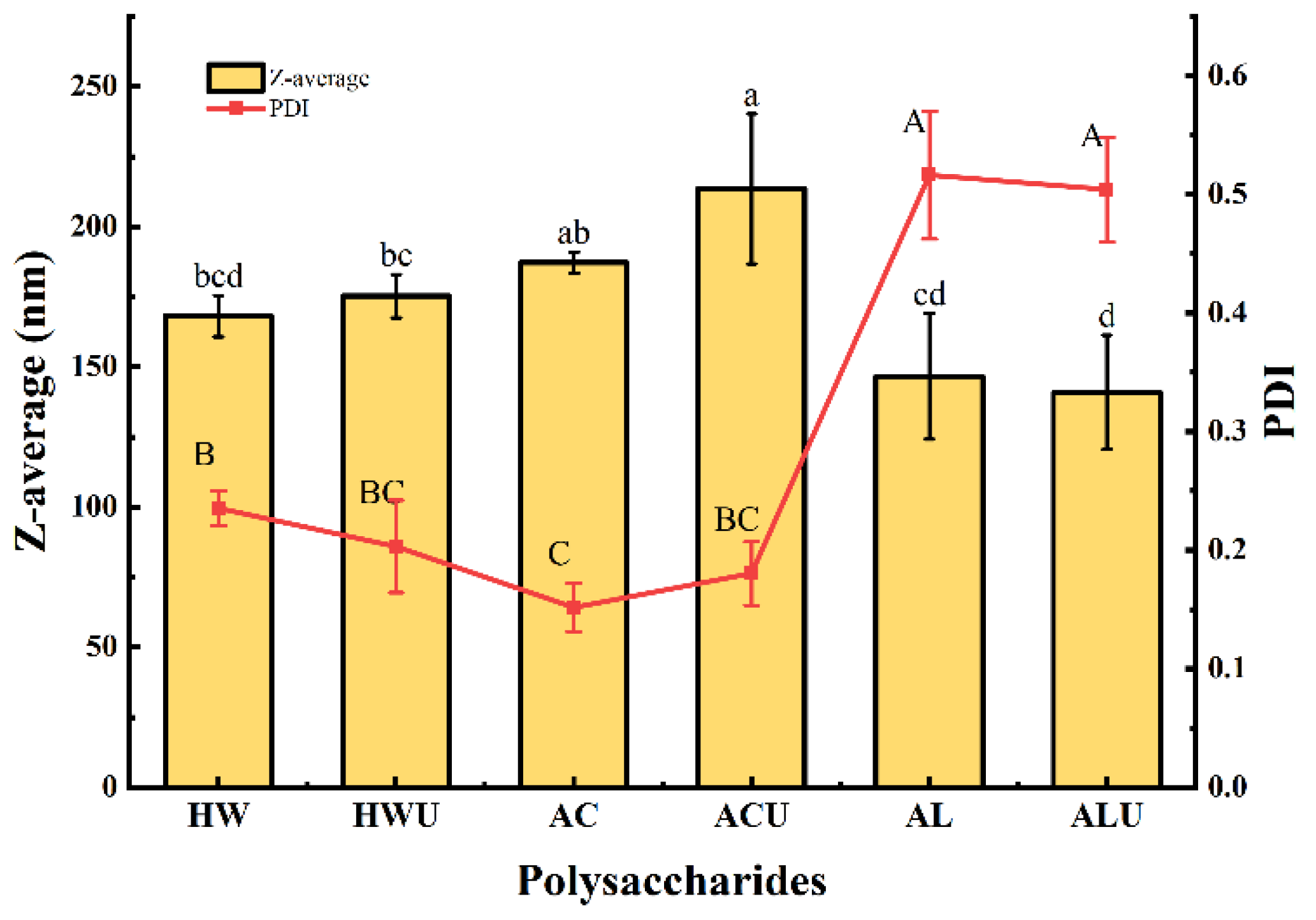

3.3. Particle Size Analysis

Polysaccharide particle size often correlates positively with molecular weight, providing an indirect measure of the latter. As shown in

Figure 2, the particle sizes of ASPs ranged from 140.97 ± 20.38 nm to 213.53 ± 26.73 nm.ASP-ACU and ASP-AC had particle sizes of 213.53 ± 26.73 nm and 187.20 ± 3.82 nm, respectively, which were significantly larger than the other ASPs (

p < 0.05). This observation is inconsistent with the molecular weight analysis results. A possible explanation is that the acid-extracted polysaccharides possess stronger intermolecular hydrogen bonding, facilitating increased molecular entanglement and aggregation, thereby forming larger polymeric assemblies [

24].Furthermore, ASP-ACU and ASP-AC also demonstrated the lowest polydispersity index, indicating a more homogeneous particle distribution in aqueous solution.

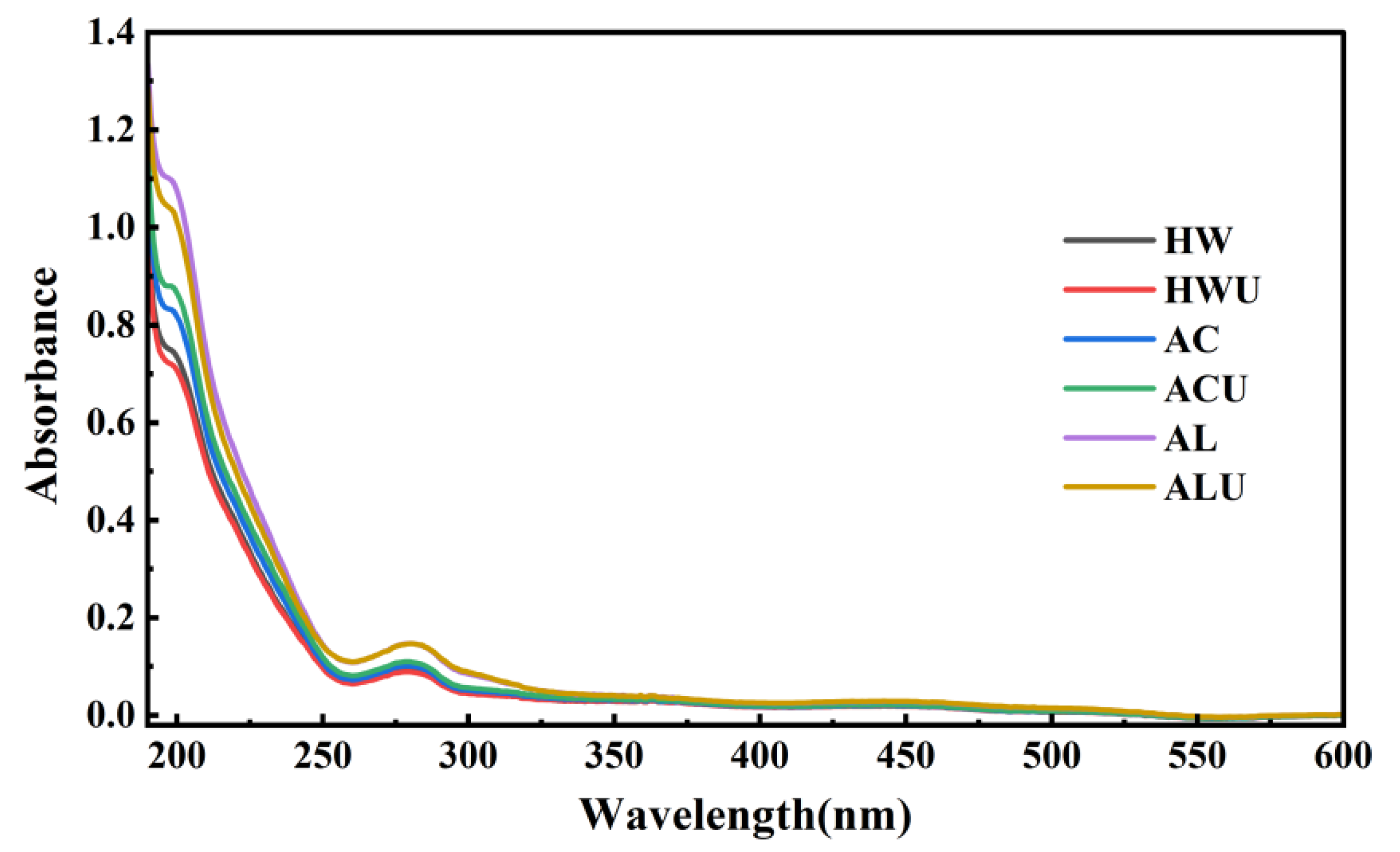

3.4. UV Analysis

Characteristic UV absorption peaks can indicate the presence of nucleic acids and proteins in polysaccharides. The UV scanning results of the ASPs are shown in

Figure 3. None of the ASPs solutions exhibited an absorption peak at 260 nm, indicating the absence of nucleic acids. In contrast, all samples showed absorption peaks at 280 nm with varying intensities. This observation is the same with the results from the quantitative protein content measurements, confirming the presence of proteins in the ASPs.

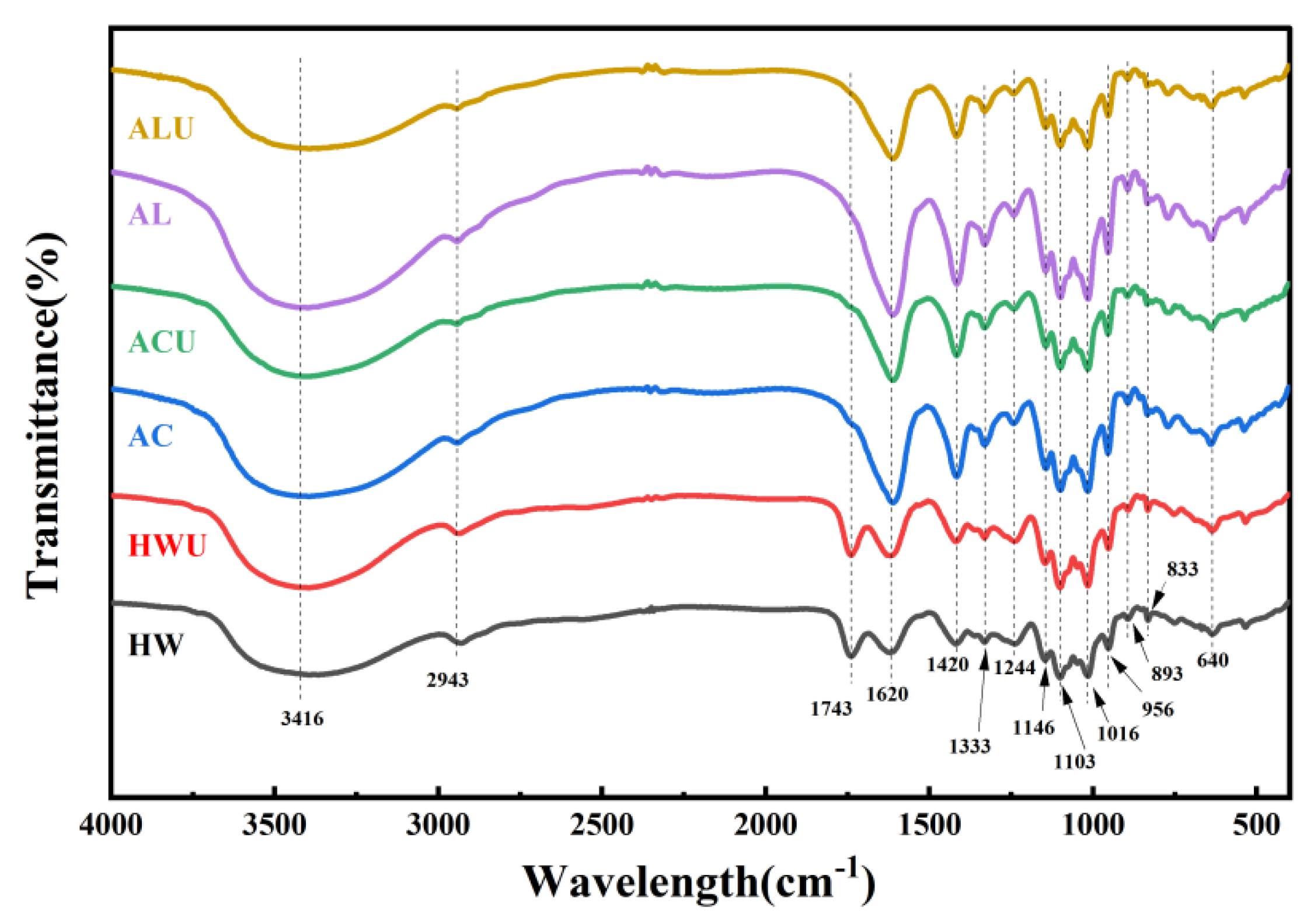

3.5. FT-IR Analysis

The characteristic functional groups of ASPs were analyzed through FT-IR spectroscopy.

Figure 4 demonstrates that the experimental results revealed characteristic polysaccharide absorption peaks for all ASPs within the 4000–400 cm⁻¹ range, with no notable shifts in functional groups. The peak at 3416 cm⁻¹ is linked to O-H stretching vibrations, whereas the peaks at 2943 cm⁻¹ and 1414 cm⁻¹ are associated with C-H stretching and bending vibrations, respectively [

28]. The absorption peak at 1743 cm⁻¹ in both ASPs-HW and ASPs-HWU is attributed to the symmetric stretching vibration of C=O in ester groups, suggesting esterification. The lack of this peak in alternative extraction techniques is probably due to the cleavage of ester bonds in alkaline conditions, leading to the reduction or loss of C=O vibrations from esterified carboxyl groups (-COOR) [

29]. The absorption peak at 1620 cm⁻¹ indicates carboxyl group deprotonation (COO⁻), while the -OH out-of-plane deformation vibration at 1333 cm⁻¹ verifies uronic acids in the ASPs [

30]. The 1244 cm⁻¹ peak, attributed to S=O stretching vibrations, signifies the presence of sulfate groups [

31]. The absorption peaks in the wavenumber range of 1200–1000 cm⁻¹ represent pyranose ring vibrations involving C-O stretching. The peaks at 1146 cm⁻¹, 1103 cm⁻¹, and 1016 cm⁻¹ are attributed to C-O-H and C-O-C stretching vibrations in the pyranose rings [

32]. The absorption bands at 956 cm⁻¹ and 640 cm⁻¹ indicate β-pyranose configurations in polysaccharides [

24]. The peak at 893 cm⁻¹ arises from the stretching vibration of β-glycosidic bonds, whereas the 833 cm⁻¹ peak is attributed to the stretching vibration of α-glycosidic bonds [

15].

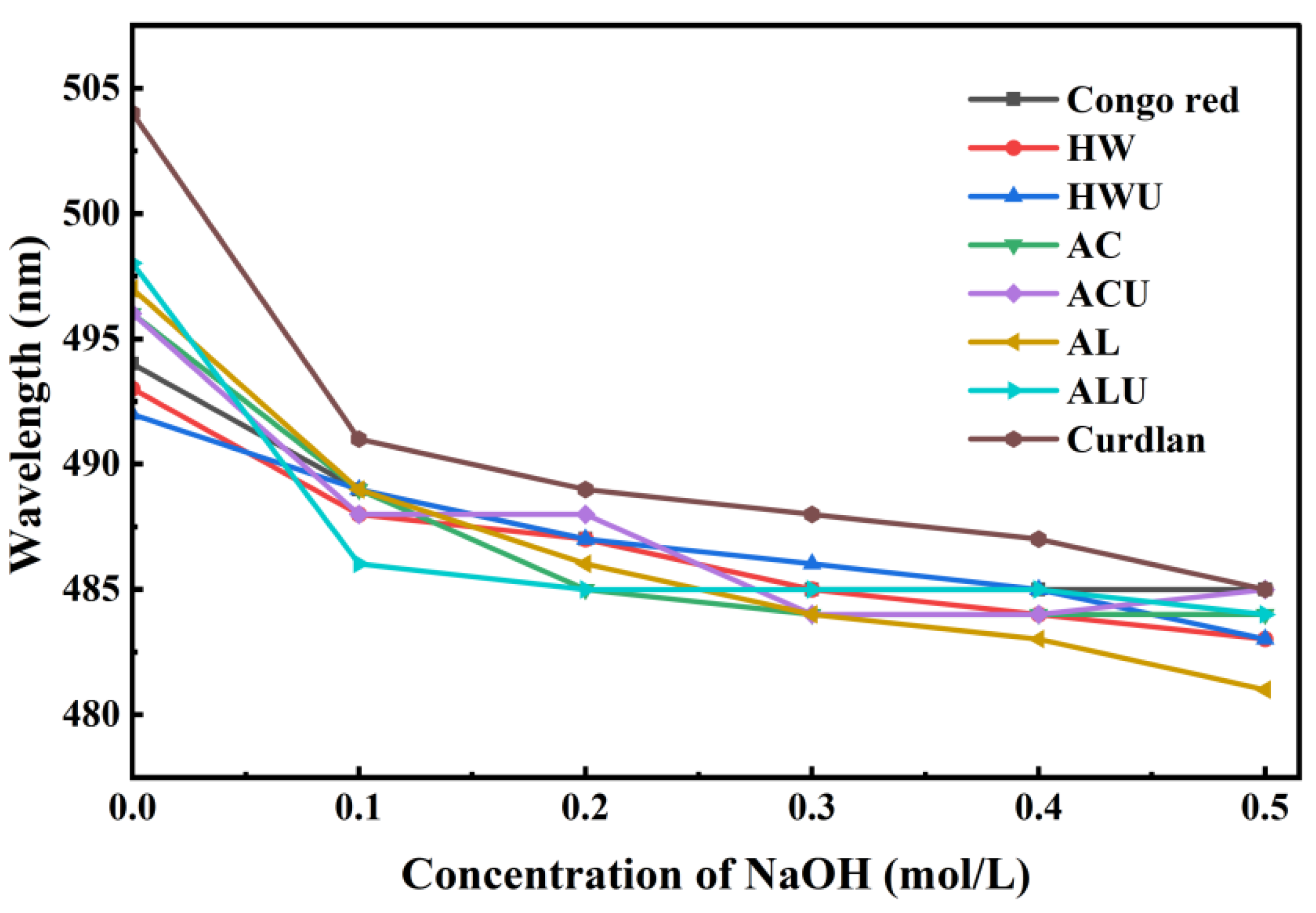

3.6. Conformational Analysis

The bioactivity of polysaccharides is significantly influenced by their triple-helical structure. A triple-helix structure is indicated by a bathochromic shift in the maximum absorption wavelength (λ

max) of the polysaccharide-Congo red complex relative to Congo red alone [

33]. However, as the NaOH concentration increases, the triple-helical conformation of polysaccharides can gradually transition to a single-coil form. This transition diminishes the interaction between polysaccharides and Congo red, resulting in a reduced observed λ

max.

Figure 5 illustrates the λ

max values as follows: positive control (curdlan) at 504 nm, ASP-AC at 496 nm, ASP-ACU at 496 nm, ASP-AL at 497 nm, and ASP-ALU at 498 nm. These wavelengths exhibit a notable red shift relative to the Congo red solution (494 nm), suggesting the existence of a triple-helix structure. The λ

max values for ASP-HW and ASP-HWU were 493 nm and 492 nm, respectively, indicating no red shift and suggesting the lack of a triple-helical structure in these polysaccharides. The triple helical structure of the polysaccharide remained stable in solution chiefly due to intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonds [

34]. Therefore, it is possible that the action of acid and alkaline solutions liberates more active groups, which promotes hydrogen bonding interactions between polysaccharide chains, thereby endowing ASP-AC, ASP-ACU, ASP-AL, and ASP-ALU with a triple-helix structure.

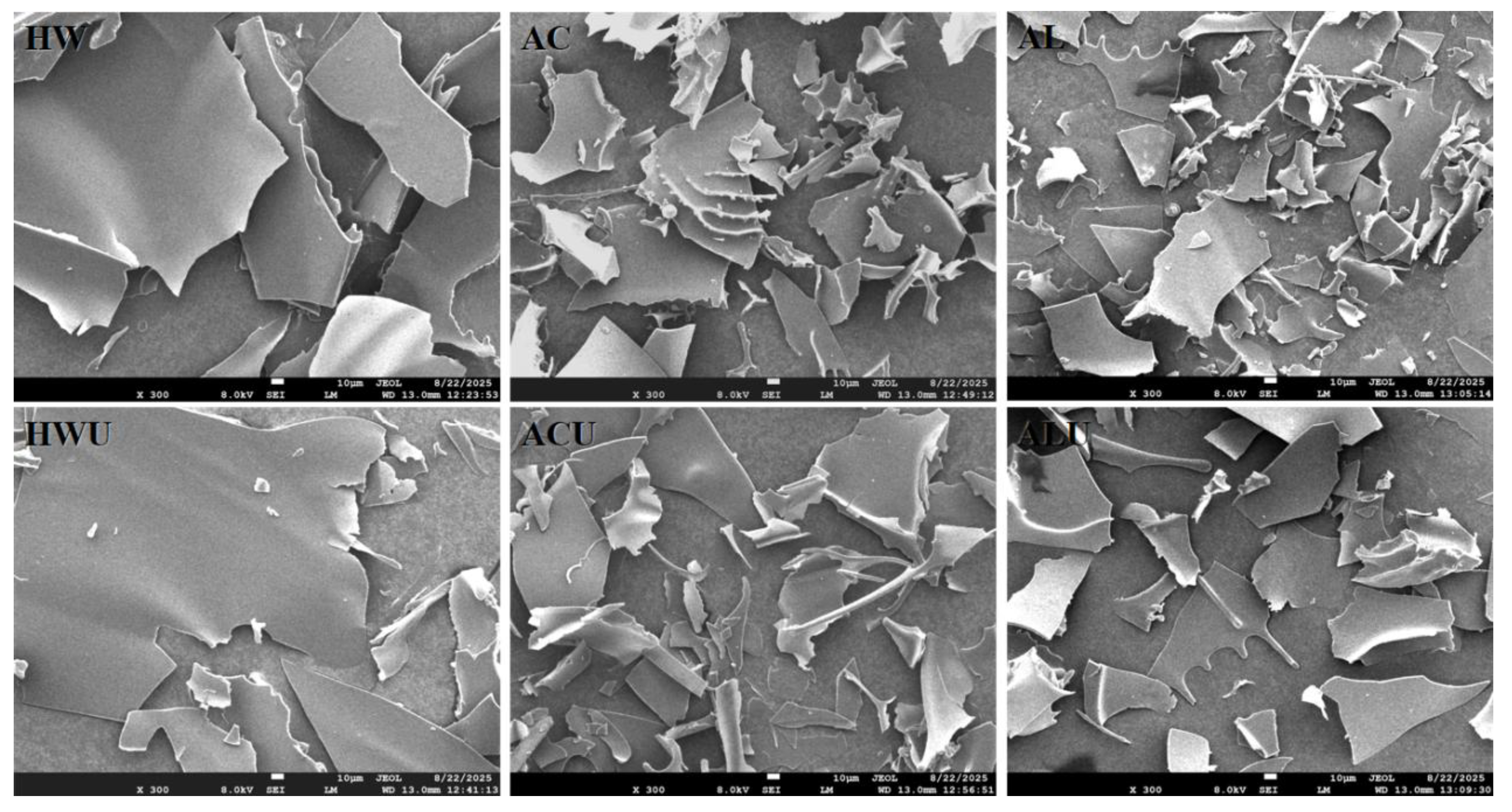

3.7. SEM Analysis

Figure 6 presents the SEM images of the ASPs.ASP-HW and ASP-HWU exhibited relatively smooth, dense, and irregular large flake-like structures. The flaky structure of ASP-AC and ASP-ACU appeared disrupted and loose, with irregular curls likely resulting from the cross-linking and aggregation of galacturonic acid [

24]. In contrast, the structures of ASP-AL and ASP-ALU also presented as flaky overall but were more fragmented and loose, also accompanied by a small number of irregular curls, attributable to the more severe degradation of uronic acid via β-elimination [

26].

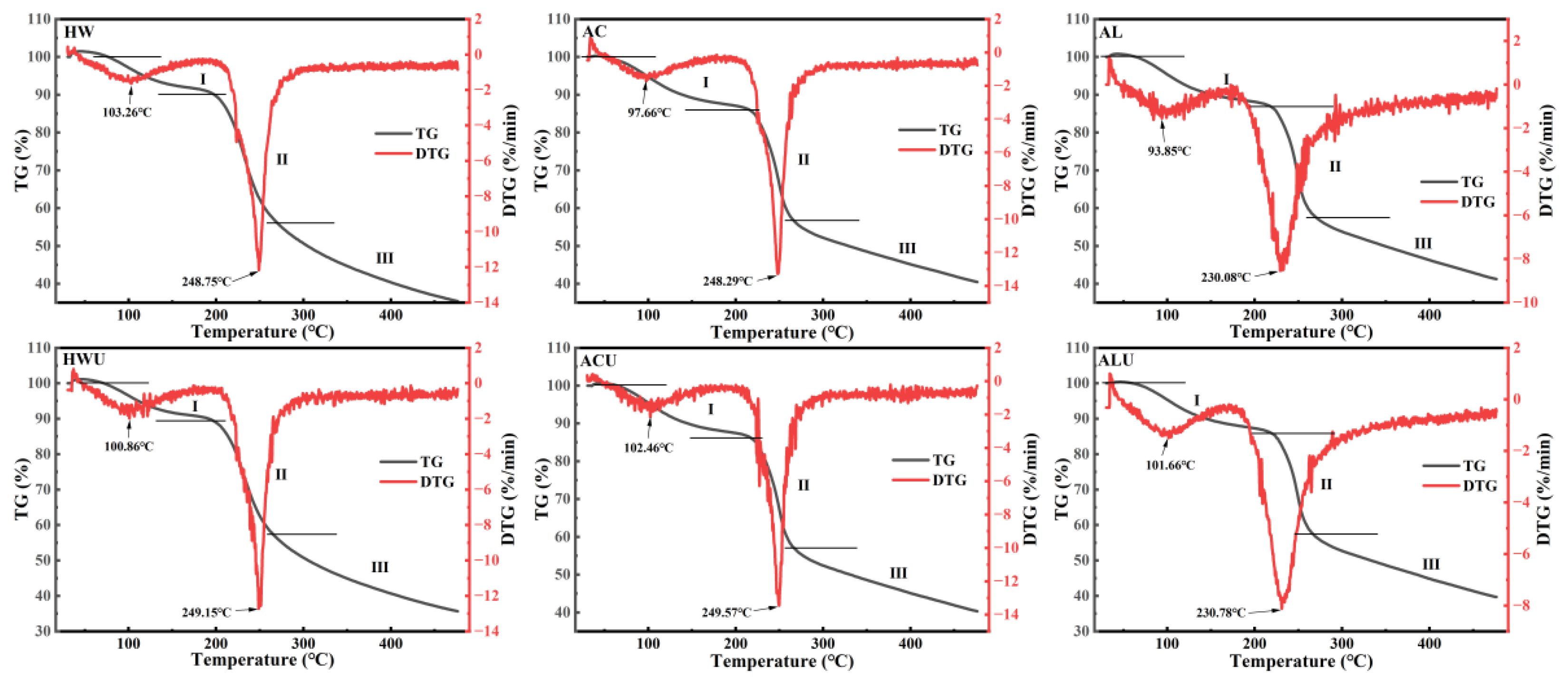

3.8. Thermal Stability Analysis

The thermal stability of ASPs was evaluated by TG and DTG curves measured from 30 to 500 °C, and the results were summarized in

Table 3 and

Figure 7. The TG curves indicated that the thermal decomposition of ASPs occurred mainly in three stages. The initial weight loss mainly results from the evaporation of both free and bound water in the polysaccharides [

35]. The weight reduction in the second stage likely results from the cleavage of glycosidic bonds and the degradation of polysaccharide side-chain residues [

29]. The third stage of weight loss is attributed to the fragmentation of depolymerized polysaccharide segments. During the initial phase, the weight losses were recorded as ASP-HW (9.89%), ASP-HWU (10.68%), ASP-AC (14.04%), ASP-ACU (13.84%), ASP-AL (13.13%), and ASP-ALU (14.15%).ASP-AL and ASP-ALU exhibited wider temperature ranges for this stage (ASP-AL: 30–219.65 °C; ASP-ALU: 30–219.98 °C), indicating their superior water-binding capacity.

DTG curves, derived as the first derivative of TG curves concerning temperature or time, illustrate the correlation between mass loss rate and temperature or time [

36]. The maximum mass loss rate temperature (T

max) serves as a key indicator of polysaccharide thermal stability, with a higher T

max generally reflecting greater thermal resistance [

37]. ASP-AL (230.08 °C) and ASP-ALU (230.78 °C) exhibited lower T

max values, likely due to the reduced galacturonic acid content in alkaline-extracted polysaccharides [

38], resulting in decreased intermolecular cross-linking and thermal stability.

3.9. Antioxidant Capacity Analysis

Figure 8 presents the antioxidant capacity of ASPs extracted via various methods, assessed using DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging assays. DPPH radical scavenging activity depends on the hydrogen-donating capacity of compounds [

35]. As shown in

Figure 8(A&A

1), ASP-AL and ASP-ALU demonstrated stronger DPPH radical scavenging capacity (

p < 0.05), with IC₅₀ values of 116.67 ± 0.58 μg/mL and 113.67 ± 2.31 μg/mL, respectively. Ultrasound assistance showed no significant effect on DPPH radical scavenging activity.

ABTS is a reagent widely used for in vitro evaluation of antioxidant capacity.

Figure 8(B&B

1) demonstrates that ASP-AL and ASP-ALU showed significantly higher ABTS radical scavenging activity (

p < 0.05), with IC₅₀ values of 79.67 ± 0.58 μg/mL and 79.33 ± 1.15 μg/mL, respectively, aligning with the DPPH radical scavenging findings. These findings indicate that alkaline-extracted polysaccharides possess superior antioxidant activity compared to those extracted with water or acid. This observation aligns with previously reported results for polysaccharides from

Coreopsis tinctoria buds [

23] and Sargassum [

15].

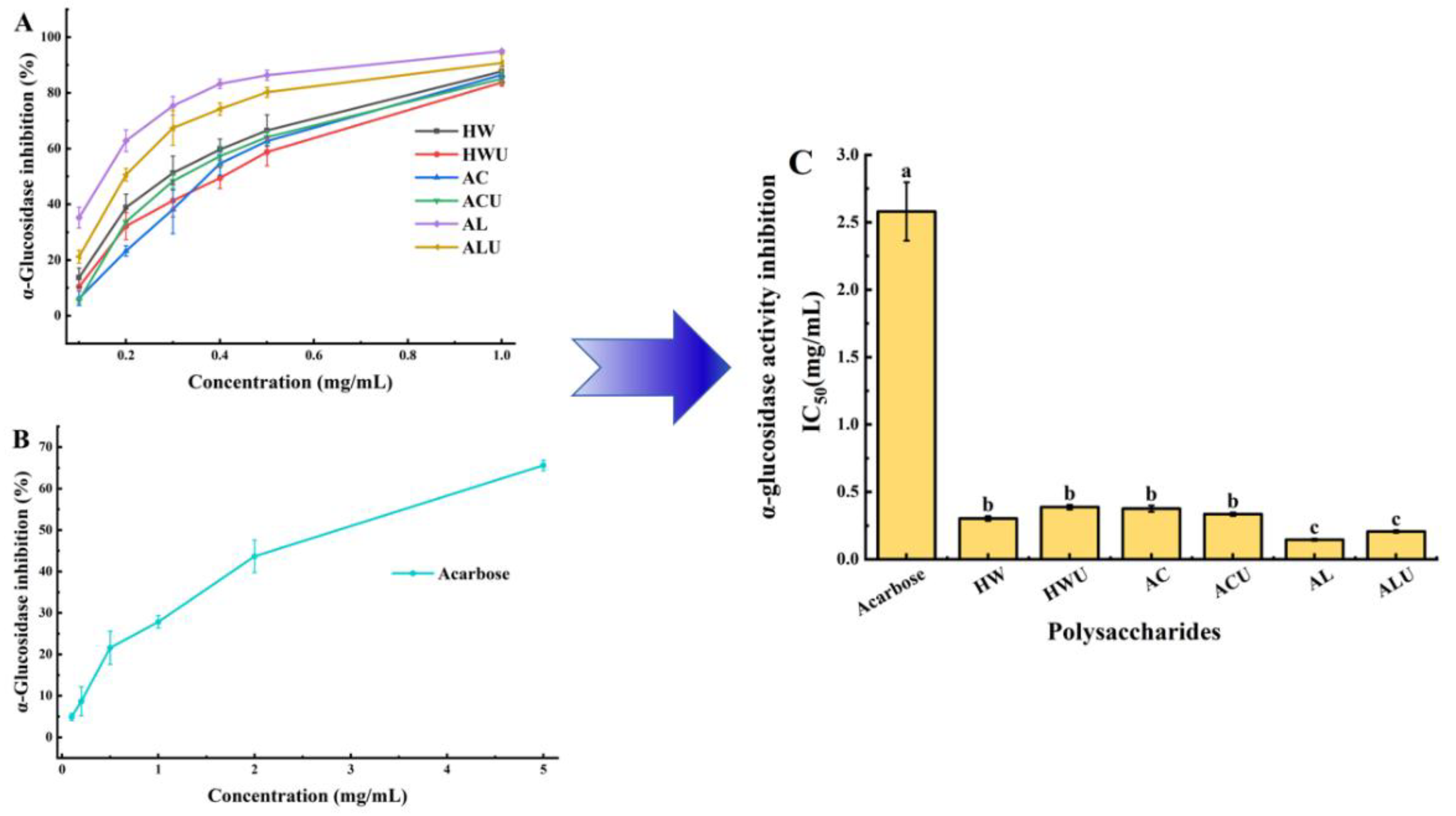

3.10. α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

Inhibiting α-glucosidase activity can delay glucose absorption and represents one of the most effective approaches for managing postprandial hyperglycemia [

39]. The α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of the ASPs are shown in

Figure 9.The IC₅₀ values of the six polysaccharides, ranked from lowest to highest, are: ASP-AL (0.146 ± 0.01 mg/mL), ASP-ALU (0.206 ± 0.01 mg/mL), ASP-HW (0.303 ± 0.02 mg/mL), ASP-ACU (0.335 ± 0.01 mg/mL), ASP-AC (0.376 ± 0.02 mg/mL), and ASP-HWU (0.388 ± 0.02 mg/mL). All ASPs demonstrated significantly stronger inhibition than the acarbose positive control group (2.58 ± 0.22 mg/mL) (

p < 0.05), indicating their considerable potential for development as therapeutic agents for type II diabetes.ASP-AL demonstrated superior α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, evidenced by its significantly lower IC₅₀ value compared to ASP-AC, ASP-ACU, ASP-HW, and ASP-HWU (p < 0.05). Ultrasound-assisted extraction showed no significant effect on α-glucosidase inhibitory activity (

p > 0.05).

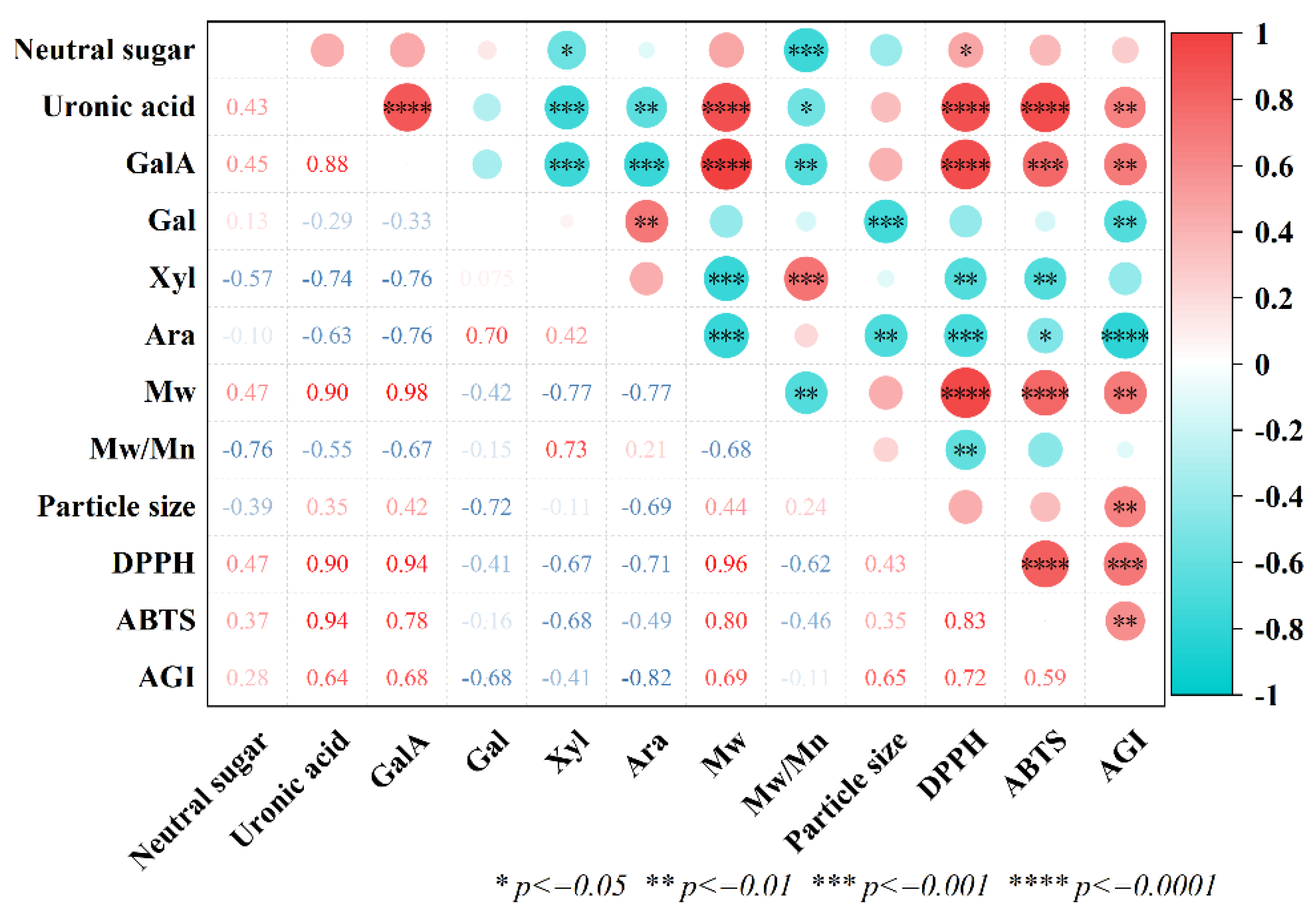

3.11. Correlation Analysis

To elucidate how the chemical structure of ASPs influences their bioactivity, a correlation heatmap was constructed as shown in

Figure 10. A positive correlation was observed between IC₅₀ values for DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging capacities, as well as α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, and uronic acid content, indicating that increased uronic acid content corresponded to reduced bioactivity. Alkaline treatment may enhance overall bioactivity by reducing total uronic acid content in polysaccharides, decreasing esterification, and increasing the RG-I domain proportion in neutral sugars [

26]. Additionally, IC₅₀ values for DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging, as well as α-glucosidase inhibition, positively correlated with molecular weight, suggesting that lower molecular weights enhance bioactivity.High-molecular-weight polysaccharides often result in increased viscosity, reduced water solubility, and unstable physicochemical properties, potentially restricting their absorption, utilization, and bioactivity. Low-molecular-weight polysaccharides exhibit weaker intramolecular hydrogen bonding and increased free hydroxyl groups, enhancing their bioactivity [

40]. In summary, the bioactivity of polysaccharides is closely linked to their chemical composition and molecular weight.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically evaluated the impact of various extraction methods—hot water, acid, alkaline, and ultrasound-assisted versions of these techniques—on the yield, chemical composition, structural characteristics, and bioactivity of polysaccharides derived from Adansonia suarezensis fruit pulp. The results demonstrated that ASP-ALU and ASP-AL achieved higher yields (62.47 ± 1.67% and 62.13 ± 0.31%, respectively), along with higher contents of total phenolics and proteins, but lower uronic acid content. The polysaccharides, consisting of galacturonic acid, galactose, xylose, and arabinose, are classified as acidic pectic polysaccharides. The alkaline-extracted polysaccharides exhibited smaller molecular weight and particle size and possessed a triple-helical conformation, which was absent in the hot water-extracted counterparts.ASP-AL and ASP-ALU exhibited superior bioactivity, notably in DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging, as well as α-glucosidase inhibition, surpassing other extraction methods and the positive control. Correlation analysis indicated that the bioactivity of ASPs improved with reduced uronic acid content and smaller molecular weight, enhancing antioxidant and anti-hyperglycemic effects. In summary, alkaline extraction efficiently yields bioactive polysaccharides from Adansonia suarezensis fruit pulp, offering a theoretical basis for their use in functional foods and pharmaceuticals.

Author Contributions

H.C.: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Software, Writing—original draft; S.G.: Methodology, Investigation, Software, Writing—review and editing; J.S.: Methodology, Investigation, Software; Y.P.: Methodology, Investigation, Software; P.H.: Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing; C.Z.: Methodology, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing—review and editing; J.L.: Methodology, Supervision, Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported financially by the Innovation and Development Project about Marine Economy Demonstration of Zhanjiang City (XM-202008-01B1).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pettigrew J.D., Bell K.L., Bell K.L., et al. Morphology, ploidy and molecular phylogenetics reveal a new diploid species from Africa in the baobab genus Adansonia (Malvaceae: Bombacoideae) [J]. TAXON, 2012, 61(6): 1240-1250. [CrossRef]

- Asogwa I.S., Ibrahim A.N., Agbaka J.I. African baobab: Its role in enhancing nutrition, health, and the environment [J]. Trees, Forests and People, 2021, 3: 100043. [CrossRef]

- Silva M.L., Rita K., Bernardo M.A., et al. Adansonia digitata L. (Baobab) Bioactive Compounds, Biological Activities, and the Potential Effect on Glycemia: A Narrative Review [J]. Nutrients, 2023, 15(9): 2170. [CrossRef]

- Members of the IUCN SSC Madagascar Plant Specialist Group & Missouri Botanical Garden. 2017. Adansonia suarezensis (errata version published in 2019). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T30389A145519699. [CrossRef]

- Benalaya I., Alves G., Lopes J., et al. A Review of Natural Polysaccharides: Sources, Characteristics, Properties, Food, and Pharmaceutical Applications [J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2024, 25(2). [CrossRef]

- Ji X., Guo J., Cao T., et al. Review on mechanisms and structure-activity relationship of hypoglycemic effects of polysaccharides from natural resources [J]. Food Science and Human Wellness, 2023, 12(6): 1969-1980. [CrossRef]

- Bougatef H., Tandia F., Sila A., et al. Polysaccharides from baobab (Adansonia digitata) fruit pulp: Structural features and biological properties [J]. South African Journal of Botany, 2023, 157: 387-397. [CrossRef]

- Song S., Abubaker M.A., Akhtar M., et al. Chemical Characterization Analysis, Antioxidants, and Anti-Diabetic Activity of Two Novel Acidic Water-Soluble Polysaccharides Isolated from Baobab Fruits [J]. Foods, 2024, 13(6): 912. [CrossRef]

- Li J., Shi H., Yu J., et al. Extraction and properties of Ginkgo biloba leaf polysaccharide and its phosphorylated derivative [J]. Industrial Crops and Products, 2022, 189: 115822. [CrossRef]

- Blumenkrantz N., Asboe-Hansen G. New method for quantitative determination of uronic acids [J]. Analytical Biochemistry, 1973, 54(2): 484-489. [CrossRef]

- Bradford M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding [J]. Analytical Biochemistry, 1976, 72(1): 248-254. [CrossRef]

- Csepregi K., Neugart S., Schreiner M., et al. Comparative Evaluation of Total Antioxidant Capacities of Plant Polyphenols [J]. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 2016, 21(2). [CrossRef]

- Xu C., Qin N., Yan C., et al. Isolation, purification, characterization and bioactivities of a glucan from the root of Pueraria lobata [J]. Food & function, 2018, 9(5): 2644-2652. [CrossRef]

- Li X.-J., Xiao S.-J., Xie Y.H., et al. Structural characterization and immune activity evaluation of a polysaccharide from Lyophyllum Decastes [J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2024, 278: 134628. [CrossRef]

- Zhou C., He S., Gao S., et al. Effects of Ultrasound-Assisted Treatment on Physicochemical Properties and Biological Activities of Polysaccharides from Sargassum [J]. Foods, 2024, 13(23): 3941. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y., Niu X., Liu N., et al. Characterization, antioxidant and hypoglycemic activities of degraded polysaccharides from blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum L.) fruits [J]. Food Chemistry, 2018, 243: 26-35. [CrossRef]

- Nawrocka A., Szymańska-Chargot M., Miś A., et al. Effect of dietary fibre polysaccharides on structure and thermal properties of gluten proteins – A study on gluten dough with application of FT-Raman spectroscopy, TGA and DSC [J]. Food Hydrocolloids, 2017, 69: 410-421. [CrossRef]

- Li J., Chen Z., Shi H., et al. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and properties of polysaccharide from Ginkgo biloba leaves [J]. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 2023, 93: 106295. [CrossRef]

- Gao S., Li T., Li Z.-R., et al. Gradient ethanol extracts of Coreopsis tinctoria buds: Chemical and in vitro fermentation characteristics [J]. Food Chemistry, 2025, 464: 141894. [CrossRef]

- Tang Y., He X., Liu G., et al. Effects of different extraction methods on the structural, antioxidant and hypoglycemic properties of red pitaya stem polysaccharide [J]. Food Chemistry, 2023, 405: 134804. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y., Hou S., Song S., et al. Impact of acidic, water and alkaline extraction on structural features, antioxidant activities of Laminaria japonica polysaccharides [J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2018, 112: 985-995. [CrossRef]

- Bai L., Zhu P., Wang W., et al. The influence of extraction pH on the chemical compositions, macromolecular characteristics, and rheological properties of polysaccharide: The case of okra polysaccharide [J]. Food Hydrocolloids, 2020, 102: 105586. [CrossRef]

- Gao S., Li W., Yin M., et al. A Comparative Study on Physicochemical Properties and Biological Activities of Polysaccharides from Coreopsis tinctoria Buds Obtained by Different Methods [J]. Foods, 2025, 14(7): 1168. [CrossRef]

- Dou Z.-M., Chen C., Huang Q., et al. Comparative study on the effect of extraction solvent on the physicochemical properties and bioactivity of blackberry fruit polysaccharides [J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2021, 183: 1548-1559. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulou M., Alba K., Sims I.M., et al. Structure and rheology of pectic polysaccharides from baobab fruit and leaves [J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2021, 273: 118540. [CrossRef]

- Zykwinska A., Rondeau-Mouro C., Garnier C., et al. Alkaline extractability of pectic arabinan and galactan and their mobility in sugar beet and potato cell walls [J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2006, 65(4): 510-520. [CrossRef]

- Yang J.-S., Mu T.-H., Ma M.-M. Extraction, structure, and emulsifying properties of pectin from potato pulp [J]. Food Chemistry, 2018, 244: 197-205. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Q., Jia R.-B., Luo D., et al. The effect of extraction solution pH level on the physicochemical properties and α-glucosidase inhibitory potential of Fucus vesiculosus polysaccharide [J]. LWT, 2022, 169: 114028. [CrossRef]

- Chen S., Qin L., Xie L., et al. Physicochemical characterization, rheological and antioxidant properties of three alkali-extracted polysaccharides from mung bean skin [J]. Food Hydrocolloids, 2022, 132: 107867. [CrossRef]

- Chen C., Wang P.-p., Huang Q., et al. A comparison study on polysaccharides extracted from Fructus Mori using different methods: structural characterization and glucose entrapment [J]. Food & function, 2019, 10(6): 3684-3695. [CrossRef]

- Chen L., Huang G. Antioxidant activities of sulfated pumpkin polysaccharides [J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2019, 126: 743-746. [CrossRef]

- Cheng H., Huang G. The antioxidant activities of carboxymethylated garlic polysaccharide and its derivatives [J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2019, 140: 1054-1063. [CrossRef]

- Xu X., Yan H., Zhang X. Structure and Immuno-Stimulating Activities of a New Heteropolysaccharide from Lentinula edodes [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2012, 60(46): 11560-11566. [CrossRef]

- Xiong F., Li X., Zheng L., et al. Characterization and antioxidant activities of polysaccharides from Passiflora edulis Sims peel under different degradation methods [J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2019, 218: 46-52. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Z., Wang L., Ruan Y., et al. Physicochemical properties and biological activities of polysaccharides from the peel of Dioscorea opposita Thunb. extracted by four different methods [J]. Food Science and Human Wellness, 2023, 12(1): 130-139. [CrossRef]

- Long X., Hu X., Xiang H., et al. Structural characterization and hypolipidemic activity of Gracilaria lemaneiformis polysaccharide and its degradation products [J]. Food Chemistry: X, 2022, 14: 100314. [CrossRef]

- Jiao X., Li F., Zhao J., et al. Structural diversity and physicochemical properties of polysaccharides isolated from pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata) by different methods [J]. Food Research International, 2023, 163: 112157. [CrossRef]

- Wang L., Zhao Z., Zhao H., et al. Pectin polysaccharide from Flos Magnoliae (Xin Yi, Magnolia biondii Pamp. flower buds): Hot-compressed water extraction, purification and partial structural characterization [J]. Food Hydrocolloids, 2022, 122: 107061. [CrossRef]

- Du X., Wang X., Yan X., et al. Hypoglycaemic effect of all-trans astaxanthin through inhibiting α-glucosidase [J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2020, 74: 104168. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z., Zhou X., Shu Z., et al. Regulation strategy, bioactivity, and physical property of plant and microbial polysaccharides based on molecular weight [J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2023, 244: 125360. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).