1. Introduction

In recent years, the transition toward a circular economy has become a central pillar of global strategies for sustainable development, especially with the new circular economy action plan [

2]. Within this framework, the valorization of agricultural and forestry residues represents a crucial opportunity to reduce waste generation, improve resource efficiency, and mitigate climate change.

Among the various nature-based and circular solutions, biochar, a carbon-rich material obtained through the thermochemical conversion (pyrolysis) of biomass has attracted increasing scientific and policy attention [

1]. Biochar application to soil has been associated with improved soil fertility, enhanced water retention, and long-term carbon sequestration, offering potential benefits for both agricultural productivity and climate mitigation [

3]. The present study aims to analyze the economic and environmental feasibility of implementing a local biochar production system as part of the redevelopment project of

Borgo di Perolla, in Tuscany, Italy, an abandoned area characterized by agricultural and forested land that produces significant amounts of residues and wood biomass. These materials were identified as potential feedstock for biochar production, offering an opportunity to implement a local circular system that combines waste valorization, carbon sequestration, and soil regeneration.

By applying a Cost–Benefit Analysis (CBA) across multiple production and market scenarios, the research investigates whether biochar can become a sustainable driver of circular regeneration at the territorial level. The results indicate that while biochar alone is not yet economically self-sufficient, its integration into carbon credit mechanisms, like the Voluntary Carbon Market and the EU Emission Trading System (ETS) can transform it into both environmentally and economically viable solution. The paper is structured as it follows: in

Section 2, a brief explanation of the study area and biochar is provided;

Section 3 describes the methodology and materials used for the analysis;

Section 4 presents all the results, and finally, the paper ends with

Section 5 with some concluding remarks

2. Background and the Area of Study

2.1. Biochar

Biochar is a carbon-rich material produced by heating biomass, such as wood, leaves, or manure, in conditions of limited or no oxygen. Its main feature is its high carbon content [

1]. As defined by the European Biochar Certificate (2024), biochar is a porous carbonaceous product derived from biomass pyrolysis and applied in ways that ensure long-term carbon storage or substitution of fossil carbon in industrial processes.

Pyrolysis is a thermochemical conversion process that enables the production of biochar from various waste materials. As previously described, it involves the decomposition of organic matter through high-temperature heating, typically between 250°C and 900°C [

4]. During pyrolysis, biomass undergoes decomposition, depolymerization, and condensation reactions.

According to Ahmed et al. (2024)[

5], as temperature increases, the water contained in the biomass is converted into vapor, initiating a dehydration phase that reduces the moisture content and consequently the mass of the feedstock. Subsequently, the biomass is transformed into biochar through the loss of its volatile components [

5].

Pyrolysis generates three product streams in solid, liquid, and gaseous form: biochar (solid), bio-oil or wood vinegar (liquid), and syngas (gas). Depending on temperature, heating rate, and feedstock characteristics, pyrolysis can be classified into slow, fast, or intermediate regimes [

6].

Biochar is applied across multiple sectors, including agriculture, construction, wastewater treatment, and livestock management, thanks to its physicochemical properties and environmental benefits.

Agriculture represents the most established field of biochar application. According to Lehmann (2007) [

3], biochar is primarily used to: enhance agricultural productivity, mitigate environmental pollution, restore degraded soils, and sequester atmospheric carbon. Its properties, such as high porosity and alkaline pH, improve soil fertility, water retention, nutrient availability, and microbial habitat quality [

7]. Biochar also adsorbs pollutants and heavy metals, aiding soil remediation [

8].

Biochar contributes significantly to carbon sequestration due to its chemically stable carbon fraction, which can persist in soils for centuries to millennia [

9,

10]. The pyrolysis process further prevents carbon from returning to the atmosphere, enabling long-term CO₂ removal of approximately 2–3 t CO₂ per ton of biochar [

11]. This function makes it a key strategy in climate mitigation.

2.2. Borgo Perolla and the Redevelopment Project

Borgo di Perolla is located in the inland area of the municipality of Massa Marittima, in the province of Grosseto, within the Tuscan Maremma region. The study area covers approximately 1,300 hectares, including an extensive forest complex of more than 1,000 hectares, as well as agricultural plots comprising vineyards, olive groves, chestnut groves, and pastures. The site is characterized by high biodiversity, landscape, and a notable cultural and architectural heritage, partly compromised by a prolonged period of neglect and abandonment.

Over recent decades, the entire estate has undergone substantial degradation, resulting in the progressive loss of ecological, productive, and landscape functions: the forest has not been actively managed, agricultural activities have been gradually abandoned, and many historical buildings have deteriorated. This situation has generated the need for an intervention aimed at environmental, agricultural, and structural restoration.

The main issues identified through the forest assessment and field inspections include the absence of sustainable forest management, leading to risks of biodiversity loss and instability of local ecosystems; the deterioration of rural and historical infrastructure; the abandonment of traditional cultivations, with olive groves and vineyards showing low or no productivity; and the need to implement restoration measures grounded in environmental sustainability, integrating agroecological, forestry, and circular approaches. These findings derive from a confidential report prepared by experts involved in the site inspections.

In response to these challenges, the owners of Borgo di Perolla started a regeneration project conceived as an integrated sustainable development intervention, with the aim of enhancing the area from both environmental and socio-economic perspectives. Complementing this broader sustainability project, the present research investigates the economic feasibility of implementing a biochar production system using branches and woody residues from the estate. The aim is to define a circular economy strategy that ensures not only the efficient reuse of residual biomass but also access to the biochar market and the voluntary carbon credit market, while highlighting the environmental and climate benefits of the material.

In summary, the Borgo di Perolla initiative represents a coordinated set of environmental, agricultural, and cultural restoration measures that contribute to the ecological transition of marginal rural areas, fostering sustainable and long-lasting environmental, social, and economic development.

3. Materials and Methods

The research employed a Cost–Benefit Analysis (CBA) to evaluate the economic and environmental feasibility of establishing a biochar production system for a period of 20 years. Data collection involved both primary and secondary sources to ensure analytical robustness. Primary data were obtained through direct fieldwork, including site visits, interviews, and discussions with agronomists, and sustainability experts involved in the project. Secondary data were gathered from scientific literature and policy reports, focusing on biochar production technologies, and carbon credit markets.

Three main scenarios and one sensitivity analysis were designed to test the project’s feasibility under different technical and market conditions. Scenario 1 included the production and sale of biochar and wood vinegar as the sole sources of revenue. Scenario 2 added potential revenues from the sale of voluntary carbon credits. Scenario 3 simulated the inclusion of biochar credits within the European Union Emission Trading System after the fifth year. Finally, Scenario 4 provides a brief in-depth analysis of a possible development of Scenario 3, considering exclusively the use of residual biomass, without resorting to resources from the logging plan. Each scenario incorporated two distinct assumptions regarding production capacity, considering either the operation of three production units or five production units, as this was the condition provided by the suppliers of the units.

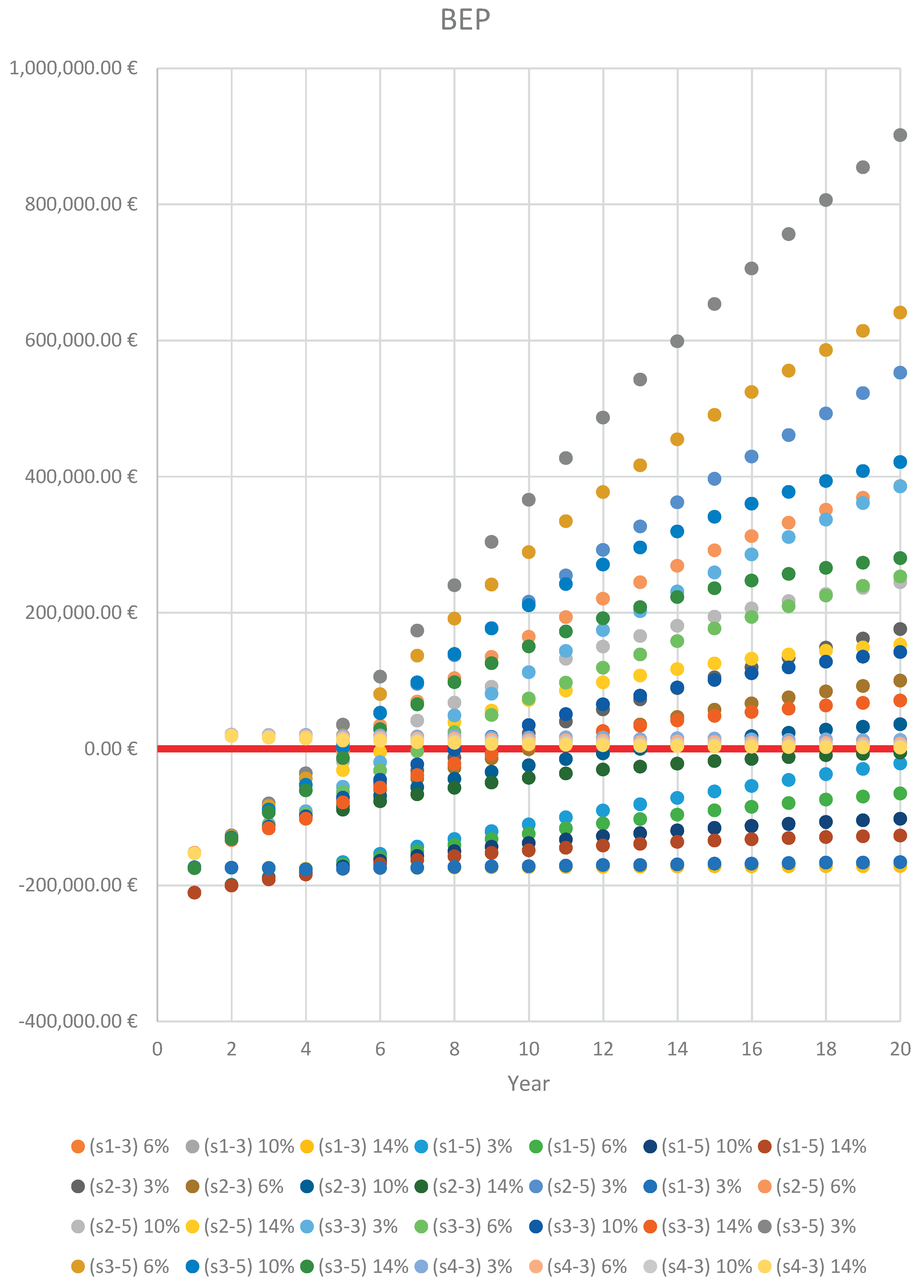

Economic feasibility was assessed using three indicators, including the Net Present Value (NPV), the Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and the Break-Even Point (BEP). For each scenario, 4 discount rates (3%, 6%, 10% and 14%) were applied to improve the robustness of the analysis.

3.1. Cost

Biomass pre-processing and mobile pyrolysis units are evaluated for biochar and wood-vinegar production using 3- and 5-unit configurations. Each option entails different biomass requirements, opportunity costs, and labor needs. Fixed expenditures include scientific consulting, operational support, and project management.

Table 1 outlines all first-year costs for each scenario.

3.2. Benefits

The benefit assessment considers revenues from biochar, wood vinegar, and biochar-derived carbon credits. Owing to substantial market volatility and limited transparency, price estimates were based on published studies, expert consultations, and supplier comparisons. For the CBA, conservative mean values were adopted.

Beginning with biochar, its market price exhibits substantial variability and is currently difficult to define with precision [

12]. In some cases, it may reach values ranging between €1,000 and €1,500 per ton [

13]. This variability is largely attributable to the fact that biochar markets are not yet fully consolidated and remain characterized by considerable uncertainty with respect to their future development. A robust assessment of the profitability of biochar-related markets would require an updated and publicly accessible database of sale prices [

14]. However, unlike other commodities, such information is not currently publicly available [

14]. A further factor contributing to price fluctuations is the diversity of the product’s physicochemical characteristics and the wide range of uses and potential markets [

14].

For the purposes of the present analysis, based on the data previously collected and discussed with biochar representatives, it was possible to identify a realistic price range between €200/t (minimum value) and €500/t (maximum value). Accordingly, a mean value of €300/t was adopted for the cost–benefit analysis (CBA) across all scenarios.

A similar issue concerns wood distillate (or wood vinegar). Despite its growing popularity and the numerous potential applications across various sectors, a substantial research gap persists. In particular, there is a lack of quantitative analyses capable of providing a comprehensive overview of wood vinegar [

15]. The price selected for the CBA (across all scenarios) is €180, chosen within a broader range of €100 (minimum value) to €200 (maximum, but variable value) based on comparisons of major Italian suppliers and producers of wood distillate.

Scenario 2 and 3 incorporate additional benefits from participation in the voluntary carbon market and ETS, where certified biochar is assumed to sequester 1.5 t CO₂-eq per ton applied. Over the past four years, prices of biochar-derived carbon credits (BCR

1) have experienced significant growth, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR

2) of 29.2% [

16]. Although future price trends cannot be predicted with certainty, market dynamics indicate sustained upward pressure. Global demand for CO₂ removal solutions via biochar is accelerating rapidly, while supply remains limited. This imbalance is expected to intensify in the medium term as an increasing number of companies strive to meet net-zero commitments. In 2024, prices for biochar carbon credits ranged from

$113 to

$310 per ton of CO₂ (i.e., per credit), with a weighted average price of

$165 [

16]. Also, the value of one ton of CO₂ equivalent from biochar was estimated at

$131 in 2023 and

$212 in 2022 [

17] with a price range between

$42 and

$250 per ton, with higher values primarily associated with the co-benefits of biochar, including support for local community development, biodiversity conservation, job creation, and other positive impacts [

17].

Considering these data, a mean price reflecting current values within the voluntary carbon market was selected for the feasibility analysis. Thus, one carbon credit generated from biochar is assigned to a value of €150.

Table 2 report the reference prices used in the CBA.

3.3. Scenario 3 Data

Scenarios 1 and 2 consist of direct applications of a CBA using the data previously described. Scenario 3, however, requires formulating a CBA that incorporates a potential increase in the value of biochar-derived carbon credits, assuming that such credits become eligible within the mandatory Emissions Trading System (ETS).

Integrating these carbon credits into the ETS would represent a major opportunity for producers of this form of carbon removal, and this possibility is currently under discussion.

Inclusion in the ETS could further raise their price. If biochar credits were accepted within the emissions trading system, demand would increase because companies would be required to offset their emissions, leading to a substantial rise in credit prices (which would also be influenced by the price and availability of other allowances). Moreover, if biochar were integrated into the EU ETS, it could help stabilize carbon prices and prevent excessively rapid increases. Given its low cost, biochar could also help contain allowance-price inflation and maintain greater market stability. Additionally, biochar credits may be particularly valued within the ETS, as they ensure long-term carbon sequestration in soils [

20].

ETS allowances are currently traded at variable prices between €60 and €80 per ton of CO₂. In 2024, the average recorded price was approximately €64.74 [

21]. ETS allowance prices may reach €149 per ton by 2030, indicating a potential increase of more than 130% in five years [

22].

In light of these projections, and assuming that biochar credits (BCR) are incorporated into the ETS, a conservative estimate was adopted for Scenario 3: an 80% increase in carbon-credit value by the fifth year (2030), corresponding to the assumed date of entry into the EU ETS. Thus, if the voluntary-market value of biochar carbon credits is €150/t, their price would rise to €270/t from the fifth year onward.

To strengthen the analysis, the same scenario was also developed using the average ETS allowance price for the period 2021–2025. This average price—calculated using daily ETS price data from Mazzarano et al. (2024) [

23] is approximately €70/t. For completeness, the scenario was further examined in the appendix using the minimum (€33/t) and maximum (€98/t) ETS prices recorded in the 2021–2025 period. The effects of these price variations are discussed in the following chapter.

If a hypothetical CBA were developed considering only waste resources, the data would change. From the fifth year onward, biochar production would have to be limited to the 300 tons of waste biomass available on the estate, avoiding the use of timber from the harvesting plan, as previously assumed. Based on this decision, and given the reduced biomass availability, the pyrolysis cycles would need to be decreased, making it reasonable to operate only three mobile units. The analysis would therefore assume the purchase and use of only three pyrolysis machines.

However, as previously noted, the biomass required to sustain a full annual production cycle for three units (230 cycles) would require an additional 155 tons of residues beyond the 300 tons available. Consequently, starting from the fifth year, working cycles would need to be reduced to 151, matching only the available waste biomass, resulting in an opportunity cost of €0 (due to the absence of foregone timber sales). With fewer cycles and working days, labor costs would decrease to €13,366.52 per year. However, reduced machine utilization and lower biomass inputs would also result in reduced production of biochar, wood vinegar, and carbon credits (Scenario 4).

4. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4.1. Subsection

The analysis of NPVs (

Table 3) across the scenarios reveals significant differences. Scenario s3-5 emerges as the most economically favorable, with a positive NPV even at the highest discount rate (i = 14%), reaching approximately 280,000 €, and nearly 902,000 € at i = 3%. Scenario s3-3 confirms this trend, yielding positive NPVs under all assumptions and demonstrating economically sustainable outcomes, although slightly lower than those with five machines.

Scenarios s2-5, s2-3, and s4-3 show good profitability at lower discount rates, but NPV declines with increasing discount rates, turning slightly negative at i = 14%. Conversely, scenarios s1-3 and s1-5 consistently show negative NPVs, indicating economic unsustainability. These scenarios, based solely on biochar and wood distillate sales, are therefore not financially viable.

IRRs (

Table 4) are positive in all scenarios except s1-3, which also exhibits a negative NPV, confirming its economic infeasibility. Higher IRRs are observed in scenarios where biochar is integrated into the voluntary carbon market and ETS (s2-3, s2-5, s3-3, s3-5, and s4-3). These results highlight the potential of carbon market instruments to make high-environmental-impact technologies economically attractive, despite requiring substantial initial investments. Access to emissions reduction financing thus represents a critical factor for unlocking solutions such as biochar, capable of generating significant economic returns while contributing to mitigation goals.

Results in

Figure 1 indicate that scenarios s2-5, s3-3, and s3-5 are the most efficient, reaching breakeven point quickly with minimal sensitivity to interest rate increases. These findings support the notion that integrating biochar into carbon markets (voluntary or ETS) enhances both economic returns (NPV, IRR) and the speed and stability of investment recovery.

Overall, Scenario 1 (biochar and wood distillate only) is not sufficient for economic sustainability, whereas access to voluntary carbon markets (Scenario 2) or integration into the EU ETS (Scenario 3) substantially improves profitability. Scenario s2-5 demonstrates the advantage of higher production capacity combined with market diversification, while Scenario 3 shows that increased carbon credit value within the ETS from the fifth year allows rapid BEP recovery and sustained positive returns.

Scenario 4, which considers biochar production exclusively from waste, also yields promising results, demonstrating that resource recycling and minimizing environmental impact can support economic sustainability. Limiting production to waste reduces physical output but significantly lowers operational costs, maintaining or even enhancing profitability through carbon credit valuation. This approach exemplifies circular economy principles, prioritizing input-output efficiency over maximum production, and fostering resilient, equitable, and environmentally harmonious long-term production models.

3.3. Sensistivity Analysis for Scenario 3

The project scenario 3 was developed also considering the average ETS credit price over 2021–2025 (70 €/t) and assuming an 80% increase from the fifth year (126 €/t), shows similar results [

Table 5]. The NPV is positive for both configurations (s3-3 and s3-5) across all discount rates, except for scenario s3-3 with three machines and discount rates of 10% and 14%, where the breakeven point is not reached.

Regarding the IRR [

Table 6], scenario s3-3 presents a value of 8%, while scenario s3-5 reaches 19%. In both cases, the IRR exceeds the applied discount rates (with the exception of i = 10% and i = 14% in s3-3), confirming the economic feasibility of the project even when adopting an average ETS credit price.

The breakeven point for scenario s3-3 is achieved in the thirteenth year with a discount rate of 3% and in the seventeenth year with a rate of 6%, indicating a slight delay compared to the same scenario calculated with a carbon credit price derived from biochar of 150 €. For scenario s3-5, the breakeven point occurs in the seventh year with i = 3%, in the eighth year with i = 6%, in the ninth year with i = 10%, and in the eleventh year with i = 14%.

With the minimum ETS price, positive results are obtained only for the s3-5 configuration, indicating that investment recovery is possible only when five machines are employed, and for discount rates of 3%, 6%, and 10%. Conversely, with the maximum ETS price, all NPVs are positive except for s3-3 with i = 14%. In all other cases, the IRR exceeds the discount rates applied.

The timing of breakeven varies considerably. Under the maximum ETS price, the breakeven is reached quickly for all discount rates, whereas under the minimum price with the s3-3 configuration, it is never achieved. This highlights how investment profitability is strongly influenced by external factors, particularly ETS credit prices, which in turn are linked to international market trends, geopolitical conflicts, technological innovations, and public policies. Therefore, investment risk increases due to uncertainties in these external factors, which are not captured by quantitative cost-benefit analysis alone.

Further details of the analysis using minimum and maximum ETS prices are provided in the

Appendix A.

4.2. Replicability of the Analysis

For replicability in similar agricultural contexts,

Table 7 presents NPV per hectare for each scenario, including variations based on ETS credit prices. Borgo Perolla encompasses 35 hectares for biochar biomass production.

These results further indicate that entering both voluntary carbon markets and the ETS is crucial to achieving investment profitability. In particular, scenarios s1-3 and s1-5 consistently show negative values, suggesting the economic unsustainability of the investment. In contrast, scenarios s2-5 and s3-5 exhibit the highest NPV per hectare, maintaining positive returns even at higher discount rates, which highlights these as economically more robust scenarios. This demonstrates that, in terms of per-hectare profitability, market instruments, such as voluntary markets and ETS, combined with increased production capacity (five machines) make this high-impact environmental technology economically attractive, allowing for substantial profit generation.

Scenario s3-3 is particularly sensitive to ETS credit prices. With the maximum price, the NPV per hectare remains positive up to a 10% discount rate, whereas with the minimum price, it becomes negative in all cases. Even with the maximum price, NPV per hectare turns negative at discount rates of 10% and 14%.

This implies that at an ETS price of 33 € (minimum price), the revenues generated are insufficient to cover investment costs, resulting in economic losses per hectare. Furthermore, as the discount rate increases, the negative values worsen, indicating a diminished capacity of the investment to generate value over time. A similar situation arises when using an ETS price of 70 € (average price) with discount rates of 10% and 14%, which remain high and profitable only over the long term.

These per-hectare NPV results demonstrate that, even when biochar is recognized within the ETS system, the market does not always ensure the economic sustainability of the initiative. Therefore, it is essential to carefully evaluate and continuously monitor ETS market price fluctuations along with other external factors that may influence it.

5. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

This study assessed the economic feasibility and sustainability of a biochar production system using residual biomass from Borgo di Perolla through a cost-benefit analysis across multiple scenarios. The results indicate that project profitability is highly dependent on the integration of market mechanisms. Scenario 1, based solely on biochar and wood distillate sales, proved economically unviable. In contrast, Scenario 2, which incorporates voluntary carbon market credits, and Scenario 3, which includes ETS participation from the fifth year, demonstrated significant profitability, particularly under configurations with higher production capacity.

The analysis highlights that market-based instruments, such as voluntary carbon markets and the EU ETS, are essential enablers for making high-impact environmental technologies economically attractive. These mechanisms not only generate financial returns but also facilitate broader environmental benefits, including soil improvement, sustainable waste management, and carbon sequestration. Without such instruments, innovative low-impact solutions risk remaining marginal or inaccessible despite their systemic advantages.

According to the results of the cost-benefit analysis, biochar only becomes an economically viable tool through carbon credit markets. In this sense, market infrastructures such as the ETS are fundamental for the dissemination of circular models that generate positive environmental and economic effects. It should also be noted that these types of technologies are still in the early stages of diffusion, often in start-up or experimental contexts, where installation, management, and maintenance costs are still high.

The research therefore emphasizes that public policies and market mechanisms aimed at offsetting environmental externalities are not secondary tools, but enabling conditions for the implementation of high-impact solutions. Without such support infrastructure, technologies such as biochar risk remaining marginal despite their potential, resulting in the waste of a concrete opportunity to combine economic development and environmental protection.

Robustness analysis revealed that investment feasibility is sensitive to external factors, particularly fluctuations in ETS carbon credit prices and macroeconomic and geopolitical conditions, which introduces inherent risk. This underscores the need for ongoing monitoring of market dynamics.

Future research should aim to quantify social and environmental benefits through multicriteria analyses and explore operational improvements. Policy support remains crucial: economic incentives, tax relief, and formal recognition of biochar as a certified removal technology under the ETS are key to promoting adoption. Equally important is the engagement of local stakeholders, including farmers and public authorities, to facilitate and ensure long-term sustainability.

Overall, this study demonstrates that integrating biochar production with carbon market mechanisms can create a viable pathway for economically and environmentally sustainable land management, representing a model for circular and resilient agricultural systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G.; methodology, G.G and A.P..; software, G.G.; validation, G.G. and A.P.; formal analysis, G.G.; investigation, G.G.; data curation, G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.; writing—review and editing, G.G. and A.P..; visualization, G.G.; supervision, A.P.; project administration, G.G.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Sustenia and its technical and scientific partners, as well as the owners of Borgo Perolla for providing the initial data, constructive feedback, and technical assistance throughout this research. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBA |

Cost-benefit analysis |

| NPV |

Net present value |

| IRR |

Internal rate of return |

| BEP |

Breakeven point |

| s1-3 |

Scenario 1 with three equipments |

| s1-5 |

Scenario 1 with five equipments |

| s2-3 |

Scenario 2 with three equipments |

| s2-5 |

Scenario 2 with five equipments |

| s3-3 |

Scenario 3 with three equipments |

| s3-5 |

Scenario 3 with five equipments |

| s4-3 |

Scenario 4 with three equipments |

| ETS |

Emission Trading System |

| BCR |

Biochar carbon removal |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

To strengthen the robustness of Scenario 3, an additional evaluation was conducted using the minimum and maximum EU ETS carbon credit prices recorded over the 2021–2025 period. These analyses complement the previous evaluations based on the average ETS price and the estimated voluntary market carbon credit price for biochar.

The minimum and maximum prices were calculated using daily estimates reported by Mazzarano et al. (2024) [

7] for 2021–2025, resulting in a minimum price of €33/t and a maximum of €98/t.

For scenario s3-3, assuming the minimum ETS price, the project proves entirely economically unviable. The analysis indicates absolute infeasibility at all considered discount rates. All NPV are negative, and the internal rate of return IRR is 0%, indicating that the initial investment cannot be recovered. Consequently, the break-even point is never reached for any discount rate.

Conversely, scenario s3-5 remains positive even under the minimum ETS price. The project is economically viable for discount rates of 3%, 6%, and 10%, with NPVs significantly positive, particularly €178,277.06 at i = 3%. The only exception is the 14% discount rate, chosen to test project feasibility limits. The IRR is 11%, exceeding all discount rates except i = 14%. The break-even point occurs in year 11 for i = 3%, year 13 for i = 6%, and year 18 for i = 10%. While the break-even is not achieved for i = 14%, the IRR suggests that payback could be attained in subsequent years if the project duration were extended.

These results highlight that, under EU ETS participation, prioritizing biochar production using five machines (s3-5) is essential to ensure recovery of the initial investment.

Table A1 reports the NPVs for each discount rate under the minimum ETS price of €33/t.

Table A1.

NPV for s3-3 and s3-5 with minimum ETS price.

Table A1.

NPV for s3-3 and s3-5 with minimum ETS price.

| i/Scenario |

s 3 - 3 |

s 3 - 5 |

| 3% |

-48,671.99 € |

178,277.06 € |

| 6% |

-79,165.48 € |

86,979.89 € |

| 10% |

-104,708.42 € |

10,000.81 € |

| 14% |

-121,025.11 € |

-39,610.67 € |

Using the maximum ETS price of €98/t, the project is economically sustainable under both production configurations. For scenario s3-3, NPVs are positive for discount rates of 3%, 6%, and 10%, with the highest NPV of €191,302.55 at i = 3%. The IRR is 13%, suggesting investment recovery is possible even at i = 14% if the project duration is extended. Break-even occurs in year 10 for i = 3%, year 11 for i = 6%, and year 15 for i = 10%.

Scenario s3-5 exhibits even more favorable outcomes under the maximum price. NPVs are positive for all discount rates, with the highest at €578,234.62 for i = 3%. The IRR of 25% greatly exceeds all chosen discount rates. The break-even point is reached in year 6 for i = 3%, year 7 for i = 6% and i = 10%, and year 8 for i = 14%.

Table A2 summarizes the NPVs under the maximum ETS price.

Table A2.

NPV for s3-3 and s3-5 with maximum ETS price.

Table A2.

NPV for s3-3 and s3-5 with maximum ETS price.

| i/Scenario |

s 3 - 3 |

s 3 - 5 |

| 3% |

191,302.55 € |

578,234.62 € |

| 6% |

104,632.10 € |

393,309.19 € |

| 10% |

31,822.96 € |

237,553.13 € |

| 14% |

-14,859.96 € |

137,331.25 € |

Notes

| 1 |

BCR: Biochar Carbon Removal is a negative emissions technology that converts biomass into biochar and it is one of the most scalable and technically advance solution that implement Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR). BCR can be tracked, certified and accounted for utilising certification systems that are based on evidence and product measurement [ 18]. Biochar has since become an important technology for providing credits within the voluntary carbon market, a market that allows companies and individuals to voluntarily offset their carbon footprint [ 19]. |

| 2 |

CAGR: Annual growth rate |

References

- Lehmann Johannes, Joseph Stephen, Biochar for environmental management: science and technology, 2009, Earthscan.

- COM/2020/98 final.

- Lehmann, J. A handful of carbon. Nature 2007, 447(7141), 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaashikaa, P. R.; Kumar, P. S.; Varjani, S.; Saravanan, A. A critical review on the biochar production techniques, characterization, stability and applications for circular bioeconomy. Biotechnology Reports 2020, 28, e00570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Shams; Mehejabin, Fatema; Chowdhury, Ashfaque; Almomani, Fares; Khan, Nadeem; Badruddin, Irfan; Kamangar, Sarfaraz. Biochar produced from waste-based feedstocks: Mechanisms, affecting factors, economy, utilization, challenges, and prospects. GCB Bioenergy 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaik, Hassan; Madihi, Salma; El Harfi, Meriem; Khiraoui, Abdelkarim; Aboulkas, Adil; El Harfi, Khalifa. Pyrolysis of macroalgal biomass: A comprehensive review on bio-oil, biochar, and biosyngas production. Sustainable Chemistry One World 2025, 5, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, Riti; Ahmad, Parvaiz; Rafatullah, Mohd. Insights into Biochar Applications: A Sustainable Strategy toward Carbon Neutrality and Circular Economy. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, Aashish. Biochar for Soil Health and Climate Change Mitigation: A Sustainable Approach. Ecofeminism and Climate Change 2024, 5(1), 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, Johannes & Gaunt, John & Rondon, Marco. (2006). Bio-char Sequestration in Terrestrial Ecosystems – A Review. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change. 11. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Cowie, Annette; Van Zwieten, L.; Bolan, Nanthi; Budai, Alice; Buss, Wolfram; Cayuela, Maria Luz; Graber, Ellen; Ippolito, Jim; Kuzyakov, Yakov; Luo, Yu; Ok, Yong Sik; Palansooriya, Kumuduni Niroshika; Shepherd, Jessica; Stephens, Scott; Weng, Han; Lehmann, Johannes. How biochar works, and when it doesn't: A review of mechanisms controlling soil and plant responses to biochar. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, Mofatteh. Biochar for a sustainable future: Environmentally friendly production and diverse applications. Results in Engineering 2024, 23, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campion, Luca; Bekchanova, Madina; Malina, Robert; Kuppens, Tom. The costs and benefits of biochar production and use: A systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 408, 137138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapero, J.R.; Alcazar-Ruiz, A.; Dorado, F.; Sanchez-Silva, L. Biochar price forecasting: A novel methodology for enhancing market stability and economic viability. Journal of Environmental Management 2025, 377, 124681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Robert; Anderson, Nathaniel; Daugaard, Daren; Naughton, Helen. Financial viability of biofuel and biochar production from forest biomass in the face of market price volatility and uncertainty. Applied Energy 2018, 230, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhamdi, Ridha. Evaluating the Evolution and Impact of Wood Vinegar Research: A Bibliometric Study. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2023, 175, 106190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supercritical, Biochar offtakes in 2025, 2024.

- Introduzione al biochar: nuovi scenari alla luce del contrasto del cambiamento climatico. Alessandro Pozzi, Ichar, Workshop: Impiego del biochar in Viticultura. Risultati del progetto PRIN-PNRR BIO-C-VITE, 2024.

- Chiaramonti, D.; Lehmann, J.; Berruti, F.; et al. Biochar is a long-lived form of carbon removal, making evidence-based CDR projects possible. Biochar 2024, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senadheera, Withana; You; Tsang, C.W.; Hwang, Sik Ok. Sustainable biochar: Market development and commercialization to achieve ESG goals. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2025, 217, 115744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clean Air Force and Concito, The Balancing Act: Risks and Benefits of Integrating Permanent Carbon Removals into the EU ETS, 2024.

- ICAP. (2022). Emissions Trading Worldwide: Status Report 2022. Berlin: International Carbon Action Partnership.

- BloombergNEF (BNEF). Available online: https://about.bnef.com/insights/commodities/europes-new-emissions-trading-system-expected-to-have-worlds-highest-carbon-price-in-2030-at-e149-bloombergnef-forecast-reveals/#:~:text=BloombergNEF's%20(BNEF's)%20EU%20ETS%20II,leading%20to%20significant%20emissions%20abatement.

- Mazzarano, M.; Borghesi, S. Searching for a Carbon Laffer Curve: Estimates from the European Union Emissions Trading System. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Shams; Mehejabin, Fatema; Chowdhury, Ashfaque; Almomani, Fares; Khan, Nadeem; Badruddin, Irfan; Kamangar, Sarfaraz. Biochar produced from waste-based feedstocks: Mechanisms, affecting factors, economy, utilization, challenges, and prospects. GCB Bioenergy 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antar, Mohammed; Lyu, Dongmei; Nazari, Mahtab; Shah, Ateeq; Zhou, Xiaomin; Smith, Donald L. Biomass for a sustainable bioeconomy: An overview of world biomass production and utilization. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 139, 110691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, Andrea; Pronti, Andrea; Mazzanti, Massimiliano; Pasti, Luisa. Exploitation of Waste Algal Biomass in Northern Italy: A Cost–Benefit Analysis. Pollutants 2024, 4, 393–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biochar Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report, 2025–2034, Polaris Market Research.

- Bolognesi, Silvia; Bernardi, Giorgia; Callegari, Arianna; Dondi, Daniele; Capodaglio, Andrea. Biochar production from sewage sludge and microalgae mixtures: properties, sustainability and possible role in circular economy. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cely Parra, Paola; Gascó, G.; Paz-Ferreiro, J.; Méndez, Ana. Agronomic properties of biochars from different manure wastes. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2014, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramonti, D.; Borghesi, S.; Pantaleo, M. A.; Pozzi, A.; Morese, M.; Bezzi, G.; Pieroni, S.; Casalino, P. Biochar e carbon farming: opportunità per il sequestro di carbonio e per lo sviluppo sostenibile delle aree rurali nell’Ue e nei Paesi terzi. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ensuring fair competition in CDR policy: Making the case for BCR integration in the EU ETS, 2025, Biochar Europe.

- European Biochar Market Report 2023 – 2024, 2024, European Biochar Industry.

- European Biochar Market Report 2024 – 2025, Biochar Europe.

- Global Biochar Market Report 2023, IBI, USBI.

- Gupta, S.; Kua, H. W. Carbonaceous micro-filler for cement: Effect of particle size and dosage of biochar on fresh and hardened properties of cement mortar. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 662, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider; Coulter; Cai; Hussain; Cheema; Wu; Zhang. An overview on biochar production, its implications, and mechanisms of biochar-induced amelioration of soil and plant characteristics. Pedosphere 2022, 32(Issue 1), 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Biochar Initiative, A Manual for Biochar Carbon Removal, A comparative guide for the certification of biochar production as a carbon sink. 2024.

- International Biochar Initiative, Global Biochar Market Report. 2023.

- Jeffery, Simon; Abalos, Diego; Prodana, Marija; Bastos, Ana; Van Groenigen, Jan Willem; Hungate, Bruce; Verheijen, Frank. Biochar boosts tropical but not temperate crop yields. Environmental Research Letters 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, Simon; Verheijen, Frank; Velde, Marijn; Bastos, Ana. A Quantitative Review of the Effects of Biochar Application to Soils on Crop Productivity Using Meta-Analysis. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment - AGR ECOSYST ENVIRON 2011, 144, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Cowie, Annette; Van Zwieten, L.; Bolan, Nanthi; Budai, Alice; Buss, Wolfram; Cayuela, Maria Luz; Graber, Ellen; Ippolito, Jim; Kuzyakov, Yakov; Luo, Yu; Ok, Yong Sik; Palansooriya, Kumuduni Niroshika; Shepherd, Jessica; Stephens, Scott; Weng, Han; Lehmann, Johannes. How biochar works, and when it doesn't: A review of mechanisms controlling soil and plant responses to biochar. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, Riti; Ahmad, Parvaiz; Rafatullah, Mohd. Insights into Biochar Applications: A Sustainable Strategy toward Carbon Neutrality and Circular Economy. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, Julian; Reike, Denise; Hekkert, M.P.. Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions. SSRN Electronic Journal 2017, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owsianiak, Mikołaj; Lindhjem, Henrik; Cornelissen, Gerard; Hale, Sarah; Sørmo, Erlend; Sparrevik, Magnus. Environmental and economic impacts of biochar production and agricultural use in six developing and middle-income countries. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 755, 142455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perman, R.; Ma, Y.; McGilvray, J.; Common, M. Natural resource and environmental economics, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education Limited, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Petelina, E.; Sanscartier, D.; MacWilliam, S.; Ridsdale, R. (2014). Environmental, social, and economic benefits of biochar application for land reclamation purposes [C]. [CrossRef]

- Pozzi Alessandro, Introduzione al biochar: nuovi scenari alla luce del contrasto del cambiamento climatico, Workshop: Impiego del biochar in Viticultura. Risultati del progetto PRIN-PNRR BIO-C-VITE, Associazione Italiana Biochar ICHAR, 2024.

- Pronti, A; Coccia, M. Multicriteria analysis of the sustainability performance between agroecological and conventional coffee farms in the East Region of Minas Gerais (Brazil). Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 2021, 36(3), 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronti, Andrea. Do agroecology practices help small coffee producers in income generation? A case study in minas gerais. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yaashikaa, P. R.; Kumar, P. S.; Varjani, S.; Saravanan, A. A critical review on the biochar production techniques, characterization, stability and applications for circular bioeconomy. Biotechnology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilberman, David; Laird, David; Rainey, Coleman; Song, Jie; Kahn, Gabriel. Biochar Supply-Chain and Challenges to Commercialization. GCB Bioenergy 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).