1. Introduction

Anderson–Fabry disease (FD) is an X-linked lysosomal storage disorder caused by pathogenic variants in the

GLA gene resulting in reduced or absent α-galactosidase A activity, and consequent progressive accumulation of globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) and its deacylated derivative globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3) in multiple cell types and tissues, also causing neurogenic inflammation and alterations of the peripheral nervous system in host defense and immunopathology [

1].

Clinically, the disorder manifests with neuropathic pain, angiokeratomas, hypohidrosis in early life, and evolves into renal failure, cardiomyopathy, cerebrovascular events and premature death—underscoring its systemic significance and the urgent need for enhanced mechanistic insights and improved therapeutic strategies [

2]. From a broader perspective, FD exemplifies how a monogenic lysosomal enzyme deficiency can trigger downstream metabolic, bioenergetic and immunoinflammatory cascades, thereby bridging classical lysosomal storage disease paradigms with those of metabolic-inflammatory disorders.

1.1. Molecular and metabolic basis

For many years the pathogenesis of FD was conceptualized principally as a substrate-storage disease: accumulation of Gb3 within lysosomes would lead to physical and functional disruption of cellular compartments, affecting organ function. However, this model appears incomplete: it fails to fully explain the phenotypic heterogeneity, organ-specific progression (e.g., why the heart or kidney is disproportionately affected in many cases), sex differences in expression, and the variable responsiveness to enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) [

3]. Accordingly, recent research has shifted towards mechanistic investigations into how lysosomal dysfunction initiates secondary disorders in metabolic and bioenergetic pathways.

Emerging studies reveal that Gb3/lyso-Gb3 accumulation impairs, autophagic flux and mitophagy, leading to persistence of dysfunctional mitochondria, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and bioenergetic failure [

1,

4]. For example, a study of mitochondrial microRNAs (“mitomiRs”) in FD patients demonstrated significant dysregulation of several miRs controlling mitochondrial homeostasis (respiratory chain, antioxidant capacity, apoptosis) [

5]. In addition, proteomic and animal-model work (e.g., a gla-/- zebrafish renal model) have shown downregulation of mitochondrial and lysosomal proteins and disturbances in glycolysis, galactose metabolism, mitochondrial morphology and antioxidant activity—implying that alterations can occur independently of overt Gb3 accumulation [

6]. These findings support a broader pathogenic network in which lysosomal substrate load triggers metabolic reprogramming, mitochondrial impairment, and ER stress/unfolded protein response, eventually contributing to cellular vulnerability beyond storage burden alone [

1,

4]. Indeed, defective fatty-acid oxidation has been documented in FD cells—with altered acylcarnitine profiles, decreased medium- and long-chain acylcarnitines, and accumulation of short-chain species—indicating that mitochondrial β-oxidation and lipid metabolism are compromised in FD [

1].

1.2. Inflammatory and immune mechanisms

In parallel to metabolic dysfunction, inflammation is increasingly recognised as a major driver of FD progression rather than simply a downstream consequence of cellular damage. In this context, accumulated glycosphingolipids (Gb3/lyso-Gb3) may act as danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), engaging pattern-recognition receptors such as TLR4 and activating NF-κB signalling, with subsequent induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, endothelial dysfunction and immune cell activation [

4,

7]. A large cohort study measuring inflammatory cytokines in FD found that many interleukins (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-17) and TNF-α were significantly elevated in FD patients compared to controls, and correlated with clinical severity scores (e.g., MSSI), cardiac and renal markers [

8]. Furthermore, some studies demonstrate that inflammatory activation may persist despite ERT, suggesting that immune and inflammatory networks might become self-sustaining (“metaflammation”) and partly decoupled from substrate load [

7,

9].

One of the current controversial issues is whether inflammation in FD should be viewed primarily as a direct consequence of glycosphingolipid accumulation (and thus reversible by substrate reduction) or whether it constitutes a secondary but independent pathological axis requiring targeted anti-inflammatory intervention. Some authors argue that once inflammatory and fibrotic processes have been triggered, they may progress irrespective of further substrate reduction, thus diminishing the efficacy of delayed therapy [

7,

10]. Moreover, complement activation (C3, C5a) has been documented in FD patients—with associations to genotype, presence of anti-drug antibodies, renal involvement and cardiovascular events—suggesting that humoral immune pathways contribute to organ damage beyond classical lysosomal overload [

9].

1.4. Diagnostic and therapeutic implications

On the diagnostic front, while lyso-Gb3 remains the most informative biochemical marker for diagnosis and monitoring (particularly in males), it does not fully normalise in many treated patients and only imperfectly reflects inflammatory or mitochondrial activation [

11,

12]. Recent work has evaluated panels of inflammatory and endothelial dysfunction markers (e.g., TNF-α, MCP-1, VEGF-A, GDF-15, MPO, ADAMTS-13) and found that they correlate with disease severity and may track response to therapy [

15]. Multi-omic approaches (transcriptomic/proteomic/mitomiR) are increasingly applied to identify novel biomarkers linked to mitochondrial, ER-stress and immune pathways [

5].

Therapeutically, the expanding view of FD as a confluence of lysosomal, metabolic and immune derangements has promoted interest in combination-based and pathway-targeted strategies. Approved treatments such as ERT (agalsidase alfa, agalsidase beta, pegunigalsidase alfa) and oral pharmacologic chaperones (migalastat) remain foundational [

12]. However, their limitations—especially when initiated late—are becoming more widely recognized. As such, future directions include substrate reduction therapy (SRT), gene and mRNA therapy, vesicle-packaged enzyme delivery, mitochondrial protective agents, anti-inflammatory and complement-modulating therapies, and metabolic modulators targeting fatty-acid oxidation or mitophagy [

12]. Some authors propose that early identification of mitochondrial/inflammatory signatures may allow stratification of patients for adjunctive therapies beyond enzyme correction [

10].

1.5. Aim of the review

Given this evolving mechanistic landscape, the aim of this review is to synthesise and critically evaluate the molecular, metabolic and inflammatory patterns implicated in FD pathogenesis; to examine how these axes intertwine; to review the controversies and diverging hypotheses (including inflammatory independence vs substrate-dependency, timing of fibrosis); and to discuss how these mechanistic insights translate into emerging biomarkers and therapeutic strategies. By offering this translationally-oriented framework, we intend to support precision-medicine strategies in FD—moving beyond enzyme correction to address the full complexity of disease biology and improve long-term outcomes.

2. Molecular basis of Fabry disease

The enzymatic defect of alfa galactosidase A prevents the degradation of neutral glycosphingolipids, primarily globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) and its derivative globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3), resulting in their progressive intracellular accumulation across multiple cell types, including endothelial cells, cardiomyocytes, podocytes, neurons, fibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells [

13]. The progressive storage of Gb3 within lysosomes disrupts their function by altering luminal pH, impairing the activity of hydrolytic enzymes, and interfering with vesicular trafficking and membrane recycling.[

14] Lyso-Gb3, although present at lower concentrations than Gb3, has been shown to exert potent biological effects, including stimulation of smooth muscle cell proliferation, podocyte injury, and activation of pro-hypertrophic signaling pathways in cardiomyocytes [

15]. Studies have demonstrated that lyso-Gb3 also acts as a pro-inflammatory mediator, inducing secretion of cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1, which contribute to early renal and vascular injury[

16]. More than 900 pathogenic variants in the GLA gene have been identified, producing varying levels of residual enzyme activity and resulting in a wide spectrum of clinical phenotypes, from classic early-onset forms to later-onset, organ-selective variants [

17].

The accumulation of Gb3 and lyso-Gb3 triggers profound alterations in several interconnected cellular pathways. A central element of these disturbances is the impairment of autophagy, which results from defective lysosomal clearance and leads to accumulation of autophagosomes and dysfunctional mitochondria. This disruption is particularly evident in cardiomyocytes and podocytes, where impaired autophagy contributes to hypertrophy, proteinuria, and organ-specific damage. Another important aspect of the molecular basis of Fabry disease is the induction of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress caused by misfolded α-galactosidase A proteins retained within the ER. These misfolded proteins activate the unfolded protein response (UPR), which aims to restore protein homeostasis but can lead to apoptosis and inflammation when chronically activated

([

18]. Additionally, Gb3 accumulation alters membrane architecture and facilitates the formation of lipid microdomains that interfere with signaling pathways involving growth factors, ion channels, and mechanosensitive receptors. This contributes to vascular dysfunction and hypertrophy, two major hallmarks of the disease [

19] The progressive intracellular accumulation of Gb3 also interferes with mitochondrial function, reducing ATP production, impairing oxidative phosphorylation, and enhancing the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These mitochondrial changes contribute to energetic failure, cellular dysfunction, and apoptotic signaling, particularly in high-energy tissues such as myocardium, kidney, and the peripheral nervous syste[

20].

ROS overproduction further amplifies the cellular stress response by activating redox-sensitive transcription factors including NF-κB and AP-1, promoting pro-inflammatory cytokine release and linking oxidative stress to chronic inflammation in Fabry disease [

21]. Additionally, alterations in mitochondrial dynamics, including impaired fusion, excessive fission, and reduced mitophagy, have been observed in experimental models of Fabry disease. These abnormalities exacerbate mitochondrial fragmentation, bioenergetic insufficiency, and susceptibility to stress-induced cell deat. In addition to impaired autophagy and mitochondrial dysfunction, Gb3 and lyso-Gb3 accumulation also affects lysosomal–endosomal trafficking, altering the internalization, recycling, and degradation of membrane receptors and transporters. This contributes to abnormal cell signaling, dysregulated ion homeostasis, and endothelial dysfunction, all of which are key hallmarks of Fabry disease pathophysiology

([

22]

). Moreover, the glycosphingolipid accumulation modifies the lipid composition of the plasma membrane, promoting the formation of altered lipid rafts that interfere with receptor clustering, mechanotransduction, and growth factor signaling. These changes have been associated with vascular instability, increased sensitivity to shear stress, and progressive cardiomyopathic remodeling [

23]. Finally, alterations in intracellular trafficking pathways influence the turnover and localization of key proteins involved in calcium handling, redox balance, and stress signaling. This further disrupts cellular homeostasis and contributes to the progressive dysfunction of organs primarily affected by the disease, such as the heart, kidneys, and nervous system

). Another fundamental molecular component of Fabry disease is the persistent accumulation of lyso-Gb3, which exerts biological effects beyond simple substrate storage. Lyso-Gb3 has been shown to act as a potent signaling lipid, capable of inducing proliferation in vascular smooth muscle cells, altering podocyte architecture, and promoting pro-fibrotic transcriptional programs that contribute to progressive organ damage. In addition to its proliferative effects, lyso-Gb3 stimulates the expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, linking substrate accumulation to early immune activation and creating a pro-inflammatory microenvironment in affected tissues such as the kidney and myocardium [

24]. Furthermore, lyso-Gb3 contributes to extracellular matrix remodeling by activating fibroblasts and promoting the deposition of collagen and other matrix proteins, accelerating fibrotic processes. This mechanism plays a central role in the development of cardiac and renal fibrosis in Fabry patients, even in the presence of enzyme replacement therapy [

25].

3. Metabolic alterations and organelle dysfunction

Fabry disease induces profound alterations in cellular bioenergetics, largely due to the accumulation of Gb3 and lyso-Gb3, which impair mitochondrial function. Experimental studies have demonstrated that mitochondrial respiration becomes progressively compromised, with defects in oxidative phosphorylation, reduced ATP production, and increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

20]. These metabolic impairments are particularly pronounced in tissues with high energetic demands, such as cardiomyocytes, podocytes, and neurons, where mitochondrial abnormalities contribute to organ-specific functional decline. The accumulation of damaged and dysfunctional mitochondria further exacerbates metabolic stress and promotes apoptotic signaling [

26]

Disruption of autophagy is another key feature of the metabolic remodeling seen in Fabry disease. Gb3 interferes with the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes, leading to impaired autophagic flux and accumulation of undegraded substrates. This results in a buildup of dysfunctional mitochondria and altered intracellular homeostasis [

27] Impaired autophagy also affects lipid turnover, contributing to abnormal lipid storage and exacerbating energy dysregulation. Persistent defects in autophagosome clearance create a vicious cycle that reinforces mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS accumulation [

28]

Gb3 and lyso-Gb3 also induce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, which occurs when misfolded or undegraded proteins accumulate within the ER lumen. This activates the unfolded protein response (UPR), a compensatory mechanism that becomes maladaptive when chronically stimulated. Sustained UPR activation contributes to reduced protein synthesis, alterations in calcium signaling, and initiation of apoptotic pathways [

29]ER stress additionally interferes with mitochondrial function by disrupting mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs), which play a crucial role in lipid exchange, calcium transfer, and mitochondrial dynamics. Alterations in these sites of inter-organelle communication contribute to metabolic instability and enhanced susceptibility to cellular stress [

30]

Another layer of metabolic dysregulation in Fabry disease involves abnormalities in mTOR signaling, a central regulator of nutrient sensing and cellular growth. Gb3-induced lysosomal dysfunction can alter mTORC1 activity, impairing the ability of cells to respond appropriately to nutrient availability and energy demand. This contributes to a shift toward glycolysis, loss of metabolic flexibility, and altered cell growth. These interconnected disruptions in lysosomal, ER, and mitochondrial function culminate in broad metabolic remodeling that precedes overt organ damage, highlighting the central role of bioenergetic failure in Fabry disease pathophysiology. Alterations in inter-organelle communication represent another critical aspect of metabolic remodeling in Fabry disease [

31]. Disrupted ER–mitochondria crosstalk interferes with calcium handling, lipid transfer, and stress signaling pathways, leading to impaired mitochondrial respiration and increased susceptibility to oxidative damage [

32]. Moreover, dysfunctional lysosomes fail to degrade damaged mitochondria through mitophagy, causing the persistent accumulation of fragmented and ROS-generating organelles. This accumulation amplifies redox imbalance and contributes to chronic metabolic stress in cardiomyocytes and renal cells [

33]

). Interference with lipid metabolism is another hallmark of Fabry disease, as Gb3 disrupts the synthesis and distribution of membrane lipids, altering the structure of lipid rafts and modifying receptor localization and signaling efficiency. These changes influence growth factor signaling, mechanotransduction, and endothelial responses to hemodynamic stress [

34]. Together, these metabolic and structural changes highlight a multifaceted landscape of organelle dysfunction that reinforces disease progression long before irreversible fibrosis becomes evident.

4. Inflammatory mechanisms

Inflammation plays a central and early role in the progression of Fabry disease, emerging not simply as a secondary response to substrate accumulation but as a primary driver of tissue injury. Lyso-Gb3 acts as a potent pro-inflammatory lipid mediator, engaging Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and triggering downstream NF-κB activation, which promotes transcription of cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [

35]. This TLR4-mediated inflammatory signaling contributes to endothelial activation, increased vascular permeability, and early renal and cardiac involvement. Studies demonstrate that lyso-Gb3 exposure increases the expression of adhesion molecules (VCAM-1, ICAM-1) on endothelial cells, facilitating leukocyte recruitment and chronic inflammatory infiltration [

10]Activation of the complement system represents another key contributor to inflammation in Fabry disease. Elevated plasma levels of complement fragments such as C3a and C5a have been observed in Fabry patients and correlate with endothelial dysfunction, microvascular injury, and progression of renal disease. C5a, in particular, acts as a potent anaphylatoxin that promotes chemotaxis, cytokine release, and oxidative burst in immune cells [

36]Complement deposition within renal tissue has been documented in Fabry nephropathy, where C5b-9 membrane attack complex contributes to podocyte injury and proteinuria, linking complement dysregulation to glomerular dysfunction [

37].

The adaptive immune system is also affected in Fabry disease. Patients exhibit alterations in T-cell activation, increased circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and enhanced B-cell responses. Immune dysregulation has been reported even in patients receiving enzyme replacement therapy, indicating persistent immunological activation despite partial metabolic correction [

38] Additionally, misfolded α-galactosidase A variants retained in the ER can serve as neo-antigens, promoting the development of neutralizing antibodies in some patients after enzyme replacement therapy, further amplifying inflammation and contributing to variable treatment response [

39].

Inflammation and oxidative stress form a mutually reinforcing cycle in Fabry disease. Mitochondrial-derived ROS amplify inflammatory signaling, while cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 impair mitochondrial respiration and promote ROS generation. This bidirectional relationship perpetuates tissue damage and accelerates progression toward fibrosis [

40]. This chronic inflammatory state contributes to fibrosis in multiple organs, including heart, kidney, and vascular tissues. Fibrotic remodeling persists even in patients with improved biochemical markers following enzyme replacement therapy, suggesting that inflammation represents a therapeutic target independent of substrate reduction [

41].

5. Interconnection Between Molecular, Metabolic, and Inflammatory Patterns

5.1. Lysosomal Dysfunction and Metabolic Reprogramming

Anderson–Fabry disease (FD) is no longer viewed as a purely lysosomal storage disorder but as a multisystemic metabolic disease characterized by profound molecular and bioenergetic perturbations. The deficiency of α-galactosidase A leads to the accumulation of globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) and its deacylated derivative lyso-Gb3, which act not only as inert storage compounds but also as bioactive lipids interfering with lysosomal–mitochondrial communication, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) integrity, and autophagic flux [

25].

Recent studies demonstrate that substrate overload impairs lysosomal acidification, disturbs autophagosome–lysosome fusion, and causes secondary accumulation of autophagic vacuoles and dysfunctional mitochondria [

1]. These defects generate a chronic state of bioenergetic failure, marked by decreased ATP synthesis, altered NAD+/NADH ratios, and increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Mitochondrial dysfunction is accompanied by downregulation of oxidative phosphorylation complexes, especially complexes I and IV, and suppression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α), a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis [

3].

This metabolic stress activates the mTOR/AMPK signaling axis, which senses nutrient and energy status. Excess Gb3 inhibits AMPK phosphorylation and constitutively activates mTORC1, resulting in defective autophagy, increased protein synthesis, and accumulation of damaged organelles [

41,

42]. Moreover, ER stress and the unfolded-protein response (UPR) contribute to the release of inflammatory mediators and apoptotic factors. Misfolded glycoproteins within the ER activate PERK, ATF6, and IRE1α, inducing CHOP-mediated apoptosis and the production of IL-6 and CCL2 [

3,

10,

43]

Biddeci et al. and Feriozzi et al. have emphasized that these metabolic perturbations are not merely intracellular phenomena but extend to systemic metabolic rewiring, including lipidome alterations, oxidative imbalance, and abnormal redox signaling [

3,

10]. In both plasma and tissue biopsies from FD patients, elevated advanced oxidation protein products (AOPP), decreased thiol groups, and reduced ferric-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) reflect an exhausted antioxidant system, as shown by Simoncini et al. Notably, oxidative stress is detectable even in treatment-naïve patients with normal lyso-Gb3 levels, indicating that redox imbalance may precede overt substrate accumulation [

44]. These findings support the hypothesis that mitochondrial and ER stress act as early amplifiers of the metabolic defect, bridging the gap between molecular dysfunction and inflammation.

In summary, lysosomal dysfunction in FD triggers a cascade of metabolic reprogramming involving autophagy impairment, mitochondrial injury, oxidative stress, and UPR activation. These processes not only contribute to tissue damage but also serve as molecular signals that recruit the innate immune system, setting the stage for a self-perpetuating inflammatory response.

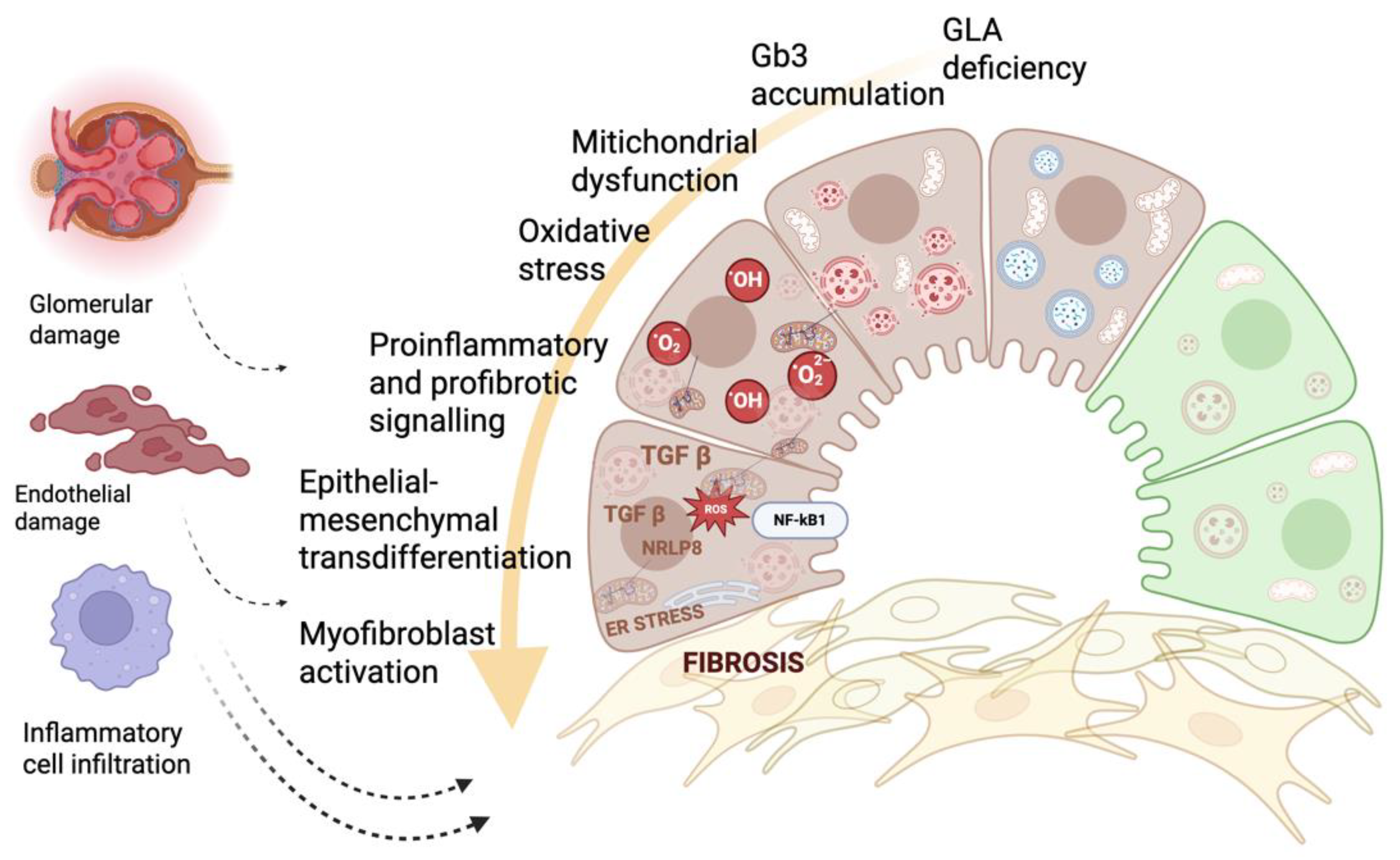

Figure 1.

5.2. Metabolic–Inflammatory Crosstalk and Immune Activation

The transition from isolated metabolic stress to chronic inflammation represents a defining step in FD pathogenesis. Lyso-Gb3 and related glycosphingolipids function as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) capable of engaging pattern-recognition receptors, notably the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), leading to downstream activation of NF-κB and the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [

45]. Kurdi et al. and Tuttolomondo et al. demonstrated that this axis underpins a state of chronic

metaflammation, in which metabolic and inflammatory cues sustain each other through reciprocal activation loops [

3,

45].

The accumulation of Gb3 within endothelial and smooth-muscle cells enhances NADPH-oxidase activity, resulting in elevated ROS production and oxidative damage. ROS, in turn, potentiate NF-κB signaling and promote the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, a cytosolic complex responsible for caspase-1–mediated maturation of IL-1β and IL-18. Activation of NLRP3 has been detected in monocytes from FD patients and correlates with plasma IL-1β levels, supporting its pathogenic role in vascular inflammation and fibrosis [

3,

46].

Inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 not only perpetuate immune activation but also directly impair mitochondrial respiration, reduce ATP generation, and exacerbate oxidative stress. These cytokine-induced metabolic changes resemble mechanisms observed in chronic inflammatory conditions and drive further mitochondrial dysfunction in Fabry disease [

47]. Lyso-Gb3 represents a key molecular link between substrate accumulation, inflammation, and fibrosis. By engaging TLR4 and other innate immune receptors, lyso-Gb3 promotes cytokine release, fibroblast activation, and extracellular matrix deposition, contributing to progressive organ remodeling [

19]

Organelle stress also contributes to immune activation. ER stress triggered by misfolded α-galactosidase A variants activates the unfolded protein response (UPR), which enhances cytokine production and interferes with mitochondrial function, creating a direct link between protein misfolding and inflammation. These processes contribute to multi-organ pathology even in patients with late-onset mutations [

48]

). Together, these interconnected pathways illustrate that Fabry disease is not simply the consequence of lysosomal substrate accumulation but a complex network of metabolic, molecular, and inflammatory disturbances that interact synergistically to drive disease progression long before irreversible organ damage becomes clinically evident.

The inflammatory network extends beyond innate immunity. Complement activation, particularly through the alternative and lectin pathways, contributes to endothelial injury and microvascular remodeling. Marín-Gómez et al. (2025) performed a longitudinal immuno-genetic analysis revealing persistent complement activation and elevated cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-10) even in patients under long-term enzyme replacement therapy. Moreover, single-nucleotide polymorphisms in TLR4, IL6, and TNFA were associated with differential cytokine profiles and organ involvement, suggesting a genetic modulation of inflammatory response in FD [

49]. Activation of C5a and formation of the membrane attack complex (C5b-9) enhance cytokine release, induce oxidative burst, and promote endothelial injury. These mechanisms contribute to renal and vascular pathology and reinforce the connection between immune dysregulation and metabolic stress

([

36]

).Persistent complement activation has been observed in renal biopsies of Fabry patients, where it contributes to podocyte injury and promotes progression toward proteinuria and fibrosis. This demonstrates that complement is not merely a downstream effect of storage but an active driver of disease progression [

50].

Another level of crosstalk involves the endothelial glycocalyx and vascular oxidative stress. Endothelial cells exposed to lyso-Gb3 exhibit upregulation of adhesion molecules (VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-selectin), promoting leukocyte recruitment and microvascular inflammation [

3]. The pro-oxidant milieu, sustained by mitochondrial dysfunction, compromises nitric-oxide bioavailability and vascular reactivity, leading to microangiopathy and perfusion defects typical of FD.

Importantly, mitochondrial dysfunction itself acts as a pro-inflammatory signal. Damaged mitochondria release mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and cardiolipin fragments into the cytosol, which act as ligands for TLR9 and NLRP3, further fueling inflammation [

42,

46]. This creates a vicious cycle: lysosomal storage impairs mitochondrial clearance, leading to oxidative stress and mtDNA release, which in turn activates innate immune pathways that perpetuate inflammation and fibrosis.

Recent evidence from Feriozzi et al. indicates that this metabolic–immune axis also influences adaptive immunity. Increased circulating CD8+ T cells expressing activation markers (CD38, HLA-DR) and decreased regulatory T cells (Tregs) have been documented, suggesting that chronic metabolic stress drives systemic immune activation [

51]. Collectively, these findings highlight FD as a prototypical disease of metabolic inflammation, in which mitochondrial, lysosomal, and immune dysfunction are inseparably intertwined.

6. Biomarkers of Pathogenesis and Disease Progression

The identification of reliable biomarkers in Anderson–Fabry disease (FD) remains a central challenge. Due to the disease’s long asymptomatic latency, clinical heterogeneity, and variable therapeutic responsiveness, early and accurate detection of biochemical, metabolic, or inflammatory alterations is pivotal for improving patient stratification, therapeutic timing, and outcome prediction [

9,

52]. Over the past decade, biomarker research in FD has shifted from single-analyte approaches toward multiparametric,

omics-driven signatures that reflect the complex interplay between lysosomal dysfunction, metabolic stress, and chronic inflammation [

3,

4].

Table 1.

6.1. Classical biochemical markers: Gb3 and lyso-Gb3

Traditionally, plasma or urinary globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) quantification served as a biochemical hallmark of FD. However, its diagnostic sensitivity is limited—particularly in late-onset forms and heterozygous females—due to overlapping values with healthy individuals and poor correlation with clinical severity [

9,

11]. The subsequent discovery of the deacylated derivative globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3) represented a major advance. Lyso-Gb3 is more soluble and diffusible than Gb3 and accumulates systemically in plasma, urine, and tissues. It is now considered the reference biochemical biomarker for diagnosis, screening, and therapeutic monitoring [

9,

52].

Elevated plasma lyso-Gb3 concentrations correlate with

GLA genotype, disease phenotype, and sex. Classic hemizygous males typically exhibit markedly increased values (>100 ng/mL), late-onset variants show moderate elevations, and heterozygous females present variable levels depending on X-chromosome inactivation [

52,

53]. The ratio of α-galactosidase A activity to lyso-Gb3 concentration in dried-blood spots improves diagnostic accuracy, particularly in females [

67]. Moreover, cumulative exposure to lyso-Gb3 (product of concentration × age) appears to better reflect total metabolic burden and may serve as a composite indicator of long-term risk[

9].

Beyond its diagnostic role, lyso-Gb3 is mechanistically relevant. In vitro, it induces endothelial activation, smooth-muscle proliferation, oxidative stress, and TLR4/NF-κB-mediated cytokine release, thereby bridging lysosomal dysfunction and inflammatory signaling [

10,

52]. Clinically, lyso-Gb3 correlates with left-ventricular mass index (LVMI), Mainz Severity Score Index (MSSI), and the extent of white-matter lesions in MRI studies, although variability across cohorts limits its prognostic precision. Its decline during enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) is rapid in classic males but often incomplete in females or advanced disease, indicating residual cellular storage or ongoing inflammation [

54].

6.2. Lyso-Gb3 analogues and glycosphingolipid isoforms

Recent advances in high-resolution mass spectrometry have revealed multiple lyso-Gb3 analogues differing in sphingoid-base length and saturation (e.g., −28 Da, −12 Da, +14 Da, +16 Da, +34 Da, +50 Da). These analogues display tissue- and phenotype-specific patterns: for instance, analog +50 correlates with cardiac-variant disease, while analogues +16 and +34 associate with renal or neurologic involvement [

56]. Quantification of the sum of urinary lyso-Gb3 + analogues has shown near-100 % sensitivity and specificity for FD diagnosis, outperforming isolated lyso-Gb3 in detecting late-onset and female cases [

57]. Additionally, the relative abundance of Gb2 and methylated Gb3 isoforms in urine may discriminate pathogenic variants from benign polymorphisms, suggesting their utility in newborn screening or genotype reclassification [

58].

6.3. Accumulation vs. response biomarkers

Carnicer-Cáceres et al. introduced a distinction between accumulation biomarkers—directly reflecting glycosphingolipid storage (e.g., Gb3, lyso-Gb3, analogues, Gb2, CD77 expression)—and response biomarkers, which mirror the cellular and inflammatory reactions to substrate overload. The latter group captures secondary injury pathways (oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis, apoptosis) and may offer earlier detection of organ damage before irreversible structural alterations occur [

54].

Among response biomarkers, plasma nitrotyrosine (3-NT), malondialdehyde (MDA), myeloperoxidase (MPO), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) have been linked to oxidative stress and vascular injury. Increased sICAM-1, sVCAM-1, IL-6, TNF-α, and P-selectin levels confirm endothelial activation and metaflammation [

59,

60]. Importantly, these markers remain elevated even in ERT-treated patients, suggesting partial therapeutic uncoupling between enzyme correction and inflammatory tone.

6.4. Organ-specific biomarkers

FD’s multisystemic nature necessitates organ-focused biomarker panels:

Renal involvement: Beyond albuminuria and estimated glomerular-filtration rate, podocyturia, urinary CD80, and urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) have emerged as sensitive indicators of early podocyte injury [

61]. Lyso-Gb3 exposure in cultured podocytes upregulates TGF-β1, Notch-1, fibronectin, and collagen IV, mediators of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and fibrosis [

62]. Quantification of urinary podocin and podocalyxin by LC-MS/MS provides a reproducible, non-invasive readout of nephropathy onset [

63].

Cardiac involvement: High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) and NT-proBNP remain the most validated markers of myocardial stress and fibrosis. Their increase often precedes imaging evidence of late-gadolinium enhancement. Carnicer-Cáceres et al. also highlight TGF-β1, VEGF, VEGFR2, FGF-2, MMP-2, and thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) as potential cardiac remodeling mediators and surrogate biomarkers [

54,

64].

Vascular and systemic inflammation: Alonso-Núñez et al. identified a circulating inflammatory–cardiovascular biomarker panel comprising TNF-α, MCP-1, MIP-1β, VEGF-A, ADAMTS-13, GDF-15, MPO, and MIC-1. Elevated levels correlated with disease severity, cardiac hypertrophy, and reduced renal function, suggesting prognostic and therapeutic-monitoring value. Notably, ADAMTS-13 deficiency—previously associated with endothelial dysfunction—was linked to enhanced microvascular injury and inflammatory activation in FD [

8,

65].

6.5. Omic and molecular biomarkers

Advances in

omics have revealed multi-layered perturbations in FD. Proteomic analyses of plasma and urinary exosomes identify dysregulation of lysosomal proteins (cathepsins B/D), oxidative-stress enzymes (SOD2, peroxiredoxins), and mitochondrial metabolic regulators (ATP5A, cytochrome c oxidase subunits) [

57,

67]. Transcriptomic studies in peripheral blood mononuclear cells reveal activation of NF-κB, mTOR, autophagy, and ER-stress pathways, correlating with cardiac and renal involvement[

66,

67].

MicroRNAs (miRs) are gaining attention as non-invasive dynamic biomarkers. Dysregulation of miR-21, miR-29, miR-1307-5p, and miR-199a-5p has been associated with fibrosis, endothelial activation, and mitochondrial dysfunction in FD. These molecules could complement biochemical markers by providing real-time insights into disease activity and therapeutic response [

68,

69].

6.6. Imaging and composite biomarkers

Quantitative cardiac MRI (native T1 mapping, extracellular-volume fraction, late-gadolinium enhancement) and renal MRI (diffusion and perfusion metrics) are increasingly integrated as imaging biomarkers complementing biochemical data [

53]]. Cerebral MRI parameters—white-matter hyperintensity volume, basilar-artery diameter—also provide quantifiable indices of neurologic involvement [

70]. Composite scoring systems such as the Fabry Stabilization Index (FASTEX) and Modified Mainz Severity Score Index (MSSI) combine biochemical, imaging, and clinical parameters to longitudinally assess disease control [

71].

7. Therapeutic Strategies and Novel Targets

The therapeutic management of Anderson–Fabry disease (FD) has evolved substantially over the past two decades, yet significant challenges persist in halting organ progression and reversing tissue remodeling. Traditional approaches have largely focused on replacing or stabilizing the deficient enzyme, while novel molecular targets are emerging from the expanding understanding of the disease’s inflammatory, metabolic, and mitochondrial underpinning [

72].

Table 2.

7.1. Specific disease-modifying therapies: enzymes, chaperones, and gene therapy

Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) remains the mainstay of treatment. Recombinant α-galactosidase A—either agalsidase alfa, agalsidase beta, or the newer PEGylated form pegunigalsidase alfa—can reduce plasma and tissue Gb3 and lyso-Gb3, alleviate neuropathic and cardiac symptoms, and stabilize renal function [

72]. Despite these benefits, ERT is limited by its short half-life, incomplete biodistribution to critical organs (particularly heart and brain), and the formation of neutralizing anti-drug antibodies.

Pharmacological chaperone therapy, using small molecules such as migalastat, selectively binds to specific amenable GLA variants, stabilizing misfolded α-galactosidase A and enhancing its trafficking to lysosomes [

73]. This oral option is effective in roughly 35–50 % of genotypes, mainly in late-onset variants.

Gene-therapy and mRNA-based strategies are now entering clinical stages. AAV-mediated liver-directed gene transfer and lipid-nanoparticle-encapsulated mRNA formulations have shown sustained enzymatic activity and Gb3 clearance in preclinical and early-phase trials. Nevertheless, uncertainty persists regarding long-term expression, vector immunogenicity, and potential immune activation[

74]. Thus, while these approaches correct the genetic defect, they do not directly address the secondary molecular cascades—inflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and fibrosis—that drive irreversible organ damage.

7.2. Pathway-Driven Therapeutics: Metabolic, Immune–Inflammatory, and Next-Generation Targets

Recent pathophysiological insights reveal that lysosomal substrate overload impairs autophagy and mitophagy, leading to the persistence of damaged mitochondria and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

75]. The resulting bioenergetic failure activates the AMPK–mTOR axis, disrupting cellular homeostasis. Pharmacologic activation of AMPK (e.g., by metformin, AICAR) and mTOR modulation have been proposed to restore autophagic flux and improve mitochondrial efficiency[

4]. Experimental data from fibroblasts and murine models indicate that mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin, everolimus) can normalize autophagy markers (LC3B-II, p62)thus assuming that this mechanism may reduce Gb3 accumulation without altering α-Gal A levels [

76,

77]

Moreover, mitochondria-targeted antioxidants—such as MitoQ, coenzyme Q10, and N-acetylcysteine—have demonstrated reductions in ROS production and improvement in endothelial function in preclinical FD models[

45]. Restoration of mitochondrial biogenesis through PGC-1α activation (using bezafibrate or resveratrol) may counteract metabolic inflexibility and oxidative stress. These strategies, while still investigational, aim to complement enzyme-based therapy by addressing the metabolic roots of cellular dysfunction [

78,

79]

Multiple studies, including those by Tuttolomondo et al. and Kurdi et al., emphasize that chronic inflammation is a central amplifier of tissue injury in FD. The TLR4/NF-κB pathway, activated by lyso-Gb3 and other glycosphingolipids, triggers transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and adhesion molecules (VCAM-1, ICAM-1) [

3,

45,

46]. Pharmacologic blockade of TLR4 using antagonists such as TAK-242 or eritoran, and downstream inhibition of NF-κB activation (via IKKβ inhibitors or curcumin analogues), has been shown in vitro to attenuate cytokine release and oxidative stress[

80].

Additionally, NLRP3 inflammasome activation has been identified as a mediator of lysosome-dependent inflammation. Gb3 accumulation causes lysosomal rupture, cathepsin-B release, and NLRP3 assembly, culminating in IL-1β and IL-18 secretion [

81,

10,

82].

The complement system is another actionable target: uncontrolled activation of C3 and C5 fragments promotes microvascular inflammation and fibrosis. Early-phase studies are exploring complement inhibitors (e.g., eculizumab, ravulizumab, C5aR1 antagonists) as adjunctive therapy, particularly in antibody-positive ERT recipients[

46,

83,

84].

Persistent inflammation and metabolic stress converge on fibrogenic pathways, mainly through TGF-β1, Notch-1, connective-tissue growth factor (CTGF), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2, MMP-9) [

55] These mediators drive extracellular-matrix deposition and organ stiffening, particularly in the heart and kidneys. In FD-derived fibroblasts, TGF-β1 blockade using monoclonal antibodies or receptor-kinase inhibitors (SB431542) attenuates collagen synthesis and reduces SMAD-2/3 phosphorylation [

85]. Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) and ACE inhibitors—beyond their hemodynamic effects—also inhibit TGF-β1 and NADPH oxidase activity, reducing fibrotic signaling. Emerging studies on MMP modulation suggest that balancing extracellular-matrix turnover may reverse early fibrotic remodeling. Agents such as doxycycline (a non-specific MMP inhibitor) or selective MMP-2/9 blockers are under evaluation for their potential to slow cardiac hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis in FD[

55,

85,

86]

MicroRNAs represent promising next-generation therapeutic targets. Dysregulated miR-21, miR-29, miR-1307-5p, and miR-199a-5p contribute to pro-fibrotic and inflammatory phenotypes by repressing PPAR-α, SIRT1, and mitochondrial genes [

46,

87] Experimental silencing of miR-21 (via antagomiRs) in cardiomyocytes reduces fibrosis and restores mitochondrial metabolism [

88,

89]. Furthermore, epigenetic modulators—such as histone-deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors—can enhance lysosomal biogenesis and autophagic efficiency, providing an indirect means of restoring cellular clearance.[

90]

8. Discussion

Fabry disease emerges as a complex multisystem disorder in which lysosomal dysfunction, metabolic remodeling, organelle stress, and chronic inflammation form an integrated pathogenic network. The initial defect in α-galactosidase A results in progressive accumulation of Gb3 and lyso-Gb3, leading to disrupted lysosomal clearance, autophagic impairment, and metabolic instability. These early molecular events propagate through interconnected pathways involving mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, ER stress, and inflammatory activation, which together contribute to progressive cardiac, renal, and neurological injury. The persistence of these mechanisms even after biochemical improvement highlights the complexity of Fabry disease beyond simple substrate accumulation.

Clinical variability among Fabry patients reflects differences in residual enzyme activity, substrate accumulation, inflammatory signatures, and organ-specific vulnerability. Genotype–phenotype studies have demonstrated that distinct GLA variants result in different disease trajectories, highlighting the need for personalized approaches to diagnosis and treatment. Despite advances in enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) and chaperone therapy, many patients continue to show progression of fibrosis, inflammation, and organ dysfunction. This underscores the need for therapies targeting multiple nodes of the pathogenic network, including inflammation, oxidative stress, complement activation, and metabolic reprogramming. Understanding the interconnection among molecular, metabolic, and inflammatory pathways in FD has also profound implications for both biomarker discovery and therapy.

A key insight from recent research into underlying biological processes is the bidirectional interplay between metabolic/mitochondrial dysfunction and immune/inflammatory activation in FD. Mitochondrial dysfunction, ROS generation and bioenergetic failure may prime endothelial cells and immune cells for activation, while chronic inflammation and cytokine release further impair mitochondrial biogenesis, reduce autophagic capacity and promote fibrotic remodelling. This vicious cycle may help explain differences in clinical progression despite similar substrate loads and highlight why early intervention is critical. It also underscores the importance of viewing FD not merely as enzyme deficiency but as a systemic disease of intertwined metabolic-inflammatory networks.

From a diagnostic standpoint, integrating biochemical (lyso-Gb3, AOPP), metabolic (acyl-carnitine profile, redox markers), and inflammatory (cytokines, complement, adhesion molecules) biomarkers offers a more holistic view of disease activity. The recognition that oxidative stress precedes substrate accumulation suggests that redox imbalance could serve as an early disease indicator, particularly in genotype-positive, phenotype-negative individuals.

Therapeutically, the elucidation of these networks supports a shift from enzyme-centric correction to pathway-targeted modulation. Anti-inflammatory approaches aimed at the TLR4/NF-κB and NLRP3 axes, antioxidants targeting mitochondrial ROS, and metabolic modulators of AMPK–mTOR signaling are emerging as rational adjuncts to enzyme therapy. Moreover, the involvement of profibrotic mediators such as TGF-β1, Notch-1, and MMP-2/9 underscores the importance of early intervention to prevent irreversible fibrosis. Given the interdependence of lysosomal, metabolic, and inflammatory pathways, combination strategies are increasingly advocated. Early intervention with ERT or chaperones may reduce substrate accumulation, while adjunctive anti-inflammatory or mitochondrial-protective therapies could prevent secondary injury. For example, combining ERT with AMPK activators or NF-κB inhibitors in preclinical models enhances autophagic recovery and attenuates cytokine up-regulation.

At the systems level, multi-omics integration and machine-learning approaches can delineate patient-specific molecular fingerprints to guide personalized treatment. The convergence of molecular biology, immunogenetics, and metabolomics thus holds promise for a future precision-medicine framework in FD, where disease monitoring and therapy are tailored to each patient’s mechanistic profile rather than to clinical stage alone.

Longitudinal and omics-guided approaches—integrating biochemical (lyso-Gb3, cytokines), imaging (T1 mapping, fibrosis index), and transcriptional (miRNA, mTOR, NF-κB) readouts—may enable real-time therapeutic adjustment. The concept of precision therapy in FD thus extends beyond enzyme correction to encompass modulation of the metabolic-inflammatory interface driving disease progression.

In conclusion, the interplay between molecular, metabolic, and inflammatory disturbances forms a unified pathogenic continuum in Fabry disease. Lysosomal storage triggers metabolic reprogramming, mitochondrial failure sustains oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation promotes irreversible fibrosis. This mechanistic synergy provides both a challenge and an opportunity: targeting the interconnections—rather than isolated pathways—may ultimately yield the most effective strategies for halting disease progression and improving patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, X.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, L.; Huo, M.; Li, Q. Fabry Disease: Mechanism and Therapeutics Strategies. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 1025740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieroni, M.; Moon, J.C.; Arbustini, E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Camporeale, A.; Vujkovac, A.C.; Elliott, P.M.; Hagege, A.; Kuusisto, J.; Linhart, A.; et al. Cardiac Involvement in Fabry Disease: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021, 77, 922–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, H.; Lavalle, L.; Moon, J.C.C.; Hughes, D. Inflammation in Fabry Disease: Stages, Molecular Pathways, and Therapeutic Implications. Front Cardiovasc Med 2024, 11, 1420067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, D.; Dudek, J.; Sequeira, V.; Maack, C. Fabry Disease: Cardiac Implications and Molecular Mechanisms. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2024, 21, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambardella, J.; Fiordelisi, A.; Sorriento, D.; Cerasuolo, F.; Buonaiuto, A.; Avvisato, R.; Pisani, A.; Varzideh, F.; Riccio, E.; Santulli, G.; et al. Mitochondrial MicroRNAs Are Dysregulated in Patients with Fabry Disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2023, 384, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaid, H.O.A.; Rivedal, M.; Skandalou, E.; Svarstad, E.; Tøndel, C.; Birkeland, E.; Eikrem, Ø.; Babickova, J.; Marti, H.-P.; Furriol, J. Proteomic Analysis Unveils Gb3-Independent Alterations and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in a Gla-/- Zebrafish Model of Fabry Disease. J Transl Med 2023, 21, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, F.; Ling, C.; Wu, Y.; Ma, W.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Hao, H.; Zhang, W. Inflammatory Cytokine Expression in Fabry Disease: Impact of Disease Phenotype and Alterations under Enzyme Replacement Therapy. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1367252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Núñez, A.; Pérez-Márquez, T.; Alves-Villar, M.; Fernández-Pereira, C.; Fernández-Martín, J.; Rivera-Gallego, A.; Melcón-Crespo, C.; San Millán-Tejado, B.; Ruz-Zafra, A.; Garofano-López, R.; et al. Inflammatory and Cardiovascular Biomarkers to Monitor Fabry Disease Progression. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 6024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, P. Biomarkers in Anderson-Fabry Disease: What Should We Use in the Clinical Practice? rdodj 2024, 3, N/A–N/A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddeci, G.; Spinelli, G.; Colomba, P.; Duro, G.; Giacalone, I.; Di Blasi, F. Fabry Disease Beyond Storage: The Role of Inflammation in Disease Progression. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 7054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaswami, U.; West, M.L.; Tylee, K.; Castillon, G.; Braun, A.; Ren, M.; Doobaree, I.U.; Howitt, H.; Nowak, A. The Use and Performance of Lyso-Gb3 for the Diagnosis and Monitoring of Fabry Disease: A Systematic Literature Review. Mol Genet Metab 2025, 145, 109110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, M.; Menke, E.R.; Brand, E. Progress and Challenges in the Treatment of Fabry Disease. BioDrugs 2025, 39, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, R.O.; Gal, A.E.; Bradley, R.M.; Martensson, E.; Warshaw, A.L.; Laster, L. Enzymatic Defect in Fabry’s Disease. Ceramidetrihexosidase Deficiency. N Engl J Med 1967, 276, 1163–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germain, D.P. Lysosomes and lysosomal storage diseases. J Soc Biol 2002, 196, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aerts, J.M.; Groener, J.E.; Kuiper, S.; Donker-Koopman, W.E.; Strijland, A.; Ottenhoff, R.; van Roomen, C.; Mirzaian, M.; Wijburg, F.A.; Linthorst, G.E.; et al. Elevated Globotriaosylsphingosine Is a Hallmark of Fabry Disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 2812–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Niño, M.D.; Sanz, A.B.; Carrasco, S.; Saleem, M.A.; Mathieson, P.W.; Valdivielso, J.M.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Egido, J.; Ortiz, A. Globotriaosylsphingosine Actions on Human Glomerular Podocytes: Implications for Fabry Nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011, 26, 1797–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germain, D.P. Fabry Disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2010, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnain, S.Z.; Lourie, R.; Das, I.; Chen, A.C.-H.; McGuckin, M.A. The Interplay between Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Inflammation. Immunol Cell Biol 2012, 90, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, F.M.; Boland, B.; van der Spoel, A.C. Lysosomal Storage Disorders: The Cellular Impact of Lysosomal Dysfunction. J Cell Biol 2012, 199, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Mata, M.; Cotán, D.; Villanueva-Paz, M.; de Lavera, I.; Álvarez-Córdoba, M.; Luzón-Hidalgo, R.; Suárez-Rivero, J.M.; Tiscornia, G.; Oropesa-Ávila, M. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Lysosomal Storage Disorders. Diseases 2016, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reactive Oxygen Species in Metabolic and Inflammatory Signaling | Circulation Research. Available online: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circresaha.117.311401 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Saftig, P.; Klumperman, J. Lysosome Biogenesis and Lysosomal Membrane Proteins: Trafficking Meets Function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009, 10, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillence, D.J. New Insights into Glycosphingolipid Functions--Storage, Lipid Rafts, and Translocators. Int Rev Cytol 2007, 262, 151–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, A.-R.; Park, S.; Woo, C.-H. Lyso-Globotriaosylsphingosine Induces Endothelial Dysfunction via Autophagy-Dependent Regulation of Necroptosis. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol 2023, 27, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidemann, F.; Sanchez-Niño, M.D.; Politei, J.; Oliveira, J.-P.; Wanner, C.; Warnock, D.G.; Ortiz, A. Fibrosis: A Key Feature of Fabry Disease with Potential Therapeutic Implications. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faro, D.C.; Di Pino, F.L.; Monte, I.P. Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Endothelial Dysfunction in the Pathogenesis of Vascular Damage: Unraveling Novel Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Fabry Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 8273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M.M.; Changsila, E.; Iaonou, C.; Goker-Alpan, O. Impaired Autophagic and Mitochondrial Functions Are Partially Restored by ERT in Gaucher and Fabry Diseases. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0210617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, M.J. Autophagy in Health and Disease. 2. Regulation of Lipid Metabolism and Storage by Autophagy: Pathophysiological Implications. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2010, 298, C973–C978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and the Inflammatory Basis of Metabolic Disease. Cell 2010, 140, 900–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C.; Felli, E.; Lange, N.F.; Berzigotti, A.; Gracia-Sancho, J.; Dufour, J.-F. Endoplasmic Reticulum and Mitochondria Contacts Correlate with the Presence and Severity of NASH in Humans. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 8348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genetic and Metabolic Molecular Research of Lysosomal Storage Disease 3.0 | IJMS. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Fan, Y.; Simmen, T. Mechanistic Connections between Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Redox Control and Mitochondrial Metabolism. Cells 2019, 8, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickles, S.; Vigié, P.; Youle, R.J. Mitophagy and Quality Control Mechanisms in Mitochondrial Maintenance. Curr Biol 2018, 28, R170–R185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGlynn, R.; Dobrenis, K.; Walkley, S.U. Differential Subcellular Localization of Cholesterol, Gangliosides, and Glycosaminoglycans in Murine Models of Mucopolysaccharide Storage Disorders. J Comp Neurol 2004, 480, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, G.I.; Langley, K.G.; Berglund, N.A.; Kammoun, H.L.; Reibe, S.; Estevez, E.; Weir, J.; Mellett, N.A.; Pernes, G.; Conway, J.R.W.; et al. Evidence That TLR4 Is Not a Receptor for Saturated Fatty Acids but Mediates Lipid-Induced Inflammation by Reprogramming Macrophage Metabolism. Cell Metabolism 2018, 27, 1096–1110.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricklin, D.; Lambris, J.D. Complement in Immune and Inflammatory Disorders: Pathophysiological Mechanisms. J Immunol 2013, 190, 3831–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nell, D.; Wolf, R.; Podgorny, P.M.; Kuschnereit, T.; Kuschnereit, R.; Dabers, T.; Stracke, S.; Schmidt, T.; Nell, D.; Wolf, R.; et al. Complement Activation in Nephrotic Glomerular Diseases. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limgala, R.P.; Fikry, J.; Veligatla, V.; Goker-Alpan, O. The Interaction of Innate and Adaptive Immunity and Stabilization of Mast Cell Activation in Management of Infusion Related Reactions in Patients with Fabry Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 7213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, H.M.A.; Lee, G.H.; Kim, H.-R.; Chae, H.-J. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Associated ROS. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.J.; Kikuchi, D.S.; Hernandes, M.S.; Xu, Q.; Griendling, K.K. Reactive Oxygen Species in Metabolic and Inflammatory Signaling. Circulation Research 2018, 122, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kok, K.; Zwiers, K.C.; Boot, R.G.; Overkleeft, H.S.; Aerts, J.M.F.G.; Artola, M. Fabry Disease: Molecular Basis, Pathophysiology, Diagnostics and Potential Therapeutic Directions. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoldi, G.; Caputo, I.; Driussi, G.; Stefanelli, L.F.; Vico, V.D.; Carraro, G.; Nalesso, F.; Calò, L.A.; Bertoldi, G.; Caputo, I.; et al. Biochemical Mechanisms beyond Glycosphingolipid Accumulation in Fabry Disease: Might They Provide Additional Therapeutic Treatments? Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junjappa, R.P.; Patil, P.; Bhattarai, K.R.; Kim, H.-R.; Chae, H.-J. IRE1α Implications in Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Development and Pathogenesis of Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoncini, C.; Torri, S.; Montano, V.; Chico, L.; Gruosso, F.; Tuttolomondo, A.; Pinto, A.; Simonetta, I.; Cianci, V.; Salviati, A.; et al. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Fabry Disease: Is There a Room for Them? J Neurol 2020, 267, 3741–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttolomondo, A.; Simonetta, I.; Riolo, R.; Todaro, F.; Di Chiara, T.; Miceli, S.; Pinto, A. Pathogenesis and Molecular Mechanisms of Anderson-Fabry Disease and Possible New Molecular Addressed Therapeutic Strategies. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 10088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffer, B.; Lenders, M.; Ehlers-Jeske, E.; Heidenreich, K.; Brand, E.; Köhl, J. Complement Activation and Cellular Inflammation in Fabry Disease Patients despite Enzyme Replacement Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Foundations of Immunometabolism and Implications for Metabolic Health and Disease. Immunity 2017, 47, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.L.; Gao, D.S. Endoplasmic Reticulum Proteins Quality Control and the Unfolded Protein Response: The Regulative Mechanism of Organisms against Stress Injuries. BioFactors 2014, 40, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Gómez, H.; López-Garrido, M. Systemic Inflammation in Fabry Disease: A Longitudinal Immuno-Genetic Analysis Based on Variant Stratification. Ther Adv Rare Dis 2025, 6, 26330040251375496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhao, M.-H. Complement in Glomerular Diseases. Nephrology (Carlton) 2018, 23 Suppl 4, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feriozzi, S.; Rozenfeld, P. The Inflammatory Pathogenetic Pathways of Fabry Nephropathy. rdodj 2024, 3, N/A–N/A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetta, I.; Tuttolomondo, A.; Daidone, M.; Pinto, A. Biomarkers in Anderson-Fabry Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 8080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlina, A.; Brand, E.; Hughes, D.; Kantola, I.; Krӓmer, J.; Nowak, A.; Tøndel, C.; Wanner, C.; Spada, M. An Expert Consensus on the Recommendations for the Use of Biomarkers in Fabry Disease. Mol Genet Metab 2023, 139, 107585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnicer-Cáceres, C.; Arranz-Amo, J.A.; Cea-Arestin, C.; Camprodon-Gomez, M.; Moreno-Martinez, D.; Lucas-Del-Pozo, S.; Moltó-Abad, M.; Tigri-Santiña, A.; Agraz-Pamplona, I.; Rodriguez-Palomares, J.F.; et al. Biomarkers in Fabry Disease. Implications for Clinical Diagnosis and Follow-Up. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M.M.; Dao, J.; Slayeh, O.A.; Friedman, A.; Goker-Alpan, O. Circulated TGF-Β1 and VEGF-A as Biomarkers for Fabry Disease-Associated Cardiomyopathy. Cells 2023, 12, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auray-Blais, C.; Lavoie, P.; Boutin, M.; Ntwari, A.; Hsu, T.-R.; Huang, C.-K.; Niu, D.-M. Biomarkers Associated with Clinical Manifestations in Fabry Disease Patients with a Late-Onset Cardiac Variant Mutation. Clin. Chim. Acta 2017, 466, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, W.E.; Doykov, I.; Spiewak, J.; Hallqvist, J.; Mills, K.; Nowak, A. Global Glycosphingolipid Analysis in Urine and Plasma of Female Fabry Disease Patients. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2019, 1865, 2726–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutin, M.; Menkovic, I.; Martineau, T.; Vaillancourt-Lavigueur, V.; Toupin, A.; Auray-Blais, C. Separation and Analysis of Lactosylceramide, Galabiosylceramide, and Globotriaosylceramide by LC-MS/MS in Urine of Fabry Disease Patients. Anal Chem 2017, 89, 13382–13390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biancini, G.B.; Vanzin, C.S.; Rodrigues, D.B.; Deon, M.; Ribas, G.S.; Barschak, A.G.; Manfredini, V.; Netto, C.B.O.; Jardim, L.B.; Giugliani, R.; et al. Globotriaosylceramide Is Correlated with Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Fabry Patients Treated with Enzyme Replacement Therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1822, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancini, G.B.; Jacques, C.E.; Hammerschmidt, T.; de Souza, H.M.; Donida, B.; Deon, M.; Vairo, F.P.; Lourenço, C.M.; Giugliani, R.; Vargas, C.R. Biomolecules Damage and Redox Status Abnormalities in Fabry Patients before and during Enzyme Replacement Therapy. Clin Chim Acta 2016, 461, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimarchi, H.; Canzonieri, R.; Schiel, A.; Politei, J.; Costales-Collaguazo, C.; Stern, A.; Paulero, M.; Rengel, T.; Valiño-Rivas, L.; Forrester, M.; et al. Expression of UPAR in Urinary Podocytes of Patients with Fabry Disease. Int J Nephrol 2017, 2017, 1287289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.J.; Jung, N.; Park, J.-W.; Park, H.-Y.; Jung, S.-C. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Kidney Tubular Epithelial Cells Induced by Globotriaosylsphingosine and Globotriaosylceramide. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0136442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doykov, I.D.; Heywood, W.E.; Nikolaenko, V.; Śpiewak, J.; Hällqvist, J.; Clayton, P.T.; Mills, P.; Warnock, D.G.; Nowak, A.; Mills, K. Rapid, Proteomic Urine Assay for Monitoring Progressive Organ Disease in Fabry Disease. Journal of Medical Genetics 2020, 57, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidemann, F.; Beer, M.; Kralewski, M.; Siwy, J.; Kampmann, C. Early Detection of Organ Involvement in Fabry Disease by Biomarker Assessment in Conjunction with LGE Cardiac MRI: Results from the SOPHIA Study. Mol Genet Metab 2019, 126, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habe, K.; Wada, H.; Higashiyama, A.; Akeda, T.; Tsuda, K.; Mori, R.; Kakeda, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Ohishi, K.; Yamanaka, K.; et al. The Plasma Levels of ADAMTS-13, von Willebrand Factor, VWFpp, and Fibrin-Related Markers in Patients With Systemic Sclerosis Having Thrombosis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2018, 24, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riillo, C.; Bonapace, G.; Moricca, M.T.; Sestito, S.; Salatino, A.; Concolino, D. C. 376A>G, (p.Ser126Gly) Alpha-Galactosidase A Mutation Induces ER Stress, Unfolded Protein Response and Reduced Enzyme Trafficking to Lysosome: Possible Relevance in the Pathogenesis of Late-Onset Forms of Fabry Disease. Mol Genet Metab 2023, 140, 107700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Niño, M.D.; Carpio, D.; Sanz, A.B.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Mezzano, S.; Ortiz, A. Lyso-Gb3 Activates Notch1 in Human Podocytes. Hum Mol Genet 2015, 24, 5720–5732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cammarata, G.; Scalia, S.; Colomba, P.; Zizzo, C.; Pisani, A.; Riccio, E.; Montalbano, M.; Alessandro, R.; Giordano, A.; Duro, G. A Pilot Study of Circulating MicroRNAs as Potential Biomarkers of Fabry Disease. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 27333–27345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, K.; Lu, D.; Hoepfner, J.; Santer, L.; Gupta, S.; Pfanne, A.; Thum, S.; Lenders, M.; Brand, E.; Nordbeck, P.; et al. Circulating MicroRNAs in Fabry Disease. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 15277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyndon, D.; Davagnanam, I.; Wilson, D.; Jichi, F.; Merwick, A.; Bolsover, F.; Jager, H.R.; Cipolotti, L.; Wheeler-Kingshott, C.; Hughes, D.; et al. MRI-Visible Perivascular Spaces as an Imaging Biomarker in Fabry Disease. J Neurol 2021, 268, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camporeale, A.; Pieroni, M.; Pieruzzi, F.; Lusardi, P.; Pica, S.; Spada, M.; Mignani, R.; Burlina, A.; Bandera, F.; Guazzi, M.; et al. Predictors of Clinical Evolution in Prehypertrophic Fabry Disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2019, 12, e008424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, M.; Brand, E. Fabry Disease: The Current Treatment Landscape. Drugs 2021, 81, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treatment of Fabry’s Disease with the Pharmacologic Chaperone Migalastat | New England Journal of Medicine. Available online: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1510198 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Kant, S.; Atta, M.G. Therapeutic Advances in Fabry Disease: The Future Awaits. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2020, 131, 110779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.E.; Roy, A.; Geberhiwot, T.; Gehmlich, K.; Steeds, R.P. Fabry Disease: Insights into Pathophysiology and Novel Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinet, W.; Verheye, S.; De Meyer, G.R.Y. Everolimus-Induced MTOR Inhibition Selectively Depletes Macrophages in Atherosclerotic Plaques by Autophagy. Autophagy 2007, 3, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramés, B.; Hasegawa, A.; Taniguchi, N.; Miyaki, S.; Blanco, F.J.; Lotz, M. Autophagy Activation by Rapamycin Reduces Severity of Experimental Osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2012, 71, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catanesi, M.; d’Angelo, M.; Tupone, M.G.; Benedetti, E.; Giordano, A.; Castelli, V.; Cimini, A.; Catanesi, M.; d’Angelo, M.; Tupone, M.G.; et al. MicroRNAs Dysregulation and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankel, L.B.; Di Malta, C.; Wen, J.; Eskelinen, E.-L.; Ballabio, A.; Lund, A.H. A Non-Conserved MiRNA Regulates Lysosomal Function and Impacts on a Human Lysosomal Storage Disorder. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderluh, M.; Berti, F.; Bzducha-Wróbel, A.; Chiodo, F.; Colombo, C.; Compostella, F.; Durlik, K.; Ferhati, X.; Holmdahl, R.; Jovanovic, D.; et al. Emerging Glyco-Based Strategies to Steer Immune Responses. The FEBS Journal 2021, 288, 4746–4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevriaux, A.; Pilot, T.; Derangère, V.; Simonin, H.; Martine, P.; Chalmin, F.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Rébé, C. Cathepsin B Is Required for NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Macrophages, Through NLRP3 Interaction. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.R.; Wise, A.F.; Tindoy, E.; Bruell, S.; Fuller, M.; Nicholls, K.M.; Ricardo, S.D. Investigating Lysosomal Dysfunction in Fabry Disease Using Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Podocytes. jtgg 2025, 9, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerischer, L.; Stascheit, F.; Mönch, M.; Doksani, P.; Dusemund, C.; Herdick, M.; Mergenthaler, P.; Stein, M.; Suboh, A.; Schröder-Braunstein, J.; et al. Inhibition of Classical and Alternative Complement Pathway by Ravulizumab and Eculizumab. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, G. de D.; Boldrini, V.O.; Mader, S.; Kümpfel, T.; Meinl, E.; Damasceno, A. Ravulizumab and Other Complement Inhibitors for the Treatment of Autoimmune Disorders. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2025, 95, 106311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Györfi, A.H.; Matei, A.-E.; Distler, J.H.W. Targeting TGF-β Signaling for the Treatment of Fibrosis. Matrix Biology 2018, 68–69, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haliga, R.E.; Cojocaru, E.; Sîrbu, O.; Hrițcu, I.; Alexa, R.E.; Haliga, I.B.; Șorodoc, V.; Coman, A.E.; Haliga, R.E.; Cojocaru, E.; et al. Immunomodulatory Effects of RAAS Inhibitors: Beyond Hypertension and Heart Failure. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino Cardenas, C.L.; Henaoui, I.S.; Courcot, E.; Roderburg, C.; Cauffiez, C.; Aubert, S.; Copin, M.-C.; Wallaert, B.; Glowacki, F.; Dewaeles, E.; et al. MiR-199a-5p Is Upregulated during Fibrogenic Response to Tissue Injury and Mediates TGFbeta-Induced Lung Fibroblast Activation by Targeting Caveolin-1. PLoS Genet 2013, 9, e1003291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kura, B.; Kalocayova, B.; Devaux, Y.; Bartekova, M. Potential Clinical Implications of MiR-1 and MiR-21 in Heart Disease and Cardioprotection. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MicroRNAs in Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Diseases: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Opportunities - Ma - 2024 - The FASEB Journal - Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://faseb.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1096/fj.202401464R (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Singh, J.; Santosh, P.; Ramaswami, U. Epigenetic Mechanisms in Fabry Disease: A Thematic Analysis Linking Differential Methylation Profiles and Genetic Modifiers to Disease Phenotype. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2025, 47, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).