Submitted:

07 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Neurodegenerative Diseases (NDDs)

1.1.1. Definition and Epidemiology

1.1.2. Key Pathophysiological Hallmarks

1.1.3. Specific NDDs Associated with Microbiome Dysbiosis

- Parkinson’s Disease (PD): Altered gut microbiota composition has been linked to both motor and non-motor symptoms of PD. Studies suggest that microbial dysbiosis precedes the clinical manifestation of the disease, making it a potential biomarker for early detection [10]. Key findings include an increased abundance of Enterobacteriaceae, which is associated with inflammation and oxidative stress, and reduced populations of Prevotellaceae, which play a role in mucin production and gut barrier maintenance. These microbial imbalances contribute to neuroinflammation, alpha-synuclein aggregation, and the progression of PD [11].

- Alzheimer’s Disease (AD): Changes in gut microbial communities have been associated with amyloid-beta deposition and cognitive decline, implicating the gut microbiota in AD pathogenesis. Dysbiosis leads to reduced production of SCFAs, which are critical for maintaining gut barrier integrity and preventing the translocation of pro-inflammatory molecules like LPS into systemic circulation [12]. Elevated levels of LPS in the blood have been linked to neuroinflammation and amyloid-beta accumulation, suggesting that targeting the gut microbiome could mitigate AD progression [13,74].

- Multiple System Atrophy (MSA): Preliminary findings indicate that gut dysbiosis may contribute to neuroinflammation and autonomic dysfunction in MSA. While research in this area is still in its infancy, the observed microbial alterations provide valuable insights into the role of the gut-brain axis in this rare but devastating condition [14].

1.2. The Gut Microbiome: Definition and Importance

1.2.1. Definition of Microbiota and Microbiome

1.2.2. Role in Homeostasis

- Immune Regulation: The microbiota educates and modulates the immune system, promoting tolerance to commensal microbes while defending against pathogens. It also primes innate and adaptive immunity, ensuring a balanced response to infections and preventing autoimmune reactions [20].

- Metabolic Activities: Gut microbes facilitate the breakdown of complex carbohydrates, fiber, and other indigestible compounds, producing beneficial metabolites such as SCFAs. These metabolites serve as energy sources for colonocytes, regulate gene expression, and exert anti-inflammatory effects. Additionally, the microbiota synthesizes essential vitamins, including B vitamins and vitamin K, which are critical for various physiological processes [21].

- Colonization Resistance: By outcompeting harmful pathogens for nutrients and attachment sites, the gut microbiota provides a protective barrier against infections. This colonization resistance is particularly important for preventing the overgrowth of opportunistic pathogens like Clostridioides difficile [22].

- Energy Balance and Intestinal Homeostasis: The microbiota influences energy harvest, fat storage, and the maintenance of gut barrier integrity. It prevents systemic inflammation caused by bacterial translocation, thereby safeguarding overall health [23].

1.2.3. Dysbiosis

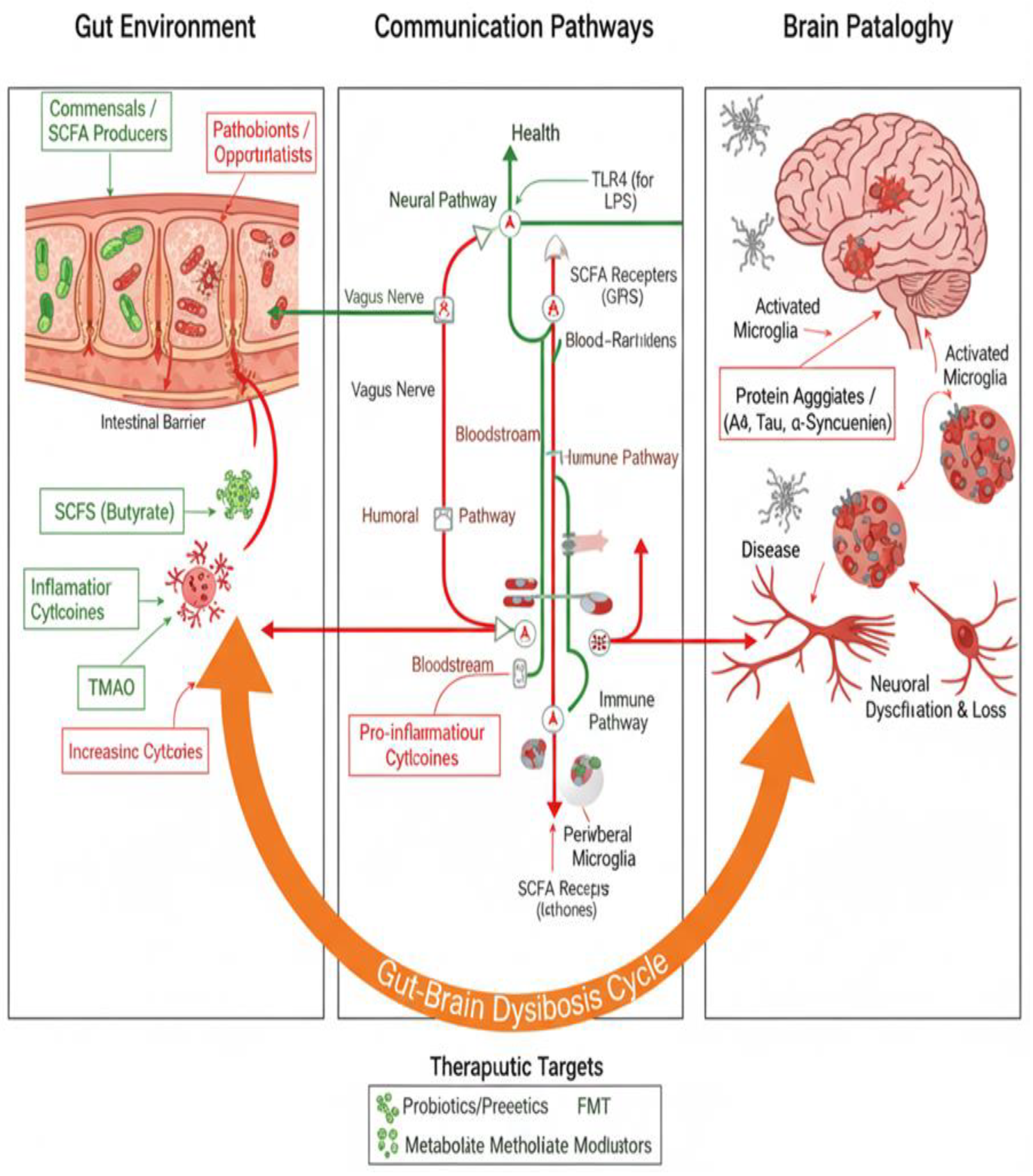

1.3. The Gut–Brain Axis (GBA): Concept and Relevance

1.3.1. Conceptual Framework

- Neural Pathways: The vagus nerve serves as a primary conduit for transmitting signals between the gut and brain. Recent research has demonstrated that microbial metabolites such as SCFAs and bile acids activate vagal afferent neurons in a receptor-dependent manner, enabling the gut microbiome to modulate chemosensory signals transmitted to the brain [47].

- Endocrine Pathways: Hormones and neurotransmitters produced by gut microbes influence CNS activity. For example, serotonin—a neurotransmitter critical for mood regulation—is predominantly synthesized in the gut, where it interacts with enterochromaffin cells and vagal afferents [48].

- Immunological Pathways: Cytokines and other immune mediators modulate neuroinflammation and brain function. Dysbiosis can disrupt this balance, leading to systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation [49].

1.3.2. Emerging Role

1.3.3. Dysbiosis via the GBA

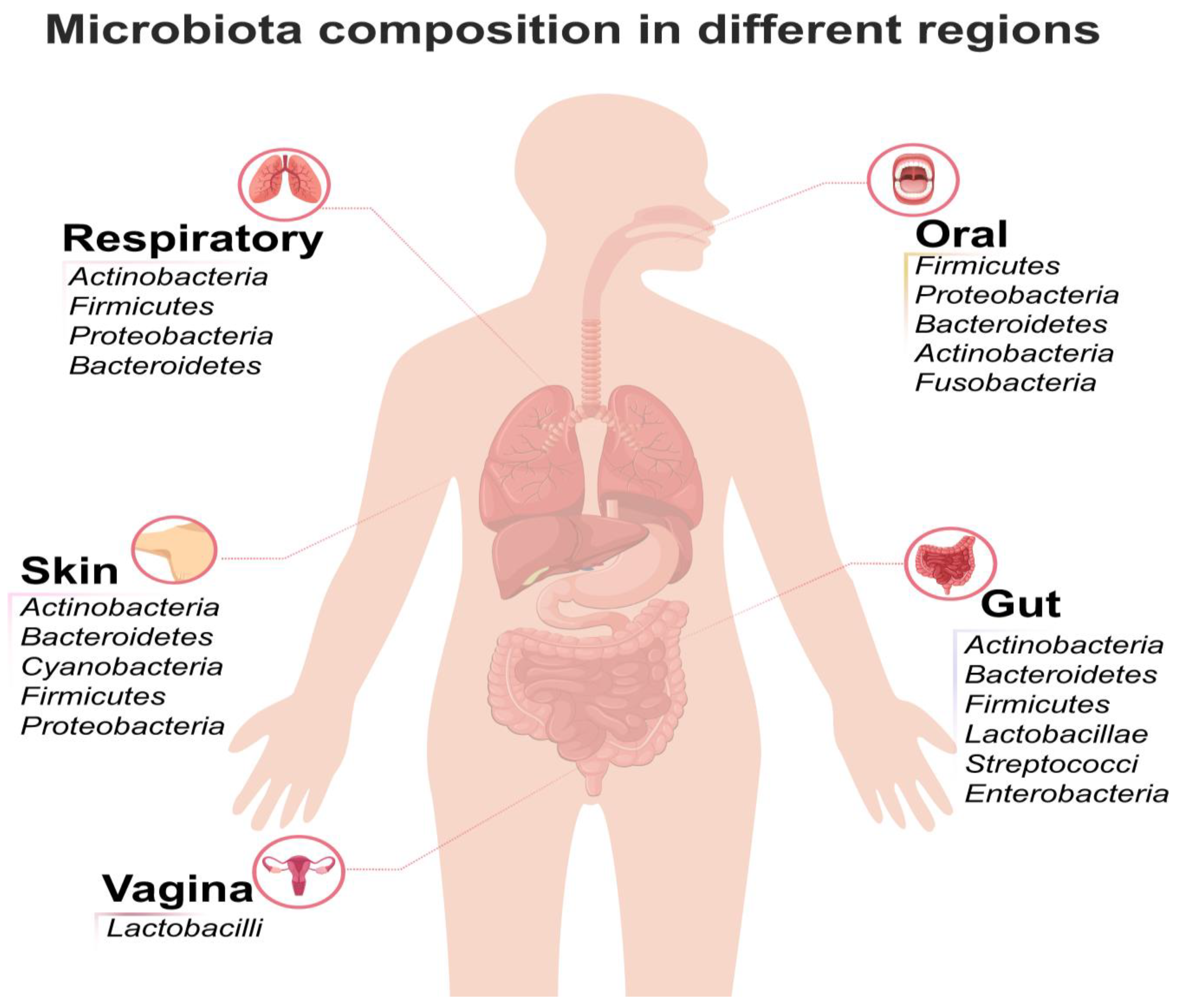

2. Composition and Structure of the Gut Microbiome

2.1. Key Microbial Components and Genetic Scale

- The human gut microbiota represents the highest species diversity and quantity of microorganisms in the body.

- The number of microbial cells in the gut is estimated to be 10–100 trillion.

- The microbial density in the colon reaches up to 1012 cells per gram of intestinal material [57].

2.2. Dominant Bacterial Phyla and Genera

| Phylum | General Characteristics and Abundance |

| Firmicutes | Along with Bacteroidetes, they make up more than 90% of the entire gut population. Firmicutes alone constitute approximately 70% of the total gut bacteria population [58]. |

| Bacteroidetes | The second predominant phylum, making up about 23% of the total gut bacteria. They are highly conserved across individuals. [59] |

- Species belonging to the Firmicutes group, such as Ruminococcus, Eubacterium, and Clostridium, are highly prevalent.

- Other dominant genera in the large intestine include Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Propionibacterium, Peptostreptococcus, and Ruminococcus [61].

- The microbial environment is overwhelmingly dominated by anaerobic bacteria, accounting for about 99% of the bacteria in the gut [62].

2.3. Anatomical Distribution of Microbiota

| Location | Characteristics and Dominant Taxa |

| Stomach and Small Intestine | These areas have a lower species count and diversity compared to the colon. The most abundant phyla here tend to be Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, which can withstand lower pH and other factors. Commonly found genera include Prevotella, Veillonella, and Streptococcus [63]. |

| Large Intestine (Colon) | This region is home to the most dense and diverse microbial community. Anaerobic conditions here provide an ideal environment for anaerobic growth. Most microbial biomass and metabolism occur in the luminal contents of the large intestine [64]. |

2.4. Variability and Factors Influencing Composition

- Inter-Individual Variability: Although the major phyla (Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes) are highly conserved in virtually all individuals, the relative proportions of these two phyla can vary dramatically among healthy people, ranging from 10% to 90%. The variation in flora between individuals is undeniable [65].

- Host Factors: The nature of the symbiotic relationship is intricately influenced by age, genetic makeup, the host’s immune status, and environmental factors.

- Diet: Diet is a significant factor in shaping the gut microbiota. Dietary choices, such as adherence to plant-based diets versus the Western diet, profoundly affect the community structure [66].

- Disease and Dysbiosis: Dysbiosis, characterized by a reduction in beneficial species or a decrease in overall diversity, is associated with the onset and progression of numerous diseases, including infectious diseases, metabolic disorders (like obesity and type 2 diabetes), autoimmune diseases, and cancer [67].

- Stability: While the structure and function of gut microbiota tend to be stable in adult humans, events such as antibiotic treatments and diseases can cause alterations. However, the notion that an individual’s microbiome will be universally stable is one of the common pitfalls in clinical expectations [68].

3. The Gut–Brain Axis: Communication Mechanisms

3.1. Neural Pathways (Vagus Nerve and ENS)

- Meissner’s Plexus: Located in the intestinal submucosa, this network regulates secretory functions.

- Auerbach’s Plexus: Found in the muscular layer of the gut, it governs peristalsis and other motor functions [86].

3.2. Humoral and Metabolic Pathways

- SCFAs represent a valuable source of energy for host cells.

- SCFAs (alongside bile acids) are key activators of vagal neurons.

- SCFA acetate promotes the proliferation of human neural progenitor cells.

| Component | Origin | Function/Role in Disease | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) (e.g., Butyrate, Acetate) | Produced by gut bacteria via fermentation of dietary fibers. | Protective: Maintain integrity of the mucosal barrier and tight junctions. Flow to the liver via portal circulation, reducing hepatic inflammatory injury. Drive NLRP6 inflammasomes. | [29,40,75] |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Component of microbe-derived Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs). | Inflammatory/Pathogenic: Recognised by TLR receptors, activating NF-κB. Flows via the portal vein to the liver, activating Kupffer cells and initiating immunoregulatory programs. | [13,74] |

| Bile Acids (BAs) / Secondary BAs | Primary BAs synthesized in the liver; converted to Secondary BAs (SBAs) by intestinal microorganisms. | Metabolic/Immune Modulators: SBAs have weaker NK cell activation ability than primary BAs, potentially favoring tumor proliferation. | [93,94] |

3.3. Immune and Inflammatory Pathways

- LPS (Lipopolysaccharide): Microbe-derived factors, including LPS, a structural part of Gram-negative bacteria, are recognized as Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs) by Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs).

- Increased Intestinal Permeability (“Leaky Gut”): Dysbiosis leads to intestinal barrier destruction. Increased gut permeability enhances the absorption of LPS. Bacterial products and PAMPs enter the portal circulation and access the liver.

- Inflammatory Activation: PAMPs, such as LPS, bind to Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (e.g., TLR4) on immune cells, such as Kupffer cells in the liver. This binding activates inflammatory pathways. The binding of LPS to TLR4 on intestinal epithelial cells, triggering the TLR4–MyD88 pathway, also stimulates the NF-κB pathway [97].

- Toxic Effect on CNS: The synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines can be induced by LPS. Pro-inflammatory cytokines have a toxic effect on the central nervous system (CNS).

- Specific Cytokines: Activation of Kupffer cells and other immune cells promotes the release of inflammatory mediators, such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6). These are major contributors to the inflammatory cascade [98].

4. Microbiota Dysbiosis in Specific Neurodegenerative Diseases

4.1. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

4.2. Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

- Increased abundance of Enterobacteriaceae, which is associated with inflammation and oxidative stress [11].

4.3. Other Neurological and Nervous System Diseases

- Parkinson’s Disease (PD): As discussed earlier, PD exhibits distinct microbial alterations.

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS): MS is characterized by autoimmune-mediated damage to the CNS, with gut microbiota playing a role in modulating immune responses. Meta-analyses have highlighted the link between microbial dysbiosis and MS progression.

- Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD): Altered gut microbiota composition has been associated with behavioral and cognitive symptoms in ASD, emphasizing the gut–brain axis’s role in neurodevelopmental disorders [102].

- Autoimmune Diseases (e.g., IBD, RA, SLE): These conditions exhibit consistent microbial changes, including enrichment of genera such as Enterococcus, Veillonella, Streptococcus, and Lactobacillus, alongside depletion of beneficial taxa like Ruminococcus, Faecalibacterium, and Butyricicoccus [69,70].

- Nervous System Diseases (e.g., MS, PD): In contrast, microbial alterations in nervous system diseases appear more heterogeneous, with no consistent markers identified across the category. This heterogeneity suggests that the microbiomes associated with NDDs are highly individualized and influenced by factors such as genetics, environmental exposures, and disease stage [2,9].

5. Mechanisms of Molecular Action

5.1. Role of SCFAs and Neuroactive Metabolites

- Butyrate as an HDAC Inhibitor: Butyrate is a potent HDAC inhibitor that suppresses the activities of HDAC1 and HDAC2. This inhibition can activate tumor suppressor genes while repressing oncogenes, reducing the risk of tumorigenesis. Butyrate has also been shown to promote apoptosis and inhibit cancer cell proliferation. Additionally, SCFAs modulate T-cell receptor signaling in cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, enhancing anti-PD-1 anti-tumor efficacy [104].

- Chemosensory Signals: These metabolites enable the microbial modulation and transmission of chemosensory signals from the gut to the brain [47].

- Target Specificity: Serial perfusion of each metabolite class activates both shared and distinct neuronal subsets within the vagus nerve, demonstrating varied response kinetics. Metabolite-induced increases in vagal activity correspond with the activation of brainstem neurons, confirming a direct gut-to-brain communication pathway [26].

5.2. Impact on Barrier Integrity (Gut and CNS)

- Direct mucolytic activity, acetaldehyde production by microbiota from ethanol metabolism, or activation of the NF-κB pathway by bacterial products can damage the intestinal barrier [97].

- Increased intestinal permeability, commonly referred to as “leaky gut,” facilitates the translocation of bacterial products like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and other Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs) into systemic circulation [105].

- SCFAs regulate the balance between the function and morphology of the mucosal barrier, protect tight junctions, and maintain barrier permeability [23].

- SCFA-Specific Roles: Butyrate is particularly critical for promoting cell regeneration and maintaining intestinal barrier function. Supplementation with SCFAs can restore a damaged intestinal barrier.

- Therapeutic Relevance: Probiotic strains such as Lactobacillus improve intestinal barrier integrity, reducing bacterial translocation across the mucosa and mitigating systemic inflammation [69].

- In the liver, PAMPs like LPS bind to Toll-like receptors (TLRs) on immune cells, such as Kupffer cells, activating inflammatory pathways via the NF-κB pathway [105].

- This activation induces the production of pro-inflammatory mediators, including Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6) [98].

- Pro-inflammatory cytokines have toxic effects on the CNS, contributing to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. For example, endogenous alcohol (produced by gut bacteria) and LPS translocation are hypothesized to exacerbate conditions like nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and neurodegenerative diseases [6,9,11].

6. Therapeutic Approaches Targeting the Microbiome

6.1. Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics

- Immune Modulation: Probiotics regulate immune responses by influencing cytokine production and promoting an anti-inflammatory state. They also modulate immune cells and intestinal epithelia, mitigating dysbiosis-related illnesses [108].

- Barrier Integrity: Strains like Lactobacillus strengthen the intestinal barrier, reducing bacterial translocation and systemic inflammation.

- Antimicrobial Production: Probiotics produce antimicrobial agents (e.g., bacteriocins) that inhibit pathogenic microbes [107].

- Neurotransmitter Influence: Probiotics synthesize neurotransmitters such as serotonin, GABA, and dopamine, impacting mood regulation and neuroimmunological conditions [109].

- Mechanism: Prebiotics serve as substrates for beneficial microbes like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacilli, promoting the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [112].

- Relevance: Prebiotics enhance gut health and systemic well-being by supporting microbial balance, digestion, and immune function. For example, dietary fiber supplementation increases sensitivity to PD-1 inhibitors by suppressing regulatory T cells (Tregs) [113].

- Limitations: The efficacy of prebiotics depends on the presence of sufficient target bacteria, requiring strict control of inter-individual variability.

- Synergistic Benefits: The prebiotic component supports the survival and activity of probiotic strains, enhancing therapeutic outcomes.

- Clinical Application (Non-NDD): Synbiotics reduce the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis and improve outcomes in ulcerative colitis (UC). They are also explored for cancer prevention [111].

6.2. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

- Neurodegenerative Context: FMT is emerging as a promising therapy for neurological diseases, including Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Multiple Sclerosis (MS) [23].

- Mechanism in Health: FMT introduces diverse beneficial microbes that compete with pathogenic bacteria, restoring metabolic activities like bile acid and SCFA production [31].

- Cancer Context: FMT from donors responsive to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) enhances antitumor immune responses, overcoming resistance to therapies like anti-PD-1 in melanoma patients [113].

6.3. Dietary and Lifestyle Modulation

- Plant-based and Mediterranean Diets (MD): These diets promote gut health and prevent non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Adherence to the MD is associated with a healthy microbiota profile and increased SCFA production [115].

- SCFA Production: High-fiber diets enhance bacterial fermentation, producing beneficial metabolites like SCFAs.

- TMAO Modulation: Plant-based diets lower trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) levels, reducing inflammation and cardiovascular risks. Conversely, Western diets increase TMAO, inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction [95].

- Obesity/Metabolism: Chronic adherence to the MD normalizes gut microbiota actions, paralleling reductions in insulin resistance in obese patients [66].

6.4. Microbiome Engineering and Precision Therapies

- Metabolomics: Focuses on small molecules and metabolic products, providing insights into microbial activities and clinical outcomes.

- Computational Approaches: Machine learning and AI identify microbial biomarkers indicative of disease, enabling personalized interventions. Network analysis uncovers causal relationships, guiding precision medicine [116].

- Synthetic Biology: Engineered microbes (e.g., E. coli, Lactococcus lactis) perform tasks like biosensing, metabolic production, and immune modulation [117].

- CRISPR Technology: CRISPR-based editing enables precise microbiome manipulation, targeting antibiotic-resistant pathogens or delivering anti-cancer agents.

- Targeting Specific Pathogens: Engineered E. coli detects opportunistic pathogens (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and releases targeted bacteriocins, combating infections effectively [117].

7. Future Directions and Conclusion

7.1. Research Gaps and Technological Advancement

- Network Analysis: Network modeling approaches facilitate the exploration of microbial interactions, the consolidation of various forms of data, and the identification of key players, offering a cohesive framework for investigating the complex dynamics of the gut microbiome. Specifically, the application of causal networks can be used to scrutinize relationships relying on observed microecology data or deployed to evaluate the impact of deliberate interventions.

- Multi-omics Integration: Multi-omics network construction provides a multifaceted approach, aggregating data from disparate sources (such as metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and metabolomics) to offer a panoramic view of crucial units. Integrating multi-omics time-series microbiome data to construct dynamic Bayesian networks (DBNs) is a common method that helps dynamically monitor the ever-evolving gut microecological environments [55].

7.2. Clinical Translation and Implementation Challenges

- Standardization and Safety: Establishing robust regulatory frameworks and ethical guidelines is paramount to ensure patient safety and treatment efficacy. Translational applications are often hindered by regulatory hurdles and a lack of standardized protocols. For interventions like FMT, standardized preparation and long-term safety assessment are needed, as its long-term effectiveness and stability remain unclear [118].

- Personalization: Clinicians must overcome the challenge of high inter-individual variability in microbiomes. The gut microbiome exhibits significant heterogeneity in inter-individual differences, which strongly influences therapeutic response rates. This variability suggests that a “one size fits all” approach is often insufficient, necessitating the development of personalized therapeutic strategies guided by individual microbial profiles [119].

8. Conclusions

8.1. Recap Key Insight:

8.2. Outlook:

8.3. Call to Action:

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Menezes, A.A.; Shah, Z.A. A Review of the Consequences of Gut Microbiota in Neurodegenerative Disorders and Aging. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.K.; Chauhan, K.; Bhardwaj, S.; Srivastava, R. Innovative Interventions: Postbiotics and Psychobiotics in Neurodegenerative Disease Treatment. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Wang, S.; Xu, C.; Zhou, X.; Lian, X.; He, L.; Li, K. Gut microbiota, pathogenic proteins and neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 959856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bicknell, B.; Liebert, A.; Borody, T.; Herkes, G.; McLachlan, C.; Kiat, H. Neurodegenerative and Neurodevelopmental Diseases and the Gut-Brain Axis: The Potential of Therapeutic Targeting of the Microbiome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munteanu, C.; Galaction, A.I.; Turnea, M.; Blendea, C.D.; Rotariu, M.; Poștaru, M. Redox Homeostasis, Gut Microbiota, and Epigenetics in Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumpouli, D.; Koumpouli, V.; Koutelidakis, A.E. The Gut–Brain Axis and Neurodegenerative Diseases: The Role of Nutritional Interventions Targeting the Gut Microbiome—A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, F.; Liu, B. Gut microbiota-derived short chain fatty acids act as mediators of the gut–brain axis targeting age-related neurodegenerative disorders: a narrative review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 65, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyan, M.; Tousif, A.H.; Sonali, S.; Vichitra, C.; Sunanda, T.; Praveenraj, S.S.; Ray, B.; Gorantla, V.R.; Rungratanawanich, W.; Mahalakshmi, A.M.; et al. Role of Endogenous Lipopolysaccharides in Neurological Disorders. Cells 2022, 11, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, R.; Arrè, V.; Nardone, S.; Incerpi, S.; Giannelli, G.; Trivedi, P.; Anastasiadou, E.; Negro, R. Gastrointestinal microbiota and inflammasomes interplay in health and disease: a gut feeling. Gut 2025, 75, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.T.; Ramachandran, V.; Joghee, N.M.; Antony, S.; Ramalingam, G. Gut Microbiota Dysfunction as Reliable Non-invasive Early Diagnostic Biomarkers in the Pathophysiology of Parkinson’s Disease: A Critical Review. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2018, 24, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Chen, C.-Y.; Li, Y.-P.; Ke, Y.-C.; Ho, E.-P.; Jeng, C.-F.; Lin, C.-H.; Chen, S.-K. Early Dysbiosis and Dampened Gut Microbe Oscillation Precede Motor Dysfunction and Neuropathology in Animal Models of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2022, 12, 2423–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marizzoni, M.; Cattaneo, A.; Mirabelli, P.; Festari, C.; Lopizzo, N.; Nicolosi, V.; Mombelli, E.; Mazzelli, M.; Luongo, D.; Naviglio, D.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Lipopolysaccharide as Mediators Between Gut Dysbiosis and Amyloid Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 78, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marizzonia, M.; Cattaneob, A.; Mirabellic, P.; Festaria, C.; Lopizzob, N.; Nicolosia, V.; Frisonig, G.B. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Lipopolysaccharide as Mediators Between Gut Dysbiosis and Amyloid Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. Handbook of Microbiome and Gut-Brain-Axis in Alzheimer’s Disease 2022, 9, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Yang, N.; Yang, W.; Chen, B.; Zhu, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Q. Autonomic dysfunction in multiple system atrophy: from pathophysiology to clinical manifestations. Annals of Medicine 2025, 57, 2488111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, N.A.; Ochman, H.; Hammer, T.J. Evolutionary and ecological consequences of gut microbial communities. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 2019, 50, 451–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, G.; Rybakova, D.; Fischer, D.; Cernava, T.; Vergès, M.C.C.; Charles, T.; Schloter, M. Microbiome definition re-visited: old concepts and new challenges. Microbiome 2020, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, A.G.; Wanjari, U.R.; Kannampuzha, S.; Murali, R.; Namachivayam, A.; Ganesan, R.; Gopalakrishnan, A.V. The implication of mechanistic approaches and the role of the microbiome in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a review. Metabolites 2023, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolig, A.S.; Cech, C.; Ahler, E.; Carter, J.E.; Ottemann, K.M. The degree of Helicobacter pylori-triggered inflammation is manipulated by preinfection host microbiota. Infection and immunity 2013, 81, 1382–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrncir, T. Gut microbiota dysbiosis: triggers, consequences, diagnostic and therapeutic options. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkaid, Y.; Harrison, O.J. Homeostatic immunity and the microbiota. Immunity 2017, 46, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liang, Q.; Balakrishnan, B.; Belobrajdic, D.P.; Feng, Q.J.; Zhang, W. Role of dietary nutrients in the modulation of gut microbiota: a narrative review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seekatz, A.M.; Safdar, N.; Khanna, S. The role of the gut microbiome in colonization resistance and recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology 2022, 15, 17562848221134396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiljar, M.; Merkler, D.; Trajkovski, M. The immune system bridges the gut microbiota with systemic energy homeostasis: focus on TLRs, mucosal barrier, and SCFAs. Frontiers in immunology 2017, 8, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belizário, J.E.; Faintuch, J.; Garay-Malpartida, M. Gut microbiome dysbiosis and immunometabolism: new frontiers for treatment of metabolic diseases. Mediators of inflammation 2018, 2018, 2037838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toor, D.; Wasson, M.K.; Kumar, P.; Karthikeyan, G.; Kaushik, N.K.; Goel, C.; Prakash, H. Dysbiosis disrupts gut immune homeostasis and promotes gastric diseases. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenzadeh, A.; Pourasgar, S.; Mohammadi, A.; Nazari, M.; Nematollahi, S.; Karimi, Y.; Elahi, R. The gut microbiota and cardiovascular disease: Exploring the role of microbial dysbiosis and metabolites in pathogenesis and therapeutics. Life Sciences 2025, 123981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 2012, 486, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, N.N.; Forry, S.P.; Servetas, S.L.; Hunter, M.E.; Dootz, J.N.; Dunkers, J.P.; Jackson, S.A. Measuring microbial community-wide antibiotic resistance propagation via natural transformation in the human gut microbiome. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; Siva Venkatesh, I.P.; Basu, A. Short-chain fatty acids in the microbiota–gut–brain axis: role in neurodegenerative disorders and viral infections. ACS chemical neuroscience 2023, 14, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaGreca, M.; Hutchinson, D.R.; Skehan, L. The microbiome and neurotransmitter activity. The Journal of Science and Medicine 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, S.S.; Meganathan, P.; Vedagiri, H. Harmonizing gut microbiota dysbiosis: Unveiling the influence of diet and lifestyle interventions. Metabolism Open 2025, 100384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Useros, N.; Nova, E.; González-Zancada, N.; Díaz, L.E.; Gómez-Martínez, S.; Marcos, A. Microbiota and lifestyle: a special focus on diet. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Saunders, C.; Sanossian, N. Food, gut barrier dysfunction, and related diseases: A new target for future individualized disease prevention and management. Food science & nutrition 2023, 11, 1671–1704. [Google Scholar]

- Nisa, P.; Kirthi, A.V.; Sinha, P. Microbiome-based approaches to personalized nutrition: from gut health to disease prevention. Folia Microbiologica 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kociszewska, D.; Chan, J.; Thorne, P.R.; Vlajkovic, S.M. The link between gut dysbiosis caused by a high-fat diet and hearing loss. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 13177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Tarraf, A. Impact of polyphenols and feeding rhythms on the immunomodulation properties of the probiotic bacteria in the gastro-intestinal tract. Doctoral dissertation, Université Bourgogne Franche-Comté, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.E.; Davis, J.A.; Berk, M.; Hair, C.; Loughman, A.; tle, D.; Marx, W. Efficacy and safety of fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of diseases other than Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut microbes 2020, 12, 1854640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renesteen, E.; Boyajian, J.L.; Islam, P.; Kassab, A.; Abosalha, A.; Makhlouf, S.; Prakash, S. Microbiome Engineering for Biotherapeutic in Alzheimer’s Disease Through the Gut–Brain Axis: Potentials and Limitations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cani, P.D.; Depommier, C.; Derrien, M.; Everard, A.; de Vos, W.M. Akkermansia muciniphila: paradigm for next-generation beneficial microorganisms. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2022, 19, 625–637. [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi, Y.; Baines, K.J.; Vareki, S.M. Microbiome bacterial influencers of host immunity and response to immunotherapy. Cell Reports Medicine 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, DM, III; Cookson; Van Den Bosch, L.; Zetterberg, H.; Holtzman, DM.; Dewachter, I. Hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases. Cell 2023, 186, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 42; Wingo, TS.; Liu, Y.; Gerasimov, ES.; Vattathil, SM.; Wynne, ME.; Liu, J.; (). Shared mechanisms across the major psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voet, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Lamkanfi, M.; van Loo, G. Inflammasomes in neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. EMBO Mol Med. 2019, 43 11, e10248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, AL.; Bessho, S.; Grando, K.; Tükel, Ç. Microbiome or infections: amyloid-containing biofilms as a trigger for complex human diseases. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 638867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Round, JL.; Mazmanian, SK. Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 12204–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakshi, I.; Dey, S.; Raut, A.J.; Katta, S.; Sharma, P. Exploring the Gut-Brain Axis: A Comprehensive Review of Interactions Between the Gut Microbiota and the Central Nervous System. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research 2024, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ni Dhonnabhain, R.; Xiao, Q.; O’Malley, D. Aberrant gut-to-brain signaling in irritable bowel syndrome-the role of bile acids. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2021, 12, 745190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, A.P.; Karianaki, M.; Tsamis, K.I.; Paschou, S.A. The role of the gut-brain axis in depression: endocrine, neural, and immune pathways. Hormones 2021, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, R.; Karande, A.; Ranganathan, P. Emerging role of gut microbiota dysbiosis in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Frontiers in Neurology 2023, 14, 1149618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, P.; Vishwakarma, R.K.; Pathak, A. The Gut-Brain Axis (GBA): Implications for Brain Longevity. In Rejuvenating the Brain: Nutraceuticals, Autophagy, and Longevity; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2025; pp. 219–268. [Google Scholar]

- Samarani, M.; Loberto, N.; Murdica, V.; Schiumarini, D.; Prioni, S.; Prinetti, A.; Aureli, M. Glycohydrolases in the central nervous system: the role of GBA2 in the neuronal differentiation. SpringerPlus 2015, 4 Suppl 1, P42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Scuderi, S.A.; Capra, A.P.; Giosa, D.; Bonomo, A.; Ardizzone, A.; Esposito, E. An Updated and Comprehensive Review Exploring the Gut–Brain Axis in Neurodegenerative Disorders and Neurotraumas: Implications for Therapeutic Strategies. Brain Sciences 2025, 15, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, P.; Vishwakarma, R.K.; Pathak, A. The Gut-Brain Axis (GBA): Implications for Brain Longevity. In Rejuvenating the Brain: Nutraceuticals, Autophagy, and Longevity; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2025; pp. 219–268. [Google Scholar]

- García-López, R.; Pérez-Brocal, V.; Moya, A. Beyond cells–The virome in the human holobiont. Microbial Cell 2019, 6, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Sun, J. Applied Microbiome Statistics: Correlation, Association, Interaction and Composition; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.X.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Chen, Z.S. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, X.; Li, L. Human gut microbiome: the second genome of human body. Protein & cell 2010, 1, 718–725. [Google Scholar]

- Colella, M.; Charitos, I.A.; Ballini, A.; Cafiero, C.; Topi, S.; Palmirotta, R.; Santacroce, L. Microbiota revolution: How gut microbes regulate our lives. World journal of gastroenterology 2023, 29, 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccioni, A.; Rosa, F.; Manca, F.; Pignataro, G.; Zanza, C.; Savioli, G.; Candelli, M. Gut microbiota and clostridium difficile: what we know and the new frontiers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 13323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doytchinov, V.V.; Dimov, S.G. Microbial community composition of the Antarctic ecosystems: Review of the bacteria, fungi, and archaea identified through an NGS-based metagenomics approach. Life 2022, 12, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What is the healthy gut microbiota composition? A changing ecosystem across age, environment, diet, and diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedantam, G.; Hecht, D.W. Antibiotics and anaerobes of gut origin. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2003, 6, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, G.T.; Macfarlane, S. Human colonic microbiota: ecology, physiology and metabolic potential of intestinal bacteria. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 1997, 32(sup222), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, A.; Khan, M.R. An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2019, 76, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magne, F; Gotteland, M; Gauthier, L; Zazueta, A; Pesoa, S; Navarrete, P.; Balamurugan, R. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio: A Relevant Marker of Gut Dysbiosis in Obese Patients? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What is the healthy gut microbiota composition? A changing ecosystem across age, environment, diet, and diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.; Kolodziejczyk, A.A.; Thaiss, C.A.; Elinav, E. Dysbiosis and the immune system. Nature Reviews Immunology 2017, 17, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, A.; Ferrer, M. Functional redundancy-induced stability of gut microbiota subjected to disturbance. Trends in microbiology 2016, 24, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellocchi, C.; Fernández-Ochoa, Á.; Montanelli, G.; Vigone, B.; Santaniello, A.; Quirantes-Piné, R.; Beretta, L. Identification of a shared microbiomic and metabolomic profile in systemic autoimmune diseases. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2019, 8, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, G.; Cao, H.; Yu, D.; Fang, X.; de Vos, W.M.; Wu, H. Gut dysbacteriosis and intestinal disease: mechanism and treatment. Journal of applied microbiology 2020, 129, 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syromyatnikov, M.; Nesterova, E.; Gladkikh, M.; Smirnova, Y.; Gryaznova, M.; Popov, V. Characteristics of the gut bacterial composition in people of different nationalities and religions. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.; Cohen, N.A.; Shalev, V.; Uzan, A.; Koren, O.; Maharshak, N. Psoriatic patients have a distinct structural and functional fecal microbiota compared with controls. The Journal of dermatology 2019, 46, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scher, J.U.; Ubeda, C.; Artacho, A.; Attur, M.; Isaac, S.; Reddy, S.M.; Abramson, S.B. Decreased bacterial diversity characterizes the altered gut microbiota in patients with psoriatic arthritis, resembling dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Arthritis & rheumatology 2015, 67, 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- Das, B.K. Altered gut microbiota in hepatocellular carcinoma: Insights into the pathogenic mechanism and preclinical to clinical findings. Apmis 2022, 130, 719–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, R.F.; Greten, T.F. Gut microbiome in HCC Mechanisms, diagnosis and therapy. Journal of hepatology 2020, 72, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, T.; Tu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tan, D.I.; Fang, W. Gut microbiome affects the response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2019, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.C.; Wu, C.J.; Hung, Y.W.; Lee, C.J.; Chi, C.T.; Lee, I.C.; Huang, Y.H. Gut microbiota and metabolites associate with outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitor–treated unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2022, 10, e004779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laface, C.; Lauricella, E.; Ranieri, G.; Ambrogio, F.; Maselli, F.M.; Parlagreco, E.; Numico, G. HCC and Immunotherapy: The Potential Predictive Role of Gut Microbiota and Future Therapeutic Strategies. Onco 2025, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, K.T.; Tan, K.S.W. Mechanistic insights on microbiota-mediated development and progression of esophageal cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljeradat, B.; Kumar, D.; Abdulmuizz, S.; Kundu, M.; Almealawy, Y.F.; Batarseh, D.R.; Weinand, M. Neuromodulation and the gut–brain axis: therapeutic mechanisms and implications for gastrointestinal and neurological disorders. Pathophysiology 2024, 31, 244–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortlek, B.E.; Akan, O.B. Modeling and Analysis of SCFA-Driven Vagus Nerve Signaling in the Gut-Brain Axis via Molecular Communication. IEEE Transactions on Molecular, Biological, and Multi-Scale Communications, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- López-Ojeda, W.; Hurley, R.A. The Vagus Nerve and the Brain-Gut Axis: Implications for Neuropsychiatric Disorders. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2024, 36, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, S.; Rizza, S.; Federici, M. Microbiota-gut-brain axis: relationships among the vagus nerve, gut microbiota, obesity, and diabetes. Acta diabetologica 2023, 60, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jameson, K. Vagal interoception of microbial metabolites from the small intestinal lumen; University of California: Los Angeles, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aljeradat, B.; Kumar, D.; Abdulmuizz, S.; Kundu, M.; Almealawy, Y.F.; Batarseh, D.R.; Weinand, M. Neuromodulation and the gut–brain axis: therapeutic mechanisms and implications for gastrointestinal and neurological disorders. Pathophysiology 2024, 31, 244–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neckel, P.H. Annotated translation of Georg Meissner’s first description of the submucosal plexus. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2023, 35, e14480. [Google Scholar]

- Oyovwi, M.O.; Ajayi, A.F. A comprehensive review on immunological mechanisms amd gut-brain pathways linking gut health and neurological disorders. Discover Medicine 2025, 2, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; Siva Venkatesh, I.P.; Basu, A. Short-chain fatty acids in the microbiota–gut–brain axis: role in neurodegenerative disorders and viral infections. ACS chemical neuroscience 2023, 14, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbari Shiadeh, S.M.; Chan, W.K.; Rasmusson, S.; Hassan, N.; Joca, S.; Westberg, L.; Ardalan, M. Bidirectional crosstalk between the gut microbiota and cellular compartments of brain: Implications for neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders. Translational Psychiatry 2025, 15, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, F.; Liu, B. Gut microbiota-derived short chain fatty acids act as mediators of the gut–brain axis targeting age-related neurodegenerative disorders: a narrative review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2025, 65, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Khalil, A.A.; Rahman, U.U.; Khalid, A.; Naz, S.; Shariati, M.A.; Rengasamy, K.R.R. Recent advances in the therapeutic application of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs): An updated review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 62, 6034–6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dezfouli, M.A.; Rashidi, S.K.; Yazdanfar, N.; Khalili, H.; Goudarzi, M.; Saadi, A.; Kiani Deh Kiani, A. The emerging roles of neuroactive components produced by gut microbiota. Molecular Biology Reports 2025, 52, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, S.L.; Stine, J.G.; Bisanz, J.E.; Okafor, C.D.; Patterson, A.D. Bile acids and the gut microbiota: metabolic interactions and impacts on disease. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023, 21, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrakhovitch, E.A.; Ono, K.; Yamasaki, T.R. Metabolomics in Parkinson’s Disease and Correlation with Disease State. Metabolites 2025, 15, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ge, P.; Luo, Y.; Sun, Z.; Luo, X.; Li, H.; Chen, H. Decoding TMAO in the Gut-Organ Axis: From Biomarkers and Cell Death Mechanisms to Therapeutic Horizons. Drug Design, Development and Therapy 2025, 19, 3363–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krsek, A.; Schleicher, L.M.S.; Jagodic, A.; Baticic, L. Nanomedicine-Driven Modulation of the Gut–Brain Axis: Innovative Approaches to Managing Chronic Inflammation in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 9178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, F.; Liu, B. Gut microbiota-derived short chain fatty acids act as mediators of the gut–brain axis targeting age-related neurodegenerative disorders: a narrative review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2025, 65, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicknell, B.; Liebert, A.; Borody, T.; Herkes, G.; McLachlan, C.; Kiat, H. Neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental diseases and the gut-brain axis: the potential of therapeutic targeting of the microbiome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 9577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Bonfili, L.; Wei, T.; Eleuteri, A.M. Understanding the gut–brain axis and its therapeutic implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N. The molecular interplay between human and bacterial amyloids: Implications in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Proteins and Proteomics 2024, 1872, 141018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, A.; Scuderi, S.A.; Capra, A.P.; Giosa, D.; Bonomo, A.; Ardizzone, A.; Esposito, E. An Updated and Comprehensive Review Exploring the Gut–Brain Axis in Neurodegenerative Disorders and Neurotraumas: Implications for Therapeutic Strategies. Brain Sciences 2025, 15, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moțățăianu, A.; Șerban, G.; Andone, S. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota–gut–brain cross-talk with a focus on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 15094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Fan, X.; Han, B.; Ai, X. Microbial short chain fatty acids: Effective histone deacetylase inhibitors in immune regulation. International journal of molecular medicine 2026, 57, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wei, J.; Ding, Y.; Wang, X.; Hou, H.; Cao, H. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids regulate gastrointestinal tumor immunity: a novel therapeutic strategy? Frontiers in immunology 2023, 14, 1158200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Lee, D.; Mook-Jung, I. Gut microbiota as a hidden player in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2022, 86, 1501–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicknell, B.; Liebert, A.; Borody, T.; Herkes, G.; McLachlan, C.; Kiat, H. Neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental diseases and the gut-brain axis: the potential of therapeutic targeting of the microbiome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 9577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panebianco, C.; Latiano, T.; Pazienza, V. Microbiota manipulation by probiotics administration as emerging tool in cancer prevention and therapy. Frontiers in oncology 2020, 10, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Li, X.; Wu, H.; Xue, D.; Wang, Y.; Guo, R.; Li, H. The current status and prospects of gut microbiota combined with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in the treatment of colorectal cancer: a review. BMC gastroenterology 2025, 25, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R., Gupta, D., Mehrotra, R., & Mago, P. Psychobiotics: the next-generation probiotics for the brain. Current microbiology 2021, 78, 449–463. Olajide, T.S., & Ijomone, O.M. (2025). Targeting gut microbiota as a therapeutic approach for neurodegenerative diseases. Neuroprotection.

- Tomita, Y.; Sakata, S.; Imamura, K.; Iyama, S.; Jodai, T.; Saruwatari, K.; Sakagami, T. Association of Clostridium butyricum therapy using the live bacterial product CBM588 with the survival of patients with lung cancer receiving chemoimmunotherapy combinations. Cancers 2023, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, S.; Choi, T.G.; Kim, S.S. Role of short chain fatty acids in epilepsy and potential benefits of probiotics and prebiotics: targeting “health” of epileptic patients. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaolu, T.J.; Ashaolu, J.O.; Adeyeye, S.A. Fermentation of prebiotics by human colonic microbiota in vitro and short-chain fatty acids production: a critical review. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2021, 130, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, M.U.; Akbar, A.; Ashraf, A.; Yeni, D.K.; Naz, H.; Shahid, M. Microbiome and Neurological Disorders. In Human Microbiome: Techniques, Strategies, and Therapeutic Potential; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; pp. 273–301. [Google Scholar]

- Khoruts, A.; Staley, C.; Sadowsky, M.J. Faecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridioides difficile: mechanisms and pharmacology. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2021, 18, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Di Bella, G.; Veronese, N.; Barbagallo, M. Impact of Mediterranean diet on chronic non-communicable diseases and longevity. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krsek, A.; Schleicher, L.M.S.; Jagodic, A.; Baticic, L. Nanomedicine-Driven Modulation of the Gut–Brain Axis: Innovative Approaches to Managing Chronic Inflammation in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 9178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, A.; Hussain, F.H.N.; Raza, A. Advancing microbiota therapeutics: The role of synthetic biology in engineering microbial communities for precision medicine. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2024, 12, 1511149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelstein, C.A.; Kassam, Z.; Daw, J.; Smith, M.B.; Kelly, C.R. The regulation of fecal microbiota for transplantation: An international perspective for policy and public health. Clinical Research and Regulatory Affairs 2015, 32, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, V.; Singh, S.; Verma, S.; Verma, S.; Rizvi, A.A.; Abbas, M. Targeting the microbiome to improve human health with the approach of personalized medicine: Latest aspects and current updates. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 2024, 63, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Details | Examples/Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Composition of Gut Microbiome | - Dominant phyla: Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. - Other phyla: Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria, Cyanobacteria. - Highly individualized; varies based on diet, age, genetics, and lifestyle. |

- Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes account for ~90% of gut bacteria [27]. - Over 35,000 bacterial species identified [28]. |

| Functions of Gut Microbiome | - Immune Modulation: Educates immune cells, maintains tolerance. - Nutrient Metabolism: Digests complex carbs, produces SCFAs. - Gut Barrier Integrity: Prevents harmful substances from entering bloodstream. - Gut-Brain Axis: Influences mental health. |

- SCFAs (butyrate, propionate, acetate) have anti-inflammatory properties [29]. - Gut microbiome produces neurotransmitters like serotonin [30]. |

| Causes of Dysbiosis | - Antibiotics: Disrupt microbial balance. - Diet: High in processed foods, low in fiber. - Lifestyle: Stress, lack of sleep, sedentary behavior. - Infections: Bacterial or viral infections. |

- Antibiotic use reduces microbial diversity [31]. - High-fat diets promote harmful bacteria [32]. |

| Diseases Linked to Dysbiosis | - Inflammatory Disorders: IBD, IBS, psoriasis. - Cancer: Influences tumor growth and therapy efficacy. - Metabolic Disorders: Obesity, type 2 diabetes. - Mental Health: Anxiety, depression, neurodegenerative diseases. |

- IBD patients show reduced microbial diversity [33]. - Dysbiosis linked to obesity [34]. - Gut-brain axis implicated in depression [35]. |

| Therapeutic Interventions | - Probiotics: Live bacteria that confer health benefits. - Prebiotics: Non-digestible fibers that promote beneficial bacteria. - FMT: Transplants fecal matter from healthy donors. - Dietary Interventions: High-fiber diets, specific herbs. |

- Probiotics like Lactobacillus improve gut barrier function [36]. - FMT has a 90% success rate in treating C. difficile infections [37]. -Pseudostellaria heterophylla improves gut health [38]. |

| Specific Bacteria and Their Roles | - Akkermansia muciniphila: Improves metabolic health, enhances immunotherapy. - Bifidobacterium: Promotes antitumor immunity, treats IBD. - Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: Anti-inflammatory, produces butyrate. |

- Akkermansia improves insulin sensitivity [39]. - Bifidobacterium enhances anti-PD-1 immunotherapy [40]. |

| Gut Microbiome and Cancer | - Influences tumor microenvironment (TME). - Modulates immune responses to immunotherapy. - Specific bacteria enhance or inhibit tumor growth. |

- Bifidobacterium improves response to anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma [41]. - Dysbiosis linked to colorectal cancer [42]. |

| Gut Microbiome and Mental Health | - Produces neurotransmitters (serotonin, GABA). - Influences mood, anxiety, and depression. - Linked to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. |

- Gut-brain axis implicated in anxiety and depression [41]. - SCFAs reduce neuroinflammation [43]. |

| Ethical Considerations for FMT | - Informed Consent: Patients must understand risks and benefits. - Donor Screening: Rigorous screening to prevent disease transmission. - Long-Term Safety: Lack of long-term data on FMT outcomes. |

- FMT has been associated with rare cases of severe infections [44]. - Ethical concerns include donor selection and regulatory oversight [45]. |

| Disease/Clinical Context | Microbial Taxa (Genus/Phylum/Species) | Observed Alteration | Clinical Implication/Mechanism | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoimmune Diseases (Shared Patterns) | Enterococcus, Veillonella, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, Erysipelotrichaceae incertae sedis | Enriched (Increased abundance in patients) | These alterations are notably consistent and strong, indicating a higher homogeneity of microbial markers across different autoimmune diseases compared to other categories (cancer, metabolic, nervous system disease). Enrichment of Enterococcus may drive organ-specific and systemic autoimmunity. | [69,70] |

| Autoimmune Diseases (Shared Patterns) | Ruminococcus, Faecalibacterium, Alistipes, Roseburia, Coprococcus, Oscillibacter (among others) | Depleted (Decreased abundance in patients) | Characteristically depleted genera noted across meta-analyses of autoimmune diseases. | [71] |

| Psoriasis | Firmicutes | Higher prevalence | Characteristic of unique fecal microbial communities observed in psoriasis patients. | [72] |

| Psoriasis | Bacteroidetes | Lower prevalence | Characteristic of unique fecal microbial communities observed in psoriasis patients. | [72} |

| Psoriasis | Ruminococcus and Megasphaera (Firmicutes) | Most significant difference in abundance | Identified as having significantly different abundances in psoriasis cases compared to controls. | [73] |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) Progression | LPS-producing Klebsiella spp. and Haemophilus spp. | Increased | Increased LPS levels boost HCC progression by stimulating the NF-κB pathway and producing pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to hepatic inflammation and oxidative damage. | [74] |

| HCC Progression | Butyrate (Microbial metabolite) | Decreased | Promotes the development of HCC by leading to impaired energy supply to the intestinal mucosa and collapse of regulatory programs in host cells. | [75] |

| HCC Immunotherapy Response (Anti-PD-1) | Akkermansia muciniphila and Ruminococcaceae spp. | Higher abundance (in responsive patients) | Fecal samples from immunotherapy-responsive HCC patients showed a higher abundance of these taxa compared to non-responders, suggesting they are effective markers for predicting clinical response and survival benefit. | [76] |

| HCC Immunotherapy Response (Anti-PD-1) | Lachnoclostridium, Lachnospiraceae, and Veillonella | Predominant (in patients in objective remission) | Found to be predominant in HCC patients who achieved objective remission before receiving immunotherapy. | [77] |

| HCC Immunotherapy Response (Anti-PD-1) | Prevotella 9 | Significantly enriched (in progressive disease) | Associated with progressive forms of HCC disease after immunotherapy. Patients depleted in Prevotella 9 and enriched in Lachnoclostridium showed better Overall Survival (OS) and Progression-Free Survival (PFS). | [78] |

| Esophageal Cancer (ESCC/EAC) | Streptococcus, Veillonella, Prevotella, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Fusobacteria | More abundant | Found to be more common in patients with Esophageal Squamous-Cell Carcinoma (ESCC) and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma (EAC). P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum LPSs stimulate the NF-κB pathway via the TLR-4/MyD88 cascade. | [79] |

| Component | Description | Relevance to the Axis/Diagram | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gut Lumen/Microbiota | The ecosystem containing trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. | Source of microbial factors (PAMPs) and metabolites (SCFAs, BAs) that drive systemic signaling. | [56] |

| Intestinal Barrier / Epithelial Cells (IECs) | The physical boundary, including the protective mucus layer and tight junctions, crucial for maintaining symbiosis. | Integrity disruption allows microbial factors (LPS, PAMPs) to translocate into the host circulation. | [22,27] |

| Enteric Nervous System (ENS) / Vagus Nerve | The nervous component facilitating bidirectional communication, including vagal afferent neurons. | Essential, activity-based evidence for the Gut–Brain Axis (GBA). Vagal activity is regulated by select microbial metabolites in the small intestine. | [47,48] |

| Portal Circulation / Hepatic Portal Vein | The anatomical link connecting the gut to the liver (Gut–Liver Axis). | Transport route for gut-derived products (LPS, SCFAs, BAs) directly to the liver. | [93] |

| Liver | Target organ for systemic immune activation; contains resident immune cells (Kupffer cells). | Site where LPS activates Kupffer cells. Involved in primary bile acid synthesis and metabolism. | [97,98] |

| Central Nervous System (CNS) / Brain | Target organ modulated by the GBA; contains brainstem neurons. | Receives metabolite-induced chemosensory signals transmitted via the vagus nerve. | [47,82] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).