1. Introduction

American Sign Language (ASL) is a vital mode of communication for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (DHH) community [

1,

2]. However, the communication gap between ASL users and non-ASL speakers restricts access to social, educational, and professional settings. Existing approaches are limited, often focusing on static handshapes, isolated ASL alphabets [

3], numbers [

4], or simple voice-to-English text translations [

5]. This gap is further expanded by the fact that not all hearing people know ASL and not all Deaf people know English. Studies have reported that automated solutions often assume that Deaf people in the USA know English [

2]. As a result, there is a lack of systems that can translate ASL to English text and English voice (sounds) to ASL sentences. The development of automated translation systems between ASL and English can address this limitation and help improve inclusivity and accessibility for the DHH community [

6].

This study aims to create an ASL-to-English and English-to-ASL translation system utilizing both computer vision and machine learning techniques. In this study, we used a publicly available dataset; the dataset was sourced from Kaggle and RWTH Aachen University. Our system trains models to recognize ASL signs accurately and convert them into English text or speech. Additionally, we employ a combination between CNN and transformer-based models to help with ASL glossing to convert images to text. Unlike previous work, our system features an easy-to-use and intuitive web interface to translate from ASL to English and vice-versa. This bidirectional approach allows us to translate from an English sentence to sequences of ASL signs, unlike previous ASL translation models which prioritized translation from ASL to English. Users can translate a voice recording into a sequence of ASL signs. The web interface component provides a simple way to expand the current dataset, making it easy to add additional signs/samples. The current approach uses real-time translation, while previous architectures are reliant on static video sequences. The specific contributions of this work are as follows:

Train an NLP-based transformer model using a publicly available dataset and incorporate it with computer vision.

Develop a web based interface to translate ASL to English and English to ASL

Demonstrate advances in gesture recognition, translation accuracy, and system efficiency.

Conduct a case study with the help of Deaf individuals and incorporate feedback from Deaf educators.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides an overview of previous and related work.

Section 3 outlines the methodologies used.

Section 4 and

Section 5 report and discuss the experimental results and challenges encountered.

Section 6 concludes the paper and discusses future directions.

2. Related Work

Prior works in ASL translation technologies center primarily on American Sign Language Recognition (ASLR) and American Sign Language Translation (ASLT) and typically use traditional computer vision methods, deep learning approaches, and linguistically informed frameworks. Most of these works focus on isolated components of the ASL-English translation pipeline.

Earlier notable examples include [

1,

2], which used isolated sign recognition and was constrained by limited datasets that lacked contextual and sentence-level fluency. Traditional methods emphasized hand gesture classification but did not capture full linguistic meaning. The transition to continuous sign language datasets enabled more naturalistic modeling. A major breakthrough came with the RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather dataset and the neural machine translation (NMT) approach in [

7], which used attention-based models to map video input to glosses and written language. The introduction of transformer architectures further improved translation quality across domains. Sign language transformers, combining CTC and attention mechanisms, achieved state-of-the-art performance by integrating recognition and translation [

7,

8]. However, these systems still rely heavily on gloss-level supervision and lack multi-modal or bidirectional capabilities.

Further advances emerged with two key contributions. The Hand-Talk model introduced a multimodal architecture that fused RGB video, optical flow, and hand keypoints for sentence-level ASL translation using a transformer encoder-decoder pipeline [

1]. Follow-up work extended this approach by unifying recognition and translation in a joint CTC-NMT framework, enabling weakly supervised training and improving gloss alignment [

2]. While both works enhanced semantic fluency, they remained limited to one-way translation and did not incorporate audio or support real-time interaction.

Additional innovations explored LSTM-based gesture recognition. For example, Thai Sign Language work in [

9] used Mediapipe to capture full-body landmarks, but the system still performed only one-way gesture-to-text mapping without generative or bidirectional features. In [

10], YOLOv8s enabled high-speed detection and real-time ASL-to-text translation, the focus on hand gestures alone restricted linguistic depth. In the generative AI domain, [

11] compared Feedforward, Convolutional, and Diffusion Autoencoders for ASL alphabet reconstruction, showing diffusion models achieved the highest mean opinion score (MOS). However, this work centered image reconstruction rather than full sequence translation.

This study builds upon these prior contributions by expanding beyond isolated components of the SLR-SLT pipeline. While previous work advanced gesture classification, gloss prediction, or one-way translation, our system unifies and extends these capabilities to support full bidirectional communication.

For multimodal input, we integrate video (ASL), audio (spoken English), and text, using holistic Mediapipe tracking for hands, face, and full-body landmarks, providing richer spatiotemporal context than gesture-only systems.

For bidirectional translation, our system supports both ASL to English and English to ASL, enabling real-time interactive communication rather than one-way output.

For temporal and semantic modeling, we combine transformer and CNN architectures to capture long-range temporal structure and semantic alignment without relying solely on gloss intermediates.

Finally, for real-time scalability, we deploy a working system capable of generalizing to varied environments and future extensions (e.g., AR or wearable hardware), moving beyond controlled, dataset-bound research.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

For training the English-to-Gloss transformer, we used the English-ASL Gloss Parallel Corpus 2012 dataset [

12]. A major challenge in sign language translation is the scarcity of large parallel corpora linking written text to ASL [

13]. The English-ASL Gloss Parallel Corpus 2012 contains over one million English-ASL gloss pairs and supports a range of ASL NLP tasks. Glosses in this corpus are produced through an algorithmic rule-based system verified by linguistic experts, and the texts originate from diverse sources such as news articles, conferences, and classical literature. For our model, we used a subset of approximately 80,000 samples.

For training the Video-to-English transformer, we utilized two datasets: RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather 2014 T [

14] and How2Sign [

15]. RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather 2014 T is a standard benchmark for continuous sign language translation. It contains around 8,200 clips of German weather forecast footage broadcasts recorded between 2009 and 2011 [

14]. Each sample includes a

resolution video at 25 frames per second, gloss annotations, and a corresponding German sentence. While it is true that GSL (German Sign Language) and ASL are completely different, the visual mechanics of signing (the physical movements) are broadly similar across all sign languages. Therefore, the RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather 2014 T dataset can be used to train the CNN-Transformer model [

16,

17]. For our experiments, we used 7,048 samples for training, 515 for validation, and 639 for testing.

How2Sign is a large-scale continuous ASL corpus containing more than 80 hours of videos and 35,000 sentence-aligned English transcriptions. The dataset also provides gloss annotations, extracted keypoints, RGB footage, and depth maps [

15]. For our work, we primarily use RGB video along with sentence and gloss annotations. How2Sign is particularly suitable for our task due to its scale, signer diversity, and focus on continuous ASL.

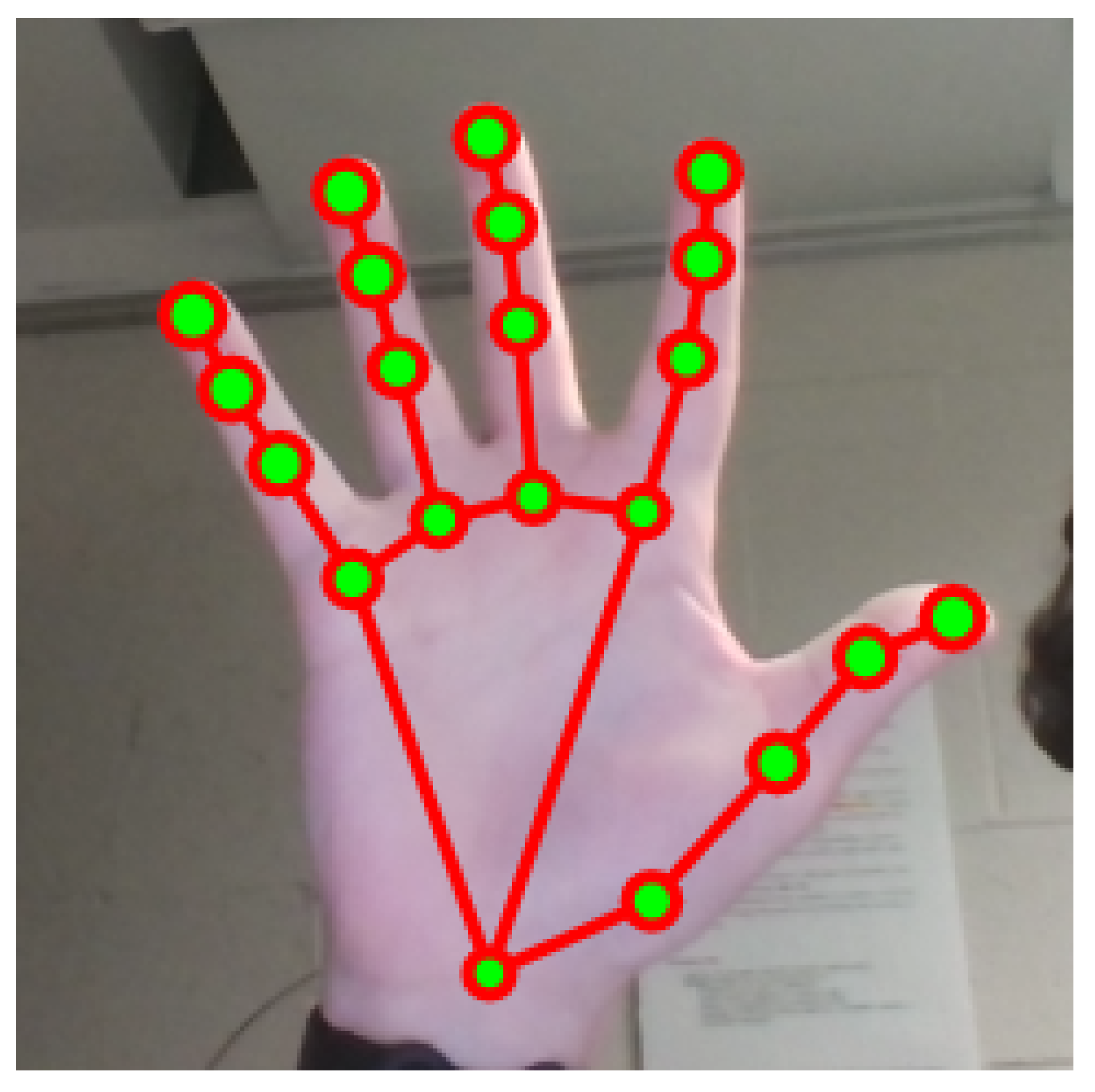

Finally, to support English-to-ASL animation generation, we used the Word-Level American Sign Language dataset (WLASL), which contains over 12,000 videos covering more than 2,000 lexical signs [

18]. For each word, we selected a representative video and extracted full landmark data using MediaPipe (see

Figure 1). These extracted keypoints were stored in MessagePack format for efficient retrieval during ASL animation generation.

3.2. Data Pre-Processing

Before training our models, we preprocess the datasets both prior to and during runtime. For RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather 2014 T, we clean the text and gloss sequences by removing periods as well as excluding samples containing numbers or plus signs.

During training, we apply several video augmentation techniques. First, each video is resized to , then randomly cropped to , followed by color normalization/standardization. We further down-sample the video by selecting every two frames, beginning from either the first or second frame, and we randomly retain 90% of the frames to introduce temporal variation.

For validation and testing, we apply only center cropping (to ) and sample every two frames starting from the first frame, without any additional augmentations. We used center cropping and regular sampling because we want to keep validation augmentation consistent for validation step.

3.3. Model Architectures

In this section, we introduce the two core models used in our system: the English-to-Gloss transformer and the ASL-to-English CNN-Transformer, followed by their training and implementation details.

For video-to-sign translation, we employ a hybrid Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-Transformer model. The CNN model extracts contextual features from individual video frames, while the transformer (now a dominant architecture in Natural Language Processing (NLP) and deep learning) models temporal dependencies and generates glosses and sentences simultaneously. Transformers are widely used across tasks such as language translation, sentiment analysis, and increasingly, computer vision [

19]. Regarding the gloss-to-English translation, we also use a transformer architecture. Compared to LSTMs, transformers offer state-of-the-art performance in machine translation and benefit from parallelized computation, resulting in significantly faster training.

For the ASL-to-English CNN-transformer, first each video frame is processed using a CNN to obtain a feature vector. These feature vectors pass through 1D convolution layers to extract local sequential patterns. The resulting sequence is fed into a transformer to model long-term dependencies across frames. Finally, we applied CTC decoding to the encoder output and greedy decoding to the decoder output.

Figure 2.

Diagram showing the architecture for the ASL-to-English model. The RGB frames are feed through the ASL-to-English model to generate an English sentence.

Figure 2.

Diagram showing the architecture for the ASL-to-English model. The RGB frames are feed through the ASL-to-English model to generate an English sentence.

The English-to-ASL transformer translates an English sentence into a sequence of ASL signs. The sentence is first translated into ASL gloss using the English-to-Gloss transformer. We used MediaPipe Holistic to extact landmark points from videos in the Word-Level American Sign Language (WLASL) dataset, storing them in a custom landmark dataset. Given the predict gloss sequence, we retrieve the corresponding landmark sequences from the dataset to generate an ordered sequence of ASL signs. The training configuration for the gloss-to-English transformer mirrors that of the English-to-Gloss model. This is possible because the architectures are functionally identical; only the source and target sentences from the ASLG-PC12 dataset are reversed.

3.4. Training Setup

For training, we used the Adam optimizer with a batch size of 32, a learning rate of , and a weight decay of for the CNN-Transformer model. The batch size was selected to reduce total training time while keeping GPU memory usage manageable. The learning rate was determined empirically through trial and error to identify the value that produced the best accuracy within the shortest number of epochs.

We trained the CNN-Transformer model on Pittsburg Supercomputing Center’s Bridges-2 supercomputer using four V100-32GB SXM2 GPUs on a single node. For data parallelization, parameter synchronization, and metric aggregation, we used PyTorch’s Distributed Data Parallel (DDP) API.

3.5. Network Details

For the model, we utilize 3 encoder blocks and 3 decoder blocks. For the attention modules, we used 512 hidden units and 8 attention heads. Along with that, we used 2048 hidden units for the transformer block’s feed forward layers. Finally, we employ 0.3 dropout rates in order to mitigate overfitting.

3.6. Interface

A key component of our system is a real-time interface that exposes the model’s capabilities to end users. This interface allows users to interact with the system without needing to run any models locally.

The interface supports three main functions, each accessible through its own page:

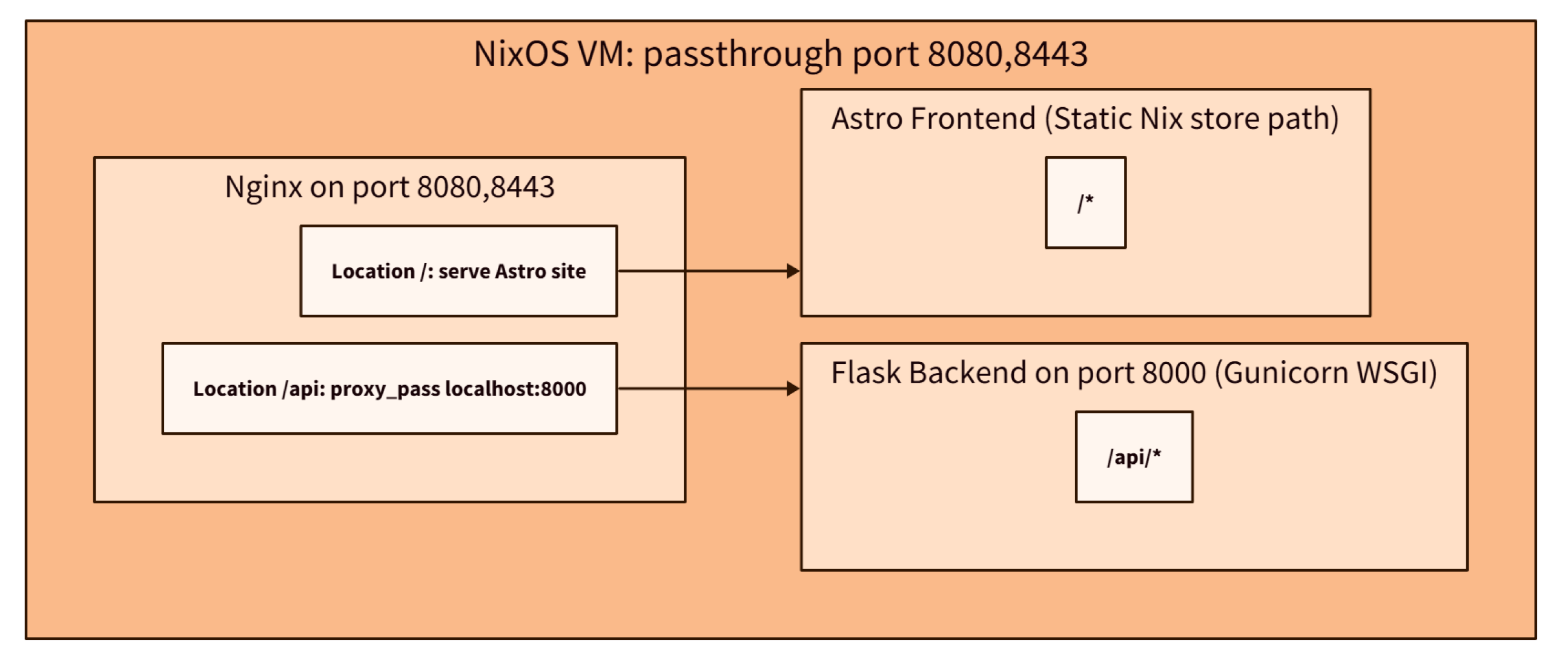

The backend is implemented in Flask, and the frontend is built in AstroJS. Communication occurs through routes prefixed with

/api. Both codebases are integrated using Nix and deployed through a NixOS virtual machine (see

Figure 3), as described in

Section 3.6.4.

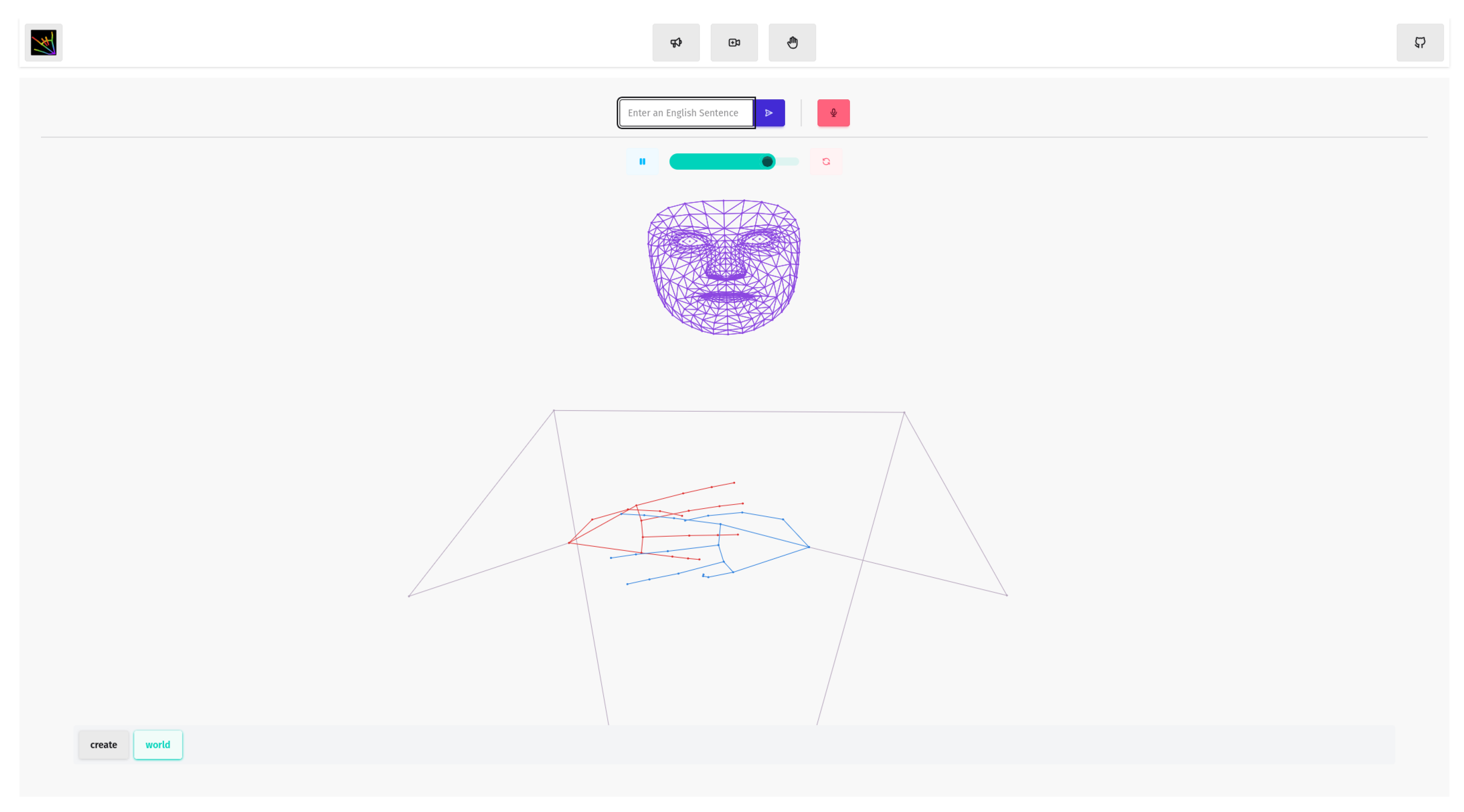

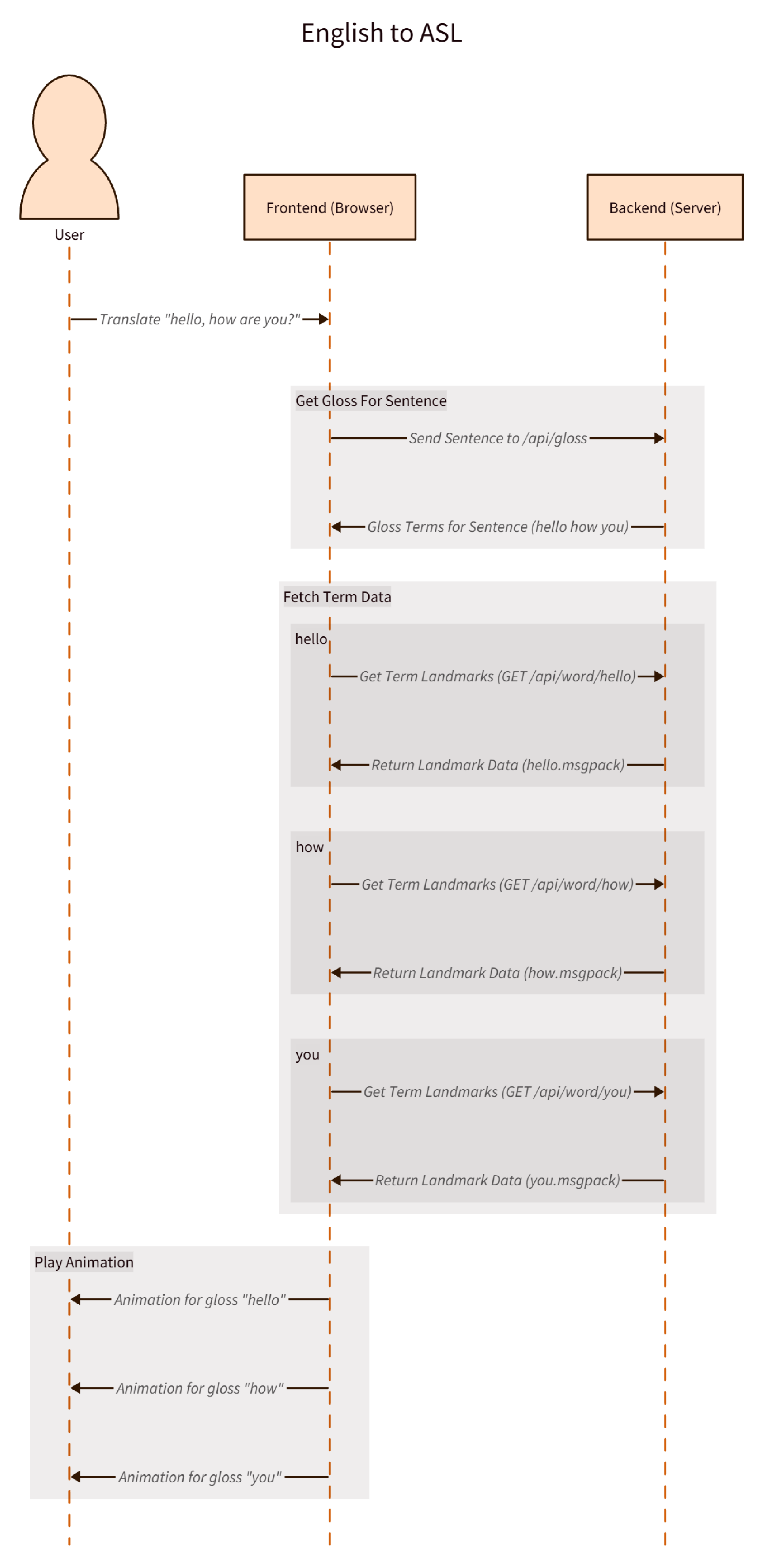

3.6.1. English to ASL

The “English to ASL” page (

Figure 4) enables users to enter or speak English statements. The interface translates the input into ASL glosses and plays back the corresponding ASL animations. The

SpeechRecognition API can optionally be used to capture spoken English input.

The translation process consists of:

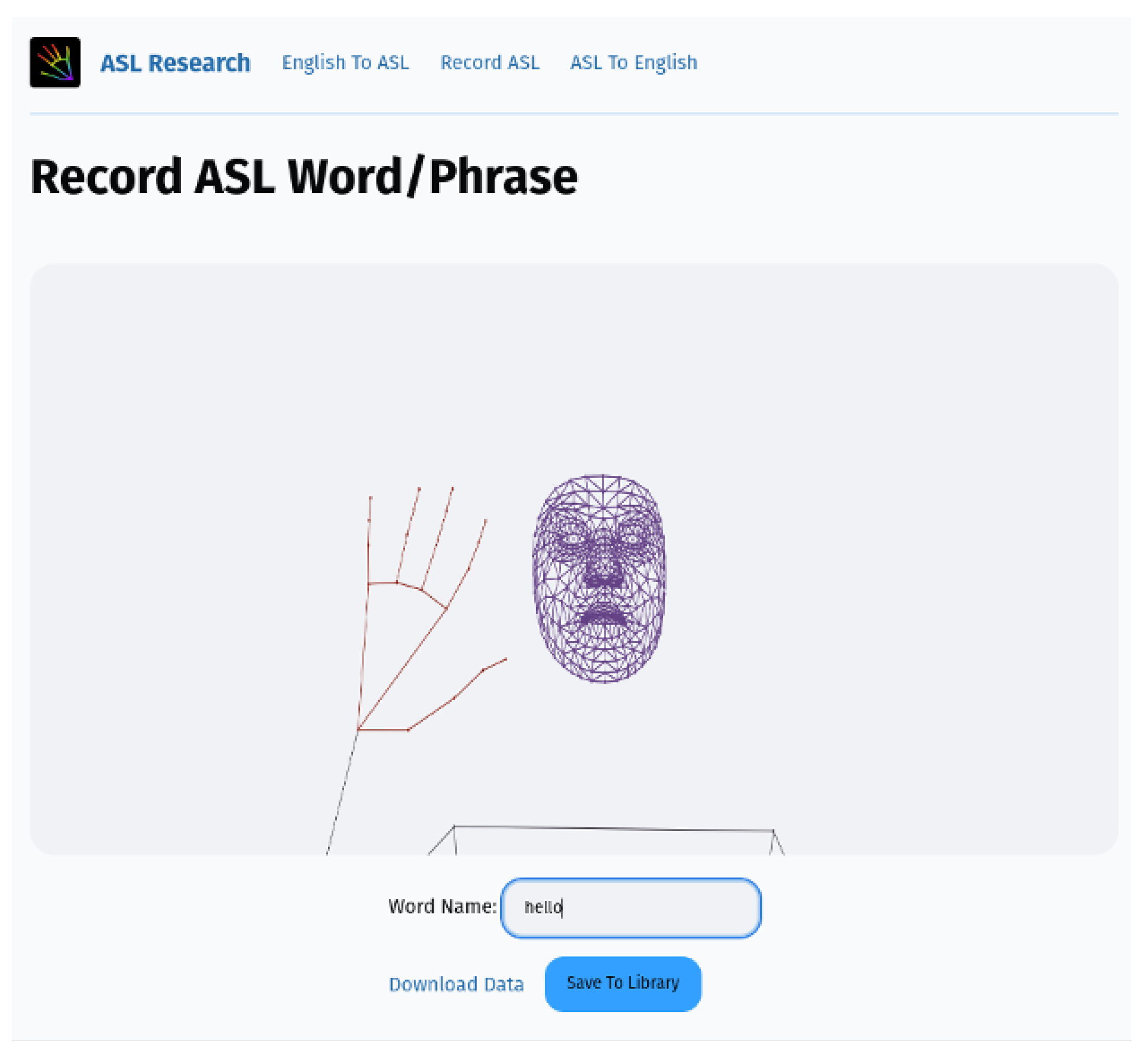

3.6.2. Recording ASL

Animations used by the “English to ASL” page must first be recorded through the “Record ASL” page

Section 3.6.1. As shown in

Figure 5, users record themselves signing a gloss, after which the system extracts landmarks and generates a 3D animation. If satisfied, the user may save the animation to the glossary library.

This page operates using the following steps:

Capture video via navigator.getUserMedia.

Send the recording to /api/mark.

The backend applies MediaPipe Holistic to extract landmarks.

Landmark data is returned as 3D coordinates for each frame.

The frontend replays the animation for user verification.

If approved, the animation is saved to /api/word/<name> with the supplied gloss name.

For bulk creation, we automated this workflow using the WLASL dataset. Our script extracts the gloss name from each video filename, processes the video automatically, and stores the animation in the glossary library.

3.6.3. ASL to English

The “ASL to English” page allows users to record ASL and receive an English translation (see

Figure 6).

The frontend captures 30-frame video segments using getUserMedia.

Each segment is uploaded to /api/a2e.

The backend processes the segment with the model described in Section .

The backend returns an English sentence, which is displayed on the page.

3.6.4. Integration/Deployment

We use the Nix build system to integrate the backend and frontend, ensuring reproducible environments. Python backend dependencies are managed with the uv package manager.

Integration

The frontend is built using buildNpmPackage, while the backend uses uv2nix. Both are exposed in flake.nix.

Deployment

A NixOS module runs the backend as a systemd service via gunicorn, and a NixOS VM unifies frontend and backend behind Nginx. The VM is stateless and only modifies the glossary library when needed.

4. Results

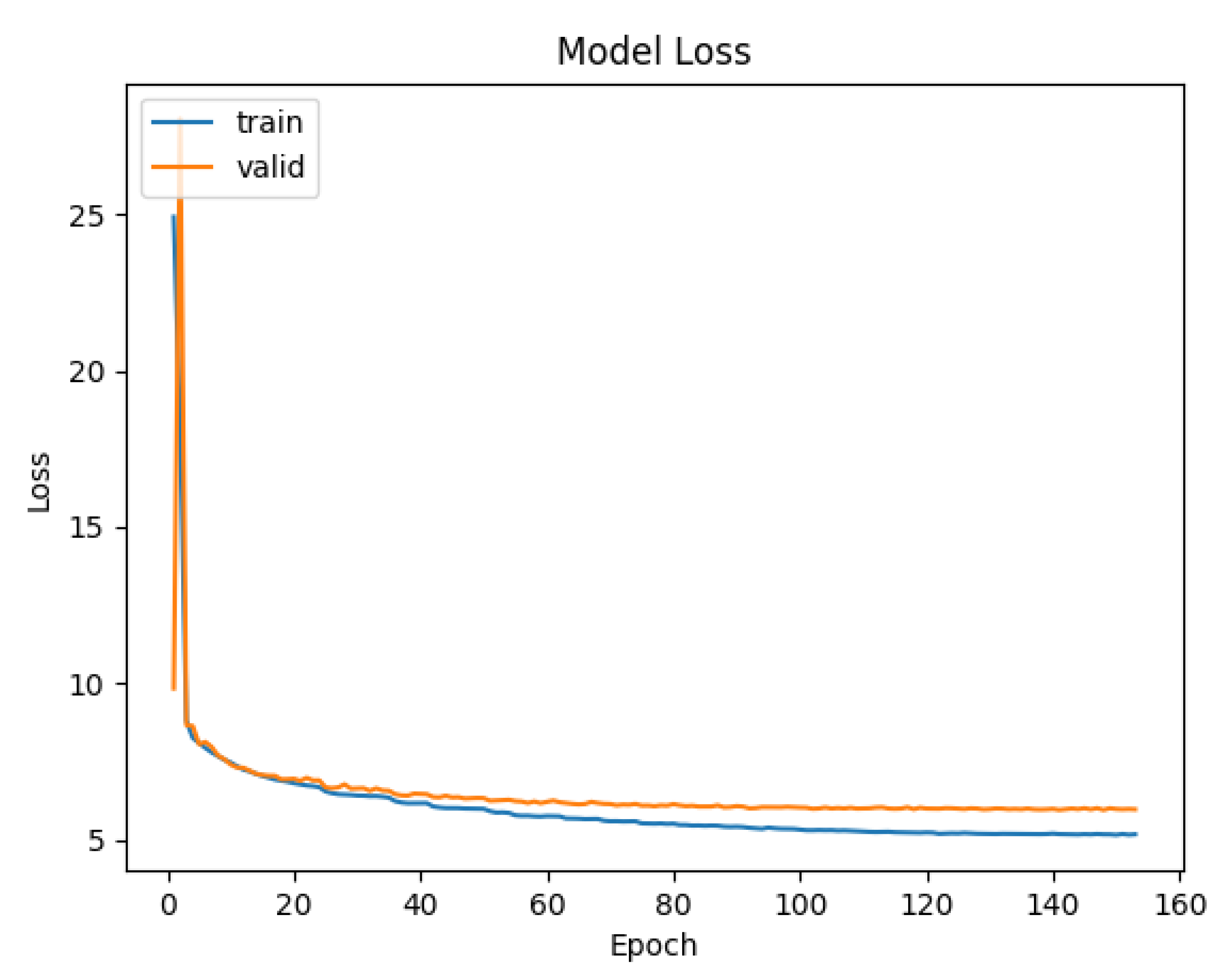

After training on the RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather 2014 T dataset for approximately 150 epochs, our Sign-to-Gloss and Sign-to-Sentence models achieved minimum Word Error Rates (WER) of 72% and 87%, respectively. These results fall significantly short of state-of-the-art performance reported in prior work, which commonly falls between 20-40% WER depending on the model and evaluation setup. Several factors may have contributed to the suboptimal performance, including suboptimal hyperparameters, insufficiently expressive visual embeddings from the CNN backbone, or excessive noise introduced by data augmentation.

Figure 7.

Diagram showing training and validation loss over time for the CNN-Transformer model

Figure 7.

Diagram showing training and validation loss over time for the CNN-Transformer model

For the Gloss-to-English Transformer trained on the ASLG-PC12 dataset, the model achieved 59.4% training accuracy and 57.4% validation accuracy after 30 epochs. While the training and validation accuracies are closely aligned (suggesting that overfitting is not the main issue), the results fall below our target range of 70-80% accuracy. This underperformance may stem from the relatively small dataset size, vocabulary sparsity, limited training time, or the inherent difficulty of generating fluent English from gloss input. Potential improvements include increasing the number of epochs, further tuning the hyperparameters, cleaning and expanding the dataset, or leveraging pretrained language models to improve fluency and contextual understanding.

5. Discussions

Our results for the jointly-trained CNN-Transformer translation system highlight both promising progress and important areas for future development. The model was only able to achieve a 72% Gloss WER and a 87% Sentence WER, which is significantly higher than the current state of the art. However, upon closer examination of the test data, it does manage to retrieve the right glosses/words from the test footage, meaning that we are on the right trajectory. There is also a large disparity between the Gloss and Sentence WER, having a 15% difference. This could be due to the Gloss WER being a more direct translation of the video, making it easier for the model to detect patterns from the dataset.

To mitigate overfitting, we incorporated 0.3 dropout layers into the CNN-Transformer architecture. By randomly deactivating a portion of the output units during training, dropout reduces reliance on specific neurons and promotes better generalization. While additional tuning of the dropout rate could further optimize performance, the current setup proved effective for learning meaningful representations from limited data. Still, larger and more diverse datasets will be necessary to fully evaluate the model’s robustness in real-world settings.

In contrast, the Gloss-to-English Transformer model, trained on the publicly available ASLG-PC12 dataset, achieved 59.4% training accuracy and 57.4% validation accuracy after 30 epochs. This lower performance reflects the inherent difficulty of natural language generation. Unlike gloss sequences, which are structurally simplified and often omit grammatical markers, generating fluent English sentences requires modeling complex syntax, semantics, and context [

20]. The structural differences between ASL gloss and English further compound this challenge.

The close alignment between training and validation accuracies suggests that the model is not overfitting; rather, it may be underfitting due to dataset limitations, vocabulary sparsity, or insufficient training time. Performance could likely improve with larger datasets, additional hyperparameter tuning, or by incorporating pretrained language models, as suggested by [

21], to enhance contextual understanding and fluency.

Overall, while the Sign-to-Gloss module performs strongly under controlled conditions, the Gloss-to-English component underscores the complexities of bridging the linguistic and structural gaps between ASL and English.

6. Conclusions

This study presents a real-time, bidirectional ASL and English translation system that integrates computer vision, deep learning, and web-based technologies to enhance accessibility for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (DHH) community. Our system introduces a holistic, multimodal pipeline that captures spatiotemporal landmarks from ASL video input, converts them into glosses using a CNN-Transformer model, and translates them into natural English sentences using a hybrid CNN and transformer-based architecture. In the reverse direction, it supports English-to-ASL translation by generating gloss terms and reconstructing ASL landmark animations for playback.

With a Gloss WER of 72% and a Sentence WER of 87%, our prototype demonstrates promising performance across both translation directions. The web interface enables real-time interaction through audio, text, or video, providing an accessible user experience. By unifying gesture recognition, gloss prediction, and language translation, our system advances beyond prior work that often addressed these components in isolation.

Overall, this research demonstrates the feasibility of an integrated, real-time ASL–English translation system that balances linguistic accuracy, user interaction, and technical scalability. Future work will focus on expanding datasets, improving model architectures, and enhancing translation quality to further support real-world deployment.

6.1. Future Work

While our system demonstrates strong potential in real-time, bidirectional ASL–English translation, several limitations create opportunities for future improvement. One key limitation is the size and diversity of the training data. The CNN-Transformer model was trained on a specialized German sign language dataset which may not capture the full variability of natural sign language use, including differences in signing styles, speeds, lighting conditions, and signer characteristics. Expanding training resources using larger publicly available datasets, such as RWTH-Fingerspelling or CSL-Daily, could substantially improve model generalization.

Another challenge is the limited accuracy of the Gloss-to-English transformer, which achieved a validation accuracy of 57.4%. This reflects the difficulty of modeling semantic and grammatical nuances when converting gloss input into natural English. Future improvements could include incorporating larger or more diverse datasets, integrating pretrained language models (e.g., BERT, T5), or adopting hybrid architectures. To further mitigate underfitting, data augmentation strategies could be used to expand the effective size and variability of the existing datasets.

The system also supports a limited vocabulary because it relies on a manually recorded gloss-term library. This constrains translation flexibility and increases manual effort when expanding the lexicon. Future work could automate the creation of gloss-term landmark data using generative models such as diffusion networks or 3D avatar synthesis, enabling support for unseen or low-resource vocabulary.

Additionally, while the system uses MediaPipe Holistic to detect landmarks for the hands, face, and body, it does not fully leverage facial expressions or other non-manual markers, features that are essential to ASL grammar. Incorporating facial expression analysis could significantly improve grammatical accuracy and the naturalness of translations.

The translation model also seems to have difficulty extracting necessary patterns and information from the videos themselves. This problem could be due to the visual backbone not effectively representing the features of the footage. Our current model utilizes a pretrained EfficientNet B0 model because of the combination of its small number of parameters and its high accuracy. However, in the future, we are hoping to utilize a pretrained inflated 3D convolutional network (I3D) as it utilizes RGB and optical flow information in order to encode better temporal and visual cues in our feature vectors. [

22].

From a usability standpoint, the system could be extended to mobile, wearable, or AR platforms for deployment in real-world environments. Integration with smart glasses or mobile devices could provide hands-free accessibility for DHH users. Introducing a user feedback loop, allowing users to correct or rate translations, could further refine accuracy over time and personalize the translation experience.

In summary, while the current system lays a strong foundation for real-time, bidirectional ASL–English translation, future work will focus on scaling the data, enhancing model architectures, capturing richer linguistic features, and improving usability through continuous learning and broader deployment platforms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.A. and M.A; methodology: S.A. and M.A.; software: B.C.; validation: S.A., M.A., A.P., J.D., L.B.N. and M.A.A.D.; formal analysis: S.A., M.A., B.C., A.P. and M.A.A.D.; investigation: S.A., M.A., and B.C., and A. P.; resources: S.A. and M.A., L.B.N.; data curation: S.A., B.C., and A.P.; writing—original draft preparation: S.A., M.A. J.D., and A.P.; writing—review and editing: S.A., M.A., L.B.N, and M.A.A.D.; visualization: B.C.; supervision: M.A. and S.A.; project administration: M.A. and S.A.; funding acquisition: M.A., S.A. and M.A.A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Avina, V.D.; Amiruzzaman, M.; Amiruzzaman, S.; Ngo, L.B.; Dewan, M.A.A. An AI-Based Framework for Translating American Sign Language to English and Vice Versa. Information 2023, 14, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J.; Brennan, K.; Amiruzzaman, S.; Amiruzzaman, M. English to American Sign Language: An AI-Based Approach. Journal of Computing Sciences in Colleges 2024, 40, 164–175. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.; Matsuoka, A.; Hasan, M.A.M.; Srizon, A.Y. American sign language alphabet recognition by extracting feature from hand pose estimation. Sensors 2021, 21, 5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellara, H.; Barioul, R.; Sahnoun, S.; Fakhfakh, A.; Kanoun, O. Improving the accuracy of hand sign recognition by chaotic swarm algorithm-based feature selection applied to fused surface electromyography and force myography signals. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2025, 154, 110878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamani, T.; Subiksha, K.; Swathi, D.; Vennila, V.; et al. IYAL: Real-Time Voice to Text Communication for the Deaf. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Multi-Agent Systems for Collaborative Intelligence (ICMSCI), 2025; IEEE; pp. 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, B.; Chaudhary, A.; Bano, S.; Yashmita; Reddy, S.; Anand, R. Fostering inclusivity through effective communication: Real-time sign language to speech conversion system for the deaf and hard-of-hearing community. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83, 45859–45880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camgoz, N.C.; Koller, O.; Hadfield, S.; Bowden, R. Sign language transformers: Joint end-to-end sign language recognition and translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020; pp. 10023–10033. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.; Miyazaki, T.; Khan, N.; Nakadai, K. Improvement in sign language translation using text CTC alignment. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 2025; pp. 3255–3266. [Google Scholar]

- Jintanachaiwat, W.; Jongsathitphaibul, K.; Pimsan, N.; Sojiphan, M.; Tayakee, A.; Junthep, T.; Siriborvornratanakul, T. Using LSTM to translate Thai sign language to text in real time. Discover Artificial Intelligence 2024, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Li, C. SLR-YOLO: An improved YOLOv8 network for real-time sign language recognition. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems 2024, 46, 1663–1680. [Google Scholar]

- Praun-Petrovic, V.; Koundinya, A.; Prahallad, L. Comparison of Autoencoders for tokenization of ASL datasets. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.06942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achraf, O.; Zouhour, T. English-ASL Gloss Parallel Corpus 2012: ASLG-PC12. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference On Information and Communication Technology and Accessibility ICTA’13, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kahlon, N.K.; Singh, W. Machine translation from text to sign language: a systematic review. Universal Access in the Information Society 2023, 22, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camgöz, N.C.; Hadfield, S.; Koller, O.; Ney, H.; Bowden, R. Neural Sign Language Translation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conf. on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, A.; Palaskar, S.; Ventura, L.; Ghadiyaram, D.; DeHaan, K.; Metze, F.; Torres, J.; Giro-i Nieto, X. How2sign: a large-scale multimodal dataset for continuous american sign language. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021; pp. 2735–2744. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wei, F.; Sun, X.; Wu, Z.; Lin, S. A simple multi-modality transfer learning baseline for sign language translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022; pp. 5120–5130. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, R.; Rushe, E.; De Coster, M.; Bonnaerens, M.; Satoh, S.; Sugimoto, A.; Ventresque, A. From scarcity to understanding: Transfer learning for the extremely low resource irish sign language. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023; pp. 2008–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Rodriguez, C.; Yu, X.; Li, H. Word-level Deep Sign Language Recognition from Video: A New Large-scale Dataset and Methods Comparison. In Proceedings of the The IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2020; pp. 1459–1469. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Qiu, X. A survey of transformers. AI open 2022, 3, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, S.K. American sign language syntax; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2021; Vol. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; Hovy, E.; Sun, Y. Pre-trained language models and their applications. Engineering 2023, 25, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrés, L.; Gállego, G.I.; Duarte, A.; Torres, J.; Giró-i Nieto, X. Sign language translation from instructional videos. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023; pp. 5625–5635. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).