Submitted:

04 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

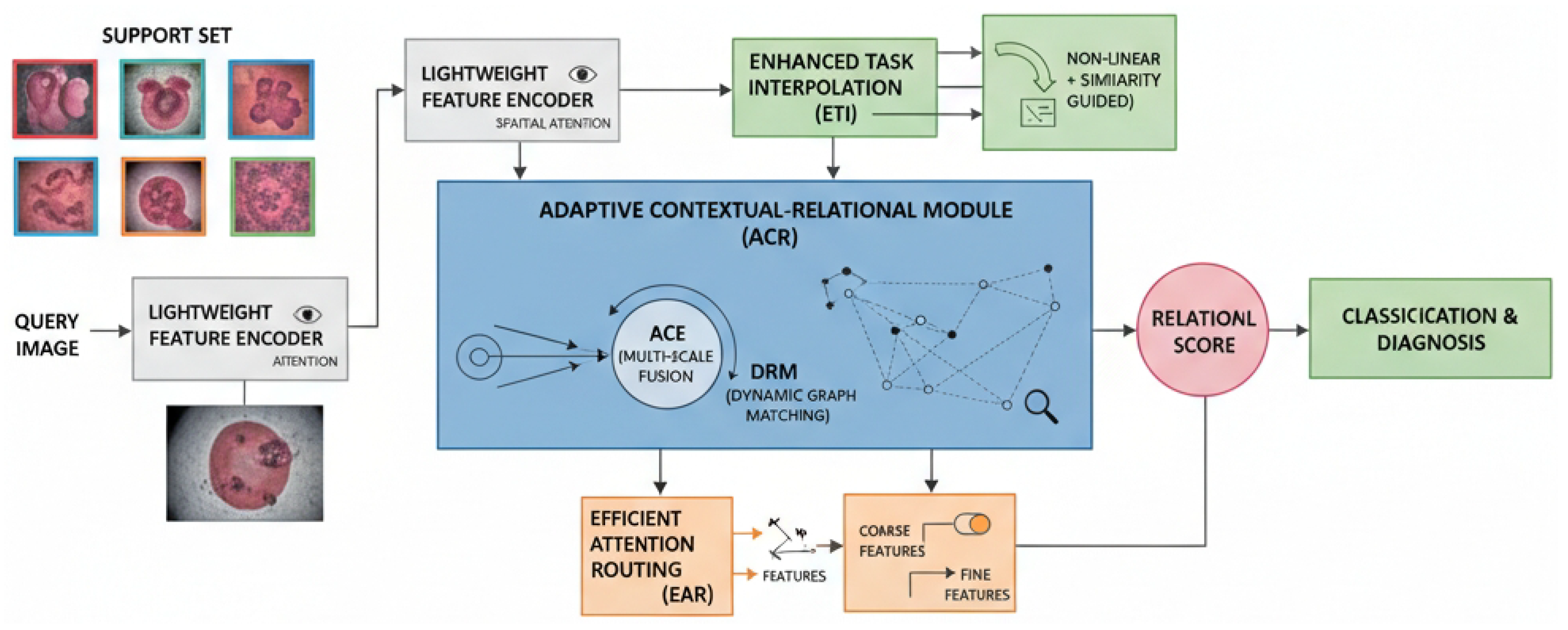

- We propose a novel Adaptive Contextual-Relational Network (ACRN) that integrates an Adaptive Contextual-Relational Module (ACR) for enhanced contextual awareness and dynamic relational matching, specifically designed for fine-grained GI disease classification under Few-Shot Learning settings.

- We introduce an Enhanced Task Interpolation strategy that utilizes feature similarity-based non-linear interpolation, enabling the generation of more realistic virtual tasks to improve model generalization and discrimination of subtle differences.

- We achieve state-of-the-art performance on challenging GI endoscopic datasets (e.g., Kvasir-v2), demonstrating the superior accuracy and robustness of ACRN in distinguishing fine-grained pathologies, even with limited training data.

2. Related Work

2.1. Few-Shot Learning in Medical Imaging

2.2. Relational and Contextual Modeling for Fine-Grained Analysis

3. Method

3.1. Lightweight Feature Encoder

3.2. Adaptive Contextual-Relational Module (ACR)

3.2.1. Adaptive Contextual Encoding

3.2.2. Dynamic Relational Matching

3.3. Enhanced Task Interpolation

3.4. Efficient Attention Routing

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

- Pre-training Data: To leverage broad visual knowledge, our model is pre-trained on diverse datasets including ISIC 2018 (skin lesions), Cholec80 (surgical tool video frames), and Mini-ImageNet (general object categories). This multi-domain pre-training strategy helps in learning generalized features transferable to endoscopic images.

- Fine-tuning Data: The Hyper-Kvasir dataset, comprising 10,662 endoscopic images across 23 distinct GI disease categories, is utilized for fine-tuning our model. This allows the model to adapt its learned representations specifically to the domain of gastrointestinal imagery.

- Evaluation Data: The primary evaluation of ACRN’s classification performance is conducted on the Kvasir-v2 dataset. This dataset consists of 8,000 images distributed across 8 common GI disease categories, with approximately 1,000 images per class, providing a robust benchmark for fine-grained classification.

4.2. Baseline Methods

4.3. Quantitative Results

4.4. Ablation Study

- ACRN w/o SAEM: Removing the Spatial Attention Enhancement Module from the Lightweight Feature Encoder leads to a noticeable drop in performance. This indicates that adaptively focusing on salient spatial regions is crucial for extracting discriminative features, especially for subtle GI lesions.

- ACRN w/o ACE: Replacing the Adaptive Contextual Encoding with a simpler single-scale feature aggregation strategy results in a performance decrease. This validates the importance of adaptively fusing multi-scale contextual information for robust understanding of lesions under varied conditions.

- ACRN w/o DRM: When the Dynamic Relational Matching mechanism is substituted with a static, simpler cross-correlation approach, performance declines. This highlights the benefit of dynamically building and analyzing sparse graph structures to focus on disease-specific critical regions, thereby improving discriminability.

- ACRN w/o ETI: Using a conventional linear interpolation for task augmentation instead of our Enhanced Task Interpolation strategy also reduces accuracy. This confirms that generating more realistic, feature similarity-based non-linear virtual tasks is vital for improving generalization and distinguishing subtle differences between classes.

- ACRN w/o EAR: Disabling the Efficient Attention Routing mechanism, which dynamically selects between coarse and fine-grained features, leads to a minor performance dip. This suggests that while EAR provides efficiency gains, it also contributes to better focus and information flow, albeit less critically than the core ACR and ETI modules.

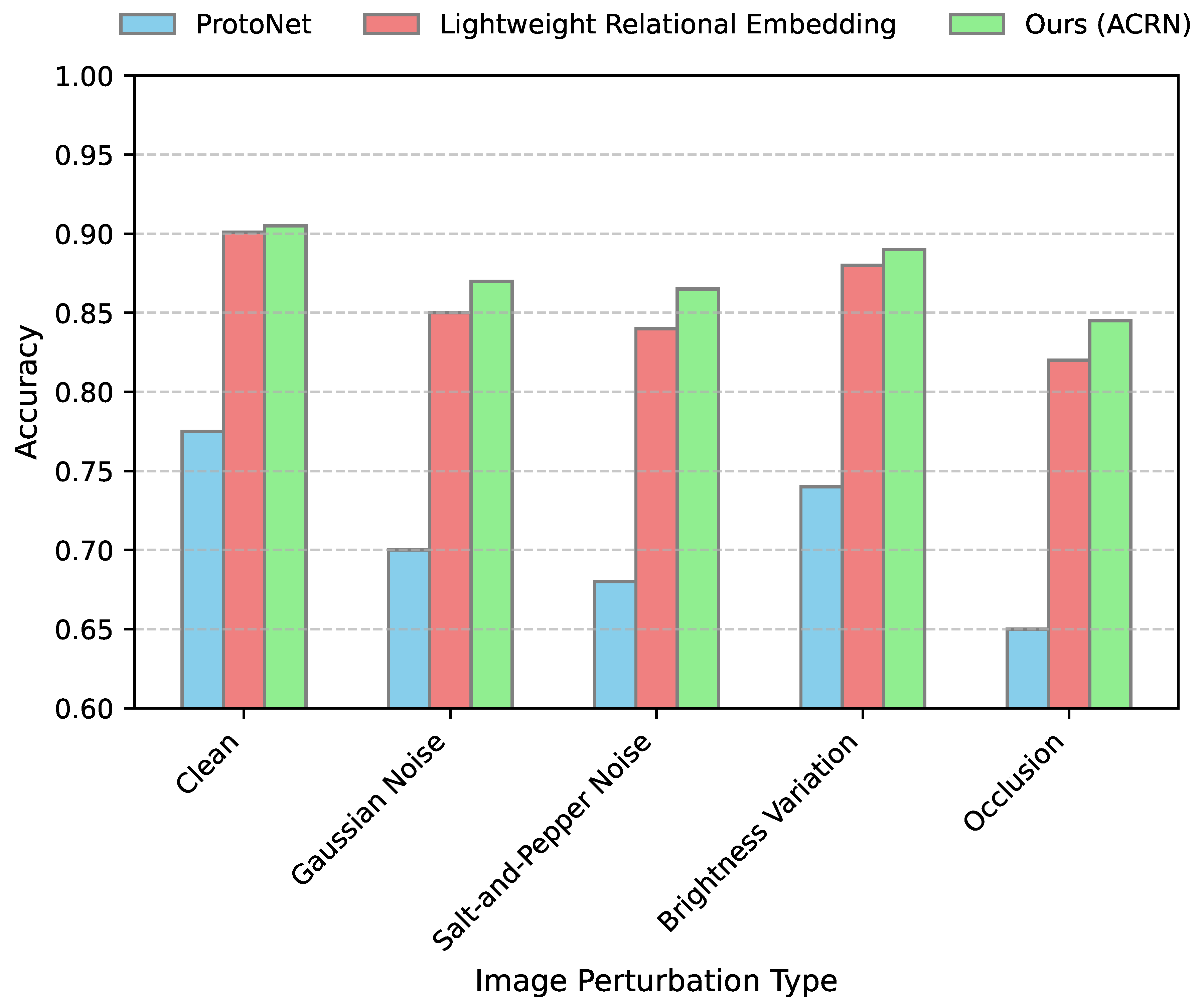

4.5. Robustness to Image Perturbations

4.6. Computational Efficiency Analysis

4.7. Human Evaluation

5. Conclusion

References

- Vidgen, B.; Thrush, T.; Waseem, Z.; Kiela, D. Learning from the Worst: Dynamically Generated Datasets to Improve Online Hate Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 1667–1682. [CrossRef]

- Hui, J.; Tang, K.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, X.; Han, Q. The causal impact of gut microbiota and metabolites on myopia and pathological myopia: a mediation Mendelian randomization study. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 12928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cui, X. Multi-omics Mendelian Randomization Reveals Immunometabolic Signatures of the Gut Microbiota in Optic Neuritis and the Potential Therapeutic Role of Vitamin B6. Molecular Neurobiology 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Liang, T.; Ji, X.; Shao, Y.; Zhao, P.; Li, X. LINC00488 induces tumorigenicity in retinoblastoma by regulating microRNA-30a-5p/EPHB2 Axis. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation 2023, 31, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, K.M.; Park, D.; Kang, J.; Lee, S.W.; Park, W. GPT3Mix: Leveraging Large-scale Language Models for Text Augmentation. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 2225–2239. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2021.findings-emnlp.192. [CrossRef]

- Herzig, J.; Berant, J. Span-based Semantic Parsing for Compositional Generalization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 908–921. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, J.; Cheng, Y. Weak to strong generalization for large language models with multi-capabilities. In Proceedings of the The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, R.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, S.; Yu, K. LGESQL: Line Graph Enhanced Text-to-SQL Model with Mixed Local and Non-Local Relations. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 2541–2555. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Geng, X.; Shen, T.; Tao, C.; Long, G.; Lou, J.G.; Shen, J. Thread of thought unraveling chaotic contexts. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.08734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhang, S.; Ji, T.; Tian, Z. Enhancing single-temporal semantic and dual-temporal change perception for remote sensing change detection. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, P.; Zuo, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Y.; Peng, W. Knowledge-Enriched Event Causality Identification via Latent Structure Induction Networks. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 4862–4872. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Shen, J. Visual In-Context Learning for Large Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand and virtual meeting, August 11-16, 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 15890–15902.

- Xu, S.; Tian, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Z. Benchmarking Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models for Fake News Detection Using News Headlines. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, W.; Flynn, D.; Ansari, S.; Wei, C. Evaluating scenario-based decision-making for interactive autonomous driving using rational criteria: A survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.01886. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Agarwal, D.; Sun, J. MedCLIP: Contrastive Learning from Unpaired Medical Images and Text. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022; pp. 3876–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Pan, S. Incorporating medical knowledge in BERT for clinical relation extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021; pp. 5357–5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chu, H.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Learning from Language Description: Low-shot Named Entity Recognition via Decomposed Framework. Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics 2021, 1618–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Dong, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, T.; Wei, F. CLIP Models are Few-Shot Learners: Empirical Studies on VQA and Visual Entailment. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 6088–6100. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.V.; Mihaylov, T.; Artetxe, M.; Wang, T.; Chen, S.; Simig, D.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Bhosale, S.; Du, J.; et al. Few-shot Learning with Multilingual Generative Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 9019–9052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Ge, S.; Wu, X. Competence-based Multimodal Curriculum Learning for Medical Report Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 3001–3012. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Jin, Q.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, A. Benchmarking Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Medicine. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 6233–6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jin, Q. MMGCN: Multimodal Fusion via Deep Graph Convolution Network for Emotion Recognition in Conversation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 5666–5675. [CrossRef]

- Potts, C.; Wu, Z.; Geiger, A.; Kiela, D. DynaSent: A Dynamic Benchmark for Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 2388–2404. [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Wei, L.; Huai, X. DialogueCRN: Contextual Reasoning Networks for Emotion Recognition in Conversations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 7042–7052. [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Chen, Y.; Han, X.; Xu, G.; Wang, X.; Xie, P.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Kim, H.G. Prompt-learning for Fine-grained Entity Typing. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2022, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 6888–6901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Fisch, A.; Chen, D. Making Pre-trained Language Models Better Few-shot Learners. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 3816–3830. [CrossRef]

- Fetahu, B.; Chen, Z.; Kar, S.; Rokhlenko, O.; Malmasi, S. MultiCoNER v2: a Large Multilingual dataset for Fine-grained and Noisy Named Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 2027–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Tian, Z.; He, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Yuan, F.; Peng, Y. Enhanced mean field game for interactive decision-making with varied stylish multi-vehicles. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.00981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. Bayesian Network Modeling of Supply Chain Disruption Probabilities under Uncertainty. Artificial Intelligence and Digital Technology 2025, 2, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; et al. Real-Time Adaptive Dispatch Algorithm for Dynamic Vehicle Routing with Time-Varying Demand. Academic Journal of Computing & Information Science 2025, 8, 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S. LSTM-Based Deep Learning Models for Long-Term Inventory Forecasting in Retail Operations. Journal of Computer Technology and Applied Mathematics 2025, 2, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, W.; Wu, W.; Wang, S. Reconstruction of complex network from time series data based on graph attention network and Gumbel Softmax. International Journal of Modern Physics C 2023, 34, 2350057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Horowitz, R.; Wang, Y.; Han, Y. Hybrid Perception and Equivariant Diffusion for Robust Multi-Node Rebar Tying. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 21st International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), 2025; IEEE; pp. 3164–3171. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wen, J.; Han, Y. EP-SAM: An Edge-Detection Prompt SAM Based Efficient Framework for Ultra-Low Light Video Segmentation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025-2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2025; IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Z.; Kang, D.; Yuan, B.; Du, D.; Li, B. Improving the Sustainability of Solid-State Drives by Prolonging Lifetime. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI). IEEE, 2024; pp. 502–507. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Z.; Gong, H.; Du, D.H. PM-Dedup: Secure Deduplication with Partial Migration from Cloud to Edge Servers. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.02350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Z.; Diehl, J.; Chen, Y.S.; Du, D.H. Emerald Tiers: Focusing on SSD+ MAID Through a Green Lens. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 17th ACM Workshop on Hot Topics in Storage and File Systems, 2025; pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Luo, X.; Huang, C.; Liu, C.; Wen, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y. HACDR-Net: Heterogeneous-aware convolutional network for diabetic retinopathy multi-lesion segmentation. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2024, Vol. 38, 6342–6350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Huang, C.; Liu, C.; Jin, X.; Zhang, J. A lesion-fusion neural network for multi-view diabetic retinopathy grading. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Xu, Q.; Wu, H.; Liu, C.; Lai, Z.; Shen, L. Like an Ophthalmologist: Dynamic Selection Driven Multi-View Learning for Diabetic Retinopathy Grading. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2025, Vol. 39, 19224–19232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | ACC | Precision | Recall | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAML | 0.792 | 0.610 | 0.633 | 0.621 |

| ProtoNet | 0.775 | 0.662 | 0.694 | 0.678 |

| Transformer | 0.870 | 0.738 | 0.812 | 0.773 |

| ResNet50 | 0.812 | 0.701 | 0.794 | 0.745 |

| Lightweight Relational Embed. | 0.901 | 0.845 | 0.942 | 0.891 |

| Ours (ACRN) | 0.905 | 0.850 | 0.945 | 0.898 |

| Method Variant | ACC | Precision | Recall | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| w/o SAEM | 0.887 | 0.825 | 0.928 | 0.874 |

| w/o ACE (single-scale) | 0.891 | 0.830 | 0.932 | 0.878 |

| w/o DRM (static correlation) | 0.895 | 0.838 | 0.935 | 0.884 |

| w/o ETI (linear interpolation) | 0.900 | 0.842 | 0.940 | 0.890 |

| w/o EAR | 0.902 | 0.847 | 0.943 | 0.895 |

| ACRN (Full Model) | 0.905 | 0.850 | 0.945 | 0.898 |

| Method | Parameters (M) | FLOPs (G) | Inference Time / Episode (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProtoNet | 2.5 | 0.5 | 0.08 |

| Lightweight Relational Embedding | 3.0 | 0.6 | 0.12 |

| Transformer | 20.1 | 4.0 | 0.50 |

| Ours (ACRN) | 3.2 | 0.7 | 0.15 |

| Method | ACC | Precision | Recall | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Human Expert | 0.885 | 0.830 | 0.900 | 0.864 |

| Ours (ACRN) | 0.892 | 0.845 | 0.905 | 0.874 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).