Introduction

Over the last ten years clinicians have begun to look beyond serotonin when treating severe mood and anxiety disorders. Work with intravenous ketamine first showed that a brief block at the NMDA receptor, quickly followed by stronger AMPA signalling, can spark new synapse growth and soften rigid neural loops within hours (1, 2). Turning that laboratory insight into something patients can swallow at home has proved difficult, but a budget-friendly oral mix containing dextromethorphan (DXM), a CYP2D6 inhibitor, and the AMPA enhancer piracetam—now called the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen (CGR)—is beginning to fill that gap (1, 3, 4).

Early series have already described striking recoveries in resistant OCD, depression and trauma-related illness (3, 4, 5). What those reports rarely show is the day-to-day evolution: when relief first appears, which adverse effects surface, how fast they fade, and how small dose tweaks steer the process. Such detail matters most in older patients who take many medicines and in those with health-focused OCD, where any new bodily sensation may be read as a life-threatening sign.

We describe a 68-year-old man whose five-year history of presumed somatic depression and health anxiety was revised to severe OCD with hypochondriacal themes. Two points make the case instructive. First, the patient reached near-complete remission in only four nights, one of the fastest responses yet recorded in an elderly, heavily pre-treated individual. Second, the patient supplied meticulous daily updates through encrypted messaging, giving an unusually granular view of symptom change, side-effect ebb and flow, and the influence of daily micro-adjustments during the crucial first treatment week.

Methods

This work is a single-case observational study carried out in routine practice at Cheung Ngo Medical, a private outpatient psychiatry clinic located in H Zentre, Kowloon, Hong Kong. All clinical decisions—including initiation of the glutamatergic regimen, subsequent dose changes and ancillary medication adjustments—were made by the attending psychiatrist (N.C.) during the period 1 to 5 December 2025. No element of the care pathway was altered for research purposes.

The patient gave written informed consent that his anonymised clinical notes, dispensing records and WhatsApp correspondence could be reproduced for scientific publication.

Primary outcome information came from three sources. First, the patient sent daily, unsolicited WhatsApp messages—text and the occasional voice note—summarising sleep, energy, intrusive thoughts and side-effects; these updates were usually transmitted each afternoon or evening. Second, standardised rating scales (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7) were completed in clinic at baseline. Third, narrative progress notes and pharmacy logs documented by the treating psychiatrist provided a contemporaneous record of mental-state examination findings and exact medication dosing. A formal OCD instrument such as the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale was not administered because the consultation followed standard private-practice workflows; change in obsessive symptoms was therefore inferred from serial PHQ-9/GAD-7 scores, detailed interviewing and the patient’s own reports.

All WhatsApp messages, audio clips and prescription data from 1–5 December 2025 were exported from the clinic’s encrypted electronic medical-record system and arranged in chronological order. Dose modifications are presented exactly as relayed to the patient through the same secure channel.

Case Presentation

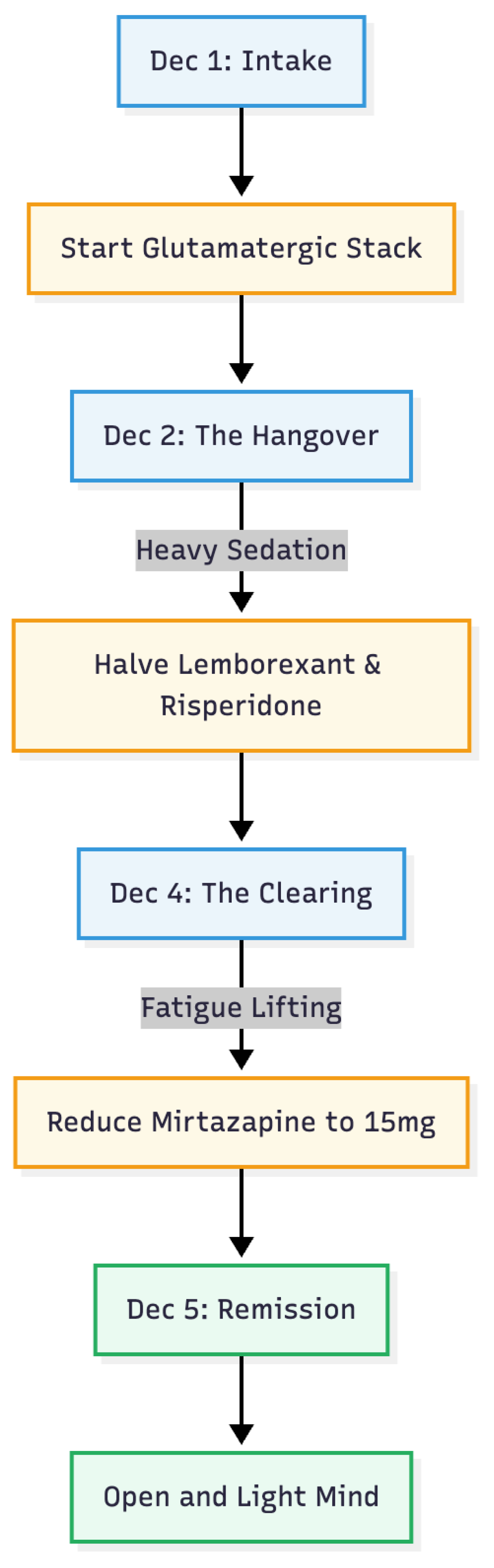

A 68-year-old retired man was first seen in our private psychiatric clinic on 1 December 2025 after five years of persistent mood and anxiety symptoms that had withstood extensive treatment in both public and private services. He was arriving on a combination of mirtazapine 45 mg nightly, bupropion XL 150 mg each morning and brexpiprazole 1 mg divided through the day, yet remained severely impaired. He described overwhelming tiredness, a daily spell of early-morning restlessness that eased only by early afternoon, constant inability to relax, and an all-consuming fear that an undiagnosed medical catastrophe was imminent (

Figure 1).

Closer questioning revealed a long history of intrusive thoughts about serious illness. He compulsively checked his pulse, palpated his neck and abdomen, monitored every bodily sensation and sought repeated medical reassurance, prompting numerous emergency-department visits and negative specialist work-ups. Any trivial symptom— a muscle twitch, a fleeting chest pressure, a minor change in bowel habit—was immediately interpreted as cancer, heart disease or another fatal disorder. Although earlier teams had labelled the picture “somatic depression” with comorbid health anxiety, formal obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) had never been considered. On re-evaluation we diagnosed severe OCD with prominent hypochondriacal themes and secondary depression.

At intake his Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) score was 13, denoting moderately severe depression, and his Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) score was 8. Sleep was fragmented despite high-dose mirtazapine. Because serotonin-based approaches had repeatedly failed, we introduced a low-dose oral glutamatergic protocol taken entirely at night to minimise daytime activation. On 1 December the bedtime regimen was changed to mirtazapine 30 mg, brexpiprazole 0.5 mg, lemborexant 2.5 mg, alprazolam 0.25mg, risperidone 0.5 mg, dextromethorphan 30 mg and piracetam 600 mg; morning bupropion XL 150 mg was continued unchanged, providing CYP2D6 inhibition to prolong dextromethorphan exposure. Brexpiprazole was stopped for being a suspected culprit for his restlessness.

By the second night the patient enjoyed his first unbroken sleep in months, yet awoke with profound heaviness and slowed movements, prompting real-time dose adjustments by secure messaging: lemborexant was halved to 1.25 mg and risperidone to 0.25 mg. Over the next two nights sleep remained solid, morning fatigue steadily lightened and restlessness did not return. On 4 December mirtazapine was further reduced to 15 mg. The fourth night on the glutamatergic pair (5 December) marked a dramatic turning point: he fell asleep promptly, rose refreshed at 07:15, reported no restlessness, and noted that only mild residual tiredness lifted completely by lunchtime. More strikingly, the intrusive health fears that had dominated his life receded to the background and were easily dismissed, leaving what he called an “open and light” mind.

As of 5 December 2025 the maintenance schedule consisted of mirtazapine 15 mg, dextromethorphan 30 mg and piracetam 600 mg nightly, plus risperidone 0.25 mg and—only if needed—lemborexant 1.25 mg and alprazolam 0.25mg for sleep; bupropion XL 150 mg was continued each morning. Morning restlessness had disappeared, hypochondriacal obsessions and compulsive checking were virtually absent, mood and energy were consistently brighter in the afternoon and evening, and sleep was restorative without hypnotic reliance. In a patient whose obsessive-compulsive and depressive symptoms had resisted years of sequential pharmacotherapies, the addition of low-dose dextromethorphan and piracetam produced a near-complete remission within four nights, sustained at early follow-up with only minor titration of co-medications.

Conclusion

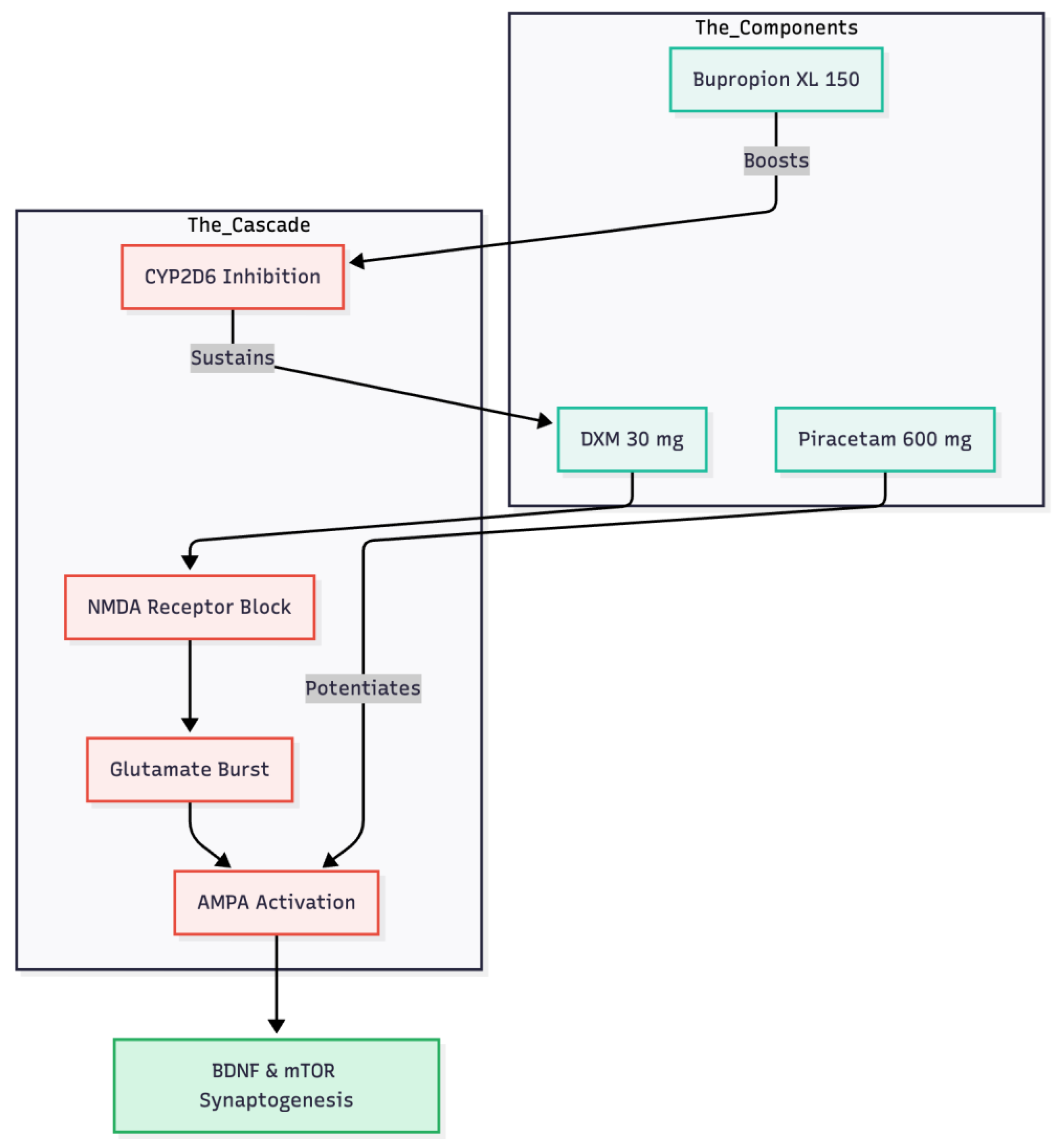

This man’s swift and almost complete remission after just four nights on dextromethorphan 30 mg plus piracetam 600 mg reinforces the view that modulating glutamate, rather than serotonin, can unlock rapid change in obsessive-compulsive disorder (1) (

Figure 2). The time course matches the mechanistic sequence described for ketamine: an initial NMDA-receptor block provokes a glutamate burst; that surge must then pass through AMPA channels to release BDNF and trigger mTOR-driven synaptogenesis (6, 7). Commercial dextromethorphan–bupropion (Auvelity®) supplies the first half of that cascade, but without direct AMPA potentiation responses are slower and less durable (8, 1). Adding piracetam, a benign AMPA positive allosteric modulator, appears to finish the job in a low-cost oral format (1).

Bupropion XL 150 mg, already part of the patient’s regimen, acted as a CYP2D6 inhibitor and prolonged dextromethorphan exposure, a pharmacokinetic strategy comparable to pairing the cough suppressant with fluoxetine or paroxetine (9, 1). The overnight disappearance of morning restlessness and health-related intrusive thoughts, coupled with fully restorative sleep, mirrors outcomes in other small OCD series using the same combination (3, 4, 5). Early daytime lethargy and bradykinesia most likely reflected residual sedation from mirtazapine, lemborexant and risperidone; stepwise dose reductions of those agents lifted the fatigue without eroding the glutamatergic benefit, underscoring the need to adjust co-medications aggressively in older, poly-treated patients.

The speed of improvement—clinically meaningful change by night four, remission by day five—outpaces many intravenous ketamine reports in OCD and rivals the classic single-dose ketamine response in major depression (2, 1). Achieving such results with generic, once-nightly tablets at a fraction of the cost of patented rapid-acting agents suggests that a well-designed oral NMDA + AMPA protocol can democratise ketamine-class efficacy (1, 4).

Taken together, this case adds to mounting evidence that low-dose dextromethorphan, pharmacologically shielded by a CYP2D6 inhibitor and paired with piracetam’s AMPA enhancement, can deliver robust, durable anti-obsessional and mood-lifting effects in individuals who have failed multiple serotonergic and antipsychotic trials. Larger, controlled studies are warranted, but for now the experience offers a pragmatic option for clinicians facing refractory OCD, especially when access to infusion centres or esketamine clinics is limited.

Funding Declaration

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Declaration

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest and Source of Funding Statement

None declared.

References

- Cheung, N. DXM, CYP2D6-inhibiting antidepressants, piracetam, and glutamine: Proposing a ketamine-class antidepressant regimen with existing drugs. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.I.; Kegeles, L.S.; Levinson, A.; et al. Randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Proof-of-concept. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38(12), 2475–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, N. Triple glutamatergic augmentation for refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder: A five-patient case series. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, N. Case series: Marked improvement in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive symptoms with over-the-counter glutamatergic augmentation in routine clinical practice. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. Dosing schedules for dextromethorphan and piracetam in OCD: A case series on diurnal symptom patterns and split-dosing strategies. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, H.; Iijima, M.; Chaki, S. Involvement of AMPA receptor in both the rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects of ketamine in animal models. Behavioural Brain Research 2011, 224(1), 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Lee, B.; Liu, R.J.; et al. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science 2010, 329(5994), 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, B.; Bunn, H.; Santalucia, M.; et al. Dextromethorphan-bupropion (Auvelity) for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience 2023, 21(4), 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spina, E.; Santoro, V.; D’Arrigo, C. Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: An update. Clinical Therapeutics 2008, 30(7), 1206–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).