1. Introduction

Affecting approximately 20 million people globally in 2020, neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) develops in 10.0% of AMD cases and is the most common choroidal vascular disease. [

1,

2] Among retinal vascular diseases, diabetic retinopathy (DR) remains the most common and a leading cause of blindness in adults (20-74 years). [

1,

2] Diabetic macular edema (DME), one of DR complications, approximately affects 21 million individuals worldwide as of 2012. [

2,

3]

Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (Anti-VEGF) intravitreal injections have become a mainstay treatment for retinal diseases, including nAMD, DME, and retinal vein occlusion-related macular edema. [

4,

5] One of the novel anti-VEGF agents emerging is intravitreal faricimab (IVF) that is known for its dual inhibition of VEGF-A and Angiopoietin-2. [

6] Consistent evidence from several studies demonstrated that IVF yielded significant therapeutic benefits in both DME and nAMD, improving visual outcomes and resolving retinal fluid and pigment epithelial detachment. [

6,

7,

8,

9]

Despite their efficacy in treating retinal diseases, anti-VEGF agents such as brolucizumab have been associated with safety concerns. Although IOI is an infrequent complication of anti-VEGF agents, it approximately occurs in 6.0% of cases, with higher incidence among elderly patients, women, and following the second injection. [

10] Furthermore, sterility and contamination concerns related to needle filters, such as foreign particles, drug leakage, and structural defects, have raised further safety concerns regarding IVF. [

11] While these manufacturing issues were directly implicated in only a few IOI cases, including endophthalmitis, they highlight the need to improve quality control and surveillance systems to mitigate IOI risks. [

11,

12,

13]

These safety concerns become particularly relevant when evaluating IVF, which, despite proved therapeutic efficacy in clinical trials, lacks comprehensive real-world data on IOI risk profile in DME and nAMD patients. This systematic review and meta-analysis, therefore, aimed to evaluate IOI incidence, clinical characteristics, and risk following IVF injections.

2. Results

Study Selection

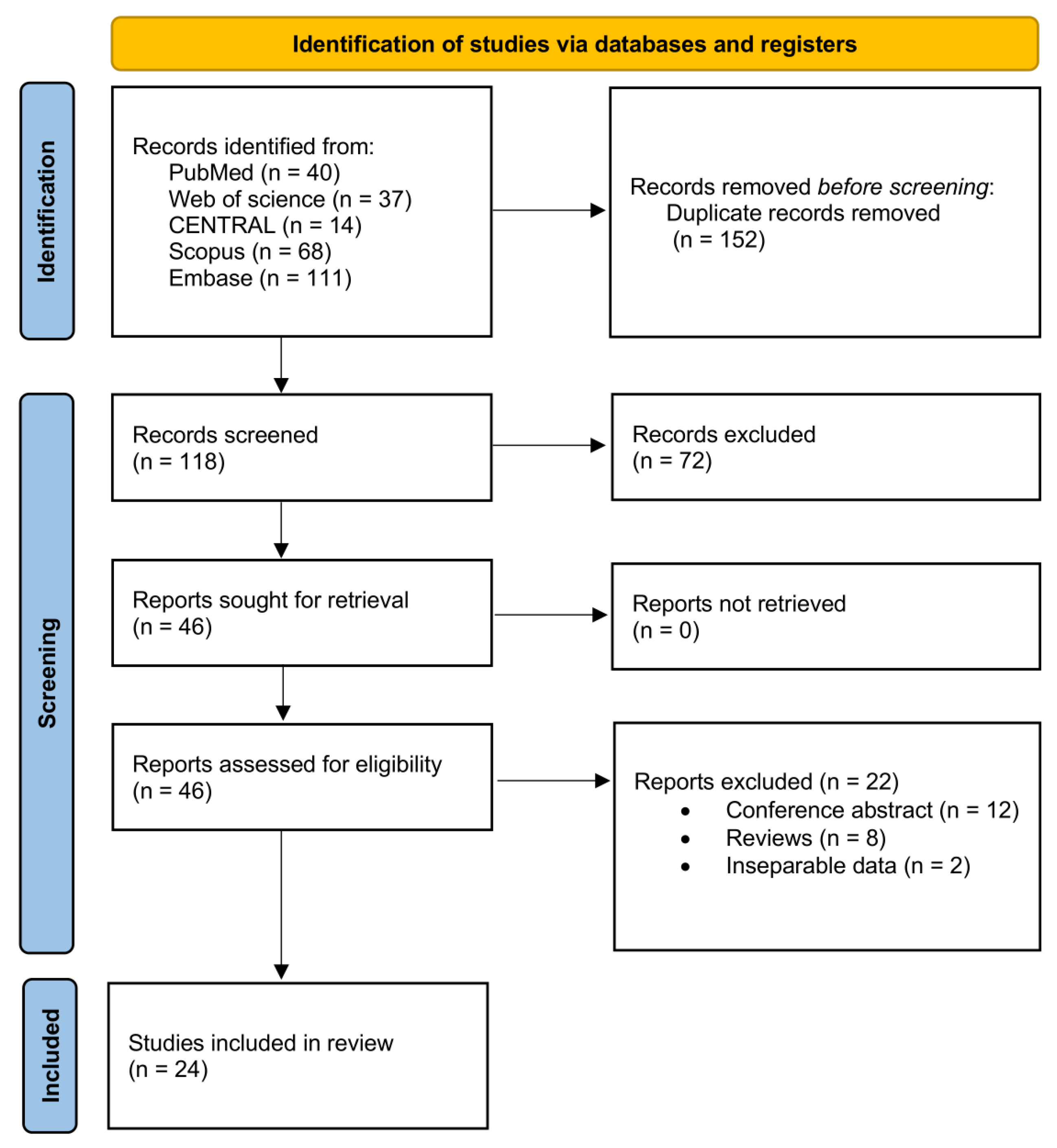

Our initial literature search of databases yielded a total of 270 articles (

Figure 1). After removing duplicate records, 118 articles were assessed for titles and abstracts screening. Out of these, 72 studies were excluded. Forty-six papers were selected for retrieval and were assessed for inclusion through a full-text review, resulting in excluding 22 articles that did not meet our inclusion criteria. Therefore, twenty-four articles were ultimately included in the analysis. [

13,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Our review included 4,761 patients receiving intravitreal faricimab (IVF), with a total of 5,652 eyes (

Table 1). The weighted mean age was 76.8 years (95% CI: 73.8 – 79.7), with a higher prevalence of females (n = 2,528, 52.1% [95% CI: 39.9 – 64.0]) compared to males (n = 1,731, 39.5% [95% CI: 32.1 – 47.5]). The most common diagnoses among patients were neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD; n = 4,782, 94.6% [95% CI: 85.3 – 98.1]) and diabetic macular edema (DME; n = 845, 37.1% [95% CI: 24.0 – 52.4];

Table 1).

In patients with a history of previous intravitreal injections (n = 659), aflibercept was the most commonly used agent (67.8% [95% CI: 56.8 – 77.0]), followed by ranibizumab (26.8% [95% CI: 17.1 – 39.2]), bevacizumab (17.8% [95% CI: 4.9 – 47.7]), and brolucizumab (3.1% [95% CI: 0.3 – 23.4];

Table 1). The weighted mean follow-up duration was 6.2 months (95% CI: 2.8 – 9.6;

Table 1).

Faricimab and associated Intraocular Inflammation (IOI)

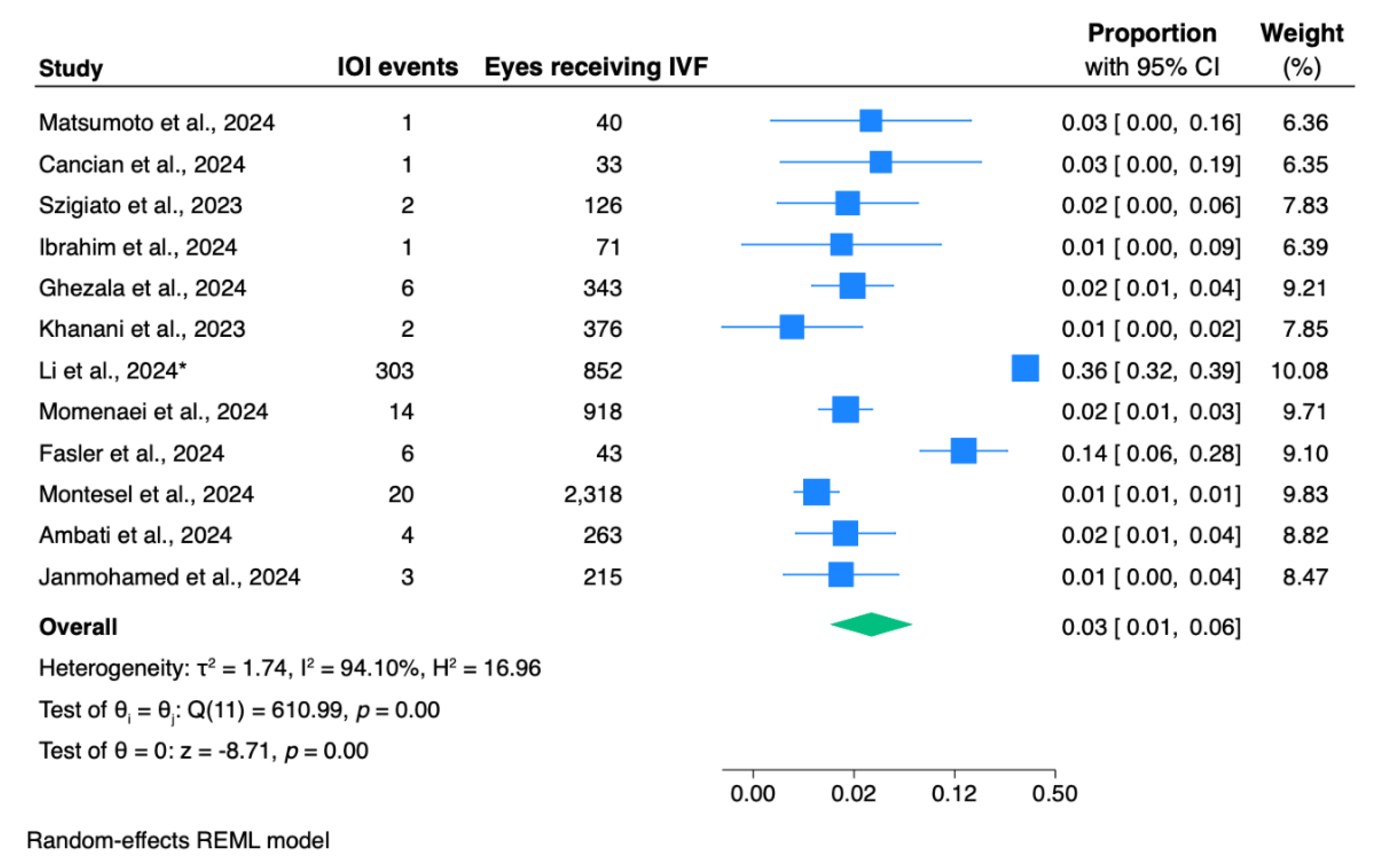

The pooled proportion for IOI incidence in eyes receiving IVF was 3.0% (95% CI: 1.0 – 6.0;

Figure 2).

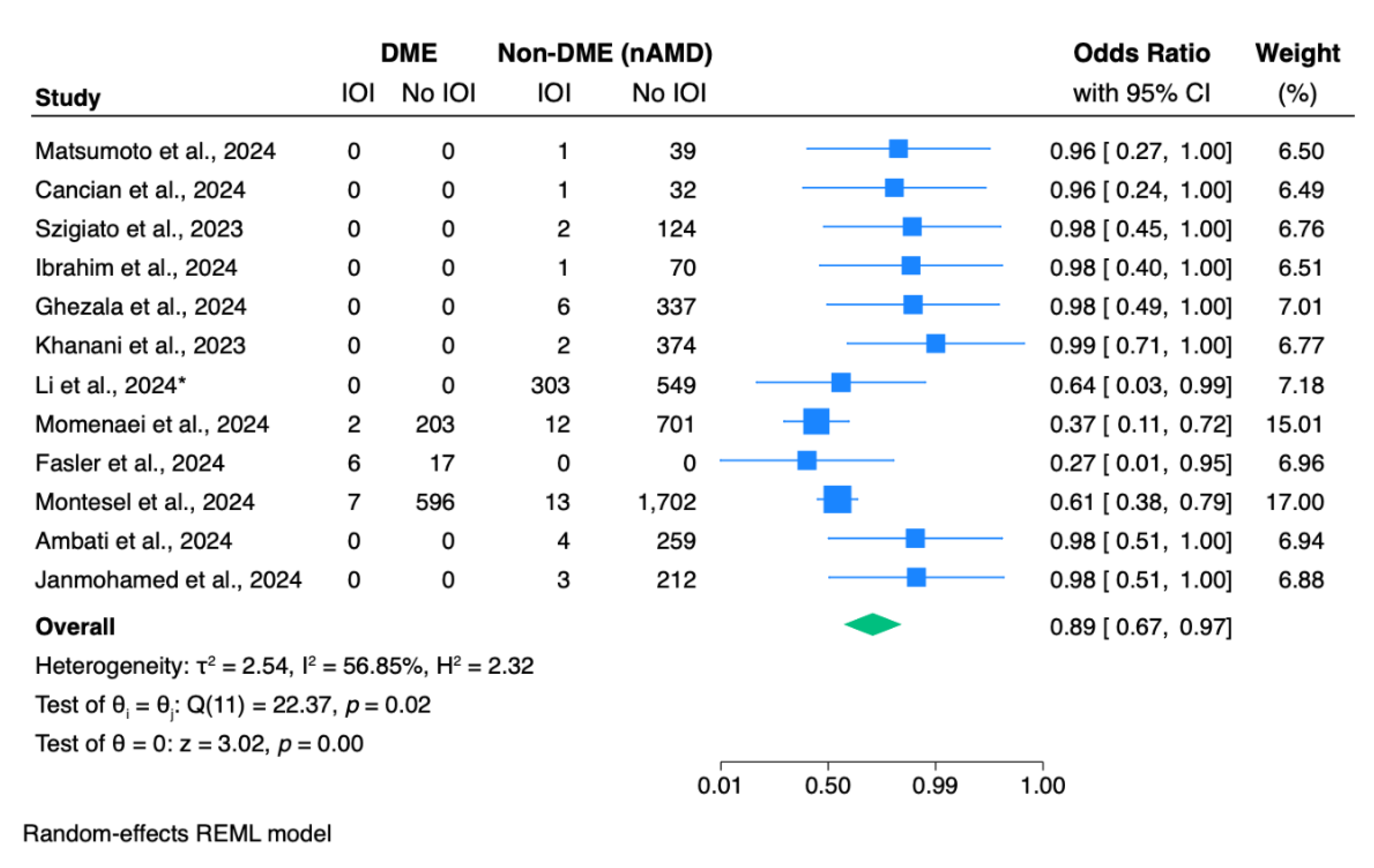

Meta-analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in IOI odds between the two most common diagnosis (p <0.01;

Figure 3). The overall pooled odds ratio is 0.89 (95% CI: 0.67 – 0.97), indicating that the odds of developing IOI are significantly lower in the DME group compared to the nAMD group (

Figure 3).

A total of 414 signs of IOI were included, with unspecified IOI being the most common (n = 210, 2.9% [95% CI: 1.2 – 7.3];

Table 1). Other common signs included anterior uveitis (n = 80, 1.9% [95% CI: 0.1 – 34.8]), vitritis (n = 63, 2.9% [95% CI: 0.2 – 32.1]), retinal hemorrhage (n = 27, 0.7% [95% CI: 0.0 – 15.3]), corneal edema (n = 14, 1.2% [95% CI: 0.3 – 4.6]), keratic precipitates (n = 9, 2.0% [95% CI: 0.2 – 22.1]), endophthalmitis (n = 8, 0.5% [95% CI: 0.3 – 1.1]), and hypopyon (n = 3, 1.9% [95% CI: 0.0 – 84.3];

Table 1).

For the overall incidence of IOI (

Supplementary Figure 1a), the pooled proportion remained stable and statistically significant across all studies, indicating that the result was not disproportionately influenced by any single study. The funnel plot (

Supplementary Figure 1b) showed no statistically significant evidence of publication bias (p = 0.209). While the sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the pooled odds ratio for IOI between DME and nAMD patients, Egger’s test indicated significant publication bias (p = 0.002), as visualized in the funnel plot (

Supplementary Figure 2).

3. Discussion

In our systematic review and meta-analysis, we included 24 studies with a total of 4,761 patients (5,652 eyes) receiving intravitreal faricimab (IVF). The weighted mean age of the cohort was 76.8 years, with a higher prevalence of females (n = 2,528, 52.1%). The most common diagnoses among patients were nAMD (94.6%) and DME (37.1%). We found a clinically relevant risk of IOI, the odds of developing IOI are significantly lower in the DME group compared to the nAMD group (OR: 0.89, p <0.01). The overall weighted mean follow-up duration was 6.2 months (95% CI: 2.8 – 9.6).

Our meta-analysis revealed a clinically significant IOI risk associated with IVF, with a pooled proportion of 3.0%. A meta-analysis of 14 randomized clinical trials (RCT; 6,759 eyes) conducted by Patil et al., 2022 showed that brolucizumab had higher risks of IOI compared to aflibercept, with a risk ratio of 6.24.44 Similarly, the MERLIN RCT conducted by Khanani et al., 2022 found that brolucizumab had a higher rate of IOI (9.3%) compared to aflibercept (4.5%) in nAMD patients.45 Stevanovic et al., 2025 reported that brolucizumab was also associated with a higher IOI rate compared to faricimab when administered to nAMD patients.46 These variations in IOI rates among anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents highlight that despite their efficacy, they pose risks of IOI, necessitating vigilant monitoring of patients.

The most common signs of IOI were anterior uveitis (n = 80, 1.9%), vitritis (n = 63, 2.9%), and retinal hemorrhage (n = 27, 0.7%). Less common sight-threatening signs were endophthalmitis (n = 8, 0.5%) and hypopyon (n = 3, 1.9%). Likewise, a narrative review conducted by Anderson et al., 2021 reported two types of IOI following intravitreal anti-VEGF injections: acute onset sterile inflammation and delayed onset inflammatory vasculitis. They also reported a rate of sterile uveitis or endophthalmitis, ranging from 0.05% to 4.4%, varying from one anti-VEGF agent to another.47 Similarly, other studies revealed that post-injection endophthalmitis’ rate ranged from 0.02 to 0.10% of injections.12,48,49

The spectrum of observed inflammatory signs, from anterior uveitis to endophthalmitis, points to a disruption of the eye’s immune homeostasis. This phenomenon may stem from abrupt VEGF inhibition, as these agents, despite their anti-inflammatory properties, can destabilize the ocular environment.50,51 Supporting this, Mesquida et al., 2014 demonstrated that elevated serum levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-17A, and hsCRP correlated with active uveitis in some inflammatory diseases, highlighting their potential as biomarkers for monitoring disease progression.52 Furthermore, anti-VEGF agents exhibit dual anti-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory properties, including suppression of TNF-α-induced VEGF effects and modulation of inflammatory pathways.53 However, their intravitreal administration may trigger IOI, possibly leading to sight-threatening complications.

The pathogenesis of DME appears to be inflammation-driven, while in nAMD, inflammatory processes may develop secondary to structural changes in the retinal pigment epithelium and Bruch’s membrane.54–56 These different mechanisms determine the management approach to achieve the optimal visual outcomes for the patients.56 Interestingly, in our meta-analysis, we found that patients with DME had a significantly lower risk of IOI after IVF administration compared to nAMD patients (OR: 0.89, p <0.01). Similarly, Abu Serhan et al.’s, 2024 meta-analysis reported significantly lower odds of IOI following brolucizumab injections in DME patients compared to those with nAMD.10 This difference could be attributed to the underlying immunosuppressed state of DME patients, which could potentially reduce IOI risk when compared to nAMD patients.57

Despite the IOI risk associated with anti-VEGF agents, they were proved effective in improving clinical outcomes in many patients. Binder et al., 2025 found that aflibercept had a 12.0% rate of IOI within 1 to 3 days after the injection; however, the BCVA of the patients did not decrease after the resolution of the IOI.58 Another study of 56 cases receiving aflibercept reported an initial loss of vision and IOI, within a mean time of 3.5 days after receiving the injections, yet they improved shortly after with topical therapies or more invasive interventions.59 Additionally, Aldokhail et al., 2024 demonstrated an overall reduction in CMT, ranging from 183.1 μm to 294 μm in DME patients after administring anti-VEGF therapy.60 These findings suggest that although prompt and careful intervention to resolve IOI is indicated, its risk is still manageable with favorable visual prognosis in patients receiving anti-VEGF agents.59,61

Our meta-analysis has some limitations. First, selection biases may exist mainly due to the inclusion of observational studies reporting IOI in eyes receiving IVF, which may be confounded by indication and variability in patient selection criteria and potentially overestimating the overall incidence of IOI. Second, small sample sizes in some of the included studies reduced statistical power, particularly for subgroup analyses and multiple or rare endpoints. Third, the lack of standardized IOI diagnostic criteria across studies may have led to under- or over-reporting of events. Variations in follow-up durations, treatment protocols, or concomitant medications may further limit the generalizability of our findings. Despite these limitations, our study has notable strengths, including the use of a random-effects model to account for heterogeneity, clear PRISMA adherence, and the largest pooled sample size to date for IOI risk associated with IVF.

4. Materials and Methods

Literature Search

A systematic review and meta-analysis, registered with PROSPERO (CRD420250650532), were conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. [

14] PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases were searched from inception to February 2025. A medical subject headings (MeSH) term and keyword search of each database were conducted using the Boolean operators OR and AND. Terms used were as follows: (“occlusive vasculitis” OR “Intraocular inflammation” OR “retinal vasculitis” OR “intra-ocular inflammation” OR “vitritis”) AND (“faricimab”) (

Supplementary Table 1).

Study Selection

Pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria were deductively defined. Studies were included if they were randomized clinical trials, retrospective or prospective studies, and case reports of patients who were treated with faricimab injections and showed IOI as an adverse event. Studies were excluded if they 1) reported patients with IOI due to other pre-existing ocular pathologies and 2) were animal studies, meta-analyses, reviews, editorials, letters, or books, 3) contained insufficient clinical data ( lacking one of the following: patient demographics or management details and outcomes), and 4) were not written in English language.

Two authors (A.A.Y. and R.SH.) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of all extracted papers based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies that met inclusion criteria were then further evaluated independently with full text review by the same two authors, andvdisagreements were resolved via a third author (J.Q.). References of the included articles were also screened to retrieve additional relevant articles.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data from included studies were extracted by two authors (A.A.Y. and R.SH.) and confirmed independently by one author (J.Q.) to ensure accuracy. Extraction variables included: 1) author’s name, 2) date of publication, 3) level of evidence, 4) sample size, 5) age and sex, 6) clinical features, 7) previous injections: number per patient and type, 8) signs of IOI, 9) change in central corneal thickness, 10) change in best-corrected visual acuity, and 11) follow-up duration. The level of evidence of each article was evaluated following the 2011 Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine guidelines. [

15] The included articles were categorized as level II to VI. [

13,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]

Statistical Analysis

Stata (StataCorp. 2025. Stata Statistical Software: Release 19. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.) was used for all statistical analyses. Continuous variables were summarized as weighted means (effect size of means) and confidence intervals (95% CI), whereas categorical variables were summarized as weighted proportions (effect size of proportions) and 95% CI. The χ

2 (z) test was used to test significance among simple proportions. Meta-analyses of weighted means, proportions, and odds ratios (OR) were conducted for pooled means, proportions, and odds ratios, using the random-effects model. [

39] Studies with fewer than 30 patients receiving IVF were excluded from the analysis of overall IOI incidence, IOI incidence stratified by diagnosis, and IOI signs to minimize potential overestimation. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The χ

2 (z) test and the Higgins I

2 test were used to assess studies heterogeneity. [

40] A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of the meta-analytic findings. Funnel plots and Egger’s test (p<0.05 indicating the presence of bias) were used to identify publication bias. [

41] Risk of bias assessment was performed using the JBI tool. [

42,

43]

5. Conclusions

IVF is an effective anti-VEGF therapy with a clinically significant IOI risk in patients with DME and nAMD. We recommend a vigilant monitoring routine for patients receiving IVF to mitigate sight-threatening complications. Further long-term, real-world studies are warranted to evaluate IVF safety profile, standardize IOI definitions, and establish monitoring strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplementary

Table 1. Search Strategy for each database (PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane library). Supplementary

Figure 1. Overall incidence of intraocular inflammation following intravitreal faricimab injection: (a) sensitivity analysis and (b) funnel plot for assessing publication bias. CI, confidence interval; REML, random-effects maximum likelihood. Supplementary

Figure 2. Analysis of odds ratios for intraocular inflammation in patients with diabetic macular edema compared to those with neovascular age-related macular degeneration receiving intravitreal faricimab: (a) sensitivity analysis and (b) funnel plot for assessing publication bias. CI, confidence interval; REML, random-effects maximum likelihood.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Q. and H.A-S.; methodology, J.Q.; software, J.Q.; validation, J.Q. and H.A-S.; formal analysis, J.Q.; investigation, J.Q., A.A.Y., and R.SH.; resources, J.Q. and H.A-S.; visualization, J.Q.; data curation, J.Q. and A.A.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Q.; writing—review and editing, A.A.Y., R.SH., and H.A-S.; supervision, H.A-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IOI |

Intraocular inflammation |

| IVF |

Intravitreal Faricimab |

| nAMD |

Neovascular age-related macular degeneration |

| DME |

Diabetic macular edema |

References

- Ong JX, Fawzi AA. Perspectives on diabetic retinopathy from advanced retinal vascular imaging. Eye (Lond). 2022;36(2):319-327. [CrossRef]

- Hariprasad SM, Holz FG, Asche C V., et al. Clinical and Socioeconomic Burden of Retinal Diseases: Can Biosimilars Add Value? A Narrative Review. Ophthalmol Ther. 2025;14(4):621. [CrossRef]

- Campochiaro PA. Retinal and Choroidal Vascular Diseases: Past, Present, and Future: The 2021 Proctor Lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62(14). [CrossRef]

- Hang A, Feldman S, Amin AP, Ochoa JAR, Park SS. Intravitreal Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapies for Retinal Disorders. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16(8):1140. [CrossRef]

- Marneros AG, Fan J, Yokoyama Y, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in the retinal pigment epithelium is essential for choriocapillaris development and visual function. Am J Pathol. 2005;167(5):1451-1459. [CrossRef]

- Panos GD, Lakshmanan A, Dadoukis P, Ripa M, Motta L, Amoaku WM. Faricimab: Transforming the Future of Macular Diseases Treatment - A Comprehensive Review of Clinical Studies. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2023;17:2861. [CrossRef]

- Penha FM, Masud M, Khanani ZA, et al. Review of real-world evidence of dual inhibition of VEGF-A and ANG-2 with faricimab in NAMD and DME. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2024;10(1). [CrossRef]

- Tamiya R, Hata M, Tanaka A, et al. Therapeutic effects of faricimab on aflibercept-refractory age-related macular degeneration. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1). [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary V, Guymer R, Artignan A, Downey A, Singh RP. Real-World Evidence for Faricimab in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Diabetic Macular Edema: A Scoping Review. Ophthalmology science. 2025;5(4). [CrossRef]

- Abu Serhan H, Hassan AK, Rifai M, et al. Effect Modifiers and Risk Factors of Intraocular Inflammation Following Brolucizumab: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Curr Eye Res. Published online 2025. [CrossRef]

- Alkhawaldeh IM, Abu Serhan H. Intraocular Inflammation with faricimab: insights from Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database. EYE. 2024;38(13):2494-2496. [CrossRef]

- Meredith TA, McCannel CA, Barr C, et al. Postinjection endophthalmitis in the comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trials (CATT). Ophthalmology. 2015;122(4):817-821. [CrossRef]

- Thangamathesvaran L, Kong J, Bressler SB, et al. Severe Intraocular Inflammation Following Intravitreal Faricimab. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024;142(4):365-370. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372. [CrossRef]

- OCEBM Levels of Evidence — Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM), University of Oxford. Accessed July 16, 2023. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence.

- Matsumoto H, Hoshino J, Nakamura K, Akiyama H. One-year results of treat-and-extend regimen with intravitreal faricimab for treatment-naïve neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2024;68(2):83-90. [CrossRef]

- Le HM, Querques G, Guenoun S, et al. Acute intra ocular inflammation following intravitreal injections of faricimab: A multicentric case series. Eur J Ophthalmol. Published online December 2024:11206721241306224. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Wang X, Li X. Intra-Ocular Inflammation and Occlusive Retinal Vasculitis Following Intravitreal Injections of Faricimab: A Case Report. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2024;32(10):2544-2547. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Chong R, Fung AT. Association of Occlusive Retinal Vasculitis With Intravitreal Faricimab. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024;142(5):489-491. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui MZ, Durrani A, Smith BT. Faricimab-Associated Retinal Vasculitis. J Vitreoretin Dis. 2024;8(5):627-630. [CrossRef]

- Cancian G, Paris A, Agliati L, et al. One-Year Real-World Outcomes of Intravitreal Faricimab for Previously Treated Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmol Ther. 2024;13(11):2985-2997. [CrossRef]

- Szigiato A, Mohan N, Talcott KE, et al. Short-Term Outcomes of Faricimab in Patients with Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration on Prior Anti-VEGF Therapy. Ophthalmol Retina. 2024;8(1):10-17. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim FNI, Teo KYC, Tan TE, et al. Initial experiences of switching to faricimab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in an Asian population. FRONTIERS IN OPHTHALMOLOGY. 2024;3. [CrossRef]

- Bourdin A, Cohen SY, Nghiem-Buffet S, et al. Vitritis following intravitreal faricimab: a retrospective monocentric analysis. GRAEFES ARCHIVE FOR CLINICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL OPHTHALMOLOGY. Published online 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ben Ghezala I, Gabrielle PH, Sibert M, et al. Severe Intraocular Inflammation After Intravitreal Injection of Faricimab: A Single-Site Case Series of Six Patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2025;269:11-19. [CrossRef]

- Khanani AM, Aziz AA, Khan H, et al. The real-world efficacy and safety of faricimab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: the TRUCKEE study - 6 month results. Eye (Lond). 2023;37(17):3574-3581. [CrossRef]

- Palmieri F, Younis S, Hamoud AB, Fabozzi L, Bedan Hamoud A, Fabozzi L. Uveitis Following Intravitreal Injections of Faricimab: A Case Report. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2024;32(8):1873-1877. [CrossRef]

- Reichel FF, Kiraly P, Vemala R, Hornby S, De Silva SR, Fischer MD. Occlusive retinal vasculitis associated with intravitreal Faricimab injections. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2024;14(1). [CrossRef]

- Bruening W, Kim S, Yeh S, Rishi P, Conrady CD. Inflammation and Occlusive Retinal Vasculitis Post Faricimab. JAMA Ophthalmol. Published online January 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kitson S, McAllister A. A case of hypertensive uveitis with intravitreal faricimab. Retin Cases Brief Rep. Published online December 2023. [CrossRef]

- Parakh S, Bhatt V, Das S, Lakhlan P, Luthra G, Luthra S. Intraocular Inflammation Following Intravitreal Faricimab Injection in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Cureus. 2024;16(12):e75937. [CrossRef]

- Montesel A, Sen S, Preston E, et al. Intraocular Inflammation (IOI) Associated with Faricimab Therapy: One-year Real World Outcomes. Retina. Published online January 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ambati NR, Leone A, Brill D, Sisk RA. Real-World Long-Term Outcomes of Intravitreal Faricimab in Previously Treated Chronic Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Retina. Published online November 2024. [CrossRef]

- Janmohamed IK, Mushtaq A, Kabbani J, et al. 1-Year real-world outcomes of faricimab in previously treated neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Eye (Lond). Published online January 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cozzi M, Ziegler A, Fasler K, Muth DR, Blaser F, Zweifel SA. Sterile Intraocular Inflammation Associated With Faricimab. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024;142(11):1028-1036. [CrossRef]

- Fasler K, Muth DR, Cozzi M, et al. Dynamics of Treatment Response to Faricimab for Diabetic Macular Edema. Bioengineering (Basel). 2024;11(10). [CrossRef]

- Momenaei B, Wang K, Kazan AS, et al. Rates of Ocular Adverse Events after Intravitreal Faricimab Injections. Ophthalmol Retina. 2024;8(3):311-313. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Lu Y, Song Z, Liu Y. A real-world data analysis of ocular adverse events linked to anti-VEGF drugs: a WHO-VigiAccess study. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15. [CrossRef]

- Riley RD, Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ. 2011;342(7804):964-967. [CrossRef]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539-1558. [CrossRef]

- Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343(7818). [CrossRef]

- Barker TH, Stone JC, Sears K, et al. Revising the JBI quantitative critical appraisal tools to improve their applicability: an overview of methods and the development process. JBI Evid Synth. 2023;21(3):478-493. [CrossRef]

- Munn Z, Stone JC, Aromataris E, et al. Assessing the risk of bias of quantitative analytical studies: introducing the vision for critical appraisal within JBI systematic reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2023;21(3):467-471. [CrossRef]

- Patil NS, Dhoot AS, Popovic MM, Kertes PJ, Muni RH. RISK OF INTRAOCULAR INFLAMMATION AFTER INJECTION OF ANTIVASCULAR ENDOTHELIAL GROWTH FACTOR AGENTS: A Meta-analysis. Retina. 2022;42(11):2134-2142. [CrossRef]

- Khanani AM, Brown DM, Jaffe GJ, et al. MERLIN: Phase 3a, Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Masked Trial of Brolucizumab in Participants with Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Persistent Retinal Fluid. Ophthalmology. 2022;129(9):974-985. [CrossRef]

- Stevanovic M, Koulisis N, Chen T, et al. Intraocular Inflammation, Safety Events, and Outcomes After Intravitreal Injection of Ranibizumab, Aflibercept, Brolucizumab, Abicipar Pegol, and Faricimab for nAMD. J Vitreoretin Dis. Published online 2025. [CrossRef]

- Anderson WJ, da Cruz NFS, Lima LH, Emerson GG, Rodrigues EB, Melo GB. Mechanisms of sterile inflammation after intravitreal injection of antiangiogenic drugs: a narrative review. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2021;7(1). [CrossRef]

- Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, et al. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(14):1432-1444. [CrossRef]

- Heier JS, Brown DM, Chong V, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept (VEGF trap-eye) in wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(12):2537-2548. [CrossRef]

- Cox JT, Eliott D, Sobrin L. Inflammatory Complications of Intravitreal Anti-VEGF Injections. J Clin Med. 2021;10(5):981. [CrossRef]

- Cox JT, Eliott D, Sobrin L. Inflammatory Complications of Intravitreal Anti-VEGF Injections. J Clin Med. 2021;10(5):981. [CrossRef]

- Mesquida M, Leszczynska A, Llorenç V, Adán A. Interleukin-6 blockade in ocular inflammatory diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;176(3):301-309. [CrossRef]

- Ascaso FJ, Huerva V, Grzybowski A. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of macular edema secondary to retinal vascular diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014. [CrossRef]

- Hageman GS, Luthert PJ, Victor Chong NH, Johnson L V., Anderson DH, Mullins RF. An Integrated Hypothesis That Considers Drusen as Biomarkers of Immune-Mediated Processes at the RPE-Bruch’s Membrane Interface in Aging and Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20(6):705-732. [CrossRef]

- Gui F, You Z, Fu S, Wu H, Zhang Y. Endothelial Dysfunction in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:570183. [CrossRef]

- Vujosevic S, Lupidi M, Donati S, Astarita C, Gallinaro V, Pilotto E. Role of inflammation in diabetic macular edema and neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 2024;69(6):870-881. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Zhang J, Zhang C, et al. Diabetic Macular Edema: Current Understanding, Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Cells. 2022;11(21):3362. [CrossRef]

- Binder KE, Bleidißel N, Charbel Issa P, Maier M, Coulibaly LM. Noninfectious Intraocular Inflammation After Intravitreal Aflibercept. JAMA Ophthalmol. Published online 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hahn P, Chung MM, Flynn HW, et al. Postmarketing analysis of aflibercept-related sterile intraocular inflammation. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(4):421-426. [CrossRef]

- Aldokhail LS, Alhadlaq AM, Alaradi LM, Alaradi LM, AlShaikh FY. Outcomes of Anti-VEGF Therapy in Eyes with Diabetic Macular Edema, Vein Occlusion-Related Macular Edema, and Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2024;18:3837-3851. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg RA, Shah CP, Wiegand TW, Heier JS. Noninfectious inflammation after intravitreal injection of aflibercept: clinical characteristics and visual outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158(4):733-737.e1. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).