Introduction

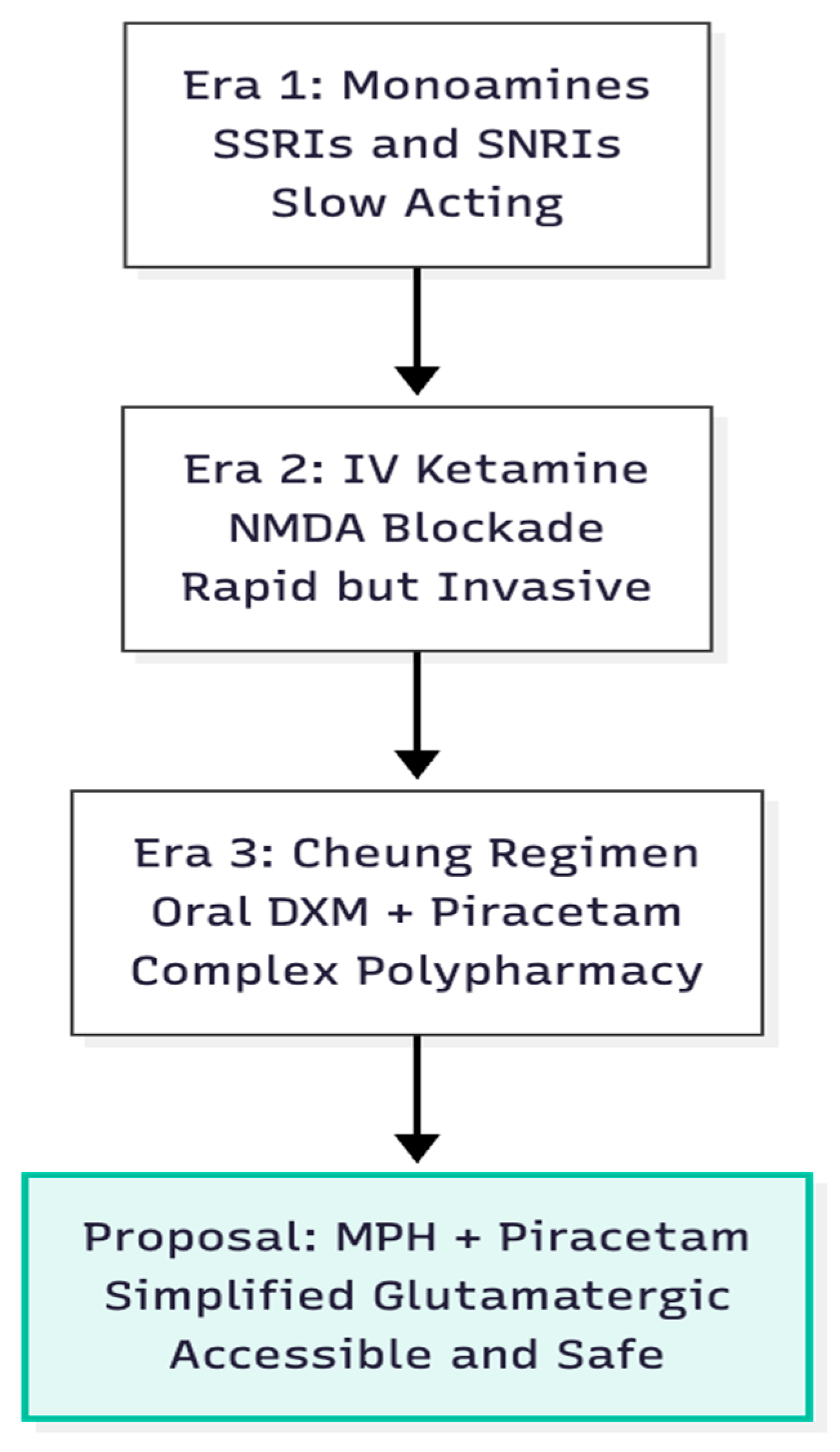

Ketamine's ability to lift mood within hours revolutionised biological psychiatry, positioning glutamatergic circuitry—rather than serotonin or noradrenaline—as the fulcrum of rapid symptom change (1). Ketamine blocks NMDA receptors on GABA interneurones, disinhibits pyramidal cells, and sparks a glutamate surge that stimulates postsynaptic AMPA receptors, triggering mTOR-dependent synaptogenesis (2, 3). Cheung translated this intravenous logic into an oral, four-component stack featuring dextromethorphan (DXM) as the NMDA antagonist plus piracetam to enhance AMPA throughput (4). The central hypothesis here is that methylphenidate, long used for ADHD, can replace DXM as the glutamate "push," permitting a simpler two-drug protocol when joined with piracetam. Unlike DXM, which frees glutamate via interneurone disinhibition, MPH raises synaptic glutamate through dopamine-transporter blockade and D1-receptor signalling (5). The pivotal question is whether the MPH–piracetam pair can deliver comparable plasticity with fewer moving parts and a wider safety margin (

Figure 1).

Mechanistic Rationale: Replicating the AMPA-Dominant State

The Ketamine and HNK Template

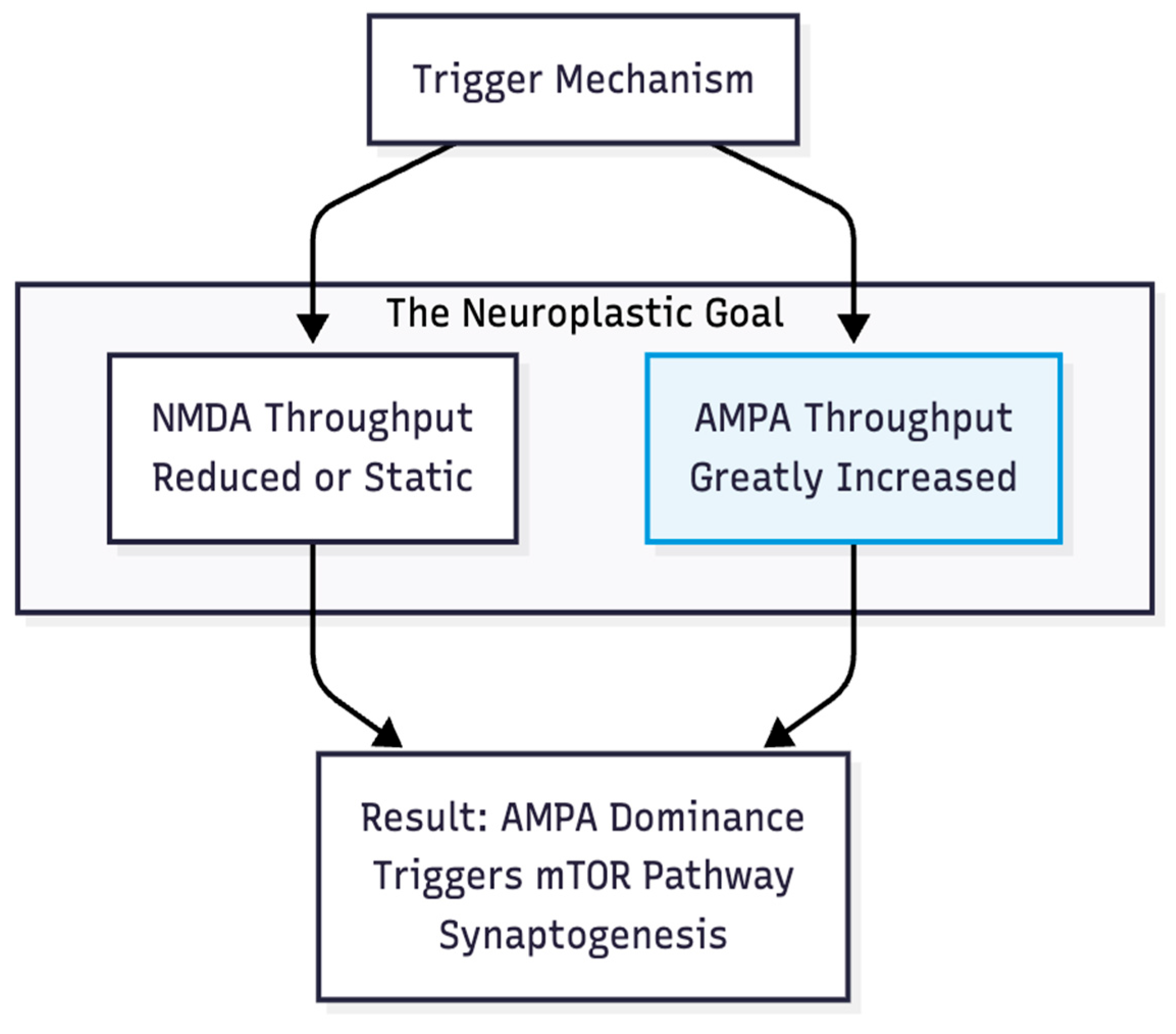

Hypothesis 1: Whatever the upstream trigger, lasting relief emerges when the AMPA/NMDA throughput ratio tilts steeply toward AMPA. Work on the ketamine metabolite (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine shows antidepressant effects that persist without direct NMDA blockade yet vanish if AMPA receptors are blocked (3). The endpoint, therefore, is AMPA dominance, not NMDA inhibition per se (

Figure 2).

Methylphenidate as the Glutamate Source

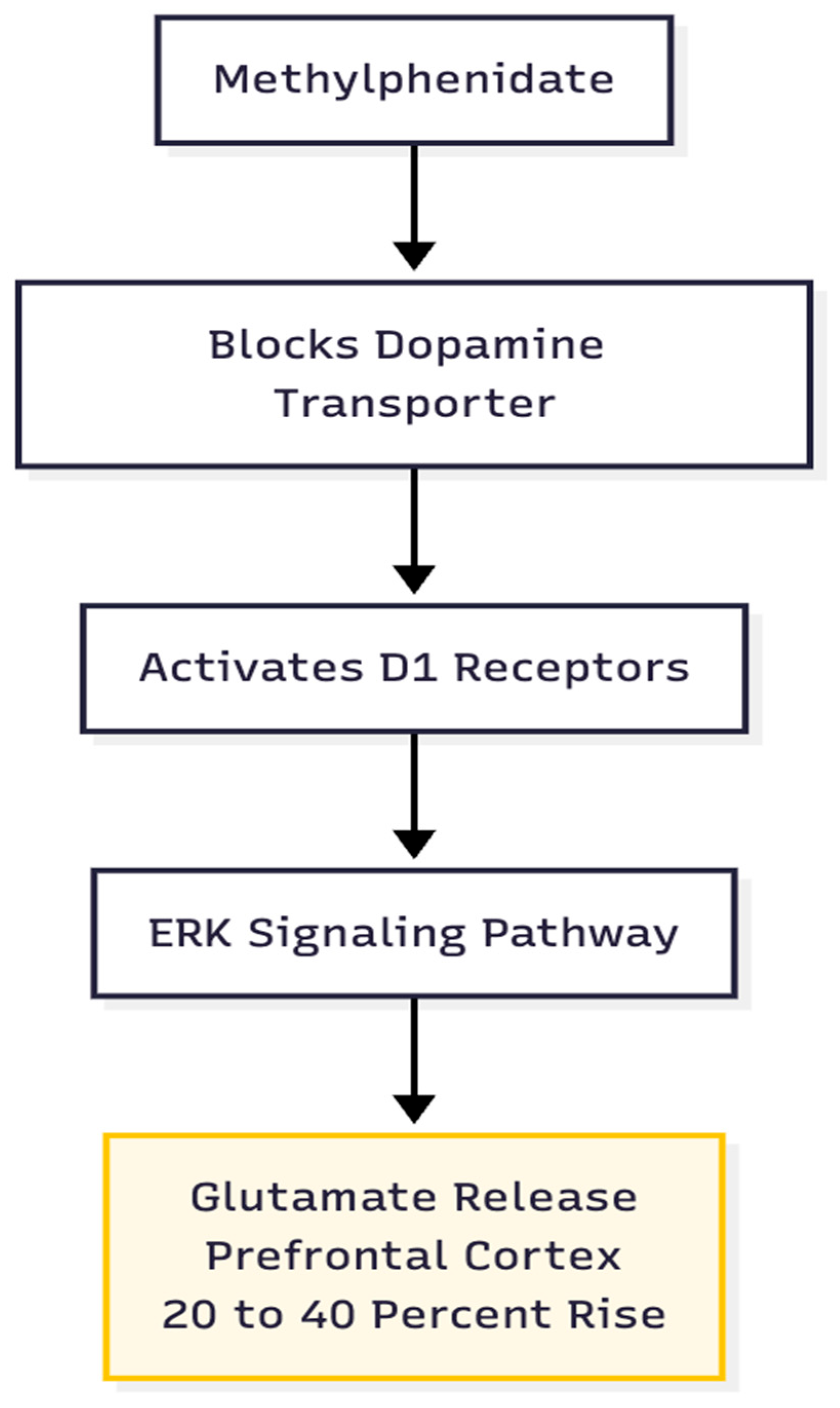

Hypothesis 2: MPH supplies a glutamate rise of sufficient amplitude and duration to start the plasticity cascade. Therapeutic doses boost prefrontal glutamate by roughly 20–40 % via a D1/ERK pathway and prompt transient insertion of GluA1-containing AMPA receptors into dendritic spines (5). In contrast to Cheung's DXM-driven burst, the MPH signal is smaller but more focused, enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio of cortical transmission (

Figure 3).

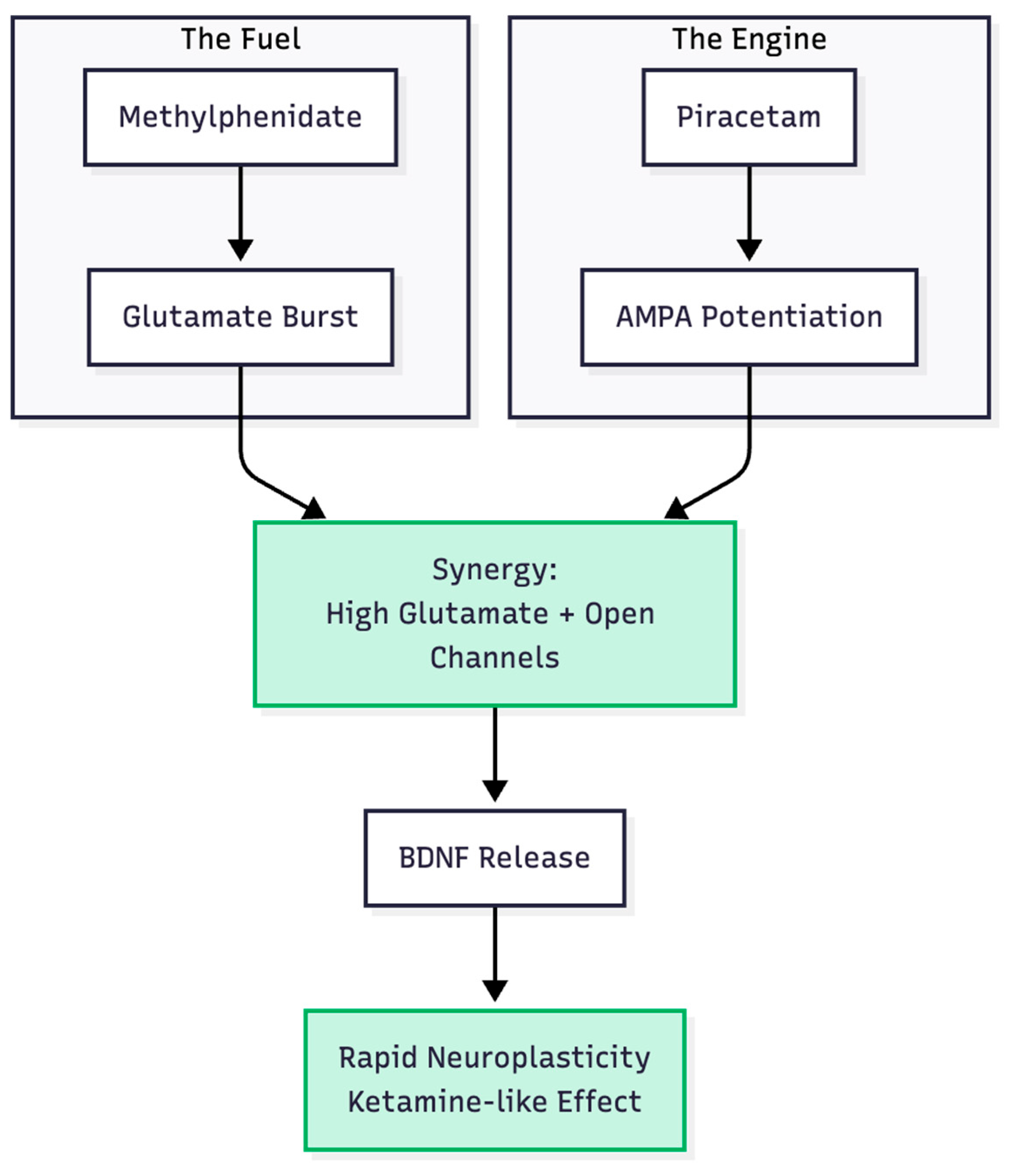

Piracetam as the AMPA Amplifier

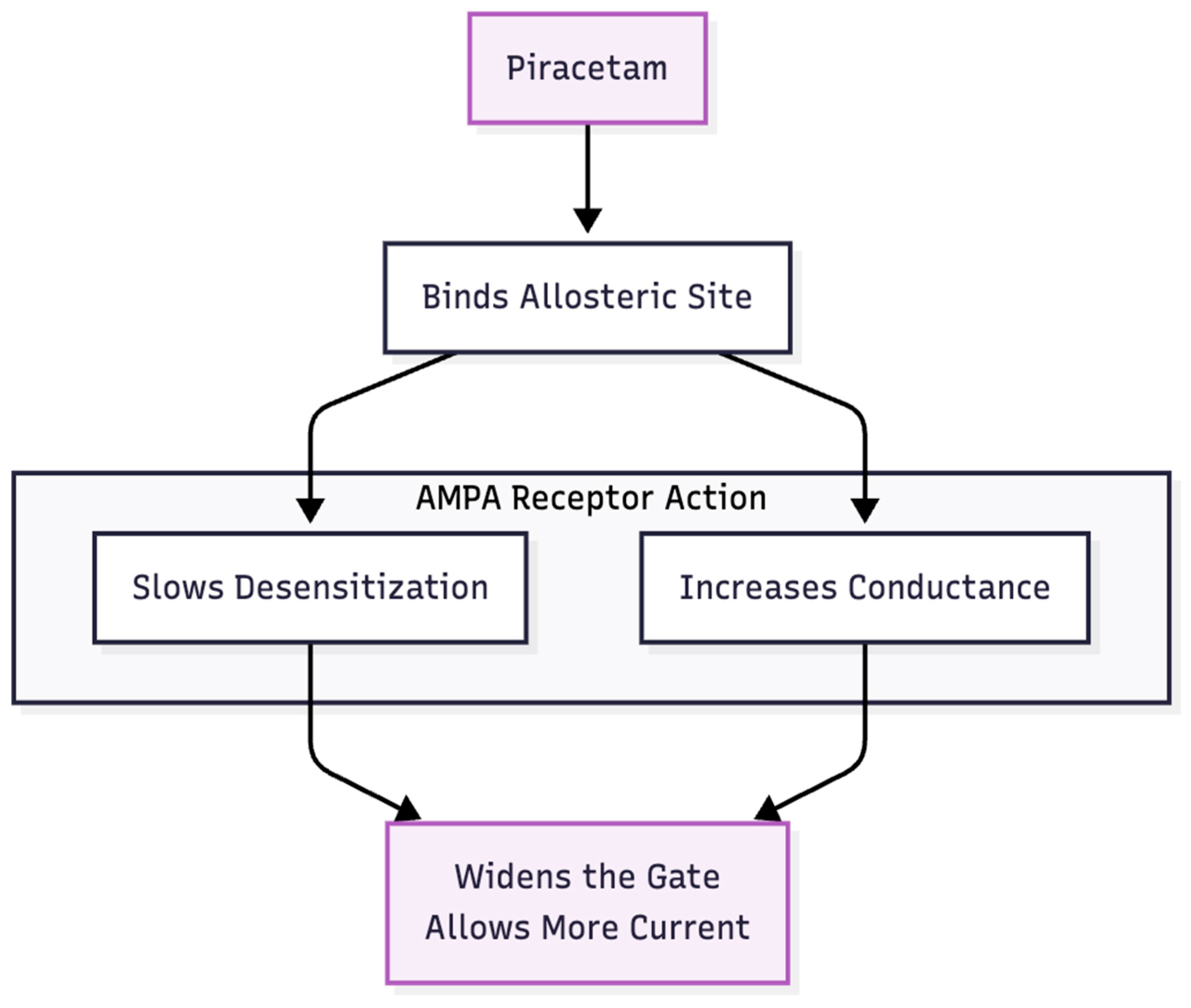

Hypothesis 3: Piracetam enlarges the MPH signal by slowing AMPA-receptor desensitisation and increasing channel conductance (6, 7) (

Figure 4). In combination, MPH furnishes the "fuel" (glutamate) and piracetam widens the gate, enabling BDNF release and synaptic repair consistent with Li et al.'s (8) mTOR model. Thus, a two-step process—chemical push, receptor pull—may emulate the AMPA-dominant state achieved by ketamine or the full Cheung stack (

Figure 5).

Safety and Excitotoxicity: Methylphenidate vs. Amphetamines

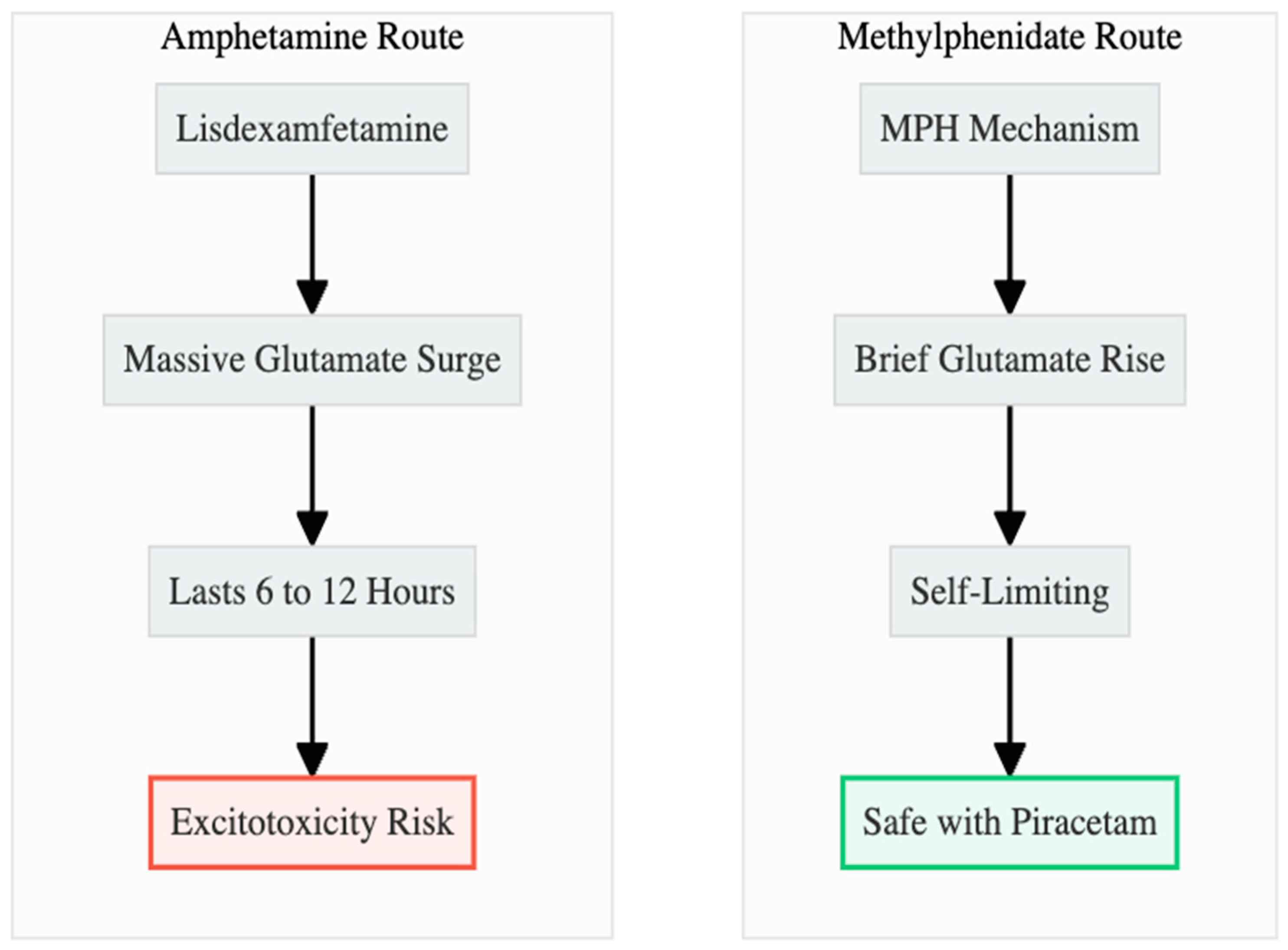

The Dangers of Amphetamines (Vyvanse)

Hypothesis 4: Amphetamine stimulants, when combined with an AMPA potentiator, can cause excitotoxicity because they cause too much glutamate to flow for a long time (

Figure 6). Lisdexamfetamine inhibits VMAT-2 and astrocytic EAAT-2, leading to glutamate elevations of 40–100% that endure for 6–12 hours and are linked to hyperthermia and oxidative stress (9, 10, 11). If there is no NMDA brake, piracetam could make this surge worse by breaking down the ability of calcium to buffer (12, 13).

The Safety Profile of Methylphenidate

Hypothesis 5: MPH is a safer partner because its glutamate rise is modest, region-restricted, and self-terminating (

Figure 6). Plasma clearance within three hours allows extracellular glutamate to normalise rapidly (14). Higher therapeutic doses even dampen excitatory drive, imposing a pharmacological ceiling (5). These kinetics argue that adding piracetam is unlikely to produce the sustained calcium influx that underlies excitotoxic death.

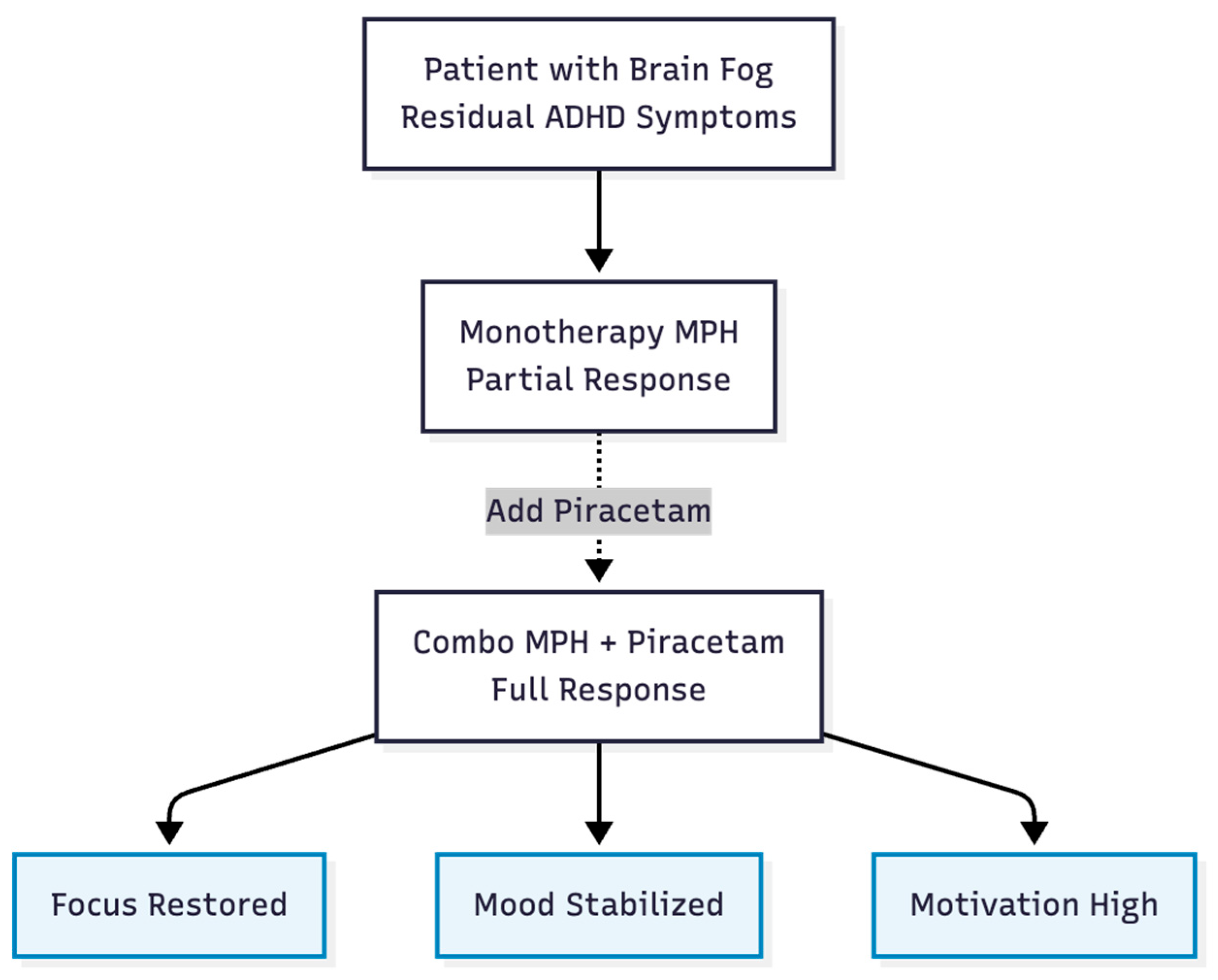

Clinical Evidence and Efficacy

Hypothesis 6: Patients who still have executive dysfunction or "brain fog" can get quick, combination-dependent benefits from MPH + piracetam that they can't get from either drug alone (

Figure 7). A real-life case of a 28-year-old woman with ADHD backs up this claim: adding 1,200 mg of piracetam to 18 mg of MPH improved her attention, mood, and motivation. The benefits went away when piracetam was stopped and came back when it was started again (15). A randomized study also supports the idea of synergy by showing that cognitive performance is better with the same combo than with just one stimulant (16).

Warning: Iatrogenic Risks in the Developing Brain

Any discussion of glutamatergic enhancement must account for developmental timing. The Cheung stack—dextromethorphan to lift NMDA "brakes," piracetam to widen AMPA throughput, glutamine to replenish substrate—intentionally accelerates synaptogenesis. In an adolescent or adult whose cortical networks have already undergone pruning, that push can replenish sparse spines and restore signal-to-noise. In children of roughly ten years or younger, however, the same chemistry collides with an opposite biological agenda: the brain is busy trimming excess excitatory contacts, not adding new ones (17). Over-activating mTOR pathways at this stage risks reproducing the "exuberant" connectivity that marks early autism, where synaptic density in frontal and temporal regions may exceed neurotypical levels by as much as 50 % (18, 19). By simultaneously disinhibiting pyramidal firing and prolonging AMPA currents, the regimen could aggravate the very cascades that derail pruning, lowering cortical signal fidelity and fostering the noise that manifests clinically as sensory overload or perseverative behaviour.

The practical implication is stark: in pre-pubertal brains the Cheung protocol or the MPH + Piracetam combination is not merely sub-optimal, it is potentially harmful. A sustained period of chemically enforced hyper-plasticity could entrench or even precipitate the synaptic surplus that underlies autistic symptom clusters—social disengagement, repetitive motor loops, heightened reactivity to sound or light. Given this iatrogenic threat, clinicians should regard the full NMDA-plus-AMPA stack as contraindicated in children under eleven, reserving it for patients whose neural architecture has already traversed the critical window for pruning and is demonstrably in need of rebuilding rather than reduction.

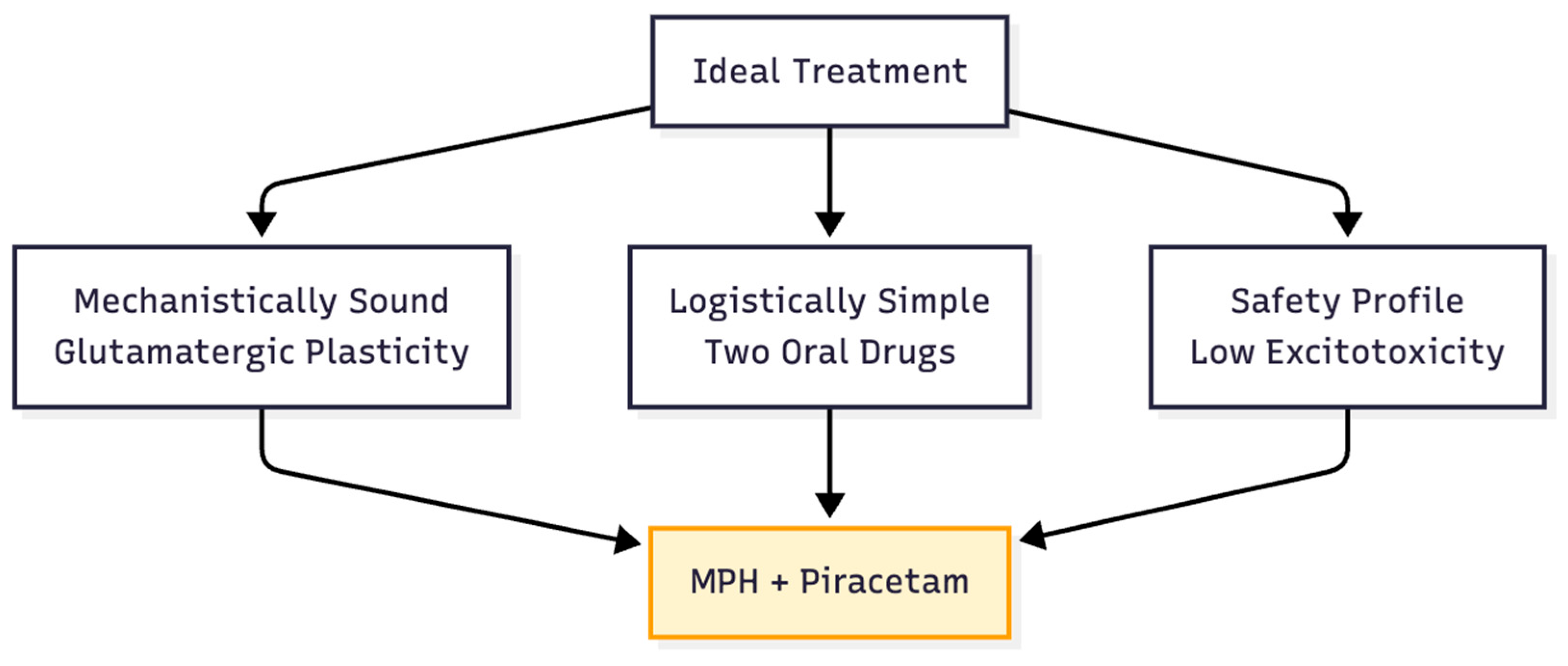

Conclusion

The hypotheses that were gathered make sense together. MPH gives a short, targeted boost of glutamate, and piracetam increases AMPA throughput.Together, they may recreate the neuroplastic signature of ketamine without the logistical burden of the Cheung quartet or the excitotoxic risk of amphetamines. In cell cultures, animal models, and controlled human trials, each claim can be proven false. If the data line up, doctors could get a cheap two-drug tool for treating hard-to-treat depression, ADHD, and cognitive fatigue. This tool would stay within the rules but use the newest science of rapid plasticity (

Figure 8).

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Ethics Declaration

Not applicable.

References

- Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;47(4):351-354.

- Duman RS, Aghajanian GK. Synaptic dysfunction in depression: Potential therapeutic targets. Science. 2016;338(6103):68–72.

- Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, et al. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature. 2016;533(7604):481-486.

- Cheung N. DXM, CYP2D6-inhibiting antidepressants, piracetam, and glutamine: Proposing a ketamine-class antidepressant regimen with existing drugs. Preprints. 2025.

- Cheng J, Xiong Z, Duffney LJ, et al. Methylphenidate exerts dose-dependent effects on glutamate receptors and behaviors. Biological Psychiatry. 2014;76(12):953–962.

- Ahmed AH, Oswald RE. Piracetam defines a new binding site for allosteric modulators of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid (AMPA) receptors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;53(5):2197–2203.

- Gualtieri F, Manetti D, Romanelli MN, et al. Design and study of piracetam-like nootropics, controversial members of the problematic class of cognition-enhancing drugs. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2002;8(2):125–138.

- Li N, Lee B, Liu RJ, et al. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science. 2010;329(5994):959–964.

- Rowley HL, Kulkarni RS, Gosden J, et al. Differences in the neurochemical and behavioural profiles of lisdexamfetamine, methylphenidate and modafinil in freely moving rats. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2014;28(3):254–269.

- Underhill SM, Colt MS, Amara SG. Amphetamine stimulates endocytosis of the norepinephrine and neuronal glutamate transporters in cultured locus coeruleus neurons. Neurochemical Research. 2020;45(6):1410–1419.

- Yamamoto BK, Moszczynska A, Gudelsky GA. Amphetamine toxicities: Classical and emerging mechanisms. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1187:101–121.

- Fleckenstein AE, Volz TJ, Riddle EL, et al. New insights into the mechanism of action of amphetamines. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2007;47:681–698.

- Guo C, Ma YY. Calcium-permeable AMPA receptors and excitotoxicity in neurological disorders. Frontiers in Neural Circuits. 2021;15:711564.

- Koda K, Ago Y, Cong Y, et al. Effects of acute and chronic administration of atomoxetine and methylphenidate on extracellular levels of monoamines in the mouse prefrontal cortex and striatum. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2010;114(1):259–270.

- Cheung N. Augmentation of Methylphenidate with Piracetam for Residual Executive Dysfunction and "Brain Fog": A Naturalistic Case Report. Preprints. 2025.

- Alavi K, Shirazi E, Akbari M, et al. Effects of piracetam as an adjuvant therapy on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. 2021;15(2).

- Cheung N. Timing Is Everything: Why the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen Is Contraindicated in Young Children with Autism but Promising After Puberty. Preprints. 2025.

- Tang G, Gudsnuk K, Kuo SH, et al. Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits. Neuron. 2014;83(5):1131–1143.

- Faust TE, Gunner G, Schafer DP. Mechanisms governing activity-dependent synaptic pruning in the developing mammalian CNS. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2021;22(11):657–673.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).