Introduction

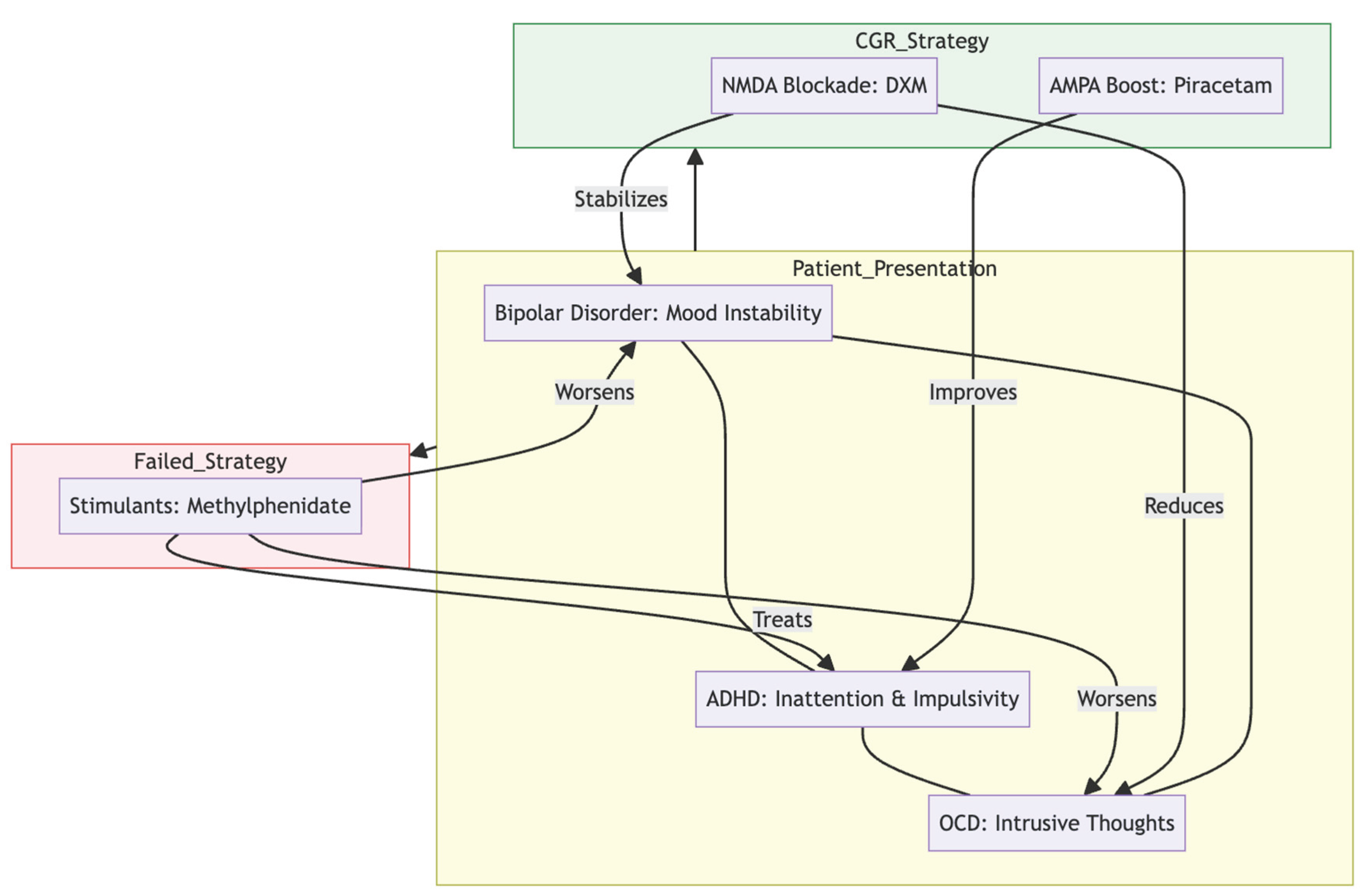

When bipolar disorder (BD) overlaps with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) the result is often a course that resists most standard treatments. Surveys place the lifetime frequency of OCD in bipolar populations between 15 % and 24 %, with still higher figures in bipolar I and in illnesses that begin in childhood or adolescence (1,2). Adding ADHD to the mix usually means greater mood lability, more admissions to hospital and a higher risk of suicide attempts than are seen in BD alone (3,4). The obsessive–compulsive content tends to be mood-linked: themes intensify during depression and commonly centre on aggression, sexuality or symmetry, a profile that differs from primary OCD (4). Pharmacotherapy brings its own hazards; high-dose selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors can precipitate mania or mixed states, while stimulants used for ADHD may trigger hypomanic switches or rapid cycling (5,3).

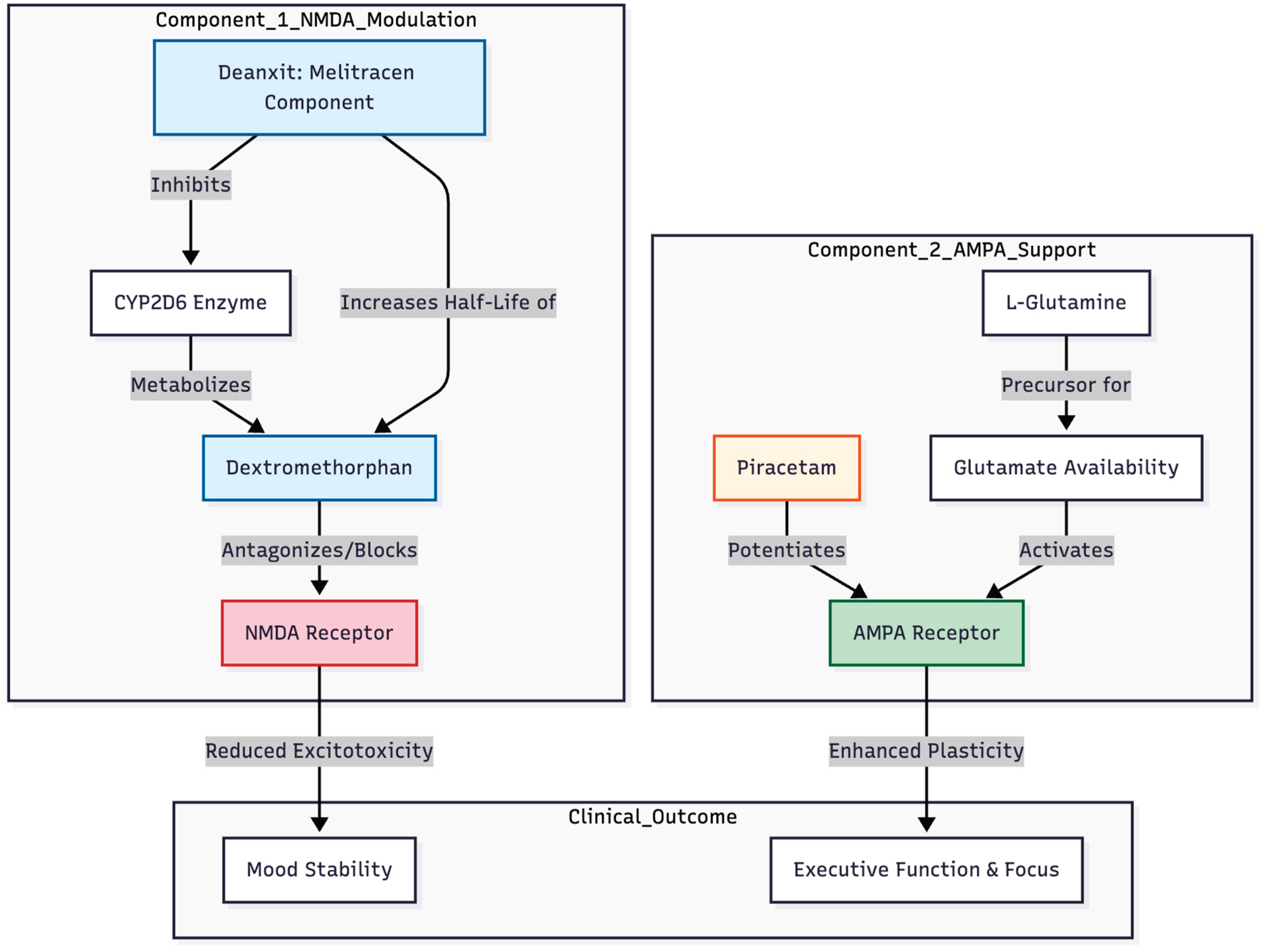

Rapid-acting glutamatergic treatments such as intravenous ketamine have produced robust benefits across treatment-resistant depression, bipolar depression, OCD and acute suicidality, with 50–70 % of patients improving within days (6,7). Practical hurdles, cost and dissociation, however, limit routine use. Attention has therefore turned to oral combinations that imitate ketamine's NMDA-to-AMPA plasticity cascade (8). One such approach, the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen (CGR), pairs dextromethorphan (an NMDA antagonist) with a CYP2D6 inhibitor to prolong its action, adds piracetam as an AMPA positive allosteric modulator and supplies L-glutamine to steady presynaptic glutamate release. Early series have described swift relief of depressive, obsessive, trauma-related and cognitive symptoms in both unipolar and bipolar settings (9,10,11).

Against this backdrop we report the course of a 31-year-old man carrying diagnoses of bipolar I disorder, mood-congruent obsessive–compulsive symptoms and lifelong ADHD. His illness had withstood conventional mood stabilisers, antipsychotics and venlafaxine, and a recent stimulant trial had pushed him toward hypomania. Introducing a modified CGR—using Deanxit (flupentixol/melitracen) as a mild, reversible CYP2D6 inhibitor—produced sustained gains in mood, ruminations, impulsivity and attention, and sharply reduced his dependence on methylphenidate.

Methods

This report describes the longitudinal care of a single patient who attended a private outpatient psychiatry clinic from July through December 2025. Prior to data extraction the patient signed a written consent form permitting anonymous use of all clinical information for scientific publication.

Symptom severity was followed prospectively with validated instruments. Depressive burden was rated on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and anxiety on the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7. At each consultation—scheduled roughly every two to four weeks—the psychiatrist carried out a structured clinical interview together with a full mental-state examination. When attention problems were especially salient, the Schulte Table grid was administered to obtain an objective measure of sustained concentration and processing speed. Possible hypomanic or manic shifts were tracked by applying DSM-5 criteria and by reviewing daily accounts of sleep duration, impulsive acts and spending patterns supplied by the patient.

Pharmacological changes were introduced gradually. During the first month after the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen was started, dose escalations were reviewed by telephone every one to two weeks. Blood pressure, pulse and weight were checked in the clinic, and comprehensive laboratory panels—including complete blood count, renal and hepatic indices, and serum valproate—were repeated at six- to eight-week intervals. All observations were entered contemporaneously into the electronic medical record.

Case Presentation

A 31-year-old man sought care for persistent mood instability, intrusive obsessive thoughts and lifelong problems with attention and impulsivity. His psychiatric history included bipolar disorder marked by hypomanic episodes—pressured ideation, impulsive buying sprees and a motor-vehicle accident caused by reckless driving—alternating with depressive phases characterised by anxiety, sleep fragmentation and social withdrawal. Since childhood he had struggled to sustain focus, performed below his intellectual ability at school and acted impulsively, all suggestive of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). He reported having visited other private psychiatrists back in 2021, given venlafaxine and valproate with limited effect.

July – August 2025: first outpatient course

At the initial consultation in July 2025 he scored 21 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and 19 on the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). The first treatment plan combined sodium valproate (Epilim Chrono) 500 mg daily, Deanxit (flupentixol 0.5 mg + melitracen 10 mg) one tablet daily, risperidone 0.5 mg, alprazolam as needed and lemborexant (Dayvigo) for sleep. By early August the mood indices had fallen modestly (PHQ-9 = 14, GAD-7 = 15), yet the patient remained functionally disabled by inattention, an inability to read for any length of time and persistent impulsivity. Wellbutrin XL (bupropion) 150 mg and pregabalin 50 mg were therefore added to the existing regimen.

August 2025: stimulant trial and early manic drift

Because the ADHD symptoms continued to dominate, bupropion was withdrawn in mid-August and methylphenidate (Ritalin LA) 10 mg daily was introduced on a background of Epilim Chrono 500 mg, aripiprazole 0.5 mg, clonazepam 0.5 mg and ongoing Deanxit. Schulte Table testing demonstrated excellent accuracy (97.08 %) but erratic processing speed, reinforcing the attentional diagnosis. Upon follow-up four weeks later, his sleep became fragmented and vivid dreaming appeared. At the same time, he also reported binge-eating episodes. All these symptoms hinted stimulant-induced mood elevation. Methylphenidate was therefore discontinued in mid-September.

September – November 2025: switch to the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen

To tackle resistant mood swings and cognitive "fog" without provoking mania, therapy pivoted to the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen (CGR). Deanxit served a dual purpose: antidepressant support and, via its melitracen component, CYP2D6 inhibition to prolong dextromethorphan exposure.

During late August dextromethorphan was started at 15 mg three times daily (45 mg total) and increased to 30 mg twice daily (60 mg total) by late September. In mid-September piracetam (Syntam) 600 mg daily was added; this was doubled to 600 mg twice daily by month's end. L-glutamine 1 000 mg daily joined the stack in late September to bolster glutamate availability. Concurrent mood-stabiliser adjustments included stepping Epilim Chrono up to 800 mg (500 mg + 300 mg) and titrating aripiprazole to 5 mg daily before tapering back to 2.5 mg once stability emerged.

Through October and November 2025 the patient maintained full CGR dosing—dextromethorphan 30 mg twice daily, piracetam 600 mg twice daily, L-glutamine 1 000 mg daily and Deanxit one tablet daily, together with Epilim Chrono 800 mg, aripiprazole 2.5 mg, pregabalin 75 mg and propranolol 20 mg. Anxiety scores fell sharply (GAD-7 = 8). He reported less irritability, stronger impulse control and newfound ease in crowded environments. Methylphenidate became an occasional, non-destabilising "as-needed" aid rather than a daily necessity.

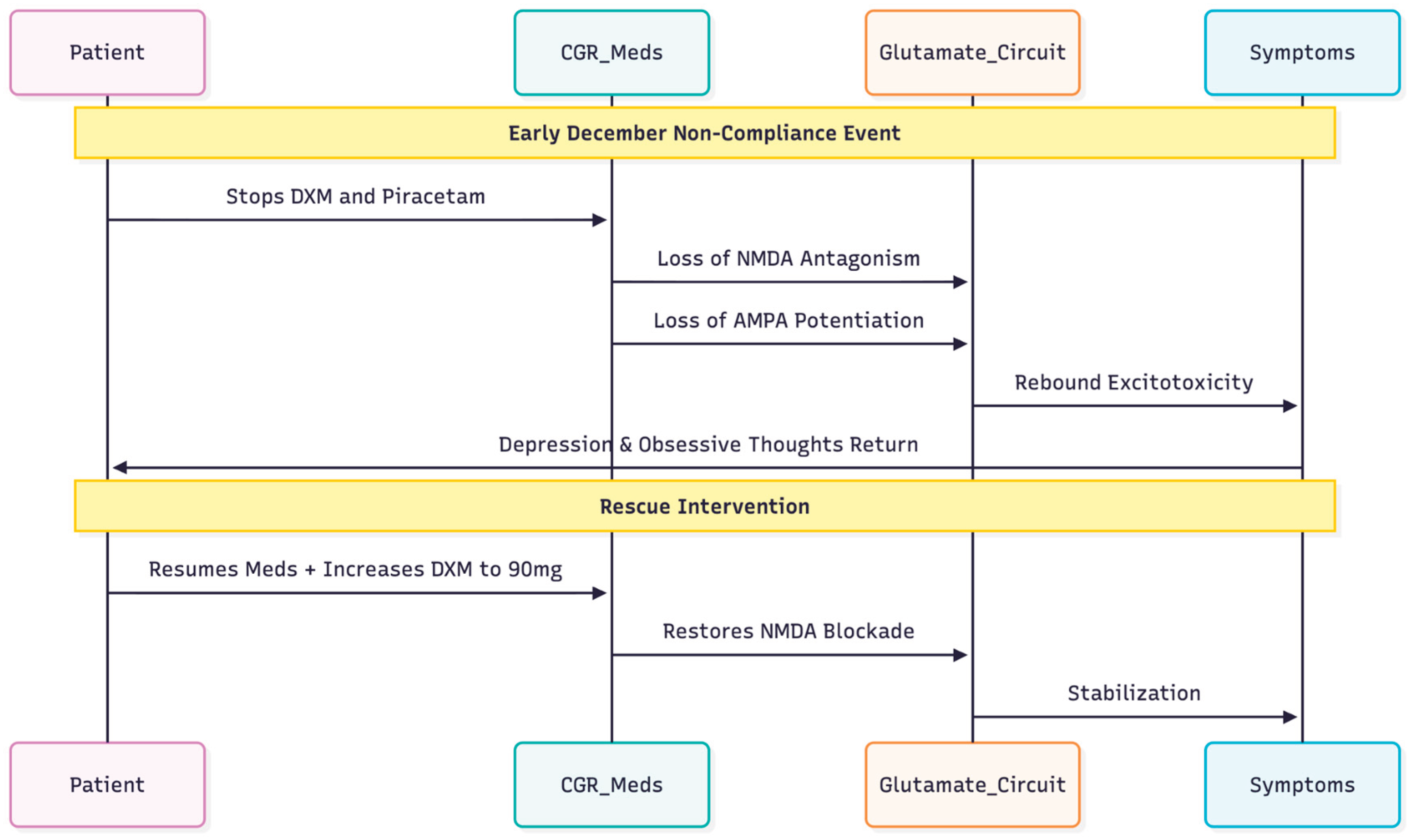

December 2025: relapse associated with non-compliance

The depressive symptoms and obsessive thoughts reemerged in early December (PHQ-9 = 15). The patient said that he had stopped taking both dextromethorphan and piracetam but was still taking the rest of his medications. The dose of Dextromethorphan was therefore raised to 90 mg per day (45 mg twice a day) to re-establish NMDA-antagonism (

Figure 1).

This chronological narrative underscores the capacity of the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen to stabilise a complex presentation encompassing bipolar disorder, OCD and ADHD, and highlights the swift recurrence of obsessive symptoms when NMDA blockade and AMPA potentiation are withdrawn.

Discussion

Managing the intersection of bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive symptoms and ADHD is notoriously tricky. Epidemiological work suggests that 15 – 24 % of people with bipolar disorder also satisfy criteria for OCD, the link being strongest in bipolar I and in those whose illness starts early (1,2). When ADHD is present as well, prescribing becomes still more complicated; stimulants remain the gold standard for attention but can tip a vulnerable patient into hypomania or mania (

Figure 2), as occurred when our patient's trial of methylphenidate led to broken sleep, vivid dreams and binge-eating (12,3,4).

Obsessive–compulsive phenomena in this "bipolar-OCD" subgroup typically intensify during depressive episodes and diminish during hypomanic states, rarely showing improvement with high-dose SSRIs alone (3,4). Genetic and imaging data that point in the same direction suggest that there is a shared orbitofrontal–striatal dysfunction that affects dopaminergic, serotonergic, and, most importantly, glutamatergic circuits (5,15).

By combining dextromethorphan's NMDA blockade with piracetam's AMPA potentiation (

Figure 3), it gets the fast-acting and procognitive effects of ketamine without the strong push of serotonin or norepinephrine, which is an important way to avoid a manic switch (8). In our patient, adding dextromethorphan (pharmacokinetically boosted by mild CYP2D6 inhibition from melitracen in Deanxit), piracetam and L-glutamine coincided with clear gains: lower depression and anxiety scores, fewer intrusive ruminations and a marked fall in impulsivity. His need for methylphenidate shrank to occasional use, implying that the regimen sharpened executive control, likely through an AMPA-dominated plasticity cascade (13,14).

When the glutamatergic agents were stopped, depressive affect and obsessive thoughts re-emerged despite continuing valproate, aripiprazole and Deanxit. The rapid relapse underscores how central the NMDA–AMPA axis was to his stability and mirrors pre-clinical observations that sustained AMPA throughput is essential for maintaining ketamine-class benefits (16,7) as well as early clinical series using similar oral stacks (10,11).

Choosing Deanxit as the CYP2D6 inhibitor proved prudent. Melitracen produces only transient, reversible inhibition, offering enough boost to dextromethorphan without the prolonged wash-out or "suicide" inhibition associated with paroxetine or fluoxetine—both riskier in bipolar illness (8). Low-dose tricyclic or tetracyclic agents may therefore be a pragmatic anchor when building the CGR for bipolar-OCD presentations.

Taken together, this report adds weight to the idea that a carefully titrated oral glutamatergic approach can tame depressive, obsessive and attentional symptoms in complex bipolar-spectrum cases, reduce reliance on stimulants and do so without provoking manic instability—so long as a reliable mood-stabiliser remains in place and CYP2D6 inhibition is kept mild and reversible.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Amerio, A.; Stubbs, B.; Odone, A.; et al. The prevalence and predictors of comorbid bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2015, 186, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferentinos, P.; Preti, A.; Veroniki, A.A.; et al. Comorbidity of obsessive-compulsive disorder in bipolar spectrum disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis of its prevalence. Journal of Affective Disorders 2020, 263, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Filippis, R.; Aguglia, A.; Costanza, A.; et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder as an epiphenomenon of comorbid bipolar disorder? An updated systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Prisco, M.; Tapoi, C.; Oliva, V.; et al. Clinical features in co-occuring obsessive-compulsive disorder and bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2024, 80, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amerio, A.; Costanza, A.; Aguglia, A. Differentiating comorbid bipolar disorder and OCD. Psychiatric Times. 2020. Available online: https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/differentiating-comorbid-bipolar-disorder-and-ocd.

- Berman, R.M.; Cappiello, A.; Anand, A.; et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biological Psychiatry 2000, 47, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanos, P.; Moaddel, R.; Morris, P.J.; et al. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature 2016, 533, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, N. DXM, CYP2D6-inhibiting antidepressants, piracetam, and glutamine: Proposing a ketamine-class antidepressant regimen with existing drugs. Preprints.org 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. An oral "ketamine-like" NMDA/AMPA modulation stack restores cognitive capacity in a young man with schizoaffective disorder—Case report. Preprints.org 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. Case series: Marked improvement in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive symptoms with over-the-counter glutamatergic augmentation in routine clinical practice. Preprint ID 186969; Preprints.org. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, N. Oral glutamatergic augmentation for trauma-related disorders with fluoxetine-/bupropion-potentiated dextromethorphan ± piracetam: A four-patient case series. Preprints.org 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Amerio, A.; Stubbs, B.; Odone, A.; et al. Bipolar I and II disorders; a systematic review and meta-analysis on differences in comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences 2016, 10, e3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Lee, B.; Liu, R.J.; et al. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science 2010, 329, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeng, S.; Zarate, C.A., Jr.; Du, J.; et al. Cellular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of ketamine: Role of AMPA receptors. Biological Psychiatry 2008, 63, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamidian, S.; Pourshahbaz, A.; Bozorgmehr, A.; et al. How obsessive-compulsive and bipolar disorders meet each other? An integrative gene-based enrichment approach. Annals of General Psychiatry 2020, 19, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koike, H.; Iijima, M.; Chaki, S. Involvement of AMPA receptor in both the rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects of ketamine in animal models. Behavioural Brain Research 2011, 224, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).