1. Introduction

The ongoing evolution toward Industry 4.0 has driven the convergence of physical processes with advanced digital technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), edge computing, artificial intelligence, and 5G/6G-enabled connectivity [1-3]. This transformation has enabled the deployment of cyber-physical systems (CPS) across a wide range of critical infrastructures [

4], including smart grids [5-7], vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) networks [8-10], intelligent manufacturing plants [

11], and energy-aware buildings [

12]. These systems are increasingly reliant on real-time data exchange, automated decision-making, and distributed sensing to ensure resilience, efficiency, and autonomy. However, the same digital backbone that empowers these infrastructures also makes them vulnerable to cyber threats that can propagate through interconnected layers and compromise both safety and operational continuity [13-15].

One particularly sensitive domain within this ecosystem is smart water infrastructure, which encompasses water treatment, purification, distribution, and quality monitoring processes [

16]. The integration of digital control systems, networked sensors, and supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) platforms has improved process optimization and resource efficiency [17-19]. Yet, these enhancements come with significant security implications. As water systems become increasingly dependent on CPS architectures, they face a growing risk of cyberattacks that can manipulate sensor readings, disrupt control logic, or compromise service availability [

20]. The complex interplay between physical dynamics and cyber control makes these infrastructures especially susceptible to subtle and persistent threats, highlighting the urgent need for advanced and adaptive intrusion detection capabilities. One of the most concerning threats is false data injection (FDI), where attackers manipulate sensor measurements or control signals to mislead monitoring systems, degrade decision-making, or cause physical damage, often without immediate detection [

21].

In recent years, the rapid advancements in machine learning (ML) and, more specifically, deep learning (DL) have introduced powerful tools to address the growing security challenges of cyber-physical and water distribution systems [

22]. Unlike traditional statistical or rule-based detection approaches, DL models can automatically learn complex, nonlinear patterns from high-dimensional sensor and network data, making them particularly effective in identifying subtle or previously unseen anomalies. Reinforcement learning (RL) further extends these capabilities by enabling adaptive decision-making through continuous interaction with dynamic environments, while deep reinforcement learning (DRL) integrates the representational strength of neural networks with the sequential optimization ability of RL. These characteristics are highly suitable for smart water infrastructures, where attack patterns may evolve over time and detection mechanisms must adapt to changing operational conditions. Building on this, transformer architectures have emerged as a breakthrough in sequence modeling, originally in natural language processing, but now increasingly applied to time-series and multivariate sensor data [

23]. Their self-attention mechanism allows models to capture both short- and long-term dependencies without the limitations of recurrent structures, enabling superior performance in scenarios where temporal and spatial correlations play a critical role. When applied to water distribution systems, transformers and DRL frameworks can collaboratively extract hidden dependencies across heterogeneous data streams, adapt detection strategies in real time, and enhance resilience against sophisticated cyber-physical attacks such as false data injection [22-24].

1.1. Related Works

Xu et al. [

22] proposed a novel anomaly detection method called TDRT, which integrates a three-dimensional ResNet with a transformer to address limitations of prior approaches in capturing temporal–spatial dependencies. Their framework enables automatic learning of multi-dimensional features while leveraging the transformer’s ability to capture long-term correlations in multivariate time series. The model was validated on three widely used industrial control datasets (SWaT, WADI, and BATADAL) and benchmarked against five state-of-the-art algorithms. Experimental results demonstrated that TDRT consistently achieved an average F1-score above 0.98 and a recall of 0.98, significantly outperforming competing methods. These results highlight the effectiveness of combining 3D convolutional structures with transformer encoders for enhancing anomaly detection accuracy in complex temporal–spatial data.

Wang et al. [

23] addressed the limitations of existing GNN-based anomaly detection methods in industrial control systems, where topological graphs often miss hidden associations between devices and fully connected graphs introduce redundancy and high computational overhead. To overcome this, they proposed the local graph spatial analyzer (LGSA), which introduces a decoupled edge tuning mechanism to balance connectivity by removing redundant links while preserving core contextual semantics. Unlike conventional approaches that focus on system-wide detection, LGSA performs fine-grained device-level anomaly identification, thereby improving both scalability and detection precision. Evaluations on five benchmark ICS datasets (SWaT, WADI, CISS, BATADAL, and PCP) demonstrated that LGSA achieved up to a 17.32% improvement in AUROC over baselines, while also reducing training and testing time by 5.57% and 7.21%, respectively. These results highlight that optimizing graph construction through selective edge adjustment enables both enhanced detection accuracy and greater runtime efficiency in industrial anomaly detection.

Lachure and Doriya [

24] proposed a hybrid anomaly detection framework that integrates hierarchical clustering with deep learning to improve the security of industrial control systems. Their approach addresses the challenges faced by conventional methods in handling complex, high-dimensional data and detecting subtle anomalies. By combining clustering’s structural grouping capability with deep models’ representation power, the method aims to enhance detection accuracy and robustness. The framework was validated on two benchmark datasets, WADI and BATADAL, which include diverse attack and normal operation scenarios. Experimental results showed strong performance on BATADAL, achieving recall, precision, and F1-scores of 0.91, 0.915, and 0.915, respectively, while on WADI the model reached recall of 0.70, precision of 0.81, and F1-score of 0.67. These findings demonstrate that the hybrid deep hierarchical clustering approach can improve anomaly detection in ICSs, particularly in environments with complex and varied data distributions.

Luo et al. [

25] introduced STMBAD, a spatio-temporal multimodal behavior anomaly detector tailored for industrial control systems, to counter stealthy and persistent cyberattacks that often bypass threshold-based methods. Their framework leverages multimodal ICS data and models both temporal evolution and spatial correlations using attention mechanisms, enabling a fine-grained understanding of complex system behaviors. To address issues of heterogeneous data types and unsynchronized time series, STMBAD embeds each modality separately into variate tokens and applies a feedforward network to capture cross-modal dependencies. Additionally, the authors proposed an adaptive detection strategy that integrates global and local thresholds to reduce errors caused by static global rules. Experimental evaluations demonstrated that STMBAD surpassed baseline approaches, achieving the highest F1-score of 95%, confirming its effectiveness in detecting stealthy attacks in ICS environments.

Xu et al. [

26] explored the cybersecurity risks of adversarial sample attacks in industrial control systems and proposed a dual approach for both generating and defending against such attacks. They introduced a gated recurrent unit (GRU)-based framework capable of learning complex dependencies among sensor features, which was then used to create adversarial samples by injecting perturbations that preserved realistic data constraints. For defense, the authors developed a VAE feature weight (VAE-FW) method that detects anomalies without requiring prior knowledge of adversarial samples. By balancing prediction errors across features, the defense mechanism prevents poorly predicted attributes from dominating anomaly scores, thereby improving robustness. Experimental evaluations on three real-world sensor datasets demonstrated that the proposed framework not only enhanced attack efficiency but also provided superior defense performance, with VAE-FW achieving up to a 28.8% improvement in area under the curve (AUC) compared to baseline detection methods. These findings highlight the importance of integrating adversarial learning and robust feature-weighted defenses in ICS security.

Lachure and Doriya [

27] proposed ESML, a hyper-parameter-tuned stacking ensemble framework aimed at detecting anomaly attacks in critical infrastructures, with a focus on water distribution systems. Their approach integrates multiple machine learning classifiers through stacked generalization while optimizing hyper-parameters to maximize performance. The framework was evaluated on the WADI and BATADAL datasets, both widely used for benchmarking cyber-physical attack detection in WDS. Compared to traditional classifiers such as k-nearest neighbors, decision trees, and naïve Bayes, the ESML method demonstrated superior accuracy, achieving 99.96% on WADI and 96.93% on BATADAL. These results indicate that the combination of ensemble stacking and hyper-parameter tuning can significantly enhance anomaly detection capabilities, ensuring higher reliability in protecting water infrastructure against cyber-physical attacks.

Shuaiyi et al. [

28] tackled the challenge of detecting highly covert anomalies in industrial control systems that stem from complex contextual semantics among heterogeneous devices. To address this, they proposed the graph sample-and-integrate network (GSIN), a GNN-based framework that extends beyond conventional local aggregation by integrating both local and global contextual features of ICS data. The model performs node-level anomaly detection by combining localized node awareness with global process-oriented properties through pooling strategies. Experimental evaluations on multiple benchmark ICS datasets with various integration configurations showed that GSIN consistently outperformed representative baselines, achieving higher F1-scores and AUPRC values while maintaining superior runtime efficiency. These results demonstrated the effectiveness of advanced feature integration in enhancing both detection accuracy and computational scalability for ICS anomaly detection.

Li et al. [

29] addressed the challenge of overfitting and limited generalization in anomaly forecasting for heterogeneous industrial edge devices within IIoT environments. They proposed MuLDOM, a framework combining a multibranch long short-term memory (LSTM) with a novel differential overfitting mitigation algorithm to enhance robust anomaly detection and forecasting. The design enables adaptive feature extraction and denoising of multivariate time series while controlling model overfitting through differential mitigation, applied for the first time in this context. In addition, an online prediction scoring mechanism was incorporated to improve quantitative estimation of spatio-temporal patterns in IED operations. Experimental evaluations across four publicly available industrial datasets demonstrated that MuLDOM outperformed nine state-of-the-art baselines, confirming its superior accuracy and robustness. The results highlight MuLDOM’s promise as a practical and scalable solution for real-time monitoring and forecasting in IIoT applications.

Xu et al. [

30] proposed LATTICE, a digital twin–based anomaly detection framework for cyber-physical systems that incorporates curriculum learning to address the challenges of increasing CPS complexity and diverse data difficulty. Building on their earlier ATTAIN model, LATTICE assigns difficulty scores to samples and employs a training scheduler that gradually feeds data from easy to difficult, mimicking human learning processes. This design allows the model to leverage both historical and real-time CPS data while improving learning efficiency and robustness. The approach was validated on five real-world CPS testbeds and benchmarked against ATTAIN and two other state-of-the-art detectors. Results showed that LATTICE consistently outperformed all baselines, improving F1-scores by 0.906% to 2.367%, while also reducing ATTAIN’s training time by an average of 4.2% without increasing detection delays. These findings demonstrate that combining digital twins with curriculum learning enhances both accuracy and efficiency in CPS anomaly detection.

Lachure and Doriya [

31] presented a hybrid meta-heuristic framework to secure water distribution systems against cyber-physical attacks, integrating advanced chicken swarm optimization (CSO) with particle swarm optimization for feature selection in high-dimensional CPS data. By identifying critical features, the approach enhances both detection accuracy and system robustness. For classification, a robust voting ensemble was designed, combining support vector machines (SVM), decision trees, random forests, and XGBoost to ensure reliable detection performance. The framework was validated on the WADI and BATADAL datasets, achieving near-perfect detection rates, including 100% accuracy and an F1-score of 0.9981 on WADI, as well as an F1-score of 0.9888 and recall of 0.99 on BATADAL. The low false positive ratios across both datasets further confirmed its reliability. These results highlight that the combination of hybrid feature selection with ensemble learning provides a scalable and highly accurate defense mechanism for WDS security against emerging cyber-physical threats.

1.2. Paper Motivation, Contribution, and Organization

The increasing digitalization of industrial infrastructures, particularly in smart water distribution systems, has heightened the urgency for robust anomaly detection frameworks capable of addressing subtle and persistent threats. While recent research has advanced significantly, most existing approaches still face notable limitations that prevent them from fully safeguarding critical infrastructures. Convolutional and recurrent neural networks, although effective in sequence modeling, often suffer from overfitting and struggle to capture long-range dependencies in multivariate time-series data, especially under high-dimensional and noisy sensor environments. Likewise, classical ML ensembles improve generalization to some extent, but their performance is highly dependent on manual hyper-parameter tuning and they lack the adaptability required for evolving cyber-physical attack patterns. Graph-based methods have also gained traction in anomaly detection, leveraging relational structures among devices. However, as highlighted in recent works, topologically constrained graphs often miss latent associations, while fully connected graphs create redundancy and incur heavy computational overhead. Similarly, clustering-based hybrids and digital twin frameworks provide improved modeling of system behaviors but are limited in scalability and still rely on static assumptions that restrict their responsiveness to dynamic attack scenarios. Overall, the review of recent approaches underscores that the key challenges remain: balancing accuracy with computational efficiency, capturing both local and global temporal-spatial dependencies, and adapting detection strategies in real time to evolving threats.

To address these challenges, there is a strong motivation to adopt advanced DL architectures, such as transformers, which can exploit self-attention mechanisms to model long- and short-term dependencies across heterogeneous sensor streams without the bottlenecks of recurrent structures. Transformers have demonstrated remarkable success in extracting multi-scale temporal and contextual correlations, making them well-suited for anomaly detection in cyber-physical environments. However, their performance is highly sensitive to hyper-parameter settings, and in complex domains such as ICS and WDS, inappropriate configurations can significantly degrade both accuracy and runtime efficiency. At the same time, DRL offers the potential to introduce adaptivity into anomaly detection pipelines by enabling learning-based decision policies that dynamically respond to variations in data patterns and attack scenarios. Yet, DRL models are notoriously dependent on careful calibration of hyper-parameters, which directly affects convergence, stability, and generalization performance. Conventional optimization strategies such as grid search or classical meta-heuristics have proven insufficient in consistently balancing exploration and exploitation across such a large hyper-parameter space. This motivates the integration of an improved optimization scheme.

In this context, an improved grey wolf optimizer (IGWO) can play a vital role by introducing a new balancing mechanism between exploration and exploitation phases, thereby ensuring more reliable convergence toward optimal hyper-parameter configurations. By incorporating IGWO into the training pipeline of transformer-based DRL, it becomes possible to unify three complementary capabilities: robust temporal-spatial feature extraction (via transformers), adaptive policy learning (via DRL), and effective hyper-parameter optimization (via IGWO). This synergy directly addresses the gaps identified in recent studies and forms the foundation of our proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL framework for anomaly detection in smart water infrastructures. Based on the identified research gaps and the objectives of this study, the main contributions of our work can be summarized as follows:

Problem-driven architecture design: We address the pressing challenge of anomaly detection in cyber-physical WDS that are highly vulnerable to stealthy and persistent cyberattacks. To this end, we propose a unified detection framework that integrates advanced DL and optimization techniques tailored to capture both temporal–spatial dependencies and evolving attack behaviors.

Novel hybrid architecture: We introduce the Evo-Transformer-DRL model, which seamlessly combines (i) a transformer encoder for robust multivariate temporal–spatial feature extraction, (ii) a (DRL agent for adaptive anomaly detection and decision-making, and (iii) an IGWO for hyper-parameter tuning. This integration provides a balanced solution for both detection accuracy and computational efficiency.

IGWO: Building upon the classical GWO, we incorporate an additional balancing wolf φ that dynamically regulates exploration and exploitation during the optimization process. This extension improves convergence reliability and prevents premature stagnation, ensuring more stable hyper-parameter optimization for deep models in high-dimensional search spaces.

Comprehensive benchmarking on critical datasets: We conduct extensive experiments using three widely adopted industrial control benchmarks (secure water treatment (SWAT), water distribution (WADI), and battle of the attack detection algorithms (BATADAL)) which collectively cover diverse attack and operational conditions in water infrastructures. The performance of the proposed method is rigorously compared against multiple strong baselines, including bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT), LSTM, convolutional neural network (CNN), and SVM.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the proposed methodology in detail, including the transformer encoder, the DRL component, and the IGWO with its mathematical formulation.

Section 3 reports the simulation environment, implementation details, parameter settings, evaluation metrics, and experimental results with comparisons across baseline algorithms.

Section 4 provides the concluding remarks and highlights possible directions for future research.

2. Materials and Proposed Methods

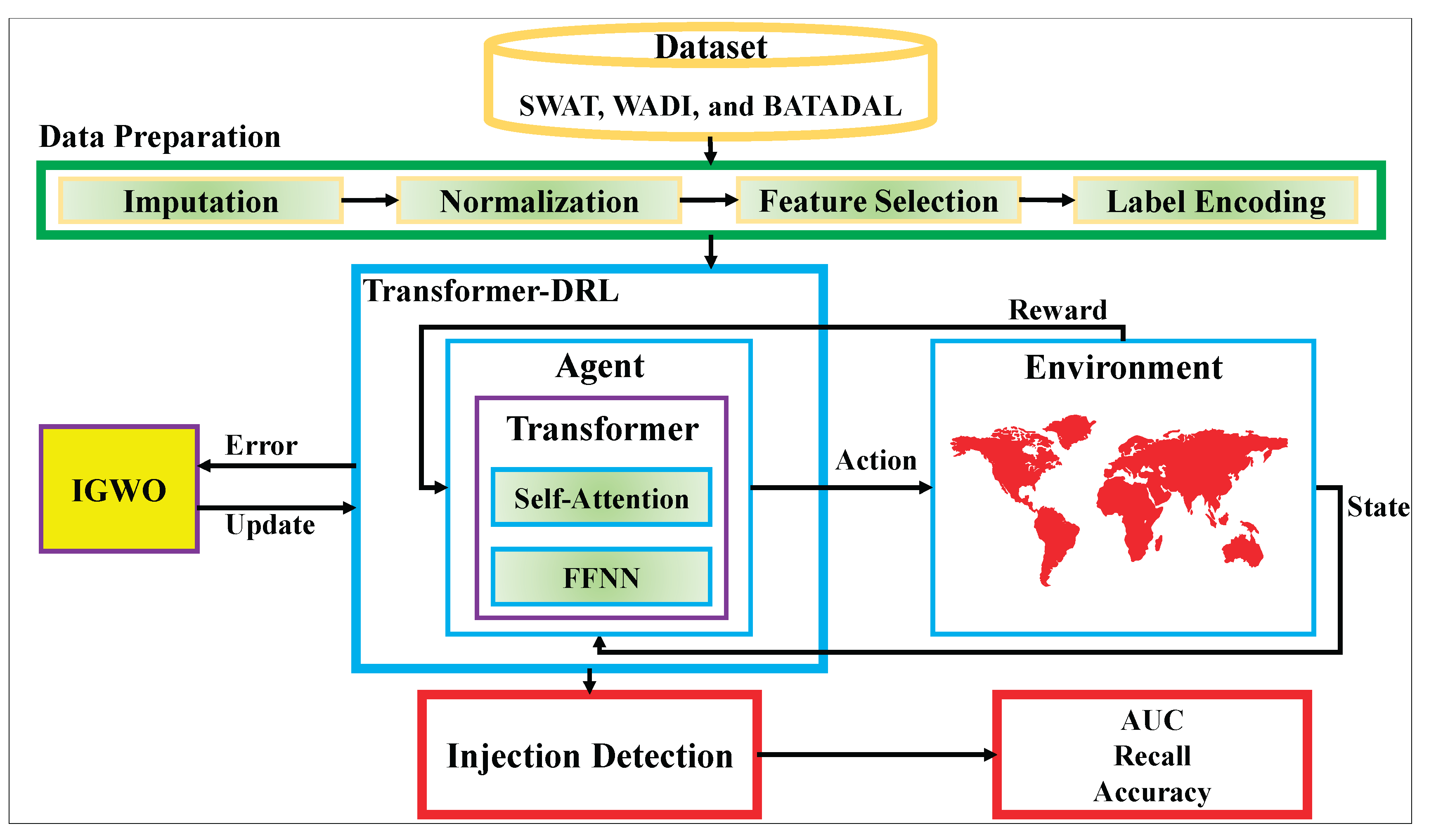

To address the complex challenge of FDI detection in Industry 4.0 water infrastructures, we design a hybrid learning pipeline that integrates data preprocessing, intelligent feature learning, adaptive decision-making, and optimization. The overall workflow of the proposed solution is illustrated in Fig. 1, which demonstrates the flow of information from raw datasets to injection detection and final performance evaluation. As depicted in the figure, the methodology consists of two major stages: data preparation and the Evo-Transformer-DRL framework. In the first stage, datasets collected from three benchmark cyber-physical testbeds (SWAT, WADI, and BATADAL) undergo a series of preprocessing operations including missing value imputation, normalization, feature selection, and label encoding. These steps ensure that the raw data is clean, scaled, and semantically structured for downstream learning. The processed data is then fed into the core framework, which integrates three key components: a Transformer encoder, a DRL agent, and an IGWO optimizer. Within this architecture, the Transformer module extracts temporal and contextual patterns from sequential input features, which are then used by the DRL agent to learn optimal policies for attack classification under dynamic data conditions.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed model for false data injection detection.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed model for false data injection detection.

To enhance generalization and convergence, the proposed IGWO model is employed to optimize the hyper-parameters of both the Transformer and DRL modules. This optimization step ensures that the agent maintains a balanced performance trade-off between detection quality and computational overhead. During training and testing, the agent interacts with a simulated environment that reflects the underlying dynamics of the industrial water systems. The agent receives a state representation based on transformed input features and returns an action indicating the likelihood of FDI presence. Based on the outcome, a reward is generated, guiding the learning process. Finally, the trained model is evaluated through an injection detection module using three performance metrics (accuracy, recall, and AUC) to assess its robustness across datasets. This closed-loop framework ensures end-to-end adaptability, making it suitable for real-world Industry 4.0 deployments with evolving threat landscapes. The details of each stage in this pipeline are thoroughly described in the following subsections.

2.1. Dataset

In this subsection, we introduce the three benchmark datasets which are widely adopted in the research community for evaluating intrusion and anomaly detection methods in smart water infrastructures. These datasets cover diverse system behaviors, attack scenarios, and operational complexities. Following the dataset descriptions, we also explain the data preparation steps performed prior to model training. The SWAT dataset was collected from a scaled-down but functionally complete water treatment testbed located at the Singapore University of Technology and Design. The testbed replicates a realistic six-stage water treatment process, comprising raw water intake, chemical dosing, filtration, and backwashing, among others. Each stage is equipped with industrial-grade programmable logic controllers (PLCs), sensors (e.g., flow meters, pressure transducers, level sensors), and actuators (e.g., pumps, valves), and is controlled by SCADA software, thereby providing a cyber-physical environment that closely mirrors real industrial setups [22-24].

The dataset includes more than 11 days of operational data, consisting of seven days of normal behavior followed by four days of attack scenarios. The data is captured at 1-second intervals and includes 51 features, such as flow rates, water levels, pump and valve statuses, conductivity, and pressure readings across the six stages (P1–P6). Each record is labeled either as normal or attack, and the attack logs are well documented with timestamps and descriptions. The attacks span a wide variety, including FDI, command injection, denial-of-service (DoS), man-in-the-middle (MitM), and sensor spoofing. These attacks are injected using both internal and external vectors, simulating insider and outsider threats. What makes SWAT particularly valuable is its fine-grained resolution and detailed control logic, enabling the evaluation of anomaly detection models on real-time, multivariate sensor-actuator interactions. Due to its controlled nature, ground truth labeling is accurate, and the system behavior under both benign and malicious conditions is well understood. This makes it ideal for developing and validating classification models focused on binary detection of cyberattacks in treatment-oriented water systems [22, 23].

The WADI dataset was constructed to simulate a large-scale municipal water distribution system, capturing the flow of treated water from reservoirs to consumption points. Developed using a combination of real industrial control equipment and software simulation, the WADI testbed is more complex than SWAT in terms of network topology, data dimensionality, and physical interconnectivity. It reflects a full water distribution system with various storage tanks, pumps, valves, and pipelines, controlled by multiple PLCs under a central SCADA system. WADI consists of 16 days of data, including 14 days of normal operation and 2 days of attacks. The sampling frequency is one record every 1 second, and each sample includes 123 features, such as sensor measurements (e.g., pressure, flow, conductivity, tank levels) and actuator states (e.g., valve open/close status, pump on/off status). The dataset captures a variety of attack types, including multi-point FDI, DoS, actuator state flipping, and unauthorized command injections. The attacks are launched both via network interfaces and physical access to actuators, mimicking realistic insider and outsider adversarial behaviors. Labels are provided in a binary format (normal vs. attack), and detailed attack timelines are published alongside the dataset. Compared to SWAT, WADI introduces higher levels of noise, feature redundancy, and temporal dependencies, requiring robust detection mechanisms capable of learning from high-dimensional and highly correlated time-series data. Moreover, its size and heterogeneity make it suitable for evaluating models under scalability and generalization constraints [22-24].

BATADAL is a simulation-based dataset developed for a public challenge aimed at advancing anomaly detection in critical water infrastructure. Unlike SWAT and WADI, which rely on physical testbeds, BATADAL uses the EPANET hydraulic simulation engine to model a city-scale water distribution network. The dataset is generated from SCADA log emulations under varying operational conditions, including consumer demand profiles, pump schedules, and random fluctuations. The simulation environment includes a wide network of pipes, junctions, storage tanks, and pumps, and reproduces both nominal and malicious system behavior. The BATADAL dataset includes six scenarios with different attack configurations and durations. Data is sampled at 1-minute intervals, and each record includes 43 features, such as flow rate, tank water level, pressure readings, and actuator states (pump status, valve positions). The attacks are designed to mimic realistic and stealthy threats, such as gradual FDI, parameter manipulation, leak simulations, and demand distortion. Each scenario provides a log of attack windows and types, allowing supervised or semi-supervised model training. One unique advantage of BATADAL is its high stochastic variability, resulting from randomized water demand patterns and synthetic noise injected into sensor measurements. These characteristics make it especially challenging and useful for testing model robustness against uncertainty and unseen behaviors. Although simulated, BATADAL is widely accepted in the community due to its complexity and scale, and it complements SWAT and WADI by covering different aspects of smart water infrastructure [22-24].

To ensure data quality and compatibility with the proposed learning framework, four essential preprocessing steps are applied to all three datasets: imputation, normalization, feature selection, and label encoding. These operations collectively improve the consistency, efficiency, and discriminative power of the input data, which is crucial for training a high-performance detection model. First, missing values are addressed through imputation strategies to prevent disruptions in the temporal continuity of sensor readings. Gaps in the data (caused by sensor faults, communication issues, or logging errors) are handled using a combination of forward-fill, backward-fill, and linear interpolation, depending on the nature and length of the missing sequence. This step is critical to maintain a coherent input stream for time-series modeling and to avoid introducing learning artifacts. Once the data is complete, all continuous features are normalized to a common numerical range. Due to the variety of measurement units (e.g., liters per second, kilopascals, microsiemens), normalization is required to eliminate scale-related bias and to stabilize gradient-based learning. A min-max scaling technique is adopted to rescale values between 0 and 1, preserving the relative dynamics of each signal while enabling effective integration into the Transformer and DRL architectures.

After normalization, we reduce the input dimensionality by selecting a subset of relevant features. High-dimensional datasets such as WADI often include redundant or low-variance variables that do not contribute to anomaly discrimination. By applying statistical filtering and leveraging domain expertise, we retain only those features that exhibit strong temporal variability or are known to be directly affected by attacks. This not only improves computational efficiency but also helps prevent overfitting during model training. Finally, categorical output labels are transformed into binary numerical codes to facilitate supervised classification. All samples labeled as “Normal” are encoded as 0, while any form of malicious behavior (regardless of the attack type) is encoded as 1. This binarization ensures consistency across the datasets and aligns with the output format expected by the classification layer in our proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL framework.

2.2. RL

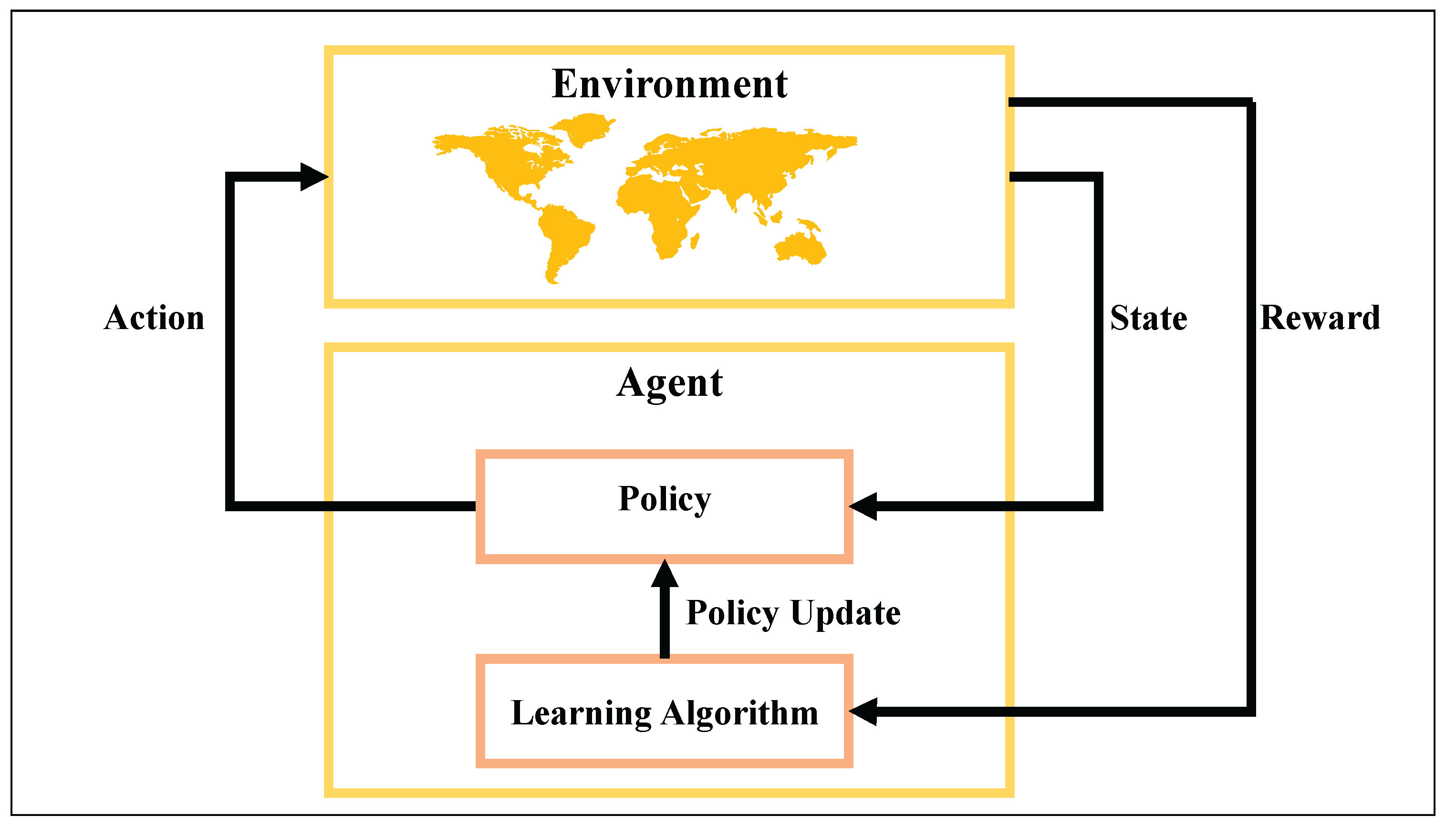

RL is a goal-oriented learning framework in which an agent learns to make sequential decisions by interacting with an environment and receiving evaluative feedback in the form of rewards. Unlike supervised learning, RL does not rely on labeled input–output pairs; instead, it enables autonomous learning through trial and error [

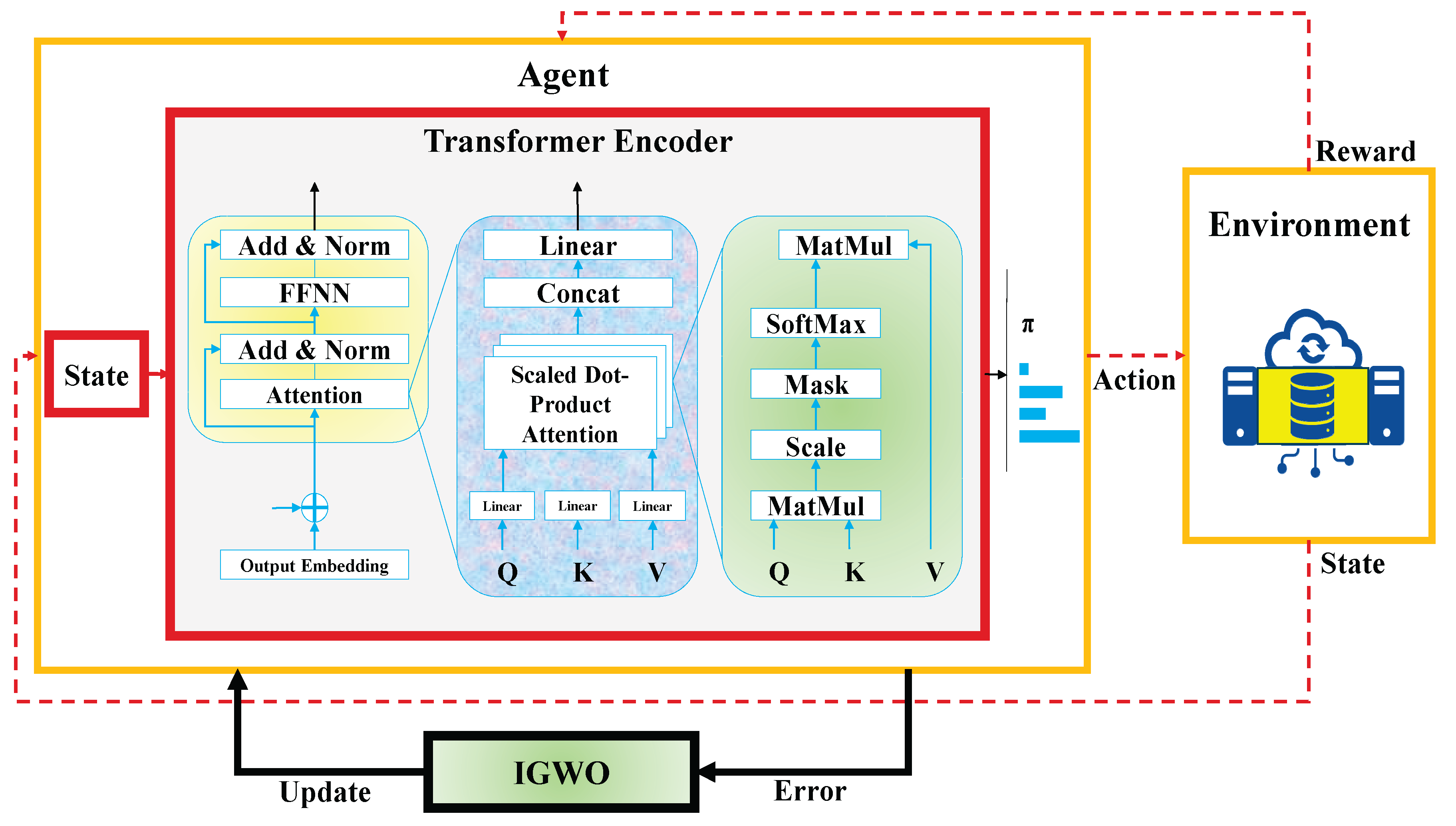

32]. This capability makes RL particularly advantageous for dynamic and partially observable environments, where system responses may be stochastic, delayed, or incomplete. Among its key strengths are adaptability, scalability, and the ability to optimize long-term cumulative performance in complex, high-dimensional state spaces. In the context of cybersecurity and anomaly detection RL offers unique advantages. FDI scenarios involve evolving attack vectors, uncertain feedback, and time-sensitive responses. Traditional static models may fail to detect such patterns unless explicitly trained on similar attacks. In contrast, RL-based methods can adapt to changing threat landscapes by continuously refining detection strategies in response to observed behavior and delayed outcomes. This real-time adaptability makes RL highly suitable for safeguarding cyber-physical systems operating under uncertain conditions. Fig. 2 depicts the generic architecture of an RL-based decision-making loop. The agent receives a state from the environment and selects an action according to its policy. This action influences the environment, which responds with a new state and a scalar reward. The agent uses this feedback to update its policy via a learning algorithm, gradually improving its decision-making process over successive interactions. This cycle continues until an optimal policy is learned that maximizes the agent’s long-term performance [

33].

Figure 2.

Interaction loop between the agent and environment in a RL framework.

Figure 2.

Interaction loop between the agent and environment in a RL framework.

The agent’s objective is to maximize the cumulative future reward, denoted by the return

. As shown in Eq. (1), this return is defined as the infinite sum of discounted future rewards [

34]:

where

is the cumulative return at time step

;

is the reward received

steps after time

; and

is the discount factor that controls the influence of future rewards, with

.

To evaluate how desirable it is to be in a certain state, the value function

is defined in Eq. (2) as the expected return when starting from state

and following a policy

:

where

is the expected return from state

under policy

;

denotes the expectation over all possible future trajectories.

This function quantifies the long-term benefit of being in a given state under a specific policy. To more precisely estimate the quality of individual actions in each state, the action-value function

is introduced in Eq. (3):

where

is the expected return for taking action

in state

and then following policy

;

is the current state;

is the selected action.

A commonly used update rule in RL is the Q-learning update, which adjusts the current estimate of the action-value function based on observed transitions. This is defined in Eq. (4) as:

where

is the current estimate of the action-value function;

is the learning rate controlling how much new information overrides old estimates;

is the immediate reward received after action

;

is the next state;

is the maximum estimated return achievable from state

. This iterative update enables the agent to learn optimal policies even in the absence of a model of the environment [

35].

2.3. Transformer

The transformer encoder has rapidly become a cornerstone in modern sequence modeling. Unlike recurrent or convolutional architectures, which struggle with capturing long-range dependencies and suffer from vanishing gradients or fixed receptive fields, the transformer leverages self-attention to directly model contextual relationships across entire sequences [

36]. This innovation not only accelerates training by enabling parallelization but also significantly enhances the capacity to extract meaningful temporal and semantic dependencies. For anomaly detection and cybersecurity tasks such as FDI detection, this adaptability is crucial since attacks often manifest as subtle, time-dependent perturbations embedded within multivariate sensor data. By relying on attention mechanisms rather than sequential recurrence, the transformer encoder ensures efficient learning from diverse attack scenarios, offering robustness against heterogeneous and evolving Industry 4.0 environments.

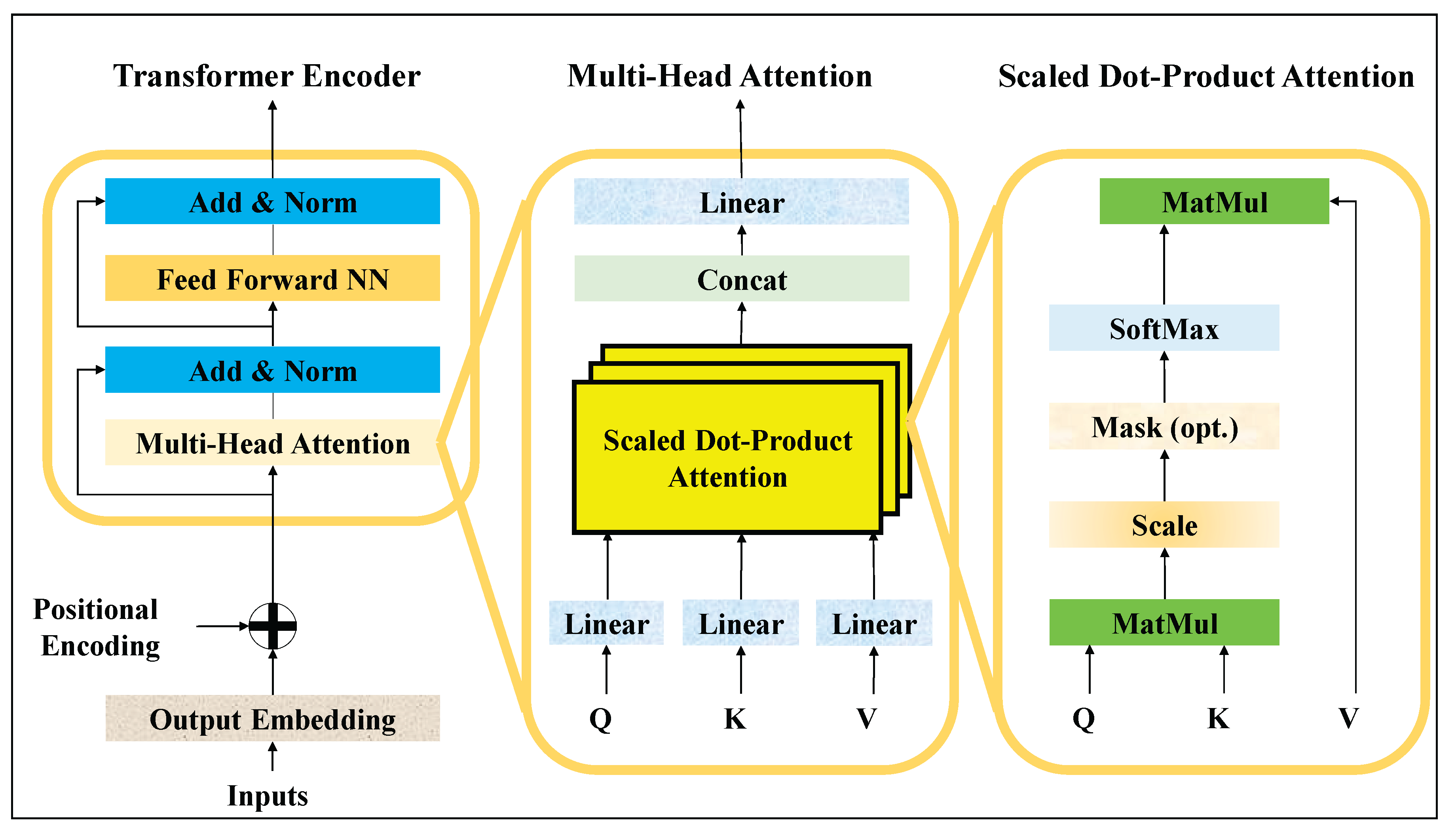

Over time, the transformer’s advantages (scalability, interpretability, and superior generalization) have positioned it as a preferred choice across domains including natural language processing, computer vision, and increasingly, cyber-physical security. In the context of Industry 4.0 water infrastructures, where continuous monitoring of high-dimensional signals is required, transformers offer the ability to capture both short-term fluctuations and long-range correlations that characterize complex system dynamics. This is especially beneficial for FDI detection, where stealthy manipulations might span multiple time steps and impact interrelated variables. By leveraging multi-head self-attention, the transformer encoder provides a mechanism to jointly weigh different aspects of input features, enabling robust identification of anomalous patterns while minimizing false alarms. The structure of the transformer encoder is depicted in Fig. 3, which illustrates its hierarchical composition [

37].

Figure 3.

The transformer encoder architecture.

Figure 3.

The transformer encoder architecture.

At the input stage, raw feature embeddings are augmented with positional encodings to preserve sequential ordering. These enriched embeddings are then fed into stacked encoder blocks, each comprising two key sublayers: a multi-head self-attention mechanism and a feed-forward neural network. Surrounding these sublayers are residual connections and layer normalization, which stabilize training and mitigate vanishing gradient issues. The output from successive encoder layers thus represents increasingly abstract and context-aware representations of the input data, enabling accurate classification of normal versus attack states in smart water systems. Within Fig. 3, the inner workings of the multi-head attention mechanism are further detailed. The process begins with the projection of inputs into three distinct vectors: queries, keys, and values. Scaled dot-product attention computes pairwise interactions between queries and keys, scaling them to avoid dominance from large values, and applies a softmax function to derive attention weights. These weights are subsequently used to aggregate value vectors, resulting in context-sensitive representations. Multiple such attention heads operate in parallel, capturing complementary aspects of dependencies, before being concatenated and passed through linear transformations. This enriched representation then flows into the feed-forward network, which applies non-linear transformations for further abstraction, followed by normalization and residual connections to ensure information preservation across layers [

38].

In continuation, the mathematical formulation of these components is presented. Eqs. (5) and (6) describe the sinusoidal positional encoding mechanism, which injects sequence order information into the model. This encoding ensures that the transformer can distinguish the relative positions of tokens, allowing it to model temporal dependencies effectively [38-40].

where

is the position index;

is the dimension index;

is the embedding size.

Eqs. (7)–(9) define the linear transformations applied to the input embeddings, projecting them into query, key, and value subspaces:

where

,

, and

are learnable weight matrices responsible for transforming the input into distinct subspaces.

Eq. (10) then formalizes the scaled dot-product attention mechanism. This operation highlights the importance of certain time steps or features relative to others in determining anomalous patterns [

39].

where

is the dimensionality of each attention head.

Eqs. (11) and (12) extend this to multi-head attention, which aggregates multiple parallel attention mechanisms:

Eq. (13) defines the feed-forward network (FFNN) that processes the aggregated attention outputs. This non-linear transformation enriches the model’s representational capacity.

where

is the input vector corresponding to a single token or position in the sequence;

is the weight matrix;

is bias vector.

Finally, Eqs. (14) and (15) incorporate residual connections and layer normalization, ensuring stable training and efficient gradient propagation. Together, these formulations establish the transformer encoder’s ability to process multivariate time-series data effectively, providing the foundation for robust false data injection detection when integrated into the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL framework [

40].

2.4. IGWO

The GWO algorithm was first introduced by Mirjalili et al. [

41] in 2014 as a nature-inspired meta-heuristic designed to solve complex optimization problems. Inspired by the leadership hierarchy and hunting mechanism of grey wolves in nature, GWO quickly gained attention due to its simplicity, low parameter dependency, and strong balance between exploration and exploitation. Its ability to navigate large and high-dimensional search spaces effectively makes it particularly suitable for continuous, discrete, and combinatorial optimization problems where traditional methods often fail. One of the major advantages of GWO is its adaptability and robustness in escaping local optima while converging toward global solutions. Compared to other evolutionary algorithms, it requires minimal parameter tuning, yet delivers competitive performance across diverse applications, from feature selection and neural network training to engineering design and intrusion detection. These features make GWO a popular choice for real-world optimization problems in Industry 4.0 systems, where adaptability, efficiency, and scalability are critical [

42].

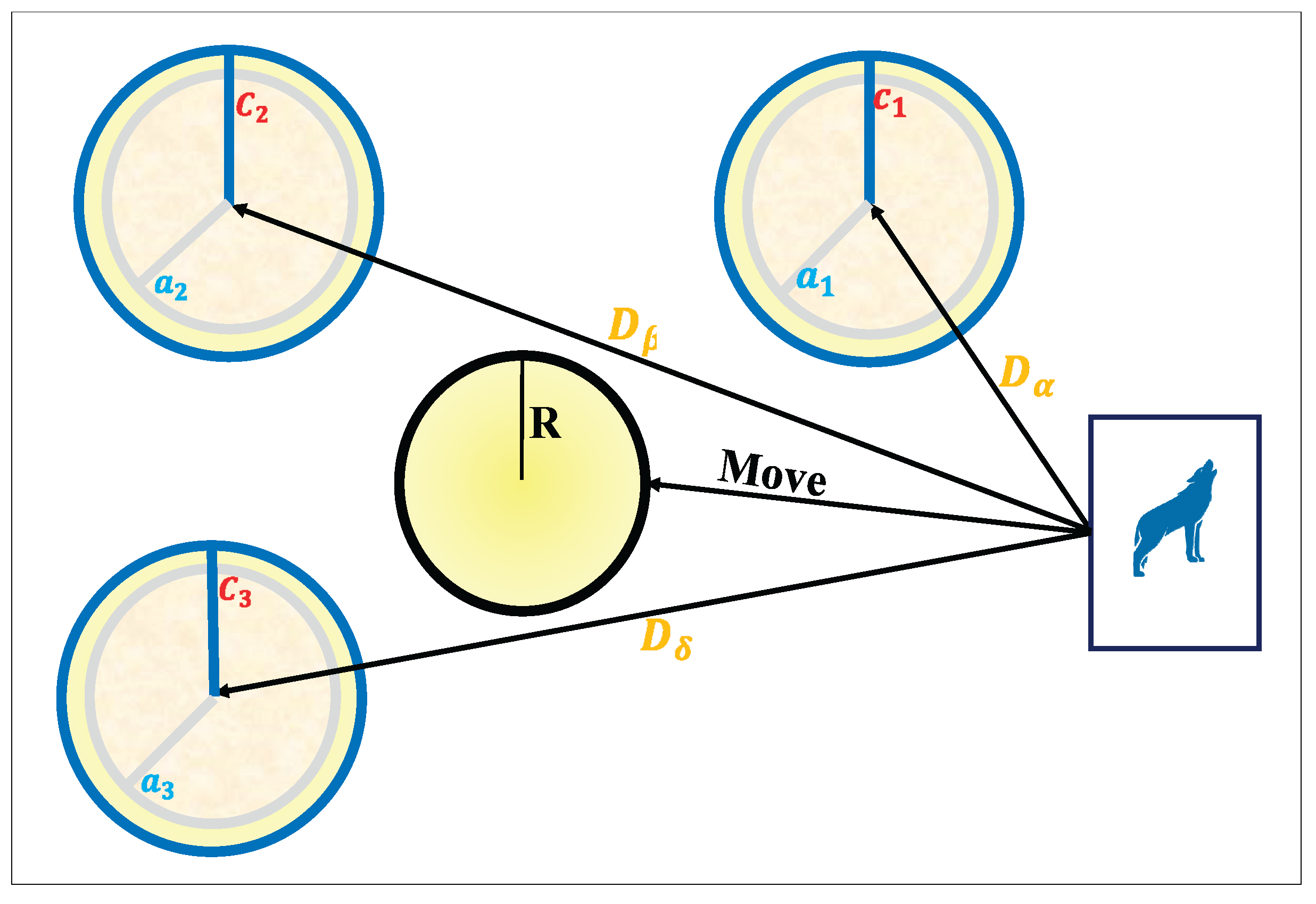

The social hierarchy of GWO consists of four main roles: alpha, beta, delta, and omega. The alpha wolf represents the best candidate solution and is primarily responsible for guiding the optimization process. Beta wolves are considered the second-best solutions, supporting the alpha in decision-making and guiding the pack. Delta wolves come third in the hierarchy and help to manage the omegas while also assisting the alpha and beta in the hunting process. Finally, the omega wolves represent the rest of the population and explore the search space more broadly. This hierarchical model allows GWO to strike a balance between intensification around the best solutions and diversification across unexplored regions. The mathematical formulation of GWO begins with the Eqs. (16)–(19), which model the encircling behavior of wolves around their prey. These equations describe how wolves update their positions by considering the distance between their current location and the prey (optimal solution). The coefficient vectors control the influence of the prey and randomness during the search process, while the parameter

is gradually decreased from 2 to 0, ensuring a transition from exploration to exploitation as iterations progress [

43].

where

is hunting position vector,

is the position vector of a wolf,

and

are random vectors in the interval [0, 1],

and

are coefficient vectors, the

vector is linearly reduced from 2 to 0 during the repetition.

Eqs. (20)–(22) extend this model to simulate the cooperative hunting strategy of grey wolves. Here, the wolves rely on the positions of the three best solutions in the population (alpha, beta, and delta) to update their own positions. By calculating distances and combining the corresponding candidate solutions, each wolf updates its position as the average influence of these three leaders. This mechanism ensures that the pack collectively converges toward the global optimum by balancing guidance from multiple elite solutions.

where

is hunting position vector,

is the position vector of a wolf,

and

are random vectors in the interval [0, 1],

and

are coefficient vectors, the

vector is linearly reduced from 2 to 0 during the repetition [

43].

As shown in Fig. 4, the encircling mechanism allows wolves to move toward the prey from different directions under the influence of the alpha, beta, and delta wolves. Each of these leaders exerts a force that guides the other wolves, while the randomized coefficients ensure stochastic exploration. This cooperative hunting strategy mimics real-world grey wolf behavior and provides GWO with the ability to avoid premature convergence while steadily moving toward the optimal solution [

44].

The original GWO, despite its success, suffers from several limitations that hinder its performance in more complex optimization problems. One of the key issues is premature convergence, where the algorithm tends to get trapped in local optima due to excessive reliance on the three leader wolves (, , and ). This hierarchical structure, although effective for exploitation, sometimes restricts the diversity of solutions within the population, leading to weak exploration in high-dimensional or rugged search spaces. Another limitation is the imbalanced trade-off between exploration and exploitation: in early iterations, exploration is dominant, but as the control parameter decreases linearly toward zero, the algorithm heavily favors exploitation, which may reduce its ability to discover new promising regions of the search space. This rigidity in the exploration–exploitation mechanism limits the adaptability of GWO in dynamic or non-convex optimization landscapes [43-45].

Figure 4.

The encircling and hunting mechanism of the GWO.

Figure 4.

The encircling and hunting mechanism of the GWO.

To address these shortcomings, we propose an enhanced GWO by introducing a fifth wolf, denoted as , which acts as a balancer between exploration and exploitation. Unlike , , and that focus primarily on guiding the pack toward the best solutions, and that represents the general population, the -wolf introduces an additional adaptive mechanism. Its role is twofold: (i) to support elite wolves by reinforcing convergence when the pack is closing in on promising areas, and (ii) to inject exploration by periodically diverging toward less-explored regions of the search space. This hybrid role makes a mediator that dynamically adjusts the balance of the algorithm depending on the state of convergence, preventing stagnation and ensuring diversity. Specifically, the -wolf contributes by maintaining a memory of under-explored zones and periodically guiding ω wolves toward these areas, while also refining solutions around the leaders when diversity is already sufficient. By combining these dual responsibilities, ensures that the algorithm does not overcommit to exploitation too early, while still exploiting when necessary. Moreover, can interact with , , and by partially averaging their influence, introducing a controlled level of randomness to avoid overfitting to a narrow search region. This makes the enhanced GWO more resilient to local optima and improves its adaptability across various problem domains.

Eqs. (23)–(25) present the updated formulation. Eq. (23) computes the distance components for all four guiding wolves (

,

,

, and

), thereby expanding the search guidance to include the new balancer wolf. Eq. (24) updates the candidate positions by considering the influence of each leader individually, while Eq. (25) finalizes the new position of a wolf as the average of these four influences. These updated equations ensure that the search process is no longer dominated solely by the three best solutions. Instead, the φ-wolf introduces an adaptive balance by reinforcing elite-driven exploitation while also guiding exploration into under-explored regions. Consequently, the improved GWO avoids premature convergence, maintains diversity longer in the optimization process, and enhances its global search capability.

2.5. Proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL

illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL framework, where the agent interacts continuously with the environment through a reinforcement learning loop. The figure highlights how raw state inputs from the environment are processed by the transformer encoder, how the DRL agent selects an action based on the encoded state, and how the proposed IGWO module updates the system by optimizing hyper-parameters using error feedback. This closed-loop cycle integrates representation learning, adaptive decision-making, and evolutionary optimization into a single robust pipeline for false data injection detection in Industry 4.0 smart water infrastructures. The proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL framework establishes a closed-loop pipeline in which an agent continuously interacts with the environment of Industry 4.0 smart water infrastructures to detect FDI attacks. At each time step, the environment provides a state vector derived from multivariate sensor readings, actuator signals, and control parameters. This state is passed into the agent, where the transformer encoder acts as the initial feature extraction module, capturing temporal dependencies and contextual relations among the inputs. The agent then decides on an action based on the learned detection policy. The environment subsequently returns a reward signal reflecting the accuracy of this decision, which is used to refine the detection strategy in subsequent iterations.

In this study, the state vector represents a multidimensional snapshot of the physical water process at time step t. Each dimension corresponds to a specific sensor or actuator signal collected from the SWAT, WADI, and BATADAL infrastructures. These include flow rates, water levels, valve positions, pump statuses, pressures, and control setpoints across different physical stages of the treatment and distribution systems. Consequently, the Transformer encoder receives a time-windowed sequence of these multivariate states, forming an input tensor of shape , where denotes the temporal window length and the number of monitored variables. Physically, each feature captures a key operational property of the industrial water process (flow and pressure reflect hydraulic dynamics, level sensors indicate storage conditions, and actuator signals represent control commands). The Transformer leverages these heterogeneous dimensions to extract temporal–spatial dependencies, allowing the DRL agent to interpret the system’s evolving operational state and detect anomalous manipulations indicative of false data injection attacks.

Figure 5.

The proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL architecture.

Figure 5.

The proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL architecture.

Within this interaction loop, the role of the transformer encoder is to transform raw sequential data into high-level representations suitable for decision-making. Unlike conventional architectures, the transformer utilizes self-attention to identify both short- and long-term correlations across heterogeneous time series without suffering from vanishing gradients or bottlenecks in sequential processing. The output of the Transformer forms a high-dimensional embedding that captures temporal and cross-variable dependencies among multivariate sensor and actuator signals. Physically, this representation reflects the instantaneous operational condition of the water infrastructure, serving as the input state for the DRL agent to evaluate and classify normal versus attack scenarios. By integrating positional encodings, the transformer preserves the order of events while enabling parallelized computations. As a result, the input state is encoded into a rich embedding that highlights subtle anomalies characteristic of stealthy FDI attacks. The DRL agent builds on these embeddings to derive an optimal detection policy. It interprets the transformer’s outputs as part of the state representation and applies reinforcement learning to map these states to actions. The learning process is guided by cumulative rewards, where correct detection of attacks yields positive reinforcement and misclassifications incur penalties. Over time, the agent improves its classification accuracy by dynamically adapting to evolving attack strategies. This adaptability is critical for Industry 4.0 environments, where attack vectors are often non-stationary and conventional supervised models fail to generalize.

The decision-making process in DRL hinges on balancing exploration and exploitation. Here, the integration of DRL ensures that the framework can continuously refine its policy in the presence of uncertainty, delayed feedback, and adversarial manipulation. Unlike static detection methods, this allows the system to remain effective under novel or evolving FDI scenarios. Despite the strengths of transformers and DRL, the performance of such a hybrid system is highly sensitive to the choice of hyper-parameters, including learning rates, embedding dimensions, attention head sizes, discount factors, and exploration-exploitation coefficients. Suboptimal hyper-parameter configurations can lead to unstable training, poor convergence, or excessive computational cost. This challenge necessitates the inclusion of an evolutionary optimizer capable of fine-tuning these critical parameters in an adaptive manner. The novel IGWO fulfills this role by systematically tuning hyper-parameters to maximize detection accuracy while minimizing execution time. By modeling the leadership hierarchy and hunting mechanism of grey wolves, IGWO efficiently explores the hyper-parameter search space.

The introduction of the

-wolf as a balancer between exploration and exploitation enhances this capability, ensuring that the optimizer avoids premature convergence and maintains solution diversity. Consequently, IGWO ensures that the transformer and DRL operate under conditions that yield stable and superior performance.

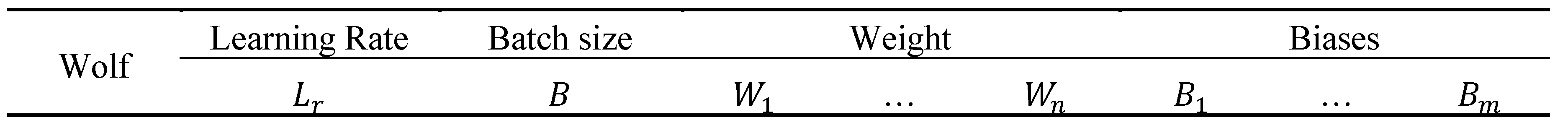

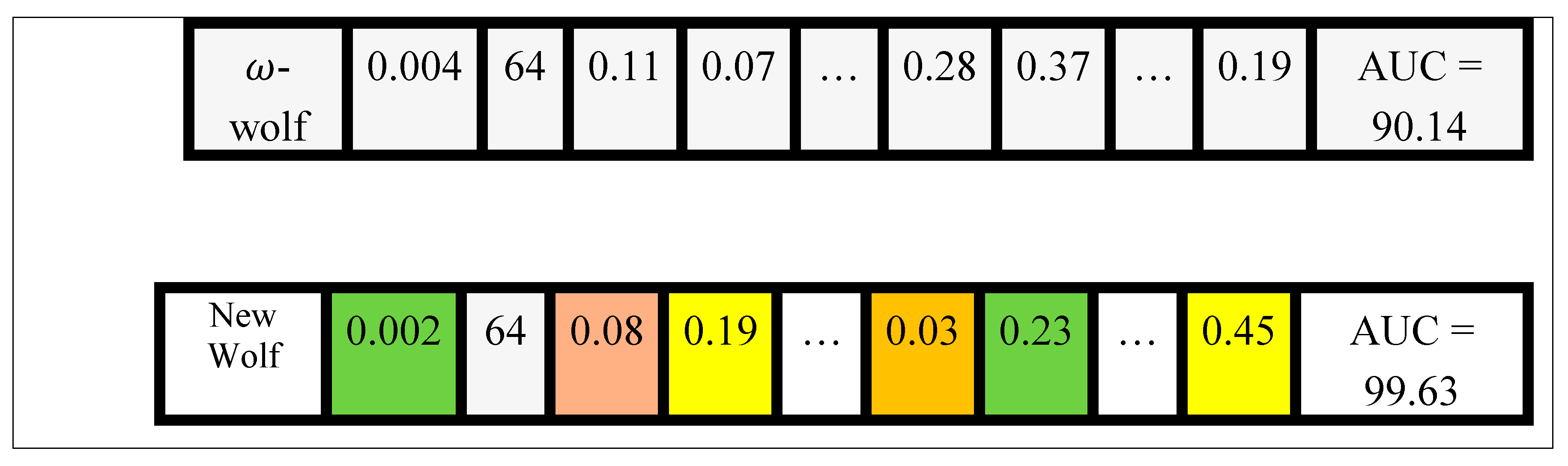

Figure 6 illustrates the schematic structure of an individual wolf in the IGWO population. Each wolf encodes a candidate hyper-parameter configuration composed of learning rate, batch size, and representative weight and bias values from the Transformer–DRL network. The figure is meant purely for schematic demonstration; it does not display every parameter in the model but shows a representative subset to visualize how a single search agent stores and manipulates its solution vector during optimization.

Figure 6.

The structure of a wolf in Evo-Transformer–DRL.

Figure 6.

The structure of a wolf in Evo-Transformer–DRL.

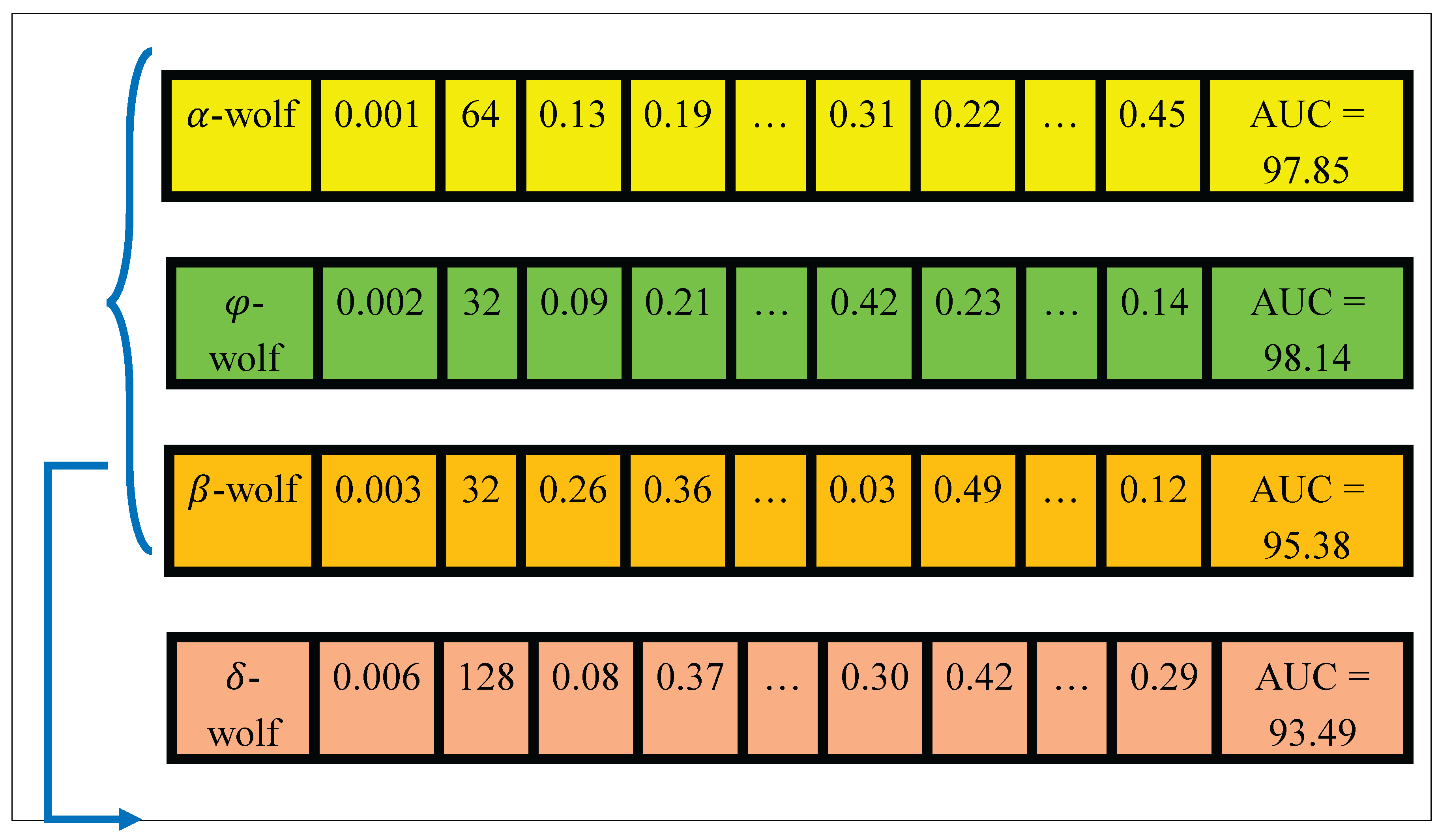

Figure 7 provides an illustrative example of how IGWO updates the positions of wolves during the evolutionary process. As shown, the new wolf adjusts each of its genes (hyper-parameter values) by referencing the corresponding components of multiple leader wolves each contributing certain genes based on their color-coded influence. For instance, two genes are inherited from the

-wolf and two from the

-wolf. This cooperative update allows the new wolf to combine the best traits of high-performing solutions, resulting in a configuration with higher overall fitness (in this example, improved AUC = 99.63 compared with previous leaders). The figure thus provides an illustrative, numeric visualization of the IGWO’s internal mechanism for adaptive hyper-parameter tuning in the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL framework.

In this configuration, the interaction between the three components is tightly coupled: the transformer provides high-quality embeddings, the DRL agent leverages these embeddings for adaptive decision-making, and IGWO refines the system’s operational parameters to maintain an optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency. This synergy creates a self-reinforcing cycle: better embeddings enable more effective learning policies, while optimized hyper-parameters ensure that both modules reach their full potential. Together, they form a robust and generalizable architecture capable of addressing the dynamic nature of FDI attacks in smart water systems.

Figure 7.

An example of position updates in the IGWO algorithm.

Figure 7.

An example of position updates in the IGWO algorithm.

3. Results

The experimental evaluation of the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL framework was carried out entirely in Python 3.10, leveraging a stable yet modern software stack to ensure both performance and reproducibility. Core numerical operations and data handling were managed through NumPy 1.24 and Pandas 1.5, while the learning modules were implemented using TensorFlow 2.12 and PyTorch 2.0, complemented by scikit-learn 1.3 for baseline comparisons and preprocessing. Visualization and statistical analyses were performed with Matplotlib 3.7 and Seaborn 0.12, providing clear insight into model behavior across experiments. All computations were executed on a high-performance workstation equipped with an Intel Core i9-12900K CPU (16 cores, 3.2 GHz), 64 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU with 24 GB VRAM, operating on Ubuntu 22.04 LTS. This configuration enabled efficient large-scale training and ensured that cross-testbed evaluations could be performed without memory or runtime bottlenecks.

For a comprehensive evaluation, several state-of-the-art algorithms were implemented alongside the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL framework. BERT was included as a benchmark due to its powerful contextual representation learning ability, which has shown strong performance in sequential anomaly detection tasks but often struggles with domain adaptation in cyber-physical environments. The vanilla Transformer was evaluated to highlight the benefit of combining temporal feature extraction with reinforcement learning, as it excels at capturing long-range dependencies but lacks adaptive decision-making. DRL alone was considered because of its adaptability in dynamic and uncertain environments, yet its performance typically degrades without advanced representation learning modules. Similarly, LSTM was included for its established ability to handle temporal correlations in multivariate time series, though it is limited by sequential computation bottlenecks and difficulty in capturing long-term dependencies. In addition, CNN was implemented for its efficiency in extracting local temporal-spatial patterns, which makes it effective for detecting abrupt anomalies but insufficient for capturing long-range correlations. Finally, SVM served as a classical machine learning baseline, offering simplicity and robustness for binary classification but limited scalability in high-dimensional and evolving data streams. Together, these baselines represent a diverse spectrum of traditional, DL, and RL paradigms, making them suitable comparators. Evaluating against these methods underscores the advantages of the hybrid Evo-Transformer-DRL, which combines the contextual modeling of transformers, the adaptability of DRL, and the fine-tuned optimization of IGWO, thereby demonstrating superior generalization and resilience for false data injection detection in Industry 4.0 smart water systems.

For evaluating the algorithms, a set of metrics was employed, including accuracy, recall, area under the curve (AUC), root mean square error (RMSE), convergence trend, statistical t-test, runtime, and variance. According to Eq. (26), accuracy is defined as the ratio of correctly classified samples (true positives and true negatives) to the total number of samples. This metric reflects the overall correctness of the model’s predictions. A higher accuracy indicates better general performance, although it may be misleading in imbalanced datasets where the normal class dominates.

As shown in Eq. (27), AUC is computed as the integral of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve across all threshold values. This metric measures the separability of the classes independent of a specific threshold. An AUC value closer to 1.0 indicates excellent discrimination between attack and normal classes, while a value of 0.5 corresponds to random guessing.

where,

is ROC curve at threshold

.

Based on Eq. (28), recall is defined as the proportion of true positives to the sum of true positives and false negatives. This metric reflects the sensitivity of the model in detecting actual attacks. A higher recall indicates that fewer attacks are missed, which is critical in security-sensitive environments such as false data injection detection.

Eq. (29) defines RMSE as the square root of the mean squared error between the actual values and the predicted values. This metric quantifies the prediction error magnitude, where lower RMSE values correspond to more stable and accurate predictions.

where,

is the actual value,

is the predicted value, and

is the total number of data points.

The statistical t-test was applied to evaluate whether the improvements of the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL framework over baseline algorithms are statistically significant. A p-value lower than 0.01 confirms that the performance difference is unlikely due to randomness, strengthening the reliability of the results. Runtime measures the computational cost in terms of wall-clock time required for training and inference. Lower runtime is desirable, especially for real-time deployment in Industry 4.0 systems where timely attack detection is critical. Finally, variance captures the stability of the model across multiple independent runs with different random seeds. Lower variance indicates more consistent performance, which is important for ensuring reproducibility and robustness under varying conditions.

Before implementation, careful hyper-parameter tuning is essential, as it directly affects convergence speed, stability, and final detection accuracy. Improper settings may lead to underfitting, overfitting, or unstable training, while optimal configurations ensure reliable and reproducible performance across datasets. In our framework, the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL benefited from the IGWO, which adaptively searched for the best parameter set to balance exploration and exploitation. For the baseline architectures (BERT, LSTM, CNN, and SVM), a grid search strategy was adopted to systematically explore parameter combinations and select the configurations yielding the best validation results.

Table 1 presents the final optimized hyper-parameters for all evaluated algorithms.

For Evo-Transformer-DRL, the IGWO optimizer selected a learning rate of 0.004, batch size of 64, dropout of 0.2, 12 attention heads, and 10 encoder layers, with a discount factor of 0.91 and ε-greedy value of 0.41. The optimizer parameters included a population size of 130 and 300 iterations, with weight decay set at 0.04, which collectively ensured stable training dynamics and superior generalization. For BERT, the optimal configuration included a learning rate of 0.002, batch size of 128, 10 self-attention heads, and 10 encoder layers, using GELU activation with the Adam optimizer. The LSTM achieved its best performance with a learning rate of 0.06, batch size of 128, sequence length of 8, and tanh and sigmoid activations optimized via SGD. The CNN baseline converged optimally with 8 convolutional layers, a 5×5 kernel size, max pooling (2×2), and 64 neurons using GELU and Adam. Finally, the SVM baseline attained its best results using both linear and RBF kernels, with γ = 0.003 and 300 estimators. These configurations reflect the optimized trade-off between accuracy, robustness, and efficiency, providing a fair ground for comparative evaluation with the proposed method.

As presented in

Table 2, the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL framework consistently outperforms all baseline methods across the three benchmark datasets. Specifically, it achieves the highest accuracy, recall, and AUC on SWAT (99.19%, 99.63%, and 99.85%), WADI (98.67%, 99.07%, and 99.52%), and BATADAL (98.21%, 98.73%, and 99.14%). In contrast, conventional baselines such as SVM and CNN exhibit significantly lower scores, particularly on the more complex WADI and BATADAL datasets, highlighting their limited ability to generalize under noisy and heterogeneous conditions. The superior performance of the Evo-Transformer-DRL can be attributed to its synergistic architecture. The Transformer encoder ensures robust temporal and contextual representation learning, while the DRL agent dynamically adapts detection policies to evolving attack patterns. Crucially, the integration of IGWO for hyper-parameter optimization fine-tunes the model to achieve an optimal trade-off between detection accuracy and computational efficiency. This combination explains why the proposed framework maintains near-perfect Recall values, effectively minimizing false negatives.

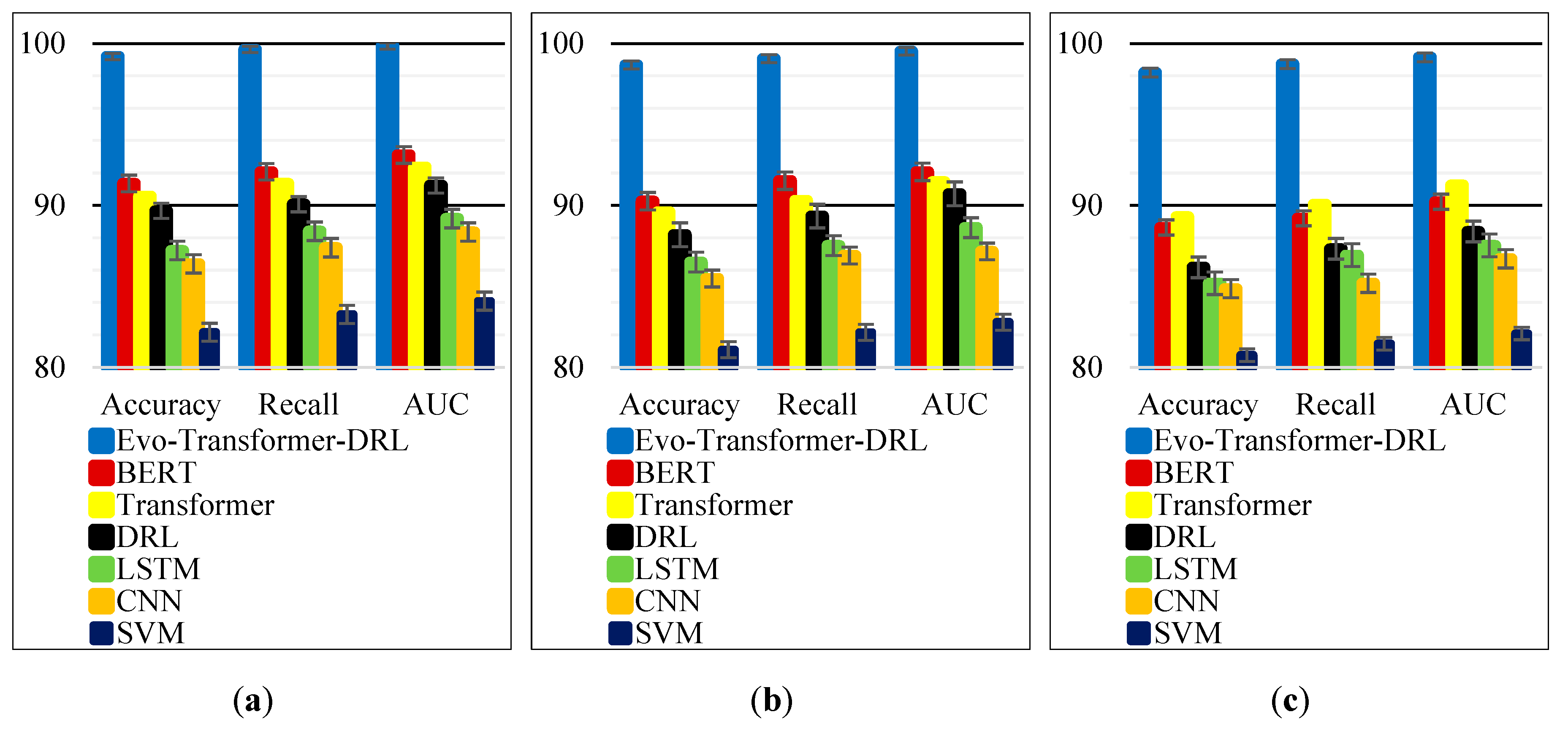

As shown in Fig. 8, the results from

Table 2 are presented in a visual form to highlight performance differences among the models. Each panel corresponds to one dataset, with accuracy, recall, and AUC illustrated side by side. Across all three datasets, the Evo-Transformer-DRL consistently achieves the highest values across all metrics, clearly outperforming baselines such as BERT, Transformer, DRL, LSTM, CNN, and SVM. The superiority of the proposed method is especially evident in recall and AUC, where it maintains near-perfect detection capability with minimal false negatives. The comparative plots also reveal the performance gap between DL–based approaches and traditional ML. While CNN and LSTM capture local and temporal dependencies, they lag behind the transformer-based models in handling long-term correlations. SVM consistently records the lowest scores, confirming its limited scalability in high-dimensional settings. By contrast, the Evo-Transformer-DRL leverages representation learning, adaptive decision-making, and IGWO-driven optimization, leading to robust results across diverse datasets. This confirms that the proposed framework not only achieves state-of-the-art accuracy but also ensures generalizability in cross-testbed scenarios.

Figure 8.

Visual comparison of accuracy, recall, and AUC for the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL and baseline models across: (a) SWAT; (b) WADI; (c) BATADAL datasets.

Figure 8.

Visual comparison of accuracy, recall, and AUC for the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL and baseline models across: (a) SWAT; (b) WADI; (c) BATADAL datasets.

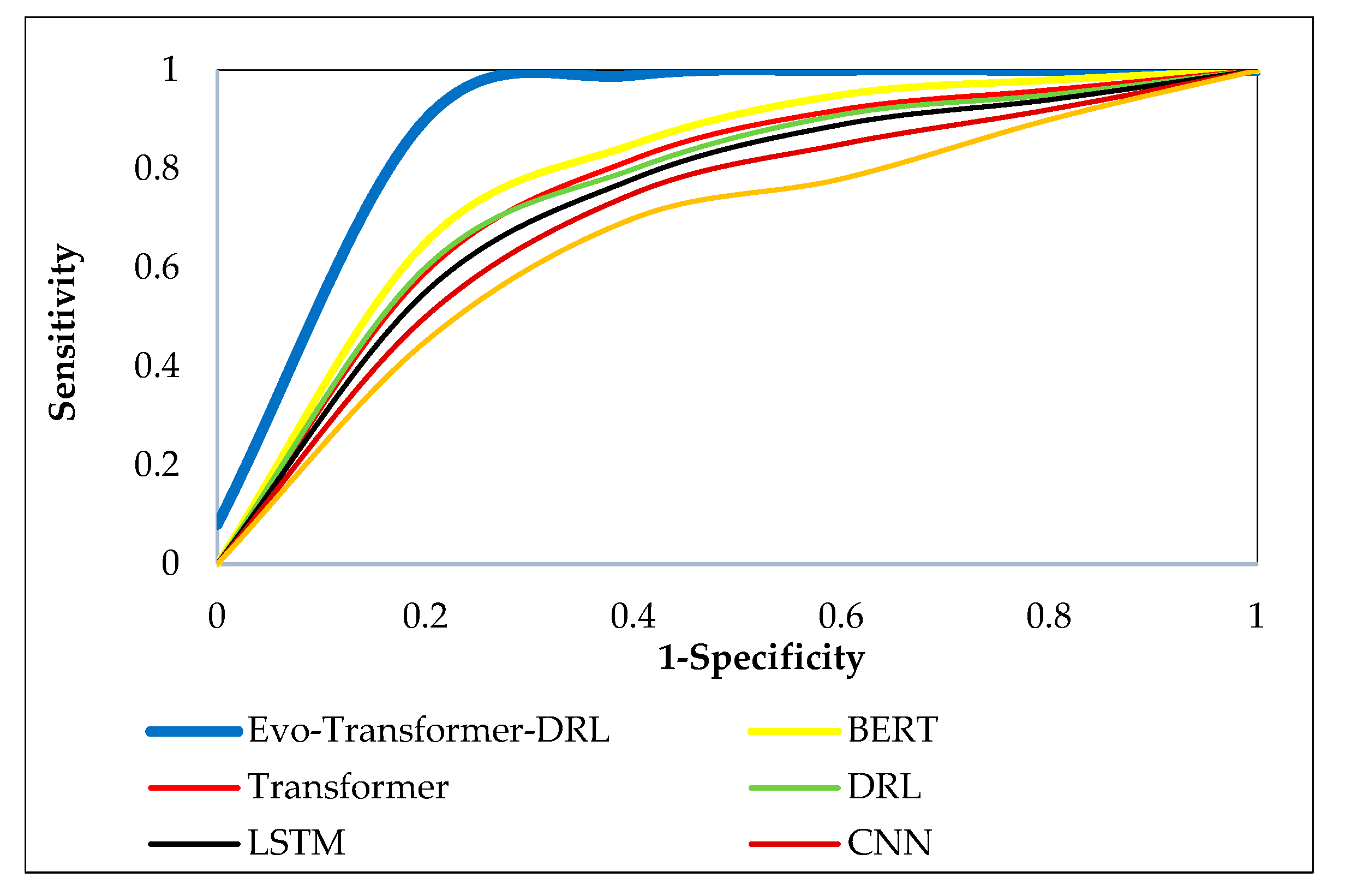

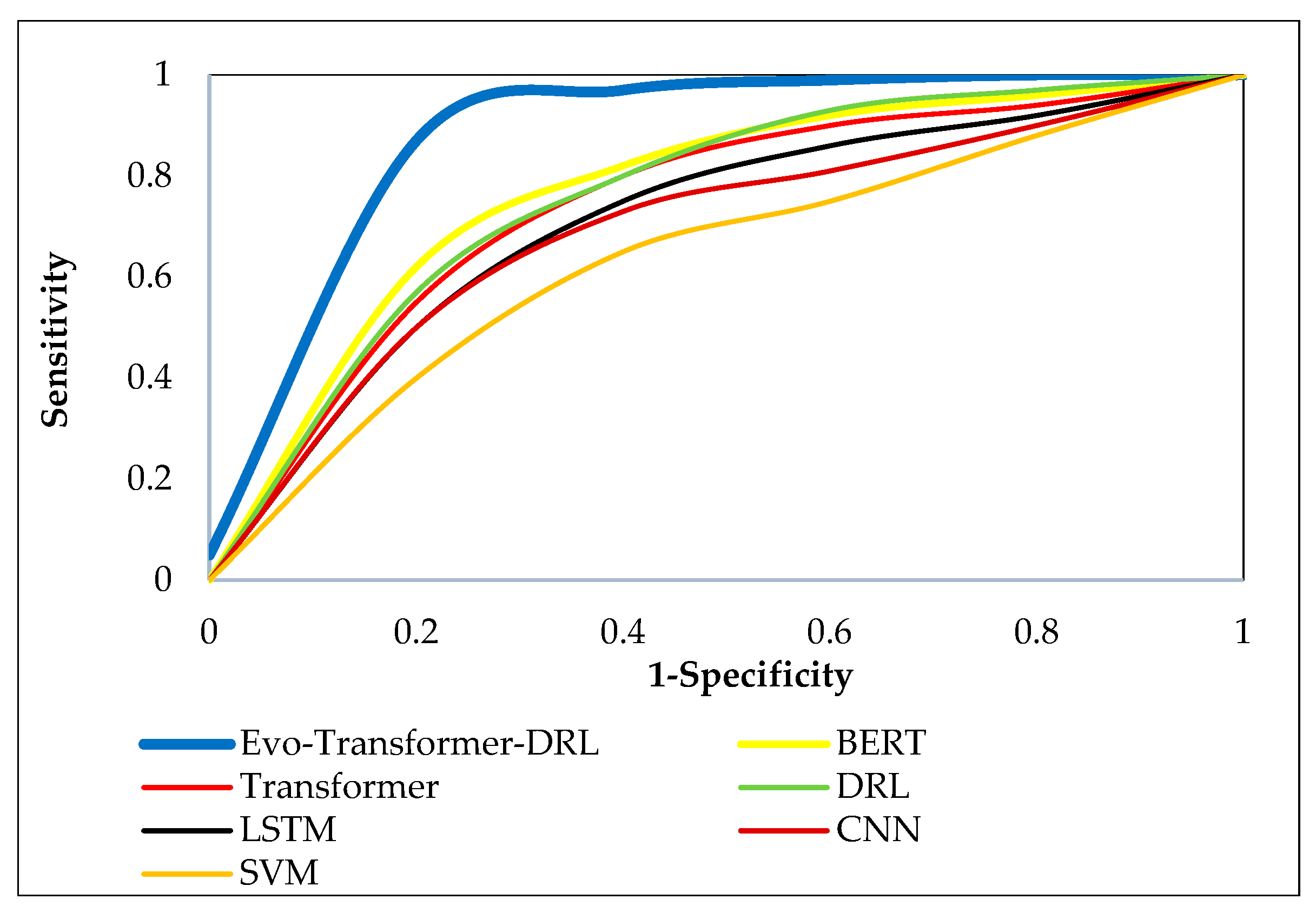

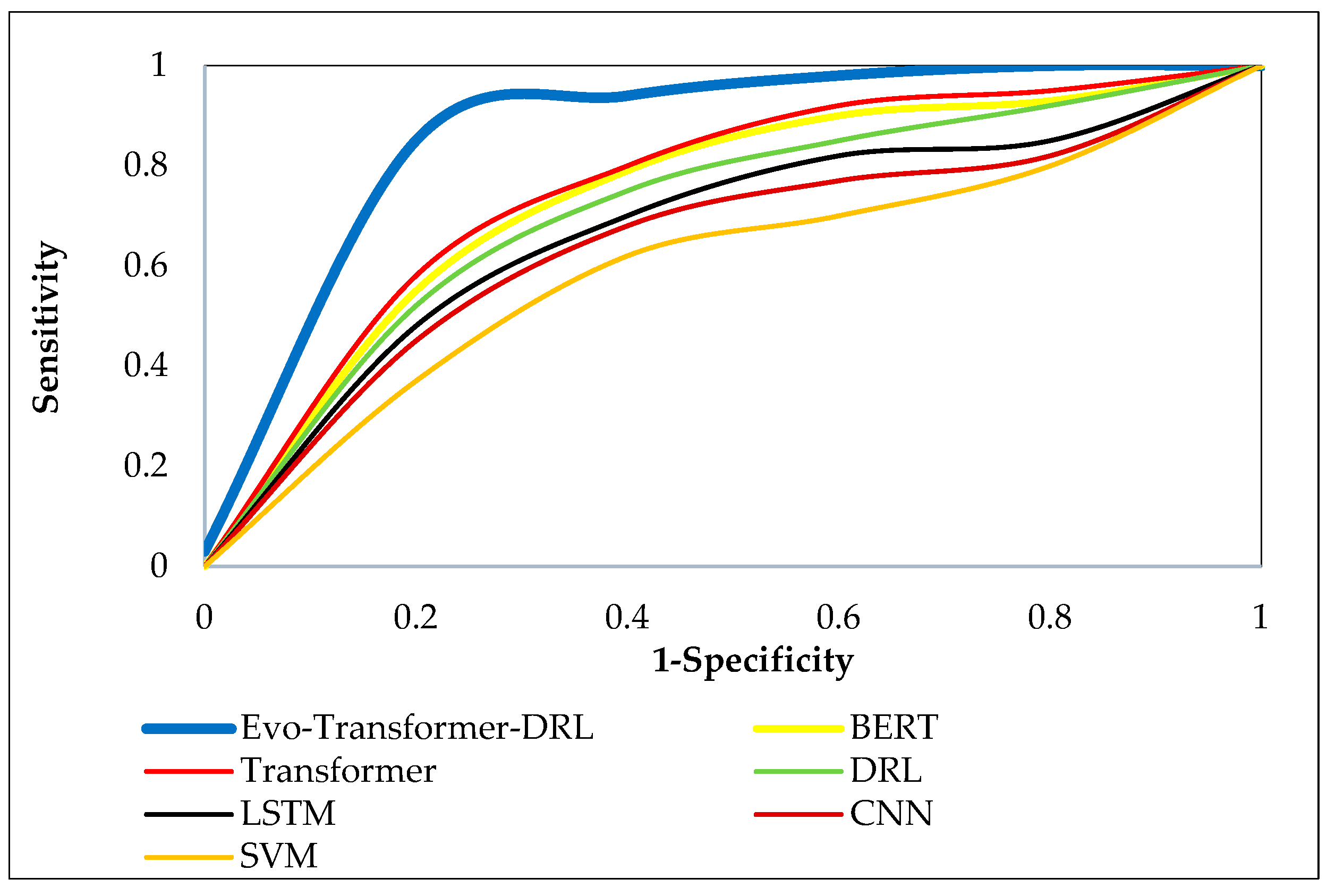

Figs. 9–11 illustrate the ROC curves of the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL framework against baseline models across the three benchmark datasets. These curves show the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity, effectively representing the discriminative power of each algorithm. In all datasets, the curve of Evo-Transformer-DRL remains consistently closer to the upper-left corner of the plot, confirming its superior classification capability compared to BERT, Transformer, DRL, LSTM, CNN, and SVM. This visual evidence directly corresponds with the higher AUC values previously reported in

Table 2. The comparative analysis highlights that while transformer-based baselines such as BERT and vanilla Transformer perform better than LSTM, CNN, and SVM, they still lag behind the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL. The advantage of our method is most prominent in SWAT and WADI, where the ROC curve almost perfectly approaches the ideal boundary, reflecting near-optimal detection rates with minimal false positives. Even in BATADAL, which is the most challenging dataset due to its stochastic nature and stealthier attacks, Evo-Transformer-DRL demonstrates a noticeable margin over other models.

Figure 9.

ROC curve comparison of Evo-Transformer-DRL and baseline models on the SWAT dataset.

Figure 9.

ROC curve comparison of Evo-Transformer-DRL and baseline models on the SWAT dataset.

Figure 10.

ROC curve comparison of Evo-Transformer-DRL and baseline models on the WADI dataset.

Figure 10.

ROC curve comparison of Evo-Transformer-DRL and baseline models on the WADI dataset.

Figure 11.

ROC curve comparison of Evo-Transformer-DRL and baseline models on the BATADAL dataset.

Figure 11.

ROC curve comparison of Evo-Transformer-DRL and baseline models on the BATADAL dataset.

Table 3 illustrates the effect of integrating various architectural components on detection performance. The results highlight not only the incremental benefits of combining deep sequence models with reinforcement learning, but also the significant role of IGWO in optimizing hyper-parameters. The analysis shows that the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL achieves the best results across all datasets, with accuracy, recall, and AUC values consistently higher than other combinations. For instance, IGWO-Transformer and IGWO-DRL both outperform their non-optimized counterparts, confirming that the grey wolf optimizer significantly enhances performance by fine-tuning critical hyper-parameters such as learning rate, dropout, and discount factor. Moreover, Transformer-DRL achieves better results than standalone Transformer or DRL, proving the advantage of combining representation learning with adaptive decision-making. However, it is only when IGWO is introduced that the models reach near-optimal performance, as seen in the Evo-Transformer-DRL. This indicates that the optimizer not only balances exploration and exploitation during parameter search but also ensures that the hybrid architecture converges efficiently to a stable and robust solution.

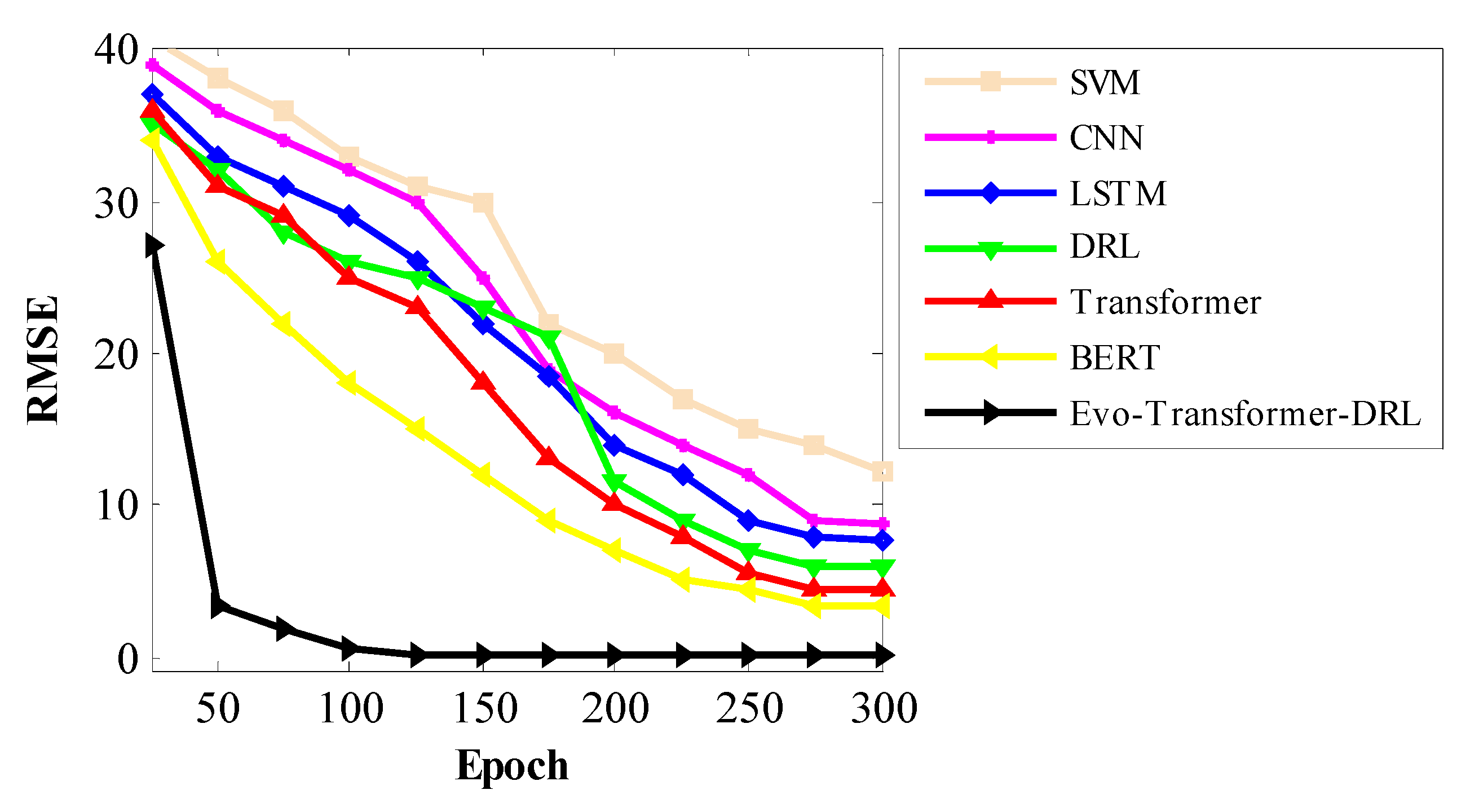

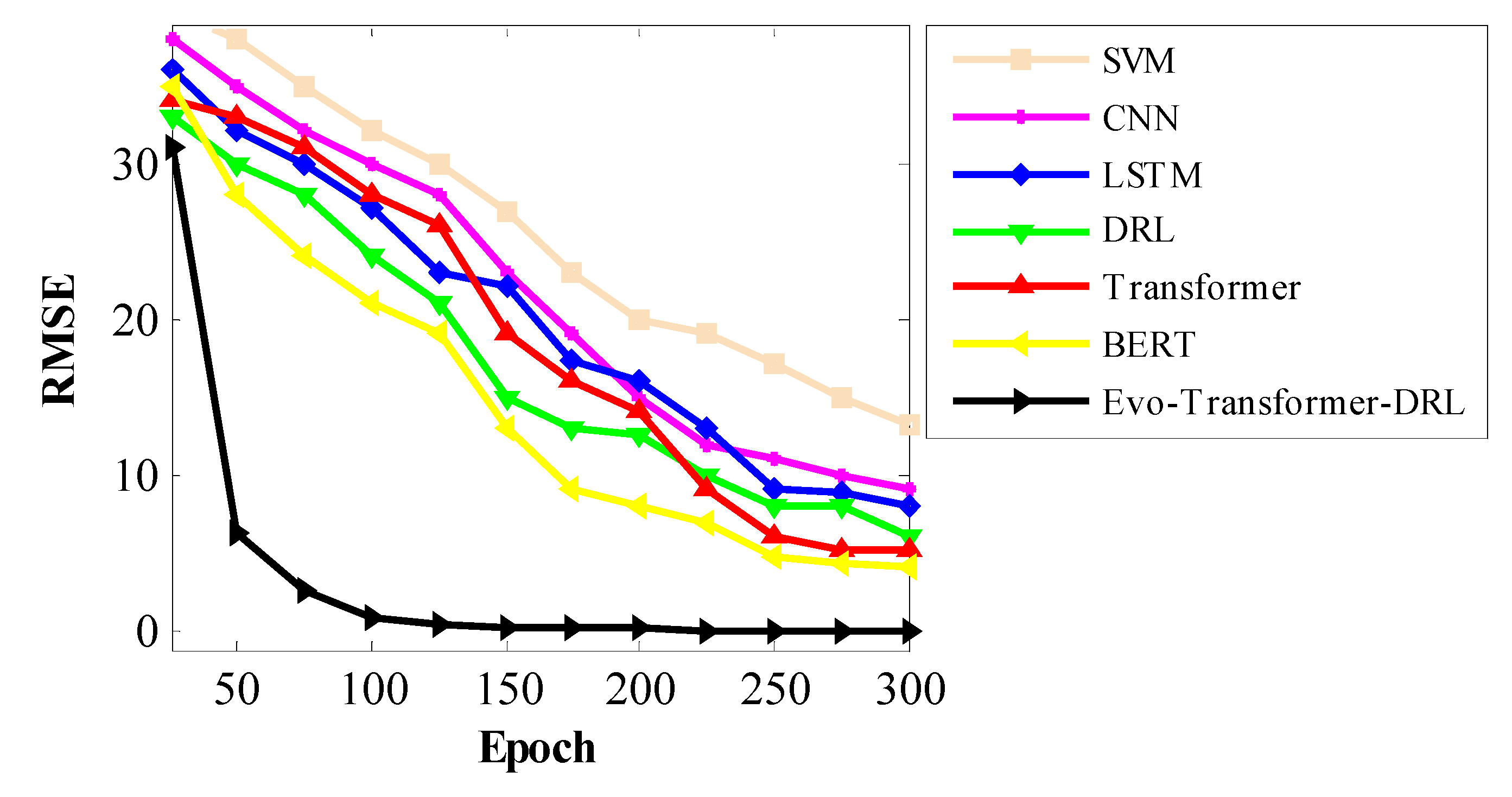

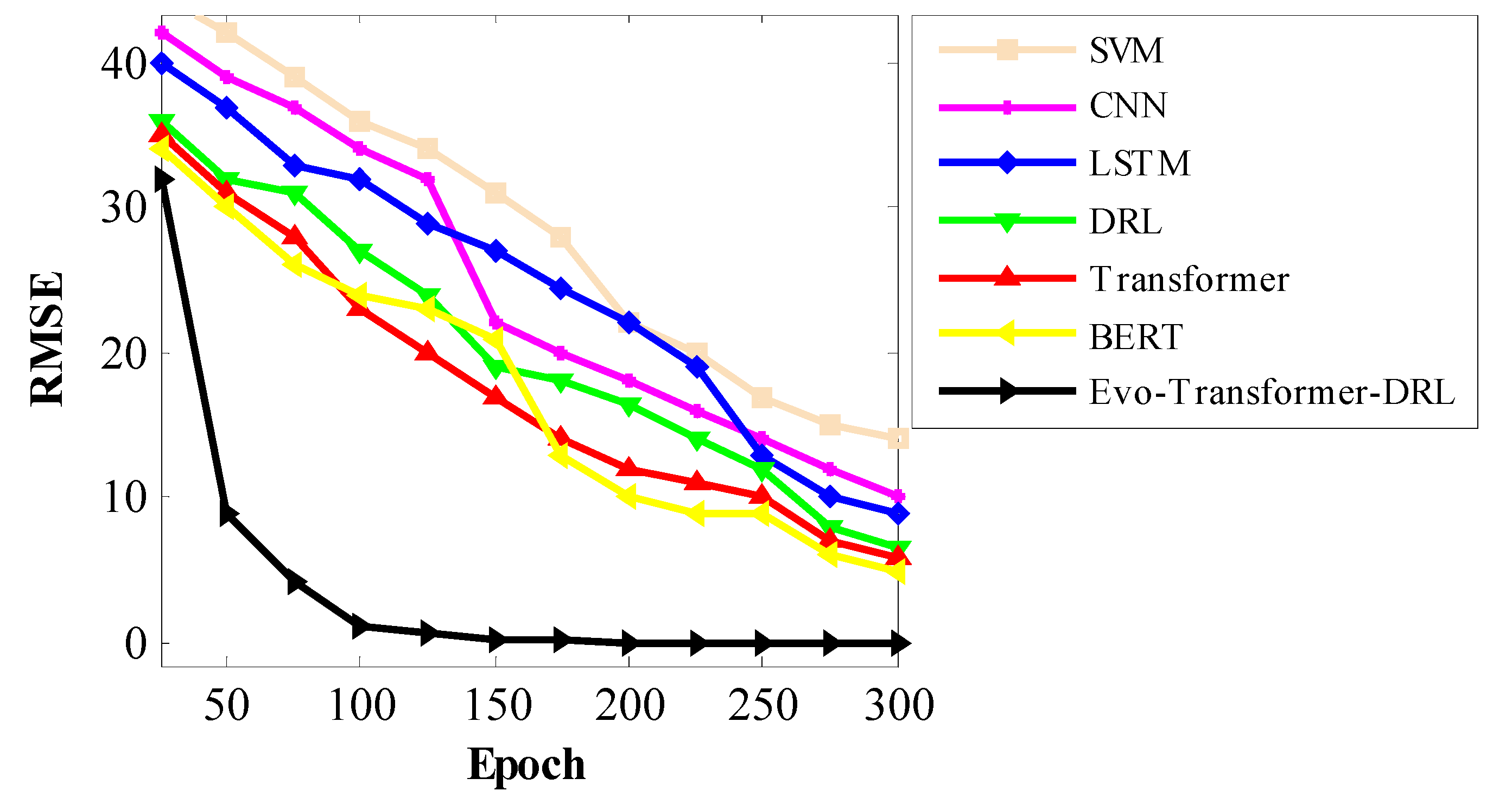

Figs. 12–14 illustrate the convergence behavior of all evaluated models during training, with RMSE plotted against epochs for SWAT, WADI, and BATADAL respectively. These curves clearly demonstrate the learning dynamics of each architecture, highlighting how fast and stable they approach their optimal states. Across all datasets, Evo-Transformer-DRL achieves rapid convergence, reaching near-zero RMSE within the first 100 epochs, whereas other models require substantially more iterations and still plateau at higher error values. The analysis shows that traditional baselines such as SVM and CNN not only converge slowly but also maintain high residual errors, indicating limited learning capacity for complex temporal dependencies. LSTM and DRL improve upon them but still struggle with slower convergence and higher variance across epochs. Transformer and BERT exhibit better stability but require longer training to reduce RMSE significantly. In contrast, Evo-Transformer-DRL benefits from its hybrid architecture and IGWO-driven optimization, which accelerates convergence and ensures consistent error minimization. This demonstrates the framework’s efficiency in balancing representation learning, adaptive decision-making, and parameter tuning, ultimately leading to faster and more reliable model training across diverse datasets.

Beyond the results already discussed (such as accuracy, recall, and AUC) the evaluated architectures also reveal important insights into their stability and computational efficiency. While performance metrics highlight detection capability, a complete assessment must also consider how reliably each model behaves across multiple runs and how practical they are for real-time deployment in critical infrastructures. Therefore, in the following discussion we extend the evaluation by examining three additional criteria: variance, which reflects the stability of models under different runs and initializations; the t-test, which provides statistical validation of improvements over baseline methods; and runtime, which captures computational complexity and execution cost. These metrics allow us to assess not only effectiveness but also robustness and efficiency, offering a more holistic view of the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL framework in comparison to alternative architectures.

Figure 12.

Training convergence curves for different models on the SWAT dataset.

Figure 12.

Training convergence curves for different models on the SWAT dataset.

Figure 13.

Training convergence curves for different models on the WADI dataset.

Figure 13.

Training convergence curves for different models on the WADI dataset.

Figure 14.

Training convergence curves for different models on the BATADAL dataset.

Figure 14.

Training convergence curves for different models on the BATADAL dataset.

As shown in

Table 4, the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL demonstrates extremely low variance across all datasets, with values close to zero (e.g., 0.000005 on SWAT and 0.000092 on BATADAL). This highlights the remarkable stability of the framework compared to all baselines. In contrast, classical models like SVM and CNN exhibit the highest variances, often exceeding 10 in complex datasets such as WADI and BATADAL, indicating inconsistent behavior across multiple training runs. Even advanced baselines such as BERT, Transformer, and DRL record higher variances, confirming that while they can achieve good accuracy, their results are less reliable across different initializations and data distributions. The integration of IGWO into Evo-Transformer-DRL plays a crucial role in this stability, ensuring optimal hyper-parameter tuning that minimizes fluctuations during training.

From a real-world perspective, such stability is critical in Industry 4.0 water infrastructures, where false data injection attacks must be detected reliably under dynamic and noisy operating conditions. High variance in model behavior could translate to inconsistent detection, leading to missed attacks or unnecessary false alarms that disrupt operations. By achieving near-zero variance, Evo-Transformer-DRL provides consistent predictions, which is essential for trustworthiness in real-time industrial control systems. The ability of the architecture to combine transformer-based feature extraction, DRL’s adaptability, and IGWO’s stability optimization ensures not only high accuracy but also robustness under uncertainty, making it a practical solution for real-world cyber-physical security challenges.

Table 5 presents the outcomes of paired t-tests conducted between the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL and each baseline model. Across all comparisons, the p-values are well below the threshold of 0.01, confirming that the improvements of Evo-Transformer-DRL are statistically significant and not due to random variation. This validates that the observed gains in accuracy, recall, and AUC are consistent and robust, further reinforcing the superiority of the proposed framework over conventional baselines such as BERT, Transformer, DRL, LSTM, CNN, and SVM. These results are especially important in the context of industrial control security, where detection algorithms must demonstrate not only high average performance but also reliable and repeatable improvements under varying conditions. The significance confirmed by the t-test indicates that Evo-Transformer-DRL provides dependable advantages that can be trusted in real-world deployment.

Table 6 reports the runtime required for each model to reach specific RMSE thresholds. The results show that Evo-Transformer-DRL achieves these levels significantly faster than all baselines. For example, it reaches RMSE <15 in only 38 seconds, compared to 121 seconds for BERT and over 200 seconds for CNN and SVM. More importantly, Evo-Transformer-DRL is the only model capable of reaching RMSE <2 within 109 seconds, while none of the other architectures achieve this level of error reduction within the evaluated timeframe. Transformer, DRL, and BERT, while relatively competitive, still require three to six times more runtime to approach moderate thresholds such as RMSE <6, highlighting their higher computational burden. Traditional models like LSTM, CNN, and SVM perform poorly, failing to reach stricter error targets altogether, which underscores their limitations for real-time deployment in complex industrial scenarios. From a practical perspective, these results carry strong implications for real-world applications in Industry 4.0 water infrastructures. Faster convergence with lower RMSE means the system can adapt more quickly to dynamic operational states and emerging cyberattacks, ensuring reliable protection without imposing heavy computational delays. By combining efficient representation learning, reinforcement-driven adaptability, and IGWO-based hyper-parameter tuning, Evo-Transformer-DRL achieves both accuracy and efficiency. This balance makes it particularly well-suited for deployment in critical infrastructures, where computational complexity must remain manageable while maintaining robustness against sophisticated false data injection attacks.

4. Conclusions

The detection of false data injection attacks in cyber-physical water infrastructures is a critical requirement for maintaining operational security and reliability. To address this challenge, this paper introduced the Evo-Transformer-DRL framework, which combines transformer-based feature extraction, deep reinforcement learning for adaptive detection, and IGWO for hyper-parameter optimization. The framework was extensively evaluated on three widely used benchmark datasets (SWAT, WADI, and BATADAL) representing real-world and simulation-based water treatment and distribution systems. A comprehensive set of evaluation metrics, including accuracy, recall, AUC, RMSE, variance, statistical t-tests, and runtime analysis, were employed to assess the effectiveness, stability, and efficiency of the proposed approach in comparison to state-of-the-art baselines.

On all three datasets, the proposed Evo-Transformer-DRL consistently delivered superior performance compared to the baselines. It achieved 99.19% accuracy, 99.63% recall, and 99.85% AUC on SWAT, which is significantly higher than all competing models. On WADI, the framework obtained 98.67% accuracy, 99.07% recall, and 99.52% AUC, again surpassing both transformer-based and classical approaches. Even on the more challenging BATADAL dataset, Evo-Transformer-DRL maintained strong performance with 98.21% accuracy, 98.73% recall, and 99.14% AUC, whereas models such as CNN and SVM failed to exceed 85%. The ablation analysis also confirmed that while each component (transformer, DRL, and IGWO) individually improved detection, their integration into Evo-Transformer-DRL provided the most substantial and consistent gains.

Beyond detection performance, the framework demonstrated excellent stability and efficiency. Variance values across runs were close to zero (e.g., 0.000005 on SWAT and 0.000092 on BATADAL), indicating robust and repeatable results. Statistical tests further verified that improvements were highly significant, with p-values well below 0.01. In terms of runtime, Evo-Transformer-DRL reached RMSE <15 in 38 seconds, RMSE <6 in 78 seconds, and RMSE <2 in 109 seconds, while none of the baselines managed to meet the strictest error threshold. Convergence curves highlighted that our model stabilized faster and at lower RMSE values than all alternatives, and ROC curves consistently hugged the upper-left boundary, reflecting excellent separability between normal and attack classes. These findings show that the framework not only delivers state-of-the-art accuracy but also ensures stability, efficiency, and real-world practicality for securing Industry 4.0 water infrastructures.