1. Introduction

The detection of small targets in optical remote sensing images has long been recognized as a central challenge in computer vision, constituting both the technical core and a major performance bottleneck across multiple application domains, such as satellite remote sensing [

1,

2,

3], public safety [

4,

5], and target search [

6] applications. With the rapid advancement of deep learning technology in the field of remote sensing, various neural network–based approaches have become the first choice for solving the problem of small target detection.

In the current mainstream deep learning backbone network design, the network architecture generally adopts the design paradigm of layered structure for the technical requirements of small target detection task. According to the different directions of feature transfer, the existing layering schemes can be mainly categorized into two strategies: bottom-up [

7,

8,

9,

10] and top-down [

11,

12,

13,

14].

The bottom-up layering strategy, as the dominant design paradigm, realizes the abstraction from low-level to high-level features through a layer-by-layer feature encoding mechanism. In this strategy, the generation of high-level features is strictly dependent on the output of the preceding layer of features. By following to the paradigm of traditional serial processing, this design has the advantage of being highly structurally interpretable and highly compatible with classical theories of feature description such as hierarchical models of the visual cortex, and has therefore been widely adopted. The top-down hierarchical strategy, on the other hand, mimics the attentional mechanisms of the biological visual system by guiding the underlying feature extraction with high-level semantic information. Although neuroscientific studies have shown that this strategy is closer to the mechanism of human visual perception, such as Gregory's theory of “perceptual hypothesis testing”, it faces significant challenges in engineering practice: the design of this class of models lacks compatibility with modern visual backbone implementation strategies, as some approaches are unsuitable for implementation [

7,

8]. Current practices focus on recursive architectures [

12,

14], whereas recursive operations usually incur additional computational overhead, resulting in a challenging trade-off between performance and computational complexity and thereby constraining their applicability.

Although the bottom-up backbone network structure is computationally efficient, easy to design, and usually provides strong network interpretability, clear feature hierarchy, and smooth semantic transition from low to high levels, it also has notable limitations. High-level features may lose details, and multiple downsampling operations (e.g., pooling) may lead to the omission of small objects or fine-grained information. In addition, the lack of contextual feedback may prevent the high-level semantics from directly influencing the low-level feature extraction, ultimately hindering further performance improvements. Top-down network structures typically require elaborate skip connections or feature fusion mechanisms to ensure effective information flow. In addition, the error feedback of high-level features may interfere with the low-level features, which requires a stable global attention mechanism for guidance for better performance.

In addition, in terms of hierarchical and efficient fusion of features, existing classical frameworks such as FPN [

15] and BiFPN [

16] still face two core challenges. Firstly, the problem of achieving stable cross-level feature scale alignment, ensuring semantic consistency among features at different levels of abstraction. The second lies in balancing computational efficiency and model performance: complex bidirectional interaction mechanisms often introduce considerable computational overhead, and the trade-off between model complexity and detection accuracy of current methods is still significantly deficient, which severely limits the practical applicability of multi-scale target detection—particularly for small target detection.

To address the above challenges, this study proposes a multi-scale small target detection network based on a hybrid bidirectional feature abstraction mechanism, and the main work is as follows:

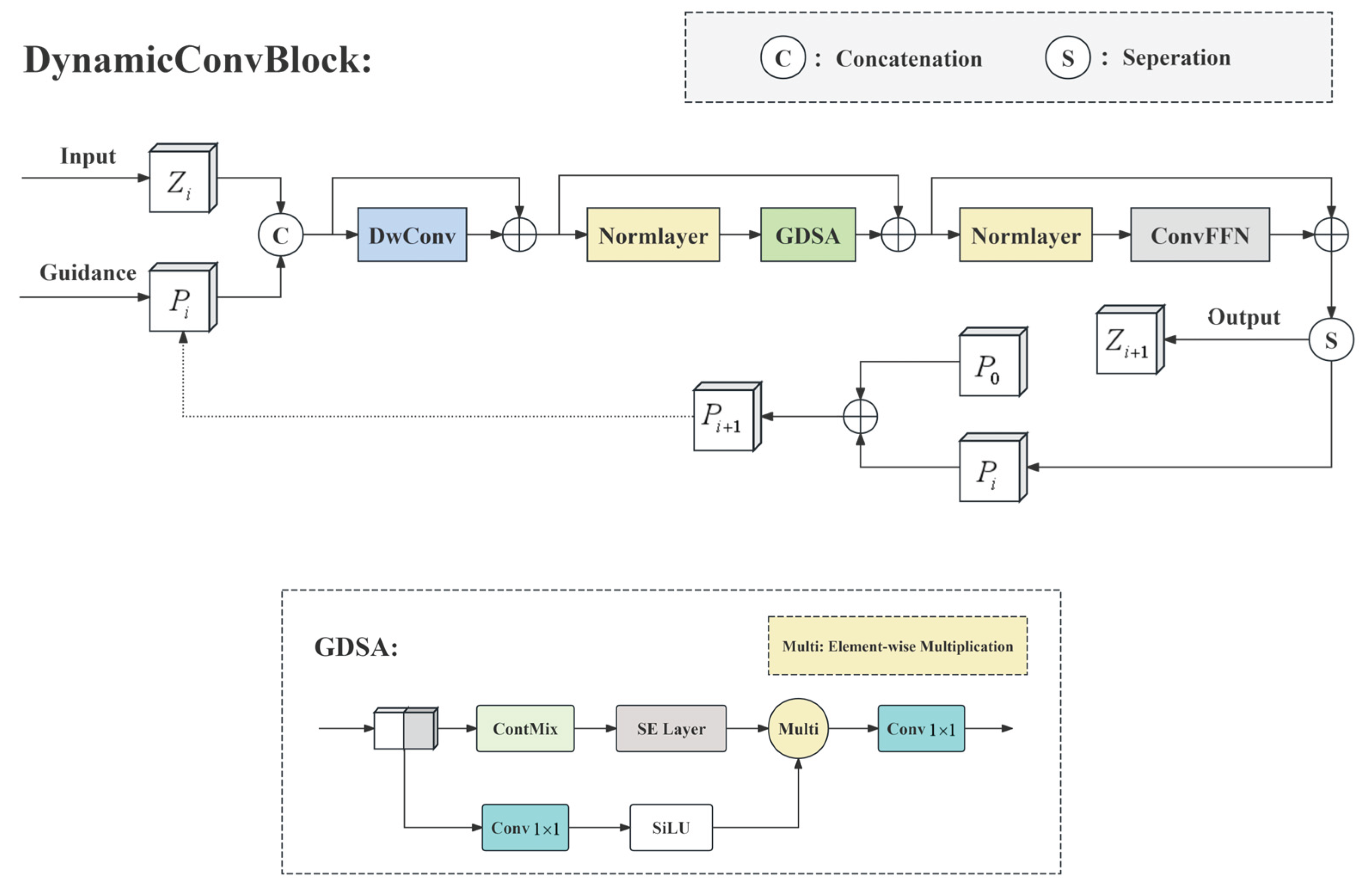

Small target pattern adaptive enhancement: By introducing local adaptive filtering kernels [

17] and combining with the channel attention mechanism, the layer-by-layer enhanced representation of small target patterns is achieved, and feature screening is carried out channel by channel to enhance the stability of small target features.

Weak target pattern adaptive enhancement: The local adaptive enhancement algorithm is introduced to enhance the weak contrast structure of the target and improve the model's ability to learn weak contrast features. Depthwise separable convolution (DWConv) [

18] is integrated to facilitate channel-wise pattern expansion and to filter for beneficial feature channels, ultimately enhancing the structural representation ability of target features.

Detailed feature extraction guided by macroscopic structural features: Drawing on the backbone network of OverLoCK [

16], which utilizes a hierarchical architecture, our method uses macroscopic spatial structural features to guide and align local detailed features crucial for identifying small targets. This creates a feature extraction structure for local small targets that operates under the guidance of macroscopic structural features. This top-down, context-guided approach ensures that local feature extraction is focused on salient regions, improving accuracy and efficiency.

Bidirectional feature propagation architecture: The network achieves bidirectional feature propagation through top-down feature fusion process, where macro-structural characteristics guide detailed feature extraction, and a bottom-up path, realized by the C2f [

19,

20] structure, which abstracts these details. This synergy realizes bidirectional closed-loop feature propagation, multi-scale integration enhanced by combining global semantic reasoning and local fine-grained features, enhancing the environmental adaptability of small target detection.

2. Methods

2.1. Hierarchical Attention Driven Framework

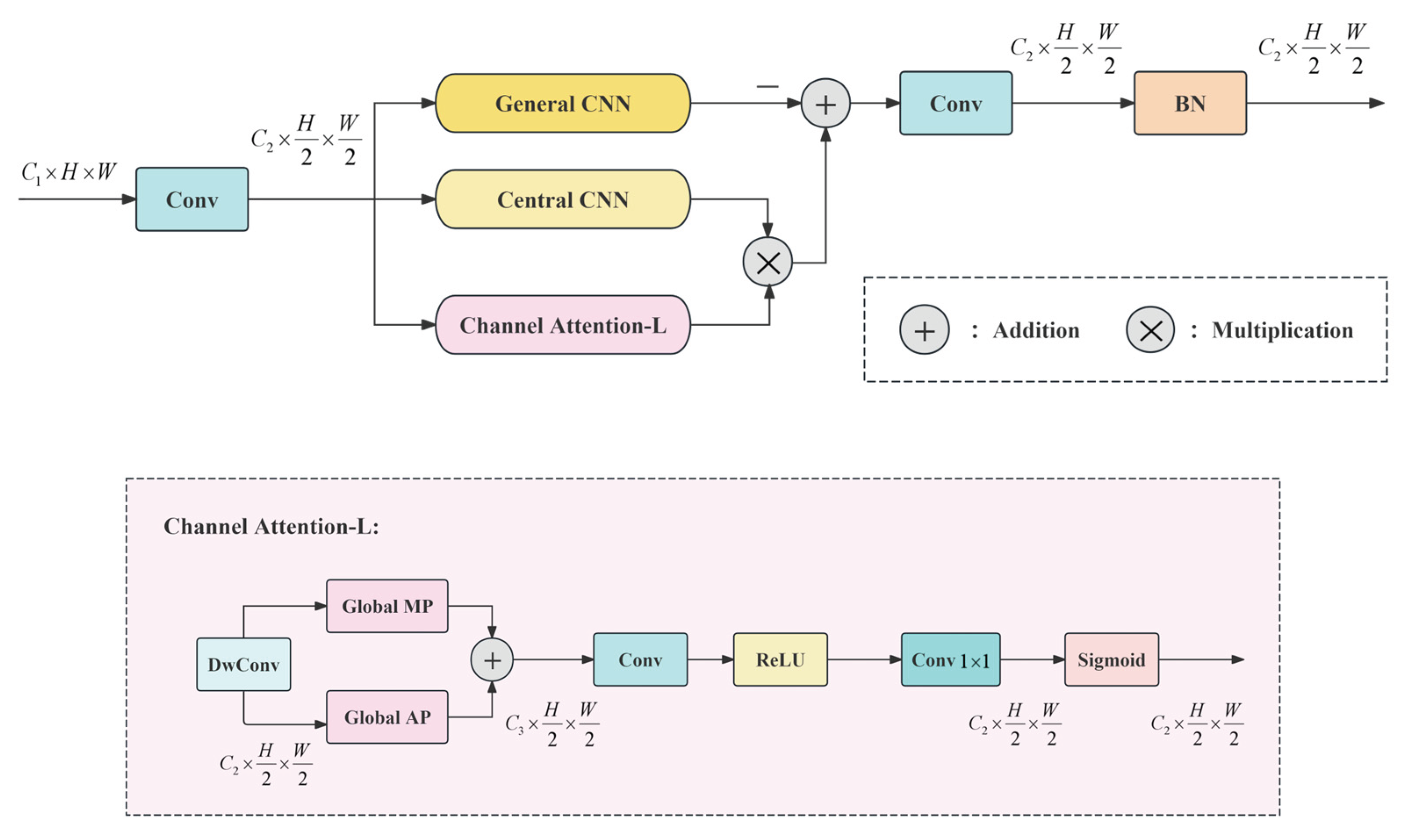

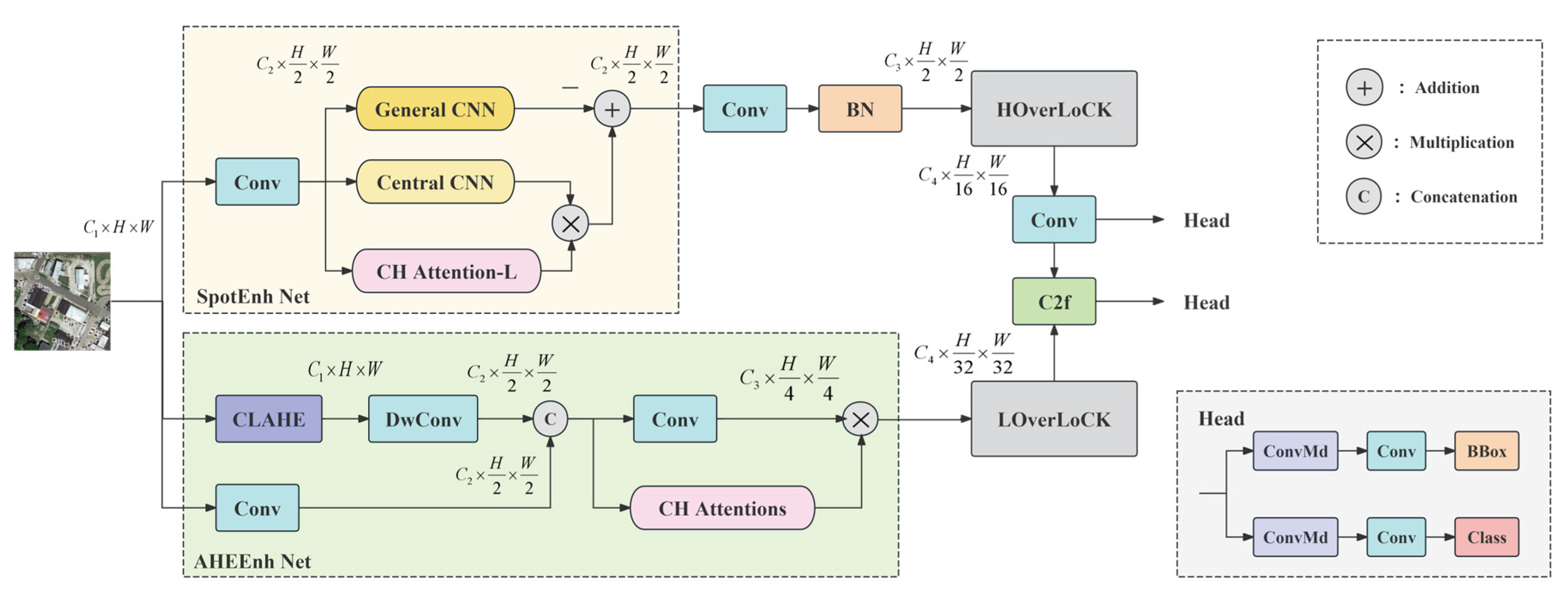

This paper constructs a Hierarchical Attention Driven (HAD) Network, a framework that leverages multi-level attention mechanisms, as shown in

Figure 1. The first stage builds two feature extraction network structures based on pattern rule constraints: SpotEnh Net and AHEEnh Net. To address the feature sparsity of small targets, SpotEnh Net constructs a learnable local adaptive feature enhancement module by statistically analyzing the structural patterns of infrared images. The SpotEnh Net module simulates the effect of Difference-of-Gaussian (DoG) enhancement, thereby strengthening the central-symmetric structure of small targets and increasing the diversity of small target features. Small targets usually have the characteristics of weak information contrast. To address the low contrast and weak gradients of small targets, AHEEnh Net constructs an adaptive gray-level re-projection strategy for local small regions under artificial constraints by statistically analyzing the local gray patterns in a single-layer image, effectively stretches the contrast of gray-scale targets and compensates for their insufficient informational gradient.

To better utilize sparse target features and suppress background interference, a local detail feature extraction module guided by the macroscopic attention mechanism is constructed in the second stage. This module tackles target multi-scale variability through a dual-network architecture: HOverLoCK for high-resolution and LOverLoCK for low-resolution feature extraction. Within the network, features are extracted through the alignment, enhancement, and selection of macroscopic structural features and local detail features, performing top-down extraction of target features. In the multi-scale feature fusion stage, the C2f network structure is integrated to complete the bottom-up fusion pathway from fine-grained features to macroscopic structural features, and the comprehensive bidirectional closed-loop fusion propagation of target features is accomplished in the network.

Finally, the object detection output of the network employs two independent branches for object classification and bounding box regression calculation. The bounding box regression introduces the distribution focal loss (DFL) [

21] and the CIoU structure [

23] to enhance the model's detection accuracy and accelerate convergence.

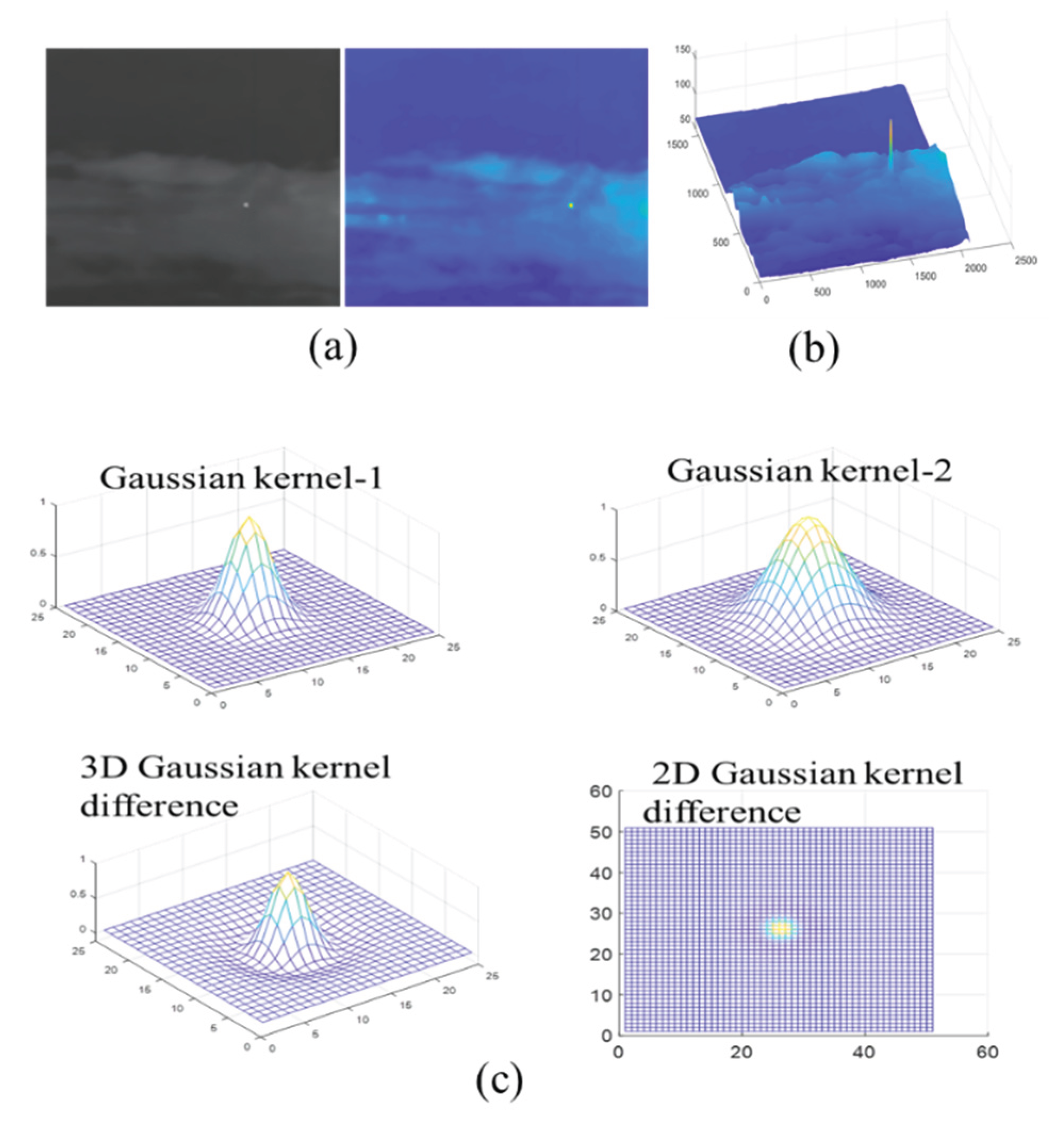

2.2. Pattern Feature Enhancement

The typical characteristics of small targets are weak signal strength and extremely small amount of pixel information for distant targets. Consequently, the critical challenge is to discriminate effective target features within a wide range of gray levels and to identify their limited, weak structural patterns, which is essential for significantly improving target detection rates.

The typical gray-scale features of small goals usually present as ridge-shaped signals, as shown in

Figure 2 (b). Due to their relatively slow changes and weak contrast, it is more challenging to characterize and enhance their patterns. To mitigate these inherent drawbacks of the gray-scale features of small targets, a ridge information response pattern with a central symmetry shape can be obtained by using a two-dimensional Gaussian difference function.

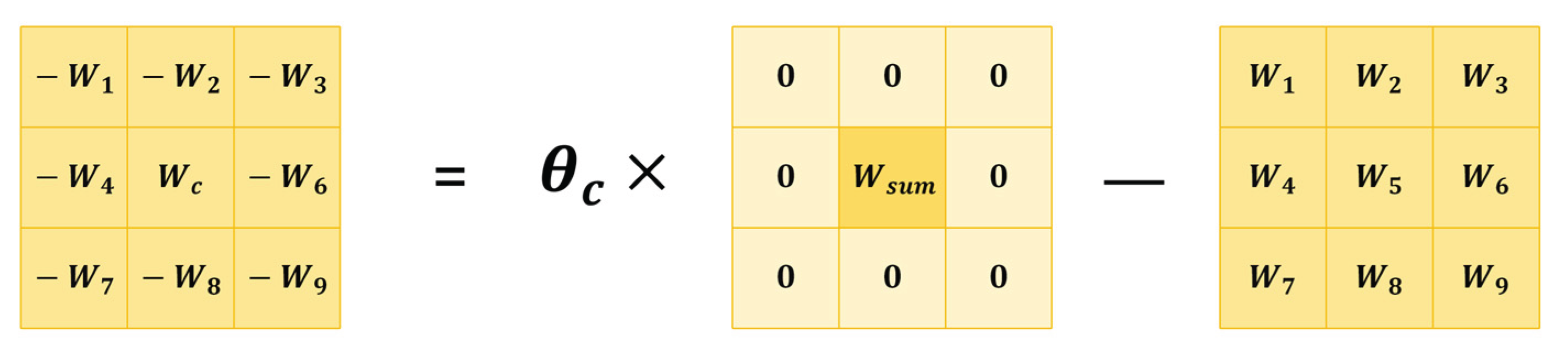

Leveraging the centrosymmetric pattern characteristics of the gray distribution of small targets, we construct a central difference structure as shown in

Figure 3, inspired by L

2SKNet[

22], that mimics a Difference-of-Gaussian (DoG) filter. The central difference structure is aimed to strengthen the isolated feature point information or enhance the saliency of edge information through a fixed difference filtering structure.

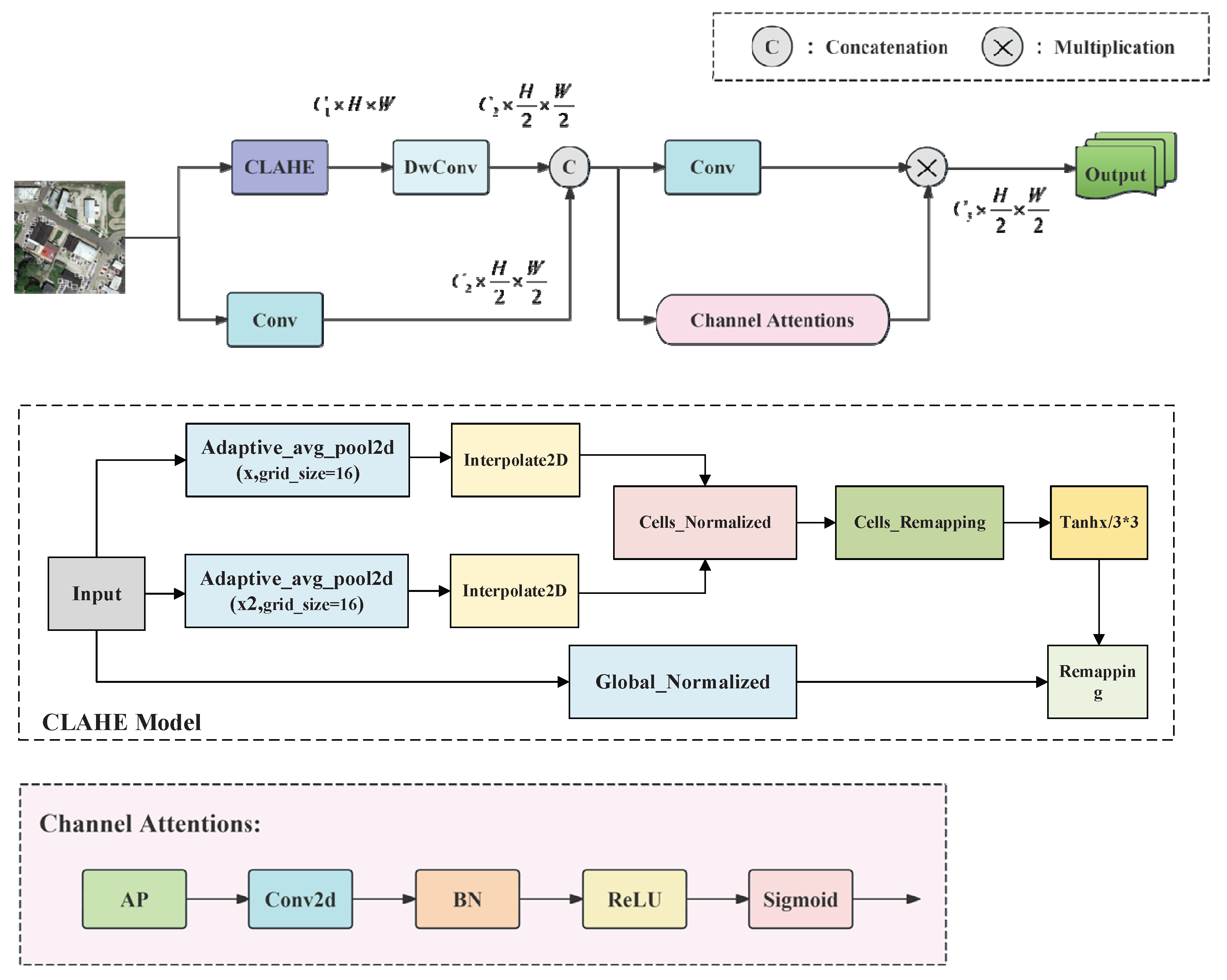

Figure 3.

Central difference enhanced network structure, including the overall structure and the calculation flow of Channel Attention-L.

Figure 3.

Central difference enhanced network structure, including the overall structure and the calculation flow of Channel Attention-L.

Figure 4.

Learnable Gaussian-like centralized filter.

Figure 4.

Learnable Gaussian-like centralized filter.

The reinforcement of the central small target pattern through the network is achieved by reordering the

convolution kernel

in the weight map. Assuming that the learnable parameter kernel in the convolution structure are

, and the matrix core

for constructing the difference filtering structure

is as shown in equation 1.

The enhancement ability of the adaptive filter on the target and the center intensity value of the filter

are closely related. The center weight is adaptively adjusted using the salient channel attention module constructed by Channel Attention. The network specifically captures the spatial features, obtains the amplitude intensity through global MaxPool, obtains the compressed feature distribution through global AvgPool, and finally constructs a global channel saliency intensity in the form of

through fusion and convolution normalization. Finally, it is constrained to [0, 1] by sigmoid [

24] to form the convolutional filter kernel

of the adaptive target pattern within the neighborhood,

achieving adaptive regulation of the center pattern of small targets.

2.3. Gradient Feature Enhancement

Small targets in remote sensing images exhibit weak edge contrast due to atmospheric scattering. In convolutional neural network (CNN)-based detection, the successive convolution operations struggle to stably enhance these targets' structural features and often distort their inherent feature distribution, degrading their representational capacity. To solve this problem, we use net to simulate the CLAHE [

31] (Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization) enhancement strategy. The model, termed the CLAHE model and presented in

Figure 5, enhances weak contrast signals, thereby effectively strengthening the gradient information in local areas.

The AHEEnh Net block first utilizes the CLAHE model to perform local contrast enhancement on the input image. It utilizes the controllable adaptive enhancement within the region, which can meet the need for local contrast amplification while preserving the detailed features of the target edges. The number of channels of the features is constrained through DWConv, and the convolution module is used to achieve the adaptive extraction of the target spatial features. To further preserve the diversity of features, a conventional feature extraction channel is constructed through parallel branches to retain the information strength relationship in the original features and supply the macroscopic strength information of the target features. The outputs of both branches are subsequently fused to produce a rich, comprehensive set of target features.

To conclude, adaptive feature screening is achieved through a channel attention mechanism. Specifically, the AvgPool operation extracts the spatial distribution features, which are then refined by a Conv2d and BN block to accentuate structural details and form spatial attention weights. This design markedly improves the visibility and separability of small target boundaries, rendering it particularly effective in dense small-target scenarios. As a result, the network leverages more distinctive gradient features while preserving the integrity of the original feature distribution.

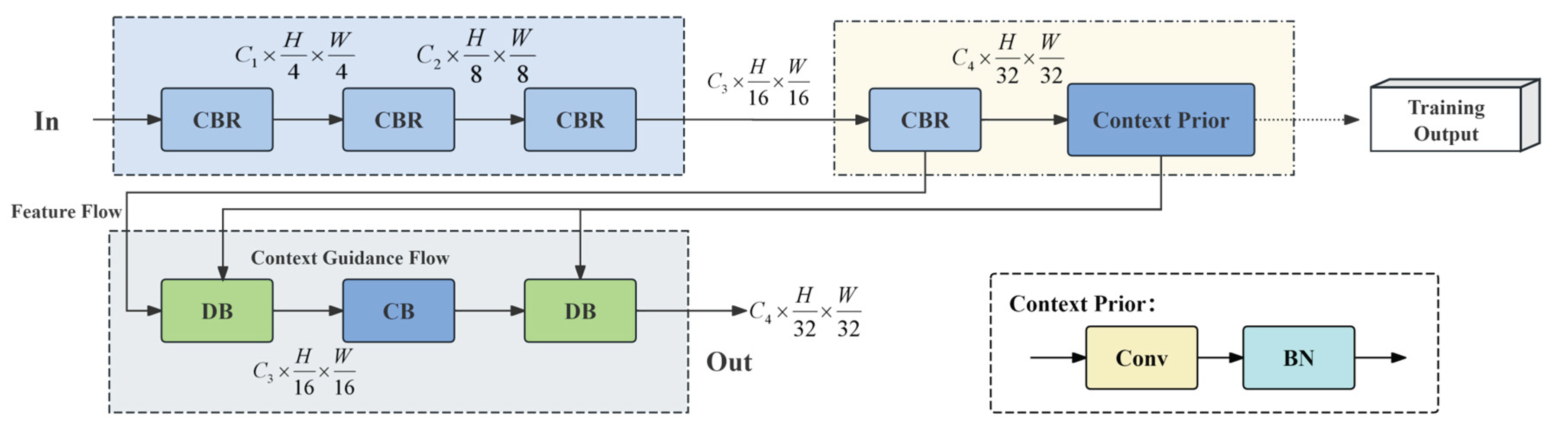

2.4. Marco-Attention Guided Hierarchical Feature Extraction

Target detection in remote sensing imagery faces significant challenges due to large-scale scenes and complex backgrounds. Guiding the network to focus on potential target regions can effectively enhance its target capture capability and improve detection performance. Inspired by the OverLoCK network’s strategy of conducting macro-to-micro analysis during feature extraction, we construct a simplified version of target feature extraction strategy guided by a spatial attention mechanism, as illustrated in

Figure 6. Both the HOverLoCK and LOverLoCK modules share similar structures, consisting of local feature extraction and fusion networks. The HOverLoCK module performs target feature extraction guided by the attention mechanism on high spatial resolution feature maps, while the LOverLoCK is specifically designed for low-resolution global features. The overall network is divided into three functional parts: feature extraction, macroscopic structure extraction, and detailed feature extraction.

3. Experiments

3.1. Datasets

The datasets used in the experiment are the small object datasets AI-TOD [

32] and SODA-A [

33]. The AI-TOD dataset consists of 28,036 images of size 800×800 and 700,621 annotated objects. The average size of the objects in this dataset is 12.8 pixels, with 85.6% of the objects being smaller than 16 pixels. The dataset includes eight major categories: aircraft, bridges, tanks, ships, swimming pools, vehicles, people, and windmills. The entire dataset is randomly divided into three subsets, with 2/5 used for training, 1/10 for validation, and 1/2 for testing. The SODA-A dataset consists of 2,513 images and 872,069 annotated objects, covering nine categories, including aircraft, helicopters, small vehicles, large vehicles, ships, containers, tanks, swimming pools, and windmills. The entire dataset is divided into training, validation, and testing sets, with each subset comprising 1/2, 1/5, and 3/10 of the total dataset.

3.2. Experimental Setup

To validate the effectiveness of the model and ensure the reproducibility of the experimental results, the software environment and system settings parameters used in the experiment are listed in

Table 1.

During the experiment, a learning rate decay method was applied, and 150 epochs of training were uniformly conducted to maintain stability. The training hyper parameters are shown in

Table 2.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

The detection performance of the model is evaluated using average precision (AP) [

34]. For the AI-TOD dataset, the experiment follows the seven evaluation metrics of AI-TOD [

35], namely AP, AP50, AP

vt, AP

t, AP

s, and AP

m. For the SODA-A dataset, AP, AP50, and AP75 are used for evaluation. Among these, AP represents the average of the average precision values under IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 with an interval of 0.05; AP50 and AP75 denote the average precision at IoU thresholds of 0.5 and 0.75, respectively; AP

vt, AP

t, AP

s, and AP

m represent the detection capabilities of different object size models under IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 with intervals of 0.05. Based on the pixel size of the target, the targets to be detected are classified into [

35,

36,

37,

38] very tiny, tiny, small, and medium, to evaluate the multi-scale detection capabilities of the tested models.

4. Results

4.1 Ablation Study

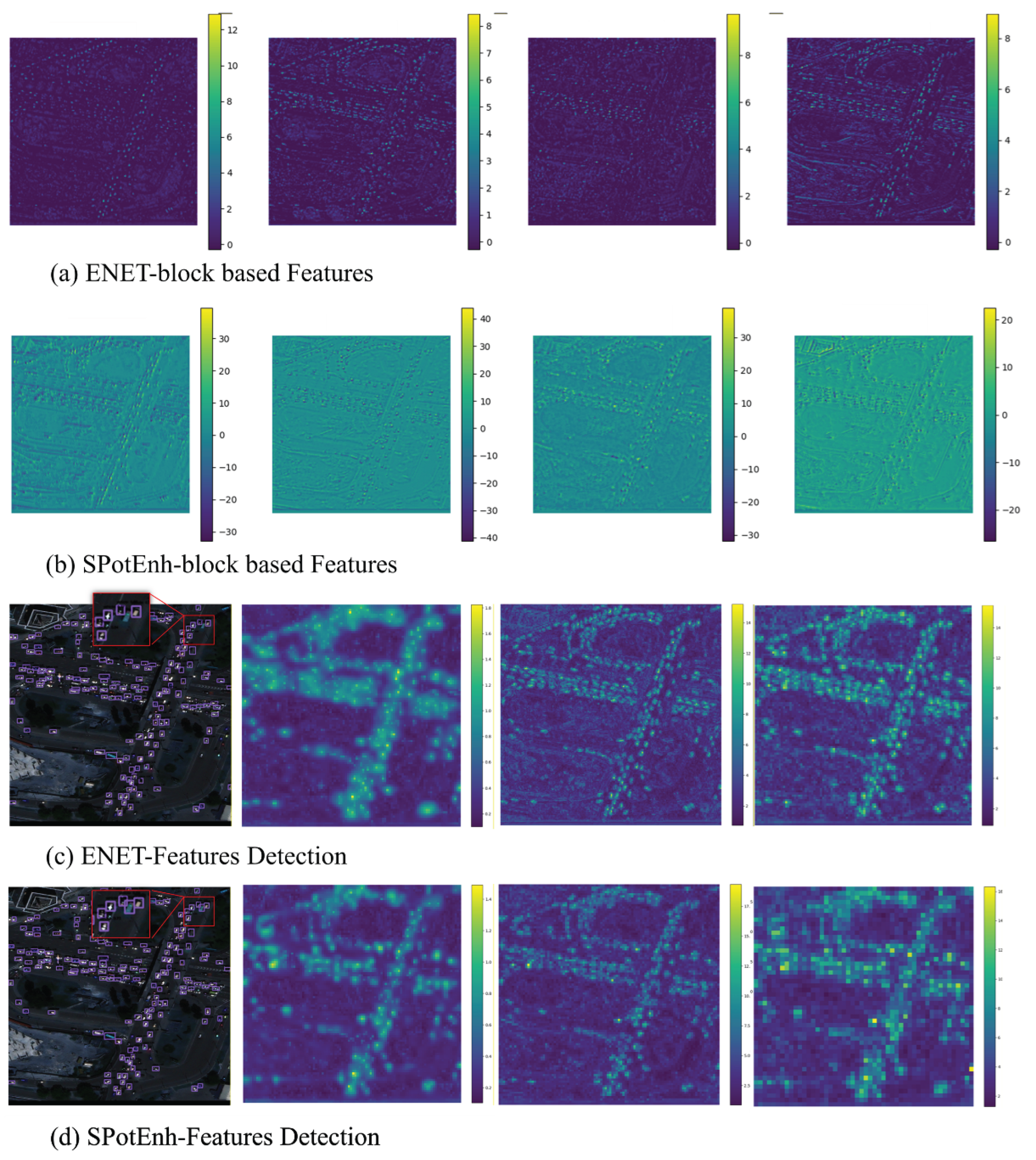

4.1.1. The Effectiveness of the SpotEnh Module

The proposed HAD network employs an adaptive spatial feature extraction strategy guided by local extremum patterns, enriching early feature layers. This design enables dynamic adjustment of local target pattern weights to accommodate different background contexts, thus demonstrating remarkable effectiveness in improving small target detection.

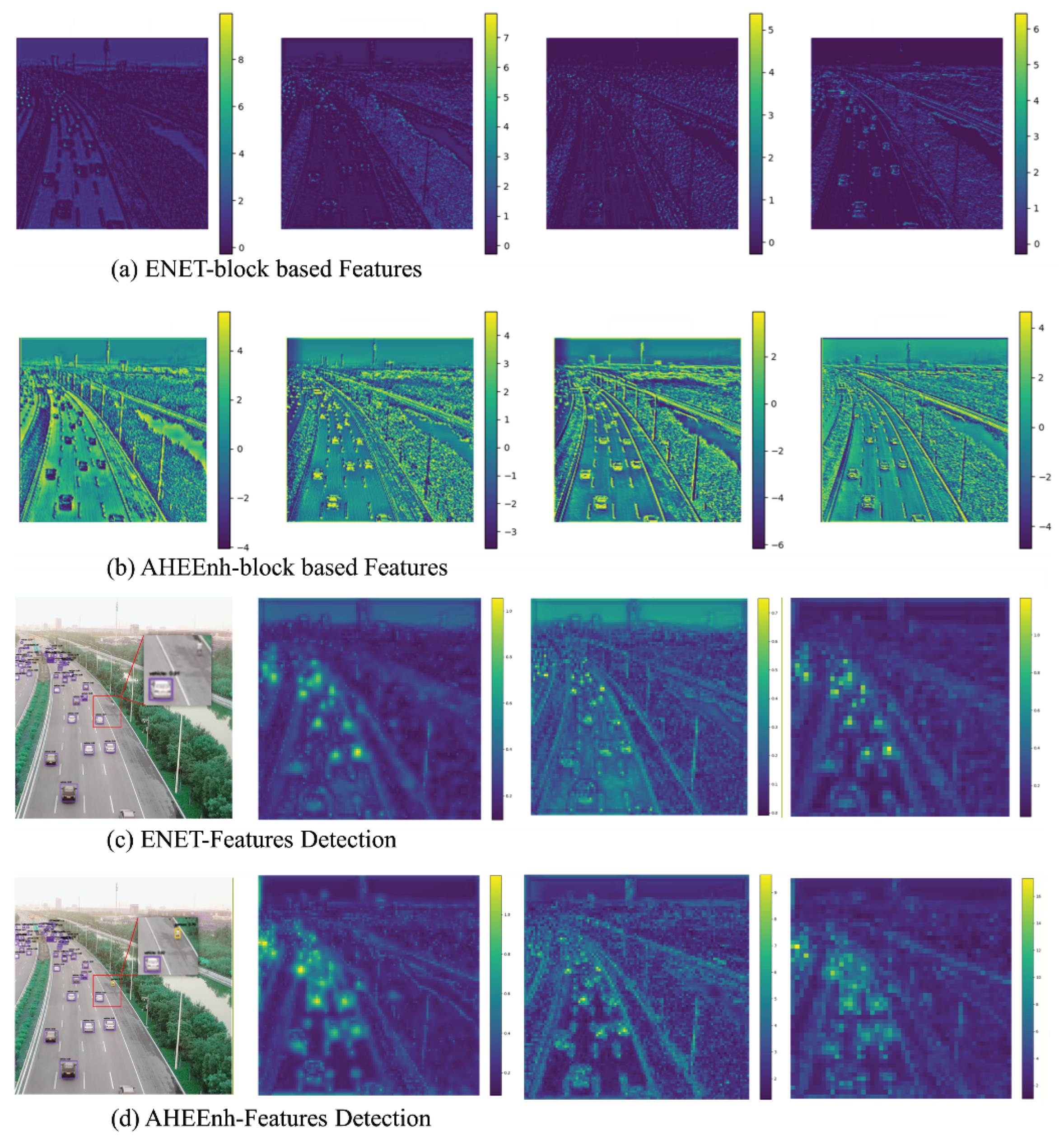

To evaluate the impact of features extracted by the SpotEnh module on the overall network characteristics, we conducted a test by substituting the SpotEnh module with the classical ELAN[

19] structure in the framework, aiming to compare their capabilities in describing small target features. Under identical input, we extracted the intermediate feature layers at specific positions in the modified networks and compared their ability to represent fine details of small targets, as shown in

Figure 10 (a) and (b). Meanwhile, heat maps in columns 2, 3 and 4 in

Figure 10 (c) and (d) present target description ability of aggregating subtle target patterns under varying resolutions. The first column in

Figure 10(c) and (d) display the object detection results, visually illustrating that the network incorporating the SpotEnh module successfully captured tiny cars on the road, whereas the ELAN model based on the residual connection failed to detect these targets.

4.1.2. The Effectiveness of the AHEEnh Module

The AHEEnh Module incorporates a rule-based gradient learning structure that simulates local adaptive contrast enhancement [

31]. This module enhances the edge contrast of weak and small targets, thereby enriching their feature representation. It particularly improves the targets’ structure in densely distributed, which facilitates more effective feature selection in subsequent attention mechanisms.

To validate the effectiveness of the AHEEnh module within the overall framework, we conducted a replacement experiment by substituting it with the classical ELAN structure, comparing the impact of different modules on feature extraction in target regions. As shown in

Figure 11(a) and (b), the proposed AHEEnh module significantly enhances the contrast of faint target boundaries, thereby improving target specificity and resulting in more salient feature representation. By utilizing heatmaps to analyze the energy distribution in target areas, the experiment in

Figure 11(c) and (d) demonstrate the crucial role of the module in aggregating features of weak and small target patterns.

4.1.3. Abletion Experiment

To further evaluate the impact of the SpotNet’s performance, we conducted a comparative experiment on the AI-TOD dataset. As shown in

Table 3, the network incorporating the SpotEnh module demonstrates a better capacity for capturing targets across various scales. The enhancement is particularly pronounced for tiny objects, with an increase of 0.9%. Additionally, enhancements were observed in AP

vt and AP

s, which improved by 0.1% and 0.3%, respectively. The AHEEnh module enhance discriminative capability in target regions, this enhancement module possesses a stronger capacity for capturing gradient information from local small object features. This leads to further improvements in detection performance across object scales, as evidenced by increases of 0.1% in AP

vt, 0.5% in AP

t, and 0.1% in AP

s.

Additionally, our network employs a C2f module to fuse multi-scale features, capitalizing on their distinct properties: high-resolution features for fine-grained localization and low-resolution features for robust semantics. We utilize bidirectional fusion to merge these strengths, where top-down propagation boosts localization precision and bottom-up propagation refines semantic content. We refer to the bidirectional feature fusion framework as BI-FF (short for Bidirectional Feature Fusion). This design has been proved to enhance the fusion of data features across the model, boosting detection performance for objects at various scales.

A collaborate version was constructed to evaluate this strategy. This modified architecture processes high and low-resolution features separately through the C2f module, bypassing the mutual cross-resolution integration. As evidenced by the detection metrics in

Table 3, the proposed bidirectional feature fusion strategy—which first gathers features from distinct branches—drives a substantial boost in model capability. This advance is demonstrated not only in the reliable detection of targets at various scales but also in the model's increased stability, indicating comprehensive performance gains.

4.2. Comprehensive Comparison

4.2.1. Qualitative Comparison

To demonstrate the enhanced sensitivity for small object detection, several cases were randomly selected here to compare the effects of contrast enhancement and small object center structure enhancement on detection results. As shown in

Figure 10, the model’s detection performance is compared by replacing the AHEEnh Net with the ELAN module. The left side of the figure shows the model performance without the CLAHE component, while the right side shows the results of the complete model proposed in this paper. In areas where targets are densely distributed and the contrast between targets and background is relatively weak, effective target information is easily overwhelmed by background information, thereby making stable detection challenging. By integrating the AHEEnh model, the model leverages the nonlinear stretching capability of statistical rules in contrast enhancement to effectively stretch the local contrast of small targets, thereby enhancing the saliency of spatial features. Combined with an attention mechanism, this approach achieves more stable detection of small targets.

For small target detection tasks, the introduced SpotEnh structure has good information enhancement capabilities for the central extreme structure features of small targets at long distances. A series of comparative detection results were carried out to verify the effect of enhancing long-range central structural features on target detection. As shown in

Figure 11: the ELAN-enhanced version (left) versus the SpotEnh Net (right).

Integrating a locally adaptive enhancement rule, the AHEEnh simulation network adaptively stretches image contrast based on local grayscale distribution. This effectively enhances the feature specificity of small targets with weak edges, while its adaptive parameters prevent over-stretching artifacts (e.g., ringing) in flat regions. Collectively, it improves the model's discriminative capability for small targets in dense scenes.

4.2.2. Quantitative Comparison

The performance comparison results of the proposed model with classical object detection models on the AI-TOD dataset are shown in

Table 4. The proposed model achieves an AP of 21.4%, significantly outperforming other models, and also performs best in terms of AP50, AP

t, and AP

s. Compared to traditional feature pyramid-based multi-scale object detection frameworks, the proposed model demonstrates superior overall stability. When compared to classical detection networks based on Transformers [

39], the proposed model also maintains its performance advantages. Compared to the hierarchical feature pyramid and adaptive receptive field optimization in the MAV23[

40] backbone network, the AP of this small object detection model is still 4.2% higher; compared to ADAS-GPM [

41], the AP is 1.3% higher; and compared to SAFF-SSD [

42] using 2L-Transformer [

39], the AP is 0.3% higher. The model employs a hierarchical attention mechanism to construct a bidirectional feature learning path, achieving comprehensive fusion of multi-scale features. Additionally, the specifically designed small object feature enhancement network and low-contrast structural feature extraction network both provide effective auxiliary enhancements.

Table 4.

Comparison of different models on the AI-TOD dataset.

Table 4.

Comparison of different models on the AI-TOD dataset.

| Method |

Publication |

AP |

AP0.5 |

APvt |

APt |

APs |

APm |

| Faster R-CNN[43] |

2015 |

11.6 |

26.9 |

0.0 |

7.8 |

24.4 |

34.1 |

| SSD-512[42] |

2016 |

7.0 |

21.7 |

1.0 |

5.4 |

11.5 |

13.5 |

| RetinaNet[44] |

2017 |

4.7 |

13.6 |

2.0 |

5.4 |

6.3 |

7.6 |

| Cascade R-CNN[45] |

2018 |

13.7 |

30.5 |

0.0 |

9.9 |

26.1 |

36.4 |

| TridentNet[46]] |

2019 |

7.5 |

20.9 |

1.0 |

5.8 |

12.6 |

14.0 |

| ATSS[47] |

2020 |

14.0 |

33.8 |

2.2 |

12.2 |

21.5 |

31.9 |

| M-CenterNet[48] |

2021 |

14.5 |

40.7 |

6.1 |

15.0 |

19.4 |

20.4 |

| FSANet[49] |

2022 |

16.3 |

41.4 |

4.4 |

14.6 |

23.4 |

33.3 |

| FCOS[50] |

2022 |

13.9 |

35.5 |

2.7 |

12.0 |

20.2 |

32.2 |

| NWD[51] |

2022 |

19.2 |

48.5 |

7.6 |

19.0 |

23.9 |

31.6 |

| DAB-DETR[52] |

2022 |

4.9 |

16.0 |

1.7 |

3.6 |

7.0 |

18.0 |

| DAB-Deformable-DETR[53] |

2022 |

16.5 |

42.6 |

7.9 |

15.2 |

23.8 |

31.9 |

| MAV23[40] |

2023 |

17.2 |

47.7 |

8.9 |

18.1 |

21.2 |

28.4 |

| ADAS-GPM[41] |

2023 |

20.1 |

49.7 |

7.4 |

19.8 |

24.9 |

32.1 |

| SAFF-SSD[42] |

2023 |

21.1 |

49.9 |

7.0 |

20.8 |

30.1 |

38.8 |

| YOLOv8s |

2023 |

11.6 |

27.4 |

3.4 |

11.1 |

14.9 |

22.8 |

| Ours |

- |

21.4 |

51.6 |

7.8 |

23.3 |

31.3 |

33.4 |

Compared with the classic feature pyramid convolution model in the field and the Transformer framework based on PVT[

54] and its variants, the object detection accuracy of the model in this paper still has a significant advantage overall on the SODA-A dataset.

Table 4.

Comparison of different models on the SODA-A dataset.

Table 4.

Comparison of different models on the SODA-A dataset.

| Method |

Publication |

AP |

AP0.5 |

AP0.75 |

| Rotated Faster RCNN[42] |

2017 |

32.5 |

70.1 |

24.3 |

| RoI Transformer[39] |

2019 |

36.0 |

73.0 |

30.1 |

| Rotated RetinaNet[44] |

2020 |

26.8 |

63.4 |

16.2 |

| Gliding Vertex[54] |

2021 |

31.7 |

70.8 |

22.6 |

| Oriented RCNN[45] |

2021 |

34.4 |

70.7 |

28.6 |

| S2A-Net[55] |

2022 |

28.3 |

69.6 |

13.1 |

| DODet[56] |

2022 |

31.6 |

68.1 |

23.4 |

| Oriented RepPoints[57] |

2022 |

26.3 |

58.8 |

19.0 |

| DHRec[58] |

2022 |

30.1 |

68.8 |

19.8 |

| M2Vdet[59] |

2023 |

37.0 |

75.3 |

31.4 |

| CFINet[60] |

2023 |

34.4 |

73.1 |

26.1 |

| YOLOv8s |

2023 |

40.6 |

72.1 |

40.6 |

| Ours |

- |

43.2 |

76.7 |

45.7 |

The classic feature pyramid convolution structure represented by the YOLOv8s has limited capability for detecting small, dense objects, primarily due to the resolution limitations of spatial feature maps, which restrict their descriptive power. Gradient information within the framework accumulates and degrades as it propagates through the network, gradually weakening its ability to express high-resolution features of small objects. In contrast, models based on the ConvFFN module with SpotEnh and AHEEnh branches, which enhance their spatial feature extraction through macro-structure attention mechanisms, demonstrate superior small-object discrimination. The model proposed in this paper effectively integrates the multi-path feature attention mechanism to achieve bidirectional feature fusion from top-down and bottom-up directions. Additionally, the model incorporates statistical constraints from statistical machine learning, combining attention weight-guided spatial feature extraction to achieve robust small object detection capabilities, resulting in more comprehensive information integration across the entire network. This enables the model to demonstrate more stable performance in multi scale object detection tasks.

5. Conclusions

To address the challenges posed by the tiny size and sparse features of targets in small object remote sensing, this paper proposes a network that incorporates multi-scale feature fusion and enhancement. Firstly, the SpotEnh model and AHEEnh model are introduced to enhance the structural features and weak contrast features of small spatial targets, respectively. Secondly, a top-down attention mechanism that first performs a rough scan and then refines the details is used to achieve guided feature extraction of regional targets, thereby strengthening the spatial search and macro representation capabilities of small targets. Finally, a bottom-up feature fusion strategy is employed to fuse micro-level features and macro-level structural features, thereby enhancing the descriptive capability of small object features and improving the network's object detection stability. Experimental results demonstrate that, compared to classical small object detection models, the proposed model achieves significant performance advantages on two standard small object datasets. On the AI-TOD dataset, the proposed model achieved improvements of 0.3% in AP and 0.7% in AP0.5 over the benchmark models. While on the SODA-A dataset, AP and AP0.5 improved by 2.6% and 1.4%, respectively. These gains confirm the effectiveness of the model in enhancing small-object detection performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Xiongwei Sun and Xinyu Liu; methodology, Xiongwei Sun and Xinyu Liu; software, Xiongwei Sun; validation, Xiongwei Sun and Jile Wang; formal analysis, Xiongwei Sun and Jile Wang; investigation, Xinyu Liu and Jile Wang; resources, Xiongwei Sun and Jile Wang; data curation, Jile Wang; writing—original draft preparation, Xinyu Liu; writing—review and editing, Xinyu Liu, Xiongwei Sun, and Jile Wang; visualization, Xiongwei Sun and Jile Wang; supervision, Xiongwei Sun; project administration, Xinyu Liu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Zhongke Technology Achievement Transferand Transformation Center of Henan Province, Project Number: 20251 14.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

I extend my sincere thanks to my friends, FeiLi and Zhiyuan Xi, for their essential help with data collection and organization. I am also deeply grateful to my family for their steadfast support and encouragement throughout this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, manuscript preparation, or decision to publish.

References

- LI, K; WAN, G; CHENG, G; MENG, L; HAN, J. Object detection in optical remote sensing images: a survey and a new benchmark[J/OL]. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2020, 159, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X; Zhu, H; Zhao, Y; Chen, J; Wei, T; Huang, Z. A small ship object detection method for satellite remote sensing data[J]. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbi, J.; Ray, N.; Schubert, M.; Chowdhury, S.; Chao, D. Small-object detection in remote sensing images with end-to-end edge-enhanced GAN and object detector network[J]. Remote Sensing 12(9), 1432.

- LIU, Z; YUAN, L; WENG, L; YANG, Y. A high resolution optical satellite image dataset for ship recognition and some new baselines[C/OL]. ICPR, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- WANG, J; CHEN, K; YANG, S; LOY, C C; LIN, D. Region proposal by guided anchoring[C/OL]. CVPR, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- YANG, X; SUN, H; FU, K; YANG, J; SUN, X; YAN, M; GUO, Z. Automatic ship detection in remote sensing images from Google Earth of complex scenes based on multiscale rotation dense feature pyramid networks[J/OL]. Remote Sensing 2018, 10(1), 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANDERSON, P; HE, X; BUEHLER, C; TENEY, D; JOHNSON, M; GOULD, S; ZHANG, L. Bottom-up and top-down attention for image captioning and visual question answering[C/OL]. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018; pp. 6077–6086. [Google Scholar]

- CHEN, H; SUN, K; TIAN, Z; SHEN, C; HUANG, Y; YAN, Y. Blendmask: top-down meets bottom-up for instance segmentation[C/OL]. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2020; pp. 8573–8581. [Google Scholar]

- CHEN, H; CHU, X; REN, Y; ZHAO, X; HUANG, K. Pelk: parameter-efficient large kernel convnets with peripheral convolution[C/OL]. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- CHEN, Y; DAI, X; LIU, M; CHEN, D; YUAN, L; LIU, Z. Dynamic convolution: attention over convolution kernels[C/OL]. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2020; pp. 11030–11039. [Google Scholar]

- CAO, C; LIU, X; YANG, Y; YU, Y; WANG, J; WANG, Z; et al. Look and think twice: capturing top-down visual attention with feedback convolutional neural networks[C/OL]. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 2015; pp. 2956–2964. [Google Scholar]

- CAO, C; HUANG, Y; YANG, Y; WANG, L; WANG, Z; TAN, T. Feedback convolutional neural network for visual localization and segmentation[J/OL]. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2018, 41(7), 1627–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DING, X; ZHANG, X; HAN, J; DING, G. Scaling up your kernels to 31x31: revisiting large kernel design in CNNs[C/OL]. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022; pp. 11963–11975. [Google Scholar]

- LIN, T Y; DOLLÁR, P; GIRSHICK, R; HE, K; HARIHARAN, B; BELONGIE, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection[C/OL]. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TAN, M; PANG, R; LE, Q V. EfficientDet: scalable and efficient object detection[C/OL]. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2020; pp. 10778–10787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LOU, M; YU, Y. OverLoCK: an overview-first-look-closely-next ConvNet with context-mixing dynamic kernels[EB/OL]. arXiv. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.20087v2.

- ZHANG, X; LI, Y; WANG, Z; CHEN, J. Saliency at the helm: steering infrared small target detection with learnable kernels (L²SKNet)[J/OL]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- HOWARD, A G; ZHU, M; CHEN, B; KALENICHENKO, D; WANG, W; WEYAND, T; et al. MobileNets: efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications[EB/OL]. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar]

- WANG, C-Y; BOCHKOVSKIY, A; LIAO, H-Y M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors[EB/OL]. arXiv. 2022. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2207.02696.

- LI, X; WANG, W; HU, X; YANG, J. C2f module: a cross-stage partial fusion approach for efficient object detection[EB/OL]. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.12345. [Google Scholar]

- LI, X; WANG, W; WU, L; CHEN, S; HU, X; LI, J; et al. Generalized focal loss: learning qualified and distributed bounding boxes for dense object detection[C/OL]. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2020, 33, 21002–21012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WU, F; LIU, A; ZHANG, T; ZHANG, L; LUO, J; PENG, Z. Saliency at the Helm: Steering Infrared Small Target Detection With Learnable Kernels[J/OL]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2025, 63, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHENG, Z; WANG, P; LIU, W; LI, J; YE, R; REN, D. Distance-IoU loss: faster and better learning for bounding box regression[C/OL]. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2020, 34(07), 12993–13000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VERHULST, P F. Recherches mathématiques sur la loi d'accroissement de la population [Mathematical researches into the law of population growth][J/OL]. Nouveaux Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences et Belles-Lettres de Bruxelles 1845, 18, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHEN, Y; LI, Z; ZHANG, H; WANG, X. Dilated reparameterized convolution for multi-scale feature fusion[C/OL]. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2023; pp. 12345–12355. [Google Scholar]

- HUA, W; DAI, Z; LIU, H; LE, Q V. Dynamic feature gating with global response normalization[C/OL]. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2022, 35, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar]

- ELFWING, S; UCHIBE, E; DOYA, K. Sigmoid-weighted linear units for neural network function approximation[J/OL]. Neural Networks 2018, 97, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG, Z; ZHANG, X; PENG, C; XUE, X; SUN, J. Context-aware mixing for data-efficient object detection[J/OL]. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2021, 44(8), 4567–4581. [Google Scholar]

- WU, H; XIAO, B; CODELLA, N; LIU, M; DAI, X; YUAN, L; et al. ConvFFN: convolutional feed-forward networks for vision tasks[C/OL]. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2021. [Google Scholar]

- VASWANI, A; SHAZEER, N; PARMAR, N; USZKOREIT, J; JONES, L; GOMEZ, A N; et al. Attention is all you need[C/OL]. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- ZUIDERVELD K. Contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization[M/OL]//HECKBERT P S (Ed.). Graphics Gems IV. Academic Press, 1994: 474-485.

- XU, Y; FU, M; WANG, Q; WANG, Y; CHEN, K; XIA, G S; et al. AI-TOD: a benchmark for tiny object detection in aerial images[J/OL]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG, J; HUANG, J; LI, X; ZHANG, Y. SODA-A: a large-scale small object detection benchmark for autonomous driving[C/OL]. European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2022; pp. 456–472. [Google Scholar]

- EVERINGHAM, M; VAN GOOL, L; WILLIAMS, C K I; WINN, J; ZISSERMAN, A. The Pascal Visual Object Classes (VOC) challenge[J/OL]. International Journal of Computer Vision 2010, 88(2), 303–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XU, Y; FU, M; WANG, Q; et al. AI-TOD: a benchmark for tiny object detection in aerial images[J/OL]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- YANG, X; YANG, J; YAN, J; ZHANG, Y; ZHANG, T; GUO, Z; et al. SCRDet++: detecting small, cluttered and rotated objects via instance-level feature denoising and rotation loss smoothing[J/OL]. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2021, 44(6), 3155–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KISANTAL, M; WOJNA, Z; MURAWSKI, J; NARUNIEC, J; CHO, K. Augmentation for small object detection[EB/OL]. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.07296. [Google Scholar]

- LIN, T Y; MAIRE, M; BELONGIE, S; HAYS, J; PERONA, P; RAMANAN, D; et al. Microsoft COCO: common objects in context[C/OL]. European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- CARION, N; MASSA, F; SYNNAEVE, G; et al. End-to-end object detection with transformers[C/OL]. European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- WANG, L; LU, Y; WANG, Y; ZHENG, Y; YE, X; GUO, Y. MAV23: a multi-altitude aerial vehicle dataset for tiny object detection[C/OL]. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- LIU, S; QI, L; QIN, H; et al. ADAS-GPM: attention-driven adaptive sampling for ground penetrating radar object detection[J/OL]. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2022, 24(3), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- LI, J; LIANG, X; WEI, Y; et al. SAFF-SSD: spatial attention feature fusion for single-shot detector[J/OL]. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2021, 30, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar]

- REN, S; HE, K; GIRSHICK, R; SUN, J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks[C/OL]. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2015, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIN, T Y; GOYAL, P; GIRSHICK, R; HE, K; DOLLÁR, P. Focal loss for dense object detection[C/OL]. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- CAI, Z; VASCONCELOS, N. Cascade R-CNN: delving into high quality object detection[C/OL]. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2018. [Google Scholar]

- LI, Y; CHEN, Y; WANG, N; ZHANG, Z. Scale-aware trident networks for object detection[C/OL]. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG, S; CHI, C; YAO, Y; et al. Bridging the gap between anchor-based and anchor-free detection via adaptive training sample selection[C/OL]. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WANG, J; CHEN, K; XU, R; et al. M-CenterNet: multi-scale CenterNet for tiny object detection[J/OL]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- YANG, F; CHOI, W; LIN, Y. FSANet: feature-and-scale adaptive network for object detection[C/OL]. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- TIAN, Z; SHEN, C; CHEN, H; HE, T. FCOS: fully convolutional one-stage object detection[C/OL]. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- YANG, X; YAN, J; MING, Q; et al. Rethinking the evaluation of object detectors via normalized Wasserstein distance[C/OL]. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2021. [Google Scholar]

- LIU, S; LI, F; ZHANG, H; et al. DAB-DETR: dynamic anchor boxes for transformer-based detection[C/OL]. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2022. [Google Scholar]

- LIU, S; et al. Deformable DETR with dynamic anchor boxes[EB/OL]. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.12345. [Google Scholar]

- XU, Y; FU, M; WANG, Q; WANG, Y; CHEN, K. Gliding vertex for oriented object detection[C/OL]. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- HAN, J; DING, J; XUE, N; XIA, G S. S2A-Net: scale-aware feature alignment for oriented object detection[J/OL]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- CHEN, L; ZHANG, H; XIAO, J; et al. DODet: dual-oriented object detection in remote sensing images[C/OL]. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2022. [Google Scholar]

- YANG, X; YAN, J; YANG, X; et al. Oriented RepPoints for aerial object detection[C/OL]. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2021. [Google Scholar]

- WANG, Z; HUANG, J; LI, X; ZHANG, Y. DHRec: dynamic hierarchical representation for tiny object detection[C/OL]. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- LI, R; ZHENG, S; DUAN, C; et al. M2Vdet: multi-view multi-scale detection for UAV imagery[J/OL]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG, H; WANG, Y; DAYOUB, F; SÜNDERHAUF, N. CFINet: contextual feature interaction for tiny object detection[C/OL]. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2023. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).