1. Introduction

Neonatal arrhythmias (NA), although relatively uncommon, constitute a group of disorders that may lead to severe clinical consequences. The prevalence in the neonatal population has been reported to range from 1% to 5% [

1,

2]. Neonatal arrhythmias may arise from various systemic and cardiovascular causes. Clinical manifestations vary widely, from asymptomatic presentations to severe cases complicated by congestive heart failure, and may occasionally be observed as early as the fetal period [

3].

Neonatal arrhythmias can be classified into two categories: benign and non-benign. Benign arrhythmias include premature atrial contractions (PACs), premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, and junctional rhythms. Non-benign arrhythmias include supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), atrial flutter (AF), ventricular tachycardia (VT), ventricular fibrillation, second- or third-degree AV block, and long QT syndrome [

4,

5].

Although non-benign arrhythmias are less common than benign arrhythmias, they require early diagnosis and treatment. Although morbidity and mortality rates are higher in this group, the prognosis is generally favorable with appropriate treatment. However, some types of arrhythmias may require long-term antiarrhythmic therapy [

6,

7,

8].

This study aims to evaluate the types, frequency, clinical presentations, risk factors, treatment options, prognosis, recurrence rates, morbidity, and mortality outcomes of neonatal arrhythmias.

2. Materials and Methods

This single-center retrospective study was conducted at Basaksehir Cam and Sakura City Hospital between January 1, 2021, and May 1, 2025. The study population included neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit and managed by the Pediatric Cardiology Department, as well as outpatients who presented to the pediatric cardiology clinic, all of whom were diagnosed with arrhythmia within the first 28 days of life. Patients who developed arrhythmias in the postoperative period and those with neurological or metabolic diagnoses were excluded from the study.

Neonatal arrhythmias were classified as benign and non-benign arrhythmias. Premature atrial contractions (PACs), premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), and first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block were classified as benign arrhythmias. Frequent (>10% in 24 hours), aberrantly conducted or nonconducted PACs requiring medical treatment, and frequent (>10% in 24 hours), couplet or triplet PVC requiring medical treatment, second- or third-degree AV blocks, and long QT syndrome were classified as non-benign arrhythmias.

Patients’ 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECGs), 24-hour Holter ECG recordings, echocardiograms, presence of prenatal diagnosis, gestational age, birth weight, complaints, genetic investigations, family histories, treatments administered, follow-up periods, and responses to treatment during this period were examined.

Electrocardiography was performed using a Philips PageWriter Trim II device with 12 leads, a speed of 25 mm/s, and an amplitude of 10 mm/mV. Tachycardia was defined as a heart rate at or above the 95th percentile according to age-specific standard values. 12-lead ECG and 24-hour Holter ECG recordings were used in the classification of arrhythmias.

The echocardiographic assessment was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography. All patients were evaluated for the presence of concomitant congenital heart disease. A shortening fraction of <28% or an ejection fraction of <55% was considered an indicator of systolic dysfunction. Patients with a left ventricular end-diastolic diameter z-score > +2 and systolic dysfunction were classified as having dilated cardiomyopathy.

The study was approved by the Basaksehir Cam ve Sakura Ethics Committee on December 23, 2022, under the number 2022.12.413. Informed consent forms were obtained from the parents of all patients included in the study.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test was applied for continuous variables. Variables showing a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation, while those not showing a normal distribution are presented as median (interquartile range). Variables with p<0.20 in univariate analysis were included in the stepwise logistic regression model. Model fit was assessed, and odds ratios are presented with 95% confidence intervals. In all analyses, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

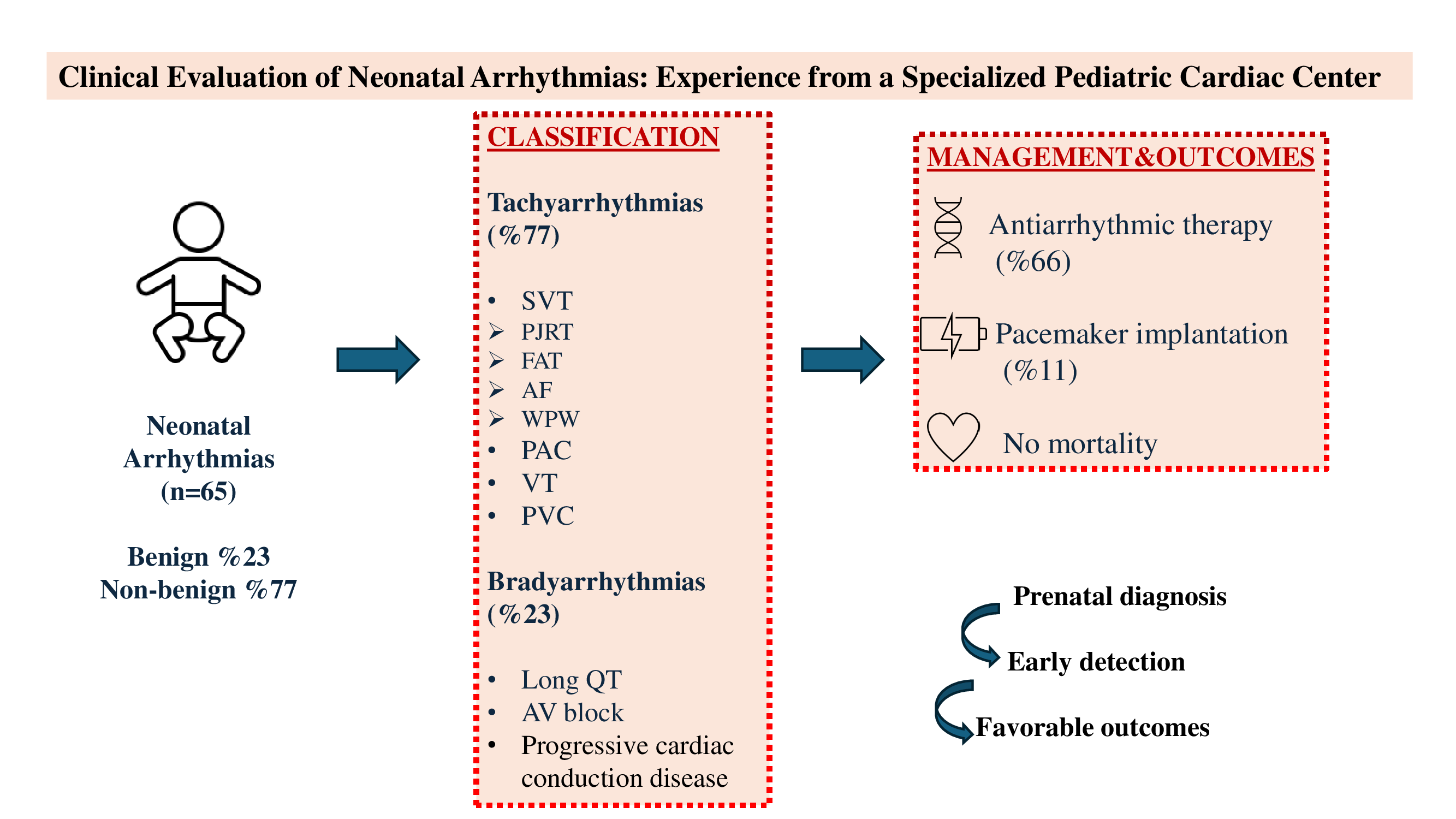

Of the total 65 patients included in the study, 37 (57%) were male and 28 (43%) were female. The mean weight of the patients was 3,2 kg (1–5,8). 6 (9,2%) patients were preterm. Non-benign arrhythmias were present in 50 (77%) patients, while benign arrhythmias were present in 15 (23%) patients. The characteristics of the benign and non-benign patient groups were compared (

Table 1).

In the univariate analysis, a statistically significant difference was found only in the cardiac disease variable (p = 0,01). Logistic regression analysis confirmed that the risk of developing benign arrhythmia in newborns with cardiac disease is significantly higher than that of non-benign arrhythmia. The presence of cardiac disease has been identified as an independent risk factor for benign arrhythmia.

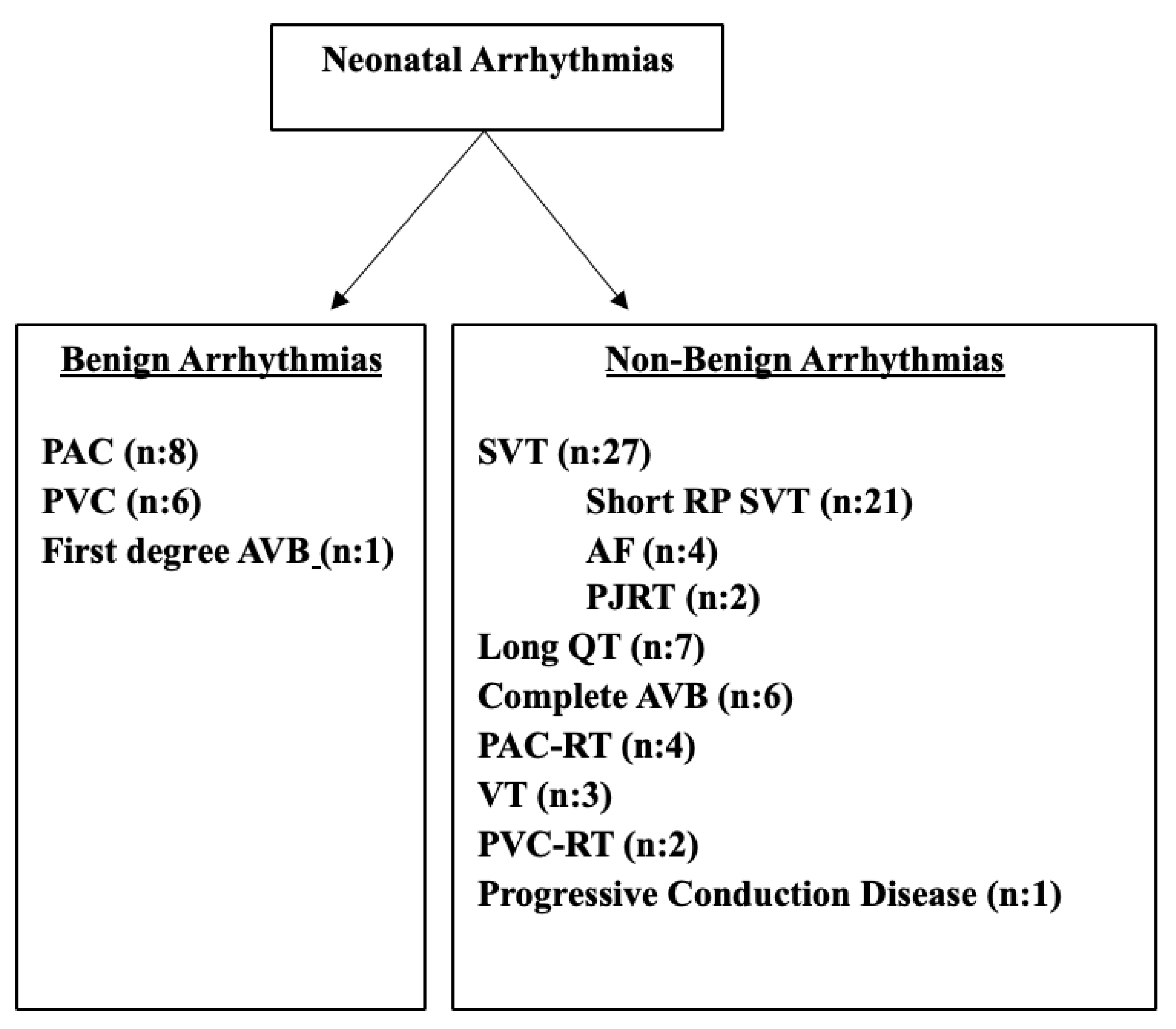

When examined in order of frequency, the most common benign arrhythmias were PAC (12,3%) and PVC (9,2%). First-degree AV block was observed in one patient (1,5%). Among non-benign arrhythmias, supraventricular tachycardia (35%) was the most common, followed by long QT syndrome (10.7%), complete atrioventricular block (9.2%), atrial flutter (6%), premature atrial contractions requiring treatment (6%), ventricular tachycardia (4.6%), ventricular extrasystoles requiring treatment (3%), and progressive cardiac conduction disease (1.5%) (

Figure 1).

3.1. Tachyarrhythmias

Tachyarrhythmia was detected in 50 of the total 65 patients (77%). Of the patients in the tachyarrhythmia group, 30 (60%) were male and 20 (40%) were female. Fifteen of these patients (30%) had a diagnosis of arrhythmia in the prenatal period.

Twenty-seven of the cases diagnosed with arrhythmia were supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). Within this group, permanent junctional reciprocal tachycardia (PJRT) was detected in 2 patients, focal atrial tachycardia and atrial flutter in 4 patients, and short RP SVT in 17 patients (3 of whom had Wolff-Parkinson-White [WPW] syndrome). In addition, four patients had frequent PAC with and/or without aberrant conduction requiring treatment, and eight patients had low-frequency benign PAC that did not require treatment.

PVC was present in 8 patients. In 2 of these, frequent PVC requiring treatment was identified, while in 6, benign PVC of low frequency that did not require treatment was detected. Additionally, ventricular tachycardia (VT) attacks were observed in three patients.

Twenty-five patients received single antiarrhythmic therapy (most commonly propranolol [n=15], followed by propafenone [n=7]). Ten patients received dual antiarrhythmic therapy (propranolol plus amiodarone in 8 patients, propranolol plus flecainide in 2 patients), while two patients received triple antiarrhythmic therapy (propranolol, amiodarone, and flecainide). Fourteen patients were followed without medication, 8 of whom had low-frequency PAC and 6 had low-frequency PVC.

During the follow-up period, recurrence occurred in 2 patients under treatment. In one patient with WPW syndrome, multiple SVT episodes were observed while on propranolol, leading to the addition of amiodarone. After four months without SVT episodes, the patient experienced a recurrence one month following the discontinuation of amiodarone, at which point therapy was switched to sotalol. In another patient with SVT, amiodarone was added due to an SVT attack despite propranolol treatment.

Cardioversion was performed in four patients diagnosed with atrial flutter (AF) on the first postnatal day.

The findings for patients with tachyarrhythmia are presented in

Table 2.

3.2. Bradyarrhythmias

Bradyarrhythmia was identified in 15 patients (23%) included in the study. Of this group, 8 (53%) were female and 7 (47%) were male. Seven patients (47%) were diagnosed prenatally. Subtype analysis revealed long QT syndrome in 7 patients, complete atrioventricular (AV) block in 6 patients, progressive cardiac conduction disease in 1 patient, and first-degree AV block in 1 patient.

A total of 7 patients (11%) underwent epicardial pacemaker implantation; 6 of these had congenital complete AV block and 1 had progressive cardiac conduction disease. In 2 patients with low birth weight, temporary epicardial pacing wires were placed prior to permanent pacemaker implantation.

Family history analysis revealed that the mother of a patient with complete AV block had Sjögren’s syndrome; the mother and grandmother of a patient with long QT syndrome were also diagnosed with long QT syndrome; and the sister of another patient with long QT syndrome was likewise affected.

Clinical and diagnostic features of the bradyarrhythmia group are summarized in

Table 3.

3.3. Clinical Presentation

When the diagnostic pathway was evaluated, 29 patients (44,6%) were diagnosed during routine examination due to the detection of arrhythmia or identification of ectopic beats/arrhythmias on ECG or echocardiography. Fourteen patients (21,5%) were diagnosed during NICU hospitalization due to tachycardia or bradycardia. Prenatal arrhythmia was detected in 22 patients (33,8%), of whom five were diagnosed with complete AV block, 2 with bradycardia, and 15 with tachycardia. The mean number of Holter examinations was 2,9 (1-30).

3.4. Presence of Congenital Heart Disease

A total of 9 patients (13,8%) had concomitant congenital heart disease. These included transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA, n:4), congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (C-TGA, n:2), total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage (TAPVD, n:2), and partial atrioventricular septal defect (pAVSD, n:1).

Among the patients with D-TGA, 1 had low-frequency PVC, 1 had frequent PVC, 1 had low-frequency PAC, and 1 had VT. Among the patients with C-TGA, 1 had first-degree AV block and 1 had complete AV block. SVT was observed in a patient with partial AVSD. Atrial flutter was detected in one of the TAPVD cases and SVT in the other.

3.5. Genetic Analysis

Genetic testing was performed in patients followed for long QT syndrome. As a result, a heterozygous SCN5A mutation was identified in one patient, and a heterozygous KCNH2 mutation was identified in another. In a patient with prenatal bradycardia who, during postnatal follow-up, exhibited bradycardia, long QT, first- and second-degree type 1 and type 2 AV block, as well as complete right bundle branch block (RBBB), a TRPM4 mutation was detected. This patient was diagnosed with progressive cardiac conduction disease, a condition reported as extremely rare in the literature.

3.6. Follow-Up

Among patients with tachyarrhythmias, 33 were followed without medication, while five received propranolol, one received sotalol, and one received flecainide. All patients who required pharmacological management were treated with single-agent antiarrhythmic therapy.

Recurrence was observed in 3% of all patients, both cases diagnosed with SVT. Eight patients received medical therapy for more than one year, including 7 with SVT (2 of whom had WPW syndrome) and 1 with VT. Patients with SVT were treated with propranolol, whereas the patient with VT received propranolol and flecainide. The mean follow-up duration was 12,8 months (1-40). No mortality was observed during the follow-up period.

4. Discussion

This single-center, retrospective study provides a comprehensive analysis of neonatal arrhythmias followed up at a tertiary cardiac center. In this single-center cohort, neonatal arrhythmias were classified as benign and non-benign, and their relationships with clinical and demographic variables were examined. In our study, non-benign arrhythmias were detected significantly more frequently than benign arrhythmias. Although studies in the literature have focused on non-benign arrhythmias [

4,

9], the study conducted by Ran et al. observed a higher frequency of benign arrhythmias [

10]. It may have been detected this way because they also included sinus arrhythmia as a benign arrhythmia. In the study conducted by Işık et al., the frequency of non-benign arrhythmia was found to be higher than that of benign arrhythmia, and there was no significant difference between them [

11]. The detection of non-benign arrhythmia in 77% of 65 patients in our study is consistent with the feature of our center being a tertiary cardiac center with a high number of patients referred.

The most noteworthy finding in our study was the higher rate of congenital cardiac disease in the benign arrhythmia group compared to the non-benign group (40,0% vs. 10,9%; p=0,04). This result seems paradoxical at first glance, given that structural heart disease is generally perceived as a risk factor for serious arrhythmias. However, due to the intensive monitoring and frequent electrocardiography/echocardiography checks of babies with structural anomalies, benign and usually self-limiting premature atrial or ventricular contractions are more easily recognized in these patients. In contrast, non-benign arrhythmias such as SVT, atrioventricular block, or long QT syndrome most often occur with an acute attack and may develop independently of structural heart disease. In addition, some congenital defects may manifest as either resolving or benign ectopia during the neonatal period. Conversely, diseases such as long QT syndrome, due to channelopathy, progress independently of structural heart disease and predominate in the non-benign arrhythmia group. This pattern has also been demonstrated in some neonatal intensive care unit series in the literature, and it has been reported that non-benign arrhythmias can be seen at a high rate in structurally normal hearts [

2,

4].

The fact that SVT was the most common arrhythmia type in the tachyarrhythmia group is consistent with the literature. Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is the most common type of non-benign arrhythmia in the neonatal period, and with early diagnosis and appropriate treatment, the prognosis is generally favorable [

12,

13]. Gillijiam et al. [

14] reported that 52% of patients remained recurrence-free during an average follow-up of one year without pharmacological therapy, which is in agreement with our findings. Ran et al. [

10] reported a 50% recurrence rate during the one-year follow-up of 40 patients with a diagnosis of SVT. In our study, recurrence was observed in only two patients, and when compared with the literature, the recurrence rate was found to be considerably lower.

According to Lupoglazoff and Denjoy, WPW syndrome is present in 70% of patients diagnosed with SVT under the age of three months [

15], while Gillijiam et al. reported a prevalence of 34% [

14], and Kundak et al. reported a prevalence of 27%. In our study, WPW was identified in 3 out of 29 patients with SVT, corresponding to a frequency of 10%.

Ventricular tachycardia is very rare in neonates and is usually associated with electrolyte disturbances, cardiomyopathy, or congenital heart disease [

16]. In our study, consistent with the literature, ventricular tachycardia (VT) was observed in 3 out of 50 patients diagnosed with tachycardia, corresponding to a rate of 6%. One of these patients had concomitant D-transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA).

In our study, no significant association was found between preterm birth, birth weight, sex, prenatal diagnosis, or family history and the type of arrhythmia. Although prenatal diagnosis was observed more frequently in the non-benign arrhythmia group (36,4% vs. 20%), the difference was not statistically significant. It has been reported that the diagnosis of prenatal arrhythmias by fetal echocardiography is being made with increasing frequency, facilitating the early detection and management of non-benign arrhythmias such as SVT or AV block in some series [

17,

18,

19]. Our findings may be attributable to the small sample size, and statistically significant results might be obtained with a larger cohort.

Family history plays a crucial role in inherited channelopathies, especially in cases of long QT syndrome. In our study, although family history appeared to be more frequent in the non-benign group compared with the benign group (14,5% vs. 10%), the difference was not statistically significant (p = 1,00). The limited statistical power due to the small sample size, along with the frequent occurrence of novel mutations, may explain why family history demonstrates limited predictive value in the neonatal period.

Complete atrioventricular (AV) block may be associated with congenital heart diseases, most commonly with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (C-TGA). In the presence of a structurally normal heart, maternal rheumatologic disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus or Sjögren’s syndrome increase the risk of developing atrioventricular block [

5,

20]. In our study, among six patients diagnosed with complete AV block, one had C-TGA, while another had a maternal history of Sjögren’s syndrome. The mortality associated with complete AV block has been reported to be as high as 20% [

21]. In our study, no cases of mortality were observed. We believe that the absence of mortality in patients with complete AV block in our study may be attributed to the fact that all cases were diagnosed prenatally in our center, closely monitored in collaboration with the perinatology clinic, and followed postnatally in our pediatric cardiology intensive care unit.

In neonates diagnosed with SVT, antiarrhythmic medical therapy is administered to reduce the frequency of attacks and to prevent the development of heart failure. The duration of therapy generally ranges from 6 to 12 months but may be individualized according to the clinical condition of the patient. It has been reported that discontinuing therapy in patients with pre-excitation increases the likelihood of recurrence by approximately 2.5 times [

22]. In our series, patients received medical therapy for a duration of 6 to 12 months. In addition, in patients with a history of SVT and a diagnosis of WPW syndrome, medical therapy was continued even in the absence of new SVT episodes.

In the literature, the reported mortality rate of neonatal arrhythmias ranges between 6% and 23,6%. In a review evaluating ten studies, 53 deaths were reported among a total of 547 patients with arrhythmias [

4,

11,

14,

16,

20,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. In our study, no mortality was detected. Similarly, in the study by Doi et al. [

9], no mortality was observed, which was attributed to the exclusion of patients with electrolyte disturbances and congenital heart disease from the study population. In our series, however, patients with unrepaired congenital heart disease were also included, and non-benign arrhythmias were observed to be more frequent in this group. While Doi et al. reported a prenatal diagnosis rate of 43.7% [

9], our study found rates of 30% in the tachyarrhythmia group and 47% in the bradyarrhythmia group.

The high rate of prenatal diagnosis may be a contributing factor to the low mortality rate.

Our study is a single-center, retrospective study, and the small sample size represents a limitation. Statistically more significant results may be obtained with a larger patient cohort.

5. Conclusion

Among neonatal arrhythmias, non-benign types are observed with a noteworthy frequency. Prenatal diagnosis facilitates the early detection of these arrhythmias during the neonatal period and, through timely and appropriate treatment, contributes to the prevention of potential heart failure and mortality. Although the prognosis is generally favorable in neonates receiving appropriate medical therapy, further large-scale studies are needed to determine the optimal duration of treatment. In conclusion, while our findings provide valuable insights into neonatal arrhythmias, further prospective studies with larger patient populations are warranted to more comprehensively evaluate risk factors and elucidate determinants contributing to increased mortality.

Author Contributions

H.Z.G., E.O, G.T.S. designed the study; H.Z.G, E.K, S.Y., D.Y.O., D.O. collected and analyzed data; H.Z.G., G.T.S. wrote the manuscript; G.T.S., E.O., M.C. gave technical support and conceptual advice. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Basaksehir Cam ve Sakura Ethics Committee on December 23, 2022, under the number 2022.12.413.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent forms were obtained from the parents of all patients included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- AM.; , D. Arrhythmias in the newborn. NeoReviews 2000, 1, e146–51. [CrossRef]

- Badrawi, N. Arrhythmia in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatr Cardiol 2009, 30(3), 325–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanel, RE, R.L., Fetal and neonatal arrhythmias. Clin Perinatol 2001, 28(1), 187–207. [CrossRef]

- Kundak, A.A. Non-benign neonatal arrhythmias observed in a tertiary neonatal intensive care unit. Indian J Pediatr 2013, 80(7), 555–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JE., B., Neonatal arrhythmias: diagnosis, treatment, and clinical outcome. Korean J Pediatr. 2017, 60(344).

- Killen, SAS; , F.F. Fetal and neonatal arrhythmias. NeoReviews 2008, 9, e242–52. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A; Flor-de-Lima, S.P.; Moura, F; Areias, C; Guimarães, JC; , H Neonatal arrhythmias—morbidity and mortality at discharge. J Pediatr Neonatal Individ Med 2016, p. e050212.

- Picchio FM, P.D., Bronzetti G et al., Follow-up of neonates with foetal and neonatal arrhythmias. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012, 25, 53.

- Doi, Y. Incidence of non-benign arrhythmia in neonatal intensive care unit: 18 years experience from a single center. J Arrhythm 2022, 38(3), 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, L. Association Between Neonatal Arrhythmia and Mortality and Recurrence: A Retrospective Study. Front Pediatr 2022, 10, 818164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, D.U. A case series of neonatal arrhythmias. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016, 29(8), 1344–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner CJ, W.C., The epidemiology of arrhythmia in infants: a population-based study. J Paediatr Child Health 2013, 49(4), 278–281. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugada J, B.N., Sarquella-Brugada G, et al., Pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapy for arrhythmias in the pediatric population: EHRA and AEPC-Arrhythmia Working Group joint consensus statement. Europace 2013, 15(9), 1337–1382. [CrossRef]

- Gilljam T, J.E., Gow RM., Neonatal supraventricular tachycardia: outcomes over 27 years at a single institution. Acta Paediatr. 2008, 97(8), 1035–1039. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupoglazoff JM, D.I., Attitude pratique devant un trouble du rythme chez le nourrisson [Practical attitude toward arrhythmia in the neonate and infant]. Arch Pediatr. 2004, 11(10), 1268–1273. [CrossRef]

- Davis AM, G.R., McCrindle BW, Hamilton RM. . Clinical spectrum, therapeutic management, and follow-up of ventricular tachycardia in infants and young children. Am Heart J. 1996, 131(1), 186–191. [CrossRef]

- Wacker-Gussmann, A; Cuneo, S.J.; Wakai, BF; , RT. The Treatment of Fetal Supraventricular Tachycardia: A Case Report and Literature Review. Int J Womens Health 2025, 17, 1945–1954. [CrossRef]

- Wacker-Gussmann, A; Cuneo, S.J.; Wakai, BF; , RT. Fetal arrhythmia diagnosis and pharmacologic management. J Clin Pharmacol. 2022, 62 Suppl 1, S53–S66.

- Wacker-Gussmann, A; Cuneo, S.J.; Wakai, BF; , RT. Diagnosis and treatment of fetal arrhythmia. Am J Perinatol. 2014, 31(7), 617–628. [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, H; Sharland, S.S.; , G. Isolated atrioventricular block in the fetus: a retrospective, multinational, multicenter study of 175 patients. Circulation 2011, 124(18), 1919–1926. [CrossRef]

- Chandler, SF; Mah, F.-T.F.; , DY Role of cardiac pacing in congenital complete heart block. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2017, 15(11), 853–861. [CrossRef]

- Mecklin, M; Hiippala, L.A.; , A. Multicenter cohort study on duration of antiarrhythmic medication for supraventricular tachycardia in infants. Eur J Pediatr. 2023, 182(3), 1089–1097.

- Binnetoglu, F.K. Diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of neonatal arrhythmias. Cardiovasc J Afr 2014, 25(2), 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, JF; Chen, P.X.; Pan, BL; , XN. Comparison of clinical characteristics of benign versus non-benign neonatal arrhythmia. Guangxi Med J. 2020, 9, 1072–5.

- Moura, C; Guimarães, V.A.; Areias, H; , JC.. Perinatal arrhythmias -- diagnosis and treatment. Rev Port Cardiol. 2002, 21(1), 45–55.

- Casey, FA; Hamilton, M.B.; Gow, RM; , RM. Neonatal atrial flutter: significant early morbidity and excellent long-term prognosis. Am Heart J. 1997, 133, 302–6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, YY; Zhang, K.W.; Liu, YD; Fang, DT; , PP. Clinical analysis of neonatal arrhythmia in 89 cases. J Chin Pract Diagn Ther. 2018, 9, 896–8.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).