Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

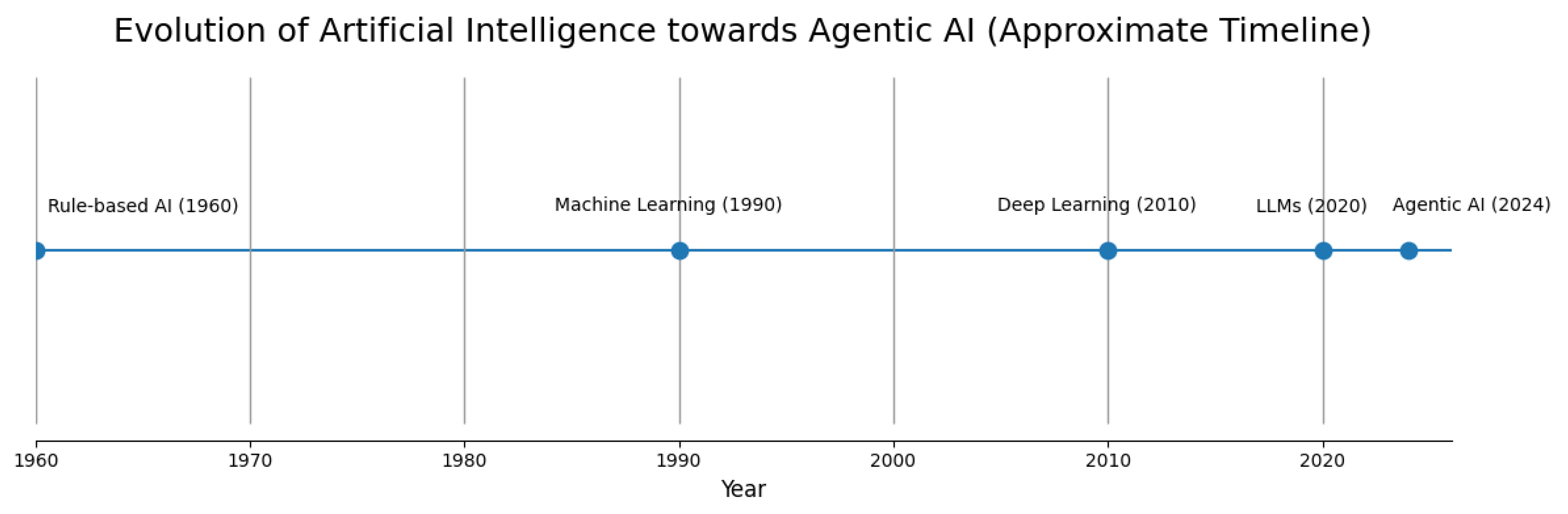

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Initial Search: Approximately 97 papers were identified through database searches and citation chaining.

- Screening by Title and Abstract: Papers unrelated to agentic AI, general machine learning, or purely theoretical models were removed.

- Full-Text Review: Papers that discussed autonomous agent behavior, multi-agent coordination, or AI-driven decision workflows were retained.

- Final Inclusion: 51 papers were included for full analysis and synthesis.

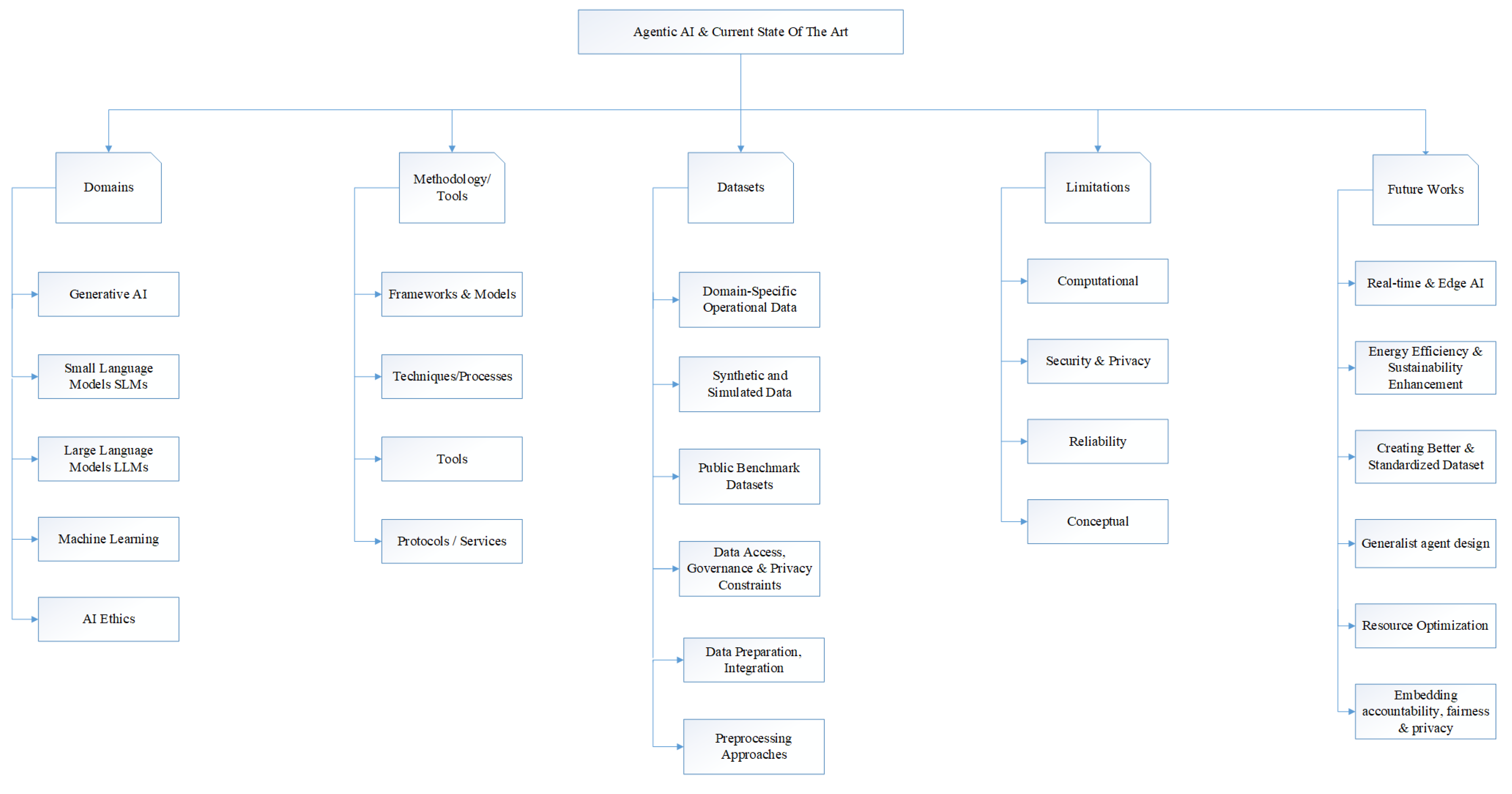

3. Taxonomy of Agentic AI and Its Current State of the Art

4. Application Domains

4.1. Healthcare (diagnostics, monitoring, clinical workflows)

4.2. Networking, Telecom and 6G (intent-driven orchestration and adaptive networks)

4.3. Cybersecurity and Network Monitoring

4.4. DevOps, Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC), and IT Operations (AIOps)

4.5. E-commerce, Supply Chains and Business Process Automation

4.6. Digital Twins, Scientific Infrastructure and Industrial Control

4.7. Education and Human-AI Collaborative Learning

4.8. Perception, Robotics and Multimodal Interaction

4.9. Cross-cutting / Governance and Socio-technical Applications

5. Methods and Techniques

5.1. Orchestration Patterns

5.2. Multi-Agent Coordination and Protocols

5.3. Planning, Reasoning and Long-Horizon Control

5.4. Model Stack: LLMs, SLMs, and Hybrid Deployments

5.5. Tooling and External Integrations (APIs, IaC, Edge Components)

5.6. Formal Methods and Verifiability

5.7. Observability, AgentOps and Runtime Governance

5.8. Security, Identity and Trust Mechanisms

5.9. Evaluation Metrics and Benchmarks

6. Data Sources / Datasets / Evaluation Practice

6.1. Domain-Specific Operational Data

6.2. Synthetic and Simulated Data

6.3. Public Benchmark Datasets

6.4. Data Access, Governance and Privacy Constraints

6.5. Data Preparation, Integration and Preprocessing Approaches

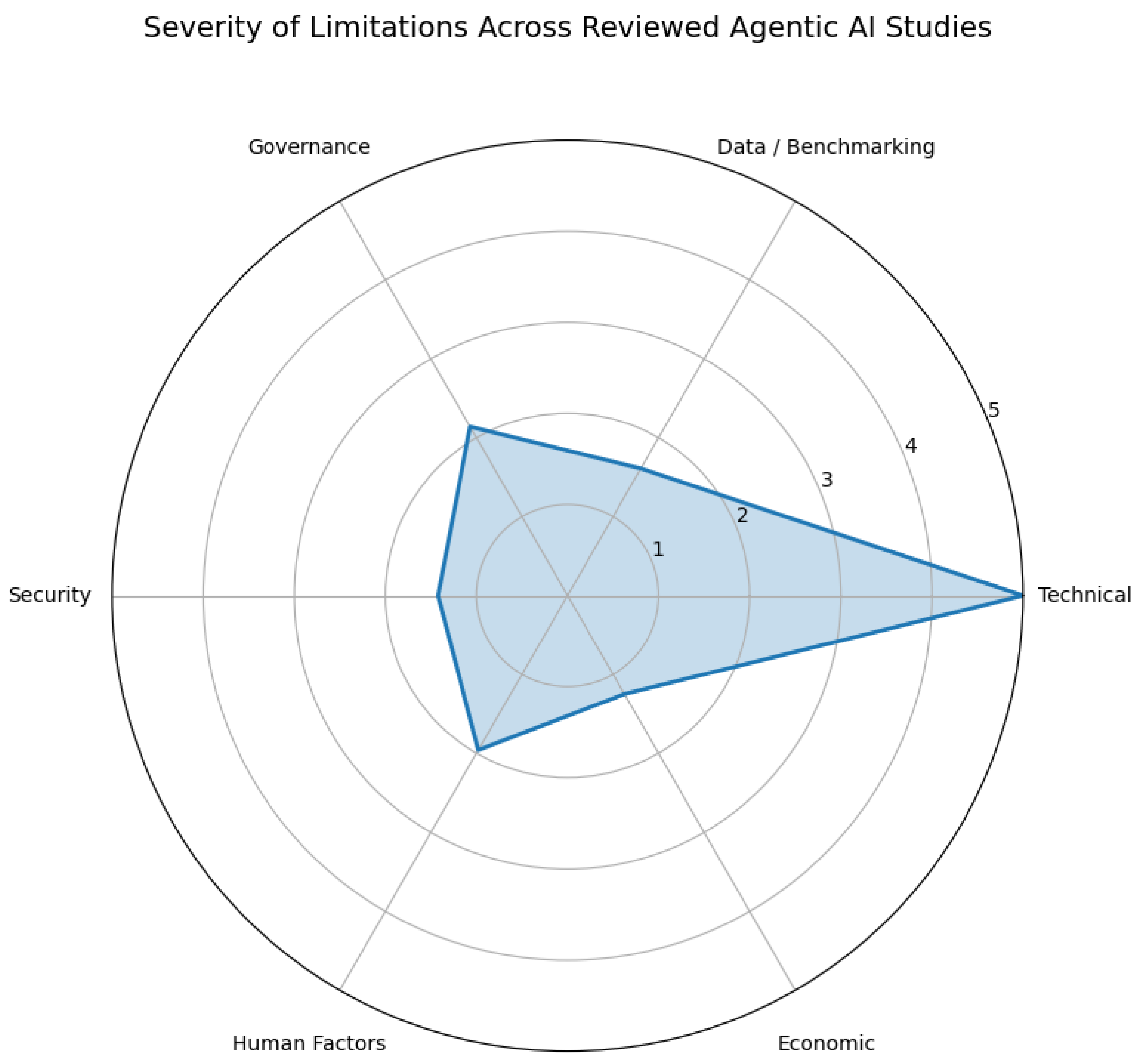

7. Limitations

7.1. Technical Limitations

7.2. Data, Benchmarking and Evaluation

7.3. Governance, Explainability and Ethics

7.4. Security and Adversarial Risks

7.5. Human Factors and Usability

7.6. Operational and Economic Constraints

7.7. Summary of Limitations

8. Future Work and Research Directions

8.1. Scalable, Efficient Agentic Architectures

8.2. Standardized Benchmarks and Evaluation Frameworks

8.3. Runtime Governance, Traceability and Oversight

8.4. Security, Trust, and Multi-Agent Credential Infrastructure

8.5. Human-Centered Interaction and Collaboration

8.6. Cross-Domain Generalization and Transfer

9. Conclusion

References

- Miehling, E.; Ramamurthy, K.N.; Varshney, K.R.; Riemer, M.; Bouneffouf, D.; Richards, J.T.; Dhurandhar, A.; Daly, E.M.; Hind, M.; Sattigeri, P.; et al. Agentic AI Needs a Systems Theory. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.00237. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J. Building Living Software Systems with Generative & Agentic AI. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.01768. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, V. Designing the Mind: How Agentic Frameworks Are Shaping the Future of AI Behavior. Journal of Computer Science and Technology Studies 2025, 7, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Chang, H.H. Agentic AI: Autonomy, Accountability, and the Algorithmic Society. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.00289. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissuchek, C.; Zschech, P. Exploring Agentic Artificial Intelligence Systems: Towards a Typological Framework. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Z.; Calinescu, R.; Lim, E.; Hodge, V.; Ryan, P.; Burton, S.; Habli, I.; Lawton, T.; McDermid, J.; Molloy, J.; et al. INSYTE: A Classification Framework for Traditional to Agentic AI Systems. ACM Trans. Auton. Adapt. Syst. 2025, 20, 15:1–15:39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Curtò, J.; de Zarzà, I. LLM-Driven Social Influence for Cooperative Behavior in Multi-Agent Systems. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 44330–44342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derouiche, H.; Brahmi, Z.; Mazeni, H. Agentic AI Frameworks: Architectures, Protocols, and Design Challenges. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.10146. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gong, J.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, Z. AI Agentic Programming: A Survey of Techniques, Challenges, and Opportunities, 2025. arXiv arXiv:2508.11126. [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Shimgekar, S.R.; Vassef, S.; Goyal, A.; Kumar, N.; Saha, K. Agentic AI framework for End-to-End Medical Data Inference. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.18115. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamisetty, A.; Farms, M. Application of agentic artificial intelligence in autonomous decision making across food supply chains 2024. 1.

- Zambare, P.; Thanikella, V.N.; Kottur, N.P.; Akula, S.A.; Liu, Y. NetMoniAI: An Agentic AI Framework for Network Security & Monitoring. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.10052. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Peng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tang, W.T.; Kobayashi, H.H.; Zhang, W. EnvX: Agentize Everything with Agentic AI. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.08088. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, H.; Dempere, J. Agentic AI for IT and Beyond: A Qualitative Analysis of Capabilities, Challenges, and Governance. The Artificial Intelligence Business Review 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, L.; Keeling, G.; McCroskery, A. Should agentic conversational AI change how we think about ethics? Characterising an interactional ethics centred on respect. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.09082. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedar, I.; Desroches, C. Agentic AI: Designing for Autonomy Without Losing Control.

- Wang, C.L.; Singhal, T.; Kelkar, A.; Tuo, J. MI9 – Agent Intelligence Protocol: Runtime Governance for Agentic AI Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.03858. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodimas, D.; Birbas, A.; Kapolos, D.; Denazis, S. Intent-Based Infrastructure and Service Orchestration Using Agentic-AI. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society 2025, 6, 7150–7168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghoff, U.M.; Bottoni, P.; Pareschi, R. Beyond Prompt Chaining: The TB-CSPN Architecture for Agentic AI. In Future Internet; Publisher; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 2025; Volume 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, A.; Albaseer, A.; Qadir, J.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Abdallah, M. LLM-Driven Multi-Agent Architectures for Intelligent Self-Organizing Networks. IEEE Network 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcak, P.; Heinrich, G.; Diao, S.; Fu, Y.; Dong, X.; Muralidharan, S.; Lin, Y.C.; Molchanov, P. Small Language Models are the Future of Agentic AI. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.02153. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprani, D.; Madisetti, V.K. LLM Agentic Workflow for Automated Vulnerability Detection and Remediation in Infrastructure-as-Code. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 69175–69181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshkovich, D.; Zeltyn, S. Taming Uncertainty via Automation: Observing, Analyzing, and Optimizing Agentic AI Systems, 2025. arXiv arXiv:2507.11277. [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Timms, A.; Langbridge, A.; Antonopoulos, A.; Mygiakis, A.; Voulgari, E.; O’Donncha, F. Agentic AI for Digital Twin. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 39, 29703–29705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzistefanidis, I.; Leone, A.; Nikaein, N. Maestro: LLM-Driven Collaborative Automation of Intent-Based 6G Networks. IEEE Networking Letters 2024, 6, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunanayake, N. Next-generation agentic AI for transforming healthcare. Informatics and Health 2025, 2, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suura, S.R. Agentic AI Systems in Organ Health Management: Early Detection of Rejection in Transplant Patients. Journal of Neonatal Surgery 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Wang, L.; Fard, P.; Junior, V.M.; Blacker, D.; Haas, J.S.; Patel, C.; Murphy, S.N.; Moura, L.M.V.R.; Estiri, H. An Agentic AI Workflow for Detecting Cognitive Concerns in Real-world Data. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.01789. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.; Nezami, Z.; Qazzaz, M.M.H.; Hafeez, M.; Zaidi, S.A.R. Edge Agentic AI Framework for Autonomous Network Optimisation in O-RAN. arXiv [eess]. 2025, arXiv:2507.21696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botti, V. Agentic AI and Multiagentic: Are We Reinventing the Wheel? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.01463. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brohi, S.; Mastoi, Q.u.a.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Pillai, T.R. A Research Landscape of Agentic AI and Large Language Models: Applications, Challenges and Future Directions. In Algorithms; Publisher; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 2025; Volume 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Yu, C.L.; Susanto, E.A.; Lau, N.W.L.; Meadows, G.I. AgentPeerTalk: Empowering Students through Agentic-AI-Driven Discernment of Bullying and Joking in Peer Interactions in Schools. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.01459. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L. From Passive Tool to Socio-cognitive Teammate: A Conceptual Framework for Agentic AI in Human-AI Collaborative Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.14825. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghoff, U.M.; Bottoni, P.; Pareschi, R. Human-artificial interaction in the age of agentic AI: a system-theoretical approach. In Frontiers in Human Dynamics; Frontiers, 2025; Volume 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, R.; Roumeliotis, K.I.; Karkee, M. AI Agents vs. Agentic AI: A Conceptual Taxonomy, Applications and Challenges. Information Fusion 2025, arXiv:2505.10468[cs]. 126, 103599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olujimi, P.A.; Owolawi, P.A.; Mogase, R.C.; Wyk, E.V. Agentic AI Frameworks in SMMEs: A Systematic Literature Review of Ecosystemic Interconnected Agents. In AI; Publisher; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 2025; Volume 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, D.B.; Kuppan, K.; Divya, B. Agentic AI: Autonomous Intelligence for Complex Goals—A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 18912–18936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, N. Agentic AI in radiology: emerging potential and unresolved challenges. British Journal of Radiology 2025, 98, 1582–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Niyato, D.; Kang, J.; Li, Y.; Mao, S.; et al. Toward Edge General Intelligence with Agentic AI and Agentification: Concepts, Technologies, and Future Directions. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.18725. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbu, D. Agentic AI in Computer Vision Domain -Recent Advances and Prospects. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews 2023, Vol 4, 5102–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, G.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Kang, J.; Niyato, D.; Li, Z.; Xuemin; Shen; et al. Edge General Intelligence Through World Models and Agentic AI: Fundamentals, Solutions, and Challenges. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.09561. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R.A.; Ahmad, K.; Ali, H. Redefining Elderly Care with Agentic AI: Challenges and Opportunities. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.14912. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tang, S.; Liu, Y.; Niyato, D.; Xiong, Z.; Sun, S.; Mao, S.; Han, Z. Toward Agentic AI: Generative Information Retrieval Inspired Intelligent Communications and Networking. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.16866. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridach, M.; Nanavati, J.; Abidine, K.Z.E.; Mendes, L.; Mack, C. Agentic AI for Scientific Discovery: A Survey of Progress, Challenges, and Future Directions. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.08979. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, R.; Roumeliotis, K.I.; Karkee, M. Vibe Coding vs. Agentic Coding: Fundamentals and Practical Implications of Agentic AI, 2025. arXiv arXiv:2505.19443. [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Bandi, A.; Kongari, B.; Naguru, R.; Pasnoor, S.; Vilipala, S.V. The Rise of Agentic AI: A Review of Definitions, Frameworks, Architectures, Applications, Evaluation Metrics, and Challenges. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, S.; Seilani, H. The role of agentic AI in shaping a smart future: A systematic review. Array 2025, 26, 100399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Pan, C.; Dong, L.; Wang, K.; Dobre, O.A.; Debbah, M. From Large AI Models to Agentic AI: A Tutorial on Future Intelligent Communications. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.22311. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ji, T.; Xu, X. AI Agents and Agentic AI-Navigating a Plethora of Concepts for Future Manufacturing, 2025. arXiv arXiv:2507.01376. [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. In BMJ; British Medical Journal Publishing Group Section: Research Methods & Reporting, 2021; Volume 372, p. n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, K.; Khowaja, S.A.; Singh, K.; Zeydan, E.; Debbah, M. Advanced Architectures Integrated with Agentic AI for Next-Generation Wireless Networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.01089. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Shi, G.; Zhang, P. Towards Agentic AI Networking in 6G: A Generative Foundation Model-as-Agent Approach. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.15764. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheelam, G.K.; Komaragiri, V.B. Self-Adaptive Wireless Communication: Leveraging ML And Agentic AI In Smart Telecommunication Networks. Metallurgical and Materials Engineering 2025, 1381–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosmar, D.; Dahl, D.A. Hallucination Mitigation using Agentic AI Natural Language-Based Frameworks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.13946. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habler, I.; Huang, K.; Narajala, V.S.; Kulkarni, P. Building A Secure Agentic AI Application Leveraging A2A Protocol. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.16902. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, S. Agentic AI in Predictive AIOps: Enhancing IT Autonomy and Performance. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM) 2024, 12, 1631–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alecsoiu, O.R.; Faruqui, N.; Panagoret, A.A.; Ionuţ, C.A.; Panagoret, D.M.; Nitu, R.V.; Mutu, M.A. EcoptiAI: E-Commerce Process Optimization and Operational Cost Minimization Through Task Automation Using Agentic AI. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 70254–70268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulc, A.; Hellert, T.; Kammering, R.; Hoschouer, H.; John, J.S. Towards Agentic AI on Particle Accelerators. arXiv [physics]. 2025, arXiv:2409.06336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, L.H.; Wang, L.; Lei, D. Conversational, agentic AI-enhanced architectural design process: three approaches to multimodal AI-enhanced early-stage performative design exploration. Architectural Intelligence 2025, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Ren, H.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Xu, D.; Fan, Z.; You, S.; Wang, Z.; Guibas, L.; et al. Feature4X: Bridging Any Monocular Video to 4D Agentic AI with Versatile Gaussian Feature Fields. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.20776. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, L. Perceptions of Agentic AI in Organizations: Implications for Responsible AI and ROI, 2025. arXiv arXiv:2504.11564. [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Brachman, M.; Kunde, S.; Miller, S.; Fucs, A.; Dempsey, S.; Jabbour, J.; Geyer, W. Building Appropriate Mental Models: What Users Know and Want to Know about an Agentic AI Chatbot. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, New York, NY, USA, 2025; IUI ’25, pp. 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, H.; Baig, M.Z.; Mehmood, Y.; Shahzad, N.; Huang, K.; Haq, M.A.U.; Awais, M.; Ahmed, K. QSAF: A Novel Mitigation Framework for Cognitive Degradation in Agentic AI. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.15330. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, L.N.; Senapati, B. Retail Resilience Engine: An Agentic AI Framework for Building Reliable Retail Systems With Test-Driven Development Approach. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 50226–50243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Narajala, V.S.; Yeoh, J.; Ross, J.; Raskar, R.; Harkati, Y.; Huang, J.; Habler, I.; Hughes, C. A Novel Zero-Trust Identity Framework for Agentic AI: Decentralized Authentication and Fine-Grained Access Control. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.19301. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, N.V.D.S.S.V.P.; Faruqui, N.; Patel, N.; Alecsoiu, O.R.; Thatoi, P.; Alyami, S.A.; Azad, A. LegalMind: Agentic AI-Driven Process Optimization and Cost Reduction in Legal Services Using DeepSeek. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 126981–126999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L.; Buttaboni, C.; Hine, E.; Morley, J.; Novelli, C.; Schroder, T. Agentic AI Optimisation (AAIO): what it is, how it works, why it matters, and how to deal with it. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.12482. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, A. Agentic AI Systems: Architecture and Evaluation Using a Frictionless Parking Scenario. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 126052–126069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C. Toward Data Systems That Are Business Semantic Centric and AI Agents Assisted. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 113752–113762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, N.T.; Sharma, A.; Xiao, J.; Siong Chin, C.; Jun Xing, C.; Lok Woo, W. Optimized Sequential Agentic AI-Guided Trainable Hybrid Activation Functions for Solar Irradiance Forecasting. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 149976–149990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, P.J.; Lim, S.L.; Ishikawa, F. Situating AI Agents in their World: Aspective Agentic AI for Dynamic Partially Observable Information Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.03380. [cs]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).