Introduction

In a computer science curriculum, The Theory of Computation (ToC) may be regarded as the intellectual backbone as it poses and addresses some of the most fundamental questions such as: What is computation? What can be computed? How can it be computed? And what simply cannot be computed? These questions are not only concerned with academic reasoning; they have a direct impact on software engineering, AI, cryptography, and algorithmic problem solving. ToC provides a structured approach through which these problems are scrutinized in terms of their feasibility, efficacy, and intricacy. It encompasses language classification and also pertains to limits of machines alongside algorithmic logic.

Within the cryptic challenges arising from ToC, The Halting Problem appears to be one of its most intriguing puzzles. Formulated by Alan Turing in 1936, the issue asks if there could be some universal approach that takes any program with any input and always tells whether the program would stop or run in infinite loops. As powerful as it is profound, Turing’s answer was equally unexpected: no form exists to solve this problem algorithmically. His richly persuasive proof not only supported modern computability theory but also redefined philosophical and practical frontiers in computer science. The Halting Problem is more than just a theoretical construct, as it introduces the idea of undecidability, which uncovers the fact that even in our current age with highly advanced machines, there exist problems that will always be beyond algorithmic resolution(GeeksforGeeks, 2018). The image below captures some of the real-world consequences spawned by Alan Turing’s 1936 proposal of the Turing Machine which served as an early blueprint for modern computers and the theory of undecidability.

Figure 1.

Early engineers working on one of the first computers inspired by Turing’s theoretical model (History and heritage - Department of Computer Science).

Figure 1.

Early engineers working on one of the first computers inspired by Turing’s theoretical model (History and heritage - Department of Computer Science).

To grasp fully the Halting Problem, one has to navigate through a landscape framed around making decisions regarding computations. In this landscape, the focus point is centered around a key pillar called computability—researching whether or not given challenges can be solved using an algorithmic step-by-step approach. Decidability concerns itself with whether a problem exists for an algorithm capable of answering in yes or no decisively stopping after a determined finite time interval (Tutorialspoint.com, 2025).Conversely, undecidable are problems that lack any form of algorithmic solution; The Halting Problem stands as one of the earliest and foremost examples proving this unsettling fact: Not every query a computer poses can actually be resolved by another computer.

To formalize these ideas, Turing introduced the Turing Machine, an abstract form of computation that captures the essence of any algorithm. A Turing Machine is composed of an infinite tape, a read/write head, and a finite set of states and instructions. Despite its simplicity, it is as powerful as any modern programming language in terms of what it can compute. If a problem is solvable by a Turing Machine that always halts with a decision, it is called decidable. If it can be recognized, meaning that the machine halts and accepts valid inputs, but may run forever on invalid ones, it is called recognizable or recursively enumerable. If neither is possible, the problem is undecidable and unrecognizable.

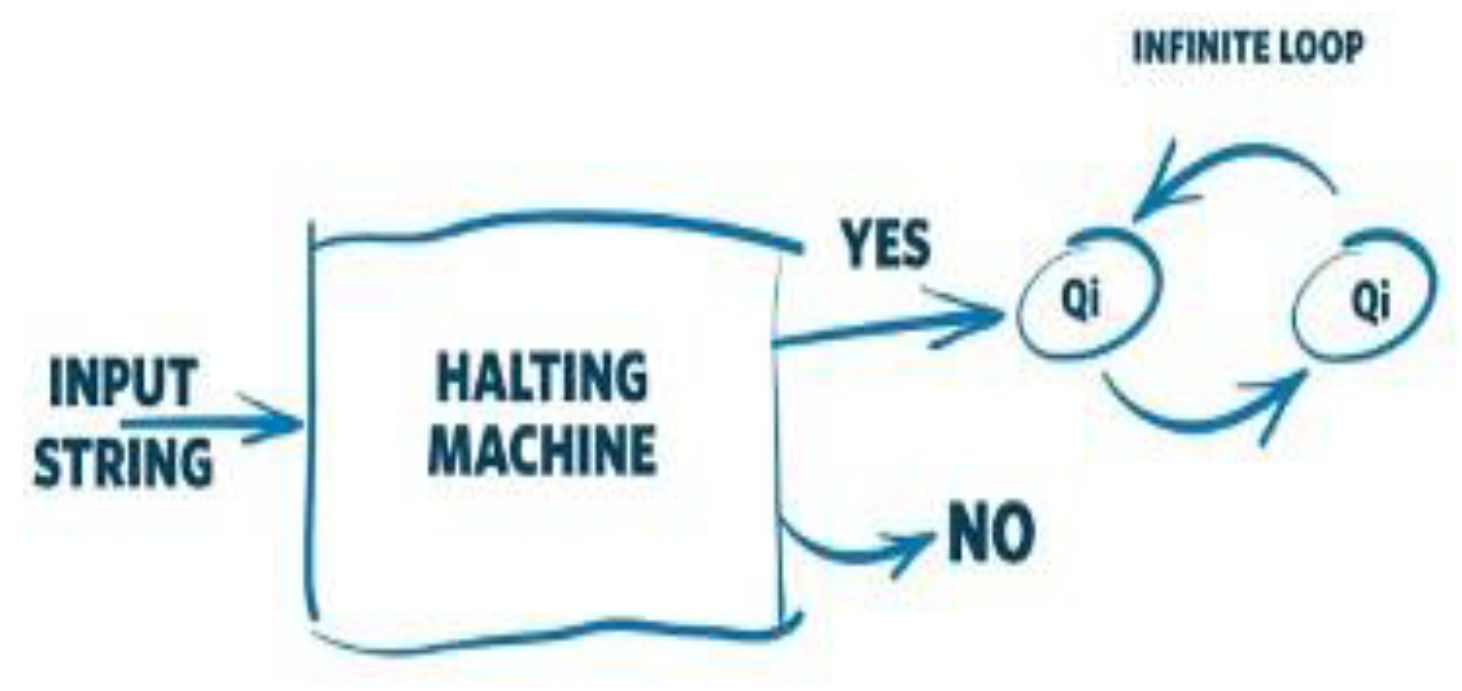

The Halting Problem lies at the intersection of these definitions. It is recognizable but undecidable a Turing Machine can identify and accept halting programs when they do halt, but cannot detect when they won’t. This paradox underpins a vast family of other undecidable problems and has direct implications in software verification, security analysis, AI systems, and automated reasoning (Gautam, 2024). The problem is not merely of theoretical interest; it exposes the limits of what software can predict or guarantee, even in critical systems.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of the Halting Machine (Morgan, 2017).

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of the Halting Machine (Morgan, 2017).

The goal of this essay is to conduct an in-depth exploration of the Halting Problem, tracing its origins, analyzing its formal proof, and illustrating its relevance in modern computational theory. By engaging deeply with this topic, the essay demonstrates an ongoing commitment to self-inquiry, an appreciation for the boundaries of logic and automation, and a nuanced understanding of why the Halting Problem continues to be one of the most intellectually compelling questions in computer science.

Foundations of Computability

Computability and Turning Machine

Computability theory is the foundational branch of theoretical computer science studying the boundaries of algorithmic problem-solving. Its essence lies in the essential questions as: What kinds of problems can be solved using a computational procedure? and What lies beyond the reach of even the most powerful machines? In order to examine the solvability of a problem within an algorithm, researchers present problems as decision problems which usually take the form of a formal language. A problem is considered computable (or decidable) when there is a well-defined algorithm to solve it, that is, a finite algorithm that could generate the correct yes/no answer to any given input in a finite number of steps (Sanders, 2022). This classification is important in two ways: first, it aids in software development by identifying solvable problems and secondly it is a precaution against unsolvable problems such as the halting problem.

In order to formalize the concept of computability, Alan Turing in 1936 proposed an abstract model of computation called the Turing Machine. Despite its simplicity, it can simulate the action of any modern digital computer and remains the gold standard to define algorithmic processes (Triantafyllou, 2024).

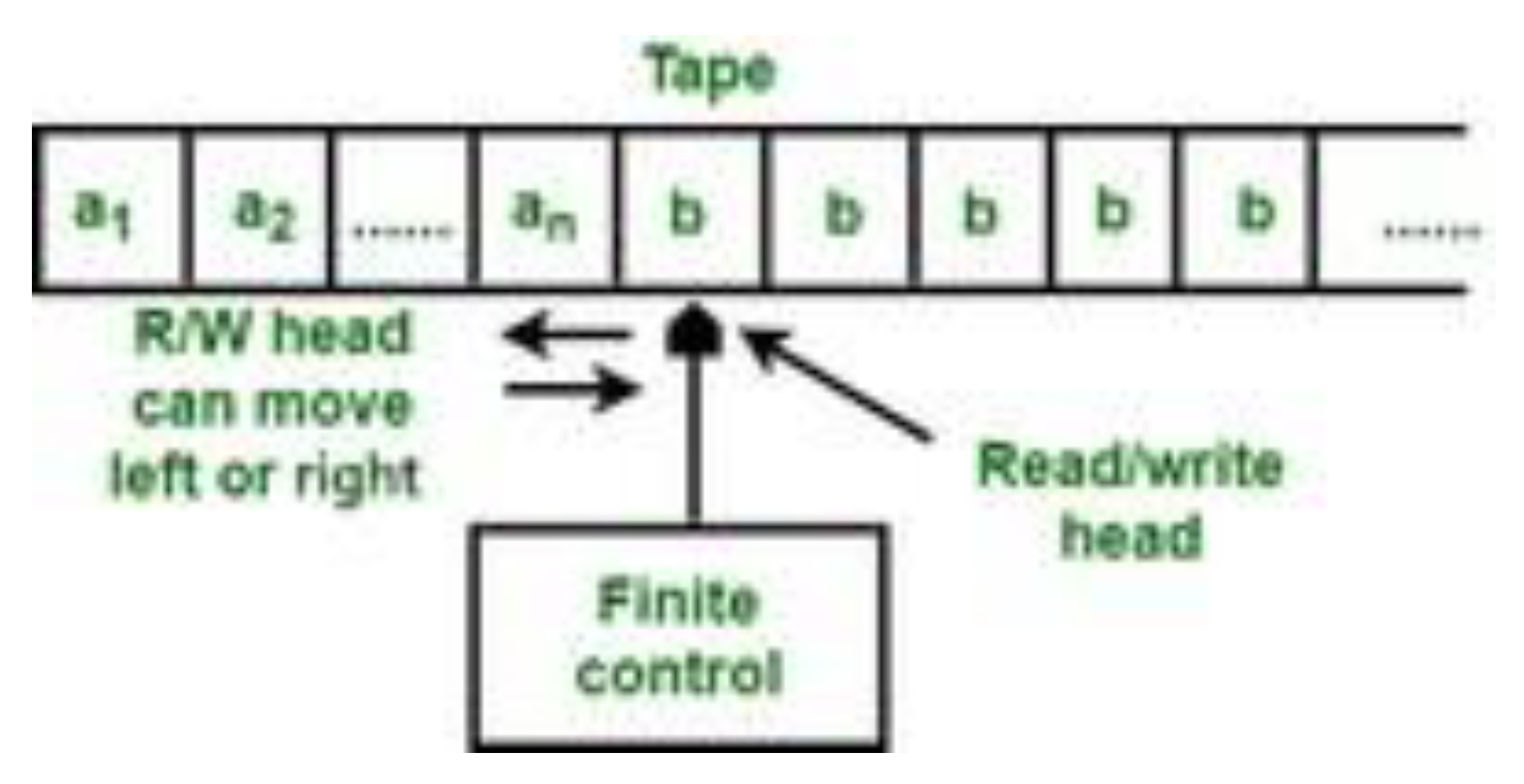

The components of the Turning Machine are: (GeeksforGeeks, 2016)

Infinite tape: acting as an input and memory, divided into discrete cells capable of storing a symbol of an alphabet previously defined.

Read/write head: capable of reading the current cell, writing a new symbol, and moving left or right along the tape.

Finite set of internal states: consisting of a start state and one or more are halting (accept or reject) states.

A transition function that defines how the machine will act according to the current state and the symbol positioning under the tape head. It governs which symbol to write, the direction of head and what state to move to.

Figure 3.

Conceptual Model of a Turing Machine (GeeksforGeeks, 2016). The machine comprises an infinite tape, a read/write head and a finite control unit. It reads and writes symbols following a set of predetermined rules and travels on the tape according to the transition rule.

Figure 3.

Conceptual Model of a Turing Machine (GeeksforGeeks, 2016). The machine comprises an infinite tape, a read/write head and a finite control unit. It reads and writes symbols following a set of predetermined rules and travels on the tape according to the transition rule.

The machine initially is in its start state and the input on the tape is processed by the transition rules, and it keeps running till it reaches halting state (stops). A problem is called decidable when there is a Turing Machine that halts with an affirmative yes/no outcome to every input, at some point of the computation. In the case of the machine stopping only on inputs that are valid but might go on infinitely on invalid inputs, the problem is recognizable (also known as recursively enumerable). Not only does the Turing Machine give a formal mechanism of defining computation, it also enables language and problems classification into decidable, recognizable, and undecidable. This theoretical framework is essential in obtaining a conceptualization of the boundaries of computation and informs the design of reliable and efficient algorithms in practice(Wong, 2023).

This fundamental knowledge of computability, which is based on the model of a Turing Machine, sets the stage to discuss the way problems can be classified according to whether or not they are solvable; leading to the discussion of decidable and recognizable languages in the following section.

Decidability, Recognizability, and the Limits of Computation

The distinction of computational problems into decidable and recognizable, based on the model of the Turing Machine, is a significant factor in establishing the extent of what is and is not computable. These categories are central to computability theory, offering a systematic way to assess whether a problem is algorithmically solvable and to what extent.

A language (or decision problem) can be said to be decidable when there exists a Turing Machine that always halts with a definitive yes or no answer for every input. In this case, the problem is here fully solvable in finite time as the algorithm (represented by the Turing Machine) is guaranteed to actually terminate. Examples of that: to see whether a number is even, whether a string is a part of a regular language, or whether parentheses in an expression are balanced. These are the problems to which terminating algorithms exist, and it appears frequently in practical computer software including compilers, input validators and program checkers (Tourlakis, 2022).

However, a language is recognizable (also known as recursively enumerable) whenever there is a Turing Machine that accepts every string in the language by halting in an accept state, but may run indefinitely for inputs not in the language. In practical terms, this means the machine can confirm a “yes” answer but might never return a “no” answer, it simply runs forever (Strnad,1970).

Recognizable problems are important in diverse fields of computer science, specifically in automated proof-finding, bug detection, and software verification where it is of use to partially confirm correctness, even though full verification cannot be addressed.

It is important to understand that every recognizable language is decidable, but the reverse is not true. This asymmetry leads directly to the concept of undecidability problems for which no such algorithm exists yet that can produce a correct decision for all inputs. Among the most well known is the Halting Problem, which inquiries on whether a Turing Machine will halt under a given input. In 1936, Alan Turing proved that this problem is undecidable: no universal algorithm can determine the halting behaviour for every possible machine-input pair.

In order to demonstrate the undecidability of such problems, computer scientists use a powerful method known as diagonalization. Diagonalization was originally introduced by Georg Cantor to show the uncountability of real numbers; it was later modified by Turning to prove the limits of computation. The essence of diagonalization is to assume that all possible algorithms (Turing Machines) can be listed and then construct a new problem or machine that contradicts the properties of each one in the list (Fried and Jarden, 2023). The technique can demonstrate an incomplete listing and thus, no general algorithm exists, by demonstrating that this constructed machine is not identical to any of the listed ones at least at one input.

This method is not only dignified but highly revealing. It shows that there are more problems than there are algorithms, while some of these problems are so complex or paradoxical that they cannot be resolved by any computational process, no matter how advanced. Diagonalization, as applied to the Halting Problem, shows that there is a paradoxical consequence that occurs when we assume the existence of a machine that makes the halting decision universally, which then proves that such machines cannot exist.

Theoretical constructs such as decidability, recognizability and diagonalization all bound the scope of the algorithmic logic and inform the real life design of computing systems. They assist in the identification of the tasks that can be safely automated and the areas where human oversight or approximation should take place. With the development of modern computation, the impact of these insights has never been surpassed with concepts given to developers, theorists and engineers to navigate the power and limitations of the machines they build.

The Halting Problem

As outlined above, the Halting Problem constitutes one of the most significant discoveries in theoretical computer science that was presented by Alan Turing in his remarkable 1936 paper titled: On Computable Numbers, with application to the Entscheidungsproblem.

The Halting Problem deals with one of the fundamental questions which is “When there is a description of a computer program and an input, is it possible to discover whether the program halts (terminates) after some time or runs forever?”. By the appearance of this question, the implications for what computers can and cannot do algorithmically were profound. It is the center of computability theory, a part of the Theory of Computation inquiry into the boundaries of mechanical computation. The Halting Problem is undecidable; a general existing algorithm that solves the halting problem on all programs and all input does not exist (GeeksforGeeks, 2018). The issue arises frequently in the study of computability as it illustrates that there are functions that can be defined mathematically but cannot be computed.

In formal terms, the Halting Problem can be expressed as follows:

HALTTM = {⟨M,w⟩∣M is a Turing Machine that halts on input w}

Let M be a Turing Machine and w be an input string. The Halting Problem entails a query as to whether there is a general algorithm that, given <M, w> (the encoding of machine M and input w), can decide on whether M halts on input w?

Assuming that this language is decidable, there would be an existing Turning Machine that would always halt (stop) and answer correctly whether “yes” or “no” for any <M, w> pair. However, Turing’s demonstrated that no such decider can exist, and the Halting Problem is undecidable (GeeksforGeeks, 2018).

Intuitively, think of creating a program that analyzes other programs. You would like to be informed whether a given program will terminate or will enter an infinite loop with a particular input.

For instance, assuming you wrote a program that sorts numbers, does the program always terminate? When developing a web server, is it expected to execute forever or might hang unexpectedly due to a bug. The Halting Problem emphasizes that there is no universal way to predict the termination for all possible programs and inputs [

15,

16,

17].

Although the Halting Problem is a mathematical theory that assumes the proceedings of a Turing Machine, the effects of this theory transcend into real-world computing. In software verification such as static analyzers attempts to detect infinite loops or bugs but cannot guarantee success due to problem undecidability. In Artificial Intelligence, systems are unable to universally predict their own behaviors, nor arbitrary code behavior pointing to fundamental computational barriers[

18,

19,

20]. Likewise, in compiler design, optimizations should not assume their application on whether particular code paths will be executed or not since this general case is undecidable. According to Aaronson, the Halting Problem serves as a reminder that despite the current advancement, computation will always have limitations that cannot be overcome (Manoharan, 2024).

With regards to Theory of Computation, the Halting Problem is important as it establishes that not every problem can be solved by algorithms. It introduces key proof techniques such as diagonalization and reduction, the essentials to understanding undecidability. It clarifies the difference between decidable and recognizable language. Briefly, the Halting Problem is the core of computability theory that demonstrates that there are certain questions which lie out of the bounds of computation and simply cannot be computed [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Proof of Undecidability

Turing Proof using Contradiction

Proof by contradiction is a deductive method aiming to prove a statement with the assumption of its negation, deriving a logical contradiction. This approach is used in computing theory to demonstrate that the Halting Problem is undecidable. We suppose there is a halting decider, and then produce a program that is contradictory to its own output. This is a paradox of self reference and it nullifies the initial premise. The arising contradiction proves the impossibility of the universal halting decider, and implies the fundamental limitations of algorithmic computing [

26,

27].

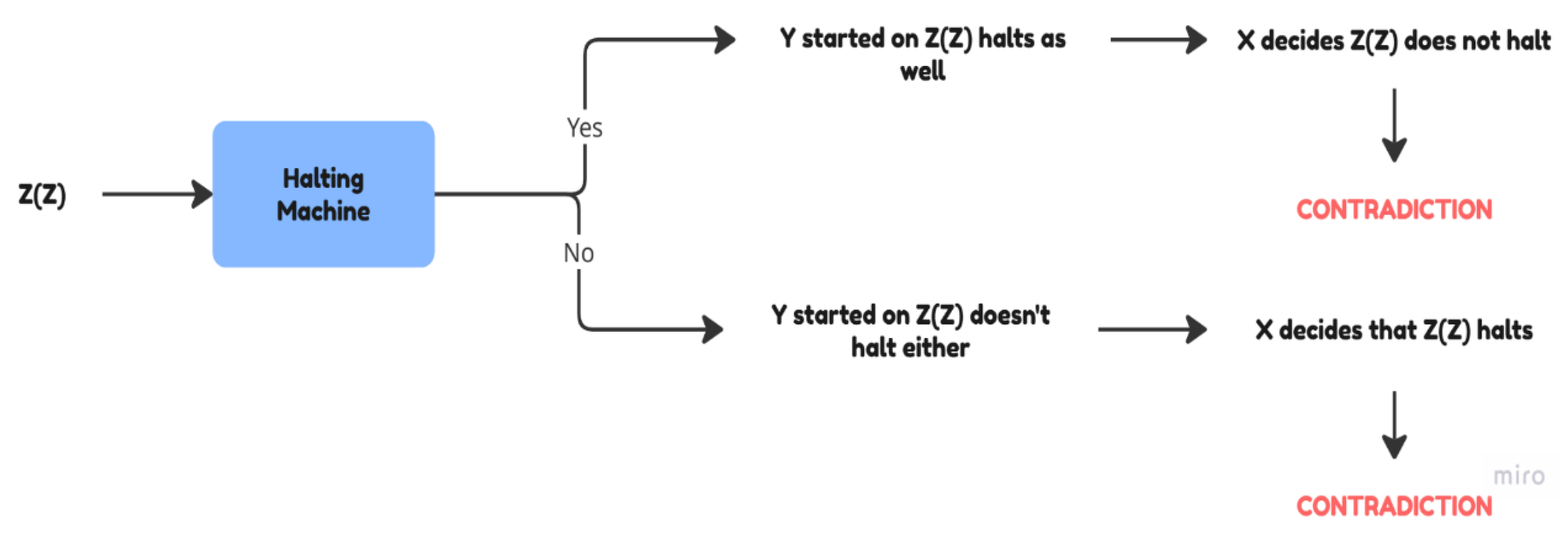

Suppose the halting problem is solvable, then an algorithm to solve that problem would exist, and by the ChurchTuring thesis a program(let’s call it

X) can be written to act on any program (

P) with data (

D) and produce as decision as to whether the program (P) started on data (D) ultimately halts or not. Now if we add instructions to (X) to create a new program (

Y), (Y) will modify the performance of (X) such that whenever (X) halts with a decision that (P) started on (D) halts, (Y) goes into an infinite loop. Now if (X) halts with a decision that (P) started on (D) does not halt, the (Y) will halt. Finally, we can create a new program (

Z) with input (P) - meaning to say that the input data for program (Z) is actually itself a program which is basically just data and nothing more and now when we try to run (Z) on (Z) there are two possible scenarios which are discussed below as follows:

Figure 4.

A simplified diagram of the first and second scenarios that is elaborated in detail below (Own Work).

Figure 4.

A simplified diagram of the first and second scenarios that is elaborated in detail below (Own Work).

First scenario: (Z) started on input (Z) halts.

If (Z) started on (Z) halts, then (Y) started on (Z) with input (Z) halts as well.

If (Y) started on (Z) with input (Z) halts, then (X) decides that (Z) started on (Z) does not halt.

Therefore (Z) started on input (Z) halts implies that (Z) started on input (Z) does not halt. This is a contradiction.

Second scenario: (Z) started on input (Z) does not halt.

If (Z) started on (Z) does not halt, then (Y) started on (Z) with input (Z) does not halt either.

If (Y) started on (Z) with input (Z) does not halt, then (X) decides that (Z) started on (Z) halts.

Therefore (Z) started on (Z) does not halt implying that (Z) started on (Z) as input halts. This is a contradiction as well.

To conclude the above two scenarios we can see that either way (i.e. (Z) started on (Z) halting or not halting) we get a contradiction (Butt, 2016).

Constructing a Hypothetical Decider and Deriving a Contradiction

Let H be a Turing machine which solves the HALT problem.

For any Turing machine (P) and input (I), H (P,I) halts and outputs:

“Halts”, if P (I) eventually terminates

“Loops”, if P(I) runs indefinitely

H is assumed to be a total (always halting) and correct for all possible inputs (P,I).

- 2.

Construction of the Contradictory Program D

Define a Turing machine D that takes as input the description of a Turing machine P and does the following:

Simulates H(P,P) - to determine if P halts when given its own description as input.

If H(P,P) = “Halts”, then D enters an infinite loop.

If H(P,P) = “Loops”, then D halts immediately.

- 3.

Deriving the Contradiction

Consider the execution of D with its own description as input (D(D)):

- ➢

-

Case 1: Assume D(D) Halts

By definition of H, this means H(D,D) = “Halts”.

But by construction, D(D) only halts if H(D,D) = “Loops”.

This is a contradiction as H cannot simultenuosly return “Halts” and “Loops”

- ➢

-

Case 2: Assume D(D) Loops Forever

By definition of H, this means H(D,D) = “Loops”.

But D(D) loops only if H(D,D) = “Halts”.

This is a contradiction as H cannot simultenuosly return “Loops” and “Halts”

To conclude, the logical inconsistencies that can be derived in both cases disprove the existence of H. The Halting Problem is undecidable as there is no Turing machine that can properly predict the halting behavior of all possible programs and all possible inputs.

The Proof by contradiction shows that the Halting Problem is undecidable by assuming there exists a hypothetical decider H and develops self-referential programs (D and Z) that drives H into logical contradictions. In either instance (the program halts or loops) the output of H is inconsistent with its definition and therefore H is not reliable. As no decider can correctly predict all the halting behavior without paradox, hence the initial assumption is false. The proof by contradiction establishes that the Halting Problem is undecidable, revealing the inherent limitation of algorithmic computation.

Conclusions

The Halting Problem is also a fundamental theme of the Theory of Computation (ToC) that determines the boundaries of the reasoning itself. In its most basic form, the Halting Problem poses the question: Is it possible to write a program which can tell us if any given program when presented with some input will ever stop running ( halt) or will just keep going? In 1936 the British mathematician Alan Turing gave a clear and deep “no” to this question. He established the non-existence of such a universal program, so that the Halting Problem was one of the earliest undecidable problems demonstrated formally.

Such an outcome is a limitation not only of theoretical interest: it has serious implications in real-world computing. It makes us know that there is no algorithm which can decide in all possible circumstances whether another algorithm terminates. What it implies is that there are some things that cannot be automated so as to be solved by any computer, however powerful. Turing also proved and came up with the concept of Turing Machines, a model that remains the foundation of comprehension of computation nowadays. The Halting Problem has a fundamental place in the Theory of Computer. It establishes a border between possible and impossible to solve computationally (decidable) and impossible to solve problems. The Halting Problem shows many other notoriously undecidable problems like the Post Correspondence Problem and the Word Problem for groups, to be undecidable, by encoding them in it. Halting Problem can, in this sense, serve as an undecidability base case in theoretical computer science. Moreover, Halting Problem lends you to more clarity about what the computation could or could not provide. It demonstrates that there are questions computers cannot respond to and the tasks they cannot fulfill, regardless of hardware and software development. This knowledge is essential in regions like software verification, the ethics of AI, and cybersecurity; here, an awareness of the scope of automation avoids the expenditure of unnecessary effort and undue hopefulness.

In conclusion, the Halting Problem cannot be described as a historical oddity because it remains one of the fundamental concepts that shape not only theoretical but also applied computer science. It shows us a modesty of facts: computers are amazingly mighty but not magic boxes that can resolve any issue. Knowing these limits are the intellectual spine of the Theory of Computation that can assist us in understanding the field clearly, with a very strong sense of realism, and with greater insight.

Author Contributions

Retaj Ahmed Moustafa Abdelsalam Mogahed—The Halting Problem, Document Finalization and Refinement; Rana Amr Aldayan—Proof of Undecidability; Amina Faisal—Conclusion; Syed Muhammad Dayyan Shah—Foundations of Computability; Noor Ul Amin—Proof of Undecidability; Theerthika Devi A/P Ananth—Introduction.

References

- GeeksforGeeks. Halting Problem in Theory of Computation. GeeksforGeeks. 3 October 2018d. Available online: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/theory-of-computation/halting-problem-in-theory-of-computa.

- Tutorialspoint.com Halting Problem in Automata Theory. 2025. Available online: https://www.tutorialspoint.com/automata_theory/automata_theory_halting_problem.htm.

- Gautam. Introduction to the Halting Problem, Baeldung on Computer Science. 2024. Available online: https://www.baeldung.com/cs/halting-problem.

- Sanders, S. On the computational properties of the Baire Category Theorem. arXiv.org. 2022. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.05251.

- Triantafyllou, S.A. Understanding and Designing Turing Machines with Applications to Computing, Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024; Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-48465-0_19.

- GeeksforGeeks. Turing Machine in TOC. GeeksforGeeks. 4 May 2016. Available online: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/theory-of-computation/turing-machine-in-toc/.

- Wong, K.K.L. ‘Turing Machine’. 2023, pp. 249–266. [CrossRef]

- Tourlakis, G. Computability. In Chapman & Hall/CRC Applied Algorithms and Data Structures Series; 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strnad, P. Online Turing Machine Recognition. Zamm-Zeitschrift Fur Angewandte Mathematik Und Mechanik 1970, 50, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, M.D.; Jarden, M. Undecidability, Springer Nature Switzerland; 2023; Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-28020-7_32.

- GeeksforGeeks. Halting Problem in Theory of Computation. GeeksforGeeks. 3 October 2018. Available online: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/theory-of-computation/halting-problem-in-theory-of-computa.

- Manoharan, I. (Ilak) (2024) 210. Halting Problem: Can We Predict a Program’s Fate? Medium. 30 March. Available online: https://medium.com/@ilakk2023/210-halting-problem-can-we-predict-a-programs-fate-7f887.

- Butt, S.Y. Halting problem, Purdue University (bepress). 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/295254085_Halting_problem.

- Tools and Algorithms for the Construction and Analysis of Systems. 2020. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-45190-5.

- Brohi, S.; Jhanjhi, N. Z.; Pillai, T. R. A Research Landscape of Agentic AI and Large Language Models: Applications, Challenges and Future Directions. Algorithms 2025, 18(8), 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, N.; Jhanjhi, N. Z.; Thampi, S. M.; Parikh, S.; Amin, K. (Eds.) Computing Science, Communication and Security: 5th International Conference, COMS2 2024, Mehsana, Gujarat, India, February 6–7, 2024, Proceedings; Springer Nature, 2024; Vol. 2174. [Google Scholar]

- Almufareh, M. F.; Jhanjhi, N. Z.; Khan, N. A.; Almuayqil, S. N.; Humayun, M.; Javed, D. BertSent: transformer-based model for sentiment analysis of penta-class tweet classification. In IEEE Access; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Almazroi, A. A.; Alsubaei, F. S.; Ayub, N.; Jhanjhi, N. Z. Inclusive Smart Cities: IoT-Cloud Solutions for Enhanced Energy Analytics and Safety. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science & Applications 2024, 15(5). [Google Scholar]

- Baligodugula, V. V. Unsupervised-based distributed machine learning for efficient data clustering and prediction; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Din, S. N. U.; Muzammal, S. M.; Bibi, R.; Tayyab, M.; Jhanjhi, N. Z.; Habib, M. Securing the Internet of Things in Logistics: Challenges, Solutions, and the Role of Machine Learning in Anomaly Detection. In Digital transformation for improved industry and supply chain performance; IGI Global, 2024; pp. 133–165. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, I. A.; Jhanjhi, N. Z.; Brohi, S. N. IoT smart healthcare security challenges and solutions. In Advances in Computational Intelligence for the Healthcare Industry 4.0; IGI Global Scientific Publishing, 2024; pp. 234–247. [Google Scholar]

- Niveshitha, N.; Amsaad, F.; Jhanjhi, N. Z. Air Quality Prediction in Smart Cities Using Cloud Machine Learning. 2023 Second International Conference On Smart Technologies For Smart Nation (SmartTechCon), 2023, August; IEEE, 2023; pp. 1115–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Razaque, A.; Frej, M. B. H.; Bektemyssova, G.; Almi’ani, M.; Amsaad, F.; Alotaibi, A.; Alshammari, M. Quality of Service Generalization using Parallel Turing Integration Paradigm to Support Machine Learning. Electronics 2023, 12(5), 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex, S. A.; Jhanjhi, N. Z.; Ray, S. K. Blockchain based e-medical data storage for privacy protection. International Conference on Mathematical Modeling and Computational Science, 2023, February; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore; pp. 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, M.; Gaur, L.; Chakrabarti, A.; Jhanjhi, N. Z. Unravelling the Barriers of human resource analytics: Multi-criteria decision-making approach. Journal of Survey in Fisheries Sciences 2023, 306–321. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur, L.; Rana, J.; Jhanjhi, N. Z. Digital twin and healthcare research agenda and bibliometric analysis. In Digital Twins and Healthcare: Trends, Techniques, and Challenges; 2023; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, S.; VijayKumar, H.; Akila, D.; Jhanjhi, N. Z.; Darwish, O. A.; Amsaad, F. Information-centric IoT-based smart farming with dynamic data optimization. Computers, Materials & Continua 2023, 74(1), 321–338. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).