1. Introduction

Over the last 15 years, mixture risk assessment for food xenobiotics has progressed from simple screening approaches towards component-based and probabilistic methodologies. This evolution reflects the recognition that consumers experience concurrent, lifelong dietary exposures to multiple chemicals—or “cocktails”—that may yield effects not captured by single-substance assessments (More et al., 2019; FAO&WHO Expert Consultation, 2019); Feron et al., 1995; Feron & Groten, 2002; Kortenkamp, 2022). Globalisation of food chains and use of pesticides, food contact materials and industrial chemicals have made anthropogenic substances ubiquitous in environmental and food matrices, with diet a dominant exposure route for pesticides, process contaminants, mycotoxins, metals and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) (Feron et al., 1995; Feron & Groten, 2002; Mattisson et al., 2018; UNEP, 2019; Arce-López et al., 2024; Schoeters et al., 2025). Within this broader exposome, the “combined exposure” paradigm explicitly addresses real-world mixtures and the “cocktail effect”, under which chemicals can interact additively, synergistically or antagonistically (Gruszecka-Kosowska et al., 2022; Ortiz et al., 2022; More et al., 2019; Bloch et al., 2023; Bopp et al., 2014, 2019; Kortenkamp, 2022).

At the toxicological level, mixture behavior is framed by two reference models: concentration (dose) addition and independent action (response addition) (Kortenkamp, 2022; Bloch et al., 2023). Dose addition posits that components act as dilutions of one another, sharing a similar mode of action, whereas independent action assumes statistically independent effects for chemicals acting through different pathways. A substantial experimental corpus indicates that, at low effect levels, predictions from these models often converge, with many environmental mixtures conforming reasonably well to dose addition even when modes of action are not strictly identical (Faust et al., 2013; Martin et al., 2021; Bloch et al., 2023; Kortenkamp, 2022). True synergy and strong antagonism do occur, but systematic evaluations indicate they are quantitatively limited and relatively infrequent at environmentally realistic doses, particularly for pesticide mixtures (Cedergreen, 2014; Martin, 2023). These findings underpin the widespread use of dose-additive, component-based methods as a conservative default for cumulative dietary risk assessment, while recognizing that interaction “hotspots” and data gaps remain (Sarigiannis & Hansen, 2012; Bopp et al., 2018; Massey et al., 2022).

Over the same period, major agencies have moved from largely theoretical discussions of chemical mixtures to operational cumulative risk assessment (CRA) frameworks. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and joint FAO/WHO initiatives now share a backbone based on tiered assessment, biologically informed grouping and default dose addition for substances with similar or overlapping effects (EFSA, 2013; More et al., 2019; FAO& WHO, 2019, 2007;FAO&WHO Expert Consultation, 2019; U.S. EPA, 2014, 2016, 2025a,b; UNEP, 2019). EFSA has pioneered developments in the food domain, establishing cumulative assessment groups (CAGs) for pesticides targeting the nervous system, thyroid and craniofacial development and embedding CRA in routine opinions (EFSA Panel on Plant Protection Products and their Residues (PPR), 2009, 2013; Crivellente et al., 2019; Cattaneo et al., 2023; Tosti et al., 2025). EPA’s common mechanism groups and relative potency factor (RPF) methodology for organophosphate and other pesticides represent a parallel, strongly quantitative tradition (U.S. EPA, 2025a, b; Boobis et al., 2008). FAO&WHO, through its Framework and Guidance for combined exposure to multiple chemicals in food, has sought to harmonize principles and provide scalable tools for countries with differing data infrastructures (FAO&WHO, 2021; UNEP, 2019).

Thus, combined-risk assessment for food-related chemical mixtures can be structured around two complementary approaches: the whole-mixture approach and the component-based approach. In the whole-mixture approach, a real mixture (e.g. a formulation or complex environmental extract) is treated as the test item, and hazard and risk are characterised directly from the observed effects of the entire mixture. By contrast, the component-based approach requires detailed information on each constituent’s identity, concentration and toxicity, including its assumed or established mode of action (MoA). For component-based assessments, chemicals that share similar MoAs and act on the same toxicological target are typically evaluated using dose-addition models, often combined with toxicity or potency factors and grouping into assessment groups. Chemicals with dissimilar MoAs that nonetheless contribute to a common endpoint are handled under independent-action concepts, which can be implemented either as response addition (probabilistic aggregation of component risks) or effect addition (summation of measured biological responses, with adversity boundaries commonly defined by NOAEL-type reference points). In practice, key elements of combined-risk characterization therefore include: analysis of co-exposure and co-occurrence patterns, grouping of substances into assessment groups, application of dose-addition models with toxicity/potency factors, and use of response- or effect-addition schemes depending on MoA similarity. Tralau et al. also emphasise the generation of co-exposure patterns for specific consumer subgroups (e.g. defined by lifestyle or dietary habits) to prioritize mixtures for assessment, while highlighting persistent data gaps and uncertainties in human relevance that complicate component-based evaluations. Real-world concerns such as reported cumulative hepatotoxicity from pesticide combinations are used to justify the need for proactive, methods-based mixture testing and exposome-informed co-exposure analyses to identify mixtures where hazards may otherwise be overlooked (Tralau et al., 2021).

In food safety, implementation of these frameworks depends critically on robust exposure data streams. Total Diet Studies (TDS) are central for characterizing chronic dietary exposure “as eaten” by selecting foods that cover ≥85–90% of intake, preparing them as consumed and pooling them into composite samples for multi-analyte analysis (W.H.O./F.A.O., 2011; World Health Organization et al., 2011; Egan, 2013). Harmonized guidance from WHO, FAO and EFSA, refined in European projects such as TDS-Exposure, has consolidated best practice on sampling, home-style preparation, pooling and left-censor handling (German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR), 2015; Vasco et al., 2021; Kolbaum et al., 2023). National TDS implementations show that such designs can yield realistic, policy-relevant exposure estimates for a broad spectrum of contaminants while maintaining analytical feasibility (Nougadère et al., 2020; Boon et al., 2022; Vasco et al., 2025a, b; Kolbaum et al., 2024). At the same time, loss of product-level resolution in TDS motivates their integration with conventional monitoring and model-based tools in cumulative assessments (Schendel et al., 2022; Schwerbel et al., 2022; Li et al., 2025).

Complementing external exposure data, human biomonitoring (HBM) quantifies internal exposure to diet-related xenobiotics in biological matrices, integrating all routes and sources of uptake (Mattisson et al., 2018; Apel et al., 2020; Tadić et al., 2025). Large initiatives such as HBM4EU and WHO/Europe have harmonized protocols, quality assurance and health-based guidance values (HBM-GVs), enabling mixture-aware assessments based on internal concentrations rather than external intake alone (Heinälä et al., 2017; Zare Jeddi et al., 2022, 2025; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, 2023; Santonen et al., 2023). Applications to PFAS, phthalates, bisphenols and mycotoxins illustrate how HBM links exposure, internal dose and risk characterization, combining serum or urinary measurements with PBPK modelling, guidance values and Total Diet Study data (EFSA, 2020a, 2020b; Xu et al., 2020; Abraham et al., 2024; Uhl et al., 2023; Dean et al., 2025; Gerofke et al., 2023, 2024; Govarts et al., 2023; Habschied et al., 2021; Turner & Snyder, 2021; Peris-Camarasa et al., 2025; Arce-López et al., 2024; Owolabi et al., 2024).

On this foundation, a suite of quantitative metrics has been operationalized to assess mixture risk under default dose additivity. These range from screening tools like the Hazard Index (HI) to refined approaches such as Relative Potency Factors (RPF), Toxic Equivalents (TEQ), the Maximum Cumulative Ratio (MCR), and the combined Margin of Exposure (MOET)

(Sarigiannis & Hansen, 2012; Ji et al., 2022; Massey et al., 2022; EFSA, 2020; Boobis et al., 2008; DeVito et al., 2024; Bil et al., 2021, 2023; Widjaja-van den Ende, 2025; Rampazzo et al., 2025; Benford et al., 2010; Vejdovszky et al., 2019; Beronius et al., 2020; Boberg et al., 2021; Bennekou et al., 2025; Massey et al., 2022; Backhaus, 2023; van der Voet et al., 2020; Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017; Cattaneo et al., 2023; van der Voet et al., 2020; EFSA, 2022; Benfenati et al., 2024; Kruisselbrink et al., 2025).

Despite these advances, mixture risk assessment remains characterized by substantial uncertainty. Parameter uncertainty arises from incomplete or variable toxicity data, co-exposure correlations and toxicokinetic variability; model uncertainty from metric choice, additivity assumptions and extrapolation frameworks; and scenario uncertainty from decisions on problem formulation, grouping, populations and exposure windows (Sarigiannis & Hansen, 2012; Committee on Decision Making Under Uncertainty, 2013; Heinemeyer et al., 2022; Massey et al., 2022). Recent guidance from EFSA and the U.S. National Academies stresses that explicit, tier-appropriate uncertainty analysis is integral to mixture assessment and that local and global sensitivity analyses are essential for identifying dominant “risk drivers” (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2018; Committee on Decision Making Under Uncertainty, 2013; Heinemeyer et al., 2022). Concurrently, research on risk communication highlights that reporting binary outcomes (e.g., HI < 1) is insufficient; stakeholders require transparent information on variability, residual uncertainty and the conditional nature of model assumptions, conveyed through clear narratives, ranges and graphical tools (Hart et al., 2019; Spiegelhalter, 2017; Hoet et al., 2019; RSI, n.d.). Thus, a consolidated framework integrating toxicology, exposure science, and regulatory policy is currently lacking.

Within this evolving landscape, this review synthesizes methodological and regulatory developments in mixture risk assessment for food xenobiotics. Specifically, it: (i) critically examines core combined-risk metrics and their underlying assumptions; (ii) compares leading regulatory frameworks for cumulative assessment (EFSA, EPA, WHO/FAO) and their degree of convergence; (iii) summarizes best practices and challenges for integrating Total Diet Studies and Human Biomonitoring into mixture assessments; (iv) discusses how “cocktail effect” theory is translated into operational grouping strategies, metrics and decision rules; and (v) outlines an agenda for uncertainty analysis, communication and future research, including the role of PBPK modelling and data-driven grouping approaches (More et al., 2019, 2021; FAO&WHO, 2019; Bopp et al., 2018, 2019; Cattaneo et al., 2023; Zare Jeddi et al., 2022; Santonen et al., 2023; Heinemeyer et al., 2022). By focusing specifically on food-relevant mixtures and integrating exposure, toxicology and regulatory perspectives, the review aims to support a transition from single-chemical paradigms to transparent, tiered and uncertainty-aware frameworks capable of managing real-world dietary “cocktails” of xenobiotics in a proportionate and scientifically robust manner.

3. Results

3.1. Key Metrics for Combined Risk

Assessing combined chemical risk presents a major challenge for toxicology, given that consumers are chronically exposed to complex mixtures rather than isolated substances. (Cattaneo et al., 2023; Yan et al., 2025). Traditional single-substance assessments therefore risk underestimating aggregate and cumulative effects. In response, a set of component-based metrics has been developed to operationalize mixture toxicity under the overarching assumption of dose (concentration) additivity and, where possible, common modes or targets of action. Prominent tools include the Hazard Index (HI), Relative Potency Factors (RPF) and Toxic Equivalents (TEQ), and combined exposure indicators such as the Maximum Cumulative Ratio (MCR) and Margin of Exposure for Total (MOET) (Ji et al., 2022; Sarigiannis & Hansen, 2012; Massey et al., 2022; EFSA, 2020; U.S. EPA, 2023). Their appropriate use is now central to EFSA, US EPA and other agencies’ tiered frameworks for cumulative risk assessment (EFSA, 2022; EFSA Scientific Committee, 2024; Backhaus, 2023).

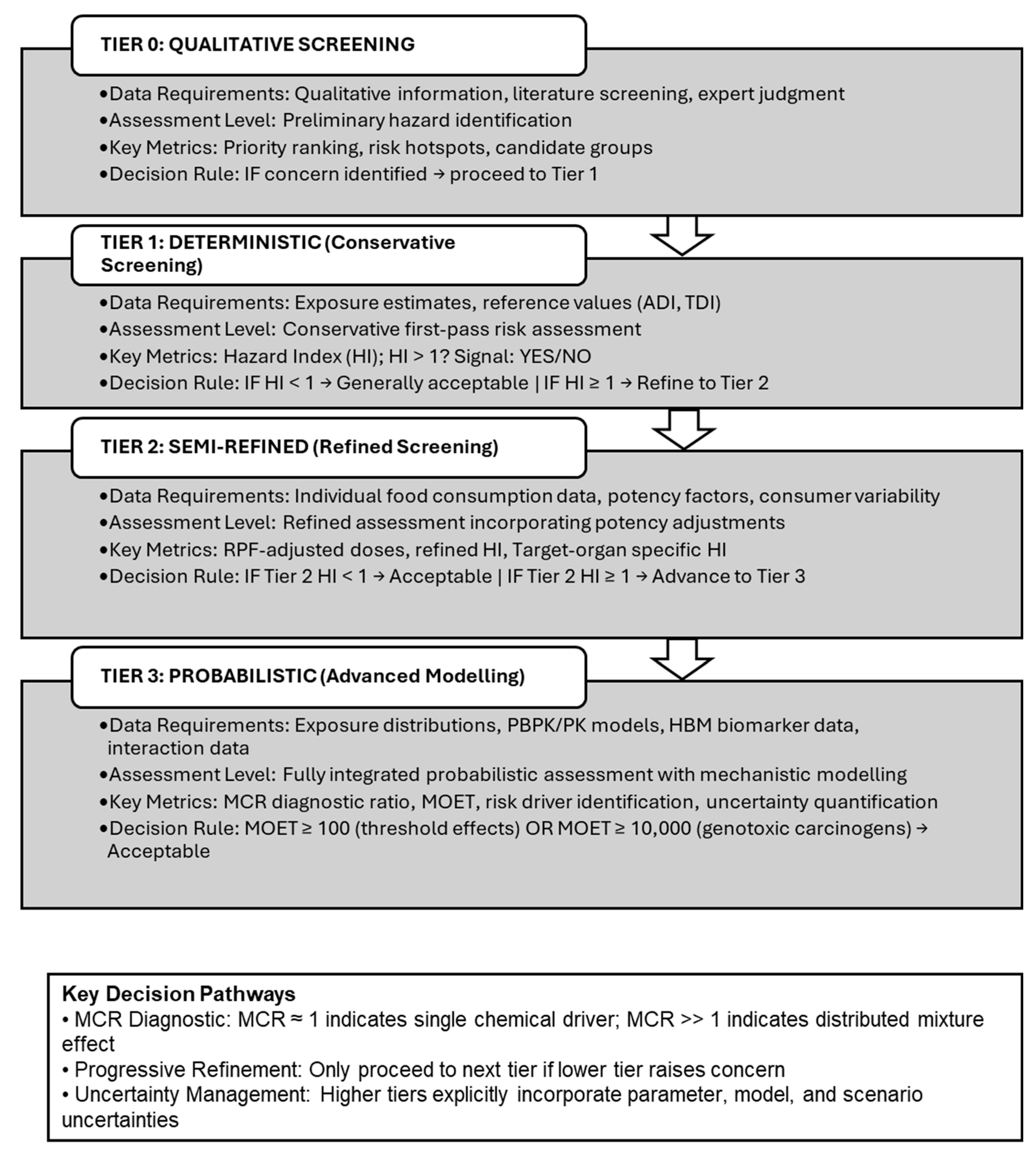

At the exposure level, EFSA (2013) proposed a three-tier paradigm (

Figure 1) ranging from conservative deterministic estimates (Tier 1), through semi-refined calculations using individual-level consumption data and variability across consumers (Tier 2), to fully probabilistic assessments (Tier 3) that combine distributions of chemical occurrence with food-consumption patterns. Higher-tier assessments may explicitly integrate spatial–temporal variability, physiologically based toxicokinetic models that link external exposure to internal dose, and, where available, human biomonitoring data and biomonitoring equivalents to characterize internal exposure distributions for mixture risk assessment (European Food Safety Authority, 2013).

The Hazard Index (HI) is the most established screening tool for mixture risk in food and environmental matrices. It is based on the sum of individual Hazard Quotients (HQᵢ), each defined as the ratio of an exposure estimate to a health-based reference value (e.g., ADI, TDI or reference dose):

Under dose-addition, a HI > 1 is typically interpreted as a signal of potential concern that warrants refined assessment or risk-management scrutiny (Nikolopoulou et al., 2023; Boberg et al., 2021; U.S. EPA, 2023). Because it only requires exposure distributions and reference values, HI is particularly attractive for low-tier assessments and for heterogeneous datasets where detailed toxicological information or interaction data are sparse (Ji et al., 2022; Sarigiannis & Hansen, 2012; Massey et al., 2022). Its transparency and conservative nature explain its wide uptake in regulatory guidance from EFSA and US EPA for cumulative exposure scenarios (EFSA, 2020; EFSA Scientific Committee, 2024).

However, the apparent simplicity of the HI masks several important limitations. First, reference values are derived using different datasets, endpoints, uncertainty factors and protective assumptions, so summing HQs can obscure heterogeneity in underlying data quality and embedded safety margins (Sarigiannis & Hansen, 2012; Massey et al., 2022). Second, HI is a relative indicator of proximity to reference values rather than a predictor of specific biological responses, and it does not explicitly incorporate synergistic, antagonistic or other interaction terms (Hertzberg et al., 2024; Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017). Third, the requirement for common or at least compatible endpoints may lead to focusing on a limited set of critical effects while overlooking broader systemic outcomes (Boberg et al., 2021). Recent developments aim to increase the mechanistic fidelity of HI-type approaches by integrating toxicokinetic information and physiologically based (pharmaco)kinetic (PB(P)K) models, thereby refining internal dose metrics and reducing reliance on external exposure surrogates (Boone et al., 2025; Ji et al., 2022; Hertzberg et al., 2024). Even with these constraints, HI remains a pivotal entry-level instrument for benchmarking concurrent exposures in food and environmental risk assessment, especially when mixture toxicity is considered alongside other evidence streams (Cattaneo et al., 2023; EFSA Scientific Committee, 2024).

EFSA’s 2013 analysis explicitly formalized the additivity assumptions that underpin most combined-risk metrics. For chemicals sharing a common target or mode of action, dose addition is applied, whereas response addition is reserved for components acting through independent modes of action. (EFSA, 2013). Thus, although easy to apply and anchored in health-based guidance values, the Hazard Index is only a relative indicator of joint risk: it does not predict the magnitude of health effects when group HBGVs are exceeded and is restricted to chemicals for which such guidance values are available. To address end-point specificity, the Target-organ Toxicity Dose concept refines the HI by using endpoint-specific reference points, leading to separate HIs for different organs or critical effects. Where robust interaction data exist, EFSA also described extensions such as interaction-based HIs and binary-interaction modifiers, which adjust individual hazard quotients to reflect toxicokinetic or toxicodynamic departures from simple additivity (EFSA, 2013).

Relative Potency Factors (RPF) and Toxic Equivalents (TEQ) provide more refined tools where mixtures share a common mode of action and robust dose–response data are available. In the RPF framework, each component is normalized to an index compound based on a shared endpoint and comparable study designs; exposures are then expressed as “index-compound equivalents” that can be summed to obtain a total equivalent dose (U.S. EPA, 2025a, b; Boobis et al., 2008; Massey et al., 2022). The TEQ concept is a specialized implementation of this approach and underpins the Toxic Equivalency Factor (TEF) system used for dioxins and dioxin-like PCBs, which act through activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) (DeVito et al., 2024; Widjaja-van den Ende, 2025). Analogous RPF/TEQ-type schemes have been explored for other chemical families such as PFAS, organophosphate insecticides and further emerging contaminants with similar toxicodynamic profiles (Bil et al., 2021, 2023; Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017; Massey et al., 2022; Widjaja-van den Ende, 2025).

The robustness of RPF and TEQ metrics depends critically on the choice of index compound, the quality and coherence of dose–response data across mixture constituents, and the validity of key assumptions (U.S. EPA, 2025a, b; Boobis et al., 2008; Massey et al., 2022). In particular, dose additivity is typically assumed, so non-additive interactions may be missed (Bil et al., 2021, 2023). Moreover, toxicokinetic and inter-individual variability can undermine the comparability of external doses, especially when extrapolating across life stages or populations. To address these challenges, recent work has integrated PBK models and toxicokinetic data into RPF/TEQ derivations, improving internal-dose equivalence across chemicals (Bil et al., 2021, 2023; DeVito et al., 2024). In parallel, computational toxicology resources such as the US EPA’s CompTox Chemicals Dashboard, combined with in vitro assays, QSAR models and read-across approaches, are increasingly used to support or approximate potency factors for data-poor chemicals (Rampazzo et al., 2025; U.S. EPA, 2023). These advances extend the reach of RPF/TEQ approaches beyond classical dioxin-like compounds towards broader groups of emerging pollutants, while retaining regulatory compatibility (EFSA, 2020; Widjaja-van den Ende, 2025).

Beyond these component-scaled metrics, combined exposure indicators such as the Maximum Cumulative Ratio (MCR) and Margin of Exposure for Total (MOET) offer complementary perspectives on mixture risk. MCR is defined as the ratio between the combined risk estimate for the mixture and the risk estimate for the single most contributing component. Values close to 1 indicate that overall risk is dominated by one “driver” compound and that a single-substance approach may capture most of the mixture hazard, whereas higher MCR values signal more distributed contributions and highlight the added value of full mixture modelling (Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017; Massey et al., 2022; Kruisselbrink et al., 2025). In practice, MCR is mainly used as a diagnostic metric to prioritise which mixtures or scenarios require more advanced assessment, including in food, environmental and other high-risk process-industry contexts (Cattaneo et al., 2023; Kruisselbrink et al., 2025).

The MOET consolidates individual Margins of Exposure (MOEᵢ) for mixture components without simply multiplying or compounding generic assessment factors. It is typically defined as:

where MOEᵢ is the ratio between a toxicological point of departure (PODᵢ) and exposureᵢ for each component (Beronius et al., 2020; Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017). Interpretation usually follows pragmatic benchmarks aligned with regulatory precedent: for example, MOET ≥ 100 is often considered adequate for threshold toxicants, whereas MOET ≥ 10,000 is a common target for genotoxic carcinogens, mirroring single-substance risk assessment practices (Benford et al., 2010; Hoet et al., 2019; Bennekou et al., 2025). A key strength of MOET is that it aggregates margins in a way that respects their probabilistic meaning and avoids double-counting uncertainty factors across components (Beronius et al., 2020; Massey et al., 2022). However, its implementation requires comparable and reasonably harmonized PODs across substances—ideally benchmark dose (BMD)-based—which can be a substantial constraint when toxicological data are patchy or heterogeneous (Ji et al., 2022; Bennekou et al., 2025; Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017).

Decision rules for the Combined Margin of Exposure (MOET) are derived directly from the summation of individual risk reciprocals:

In regulatory practice, if the resulting MOET > 100 (for threshold effects where individual MOEs are based on NOAELs/BMDLs and a standard 100-fold uncertainty factor applies), the combined risk is generally considered acceptable. Conversely, for genotoxic carcinogens, a magnitude of MOET ≥10,000 is typically required to conclude a low concern for public health.

A pertinent extension of this metric is the Reference Point Index (RPI) or Point of Departure Index (PODI). Unlike the HI, which sums hazard quotients based on health-based guidance values, the RPI sums the ratios of exposure to a toxicological reference point (RP), such as a NOAEL or BMDL:

Under this formulation, the combined risk is essentially the inverse of the Margin of Exposure for the mixture (RPI = 1/MOET). This metric is particularly useful in component-based assessments where harmonized health-based guidance values are lacking for all components, but comparable Points of Departure are available.

Within this scheme, mixtures are generally considered adequately controlled when the RPI remains below 1, equivalently when the MOET exceeds the composite uncertainty factor, typically of the order of 100 for threshold effects. For genotoxic carcinogens, the report noted that MOE values around 10,000 or higher, when derived from a BMDL10, have been used as benchmarks of low concern from a public-health perspective (EFSA, 2013).

The practical use of MCR and MOET is tightly coupled to data integration tools. EFSA guidance explicitly recommends embedding these metrics within tiered cumulative risk assessment schemes, using them first for broad screening and prioritization, and then for refined, probabilistic evaluations (EFSA, 2020; EFSA, 2022). Probabilistic exposure tools such as the MCRA toolbox demonstrate how integrated exposure and effect databases can be exploited to simulate realistic co-exposure distributions and to explore the sensitivity of MCR and MOET to different uncertainty assumptions (van der Voet et al., 2020). In parallel, curated toxicological repositories such as OpenFoodTox facilitate the harmonization of PODs and uncertainty factors across large chemical sets, thereby improving consistency in MOET applications (Benfenati et al., 2024; EFSA, 2022). Together with advances in computational toxicology and kinetic modelling, these infrastructures are central to the RACEMiC roadmap’s vision of more coherent, cross-sector mixture methodologies (EFSA, 2022; Kruisselbrink et al., 2025).

Selecting appropriate metrics for a given mixture assessment is therefore not a purely technical choice, but a strategic decision that shapes the interpretability, regulatory relevance and protective capacity of the evaluation. HI remains highly suited to preliminary screening whenever reference values are available and chemicals share at least broadly similar endpoints, offering a conservative first filter for prioritizing mixtures and identifying “hot spots” in food and environmental exposure (Nikolopoulou et al., 2023; Ji et al., 2022; EFSA, 2020). RPF and TEQ approaches are preferable when mixtures belong to well-characterized families with common modes of action and robust dose–response datasets, as in the case of dioxins, dioxin-like PCBs and some pesticide groups (U.S. EPA, 2025a, b; Boobis et al., 2008; Widjaja-van den Ende, 2025; DeVito et al., 2024). MCR and MOET, in turn, are best suited to more refined assessments in which harmonized PODs can be established and there is a need either to diagnose the relative importance of mixture components (MCR) or to obtain a single, aggregated margin of exposure (MOET) that can be directly compared with traditional regulatory benchmarks (Beronius et al., 2020; Bennekou et al., 2025; Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017; Massey et al., 2022).

Across all these tools, it is essential to remain explicit about the underlying assumptions—especially dose additivity and the frequent neglect of interaction effects—and about the uncertainties introduced by data gaps, model choices and toxicokinetic variability ((Bil et al., 2021, 2023; Backhaus, 2023; Hertzberg et al., 2024). Modern frameworks therefore increasingly rely on a portfolio of metrics rather than a single indicator, using HI and MCR for screening, RPF/TEQ where mechanistic coherence permits, and MOET for integrated margins in high-priority scenarios, all embedded in probabilistic and scenario-based modelling platforms such as MCRA and supported by evolving regulatory guidance (van der Voet et al., 2020; EFSA, 2022; EFSA Scientific Committee, 2024; U.S. EPA, 2023). This multi-metric, tiered approach offers a scientifically defensible and transparent basis for managing mixture risks in food safety and other high-risk sectors, while remaining flexible enough to incorporate emerging methods and new groups of concern.

3.2. Toxicological Challenges: Synergy and Grouping

At the toxicological level, consensus has coalesced around Concentration Addition (CA) as the default pragmatic model, supported by evidence that it conservatively predicts mixture toxicity at low doses (Martin et al., 2021; Kortenkamp, 2022; Bloch et al., 2023).

Dose Addition (often referred to as Simple Similar Action or Loewe Additivity) assumes that components behave as dilutions of one another, sharing a common Mode of Action (MOA); individual doses are expressed relative to their effect-producing levels and summed. In contrast, Response Addition (Simple Dissimilar Action or Bliss Independence) assumes that chemicals act via independent MOAs, where the combined effect is calculated probabilistically from individual responses.

While Response Addition is conceptually robust for dissimilar mechanisms, it is seldom used directly in routine human risk assessment because standard reference values (NOAELs, BMDLs) typically lie below the threshold of observable responses.

Thus, CA assumes that components behave as dilutions of each other because they share a common mode of action (MOA) or adverse outcome pathway (AOP); IA assumes statistically independent responses for chemicals acting through different MOAs. CA has become the default regulatory assumption for many cumulative assessments due to its mathematical simplicity, its conservative nature and extensive empirical support, particularly at low effect levels (Bopp et al., 2014; Bloch et al., 2023; More et al., 2019). Numerous experimental datasets show that CA and IA predictions converge for effect levels below roughly 10–30%, which correspond to typical benchmark response levels used for regulatory PODs (Faust et al., 2013; Bloch et al., 2023; Martin et al., 2021). Moreover, careful analyses indicate that strict MOA homogeneity is not a prerequisite for CA to hold chemicals with ostensibly different MOAs often behave additively when normalized for potency, challenging rigid MOA-based dichotomies (van Leeuwen, 1995; Kortenkamp, 2022; Bloch et al., 2023; More et al., 2019).

Synergy and antagonism represent deviations from these additivity models, with combined effects exceeding or falling below CA/IA predictions, respectively. Mechanistically, such deviations can arise from toxicokinetic interactions (altered absorption, metabolism, distribution or elimination) or toxicodynamic interactions at the target tissue (competitive binding, receptor cross-talk, changes in signal transduction) (Feron & Groten, 2002; Braeuning & Marx-Stoelting, 2021). Systematic evaluations of pesticide mixtures show that genuine synergy does occur but is quantitatively limited and relatively infrequent under environmentally relevant conditions. Empirical evidence suggests that genuine synergy is rare at environmentally relevant doses; for instance, a landmark review of 194 pesticide mixtures found synergy in only ~7% of cases (Cedergreen, 2014). Larger meta-analyses of more than 1200 mixture experiments confirm that departures from additivity exceeding a factor of two are rare, especially in the low-dose range relevant for dietary exposure (Martin et al., 2021, 2023; Braeuning & Marx-Stoelting, 2021; Kortenkamp, 2022; Bloch et al., 2023). Nonetheless, specific combinations—such as certain triazine, azole and pyrethroid pesticides—have shown synergistic potential, underscoring the need for case-by-case scrutiny (Martin et al., 2021). Endocrine-disrupting mixtures can also elicit effects below individual NOAELs under particular experimental designs, although strong synergy under realistic dietary exposures appears uncommon (Vinggaard et al., 2015; Bopp et al., 2018; Sabbioni et al., 2022). Overall, the weight of evidence suggests that dose addition is a sufficiently conservative starting point for most food-relevant mixtures, while acknowledging that synergy cannot be excluded a priori in specific contexts (Sarigiannis & Hansen, 2012; Massey et al., 2022; Martin et al., 2021, 2023).

Operationalizing mixture assessment at regulatory scale has led to the development of Cumulative Assessment Groups (CAGs), which cluster chemicals into units for joint evaluation based on shared toxicological properties. CAGs may be defined by common target organ or critical effect (e.g., neurotoxicity, thyroid disruption), common MOA/AOP (e.g., organophosphates as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors), shared toxicodynamic outcome (e.g., estrogenic endocrine disruptors), or structural similarity that supports read-across (Bopp et al., 2014; Braeuning & Marx-Stoelting, 2021; Evans et al., 2016; More et al., 2021; Crivellente et al., 2019). EFSA’s guidance formalizes a tiered, mechanistically informed grouping strategy that prioritizes MOA/AOP evidence, followed by target-organ effects when mechanistic data are incomplete, with chemical class and structure as supporting information (More et al., 2019, 2021; EFSA PPR, 2009, 2013; Crivellente et al., 2019). In parallel, the concept of common kinetic groups (CKGs) has gained importance to capture toxicokinetic interactions such as enzyme induction or inhibition that may modify internal doses across multiple substances (Braeuning & Marx-Stoelting, 2021; Evans et al., 2016; Tosti et al., 2025).

In practice, constructing CAGs is constrained by data gaps: for an estimated 60–70% of environmental chemicals, detailed mechanistic information is lacking, many substances act via multiple MOAs, and co-exposure data are sparse, so that CAGs may bundle substances that rarely co-occur in real diets (Kortenkamp, 2022; Bloch et al., 2023; Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017). Recent methodological advances propose dynamic, data-driven grouping using network analysis and machine learning to identify clusters that maximize both toxicological similarity and real-world co-exposure, building on large monitoring and biomonitoring datasets (Bloch et al., 2023; Santonen et al., 2023). Whatever the grouping strategy, coherent aggregation of hazard and exposure information requires careful selection and harmonization of Points of Departure (PODs). Robust POD selection prioritizes the most sensitive, well-characterized endpoints, giving preference to benchmark dose (BMD) metrics—particularly BMDLs—over NOAEL/LOAEL values because BMD methods exploit the full dose–response curve and provide explicit statistical uncertainty (Slob & Pieters, 1998; Sand et al., 2018; Boobis et al., 2008; Hernández & Tsatsakis, 2017; Vejdovszky et al., 2019; Bopp et al., 2019). Within a CAG, PODs should, as far as possible, be aligned in terms of species, study duration and endpoint definition; marked heterogeneity can necessitate excluding particular studies or substances from quantitative aggregation (Boobis et al., 2008; U.S. EPA, 2025a, b; EFSA PPR, 2009; Klaveren et al., 2019; Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017; Tosti et al., 2025).

Where CAG members share a broadly similar MOA but differ in potency, Relative Potency Factors (RPFs) provide a pragmatic way to normalize exposures to a common index chemical, enabling calculation of toxic equivalents. RPF and related Toxic Equivalency Factor (TEF) schemes have been applied to dioxin-like compounds, PAHs, halogenated flame retardants and, more recently, PFAS, with index chemicals chosen based on robust toxicological datasets (Boobis et al., 2008). For PFAS, RPF approaches explicitly integrate differences in bioaccumulation and toxicokinetic across co-occurring congeners, allowing comparison of aggregate exposures from drinking water and diet against health-protective thresholds and informing remediation priorities where exceedances are likely.

The choice of risk metrics is central to translating CAG-based hazard characterization and exposure estimates into decision-relevant outputs. Regarding metric performance, comparative studies indicate that while HI remains the standard screening tool, MOET offers superior biological interpretability and avoids the obscuring of uncertainty inherent in summing Hazard Quotients (Vejdovszky et al., 2019; Bopp et al., 2019; Massey et al., 2022; Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017; Hoet et al., 2019). An HI > 1 is often interpreted as a signal of potential concern, with HI ≤ 1 taken as “acceptable”. However, critical analyses have highlighted several limitations: HI assumes perfect dose addition, aggregates across potentially disparate endpoints, offers no explicit probabilistic or biological interpretation of the threshold at 1, and obscures uncertainty in both exposure and reference values (Vejdovszky et al., 2019; Boberg et al., 2021; Bopp et al., 2019; Sarigiannis & Hansen, 2012; NRC, 2013). Furthermore, reference values themselves are derived from heterogeneous assessment factors and data quality, so HI is best regarded as a screening-level indicator rather than a predictor of population-level effect, particularly when used without explicit uncertainty analysis (Sarigiannis & Hansen, 2012; Massey et al., 2022; Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017).

Margin-of-Exposure–based metrics, notably the combined Margin of Exposure Total (MOET or nMOET), have gained prominence as more informative alternatives for refined, component-based cumulative assessments (Vejdovszky et al., 2019; Bopp et al., 2014; Hoet et al., 2019; Bennekou et al., 2025). For single substances, the MOE links exposure directly to a benchmark dose associated with a specified response level (often 10%), and its interpretation is straightforward: a MOE of 100 implies that the current exposure is 100-fold below the dose associated with the benchmark effect. For mixtures, MOET is calculated as the reciprocal of the sum of reciprocals of component MOEs, reflecting dose-addition principles (Bopp et al., 2014; Vejdovszky et al., 2019). This formulation preserves a clear probabilistic and biological meaning, aligns naturally with default uncertainty factors (e.g., MOE ≥100 for threshold toxicants; ≥10,000 for genotoxic carcinogens), and facilitates identification of “risk drivers” through contribution analysis of individual MOEs (Hoet et al., 2019; Vejdovszky et al., 2019; Boberg et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2024; Bennekou et al., 2025). Comparative studies indicate that MOE/MOET metrics perform at least as well as, and often better than, HI in capturing apical toxicological outcomes across diverse environmental mixture datasets (Vejdovszky et al., 2019; Boberg et al., 2021; Bennekou et al., 2025). Nonetheless, MOET thresholds remain pragmatic guides rather than absolute safety lines; their interpretation must explicitly account for cumulative uncertainty (Hoet et al., 2019; Heinemeyer et al., 2022; Sarigiannis & Hansen, 2012; NRC, 2013; Massey et al., 2022).

Case studies illustrate both the feasibility and constraints of implementing these concepts in routine risk assessment. EFSA’s cumulative assessments for triazole fungicides and other pesticide CAGs have applied dose addition, BMD-based PODs, RPF scaling and MOET-type metrics to large monitoring datasets, highlighting typical challenges such as data gaps, aggregate exposure uncertainty and the dominance of a few compounds in overall risk (EFSA PPR, 2009, 2013; Bopp et al., 2014; More et al., 2019, 2021; Crivellente et al., 2019; Klaveren et al., 2019; Bloch et al., 2023). Similar patterns emerge in cumulative dietary exposure analyses for endocrine disruptors and other priority groups, where a small subset of chemicals often contributes disproportionately to HI or MOET, guiding risk-management efforts toward targeted substitution or control of these “risk drivers” (Vejdovszky et al., 2019; Boberg et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2024). In non-dietary contexts, such as occupational pesticide use, mixture exposure is characterized by route-specific patterns and intermittent high-exposure “mixing events”, requiring tailored study designs and integration of job-specific scenarios (Tosti et al., 2025). Incorporating human biomonitoring and epidemiological data into these assessments strengthens the linkage between external exposure metrics and internal dose–response relationships, enabling validation of model predictions at realistic exposure levels (Hernández & Tsatsakis, 2017; Vejdovszky et al., 2019; Bopp et al., 2019; Santonen et al., 2023; Heinemeyer et al., 2022).

3.3. Regulatory Frameworks for Cumulative Risk Assessment

Over the last decade and a half, regulatory approaches to chemical mixtures have evolved from largely conceptual discussions into operational frameworks embedded in major food safety and public health agencies. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and joint WHO/FAO initiatives now share a common methodological backbone built on tiered assessment, mechanism- or effect-based grouping of chemicals, and dose addition as the default model for substances with similar or overlapping modes of action (More et al., 2019; FAO&WHO, 2019). Within this shared architecture, the agencies differ in scope, data infrastructure, and degree of legal enforceability, leading to complementary but not yet fully harmonized implementations of cumulative risk assessment (CRA) for pesticides and other food-borne xenobiotics (Hoet et al., 2019; NRC, 2013).

3.3.1. European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)

EFSA’s 2013 international review synthesized these developments into a generic tiered framework for combined exposure and risk, spanning qualitative tier-0 screens to fully probabilistic tier-3 assessments. Within this structure, two overarching hazard strategies are distinguished: whole-mixture assessment when adequate toxicity data exist for the tested or a sufficiently similar mixture, and component-based assessment when dose–response information is available for individual substances. Component-based assessments rely on defining Cumulative Assessment Groups or Assessment Groups (CAGs/AGs), ideally based on shared target organs and modes or mechanisms of action, to delineate which chemicals are combined in a given cumulative evaluation (EFSA, 2013) Methodologically, two overarching strategies are distinguished depending on data availability. The Whole Mixture Approach treats the entire mixture as a single entity—accounting for unidentified components and inherent interactions—and is applied when toxicological data exists for the specific mixture or a virtually identical one. Conversely, the Component-Based Approach is employed when toxicity and exposure data are available for individual constituents, relying on their grouping into Cumulative Assessment Groups (CAGs) based on weight-of-evidence, dosimetry, or mechanistic data.

EFSA’s 2019 guidance represents one of the most comprehensive attempts to operationalize CRA in routine regulatory practice. It formalizes a tiered scheme that combines component-based and whole-mixture approaches, using dose addition as the default assumption for chemicals acting on a common target or effect, while allowing response addition where mechanisms are clearly dissimilar (More et al., 2019). A central innovation is the concept of Cumulative Assessment Groups (CAGs), defined on the basis of shared toxicological endpoints or mechanistic concordance, which allows transparent grouping of active substances for joint evaluation (More et al., 2021).

Early EFSA work on pesticides laid the foundations for these CAGs, particularly for compounds affecting the nervous system and thyroid, demonstrating that such groupings could be implemented in routine opinions (EFSA Panel on Plant Protection Products and their Residues (PPR), 2009; EFSA Panel on Plant Protection Products and their Residues (PPR), 2013). Subsequent applications extended CRA to more specific developmental outcomes, such as craniofacial malformations, and to complex exposure scenarios, thereby illustrating both scientific feasibility and regulatory relevance (Crivellente et al., 2019; Tosti et al., 2025).

EFSA’s framework is tightly integrated into the EU risk assessment cycle and supported by rich dietary exposure databases and probabilistic tools. Recent initiatives, such as the RACEMiC roadmap, further emphasize systematic uncertainty analysis, probabilistic modelling, and transparent communication of cumulative risks to decision-makers and the public (EFSA, 2022). This combination of structured grouping principles, quantitative methodology, and legal embedding makes EFSA’s approach a reference point for CRA in food-related mixtures.

3.3.2. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

The U.S. EPA has pioneered mixture assessment within pesticide regulation, particularly through its work on organophosphate insecticides. Its cumulative risk paradigm is firmly rooted in “common mechanism groups”, in which pesticides are grouped by a shared mode of action and assessed collectively (U.S. EPA, 2025a, b; Boobis et al., 2008). Within these groups, the EPA typically combines exposures using Relative Potency Factors (RPFs) to normalize doses to an index compound, and often expresses combined risk via hazard indices, provided that the toxicological endpoint, test species, and study conditions are sufficiently comparable to support relative potency assumptions (Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017).

The U.S. EPA cumulative-risk framework operates as a predominantly component-based, dose-additive system that can be extended to interaction-adjusted indices. Whole-mixture assessment is applied when mixture-specific reference doses, reference concentrations or cancer slope factors are available, whereas component-based assessments group chemicals into assessment groups defined by common sources, target organs or modes of action. The framework explicitly encourages integration of multiple routes and timings of exposure, use of internal-dose measurements to reconcile aggregate exposure across routes, and the application of statistical tools such as categorical regression to model multi-endpoint responses, all underpinned by systematic problem formulation and explicit analysis of variability and uncertainty (EFSA, 2013).

This approach is strongly quantitative and data-driven, focusing on pesticide families with well-characterized hazard and exposure profiles. Over time, the EPA has incorporated more sophisticated modelling components, including probabilistic dietary and residential exposure assessments and the use of high-throughput screening and exposure models (e.g., ToxCast and ExpoCast) to inform grouping and prioritization (U.S. EPA, 2016, 2020). As a result, EPA’s framework is one of the most operationalized in terms of completed cumulative assessments but remains largely restricted to pesticides and other domains where mechanistic evidence and exposure data are robust. This domain specificity highlights both the strengths and the boundaries of mechanism-centered, RPF-based CRA.

3.3.3. WHO/FAO International Frameworks

At the international level, WHO and FAO have assumed a primarily normative and facilitative role, aiming to harmonize terminology, core principles, and practical approaches to CRA across countries with very heterogeneous regulatory capacities. The FAO/WHO 2019 Framework and subsequent guidance documents propose a proportionate stepwise process for combined exposure and risk assessment, anchored in explicit problem formulation, tiered exposure characterization, and transparent documentation of uncertainties (FAO&WHO, 2019, 2021).

These documents endorse dose addition as the default model for chemicals with similar modes or mechanisms of action, in line with EFSA and EPA practice, while acknowledging the need for pragmatic simplifications in data-poor settings (Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017). A key feature is their resource-sensitive orientation: the guidance explicitly distinguishes between basic screening tiers—suitable for low- and middle-income countries with limited data and modelling infrastructure—and more advanced tiers that can be implemented where national systems and datasets permit. Through the Codex Alimentarius system and related capacity-building initiatives, WHO/FAO seeks to embed cumulative assessment principles into international food safety standards and trade frameworks, promoting gradual convergence without imposing unrealistic technical demands (FAO&WHO, 2019, 2021; UNEP, 2019).

3.3.4. Convergence and Divergence

Despite differing mandates, EFSA, EPA, and WHO/FAO converge on core methodological pillars, most notably the endorsement of tiered assessment schemes and mechanism-based grouping (More et al., 2019; FAO&WHO, 2019). Grouping strategies are consistently based on shared mechanisms or health outcomes, whether framed as CAGs, common mechanism groups, or effect-based clusters—reflecting a broad consensus that mixture assessment should be biologically informed rather than purely structural. Dose addition is universally recognized as the default model for mixtures of similarly acting chemicals, with response addition reserved for clearly independent modes of action (More et al., 2019; Boobis et al., 2008).

Where the frameworks diverge is in breadth of application, legal embedding, and depth of quantitative implementation. EFSA has integrated CRA into its routine regulatory cycle for pesticides and is extending it to other contaminant domains, underpinned by comprehensive European dietary datasets and probabilistic tools (EFSA, 2022). EPA’s framework is narrower but particularly advanced for specific pesticide classes, leveraging RPFs, hazard indices, and high-throughput data streams (U.S. EPA, 2016, 2020, 2025a, b). WHO/FAO, in contrast, emphasizes globally applicable principles and scalable methods to ensure that countries with limited infrastructure can still implement scientifically defensible CRA, even if at simplified tiers (FAO&WHO, 2019, 2021).

These differences also reflect distinct decision contexts and risk-management cultures. EFSA operates within a stringent EU legal framework requiring precautionary protection of vulnerable groups, which encourages detailed uncertainty analysis and probabilistic modelling (Hoet et al., 2019). EPA’s decisions are similarly grounded in statutory mandates but often navigate different risk-benefit and economic considerations. WHO/FAO, meanwhile, must provide guidance that can be adapted to a wide diversity of national legal and social contexts, making flexibility and proportionality central design features (NRC, 2013).

Collectively, these trajectories illustrate a definitive paradigm shift from single-chemical assessments toward cumulative frameworks (

Table 1). CRA has moved from being primarily a research topic to becoming an operational regulatory tool, especially in the pesticide domain (More et al., 2019; FAO&WHO, 2019). This evolution has been driven both by advances in mixture toxicology and by growing recognition that background co-exposures can meaningfully influence health risks, particularly in sensitive populations.

Nevertheless, substantial challenges remain before a fully coherent, globally harmonized system for mixture risk assessment can be realized. Differences in data infrastructure, mechanistic understanding, and legal obligations still lead to uneven implementation across agencies and regions. EFSA’s legally embedded, data-rich framework, EPA’s domain-specific but operationalized pesticide assessments, and WHO/FAO’s resource-sensitive global guidance exemplify complementary pieces of an emerging international architecture rather than a single unified system (EFSA, 2022; U.S. EPA, 2016; FAO&WHO, 2021; UNEP, 2019).

Recent initiatives—including EFSA’s RACEMiC roadmap, EPA’s NexGen-style efforts to integrate high-throughput and computational toxicology into decision-making, and the WHO/FAO Framework for Combined Exposure—signal an ongoing scientific and institutional convergence. In parallel, coordination platforms such as OECD working parties and Codex committees are facilitating gradual alignment of terminology, data standards, and modelling practices (Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017; FAO&WHO, 2019, 2021). If sustained, this convergence could support more consistent protection of public health against cumulative exposures, while enabling regulators to better manage uncertainty and communicate mixture risks in a transparent, evidence-based manner (Hoet et al., 2019; NRC, 2013).

3.4. Total Diet Studies (TDS): Design and Best Practices

Total Diet Studies (TDS) are now widely regarded as a core public health tool for assessing chronic dietary exposure to chemicals, including both contaminants and nutrients, under realistic conditions of consumption. By focusing on foods “as eaten” and integrating them according to actual dietary patterns, TDS provide exposure estimates that are generally more representative and policy-relevant than those derived from conventional monitoring of raw commodities (W.H.O./F.A.O., 2011; World Health Organization et al., 2011). Historically, the concept emerged in the United States in the late 1950s and has since expanded globally as a standard instrument for characterizing population exposure to a wide range of chemicals in the diet (Egan, 2013; Vasco et al., 2025a, b).

Over the last decade, substantial efforts have been devoted to methodological harmonization. The joint guidance developed by EFSA, FAO, and WHO provides the conceptual foundation of modern TDS, defining key elements such as food list construction, sampling, preparation, pooling and analytical requirements (EFSA/W.H.O./F.A.O., 2011). These principles have been operationalized and refined in international initiatives such as the TDS-Exposure project, which has contributed detailed experience on food grouping, composite design and data handling across European countries (Vasco et al., 2021; BfR, 2015). National implementations further show that alignment of TDS design with specific policy questions and risk-management needs is essential for ensuring sustainable financing and long-term continuity (Moy, 2015; Vasco et al., 2025a, b).

Methodological design rests on three pillars: (i) selection of representative foods that collectively cover the vast majority of dietary intake, (ii) preparation of foods as consumed at the table, and (iii) aggregation (pooling) of similar foods into composite samples for chemical analysis (EFSA/W.H.O./F.A.O., 2011). In practice, food lists are derived from individual consumption surveys and are generally constructed to cover at least 85–90% of total energy or mass intake, depending on the diversity of national diets (W.H.O./F.A.O., 2011; Kolbaum et al., 2023). These lists are typically organized into on the order of 100–300 TDS food groups or composites, allowing a feasible balance between analytical workload and dietary representativeness (Vasco et al., 2021). Because food markets and dietary patterns evolve, periodic updating of food lists is indispensable to maintain ≥90% coverage and to ensure that new products or consumption trends (e.g., plant-based alternatives, convenience foods) are captured (Kolbaum et al., 2023; Vasco et al., 2025a, b).

Detailed national examples illustrate how these design concepts are implemented. In a French children’s TDS, 309 composite samples were prepared, each constructed as a pool of 12 subsamples of the same food collected over a one-year period, varying in brand, outlet and preparation method; this strategy captured both temporal and market-related variability while keeping the number of analytical determinations manageable (Nougadère et al., 2020). In Portugal, the inclusion of “regional seasonal” samples was used to account explicitly for seasonal and geographical variability in chemical levels or consumption patterns, demonstrating how TDS can be tailored to specific climatic and cultural contexts (Vasco et al., 2021). These examples highlight the central role of robust consumption data and careful food aggregation rules in building a food list that is both comprehensive and operational.

EFSA’s 2013 review already stressed that simple summation of exposures across chemicals neglects correlations in their occurrence, which can bias estimates of cumulative risk. To better characterize realistic co-exposure, the report highlighted the importance of multi-analyte analytical strategies and Total Diet Studies that measure several residues or congeners in the same composite samples, providing joint occurrence data that can be coupled with models such as ACROPOLIS to explore occurrence–exposure correlations (EFSA, 2013).

Sampling strategies must reflect the diversity of the food supply to ensure that composite samples are representative of actual exposure. Guidance from WHO/FAO recommends that in urban settings, foods be collected from multiple outlets and brands, typically 5–10 different retail locations per food group, while also considering different production systems where relevant (e.g., conventional vs. organic) (W.H.O./F.A.O., 2011). Combining purchases across chains, neighborhood stores and, where appropriate, direct sales from producers reduces selection bias and better represents the range of products available to consumers (Nougadère et al., 2020; Vasco et al., 2021).

Food preparation is another critical step, as it aims to mimic domestic culinary practices such as washing, peeling, trimming and cooking, thereby reflecting the actual concentration of chemicals at the point of consumption (W.H.O./F.A.O., 2011; Sirot et al., 2021). Processing can markedly increase or decrease contaminant concentrations, for example by water loss during cooking, removal with peel, or formation of processing contaminants. Consequently, TDS protocols must document in detail the applied recipes, cooking times, temperatures and preparation methods, ideally based on population-level dietary surveys and culinary information (Sirot et al., 2021; Nougadère et al., 2020). Harmonized, well-documented home-style preparation SOPs are essential for comparability across time and between countries (EFSA/W.H.O./F.A.O., 2011).

Analytically, TDS pose specific challenges because composite samples combine several foods and often encompass complex matrices in which multiple chemical classes must be quantified simultaneously. This demands highly sensitive, accurate and robust methods, frequently based on multi-element or advanced multi-analyte techniques (e.g., ICP-MS, LC-MS/MS) capable of quantifying diverse chemical classes within complex matrices (Boon et al., 2022; Vasco et al., 2025a, b). Advances in multi-residue analytical platforms continue to improve coverage and throughput but must be accompanied by rigorous method validation and ongoing quality control to ensure comparability across matrices and over time (Qiu et al., 2022). Key technical issues include managing matrix effects, ensuring storage stability of analytes in composite samples, and the limited availability of appropriate certified reference materials for complex food matrices (W.H.O./F.A.O., 2011; Qiu et al., 2022).

Handling left-censored data remains a critical source of uncertainty. Standard approaches involve substitution (e.g., lower-bound, upper-bound) or distribution-based imputation in TDS. Because a large proportion of measurements – often >50% for some analytes – may fall below LOQ, exposure estimates can be sensitive to the chosen substitution or modelling approach. Common pragmatic options include assigning values of LOQ/2 or LOQ/√2, while more advanced analyses may employ distribution-based or multiple-imputation methods (W.H.O./F.A.O., 2011). The choice should be informed by the proportion of censored results, the toxicological relevance of potential over- or underestimation, and the broader purpose of the assessment, especially when TDS outputs feed into cumulative or combined risk assessments.

TDS results are translated into exposure estimates by combining concentration data in composite samples with individual or group-level food consumption distributions. Deterministic approaches, which apply point estimates (e.g., mean or high-percentile concentrations and intakes), are straightforward and transparent, but may not capture the full variability within the population (World Health Organization et al., 2011). Probabilistic methods, by contrast, integrate the distributions of concentration and consumption, providing a more realistic characterization of inter-individual variability and uncertainty, at the cost of increased data demands and methodological complexity (W.H.O./F.A.O., 2011). Health risks are then evaluated by comparing chronic exposure estimates with health-based guidance values (HBGV), such as tolerable daily or weekly intakes (TDI, TWI) and upper intake levels (UL), or, for substances without an identified threshold, by calculating margins of exposure (MOE) or combined margins of exposure (MOET) (Boon et al., 2022). Explicit consideration of vulnerable subgroups – for example infants, young children or high consumers of specific food categories – is essential, as their exposure patterns and toxicological sensitivities can differ markedly from the general population (Nougadère et al., 2020; Sirot et al., 2021).

Overall, experience indicates that TDS provides the most reliable and cost-effective basis for assessing chronic dietary exposure at the population level, often with lower uncertainty than exposure assessments based solely on standard monitoring data (Kolbaum et al., 2024). However, the very design features that make TDS efficient also entail limitations. The pooling of foods into composites leads to a loss of information about the variability of concentrations between individual foods, brands or batches, and makes it impossible to identify highly contaminated individual products or outliers (Schendel et al., 2022; Schwerbel et al., 2022). In addition, aggregation decisions (e.g., which foods are grouped together) and the representativeness of sampling can influence risk estimates, underscoring the importance of transparent documentation and sensitivity analyses (W.H.O./F.A.O., 2011).

Several key recommendations emerge from recent applications. First, integration of TDS data with national food monitoring programs is strongly advised to exploit the complementary strengths of each source: TDS offers realistic chronic exposure estimates, while monitoring data preserve product-level variability and support enforcement and source attribution (Kolbaum et al., 2024; Schendel et al., 2022; Schwerbel et al., 2022). Second, harmonization of reporting formats is crucial to enable cross-country comparison and pooled analyses. This includes agreement on minimal reporting elements such as FoodEx2-based coding and pooling schemes, age- and sex-stratified exposure estimates, and harmonized descriptive statistics for concentrations and intakes (Vasco et al., 2025a, b; World Health Organization et al., 2011). Third, food lists and composite structures should be periodically revised to maintain high coverage of current diets and to incorporate emerging food categories, thereby ensuring continued relevance of TDS outputs for risk assessment and policy (Kolbaum et al., 2023; Vasco et al., 2025a, b).

Looking ahead, the strategic value of TDS is likely to increase as new classes of dietary contaminants emerge (e.g., nanomaterials, microplastics) and as integration with human biomonitoring (HBM) and advanced exposure modelling becomes more routine (W.H.O./F.A.O., 2011; Vasco et al., 2025a, b). Linking TDS data with HBM can help validate exposure models, refine toxicokinetic assumptions and improve the interpretation of biomarker levels at the population level. At the same time, advances in data science and artificial intelligence – for example, predictive models of contamination patterns across food chains or tools for optimizing sampling designs – offer opportunities to enhance efficiency and tailor TDS to evolving policy priorities (Qiu et al., 2022; Vasco et al., 2025a, b). Realizing this potential will require sustained multi-stakeholder collaboration, robust data infrastructures and clear alignment of TDS programs with national and international risk-management agendas (Moy, 2015; BfR, 2015).

3.5. Human Biomonitoring (HBM) of Dietary Origin

Monitoring chemical mixtures in foods increasingly requires moving beyond estimates of external exposure to directly measuring internal human doses. Human biomonitoring (HBM) provides this connection by quantifying parent compounds, metabolites or adducts in biological matrices, thereby capturing real-life exposure from all routes and sources, including diet, and the modifying role of toxicokinetic (Tadić et al., 2025; Sabbioni et al., 2022; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe [WHO], 2023). Coordinated initiatives such as HBM4EU, EFSA’s harmonized frameworks and WHO guidance have consolidated HBM as a crucial complement to occurrence-based exposure assessments, including Total Diet Studies (TDS), particularly when HBM data are interpreted alongside food-consumption information and mixture-risk metrics such as the Hazard Index (HI) or the Margin of Exposure for mixtures (MOET) (Apel et al., 2020; Santonen et al., 2023; Dean et al., 2025; Zare Jeddi et al., 2022). In this integrated perspective, HBM translates food-chemical occurrence into evidence-based indicators of internal exposure and potential health risk, reducing uncertainty in mixture risk assessments.

Applied to diet, HBM is embedded in the broader concept of the dietary exposome, i.e., the ensemble of exogenous and endogenous chemicals that enter the body through food and interact with biological systems over the life course (Calatayud Arroyo et al., 2021; Landberg et al., 2024; Kunde et al., 2025; Ortiz et al., 2022; Gruszecka-Kosowska et al., 2022). Serum, urine, breast milk and other matrices capture both persistent and short-lived compounds and thus complement TDS, which estimate external intakes from food and drinking water (Mattisson et al., 2018; Sabbioni et al., 2022). The European exposure-science strategy 2020–2030 explicitly frames HBM as part of a 21st-century toolbox that integrates analytical chemistry, omics, and exposure modelling within an exposomic paradigm (Zare Jeddi et al., 2022; Tadić et al., 2025). Nutritional metabolomics and untargeted exposomic workflows further extend this scope by enabling simultaneous measurement of food-derived metabolites, environmental contaminants and endogenous response markers, revealing dietary signatures and co-exposure patterns that can be linked back to foods or dietary patterns (Kortesniemi et al., 2023; Kunde et al., 2025; Rodríguez-Carrillo et al., 2023). WHO and regional European guidance emphasize that diet-focused HBM must rely on standardized sampling, robust ethical protocols and harmonized QA/QC to ensure cross-population comparability and policy relevance (World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, 2023; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe [WHO], 2023).

The selection of effective dietary biomarkers is central to the interpretability of HBM data. Beyond analytical sensitivity and specificity, biomarkers must be biologically and epidemiologically meaningful, i.e., they should reflect the relevant exposure window, allow linkage to dietary sources and support dose–response assessment (Landberg et al., 2024; Owolabi et al., 2024; Turner & Snyder, 2021). Time window and representativeness are key: short-lived chemicals such as phthalates or bisphenols, with urinary half-lives of hours, require sampling strategies that capture within-person variability, including repeated or first-morning urine samples, or the use of metabolites with longer integration windows (Carwile et al., n. d.; Govarts et al., 2023; Gerofke et al., 2023; Sabbioni et al., 2022). In contrast, persistent pollutants such as many PFAS and some metals accumulate in long-lived matrices (e.g., blood, hair) and provide stable indicators of long-term exposure (BarbosaJr et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2020; Abraham et al., 2024; EFSA, 2020). Reproducibility metrics illustrate these issues: alkylresorcinols as biomarkers of whole-grain intake show intra-class correlation coefficients around 0.38–0.74 over 2–36 months, which is acceptable but still imposes constraints on statistical power and on the interpretation of diet–disease associations (Landberg et al., 2024). Across EFSA and HBM4EU, converging guidance highlights four core criteria for dietary biomarkers—sensitivity at low environmental levels, specificity for relevant exposure routes (ideally diet), temporal stability within the intended window, and inter-individual reproducibility—along with explicit characterization of uncertainty and comparability to reference populations when used in mixture evaluations (EFSA Scientific Committee et al., 2021; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe [WHO], 2023; Kortesniemi et al., 2023).

Case studies for specific chemical families exemplify both the strengths and the limitations of dietary HBM. For per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), HBM data demonstrate high persistence and a strong linkage to diet in many populations. Serum half-lives vary widely, ranging from weeks (e.g., PFBS) to years (e.g., PFOS, PFHxS), thus providing long integration windows and relatively high dietary specificity, especially where drinking water and certain foods (fish, eggs, offal) are dominant contributors (EFSA, 2020; Xu et al., 2020; Sabbioni et al., 2022; Santonen et al., 2023; Abraham et al., 2024). Under HBM4EU, adolescent reference values (RVs) were derived for 12 PFAS; European HBM data indicated that around 14.3% of teenagers exceeded a serum sum of 6.9 μg/L, a level corresponding to EFSA’s TWI of 4.4 ng/kg bw per week, underscoring the public health relevance of dietary exposure (Uhl et al., 2023; EFSA, 2020). Syntheses of PFAS exposure confirm that diet is often the main pathway in the general population, particularly where drinking water is controlled, and that serum levels can be quantitatively related to long-term intakes using physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models (Mattisson et al., 2018; Schoeters et al., 2025; Dean et al., 2025; U.S. EPA, 2025a, b).

To explicitly account for absorption, distribution, and body burden, Internal Hazard Indices (HI

int) can be derived using toxicokinetically corrected metrics. This involves calculating Internal Hazard Quotients (IHQ

i) defined as:

Alternatively, the Internal Dose Toxic Unit (IDTU) approach sums the ratios of internal concentrations (C

i) normalized by Critical Body Residues (CBR

i) or bioaccumulation factors (BAF

i):

These internal metrics refine the assessment by integrating the net result of bioavailability and metabolic interactions, offering a more proximal indicator of tissue-level risk than external dietary estimates.

For phthalates and bisphenols, short biological half-lives create challenges for interpretability. Single spot urine samples may poorly represent habitual exposure, especially when product use and diet vary day to day (Carwile et al., n.d.; Govarts et al., 2023; Gerofke et al., 2023). Nonetheless, HBM4EU results show that HBM guidance values (HBM-GVs) for several phthalates and substitutes are exceeded in specific subgroups, particularly children and adolescents, and that mixture-based assessments can reveal anti-androgenic risks missed by single-substance approaches—around 17% of children/adolescents may experience anti-androgenic mixture risks from phthalates at current exposure levels (Gerofke et al., 2024; Govarts et al., 2023). EFSA’s recent review of bisphenol A (BPA) illustrates how urinary biomarkers can be used to relate internal exposure to health-based guidance values: a very low TDI of 0.2 ng/kg bw per day, based on immune (Th17) effects, implies that even modest urinary concentrations can correspond to exceedances of health-based limits for some consumers (EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials et al., 2023; EFSA, 2021). Here, diet (e.g., canned foods, food contact materials) and non-dietary sources (e.g., thermal paper, consumer products) both contribute, underscoring the need for careful attribution of exposure pathways in mixture assessments (Govarts et al., 2023; Gerofke et al., 2023).

Mycotoxins provide an example of high dietary specificity combined with variable exposure windows. Urinary biomarkers of ochratoxin A, deoxynivalenol and fumonisins are increasingly used to estimate chronic intake and to identify sub-populations at risk, particularly among cereal consumers (Turner & Snyder, 2021; Habschied et al., 2021; Peris-Camarasa et al., 2025; Arce-López et al., 2024). Biomarkers based on protein adducts, such as aflatoxin–albumin or hemoglobin adducts, integrate exposure over weeks to months and are thus suited to chronic-risk characterization, but regional heterogeneity, seasonality and co-occurrence of multiple mycotoxins complicate cross-country comparisons and mixture evaluations (Sabbioni et al., 2022; Arce-López et al., 2024). Overall, these chemical-family examples illustrate how dietary HBM can address both longstanding and emerging contaminants, and how family-specific toxicokinetic shape the choice of biomarker, sampling strategy and mixture-risk modelling approach (Apel et al., 2020; Dean et al., 2025).

Integrating HBM with consumption data, TDS and PBPK modelling is pivotal for transforming biomarker concentrations into quantitative intake estimates suitable for mixture-risk assessment. In PFAS case studies, PBPK models show that diet is often the dominant contributor to internal exposure, but that other sources (e.g., drinking water, consumer products) can be important in specific subgroups; modelled internal exposures typically align with, but may be somewhat lower than, measured serum concentrations, reflecting uncertainties in parameters and unaccounted sources (Mattisson et al., 2018; Dean et al., 2025; Abraham et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2020). For PFOA, a study in women showed that personal-care products could exceed dietary contributions in some individuals, highlighting source-specific heterogeneity even when diet is the main pathway at population level (Husøy et al., 2023). At the program level, comprehensive national strategies combining market monitoring, TDS and HBM have been proposed and implemented to characterize exposure distributions and to benchmark them against health-based guidance values in a consistent way (Li et al., 2025; Santonen et al., 2023). EFSA’s methodology explicitly recommends the use of PBPK modelling and reverse dosimetry to convert biomarker levels into equivalent daily intakes that can be compared with TDIs, TWIs or BMDLs and integrated into HI or MOET calculations (EFSA, 2020; Dean et al., 2025; Zare Jeddi et al., 2022).

Robust reporting and harmonization are essential to ensure that dietary HBM data can be pooled, compared to and used in regulatory decision-making for chemical mixtures. The HBM4EU project highlighted harmonized QA/QC schemes, inter-laboratory comparability, and the availability of suitable reference materials as prerequisites for reliable data (Apel et al., 2020; Heinälä et al., 2017; Vorkamp et al., 2023). Building on this, the “Minimum Information Requirements” (MIR) proposed by Zare Jeddi et al. specify key elements that should be reported from study design through publication—population descriptors, sampling windows, analytical methods and performance, and left-censor handling—to maximize data quality, accessibility and interpretability (Zare Jeddi et al., 2022; Zare Jeddi et al., 2025; Gilles et al., 2021). WHO guidance complements MIR with explicit recommendations on ethics, participant feedback (including communication of individual results in cases of concern) and laboratory QA/QC (World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, 2023; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe [WHO], 2023). EFSA and HBM4EU also point to persistent deficits in contextual metadata—such as mixture co-exposures, diet and lifestyle confounders, and socio-economic variables—as major obstacles to mixture-aware analyses and to the identification of vulnerable groups (EFSA Scientific Committee et al., 2021; EFSA, 2021; Santonen et al., 2023; Govarts et al., 2023; Gerofke et al., 2024; Landberg et al., 2024).

Despite rapid progress, important knowledge gaps remain. These include the scarcity of longitudinal datasets across life stages, limited integration of non-persistent compounds in routine monitoring, under-representation of vulnerable groups such as children and pregnant women, and the lack of validated biomarkers for emerging hazards (e.g., nanomaterials, microplastics) and for mixture-aware exposure or effect indicators (Heinälä et al., 2017; Zare Jeddi et al., 2022; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, 2023; Rodríguez-Carrillo et al., 2023; Owolabi et al., 2024). Nonetheless, dietary HBM is clearly shifting from exploratory pilot projects towards policy-focused surveillance, providing direct human evidence for the evaluation of mixture-risk methods such as HI and MOET and for the assessment of risk-management effectiveness (Apel et al., 2020; Santonen et al., 2023; Vorkamp et al., 2023; Dean et al., 2025). Coordinated implementation of MIR, sustained EFSA–WHO collaboration and further development and validation of PBPK models for diverse chemical families will be crucial to fully exploit the potential of HBM in integrated exposure assessments (Zare Jeddi et al., 2025; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe [WHO], 2023). The policy relevance of this approach is already evident: HBM4EU results are directly supporting implementation of the EU Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability and the Zero Pollution Action Plan, demonstrating how HBM data can be used to track progress towards exposure reduction goals and to evaluate the effectiveness of regulatory actions targeting dietary mixtures of xenobiotics (Lobo Vicente et al., 2023).

3.6. Best Practices and Communication

Across these applications, recurrent errors can undermine the robustness of mixture assessments. These include unjustified extrapolation of synergy beyond narrowly defined experimental conditions, misclassification of MOA similarity leading to inappropriate selection of CA or IA, inconsistent or poorly documented grouping criteria, and neglect of covariance in co-exposure patterns, even though source, use and physiological correlations between components are frequent (Sarigiannis & Hansen, 2012; Vejdovszky et al., 2019; Boberg et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2024; Kienzler et al., 2016, 2017). A particularly pervasive issue is the categorical interpretation of HI < 1 or MOET above default thresholds as evidence that a mixture is “safe”, without adequately conveying residual uncertainty, susceptible subpopulations or the conditional nature of model assumptions (NRC, 2013; Massey et al., 2022; Heinemeyer et al., 2022). In communication with risk managers and the public, failing to explain these nuances can erode trust and obscure the precautionary or conservative elements embedded in mixture assessments (Hart et al., 2019; Spiegelhalter, 2017; Heinemeyer et al., 2022).