1. Introduction

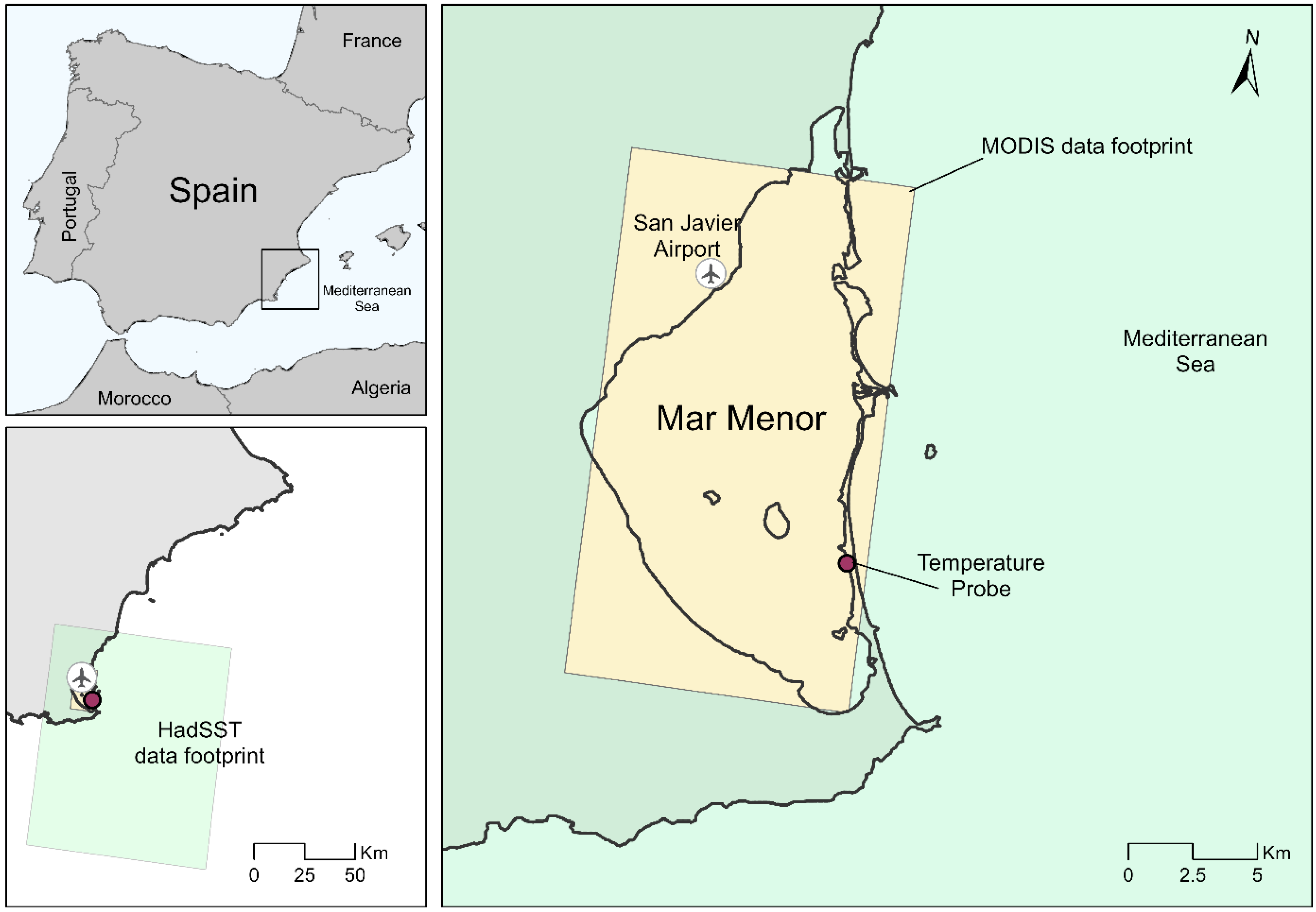

The Mar Menor, located in the southeast of Spain, is the second largest lagoon in the Mediterranean Sea with a surface area of about 136 km

2. It is restricted from the open sea by La Manga, a 22-km long sandy barrier crossed by three tidal inlets (

Figure 1). As a result of an annual evaporation rate that is 3 to 4 times greater than rainfall, it is hypersaline (42-47 ppt) in parts [

1,

2] which gives the lagoon a unique environmental character such that it constitutes a refuge for some endemic species. Moreover, it contains 856 ha of fringing salt marsh that is used as a stop-over by migrating shore birds. As a result it was designated a Ramsar wetland in 1994. It is shallow (a mean depth of 4.5 m) and has been highly impacted by “

massive urban growth” [

3]. Some sites are contaminated with heavy metals from old mining discharges [

4,

5] manifested as bio-accumulation (of Zn, Cd, and Pb) in bivalves and the take up of toxins by seagrass plants such as

Cymodocea nodosa. The solubility and mobility of such toxic metals increases with water temperature [

6]. This is particularly true in fine-grained sediment such as those of the Mar Menor. The increase in eutrophication and anoxia due to “

unsuitable agricultural methods”, that introduce excess nitrates and phosphates into the system, has had significant impacts on the biosphere of the lagoon [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Groundwater discharges and flood events introduce nutrients loads from the catchment area. These events can produce algal blooms that significantly reduce the water oxygen content and can cause mass mortalities as observed in recent years (2016, 2019 and 2021). Water temperature has been shown to be a major factor leading to enhanced eutrophication in aquatic settings, while in combination with the two nutrients has far reaching effects on biological community dynamics [

11]. Bio-accumulation of toxins are also enhanced by the long residence time of waters (average of 0.79 years) in the [

12,

13].

A surface energy budget of a coastal lagoon (Nueva lagoon) in S.E. Spain was undertaken by [

14], referred to hereafter as RR06. The formulation and structure of this budget has been followed in the Mar Menor by [

15], referred to hereafter as MA11, who asserted that there was limited information on the hydrodynamics of the system. More recently, 3-D numerical modelling of the hydrodynamics of the Mar Menor has significantly enhanced the understanding of structure and dynamics of the lagoon under both tidal and wind-forced conditions [

13]. Whilst temperature and salinity were imposed in a 3D hydrodynamic model (SHYFEM) open boundary [

16], sources and sinks of heat within the system were not included. This paper attempts to provide a simple heat box model of the Mar Menor that includes all major local sources and sinks of heat following the structure defined in the previously quoted papers. The exchange of heat across the benthic boundary layer is rarely included in models due to a lack of information on the thermal properties of the bottom sediments (a notable exception is RR06). Part of this work is to measure the temperature gradient in the topmost 0.45 m of the seabed in order to determine the heat exchange (in W/m

2) of the seabed with the waters of the Mar Menor which may provide useful input to advanced hydrodynamic models such as SHYFEM.

The Mar Menor is dominated by fine grained sediments. The distribution, character and dynamics of such sediments can be greatly impacted by changes in water temperature as can benthic exchanges with the water column that impacts turbidity and water clarity [

10,

17,

18]. Seasonal fluctuations in sea surface temperature (SST) in the Mar Menor are of the order 21

oC (10 – 31

oC) largely due to the shallow water depths [

9]. These fluctuations are higher than that in the open sea. Seasonal effects of SST on biological productivity of coastal lagoons can be large [

19] as is the impact of dredging of the channels connecting Mar Menor with the open sea [

13]. Furthermore, the SST of coastal lagoons has been increasing at a much faster rate that the global average [

20,

21,

22]. SST in Venice lagoon, for example, has been increasing at a rate of up to 1.75

oC/decade since 2008 [

21]. It is not unreasonable to expect that the temperature trend in Mar Menor will be greater than is the case for Venice lagoon as the flushing of warm water with the open sea results in a residence time of up to 1 year [

13]. An objective of the work herein is to understand the SST trends on the Mar Menor and the factors that influence these as a basis for enhanced management purposes for sustainability, as recommended by [

23].

2. Materials and Methods

The factors influencing the hydrology and hydrodynamics of the Mar Menor have been defined by [

2]; their definition of inputs and losses to the system has been used as a guide herein. In particular, the gross annual budgets of surface runoff, new water exchange at the inlets, ground water discharge, and evaporation are taken from this source. Other sources of information are defined below.

2.1. Thermal Probes

Hourly measurements of the temperature were made by four self-logging thermistors (Signatrol® SL52T) installed in a thermal probe that was driven into the seabed in 0.3 m of water at low tide within the shallow subtidal region of the barrier Island at Playa de Galan (Lat: 37.685

oN, Lon: 0.737

oW, see

Figure 1). The thermistors were factory calibrated to an accuracy of ± 0.1

oC. Each thermistor was capable of logging temperature data hourly for about 5 months (3600 data points). Thermistors were located at a height of 0.15 m above the seabed, and at depths (h) of 0.15, 0.30 and 0.45 m below the seabed. Each thermistor was pre-programmed with date/time, and the data downloaded to ASCII-format files using company software. The mean heat flux (q

z) was estimated from the temperature gradients using Fourier’s law:

where k is thermal conductivity of saturated shelly sand (assumed as 1.5 W/m.K after [

24]). Thermal diffusivity (α) is related to thermal conductivity as follows:

where ρ is the saturated bed sediment bulk density of the local well-sorted fine sand (d

50 = 0.23 mm) and is assumed as 1700 kg/m

3, and C

p is the specific heat capacity (assumed to be 2.4 MJ/m

3.K). Estimates of the temperature gradients (both during the day and night) are determined by defining the peaks and troughs of each temperature time series (that fluctuate daily). First order polynomial best fits to the peak and trough temperatures were made to define daytime and night-time values of

. It is assumed that the peaks and troughs in temperature are coincident in time and that the properties of the bed are constant with depth. Thermal diffusivity may also be estimated from:

where Δz = 0.45 m, and the lag is the time difference between upper and lower peak (in seconds).

2.2. The Mean Monthly Time Series Data

Mean monthly SST were downloaded from global sea surface temperature data sets (HadSST1.1) compiled by the Met Office, Hadley Centre (

https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/; [

25]). A sub-set of the western Mediterranean Sea (lat: 37-38

oN; lon: 0-1

o W, see

Figure 1) was extracted using purpose-written code. SST for the Mar Menor were downloaded from MODIS Aqua (11 microns, night only, 4 km resolution) using the Giovanni tool (

https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/resources/giovanni/) available from July, 2002 to the present (lat: 0.854 – 0.729 W; lon: 37.633 – 37.819 N, see

Figure 1). [

26] have shown that MODIS SST data is highly correlated with measurements in the Mediterranean Sea. SST data in Mar Menor prior to 2002 were backfilled to September, 1981 using the OISST blended analysis from NOAA (

https://psl.noaa.gov/mddb2/makePlot.html?variableID=156646; lat: 37.25 – 37.5 N; lon: 0 – 1 W). El Niño Southern Oscillation SST anomaly based on HadISST data (ENSO3.4,

https://psl.noaa.gov/gcos_wgsp/Timeseries/Nin34/) (in units of degrees Celcius) were downloaded from January, 1870 to May, 2024.

Gross domestic product (GDP) for Spain was digitized from data provided by World Bank Group (

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=ES). Sunspot activity was provided by the World Data Center (WDC) Sunspot Index and Long-term Solar Observatory (SILSO), at the Royal Observatory of Belgium, Brussels (DOI: doi.org/10.24414/qnza-ac80).

2.3. Statistical Analyses

The HadISST1.1 global monthly time series was analysed using purpose written Matlab® codes. Data from January, 1900 to December, 2024 were examined in detail for this study. A 13-point moving average was applied to all timeseries to remove seasonality. The results were subtracted from the raw data to derive the seasonal components. A 13-term Henderson filter was applied to the raw data as a means of comparison of the filtered time series [

27]. The long term trends of the de-seasoned data were derived by a least square linear best fit regression. A time-series analysis of each calendar month was also undertaken following [

28] and a least-square trend analysis was applied. The level of significance of the trends (p-values) were examined in Sigmaplot® and associated level of significance were reported. SST anomalies (SST-a) as defined by [

29] were used in statistical analyses which were defined as the de-seasoned value minus the long-term mean. The same procedure was applied to air temperature anomaly (AT-a) and CO

2 anomaly (CO2-a) to provide de-seasoned time-series that were comparable to the oceanic indices listed above.

Mean monthly data (SST-a “the dependent variable”, NAO, ENSO, IOD, AMO, PDO, CO2-a, sunspot number, GDP, AT-a, wind speed, and incoming solar radiation “the independent variables”) for two time periods (pre and post 1980) have been analysed by cross-correlation (to examine phase relationships), by Spearman rank correlation (non-parametric analysis less influenced by outliers), and by principal component analyses in order to understand which factors appear dominant to explain the variances of air temperature and SST. Cross-correlation of variables with SST-a and AT-a was evaluated in Matlab®, other statistical tests were undertaken in Sigmaplot®. [

23] show that satellite derived SST can be 0.2

o K different from waters below, and may also be influenced by dust in the atmosphere. These effects have not been considered in this study.

2.4. A Box Model for the Mar Menor

A box model of energy inputs and outputs to the Mar Menor seawater has been constructed following the work of [

15] in order to assess the short term (months to years) drivers of SST. The purpose of the box model is to quantify (and balance) the sources and sinks of energy that result in the observed SST and to compare these results (at monthly time steps over 22 years, 2002 to 2024) to the daily time steps (over 3 years) in [

15]. A second purpose was to see if there were any fundamental changes in the heat balance that could be detected over the 22-year simulated period. Six main sources/sinks are recognised herein following [

30]: (1) sensible heat exchanges between air, ground, and seawater, (2) latent heat exchanges with the atmosphere due to evaporation and condensation, (3) incoming short and long wave solar radiation (modified by cloud cover), (4) outgoing long-wave radiation (also modified by cloud cover), (5) seawater/ground exchanges in sensible heat, and (6) tidal mixing/advection across the inlets. The sources/sinks of 1 to 4 are described in full by [

31,

32] together with relevant constants and coefficients. Tidal mixing across the inlets is described by [

13].

The sensible heat flux (Q

air) from air to seawater is dependent on the mean temperature gradient between air and water and the wind speed over water. It is defined as follows:

where ρ

air is air density (1.22 kg/m

3), Cp

air is the specific heat of air (1006 J/kg.C), C

h is the bulk transfer coefficient (1.2 * 10

-3), U

10 is the wind speed (m/s) at a height of 10 m, assumed in the first instance to be better represented by the friction velocity (U

*) following the method of [

33], x is an empirical coefficient (wind reduction factor) used to equate predicted (1.29 m/annum) and measured evaporation rates (1.35 m/annum, [

2,

15], and T

sea and T

air are the mean monthly seawater and air temperatures respectively.

SST in Mar Menor is also modified by the latent heat exchange due to evaporation (Q

lt) which, according to [

32] requires information on the saturation specific humidity (e

sat) and saturation air vapour pressure (q

sat):

where l

v is the latent heat of vaporization (2.43 x 10

6 J/kg at 20

oC and 35 psu), C

e is the evaporation coefficient (1.5 * 10

-3), and where

where P is atmospheric pressure (assumed as 1013 millibars or hectopascals) and:

The effect of salinity on evaporation rate has been ignored.

where α

s is the surface albedo of semi-arid terrains such as those surrounding the Mar Menor (≈ 0.25), 0.7n

c is impact of the cloud cover fraction [

31]. For present purposes, a long term monthly average of cloud cover has been used ((

https://gmao.gsfc.nasa.gov/reanalysis/merra-2/).

Outgoing longwave radiation (Q

out) is derived using the modified Stefan-Bolzmann relationship:

where ϵ is the emissivity of seawater (0.98), q

sat is the vapor pressure of water (assumed constant at 23 mbar) and σ is the Stefan-Bolzmann constant (5.67 * 10

-8 W/m

2/K

4) where (K = T

sea + 273.5

oC) is the absolute water temperature. The modification to EQ 8 has been proposed by [

34]. This formulation assumes cloud cover influence as defined above, as recommended by [

23].

Input of heat from rivers system has been evaluated based upon annual discharge data from [

2] and river water temperature is equated with ground temperature derived from the MERRA-2 project (

https://gmao.gsfc.nasa.gov/reanalysis/merra-2/). This input is defined as:

where V is the mean monthly volume discharge of fresh water, Tgr is the mean monthly ground temperature surrounding the Mar Menor (assumed as a constant of 18oC within the seabed of the Mar Menor), Tr is the mean monthly river water temperature (equated with air temperature), the time step, Dt = 2630016 seconds (i.e. one month), Cpwater is the specific heat of water (3993 J/kg.oC) and Agr is the assumed area of the Mar Menor (1.36 * 108 m2).

The energy balance is then calculated following [

31], RR06 and MA11 as:

The temperature change in SST (dT) is evaluated at monthly increments of time (per m

2); the affected water mass (M

water) is estimated using a mixing depth (h) of 4.5 m [

3] and is defined per unit area as:

where unit water mass is:

The evaporation rate (E

v, m/month) is predicted as a function of the wind speed and relative humidity:

Annual evaporation is estimated by summing the monthly evaporation rates. U10 (wind speed at a height of 10 m) has been optimized in order to equate EQ 13 to the annual evaporation in the Mar Menor. This results in a wind reduction factor (x) of 1.0. This factor was initially used in EQs 4, 5 and 13. Finally, the Bowen ratio (BR, the ratio of sensible to latent heat exchanges with the sea surface) was also estimated at monthly intervals.

3. Results

A stepwise approach to the SST in the Mar Menor was used to examine the heat budget post 1980. Firstly, the temperature profile measurements in the seabed are presented (in order to define a seawater/seabed heat exchange), followed by the Spearman statistical analyses, then the cross-correlation of factors defined above, and finally the balancing of the heat budget within a box model. The results are compared to the output from RR06 and MA11.

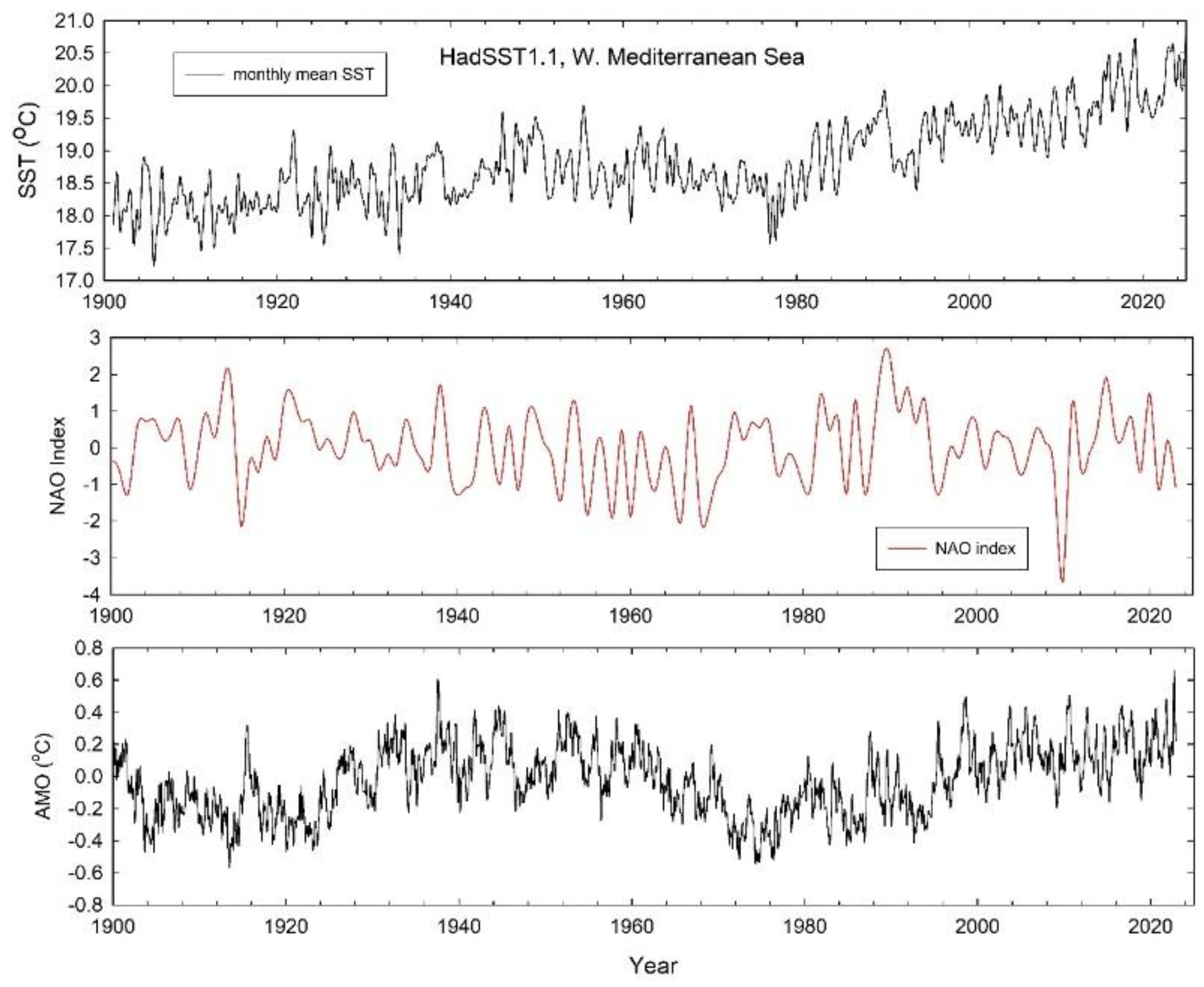

3.1. Sea Surface Temperature

The Western Mediterranean is the open boundary for the Mar Menor and hence is an important influence on the heat budget of the lagoon. Monthly mean SST data from the W. Mediterranean Sea, extracted from the HadSST1.1 global data set, are presented from 1900 to 2024 (inclusive) in

Figure 2A. Note that there is no long clear trend in SST prior to circa 1980. Post 1980 there appears to be a systematic warming. It also appears that long-term variations in SST follow trends in the AMO (

Figure 2C), while shorter term peaks and troughs follow those in the NAO (

Figure 2B) as suggested by [

26].

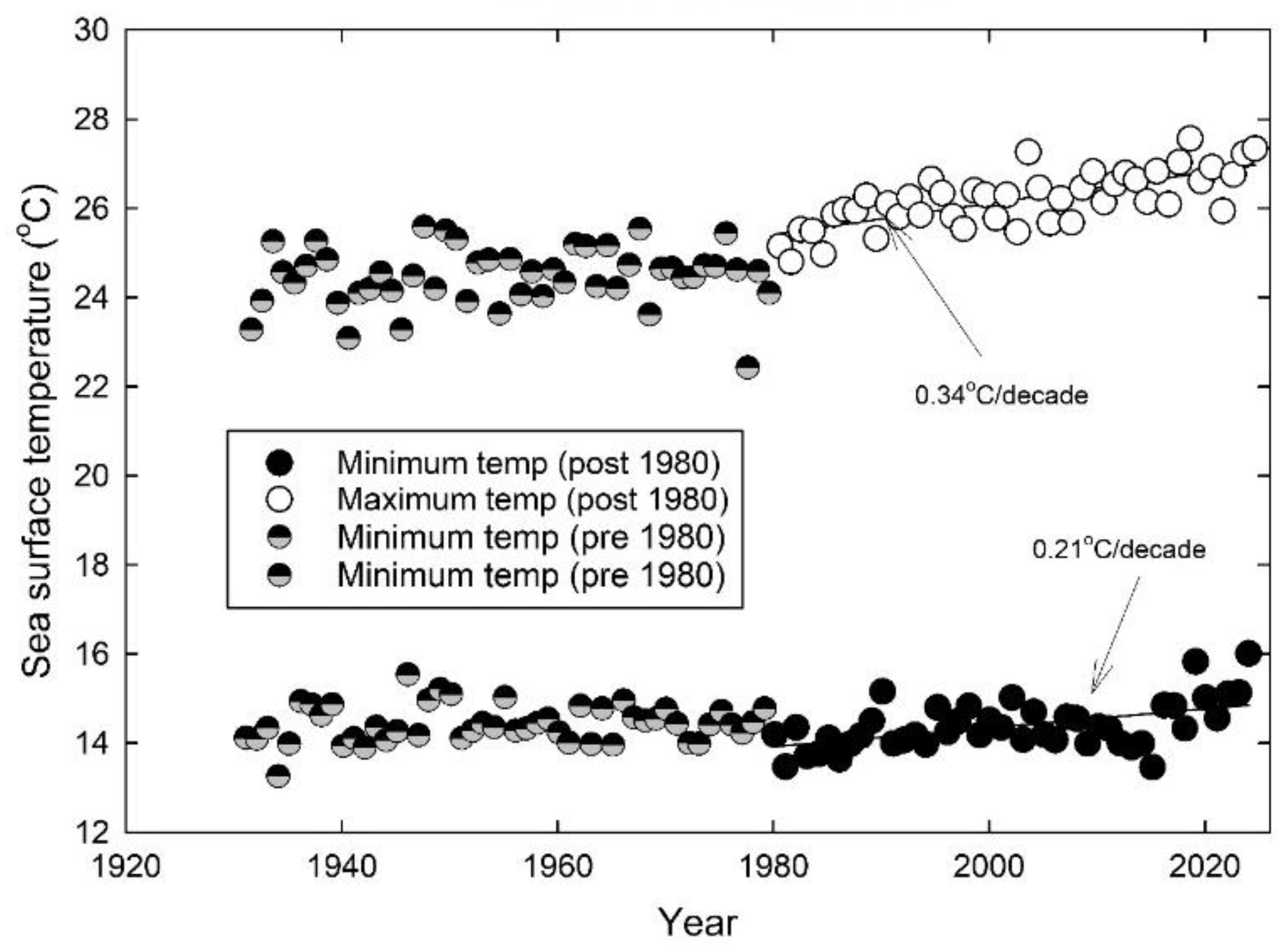

The annual maxima and minima in SST of the Western Mediterranean (

Figure 3) clearly show no trend in either extreme prior to 1980. Furthermore, the extremes appear remarkably consistent in time. Summer warming since 1980 shows a significant trend of 0.34

oC/decade as well as reduced scatter; winter minima also show significant warming but at a lower rate of 0.21

oC/decade. [

35,

36,

37] have shown similar warming in their data analysis which covers the period since 1979. [

26] showed a stable increase in SST of 0.55

oC/decade for the period 2005 – 2019.

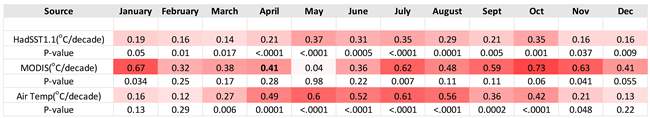

The SST anomalies post 1980 for the Western Mediterranean, the Mar Menor (MODIS), and the OISST (NOAA) together with the air temperature anomaly (AT-a) for the Mar Menor are presented in

Figure 4. Note that the peaks and troughs are generally consistent between records though the Mar Menor is generally cooler that either local air temperature or SST further offshore. Clearly evident in all data sets is the relative cooling presumed due to the volcanic explosions of Mount Pinatubo (1991 – 1994) and Hunga Tonga in January, 2022 [

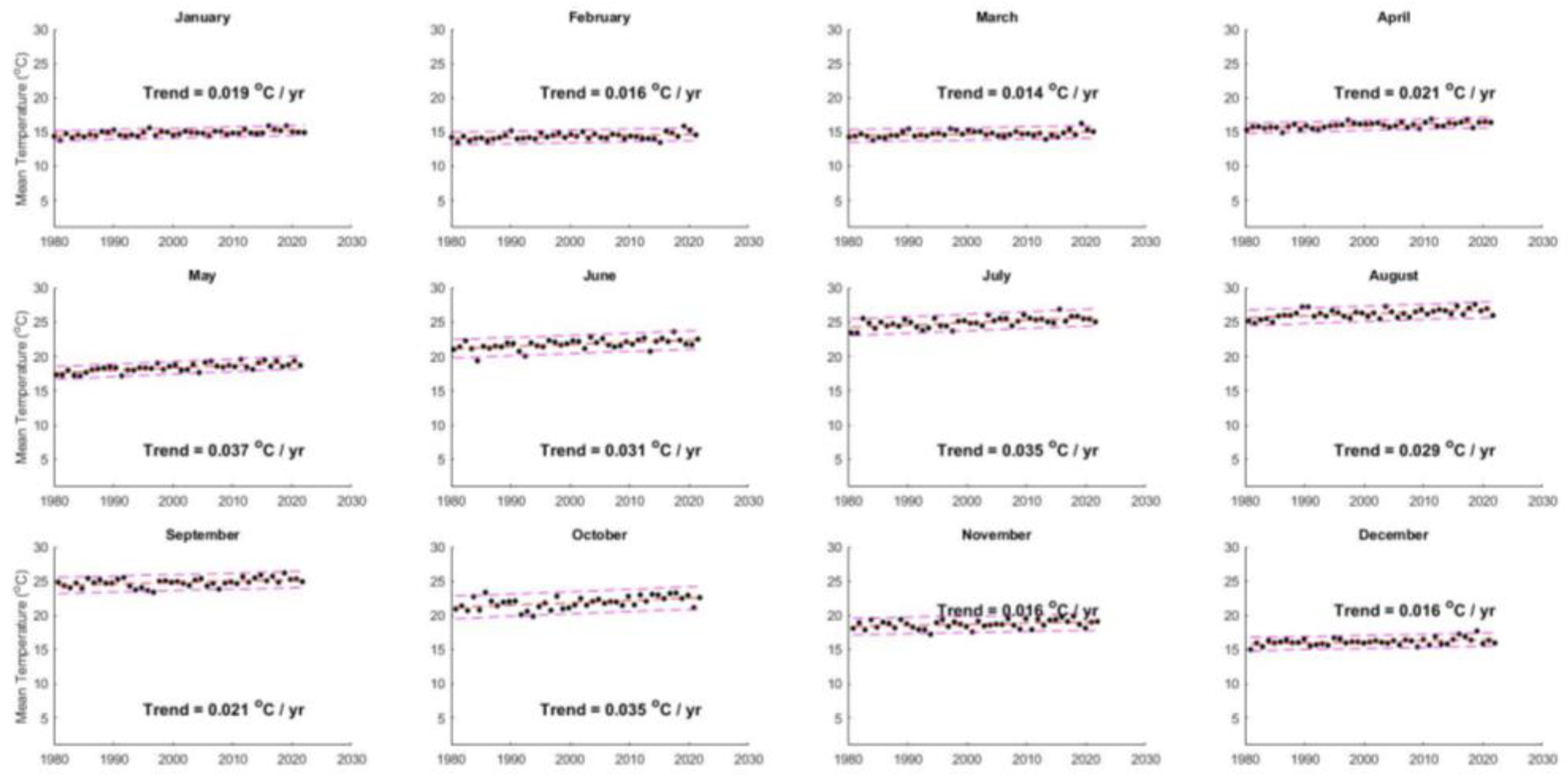

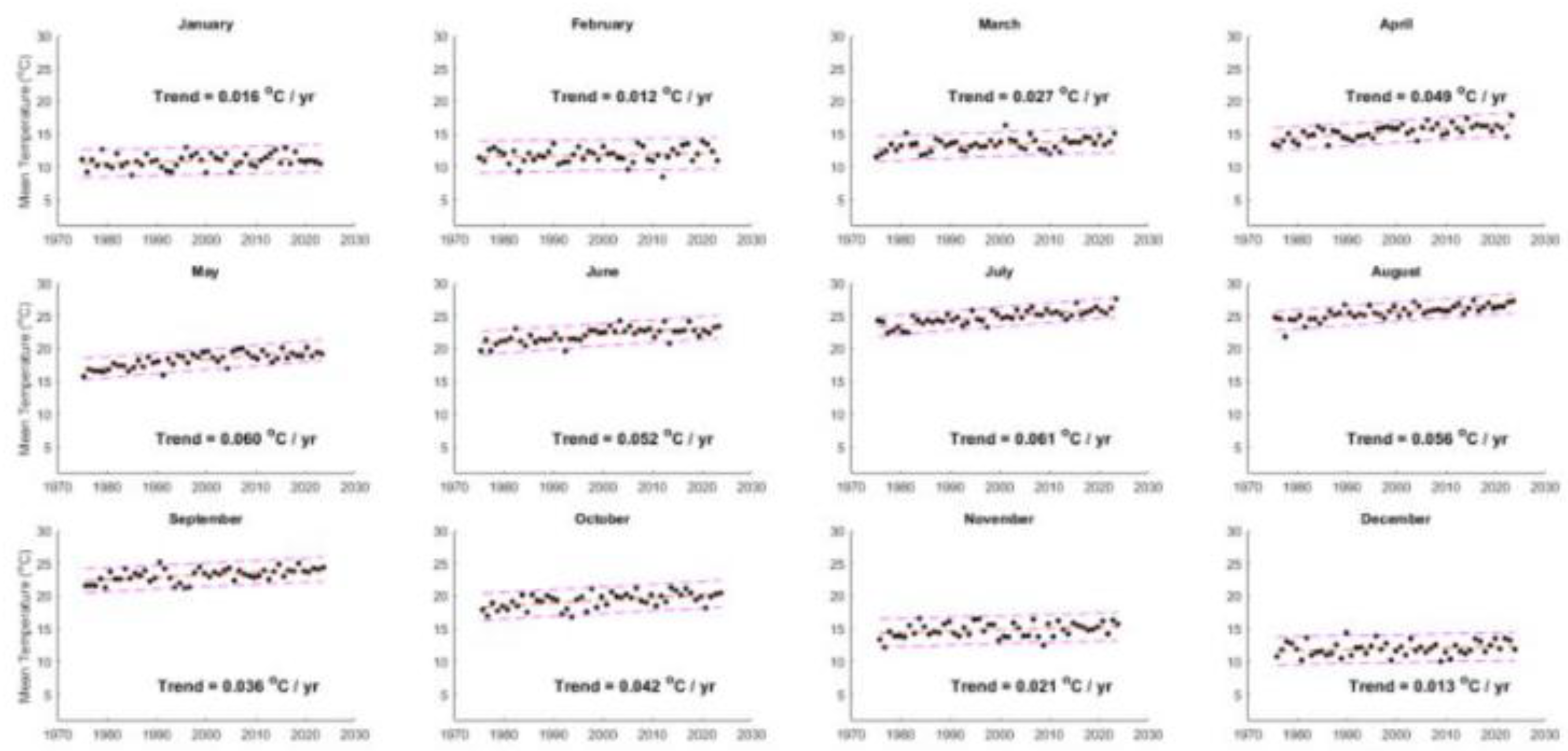

38]. The least-squares best-fit trends in SST are presented for each month of the year in

Figure 5. These trends are also listed in

Table 1. Notice that all months of the year show significant warming with warming greatest in the summer and least in the winter.

3.2. Seawater to Seabed Heat Exchanges in the Mar Menor

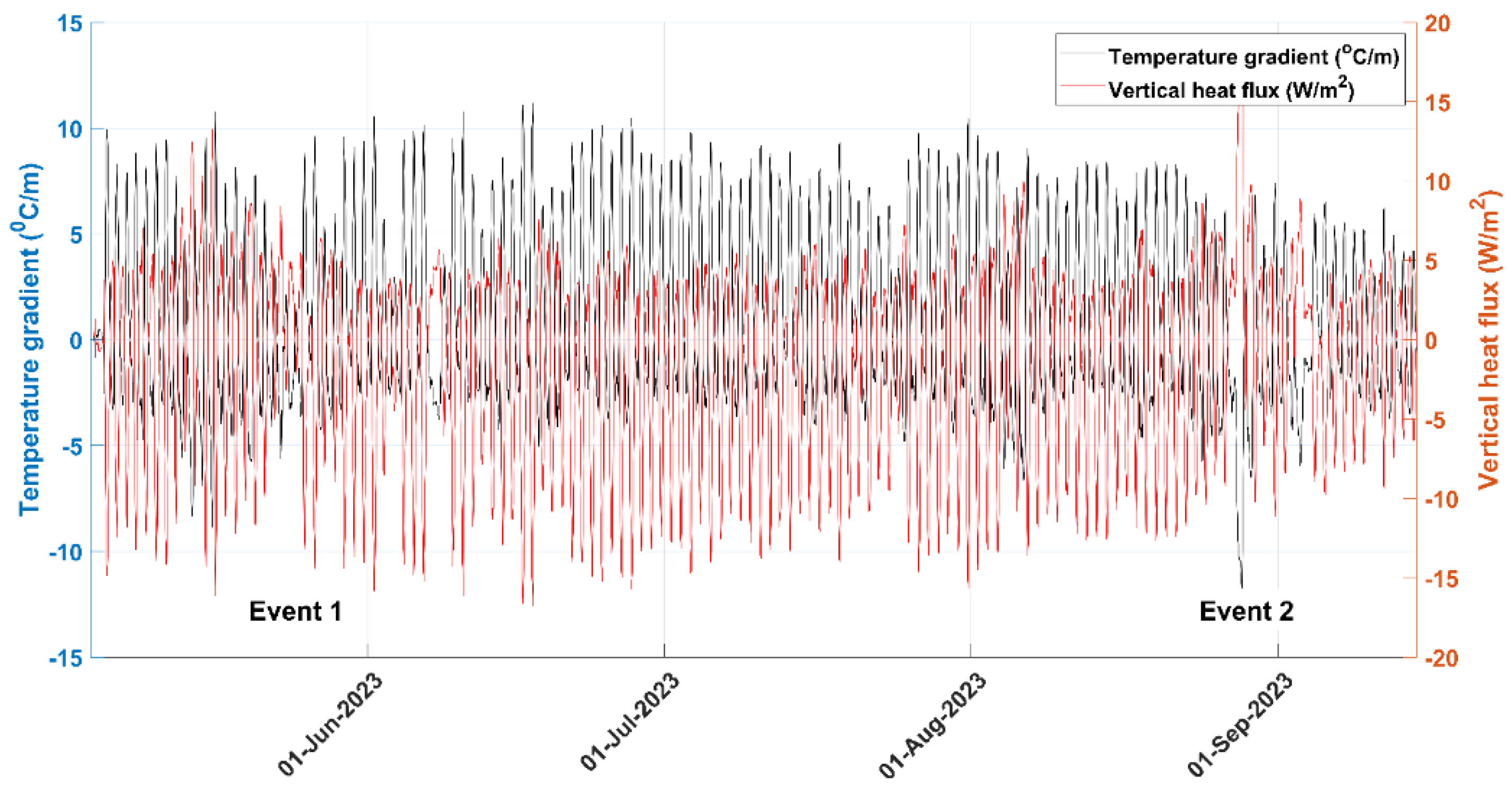

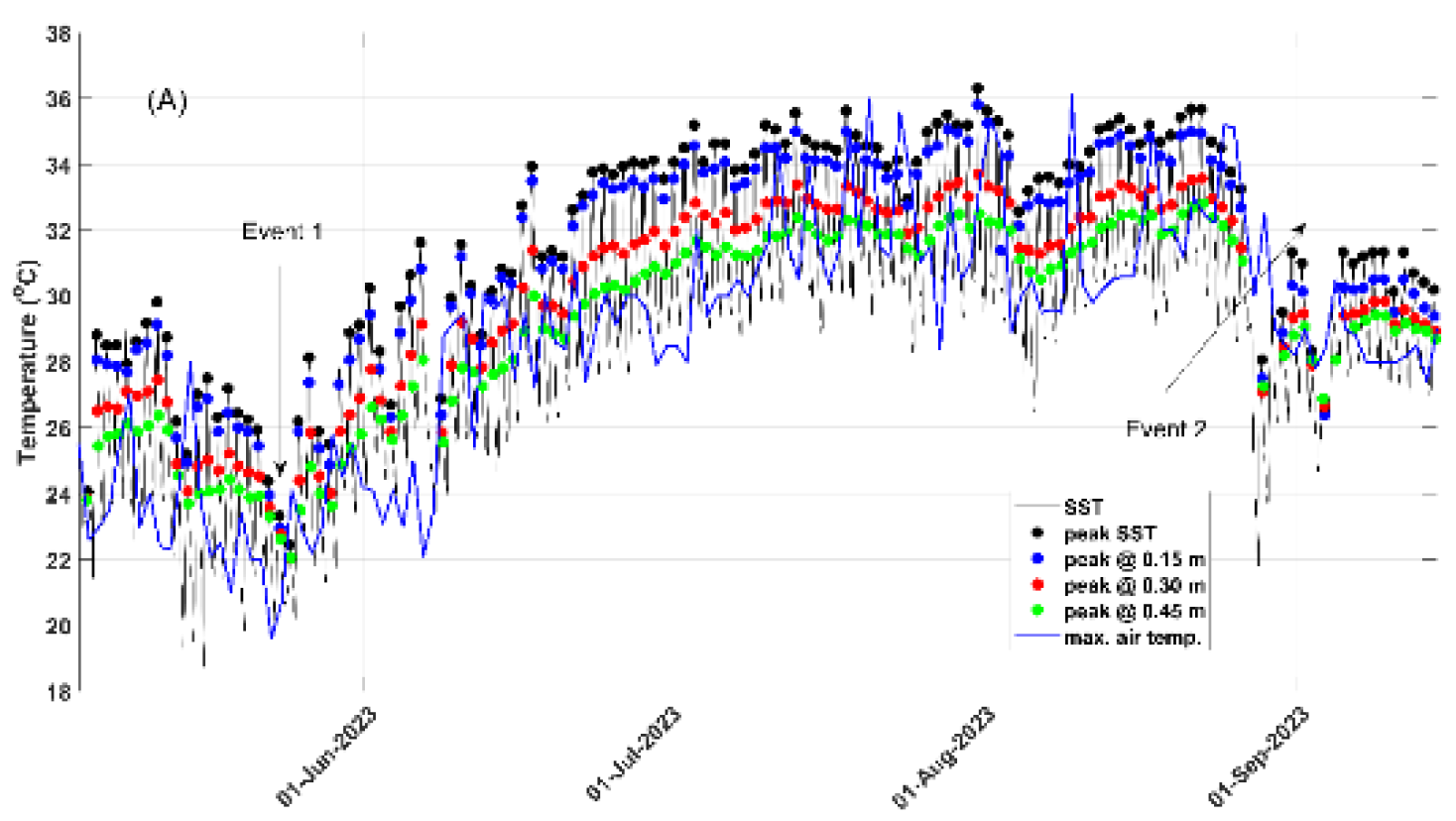

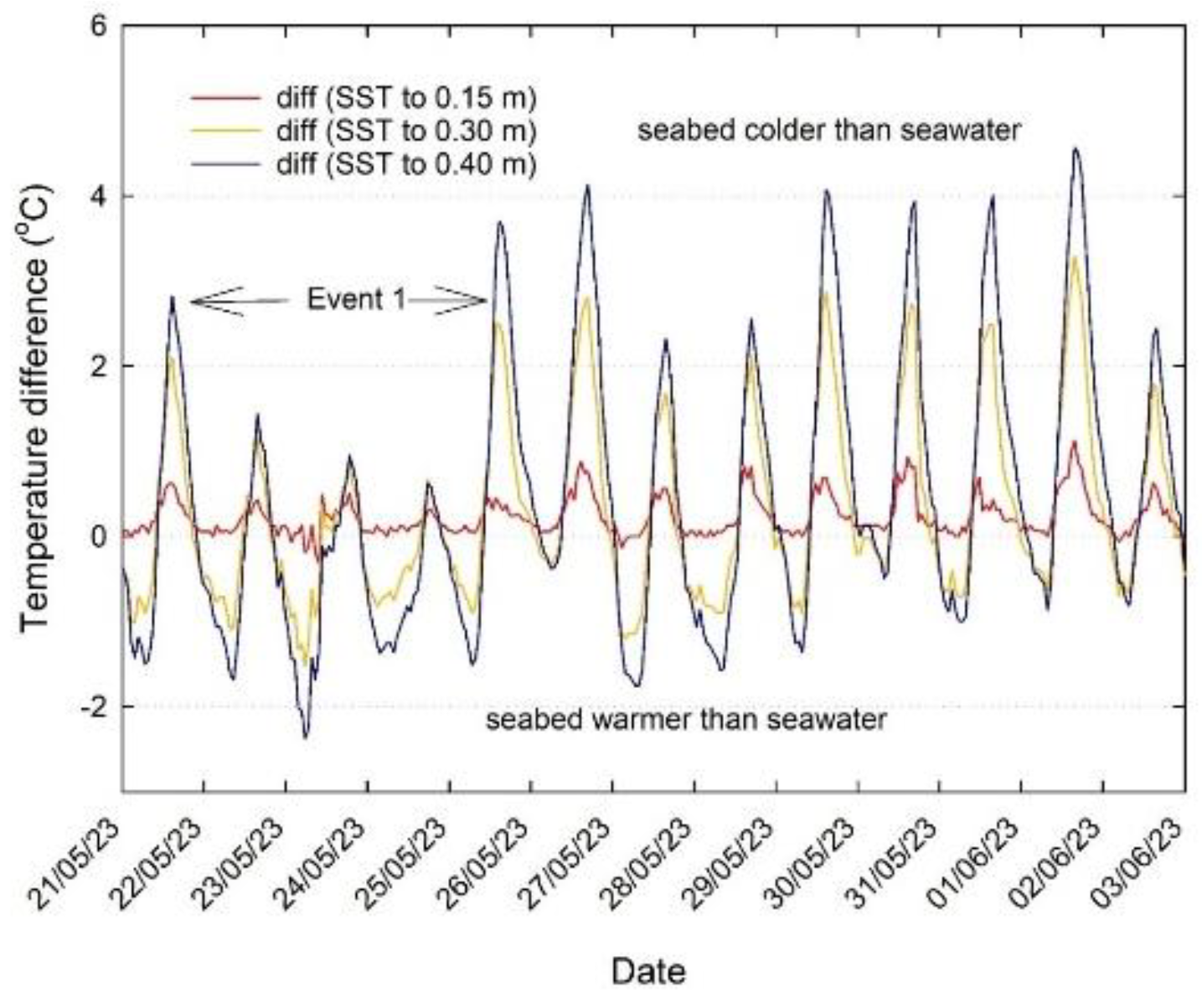

Good quality SST and seabed temperature data were recorded hourly from 10:42, 5 May 2023 to 16:42, 14 September, 2023 in a shallow (0.3 m minimum depth) sandy region of the Mar Menor (See

Figure 1). The time series was dominated by diurnal fluctuations of up to 5

oC, with a steady increase in temperature punctuated by two storm events (22 – 24, May and 26, August – 5 September) referred to herein as “Event 1” and “Event 2” (see Appendices 1 and 2).

Figure 6A shows the SST during this period and the peak (daytime) temperatures from the four temperature sensors. The maximum air temperature from San Javier airport is also shown. It generally falls below the Mar Menor SST and the seabed temperatures within the shallow water setting of the temperature probe with notable exceptions taking place in the two events. Peaks at each depth were not synchronous but were delayed by an average of 4.2±2.3 hours at the deepest sensor. The diurnal variation in the vertical heat flux was large (-20 to 28 W/m

2, negative flux is warming downwards). This variation in vertical temperature difference is illustrated for Event 1 in

Figure 6B.

The figure shows that the temperature gradient inverts on a diurnal frequency illustrating the rapid response of the seabed to changes in heating. That is, the seabed provides heat to the seawater at night. The least-squares best fit of the hourly temperature gradients for the measured duration showed a mean daytime value of -5.99±2.05

oC/m (heating of the seabed) and 2.59±1.51

oC/m at night (cooling of the seabed). The estimated vertical heat flux was -8.99±3.08 W/m

2 during the day and 3.09±2.27 W/m

2 at night. The “dampening” depth (D) of the temperature gradients is estimated from [

39]:

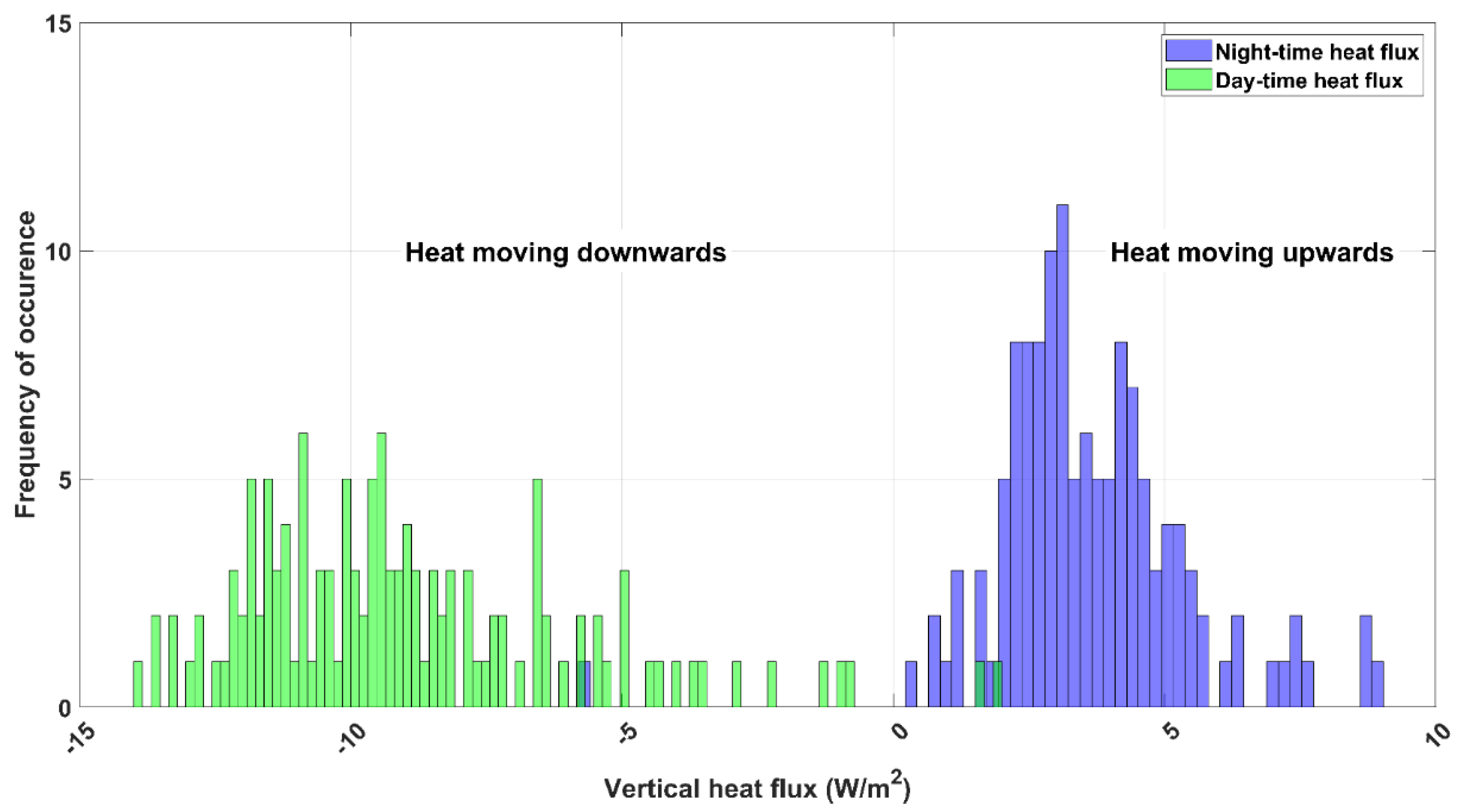

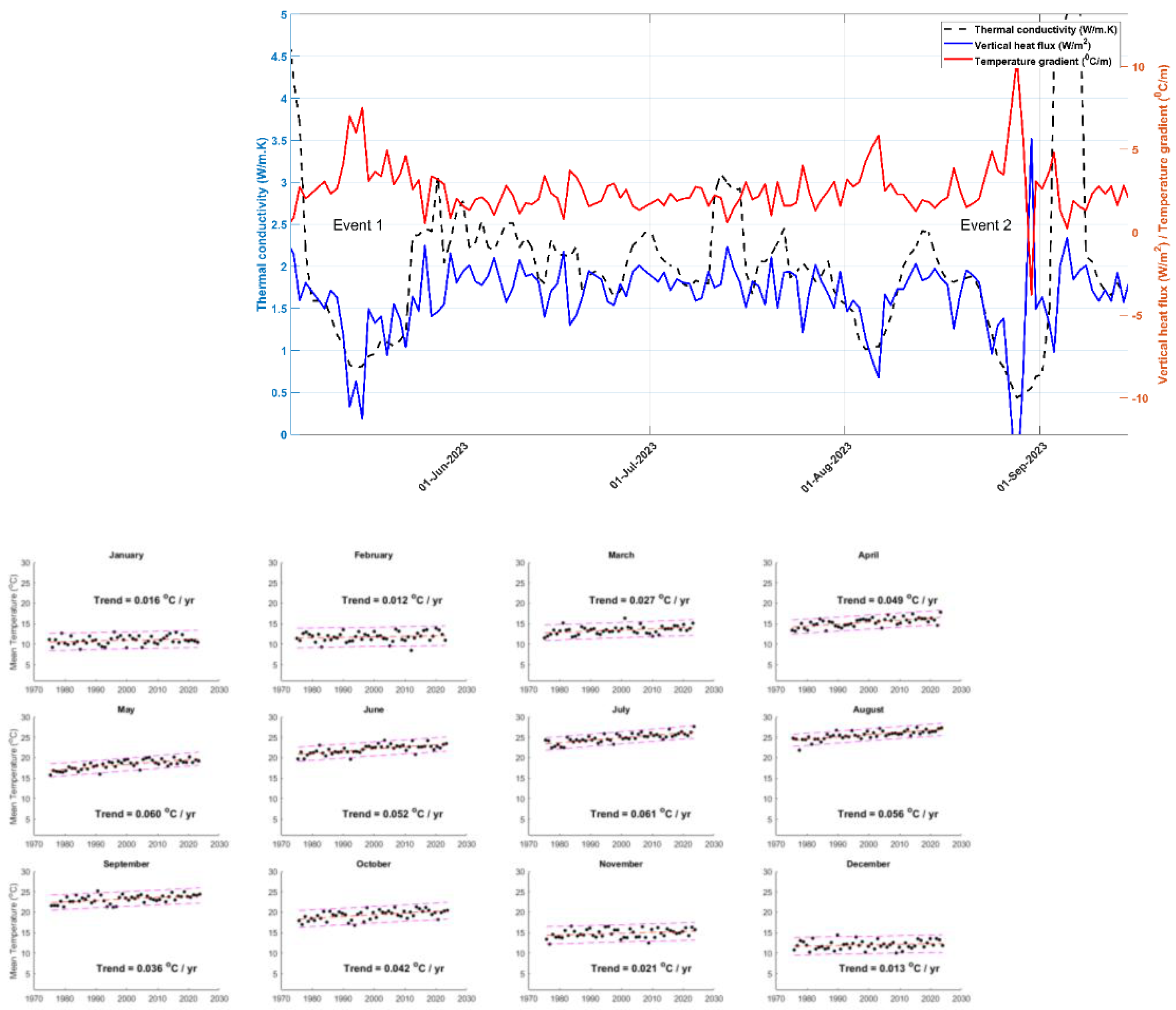

to be 2 m into the seabed. Below this depth, the temperature is assumed to be constant. The vertical heat flux for the time series shows strong diurnal oscillations and rapid changes between the peak in maximum and minimum values.

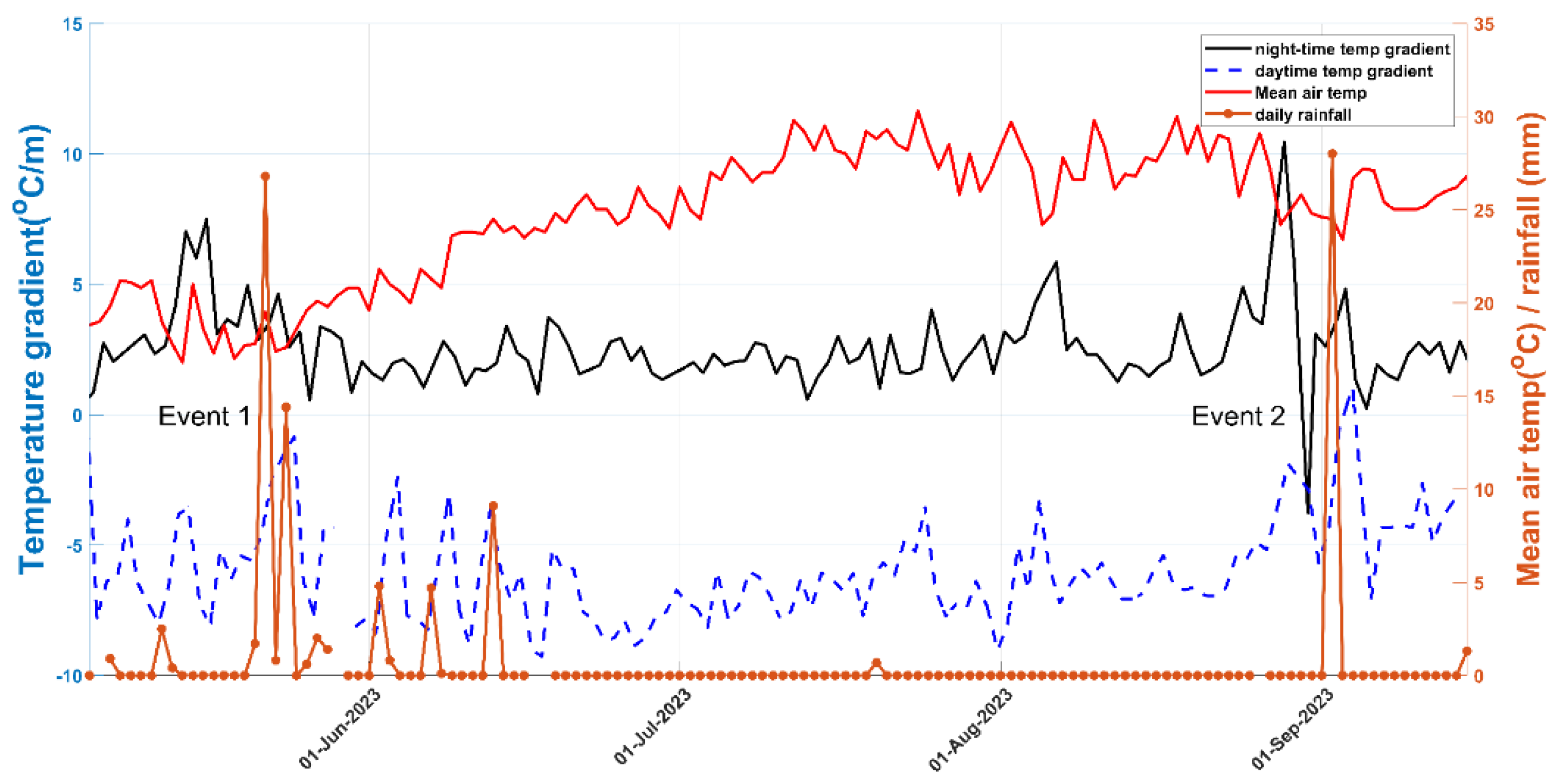

Figure 7 shows results for a sub-set of observations for clarity. It appears that estimates of thermal diffusivity are unstable during periods when the heat flux is changing most (during the day). The day-time peak temperature gradient, thermal conductivity (2.01±0.9 W/m.K), and heat flux (appear to be constant except for the two rainfall events defined earlier. The daytime temperature gradient appears to be highly sensitive to rainfall and less sensitive to air temperature. This is evident in the two events recorded herein that resulted in 26.8 and 28 mm of rainfall respectively. Under these events, the temperature gradient reduced to zero with a lag of 24 hours.

Similar (but smaller) responses were measured during 2nd, 6th and 12th June, 2023 for lower levels of rainfall but similar air temperatures. A similar finding was made by RR06. Time series of the daytime and night-time peak vertical temperature gradients have been plotted against mean air temperature (San Javier airport) and daily rainfall (Appendix 2). The response and lag of the daytime temperature gradient are clear. This contrasts with the night-time gradients that appear to be influenced by events up to 4 days prior to the rainfall events. Under other times, night-time temperature gradients were remarkably constant.

The thermal conductivity of the shelly fine sand of this study site should remain constant as should estimates of thermal diffusivity. A back calculation (using EQ 2) of the mean night-time estimate of conductivity (assuming a constant heat flux of 1.0 W/m

2) was 0.52±0.45 W/m.K and for the daytime (assuming a heat flux of 2.4 W/m

2) was 0.54±0.65 W/m.K. This is lower than the value for marine sediments reported by Foucher et al. (2002), and close to the value for seawater. The estimate of thermal diffusivity using EQ. 2 yielded a value of 6.28 x 10

-6 m

2/s. A mean value of similar sediments is 1.7 x 10

-7 m

2/s [

40,

41]. A lower value herein could result from a lower porosity or thermal capacity of Mar Menor sediment or from a stronger effect of ground water inflow.

The mean monthly air temperature data from San Javier airport for the period 1980 – 2024 (inclusive) have been de-seasoned in a similar fashion to the SST for the Western Mediterranean. The trends for each month of the year are presented in

Figure 8 and tabulated in

Table 1. All but the winter months show significant (p< 0.05) warming trends that peak during the summer months (May – August).

3.3. Step-Wise Regression Analysis

The SST and air temperature data were first used to examine the trends in SST for each month of the year (

Figure 5 and

Figure 8 respectively). These trends (

oC/year) are tabulated in

Table 1 (

oC/decade) together with the level of confidence (p-value). The summer warming evident in

Figure 3 is seen clearly with strongest trends between May and October in the HadSST1.1 data. The MODIS (Mar Menor) trends are greater than the Western Mediterranean. However, the level of significance of the trends are generally low. These trends correspond well to the air temperature trends for the region which do have high levels of significance.

The anomalies in air temperature (AT-a), SST (Mar Menor, SST-MM-a), SST (Western Mediterranean, SST-HAD-a) and NOAA OISST have been used to understand changes in SST in the Mar Menor. Anomalies were chosen to remove the local effects of seasonality. The post 1980 time series are shown in

Figure 4. The peaks and troughs appear to coincide reasonably well. As the Mar Menor SST data set from MODIS started in July, 2002, SST prior to that time was back-filled by regression of the OISST data with the MODIS data post 2002 (r

2 = 0.88, n = 538; p < 0.001).

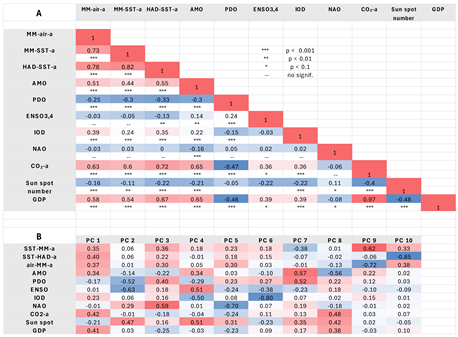

The results of the Spearman correlation analysis of NAO, ENSO3,4, IOD, AMO, PDO, CO2-a, sunspot number, GDP, AT-a and the SST anomaly in the Western Mediterranean (HAD) against SST-a in the Mar Menor are presented in

Table 2A.

3.4. The Principal Component Analysis

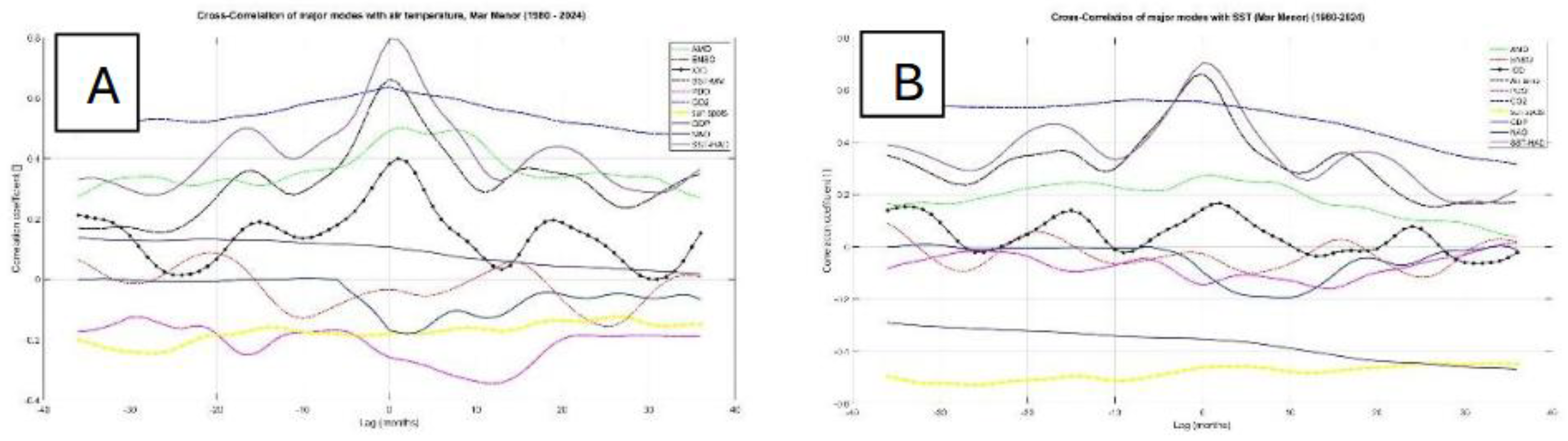

The PCA analysis conducted on mean monthly data from 1980 to 2024 (inclusive) showed that the strongest correlation of SST in Mar Menor was with SST in the adjacent coastal waters with the Mar Menor leading by 1 month. As shown in the heat box model (see later), this is not due to mixing across the inlets. Air temperature showed the next strongest correlation with SST_MM but with zero lag. The strong correlation to CO2 across all lags shows that both are rising in a similar fashion. None of the other ocean indexes showed significant correlations. Curiously, sunspot activity was negatively correlated at all lags supporting the contention of Vinõs (2022) that warming takes place during periods of low sun spot activity: GDP is also inversely related which is diagnostic of the fact that industry is lower during the summers. Air temperature shows similar patterns to the SST in Mar Menor, but also includes a significant contribution of AMO (with 1 to 10 month lags) and IOD (with a 1 month lag). Air temperature appears inversely related to PDO (with a 12 month lag). There is no clear relationship of air temperature with either ENSO3,4, NAO, sunspot activity, or GDP.

Figure 9.

(A) Cross correlations of key parameters with air temperature (San Javier airport) for lags of -36 to 36 months. The strongest correlation (at zero lag) is with the SST in the Western Mediterranean. This is followed by SST in the Mar Menor, CO2, AMO and IOD. Notice there is almost no correlation with GDP. (B) Cross correlations of key parameters with SST in Mar Menor. The strongest correlation is with SST (Western Mediterranean) followed by air temperature, CO2, and AMO. Note the inverse correlation with sunspots and GDP.

Figure 9.

(A) Cross correlations of key parameters with air temperature (San Javier airport) for lags of -36 to 36 months. The strongest correlation (at zero lag) is with the SST in the Western Mediterranean. This is followed by SST in the Mar Menor, CO2, AMO and IOD. Notice there is almost no correlation with GDP. (B) Cross correlations of key parameters with SST in Mar Menor. The strongest correlation is with SST (Western Mediterranean) followed by air temperature, CO2, and AMO. Note the inverse correlation with sunspots and GDP.

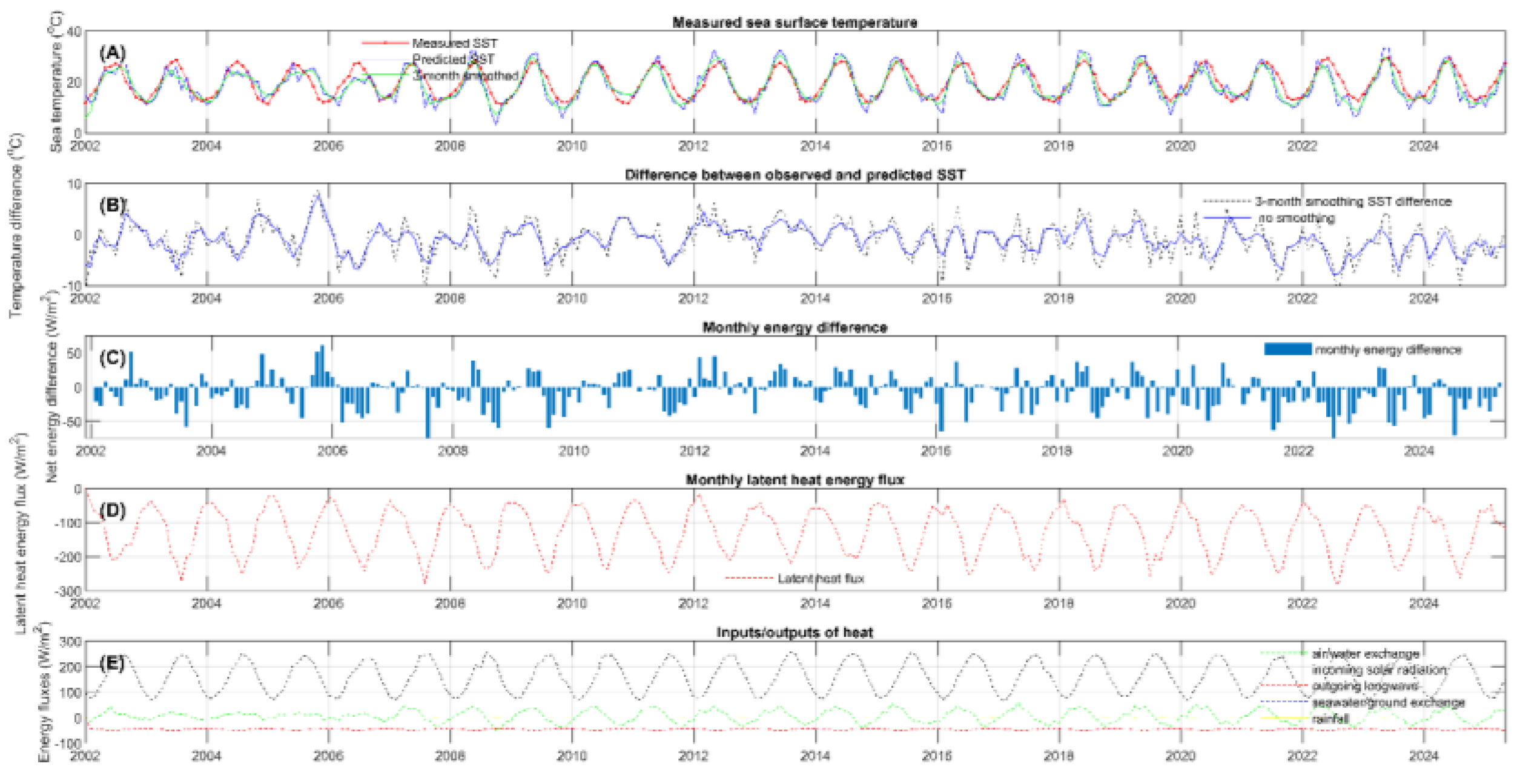

3.5. The Heat Box Model

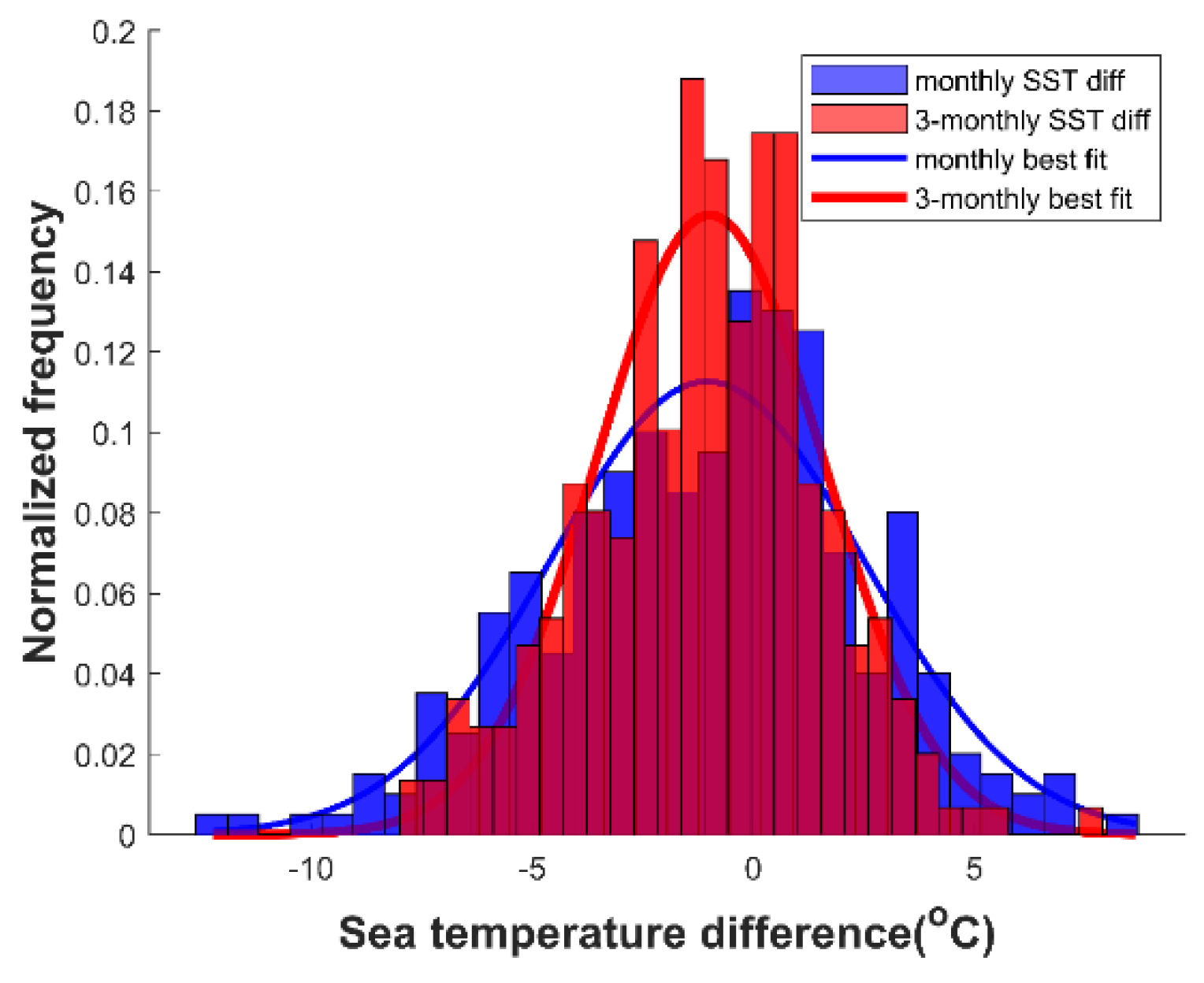

An estimation of the heat budget of the Mar Menor has been evaluated monthly from January, 2002 to May, 2025 inclusive. A balance in the heat budget was sought for the sources of heat (principally incoming solar radiation), outgoing heat (longwave radiation) and the internal exchanges of sensible (air/water, rain, river, and tidal exchanges) and latent heat losses through evaporation. The resulting predicted SST was compared against measured SST derived from MODIS. A first approximation was made to balance the published annual evaporation (m/annum) using EQ 13. Solar radiation at ground level was estimated as 80% of that at the top of the atmosphere. As well, estimates were made with and without the effects of clouds. The best closure with observations was found by neglecting the MERRA 2 average monthly cloud cover as the scatter was reduced by doing so. The same was true for estimates of the outgoing radiation. The resulting estimated time series of SST is shown in

Figure 10A together with the difference between observed and predicted SST (

Figure 10B). A histogram plot of the differences for the entire time series is shown in

Figure 11. The scatter in the differences is Gaussian and yields a standard deviation of ±2.6

oC.

Figure 10D and

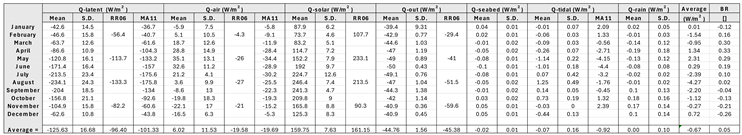

Figure 10E show the time series of the major sources and sinks of heat: incoming solar radiation, outgoing longwave radiation, latent heat flux and the different exchanges of sensible heat. The monthly means and annual values of each is given in

Table 3.

) which is far too small to be detected within the simple model presented.

The influence of tidal exchanges at the three inlets, the sensible exchange through the seabed and the other sources (rain and rivers) were small and had minimal impact on the estimate of SST.

4. Discussion

[

42] have examined SST trends in the north Atlantic during the 20th century, concluding …”

no one should doubt that human activity is largely responsible” and that increasing droughts are likely in the Mediterranean region driven in part by the AMO [

43]. The data examined herein (

Figure 2) suggest that for the Western Mediterranean, at least, the long term trends are also driven by the AMO (which has been increasing in magnitude since circa 1970). The 1980 change in SST regime found herein for the W. Mediterranean is close to the 1976 regime change evident in the Pacific Ocean [

38] which corresponds to a shift in ENSO and PDO patterns and the beginning of the current global warming trend. It is tempting to link the warming of the Mar Menor since 1980 to increases in CO

2 as there is a strong correlation between the two (i.e. they are both rising). However, the lack of a long term trend in SST pre 1980 (when CO

2 was also rising) suggests that regional factors may be more significant drivers. The systematic increase in magnitude of the AMO since circa 1970 together with peaking of the Eddy cycle of solar activity as proposed by [

38] may be the main drivers of trends found herein. The AMO presently appears to be at its peak and is due to decrease during the next 30 years [

38]. If this is so, then we could also anticipate a reduction in SST in the Mar Menor over this time period.

The PCA analysis conducted on mean monthly data from 1980 to 2024 (inclusive) showed that the strongest correlation of SST in Mar Menor was with SST in the adjacent coastal waters with the Mar Menor leading by 1 month. As shown in the box model, this is not due to mixing across the inlets. Air temperature showed the next strongest correlation with SST_MM but with zero lag. The strong correlation to CO

2 across all lags shows that both are rising in a similar fashion. None of the other ocean indexes showed significant correlations. Curiously, sunspot activity was negatively correlated at all lags supporting the contention of [

38] that warming takes place during periods of low sun spot activity: GDP is also inversely related which is diagnostic of the fact that industry activity is lower during the summer. Air temperature shows similar patterns to the SST in Mar Menor, but also includes a significant contribution of AMO (with 1 to 10 month lags) and IOD (with a 1 month lag). Air temperature appears inversely related to PDO (with a 12 month lag). There is no clear relationship of air temperature with either ENSO3,4, NAO, sunspot activity or GDP.

The fluxes of energy into (during the day) and out of (during the night) the Mar Menor seabed fall within reasonable limits. The delay in peak temperature has not been considered as a factor in the estimation of these fluxes. The sensors were initiated sequentially with an approximate 5 minute delay in each case. The sample rate of 1 hour is considered too coarse to evaluate the travel time of heat with depth.

The heat box model for the seawater of the Mar Menor has been used to balance the sources and sinks of heat. Initially, an evaporation rate of 1.3 m [

2] was used to back calculate the relevant mean monthly wind speed given by MERRA 2 at a height of 10 m (U

10) using EQs 5 and 13 to solve for the cumulative evaporation depth (h). This choice proved to predict an evaporation rate of 0.11±0.06 m/month and a mean evaporation rate of 1.29 m/year. The predicted evaporation rate varied considerably with season from a minimum of 0.036 m/year in December to a maximum of 0.20 m/year in August. The years 2002 and 2012-2014 exhibited relatively low summertime evaporation rates.

A multi-year trend in the energy balance appears to be present in the time series (

Figure 10C). This seems related to changes in the summertime peak in latent heat loss (

Figure 10D). Notice that years 2012 to 2014 summertime heat losses are relatively low, while 2006 to 2010 and post 2016 summertime heat losses are relatively high. The air/seawater exchange of sensible heat (

Figure 10E) also appears to be increasing with time: it is low and with low seasonal variation from 2002 to 2007, and generally increasing subsequently. The histogram of the predicted differences between model output and measured SST in

Figure 11 shows that a 3-month smoothing of predictions reduced the scatter. This suggests a month-long residual lag in response to heating not represented in the monthly mean data. The addition of tidal mixing results in a slight cool bias in results. However, it could be omitted from the heat budget estimate (as done by MA11) without loss of information. The overall annual loss of 0.52 W/m

2 in the heat budget estimate is within the estimated error margin and so it may be assumed that the model defines a thermal balance. A mean of 0.43

oC/decade warming of the Mar Menor seawater (see

Table 1) for a mean water depth of 4.5 m equates to a long-term average heat input of 0.024 W/m

2 which is far too small to be detected within the simple model presented herein.

Rainfall has a significant impact on the seabed temperature profile. During event 1 (23 – 26 May, 2023), the daytime temperature gradient was almost eliminated whereas the seabed relative warming at night was enhanced to a maximum of 2.4oC. The same occurred during event 2 (26 – 28 August, 2023), but to a greater degree. During this event the seabed remained consistently warmer than the seawater to a maximum of 5.0oC. The heat is subsequently returned to the water column in the following 24 hours. The air temperature and wind speed were not unusual during these events.

[

15] ignored the effects of freshwater inflow and rainfall in their estimates of the heat budget. The data presented herein (

Table 3) suggest that to do so would have no material impact on their results. The impact of heat exchange with the ground, however, can have considerable impact on the day-night vertical temperature gradients at diurnal time scales if not longer; cooling seawater by day and warming it by night. MA11 estimated the mean annual Bowen ratio to be 0.19, which is typical of Mediterranean coastal lagoons: data herein suggests it varies throughout the year from -0.26 in December to 0.33 in April (mean = 0.053±0.21). MA11 show a slightly lower latent heat loss then found herein (see

Table 3), which can be explained through differences in the air vapor pressure and relative humidity.

Figure 4 and

Figure 10 illustrate that the period 2003 to 2006 exhibited relatively mild winters and a narrower range of seasonal SST. This is due in part to the greater than average summertime latent heat losses during this period. Much of the differences between MA11 and those presented herein are considered due to the decadal changes in heat sources and sinks much of which is considered due to changes in the impact of the AMO.

[

14] have estimated that the heat loss as long-wave radiation from a small lagoon in Spain was 70% of non-advective heat losses, and evaporation accounted for 20% of total energy heat losses. The values estimated herein were 26% and 70% respectively (see

Table 3) i.e. the inverse. The remarkable similarity in heat fluxes presented by RR06 to those found herein, suggests similar ratios. The systematic increase in annual heat flux due to evaporation since 2006 (evident in

Table 3) may be due to the long-term warming trends in air temperature and SST.

5. Conclusions

Long-term records of SST from the Western Mediterranean indicate that there was no trend prior to circa 1980 but appeared to respond on a decadal scale to the AMO and on an annual scale to the NAO [

26,

44]. Post 1980 SST showed significant increases of 0.34

oC/decade (maximum) and 0.21

oC/decade (minimum). This compared with 0.39

oC/decade for the Mediterranean Sea as a whole (Cusack and Cox, 2025) There were significant (p < 0.05) increases for all months of the year. The onset of warming appears to lag the 1976 inflection in SST in the Pacific Ocean and is attributed to changes in ENSO and PDO [

38].

Air temperature trends in the Mar Menor region have shown significant systematic warming since 1980 at all months of the year. Peak warming takes place in the summer months (maximum of 0.61oC/decade in July).

A spearman rank correlation of the SST anomaly in the Mar Menor (2000 - 2024) showed strong and significant correlations with (in order) SST in the Western Mediterranean, CO2, Spanish national GDP, and the AMO. It was inversely correlated with the PDO and sunspot activity. A similar finding resulted from a PCA analysis of variables which also showed the importance of the IOD.

Measured heat exchanges between the seabed and the water column in the Mar Menor showed strong diurnal inversions of temperature gradient resulting in a daytime heat flux of -8.99±3.08 W/m2 and a night-time reversal of 3.89±2.27 W/m2 resulting in a warming of the seabed with time. The estimated depth of temperature fluctuations in the seabed was 2 m. The 5 months of hourly measurements showed that rainfall had the greatest effect on seabed temperature and heat exchange with the water column. Also clear, was the fact that a sampling rate of 1/hour is insufficient to accurately predict thermal diffusivity of conductivity of the seabed sediments. A reasonable estimate of heat flux, however, was achieved using the diurnal maxima and minima at a sample rate of 1 /hour.

A heat budget box model of SST in the Mar Menor was developed as an extension of that presented by MA11. Predictions using added inputs that included tidal mixing, seabed/water exchanges and river inflow. A balance to within ±2.6oC was derived over a prediction period from January, 2002 to December, 2024 resulting in a insignificant heat loss of -0.52 W/m2. Results herein agree with MA11 that the dominant sources and sinks of heat are solar radiation and evaporation; other terms appear insignificant to the outcome. Incoming solar and outgoing latent heat losses (through evaporation) were close to those estimated by RR06 in an adjacent lagoon and based upon daily measurements made over a single year. The use of mean monthly data (herein) thus appears to be justified in terms of examining the heat budget of lagoons such as the Mar Menor.

Author Contributions

Methodology, CLA and HK, satellite data acquisition TA and CLA, analysis and interpretation, CLA, HK, and V M-A, writing, CLA, review and editing, HK and V M-A. All authors have read the manuscript and agree with the published version.

Funding

This work was self-funded by the first author and supported by the University of Southampton.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this manuscript are available upon request from the first author. Matlab scripts can also be obtained from the same source. Appendixes to this paper are provided in the way of supplementary plots, also available from the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Zn |

zinc |

| Cd |

cadmium |

| Pb |

lead |

| HadSST1.1 |

Hadley Centre global compilation of sea surface temperature |

| SST |

Sea surface temperature |

| SST-HAD |

Sea surface temperature (Western Mediterranean) |

| SST-MM |

Sea surface temperature (Mar Menor, Spain) |

| MODIS |

Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (NASA) |

| OISST |

Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (NOAA) |

| AMO |

Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation |

| IOD |

Indian Ocean Dipole |

| GDP |

Gross Domestic Product |

| PDO |

Pacific Decadal Oscillation |

| NAO |

North Atlantic Oscillation |

| ENSO3,4 |

El Nino Southern Oscillation (east central Pacific) |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| SHYFEM |

Shallow Water Hydrodynamic Finite Element Model |

| ASCII |

American Standard Code for information Interchange |

| MERRA 2 |

Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research Applications, Version 2 |

| AT |

Air temperature |

Appendix A

Appendix A1.

The thermal gradient estimated by best fit linear regression of the instantaneous temperature values measured hourly between 4th May and 14th September, 2023. The heat flux has been estimated using Fourier’s Law (see text) assuming a constant thermal conductivity of 1.5 W/m.K (Farouki, 1986). Note the impact of the two rainfall “Events” on the seabed temperature gradients (22-24 May and 26 August – 5 September). The rapid diurnal changes in temperature gradient is noted as well as the inversion of the gradient on a diurnal frequency. As a result, only the diurnal peak maxima and minima values were used to define the temperature gradient within the seabed.

Appendix A1.

The thermal gradient estimated by best fit linear regression of the instantaneous temperature values measured hourly between 4th May and 14th September, 2023. The heat flux has been estimated using Fourier’s Law (see text) assuming a constant thermal conductivity of 1.5 W/m.K (Farouki, 1986). Note the impact of the two rainfall “Events” on the seabed temperature gradients (22-24 May and 26 August – 5 September). The rapid diurnal changes in temperature gradient is noted as well as the inversion of the gradient on a diurnal frequency. As a result, only the diurnal peak maxima and minima values were used to define the temperature gradient within the seabed.

Appendix A2.

The peak diurnal vertical temperature gradients in the seabed (oC/m) for both the daytime (negative means warming downwards) and night-time (warming upwards). The peak daytime air temperature demonstrated a steady increase from about 20oC to more than 30oC. Notice the steady night-time peak gradient is evident except for the two major rainfall events. The peak daytime temperature gradient also appears to be strongly affected by rainfall (with a delay of about 24 hours) and less sensitive to changes in air temperature.

Appendix A2.

The peak diurnal vertical temperature gradients in the seabed (oC/m) for both the daytime (negative means warming downwards) and night-time (warming upwards). The peak daytime air temperature demonstrated a steady increase from about 20oC to more than 30oC. Notice the steady night-time peak gradient is evident except for the two major rainfall events. The peak daytime temperature gradient also appears to be strongly affected by rainfall (with a delay of about 24 hours) and less sensitive to changes in air temperature.

Appendix A3.

A histogram of the heat fluxes estimated from the thermal probe deployed in the Mar Menor between 4th May and 14th September, 2023. The estimated peak negative heat flux shows warming of the seabed. The night-time cooling of the bed (positive heat flux) indicates a transfer of heat to the water column reducing subsequently the heat loss. The wide variation in day-time warming of the seabed reflects changes in cloud cover, wind speed, and to a lesser extent changes in air temperature.

Appendix A3.

A histogram of the heat fluxes estimated from the thermal probe deployed in the Mar Menor between 4th May and 14th September, 2023. The estimated peak negative heat flux shows warming of the seabed. The night-time cooling of the bed (positive heat flux) indicates a transfer of heat to the water column reducing subsequently the heat loss. The wide variation in day-time warming of the seabed reflects changes in cloud cover, wind speed, and to a lesser extent changes in air temperature.

References

- Álvarez-Rogel, J., Barberá, G.G., Maxwell, B., Guerrero-Brotons, M., Díaz-García, C., Martínez-Sánchez, J.J., Sallent, A., Martínez-Ródenas, J., González-Alcaraz, M.N., Jiménez-Cárceles, F.J., Tercero, C. and Gómez, R. The case of Mar Menor eutrophication: State of the art and description of tested nature-based solutions. Ecological Engineering, 2020, 158(1), 106086. [CrossRef]

- Senent-Aparacio, J., Lopez-Ballesteros, A., Nielsen, A., and Trolle, D. A holistic approach for determining the hydrology of the mar menor coastal lagoon by combining hydrological & hydrodynamic models. Journal of Hydrology, 2021, 603(D), 127150. [CrossRef]

- Conesa, H.M., and Jiménez-Cárceles, F. The Mar Menor lagoon (SE Spain): A singular natural ecosystem threatened by human activities. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2007, 54(7), 839-849. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Rogel, J., Ramos-Aparicio, M.J., Delgado-Iniesta, M.J., and Arnaldos-Lozano, R. Metals in soils and above-ground biomass of plants from a salt marsh polluted by mine wastes in the coast of the Mar Menor Lagoon, SE Spain. Fresenius Environmental Bulletin, 2004, 13, 274-278.

- Jiménez-Martínez, J., García-Aróstegui, J.L., Hunink, J., Contreras, S., Baudron, P., Candela, L. The role of groundwater in highly human-modified hydrosystems: A review of impacts and mitigation options in the Campo de Cartagena-Mar Menor coastal plain (SE Spain). Environmental Reviews, 2016, 24 (4). [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.H.; Kump, L.R., and Cantrell, K.J. The influence of temperature and pH on trace metal speciation in seawater. Marine Chemistry, 1988, 25(2), 163-181. [CrossRef]

- Fong, P. and Zedler, J.B. Temperature and light effects on the seasonal succession of algal communities in shallow coastal lagoons. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 1993, 171, 259-272. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Matín, M.A. Understanding Nutrient Loads from Catchment and Eutrophication in a Salt Lagoon: The Mar Menor Case. Water, 2023, 15, 3569. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ruzafa, A., Fernández, A.I., Marcos, C., Gilabert, J., Quispe, J.I., García-Charton, J.A. Spatial and temporal variations of hydrological conditions, nutrients and chlorophyll a in a Mediterranean coastal lagoon (Mar Menor, Spain). Hydrobiologia, 2005, 550, 11–27. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Puig, J., Rodellas, V., and others. Seasonality of submarine groundwater discharge pathways in a coastal lagoon revealed by radium isotopes: the importance of porewater exchange in summer. Journal of Hydrology, 2025, 661, 133616. [CrossRef]

- Bauraï, L.; Logez, M.; Laplace-Treyture, C. and Argillier, C. How do eutrophication and temperature interact to shape the commnity structures of phytoplankton and fish in lakes ? Water, 2020, 122(3), 779. [CrossRef]

- Lloret, J. and others. LAGOONS Deliverable D2.1c: The Mar Menor lagoon – current knowledge base and knowledge gaps. Technical Report, 2012. [CrossRef]

- García-Oliva, M., Pérez-Ruzafa, Á., Umgiesser, G., McKiver, W., Ghezzo, M., De Pascalis, F., and Marcos, C. Assessing the Hydrodynamic Response of the Mar Menor Lagoon to Dredging Inlets Interventions through Numerical Modelling. Water, 2018, 10, 959. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, M., and Moreno-Ostos, E. Heat budget, energy storage and hydrologycal regime in a coastal lagoon. Limnologica, 2006, 36, 217-227. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Alvarez, V., Gallego-Elvira, B., Maestre-Valero, J.F., and Tanguy, M. Simultaneous solution for water, heat and salt balances in a Mediterranean coastal lagoon (Mar Menor, Spain). Estuarine Coastal & Shelf Science, 2011, 91, 250–261. [CrossRef]

- De Pascalis, F., Pérez-Ruzafa, A., Gilabert, J., Marcos, C., Umgiesser, G. Climate change response of the Mar Menor coastal lagoon (Spain) using a hydrodynamic finite element model. Estuarine Coastal & Shelf Science, 2012, 114, 118–129. [CrossRef]

- Lau, Y.L. Temperature effect on settling velocity and deposition of cohesive sediments. Journal of Hydraulics Research, 1994, 32(1), 41-51. [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, S., and Chandra, V. Experimental investigation of water temperature influence on suspended sediment concentration. Environmental Processes, 2019, 6, 511–523. [CrossRef]

- Bellino, A., Mangano, M.C., Baldantoni, D., Russell, B.D., Mannino, A.M., Mazzola, A., Vizzini, S., and Sarà, G. Seasonal patterns of biodiversity in Mediterranean coastal lagoons. Diversity and Distributions, 2019, 25(10), 1512-1526. [CrossRef]

- Al-Banaa, K. and Rakha, K. Seasonal variability of temperature measurements in shallow bay. Journal of Coastal Research, 2009, 56, 782-786.

- Amos, C.L. , Umgiesser, G., Ghezzo, M., Kassem, H., and Ferrarin, C. Sea surface temperature trends in Venice lagoon and the adjacent waters. Journal of Coastal Research, 2016, 33(2). [CrossRef]

- Kassem, H.; Amos, C.L., and Thompson, C.E.L. Sea surface temperature trends in the coastal zone of southern England. Journal of Coastal Research, 2022, 39(1). [CrossRef]

- O’Carroll, A.G., Armstrong, E.M., Beggs, H.M. and others. Observational needs of sea surface temperature. Frontiers of Marine Science, 2019, 6,420. [CrossRef]

- Farouki, O.T. Thermal Properties of Soils. Technical Publications, 1986, ISBN 0-87849-055-8 . [CrossRef]

- Rayner, N.A., Parker, D.E., Horton, E.B., Folland, C.K., Alexander, L.V., Rowell, D.P., Kent, E.C., and Kaplan, A. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. Journal of Geophysical Research, 2003, 108(D14): 4407. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Monteiro, S., Sobrino, J.A., Julien, Y., Soria, G., and Skokovic, D. Surface temperature trends in the Mediterranean Sea from MODIS data during years 2003-2019. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 2022, 49, 102086. [CrossRef]

- Findley, D.F., Monsell, B.C., Bell, W.R., Otto, M.C., and Chen, B.C. New capabilities and methods of the X-12_ARIMA seasonal-adjustment program. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 1998, 16(2), pp. 127-152.

- Williams, G.P. Chaos Theory Tamed, Publ. Taylor and Francis, London, 1997, 499p.

- Becker, G.A. and Pauly, M. Sea surface temperature changes in the North Sea and their causes. Journal of Marine Science, 1996, 53, 887-898. [CrossRef]

- Xue, M., and Li, T. To what extent does ENSO rectify the tropical Pacific mean state ? Climate Dynamics, 2023, 61, 3875-3891. [CrossRef]

- Gill, A.E. Atmosphere-Ocean Dynamics. Publ. Academic Press, Paris, 1982, 663p.

- Csanady, G.T. Air-Sea Interaction. Publ. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2012, 239p.

- Middleton, G.V. and Southard, J.B. Mechanics of Sediment Movement. SEPM Short Course, 1984, No. 3.

- Sultan, S.A.R., and Ahmad, F. Heat budget of the coastal water of Kuwait: a preliminary study. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 1994, 38, 319-325. [CrossRef]

- Humlum, O., The State of the Climate 2021. Report 51, The Global Warming Policy, Foundation, 2022, 54p.

- Hegerl, G.C., Brönnimann, S., Cowan, T., Friedman, A.R., Hawkins, E., Iles, C., Müller, W., Schurer, A., and Undorf, S. Causes of climate change over the historical record. Environmental Research Letters, 2019, 14, 123006. [CrossRef]

- Cusack, S. and Cox, T. Brief communication: Drivers of the recent warming of the Mediterranean Sea, and its implications for hail risk. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 2025, 25(9), 2963-2972. [CrossRef]

- Vinõs, J. Climate of the Past, Present and Future. A Scientific Debate. Publ. Critical Science Press, Madrid, 2022, 740p.

- Harrison, S.J., and Phizacklea, A.P. Temperature fluctuation in muddy intertidal sediments, Forth estuary, Scotland. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 1987, 24, 279-288. [CrossRef]

- Bullard, E.C., 1954. The flow of heat through the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 2019, 222, 408-429. [CrossRef]

- Foucher, J.P.; Nouzé, H., and Henry, P. Variability of heat flow at the western Mediterranean continental margin. Marine Geology, 2002, 182, 109-128.

- Cane, M.A. and Lee, D.E. What do we know about the climate of the next decade? In: food Security and Sociopolitical Stability. (Barrett, C.B., ed) Publ. Oxford University Press, 2013, 64-94.

- Marullo, S.: Artale, V., and Santoleri, R. The SST multidecadal variability in the Atlantic-Mediterranean region and its relation to AMO. Journal of Climate, 2011, 24(16), 4385-4401. [CrossRef]

- Tsimplis, M.N., Calafat, F.M., Marcos, M., Jordà, G., Gomis, D., Fenoglio-Marc, L., Struglia, M.V., Josey, S.A., and Chambers, D.P. The effect of the NAO on sea level and on mass changes in the Mediterranean Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research, Oceans, 2013, 118(2), 944-952. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A location diagram of the Mar Menor lagoon, Spain. Also shown are the key locations referred to in the text.

Figure 1.

A location diagram of the Mar Menor lagoon, Spain. Also shown are the key locations referred to in the text.

Figure 2.

(A) A time series of mean monthly SST in the Western Mediterranean between 1900 and 2024 (inclusive). The short-term peaks and troughs appear to map to those of the NAO (B), while the long-term trends in SST appear to be controlled by the AMO (C). More detailed correlations are examined further in the text. Note that the temperature appears to increase after circa 1976; no clear long-term trend in SST is apparent before this date. For this reason, data post 1980 are used in the analysis of recent trends.

Figure 2.

(A) A time series of mean monthly SST in the Western Mediterranean between 1900 and 2024 (inclusive). The short-term peaks and troughs appear to map to those of the NAO (B), while the long-term trends in SST appear to be controlled by the AMO (C). More detailed correlations are examined further in the text. Note that the temperature appears to increase after circa 1976; no clear long-term trend in SST is apparent before this date. For this reason, data post 1980 are used in the analysis of recent trends.

Figure 3.

A sub-set of the data set in

Figure 2 showing the maximum and minimum mean monthly SST from 1932 to 1980 (no trends found) and 1980 to 2024. Maximum and minima SST trends post 1980 show significant upward trends. Maxima appear to be increasing faster (0.34

oC/decade) than the minima (0.21

oC/decade).

Figure 3.

A sub-set of the data set in

Figure 2 showing the maximum and minimum mean monthly SST from 1932 to 1980 (no trends found) and 1980 to 2024. Maximum and minima SST trends post 1980 show significant upward trends. Maxima appear to be increasing faster (0.34

oC/decade) than the minima (0.21

oC/decade).

Figure 4.

Temperature anomalies for the period 1980 – 2024 (inclusive) showing the Mar Menor SST anomaly, air temperature anomaly (San Javier airport), HadSST1.1 (Western Mediterranean) anomaly, and OISST anomaly. The trends in SST of the Mar Menor are similar to those further afield and also co-vary with air temperature. However, the Mar Menor SST anomaly appears lower that other anomalies, particularly during winter. The 1991-1993 cooling appears to correspond to the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in June, 1991 (see Vinõs, 2022 for discussion).

Figure 4.

Temperature anomalies for the period 1980 – 2024 (inclusive) showing the Mar Menor SST anomaly, air temperature anomaly (San Javier airport), HadSST1.1 (Western Mediterranean) anomaly, and OISST anomaly. The trends in SST of the Mar Menor are similar to those further afield and also co-vary with air temperature. However, the Mar Menor SST anomaly appears lower that other anomalies, particularly during winter. The 1991-1993 cooling appears to correspond to the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in June, 1991 (see Vinõs, 2022 for discussion).

Figure 5.

SST trends from the Western Mediterranean from 1980 – 2024 (inclusive) for each month of the year. The trends are based on a least squares best fit regression analysis. All trends are significant at p < 0.01. Also shown are the 95% confidence limits of the fits. Notice the greatest warming takes place in the summer and the least (even cooling) takes place in the winter. The warming rates are listed in

Table 1.

Figure 5.

SST trends from the Western Mediterranean from 1980 – 2024 (inclusive) for each month of the year. The trends are based on a least squares best fit regression analysis. All trends are significant at p < 0.01. Also shown are the 95% confidence limits of the fits. Notice the greatest warming takes place in the summer and the least (even cooling) takes place in the winter. The warming rates are listed in

Table 1.

Figure 6.

(A). SST measured at h = 0.15 m at the probe site (see

Figure 1) together with the temperatures within the seabed at depths of 0.15, 0,30 and 0.45 m. Also shown is the daily maximum air temperature at San Javier airport. A general increase in both SST and air temperature is noted despite strong diurnal fluctuations. SST leads, and is greater than, air temperature Also note the two cooling events (24th May and 27th August) due to heavy rainfall. (B). The difference in temperatures between the four depths expanded to show the 24th May rainfall event. Note the near 6

oC swing in temperatures compared to SST at 0.45 m depth, which has been muted during the May event.

Figure 6.

(A). SST measured at h = 0.15 m at the probe site (see

Figure 1) together with the temperatures within the seabed at depths of 0.15, 0,30 and 0.45 m. Also shown is the daily maximum air temperature at San Javier airport. A general increase in both SST and air temperature is noted despite strong diurnal fluctuations. SST leads, and is greater than, air temperature Also note the two cooling events (24th May and 27th August) due to heavy rainfall. (B). The difference in temperatures between the four depths expanded to show the 24th May rainfall event. Note the near 6

oC swing in temperatures compared to SST at 0.45 m depth, which has been muted during the May event.

Figure 7.

The night-time peak temperature gradients (mean = 2.54±1.51oC/m), the estimated vertical heat flux (mean = 3.89±2.27 W/m2) and the back-estimated thermal conductivity (2.01±0.90 W/m.K) derived from the night-time temperatures gradients measured with the thermal probe. Notice the reasonably steady estimates except for the two rainfall events defined in the text.

Figure 7.

The night-time peak temperature gradients (mean = 2.54±1.51oC/m), the estimated vertical heat flux (mean = 3.89±2.27 W/m2) and the back-estimated thermal conductivity (2.01±0.90 W/m.K) derived from the night-time temperatures gradients measured with the thermal probe. Notice the reasonably steady estimates except for the two rainfall events defined in the text.

Figure 8.

Mean air temperature trends for the Mar Menor for the period 1980 – 2024. As with the SST, the greatest warming takes place in the summer months and the least during winter. The trends are tabulated in

Table 1. Trends from March to November are significant for p < 0.05.

Figure 8.

Mean air temperature trends for the Mar Menor for the period 1980 – 2024. As with the SST, the greatest warming takes place in the summer months and the least during winter. The trends are tabulated in

Table 1. Trends from March to November are significant for p < 0.05.

Figure 10.

(A) A time series of the heat box model of the Mar Menor evaluated monthly between January, 2002 and May, 2025 (inclusive); (B) The heat budget simulates the observed SST with a non-seasonal Gaussian scatter with a mean of near-zero and a SD of ±2.6

oC (see

Figure 11); (C) - (E) show the time series of the estimated major sources and sinks of heat. Note the multi-year periods of negative and positive energy balance that is evident in the changes in latent heat loss shown in (D).

Figure 10.

(A) A time series of the heat box model of the Mar Menor evaluated monthly between January, 2002 and May, 2025 (inclusive); (B) The heat budget simulates the observed SST with a non-seasonal Gaussian scatter with a mean of near-zero and a SD of ±2.6

oC (see

Figure 11); (C) - (E) show the time series of the estimated major sources and sinks of heat. Note the multi-year periods of negative and positive energy balance that is evident in the changes in latent heat loss shown in (D).

Figure 11.

A histogram of the difference (diff) between observed and predicted SST from the heat box model of this study together with Gaussian best fits (1 month and 3 month averages). There is little bias in the data. The standard deviation of the scatter, however is large (± 2.6oC). 3-month averaging reduces the scatter in predictions and draws the predictions closer to the observed values. The Gausian shape of the scatter suggests that the errors in the model are random with no seasonal residual signal.

Figure 11.

A histogram of the difference (diff) between observed and predicted SST from the heat box model of this study together with Gaussian best fits (1 month and 3 month averages). There is little bias in the data. The standard deviation of the scatter, however is large (± 2.6oC). 3-month averaging reduces the scatter in predictions and draws the predictions closer to the observed values. The Gausian shape of the scatter suggests that the errors in the model are random with no seasonal residual signal.

Table 1.

Least squares best fits of the temperature trends between 1980 and 2024 (inclusive) for (1) the W. Mediterranean (HadSST1.1); (2) Mar Menor (MODIS), and (3) air temperature measured at San Javier airport (see

Figure 1). Almost all trends show significant warming. The Mar Menor appears to be warming at about twice the rate of the W. Mediterranean for most months of the year (low significance) and follows closely the warming of air temperature (high significance).

Table 1.

Least squares best fits of the temperature trends between 1980 and 2024 (inclusive) for (1) the W. Mediterranean (HadSST1.1); (2) Mar Menor (MODIS), and (3) air temperature measured at San Javier airport (see

Figure 1). Almost all trends show significant warming. The Mar Menor appears to be warming at about twice the rate of the W. Mediterranean for most months of the year (low significance) and follows closely the warming of air temperature (high significance).

Table 2.

(A) Spearman rank correlation coefficient matrixes of factors form the Mar Menor for the period January, 1980 – December, 2024. The level of significance (p-value) is also given. Note the high correlations of CO2 anomaly (a), GDP, and AMO with air temperature and air temperature anomaly and HADSST anomaly in Mar Menor. (B) A principal component analysis (10 eigenvectors) showing the correlation matrix as given in (A). PC1 explains 41.9% of the total variance and shows the strong influences of AMO, IOD, CO2 anomaly and GDP on SST anomaly in Mar Menor and air temperature.

Table 2.

(A) Spearman rank correlation coefficient matrixes of factors form the Mar Menor for the period January, 1980 – December, 2024. The level of significance (p-value) is also given. Note the high correlations of CO2 anomaly (a), GDP, and AMO with air temperature and air temperature anomaly and HADSST anomaly in Mar Menor. (B) A principal component analysis (10 eigenvectors) showing the correlation matrix as given in (A). PC1 explains 41.9% of the total variance and shows the strong influences of AMO, IOD, CO2 anomaly and GDP on SST anomaly in Mar Menor and air temperature.

Table 3.

The estimated sources and sinks of heat (W/m2) to the seawater in the Mar Menor evaluated in the heat box model of this study together with the results from Rodríguez-Rodríguez and Moreno-Ostos (2006) (RR06) and Martinez-Alvarez et al (2011) (MA11). The results show the mean monthly values (and S.D. or standard deviation) for the 281 months of the time series starting January, 2002. The long term average for each month is shown together with the long term annual average for each source or sink. The Bowen ratio (BR) is also shown. The overall annual average heat loss of 0.67 W/m2 in this estimate is within the error margin and so it may be assumed to define in a thermal balance. The mean warming of 0.43oC/decade of the Mar Menor (Table 1) equates to a long-term average heat input of 0.024 W/m2 (using Q = ρCphΦt) which is far too small to be detected within the simple model presented.

Table 3.

The estimated sources and sinks of heat (W/m2) to the seawater in the Mar Menor evaluated in the heat box model of this study together with the results from Rodríguez-Rodríguez and Moreno-Ostos (2006) (RR06) and Martinez-Alvarez et al (2011) (MA11). The results show the mean monthly values (and S.D. or standard deviation) for the 281 months of the time series starting January, 2002. The long term average for each month is shown together with the long term annual average for each source or sink. The Bowen ratio (BR) is also shown. The overall annual average heat loss of 0.67 W/m2 in this estimate is within the error margin and so it may be assumed to define in a thermal balance. The mean warming of 0.43oC/decade of the Mar Menor (Table 1) equates to a long-term average heat input of 0.024 W/m2 (using Q = ρCphΦt) which is far too small to be detected within the simple model presented.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).