1. Introduction

Basal stem rot (BSR), caused by

Ganoderma boninense, is a fungal disease of major economic significance in palm oil-producing countries, such as Malaysia and Indonesia. The progression of infection is difficult to detect because the symptoms of infection are only observable a few years after infection, depending on the age of the oil palm and the aggression level of

G. boninense [

1,

2]. Symptoms of BSR disease include canopy mottling, unopened spears, and the presence of fruiting bodies on the lower part of the stem [

3]. The prevalence of basal stem rot caused by

G. boninense is most likely a result of monoculture practices in oil palm plantations. The plausible infection routes of

G. boninense include latent inoculum from primary infection, root contact, and spores. Root contact may be the primary route of infection, and monoculture practices in oil palm plantations increase the risk of BSR infection via secondary inoculum through infected residual pieces [

4,

5].

G. boninense is also known as white rot fungus that infects living oil palms by secreting ligninolytic and cellulolytic enzymes capable of degrading plant cell walls, leading to the breakdown of basal stem tissues and ultimately causing the collapse of the palm. As the fungus invades and damages the internal vascular tissues of the palm, the transportation of water and nutrients to the upper parts of the tree is disrupted, eventually leading to the death of the palm [

6,

7].

G. boninense infection is thought to occur in two phases: an initial biotrophic phase and a later necrotrophic phase. During the biotrophic phase, hyphae grow to surround the surface of the root and secrete pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) to trigger the plant immune response. After countering the oil palm’s defenses,

G. boninense secretes enzymes that lyse the cell wall and cause cell death, eventually leading to the degradation of tissues at the base of the plant [

8]. In general, losses caused by

G. boninense can be direct or indirect; direct loss refers to the death of the oil palm, whereas indirect loss can be a decrease in fresh fruit bunch, fruit weight, and quality [

3,

9]. Apart from that,

G. boninense is a soil-borne fungus with multiple persistent survival structures including resistant mycelium, basidiospores, chlamydospores, and pseudosclerotia that complicate the disease eradication [

10]. Several management strategies such as soil mounding, surgical removal of infected tissues, and the use of chemical fungicides have been employed to control the disease. However, the effectiveness of these approaches is limited, often providing only temporary suppression, and their application is further constrained by cost considerations and environmental concerns [

7,

11]. Consequently, recent research has increasingly shifted towards environmentally sustainable strategies, particularly biological control approaches for managing BSR disease.

Today’s agricultural practices are driven by the need for more environmental-friendly and sustainable approaches, including the use of biofertilizers. Biofertilizers are formulations that incorporate living microorganisms, generally isolated from plant roots or rhizosphere soil, that establish symbiotic relationships with the host plant. These beneficial microbes enhance plant growth and productivity by facilitating nutrient acquisition and biodegradation, such as nitrogen fixation, phosphate and potassium solubilization, production of growth-promoting phytohormones, sequestration of vital nutrients and suppression of soil-borne pathogens, thereby reducing the reliance on chemical fertilizers and pesticides [

12,

13].

Generally, the composition of microbial inoculants in biofertilizers determines their overall effectiveness. In many cases, individual microbial strains within biofertilizer formulations exhibit multiple plant-beneficial functions. Beyond nitrogen fixation and phosphate solubilization, these microorganisms may also produce phytohormones, mobilize micronutrients such as zinc and iron, or secrete antimicrobial compounds that inhibit phytopathogens [

14]. The presence of such multifunctional traits highlights the importance of microbial composition in determining biofertilizer efficacy and suggests that synergistic interactions among these traits can significantly enhance plant growth and stress tolerance [

15]. This type of multifunctional microbe underscores the potential of biofertilizers as environmentally sustainable tools for improving crop productivity while concurrently providing biocontrol advantages.

Microorganisms in biofertilizers enhance plants growth by increasing the availability of macro- and micronutrients. Several members of genera

Azotobacter and

Rhizobium contribute to soil fertility through biological nitrogen fixation, converting atmospheric nitrogen (N₂), which plants cannot directly utilize, into ammonia that readily taken up by plants. In addition, certain plant-associated bacteria produce the enzyme ACC deaminase, an enzyme that mitigates stress-induced ethylene production. ACC deaminase producers, such as

Burkholderia cepacia and

Bacillus aryabhattai, degrade ACC, the immediate precursor of ethylene—thereby reducing ethylene levels that would otherwise inhibit root elongation and overall plant growth. Together, these microbes support plant nutrition and resilience under stress. Together, nitrogen-fixing microbes and ACC deaminase producers play complementary roles: one enhances nutrient availability, while the other mitigates stress responses, collectively promoting healthier plants. Potassium solubilization, phosphate solubilization, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), ACC deaminase, and siderophore production are instances of nutrient acquisition processes [

16].

Common groups of microorganisms employed in biofertilizers are plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB), free-living bacteria, and fungi [

15]. Biofertilizers are formulated based on their ability to confer benefits to plants, survivability for field application, and antagonistic activity. It is also crucial to ensure microorganisms in the biofertilizer do not antagonize the host or other microorganisms present in the consortium [

17]. Biofertilizers may possess multiple functions; fundamentally, they should supply nutrients to the plants and inhibit plant pathogens.

Streptomyces spp. and

Bacillus spp. have been reported to produce antibiotics and thrive in the rhizosphere. These traits provide significant advantages for biological agents used in biofertilizers. Most microorganisms that can combat plant pathogens engage in one or more of the following mechanisms: parasitism, competition for nutrients or space, antibiosis, inducing resistance, and promoting host growth [

18].

In addition to plant growth-enhancing properties, microorganisms with protective properties have also been explored for inclusion in biofertilizers. PGPB can also protect against phytopathogenic infections. PGPB suppress pathogens through direct antagonism by producing antimicrobial compounds, such as antibiotics, lipopeptides, and hydrolytic enzymes that degrade fungal cell walls. Some PGPB also release volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that inhibit pathogen growth, offering an eco-friendly alternative to chemical pesticides [

18,

19].

Many recent studies have also focused on the VOCs released by soil bacteria. VOCs were first identified as signaling compounds among bacteria, or between the host and bacteria. Nevertheless, several studies have reported that aerobically and anaerobically generated VOCs influence the microbial community, inhibit fungal spore germination, strengthen plant host resistance, and promote growth [

20]. An example of a VOC, nonan-2-one, can promote growth of rice plant whereas VOCs such as benzaldehyde, ketone, tetradecane, and 3-methylbutyric acid released by

Bacillus spp. can antagonize a wide range of phytopathogen that causes diseases in various plants and post-harvest crops [

21,

22].

PGPB also acts through competition for nutrients and space, rapidly colonizing roots, and limiting pathogen access to essential resources such as iron. Many strains produce siderophores that chelate iron, depriving pathogens of crucial nutrients [

23]. Additionally, biofilm formation by PGPB physically blocks the establishment of pathogens [

18]. Beyond pathogen suppression, PGPB enhance plant growth and trigger induced systemic resistance (ISR). They produce phytohormones such as IAA for root development and exhibit ACC deaminase activity to reduce stress-related ethylene levels. Some strains activate plant defense pathways, priming crops for stronger resistance to pathogens [

24].

This study aimed to isolate and characterize bacterial strains from CRPO biofertilizer, with a focus on strains exhibiting antagonistic activity against Ganoderma boninense and possessing PGP traits. Two isolates demonstrating the strongest anti-Ganoderma effects and PGP capabilities were selected for further analysis. These isolates were subsequently identified through 16S rRNA gene sequencing to evaluate their potential contribution to sustainable oil palm cultivation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Isolation of Bacteria from CRPO Biofertilizer

CRPO is a semi-organic biofertilizer developed and produced by INO-Nature Sdn Bhd, has been reported to reduce the incidence of BSR in various local oil palm plantations, a devastating disease caused by

Ganoderma spp. [

35]. The formulation of CRPO combines beneficial microorganisms and organic nutrients, which are thought to enhance plant growth and simultaneously suppress pathogenic fungi, offering an environmentally friendly approach to disease management in oil palm cultivations. Understanding the microbial composition of CRPO is essential, as the beneficial effects of biofertilizers are largely attributed to the diverse bacteria they contain.

In this study, multiple culture media were used to recover bacteria from the CRPO biofertilizer, as soil-associated microbes differ widely in their nutritional requirements and physiological traits. Reliance on a single medium would bias the recovery toward fast-growing or readily culturable species while overlooking slow-growing, nutrient-specialized, oligotrophic, or stress-tolerant bacteria. By employing eight media with varying carbon sources, nutrient levels, and selective properties (

Section 2.1), a broader and more representative fraction of the bacterial community of the biofertilizer could be isolated.

For example, the application of commercial soil extract agar that is nutrient-limited, and the manually prepared oil palm rhizosphere soil extract agar, simulate the native soil environment of oil palm plantations and therefore favor oligotrophic bacteria that may not grow on richer media, such as malt extract agar or yeast glycerol agar. Conversely, starch casein agar, streptomycin agar, and malt extract agar selectively encourage the growth of actinomycetes and heterotrophic bacteria.

Overall, the use of diverse media in the current study enhanced the likelihood of isolating morphologically and functionally distinct bacterial strains, including those with antagonistic capabilities against

G. boninense or potential plant growth–promoting, as well as rare species that would not appear on standard media alone. In this study, approximately 90% of the recovered bacterial isolates were Gram-positive. This predominance is expected, as endospore-forming bacteria, particularly members of the Firmicutes such as genera

Bacillus,

Margalitia, and

Lysinibacillus are well-adapted to survive desiccation, abiotic stress and nutrient limitation [

36,

37,

38]. Because most commercial biofertilizers, including the CRPO formulation, are produced and stored in dried pellet forms, non-sporulating bacteria are far less likely to remain viable throughout processing, drying and storage [

17]. Consequently, the isolation of primarily Gram-positive, endospore-forming taxa reflects both their intrinsic resilience and the selective pressures imposed by biofertilizer manufacturing.

4.2. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Taxonomic Identification

To date, no curative or highly effective treatment is available for BSR disease in oil palms once being infected by G. boninense, the most aggressive species among the members of genus Ganoderma. Therefore, biofertilizers have recently emerged as environmentally friendly alternatives to conventional chemical pesticides. In this study, bacteria were isolated and characterized from the CRPO biofertilizer, with emphasis on identifying those capable of inhibiting G. boninense and subsequently, further determine their potential PGP traits. Among the isolates recovered, two strains K3 and K8 exhibiting the strongest anti-Ganoderma activity from dual culture assay were selected for detailed evaluation. Given the pressing demand for biocontrol agents to mitigate BSR disease besides improving the yield of palm oil productivity, identifying these high-performing isolates is critical for understanding their functional roles within the formulation.

Sequencing the 16S rRNA genes provided reliable species-level identification on bacteria, enabling a clearer understanding of their antagonistic and PGP capabilities and their potential contributions to the overall efficacy of CRPO. As summarized in

Table 3, isolate K3 was identified as

M. shackletonii with high sequence identity of 99.5%. It is a spore-forming, Gram-positive bacterium known for its ability to inhabit extreme or nutrient-limited environments [

40,

41]. Its identification aligns with the observed physiological traits in this study, including phosphate and potassium solubilization, nitrogen fixation, ACC deaminase activity, siderophore and substantial IAA production—traits also noted in our previous work on another foliar fertilizer [

42].

M. shackletonii, formerly classified as

Bacillus shackletonii, was originally described in 2004 from a volcanic soil sample collected on Candlemas Island in the sub-Antarctic region [

40], but subsequent phylogenomic analyses led to major taxonomic revisions within the

Bacillus genus. As part of this effort, Gupta et al. published a valid proposal in 2020 to reclassify several species into new genera, resulting in the reassignment of

Bacillus shackletonii to

M. shackletonii [

41]. This reclassification reflects a broader refinement of

Bacillus systematics to better align species with their evolutionary relationships. In this study, the ability of endospore-forming

M. shackletonii to withstand diverse environmental conditions, and to remain viable in dried pellet form after biofertilizer production, likely contribute to its strong performance in both anti-

Ganoderma and plant growth-promoting assays. These traits collectively support their suitability as a robust and reliable inoculant for biofertilizer formulations.

Isolate K8 was identified as

B. subtilis, a species widely recognized for its agricultural relevance and broad-spectrum plant growth–promoting abilities [

39,

43]. The high sequence identity (99.7%) obtained in this study supports its accurate classification. The identification of

B. subtilis, is consistent with its frequent recovery from soil and its well-documented role in promoting plant health and suppressing phytopathogens. Members of the

Bacillus genus are known for their capacity to produce extracellular enzymes, phytohormones, and antimicrobial compounds, as well as to induce systemic resistance in plants. For example,

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens is widely used in agriculture because it improves plant nutrient acquisition by solubilizing nitrogen, phosphate, potassium, and iron. This bacterium also promotes plant growth directly through the production of VOCs and phytohormones [

39].

Overall, the 16S rRNA–based identification confirms that the bacterial isolates recovered from CRPO biofertilizer include taxa with established functional relevance in agriculture. The presence of K3 and K8 provides further support for the biofertilizer’s potential to deliver plant growth-promoting and biocontrol benefits to combat detrimental BSR disease in palm oil production industry.

4.3. Bacterial Antagonistic Activities Against G. boninense

4.3.1. Dual Culture Assay

The antagonistic activity of the bacterial isolates against the phytopathogenic fungus was evaluated using both dual culture and VOC assays to differentiate contact-dependent and airborne or gaseous compounds inhibitory mechanisms. Together, these assays distinguish between contact- or diffusible-based inhibition and volatile-mediated suppression, providing complementary insights into the mechanisms underlying bacterial antifungal activity and supports a more accurate assessment of their biocontrol potential.

The strong antagonistic activity demonstrated by the bacterial isolates K3 and K8 against

G. boninense with PIRG values of 89.8% and 89.4%, respectively. These inhibition levels not only demonstrate strong antifungal activities but also exceed the performance of the positive control S89b, which achieved a PIRG of 73.2% (

Figure 2). The high PIRG values suggest that both isolates can produce effective antifungal metabolites and/or engaging in competitive interactions that inhibit the radial expansion of

G. boninense. Dual culture assay, typically reflects direct antagonism through multiple inhibitory mechanisms, including competition for nutrients and physical space (

Figure 2, panels A and B), secretion of volatile and diffusible antimicrobial compounds (

Figure 2, panel C) such as antibiotics, lipopeptides (e.g., iturin, fengycin), and siderophores, and the production of hydrolytic enzymes (e.g., chitinases and glucanases) capable of degrading fungal cell walls [

39,

44].

Physical interference with fungal hyphal expansion may also contribute to the observed suppression, a characteristic trait of the genus

Bacillus. Similar findings were reported by Teixeira et al. (2021), where

Bacillus velezensis strain CMRP 4490 inhibited the growth of

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and

Botrytis cinerea by up to 60% and enhanced soybean germination rates [

45]. Notably,

B. subtilis as a dominant bacterium in water hyacinth biofertilizer, not only suppresses the growth of phytopathogen but it also enhances plant growth by fixing nitrogen, solubilizing phosphate and potassium, and secreting plant growth hormone IAA [

46].

The superior performance of K3 and K8 relative to S89b implies that these isolates may produce a broader or more potent spectrum of inhibitory compounds than the known positive control strain. The strong fungal suppression by isolates K3 and K8, suggests enhanced antagonism through both physical interference by competing for nutrients and physical space, as well as the production of more potent inhibitory metabolites, in comparison to S89b. This antagonistic effect is further supported by the extensive and rapid expansion of the vertically streaked colonies of K3 and K8 observed in the dual culture assay. Such pronounced disruption of phytopathogen growth highlights their potential as effective biocontrol agents against persistently found soilborne pathogen G. boninense, crucial for early intervention in BSR of oil palm.

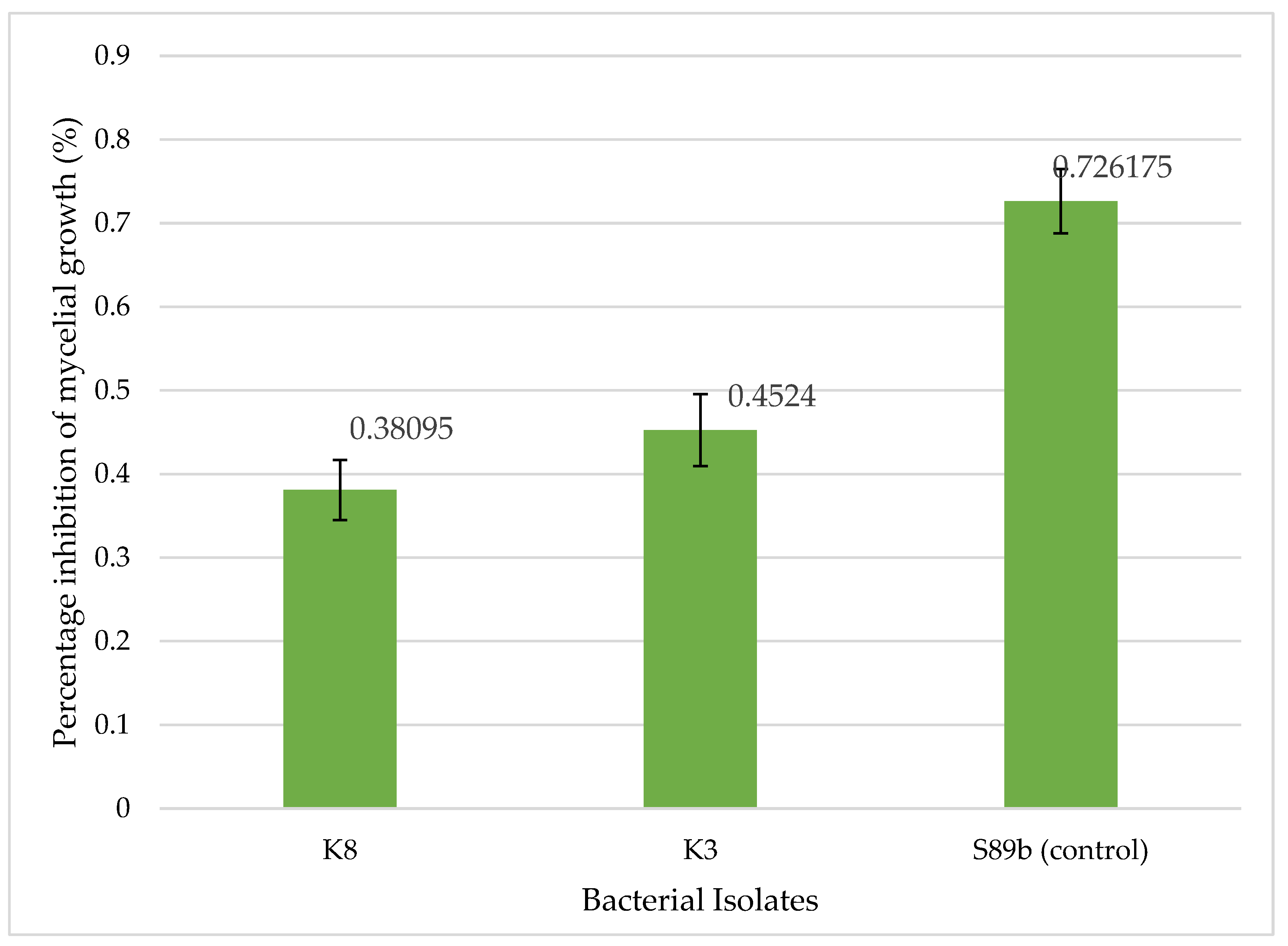

4.3.2. Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Assay

The role of bacterial VOC in fungal inhibition was assessed through the VOC assay. Both isolates, K3 and K8 demonstrated inhibitory activity, confirming that volatile metabolites contribute to the suppression of G. boninense. Their PIMG values of 45.2% and 38.1%, respectively, placing both within the category of moderate inhibitors of G. boninense. Notably, K3 exhibited stronger inhibitory potential compared to K8, positioning it as the more effective VOC producer, although both isolates remain classified as moderate inhibitors.

Relatively to isolates K3 and K8, the positive control S89b showed a notably higher PIMG of 72.6%, suggesting that its VOC production is a major contributor to its strong antifungal activity and aligns closely with its strong direct antagonism observed in the dual culture assay (PIRG of 73.2%). Because VOC assay excludes physical contact and diffusible metabolites, the observed inhibition can be attributed solely to low molecular weight gaseous compounds. Such volatiles may include acetoin, 2,3-butanediol, dimethyl disulfide, hydrogen cyanide, and various alcohols and ketones, which are known to interfere with fungal growth and physiology [

21]. For instance, VOCs produced by

B. subtilis CF-3 have been reported to inhibit the growth of

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, the pathogenic fungus responsible for anthracnose in litchi plants, which manifests as dark, sunken lesions on leaves, stems, and fruits [

47]. Beyond suppressing phytopathogens, another study highlights

Bacillus pseudomycoides, which generates diverse VOCs such as ethyl ether, benzene, and 1-dodecanol, thereby enhancing drought tolerance and promoting growth in wheat [

48].

Overall, the moderate VOC-mediated inhibition observed for K3 and K8 indicates that their antagonistic effects are driven mainly by diffusible metabolites or direct interaction mechanisms, as reflected by their stronger performance in the dual culture assay. Even so, their detectable VOC activity demonstrates that both isolates employ multiple modes of action, a trait advantageous in rhizosphere environments where physical contact with pathogens is inconsistent or spatially variable. Beyond direct inhibition, their ability to colonize the rhizosphere soil efficiently may also promote competitive exclusion, limiting G. boninense establishment by reducing available nutrients and space. Thus, incorporating these isolates into CRPO biofertilizer formulations designed for oil palm may help foster a protective microbial community that contributes to BSR management. Collectively, these findings emphasize the value of selecting bacterial strains with diverse and complementary functional traits to enhance the effectiveness and resilience of biofertilizer-based disease suppression strategies.

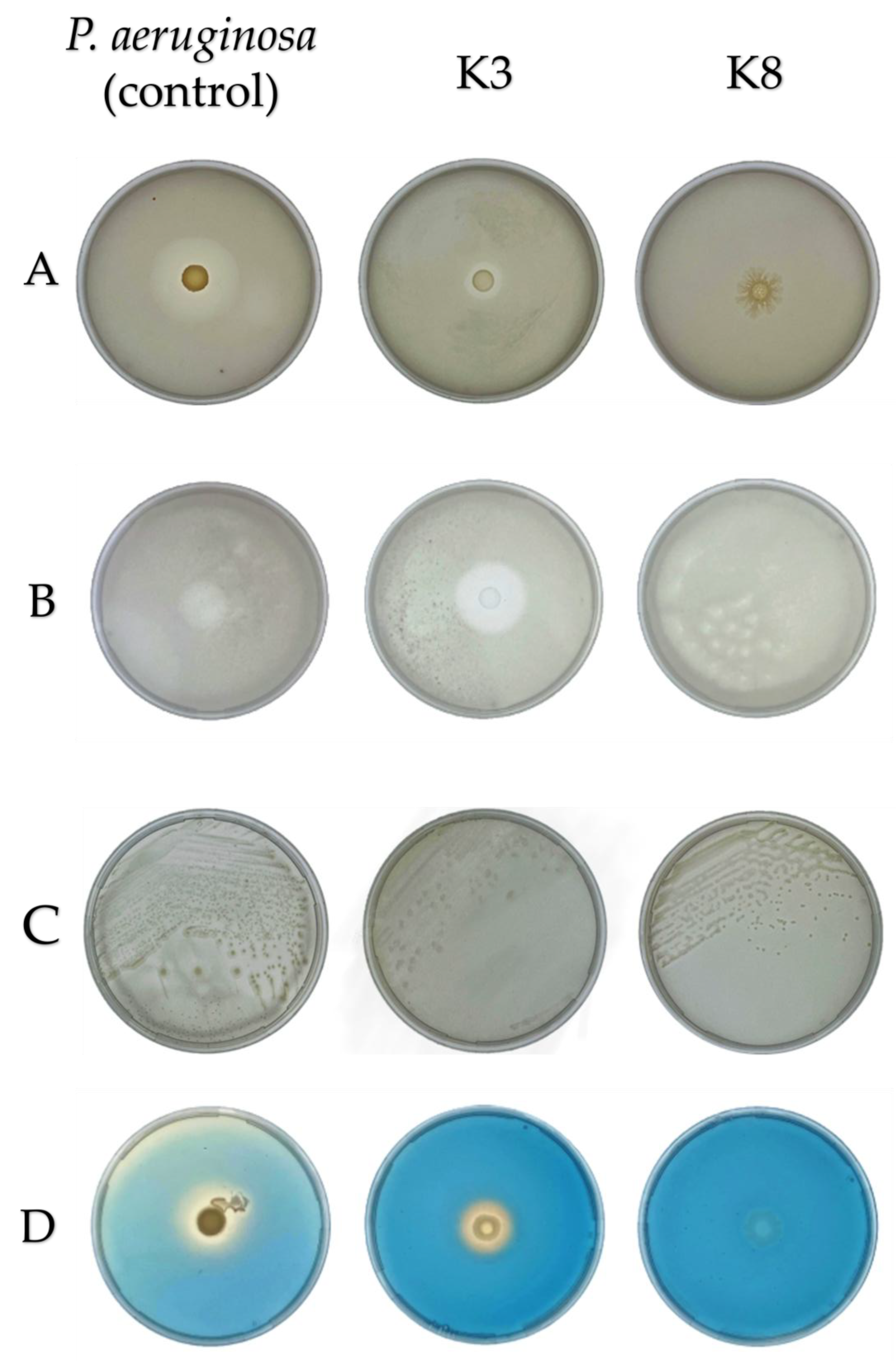

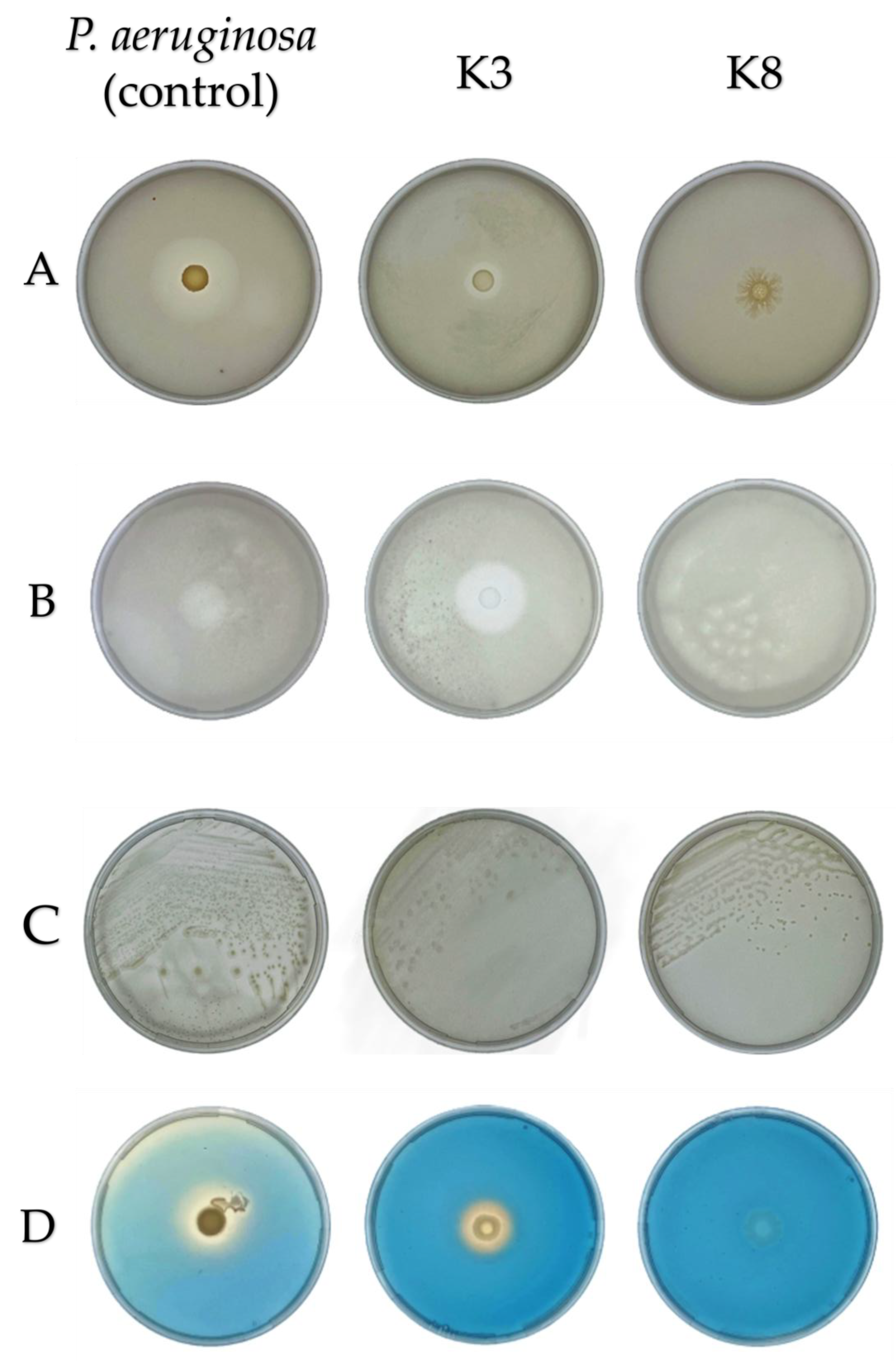

4.4. Functional Characterization of K3 (M. shackletonii) and K8 (B. subtilis) PGP Traits

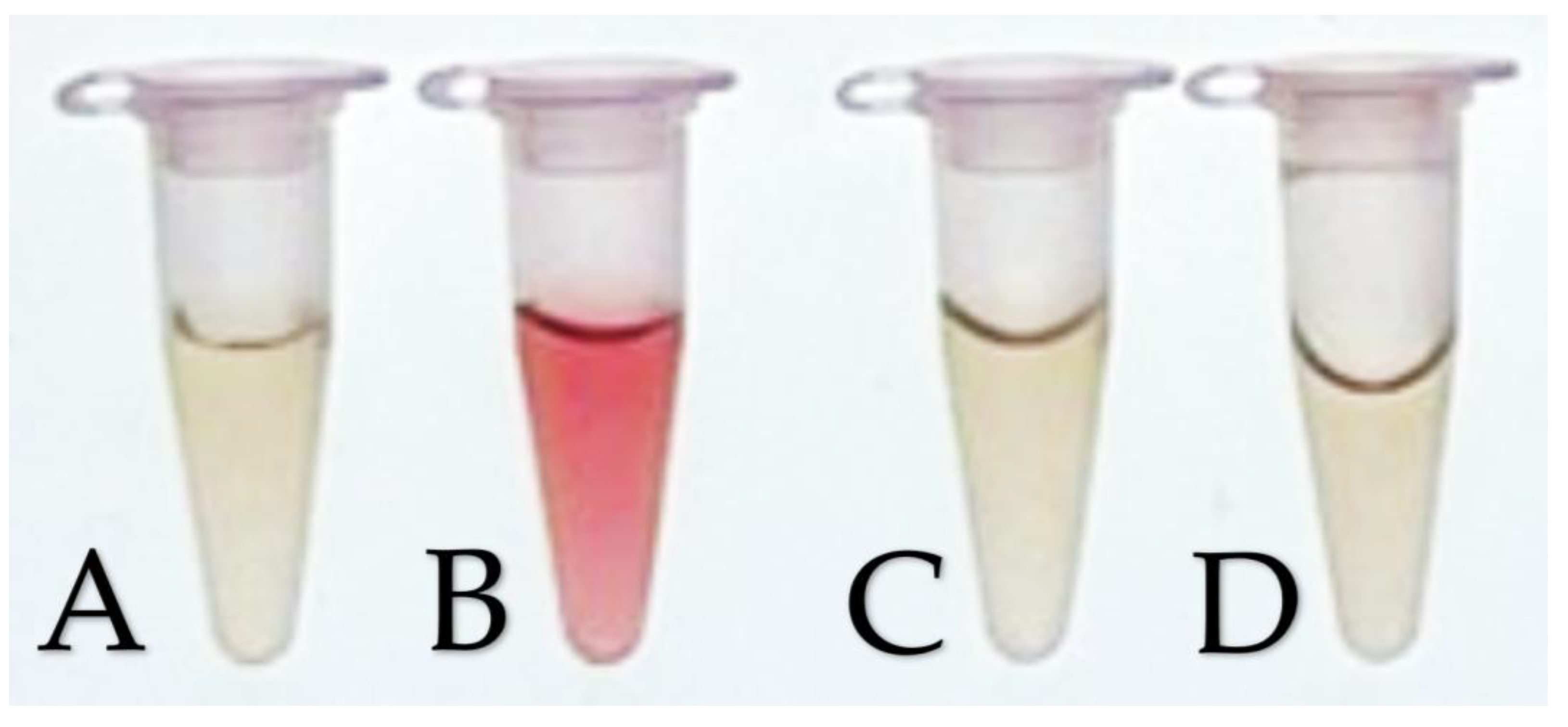

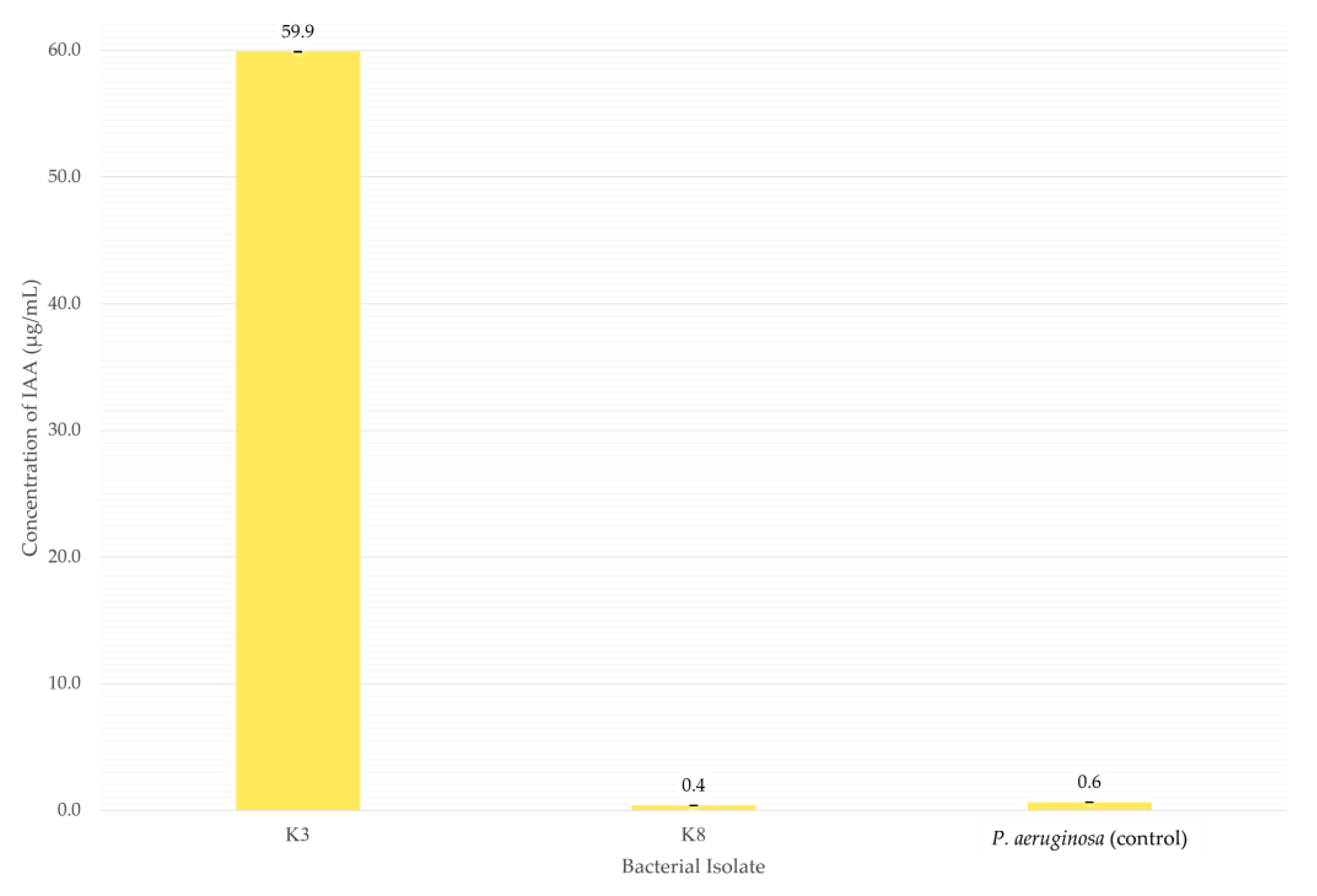

To evaluate the growth-promoting potential of the bacterial isolates, six functional assays were conducted: phosphate solubilization, potassium solubilization, nitrogen fixation, siderophore production, ACC deaminase activity, and IAA production. All six assays yielded positive results for isolate K3 , indicating a broad spectrum of PGP traits and a comprehensive suite of functions commonly associated with enhanced plant growth, performance, and resilience. The ability of M. shackletonii to solubilize both phosphate and potassium suggests a strong capacity to mobilize essential nutrients in the rhizosphere, thereby increasing their bioavailability to oil palm roots. Positive nitrogen fixation further enhances its contribution to nutrient enrichment, while siderophore production may facilitate improved iron acquisition under limiting conditions and indirectly inhibit competing soil pathogens.

Notably, M. shackletonii expressed strong IAA production, a key hormone involved in root initiation and elongation. This trait is consistent with improved seedling vigor and greater root surface area, which may in turn enhance nutrient uptake efficiency. The presence of high ACC deaminase, an enzyme that lowers plant ethylene levels under stress, further supports a role for K3 in stress alleviation and improved root growth under adverse soil conditions.

Previous studies have reported that

M. shackletonii possesses PGP abilities such as siderophore production, IAA synthesis, ACC deaminase activity, and phosphate solubilization [

40], which are consistent with our findings for K3. Interestingly,

Bacillus pinisoli, isolated from decaying pine trees, has been identified as a closely related species to

M. shackletonii (96.7% similarity); however, its antagonistic properties and plant-beneficial traits remain largely unexplored [

49]. Thus, while phylogenetic relatedness suggests a close evolutionary link, the functional characterization results highlight

M. shackletonii as a more promising bacterium for biocontrol and plant growth promotion in agricultural systems.

Isolate K8 although more limited in its functional profile, showed positive results for nitrogen fixation and ACC deaminase activity. These traits may contribute to moderate growth promotion and stress mitigation, even in the absence of phosphate or potassium solubilization and IAA production. Consequently, B. subtilis may serve a complementary role within the bacterial consortia of CRPO, enhancing nitrogen availability and alleviating ethylene-mediated stress responses.

The functional broadness displayed by M. shackletonii, combined with its taxonomic identification as, suggests that this species could be one of the key contributors to biofertilizer’s reported field performance. Meanwhile, the more specialized traits of K8 reflect known mechanisms through which Bacillus spp. support plant health, including stress mitigation via ACC deaminase. The inclusion of soil bacterium P. aeruginosa as a control, validates the assay conditions were appropriate and that the observed bacterial activities were biologically meaningful.

Overall, these findings highlight that CRPO biofertilizer contains bacterial taxa with diverse and complementary PGP activities, together with the collection of bacteria isolates recovered from the formulation, likely act synergistically to enhance nutrient availability, promote root development, and improve plant stress tolerance. Such integrated functional interactions may contribute to its ability to support healthier oil palm growth and indirectly reduce susceptibility to BSR in field applications.

Oil palm requires exceptionally high nutrient inputs compared to most tropical crops, and its increasingly cultivation on low-fertility soils makes fertilizer management indispensable. Because substantial amounts of nutrients are removed in harvested bunches and stored in roots, trunks, and fronds, fertilizer regimes must balance these demands with nutrients recycled from crop residues such as empty fruit bunches and palm oil mill effluent [

50]. In this context, biofertilizers provide a sustainable alternative by enhancing nutrient availability, improving soil fertility, and reducing reliance on synthetic inputs of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, thereby supporting both productivity and long-term sustainability of oil palm plantations. Importantly, their application also mitigates environmental impacts by minimizing chemical runoff, lowering greenhouse gas emissions, and promoting healthier soil ecosystems.

Figure 1.

Colony morphology of bacterial isolates on Luria Bertani (LB) agar after incubation at 28 °C for 48 h. (A) K3 (M. shackletonii), (B) K8 (B. subtilis), and (C) B. anthina S89b (control).

Figure 1.

Colony morphology of bacterial isolates on Luria Bertani (LB) agar after incubation at 28 °C for 48 h. (A) K3 (M. shackletonii), (B) K8 (B. subtilis), and (C) B. anthina S89b (control).

Figure 2.

Dual culture assay of bacterial isolates against Ganoderma boninense. Growth of bacterial isolates and alongside G. boninense on nutrient agar (NA) plates after incubation at 28 °C for seven days. A 5-day-old G. boninense plug was placed at the center of the LB plate. Each of the bacterial isolate was streaked 3 cm away from the fungal plug. (A) K3 (M. shackletonii), (B) K8 (B. subtilis), (C) S89b (control), and (D) G. boninense alone. Inhibition of fungal growth by the bacterial isolates was evaluated in triplicate and quantified as the percentage inhibition of radial growth (PIRG).

Figure 2.

Dual culture assay of bacterial isolates against Ganoderma boninense. Growth of bacterial isolates and alongside G. boninense on nutrient agar (NA) plates after incubation at 28 °C for seven days. A 5-day-old G. boninense plug was placed at the center of the LB plate. Each of the bacterial isolate was streaked 3 cm away from the fungal plug. (A) K3 (M. shackletonii), (B) K8 (B. subtilis), (C) S89b (control), and (D) G. boninense alone. Inhibition of fungal growth by the bacterial isolates was evaluated in triplicate and quantified as the percentage inhibition of radial growth (PIRG).

Figure 3.

Percentage inhibition of radial growth (PIRG) of bacterial isolates against G. boninense obtained from the dual culture assay. Bars indicate the mean average of triplicate results of PIRG, and the error bars represent the standard deviations. K8 (B. subtilis) and K3 (M. shackletonii), exhibited strong antifungal activity, achieving PIRG values of 89.8% and 89.4%, respectively, which were higher than the positive control S89b (73.2%). In this study, PIRG values > 75.0% were classified as strong inhibitors of G. boninense in vitro.

Figure 3.

Percentage inhibition of radial growth (PIRG) of bacterial isolates against G. boninense obtained from the dual culture assay. Bars indicate the mean average of triplicate results of PIRG, and the error bars represent the standard deviations. K8 (B. subtilis) and K3 (M. shackletonii), exhibited strong antifungal activity, achieving PIRG values of 89.8% and 89.4%, respectively, which were higher than the positive control S89b (73.2%). In this study, PIRG values > 75.0% were classified as strong inhibitors of G. boninense in vitro.

Figure 4.

Antagonistic activity VOCs produced by bacterial isolates against Ganoderma boninense on LB agar. Bacterial isolates were grown in the lower compartment and a G. boninense plug was placed in the upper compartment of center-partitioned bi-plates, followed by an incubation at 28 °C for seven days. (A) K3 (M. shackletonii), (B) K8 (B. subtilis), and (C) S89b (positive control), and (D) G. boninense alone. Fungal growth was inhibited by VOCs produced by the bacterial isolates, assessed in triplicate and quantified as the percentage inhibition of mycelial growth (PIMG), reflecting the extent of VOC-mediated antifungal activity.

Figure 4.

Antagonistic activity VOCs produced by bacterial isolates against Ganoderma boninense on LB agar. Bacterial isolates were grown in the lower compartment and a G. boninense plug was placed in the upper compartment of center-partitioned bi-plates, followed by an incubation at 28 °C for seven days. (A) K3 (M. shackletonii), (B) K8 (B. subtilis), and (C) S89b (positive control), and (D) G. boninense alone. Fungal growth was inhibited by VOCs produced by the bacterial isolates, assessed in triplicate and quantified as the percentage inhibition of mycelial growth (PIMG), reflecting the extent of VOC-mediated antifungal activity.

Figure 5.

Percentage inhibition of mycelial growth (PIMG) of bacterial isolates against G. boninense obtained from the bi-plate VOC assay. Bars indicate the mean of triplicate PIMG values, and error bars represent standard deviations. Isolates K8 (B. subtilis) and K3 (M. shackletonii) exhibited moderate antifungal activity, achieving PIMG values of 38.1% and 45.2%, respectively, whereas the positive control S89b exhibited 72.6% PIMG value. In this study, bacterial isolates with PIMG values greater than 60.0% were classified as strong inhibitors of G. boninense in vitro by their ability to produce VOCs.

Figure 5.

Percentage inhibition of mycelial growth (PIMG) of bacterial isolates against G. boninense obtained from the bi-plate VOC assay. Bars indicate the mean of triplicate PIMG values, and error bars represent standard deviations. Isolates K8 (B. subtilis) and K3 (M. shackletonii) exhibited moderate antifungal activity, achieving PIMG values of 38.1% and 45.2%, respectively, whereas the positive control S89b exhibited 72.6% PIMG value. In this study, bacterial isolates with PIMG values greater than 60.0% were classified as strong inhibitors of G. boninense in vitro by their ability to produce VOCs.

Figure 6.

Plate assays for plant growth-promoting activities of bacterial isolates after incubation at 28 °C for seven days. The soil-derived P. aeruginosa (positive control), along with isolates K3 (M. shackletonii) and K8 (B. subtilis), arranged from left to right, were evaluated on (A) Pikovskaya’s agar, (B) Aleksandrov agar (C) Jensen nitrogen-free agar, and (D) Chrome Azurol S (CAS) agar, respectively. Clear zones surrounding colonies in panels (A) and (B) indicate phosphate and potassium solubilization, respectively. Colonies growth on panel (C), illustrates the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen. In panel (D), a yellow halo zone indicates siderophore production. K3 demonstrated broad PGP potential, showing positive activity for all four traits assessed, namely phosphate and potassium solubilization, nitrogen fixation, siderophore production. In contrast, K8 showed growth, only on Jensen’s nitrogen-free agar, thereby confirming its ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen but tested negative for the other traits tested.

Figure 6.

Plate assays for plant growth-promoting activities of bacterial isolates after incubation at 28 °C for seven days. The soil-derived P. aeruginosa (positive control), along with isolates K3 (M. shackletonii) and K8 (B. subtilis), arranged from left to right, were evaluated on (A) Pikovskaya’s agar, (B) Aleksandrov agar (C) Jensen nitrogen-free agar, and (D) Chrome Azurol S (CAS) agar, respectively. Clear zones surrounding colonies in panels (A) and (B) indicate phosphate and potassium solubilization, respectively. Colonies growth on panel (C), illustrates the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen. In panel (D), a yellow halo zone indicates siderophore production. K3 demonstrated broad PGP potential, showing positive activity for all four traits assessed, namely phosphate and potassium solubilization, nitrogen fixation, siderophore production. In contrast, K8 showed growth, only on Jensen’s nitrogen-free agar, thereby confirming its ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen but tested negative for the other traits tested.

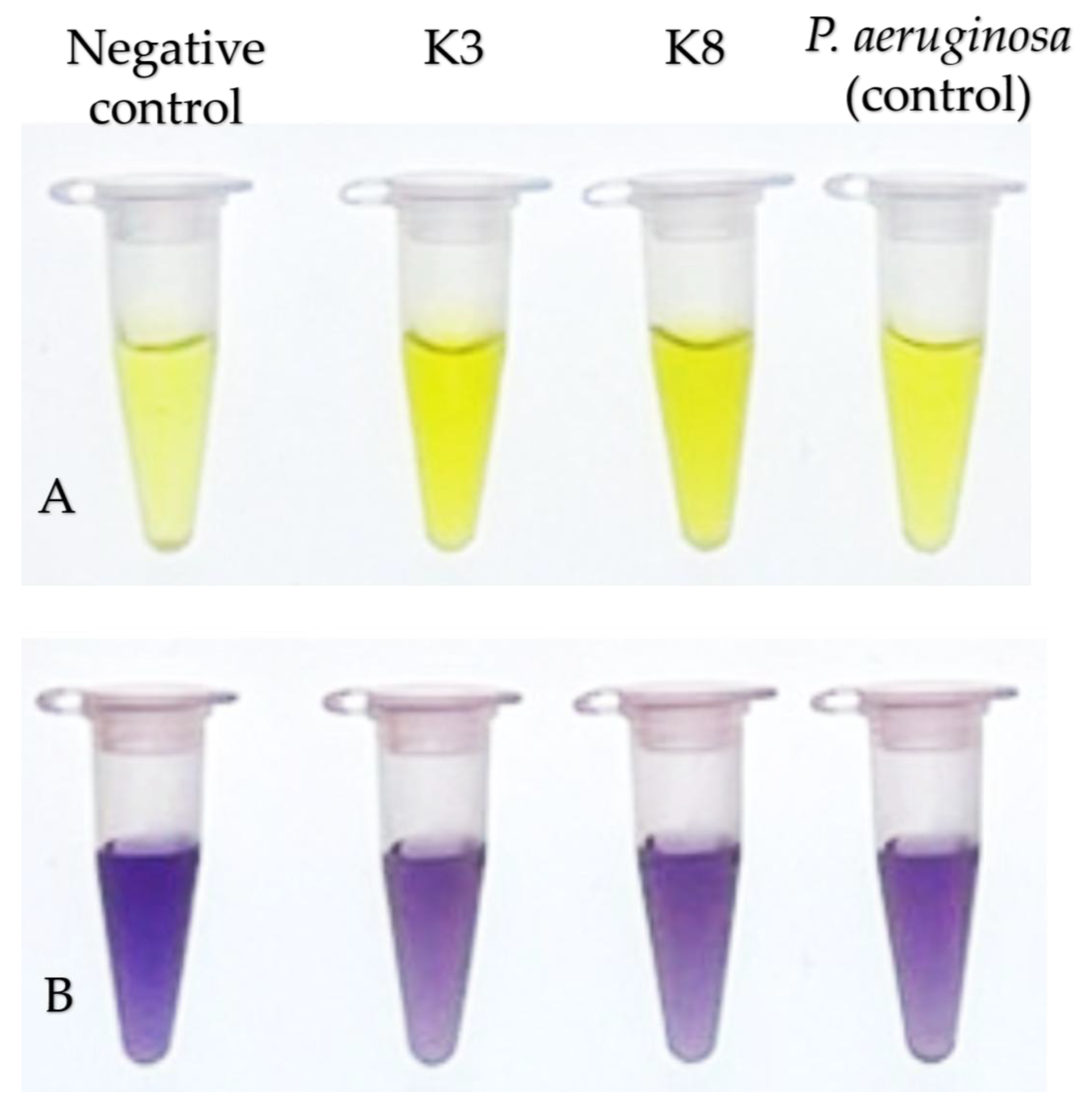

Figure 7.

Quantitative assay for IAA production by bacterial isolates. Colorimetric assays of (A) Negative control (0 µg/mL IAA), (B) K3 (M. shackletonii), (C) K8 (B. subtilis), and (D) P. aeruginosa (non-IAA producer) for the IAA production assay. IAA production was inferred from the intensity of the color shift from yellow to red measured at OD530 after incubation with Salkowski reagent. Stronger color development indicating higher IAA levels. Isolate K3 exhibited strong IAA production, whereas isolate K8 and P. aeruginosa are classified as non-IAA producers.

Figure 7.

Quantitative assay for IAA production by bacterial isolates. Colorimetric assays of (A) Negative control (0 µg/mL IAA), (B) K3 (M. shackletonii), (C) K8 (B. subtilis), and (D) P. aeruginosa (non-IAA producer) for the IAA production assay. IAA production was inferred from the intensity of the color shift from yellow to red measured at OD530 after incubation with Salkowski reagent. Stronger color development indicating higher IAA levels. Isolate K3 exhibited strong IAA production, whereas isolate K8 and P. aeruginosa are classified as non-IAA producers.

Figure 8.

Concentration of IAA produced by bacterial isolates in the medium after incubation at 28 °C for 48 h. Bars indicate the mean IAA concentrations from triplicate assays, and error bars represent standard deviations. K8 (B. subtilis) and P. aeruginosa used in this study produced < 1.0 µg/mL IAA, therefore they are classified as non-IAA producers.

Figure 8.

Concentration of IAA produced by bacterial isolates in the medium after incubation at 28 °C for 48 h. Bars indicate the mean IAA concentrations from triplicate assays, and error bars represent standard deviations. K8 (B. subtilis) and P. aeruginosa used in this study produced < 1.0 µg/mL IAA, therefore they are classified as non-IAA producers.

Figure 9.

Colorimetric assay of ACC deaminase production by bacterial isolates. Panels A and B show development of color before and after addition of ninhydrin reagent and heat treatment, respectively, for the negative control (3 mM ACC), K3 (M. shackletonii), K8 (B. subtilis) and P. aeruginosa (positive control). ACC deaminase activity was inferred from the intensity of purple color measured at OD570 after heating in the presence of ninhydrin. Stronger purple color indicates higher residual ACC concentration and therefore lower ACC deaminase activity. Both bacterial isolates produced ACC deaminase within the moderate category, with K3 as the highest ACC deaminase producer, among the three bacteria being tested.

Figure 9.

Colorimetric assay of ACC deaminase production by bacterial isolates. Panels A and B show development of color before and after addition of ninhydrin reagent and heat treatment, respectively, for the negative control (3 mM ACC), K3 (M. shackletonii), K8 (B. subtilis) and P. aeruginosa (positive control). ACC deaminase activity was inferred from the intensity of purple color measured at OD570 after heating in the presence of ninhydrin. Stronger purple color indicates higher residual ACC concentration and therefore lower ACC deaminase activity. Both bacterial isolates produced ACC deaminase within the moderate category, with K3 as the highest ACC deaminase producer, among the three bacteria being tested.

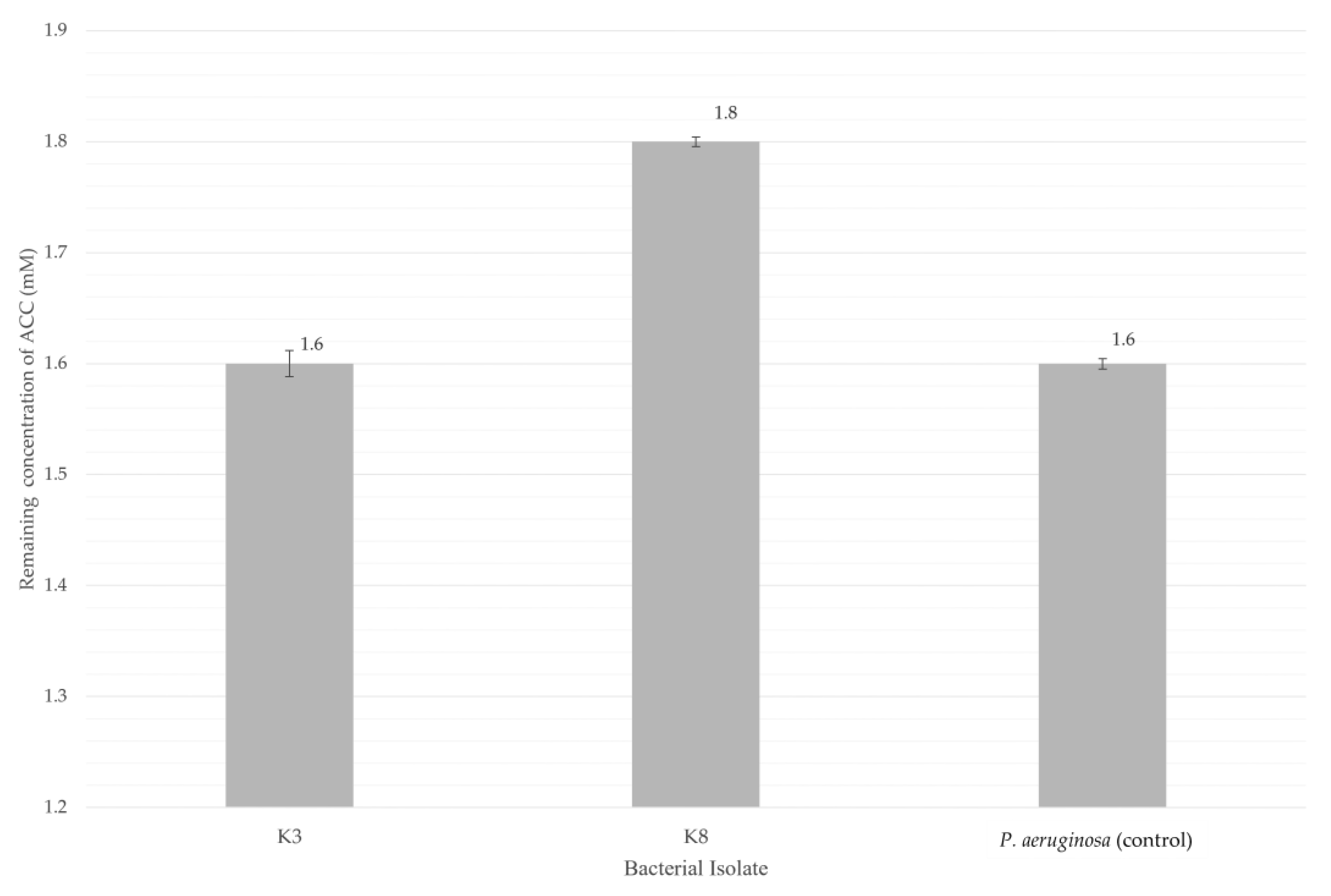

Figure 10.

Quantitative assay of ACC deaminase activity for various bacteria after incubation at 28 °C for 48 h. Bars indicate the average of triplicates of the remaining 1-amino-cyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC), and error bars represent standard deviations. The remaining ACC concentration in the medium decreased to approximately 1.6 mM for both isolate K3 (M. shackletonii) and positive control P. aeruginosa. Residual ACC levels in the medium were higher in isolate K8 (B. subtilis), about 1.8 mM, indicating comparatively lower ACC deaminase activity. In this study, bacterial isolates K3 and K8 displayed moderate production of ACC deaminase.

Figure 10.

Quantitative assay of ACC deaminase activity for various bacteria after incubation at 28 °C for 48 h. Bars indicate the average of triplicates of the remaining 1-amino-cyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC), and error bars represent standard deviations. The remaining ACC concentration in the medium decreased to approximately 1.6 mM for both isolate K3 (M. shackletonii) and positive control P. aeruginosa. Residual ACC levels in the medium were higher in isolate K8 (B. subtilis), about 1.8 mM, indicating comparatively lower ACC deaminase activity. In this study, bacterial isolates K3 and K8 displayed moderate production of ACC deaminase.

Table 1.

Summarized results of the morphological study of bacteria grown on LB agar.

Table 1.

Summarized results of the morphological study of bacteria grown on LB agar.

| Bacteria |

Colony Morphology |

| Gram staining |

Shape |

Surface |

Texture |

Color |

Elevation |

Margin |

| K3 |

Positive |

Bacillus |

Dry |

Rough |

White |

Raised |

Entire |

| K8 |

Positive |

Bacillus |

Dry |

Rough |

White |

Flat |

Undulate |

| S89b (control) |

Negative |

Bacillus |

Wet |

Smooth |

Yellow |

Raised |

Entire |

Table 2.

Summarized results of PGP activities of bacteria.

Table 2.

Summarized results of PGP activities of bacteria.

| Bacteria |

Plant Growth-Promoting Properties |

| Phosphate solubilization |

Potassium solubilization |

Nitrogen fixation |

Siderophore production |

IAA production |

ACC deaminase production |

| K3 |

Positive |

Positive |

Positive |

Positive |

+++ |

Positive |

| K8 |

Negative |

Negative |

Positive |

Negative |

- |

Positive |

| P. aeruginosa (control) |

Positive |

Positive |

Positive |

Positive |

- |

Positive |

Table 3.

Identity of bacterial isolates based on 16S rRNA sequencing results.

Table 3.

Identity of bacterial isolates based on 16S rRNA sequencing results.

| Isolate |

BLASTn identity |

Query length |

Query coverage (%) |

E-value |

Identity (%) |

Accession number |

| K3 |

Margalitia shackletonii |

1473 |

100.0% |

0.0 |

99.5 |

OQ552639.1 |

| K8 |

Bacillus subtilis |

1399 |

100.0% |

0.0 |

99.7 |

OP798061.1 |