Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

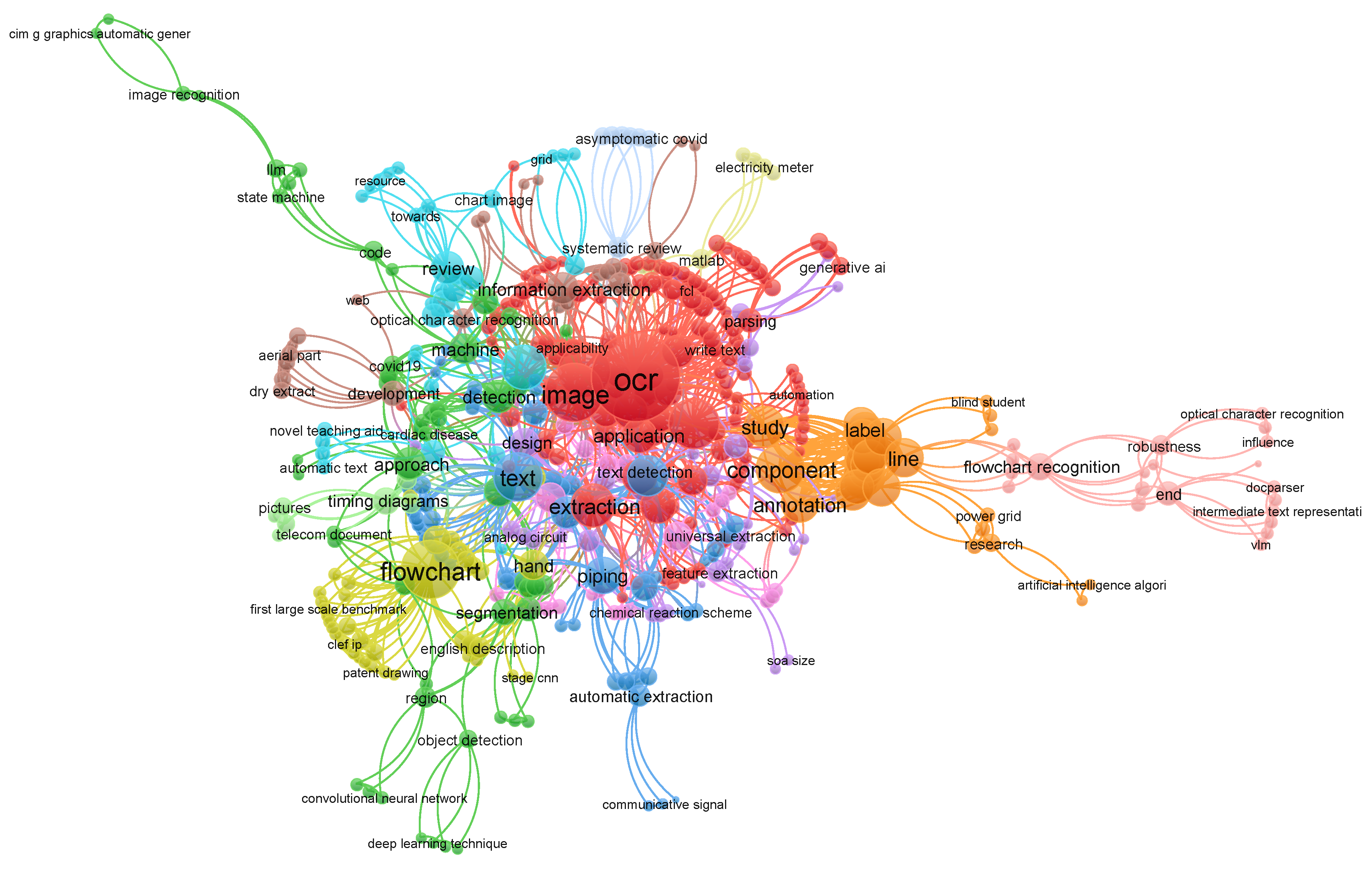

Keywords:

1. Introduction

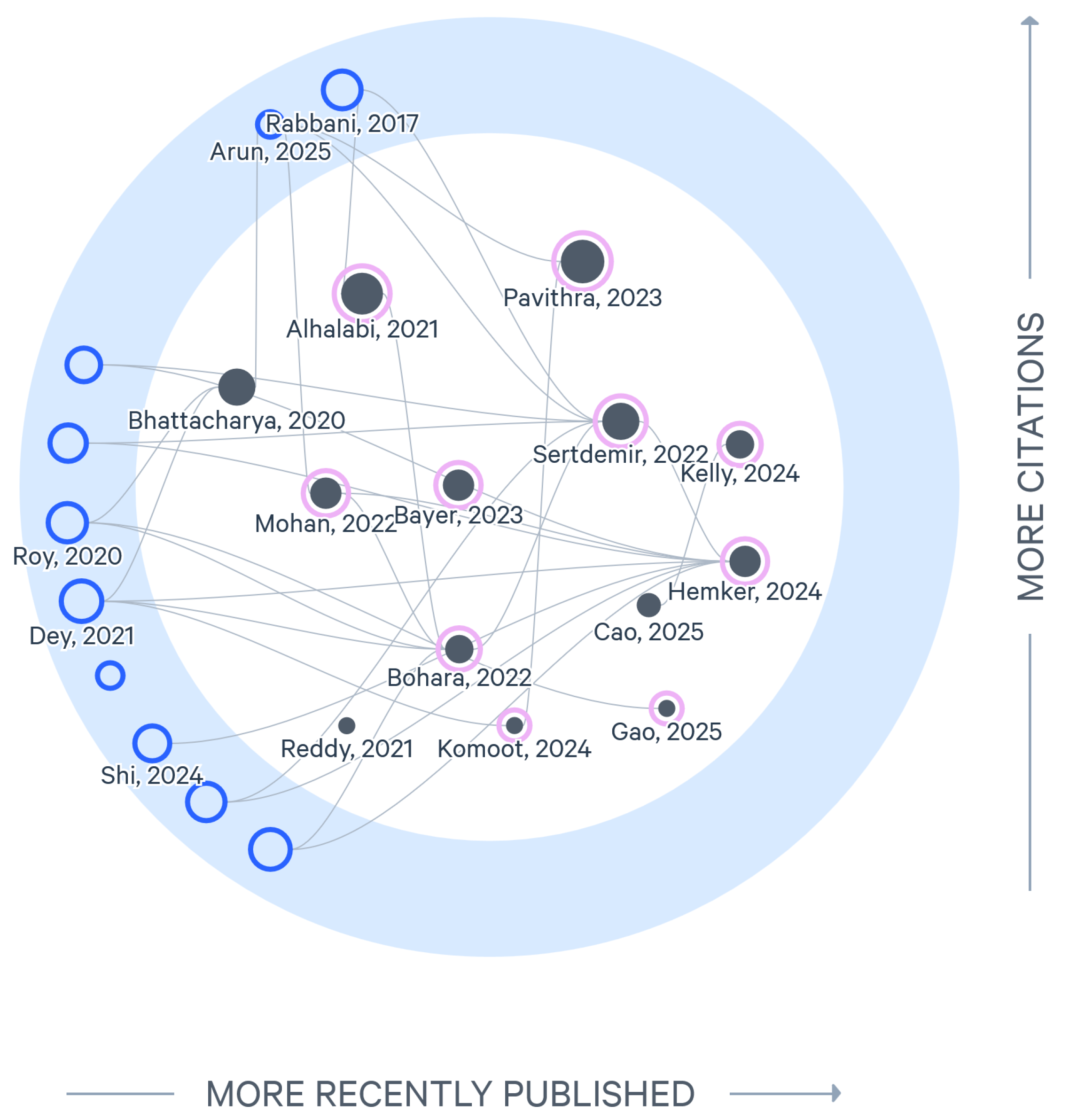

2. Survey Methodology

- IEEE Xplore,

- ACM Digital Library,

- SpringerLink,

- Elsevier,

- MDPI, and

- Google Scholar.

3. Background

3.1. Early Image Content Extraction Approaches

- Pre-Processing involves noise reduction, binarization, and skew correction to enhance image quality.

- Segmentation separates text regions from non-text elements, and individual characters or words are isolated.

- Feature Extraction identifies key characteristics of each symbol, such as edges, corners, and stroke widths.

- Classification and Recognition compares the features to already trained character models to output machine-readable text.

- Post-Processing is often utilized by modern OCR systems to correct recognition errors using language models.

- Edge Detection or Contour Extraction is utilized to identify shape boundaries.

- Shape Description computes area, perimeter, or moments.

- Feature Matching uses template matching or feature descriptor techniques.

- Classification maps the detected shapes to predefined categories.

- Convolutional layers apply a series of learnable filters or kernels that perform convolutional operations over the input image. These filters detect edges, textures, and color gradients.

- Pooling layers perform a down-sampling operation on the feature maps, reducing their spatial dimensions while retaining the significant information.

- Fully Connected (FC) layers operate after the feature maps are flattened into a one-dimensional feature vector. Flattening converts the multidimensional feature maps into a single continuous vector. These layers integrate the extracted features and compute the final prediction.

3.2. Existing Evaluation Approaches for Content Extraction Methods

4. Diagram Analysis

4.1. Analysis Overview

- inspiration, which covers the foundational ideas that influenced the study;

- techniques, where we explore specific methods and tools used in the research, along with their results; as well as

- future directions, which outline the areas the authors wish to enhance or explore further.

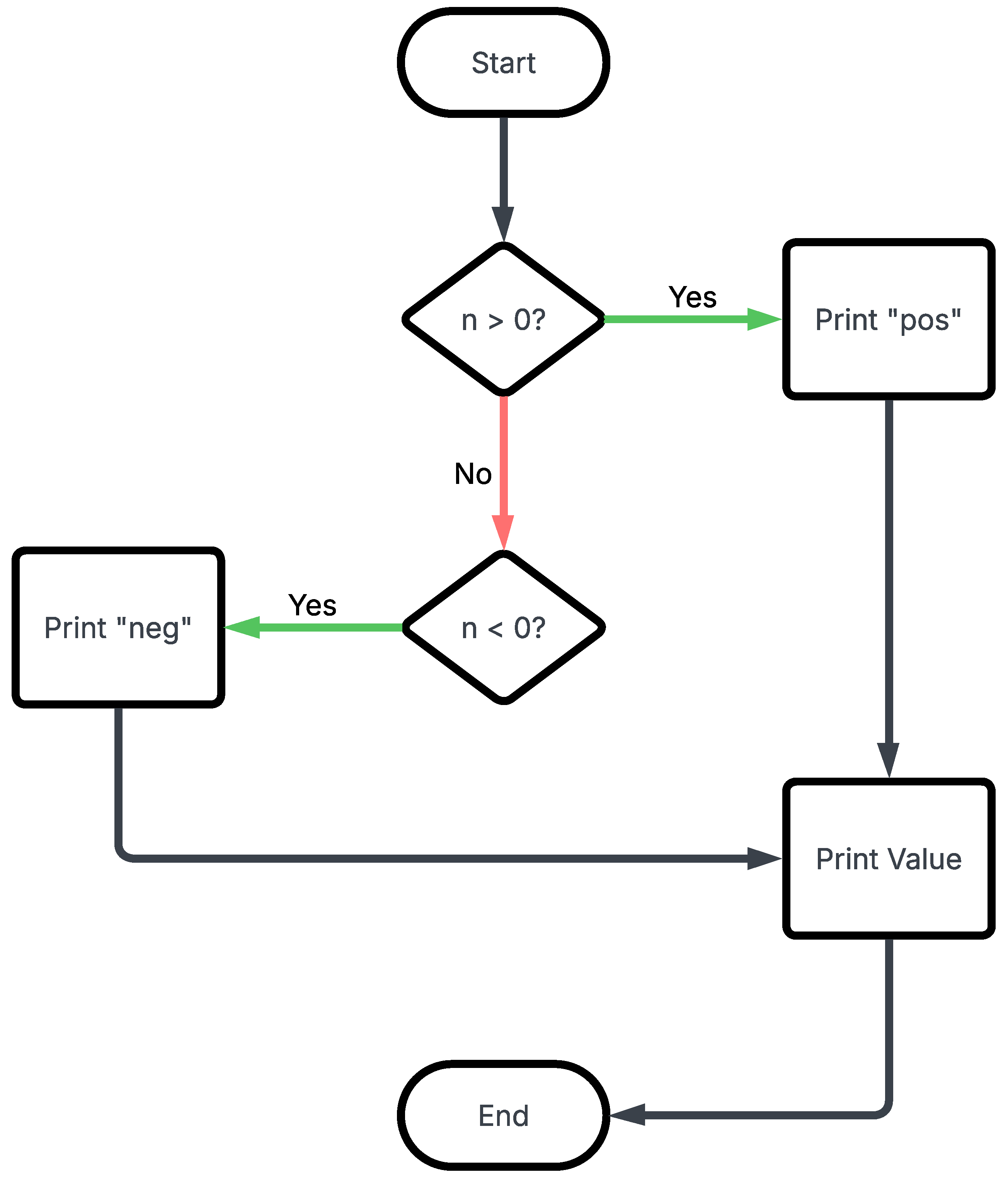

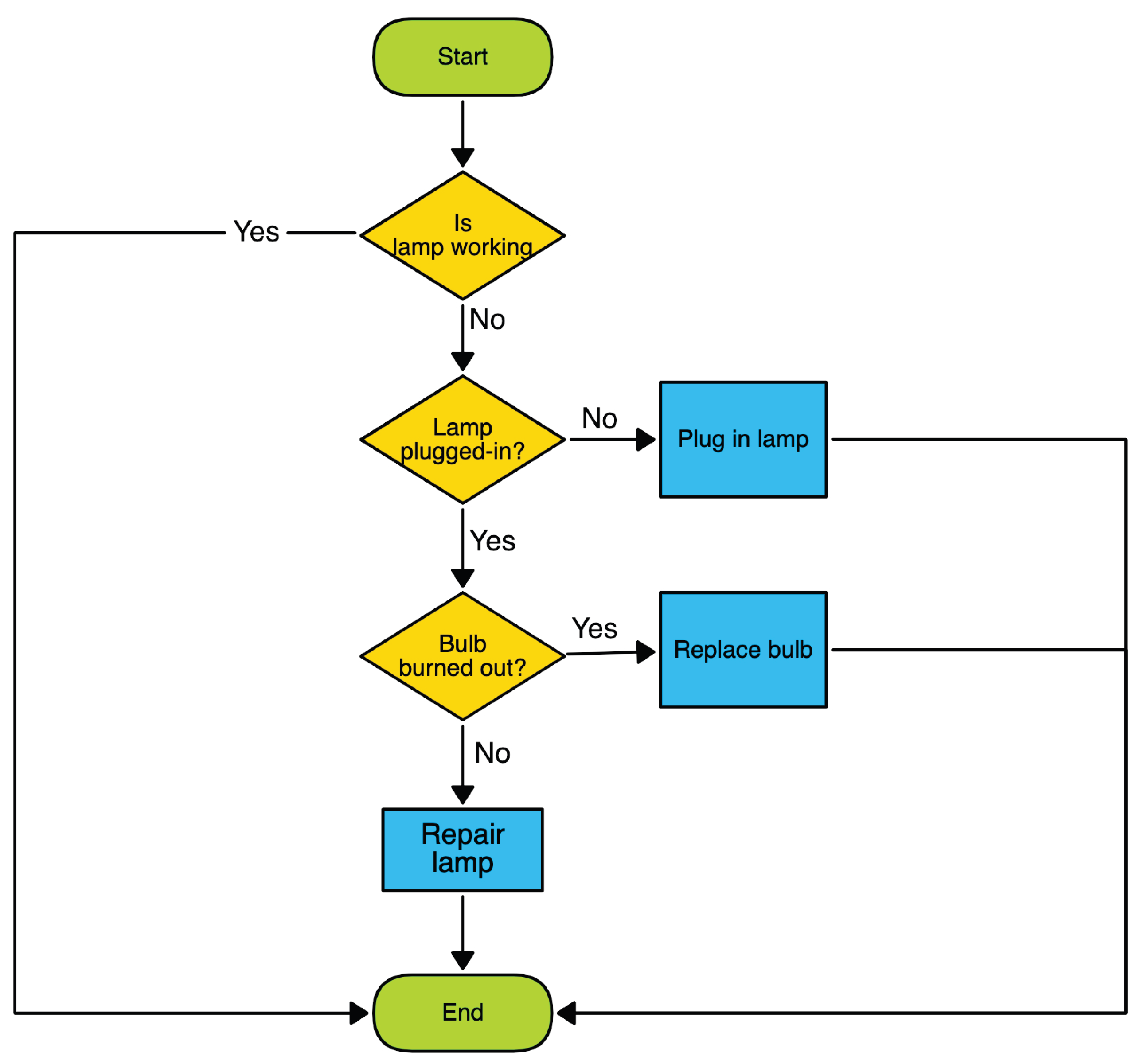

4.2. Flowchart Analysis

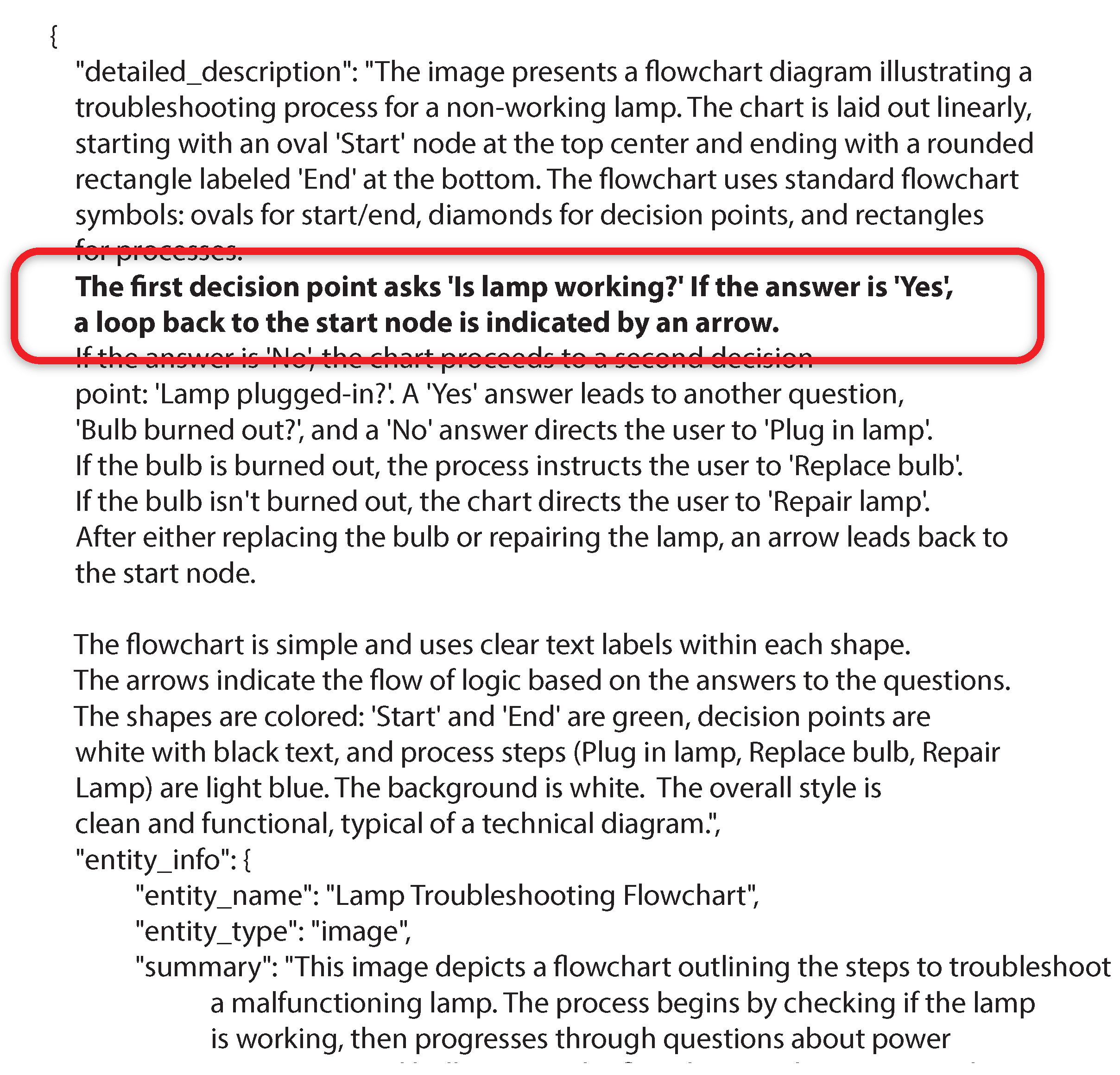

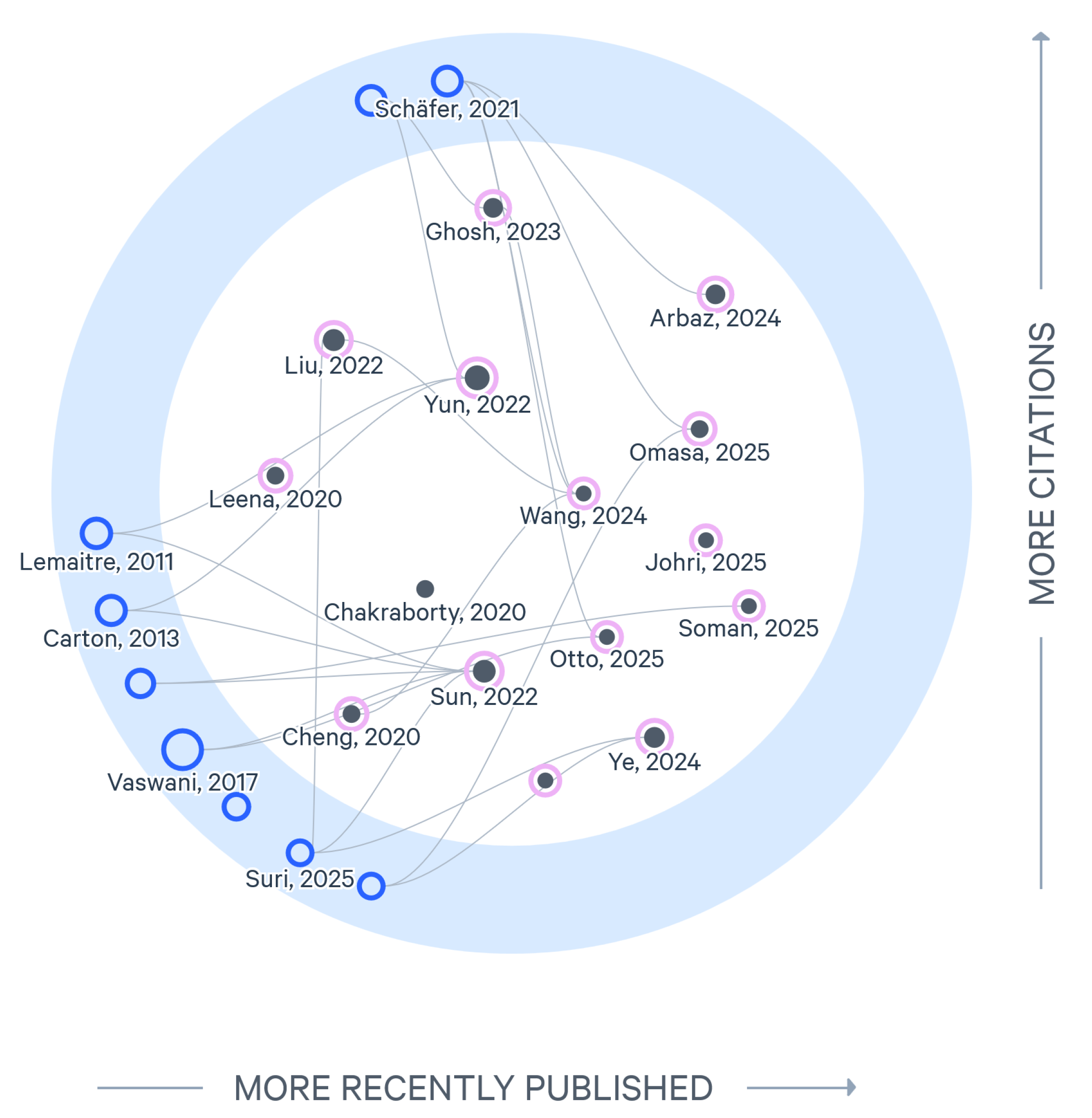

4.2.1. Review of Identified Papers

4.2.2. Flowchart Review Summary

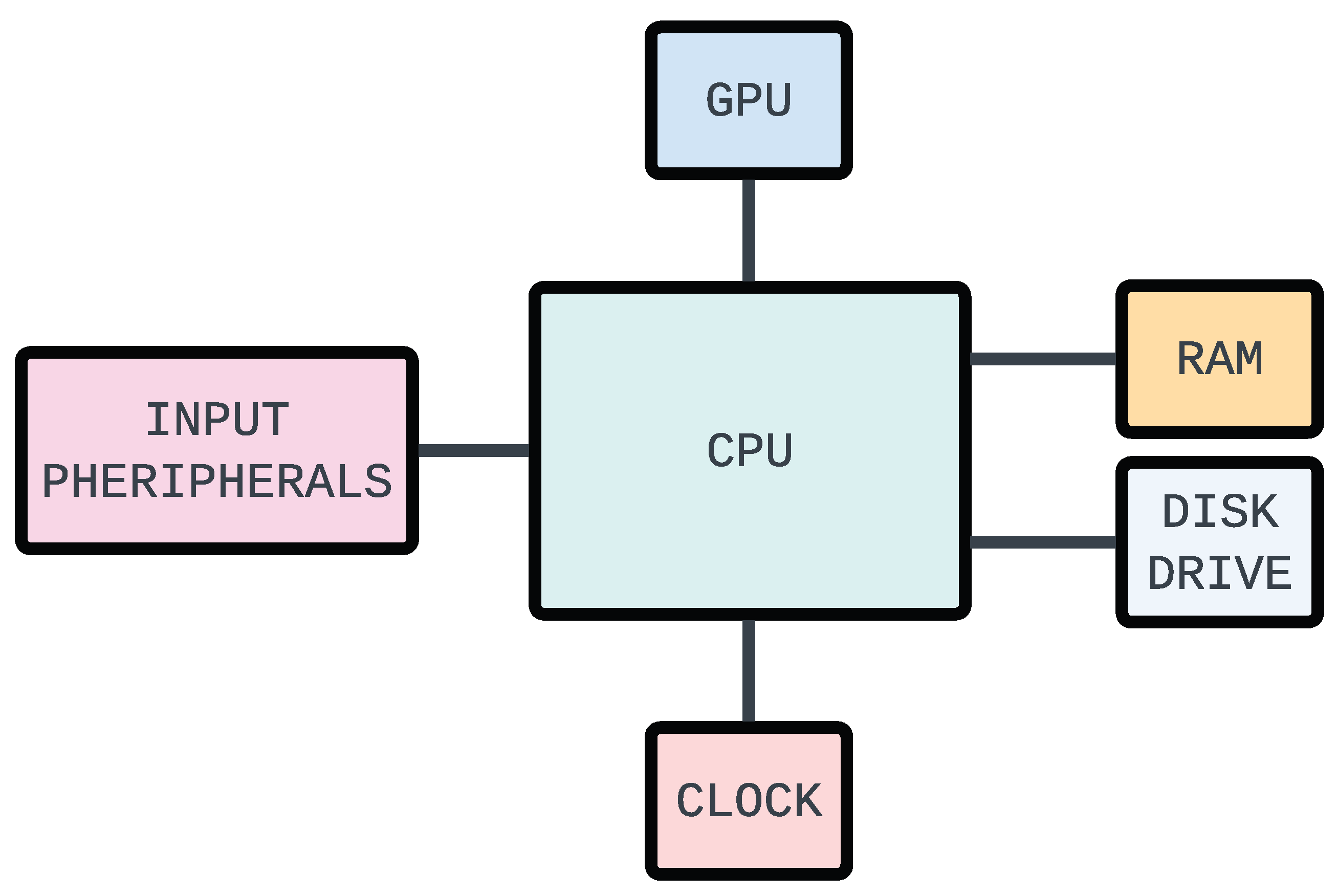

4.3. Block Diagram Analysis

4.3.1. Review of Identified Papers

4.3.2. Block Diagram Review Summary

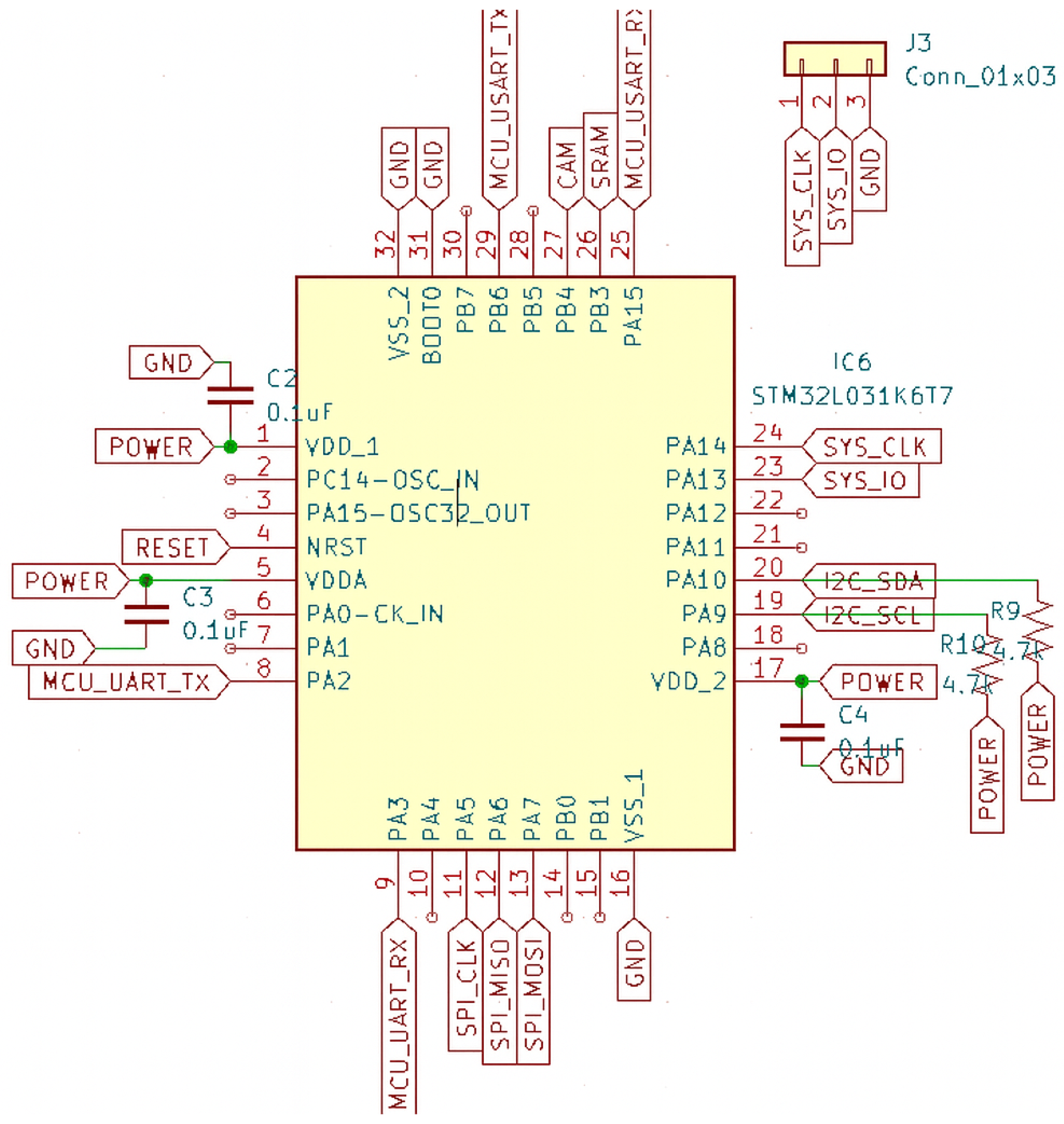

4.4. Electrical Circuit Diagram Analysis

4.4.1. Review of Identified Papers

4.4.2. Electrical Circuit Diagram Review Summary

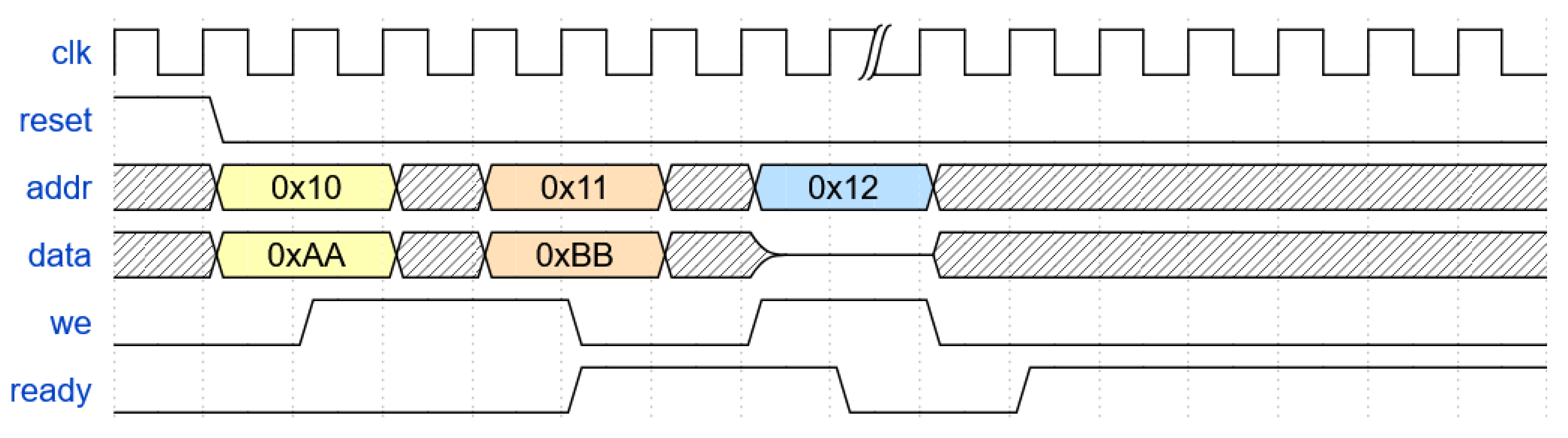

4.5. Timing Diagram Analysis

4.5.1. Review of Identified Papers

4.5.2. Timing Diagram Review Summary

4.6. Comparative Observations and Summary Across Illustration Types

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arslan, M.; Ghanem, H.; Munawar, S.; Cruz, C. A Survey on RAG with LLMs. Procedia computer science 2024, 246, 3781–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, L.; Moreno-García, C.F.; Elyan, E. A review of deep learning methods for digitisation of complex documents and engineering diagrams. Artificial Intelligence Review 2024, 57, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.; Garg, A. Text extraction using OCR: A Systematic Review. In Proceedings of the 2020 Second International Conference on Inventive Research in Computing Applications (ICIRCA), 2020; pp. 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Bhatia, P.K. A Detailed Review of Feature Extraction in Image Processing Systems. In Proceedings of the 2014 Fourth International Conference on Advanced Computing & Communication Technologies, 2014; pp. 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, R.; Nishio, M.; Do, R.K.G.; Togashi, K. Convolutional neural networks: an overview and application in radiology. Insights into imaging 2018, 9, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 2020, 404, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiss, B.A.; Elsaigh, W.A. Application of novel hybrid deep learning architectures combining convolutional neural networks (CNN) and recurrent neural networks (RNN): construction duration estimates prediction considering preconstruction uncertainties. Engineering Research Express 2024, 6, 032102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Xiao, A.; Xu, C.; Xu, Y.; et al. A Survey on Vision Transformer. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2023, 45, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lv, T.; Chen, J.; Cui, L.; Lu, Y.; Florencio, D.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Wei, F. Trocr: Transformer-based optical character recognition with pre-trained models. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 2023, Vol. 37, 13094–13102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Guo, Y.; Chen, H.; Hao, Z. Transformer-based neural network for answer selection in question answering. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 26146–26156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y. Rouge: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Proceedings of the Text summarization branches out, 2004; pp. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Saadany, H.; Orasan, C. BLEU, METEOR, BERTScore: Evaluation of metrics performance in assessing critical translation errors in sentiment-oriented text. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.14250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, E. A structured review of the validity of BLEU. Computational Linguistics 2018, 44, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Guo, D.; Lu, S.; Zhou, L.; Liu, S.; Tang, D.; Sundaresan, N.; Zhou, M.; Blanco, A.; Ma, S. Codebleu: a method for automatic evaluation of code synthesis. arXiv arXiv:2009.10297. [CrossRef]

- Sellam, T.; Das, D.; Parikh, A.P. BLEURT: Learning robust metrics for text generation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.04696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhu, J.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Qi, H.; Li, S.; Daxin, L. Extending BLEU Evaluation Method with Linguistic Weight. In Proceedings of the 2008 The 9th International Conference for Young Computer Scientists, 2008; pp. 1683–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, P.; Ferrari, V. End-to-end training of object class detectors for mean average precision. In Proceedings of the Asian conference on computer vision, 2016; Springer; pp. 198–213. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, S.A.; Strümke, I.; Thambawita, V.; Hammou, M.; Riegler, M.A.; Halvorsen, P.; Parasa, S. On evaluation metrics for medical applications of artificial intelligence. Scientific reports 2022, 12, 5979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leena, C.; Ganesh, M. Generating Graph from 2D Flowchart using Region-Based Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Students’ Conference on Electrical,Electronics and Computer Science (SCEECS), 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, B.G.; Dhanapanichkul, S.; Balakrishnan, R. Flowchart knowledge extraction on image processing. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence), 2008; pp. 4075–4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Camara, J.I.; Hammond, T. Flow2Code: from hand-drawn flowcharts to code execution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Symposium on Sketch-Based Interfaces and Modeling, 2017; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bangare, S.L.; Dubal, A.; Bangare, P.S.; Patil, S. Reviewing Otsu’s method for image thresholding. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research 2015, 10, 21777–21783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.; Gao, T.; Koller, D. Region-based segmentation and object detection. Advances in neural information processing systems 2009, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad, M.; Saman, M.Y.M.; Hitam, M.S.; Telipot, M. A review on OpenCV. In Terengganu: Universitas Malaysia Terengganu; 2015; Volume 3, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Yang, Z. GRCNN: Graph Recognition Convolutional Neural Network for synthesizing programs from flow charts. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.05980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulwani, S. Automating string processing in spreadsheets using input-output examples. ACM Sigplan Notices 2011, 46, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansner, E.R. Drawing graphs with Graphviz. Technical report; AT&T Bell Laboratories: Murray, Tech. Rep, Tech. Rep., 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, S.; Paul, S.; Masudul Ahsan, S.M. A Novel Approach to Rapidly Generate Document from Hand Drawn Flowcharts. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Region 10 Symposium (TENSYMP), 2020; pp. 702–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, M.; Warnecke, T.; Bartelt, C.; Rausch, A. Scribbler—drawing models in a creative and collaborative environment: from hand-drawn sketches to domain specific models and vice versa. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Fifteenth Australasian User Interface Conference-, 2014; Volume 150, 93–94. [Google Scholar]

- MENG, W.K. Development of program flowchart drawing tool. Technical report, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Malaysia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ramer-Douglas-Peucker, N.p. Ramer-douglas-peucker algorithm. >Online Referencing, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Scheidl, H.; Fiel, S.; Sablatnig, R. Word beam search: A connectionist temporal classification decoding algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2018 16th International conference on frontiers in handwriting recognition (ICFHR), 2018; IEEE; pp. 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti, A.; Naik, A.; Pansare, A.; Pant, U. Extracting Flowchart Features into a Structured Representation. Technical report. Mukesh Patel School of Technology Management and Engineering, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Shi, D.; Feng, G.; Zhao, X.; Luo, B. On-line handwritten flowchart recognition based on logical structure and graph grammar. In Proceedings of the 2015 5th International Conference on Information Science and Technology (ICIST), 2015; pp. 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supaartagorn, C. Web application for automatic code generator using a structured flowchart. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS), 2017; IEEE; pp. 114–117. [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle, M.C.; Wilson, T.A.; Humphries, J.W.; Hadfield, S.M.; et al. Raptor: introducing programming to non-majors with flowcharts. Journal of Computing Sciences in Colleges 2004, 19, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Adarsh, P.; Rathi, P.; Kumar, M. YOLO v3-Tiny: Object Detection and Recognition using one stage improved model. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS), 2020; pp. 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, Z.M.; Ibrahim, J. An overview of Darknet, rise and challenges and its assumptions. International Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology 2020, 8, 110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Pebrianto, W.; Mudjirahardjo, P.; Pramono, S.H.; Setyawan, R.A.; et al. YOLOv3 with spatial pyramid pooling for object detection with unmanned aerial vehicles. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.12344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhou, D.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, Y. Code generation from flowcharts with texts: A benchmark dataset and an approach. Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2022, 2022, 6069–6077. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadegan, H.; Rashidi Malki, B.; Radmehr, A.; Karimi, H.; Ilani, M.A. Comparative study of long short-term memory (LSTM), bidirectional LSTM, and traditional machine learning approaches for energy consumption prediction. Energy Exploration & Exploitation 2025, 43, 281–301. [Google Scholar]

- Vrahatis, A.G.; Lazaros, K.; Kotsiantis, S. Graph attention networks: a comprehensive review of methods and applications. Future Internet 2024, 16, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Neubig, G. TRANX: A transition-based neural abstract syntax parser for semantic parsing and code generation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.02720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Naseer, M.; Hayat, M.; Zamir, S.W.; Khan, F.S.; Shah, M. Transformers in vision: A survey. ACM computing surveys (CSUR) 2022, 54, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Gatti, P.; Kumar, Y.; Yadav, V.; Mishra, A. Towards making flowchart images machine interpretable. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, 2023; Springer; pp. 505–521. [Google Scholar]

- Tannert, S.; Feighelstein, M.G.; Bogojeska, J.; Shtok, J.; Arbelle, A.; Staar, P.W.; Schumann, A.; Kuhn, J.; Karlinsky, L. FlowchartQA: the first large-scale benchmark for reasoning over flowcharts. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Linguistic Insights from and for Multimodal Language Processing, 2023; pp. 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 conference of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics: human language technologies 2019, volume 1 (long and short papers), 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Montellano, C.D.B.; Garcia, C.; Leija, R.O.C. Recognition of handwritten flowcharts using convolutional neural networks. International Journal of Computer Applications 2022, 184, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Chaudhuri, B.B. A survey of Hough Transform. Pattern Recognition 2015, 48, 993–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.Y.; Sri Satya Aarthi, N.; Pooja, S.; Veerendra, B.; D, S. Enhancing Code Intelligence with CodeT5: A Unified Approach to Code Analysis and Generation. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Data Engineering (AIDE), 2025; pp. 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Y.; Lee, B.; Han, D.; Yun, S.; Lee, H. Character region awareness for text detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019; pp. 9365–9374. [Google Scholar]

- Darda, A.; Jain, R. Code Generation from Flowchart using Optical Character Recognition & Large Language Model. Authorea Preprints, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Supaartagorn, C. Web application for automatic code generator using a structured flowchart. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS), 2017; pp. 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Pratihar, S.; Chatterji, S.; Basu, A. Matching of hand-drawn flowchart, pseudocode, and english description using transfer learning. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2023, 82, 27027–27055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Herrera-Cámara, J.I.; Runyon, M.; Hammond, T. Flow2code: Transforming hand-drawn flowcharts into executable code to enhance learning. In Inspiring Students with Digital Ink: Impact of Pen and Touch on Education; Springer, 2019; pp. 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyao, H.; Maruyama, R. On-Line Handwritten flowchart Recognition, Beautification and Editing System. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition, 2012; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanh, V.; Debut, L.; Chaumond, J.; Wolf, T. DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.01108. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, X.L.; Zhang, Y.M.; Yin, F.; Liu, C.L. Instance GNN: A Learning Framework for Joint Symbol Segmentation and Recognition in Online Handwritten Diagrams. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2022, 24, 2580–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Dash, A.; Yin, W.; Wang, G. Beyond end-to-end vlms: Leveraging intermediate text representations for superior flowchart understanding. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.16420. [Google Scholar]

- Omasa, T.; Koshihara, R.; Morishige, M. Arrow-Guided VLM: Enhancing Flowchart Understanding via Arrow Direction Encoding. arXiv arXiv:2505.07864. [CrossRef]

- Soman, S.; Ranjani, H.; Roychowdhury, S.; Sastry, V.D.S.N.; Jain, A.; Gangrade, P.; Khan, A. A Graph-based Approach for Multi-Modal Question Answering from Flowcharts in Telecom Documents. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.22938. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.; Zhang, Q.; Caragea, C.; Dragut, E.; Latecki, L.J. Flowlearn: Evaluating large vision-language models on flowchart understanding. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.05183. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Chaurasia, P.; Varun, Y.; Pandya, P.; Gupta, V.; Gupta, V.; Roth, D. FlowVQA: Mapping multimodal logic in visual question answering with flowcharts. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.19237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, S.; Thomas, A.; Kaufman-Willis, L.; Wang, A. Growing an accessible and inclusive systems design course with PlantUML. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 54th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education V. 1, 2023; pp. 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Bordes, F.; Pang, R.Y.; Ajay, A.; Li, A.C.; Bardes, A.; Petryk, S.; Mañas, O.; Lin, Z.; Mahmoud, A.; Jayaraman, B.; et al. An introduction to vision-language modeling. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.17247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Bai, S.; Tan, S.; Wang, S.; Fan, Z.; Bai, J.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; et al. Qwen2-vl: Enhancing vision-language model’s perception of the world at any resolution. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.12191. [Google Scholar]

- Arbaz, A.; Fan, H.; Ding, J.; Qiu, M.; Feng, Y. GenFlowchart: parsing and understanding flowchart using generative AI. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Science, Engineering and Management, 2024; Springer; pp. 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- WU, X.H.; QU, M.C.; Liu, Z.Q.; Li, J.Z. A code automatic generation algorithm based on structured flowchart. Appl. Math 2012, 6, 1S–8S. [Google Scholar]

- Raghu, D.; Agarwal, S.; Joshi, S.; et al. End-to-end learning of flowchart grounded task-oriented dialogs. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.07263. [Google Scholar]

- Saoji, S.; Eqbal, A.; Vidyapeeth, B. Text recognition and detection from images using pytesseract. J Interdiscip Cycle Res 2021, 13, 1674–1679. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis, T.; Zhou, J. Page segmentation and classification. CVGIP: Graphical models and image processing 1992, 54, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2023; pp. 4015–4026. [Google Scholar]

- Philippovich, V.A.; Philippovich, A.Y. Modern Approaches to Extraction Text Data From Documents: Review, Analysis and Practical Implementation. In Proceedings of the 2025 7th International Youth Conference on Radio Electronics, Electrical and Power Engineering (REEPE), 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Du, H.; Hou, T. FR-DETR: End-to-End Flowchart Recognition With Precision and Robustness. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 64292–64301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, B.; Stuckenschmidt, H. Arrow R-CNN for Flowchart Recognition. Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition Workshops (ICDARW) 2019, Vol. 1, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision, 2020; Springer; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Shehzadi, T.; Hashmi, K.A.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. Object detection with transformers: A review. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.04670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bebis, G.; Georgiopoulos, M. Feed-forward neural networks. Ieee Potentials 2002, 13, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Piroi, F.; Hanbury, A. Multilingual patent text retrieval evaluation: CLEF–IP. In Information Retrieval Evaluation in a Changing World: Lessons Learned from 20 Years of CLEF; Springer, 2019; pp. 365–387. [Google Scholar]

- Miyao, H.; Maruyama, R. On-line handwritten flowchart recognition, beautification and editing system. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition, 2012; IEEE; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bresler, M.; Van Phan, T.; Prusa, D.; Nakagawa, M.; Hlavác, V. Recognition system for on-line sketched diagrams. In Proceedings of the 2014 14th International Conference on Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition. IEEE, 2014; pp. 563–568. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, D.; Xu, H.; Guo, X.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J. Mitigating Spatial Disparity in Urban Prediction Using Residual-Aware Spatiotemporal Graph Neural Networks: A Chicago Case Study. Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, 2025, 2351–2360. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, G.K.; Srivastava, S. ResNet-18 comparative analysis of various activation functions for image classification. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), 2023; IEEE; pp. 595–601. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Gao, S.; Zhang, X. A method for analyzing handwritten program flowchart based on detection transformer and logic rules. International Journal on Document Analysis and Recognition (IJDAR) 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresler, M.; Průša, D.; Hlaváč, V. Recognizing Off-Line Flowcharts by Reconstructing Strokes and Using On-Line Recognition Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2016 15th International Conference on Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition (ICFHR), 2016; pp. 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, S.; Liu, J.; Du, B.; Tao, D. Dptext-detr: Towards better scene text detection with dynamic points in transformer. Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 2023, 37, 3241–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X. Damo-yolo: A report on real-time object detection design. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.15444. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Xiao, B.; Tao, D.; Li, X. A survey of graph edit distance. Pattern Analysis and applications 2010, 13, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapantelakis, A.; Thakur, M.; Nikou, A.; Moradi, F.; Olrog, C.; Gaim, F.; Holm, H.; Nimara, D.D.; Huang, V. Using Large Language Models to Understand Telecom Standards. Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning for Communication and Networking (ICMLCN) 2024, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Muennighoff, N.; Lian, D.; Nie, J.Y. C-pack: Packed resources for general chinese embeddings. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 47th international ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in information retrieval, 2024; pp. 641–649. [Google Scholar]

- Guernsey, G. Harnessing Large Language Models for Automated Software Diagram Generation. Master’s thesis, University of Cincinnati, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fill, H.G.; Fettke, P.; Köpke, J. Conceptual modeling and large language models: impressions from first experiments with ChatGPT. Enterprise Modelling and Information Systems Architectures (EMISAJ) 2023, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Conrardy, A.; Cabot, J. From image to uml: First results of image based uml diagram generation using llms. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.11376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Webb, B. Architectural views. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Johri, A.; Sharma, S.; Chaudhary, V.; Raj, G.; Khurana, S. Analysis & Modeling of Deep Learning Techniques for Flowchart to Code Generation. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Networks and Cryptology (NETCRYPT), 2025; pp. 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, J.; Kabongo, S.; Giglou, H.B.; Zhang, Y. Overview of the CLEF 2024 simpletext task 4: SOTA? tracking the state-of-the-art in scholarly publications. Working Notes of CLEF; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Abeywickrama, D.B.; Bicocchi, N.; Zambonelli, F. SOTA: Towards a General Model for Self-Adaptive Systems. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 21st International Workshop on Enabling Technologies: Infrastructure for Collaborative Enterprises, 2012; pp. 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, B.; Aidarkhan, A.; Ristin, M.; Braunisch, N.; Diedrich, C.; van de Venn, H.W.; Wollschlaeger, M. Code and Test Generation for I4.0 State Machines with LLM-based Diagram Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 21st International Conference on Factory Communication Systems (WFCS), 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-García, C.F.; Elyan, E.; Jayne, C. New trends on digitisation of complex engineering drawings. Neural computing and applications 2019, 31, 1695–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.S. Automated Code Generation from Flowcharts: A Multimodal Deep Learning Framework for Accurate Translation and Debugging. Master’s thesis, Texas Tech University, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.; Pan, H.; Zhang, L. A novel pen-based flowchart recognition system for programming teaching. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Blended Learning, 2008; Springer; pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, B.M.; Salah, A. A Framework for Model-Based Code Generation from a Flowchart. International Journal of Computing Academic Research 2013, 2, 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Tammina, S.; et al. Transfer learning using vgg-16 with deep convolutional neural network for classifying images. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications (IJSRP) 2019, 9, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemani, B.; Patil, S.; Kotecha, K.; Tanwar, S. A review of graph neural networks: concepts, architectures, techniques, challenges, datasets, applications, and future directions. Journal of Big Data 2024, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S.; Lee, M. Block diagram-to-text: Understanding block diagram images by generating natural language descriptors. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: AACL-IJCNLP 2022, 2022; pp. 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Balaji, A.; Ramanathan, T.; Sonathi, V. Chart-text: A fully automated chart image descriptor. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.10636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. Journal of machine learning research 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Chen, Q. Research of image recognition method based on enhanced inception-ResNet-V2. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2022, 81, 34345–34365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Ba, J.; Kiros, R.; Cho, K.; Courville, A.; Salakhudinov, R.; Zemel, R.; Bengio, Y. Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2015; pp. 2048–2057. [Google Scholar]

- Orna, M.A.; Akther, F.; Masud, M.A. OCR Generated Text Summarization using BART. Proceedings of the 2024 27th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT) 2024, 2128–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S.; Jung, E.S.; Lee, M. Unveiling the Power of Integration: Block Diagram Summarization through Local-Global Fusion. Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics ACL 2024, 2024, 13837–13856. [Google Scholar]

- Julca-Aguilar, F.D.; Hirata, N.S.T. Symbol Detection in Online Handwritten Graphics Using Faster R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th IAPR International Workshop on Document Analysis Systems (DAS), 2018; pp. 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Roy, S.; Sarkar, N.; Malakar, S.; Sarkar, R. Circuit component detection in offline handdrawn electrical/electronic circuit diagram. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Calcutta Conference (CALCON). IEEE, 2020; pp. 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, A.; Kondo, T.; Mori, K.; Tsunekawa, S.; Kawamoto, E. An automatic circuit diagram reader with loop-structure-based symbol recognition. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 1988, 10, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, A.; Vajk, I. Document image analysis by probabilistic network and circuit diagram extraction. Informatica 2005, 29. [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus, E.O.; Lotufo, R.D.A. ECIR-an electronic circuit diagram image recognizer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings SIBGRAPI’98. International Symposium on Computer Graphics, Image Processing, and Vision (Cat. No. 98EX237), 1998; IEEE; pp. 254–260. [Google Scholar]

- Malakar, S.; Halder, S.; Sarkar, R.; Das, N.; Basu, S.; Nasipuri, M. Text line extraction from handwritten document pages using spiral run length smearing algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2012 international conference on communications, devices and intelligent systems (CODIS), 2012; IEEE; pp. 616–619. [Google Scholar]

- Sertdemir, A.E.; Besenk, M.; Dalyan, T.; Gokdel, Y.D.; Afacan, E. From Image to Simulation: An ANN-based Automatic Circuit Netlist Generator (Img2Sim). In Proceedings of the 2022 18th International Conference on Synthesis, Modeling, Analysis and Simulation Methods and Applications to Circuit Design (SMACD), 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupan, J. Introduction to artificial neural network (ANN) methods: what they are and how to use them. Acta Chimica Slovenica 1994, 41, 327. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Pan, T.; Ahsan, M.K. Hand-drawn electronic component recognition using deep learning algorithm. International Journal of Computer Applications in Technology 2020, 62, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, M.; Khoshkangini, R.; Nagendraswamy, H.; Conti, M. Hand drawn optical circuit recognition. Procedia Computer Science 2016, 84, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günay, M.; Köseoğlu, M.; Yıldırım, Ö. Classification of hand-drawn basic circuit components using convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (HORA), 2020; IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rachala, R.R.; Panicker, M.R. Hand-drawn electrical circuit recognition using object detection and node recognition. SN Computer Science 2022, 3, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Bhattacharya, A.; Sarkar, N.; Malakar, S.; Sarkar, R. Offline hand-drawn circuit component recognition using texture and shape-based features. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2020, 79, 31353–31373. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, M.; Mia, S.M.; Sarkar, N.; Bhattacharya, A.; Roy, S.; Malakar, S.; Sarkar, R. A two-stage CNN-based hand-drawn electrical and electronic circuit component recognition system. Neural Computing and Applications 2021, 33, 13367–13390. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshman Naika, R.; Dinesh, R.; Prabhanjan, S. Handwritten electric circuit diagram recognition: An approach based on finite state machine. Int J Mach Learn Comput 2019, 9, 374–380. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, A.; Mohan, A.; Indushree, B.; Malavikaa, M.; Narendra, C. Generation of Netlist from a Hand drawn Circuit through Image Processing and Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Signal Processing (AISP), 2022; IEEE; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Toga, A.W. Efficient skeletonization of volumetric objects. IEEE Transactions on visualization and computer graphics 1999, 5, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, C. Histograms of oriented gradients. Computer Vision Sampler 2012, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jakkula, V. Tutorial on support vector machine (svm). School of EECS, Washington State University 2006, 37, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Alhalabi, M.; Ghazal, M.; Haneefa, F.; Yousaf, J.; El-Baz, A. Smartphone handwritten circuits solver using augmented reality and capsule deep networks for engineering education. Education Sciences 2021, 11, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, Y. Circuit sketch recognition; Department of Electrical Engineering Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Patare, M.D.; Joshi, M.S. Hand-drawn digital logic circuit component recognition using svm. International Journal of Computer Applications 2016, 143, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabour, S.; Frosst, N.; Hinton, G.E. Dynamic routing between capsules. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Bohara, B.; Krishnamoorthy, H.S. Computer Vision based Framework for Power Converter Identification and Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Drives and Energy Systems (PEDES), 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, J.; Turabi, S.H.; Dengel, A. Text extraction for handwritten circuit diagram images. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, 2023; Springer; pp. 192–198. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer, J.; Roy, A.K.; Dengel, A. Instance segmentation based graph extraction for handwritten circuit diagram images. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.03155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Qiu, R.; Chang, Z.H.; Zhang, K.; Wei, H.; Chen, H.C. Circuit Diagram Retrieval Based on Hierarchical Circuit Graph Representation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.11658. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Liao, H.Y.M. You only learn one representation: Unified network for multiple tasks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.04206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likas, A.; Vlassis, N.; Verbeek, J.J. The global k-means clustering algorithm. Pattern recognition 2003, 36, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, J.; Wang, F. A review of keypoints’ detection and feature description in image registration. Scientific programming 2021, 2021, 8509164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafiz, A.M.; Bhat, G.M. A survey on instance segmentation: state of the art. International journal of multimedia information retrieval 2020, 9, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komoot, N.; Mruetusatorn, S. An Analysis of Electronic Circuits Diagram Using Computer Vision Techniques. Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Business and Industrial Research (ICBIR) 2024, 1581–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieste-Velasco, M. Application of a Pattern-Recognition Neural Network for Detecting Analog Electronic Circuit Faults. Mathematics;Modeling and Simulation in Engineering 2021, 9, 3247 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavithra, S.; Shreyashwini, N.; Bhavana, H.; Nikhitha, G.; Kavitha, T. Hand-drawn electronic component recognition using orb. Procedia Computer Science 2023, 218, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemker, D.; Maalouly, J.; Mathis, H.; Klos, R.; Ravanan, E. From Schematics to Netlists–Electrical Circuit Analysis Using Deep-Learning Methods. Advances in Radio Science 2024, 22, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Hu, X.; Yang, J. Line-CNN: End-to-End Traffic Line Detection With Line Proposal Unit. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2020, 21, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.R.; Cole, J.M. Digitizing images of electrical-circuit schematics. APL Machine Learning 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Vinayak, C. Image based Circuit Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Control, Automation, Robotics and Embedded Systems (CARE), 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matasyx, J.; Kittlery, C.G.J. Progressive probabilistic hough transform. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference, Southampton, UK, 1998; pp. 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Neuner, M.; Abel, I.; Graeb, H. Library-free Structure Recognition for Analog Circuits. In Proceedings of the 2021 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), 2021; pp. 1366–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, S.K.; Venkatachalam, K.; Sundaram, R. A novel mobile application for circuit component identification and recognition through machine learning and image processing techniques. International Journal of Intelligent Systems Technologies and Applications 2017, 16, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, U.; Sahoo, P.K.; Panda, M.K.; Panda, G. A ResNet-101 deep learning framework induced transfer learning strategy for moving object detection. Image and Vision Computing 2024, 146, 105021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfeliu, A.; Fu, K.S. A distance measure between attributed relational graphs for pattern recognition. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 2012, 3, 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L.; Xue, Z.; Zhang, K. GAML-YOLO: A Precise Detection Algorithm for Extracting Key Features from Complex Environments. Electronics 2025, 14, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, A.; Patil, S.S.; Poduval, G.M.; Shah, A.; Patil, R.P. Hand-Drawn Electronic Component Detection and Simulation Using Deep Learning and Flask. Cureus Journals 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gody, M. Hand-drawn electric circuit schematic components. 10.14. 2022) 2022. Available online: https://www.

- Cao, W.; Chen, Z.; Wu, C.; Li, T. A Layered Framework for Universal Extraction and Recognition of Electrical Diagrams. Electronics 2025, 14, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzair, W.; Chai, D.; Rassau, A. ElectroNet: An Enhanced Model for Small-Scale Object Detection in Electrical Schematic Diagrams. Research Square. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-3137489/v1. [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Sun, T.; Lin, M.; Gao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Liu, H.; et al. Paddleocr 3.0 technical report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.05595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, R.; Xu, T.; Xu, M.; Chen, E. Paddlepaddle: A production-oriented deep learning platform facilitating the competency of enterprises. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 24th Int Conf on High Performance Computing & Communications; 8th Int Conf on Data Science & Systems; 20th Int Conf on Smart City; 8th Int Conf on Dependability in Sensor, Cloud & Big Data Systems & Application (HPCC/DSS/SmartCity/DependSys), 2022; IEEE; pp. 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Ničković, D.; Bartocci, E.; Grosu, R. TD-Magic: From Pictures of Timing Diagrams To Formal Specifications. In Proceedings of the 2023 60th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qu, Q.; Wang, M.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Shen, L.; He, K. Deep learning for digitizing highly noisy paper-based ECG records. Computers in biology and medicine 2020, 127, 104077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehendale, N.; Mishra, S.; Shah, V.; Khatwani, G.; Patil, R.; Sapariya, D.; Parmar, D.; Dinesh, S.; Daphal, P. Ecg paper record digitization and diagnosis using deep learning. Available at SSRN 3646902. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Peli, T.; Malah, D. A study of edge detection algorithms. Computer graphics and image processing 1982, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaport, W.J. Implementation is semantic interpretation. The Monist 1999, 82, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N. Strict partial order. In The Routledge handbook of metaphysical grounding; Routledge, 2020; pp. 259–270. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Kenbeek, V.T.W.; Yang, Z.; Qu, M.; Bartocci, E.; Ničković, D.; Grosu, R. TD-Interpreter: Enhancing the Understanding of Timing Diagrams with Visual-Language Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.16844. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual instruction tuning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2023, 36, 34892–34916. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; et al. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

| Paper | Publication Year |

Method | Dataset Size | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [19] | 2020 | ROI | 25 | (Accuracy) 90% |

| [25] | 2020 | GRCNN | 2490 | (Accuracy) 94.1% |

| [33] | 2020 | Darknet, YOLOv3 | 161 | (mAP) 99.82% |

| [28] | 2020 | Otsu, beam search Dilation, RDP |

20 | (Accuracy) 86.52% |

| [40] | 2022 | LSTM | 50 | (BLEU) 55.68% |

| [59] | 2022 | InstGNN, DGL | 2957 | (Accuracy) 76.44% |

| [75] | 2022 | FR-DETR | 1000 | (F1-Score) 98.7% |

| [45] | 2023 | easyOCR, Code-T5 | 11,884 | (BLEU) 21.4% |

| [54] | 2023 | S-Distil-BERT | 50 | (Accuracy) 75.59% |

| [52] | 2024 | EasyOCR, OpenCV, Llama 2 | Unknown | (Success Rate) 75% |

| [85] | 2024 | LS-DETR | 1685 | (mAP) 99.18% |

| [68] | 2024 | LSTM | 550 | (F1-Score) 86.49% |

| [60] | 2024 | GPT-4o, Qwen2-VL | Unknown | (F1-Score) 88.23% |

| [92] | 2025 | GPT-4o, RAG | Unknown | (Accuracy) 100% |

| [96] | 2025 | GPT-4o | Unknown | (Accuracy) 92% |

| [101] | 2025 | GNN, R-CNN, Keras OCR | 875 | (mAP) 95.8% |

| [61] | 2025 | OCR, DAMO-YOLO, GPT-4o | 30 | (Accuracy) 89% |

| [99] | 2025 | GPT-4o | 95 | (Accuracy) 63% |

| [62] | 2025 | Qwen2-VL, RAG | 1586 | (Accuracy) 71.91% |

| Paper | Publication Year |

Method | Dataset Size | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [106] | 2022 | Faster R-CNN, T5 EasyOCR, HLT |

463 | (BLEU) 42.8% |

| [113] | 2024 | YOLOv5, Pororo OCR BART, ST, GPT-4V |

76k | (BLEU) 72.31% |

| Paper | Publication Year |

Method | Dataset | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [116] | 2020 | RLSA, Localization | 60 | (Accuracy) 91.28% |

| [134] | 2021 | CapsNet, HT | 800 | (mAP) 93.64% |

| [126] | 2022 | YOLOv5, HT, K-Means | 388 | (mAP) 99.19% |

| [130] | 2022 | OpenCV, OCR | Unknown | (Accuracy) 94% |

| [121] | 2022 | YOLOv5, OCR, HT | 330 | (Accuracy) 98% |

| [138] | 2022 | YOLOR, HT, K-Means | 176 | (mAP) 91.6% |

| [139] | 2023 | LSTM, CNN, RegEx | 2304 | Unknown |

| [140] | 2023 | Masked RCNN | 2208 | (Accuracy) 94% |

| [149] | 2024 | EasyOCR, L-CNN, CRAFT | 124 | (mAP) 43% |

| [146] | 2024 | CNN, OCR | 50 | (BLEU) 84% |

| [151] | 2024 | Tesseract OCR, PPHT | 15 | (BLEU) 85.6% |

| [159] | 2025 | Custom CNN | Unknown | (mAP) 96% |

| [141] | 2025 | GAM-YOLO, GED, VGG-16 | 227 | (mAP) 91.4% |

| [161] | 2025 | YOLOv7, PaddleClas, PaddleOCR |

5000 | (F1-Score) 96.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).