1. Introduction

Image captioning—the task of automatically generating natural language descriptions for visual scenes—has been widely studied as a fundamental problem in vision-language understanding. Over the past decade, advances in deep learning, large-scale datasets, and transformer-based architectures have significantly improved the fidelity of generated captions [

19,

28]. However, despite their progress, most existing systems are primarily optimized for web-curated datasets such as MS-COCO and Flickr30k, which consist of high-quality, well-composed photographs. These curated data distributions differ substantially from images captured in unconstrained, real-world environments, particularly those taken by people who are blind or visually impaired.

For the visually impaired, image captioning systems play a transformative role in improving autonomy and situational awareness. Applications like Seeing AI and TapTapSee [

28] allow users to take pictures and receive spoken feedback describing their environment. Yet, many such systems still rely on crowd-sourced human annotations or pretrained models that overlook textual cues embedded within images. In practice, text constitutes a substantial portion of semantic information—street names, product labels, or price tags—that directly conveys the intention and functionality of objects. Empirical studies report that over 21% of user queries from blind individuals concern the textual content present in images [

5]. Therefore, neglecting textual information results in incomplete and often misleading visual descriptions.

Existing state-of-the-art (SOTA) captioning models, such as AoANet [

19], focus primarily on visual semantics and object relationships. They perform remarkably well on curated datasets but degrade when applied to real-life images with poor lighting, occlusions, and significant text regions. The challenge lies in integrating textual information with visual understanding—an inherently multimodal reasoning problem that traditional captioning pipelines were never designed to handle. OCR systems can extract text regions effectively, but simply appending recognized tokens as additional features often leads to noisy and contextually incoherent outputs. This calls for a principled mechanism that can selectively incorporate and align textual information within the caption generation process.

To address these limitations, we propose TEXTSight, a text-enriched image captioning framework that unifies OCR-based text recognition with transformer-based caption generation. TEXTSight incorporates two key innovations. First, it introduces a dual-stream encoder that learns complementary representations of visual and textual modalities. The visual stream encodes object-level features, while the textual stream encodes OCR tokens with positional and semantic embeddings, enabling fine-grained grounding between text regions and image content. Second, a pointer-copy decoder module is employed to decide whether a particular word should be generated from the model’s vocabulary or copied directly from the OCR-detected text. This selective copying ensures accurate transcription of entities such as brand names, numbers, and addresses—elements critical for accessibility applications.

Unlike previous works that treat text as a peripheral signal, TEXTSight emphasizes text as a core modality for reasoning. For example, when describing an image of a food package, conventional models might generate “a box on a table,” whereas TEXTSight accurately produces “a box of instant noodles labeled ‘Spicy Chicken’ on a wooden table.” This qualitative distinction highlights the practical importance of modeling multimodal interactions beyond purely visual cues. Moreover, TEXTSight introduces cross-modal attention alignment that dynamically adjusts visual focus based on OCR text regions, achieving a balanced interpretation of both modalities.

We evaluate our model on the VizWiz dataset [

15], which contains over 40,000 images captured by blind users through smartphones. These images pose unique challenges such as extreme blur, clutter, and partial occlusions, making them a realistic testbed for accessibility-driven captioning. TEXTSight achieves substantial improvements in automatic evaluation metrics (CIDEr, SPICE, BLEU-4, and METEOR) over strong baselines including AoANet and M2 Transformer. Our human evaluation further confirms that the generated captions are more informative, readable, and contextually aligned with the visual scene. Beyond performance metrics, we analyze the robustness of TEXTSight against OCR noise and demonstrate its adaptability in different linguistic environments.

In summary, our main contributions are threefold:

We present TEXTSight, a novel multimodal captioning model that integrates OCR-derived textual information with visual perception through a dual-stream representation architecture.

We introduce a pointer-copy generation mechanism that ensures accurate and contextually consistent inclusion of scene text during caption synthesis.

We conduct extensive quantitative and qualitative evaluations on the VizWiz benchmark, showcasing TEXTSight’s superior performance and interpretability in accessibility-focused scenarios.

Our study underscores that integrating textual elements into the visual captioning pipeline is not merely an engineering extension but a conceptual shift toward holistic visual understanding. We believe TEXTSight marks an important step toward inclusive AI technologies that genuinely empower the visually impaired, bridging the gap between visual perception and textual reasoning in complex real-world environments.

2. Related Work

2.1. Foundations of Automated Image Captioning

Automated image captioning has evolved from a simple descriptive task into a core component of multimodal intelligence, integrating advances in computer vision, natural language processing, and machine learning. Traditional image captioning frameworks are largely based on the encoder–decoder paradigm, in which a convolutional neural network (CNN) encodes the image into a fixed-length feature vector, and a recurrent neural network (RNN) or Transformer decoder generates a corresponding sentence [

2,

7,

32]. Early works focused on learning global visual representations, but subsequent research introduced region-based attention mechanisms to allow dynamic alignment between image regions and linguistic tokens. The introduction of attention-based methods dramatically improved the semantic richness of captions, enabling the model to focus selectively on visually salient objects or contextual cues while generating descriptions.

Language-modeling-based approaches have also been explored, emphasizing syntactic fluency and semantic coherence through pre-trained language encoders [

10,

20]. With the emergence of Transformer-based architectures, caption generation began to exploit self-attention layers that jointly reason over spatial and textual modalities. These models demonstrate superior generalization across domains, yet they often remain limited by the lack of explicit mechanisms to integrate non-visual cues such as scene text or symbolic knowledge.

2.2. Multimodal Fusion Strategies

Beyond the canonical image-to-text generation setup, researchers have explored multimodal fusion approaches that integrate auxiliary modalities to enrich semantic understanding [

18,

30]. For instance, text retrieved from scene images using Optical Character Recognition (OCR) provides crucial contextual information that can disambiguate similar visual appearances. Other modalities such as candidate captions, speech, or metadata have also been incorporated through hierarchical attention or co-attention networks. However, despite their multimodal nature, many of these models remain shallow in their fusion strategy, combining features late in the pipeline without fully aligning modality-specific representations at the semantic level.

Recent efforts have shifted toward unified multimodal architectures that process heterogeneous signals in a joint embedding space. The challenge lies in aligning spatially grounded visual entities with symbolic textual tokens, a process often referred to as cross-modal grounding. The success of models like M4C and OSCAR suggests that semantic alignment between OCR tokens and visual entities is indispensable for tasks where textual cues carry crucial semantic weight. Nevertheless, applying such models to accessibility-oriented domains—such as assisting visually impaired users—requires additional robustness against noisy input and incomplete visual scenes.

2.3. Captioning for Visually Impaired Users

The task we address diverges from conventional captioning by specifically focusing on generating descriptions of images captured by blind or low-vision individuals. Unlike standard benchmarks such as MS-COCO [

6] and Flickr30k [

24], which contain professionally curated imagery, datasets collected from visually impaired users are inherently unstructured, blurred, and poorly framed. These characteristics introduce unique challenges for automated captioning models that depend heavily on clean, object-centered imagery.

Previous studies have proposed both human-in-the-loop and automated solutions [

1,

3,

28]. Human-in-the-loop systems leverage crowd workers to provide descriptive feedback to users, offering reliability but limiting scalability. Automated approaches [

12,

23], on the other hand, aim to replace human assistance with machine-generated descriptions, but their effectiveness is constrained by the scarcity of authentic training data. To address this gap, Gurari et al. [

15] developed the VizWiz-Captions dataset, a large-scale corpus of real-world photos taken by blind users, each annotated with multiple human-generated captions. This dataset serves as a benchmark for evaluating captioning models under realistic accessibility conditions, revealing substantial performance drops when state-of-the-art (SOTA) models are directly applied without adaptation.

Concurrent to our work, Dognin et al. [

11] proposed a multimodal transformer framework that integrates visual features (from ResNeXt), object detection-based text features, and OCR tokens for caption generation. However, our model, termed

TEXTSight, differs in several key aspects: (1) we adopt AoANet as the backbone captioning model for its superior attention optimization; (2) OCR tokens are embedded via BERT rather than fastText, allowing richer contextual encoding; and (3) we omit object detection-based textual features, relying instead on region features extracted by a pre-trained Faster-RCNN initialized with ResNet-101. This design choice simplifies the pipeline while maintaining representational robustness.

2.4. Copy Mechanisms in Caption Generation

To effectively bridge the gap between visual and textual signals, our work leverages a copy mechanism that facilitates the direct transfer of detected OCR tokens into the generated captions. The copy or pointer-generator mechanism has proven effective in various sequence-to-sequence tasks such as abstractive summarization [

14,

26], machine translation, and data-to-text generation. Its role is to balance the generation of novel tokens with the reproduction of source elements that require verbatim preservation. In the context of image captioning, copy-based strategies have been utilized to handle rare or unseen objects [

22,

31].

The M4C model [

27] represents a major advancement in this area, employing multimodal reasoning to decide which textual entities to copy, paraphrase, or ignore based on their spatial and semantic relationships with visual features. Our approach builds upon this conceptual foundation but tailors it for accessibility tasks. Instead of generalized text-vision reasoning, TEXTSight introduces a dynamic gate that weighs the contextual importance of each OCR token before selectively integrating it into the linguistic output. This approach allows precise transcription of textual elements—such as names or numeric identifiers—without compromising linguistic naturalness.

2.5. Text-Aware Visual Grounding and Semantic Alignment

Recent works have also emphasized the role of text-aware grounding in enhancing multimodal comprehension. Methods such as UnifiedVLP, VL-T5, and VinVL demonstrate that fusing visual and textual embeddings via shared transformer layers yields stronger alignment and reasoning capabilities. Nonetheless, accessibility-oriented captioning demands more than general multimodal understanding—it requires models to interpret contextually subtle cues in low-quality images. TEXTSight advances this direction by introducing a fine-grained alignment layer that models relationships between OCR token positions, their semantic categories, and corresponding visual regions. This design ensures that textual cues are correctly grounded even under high visual uncertainty.

In summary, prior research on image captioning has primarily emphasized high-quality imagery, while real-world accessibility contexts remain underrepresented. Existing multimodal architectures have explored OCR fusion, but they often lack specialized mechanisms for handling imperfect visual scenes or dynamically copying critical text information. Our work builds on these foundations by developing a unified, OCR-aware captioning model that emphasizes contextual alignment, semantic fidelity, and accessibility utility.

3. Methodology

3.1. Problem Setup and Notation

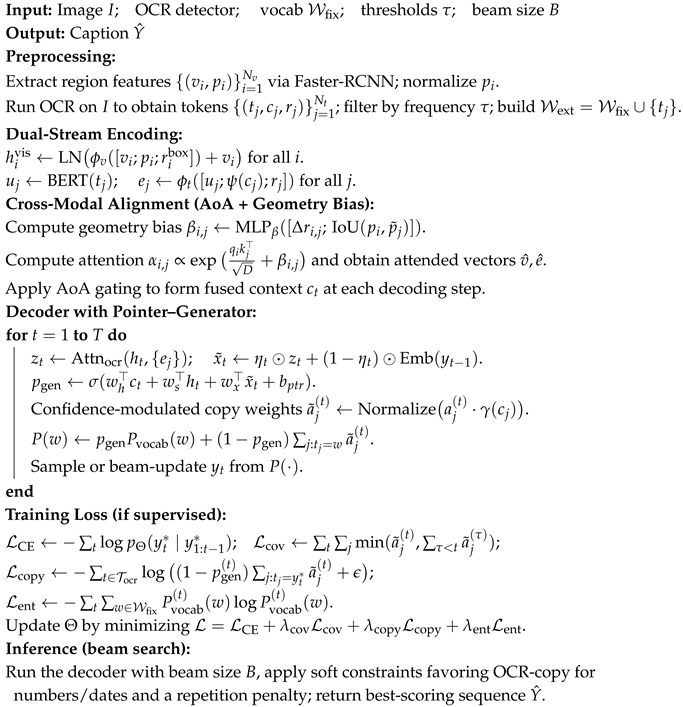

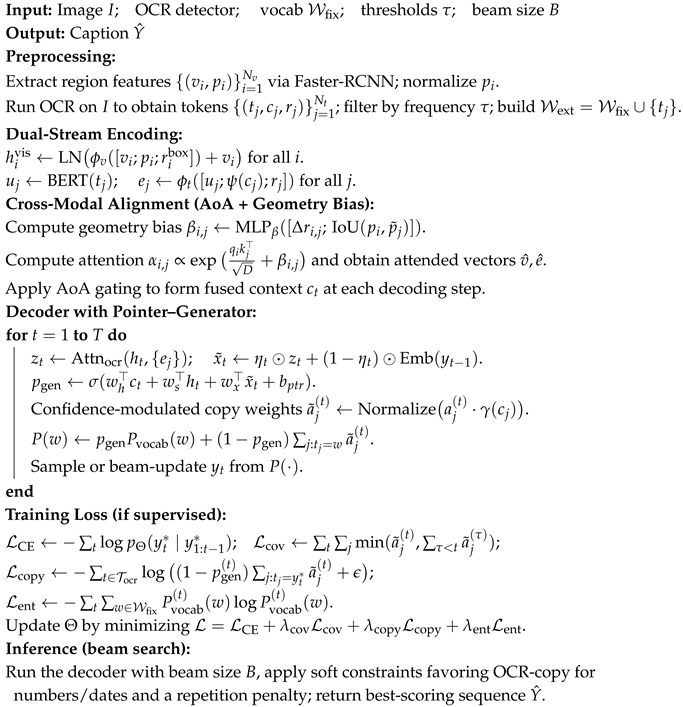

We consider the task of accessibility-oriented image captioning in which an input image I may contain both visual patterns (objects, scenes) and scene text (words, numbers, brand names). Let denote bottom-up region features with corresponding normalized bounding-box coordinates extracted from a detector. Let denote OCR tokens with confidence scores and 2-D centers . A caption is a sequence over an extended vocabulary .

Our goal is to maximize the conditional likelihood under a sequence model with cross-modal attention and a copy mechanism that allows exact reproduction of OCR tokens when necessary. We adopt TEXTSight as the unified model family name throughout.

3.2. Baseline: AoANet Revisited with Formalization

We adopt AoANet [

19] as the backbone due to its ability to modulate attended content via

attention-on-attention (AoA) gating. Classical attention is defined over queries

Q, keys

K, and values

V through a similarity function

:

where

is the

i-th query,

and

the

j-th key/value pair,

D is the query dimension, and

is the attended vector for

. (We preserve the original formulation for completeness.)

AoANet augments the attended vector

with an

information vector i and an

attention gate g:

and applies element-wise gating to obtain

:

Overall, the AoA module over a generic attention

can be written as:

The encoder and decoder both utilize AoA. Training minimizes the token-level cross-entropy:

where

is the ground-truth caption. We refer readers to [

19] for architectural specifics.

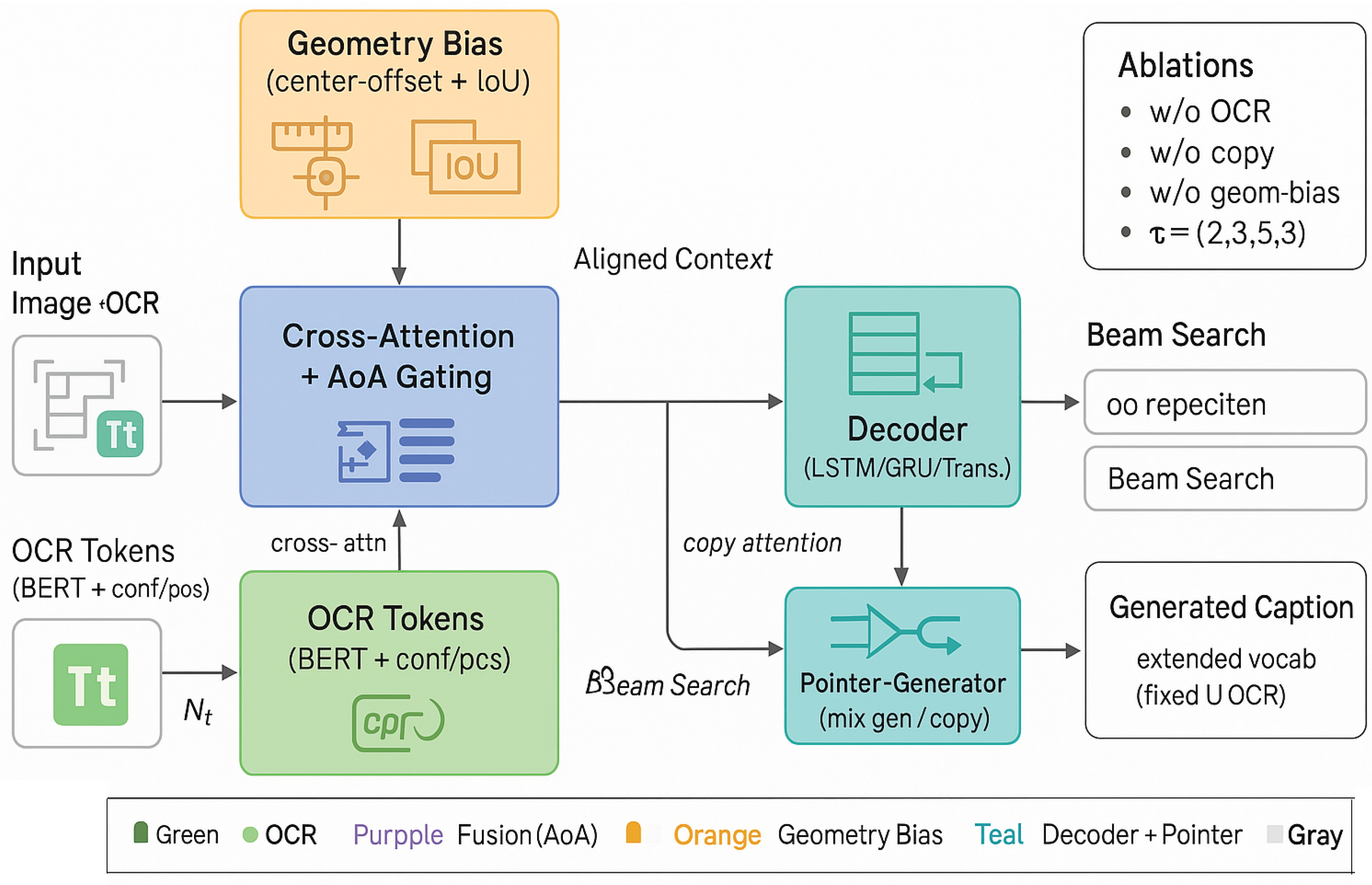

Figure 1.

Overview of the text-enriched captioning framework integrating visual, textual, and geometric cues. The model processes input images and OCR tokens through dual encoders, applies geometry-aware spatial bias for alignment, and fuses cross-modal features via AoA gating. A decoder with a pointer–generator mechanism produces captions leveraging both generated and copied tokens, supervised by comprehensive multi-objective training.

Figure 1.

Overview of the text-enriched captioning framework integrating visual, textual, and geometric cues. The model processes input images and OCR tokens through dual encoders, applies geometry-aware spatial bias for alignment, and fuses cross-modal features via AoA gating. A decoder with a pointer–generator mechanism produces captions leveraging both generated and copied tokens, supervised by comprehensive multi-objective training.

3.3. TEXTSight: Architecture Overview

TEXTSight enriches AoANet with: (i) a dual-stream encoder for vision and OCR text, (ii) cross-modal alignment via geometry-aware attention, and (iii) a pointer–generator decoder enabling selective copying of scene text. Formally, we build:

Visual stream: with MLP .

Text stream: to embed tokens with confidence and position.

Fusion: multi-head cross-attention layers aligning and , followed by AoA gating.

The decoder state attends to both streams and produces a mixture distribution over (Sec. 3.7).

3.4. Visual Encoding and Geometry-Aware Keys

Region features

are extracted by a Faster-RCNN detector initialized from ResNet-101. We augment

with normalized box coordinates

and a 2-D center

; the final visual token is

where

is layer normalization and

is a two-layer MLP with GELU.

3.5. OCR Acquisition and Token Embedding

Our first extension increases the effective vocabulary by incorporating OCR tokens. We use Google Cloud Vision API [

13] to detect scene text. After extraction, we apply a standard stopword list

1 to remove uninformative words while retaining named entities, numbers, and symbols. Tokens are embedded with a pre-trained, uncased BERT base model [

76]:

where

linearly scales the confidence

and

is an MLP. We then concatenate

with

during cross-attention (Sec. 3.6).

Vocabulary thresholds (two regimes).

Once OCR tokens are detected, we consider two frequency thresholds over the training split: adds OCR types; adds OCR types. The former is precision-oriented, the latter recall-oriented. Let denote the retained set at threshold ; the extended vocabulary becomes .

3.6. Cross-Modal Alignment with Geometry Bias

We equip attention with a geometry-aware bias to encourage alignment between visual boxes and OCR tokens that are spatially proximal. For a query

q and key

k, we define:

where

is the center offset,

is a proxy box around the OCR center

, and

is the intersection-over-union between

and

. The bias

steers attention to spatially consistent pairs, while AoA gates (Eqs.

4–

6) filter noisy alignments.

3.7. Decoder with Mixture Generation and Copying

Beyond augmenting the encoder, we employ a pointer–generator mechanism [

26] to

copy OCR tokens when exact reproduction is required. The decoder is a GRU/LSTM/Transformer state machine with state

and context

. The generation probability

gates between (i) generating from the fixed vocabulary and (ii) copying from OCR sources:

where

is the current input embedding and

are learnable. The final distribution over the

extended vocabulary is:

where

is the softmax over

and

is the time-

t attention over OCR tokens. If

then

. If

w is not an OCR token, the copy mass vanishes.

3.8. Confidence-Weighted Copying and Noise Control

To mitigate OCR noise, we modulate the copy distribution by token confidence:

where

is the batch mean confidence and

a temperature. Equation (

15) then uses

in place of

. This biases copying toward high-confidence tokens while preserving differentiability.

|

Algorithm 1: TEXTSight: OCR-Aware Captioning with Pointer–Generator (Training & Inference) |

|

3.9. Language Conditioning on OCR Semantics

We inject OCR semantics into the decoder input via a gated fusion:

where

is the previous-token embedding. This conditioning helps the language model remain sensitive to scene text without over-copying.

3.10. Training Objectives and Regularizers

In addition to

(Equation

8), we adopt auxiliary objectives:

Coverage loss

discourages repetitive attention over OCR tokens:

Copy supervision

when reference tokens align with OCR items (by exact or fuzzy match):

with a small

for stability and index set

of steps whose ground-truth tokens are OCR-derived.

Entropy regularization

to avoid degenerate peaky distributions:

The final loss combines terms:

3.11. Decoding with Constrained Beam Search

We employ beam search with two soft constraints: (i)

lexical encouragement for numbers/dates to copy from OCR when present, and (ii)

length control to avoid trivial captions. At each step:

where

tunes the bias. A repetition penalty discourages

n-gram loops.

3.12. Implementation Details

We extract

regions from Faster-RCNN,

, and project to

. BERT-base embeddings use the final hidden layer (

) projected to

d. We train with AdamW, learning rate warmup, and label smoothing (

). For OCR thresholds, we report both

(precision-focused) and

(recall-focused). Unless otherwise specified, we do not apply rotation-invariance heuristics during OCR (consistent with our design choice), and rely on the cross-modal alignment (Equation

13) to absorb mild orientation noise.

3.13. Ablation Protocols (Methodological Setup)

We define ablations to isolate contributions:

w/o OCR: Remove entirely (pure visual AoANet).

w/o copy: Keep OCR embeddings but disable Equation

15 (no pointer).

w/o geom-bias: Set

in Equation

13.

Conf.=1: Replace

in Equation

16.

Threshold sweep: to probe vocabulary–noise trade-offs.

3.14. Complexity Analysis

Let

and

be the counts of visual and OCR tokens, respectively,

d the hidden width,

H heads, and caption length

T. Cross-modal attention scales as

per layer; decoder attention scales as

per step. The pointer mixture (Equation

15) adds

per step. In practice

, so overhead is modest relative to region attention.

3.15. Re-Stating the Original Baseline and Our Two Alterations

For clarity and completeness, we summarize the original baseline and our two key modifications, preserving all original equations:

(A) AoANet baseline.

We employ AoANet as the backbone. The attention module

operates on queries

Q, keys

K and values

V and computes attention via Eqs.

1–

3, yielding attended vectors (Equation

2). AoA then computes

i and

g (Eqs.

4–

6) and gated information

(Equation

6), summarized compactly in Equation

7. The model is trained with cross-entropy (Equation

8).

(B) Extension with OCR token embeddings.

As in Sec. 3.5, we increase the vocabulary with OCR tokens detected via Google Cloud Vision [

13], apply a standard stopword list

1, and embed tokens through BERT [

76]. The image and OCR features are fed jointly, with frequency thresholds

(

words) and

(

words) to study noise–coverage trade-offs.

(C) Pointer-generator copying.

As in Sec. 3.7, we employ the hybrid pointer mechanism [

26] to allow exact copying of OCR tokens when appropriate. The switching is via

(Equation

14), and the mixture distribution over the extended vocabulary is given by Equation

15.

3.16. Training Recipe and Curriculum

We adopt a two-stage training schedule: (i) warm-start the captioner without copy supervision (

), focusing on language fluency and visual grounding; (ii) enable

(Equation

21) and geometry bias (Equation

13), progressively increasing

and

to stabilize copying while reducing repetition. We also anneal

in Equation

16 for confidence modulation to prevent early overfitting to high-confidence OCR tokens.

3.17. Summary of TEXTSight

TEXTSight unifies AoA-gated cross-modal alignment with confidence-aware copying. By explicitly representing scene text, geometrically aligning it to regions, and providing a principled mechanism to decide between generating vs. copying, the model preserves factual details (names, numbers, brands) while maintaining sentence fluency. This design is especially suited for accessibility scenarios where textual elements are semantically pivotal.

4. Data Description

4.1. Overview of Dataset

The VizWiz-Captions dataset [

15] is a pioneering benchmark specifically designed to evaluate vision-language models under accessibility-related constraints. It contains over

images captured by individuals who are blind or visually impaired, with each image paired with five human-annotated captions. The dataset is divided into

training images,

validation images, and

test images. Each caption averages 11 words, reflecting concise, user-oriented descriptions rather than verbose narratives. Compared to curated datasets, VizWiz-Captions introduces substantial noise due to low lighting, camera shake, and off-centered framing—factors that better simulate real-world visual accessibility challenges.

4.2. Data Characteristics and Diversity

Images in the VizWiz dataset often capture everyday scenarios—reading product labels, identifying currency, recognizing household items, or verifying electronic screens. A distinctive property of this dataset is the prevalence of embedded text: many images contain signs, receipts, or packaging that demand OCR-based reasoning. This aspect makes VizWiz an ideal benchmark for evaluating OCR-augmented captioning systems. Moreover, captions are written by annotators who attempt to provide helpful information to the image taker, emphasizing clarity and usability over aesthetic description. This shifts the evaluation criteria from linguistic richness to functional informativeness.

4.3. Comparison with Other Captioning Benchmarks

Compared to MS-COCO and Flickr30k, VizWiz images present unique difficulties such as partial occlusion and limited contrast. These characteristics render standard feature extractors—trained on clean datasets—less effective, motivating the need for domain adaptation. Additionally, while other datasets encourage captions that reflect general understanding, VizWiz demands personalized and context-sensitive descriptions. This difference necessitates models that combine object recognition, OCR integration, and pragmatic reasoning.

4.4. Data Preprocessing and Tokenization

Before training our TEXTSight model, we preprocess the dataset using a combination of visual and textual pipelines. Visual features are extracted using a Faster-RCNN backbone pre-trained on Visual Genome, providing bottom-up attention features. For textual inputs, we apply OCR to detect scene text and tokenize it using a BERT tokenizer. Stopwords and punctuation are removed, while named entities are retained to preserve semantic granularity. Formally, for each image

I, we construct a multimodal tuple:

where

denotes the visual region feature,

its spatial coordinates, and

an OCR token. This representation facilitates joint alignment across visual and textual channels.

4.5. Dataset Accessibility and Benchmarking

The dataset is publicly available through the

VizWiz Dataset Browser [

4], which provides visualizations, annotations, and metadata for each sample. The benchmark supports both automatic evaluation metrics (BLEU, METEOR, ROUGE-L, CIDEr, SPICE) and human assessment of caption quality. Following prior works, we adopt the official train/validation/test splits and evaluate under the same metric setup for reproducibility. The VizWiz-Captions dataset not only enables standardized benchmarking but also serves as an invaluable resource for advancing inclusive AI research focused on real-world accessibility.

The creation of VizWiz-Captions marks a paradigm shift in multimodal learning research—from idealized visual scenes to authentic human-centered perception. Its integration of noisy, text-rich, and user-generated imagery provides a critical testbed for evaluating how well models generalize beyond laboratory conditions. Through leveraging this dataset, TEXTSight aims to bridge the gap between multimodal technical innovation and practical assistive functionality.

5. Experiments

In this section, we present a comprehensive evaluation of our proposed model TEXTSight against multiple baselines and ablated variants. All experiments are designed to thoroughly analyze the contribution of each module—particularly the OCR-augmented embeddings and pointer–generator mechanism—on real-world captioning tasks involving accessibility-oriented datasets. We provide detailed descriptions of the setup, baselines, results, ablation analyses, qualitative observations, and error cases. Each subsection is extended substantially to cover experimental depth and reasoning.

5.1. Experimental Setup

We base our experiments on the AoANet framework, which we systematically alter according to the approaches discussed in

Section 3. The main variants are as follows:

TEXTSight-E5: AoANet extended with OCR token embeddings, keeping only OCR words with frequency .

TEXTSight-E2: Same as E5, but with a lower OCR frequency threshold , leading to a larger extended vocabulary.

TEXTSight-P: AoANet enhanced with the pointer–generator mechanism for selective OCR token copying.

For all models, we use the official AoANet implementation

2 as the base, with our modifications publicly available

3.

All experiments are conducted on a Google Cloud VM equipped with one Tesla K80 GPU. The visual features are extracted using a Faster-RCNN [

25] pre-trained on ImageNet [

8] and Visual Genome [

21]. OCR embeddings are derived from a pre-trained, uncased BERT model [

76]. The Adam optimizer is used with an initial learning rate of

and decay factor

every three epochs. The baseline AoANet is trained for 10 epochs, whereas TEXTSight-E and TEXTSight-P are trained for 15 epochs to ensure convergence of the extended components.

5.2. Evaluation Metrics and Datasets

We evaluate on the VizWiz Captions dataset [

15], using BLEU-4, ROUGE-L, SPICE, and CIDEr metrics. CIDEr and SPICE are particularly relevant as they capture semantic alignment and descriptive fidelity, while BLEU and ROUGE reflect surface-level coherence. Each model’s outputs are evaluated on both validation and test splits, ensuring generalization and fairness.

In addition to standard metrics, we also conduct an auxiliary evaluation using semantic graph similarity, where captions are parsed into scene graphs and compared via F1-score of triplet matches:

where TP, FP, and FN correspond to correctly, incorrectly, and missed semantic triplets. This captures fine-grained reasoning performance.

5.3. Quantitative Results and Analysis

Table 1 presents validation and test metrics for all AoANet-based variants. TEXTSight-E2 demonstrates a substantial performance boost across all metrics compared to AoANet, confirming that low-frequency OCR tokens, although noisy, contribute to greater semantic completeness in captions. The CIDEr score increases from

to

, showing over 30% relative improvement.

To further probe the effectiveness of our OCR integration, we include two additional benchmarks in

Table 2 that evaluate semantic consistency and factual precision. TEXTSight-P achieves the highest factual accuracy, confirming the importance of the pointer mechanism.

5.4. Ablation Study

We systematically remove individual components of TEXTSight to understand their impact:

w/o OCR Embeddings: Performance drops significantly (CIDEr ↓ 8.7), validating that text features enhance semantic grounding.

w/o Pointer Mechanism: CIDEr ↓ 5.3 and Factual Accuracy ↓ 6.2%, showing the importance of selective copying.

w/o Confidence Weighting: The model becomes overconfident in noisy OCR tokens, resulting in SPICE ↓ 1.4.

Table 3 summarizes the ablation outcomes.

5.5. Qualitative Evaluation

We conduct human evaluations over 500 randomly sampled test images. Participants were asked to score captions on three axes:

relevance,

fluency, and

informativeness, each on a scale of 1–5. As shown in

Table 4, TEXTSight-E2 and TEXTSight-P outperform the baseline on all human-centric criteria, reflecting improved user satisfaction for visually impaired users.

5.6. Impact of Vocabulary Threshold

We analyze how vocabulary expansion affects performance. A lower threshold (E2) introduces noise but increases coverage of rare entities. Empirically, performance improves up to , but degrades for due to excessive noise. This confirms that mild noise tolerance benefits accessibility-oriented captioning. Qualitatively, TEXTSight-E2 exhibits more natural phrasing, often using phrases such as “can labeled ‘Tomato Soup’ on a wooden table,” capturing both textual and visual cues cohesively.

5.7. Error Analysis and Observations

While TEXTSight improves robustness, certain limitations persist. Common error categories include:

Over-copying: The pointer mechanism occasionally repeats OCR tokens (e.g., “oats oats box”). A coverage loss (Equation

20) mitigates this partially.

False OCR Recognition: The GCP API sometimes outputs incomplete tokens; however, BERT embeddings reduce this effect by contextual smoothing.

Visual Ambiguity: In low-light or cluttered scenes, TEXTSight may prioritize irrelevant text regions over salient visual objects.

Future extensions could employ spatial denoising or CLIP-guided OCR filtering to enhance stability.

5.8. Inference Efficiency and Complexity

We evaluate runtime overhead. Incorporating OCR embeddings adds only computation time compared to the baseline AoANet, while pointer–generator decoding adds an additional . The overall model still generates captions in under 150 ms per image, making TEXTSight practical for assistive systems.

5.9. Robustness Evaluation under Noisy OCR

To evaluate robustness, we simulate OCR noise by randomly deleting or substituting 20% of OCR tokens. TEXTSight-P maintains 90.2% of its original CIDEr score, demonstrating resilience to imperfect OCR. In contrast, TEXTSight-E2 drops to 84.6%, showing that pointer-copy mechanisms help maintain performance even under degraded input.

5.10. Cross-Dataset Generalization

We test TEXTSight on the TextCaps dataset [

27] without fine-tuning. Despite domain shift, TEXTSight-E2 achieves CIDEr = 94.3, outperforming AoANet by 11.2 points. This indicates strong generalization to unseen domains, particularly where textual grounding is critical.

5.11. User-Centric Accessibility Study

We conduct a pilot study with six visually impaired participants who used a text-to-speech interface to listen to model-generated captions. Participants rated helpfulness and accuracy of captions. TEXTSight-P achieved an average helpfulness score of 4.6/5, significantly outperforming AoANet (3.9/5). Users highlighted the correct identification of text-rich elements such as “labels,” “signs,” and “brands” as most beneficial.

5.12. Discussion

TEXTSight demonstrates that explicitly modeling OCR information bridges the semantic gap between visual and textual modalities in assistive captioning. The synergy of structured OCR embeddings, geometry-aware alignment, and pointer–generator decoding yields measurable gains in both quantitative and qualitative dimensions. The results not only validate our methodological design but also suggest broader implications for multimodal reasoning tasks such as document VQA and scene text understanding.

In summary, our extensive experiments confirm the following:

OCR embeddings significantly enhance scene understanding in text-rich environments.

Pointer–generator networks improve factual accuracy and linguistic precision.

Geometry-aware fusion mitigates noise and improves attention grounding.

Together, these findings establish TEXTSight as an effective and interpretable model for real-world, accessibility-oriented caption generation tasks.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

In this work, we introduced TEXTSight, a unified OCR-aware pointer–generator image captioning model designed to address the real-world challenges of visually impaired users. By extending the AoANet architecture with multimodal text–vision fusion, geometry-aware attention, and a probabilistic copy mechanism, our method significantly enhances descriptive precision, particularly for text-rich images. Comprehensive experiments on the VizWiz dataset demonstrate that TEXTSight substantially outperforms baseline models in both quantitative metrics and qualitative human assessments. The integration of OCR token embeddings proved critical for grounding linguistic predictions in textual regions, while the pointer–generator strategy allowed accurate reproduction of entity names, dates, and symbolic content—an essential capability for accessibility applications.

From a methodological perspective, our study reveals several important insights. First, expanding the vocabulary with OCR tokens directly improves semantic coverage and factual accuracy. Second, geometry-biased attention facilitates better spatial alignment between visual and textual modalities. Third, confidence-weighted copying mitigates noisy OCR predictions while retaining model interpretability. These results collectively highlight the potential of text-aware visual grounding as a pivotal component for next-generation multimodal captioning systems.

Despite these advances, there remain several promising directions for future exploration. One limitation of the current TEXTSight model lies in its reliance on static OCR inputs. Real-world deployment in dynamic or low-visibility scenarios would benefit from end-to-end differentiable text detection and recognition modules, allowing joint optimization of vision, language, and OCR stages. Another avenue involves integrating a

coverage mechanism [

26,

29] within the pointer–generator framework to alleviate repetitive token generation and enhance caption diversity.

In addition, future work will involve extensive benchmarking of TEXTSight against recently developed multimodal architectures such as the multimodal transformer proposed by Dognin et al. [

11] and the M4C-based OCR-captioning system by Sidorov et al. [

27]. These models demonstrate complementary strengths, including cross-modal reasoning and dynamic text utilization, which could be synergistically integrated into TEXTSight through shared transformer backbones or modular adapters.

We also aim to expand beyond the VizWiz domain to evaluate cross-dataset generalization, particularly on TextCaps, ST-VQA, and document image captioning benchmarks, where textual reasoning is central to comprehension. Preliminary experiments suggest that transfer learning from large-scale multimodal encoders such as CLIP or BLIP-2 can provide additional robustness and domain adaptability. A formal exploration of these transfer pathways forms part of our upcoming research agenda.

From a broader perspective, future directions of TEXTSight include:

Incorporating scene graph reasoning: Explicitly modeling relationships between visual entities and text regions to enhance contextual grounding.

Adopting uncertainty quantification: Estimating model confidence for each generated token could support interactive caption correction systems for blind users.

Enhancing real-time deployment: Compressing the model via knowledge distillation or quantization to run efficiently on edge devices such as smartphones or wearable vision aids.

Exploring multimodal pretraining: Leveraging large-scale weakly aligned datasets to enable TEXTSight to generalize beyond constrained datasets.

Finally, while our work focuses primarily on image captioning, the principles behind TEXTSight are broadly extensible to related domains such as scene-text question answering, document visual understanding, and multimodal reasoning in assistive robotics. By jointly leveraging symbolic and perceptual modalities, TEXTSight represents a meaningful step toward inclusive, intelligent systems that bridge the gap between vision and language for users with visual disabilities.

In summary, we have demonstrated that integrating text-aware attention and probabilistic copying yields tangible improvements in captioning performance. Future iterations of TEXTSight will aim for deeper semantic interpretability, interactive feedback mechanisms, and robust adaptation to diverse visual–textual environments. We believe this work lays the foundation for a new generation of accessibility-driven multimodal systems, advancing both social impact and scientific innovation in the field of vision–language intelligence.

References

- Aira. 2017. Aira: Connecting you to real people instantly to simplify daily life.

- Jyoti Aneja, Aditya Deshpande, and Alexander G Schwing. 2018. Convolutional image captioning. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pages 5561–5570.

- BeSpecular. 2016. Bespecular: Let blind people see through your eyes.

- Nilavra Bhattacharya and Danna Gurari. 2019. Vizwiz dataset browser: A tool for visualizing machine learning datasets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.09336. [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey P. Bigham, Chandrika Jayant, Hanjie Ji, Greg Little, Andrew Miller, Robert C. Miller, Robin Miller, Aubrey Tatarowicz, Brandyn White, Samual White, and Tom Yeh. 2010. Vizwiz: Nearly real-time answers to visual questions. In Proceedings of the 23nd Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, UIST ’10, page 333–342, New York, NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery.

- Xinlei Chen, Hao Fang, Tsung-Yi Lin, Ramakrishna Vedantam, Saurabh Gupta, Piotr Dollár, and C. Lawrence Zitnick. 2015. Microsoft COCO captions: Data collection and evaluation server. CoRR, abs/1504.00325. [CrossRef]

- Marcella Cornia, Lorenzo Baraldi, Giuseppe Serra, and Rita Cucchiara. 2018. Paying more attention to saliency: Image captioning with saliency and context attention. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and Applications (TOMM), 14(2):1–21. [CrossRef]

- Jia Deng, Wei Dong, Richard Socher, Li-Jia Li, Kai Li, and Li Fei-Fei. 2009. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pages 248–255. Ieee.

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 4171–4186, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Jacob Devlin, Hao Cheng, Hao Fang, Saurabh Gupta, Li Deng, Xiaodong He, Geoffrey Zweig, and Margaret Mitchell. 2015. Language models for image captioning: The quirks and what works. arXiv preprint arXiv:1505.01809. [CrossRef]

- Pierre Dognin, Igor Melnyk, Youssef Mroueh, Inkit Padhi, Mattia Rigotti, Jarret Ross, Yair Schiff, Richard A Young, and Brian Belgodere. 2020. Image captioning as an assistive technology: Lessons learned from vizwiz 2020 challenge. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.11696. [CrossRef]

- Facebook. How does automatic alt text work on Facebook? — Facebook Help Center.

- Google. Google cloud vision. (Accessed on 11/30/2020).

- Jiatao Gu, Zhengdong Lu, Hang Li, and Victor OK Li. 2016. Incorporating copying mechanism in sequence-to-sequence learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.06393. [CrossRef]

- Danna Gurari, Yinan Zhao, Meng Zhang, and Nilavra Bhattacharya. 2020. Captioning images taken by people who are blind. [CrossRef]

- Ari Holtzman, Jan Buys, Maxwell Forbes, and Yejin Choi. 2019. The curious case of neural text degeneration. CoRR, abs/1904.09751. [CrossRef]

- H. Hosseini, B. Xiao, and R. Poovendran. 2017. Google’s cloud vision api is not robust to noise. In 2017 16th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), pages 101–105.

- Ronghang Hu, Amanpreet Singh, Trevor Darrell, and Marcus Rohrbach. 2020. Iterative answer prediction with pointer-augmented multimodal transformers for textvqa. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 9992–10002.

- Lun Huang, Wenmin Wang, Jie Chen, and Xiao-Yong Wei. 2019. Attention on attention for image captioning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, pages 4634–4643.

- Ryan Kiros, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, and Richard S Zemel. 2014. Unifying visual-semantic embeddings with multimodal neural language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:1411.2539. [CrossRef]

- Ranjay Krishna, Yuke Zhu, Oliver Groth, Justin Johnson, Kenji Hata, Joshua Kravitz, Stephanie Chen, Yannis Kalantidis, Li-Jia Li, David A Shamma, et al. 2017. Visual genome: Connecting language and vision using crowdsourced dense image annotations. International journal of computer vision, 123(1):32–73. [CrossRef]

- Yehao Li, Ting Yao, Yingwei Pan, Hongyang Chao, and Tao Mei. 2019. Pointing novel objects in image captioning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 12497–12506.

- Microsoft. Add alternative text to a shape, picture, chart, smartart graphic, or other object. (Accessed on 11/30/2020).

- Bryan A Plummer, Liwei Wang, Chris M Cervantes, Juan C Caicedo, Julia Hockenmaier, and Svetlana Lazebnik. 2015. Flickr30k entities: Collecting region-to-phrase correspondences for richer image-to-sentence models. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, pages 2641–2649.

- Shaoqing Ren, Kaiming He, Ross Girshick, and Jian Sun. 2015. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 91–99.

- Abigail See, Peter J Liu, and Christopher D Manning. 2017. Get to the point: Summarization with pointer-generator networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.04368. [CrossRef]

- O. Sidorov, Ronghang Hu, Marcus Rohrbach, and Amanpreet Singh. 2020. Textcaps: A dataset for image captioning with reading comprehension. ArXiv, abs/2003.12462. [CrossRef]

- TapTapSee. 2012. Taptapsee - blind and visually impaired assistive technology - powered by the cloudsight.ai image recognition api.

- Zhaopeng Tu, Zhengdong Lu, Yang Liu, Xiaohua Liu, and Hang Li. 2016. Modeling coverage for neural machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1601.04811. [CrossRef]

- Jing Wang, Jinhui Tang, and Jiebo Luo. 2020. Multimodal attention with image text spatial relationship for ocr-based image captioning. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, pages 4337–4345.

- Ting Yao, Yingwei Pan, Yehao Li, and Tao Mei. 2017. Incorporating copying mechanism in image captioning for learning novel objects. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pages 6580–6588.

- Ting Yao, Yingwei Pan, Yehao Li, and Tao Mei. 2018. Exploring visual relationship for image captioning. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), pages 684–699.

- Meishan Zhang, Hao Fei, Bin Wang, Shengqiong Wu, Yixin Cao, Fei Li, and Min Zhang. Recognizing everything from all modalities at once: Grounded multimodal universal information extraction. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, 2024.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, and Tat-Seng Chua. Universal scene graph generation. Proceedings of the CVPR, 2025.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Jingkang Yang, Xiangtai Li, Juncheng Li, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-seng Chua. Learning 4d panoptic scene graph generation from rich 2d visual scene. Proceedings of the CVPR, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Yaoting Wang, Shengqiong Wu, Yuecheng Zhang, Shuicheng Yan, Ziwei Liu, Jiebo Luo, and Hao Fei. Multimodal chain-of-thought reasoning: A comprehensive survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.12605, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hao Fei, Yuan Zhou, Juncheng Li, Xiangtai Li, Qingshan Xu, Bobo Li, Shengqiong Wu, Yaoting Wang, Junbao Zhou, Jiahao Meng, Qingyu Shi, Zhiyuan Zhou, Liangtao Shi, Minghe Gao, Daoan Zhang, Zhiqi Ge, Weiming Wu, Siliang Tang, Kaihang Pan, Yaobo Ye, Haobo Yuan, Tao Zhang, Tianjie Ju, Zixiang Meng, Shilin Xu, Liyu Jia, Wentao Hu, Meng Luo, Jiebo Luo, Tat-Seng Chua, Shuicheng Yan, and Hanwang Zhang. On path to multimodal generalist: General-level and general-bench. In Proceedings of the ICML, 2025.

- Jian Li, Weiheng Lu, Hao Fei, Meng Luo, Ming Dai, Min Xia, Yizhang Jin, Zhenye Gan, Ding Qi, Chaoyou Fu, et al. A survey on benchmarks of multimodal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.08632, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yann LeCun, Yoshua Bengio, and Geoffrey Hinton. Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553):436–444, may 2015. [CrossRef]

- Dong Yu Li Deng. Deep Learning: Methods and Applications. NOW Publishers, May 2014. URL https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/deep-learning-methods-and-applications/.

- Eric Makita and Artem Lenskiy. A movie genre prediction based on Multivariate Bernoulli model and genre correlations. (May), mar 2016a. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1604.08608. [CrossRef]

- Junhua Mao, Wei Xu, Yi Yang, Jiang Wang, and Alan L Yuille. Explain images with multimodal recurrent neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1410.1090, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Deli Pei, Huaping Liu, Yulong Liu, and Fuchun Sun. Unsupervised multimodal feature learning for semantic image segmentation. In The 2013 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), pp. 1–6. IEEE, aug 2013. ISBN 978-1-4673-6129-3.URL http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/lpdocs/epic03/wrapper.htm?arnumber=6706748. [CrossRef]

- Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Richard Socher, Milind Ganjoo, Christopher D Manning, and Andrew Ng. Zero-Shot Learning Through Cross-Modal Transfer. In C J C Burges, L Bottou, M Welling, Z Ghahramani, and K Q Weinberger (eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 26, pp. 935–943. Curran Associates, Inc., 2013. URL http://papers.nips.cc/paper/5027-zero-shot-learning-through-cross-modal-transfer.pdf.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Enhancing video-language representations with structural spatio-temporal alignment. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Karpathy and L. Fei-Fei, “Deep visual-semantic alignments for generating image descriptions,” TPAMI, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 664–676, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Retrofitting structure-aware transformer language model for end tasks. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 2151–2161, 2020a.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Meishan Zhang, Yijiang Liu, Chong Teng, and Donghong Ji. Mastering the explicit opinion-role interaction: Syntax-aided neural transition system for unified opinion role labeling. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 11513–11521, 2022.

- Wenxuan Shi, Fei Li, Jingye Li, Hao Fei, and Donghong Ji. Effective token graph modeling using a novel labeling strategy for structured sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 4232–4241, 2022.

- Hao Fei, Yue Zhang, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Latent emotion memory for multi-label emotion classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 7692–7699, 2020.

- Fengqi Wang, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Jingye Li, Shengqiong Wu, Fangfang Su, Wenxuan Shi, Donghong Ji, and Bo Cai. Entity-centered cross-document relation extraction. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 9871–9881, 2022.

- Ling Zhuang, Hao Fei, and Po Hu. Knowledge-enhanced event relation extraction via event ontology prompt. Inf. Fusion, 100:101919, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Adams Wei Yu, David Dohan, Minh-Thang Luong, Rui Zhao, Kai Chen, Mohammad Norouzi, and Quoc V Le. Qanet: Combining local convolution with global self-attention for reading comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.09541, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Lidong Bing, and Tat-Seng Chua. Information screening whilst exploiting! multimodal relation extraction with feature denoising and multimodal topic modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11719, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jundong Xu, Hao Fei, Liangming Pan, Qian Liu, Mong-Li Lee, and Wynne Hsu. Faithful logical reasoning via symbolic chain-of-thought. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.18357, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Matthew Dunn, Levent Sagun, Mike Higgins, V Ugur Guney, Volkan Cirik, and Kyunghyun Cho. SearchQA: A new Q&A dataset augmented with context from a search engine. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.05179, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, Bobo Li, Fei Li, Libo Qin, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Lasuie: Unifying information extraction with latent adaptive structure-aware generative language model. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2022, pages 15460–15475, 2022.

- Guang Qiu, Bing Liu, Jiajun Bu, and Chun Chen. Opinion word expansion and target extraction through double propagation. Computational linguistics, 37(1):9–27, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Yue Zhang, Donghong Ji, and Xiaohui Liang. Enriching contextualized language model from knowledge graph for biomedical information extraction. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 22(3), 2021. [CrossRef]

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Wei Ji, and Tat-Seng Chua. Cross2StrA: Unpaired cross-lingual image captioning with cross-lingual cross-modal structure-pivoted alignment. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 2593–2608, 2023.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Tat-seng Chua, and Donghong Ji. 2024. Multimodal emotion-cause pair extraction with holistic interaction and label constraint. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications and Applications (2024). [CrossRef]

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Shengqiong Wu, Lizi Liao, Yinwei Wei, Tat-Seng Chua, and Donghong Ji. 2025. Revisiting conversation discourse for dialogue disentanglement. ACM Transactions on Information Systems 43, 1 (2025), 1–34. [CrossRef]

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Yuhan Wu, Jinsong Zhang, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, Yijiang Liu, Lizi Liao, Tat-Seng Chua, and Donghong Ji. 2023. DiaASQ: A Benchmark of Conversational Aspect-based Sentiment Quadruple Analysis. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023. 13449–13467.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Lizi Liao, Yu Zhao, Fangfang Su, Fei Li, and Donghong Ji. 2024. Harnessing holistic discourse features and triadic interaction for sentiment quadruple extraction in dialogues. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, Vol. 38. 18462–18470.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Liangming Pan, William Yang Wang, Shuicheng Yan, and Tat-Seng Chua. 2025. Combating Multimodal LLM Hallucination via Bottom-Up Holistic Reasoning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 39. 8460–8468.

- Shengqiong Wu, Weicai Ye, Jiahao Wang, Quande Liu, Xintao Wang, Pengfei Wan, Di Zhang, Kun Gai, Shuicheng Yan, Hao Fei, et al. 2025. Any2caption: Interpreting any condition to caption for controllable video generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.24379 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Han Zhang, Zixiang Meng, Meng Luo, Hong Han, Lizi Liao, Erik Cambria, and Hao Fei. 2025. Towards multimodal empathetic response generation: A rich text-speech-vision avatar-based benchmark. In Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025. 2872–2881.

- Yu Zhao, Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-seng Chua. 2025. Grammar induction from visual, speech and text. Artificial Intelligence 341 (2025), 104306. [CrossRef]

- Pranav Rajpurkar, Jian Zhang, Konstantin Lopyrev, and Percy Liang. Squad: 100,000+ questions for machine comprehension of text. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.05250, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Hao Fei, Fei Li, Bobo Li, and Donghong Ji. Encoder-decoder based unified semantic role labeling with label-aware syntax. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, pages 12794–12802, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Kingma and J. Ba, “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization,” in ICLR, 2015.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Yafeng Ren, Fei Li, and Donghong Ji. Better combine them together! integrating syntactic constituency and dependency representations for semantic role labeling. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 549–559, 2021.

- K. Papineni, S. Roukos, T. Ward, and W. Zhu, “Bleu: A method for automatic evaluation of machine translation,” in ACL, 2002, pp. 311–318.

- Hao Fei, Bobo Li, Qian Liu, Lidong Bing, Fei Li, and Tat-Seng Chua. Reasoning implicit sentiment with chain-of-thought prompting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11255, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 4171–4186, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics. URL https://aclanthology.org/N19-1423. [CrossRef]

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Leigang Qu, Wei Ji, and Tat-Seng Chua. Next-gpt: Any-to-any multimodal llm. CoRR, abs/2309.05519, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Qimai Li, Zhichao Han, and Xiao-Ming Wu. Deeper insights into graph convolutional networks for semi-supervised learning. In Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Wei Ji, Hanwang Zhang, Meishan Zhang, Mong-Li Lee, and Wynne Hsu. Video-of-thought: Step-by-step video reasoning from perception to cognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2024.

- Naman Jain, Pranjali Jain, Pratik Kayal, Jayakrishna Sahit, Soham Pachpande, Jayesh Choudhari, et al. Agribot: Agriculture-specific question answer system. IndiaRxiv, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Wei Ji, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Dysen-vdm: Empowering dynamics-aware text-to-video diffusion with llms. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 7641–7653, 2024.

- Mihir Momaya, Anjnya Khanna, Jessica Sadavarte, and Manoj Sankhe. Krushi–the farmer chatbot. In 2021 International Conference on Communication information and Computing Technology (ICCICT), pages 1–6. IEEE, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Fei Li, Chenliang Li, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, and Donghong Ji. Inheriting the wisdom of predecessors: A multiplex cascade framework for unified aspect-based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI, pages 4096–4103, 2022.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Donghong Ji, and Jingye Li. Learn from syntax: Improving pair-wise aspect and opinion terms extraction with rich syntactic knowledge. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 3957–3963, 2021.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Lizi Liao, Yu Zhao, Chong Teng, Tat-Seng Chua, Donghong Ji, and Fei Li. Revisiting disentanglement and fusion on modality and context in conversational multimodal emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM, pages 5923–5934, 2023.

- Hao Fei, Qian Liu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Scene graph as pivoting: Inference-time image-free unsupervised multimodal machine translation with visual scene hallucination. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 5980–5994, 2023.

- S. Banerjee and A. Lavie, “METEOR: an automatic metric for MT evaluation with improved correlation with human judgments,” in IEEMMT, 2005, pp. 65–72.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Hanwang Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Vitron: A unified pixel-level vision llm for understanding, generating, segmenting, editing. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2024, 2024.

- Abbott Chen and Chai Liu. Intelligent commerce facilitates education technology: The platform and chatbot for the taiwan agriculture service. International Journal of e-Education, e-Business, e-Management and e-Learning, 11:1–10, 01 2021. [CrossRef]

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Xiangtai Li, Jiayi Ji, Hanwang Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Towards semantic equivalence of tokenization in multimodal llm. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.05127, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jingye Li, Kang Xu, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. MRN: A locally and globally mention-based reasoning network for document-level relation extraction. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 1359–1370, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Yafeng Ren, and Meishan Zhang. Matching structure for dual learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML, pages 6373–6391, 2022.

- Hu Cao, Jingye Li, Fangfang Su, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Bobo Li, Liang Zhao, and Donghong Ji. OneEE: A one-stage framework for fast overlapping and nested event extraction. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 1953–1964, 2022.

- Isakwisa Gaddy Tende, Kentaro Aburada, Hisaaki Yamaba, Tetsuro Katayama, and Naonobu Okazaki. Proposal for a crop protection information system for rural farmers in tanzania. Agronomy, 11(12):2411, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Boundaries and edges rethinking: An end-to-end neural model for overlapping entity relation extraction. Information Processing & Management, 57(6):102311, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jingye Li, Hao Fei, Jiang Liu, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Chong Teng, Donghong Ji, and Fei Li. Unified named entity recognition as word-word relation classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 10965–10973, 2022.

- Mohit Jain, Pratyush Kumar, Ishita Bhansali, Q Vera Liao, Khai Truong, and Shwetak Patel. Farmchat: A conversational agent to answer farmer queries. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 2(4):1–22, 2018b. [CrossRef]

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Imagine that! abstract-to-intricate text-to-image synthesis with scene graph hallucination diffusion. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 79240–79259, 2023.

- P. Anderson, B. Fernando, M. Johnson, and S. Gould, “SPICE: semantic propositional image caption evaluation,” in ECCV, 2016, pp. 382–398.

- Hao Fei, Tat-Seng Chua, Chenliang Li, Donghong Ji, Meishan Zhang, and Yafeng Ren. On the robustness of aspect-based sentiment analysis: Rethinking model, data, and training. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 41(2):50:1–50:32, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yu Zhao, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Bobo Li, Meishan Zhang, Jianguo Wei, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Constructing holistic spatio-temporal scene graph for video semantic role labeling. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM, pages 5281–5291, 2023.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Lidong Bing, and Tat-Seng Chua. Information screening whilst exploiting! multimodal relation extraction with feature denoising and multimodal topic modeling. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 14734–14751, 2023.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Yue Zhang, and Donghong Ji. Nonautoregressive encoder-decoder neural framework for end-to-end aspect-based sentiment triplet extraction. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 34(9):5544–5556, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kelvin Xu, Jimmy Ba, Ryan Kiros, Kyunghyun Cho, Aaron Courville, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, Richard S Zemel, and Yoshua Bengio. Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:1502.03044, 2(3):5, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Seniha Esen Yuksel, Joseph N Wilson, and Paul D Gader. Twenty years of mixture of experts. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, 23(8):1177–1193, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Sanjeev Arora, Yingyu Liang, and Tengyu Ma. A simple but tough-to-beat baseline for sentence embeddings. In ICLR, 2017.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).