1. Introduction

Many forms of preventable risk, including hazardous environmental exposures, violence, crime transportation-related vulnerabilities, and inequities in protective social resources, follow spatial patterns that are not readily observable in traditional surveillance systems. Public health responses have historically relied on retrospective reporting and non-geographic datasets that barely detect early signs of emerging risk. Without spatial specificity, health systems and community partners remain constrained to reactive approaches, intervening only after harm has occurred and missing opportunities to prevent escalation in high-risk environments. Interpersonal violence (IPV) imposes significant physical, psychological, and economic consequences on survivors, families, and communities, and it remains a central concern in public health research and practice [

1]. IPV nonetheless represents only one category of preventable harm that is shaped by the structural, ecological, and situational environments in which people live, work, and access care.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) have transformed disease surveillance, environmental monitoring, and chronic condition management by enabling precise identification of spatial clustering, ecological disparities, and opportunity structures that contribute to population health outcomes [

2,

3]. Despite this demonstrated utility, GIS remains underutilized in prevention science, particularly in areas where behavioral, ecological, and environmental factors converge to produce preventable harms. In the IPV context, substance-related incidents, safety hazards, or other community-level risks, spatial epidemiology provides an essential foundation for identifying geographically patterned vulnerabilities and designing targeted prevention strategies [

4]. Integrating place-based intelligence into prevention efforts shifts the field toward precision public health by allowing practitioners to identify risk environments before incidents occur, tailor interventions to local conditions, and strengthen equitable access to protective resources [

4]. This broad, prevention-oriented framing underscores the need for a geospatial methodology that is capable of addressing multiple forms of harm while grounding its analytic approach in well-established behavioral and ecological theory.

This manuscript presents a comprehensive geospatial public health architecture designed to support anticipatory prevention across diverse healthcare, institution and urban environments. Although IPV serves as an important application area, the framework is intentionally broad and adaptable. It integrates surveillance indicators, ecological determinants, environmental exposures, and temporal dynamics into a unified spatial epidemiology model capable of identifying localized vulnerability zones and preventable environmental risk patterns. A multilevel prevention paradigm informed by behavioral theory and spatial epidemiology intelligence meshed into clinical triage, patient safety planning, coordinated service delivery, and community safety planning is recommended for precision prevention across diverse settings

2. The Geospatial Imperative in Interpersonal Violence Prevention

Most publicly available datasets relevant to IPV and other preventable harms lack the spatial identifiers necessary for precision prevention. For example, most national public-use files omit neighborhood, tract, and block-group identifiers, as well as environmental exposures and mobility contexts, all of which are essential for spatial epidemiology and contextual risk assessment [

5]. Secure-access administrative and institutional datasets contain these geographic markers but require secure access protocols and institutional review board approval. The inclusion of tract-level identifiers substantially reduces distortions caused by the modifiable areal unit problem and enables finer-grained spatial modeling that more accurately reflects community-level variation [

6]. Spatial identifiers are essential for linking preventable harms to social determinants of health (SDOH), environmental exposures, and neighborhood dynamics. Without geographically explicit data, analysts cannot detect micro-clusters, identify hot spots, evaluate ecological predictors, or integrate spatial risk information into precision prevention workflows across clinical and community systems.

2.2. Theoretical Foundations: Operationalizing Behavioral and Ecological Theories

The geospatial architecture presented in this manuscript draws from a broader behavioral theory framework that explains how structural, environmental, and situational factors shape patterns of risk, and preventable harm across communities. Rather than focusing solely on IPV, this framework acknowledges the wider spectrum of safety-related outcomes relevant to precision clinical and community prevention, including exposure to hazardous environments, opportunity-driven harms, and inequities in access to protective social conditions. Within this expanded conceptual foundation, constructs such as Social Disorganization Theory, Routine Activities Theory (RAT), and Environmental Criminology serve as illustrative examples of how established behavioral theories can be operationalized within spatial epidemiology to support anticipatory prevention.

RAT introduces a behavioral-situational dimension by suggesting that preventable harms occur when opportunity structures align with inadequate guardianship and environmental vulnerabilities [

8]. Although traditionally applied to crime, the core framework applies broadly to public health contexts involving environmental exposure, transportation risk, substance-related harm, and unsafe social or physical environments. GIS operationalizes these constructs using proxies such as mobility corridors, nighttime activity zones, guardianship indicators like lighting, and location-specific environmental hazards.

SDT highlights how community-level structural factors such as residential instability, economic deprivation, and weakened institutional capacity diminish collective efficacy and contribute to heightened vulnerability and reduced access to preventive resources [

7]. When translated into spatial indicators, these community stressors identify neighborhoods that may require enhanced clinical screening, community engagement, and targeted prevention strategies.

Environmental criminology extends beyond violence to emphasize how built-environment features, urban form, and routine spatial behaviors influence the distribution of preventable harms across communities [

9]. Factors such as street connectivity, land-use patterns, visibility, and service accessibility shape how individuals encounter risk or protection within their everyday environments. Operationalizing these features through spatial analysis allows for the identification of modifiable environmental conditions that can support place-based prevention strategies.

Together, these theories demonstrate that spatial epidemiology can incorporate behavioral, ecological, and environmental constructs into a unified analytic model capable of supporting a broad range of prevention priorities. Multilevel and spatially explicit approaches can reveal inequities and emerging vulnerabilities not apparent through individual-level analyses alone, informing tailored interventions across communities or institutions.

2.3. Value of GIS for Anticipatory Prevention and Health Equity

GIS provide essential capabilities for identifying, monitoring, and addressing spatially patterned vulnerabilities that contribute to multiple forms of preventable harm. By integrating geocoded indicators of neighborhood disadvantage, environmental exposures, population mobility, and guardianship conditions, GIS allows prevention scientists and practitioners to visualize how structural inequities manifest geographically and to detect emerging clusters of risk before they evolve into acute events. These spatial insights reveal risk patterns that are often invisible in conventional datasets, enabling more precise allocation of prevention resources and more equitable deployment of interventions across communities [

2,

10,

11,

12].

In contexts involving interpersonal violence, substance-related harm, environmental exposure risks, and other public health concerns, GIS enhances anticipatory prevention by illuminating the environmental, temporal, and social conditions that elevate the likelihood of harm. For example, spatial analyses can identify high-risk microenvironments shaped by poor lighting, limited surveillance, high transit flow, or concentrated commercial activity, which may influence both the opportunity for harm and the capacity for protective guardianship. These geospatial patterns provide the empirical grounding needed to design targeted environmental modifications, cross-sector outreach, and clinical screening protocols that account for contextual risk rather than relying solely on individual-level characteristics [9-11].

Importantly, GIS strengthens health equity by enabling practitioners to identify structurally marginalized neighborhoods where cumulative disadvantage increases vulnerability to preventable harm. Spatial epidemiology reveals where service gaps, environmental stressors, and systemic disinvestment intersect, guiding the distribution of prevention resources in ways that counterbalance longstanding inequities [

12]. When integrated with behavioral theory and the Socioecological Model, geospatial analysis helps clarify how structural and situational determinants converge to produce differential risk across communities, reinforcing the need for prevention approaches that are both context-specific and equity-oriented. In this way, GIS supports not only anticipatory prevention but also the broader goal of addressing health disparities through evidence-driven, place-based public health action.

3. Prevention-Focused Spatial Epidemiology Framework

A comprehensive spatial epidemiology framework for prevention requires the integration of geographic, ecological, environmental, and temporal indicators across multiple levels of influence. Although IPV remains a central illustrative application in this manuscript, the proposed model is intentionally structured to address a broader range of preventable harms shaped by structural and environmental conditions. This section presents the methodological foundation required to generate localized risk signatures and to support precision prevention across clinical, community, and institutional environments. The conceptual diagrams (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) presented in this section were conceptually developed by the author and generated using artificial intelligence tools to clearly illustrate the framework's multilevel spatial integration process, hotspot modeling workflow, and neighborhood-level risk surface generation that underpin the analytic approach described herein.

3.1. Multilevel Data Architecture for Spatial Prevention Modeling

A prevention-focused spatial epidemiology architecture incorporates incident-level and person-level indicators into geographically meaningful units such as census tracts, block groups, or generalized coordinates to detect neighborhood-scale variation. Environmental characteristics including zoning, lighting distribution, commercial activity, and transportation networks provide essential context for situational vulnerability. Socioecological indicators reflecting economic disadvantage, residential mobility, and collective efficacy deepen understanding of underlying structural risk [

10]. Secure-access administrative and institutional datasets contain additional temporal and situational markers, including time of day and contextual circumstances, which further strengthen the model’s capacity to detect fine-grained risk dynamics [

5,

6]. Integrating these spatial and temporal layers enables the development of dynamic place-based forecasting models that capture daily and seasonal fluctuations not visible in aggregated datasets.

3.1.1. Limitations in Surveillance and Administrative Data Infrastructure

Despite the utility of spatial epidemiology, prevention-relevant data systems remain highly fragmented, which reduces the feasibility of producing reliable risk surfaces and weakens multisector prevention planning. Within this context, the spatial workflow presented here adapts across diverse environments by integrating geographic units, contextual indicators, and incident or reporting data to reveal spatially patterned vulnerability across communities and institutions [

3,

5,

10,

11,

12]. Several factors illustrate how these data limitations undermine the development of reliable spatial risk surfaces including:

Lack of Standardized Geographic Identifiers: Public health, clinical, criminal justice, and social service datasets frequently lack standardized geographic identifiers or employ truncated geocoding to preserve confidentiality.

Limited Utility for Analysis: This truncation limits their utility for neighborhood-level analysis and cluster detection.

Omission in Public Data: Many public-use datasets omit block-group or tract identifiers altogether, preventing linkage to environmental exposures or SDOH.

Siloed Reporting and Quality Issues: Siloed reporting platforms, inconsistent definitions, and variations in data quality impede cross-dataset integration and reduce analytic completeness.

Institutional Fragmentation: Large institutions, such as academic institutions and military installations, maintain incident reporting, behavioral health encounters, environmental monitoring, and administrative records in separate systems that seldom interoperate. This makes it difficult to connect structural or situational context to prevention and safety outcomes.

3.2. Pathways to Data Integration and System Modernization

Addressing geospatial surveillance limitations requires deliberate investments in data interoperability, standardized geographic identifiers, and coordinated administrative governance. Routine incorporation of census tract or block-group geocodes across datasets would substantially improve cross-system alignment and support robust spatial modeling [

16]. Formal data-sharing agreements, shared taxonomies, and harmonized reporting protocols strengthen multisector collaboration by reducing fragmentation and establishing a common operational foundation for prevention efforts [

17]. Secure-access research infrastructures allow analysts to use restricted microdata with detailed geographic identifiers while maintaining strict confidentiality protections, enabling more precise spatial epidemiology analyses [

18]. Advances in administrative informatics and public health data modernization support real-time or near real-time integration of incident data, environmental sensors, and mobility indicators, allowing for dynamic space-time analyses that enhance situational awareness and early-warning capabilities [

19]. These modernization pathways improve organizational readiness across clinical, public health, and military environments, enabling more coordinated and proactive prevention.

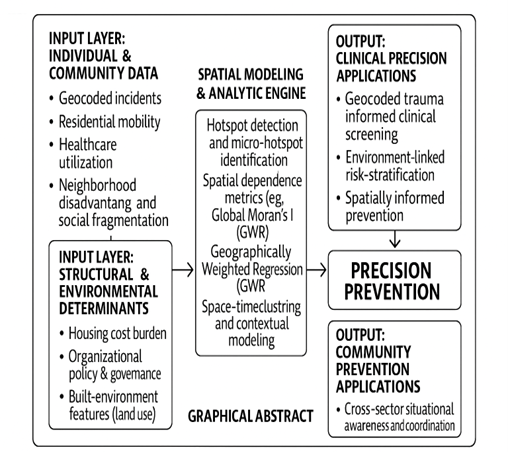

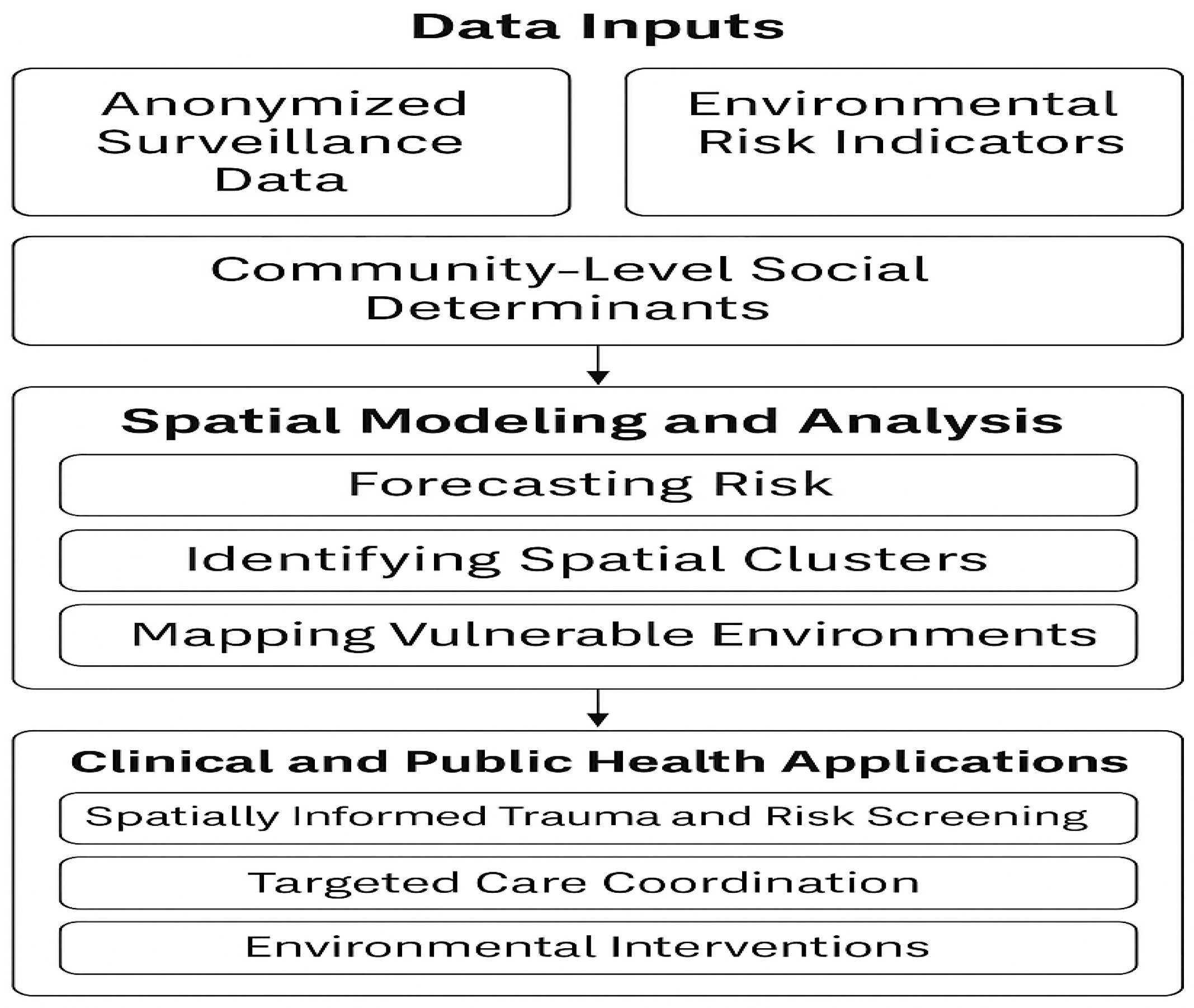

3.2.1. Figure 1. Conceptual Workflow for the Prevention-Focused Spatial Epidemiology Framework

Figure 1.

Prevention-focused spatial epidemiology workflow illustrating the transformation of multisector surveillance, administrative, environmental, and SDOH data into geocoded inputs for analytic processing. The model depicts key stages including spatial integration, cluster detection, forecasting, and identification of vulnerable environments. Outputs support precision prevention through spatially informed clinical screening, targeted care coordination, and environmental or structural intervention planning.

Figure 1.

Prevention-focused spatial epidemiology workflow illustrating the transformation of multisector surveillance, administrative, environmental, and SDOH data into geocoded inputs for analytic processing. The model depicts key stages including spatial integration, cluster detection, forecasting, and identification of vulnerable environments. Outputs support precision prevention through spatially informed clinical screening, targeted care coordination, and environmental or structural intervention planning.

3.3. Detection of Spatial Clustering and Spatial Dependence

Preventable harms, including IPV, often concentrate in identifiable microenvironments such as nightlife districts, university border areas, transitional housing corridors, and communities near military installations. These locations are shaped by mobility flows, limited guardianship, commercial density, and environmental features that influence risk. Spatial analytic tools such as kernel density estimation, Global Moran’s I, Local Indicators of Spatial Autocorrelation, and Getis-Ord Gi* statistics allow detection of clustering and assessment of spatial dependence, providing rigorous evidence of non-random geographic distribution [

20,

21,

22]. These analyses reveal micro-hotspots where prevention resources may have maximal impact. The use of Geographically Weighted Regression further allows assessment of how predictor relationships, such as the influence of alcohol outlet density or inadequate lighting, vary across communities, identifying context-specific drivers of preventable harm [

23]. Together, these methods strengthen the evidentiary basis for targeted, place-specific prevention strategies.

3.4. Integration of Ecological, Social, and Environmental Determinants

Structural and ecological conditions, extending far beyond individual characteristics, profoundly shape patterns of vulnerability across communities. Neighborhood disadvantage, housing instability, inequitable access to protective resources, and weakened social cohesion influence baseline risk environments and population-level exposure [

10,

12]. Temporal dynamics, including nighttime activity, event-driven mobility, and seasonal cycles, further modulate situational conditions that elevate or reduce the likelihood of harm. Integrating these socioeconomic, environmental, and temporal determinants within a spatial epidemiology framework produces multidimensional vulnerability surfaces that identify both where and when risk intensifies. These surfaces reveal microzones in which ecological stressors, environmental exposures, and built-environment features converge, providing an evidence base for precision prevention strategies rooted in multisector coordination and targeted environmental modification.

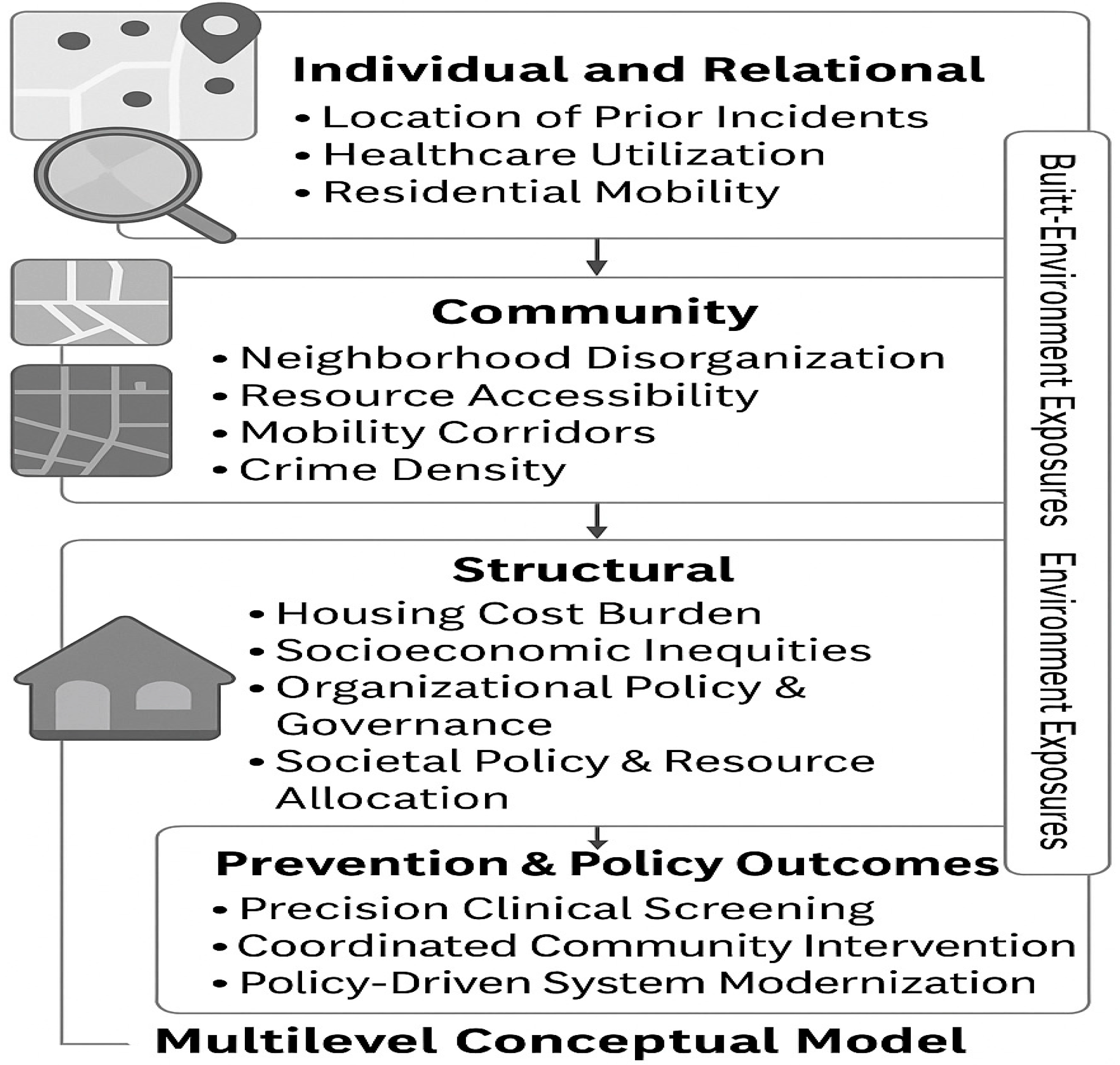

3.4.1. Figure 1. Multilevel Conceptual Model Linking Socio-Ecooicall Determinants to Spatially Patterned Risk

Figure 2.

Multilevel conceptual model integrating individual, relational, community, and structural determinants with environmental exposures and built-environment features to explain how spatially patterned vulnerability emerges. The figure illustrates how geocoded individual-level indicators, community conditions, structural inequities, and environmental factors interact within a spatial epidemiology framework to inform precision prevention strategies and targeted clinical and community interventions.

Figure 2.

Multilevel conceptual model integrating individual, relational, community, and structural determinants with environmental exposures and built-environment features to explain how spatially patterned vulnerability emerges. The figure illustrates how geocoded individual-level indicators, community conditions, structural inequities, and environmental factors interact within a spatial epidemiology framework to inform precision prevention strategies and targeted clinical and community interventions.

3.5. Spatial IPV Framework and Conceptual GIS Workflow

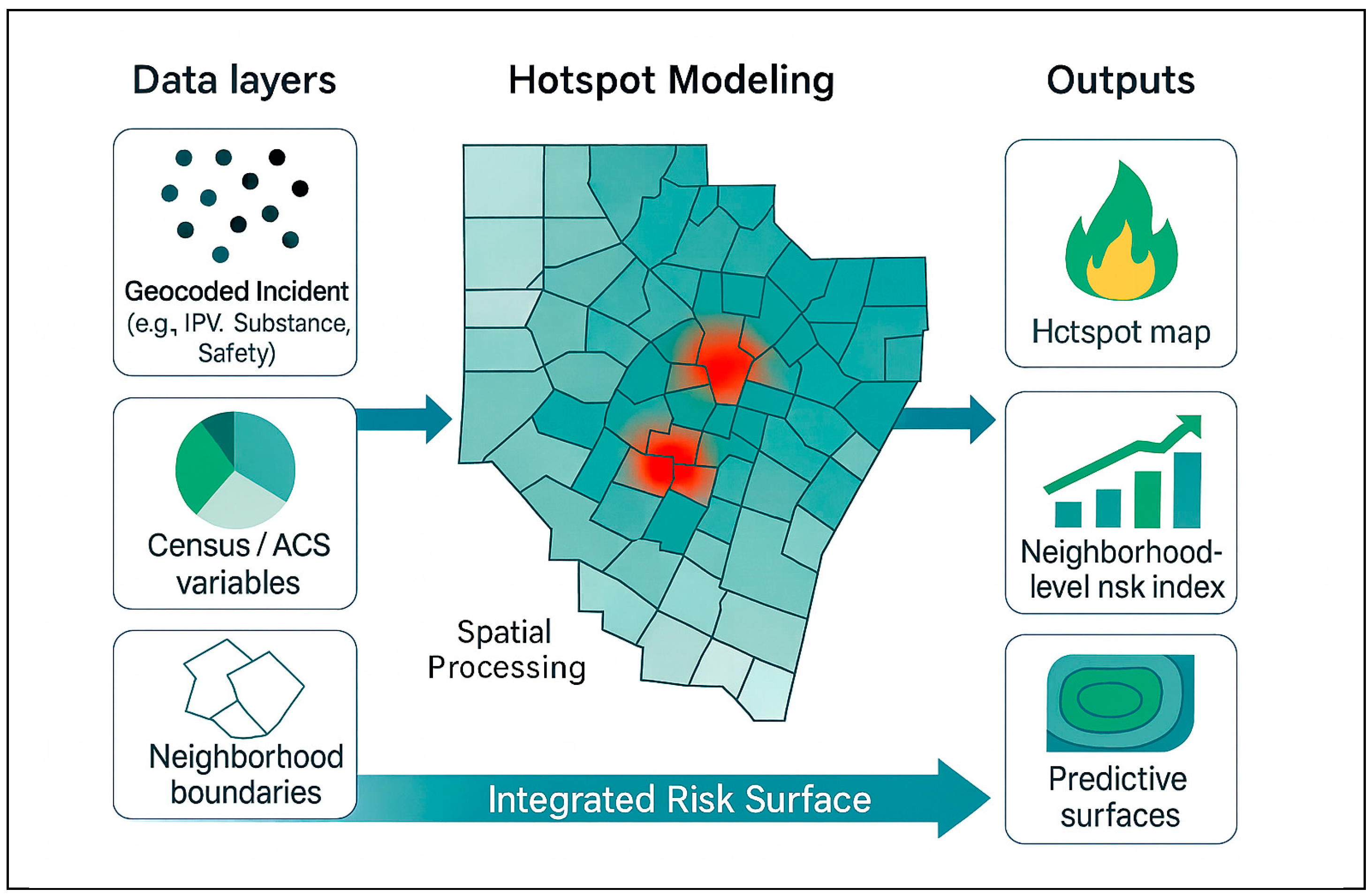

The conceptual GIS workflow (

Figure 3) demonstrates how multilevel contextual information can be spatially combined to identify micro-hotspots of interpersonal violence and generate neighborhood-level risk surfaces that support predictive modeling. The first panel depicts the underlying geographic units that anchor the analysis, which may include census boundaries, administrative zones, institutional districts, or other locally relevant polygons. The second panel overlays incident locations or density-adjusted counts that reveal clustered patterns of harm. The third panel incorporates structural and environmental predictors drawn from community indicators, organizational administrative records, or population-level surveys. The final integrated panel shows how hotspot modeling, kernel density estimation, or spatial smoothing convert these combined layers into a continuous risk surface that reflects both the spatial distribution of events and the contextual conditions that influence vulnerability. This GIS-based framework aligns with the manuscript’s overarching aim by translating multilevel data into interpretable spatial patterns, highlighting inequities, supporting theory-driven modeling, and illustrating how contextual forces shape the geographic expression of interpersonal violence risk.

3.5.1. Figure 3. Multilevel Conceptual Model Linking Socio-Ecooical Determinants to Spatially Patterned Risk

3.6. Applications of the Spatial Workflow Across Settings

This spatial workflow adapts across diverse environments by selecting IPV-relevant geographic units, contextual indicators, and incident or reporting data. Populations with high residential mobility or transient living conditions present unique challenges for modeling interpersonal violence risk, as spatial patterns may shift rapidly across time and place. Across such settings, the framework supports identification of micro-hotspots, structural vulnerability, and environmental conditions linked to IPV risk, severity, recurrence, and barriers to help-seeking.

The framework also strengthens trauma-informed clinical decision-making by embedding spatial context into routine screening workflows. Geocoded residential information can signal environmental risks that extend beyond individual self-report, particularly for patients living in structurally marginalized or environmentally hazardous areas. Integrating spatial risk indices into electronic health records enables clinicians to incorporate these contextual indicators into screening and decision-making [

24], improving identification of individuals who may require additional assessment, safety planning, or referral. Spatially informed decision support also guides clinicians in safe discharge planning and linkage to trauma-informed community resources, ensuring prevention strategies align with the structural realities of the populations served [

17].

Additional non clinical applications include:

National or Population-Level Datasets: At large geographic scales, census tracts or block groups map variability in IPV indicators (e.g., victimization survey responses or reporting patterns). Spatial integration of socioeconomic vulnerability, residential mobility, and resource access provides insight into regional patterns of IPV intensity and chronicity, highlighting communities facing disproportionate risk.

Military or Institutional Environments: Installation districts, housing zones, or unit areas examine how operational stressors, population turnover, isolation patterns, or duty-related schedules relate to IPV occurrence. Integrating indicators of institutional strain and access to services helps identify spatial concentrations of IPV near high-stress work areas or transitional housing spaces.

College or Campus Settings: Campus sectors, residence halls, or security patrol zones allow exploration of spatial clustering of dating violence, coercive control, and stalking. Combining campus climate indicators and environmental vulnerabilities reveals concentrated areas near social hubs or low-visibility pathways where tailored prevention may be most impactful.

Municipal or Community Settings: Neighborhoods, service districts, or precinct areas map IPV calls-for-service, emergency department encounters, or local agency data. Integrating socioeconomic stress, neighborhood disorder, housing instability, resource scarcity, and alcohol outlet density highlights micro-hotspots where contextual disadvantage magnifies IPV risk and limits service access.

4. Discussion

Spatial epidemiology provides a powerful mechanism for strengthening prevention across public health, community, and institutional settings by integrating geographic context into screening, situational awareness, and intervention planning. Although interpersonal violence serves as an illustrative case, the framework applies broadly to transportation hazards, substance-related incidents, environmental exposures, and community safety concerns. By combining predictive analytics with contextual indicators, organizations can adopt earlier, more targeted, and more equitable prevention strategies that reflect that reflect

lived contextual realities [

19,

20]. At its core, this framework shifts prevention from individual-only assessments toward a more comprehensive understanding of how structural, ecological, and situational factors produce spatially patterned vulnerability. Spatial analyses reveal where clusters of preventable harm emerge, how these patterns change over time, and which communities face disproportionate burdens. When integrated into multisector prevention systems, spatial intelligence enhances organizational readiness, improves resource allocation, and strengthens the evidence base for place-based and multisector prevention approaches.

4.1. Spatially Informed Prevention and Clinical Decision Support

Spatial indicators can be incorporated into a variety of assessment and decision-support processes to improve the identification of individuals and communities that may require enhanced safety planning or targeted prevention services. Geocoded residential information and neighborhood-level indicators reveal contextual risks not captured through individual self-report, especially in structurally marginalized or environmentally hazardous areas. Integrating spatial risk indices into existing screening or triage systems allows practitioners to recognize these contextual factors during safety assessments and referral processes [

24]. This approach enhances prevention precision by aligning outreach and service coordination with the structural realities that shape exposure to preventable harm [

17].

4.2. Cross-Sector Coordination and Shared Prevention Intelligence

Spatial epidemiology strengthens collaboration across healthcare systems, public health agencies, social services, municipal departments, universities, and military installations by providing a shared view of geographically patterned vulnerability. Unified geospatial dashboards, spatially linked datasets, and space-time monitoring tools reveal emerging clusters, service gaps, and resource disparities, supporting coordinated action among partners [

25]. Routine use of spatial intelligence in cross-sector prevention planning reduces fragmentation, enhances operational alignment, and enables organizations to collectively address risk environments that span jurisdictional boundaries. In military and other institutional settings, these capabilities also reinforce readiness, environmental safety planning, and geographically targeted interventions [

15].

4.5. Environmental and Situational Prevention Strategies

Spatial analysis provides actionable guidance for modifying the physical and situational environments that influence exposure to preventable harm. Geographic patterns of risk can inform interventions such as improved lighting, enhanced guardianship, optimized transit routing, and adjustments to land use or alcohol outlet density. Evidence demonstrates that targeted environmental modifications can meaningfully reduce violence and related public health harms by altering the opportunity structures that facilitate risk [

26]. When combined with upstream structural interventions and context-aware screening, these strategies form a multilayered prevention system that addresses both individual and community conditions [

27].

5. Conclusions

Spatial epidemiology provides a strong foundation for strengthening prevention across clinical, public health, and community systems by integrating geographic, ecological, environmental, and temporal determinants into a unified analytic approach. By revealing localized vulnerability patterns and structural contributors to preventable harm, spatial analyses support earlier detection of emerging risk and more precise allocation of prevention resources. Integrating geocoded indicators into assessment and decision-support processes enhances trauma-informed screening, improves safety planning, and aligns prevention activities with the lived environments in which people experience risk.

As prevention systems increasingly acknowledge the importance of place-based determinants, combining spatial epidemiology with behavioral theory and the Socioecological Model offers a comprehensive framework for addressing complex public health challenges. This approach aligns with contemporary precision public health priorities that emphasize actionable, high-resolution data to guide equitable and timely interventions [

4]. The methodological architecture presented here is adaptable to national datasets, institutional settings, and municipal jurisdictions, establishing a flexible foundation for future empirical analyses using high-resolution or restricted geographic datasets. Emerging research further underscores that geographic context shapes health opportunity, service access, and environmental exposure pathways [

27], reinforcing the importance of incorporating spatial intelligence into population health and community safety initiatives. By embedding spatial insights across clinical and community domains, organizations can strengthen their capacity to anticipate risk, reduce preventable harm, and implement coordinated and contextually responsive prevention strategies.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Violence Prevention; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564793 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Rushton, G. Public health, GIS, and spatial analytic tools. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2003, 24, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, P.; Wartenberg, D. Spatial epidemiology: current approaches and future challenges. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004, 112, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, M.J.; Iademarco, M.F.; Riley, W.T. Precision public health for the era of big data. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. National Crime Victimization Survey: Technical Documentation and Codebook; U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, latest ed. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/programs/ncvs (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Anselin, L. Thirty years of spatial econometrics. Papers Reg. Sci. 2010, 89, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Earls, F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997, 277, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, L.E.; Felson, M. Social change and crime rate trends: a routine activity approach. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1979, 44, 588–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, T.D. Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design, 2nd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, E.A.; Bowen, S.K.; Bowen, L.M. Neighborhood disadvantage, collective efficacy, and exposure to violence. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 62, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg, L.L.; Krug, E.G. Violence as a global public health problem. Cien. Saude Colet. 2006, 11, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N. Epidemiology and the People’s Health: Theory and Context; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vest, J.R.; Issel, L.M. Data sharing in public health: an analysis of perceived barriers and proposed solutions. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2014, 20, 420–427. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.; et al. Confidentiality, data suppression, and the challenge of spatial analysis in public-use datasets. Stat. Public Policy 2018, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Defense Health Care: Actions Needed to Define and Sustain Wartime Medical Skills for Enlisted Personnel. GAO-21-337, 2021. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-337 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Sherman, J.E.; Spencer, J.; Preisser, J.S.; Gesler, W.M.; Arcury, T.A. A suite of methods for representing activity space in a healthcare accessibility study. Health Place 2005, 11, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, R.A.; et al. Data needs for public health decision making. Public Health Rep. 2017, 132, 311–314. [Google Scholar]

- Beeber, A.S.; et al. Using restricted-access microdata for health research: opportunities and challenges. Ann. Epidemiol. 2020, 44, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Buckeridge, D.L. Outbreak detection through automated surveillance: a review of the determinants of detection. J. Biomed. Inform. 2007, 40, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getis, A.; Ord, J.K. The analysis of spatial association by use of distance statistics. Geogr. Anal. 1992, 24, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Brunsdon, C.; Fotheringham, A.S.; Charlton, M.E. Geographically weighted regression: a method for exploring spatial nonstationarity. Geogr. Anal. 1996, 28, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, U.A.; Parker, V.G.; Fentress, T. Safety planning with intimate partner violence survivors in the emergency department: a pilot study. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2017, 43, 560–567. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue, A.K.; Tuohy, R.V. Lessons we don’t learn: a study of the lessons of disasters, why we repeat them, and how we can learn them. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 822–834. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington, D.P.; Welsh, B.C. Effects of improved street lighting on crime: a systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2008, 4, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez Roux, A.V. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am. J. Public Health 2001, 91, 1783–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).