Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

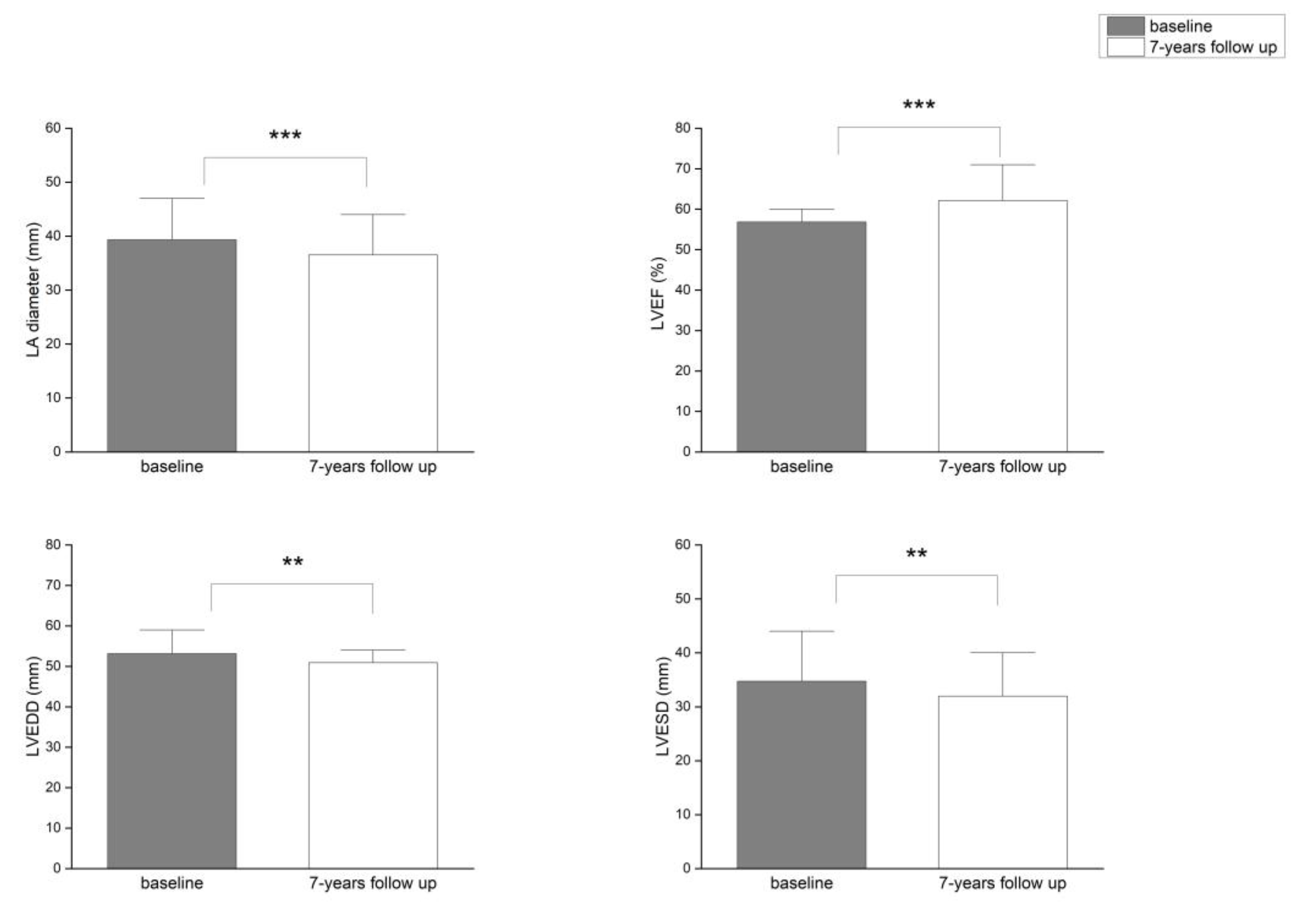

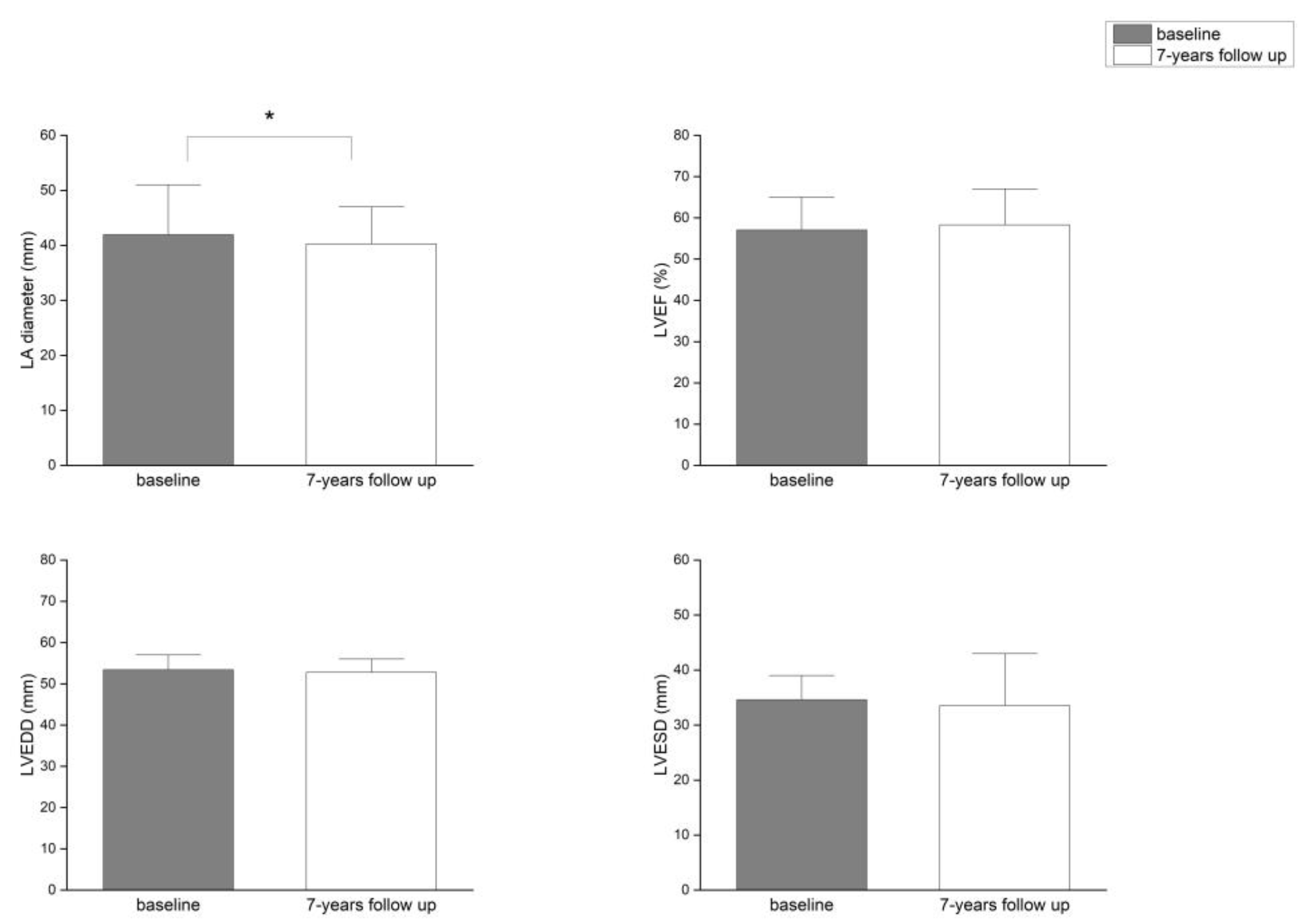

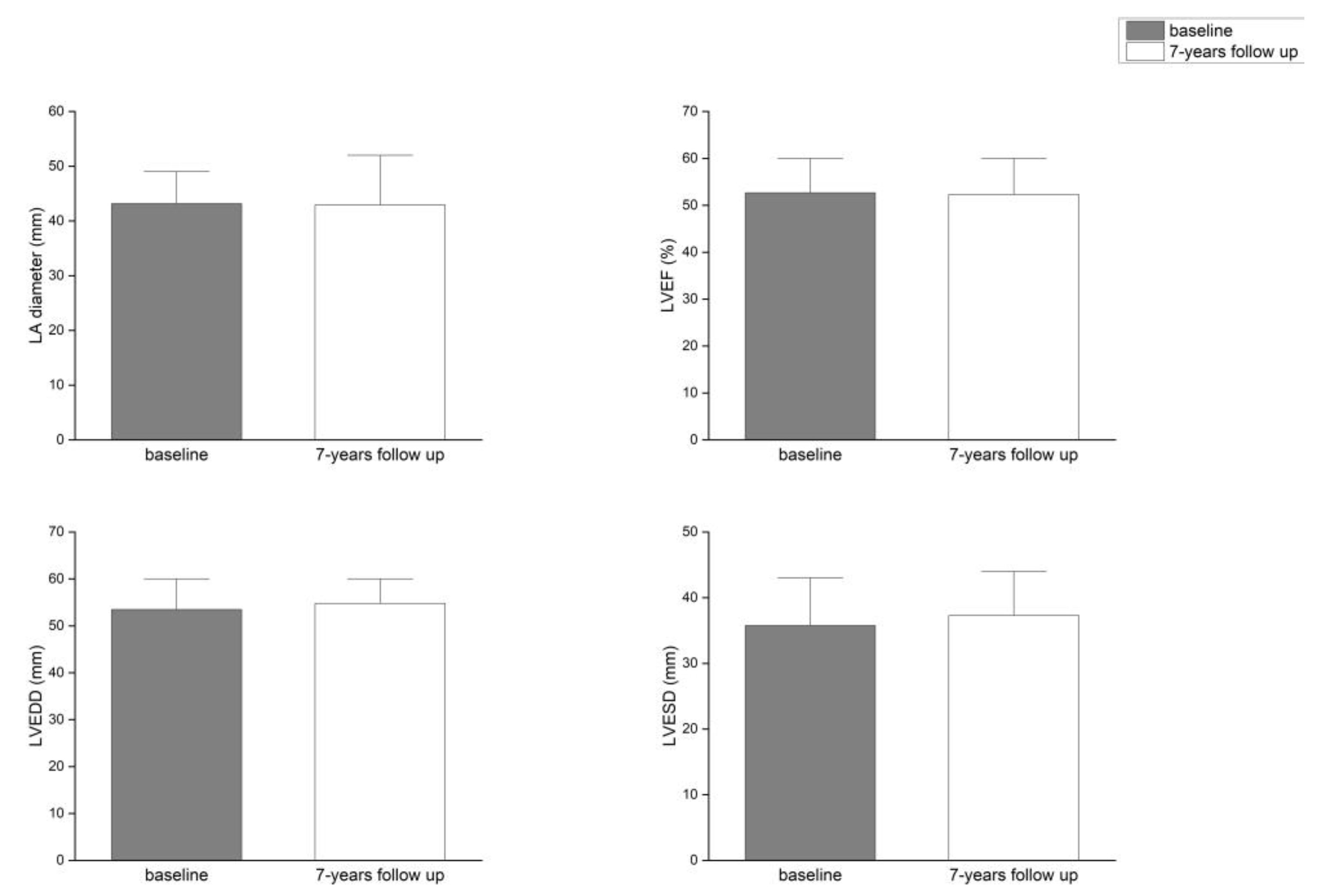

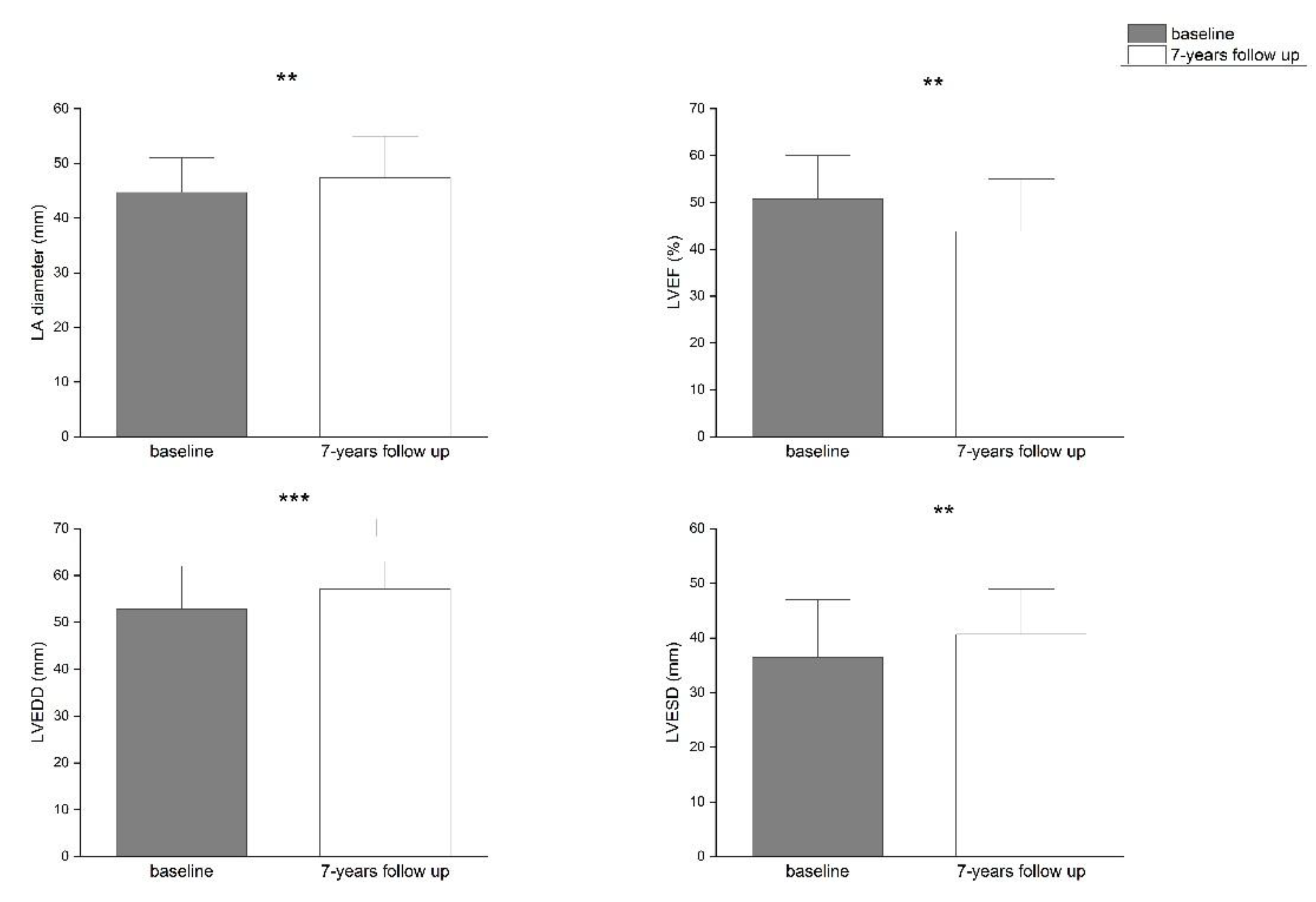

Background/Objectives: Atrial fibrillation (AF) is closely associated with adverse remodeling of the left atrium (LA). This study evaluated the impact of LA diameter on long-term outcomes following radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the pulmonary veins and assessed LA and left ventricular (LV) remodeling over a seven-year follow-up period. Methods: A total of 117 patients with symptomatic, drug-refractory AF underwent RFA. Structural remodeling was evaluated using echocardiography. Long-term outcomes were categorized using the Pulmonary Vein Isolation Outcome Degree (PVIOD), a four-level classification reflecting procedural and clinical success. Results: After seven years, 32.5% of patients who achieved successful sinus rhythm maintenance after a single RFA (PVIOD 1) demonstrated significant reverse remodeling of LA and LV. LA diameter decreased from 39.3±0.6 mm to 36.5±0.6 mm (p=0.0007); LV end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) from 53.1±0.6 mm to 50.9±0.7 mm (p=0.008); LV end-systolic diameter (LVESD) from 34.7±0.8 mm to 32.0±0.1 mm (p=0.005); and LV ejection fraction (LVEF) increased from 56.8±0.8% to 62.1±1.1% (p=0.000008). Among patients with long-term success after multiple procedures (PVIOD 2; 29.1%), LA diameter decreased significantly from 41.9±0.7 mm to 40.2±0.6 mm (p=0.04), without significant ventricular changes. Patients achieving clinical success (PVIOD 3; 14.5%) showed no significant structural changes. Those with procedural and clinical failure (PVIOD 4; 23.9%) exhibited progressive negative remodeling: LA diameter increased from 44.7±0.7 mm to 47.4±0.7 mm (p=0.006); LVEDD from 52.8±0.9 mm to 57.1±0.6 mm (p=0.0006); LVESD from 36.5±1.1 mm to 40.7±1.2 mm (p=0.006); and LVEF decreased from 50.7±1.7% to 43.8±1.8% (p=0.004). Conclusions: Early and successful single RFA performed in patients with normal LA diameter is associated with complete reverse remodeling and prevention of AF recurrence. As LA size increases, the likelihood of achieving durable procedural success decreases, emphasizing the importance of timely intervention before significant left atrial enlargement develops.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population

2.2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Catheter Ablation Procedures

2.3.2. Follow-Up Protocol

2.3.3. Echocardiographic Assessment

2.3.4. Pulmonary Vein Isolation Outcome Degree (PVIOD) Classification

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Gelder CI, Rienstra M, Bunting VK, Casado-Arroyo R, Caso V, De Potter JRT, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2024;00:1-101.

- Tops FL, Bax JJ, Zeppenfeld K, Jongbloed RMM, E van der Wall E, Schali JM. Effect of radiofrequency catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation on left atrial cavity size. Am J Cardiol 2006;97(8):1220-2.

- Beukema WP, Elvan A, Sie HT, Misier ARR, Wellens HJJ. Successful radiofrequency ablation in patients with previous atrial fibrillation results in a significant decrease in left atrial size. Circulation 2005;112:2089-95.

- Inciardi MR, Bonelli A, Biering-Sorensen T, Cameli M, Pagnesi M, Mario Lombardi C, et al. Left atrial disease and left atrial reverse remodeling across diferent stages of heart failure development and progression: a new target for prevention and treatment. Eur J Heart Fail 2022;24(6):959-75. [CrossRef]

- Meris A, Amigoni M, Uno H, Thune JJ, Verma A, Kober L, et al. Left atrial remodeling in patients with myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfuction, or both: the VALIANT Echo study. Eur Heart J 2009;30:56-65.

- Jurcevic R, Angelkov L, Tasic N, Tomovic M, Kojic D, Otasevic P, Bojic M. Pulmonary Vein Isolation Outcome Degree Is a New Score for Efficacy of Atrial Fibrillation Catheter Ablation. J Clin Med 2021;10, 5827.

- Oka T, Tanaka K, Ninomiya Y, Hirao Y, Tanaka N, Okada M, et al. Impact of baseline left atrial fucion on long-term outcome after catheter ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Cardiol 2020;75(4):352-9.

- Kistler MP, Chieng D, Sugumar H, Ling L, Segan L, Azzopardi S, et al. Effect of Catheter Ablation Using Pulmonary Veiv Isolation With vs Without Posterior Left Atrial Wall Isolation on Atrial Arrhythmia Recurrence in Patients With Persistent Atrial Fibrillation. The CAPLA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023;329(2):127-325.

- Crea F. Spotlight on hot topics: subclinical atrial fibrillation, risk stratification on channelopathies, and cardioprotection. Eur Heart J 2024;45:2579-83.

- Tops LF, Delgado V, Bertini M, Marsan NA, Den Uijl DW, Trines SAIP, et al. Left atrial strain predicts reverse remodeling after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:324-31.

- Pathak R, Lau HD, Mahajan R, Sanders P. Structural and Functional Remodeling of the Left Atrium: Clinical and Therapeutic Implications for Atrial Fibrillation. J Atr Fibillation 2013;6(4):986-98.

- Casaclang-Verzosa G, Gersh JB, Tsang SMT. Structural and Functional Remodeling of the Left Atrium. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51(1):1-11.

- Westenberg JJM, van der Geest RJ, Lamb HJ, Versteegh MIM, Braun J, Doornbos J, et al. MRI to evaluate left atrial and ventricular reverse remodeling after restrictive mitral annuloplasty in dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2005;112(9 Suppl):I437-42. I: Suppl).

- Gelsomino S, Lucà F, Rao CM, Parise O, Pison L, Wellens F, et al. Improvement of left atrial function and left atrial reverse remodeling after surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2014;3:70-4.

- Mathias A, Moss AJ, McNitt S, Zareba W, Goldenberg I, Solomon SD, et al. Clinical implications of complete left-sided reverse remodeling with cardiac resynchronization therapy: a MADIT-CRT substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:1268-76.

- Sunaga A, Hikoso H, Tanaka N, Masuda M, Witanable T, Inoue K, et al. Predictors of left ventricular reverse remodeling after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: sub analysis of randomized controlled EARNEST-PVI trial. Eur Heart J 2023;44(Suppl2). [CrossRef]

- Okada M, Tanaka N, Oka T, Tanaka K, Ninomiya Y, Hirao T, et al. Clinical significance of left ventricular reverse remodeling after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Cardiol 2021;77(5):500-8. [CrossRef]

- Dujardin SK, Enriquez-Sarano M, Rossi A, Bailey RK, Seward BJ. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular remodeling: Are left ventricular diameters suitable tools? J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;30(6):1534-41.

- Kim S, Park S, Cho H, Cho Y, Oh Y, Kim Y, et al. Left ventricular remodeling after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: changes of myocardial extracellular volume fraction by cardiac MRI. Investig Magn Reson Imaging 2022;26(3):151-60. [CrossRef]

- Nadal-Ginard B, Kajstura B, Leri A, Anversa P. Myocyte death, growth, and regeneration in cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Circ Res 2003;7;92(2):139-50. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt B, Coats AJS, Tsutsui H, Abdelhamid CM, Adamopoulos S, Albert N, et al. Universal definition and classification of heart failure: a report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure: Endorsed by the Canadian Heart Failure Society, Heart Failure Association of India, Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zeland, and Chinese Heart Failure Association. Eur J Heart Fail 2021;23:352-80.

- Kloosterman M, Rienstra M, Mulder BA, Van Gelder IC, Maass AH. Atrial reverse remodelling is associated with outcome of cardiac resynchronization therapy. Europace 2016;18:1211-9.

- Marrouche NF, Brachmann J, Andresen D, Siebels J, Boersma L, Jordaens L, et al.; CASTLE-AF Investigators. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2018;378:417-27.

- Packer DL, Mark DB, Robb RA, Monahan KH, Bahnson TD, Poole JE, et al.; CABANA Investigators. Effect of catheter ablation vs antiarrhythmic drug therapy on mortality, stroke, bleeding, and cardiac arrest among patients with atrial fibrillation: the CABANA randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;321:1261-74.

- Kirchof P, Camm J, Goette MD, Brandes MD, Eckardt L, Elvan A, et al.; EAST-AFNET 4 Investigators. Early Rhythm-Control Therapy in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1305-16. [CrossRef]

- Jurcevic R, Angelkov L, Jakovljevic V, Grujic Milanovic J, Tomovic M, Kojic D, Ristic V, Vukajlovic D, Grbovic A, Babic M, Susic M, Otasevic P, Tasic N, Bojic M. Left atrial and left ventricular positive and negative remodeling after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. European Heart Journal 2024;45(Suppl.1). [CrossRef]

- Kalman JM, Al-Kaisey AM, Parameswaran R, Hawson J, Anderson RD, Lim M, et al. Impact of early vs. delayed atrial fibrillation catheter ablation on atrial arrhythmia recurrences. Eur Haert J 2023;44:2447-54. [CrossRef]

- Teunissen C, Kassenberg W, van der Heijden JF, Hassink RJ, van Driel VJ, Zuithoff NP, et al. Five-year efficacy of pulmonary venous antrum isolation as a primary ablation strategy for atrial fibrillation: A single-centre cohort study. Europace 2016;18:1335-42.

- Ouyang F, Tilz R, Chun J, Schmidt B, Wissner E, Zerm T, et al. Long-Term Results of Catheter Ablation in Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation: Lessons from a 5-year follow-up. Circulation 2010;122:2368-77.

- Lang MR, Badano PL, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendationes for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28(1):1-39. [CrossRef]

- Pannone L, Mouram S, Giovani Della Rocca D, Sorgente A, Monaco C, Del Monte A, et al. Hybrid atrial fibrillation ablation: long-term outcomes from a single-centre 10-year experience. Europace 2023;25:1-9. [CrossRef]

- De Raffele M, Teis A, Cediel G, Weerts J, Conte C, Juncà G, et al. Left atrial remodeling and function in various left ventricular hypertrophic phenotypes. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2025;26(5):853-62. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi T. Atrial structural remodeling and atrial fibrillation substrate: A histopathological perspective. Journal of Cardiology 2025;85(2):47-55.

- Xu T, Hu H., Zhu R, Hu W, Li X, Shen D, et al. Ultrasound assessment of the association between left atrial remodeling and fibrosis in patients with valvular atrial fibrillation: a clinical investigation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2025;25,149.

| Parameter | PVIOD 1 (n=38) | PVIOD 2 (n=34) | PVIOD 3 (n=17) | PVIOD 4 (n=28) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| baseline | after 7 years | baseline | after 7 years | baseline | after 7 years | baseline | after 7 years | |

| LAD (mm) | 39.32±0.62 | 36.53±0.59 | 41.94±0.75 | 40.26±0.56 | 43.18±0.92 | 42.94±0.97 | 44.68±0.74 | 47.39±0.75 |

| p-Value | 0.000749 | 0.044408 | 0.444593 | 0.005874 | ||||

| LVEF (%) | 56.84±0.76 | 62.11±1.08 | 57.06±0.97 | 58.29±1.02 | 52.63±1.49 | 52.29±1.76 | 50.71±1.68 | 43.82±1.81 |

| p-Value | 8.32686E-05 | 0.192093 | 0.43968 | 0.003668 | ||||

| LVEDD (mm) | 53.10±0.64 | 50.89±0.66 | 53.44±0.46 | 52.76±0.58 | 53.47±0.81 | 54.76±0.73 | 52.85±0.89 | 57.07±0.63 |

| p-Value | 0.007842 | 0.201137 | 0.200228 | 0.000598 | ||||

| LVESD (mm) | 34.74±0.81 | 31.97±0.09 | 34.62±0.68 | 33.56±0.67 | 35.76±1.21 | 37.29±1.24 | 36.46±1.13 | 40.68±1.21 |

| p-Value | 0.005266 | 0.13287 | 0.178529 | 0.005609 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).