1. Introduction

Primary bone sarcomas (BS) are rare diseases, accounting for approximately 0.2% of all cancer cases [

1,

2]. Osteosarcoma is the most common and aggressive primary bone tumor, most often affecting the long tubular bones (femur, tibia, humerus) in adolescents [

1,

3]. Resistance to chemotherapy and a high metastatic potential [

4] characterize this disease. As results, despite complex treatment (chemotherapy, radiation therapy, surgery), the average 5-year survival rate of patients with osteosarcoma is approximately 68% and depends on the stage (74% for localized processes, 27% for metastases) [

1,

5]. Chondrosarcomas are tumors of cartilaginous tissue that occur mainly in adults (40-75 years old), are characterized by heterogeneity and are characterized by a high risk of metastasis to the lungs [

2]. Survival rates for chondrosarcoma vary widely and depend on the stage of the disease too (the 10-year survival rate for stage I (highly differentiated form) is 90%, while for stage IV (dedifferentiated form with metastases) it is less than 10% [

6,

7]).

Monitoring the patient’s condition during and after treatment is crucial for timely adjustment of therapy. Currently, both radiographic imaging methods (MRI, single-photon emission computed tomography, SPECT-CT, X-ray examination) and histological analyses of patient biopsies are used for this purpose in primary BS [

8]. Despite the high level of development of instrumental and laboratory methods, as well as the improvement of technical equipment in clinics, each of the methods has disadvantages: limited visualization capabilities, high invasiveness, traumatic nature, and the lack of immunohistochemical markers specific to this type of cancer [

9]. Moreover, a serious disadvantage of biopsy is that this method does not reflect tumor heterogeneity [

10,

11]. At the same time, the undeniable advantage of “liquid biopsy” is its low invasiveness, the possibility of dynamic monitoring of patients during the antitumor therapy, and the ability to capture the tumor’s heterogeneous molecular profile [

12]. Therefore, the search for tumor markers for liquid biopsy in BS is a particularly pressing issue.

A promising source of tumor markers are exosomes— small extracellular vesicles (EVs) measuring 30–150 nm, secreted by all cells of the body into the extracellular space [

13,

14]. Exosomes ensure the stability of the transferred signaling molecules [

15], thereby facilitating effective intercellular communication. In malignant neoplasms, the number of secreted exosomes increases, and their transfer of molecular cargo to other cells can be accompanied by a carcinogenesis-stimulating effect [

16,

17]. Since exosomes contain biopolymers that reflect the composition of the parent cell, these vesicles can be used as a source of tumor markers for liquid biopsy. In particular, tumor-derived exosomes carry tumor-associated microRNAs [

18,

19]. It is known that microRNAs can influence both oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, influencing various aspects of tumor occurrence, progression, and metastasis. Numerous studies have highlighted the high potential of microRNAs as biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of malignant neoplasms, as well as for assessing the effectiveness of antitumor therapy [

20,

21]. However, research on the development of microRNA panels for the diagnosis and assessment of the effectiveness of antitumor therapy for BS is extremely limited [

22,

23].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Treatment

The study included 10 patients with primary BS (6 patients with osteosarcomas and 4 patients with chondrosarcomas of varying degrees of malignancy, 5 men and 5 women) with tumor localization in the long tubular bones of the extremities. The median age of the patients was 39 years, mean age – 39.5 years (

Table 1).

Criteria for inclusion of patients in the study: age over 18 years; primary bone sarcoma, T1-3N0M0-1G1-3; sufficient amount of supporting tissue in the thermal ablation zone; the patient’s ability to undergo all diagnostic manipulations; written informed consent of the patient.

Radiation therapy was not performed in the patients with BS. Blood samples from all enrolled patients were collected before therapy. All patients received treatment in the form of radical intraoperative thermal ablation in combination with perioperative chemotherapy according to ESMO clinical guidelines [

24]. Removal of the extraosseous component of the tumor was performed according to indications. Thermal ablation was performed using the Phoenix-2 local hyperthermia complex, which has a wide temperature range and allows for the creation of various therapeutic effect modes (registration certificate of Roszdravnadzor No. RZN 20117/6236 dated 09/08/2017; declaration of conformity ROSS RU D-RU.RA01.B.00486/23 dated 01/16/2023). To generate thermal waves, direct current was used, which flowed through the heating element, forming a temperature from 45 to 110°C, which allows the equipment to be used for both local hyperthermia and thermal ablation. Temperature monitoring during thermal ablation was performed using a temperature sensor placed in the bone marrow canal at the epicenter of the hyperthermic zone.

The anatomical structure and metabolic activity of bone tissue in the thermal ablation area, as well as signs of recurrence and metastasis, were assessed using radiographic, computed tomography, ultrasound, and single-photon emission computed tomography imaging of bone lesions with 99mTc-pyrophosphate. The studies were performed dynamically before surgery and 9 months afterward.

The comparison group consisted of 14 healthy individuals (4 men and 10 women, median age of patients was 44 years, mean age was 41.7 years), examined on an outpatient basis at the E.N. Meshalkin National Medical Research Center.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Cancer Research Institute of the Tomsk National Research Medical Center (protocol No. 3 dated January 18, 2023) and by the Ethics Committee of the E.N. Meshalkin National Medical Research Center (protocol No. 3 dated September 17, 2024). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

2.2. Isolation and Characterization of Exosomes

Exosomes from blood plasma (from 9 mL of venous blood) from all individuals were isolated using ultrafiltration with ultracentrifugation as described previously [

16]. Exosome samples (in 250 μL of PBS) were aliquoted, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C. The aliquots were thawed once before use.

Patient’s blood samples were collected before and 9 months after therapy.

The size and concentration of exosomes were determined by Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) using the NanoSight NS300 (Malvern, UK) as described previously [

16].

Quantitative analysis of the exosomal tetraspanines on the surface of the isolated EVs was carried out using flow cytometry as described previously [

16]. Flow cytometry was performed on the Cytoflex (Becman Coulter, BioBay, Jiangsu, China), using CytExpert 2.4 Software. The MFI of stained exosomes was analyzed and compared to the isotype (BD bioscience, Heidelberg, Germany) and negative controls.

2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

The role of the tumor-associated microRNAs miR-101 and -92 selected for study in the BS pathogenesis was determined using the DIANA database (

https://dianalab.ece.uth.gr), which contains information about microRNA target genes, as well as the processes and pathways in which they participate (

https://dianalab.ece.uth.gr). Interactions between proteins encoded by the target genes were analyzed using the STRING database (

https://string-db.org).

2.4. Evaluation of miRNA Concentrations

Before the isolation of miRNA, samples of exosomes were thawed on ice and gently mixed. RNA was isolated from exosomes, obtained from 3 mL of blood (for the analysis of three miRNAs) using miRNA Isolation Kit (Biosilica, Russia) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, precipitated with glycogen and isopropanol, and reconstituted in 35 μL of water [

25]. The purity of isolated RNA was determined by OD260/280 using a Nanodrop ND-1000 (Thermo Scientific, MA). The quality of exosomal RNAs was evaluated using an “High Sensitivity RNA Kit” and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyser

TM (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) in SB RAS Genomics Core Facility (ICBFM SB RAS, Russia).

Reverse transcription on microRNA templates was performed as described [

25]. Samples without RNA templates were used as negative controls.

Real-time PCR was carried out on the LightCycler 480 II detection system (Roche, Switzerland) as described earlier [

25]. All reactions were carried out in duplicate. The relative expression values of target microRNAs were normalized to miR-16 and were calculated following the ΔΔCt method, as described previously [

25].

2.5. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 10.0 software. Each data set was first tested for a Gaussian distribution by using a Shapiro-Wilk normality test. All data were expressed as medians with interquartile ranges or as means with standard errors. To evaluate the difference, Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test were used. Correlation analysis on data was carried out with Spearman Rank Correlation test. p-values<.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Bioinformatic Analysis

It is known, that microRNAs involved in cancerogenesis are not specific to a single cancer type. This is a problem of developing a highly specific diagnostic system, but it is an advantage for developing a universal marker of anticancer therapy effectiveness. For this reason, we selected tumor-associated microRNAs -92a and -101 based on literature data. It has been shown in various cell models and clinical samples of tumors that these microRNAs are involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), as well as in the regulation of apoptosis, proliferation and angiogenesis, and are involved in cell migration and metastasis [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

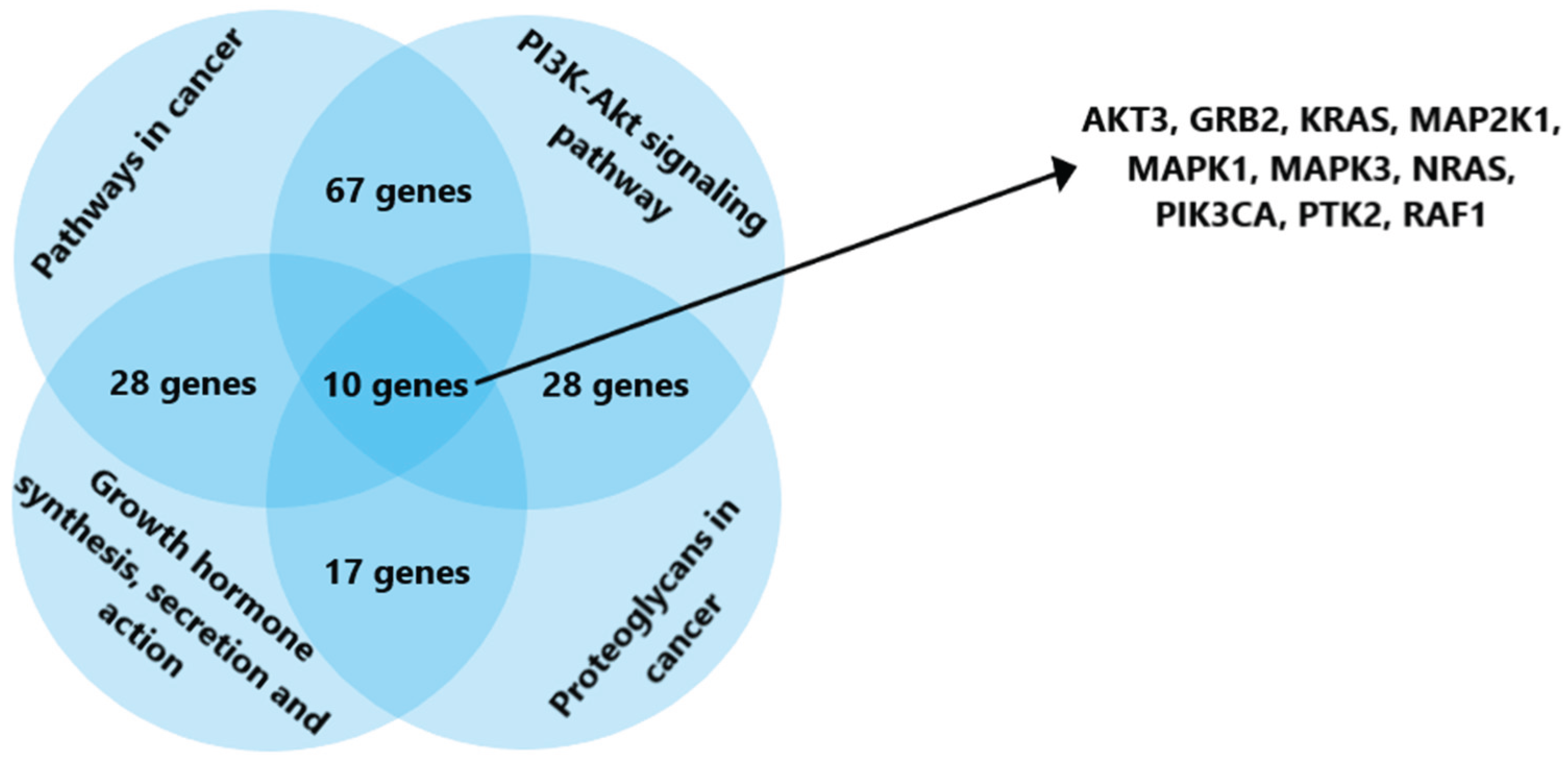

To identify the processes in which these microRNAs are involved, a bioinformatics analysis was performed. Using the DIANA database (

https://dianalab.e-ce.uth.gr/), genes regulated by the selected microRNAs, as well as the processes in which they are involved, were identified. Among the many metabolic pathways associated with the activity of microRNAs -92a and -101, the following were selected for further analysis: carcinogenesis signaling pathways, the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, signaling pathways involving proteoglycans in cancer, as well as the pathways of synthesis, secretion, and action of growth hormone. The last pathway was chosen due to the fact that numerous literary data indicate the influence of growth factors on the development of osteogenic sarcomas [

31]. This is confirmed by the frequency of occurrence of this type of malignant neoplasms in adolescents during active growth, as well as their location in the bone metaphysis [

32]. As a result of bioinformatics analysis, 10 genes involved in all the pathways under consideration were identified: AKT3, GRB2, KRAS, MAP2K1, MAPK1, MAPK3, NRAS, PIK3CA, PTK2, RAF1 (

Figure 1).

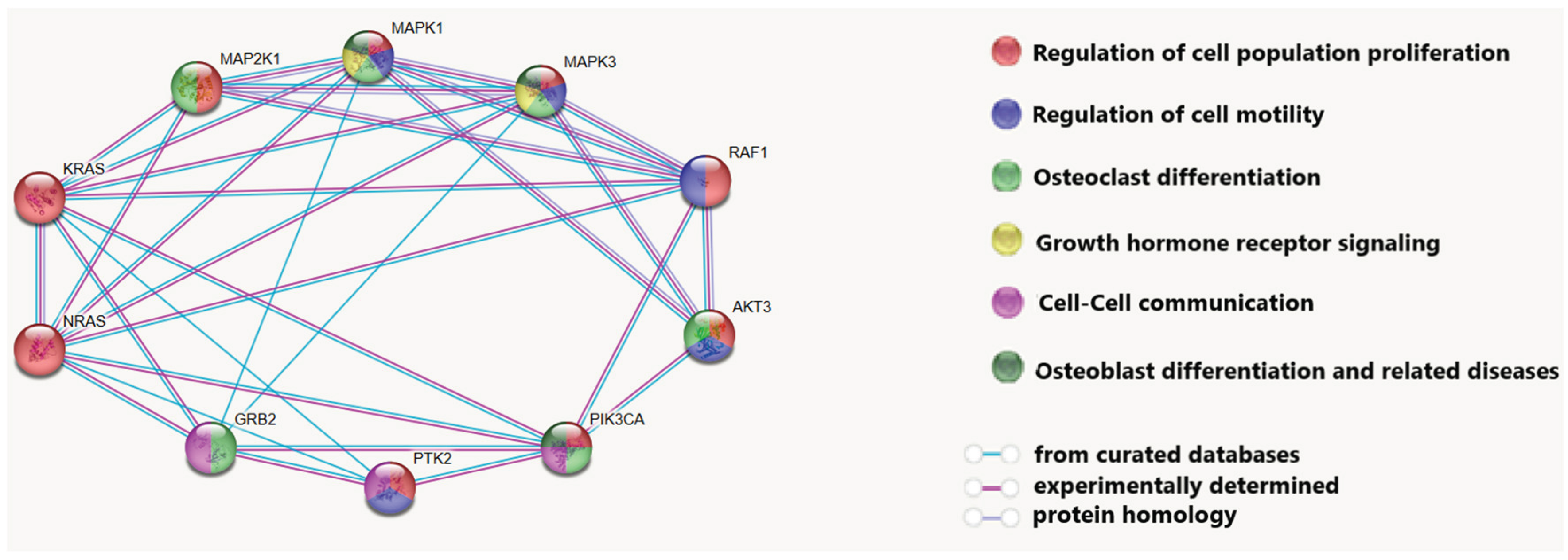

Using STRING software (

https://string-db.org/), a network of interactions between the proteins encoded by these genes was constructed, and the processes in osteogenic tumor carcinogenesis in which they are involved were demonstrated (

Figure 2).

It was revealed that these proteins are involved in processes such as the regulation of cell proliferation and motility, intercellular communication, osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation, and the growth hormone receptor signaling cascade. The involvement of the analyzed proteins in the cellular response to growth hormone is of great importance in the development of BS: it is known that the number of IGF1 receptors can increase in osteosarcoma cells, and the growth hormone signaling cascade directly influences the production of this protein [

33]. Differentiation between osteoclasts and osteoblasts is directly related to the development of osteogenic sarcomas. Dysregulation of this process leads to the formation of tumors [

34], and high osteoclast activity is associated with an aggressive course of the disease [

35].

Thus, bioinformatics analysis showed that tumor-associated microRNAs (miR-92a and miR-101) selected from literature data are involved in the regulation of key processes in BS carcinogenesis and are promising markers for the development of a method for assessing antitumor therapy.

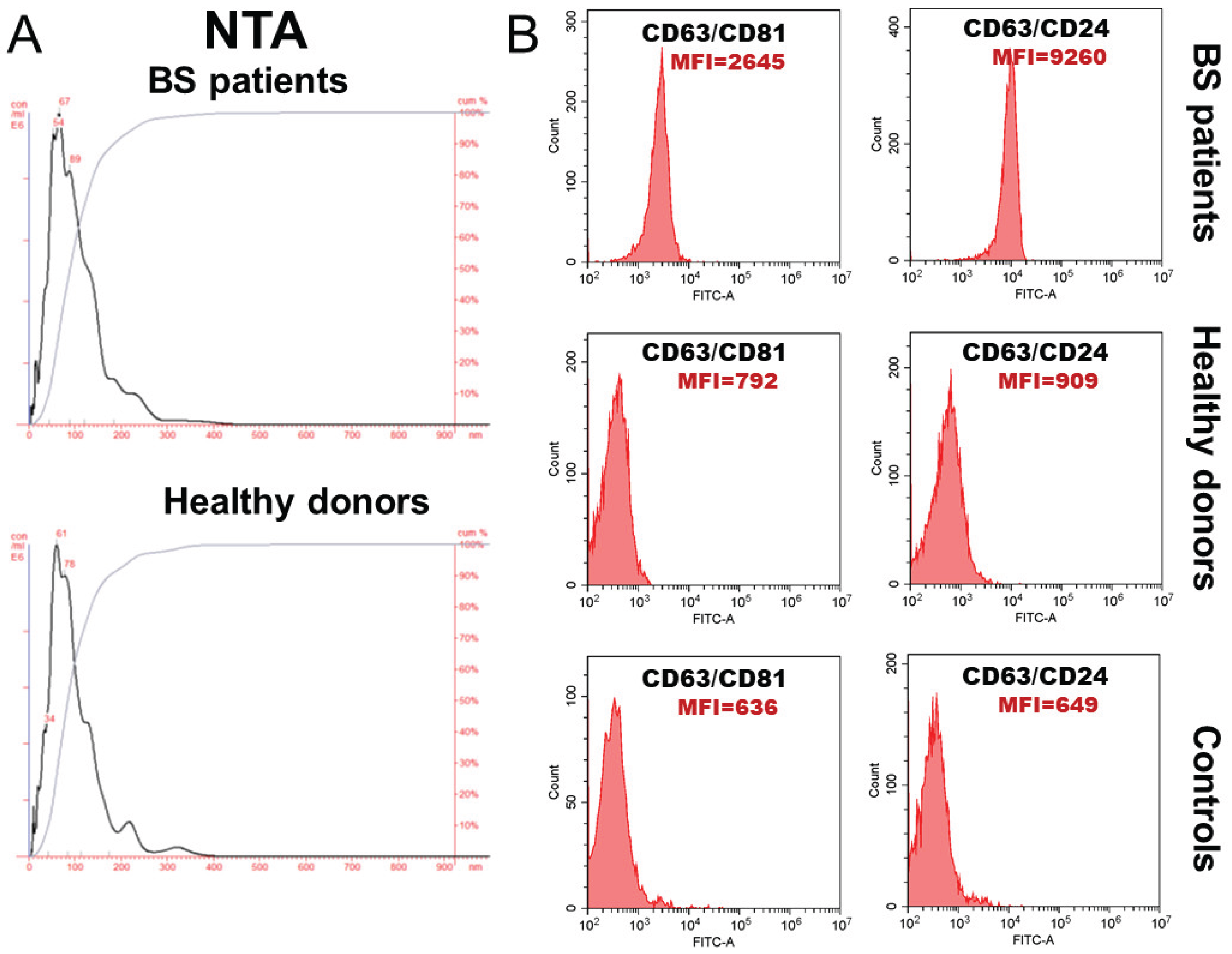

3.2. Characterization of Exosomes

Exosomes from BS patients and healthy individuals were isolated from blood using a combination of ultrafiltration and ultracentrifugation. Nanoparticle trajectory analysis revealed that the isolated vesicles were predominantly smaller than 120 nm and expressed classic exosomal markers—tetraspanins CD63 and CD81, and the glycoprotein CD24 (

Figure 3).

According to NTA analysis, the average concentration of circulating exosomes in patients with BS and healthy individuals did not differ significantly and was 25.1±2.33×10

9 and 24.0±4.92×10

9 EVs/ml of blood, respectively. The average EV size in healthy individuals was 95.3±11.1 nm, and in cancer patients - 96.2±9.70 nm (

Figure 3).

CD81 expression on CD63-positive exosomes from patients with BS was more than threefold higher than that on exosomes from healthy donors, while CD24 expression on CD63-positive exosomes was more than tenfold higher, which is a characteristic of these patients.

3.3. Expression of miR-92a and miR-101 in Exosomes from Plasma of Patients with Primary BS

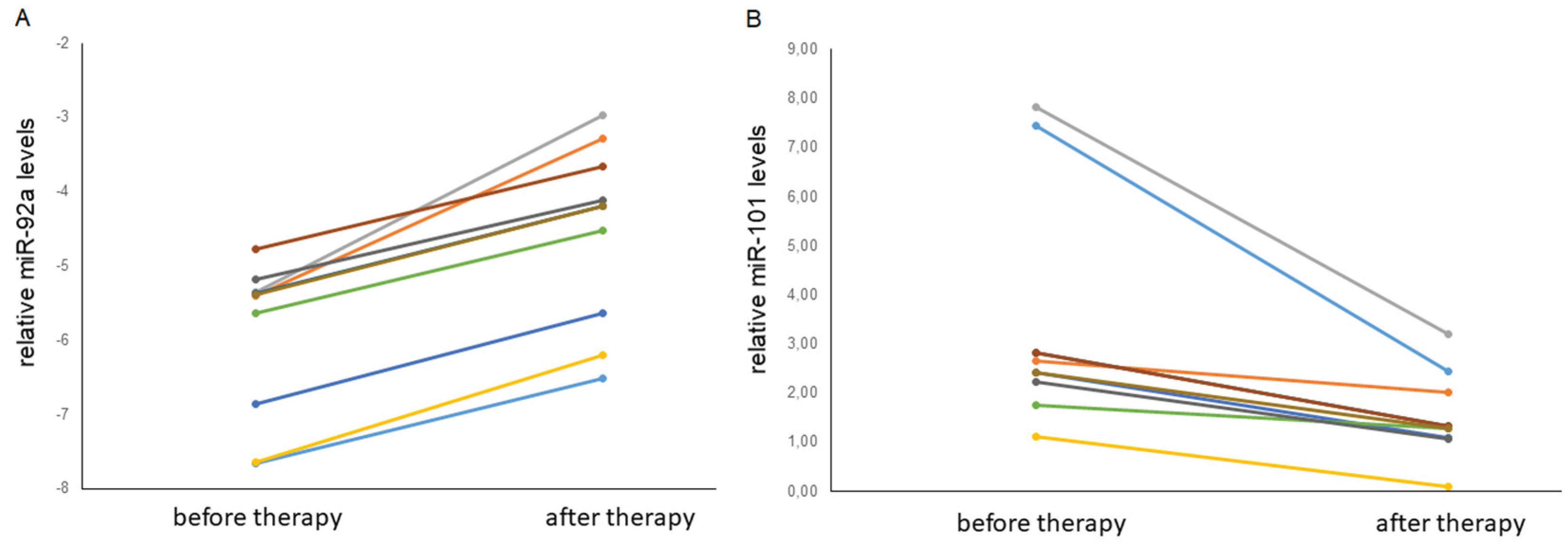

To determine correlations between changes in the relative levels of miR-92a and miR-101 and treatment efficacy, blood samples from patients with chondrosarcoma and osteosarcoma were obtained before surgery with thermal ablation followed by chemotherapy, as well as 9 months after radical thermal ablation. The average follow-up period was 24±5 months. No signs of disease progression were detected during the follow-up period.

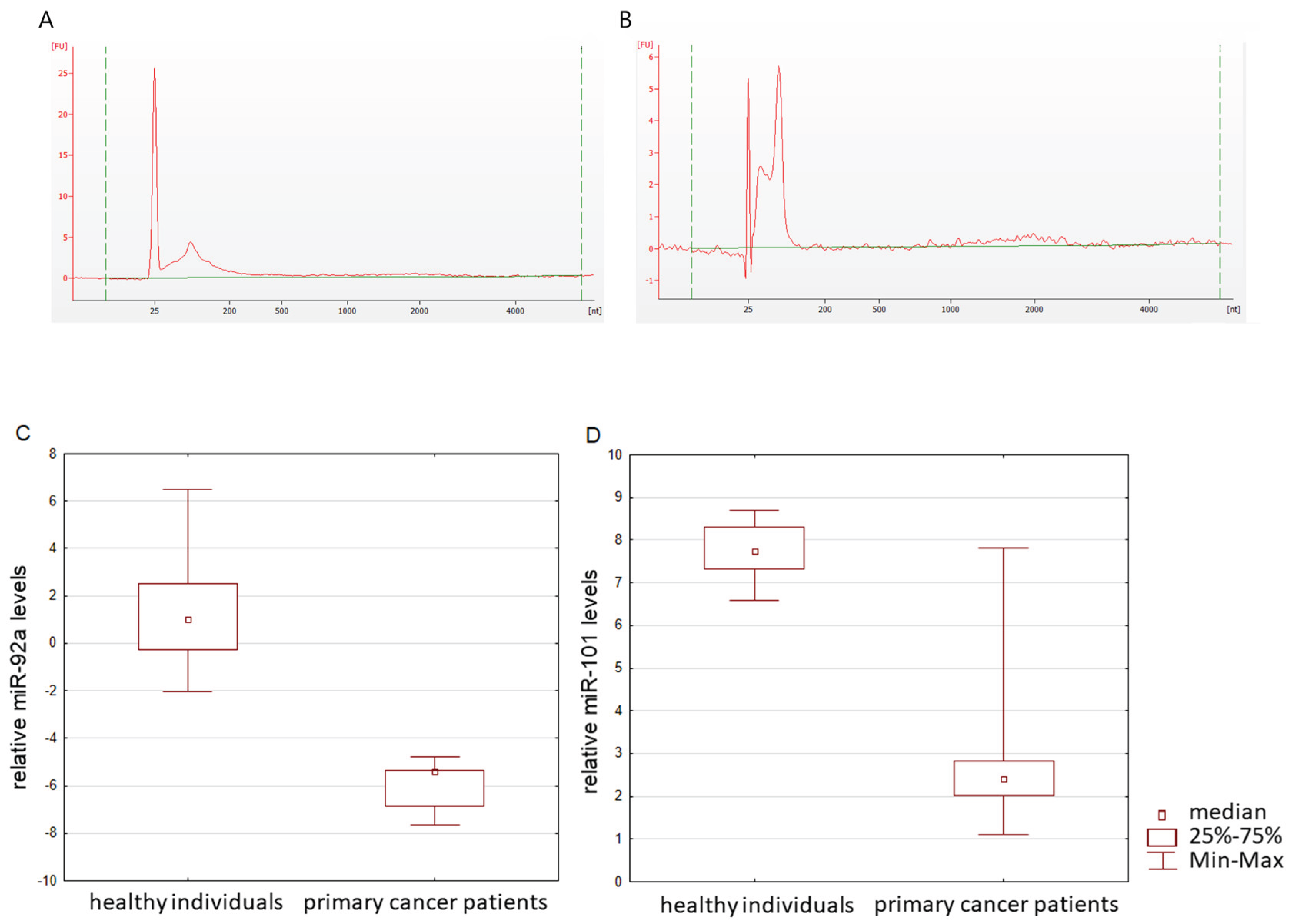

Bioanalyzer trace analysis revealed an abundant presence of RNA up to 150 nucleotides in size in exosomes from all sources (

Figure 4a,b).

Quantification of miR-92a and miR-101 was performed using reverse transcription followed by real-time PCR, based on the calculation of target RNA in exosomes per 1 ml of blood.

Since the miR-16-5p expression was stable and reproducible, it was chosen as an endogenous control to normalize the miRNA expression [

36,

37]. For microRNAs, qRT-PCR assays with a working range of 24–39 threshold cycles (Ct) of PCR were used. Non-template controls produced no signal or were at least ten cycles away from the minimum detectable amount of specific template. All the reported data were obtained using RNA samples that produced Ct values within the working range of the systems. Data on the miRNA relative expression in exosomes from the blood plasma of healthy individuals and patients with BS are presented in

Figure 4c, d. It was shown that the level of miR-92a and the level of miR-101 statistically significantly differ in the blood plasma exosomes of healthy donors and primary cancer patients (

p = 0.000001 and

p = 0.0076, respectively). Moreover, the level of microRNA after therapy changes in different directions: the expression of miR-92 significantly (

p = 0.0257) decreases, while microRNA-101 significantly (

p = 0.0257) increases (

Figure 5. Since, according to the literature, miR-101 is a microRNA that suppresses tumor development [

38], the observed tendency for the level of this microRNA to increase after thermal ablation surgery allows us to consider miR-101 as a potential marker for assessing the effectiveness of therapy in patients with bone and cartilage sarcomas. In addition, a trend towards a decrease in the level of carcinogenesis-promoting miR-92a [

17,

39,

40] was revealed after successful antitumor therapy.

4. Discussion

Primary BS are predominantly osteosarcomas and chondrosarcomas. Osteogenic sarcomas are characterized by the development of resistance to chemotherapy [

4], while chondrosarcomas are characterized by chemo- and radioresistance [

41]. For these reasons, methods for increasing the sensitization of tumor cells to radiation therapy, such as hyperthermia [

42], have come into widespread use. Hyperthermia involves local heating of the tumor to 41–42°C, which increases its sensitivity to radiation and chemotherapy [

43]. Thermal ablation, local heating of tumor tissue to temperatures above 50°C in order to initiate apoptosis of tumor cells, is proposed as a more effective component of the complex treatment of sarcomas [

44]. According to research, thermal ablation may also be an effective method for treating bone metastases [

45]. There are several types of thermal ablation that use different energy sources to heat tissue: microwave ablation, radiofrequency ablation, laser thermal ablation, and ultrasound ablation. The first two options are the most common in clinical practice [

46]. These types of therapy are minimally invasive, minimally traumatic, do not require a long period of patient rehabilitation after surgery, and are also an alternative to surgical intervention with the possibility of dynamic procedure monitoring using CT [

47].

Exosomes, key players in intercellular communication, not only reflect the tumor’s molecular profile but also play a crucial role in metastasis, the development of therapeutic resistance, and immunosuppression [

13,

48,

49]. Their stability in biological fluids and ability to transport a variety of molecules, including microRNAs, make them a valuable tool for dynamic disease monitoring. Identifying tumor-associated microRNAs within the molecular cargo of exosomes will enable the development of panels for assessing the effectiveness of therapy using liquid biopsy. Some of the promising RNA markers may be miR-92a and miR-101. It has been shown that miR-101 has an inhibitory effect on the proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of osteosarcoma, and a low level of this microRNA in the blood serum of patients is associated with late stages of the disease and metastases in osteosarcoma [

38,

50,

51,

52]. In addition, studies on cell lines and biological materials of patients with osteosarcoma have shown an association of miR-92a with an unfavorable prognosis, and a positive effect of this microRNA on the proliferation, metastasis, and invasion of cells mimicking osteosarcoma has also been revealed [

53,

54,

55].

Since cell-free RNA is not protected from hydrolysis by blood nucleases, analyzing microRNAs within membrane vesicles—exosomes—seems more promising. This hypothesis was successfully confirmed by assessing the levels of tumor-associated microRNAs in exosomes from patients with primary BS before and after radical thermal ablation. However, implementing liquid biopsy into routine clinical practice requires addressing a number of methodological issues, including standardizing extraction methods, analysis, and data interpretation. Further research should be aimed at validating existing biomarkers, developing standardized protocols, and evaluating their clinical efficacy in large cohort studies.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that exosomal miR-92a and miR-101 levels undergo changes postoperatively in patients with osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma. The observed relationship between the expression of these microRNAs and patient outcomes suggests their potential as noninvasive monitoring markers for anti-tumor therapy by liquid biopsy. This approach, particularly valuable for patients with BS, opens up opportunities for early diagnosis of recurrence and assessment of treatment efficacy. Further studies, including larger patient cohorts and expanded microRNA analysis, are needed to validate the findings and determine the clinical significance of these proposed markers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Ch. and S.T.; methodology, A.B. and N.Yu.; investigation, A.B., N.Yu., P.S. and A.T.; resources, A.F.; data curation, A.Zh.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B, N.Yu. and S.T.; writing—review and editing, A.Ch.; project administration, A.Zh.; funding acquisition, A.Zh. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was carried out within the state assignment of Ministry of Health of Russian Federation, “Development and implementation of innovative technologies for replacing extended bone defects of long bones and the axial skeleton in clinical practice using new modular domestic-made endoprostheses for patients with cancer, orthopedic, and neurosurgical conditions”, N 123030900018-1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Cancer Research Institute of the Tomsk National Research Medical Center (protocol No. 3 dated January 18, 2023) and by the Ethics Committee of the E.N. Meshalkin National Medical Research Center (protocol No. 3 dated September 17, 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BS |

Bone sarcoma |

| EMT |

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| ESMO |

European Society for Medical Oncology |

| EVs |

Extracellular vesicles |

| MFI |

Median fluorescence intensity |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NTA |

Nanoparticle tracking analysis |

References

- Bădilă, A.E.; Rădulescu, D.M.; Niculescu, A.G.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Rădulescu, M.; Rădulescu, A.R. Recent Advances in the Treatment of Bone Metastases and Primary Bone Tumors: An Up-to-Date Review. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13(16), 4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.L.; Turner, S.P. Bone Cancer: Diagnosis and Treatment Principles. Am. Fam. Physician. 2018, 98(4), 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Rajani, R.; Gibbs, C.P. Treatment of Bone Tumors. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2012, 5(1), 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortam, S.; Lu, Z.; Zreiqat, H. Recent advances in drug delivery systems for osteosarcoma therapy and bone regeneration. Communications Materials 2024, 5(1), 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020, 70(1), 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Poulson, T.; Butler, Z.; Demetrious, M.; Gitelis, S.; Blank, A.T. Outcomes and Management of Positive Margins in Chondrosarcoma With Soft Tissue Extension: A Case Series and Review of Literature. Cancer Rep (Hoboken) 2025, 8(3), e70148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Zheng, S.; He, Q.; Li, Y. Recent Advances of Circular RNAs as Biomarkers for Osteosarcoma. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2023, 16, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejua, D.; de Flammineis, E.; Zecca, F.; Saba, L.; Davies, M.; Botchu, R. Whole-body imaging for distant staging of bone chondrosarcoma: a systematic review. Radiol. Med. 2025, 130(10), 1693–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.; Joo, M.W. Current Position of Nuclear Medicine Imaging in Primary Bone Tumors. Diagnostics (Basel) 2025, 15(21), 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Seebacher, N.A.; Hornicek, F.J.; Xiao, T.; Duan, Z. Application of liquid biopsy in bone and soft tissue sarcomas: Present and future. Cancer Lett. 2018, 439, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiev, A.K.; Teplyakov, V.V.; Musaev, E.R.; Rogozhin, D.V.; Sushentsov, E.A.; Machak, G.N.; et al. Practical guidelines for the treatment of primary malignant bone tumors. Malignant Tumors: Practical Guidelines RUSSCO #3s2, 2022, 12, 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alix-Panabières, C.; Marchetti, D.; Lang, J.E. Liquid biopsy: from concept to clinical application. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13(1), 21685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefer, A.; Yalovaya, A.; Tamkovich, S. Exosomes in Breast Cancer: Involvement in Tumor Dissemination and Prospects for Liquid Biopsy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23(16), 8845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenchov, R.; Sasso, J.M.; Wang, X.; Liaw, W.S.; Chen, C.A.; Zhou, Q.A. Exosomes─Nature’s Lipid Nanoparticles, a Rising Star in Drug Delivery and Diagnostics. ACS Nano 2022, 16(11), 17802–17846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnoletto, C.; Pignochino, Y.; Caruso, C.; Garofalo, C. Exosome-Based Liquid Biopsy Approaches in Bone and Soft Tissue Sarcomas: Review of the Literature, Prospectives, and Hopes for Clinical Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(6), 5159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yunusova, N.; Kolegova, E.; Sereda, E.; Kolomiets, L.; Villert, A.; Patysheva, M.; Rekeda, I.; Grigor’eva, A.; Tarabanovskaya, N.; Kondakova, I.; Tamkovich, S. Plasma Exosomes of Patients with Breast and Ovarian Tumors Contain an Inactive 20S Proteasome. Molecules 2021, 26(22), 6965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konoshenko, M.; Sagaradze, G.; Orlova, E.; Shtam, T.; Proskura, K.; Kamyshinsky, R.; Yunusova, N.; Alexandrova, A.; Efimenko, A.; Tamkovich, S. Total Blood Exosomes in Breast Cancer: Potential Role in Crucial Steps of Tumorigenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21(19), 7341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skryabin, G.O.; Komelkov, A.V.; Zhordania, K.I.; Bagrov, D.V.; Enikeev, A.D.; Galetsky, S.A.; Beliaeva, A.A.; Kopnin, P.B.; Moiseenko, A.V.; Senkovenko, A.M.; Tchevkina, E.M. Integrated miRNA Profiling of Extracellular Vesicles from Uterine Aspirates, Malignant Ascites and Primary-Cultured Ascites Cells for Ovarian Cancer Screening. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16(7), 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Peng, L. MicroRNA profiling of serum exosomes in patients with osteosarcoma by high-throughput sequencing. J. Investig. Med. 2020, 68(4), 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreeva, O.E.; Sorokin, D.V.; Mikhaevich, E.I.; Bure, I.V.; Shchegolev, Y.Y.; Nemtsova, M.V.; Gudkova, M.V.; Scherbakov, A.M.; Krasil’nikov, M.A. Towards Unravelling the Role of ERα-Targeting miRNAs in the Exosome-Mediated Transferring of the Hormone Resistance. Molecules 2021, 26(21), 6661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, J.; Turchinovich, A.; Shkurnikov, M.; Tonevitsky, A. Extracellular miRNAs and Cell-Cell Communication: Problems and Prospects. Trends Biochem Sci. 2021, 46(8), 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Tang, G.; Xiong, Z.; Zhou, W. Role of non-coding RNA in exosomes for the diagnosis and treatment of osteosarcoma. Front Oncol. 2024, 14, 1469833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Q.; Ma, S.; Sun, Y.; Vadamootoo, A.S.; Jin, C. A four serum-miRNA panel serves as a potential diagnostic biomarker of osteosarcoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019, 24(8), 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, S.J.; Frezza, A.M.; Abecassis, N.; Bajpai, J.; Bauer, S.; Biagini, R.; Bielack, S.; Blay, J.Y.; Bolle, S.; Bonvalot, S.; et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee, EURACAN, GENTURIS and ERN PaedCan. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Bone sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS-ERN PaedCan Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunusova, N.; Dzhugashvili, E.; Yalovaya, A.; Kolomiets, L.; Shefer, A.; Grigor’eva, A.; Tupikin, A.; Kondakova, I.; Tamkovich, S. Comparative Analysis of Tumor-Associated microRNAs and Tetraspanines from Exosomes of Plasma and Ascitic Fluids of Ovarian Cancer Patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 24(1), 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Yang, C.; Gao, A.; Sun, M.; Lv, D. MiR-101: An Important Regulator of Gene Expression and Tumor Ecosystem. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14(23), 5861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, T.; Komatsu, S.; Ichikawa, D.; Miyamae, M.; Okajima, W.; Ohashi, T.; Kiuchi, J.; Nishibeppu, K.; Kosuga, T.; Konishi, H.; Shiozaki, A.; Okamoto, K.; Fujiwara, H.; Otsuji, E. Low plasma levels of miR-101 are associated with tumor progression in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2017, 8(63), 106538–106550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Guo, Y.; Mi, N.; Zhou, L. miR-101-3p and miR-199b-5p promote cell apoptosis in oral cancer by targeting BICC1. Mol Cell Probes. 2020, 52, 101567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Yu, W.; Hu, K.; Li, M.; Chen, J.; Li, Z. miR-92a promotes tumor growth of osteosarcoma by targeting PTEN/AKT signaling pathway. Oncol Rep. 2017, 37(4), 2513–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, A.; Ohno, S.; Wu, W.; Borjigin, N.; Fujita, K.; Aoki, T.; Ueda, S.; Takanashi, M.; Kuroda, M. miR-92 is a key oncogenic component of the miR-17-92 cluster in colon cancer. Cancer Sci. 2011, 102(12), 2264–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanakakis, G.N.; Giatagana, E.M.; Berdiaki, A.; Spyridaki, I.; Hida, K.; Neagu, M.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Nikitovic, D. The Role of IGF/IGF-IR-Signaling and Extracellular Matrix Effectors in Bone Sarcoma Pathogenesis. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13(10), 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsaers, A.J.; Walkley, C.R. Cells of origin in osteosarcoma: mesenchymal stem cells or osteoblast committed cells? Bone. 2014, 62, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameline, B.; Kovac, M.; Nathrath, M.; Barenboim, M.; Witt, O.; Krieg, A.H.; Baumhoer, D. Overactivation of the IGF signalling pathway in osteosarcoma: a potential therapeutic target? J Pathol Clin Res. 2021, 7(2), 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Azevedo, J.W.V.; de Medeiros Fernandes, T.A.A.; Fernandes, J.V. Jr. ; de Azevedo. J.C.V.; Lanza, D.C.F.; Bezerra, C.M.; Andrade, V.S.; de Araújo, J.M.G.; Fernandes, J.V. Biology and pathogenesis of human osteosarcoma. Oncol Lett, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.; Scotto di Carlo, F.; Gianfrancesco, F. The Osteoclast Traces the Route to Bone Tumors and Metastases. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022, 10, 886305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagrass, H.A.; Sharaf, S.; Pasha, H.F.; Tantawy, E.A.; Mohamed, R.H.; Kassem, R. Circulating microRNAs - a new horizon in molecular diagnosis of breast cancer. Genes Cancer. [CrossRef]

- McDermott, A.M.; Kerin, M.J.; Miller, N. Identification and validation of miRNAs as endogenous controls for RQ-PCR in blood specimens for breast cancer studies. PLoS One. 2013, 8(12), e83718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.S.; Li, C.; Liang, D.; Jiang, X.B.; Tang, J.J.; Ye, L.Q.; Yuan, K.; Ren, H.; Yang, Z.D.; Jin, D.X.; Zhang, S.C.; Ding, J.Y.; Tang, Y.C.; Xu, J.X.; Chen, K.; Xie, W.X.; Guo, D.Q.; Cui, J.C. Diagnostic and prognostic implications of serum miR-101 in osteosarcoma. Cancer Biomark. 2018, 22(1), 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. MicroRNA-92 regulates cervical tumorigenesis and its expression is upregulated by human papillomavirus-16 E6 in cervical cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2013, 6(2), 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Yu, W.; Qu, X.; Wang, R.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Chen, L. Argonaute 2 promotes myeloma angiogenesis via microRNA dysregulation. J Hematol Oncol. 2014, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazendam, A.; Popovic, S.; Parasu, N.; Ghert, M. Chondrosarcoma: A Clinical Review. J Clin Med. 2023, 12(7), 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovalov, A.I.; Startseva, Zh.A.; Tyukalov, Yu.I.; Bogoutdinova, A.V.; Kotova, O.V.; Sitnikov, P.K. Results of combined treatment of primary and recurrent locally advanced soft tissue sarcoma with the use of local hyperthermia. Bone and soft tissue sarcomas, tumors of the skin, 3.

- Zachou, M.E.; Kouloulias, V.; Chalkia, M.; Efstathopoulos, E.; Platoni, K. The Impact of Nanomedicine on Soft Tissue Sarcoma Treated by Radiotherapy and/or Hyperthermia: A Review. Cancers (Basel). 2024, 16(2), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petre, E.N.; Sofocleous, C. Thermal Ablation in the Management of Colorectal Cancer Patients with Oligometastatic Liver Disease. Visc Med. 2017, 33(1), 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Use Of Microwave Thermal Ablation In Management Of Skip Metastases In Extremity Osteosarcomas. Cancer Manag Res. 2019, 11, 9843–9848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Geng, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, Q.; Chen, J. Treatment of osteosarcoma with microwave thermal ablation to induce immunogenic cell death. Oncotarget. 2014, 5(15), 6526–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, S.F.; Babkin, N.S.; Kabardaev, R.M.; Borzov, K.A.; Sofronov, D.I.; Katarova, A.V.; Valiev, A.K. The Effectiveness of Radiofrequency Thermal Ablation in the Treatment of Patients with Osteoid Osteomas of the Spine. Bone and soft tissue sarcomas, tumors of the skin. [CrossRef]

- Jamil, N.Y.; Nawrooz, M.S.; Bishoyi, A.K.; Ballal, S.; Singh, A.; Krithiga, T.; Panigrahi, R.; Babamuradova, Z.; Taher, S.G.; Alwan, M.; Jawad, M.; Mushtaq, H. The therapeutic potential of exosomes in bone cancers: osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma. Invest New Drugs. 2025, 43(4), 991–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Benavente, C.A. Exploring the Impact of Exosomal Cargos on Osteosarcoma Progression: Insights into Therapeutic Potential. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25(1), 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Zhang, C.; Liu, G.; Gu, R.; Wu, H. MicroRNA-101 inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion in osteosarcoma cells by targeting ROCK1. Am J Cancer Res. 2017, 7(1), 88–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Dong, C.; Chen, M.; Yang, T.; Wang, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Wen, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Shang, M.; Han, K.; Zhou, Y. Extracellular vesicle-mediated delivery of miR-101 inhibits lung metastasis in osteosarcoma. Theranostics. 2020, 10(1), 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zheng, X.; Lu, T.; Gu, Y.; Zheng, C.; Yan, H. The proliferation and invasion of osteosarcoma are inhibited by miR-101 via targetting ZEB2. Biosci Rep. 2019, 39(2), BSR20181283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Huang, D.; Qing, X.; Tang, L.; Shao, Z. Investigation of MiR-92a as a Prognostic Indicator in Cancer Patients: a Meta-Analysis. J Cancer. 2019, 10(18), 4430–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Jiang, L.; Shen, L.; Xiong, Z. Role of microRNA-92a in metastasis of osteosarcoma cells in vivo and in vitro by inhibiting expression of TCF21 with the transmission of bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Song, H.; Liu, L.; Hu, S.; Liao, Y.; Li, G.; Xiao, X.; Chen, X.; He, S. MiR-92a modulates proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and invasion of osteosarcoma cell lines by targeting Dickkopf-related protein 3. Biosci Rep. 2019, 39(4), BSR20190410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).