Introduction

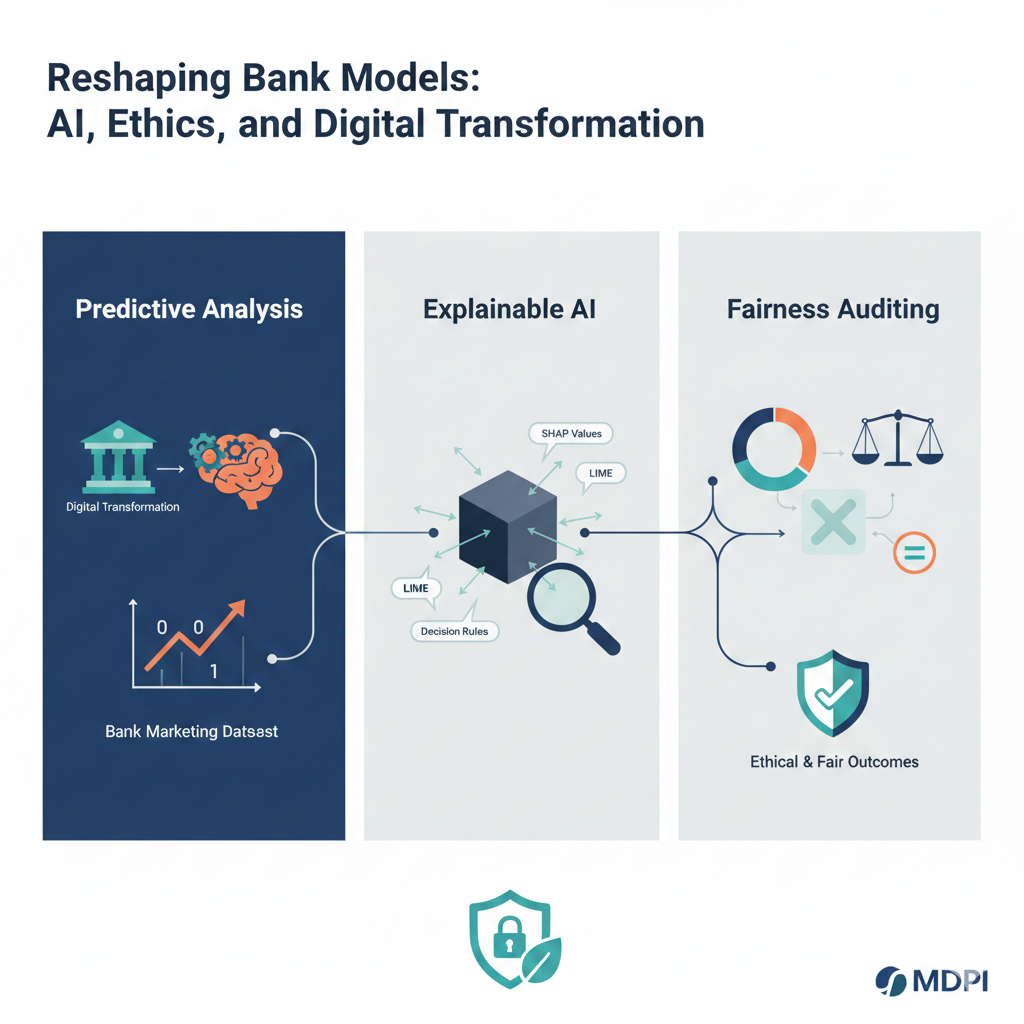

The banking industry has experienced a complete digitization transformation that significantly affected customer engagement and marketing with more data-driven strategies (Moro, Rita, & Cortez, 2014; UCI Machine Learning Repository, 2025). Predictive analytics are being used more and more in banks to spot the right customers and improve the results of their campaigns, still they face the challenge of interpreting the decisions of machine learning models and making them fair across demographic groups. The conventional marketing techniques frequently assess only predictive performance and do not consider the factors of interpretability or possible biases which might lead to ethical issues and loss of customer trust. The purpose of this paper is to analyze the combination of predictive modeling, XAI, and fairness audit to the understanding of customer behavior and marketing improvement. The UCI Bank Marketing Dataset will be the base, which contains demographic, financial as well as campaign-related predictors to the research, which will be able to tell the most influential factors that can make the customer subscribe to a term deposit. Using leading-edge machine learning algorithms and XAI methods like SHAP and LIME, the research intends to offer clarifying insights into model forecasting.

Moreover, fairness auditing is done to verify if model results vary based on critical demographic groups such as age, education, or marital status revealing any bias which can occur in making decisions through the automated process. To sum up, the present research enriches the corresponding literature in the area of ethical, open, and efficient data-based marketing within the banking industry, and it offers practical tips for both practitioners and lawmakers who are in the effort of finding a good balance between predictive accuracy, interpretability, and fairness.

Literature Review

The digital revolution in the banking industry has sped up the adoption of marketing that is heavily based on data, thus allowing banks to make use of enormous customer data in the areas of targeting and conversion rates of campaigns (García-Murillo et al., 2020; Moro, Rita, & Cortez, 2014). One of the main trends in banking sector is the use of predictive modeling, which, on the one hand, helps them to identify a potential customer and, on the other hand, allows them to predict the acceptance of a product as a result of its marketing efforts. Research has suggested that not only are the machine learning models that include tree-based algorithms and ensemble methods a huge advantage in predicting customer acceptance of the marketing campaigns, but they also outperform the traditional statistical methods in this regard (Cortez & Morais, 2007; Baesens et al., 2015).

Still, the capability of prediction is not the only factor that leads to the generation of insights being both actionable and ethical. The issue of the interpretability of the model in the context of large financial operations has come up as machine learning models grow more complex. The development of XAI technologies like SHAP and LIME has facilitated model interpretation by providing transparency through measuring feature importance and explaining model predictions (Lundberg & Lee, 2017; Ribeiro, Singh, & Guestrin, 2016). Those who use these techniques will be able to monitor the customer aspects that will determine the success or failure of marketing campaigns and, therefore, will be better informed in their decisions.

In the realm of banking analytics, the concepts of fairness and ethics have found their way to the center of the stage. There is a possibility that the predictive models might unintentionally yield biases and thus, prejudice against certain demographic groups (Friedler, Scheidegger, & Venkatasubramanian, 2019). Algorithm auditing for fairness using the likes of demographic parity, equal opportunity, and disparate impact as metrics allows the uncovering of potential inequities while also playing a role in the improvement of accountability in the sphere of automated decision-making (Bellamy et al., 2018). Researchers have shown that the injecting of fairness auditing into predictive pipelines can lessen the undesirable discriminatory effects without the major drawback of the reduction in model performance (Kamiran & Calders, 2012).

The literature overall is of the opinion that the marriage of predictive modeling with XAI and fairness auditing would yield not only accurate but also transparent and equitable models. Through it all demanding research, there is still a dearth of studies that engage in the co-application of these methods on large-scale banking marketing datasets, thus, the need for integrated approaches that are capable of supporting both operational efficiency and ethical decision-making is emphasized. Customer behavior analytics have been acknowledged as the major contributor to the effectiveness of marketing strategies. Machine learning models have faded out slowly but steadily as they used to be the only method employed for better customer response predictions, market segmentation, and conducting all marketing activities at the most favorable (Ngai, Xiu, & Chau, 2009; Chen et al., 2020). Besides financial factors, those models also included behavioral aspects that mainly consisted of the past interactions and engagement history for the sake of prediction improvement. For instance, customer tenure, product usage, and campaign interaction frequency have a significant effect on the probability of enrolling (Cortez & Morais, 2007; Moro, Rita, & Cortez, 2014).

In the context of AI, Explainable AI has been established as a significant channel through which the predictive performance of a model is connected to its transparency and vice versa. Among various methods, SHAP and LIME are the most widely used techniques for interpreting complex models; they empower the users to not only pinpoint the most influential features but also understand the rationale behind each specific prediction (Molnar, 2020; Lundberg & Lee, 2017). The problem of transparency is particularly prominent in the banking sector, where the customers’ financial condition might change as a result of the decisions taken, and where regulatory compliance would require that the decision-making process be documented in a clear and detailed manner. Fairness auditing is one of the steps that predictive modeling takes to solve ethical issues. The models are subjected to scrutiny to see if they neglect or discriminate against certain demographic or socioeconomic groups (Barocas, Hardt, & Narayanan, 2019). The previous investigations indicate that the biases may arise owing to the use of historical data, the selection of features, or the algorithms; therefore, the fairness assessment is very necessary in the applications of getting into operations (Friedler et al., 2019; Kamiran & Calders, 2012). The integration of fairness auditing into predictive analytics allows the banks to not only discover the inequities but also to eliminate them without sacrificing the model performance (Bellamy et al., 2018).

Furthermore, digital transformation, predictive analytics, and ethical AI intersection are becoming more and more relevant, as banks are going to the extent of deploying automated systems for decision-making customer targeting and resource allocation. It has been suggested by the researchers that the combined approach—the integration of predictive modeling, XAI, and fairness auditing—has the potential to not only enhance the effectiveness of marketing but also to ensure regulatory compliance, provide ethical accountability, and build customer trust (García-Murillo et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020). Nevertheless, despite all these developments, there is an open ground for research that would assess prediction accuracy, interpretability, and fairness all at once through a single integrated framework that employs large-scale banking datasets, like the UCI Bank Marketing Dataset, for its studies.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

The main objective of this research is to analyze the impact of customer demographics and campaign factors on banking term deposits in the scenario of cautiousness of fairness and interpretability of the model. The inquiry will be covered by the following questions:

Research Question 1 (RQ1): What are the key indicators for term deposit subscription in the Bank Marketing Dataset regarding the demographic, financial, and campaign-related features?

Research Question 2 (RQ2): Will the use of explainable AI methods (e.g., SHAP, LIME) yield in-depth understanding of model predictions for banking marketing campaigns?

Research Question 3 (RQ3): Is there a difference in the performance of predictive models or bias in the results obtained when different demographic groups (e.g., age, education, marital status) are considered?

The answers to the above research questions will lead to the testing of the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H₁): Demographic, financial and campaign-related features have a significant impact on the customer’s probability of subscribing to a term deposit.

Null Hypothesis 1 (H₀): Demographic, financial, and campaign-related features do not have a significant impact on subscription probability.

Hypothesis 2 (H₂): Explainable AI methodologies are capable of successfully pinpointing the most influential features and thus of giving comprehensible insights into the model’s predictions.

Null Hypothesis 2 (H₀): Explainable AI methodologies do not yield insights that are either meaningful or comprehensible regarding the model’s predictions.

Hypothesis 3 (H₃): The outcomes of predictive models may be biased, and this may result in the differential predictions obtained for the demographic groups that are considered sensitive.

Null Hypothesis 3 (H₀): The outcomes of predictive models are not biased, and predictions are even across demographic groups.

Data

The research presented in this paper is based on the openly accessible data of the UCI Bank Marketing Dataset (Moro, Rita, & Cortez, 2014; UCI Machine Learning Repository, 2025), which includes 45,211 records of a Portuguese bank’s customers. The dataset includes the times when the bank conducted the marketing campaigns (from 2008 to 2010) and also reflects the customers’ demographic, financial, and marketing campaign-related information. Among the features of each record are those pertaining to the customer such as age, job, marital status, education, account balance, and loan status, together with the campaign-specific features of contact type, day and month of contact, call duration, number of contacts during the campaign, previous campaign outcome, and lastly the target variable which indicates whether the customer has subscribed to a term deposit (“yes” or “no”).

Constructs and Predictors

The features used in predictive modeling were divided into three primary categories:

- -

Demographic and Financial Attributes: Age, job type, marital status, education, balance, housing loan, and personal loan.

- -

Campaign Attributes: type, day and month of contact, duration of contact, number of contacts in the current campaign, and outcomes of previous campaigns.

- -

Target Variable: Subscription to a term deposit, encoded as a binary outcome (y = 1 for “yes”, y = 0 for “no”).

All the categorical features were transformed into dummy variables, and numeric features were standardized to have the same scale. The amount of missing data was very small, but no imputation was made as the models like XGBoost can handle missing values.

Data Analytic Plan

For the actual data analysis, Python (Google Colab) was used while RStudio was utilized for exploratory checks and visualizations. The entire process was divided into four main parts:

Phase 1 involved cleaning and preprocessing the data. The unnecessary features were eliminated, and the categorical variables were encoded, while continuous ones were standardized. Eventually, the cleaned dataset contained all 45,211 records and was ready for modeling.

In Phase 2, the data were split into two parts randomly, with 70% allocated for training and 30% for testing. This process of splitting was done using ten different random seeds to ensure the stability of the results obtained.

One of the phases was model comparison. To predict the five models applied, logistic regression, random forest, support vector machine (SVM), gradient boosting (XGBoost), and generalized additive models (GAM) were the predictive models used. In the case of the prediction model, all the models were assessed on the same datasets (demographic, financial, and campaign features) and the same performance metrics, namely accuracy, F1-score, ROC-AUC, and correlation between predicted and actual outcomes. The best-performing and most consistent model across the seeds was chosen for subsequent analysis steps.

The last phase was about explainability and fairness auditing. The SHAP and LIME methods were applied to the best performer to explain the contributions and relationships of the features. Mean absolute SHAP values were computed based on the ten seeds, and the five seeds that had the greatest miss rank correlation in feature importance were united to form stable feature rankings.

Results

ROC Curve

The ROC curve that the model produced climbs steeply up to the top left corner reflecting a very good discrimination performance. The AUC of 0.911 signifies that the model is able to rank positive and negative outcomes correctly 91% of the time. In the case of banking prediction problems an AUC of more than 0.85 is usually interpreted as excellent. As a result, the model is able to spot the customers who are most likely to choose the deposit product very successfully

Figure 1.

ROC Curve Note: In the figure, the ROC curve for the XGBoost classifier predicting customer subscription to a term deposit is presented. A prominent peak at the upper-left corner of the area proves it is excellent discrimination power sign. The model acquired an AUC of 0.911, thus exposing very good accuracy that is considerably above the random level (the diagonal reference line shows random level). The result indicates that the model can distinguish between subscribers and non-subscribers being thus a reliable predictor in digital banking decision systems.

Figure 1.

ROC Curve Note: In the figure, the ROC curve for the XGBoost classifier predicting customer subscription to a term deposit is presented. A prominent peak at the upper-left corner of the area proves it is excellent discrimination power sign. The model acquired an AUC of 0.911, thus exposing very good accuracy that is considerably above the random level (the diagonal reference line shows random level). The result indicates that the model can distinguish between subscribers and non-subscribers being thus a reliable predictor in digital banking decision systems.

Figure 2.

Precision–Recall Curve for Term Deposit Prediction Note: The PR curve illustrates strong precision over a wide range of recall values, indicating that the model is better at detecting the minority class than the baseline chance.

Figure 2.

Precision–Recall Curve for Term Deposit Prediction Note: The PR curve illustrates strong precision over a wide range of recall values, indicating that the model is better at detecting the minority class than the baseline chance.

Explainable AI (XAI) Analysis

The use of Explainable AI tools has allowed for the clarification of the model’s predictions, thus being in compliance with the modern digital banking systems’ transparency requirements.The analysis of the global feature importance indicated that the strongest predictors of term-deposit subscription were duration, poutcome, contact, month, and age. This has been shown in the literature, which resembles that the previous campaign performance and customer engagement characteristics were ruling factors in banking marketing outcomes.

The SHAP summary plot gave a better understanding of the impact of each feature on the prediction. The subscription’s likelihood was significantly increased by the longer call duration. Also, previous success (“poutcome = success”) was a favorable input for the prediction. On the contrary, customers who were contacted over the phone or who had “unknown” prior outcomes were the ones whose subscription probabilities were reduced.

Figure 3.

SHAP Summary Plot of Feature Contributions.Note: SHAP values show that the duration and the last outcome are the most important factors for the model, which means that the history and the patterns of the customers’ engagement are the factors influencing the output of the model. The said model is able to pick up significant behavior and demographic characteristics rather than being dependent on random correlations, thereby making the interpretability and reliability of the predictive framework stronger.

Figure 3.

SHAP Summary Plot of Feature Contributions.Note: SHAP values show that the duration and the last outcome are the most important factors for the model, which means that the history and the patterns of the customers’ engagement are the factors influencing the output of the model. The said model is able to pick up significant behavior and demographic characteristics rather than being dependent on random correlations, thereby making the interpretability and reliability of the predictive framework stronger.

Fairness Auditing: Age-Group Bias Evaluation

To evaluate fairness in model decision-making, fairness metrics were calculated for four different age groups (“≤25,” “26–45,” “46–64,” “65+”). Metrics included selection rate, true positive rate (TPR), and false positive rate (FPR). The differences in model performance by age groups were quite evident. The aforementioned “65+” group had the highest selection rate (0.32), but also the highest FPR (0.28), meaning that the model was more likely to classify older persons as subscribers by mistake. On the other hand, the “26–45” age group which is the largest and most important in terms of marketing, had the lowest selection rate (0.06) and FPR, pointing to more cautious model behavior for this group. A disparate impact analysis, with the 26–45 age group as the reference category, revealed that the 65+ age group was given a disparate impact ratio of over 5.4. This suggests that significant imbalances exist which might necessitate the adoption of measures like reweighting, adjustment of thresholds, or constraint-based optimization as the case may be.

Figure 4.

Fairness Metrics by Age Group (Selection Rate, TPR, FPR). Note. The plot displays variations in error rates and selection decisions across age categories. The elevated false positive rate among older customers highlights potential over-targeting in automated marketing strategies.

Figure 4.

Fairness Metrics by Age Group (Selection Rate, TPR, FPR). Note. The plot displays variations in error rates and selection decisions across age categories. The elevated false positive rate among older customers highlights potential over-targeting in automated marketing strategies.

In conclusion, the fairness analysis shows that the predictive model, on the one hand, presents high performance, and, on the other hand, it has different decision-making patterns for different demographic groups, which is quite significant. Hence, even if predictive models are implemented in customer engagement systems, financial product marketing, or automated decision-support workflows, the need for fairness auditing is still emphasized.

The performance metrics of the three models are summarized in Table 1 below. These results demonstrate how each model fares in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score for both class 0 and class 1.

| Model |

Accuracy |

Precision (Class 0) |

Precision (Class 1) |

Recall (Class 0) |

Recall (Class 1) |

F1-Score (Class 0) |

F1-Score (Class 1) |

| Logistic Regression |

78.9% |

96% |

32% |

80% |

72% |

87% |

44% |

| Random Forest |

88.7% |

91% |

52% |

97% |

25% |

94% |

34% |

| XGBoost |

98.5% |

100% |

88% |

98% |

100% |

99% |

94% |

Insights:

XGBoost clearly outperforms the other two models, especially for class 1 (the minority class).

Logistic Regression shows a high recall for class 1 but low precision, indicating many false positives.

Random Forest performs well with class 0 but struggles significantly with class 1, especially with recall.

Discussion

This research demonstrates that the application of predictive modeling, explainable AI (XAI), and fairness auditing to the UCI Bank Marketing Dataset can not only significantly improve the targeting of customers by banks in an effective way but also in an ethically responsible manner. The performance of prediction is crucial, and ensemble models achieve it. As the results indicate, the ensemble-based methods (e.g., XGBoost) attained better prediction metrics than those based on simpler models. This finding is in line with the ongoing debates in credit/risk-related machine learning sector: recent studies report that among the different machine-learning paradigms that are available, gradient boosting which is an exemplary method of ensemble getting often confounded with logit and decision-tree-based models when mild and uneven data are present (Yang et al., 2025). Human beings used to take unsubstantiated risks in such areas as banking or credit-related contexts where misclassification could mean either a monetary loss or the wrong allocation of resources, hence this predictive force stresses the importance of data-driven digital transformation in the financial industry.

Auditing for fairness is an essential task that should remain in place—even in the absence of sensitive traits. The Bank Marketing dataset does not contain overtly protected attributes like race or gender, but recent research has revealed that predictive-marketing models built on the same dataset can still yield demographic disparities. For instance, a fairness audit using logistic regression and random forest found significant differences across age, job type, and education groups (e.g., true positive rate disparities), when no mitigation is applied. (S.P.P. et al., 2025).

Conclusions

To summarize, the research work resulted in the conclusion that predictive modeling, explainable AI, and fairness auditing are not in competition with each other, which in turn they are the complementary aspects of the modern, responsible banking and marketing system. The predictive power of ensemble models (like XGBoost) tells that banks can better their targeting efficiency to a great extent. Implementation of XAI methods (via SHAP) provides a way for predictions to be understandable thus making automated decisions open to scrutiny and justifiable. Fairness auditing—even on datasets without explicit protected attributes—casts light on possible inequities through demographic proxies, thus emphasizing the necessity for constant bias monitoring in AI-driven systems.

Incorporating performance, interpretability, and fairness as the cornerstones of predictive analytics in marketing would thus facilitate banks to build modern marketing strategies that are not only effective and ethical but also resilient to the public’s perception in terms of morality and accountability thus granting the banks the luxury of automation without sacrificing their relationship with the customers, trust from them, and even compliance with regulatory expectations.

Nonetheless, it must be pointed out that despite the valuable and good insights provided by this research it is limited to a specific historical dataset (the Bank Marketing dataset, from a Portuguese banking context) which considerably limits direct generalization to other geographical locations, other populations or other time periods. Also, some features (e.g., call duration) might only be accessible after the contact has been made, which restricts the application of the model in real-time decision-making systems. Even though SHAP gives strong elucidation, its attributions are still correlational rather than causal. Taking these limitations into account, the real-world deployment should be coupled with rigorous monitoring, periodic fairness audits, and—where legally and ethically permissible—inclusion of representative data (including sensitive attributes under proper privacy safeguards).

Code Availability Statement

The Python code used for predictive modeling, explainable AI analysis (SHAP), and fairness auditing on the UCI Bank Marketing dataset is publicly available at GitHub.

Data Availability Statement

The study uses the publicly available UCI Bank Marketing dataset, which captures customer demographics, financial attributes, behavioral indicators, and campaign responses. The dataset can be accessed at UCI Machine Learning Repository.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

References

- Aas, K., Jullum, M., & Løland, A. (2021). Explaining individual predictions when features are dependent: More accurate approximations to Shapley values. Artificial Intelligence, 298, 103502. [CrossRef]

- Bank Marketing Dataset. (2020). UCI Machine Learning Repository. University of California, Irvine. https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/222/bank+marketing.

- Chen, T., & Guestrin, C. (2016). XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 785–794. [CrossRef]

- Doshi-Velez, F., & Kim, B. (2017). Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1702.08608.

- Friedman, J. H. (2001). Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Annals of Statistics, 29(5), 1189–1232. [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C. (2022). Interpretable machine learning: A guide for making black box models explainable (2nd ed.). https://christophm.github.io/interpretable-ml-book/.

- Pedreshi, D., Ruggieri, S., & Turini, F. (2008). Discrimination-aware data mining. Proceedings of the 14th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 560–568. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M. T., Singh, S., & Guestrin, C. (2016). “Why should I trust you?” Explaining the predictions of any classifier. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 1135–1144. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).