Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice

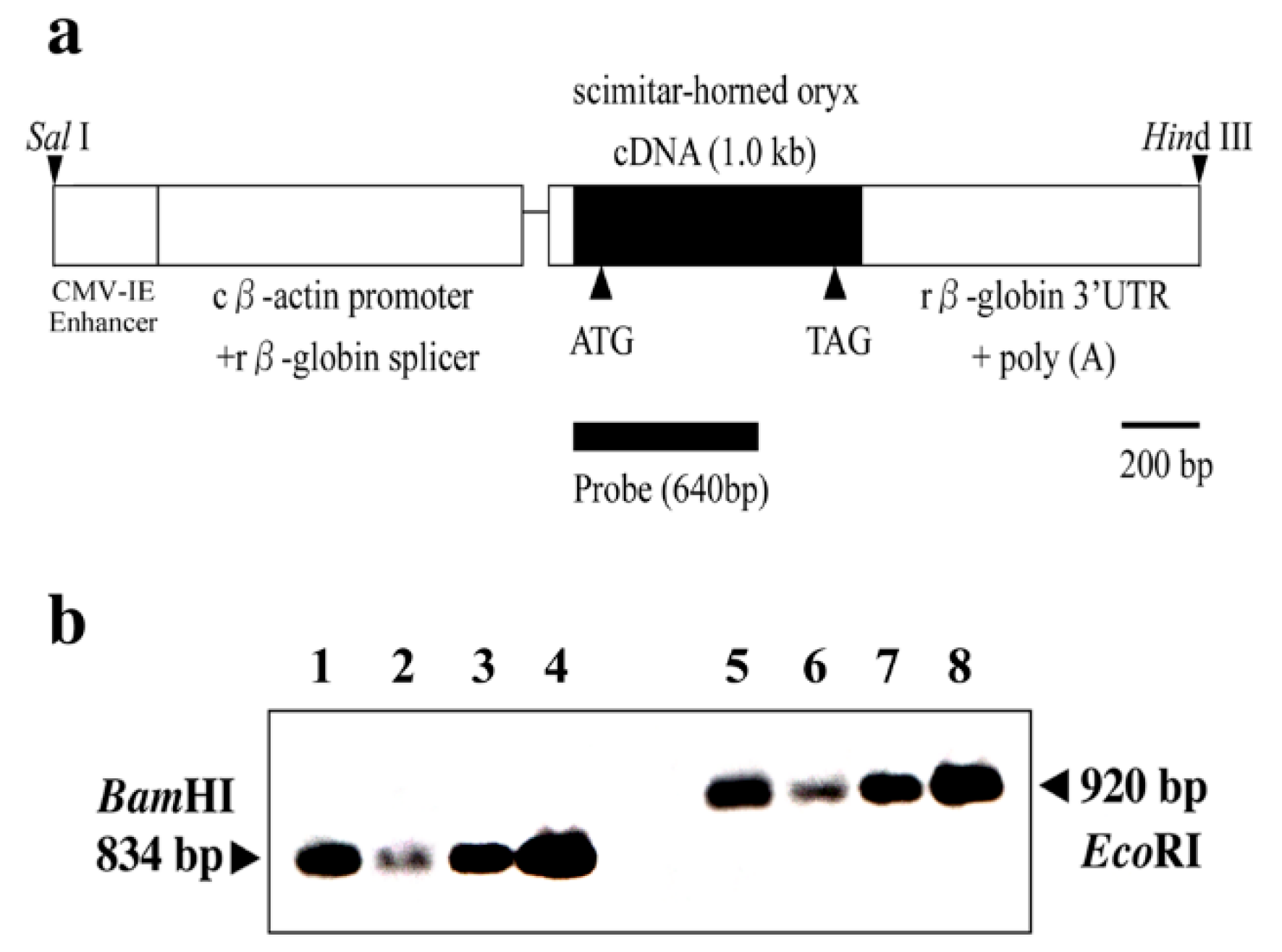

2.2. Total DNA Isolation and Non-Radioactive Southern Blot Screening of Transgenes

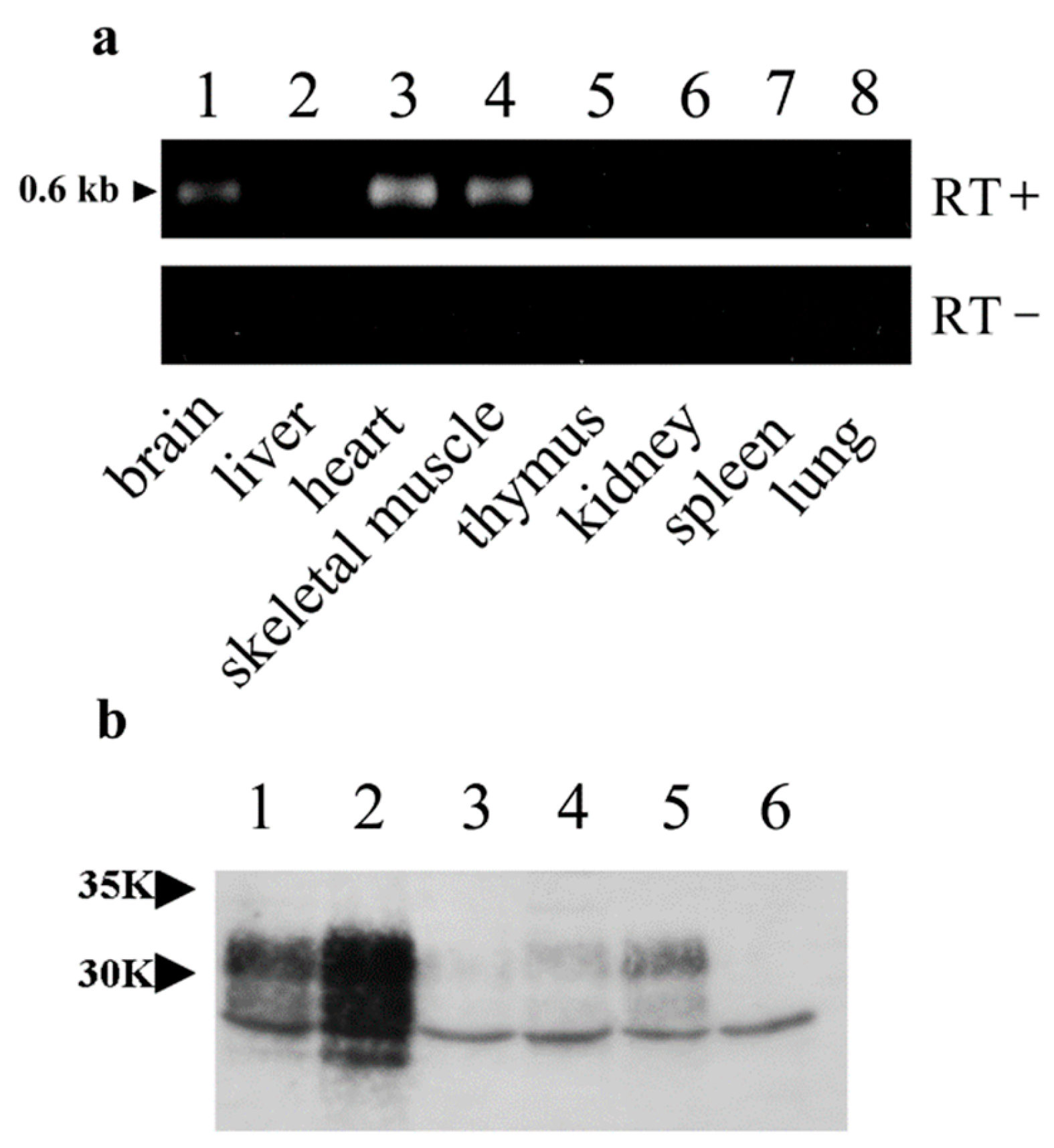

2.3. Total RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcriptase–Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) of OrPrP mRNAs

2.4. RT-PCR of Doppel (Dpl) mRNAs

2.5. Immunoprecipitation

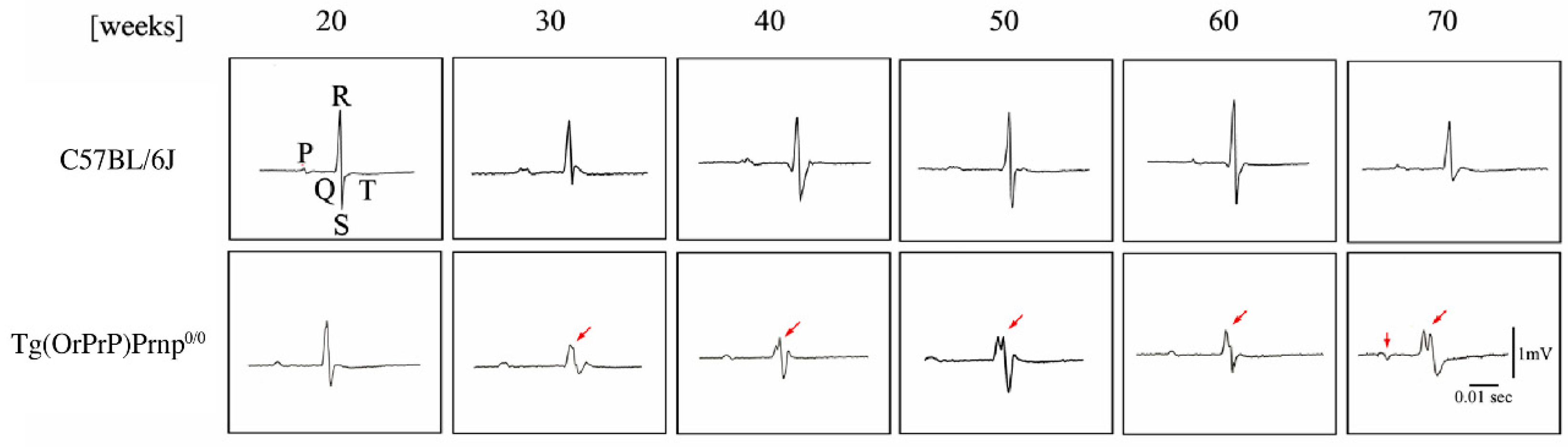

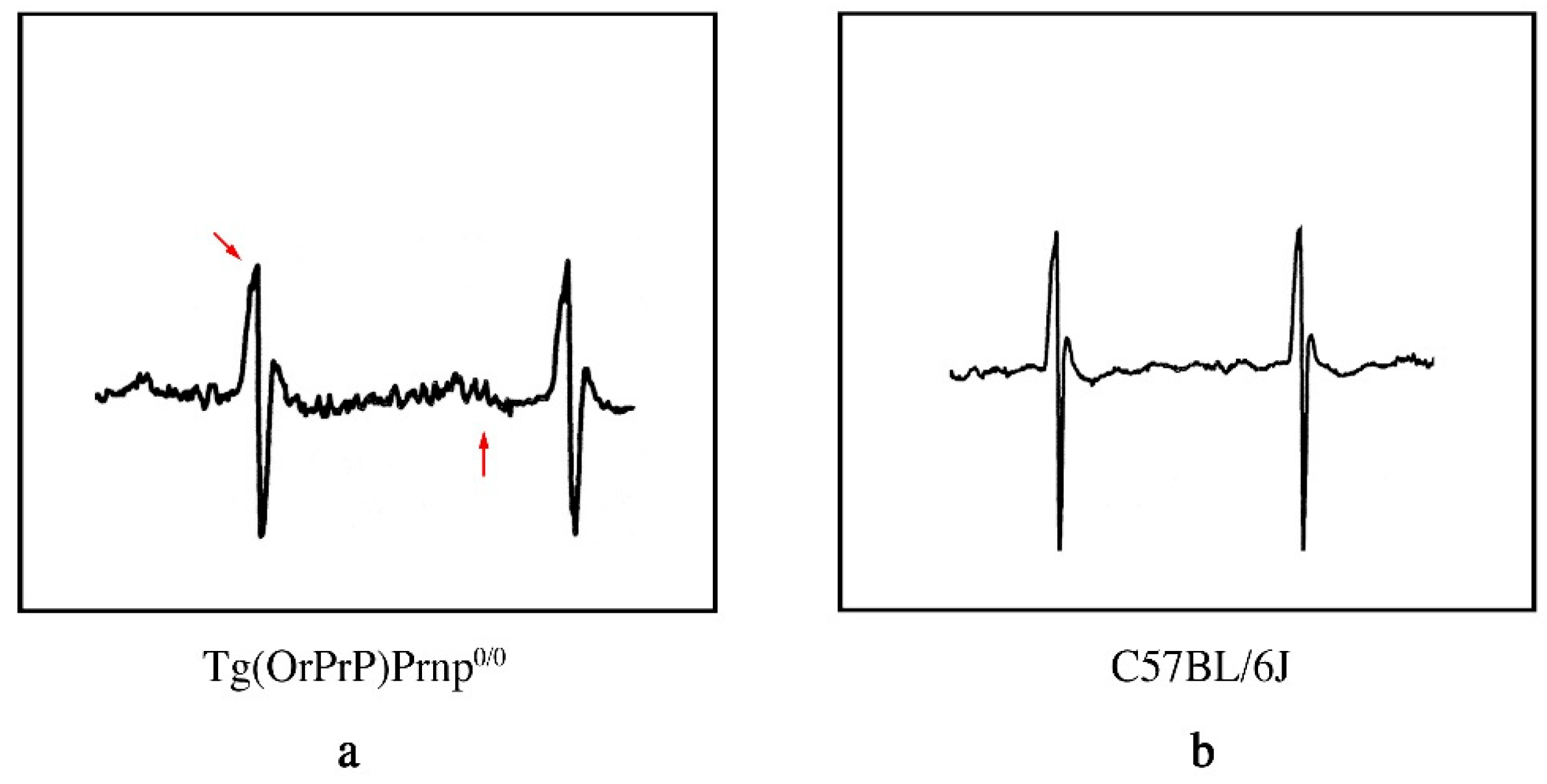

2.6. Electrocardiographic (ECG) Patterns in Tg Mice

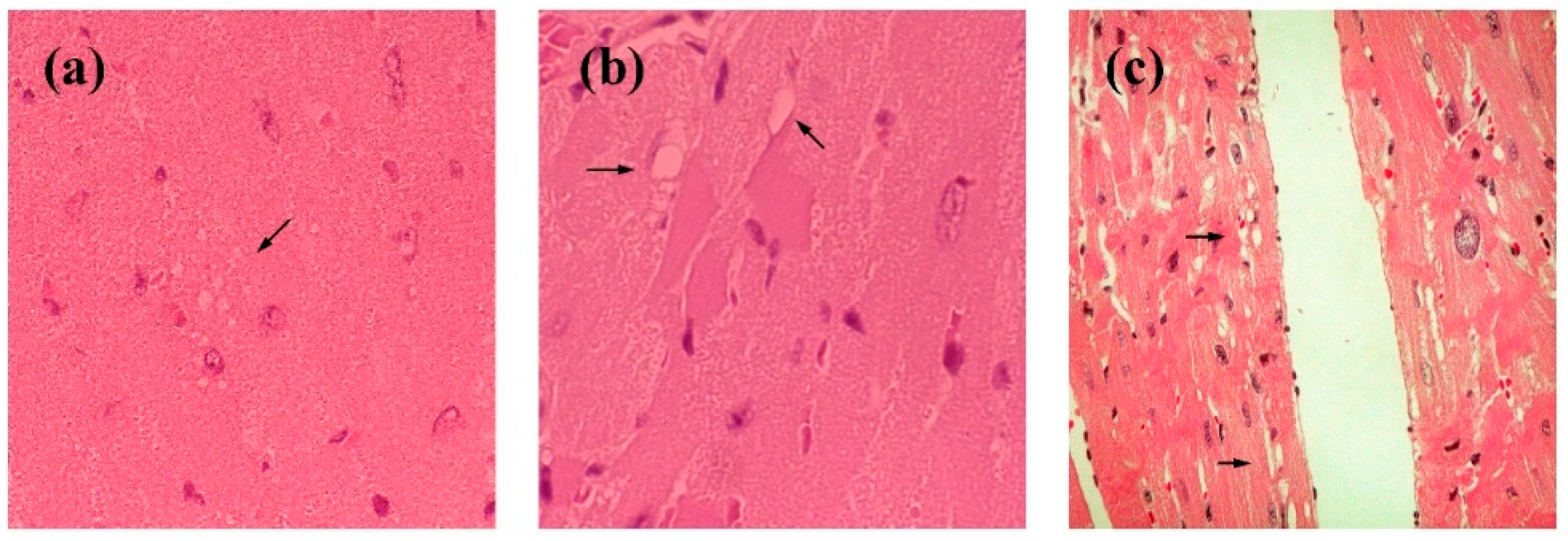

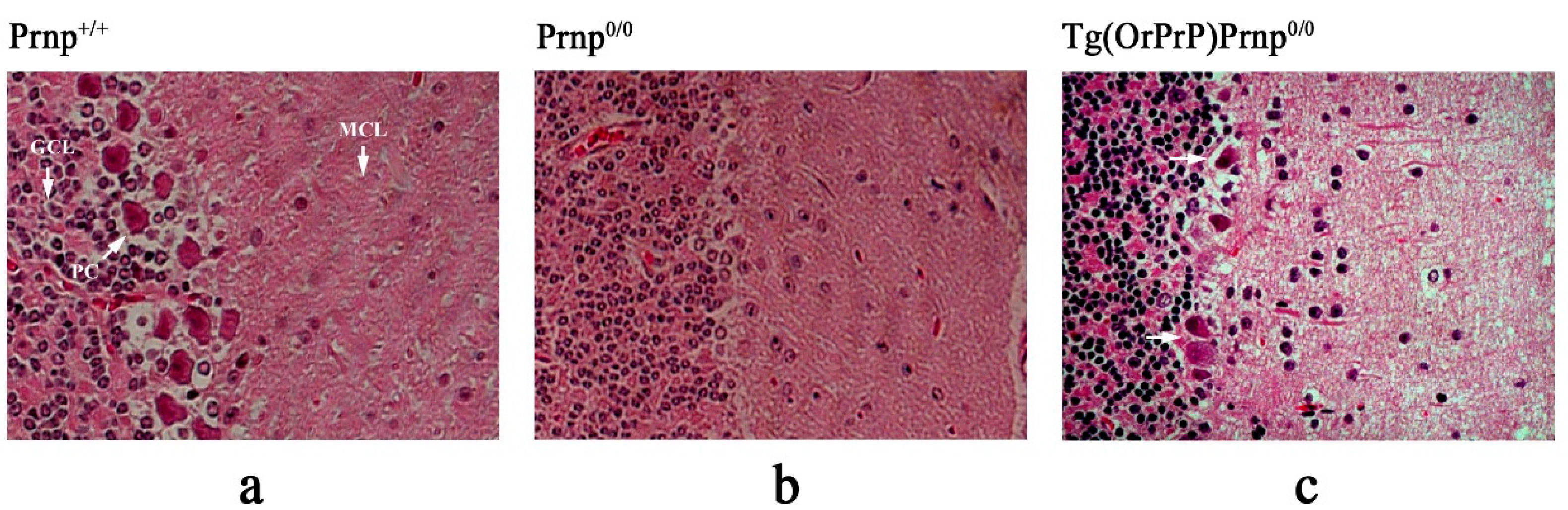

2.7. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining and Immunohistochemistry

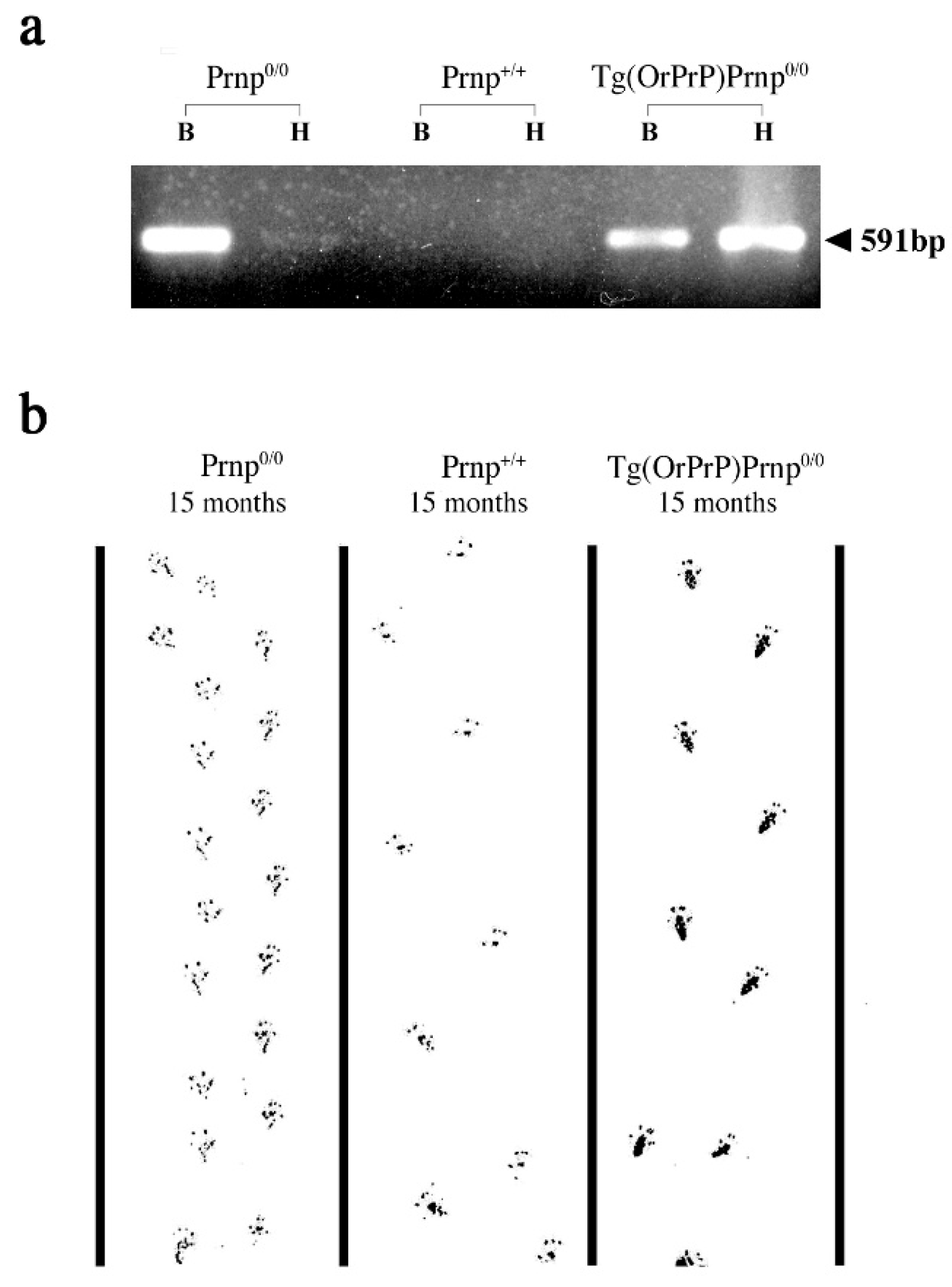

2.8. Footprint

3. Results

3.1. Effect of PrP Genes in Tg Mice

3.2. Phenotypic Rescue of Dpl-Induced Ataxia by Co-Expression of OrPrP

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Condello, C.; Westaway, D; Prusiner, S.B. Expanding the prion paradigm to include Alzheimer and Parkinson Diseases. JAMA Neurol 2024, 81, 1023–1024. [CrossRef]

- Prusiner, S.B. Transgenetic investigations of prion diseases of humans and animals. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1993, 339, 239–254. [CrossRef]

- Westaway, D.; DeArmond, S.J.; Cayetano-Canlas, J.; Groth, D.; Foster, D.; Yang, S.L.; Torchia, M.; Carlson, G.A.; Prusiner, S.B. Degeneration of skeletal muscle, peripheral nerves, and the central nervous system in transgenic mice overexpressing wild-type prion proteins. Cell 1994, 76, 117–129. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.P.; Strauss, A.W. Inherited cardiomyopathies. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 913–919.

- Toyo-oka, T.; Nagayama, K.; Suzuki, J; Sugimoto, T. Noninvasive assessment of cardiomyopathy development with simultaneous measurement of topical1H- and 31P-magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Circulation 1992, 86, 295–301. [CrossRef]

- Thomzig, A.; Kratzel, C.; Lenz, G.; Kruger, D.; Beekes, M. Widespread PrPSc accumulation in muscle of hamsters orally infected with scrapie. EMBO Rep. 2003, 4, 530–533. [CrossRef]

- Marin-Garcia, J.; Goldenthal, M.J.; Filiano, J.J. Cardiomyopathy associated with neurologic disorders and mitochondrial phenotype. J. Child Neurol. 2002, 17, 759–765.

- Bunse, M.; Bit-Avragim, N.; Riefflin, A.; Perrot, A.; Schmidt, O.; Kreuz, F.R.; Dietz, R.; Jung, W.I.; Osterziel, K.J. Cardiac energetics correlates to myocardial hypertrophy in Friedreich's ataxia. Ann. Neurol. 2003, 53, 121–123. [CrossRef]

- Itohara, S.; Onodera, T.; Tsubone, H. Prion gene modified mouse which exhibits heart anomalies. US Patent 6657105, 2003.

- Mastrangelo, P.; Westaway, D. Biology of the prion gene complex. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2001, 79, 613–628.

- Moore, R.C.; Mastrangelo, P.; Bouzamondo, E.; Heinrich, C.; Legname, G.; Prusiner, S.B.; Hood, L.; Westaway, D.; DeArmond, S.J.; Tremblay, P. Doppel-induced cerebellar degeneration in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001, 98, 15288–15293. [CrossRef]

- Shintaku, T.; Ohba, T.; Niwa, H.; Kushikata, T.; Hirota, K.; Ono, K.; Imaizumi, T.; Kuwasako, K.; Sawamura, D.; Murakami, M. Effects of propofol on electrocardiogram in mice. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 126, 351–358.

- Scott, M.R.; Will, R.; Nguyen, H.O.; Tremblay, P.; DeArmond, S.J.; Prusiner, S.B. Compelling Transgenic evidence for transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy prions to humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999, 96, 15137–15142. [CrossRef]

- Telling, G.C.; Scott, M.; Hsiao, K.K.; Foster, D.; Yang, S.L.; Torchia, M.; Sidle, M.; Collinge, G.; DeArmond, S.J.; Prusiner, S.B. Transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease from humans to transgenic mice expressing chimeric human-mouse prion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994, 91, 9936–9940.

- Kirkwood, J.K.; Cunningham, A.A. Epidemiological observations on spongiform encephalopathies in captive wild animals in the British islets. Vet. Rec. 1994, 135, 296–303.

- Cunningham, A.A.; Kirkwood, J.K.; Dawson, M.; Spencer, Y.I.; Green, R.B.; Wells, G.A.H. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy infectivity in greater kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1044–1049. [CrossRef]

- Oesch, B.; Westaway, D.; Prusiner, S.B. Prion protein genes: evolutionary and functional aspects. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1991, 172, 109–124.

- Seo, S.W.; Hara, K.; Kubosaki, A.; Nasu, Y.; Nishimura, T.; Saeki, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Endo, H.; Onodera, T. Comparative analysis of the prion protein open reading frame nucleotide sequences of two wild ruminants, the moufflon and golden takin. Intervirology 2001, 44, 359–363. [CrossRef]

- Shimada, M.; Shimano, H.; Gotoda, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Kawamura, M.; Inaba, T.; Yazaki, Y.; Yamada, N. Overexpression of human lipoprotein lipase in transgenic mice. Resistance to diet-induced hypertriglyceridemia and hypercholesterolemia. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 17924–17929. [CrossRef]

- Honda, H.; Mano, H.; Katsuki, M.; Yazaki, Y.; Hirai, H. Increased tyrosine-phosphorylation of 55 KDa proteins in beta-actin / Tec transgenic mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 206, 287–293.

- Yokoyama, T.; Kimura, K.M.; Ushiki, Y.; Yamada, S.; Morooka, A.; Nakashiba, T.; Sassa, T.; Itohara, S. In vitro conversion of cellular prion protein to pathogenic isoforms, as monitored by conformation-specific antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 11265–11271.

- Ishii, S.; Nagase, T.; Tashiro, F.; Ikuta, K.; Sato, S.; Waga, I.; Kume, K.; Miyazaki, J.; Shimizu, T. Bronchial hyperreactivity, increased endotoxin lethality and melanocytic tumorigenesis in transgenic mice overexpressing platelet-activating factor receptor. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 133–142.

- James, J.; Osinska, H.; Hewett, T.E.; Kimball, T.; Klevitsky, R.; Witt, S.; Hall, D. G.; Gulick, J.; Robbins, J. Transgenic over-expression of a motor protein at high levels results in severe cardiac pathology. Transgenic Res. 1999, 8, 9–22.

- Ma, J.; Wollmann, R.; Lindquist, S. Neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration when PrP accumulates in cytosol. Science 2002, 298, 1781–1785.

- Ma, J.; Lindquist, S. Wild-type PrP and a mutant associated with prion diseases are subject to retrograde transport and proteasome degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001, 98, 14955–14960. [CrossRef]

- Onodera, T. Dual role of cellular prion protein in normal host and Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B. Phys. Biol. Sci. 2017, 93, 155–173. [CrossRef]

- Sakudo, A.; Onodera, T. Prion protein (PrP) gene-knockout cell lines: insight into functions of the PrP. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 2, 75. [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.C.; Lee, I.Y.; Silverman, G.L.; Harrison, P.M.; Strome, R.; Heinrich, C.; Karunaratne, A.; Pasternak, S.H.; Chishti, M.A.; Liang, Y.; Mastrangelo, P.; Wang, K.; Smit, A.F.; Katamine, S.; Carlson, G.A.; Cohen, F.E.; Prusiner, S.B.; Melton, D.W.; Tremblay, P.; Hood, L.E.; Westaway, D. Ataxia in prion protein (PrP)-deficient mice is associated with upregulation of the novel PrP-like protein doppel. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 292, 797–817. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.G.; Lyons, G.E.; Micales, B.K.; Malhorra, A.; Factor, S.; Leinwand, L.A. Cardiomyopathy in transgenic myf5 mice. Circ. Res. 1996, 78, 379–387. [CrossRef]

- Molkentin, J.D.; Robbins, J. With great power comes great responsibility: using mouse genetics to study cardiac hypertrophy and failure. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2009, 46, 130–136. [CrossRef]

- Brodehl, A.; Belke, D.D.; Garnett, L.; Martens, K.; Abdelfatah, N.; Rodriguez, M.; Diao, C.; Chen, Y.X.; Gordon, PM.; Nygren, A.; Gerull, B. Transgenic mice overexpressing desmocollin-2 (DSC2) develop cardiomyopathy associated with myocardial inflammation and fibrotic remodeling. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0174019.

- D'Angelo, D.D.; Sakata, Y.; Lorenz, J.N.; Boivin, G.P.; Walsh, R.A.; Liggett, S.B.; Dorn, G.W. Transgenic Gαq overexpression induces cardiac contractile failure in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997, 94, 8121–8126.

- Tardiff, J.C.; Factor, S.M.; Tompkins, B.D.; Hewett, T.E.; Palmer, B.M.; Moore, R.L.; Schwartz, S.; Robbins, J.; Leinwand LA. A truncated cardiac troponin T molecule in transgenic mice suggests multiple cellular mechanisms for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 1998, 101, 2800–2811.

- Ohmura, H.; Yasukawa, H.; Minami, T.; Sugi, Y.; Oba, T.; Nagata, T.; Kyogoku, S.; Ohshima, H.; Aoki, H.; Imaizumi, T. Cardiomyocyte-specific transgenic expression of lysyl oxidase-like protein-1 induces cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Hypertens. Res. 2012, 35, 1063–1068. [CrossRef]

- Moncayo-Arlandi, J.; Guasch, E.; Sanz-de la Garza, M.; Casado, M.; Garcia, N.A.; Mont, L.; Sitges, M.; Knöll, R.; Buyandelger, B.; Campuzano, O.; Diez-Juan, A.; Brugada, R. Molecular disturbance underlies to arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy induced by transgene content, age and exercise in atruncated PKP2 mouse model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 3676–3688.

- Gerull, B.; Brodehl, A. Genetic Animal Models for Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11:624. [CrossRef]

- Georgakopoulos, D.; Christie, M.E.; Giewat, C.M.; Seidman, J.G.; Kass, D.A. The pathogenesis of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: early and evolving effects from an alpha-cardiac myosin heavy chain missense mutation. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 327–330. [CrossRef]

- Geisterfer-Lowrance, A.A.; Christe, M.; Conner, D.A.; Ingwall, J.S.; Seidman, C.E.; Seidman, J.G. A mouse model of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Science 1996, 272, 731–734.

- Gao, W.D.; Perez, N.G.; Seidman, C.E.; Seidman, J.G.; Marban, E. Altered cardiac excitation-contraction coupling in mutant mice with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 1999, 103, 661–666.

- Fang, Q.; Kan, H.; Lewis, W.; Chen, F.; Sharmann P.; Finkel, M.S. Dilated cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice expressing HIV Tat. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2009, 9, 39–45.

- Friman, G.; Wesslen, L.; Fohlman, J.; Karjalainen, J.; Rolf, C. The epidemiology of infectious myocarditis, lymphocytic myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 1996, 16(Supp. O), 36–41. [CrossRef]

- Grist, N.R.; Reid, D. Epidemiology of viral infections of the heart. In Banatvala, J.E. ed. Viral Infections of the Heart; Hodder and Stoughton: London, 1993; pp. 23–31.

- Wessely, R.; Klingel, K.; Santana, L.F.; Dalton, N.; Hongo, M.; Lederer, W.J.; Kandolf, R.; Knowlton, K.U. Transgenic expression of replication-restricted enteroviral genomes in heart muscle induce defective excitation-contraction coupling and dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 1998, 102, 1444–1453. [CrossRef]

- Gomez, A.M.; Valdivia, H.H.; Cheng, H.; Lederer, M.R.; Santana, L.F.; Cannell, M.B.; McCune, S.A.; Altschuld, R.A.; Lederer, W.J. Defective excitation-contraction coupling in experimental cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Science 1997, 276, 800–806. [CrossRef]

- Huen, D.S.; Fox, A.; Kumar, P.; Searle, P.F. Dilated heart failure in transgenic mice expressing the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen-leader protein. J. Gen. Virol. 1993, 74, 1381–1391. [CrossRef]

- Westaway, D.; DeArmond, S.J.; Canlas-Cayetano, J.; Groth, D.; Foster, D.; Yang, S.L.; Torchia, M.; Calson, G.A.; Prusiner, S.B. Degeneration of skeletal muscle, peripheral nerves, and central nervous system in transgenic mice overexpressing wild-type prion proteins. Cell 1994, 76, 117–129. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Liang, J.; Zheng, M.; Li, X.; Wang, M.; Vanegas, D.; Wu, D.; Chakraborty, B.; Hays, A.P.; Chen, K.; Che, S.G.; Booth, S.; Cohen, M.; Gambetti, P.; Kong, Q-Z. Inducible overexpression of wild-type prion protein in the muscles leads to a primary myopathy in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007, 104, 6800–6805.

- Suardi, S.; Vimercati, C.; Casalone, C.; Gelmetti, D.; Corona, C.; Lulini, B.; Mazza, M.; Lombardi, G.; Moda, F.; Ruggerone, M.; Campaganani, I.; Piccoli, E.; Catania, M.; Groschup, M.H.; Balkema-Buschmann, A.; Caramelli, M.; Monaco, S.; Zannuso, G.; Tagliavini, F. Infectivity in skeletal muscle of cattle with atypical bovine spongiform encephalopathy. PLoS One 2012, 7, e31449. [CrossRef]

- Andréoletti, O.; Orge, L.; Benestad, S.L.; Beringue, V.; Litaise, G.; Simon, S.; Le Dur, A.; Laude, H.; Simmons, H.; Lugan, S.; Corbière, F.; Costes, P.; Morel, N.; Schelcher, F.; Lacroux, C. Atypical/Nos98 scrapie infectivity in sheep peripheral tissues. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1001285. [CrossRef]

- Angers, R.C.; Browning, S.R.; Seward, T.S.; Sigurdson, C.J.; Miller, M.W.; Hoover E.A.; Telling G.C. Prions in skeletal muscle of deer with chronic wasting disease. Science 2006, 311, 1117. [CrossRef]

- Bosque, P.J.; Ryou, C.; Telling, G.; Peretz, D.; Legname, G.; DeArmond, S.J.; Prusiner, S.B. Prions in skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 3812–3817.

- Chen, Z.; Morales, J. E.; Avci, N.; Guerrero, P. A.; Rao, G.; Seo, J. H.; McCarty, J. H., The vascular endothelial cell-expressed prion protein doppel promotes angiogenesis and blood-brain barrier development. Development 2020, 147, dev193094.

- Al-Hilal, T. A.; Chung, S. W.; Choi, J. U.; Alam, F.; Park, J.; Kim, S. W.; Kim, S. Y.; Ahsan, F.; Kim, I. S.; Byun, Y., Targeting prion-like protein doppel selectively suppresses tumor angiogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2016, 126, 1251–66. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. C.; Jeong, B. H., Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) associated polymorphisms of the prion-like protein gene (PRND) in Korean dairy cattle and Hanwoo. J. Dairy Res. 2018, 85, 7–11. [CrossRef]

- Balbus, N.; Humeny, A.; Kashkevich, K.; Henz, I.; Fischer, C.; Becker, C. M.; Schiebel, K., DNA polymorphisms of the prion doppel gene region in four different German cattle breeds and cows tested positive for bovine spongiform encephalopathy. Mamm. Genome 2005, 16, 884–92. [CrossRef]

- Hogan, B.; Constantini, F.; Lacy, E. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1986.

- Niwa, H.; Yamamura, K.; Miyazaki, J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 1991, 108, 193–199.

- Miyazaki, J.; Takai, S.; Araki, K.; Tashiro, F.; Tominaga, A.; Takatsu, K.; Yamamura, K. Expression vector system based on the chicken beta-actin promoter directs efficient production of interleukin-5. Gene 1989, 79, 269–277.

- McKinley, M.P.; Hay, B.; Lingappa, V.R.; Lieberburg, I.; Prusiner, S.B. Developmental expression of prion protein gene. Dev. Biol. 1987, 121, 105–110.

- Bell, J.E.; Gentleman, S.M.; Ironside, J.W.; McCardle, L.; Lantos, P.L.; Doey, L.; Lowe, J.; Fergusson, J.; Luthert, P.; McQuaid, S.; Allen, I.V. Prion protein immunocytochemistry—UK five center consensus report. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1997, 23, 26–35.

- van Keulen, L.J.; Schreuder, B.E.; Meloen, R.H.; Poelen-van den Berg, M.; Mooij-Harkes, G.; Vromans, M.E.; Langeveld, J.P. Immunochemical detection and localization of prion protein in brain tissue of sheep with natural scrapie. Vet. Pathol. 1995, 32, 299–308. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, H.; Tanaka, M.; Iwamaru, Y.; Ushiki, Y.; Kumura, K.M.; Tagawa, Y.; Shinagawa, M.; Yokoyama, T. Effect of tissue deterioration on postmortem BSE diagnosis by immunobiochemical detection of abnormal isoform of prion protein. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2004, 66, 515–520. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).