1. Introduction

Brazil’s commercial dairy herd is of worldwide importance and the state of Minas Gerais, in the southeastern region of Brazil, is particularly noteworthy for its dairy farming (IBGE, 2022). Within the contemporary scenario of ruminant farming, there is a growing emphasis on enhancing production levels while simultaneously ensuring the wellbeing of animals. Gastrointestinal nematode (GIN) control plays a crucial role in addressing both of these essential considerations [

1].

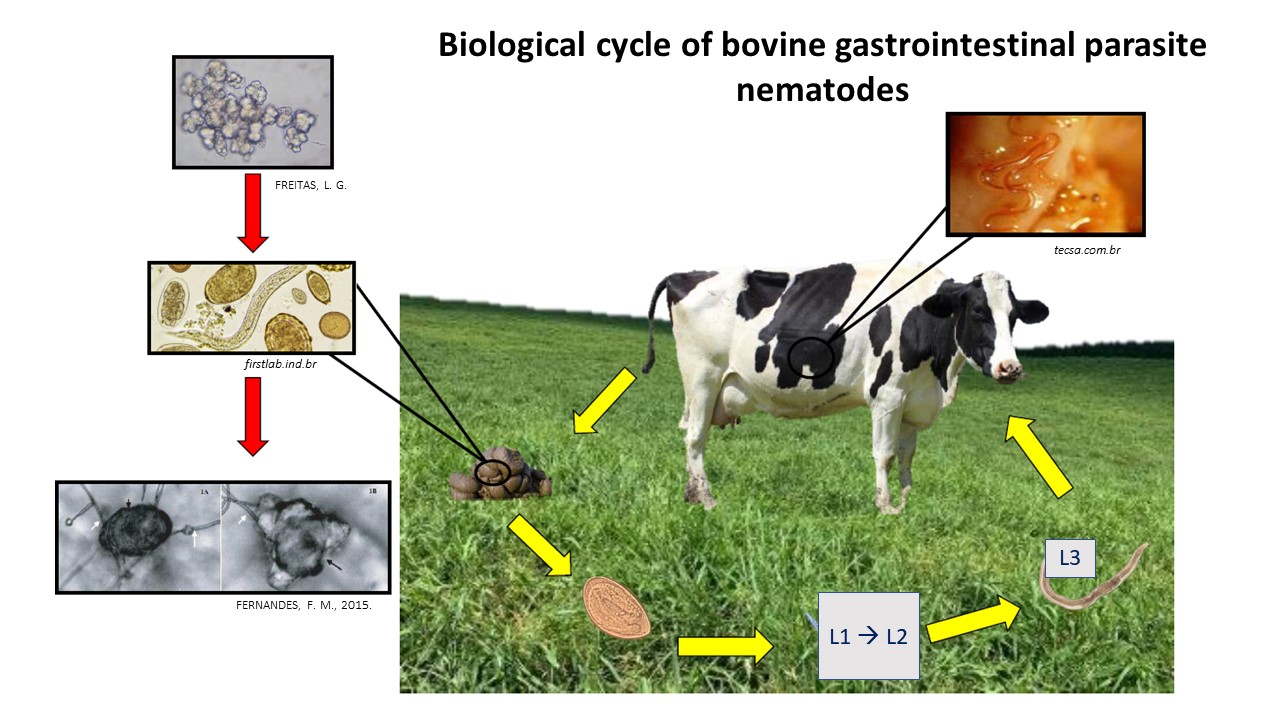

Animals become infected with GINs mainly through exposure to pastures infested with third-stage larvae (L3) [

2]. The main way to control these parasites is through treating animals with anthelmintic drugs [

3,

4] but in many cases these are administered incorrectly, with excessive and indiscriminate use of therapeutic agents. This increases production costs without achieving effective control of infections [

5]. In addition, anthelmintics do not act on the free-living stages of nematodes and can leave harmful residues in animal products [

6].

Protocols for eliminating GINs, such as those of the genera

Haemonchus and

Cooperia, consist of use of drug therapies based on synthetic chemical compounds. However, a wide variety of studies have demonstrated helminth resistance to commercially available drugs [

3,

4,

5]. Control with bioproducts is an alternative for managing cattle nematodes in pastures [

7]. The use of biological control methods involving nematophagous fungi has proven to be a safe and viable alternative [

7,

8,

9] that complements GIN control activities through the action of these fungi in the environment.

Promising results have been obtained with various species of nematophagous fungi, in particular

Duddingtonia flagrans for controlling helminth larvae and

Pochonia chlamydosporia with ovicidal action towards controlling helminth eggs [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

The use of multiple fungal species has been increasingly highlighted in the literature, as it enables the combination of distinct mechanisms of action for the control of helminths. Effective associative use typically requires pairing an ovicidal species with a larvicidal one, such as the interaction between

Duddingtonia flagrans and

Pochonia chlamydosporia. Predatory fungi—including

D. flagrans,

Arthrobotrys spp., and

Monacrosporium spp.—are employed to target infective larval stages in pastures, forming trap-like structures capable of capturing and destroying infective larvae. In contrast, ovicidal fungi such as

P. chlamydosporia,

Mucor circinelloides, and

Paecilomyces lilacinus do not form trapping networks; instead, they penetrate eggs through a mechanical–enzymatic process, subsequently colonizing the internal contents and rendering the eggs unviable [

15].

The ovicidal activity of

P. chlamydosporia, both as a single agent and in association with other fungi, has been demonstrated against eggs from various hosts, under both in vitro and field conditions. Isolates VC1 and VC4 have been widely tested in vitro against eggs of different helminth species, consistently showing high ovicidal efficacy and strong potential for formulation and commercial application. This species is particularly effective against helminths that persist in the environment primarily in the egg stage [

15,

18]. However, Fonseca et al. (2022) reported limited effects of a formulation containing only

P. chlamydosporia in cattle, suggesting that the short duration of the egg stage in pastures may have reduced the opportunity for fungal action. In this context, the association of fungal species with complementary mechanisms of action has shown clear advantages [

19].

The literature indicates that combining two or more fungal species can result in synergistic effects, substantially increasing efficacy without evidence of antagonism between isolates. For example, Carmo et al. (2023) reported successful control of equine gastrointestinal nematodes in field conditions using a combined formulation of

D. flagrans and

P. chlamydosporia [

20]. Similar associations—including

P. chlamydosporia with other larvicidal species—have been proposed by the Brazilian biological control research group at the Federal University of Viçosa. As noted by Tavela et al. (2012), such combinations are promising both for experimental applications and for the development of marketable bioproducts [

21].

Currently, commercial formulations containing

D. flagrans are available, such as BioWorma

® (Australia) and BioVerm

® (Brazil), both designed to control infective larval stages of gastrointestinal nematodes in grazing animals. The development of biological control strategies relies on selecting highly effective fungal isolates, and decades of research have demonstrated the strong individual performance of several species [

22]. Although isolated species may exhibit excellent efficacy, their association represents an even more promising approach, integrating complementary actions and broadening the potential of future formulations.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of two commercial bioproducts, one based on D. flagrans (Bioverm®) and the other consisting of an association between D. flagrans and P. chlamydosporia, for reducing the levels of nematode eggs in animal feces and larval infestations in pastures.

2. Materials and Methods

Two formulations supplied by GhenVet Saúde Animal (Brazil) were used: a formulation based on the fungus D. flagrans (isolate AC001) known as Bioverm®, which contains 106 chlamydospores of the fungus per gram, and an experimental formulation (EF) combining D. flagrans (isolate AC001) and P. chlamydosporia (isolate VC04), containing 106 chlamydospores of each fungus per gram. Individual or combined administration was carried out at a dosage of 6 g/100 kg live weight.

The experiment was conducted on a farm located in the municipality of Abre Campo, state of Minas Gerais, southeastern Brazil, latitude 20° 18’ 04 “S, longitude 42° 28’ 39” W, from February to October 2021.

Initially, for monitoring, feces from 24 animals were collected and processed to determine eggs per gram of feces (EPG) counts on a weekly basis, in accordance with the methods of Gordon and Whitlock [

23] and modifications of Lima [

24] and Dennis, Stone and Swanson [

25]; while pasture forage samples were analyzed on a fortnightly basis, in accordance with the technique described by Raynaud and Gruner [

26] and Lima [

24]. After the initial test, the animals were monitored fortnightly throughout the experiment using the same techniques described above. The infective larvae (L3) were identified in accordance with Keith [

27].

Based on this analysis, eighteen male Holstein-Zebu crossbred cattle, aged between 12 and 15 months, with an average initial weight of 150 kg, which remained at this average weight throughout the experiment, were pre-treated with an anthelmintic suspension of 15% albendazole sulfoxide (Agebendazol®) by injection, in a single dose of 1 mL/44 kg of body weight.

Twenty-one days after anthelmintic treatment, and after confirming the absence of nematode eggs in the feces using the EPG technique of Gordon and Whitlock [

23], a field test was carried out using fungus treatments on naturally infected animals, as described in Ordinance 88 of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply [

28].

The animals were divided according to their average EPG, into three groups of six animals each and separated into three 6-ha paddocks of Brachiaria brizantha, naturally infested with nematode larvae as a result of previous grazing by animals naturally infected with GINs.

In the group that received Bioverm

® (T1), each animal was treated with 6 g of the product for every 100 kg of body weight. The product was administered daily, mixed with 1 kg of maize bran. Group T2 received the experimental formulation (mixed with maize meal), also at a daily dose of 6 g/100 kg body weight. In the control group (C), each animal received maize meal daily, without fungal spores. The animals were monitored fortnightly and the dosage of the products was based on body score and average weight, in accordance with previous studies carried out on the same farm, with the same animals, as described by Vieira

et al. [

12] and Oliveira

et al. [

13].

Every 15 days from the start of the experiment, two samples of

B. brizantha grass were collected (0-20 cm and 20-40 cm away from the feces) in the grazing areas of the treated and control groups, at six different points, as described by Raynaud and Gruner [

26]. Samples of 500 g of pasture forage were used to recover infective larvae (L3) in accordance with the method described by Lima [

24]. The sediment was examined under an optical microscope and the larvae were counted and identified using the criteria established by Keith [

27]. The 500 g samples of grass used were placed in an oven at 100 °C to obtain the dry matter. The data obtained were transformed into the number of larvae per kilogram of dry matter.

The experiment lasted nine months (February to October 2021), during which time animal feces and pasture vegetation were collected fortnightly. The study was also approved by the Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals (CEUA) of the Federal University of Viçosa (UFV), under reference number 37/2020.

Climate data on minimum, average and maximum monthly temperatures and monthly precipitation were obtained from the Agricultural Meteorological Monitoring System (Agritempo), available at the website

https://www.agritempo.gov.br/agritempo/index.jsp. The averages of EPG, L3 recovered from coprocultures, and L3 obtained from pasture samples, as well as the climatic data collected throughout the nine months of the experiment, were organised into monthly values. Subsequently, the EPG, larval migration and body condition score datasets were analysed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) in a split-plot design over time, with parasite managements as main plots and evaluation periods as subplots. When significant effects were detected, Tukey’s test at 5% probability was applied for comparison of means. In addition, treatment efficacy was assessed using the Fecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT). All statistical analyses were performed using SISVAR 5.6.

3. Results

3.1. Body Condition Score (BCS)

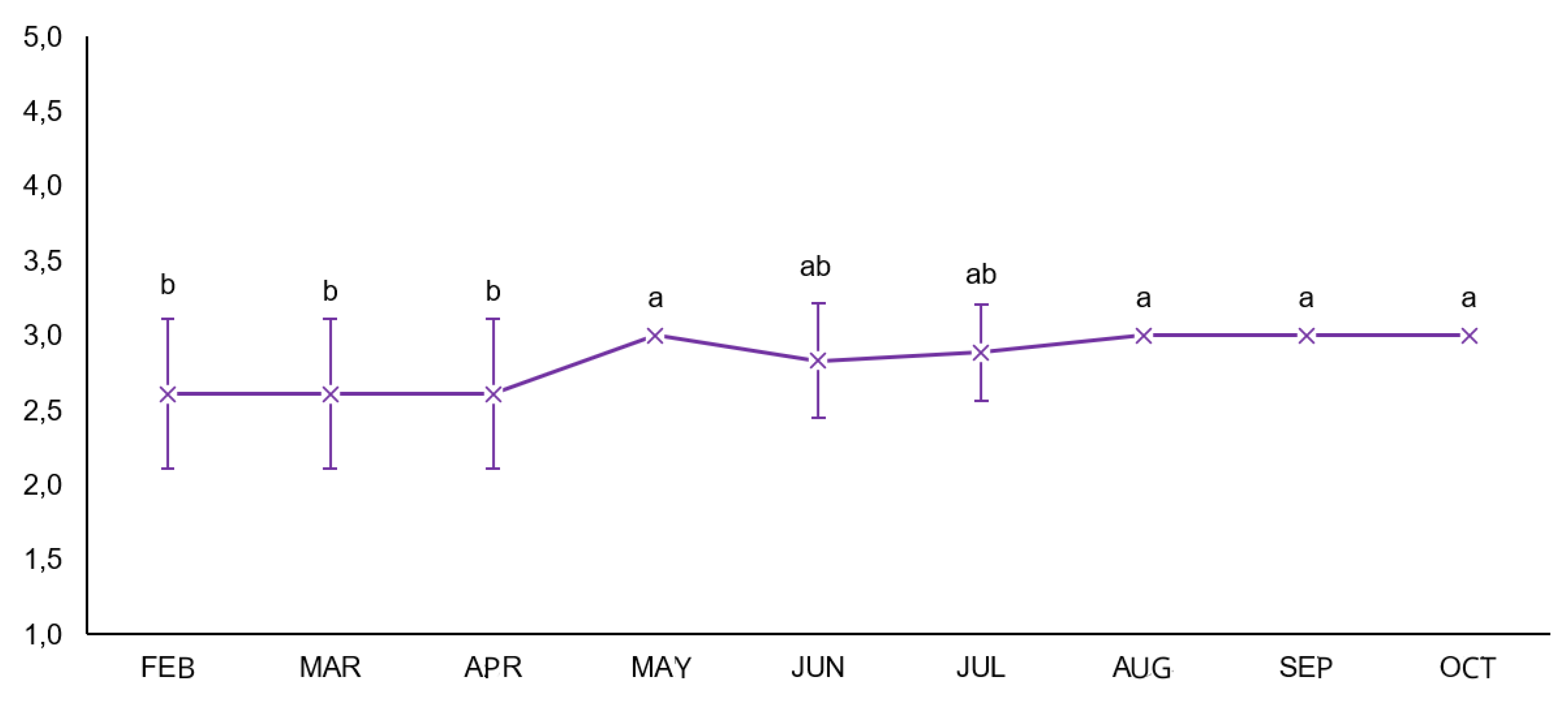

The body condition score results are shown in

Figure 1. In the split-plot ANOVA, no interaction was observed between time and treatment (mean square = 0.025), and no significant differences occurred among the parasite management strategies (mean square = 0.025). Time was the only significant factor (mean square = 0.589), indicating that BCS increased progressively during the evaluation period, regardless of treatment.

3.2. Egg Counting Techniques

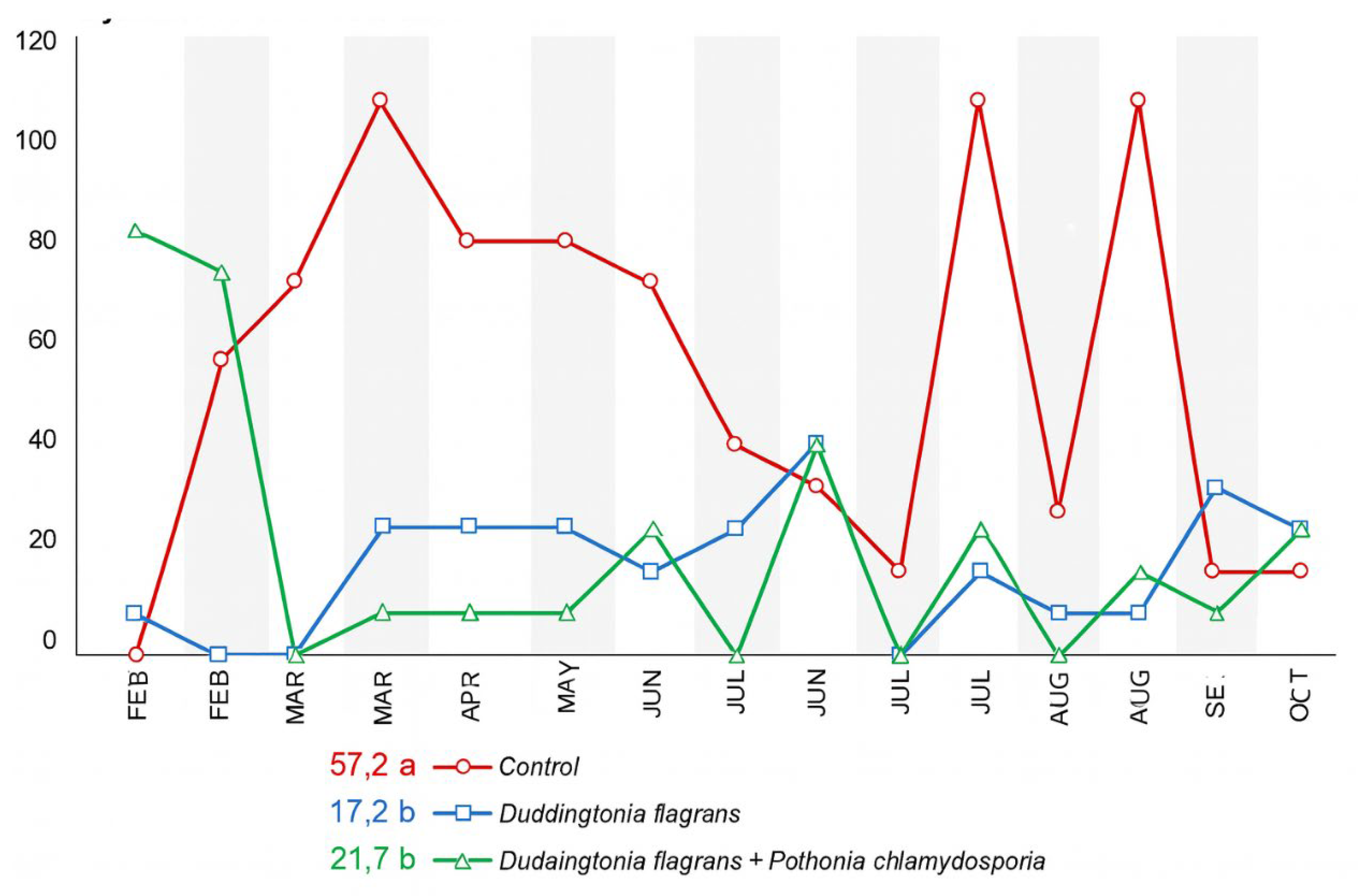

The monthly faecal egg count (EPG) values for the three experimental groups are presented in

Figure 2. According to the ANOVA performed under a split-plot design over time, a significant effect of parasite management was detected (p < 0.01), whereas no interaction between treatment and sampling period was observed.

During the first month of evaluation (February), no statistical differences in EPG were found among the groups. In March, animals receiving Treatment 1 (Duddingtonia flagrans, Bioverm®) exhibited significantly lower EPG values than the control (Tukey, p < 0.05). In April, May and July, both Treatment 1 and Treatment 2 (D. flagrans + Pochonia chlamydosporia) maintained EPG values significantly lower than the control group, demonstrating the efficacy of the isolate and of the fungal association throughout these periods.From June onwards, including August, September and October, EPG values no longer differed statistically among treatments, which coincided with lower climatic favourability for larval development.

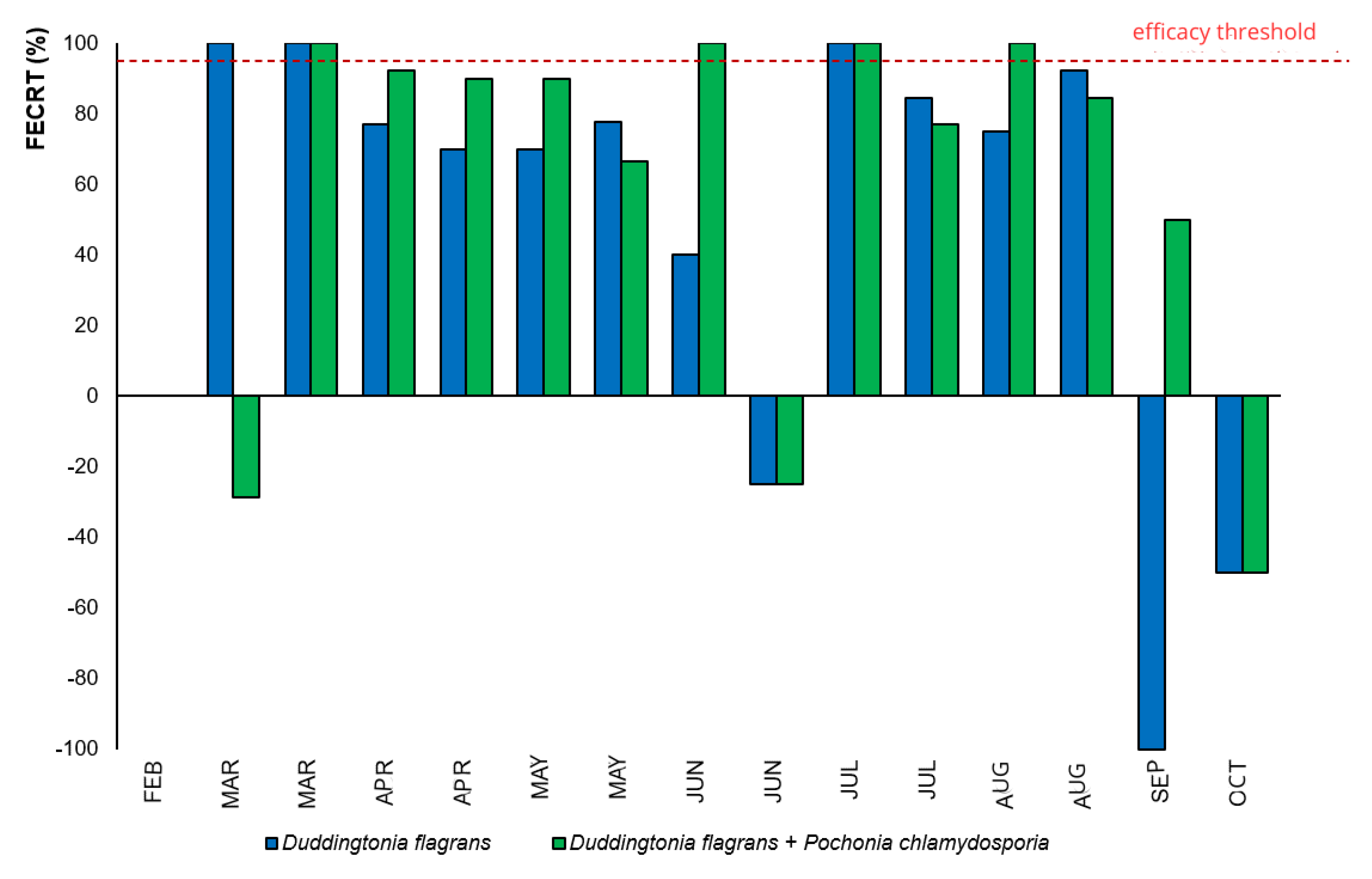

Nevertheless, when evaluated through the Fecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) (

Figure 3), the fungal association (Treatment 2) displayed >95% efficacy during a greater number of months compared to

D. flagrans alone, evidencing enhanced and prolonged suppression of egg shedding due to the synergistic action of both fungi.

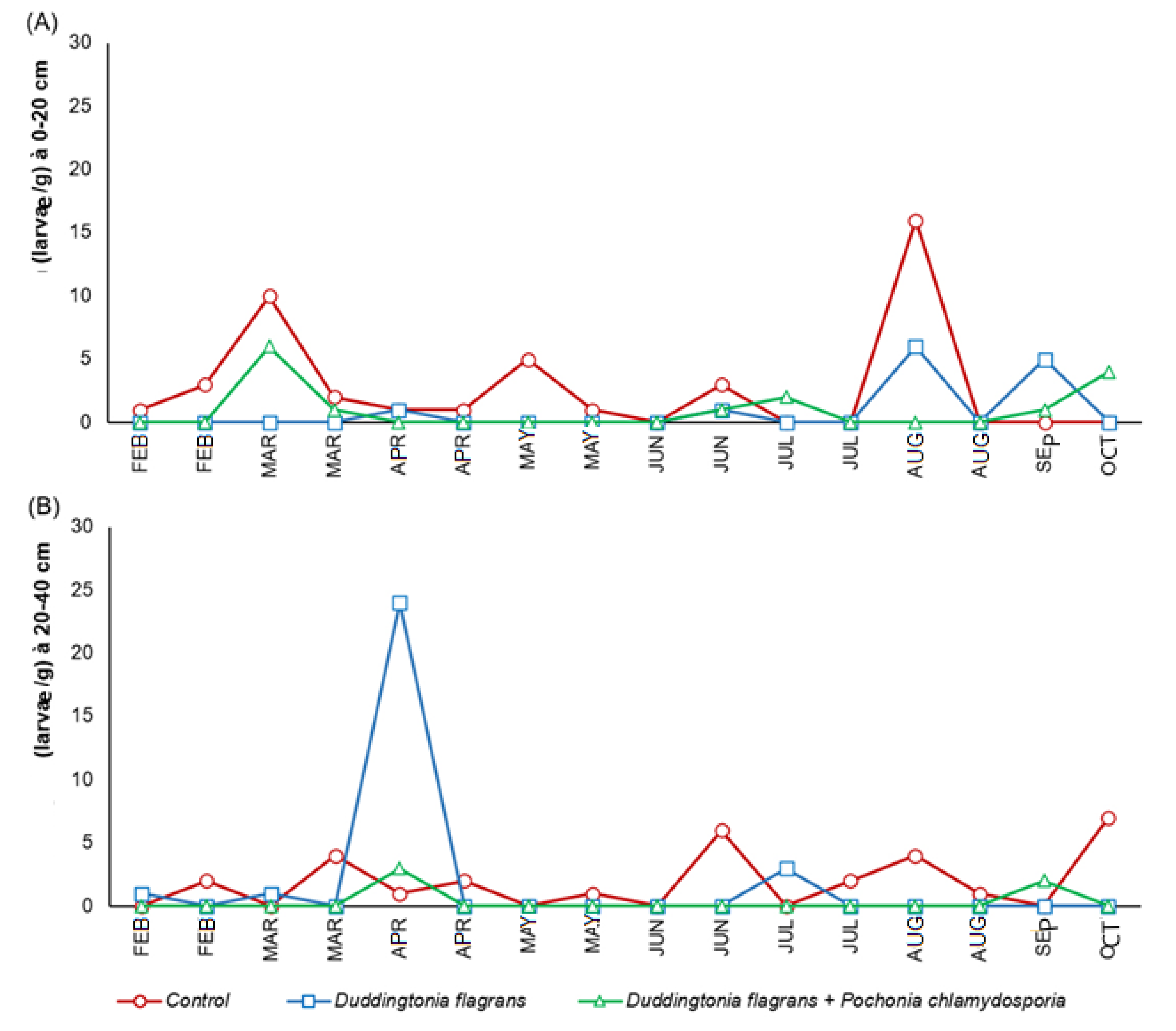

3.3. Larval Recovery Techniques

The quantities of infective L3 larvae obtained from coprocultures are shown in

Figure 4. In Treatment 2 and the control group,

Haemonchus sp.was the predominant genus, followed by

Cooperia sp., throughout most of the experimental period. Notably, after the beginning of the trial, L3 larvae of both genera were no longer detected in Treatment 1 (Bioverm

®), indicating a strong larvicidal activity of

D. flagrans in faecal material.

According to ANOVA (split-plot design), significant differences among treatments were observed for L3 recovery at both distances evaluated (p ≤ 0.05). At 0–20 cm from the faecal mass, Treatment 1 achieved a 69% reduction in larval migration, while the fungal association (Treatment 2) produced a 65% reduction compared to the control. At the greater distance (20–40 cm), Treatment 2 demonstrated markedly superior performance, achieving an 83% reduction in larval migration, in contrast to the minimal reduction observed for Treatment 1 (3%). This finding highlights the importance of incorporating an ovicidal fungus (P. chlamydosporia) to limit larval recruitment into the environment, enhancing the environmental protective effect relative to D. flagrans alone.

3.4. Environmental Conditions

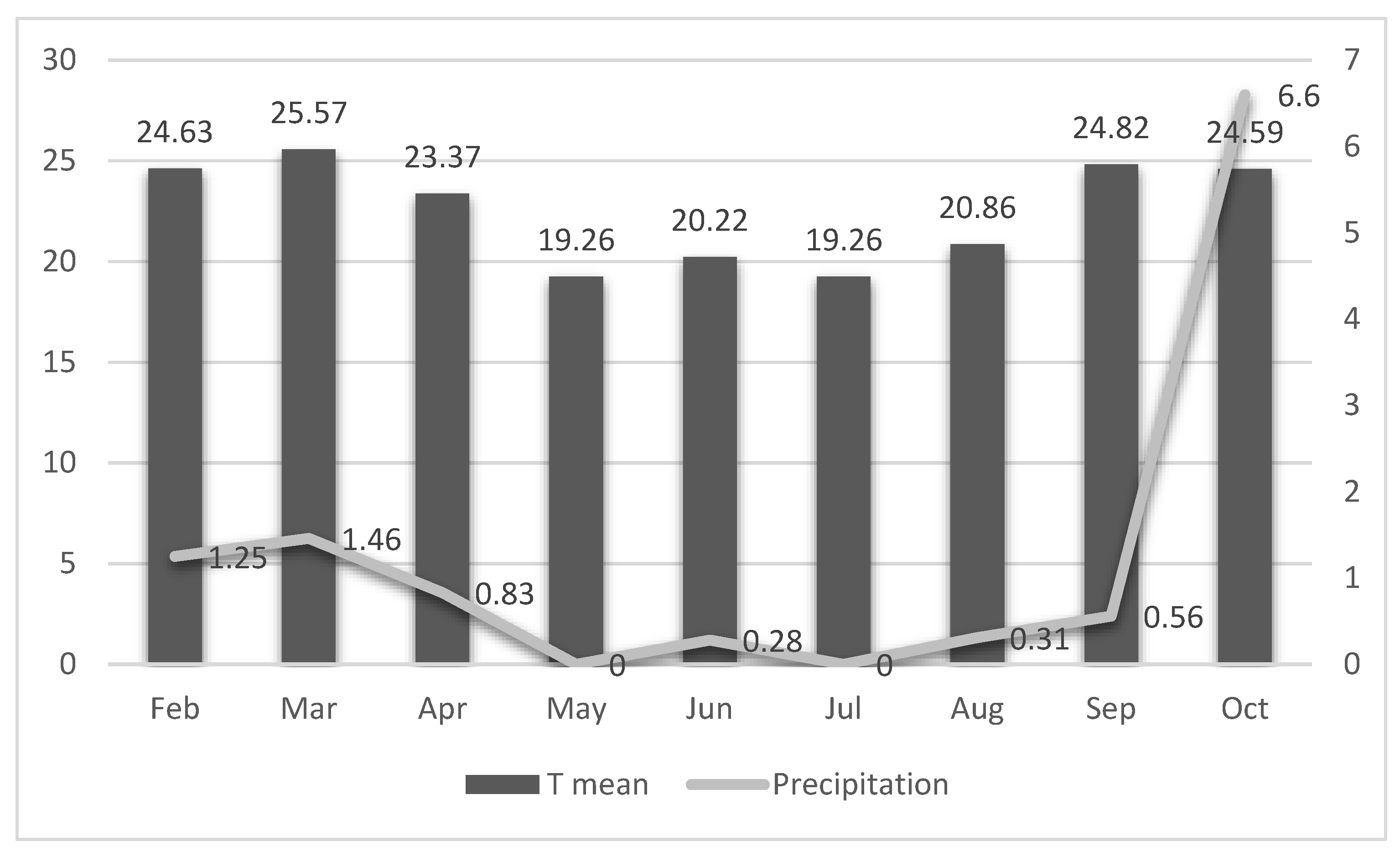

As observed in coprocultures, the larvae recovered from pastures in the early months belonged predominantly to the genera

Haemonchus and

Cooperia. These patterns aligned closely with the climatic conditions recorded during the study period. Monthly minimum, average, and maximum temperatures, along with precipitation data, are shown in

Figure 5.

The lowest temperatures occurred in May and July, with monthly averages ranging from 19.26 °C (July) to 25.57 °C (March). Precipitation was highest in October (6.60 mm³), while the remaining months exhibited low rainfall, ranging from 0 mm³ (July) to 1.46 mm³ (March).

These climatic variables likely influenced the dynamics of larval development and dispersion in the pasture throughout the experiment.

4. Discussion

The progressive increase in body condition score (BCS) observed throughout the study (

Figure 1), regardless of treatment, suggests that cattle maintained adequate nutritional status during the experimental period. The overall improvement in BCS aligns with previous observations on the same farm, where fungal biological control contributed indirectly to maintaining animal performance and weight gain by reducing parasitic pressure [

11,

12]. These authors reported that even moderate reductions in environmental larval availability can help sustain productive indicators such as body weight and condition in grazing cattle—consistent with the pattern observed in the present study, where fungal treatments supported a low parasitic challenge that allowed normal physiological recovery over time.

Epidemiological surveys by Kenyon et al. [

29] and Franco et al. [

30] indicate that gastrointestinal nematodes are present in approximately 95% of pastures, a finding consistent with the results of the present study.

Haemonchus and

Cooperia were the predominant genera identified in coprocultures, in agreement with previous studies conducted in Brazil [

10,

11,

12,

13]. These nematodes remain among the most pathogenic for cattle, given their well-established association with anemia, reduced nutrient absorption and mortality [

31,

32].

The initial decline in faecal egg counts (EPG) across all groups can be attributed to the anthelmintic protocol applied before the trial, as such drugs effectively remove adult parasites and their eggs [

4]. Once cattle returned to pasture without further chemical intervention, reinfection occurred, especially in the control group (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Nonetheless, EPG values remained low in all treatments, likely reflecting host age, immunological resistance and reduced environmental larval availability—conditions that provided a suitable baseline for evaluating fungal biocontrol.

The experimental design followed MAPA guidelines [

28], which establish a controlled framework for assessing antiparasitic interventions in Brazil. However, because no regulatory standards exist for biological control products, studies such as this are essential to support their application in sustainable parasite management.

Helminthophagous fungi have been repeatedly validated as efficient biological control tools [

14,

15,

16,

17,

20]. Their oral administration is advantageous because fungal propagules reach the fecal mass—the environment in which nematode eggs hatch and larvae develop—allowing the fungi to either disrupt egg embryonation or trap and kill larvae [

33,

34]. In this study, both

D. flagrans alone and its combination with

P. chlamydosporia reduced EPG compared with the control during specific evaluation months, and both treatments markedly decreased L3 counts on pastures (

Figure 4). These results are in line with previous trials conducted on the same farm using other fungal formulations [

12,

13]. Moreover, the combined activity of

D. flagrans and

P. chlamydosporia has also been demonstrated in horses, where significant reductions in infective small strongyle larvae were observed [

20].

The low environmental contamination observed throughout the study mirrors earlier findings obtained using

A. cladodes and

P. chlamydosporia in alginate pellets, which exhibited residual effects in pastures and markedly reduced egg deposition [

12]. The consistency among studies reinforces that fungal control depends on the complementary modes of action of each species and the developmental stage they target.

Effective gastrointestinal nematode control requires simultaneous interruption of both the parasitic (host) and free-living (environmental) phases [

33,

35]. Here, reductions in both EPG and pasture L3 counts confirm fungal activity in the free-living stage, which is essential for reducing reinfection pressure in grazing systems. Lower environmental larval availability is particularly valuable because it creates a long-term reduction in parasite cycling.

The success of

D. flagrans in this study is consistent with its biological characteristics. This species forms chlamydospores capable of withstanding gastrointestinal transit and being dispersed through feces [

7,

12,

33,

36,

37]. Once released into feces,

D. flagrans forms trapping structures that ensnare and destroy newly hatched larvae—explaining the absence of L3 in coprocultures from animals treated with this fungus [

34,

38].

P. chlamydosporia, in turn, is an established ovicidal species [

39]. Through enzymatic degradation and hyphal penetration, it disrupts helminth egg embryogenesis [

17,

40]. The reduction in EPG observed in the combination treatment highlights the complementarity between the ovicidal mechanisms of

P. chlamydosporia and the larvicidal action of

D. flagrans, evidencing a synergistic interaction. This synergy likely contributed to sustained reductions in pasture contamination, even under fluctuating climatic conditions.

Environmental factors also shaped parasite dynamics. Pasture height ranged from 15 to 80 cm, influencing microclimatic conditions that directly affect larval survival and fecal degradation [

41]. Temperature and precipitation patterns play a central role in larval development [

42]. Optimal temperatures for

Haemonchus and

Cooperia larvae (13–26 °C) [

32] were exceeded during six of the nine months of assessment (

Figure 5), and rainfall remained low during autumn and winter, conditions that likely reduced overall larval viability across treatments. Because water availability is essential for L3 migration from feces to forage [

42,

43] the observed climatic pattern contributed to a general decline in pasture infectivity. Even so, significant differences between treated and untreated groups confirm that the fungi—alone or combined—acted consistently to suppress environmental larval loads.

Given that extensive grazing predominates in Brazilian ruminant production, fungal bioproducts represent a valuable component of integrated parasite management. By reducing pasture contamination and reinfection pressure, they mitigate productivity losses associated with helminthiasis and help decrease reliance on chemical anthelmintics, supporting more sustainable livestock systems.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the use of the nematophagous fungus D. flagrans (Bioverm®), either alone or combined with P. chlamydosporia, effectively reduced faecal egg counts and pasture larval contamination. While both treatments contributed to lowering parasite burden, the combined formulation demonstrated a markedly enhanced effect, as it integrates two complementary modes of action—larvicidal activity from D. flagrans and ovicidal activity from P. chlamydosporia. This synergistic interaction resulted in broader and more consistent suppression of gastrointestinal nematodes. Therefore, fungal associations represent a superior and innovative strategy for sustainable, integrated helminth control in ruminant production systems, offering greater biological efficacy than single-fungus approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jackson Victor Araújo; methodology, Wagner Nunes Rodrigues; investigation, Maria Larissa Bitencourt Vidal and Ítalo Stoupa Vieira; data curation, Isabella Vilhena Freire Martins; writing—original draft preparation, Júlia dos Santos Fonseca, Lorena Castro Altoé and Lorendane Millena de Carvalho; writing—review and editing, Maria Larissa Bitencourt Vidal and Jackson Victor Araújo; supervision, Jackson Victor Araújo; project administration, Maria Larissa Bitencourt Vidal. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was also approved by the Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals (CEUA) of the Federal University of Viçosa (UFV), under reference number 37/2020.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the ‘Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico’ (CNPq) and ‘Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais’ (FAPEMIG) Coordenação para o Aperfeiçoamento do Pessoal do Ensino Superior’ (CAPES) for their support in this study, in the form of a PhD scholarship and the Veterinary Department of the Universidade Federal de Viçosa.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article. There are no financial, personal or professional ties that could influence the objectivity or integrity of the work presented. This article was prepared independently, based on impartial research and analysis.

References

- Grisi, L.; Leite, R.C.; Martins, J.R.d.S.; de Barros, A.T.M.; Andreotti, R.; Cançado, P.H.D.; de León, A.A.P.; Pereira, J.B.; Villela, H.S. Reassessment of the potential economic impact of cattle parasites in Brazil. Rev. Bras. De Parasitol. Veter- 2014, 23, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi-Storm, N.; Moakes, S.; Thüer, S.; Grovermann, C.; Verwer, C.; Verkaik, J.; Knubben-Schweizer, G.; Höglund, J.; Petkevičius, S.; Thamsborg, S.; et al. Parasite control in organic cattle farming: Management and farmers’ perspectives from six European countries. Veter- Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2019, 18, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, M.L.B.; Viana, M.V.G.; Ito, M.; Trivilin, L.O.; Martins, I.V.F. (2019). Anti-helmínticos de importância veterinária no Brasil. In Tópicos Especiais em Ciência Animal VIII; CAUFES: Alegre, Brazil; pp. 273–297.

- Kaplan, R.M. Biology, Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Anthelmintic Resistance in Gastrointestinal Nematodes of Livestock. Veter- Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pr. 2020, 36, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, F.E.d.F.; Lima, W.d.S.; da Cunha, A.P.; Bello, A.C.P.d.P.; Domingues, L.N.; Wanderley, R.P.B.; Leite, P.V.B.; Leite, R.C. Verminoses dos bovinos: percepÇão de pecuaristas em Minas Gerais, Brasil. Rev. Bras. De Parasitol. Veter 2009, 18, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindicato Nacional da Indústria de Produtos para Saúde Animal (SINDAN). Mercado Nacional de Produtos para Saúde Animal. 2018. Available online: http://www.sindan.org.br/mercado-brasil-2018/ (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Braga, F.R.; Ferraz, C.M.; Silva, E.; Araújo, J. Efficiency of the Bioverm (Duddingtonia flagrans) fungal formulation to control Haemonchus contortus and Strongyloides papillosus in sheep. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luns, F.D.; Assis, R.C.L.; Silva, L.P.C.; Ferraz, C.M.; Braga, F.R.; de Araújo, J.V. Coadministration of Nematophagous Fungi for Biological Control over Nematodes in Bovine in the South-Eastern Brazil. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilela, V.L.R.; Feitosa, T.F.; Braga, F.R.; Vieira, V.D.; de Lucena, S.C.; de Araújo, J.V. Control of sheep gastrointestinal nematodes using the combination of Duddingtonia flagrans and Levamisole Hydrochloride 5%. Rev. Bras. De Parasitol. Veter 2018, 27, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonza-de-Gives, P.; López-Arellano, M.A.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L.; Olazarán-Jenkins, S.; Reyes-Guerrero, D.; Ramírez-Várgas, G.; et al. The nematophagous fungus Duddingtonia flagrans reduces gastrointestinal parasitic nematode larvae in calves under tropical conditions: Dose–response assessment. Vet. Parasitol. 2018, 263, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, I.C.; Vieira, I.S.; Carvalho, L.M.; Campos, A.K.; Freitas, S.G.; Araujo, J.M.; et al. Reduction of bovine strongylids in naturally contaminated pastures in Southeastern Brazil. Exp. Parasitol. 2018, 194, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, I.S.; Oliveira, I.C.; Freitas, S.G.; Campos, A.K.; Araújo, J.V. Arthrobotrys cladodes and Pochonia chlamydosporia in biological control of nematodiosis in extensive bovine systems. Parasitology 2020, 147, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.d.C.; Vieira, Í.S.; Freitas, S.G.; Campos, A.K.; Araújo, J.V. Monacrosporium sinense and Pochonia chlamydosporia for the biological control of bovine infective larvae in Brachiaria brizantha pasture. Biol. Control. 2022, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J.V. Advances in the control of helminthiases in domestic animals. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, F.R.; Araújo, J.V. Nematophagous fungi for biological control of gastrointestinal nematodes in domestic animals. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gives, P.M.-D.; Braga, F.R.; de Araújo, J.V. Nematophagous fungi, an extraordinary tool for controlling ruminant parasitic nematodes and other biotechnological applications. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2022, 32, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J.V.; Braga, F.R.; Mendoza-De-Gives, P.; Paz-Silva, A.; Vilela, V.L.R. Recent Advances in the Control of Helminths of Domestic Animals by Helminthophagous Fungi. Parasitologia 2021, 1, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, J.d.S.; Altoé, L.S.C.; de Carvalho, L.M.; Soares, F.E.d.F.; Braga, F.R.; de Araújo, J.V. Nematophagous fungus Pochonia chlamydosporia to control parasitic diseases in animals. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 3859–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, J.D.; Ferreira, V.M.; Freitas, S.G.; Vieira, I.S.; Araujo, J.V. Efficacy of Pochonia chlamydosporia fungal formulation for bovine nematodiosis control. Pathogens 2022, 11, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, T.A.; Mena, M.O.; Cipriano, I.A.; et al. Biological control of equine gastrointestinal nematodes using Duddingtonia flagrans and Pochonia chlamydosporia. Biol. Control 2023, 182, 105219. [Google Scholar]

- Tavela, A.O.; Araujo, J.V.; Braga, F.R.; Araújo, J.M.; Magalhaes, L.Q.; Silveira, W.F.; Borges, L.A. In vitro association of D. flagrans, M. thaumasium and P. chlamydosporia to control horse cyathostomins. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2012, 22, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, J.M.; de Araújo, J.V.; Braga, F.R.; Carvalho, R.O.; Ferreira, S.R. Activity of the nematophagous fungi Pochonia chlamydosporia, Duddingtonia flagrans and Monacrosporium thaumasium on egg capsules of Dipylidium caninum. Veter-Parasitol. 2009, 166, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.M.; Whitlock, H.V. A new technique for counting nematode eggs in sheep feces. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 1939, 12, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, W.S. Dinâmica das populações de nematoides. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, W.R.; Stone, W.M.; Swanson, L.E. A new laboratory and field diagnostic test for fluke ova in feces. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1954, 124, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Raynaud, J.P.; Gruner, L. Feasibility of herbage sampling in extensive grazing. Vet. Parasitol. 1982, 10, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keith, R.K. Differentiation of infective larvae of cattle nematodes. Aust. J. Zool. 1953, 1, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento. (1997). Portaria nº 48, de 12 de maio de 1997. Diário Oficial da União, Seção 1, p. 10165.

- Kenyon, F.; Greer, A.W.; Coles, G.C.; Cringoli, G.; Papadopoulos, E.; Cabaret, J.; et al. Role of selective treatments in refugia-based control. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 164, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, B.; Alberto, F.L.; Federica, S.M.; Emilia, I.L.; Silvina, F.A.; Sara, Z.; et al. Predatory effect of D. flagrans on infective larvae. Exp. Parasitol. 2018, 193, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Girão, E.S.; Leal, J.A.; Girão, R.N.; Medeiros, L.P. (1999). Verminose bovina. Embrapa Meio Norte, Documentos 41, 30 p.

- Heckler, R.P.; Borges, F.A. Climate variations and nematode populations. Nematoda 2016, 3, e02016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, D.; Gong, J.; Zhang, Y. Individual and combined application of nematophagous fungi for GIN control. Pathogens 2022, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.A.; Roque, F.L.; Alvares, F.B.V.; da Silva, A.L.P.; de Lima, E.F.; Filho, G.M.D.; et al. Efficacy of Bioverm® for bovine nematodes. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2021, 30, e026620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Acosta, J.F.L.; Hoste, H. Alternative methods to limit parasitism in small ruminants. Small Rumin. Res. 2008, 77, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronvold, J.; Henriksen, S.A.; Larsen, M.; Nansen, P.; Wolstrup, J. Biological control in livestock. Vet. Parasitol. 1996, 64, 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Buzatti, A.; Santos, C.P.; Fernandes, M.A.M.; Yoshitani, U.Y.; Sprenger, L.K.; Santos, C.D.; et al. D. flagrans in horses. Exp. Parasitol. 2015, 159, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, F.R.; Araújo, J.; Campos, A.K.; Silva, A.R.; Araujo, J.M.; Carvalho, R.O.; et al. In vitro evaluation of nematophagous fungi on Schistosoma mansoni eggs. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 24, 2713–2716. [Google Scholar]

- Ayupe, T.H. Arthrobotrys cladodes var. macroides e P. chlamydosporia como controladores. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Llorca, L.V.; Olivares-Bernabeu, C.; Salinas, J.; Jansson, H.-B.; Kolattukudy, P.E. Pre-penetration events in fungal parasitism of nematode eggs. Mycol. Res. 2002, 106, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R.A.; Rocha, G.P.; Bricarello, P.A.; Amarante, A.F.T. Recovery of T. colubriformis larvae from grasses. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2008, 17, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quadros, D.G.; Sobrinho, A.G.S.; Rodrigues, L.R.A.; Oliveira, G.P.; Xavier, C.P.; Andrade, A.P. Effect of forage species on vertical distribution of infective larvae. Ciênc. Anim. Bras. 2012, 13, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, J.; Morgan, E.R. Influence of water on migration of infective larvae. Parasitology 2011, 138, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).