1. Introduction

The flavin cofactors flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) are essential for numerous metabolic processes for all organisms. Photosynthesis, photorespiration, mitochondrial electron transport, nitrogen assimilation and cellular redox homeostasis in plants depend on flavins [

1]. The precursor of FMN and FAD is riboflavin (vitamin B2), which is synthesized in plants and microorganisms, whereas animals depend entirely on dietary intake to meet their demands. In plants, FMN and FAD cofactors are essential for growth under normal conditions and in various stress responses [

2]. Although the riboflavin metabolic pathway has been largely elucidated at the biochemical level, there is a lack of comprehensive information regarding flavins transcriptional regulation. Understanding the spatiotemporal expression patterns of genes involved in riboflavin synthesis across developmental stages and in response to external stimuli, is critical to understand flavin metabolism control in the plant body. Moreover, information on the subcellular localization of flavins metabolic enzymes is crucial, especially for targeted approaches aiming to genetically modify the pathway for biotechnological applications and stimulate flavin coenzyme availability for metabolic engineering or enhancing plant stress resilience and adaptation. Post-genomic era resulted in advancement of high-throughput technologies generating vast quantities of omics data across model and diverse plant species [

3]. The availability of these datasets significantly enhances reproducibility and cross-study validation, making them indispensable assets for both fundamental research and translational applications in agriculture.

In this study, we elucidate the transcriptional regulation and dynamics of the riboflavin metabolism pathway in Arabidopsis by integrating diverse high-throughput gene expression datasets within developmental and subcellular contexts. The pathway genes exhibit distinct spatial and temporal expression profiles across developmental stages and plant organs. Our analysis further reveals a coordinated transcriptional reprogramming of the riboflavin pathway that maintains flavin homeostasis under osmotic and salt stress conditions, where fluctuations in flavin levels occur. Given the central role of metabolic pathway gene regulation in plant adaptation and metabolic engineering, our findings provide a valuable framework for future biotechnological applications targeting flavin metabolism.

2. Methods

2.1. Databases and Tools

Genes involved in the riboflavin metabolism pathway in

Arabidopsis thaliana were annotated based on Gerdes et al. (2012) [

4], the KEGG database [

5] and relevant literature. A complete list of the annotated genes is provided in

Supplementary Table S1.

Spatiotemporal expression analysis of the riboflavin pathway genes was conducted using RNA-seq data retrieved from the Transcriptional Variation Analysis database (TraVAdb) [

6]. Expression values were normalized (0–1) based on trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) normalization. For each gene in the riboflavin pathway, expression profiles were also obtained using the ATHENA (Arabidopsis thaliana Expression Atlas) platform [

7]. ATHENA provides access to quantitative transcriptomic and proteomic data from 30 matched

Arabidopsis thaliana (

Col-0) tissues, comprising more than 25,000 transcripts and 18,000 proteins. Transcript levels are expressed as transcripts per million (TPM), and protein abundance is reported as intensity-based absolute quantification (iBAQ) values. To identify the

cis elements within the promoter regions (-1500bp to +100bp relative to the translation initiation codon) of the riboflavin metabolism pathway genes the PlantCARE database was utilized [

8]. For the expression profile analysis of the Arabidopsis riboflavin pathway genes under abiotic stresses, gene expression values were retrieved from the ePlant database [

9] and were used to generate heatmaps based on their normalized expression levels. Heatmaps were generated using TBtools II (v2.326) [

10]. To construct the co-expression network of riboflavin pathway genes, co-expression data were retrieved from ATTED-II (version 12.0). For each gene, the top 100 most highly co-expressed genes were extracted and merged into a single dataset. The final network was visualized using Cytoscape (version 3.10.3); nodes with only one connection (degree = 1) were filtered out to improve clarity and interpretability.

2.2. Extraction and Quantification of Flavins

Arabidopsis thaliana seeds were surface-sterilized and sown in Petri dishes containing 0.5× Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (Duchefa, Netherlands), pH 5.7, supplemented with 1% sucrose, 0.05% 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid (MES; AppliChem GmbH, Germany), and solidified with 0.33% phytagel (Sigma, UK). Seeds were stratified for 48 h at 4 °C and subsequently grown for 7 days at 22 °C in a Fitotron growth chamber (Weiss Gallenkamp, UK) under long-day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark) with a light intensity of 120 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹. For salt and osmotic stress treatments, seedlings were transferred to the same medium supplemented with 100 mM NaCl and 300 mM mannitol, respectively, and maintained under identical growth conditions. Seedlings were homogenized in flavin extraction solution (methanol:methylene chloride, 9:10 v/v) at 20 µL mg⁻¹ fresh tissue. A 0.1 M ammonium acetate solution, pH 6.0 (9 parts), was added to the extraction solution (19 parts) and vortexed for 2 min. Samples were centrifuged at 16,000 g at 4 °C, and flavins in the aqueous phase were analyzed using a Jasco HPLC system (Pump PU-4180, Autosampler AS4050, FP2020 Plus) equipped with a Spherisorb ODS2 column (5 µm, 4.6 × 250 mm; Waters). The mobile phase consisted of methanol:0.01 N NaH₂PO₄ pH 5.5 (3:7 v/v). A 20 µL sample was injected and eluted at a flow rate of 1 mL min⁻¹. Flavins were detected with excitation at 445 nm and emission at 530 nm. Peak identification and quantification were performed using authentic standards of riboflavin (PHR1054, Supelco), FMN (F8399), and FAD (F6625) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

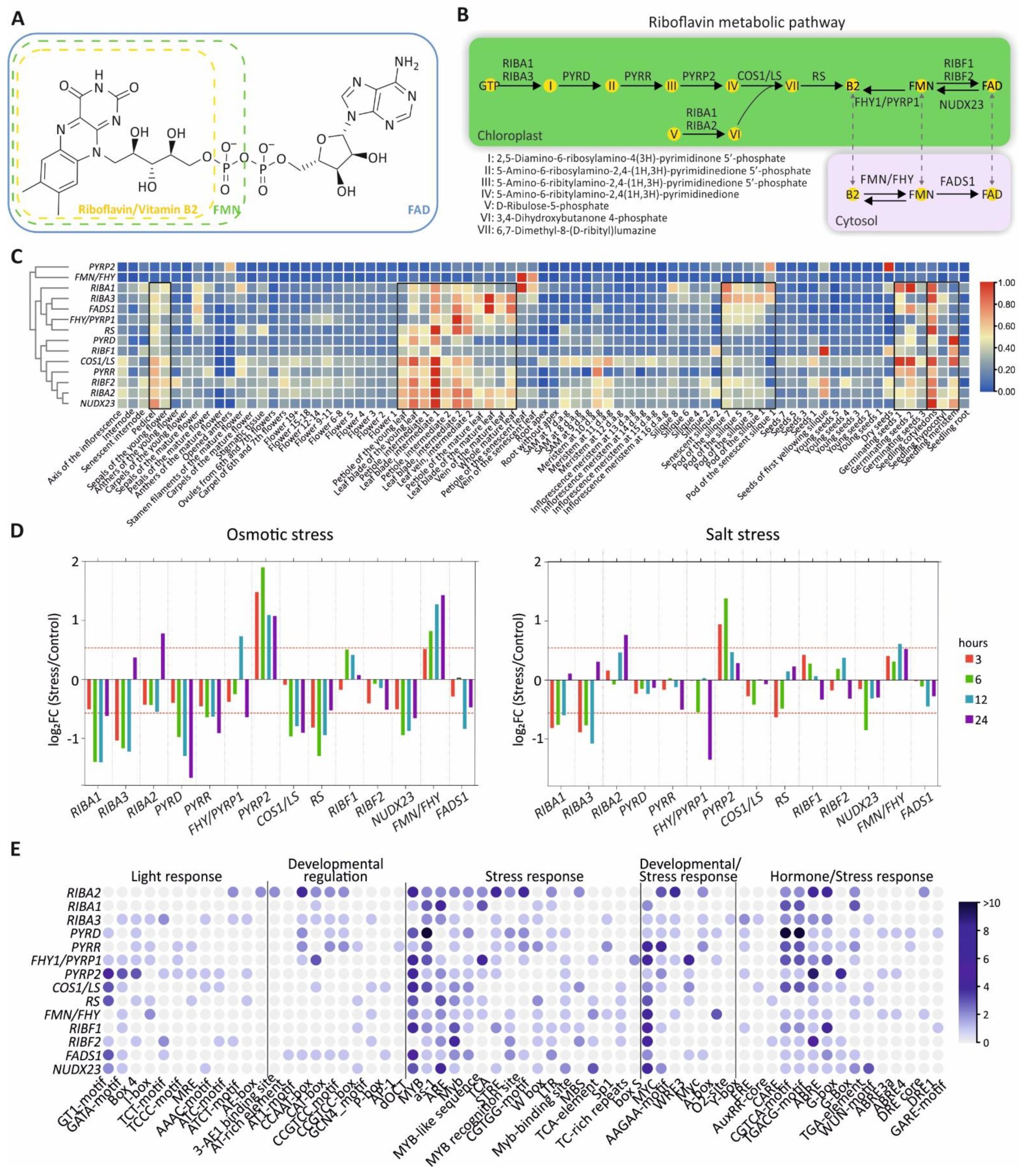

3.1. Riboflavin Metabolic Pathway

Riboflavin consists of a tricyclic isoalloxazine ring linked to a ribitol side chain, which upon phosphorylation by riboflavin kinase forms FMN (

Figure 1A). FAD synthetase subsequently converts FMN to FAD by adding an adenosine monophosphate, subsequently converts FMN to FAD. In plants, riboflavin biosynthesis is initiated from GTP or ribulose-5-phosphate (Ru5P) as precursor molecules and proceeds through seven enzymatic steps within chloroplasts (

Figure 1B and

Supplementary Table S1). The first step is catalyzed by bifunctional RIBA enzymes, which possess both GTP cyclohydrolase II (GCHII) and 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase (DHBPS) activities [

11]. In Arabidopsis, three RIBA isoforms have been identified. RIBA1 retains both enzymatic activities, whereas RIBA2 lacks GCHII activity and RIBA3 lacks DHBPS activity, due to mutations in conserved peptide domains critical for these catalytic functions [

11] (

Figure 1B and

Supplementary Table S1). PYRD, a pyrimidine deaminase, catalyzes the deamination of the pyrimidine ring of 2,5-diamino-6-ribosylamino-4(3H)-pyrimidinone 5’-phosphate, producing 5-amino-6-ribosylamino-2,4(1H,3H)-pyrimidinedione 5’-phosphate. Subsequently, PYRR, which is a pyrimidine reductase, reduces the ribosyl moiety to generate 5-amino-6-ribitylamino-2,4(1H,3H)-pyrimidinedione 5’-phosphate [

12]. This intermediate is dephosphorylated

in vitro by AtcpFHy/PyrP1 and AtPyrP2 enzymes, with AtPyrP2 shown to be the primary enzyme responsible for this reaction

in planta [

13]. The next step is catalyzed by lumazine synthase (COS1/LS), which combines DHBP and 5-Amino-6-ribitylamino-2,4(1H,3H)-pyrimidinedione into 6,7-Dimethyl-8-(D-ribityl) lumazine [

14]. Riboflavin is then synthesized by Riboflavin Synthase (RS) and subsequently converted to FMN and FAD. In plants, the bifunctional FMN hydrolase/FHY enzyme, which converts riboflavin to FMN, has been characterized and potentially resides in the cytosol [

15] (

Figure 1B and

Supplementary Table S1). Notably, the FMN/FHY enzyme also catalyzes the dephosphorylation of FMN to riboflavin

in vitro, due to FMN hydrolase activity, a function similarly performed by the chloroplast-localized AtcpFHy/PyrP1 enzyme [

16]. FAD is synthesized by RIBF1 and RIBF2 in chloroplasts and by FADS1 in the cytosol [

17,

18]. In addition, NUDX23 exhibits FAD pyrophosphohydrolase activity, hydrolyzing FAD to FMN in chloroplasts [

19].

3.2. Spatiotemporal Expression of Riboflavin Metabolic Pathway Genes

High-resolution maps, such as the TraVA database [

6] and the integrative proteomic–transcriptomic atlas ATHENA [

7], provide robust frameworks for systems-level functional genomics. To comprehend the spatiotemporal expression of the genes encoding enzymes of the flavin metabolism pathway, we analyzed RNA-seq data from the TraVA database across diverse developmental stages and organs [

6] (

Figure 1C and

Supplementary Table S2). Most genes are highly expressed in leaf developmental stages and organs, as well as in pedicel, sepals, seeds, siliques and seedlings, while maintaining uniformly low levels of expression in other developmental stages and organs (

Figure 1C). These findings are also consistent with previous reports showing that riboflavin tends to accumulate in leaves and seeds across various species [

20]. In addition,

RIBF1 expression peaked in seeds of the first yellowing silique, whereas

PYRP2 and

FMN/FHY steadily displayed low expression across all organs and stages and were highly expressed only in dry seeds and senescent leaves, respectively (

Figure 1C). Hierarchical clustering showed discrete modules regarding

RIBA1,

RIBA3,

FADS,

FHY/PYRP1 and

RS that form a tight cluster,

FMN/FHY grouped with

PYRP2,

RIBA2 clustered with

NUDX23, while

PYRD associated with

RIBF1 (

Figure 1C).

Further, ATHENA tool that integrates RNA-seq and mass spectrometry–based proteomics data from thirty distinct tissues was employed to simultaneously analyze both transcriptional and translational profiles of the enzymes involved in flavin biosynthesis pathway across Arabidopsis tissues. A scatterplot comparing intensity-Based Absolute Quantification (iBAQ) and Transcripts Per Million (TPM) values confirmed a clear enrichment of most enzymes in leaves and seeds, while also demonstrating that these enzymes are detectable across all Arabidopsis tissues (

Supplementary Figure S1). This observation is consistent with TraVA results, further supporting that the majority of flavin biosynthesis genes and enzymes are predominantly expressed and accumulated in leaves and seeds. Hierarchical clustering of proteomics data based on iBAQ values revealed distinct patterns of protein accumulation among the enzymes of flavin biosynthesis pathway. Notably, RIBA1, RIBA3, FADS1, RIBF2 formed a tight cluster, closely resembling the clustering pattern observed at the transcriptomic level (

Supplementary Figure S2). Based on both proteomic and transcriptomic data, an additional cluster was formed by FMN/FHY and PYRP2, whereas the rest of flavin biosynthesis enzymes grouped separately. Taken together, these results support a modular co-regulation pattern of flavin biosynthetic genes, highlighting coordinated yet distinct regulatory circuits relative to plant development and organ identity. Most genes show evident stimulation of expression in major metabolic sinks for flavins, including leaves, germinating seeds and seedlings, indicative of high energy demands in these tissues. Interestingly, stage-specific induction of

PYRP2 in dry seeds and

RIBF1 during silique maturation suggest that riboflavin and FAD supply is fine-tuned by a regulatory checkpoint upon major developmental transitions sustaining reproduction. Notably, FMN/FHY, potentially acting as the key enzymatic hub converting riboflavin to FMN, the active cofactor precursor of FAD, showed consistently low expression across all developmental stages and organs, with a marked upregulation observed only in senescent leaves. This upregulation likely reflects an increased cytosolic demand for FMN and FAD during leaf senescence, where an extensive oxidative stress and altered redox homeostasis require enhanced availability of flavin cofactors to support ROS-detoxifying enzymes.

3.3. Response of Riboflavin Metabolism Genes Under Under Osmotic and Salt Stress

Stress conditions modify energy metabolism in plants relying on flavin cofactors availability that play crucial roles in oxidative stress responses and plant adaptation [

21]. We therefore investigated the response of riboflavin biosynthesis pathway components to osmotic and salt stress conditions that are tightly linked to redox balance and metabolic adaptation. Plant eFP Browser integrates large-scale transcriptomic data from RNA-seq and microarrays, enabling to visualize gene expression across developmental stages, tissues and stress responses [

9]. Relative gene expression expressed as log₂ fold change was analyzed upon osmotic and salt treatments at four time points, namely 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours (

Figure 1D and

Supplementary Table S3). Strikingly, under both stresses a similar overall expression pattern was observed. Under osmotic stress, a distinct transcriptional reprogramming of the riboflavin metabolism pathway was evident. Most upstream biosynthetic genes encoding enzymes responsible for riboflavin synthesis, including

RIBA1,

RIBA3,

PYRD,

PYRR,

COS1/LS, and

RS, were consistently downregulated across all time points (

Figure 1D). This transcriptional response is indicative of a general suppression of riboflavin

de novo biosynthesis during osmotic stress at 24 hours. In addition, both

RIBA2 and

FHY/PYRP1 were upregulated at 24 and 12 hours, respectively. Based on the expression profile, the genes involved in flavin metabolism were categorized in two groups. The first group of

NUDX23 and

FADS1 were constantly repressed. On the contrary,

PYRP2 and

FMN/FHY showed a significant induction (

Figure 1D). Nevertheless,

RIBF1 and

RIBF2 displayed minor expressions changes. This transcriptional pattern, characterized by FMN/FHY and FHY/PYRP1 induction accompanied by NUDX23 and FADS1 downregulation, suggests a potential compensatory mechanism that enhances flavin homeostasis among riboflavin and FMN in chloroplast and cytosol under osmotic stress.

In Arabidopsis seedlings subjected to salt stress showed an overall similar expression profile, although the transcriptional responses were generally more moderate than these observed under osmotic stress conditions (

Figure 1D). In particular,

RIBA1,

RIBA3, and

RS riboflavin biosynthetic genes were clearly repressed, while

PYRD,

PYRR, and

COS1/LS exhibited minor changes. In contrast, only

RIBA2 among the initial biosynthetic genes, was induced. The downstream genes

PYRP2 and

FMN/FHY were again upregulated, albeit to a lesser extent than under osmotic stress conditions, suggesting that salinity partially affects flavin metabolism. Notably,

FHY/PYRP1 was downregulated after 24 hours, mirroring the response observed under osmotic stress.

Taken together, these results indicate that specific isoforms within the riboflavin pathway respond to osmotic and salt stress, likely reflecting specialized roles in cellular adaptation and metabolic reprogramming. In particular, the FMN/FHY gene encoding an enzyme responsible for riboflavin conversion into FMN is activated under stress conditions, potentially to support an increased demand for flavin-dependent oxidoreductases in cytosol.

3.4. Cis-Element Analysis of Riboflavin Pathway Gene Promoters

These observations about the spatiotemporal transcriptional profile and stress-related responses were further confirmed by analyzing the

cis-regulatory elements that determine transcriptional regulation of riboflavin biosynthesis genes (

Figure 1E and and

Supplementary Table S4). These

cis elements were grouped into the categories: “Light response,” “Developmental regulation,” “Stress response,” “Developmental/Stress response,” and “Hormone/Stress response”. Remarkably, several hormone-responsive elements, particularly those associated with ABA and salicylic acid, were identified, suggesting a hormonal control of gene expression under stress conditions. ABRE and G-box

cis-regulatory elements, which mediate ABA response [

23] and as-1 [

24], which is an oxidative stress-responsive element activated by salicylic acid, were highly abundant. Interestingly, ABA activates

PYRD,

PYRP2,

COS1/LS and

RS transcription, suggesting a significant role of ABA in flavin metabolism [

25]. In addition, multiple stress-responsive elements such as DRE1 (dehydration-responsive element) [

26], were highly enriched in

RIBA2 and

FMN/FHY promoters, further supporting their role in stress adaptation in consistency with their expression response under abiotic conditions (

Figure 1E). Promoters of

PYRP2 and

FMN/FHY genes harbored very few elements related to developmental regulation, consistent with an almost ubiquitous expression across developmental stages and tissues, as previously shown by TraVA expression analysis (

Figure 1A).

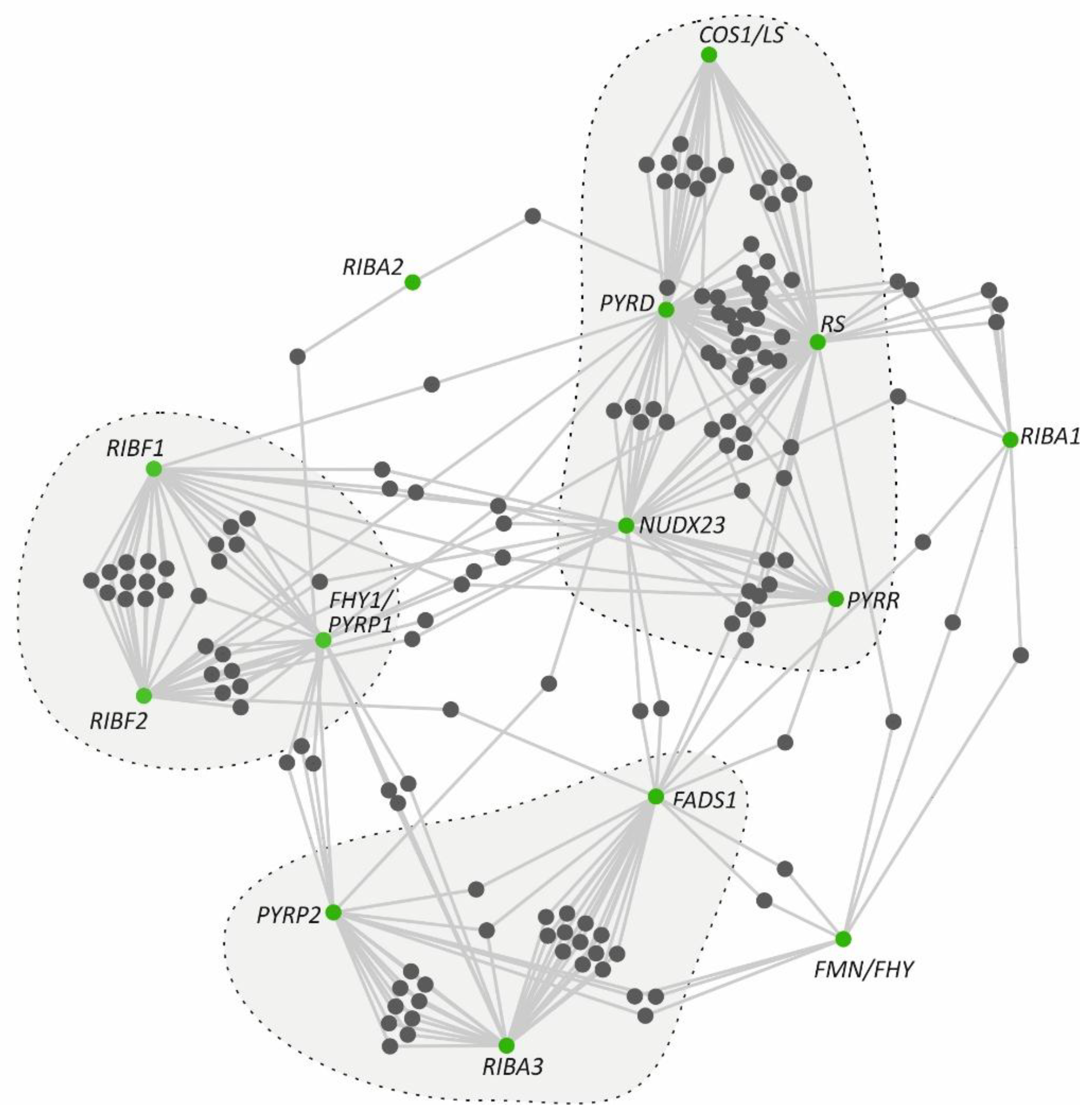

3.5. Co-Expression Hubs of Riboflavin Metabolism Pathway Genes

Gene co-expression networks enable to investigate the expression pattern among multiple gene sets under varying conditions. These networks represent the degree of correlation among gene expression profiles within biological samples originating from distinct tissues, developmental stages and responses to environmental stress conditions [

27]. To complement the promoter-level regulatory insights, we next investigated whether genes of riboflavin metabolism pathway group in co-expression hubs using the ATTED-II database [

28] (

Figure 2 and and

Supplementary Table S5). Interestingly, the initial steps of the pathway driven by

RIBA1 and

RIBA2 did not exhibit any strong co-expression pattern. Nevertheless,

RIBA3,

PYRP2 and

FADS1 formed a minor co-expression module, whereas

FMN/FHY co-expressed with only a limited number of genes, including

RIBA1, FADS1 and

PYRP2. Likewise,

COS1/LS,

PYRD,

RS and

NUDX23 form a tighter cluster, similarly as the cluster of

RIBF1,

RIBF2 and

FHY1/PYRP1. Furthermore,

NUDX23 seems to serve as a link among all clusters, through its co-expression with multiple genes. Together, these findings support a sub-functionalization model in which flavin metabolism is finely regulated in response to developmental cues and environmental signals, consistent with the distinct expression profiles observed across developmental stages, tissues, and abiotic stress conditions.

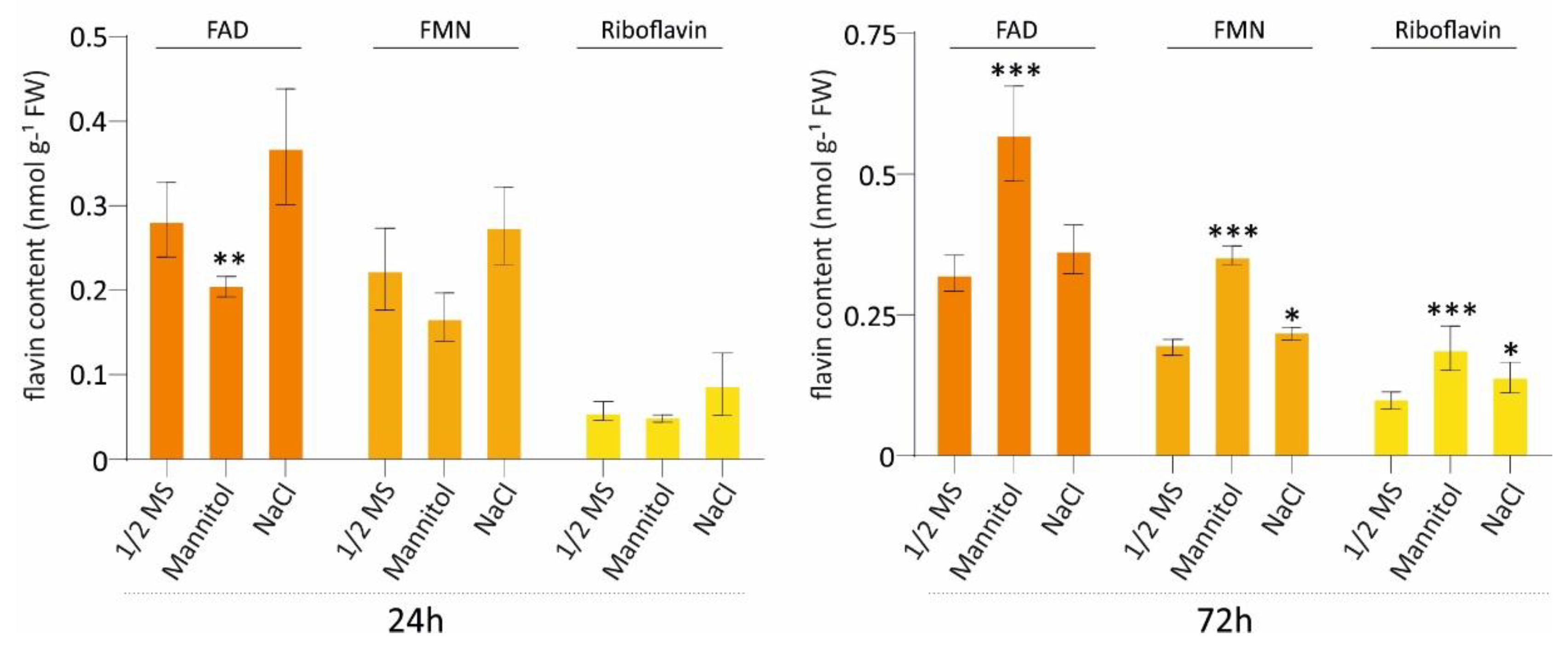

3.6. Flavin Dynamics Under Osmotic and Salt Stress Conditions

Based on the transcriptomic differences in riboflavin biosynthesis, we examined flavin levels (FAD, FMN, and riboflavin) following exposure to osmotic stress (mannitol) and salt stress (NaCl) at two time points, 24 h and 72 h (

Figure 3 and

Supplementary Figure S3). At 24 h, FAD levels decreased under osmotic stress, while a slight, non-significant increase was detected in NaCl-treated plants. By 72 h, these responses were more evident. Under osmotic stress, FAD strongly accumulated, showing a significant increase, while NaCl treatment caused a moderate elevation. FMN also increased under mannitol but to a lesser extent, under salt stress. Riboflavin levels increased in both stress conditions at 72 h, with mannitol-treated samples showing the strongest accumulation profile. Total flavin levels increased exclusively after 72 hours under both stress conditions, while no significant changes observed at 24 hours (

Supplementary Figure S3). Overall, these results show that both osmotic and salt stress affect flavin metabolism, with the most profound differences observed after prolonged stress exposure (72 h).

In Arabidopsis,

AtDREB2G, a member of

DREB-family transcription factors, identified as a positive regulator of flavin biosynthesis under cold stress and abscisic acid (ABA) treatment [

25]. In agreement with our results, exposure to stress conditions such as low temperature or ABA application increased riboflavin, FMN and FAD levels in wild-type Arabidopsis leaves, whereas this response was significantly diminished in

dreb2g mutants [

25]. In this context, cold and ABA induce flavin accumulation via AtDREB2G-mediated transcriptional control. Similarly, salt-treated cotton plants showed increased levels of FMN and FAD in leaves [

29]. Furthermore, continuous light, a high oxidative stress condition, has been shown to increase riboflavin and FAD levels, but not FMN, in Arabidopsis. This increase was accompanied by induction of several riboflavin-metabolism genes, including

FADS,

RIBF1,

RIBF2,

FMN/FHY,

COS1/LS, and

RIBA1 [

19].

Our results reveal a general downregulation of the core riboflavin-biosynthetic genes after 24 hours of osmotic and salt stress, albeit the effect was more pronounced under osmotic stress. However, the FMN/FHY gene, encoding the enzyme which regulates the cytosolic balance between riboflavin and FMN, as well as the FHY1/PYRP encoding the enzyme that reconverts FMN to riboflavin in chloroplasts were both upregulated under osmotic stress conditions. When we analyzed the flavins after 24 hours of stress, we detected a decrease in the pathway’s final product, FMN, only under mannitol stress, where we also observed the strongest expression changes. However, a clear increase in riboflavin, FMN, and FAD under both stress conditions was evident after 72 hours, consistent with previous reports.

Flavin homeostasis under abiotic stress appears to be highly complex. Stress may increase cellular demand for flavins and simultaneously induce enzymes involved in flavin metabolism. In addition, subcellular redistribution of metabolites may occur. For instance, FAD levels may decrease in specific organelles (mitochondria or plastids) due to degradation, while the pool of cytosolic flavins remains constantly buffered. These profiles could also be affected by feedback inhibition mechanisms. In prokaryotes, FMN biosynthesis is controlled by multiple regulatory mechanisms that vary among species. These mechanisms involve riboflavin kinase inhibition by riboflavin itself, redox-dependent modulation of the substrate, or transient subunit assemblies that influence catalysis [30-32]. In humans, reaction products (FMN and ADP) can inhibit riboflavin kinase activity, preventing excessive FAD production and limiting FMN conversion to FAD [

32]. Additionally, because flavin-dependent proteins are prone to oxidative damage and degradation under stress conditions, their flavin cofactors could be rapidly released and damaged or catabolized [

33]. Cells may also actively preserve flavin pools to sustain essential redox reactions, while simultaneously they upregulate components of the flavin-biosynthetic machinery at the enzymatic level. In our case, although a direct link between transcriptional regulation and these regulatory processes is challenging, we observed induction of

FMN/FHY and

PYRP1 24 hours after stress under both osmotic and salt stress, while most genes were downregulated, which may reflect a compensatory response to regulate the abundance of enzymes involved in flavin metabolism and maintain flavin homeostasis during abiotic stress.

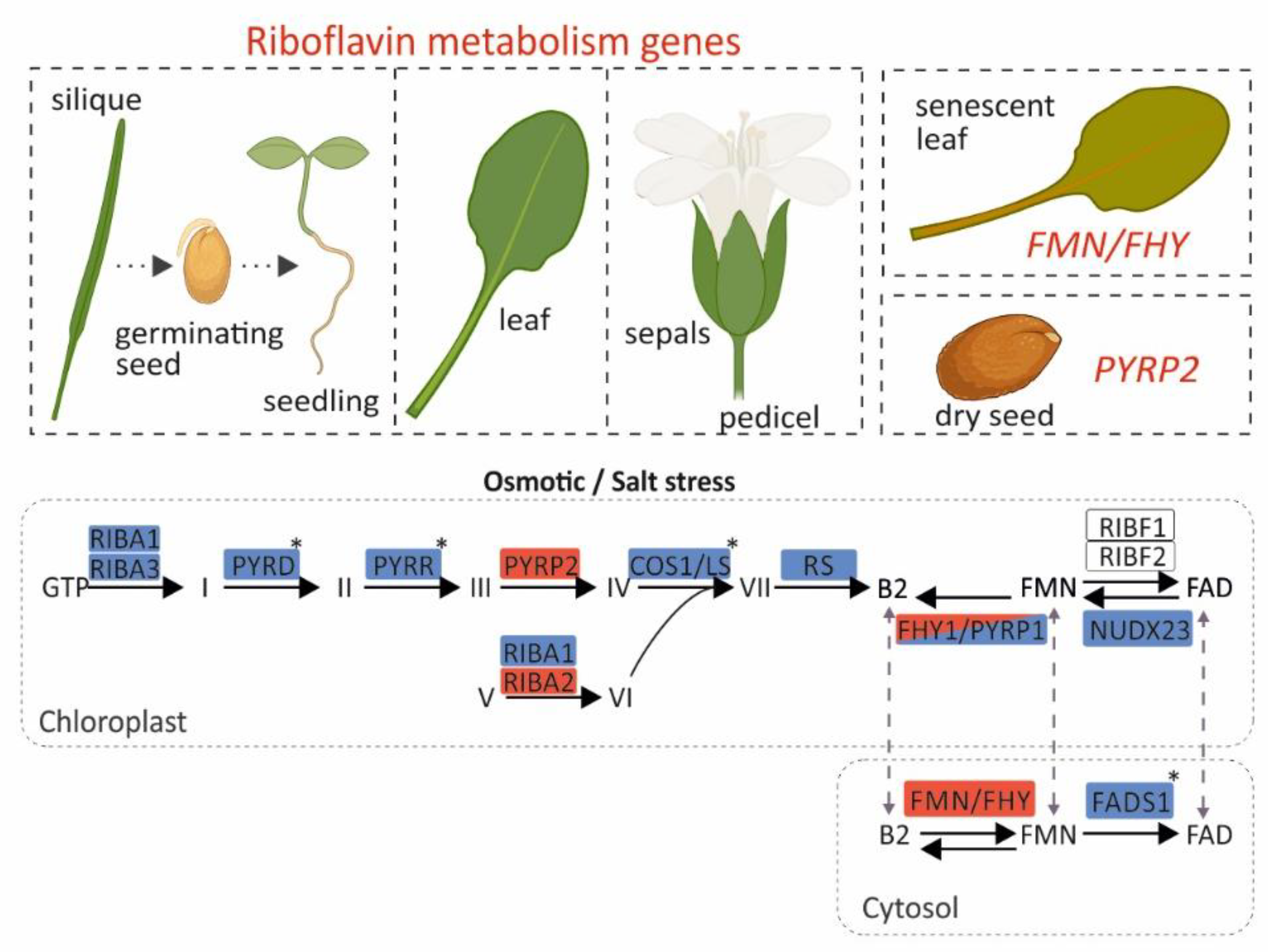

4. Conclusions

Our results reveal that mostly all genes are highly expressed in pedicel, sepals, leaves, germinating seeds and seedlings (

Figure 4). This is consistent with an elevated metabolic demand for flavins to sustain photosynthesis and development in these tissues, where numerous flavoproteins participate in redox reactions and energy metabolism. Moreover,

RIBA1,

RIBA3,

PYRD,

PYRR,

COS1/LS and

RS that participate in riboflavin biosynthesis, were transcriptionally repressed at 24 hours under osmotic stress conditions. This transcriptional response potentially reduces the accumulation of intermediate compounds that could otherwise be detrimental to plastids under stress conditions. On the contrary, an increase in the expression of

PYRP2 and

RIBA2 is observed, which cannot be justified based on the trends of most genes within the pathway, but could instead be attributed to additional moonlighting functions [

34]. Such cases have been reported, where enzymes of the pathway participate in additional roles beyond riboflavin metabolism. A characteristic example is NUDX23, which, apart from its FAD pyrophosphohydrolase activity—hydrolyzing FAD to FMN—also participates in the post-translational regulation of PSY (phytoene synthase) and GGPPS (geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase) for carotenoid biosynthesis through direct interaction with PSY and GGPPS [

35]. For flavin metabolism,

FHY/PYRP1 and

FMN/FHY were upregulated under osmotic stress,

FADS1 and

NUDX23 were downregulated, and

RIBF1/2 genes showed a constant expression pattern (

Figure 4). Flavin measurements following osmotic and salt stress showed alterations, which were pronounced after 72 hours of under prolonged stress, and this likely explains the increased expression of

FHY/PYRP1 and

FMN/FHY1. This dynamic response seems to regulate FMN homeostasis in the chloroplast and cytosol. This reconfiguration of expression reveals an essential role of riboflavin and FAD in flavoprotein-mediated detoxification and signaling. Meanwhile, it also highlights FMN as a crucial intermediate that preserves a balanced riboflavin/FAD ratio in response to cellular demand. This stress-induced metabolic reprogramming is further supported by promoter analysis, which revealed strong enrichment of

cis-regulatory elements associated with abiotic stress responsiveness. Co-expression network analysis identified a distinct cluster composed of core riboflavin pathway genes, including

PYRR,

PYRD, and

RS. Interestingly,

RIBA1/2/3,

FMN/FHY, and

FADS1 that encode the initial and terminal enzymes of the pathway, share only a limited number of co-expression partners, suggesting a modular regulatory strategy and potentially distinct functional roles. Within this architecture,

FMN/FHY emerges as a central node. FMN/FHY catalyzes the conversion of riboflavin into FMN, the direct precursor required for FAD synthesis. It exhibits a unique expression pattern, which is generally low but stable, while becoming highly stress-responsive and strongly induced in senescent leaves.

Altogether, these findings outline a coordinated transcriptional and regulatory program in the riboflavin pathway that enables plants to maintain flavin homeostasis under stress. Understanding this regulatory network could provide valuable opportunities for genetic engineering of flavin biosynthesis in plants, with promising applications in crop biofortification, stress resilience, and metabolic engineering.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1,.

Supplementary Figure S1: Scatterplot illustrating the relationship between iBAQ (intensity-Based Absolute Quantification) and TPM (Transcripts Per Million) values for genes of the flavin biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana across various tissue groups (Mergner et al., 2020). Plot was generated using the ATHENA tool. “Leaf” and “Seed” tissue groups are indicated.

Supplementary Figure S2: Heatmap clustering of proteomics data, with correlations estimated using the Pearson correlation coefficient applied to iBAQ values. Heatmap was generated using the ATHENA tool.

Supplementary Figure S3. Total flavin content in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings under osmotic and salt stress at 24 h and 72 h. Quantification of FAD, FMN, and riboflavin in seedlings grown on ½ MS medium (control), 200 mM mannitol (osmotic stress), or 100 mM NaCl (salt stress) for 24 h (left panel) or 72 h (right panel). Flavin levels are expressed as nmol g⁻¹ fresh weight (FW). Bars represent means ± SD (n = 4). Statistical significance relative to the ½ MS control was determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test (p < 0.1 = *, p < 0.001 = ***).

Supplementary Table S1. List of experimentally characterized genes encoding enzymes involved in the riboflavin metabolic pathway in

Arabidopsis thaliana. Supplementary Table S2. Absolute read counts of the riboflavin metabolic pathway genes across plant tissues determined by RNA-seq and retrieved by the TraVADB database.

Supplementary Table S3. Expression profile of the riboflavin metabolism pathway genes in response to abiotic stress conditions.

Supplementary Table S4. Identified cis-regulatory elements within the promoter regions of riboflavin metabolism pathway genes.

Supplementary Table S5. Data retrieved from ATTED-II used to construct the co-expression network.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D. and S.R.; data acquisition and analysis, G.D., D.T., P.M. and E.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D. and S.R.; funding acquisition and supervision, G.D.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (H.F.R.I.) under the “2nd Call for H.F.R.I. Research Projects to support Faculty Members & Researchers” (Project Number: 02457).

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Prof. Efstathios Panagou (Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, Agricultural University of Athens) for providing access to the HPLC facility.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

ATTED-II Arabidopsis thaliana trans-factor and cis-element prediction database-II

COS1/LS coi1 suppressor1 / Lumazine synthase

FAD Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide

FMN` Flavin Mononucleotide

FADS1 FAD synhtetase

FMN/FHY FMN kinase/FMN hydrolase

FHY1 FMN hydrolase 1

iBAQ Intensity-Based Absolute Quantification

NUDX23 Nudix Hydrolase 23

PYRD Pyrimidine deaminase

PYRP Pyrimidine phosphatase

PYRR Pyrimidine reductase

RIBA Riboflavin biosynthesis protein

RS Riboflavin Synthase

TMM Trimmed Mean of M-values

TPM Transcripts Per Million

TraVAdb Trancriptome Variation Analysis Database

References

- Eggers, R.; Jammer, A.; Jha, S.; Kerschbaumer, B.; Lahham, M.; Strandback, E.; Toplak, M.; Wallner, S.; Winkler, A.; Macheroux, P. The Scope of Flavin-Dependent Reactions and Processes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 2021, 189, 112822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.G.; Croft, M.T.; Moulin, M.; Webb, M.E. Plants Need Their Vitamins Too. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007, 10, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Saand, M.A.; Huang, L.; Abdelaal, W.B.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y. Applications of Multi-Omics Technologies for Crop Improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerdes, S.; Lerma-Ortiz, C.; Frelin, O.; Seaver, S.; Henry, C.S.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Hanson, A.D. Plant B Vitamin Pathways and Their Compartmentation: A Guide for the Perplexed. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 5379–5395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Matsuura, Y.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological Systems Database as a Model of the Real World. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D672–D677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepikova, A.V.; Kasianov, A.S.; Gerasimov, E.S.; Logacheva, M.D.; Penin, A.A. A High Resolution Map of the Arabidopsis thaliana Developmental Transcriptome Based on RNA-Seq Profiling. Plant J. 2016, 88, 1058–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergner, J.; Frejno, M.; List, M.; Papacek, M.; Chen, X.; Chaudhary, A.; Samaras, P.; Richter, S.; Shikata, H.; Messerer, M.; Lang, D. Mass-Spectrometry-Based Draft of the Arabidopsis Proteome. Nature 2020, 579, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Dehais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE: A Database of Plant cis-Acting Regulatory Elements and a Portal to Tools for In Silico Analysis of Promoter Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waese, J.; Fan, J.; Pasha, A.; Yu, H.; Fucile, G.; Shi, R.; Cumming, M.; Kelley, L.A.; Sternberg, M.J.; Krishnakumar, V.; et al. ePlant: Visualizing and Exploring Multiple Levels of Data for Hypothesis Generation in Plant Biology. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 1806–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “One for All, All for One” Bioinformatics Platform for Biological Big-Data Mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiltunen, H.M.; Illarionov, B.; Hedtke, B.; Fischer, M.; Grimm, B. Arabidopsis RIBA Proteins: Two out of Three Isoforms Have Lost Their Bifunctional Activity in Riboflavin Biosynthesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 14086–14105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasnain, G.; Frelin, O.; Roje, S.; Ellens, K.W.; Ali, K.; Guan, J.C.; Garrett, T.J.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Gregory, J.F., III; McCarty, D.R.; et al. Identification and Characterization of the Missing Pyrimidine Reductase in the Plant Riboflavin Biosynthesis Pathway. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sa, N.; Rawat, R.; Thornburg, C.; Walker, K.D.; Roje, S. Identification and Characterization of the Missing Phosphatase on the Riboflavin Biosynthesis Pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2016, 88, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Ren, D.; Hu, J.; Jiang, H.; Chen, P.; Zeng, D.; Qian, Q.; Guo, L. WHITE AND LESION-MIMIC LEAF1, Encoding a Lumazine Synthase, Affects Reactive Oxygen Species Balance and Chloroplast Development in Rice. Plant J. 2021, 108, 1690–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, F.J.; Roje, S. An FMN Hydrolase Is Fused to a Riboflavin Kinase Homolog in Plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 38337–38345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, R.; Sandoval, F.J.; Wei, Z.; Winkler, R.; Roje, S. An FMN Hydrolase of the Haloacid Dehalogenase Superfamily Is Active in Plant Chloroplasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 42091–42098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoval, F.J.; Zhang, Y.; Roje, S. Flavin Nucleotide Metabolism in Plants: Monofunctional Enzymes Synthesize FAD in Plastids. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 30890–30900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.H.; Roje, S. A Higher Plant FAD Synthetase Is Fused to an Inactivated FAD Pyrophosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruta, T.; Yoshimoto, T.; Ito, D.; Ogawa, T.; Tamoi, M.; Yoshimura, K.; Shigeoka, S. An Arabidopsis FAD Pyrophosphohydrolase, AtNUDX23, Is Involved in Flavin Homeostasis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, P.A.; Zhao, S.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, Y.B.; Yang, J.; Li, C.H.; Kim, S.J.; Arasu, M.V.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Park, S.U. Riboflavin Accumulation and Molecular Characterization of cDNAs Encoding Riboflavin Biosynthesis Enzymes in Different Organs of Lycium chinense. Molecules 2014, 19, 17141–17153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiadkong, K.; Fauzia, A.N.; Yamaguchi, N.; Ueda, A. Exogenous Riboflavin (Vitamin B2) Application Enhances Salinity Tolerance through the Activation of Its Biosynthesis in Rice Seedlings under Salinity Stress. Plant Sci. 2024, 339, 111929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Binda, C.; Fraaije, M.W.; Mattevi, A. The Multipurpose Family of Flavoprotein Oxidases. In The Enzymes; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 47, pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Q.; Ho, T.H. Functional Dissection of an Abscisic Acid (ABA)-Inducible Gene Reveals Two Independent ABA-Responsive Complexes Each Containing a G-Box and a Novel Cis-Acting Element. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Garretón, V.; Carpinelli, J.; Jordana, X.; Holuigue, L. The as-1 Promoter Element Is an Oxidative Stress-Responsive Element and Salicylic Acid Activates It via Oxidative Species. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namba, J.; Harada, M.; Shibata, R.; Toda, Y.; Maruta, T.; Ishikawa, T.; Shigeoka, S.; Yoshimura, K.; Ogawa, T. AtDREB2G Regulates Riboflavin Biosynthesis in Response to Low-Temperature Stress and Abscisic Acid Treatment in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci. 2024, 347, 112196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Wu, W.; Abrams, S.R.; Cutler, A.J. The Relationship of Drought-Related Gene Expression in Arabidopsis thaliana to Hormonal and Environmental Factors. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 2991–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zogopoulos, V.L.; Saxami, G.; Malatras, A.; Angelopoulou, A.; Jen, C.H.; Duddy, W.J.; Daras, G.; Hatzopoulos, P.; Westhead, D.R.; Michalopoulos, I. Arabidopsis Coexpression Tool: A Tool for Gene Coexpression Analysis in Arabidopsis thaliana. iScience 2021, 24, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obayashi, T.; Hibara, H.; Kagaya, Y.; Aoki, Y.; Kinoshita, K. ATTED-II v11: A Plant Gene Coexpression Database Using a Sample-Balancing Technique by Subagging of Principal Components. Plant Cell Physiol. 2022, 63, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Lu, X.; Tao, Y.; Guo, H.; Min, W. Comparative Ionomics and Metabolic Responses and Adaptive Strategies of Cotton to Salt and Alkali Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 871387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastián, M.; Velázquez-Campoy, A.; Medina, M. The RFK Catalytic Cycle of the Pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae Shows Species-Specific Features in Prokaryotic FMN Synthesis. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2018, 33, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastián, M.; Arilla-Luna, S.; Bellalou, J.; Yruela, I.; Medina, M. The Biosynthesis of Flavin Cofactors in Listeria monocytogenes. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 2762–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoz-Carbonell, E.; Rivero, M.; Polo, V.; Velázquez-Campoy, A.; Medina, M. Human Riboflavin Kinase: Species-Specific Traits in the Biosynthesis of the FMN Cofactor. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 10871–10886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, A.D.; Henry, C.S.; Fiehn, O.; de Crécy-Lagard, V. Metabolite damage and metabolite damage control in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2016, 67, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, T.B. B Vitamins: An Update on Their Importance for Plant Homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2024, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.; Cao, H.; O’Hanna, F.J.; Zhou, X.; Lui, A.; Wrightstone, E.; Fish, T.; Yang, Y.; Thannhauser, T.; Cheng, K.; Dudavera, N.; Li, L. Nudix Hydrolase 23 Post-Translationally Regulates Carotenoid Biosynthesis in Plants. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 1868–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).