1. Introduction

While individual health can be seen as a combination of health literacy and health beliefs [

1], recently, there has been increased interest in social and psychopathological factors influencing health behaviors and their decline during pandemics of contagious diseases [

2]. Social determinants of health are nonmedical factors that include individual traits like education, income, and health beliefs, as well as social and physical environments such as families, schools, workplaces, neighborhoods, social and biological factors, and the political-economic structure of society [

3]. Health behaviors refer to the ways in which people influence their own health, either positively or negatively. These actions can be intentional or accidental and may either improve or harm the well-being of the individual or others. In health promotion and prevention, people are active decision-makers when it comes to health prevention and control [

4]. According to the Health Belief Model, people are more likely to engage in a health behavior if they believe they are susceptible to the condition, if they perceive it as potentially harmful, and if they believe there are benefits to the health behavior [

5].

However, when the AIDS pandemic and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic began, in our infectious diseases and psychiatric clinics, we noticed that health literacy was not enough to prevent people from engaging in harmful health behaviors. The ability to read, understand, and act on health information is referred to as functional health literacy [

6]. Inadequate health literacy can lead to various negative outcomes, including worsening health, misunderstandings of medical conditions and treatments, difficulties in recognizing and utilizing preventive services, lower self-rated health, reduced adherence to medical advice, increased hospital visits, and higher healthcare costs [

7]. The current research examines these theories in HIV-serodiscordant couples, defined by the WHO as two people in a stable relationship where one partner is HIV-positive and the other is HIV-negative [

7].

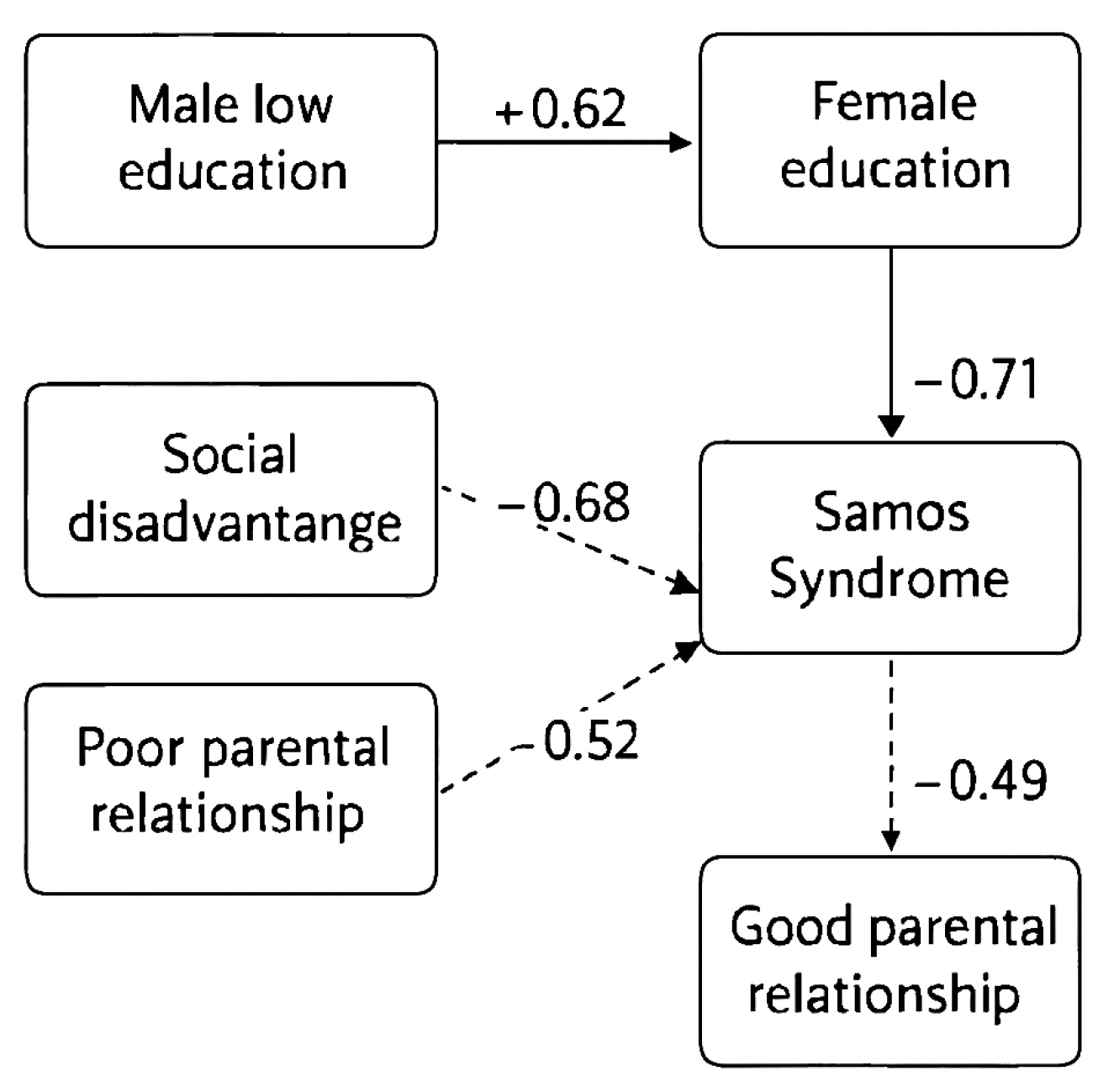

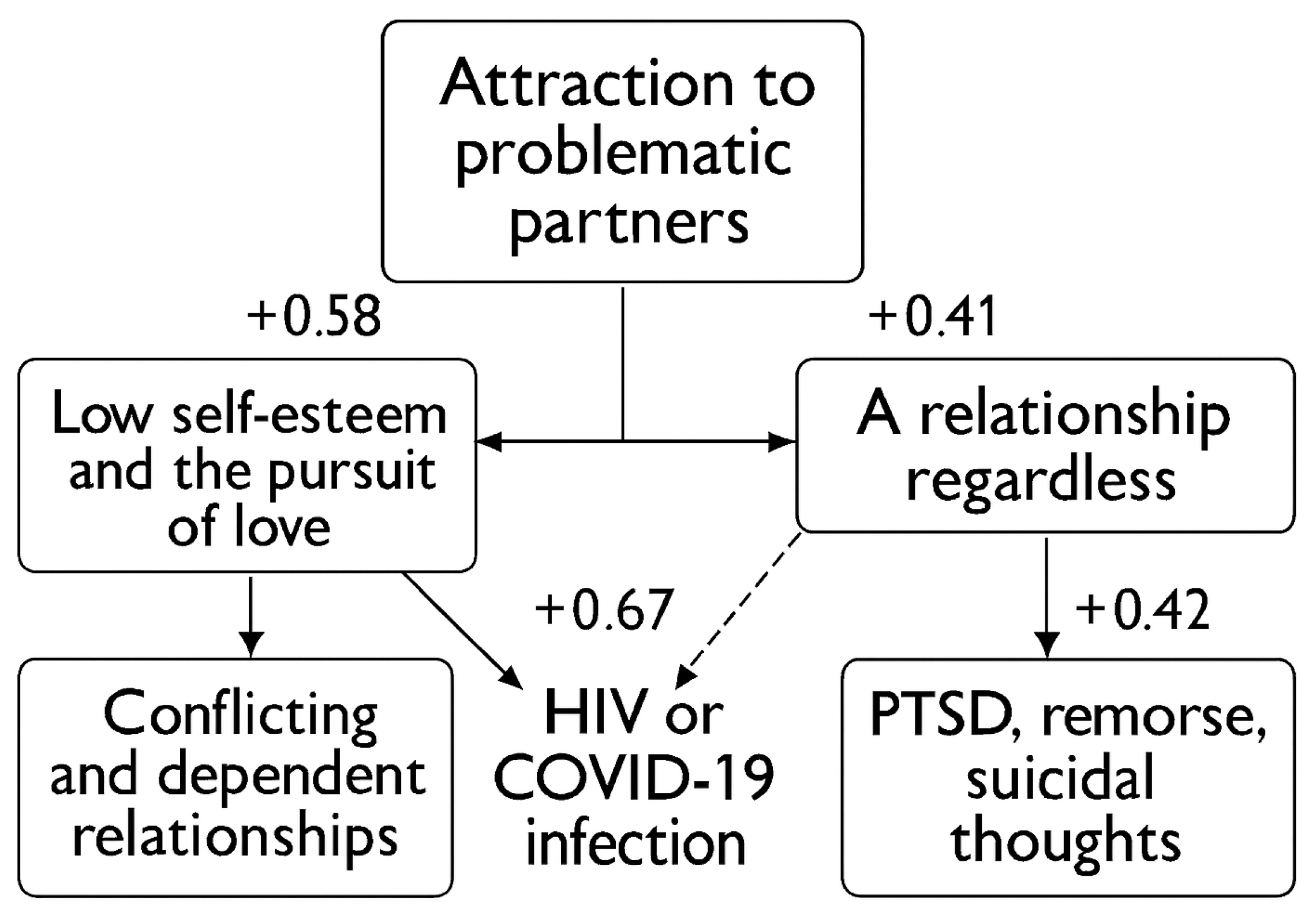

In our previous survey of HIV-serodiscordant heterosexual couples (HSDHC) in infectious disease departments and psychiatric settings completed during study phase 1, we discovered that some psychopathological and psychosocial factors influence the decision in couples to decline HIV prevention (NPC) of sexual transmission [

8]. We called this behavior Samos Syndrome (Sindrome di Samo (It.), El Síndrome de Samo (Sp.), Le Syndrôme de Samo (Fr.) [

8]). In the HSDHC, the female partner who is HIV-negative and has Samos Syndrome makes a mutual decision with her HIV-positive male partner not to use primary prevention to avoid HIV transmission [

9]. We identified the Samos Syndrome roughly 20 years ago [

10]. Women with BPD and Samos Syndrome, specifically DP in HSDHC, intentionally choose not to use infection prevention methods during sexual encounters that pose a risk for HIV, despite having sufficient health literacy about the infection [

11]. We subsequently confirmed that this condition is more common in women with borderline personality disorder and a history of childhood trauma, sexual abuse, and attachment issues [

12]. Samos Syndrome refers to the tendency of individuals—often with a history of childhood violence, abuse, neglect, or trauma—to form romantic, emotionally intimate, and stable sexual relationships with partners who present with significant and debilitating physical, mental, or social conditions [

13]. The behavior in question was called “Samos Syndrome” by the authors, based on the story of Zambaco Pacha, a Turkish doctor who visited many leprosaria worldwide in 1800, including one on the Greek island of Samos [

13]. According to Zambaco Pacha, Samos Island in Greece was the only place where people with leprosy could participate in community activities. They were also allowed to marry members of the local community [

14]. So, it turned out that a woman developed feelings for a man who was highly contagious and suffering from leprosy and bubonic plague [

15]. This episode is reported in Guido Ceronetti’s book,

The Silence of the Body [

15].

HIV progressively weakens the immune system by targeting CD4 T cells and may lead to AIDS if untreated, with AIDS marked by severe immune deficiency and increased susceptibility to infections and cancers; being HIV-positive means the virus is detectable through antibodies, antigens, or viral RNA, though not necessarily symptomatic or indicative of AIDS; furthermore, tansmission occurs via specific infector’s body fluids, blood, semen, vaginal fluids, rectal secretions, and breast milk, from individuals with a detectable viral load, entering the infectee’s bloodstream through mucous membranes, open wounds, or injection [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]

In DSM-5, the criteria for diagnosing BPD include (1) desperate attempts to avoid perceived or actual separation; (2) a passionate and unpredictable pattern of relationships that switch between extremes of idealization and devaluation; (3) identity disturbance: a notable and ongoing unstable perception of self-awareness and self; (4) at least two potentially harmful impulsive behaviors, such as overspending, drug misuse, reckless driving, sexual activity, binge eating, and others; (5) significant emotional hypersensitivity, such as intense episodic dysphoria, anxiety, or irritability, lasting a few hours or rarely more than a few days, leading to affective instability; (6) persistent feelings of emptiness; (7) inappropriate, intense, or hard-to-control anger, such as frequent outbursts, persistent rage, or recurring violent conflicts; and (8) brief paranoid thoughts or acute dissociation [

22].

1.1. Aims

Aim of this study is to examine the intersection of borderline personality disorder (BPD), psychiatric comorbidities, and health risk behaviours in women involved in challenging romantic relationships. It focuses on how relational dynamics may increase vulnerability to HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs), particularly through intentional self-harm and neglect of preventive health measures. Key comorbidities, self-defeating personality disorder, dependent personality disorder, and complex PTSD, were empirically explored within this subgroup. Although BPD was not a selection criterion, it emerged as the predominant diagnosis, confirmed via ICD-10/11 and DSM-5/DSM-5-TR based clinical interviews. This diagnostic outcome shaped the thematic analysis and validated the study’s focus on BPD and its associated behavioural risks. We clarify that while aspects of Samos syndrome have been reported in previous publications, the results presented in the current manuscript are entirely novel. This study represents a condensation and theoretical development of our earlier work, as cited in the references, but the methods, conclusions, and integrative framework are presented here for the first time. The manuscript builds upon prior findings to offer a unified analysis and original interpretation that has not been published elsewhere. We have revised the relevant statement to reflect this distinction more clearly.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Diagnostic framework

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replic Childhood experiences of emotional neglect, physical or sexual abuse, and invalidating caregiving environments are consistently identified as key developmental precursors to borderline personality disorder (BPD). These relational traumas often disrupt attachment formation and emotional development, leading to enduring difficulties in affect regulation and interpersonal functioning. The biosocial model of BPD suggests that individuals with heightened emotional sensitivity, when raised in chronically invalidating contexts, are particularly vulnerable to developing the disorder. Empirical research supports this framework, showing strong associations between early maltreatment and the emergence of core BPD features, including unstable relationships, identity disturbance, and impulsivity [

23,

24,

25]. Behavioral traits indicative of borderline personality disorder (BPD) are defined according to DSM-5 and DSM-5-TR criteria, which describe a pervasive pattern of instability in relationships, self-image, affect, and impulsivity. A diagnosis requires five or more of nine symptoms, including abandonment fears, unstable relationships, identity disturbance, impulsivity, self-harm, affective instability, chronic emptiness, intense anger, and transient paranoia or dissociation [

26,

27]. Participants were assessed using ICD-10 and ICD-11 diagnostic categories (World Health Organization, 1992; 2019), which reflect the standards used in our clinical setting and facilitate international comparison. [

28,

29]. While the ICD framework guided formal diagnostic classification, we also used DSM-5 criteria for Borderline Personality Disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) to shape the conceptual framework of the study [

30]. This dual-system approach was necessary because certain features central to BPD, such as affective instability, identity disturbance, and interpersonal dysfunction, are more clearly described in DSM-5 than in ICD-10/11.

2.2. Research Design

We used a convergent parallel mixed-methods design integrating quantitative prevalence data with qualitative insights to examine psychiatric comorbidities, risk behaviours, and health vulnerabilities in women with borderline personality disorder (BPD) in high-risk relational contexts. This simultaneous analysis enhances validity through triangulation and supports both empirical and interpretive outcomes, thereby increasing clinical and public health relevance [

31]. Structured instruments, open-ended survey items, and ethnographic observation were used to generate both measurable trends and contextual insights. NVIVO software supported narrative analysis, while quantitative data were managed in Excel and elaborated using MedCalc. This approach enabled triangulation and enriched interpretation, particularly suited to healthcare and education contexts, to understand both outcomes and underlying processes is essential [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

The study employed a mixed-methods design to triangulate data and generate a layered, reflexive understanding of complex phenomena in mental health practice. Each qualitative method contributes a distinct lens: (1)

narrative analysis explored the storied nature of experience, privileging temporality, identity, and meaning-making; (2)

thematic analysis identified patterns across data using a theory-driven approach informed by DSM-5, ICD-10/11, and psychodynamic models, allowing for structured coding while remaining open to emergent insights; (3)

grounded theory supported theory generation from data, revealing latent processes and mechanisms; and (4)

ethnography situates individual narratives within broader cultural and organisational contexts, particularly when direct interviews were not feasible [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. This hybrid strategy aligns with what Bella Williams describes as

hybrid qualitative analysis, where thematic analysis is enriched by integrating narrative and ethnographic insights to produce a more nuanced and layered interpretation [

44]. Similarly, Creswell suggests that combining qualitative methods can enhance the depth and breadth of inquiry, especially when addressing multifaceted social phenomena [

45]. Integrating qualitative approaches into a mixed-method framework enhances validity through triangulation, provides distinct insights via complementarity, informs coding structures through developmental sequencing (e.g., narrative analysis informing thematic analysis), and situates findings in real-world contexts via contextualisation (e.g., ethnographic data). This aligns with integrative evidence synthesis models that layer qualitative methods to refine theoretical constructs and interventions [

46].

2.3. Data Collection and Survey

This study employed a mixed-methods approach combining structured surveys, psychiatric interviews, and open-ended questions to explore condom use, relationship history, education, and parental attachments among HIV-serodiscordant couples. NVIVO software supported thematic analysis of transcripts, identifying patterns within psychopathological frameworks for BPD. Structured interviews ensured consistency and comparability, while open-ended and unstructured interviews captured nuanced, experiential data. This dual strategy enabled both statistical mapping and interpretive depth, particularly in understanding how early relational trauma and psychoeducational histories influence risk-taking behaviors. The integration of ethnographic observation further enriched contextual insights, aligning with best practices in healthcare and education research [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56]. In Phase 1, structured surveys used standardized, closed-ended questionnaires to assess HIV-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among target HIV-serodiscordant couples, enabling consistent data collection and quantitative analysis. These were followed by structured psychiatric interviews employing validated tools to both explain non-adoption of HIV prevention and generate psychiatric diagnoses, serving diagnostic and explanatory roles within the mixed-methods design. In later phases, unstructured interviews provided open-ended, participant-led narratives that captured lived experiences and emergent themes around HIV prevention, relationships, and mental health, offering contextual depth beyond structured formats.

2.4. Phase 1 (1994-2009)

This phase adopted a cross-sectional quantitative survey with HIV-sero-discordant couples across multiple centres. Phase 1 aimed to investigate the objectives underlying biopsychosocial dynamics in HSDHC, with a focus on individuals diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (BPD). The data collection combined structured surveys and informal interviews to capture both statistical trends and experiential narratives. A total of 175 couples were recruited using purposive sampling across international sites. Interviews explored clinical histories, relational stressors, and mental health profiles. The settings included HIV clinics, genitourinary medicine units, and community psychiatric teams, ensuring ecological validity and a comprehensive lens on the interplay between psychiatric comorbidity and HIV transmission risk.

2.5. Phase 2 (2009–2019)

This phase involved a qualitative, exploratory study with unstructured interviews and narrative analysis, focusing on the phenomenology of Samos Syndrome. Phase 2 (2009–2019) was a qualitative, exploratory study investigating the objectives of relational and psychological experiences in HSDHC, with a focus on the phenomenology of Samos Syndrome—characterized by relational ambivalence, identity fragmentation, and emotional dysregulation. Data collection involved unstructured interviews and narrative analysis, guided by Braun and Clarke’s Thematic Analysis across seven iterative stages. Transcripts were anonymized and analyzed inductively to identify emergent themes reflecting emotional, interpersonal, and diagnostic complexities. The settings mirrored Phase 1, spanning HIV clinics, genitourinary medicine units, and community psychiatric teams, ensuring diverse relational contexts and integrated psychiatric-sexual health perspectives. The participants were the same approached who were in follow-up arms in HIV clinics, hence one member of the 175 HSDHC was identified as Samos, and thus a total of 80 participants.

2.6. Phase 3: (2019-2025)

The design was theory development and synthesis from previous phases, including transcript reviews and final interpretations. Phase 3 (2019–2025) focused on objectives of theory development and synthesis, advancing understanding of relational psychopathology and health vulnerability in HSDHC, particularly those with borderline personality disorder (BPD) and Samos Syndrome. The data collection drew exclusively from previously gathered transcripts, thematic matrices, and analytic memos from Phases 1 and 2. Using abductive reasoning and set-theoretic modeling, we mapped comorbidities across BPD, self-defeating personality disorder (SDPD), dependent personality disorder (DPD), and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). The settings involved academic and analytic environments, with interdisciplinary collaboration across psychiatric and qualitative research teams, maintaining continuity with the multicenter framework established in earlier phases. Set theory and Venn diagrams provided a formalized and visually intuitive framework for modeling theoretical constructs in research, enabling the representation of intersecting psychological, behavioral, and relational domains with conceptual clarity and structural coherence. Applications of Set Theory in Phase 3 were as follows:

Conceptual Mapping: Sets allow researchers to define and compare categories such as diagnostic groups, behavioral traits, or relational dynamics. For example, BPD, DPD, and trauma histories can be treated as sets whose intersections reveal clinically significant patterns.

Comorbidity and Overlap: Using intersections (e.g., BPD∩DPD∩SDPD), researchers can formally represent how multiple conditions or experiences co-occur, offering clarity in understanding complex syndromes or behavioral profiles.

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA): A set-theoretic method that uses Boolean logic to identify necessary and sufficient conditions for outcomes. It’s increasingly used in social sciences to analyze case-based data with configurational complexity.

Narrative Structuring: Sets can be used to organize narrative data into typologies, where each set represents a thematic or diagnostic domain. This supports both idiographic depth and thematic abstraction.

Formal Logic Integration: Set theory enables the use of symbolic logic in qualitative research, enhancing transparency and reproducibility in theory-building [

57].

2.7. Rigour of the Study

The study followed the criteria established by Guba and Lincoln (1984) to ensure transferability, dependability, credibility, and confirmability. The findings were firmly based on the collected data and underwent audits at multiple centers to enhance reliability. Theories and conclusions aligned with the current understanding of psychopathology, using precise terminology and concepts. Researcher bias was mitigated through data triangulation, the sharing of findings, and feedback from subject-matter experts, as well as blogs, media, and colleagues. Dependability was confirmed as independent researchers worldwide identified Samos Syndrome in their studies and discussions. Transferability was achieved by replicating the study in different geographic locations, which consistently produced similar phenomena [

58].

2.8. vResearcher Positionality

The authors acknowledge their positionality as experienced clinicians and researchers, shaping the lens through which this study was conducted. CL brings dual postgraduate training in psychiatry and infectious diseases, offering integrated expertise in mental health and HIV care. MR contributes a strong foundation in population health and service evaluation. Their combined experience in HIV-related research, particularly its psychological and psychiatric dimensions, provides deep insight into both clinical realities and the structural determinants of health. Grounded in a commitment to social justice, equity, and compassionate care, their work seeks to enhance service quality and address systemic barriers to health and behavior.

2.9. Methodology, Theoretical Frameworks, and Theory Construction

The current research adopted a constructivist approach as outlined by Guba and Lincoln (1984), emphasizing the locally constructed nature of reality [

42,

43]. The epistemological framework was transactional, meaning that knowledge was shaped through interactions between researchers and participants, with patient narratives interpreted through the researchers’ subjective lenses. Methodologically, the study employed a hermeneutic and dialectical approach, focusing on the interpretation and reconstruction of social constructs to develop theories that explain observed phenomena [

59,

60].

We adopted an ontological perspective to explore the nature of reality, which is shaped by locally and individually constructed views. The epistemology examined the relationship between the knower (researcher) and the subjects being understood, portraying it as a transactional process. This included collecting patients’ narratives alongside researchers’ subjective interpretations of the phenomenological worlds [

61]. Since the ontology of constructivism is relativism, we identified multiple realities that vary based on social, psychological, and interpersonal factors. Our approach was hermeneutic and dialectical, and social constructions were strengthened through our interactions with the target population. Therefore, our inquiry focused on understanding and reconstructing to develop theories about the observed phenomena [

62].

We primarily used the WHO’s ICD-10/11 but also DSM-5/5TR diagnosis categories. This study employs a Grounded Theory approach, conducting participant observations and semi-structured interviews to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon of interest. Through narrative analysis, themes and sub-themes were identified, which informed the development of conceptual frameworks. The findings contribute to both middle-range theories—providing explanations specific to particular contexts—and grand theories, which offer broader theoretical insights [

63]. We used the Borsboom et al. (2021) theory construction model, where developing a theory involves five stages [

64] (

Table 1).

2.9. Data Analysis

Phase 1 of the study included a cross-sectional anonymous survey of HIV-serodiscordant couples. We asked the couples, ‘With 100% being ‘every time you have a sexual relationship,’ how often do you use condoms for HIV prevention?’. The study was conducted in infectious disease departments and community psychiatric teams. The first author (CL) performed the interviews, which were later verified through multidisciplinary team discussions to confirm and triangulate the diagnostic hypotheses. The statistical analysis employed rigorous methods to ensure the reliability of the observed differences in condom use across sociodemographic groups. Confidence intervals were estimated using the Wilson score method, which offers improved accuracy for binomial proportions, particularly in samples of moderate size. To assess the significance of differences between paired groups, two-proportion z-tests were conducted. All comparisons yielded statistically significant results at the conventional alpha level of 0.05, with p-values consistently below 0.001. To elaborate the findings in Phase 1 we employed path analysis to examine direct and indirect associations among study variables within a theoretically specified causal framework. Standardized beta (β) coefficients were estimated using ordinary least squares regression, implemented in

AMOS (Analysis of Moment Structures). The model assumed linearity, additivity, and absence of measurement error. Model fit was evaluated using conventional indices. This approach enabled quantification of mediating pathways and assessment of hypothesized structural relationships relevant to the study context [

65,

66].

In Phase 2, we carried out a narrative analysis of interviews with HIV-serodiscordant couples (see Appendix). Braun and Clarke’s Thematic Analysis involves seven stages. These stages typically include: (1)

familiarization with the data: diving into the dataset by reading and rereading transcripts while noting initial ideas; (2)

generating initial codes: finding meaningful segments of data and systematically assigning codes; (3)

searching for themes: grouping

related codes into broader themes that reveal patterns in the data; (4)

reviewing themes: refining themes to ensure they align well with the dataset; (5)

defining and naming themes: explaining the core of each theme and its relevance to the research question; (6)

producing the report: writing a structured analysis that connects themes with supporting data; and (7)

reflexivity and interpretation: critically reflecting on the researcher’s role and how it influences the findings [

40,

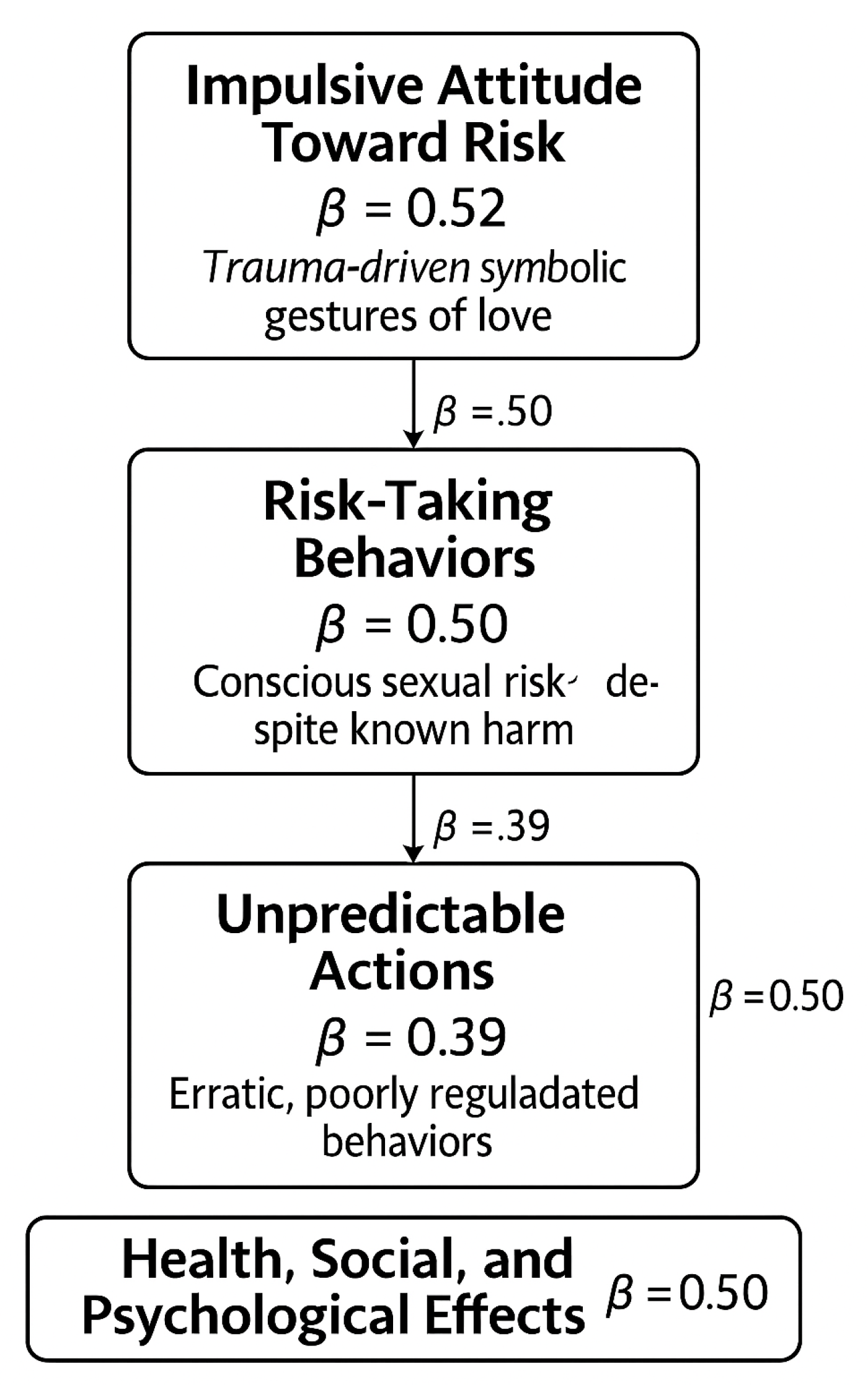

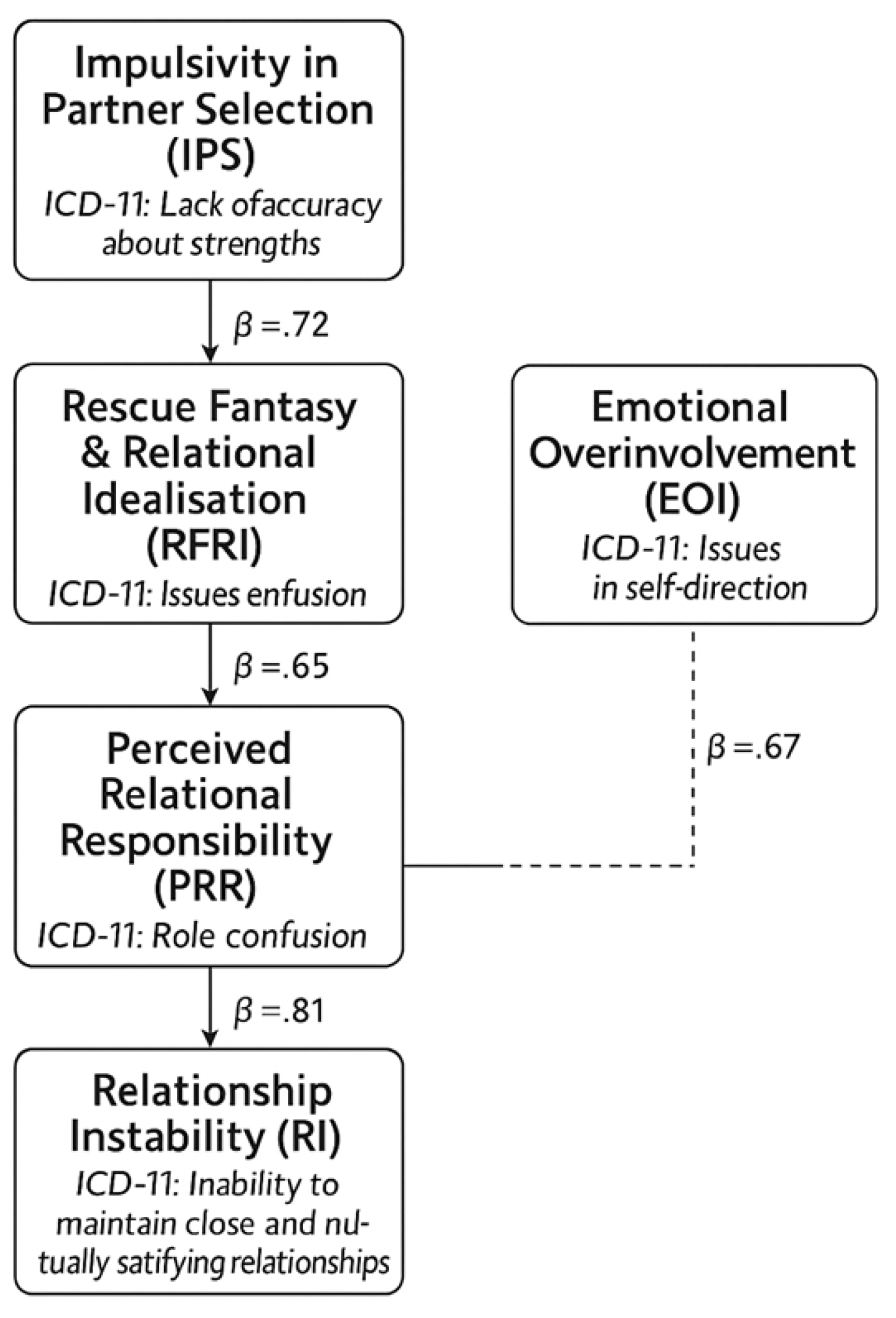

67]. To examine relational trajectories and behavioral outcomes linked to Samos Syndrome, the study used a hybrid analytic strategy combining narrative analysis with path modelling. This integrative approach allowed qualitative depth to be translated into structural relationships, supporting a constructivist and pragmatic epistemology. Narrative constructs, such as educational incongruence, parental relationship quality, and emotional dysregulation, were coded and operationalised into variables within a matrix-based path model. Independent, mediating, and dependent variables were mapped to explore relational plausibility rather than causality. Standardised beta coefficients quantified associations, enabling the identification of mechanisms that shape health risk behaviors and inform clinical and psychosocial interventions [

68,

69,

70,

71,

72].

When direct unstructured interviews were impractical, we adopted a naturalistic ethnographic approach, gathering data through informal, work-based interactions. This method aligns with

symbolic interactionism and

situated learning theory, emphasizing meaning-making through real-world engagement. Drawing on Lazzari’s ethnographic work in medical settings, we collected narratives from individuals exhibiting signs of Samos Syndrome and reflections from their HIV-positive partners. To analyze these accounts, we applied a dual-framework thematic analysis combining

Grounded Theory and

Braun and Clarke’s reflexive approach, allowing for inductive theme development and interpretive depth. We also examined educational and familial histories to identify patterns of trauma, later confirmed through interdisciplinary team discussions across centers [

73,

74,

75,

76,

77].

2.10. Use of Vignettes in Clinical Education

Vignettes are valuable tools in medical education and research, offering realistic yet controlled scenarios that promote ethical reflection, clinical reasoning, and inclusive learning. They support qualitative inquiry and protect patient confidentiality by anonymizing real cases. Used in narrative-driven training, vignettes enhance engagement, critical thinking, and cultural sensitivity. Their structured format allows educators to assess decision-making and diagnostic skills while fostering a deeper understanding of complex clinical situations. Overall, vignettes improve the validity of qualitative data collection and align educational practices with ethical and empirical standards [

78,

79,

80,

81,

82]. Rather than merging transcripts with fictional vignettes directly, we followed a multi-stage interpretive process. Individual narratives from participants with similar clinical profiles were first analysed separately, then synthesized into composite vignettes representing recurring emotional, relational, and behavioural patterns. Drawing on narrative synthesis and interpretive phenomenology, these fictionalised constructs preserved the integrity of lived experience while distilling complex data into coherent forms. Early narrative analysis informed their structure and meaning-making, and thematic analysis of the unified typology revealed cross-cutting patterns. This approach supports methodological pluralism, balancing idiographic depth with thematic abstraction and ensuring epistemic transparency throughout the analytic process [

83,

84,

85].

2.11. Ethical Consideration

The study adhered to rigorous ethical standards, including the Helsinki Declaration, with all data anonymized and collected through confidential interviews and structured assessments conducted by one of the authors (CL). Participants, particularly HIV-serodiscordant couples, were informed of their right to withdraw and provided consent under a clearly defined ethical framework. To protect identity, real cases were synthesized into fictional vignettes that preserved narrative integrity while ensuring confidentiality. Drawing on Hanna Meretoja’s ethical theory of storytelling, the study treated narrative as a morally engaged practice that fosters self-understanding, perspective-taking, and social critique. Open-ended questions explored relational and psychoeducational factors, and thematic analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s six-phase model, with clustering applied only when BPD was confirmed as the primary influence. All data, including transcripts and audio recordings, were securely stored and destroyed post-analysis, ensuring compliance with ethical and methodological best practices.

The study followed the ethical standards set by the relevant institutional and national committees on human experimentation, as outlined in the Helsinki Declaration (World Medical Association, 2013) [

86]. All surveys were anonymized and conducted through confidential interviews via AIDS counseling hotlines, ensuring participant confidentiality and protection [

87]. Additionally, structured interviews were conducted by one of the authors (CL). To protect confidentiality and uphold ethical standards, the narratives in this study were created by synthesizing real cases and typical accounts. Ethical approval was secured from the participating couples and relevant healthcare organizations, and all data were fully anonymized before analysis. The right to withdraw was a condition explicitly communicated to all participants during the consent process to ensure informed participation. All eligible individuals, meeting the study’s inclusion criteria, were required to understand and acknowledge this right as part of the ethical framework underpinning the study.

To protect anonymity, accounts from various individuals were merged into fictional vignettes, maintaining the original meaning while ensuring confidentiality. Storytelling, as defined by Hanna Meretoja in The Ethics of Storytelling (2018), is described as a morally complex interpretive practice that goes beyond sharing experiences to actively shape ethical understanding and social possibilities [

88]. Drawing on narrative hermeneutics, Meretoja identifies six ethical dimensions that support storytelling: fostering the imagination of alternative futures, enabling self-understanding, facilitating nuanced comprehension of others, reflecting transitional spaces between narratives, enhancing perspective-taking, and serving as ethical inquiry [

88]. Meretoja argues that narratives are not ethically neutral but are influenced by historical and cultural contexts, capable of both reinforcing dominant ideologies and encouraging critical change [

88]. This ethical framework emphasizes the relational nature of storytelling and the responsibilities associated with narrative acts, particularly in research, education, and public discourse. By developing a theory in which storytelling affects moral imagination and fosters dialogical engagement, Meretoja views narrative as a space for reflective ethical practice and social critique [

66]. All collected data, including audio recordings and written transcripts, were securely stored and later destroyed after the analysis was completed [

89].

Participants, especially members of HIV-serodiscordant couples, responded to open-ended questions designed to complement a structured psychiatric interview. These questions explored condom use in sexual relationships, previous partnerships, educational background, and parental dynamics, topics previously identified in structured surveys as important factors influencing behavioral patterns and psychoeducational backgrounds (see Appendix; see [

90]).

Meeting transcripts were systematically reviewed to identify key themes and subthemes, following Braun and Clarke’s six-phase approach to thematic analysis [

91]. The process started with familiarization, during which transcripts were carefully read and re-read to ensure a deep engagement with the data. Initial codes were created to identify meaningful patterns, which were then systematically grouped into broader themes and subthemes [

69]. Narratives were analyzed within the established frameworks of BPD, ensuring a structured and rigorous approach to thematic categorization. Thematic clustering was performed only when BPD was thoroughly confirmed as the main factor influencing the observed behaviors and narratives, maintaining validity and coherence in the analysis [

92].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Carlo Lazzari; methodology, Carlo Lazzari and Jon Rees; validation, Carlo Lazzari, Yitka Graham, and Rebecca Owens; formal analysis, Carlo Lazzari; investigation, Carlo Lazzari and Jon Rees; resources, Carlo Lazzari; data curation, Jon Rees; writing—original draft preparation, Carlo Lazzari; writing—review and editing, Yitka Graham and Rebecca Owens; visualization, Jon Rees; supervision, Carlo Lazzari; project administration, Carlo Lazzari; funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.