1. Introduction

Following the introduction of embryo vitrification technology, the “freeze-all” strategy has gained considerable popularity because modern vitrification provides high post-thaw survival and allows separation of stimulation and transfer without compromising outcomes [

1,

2] . From a patient-safety perspective, this strategy is commonly used to prevent ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), especially in high-responding patients [

3,

4,

5].

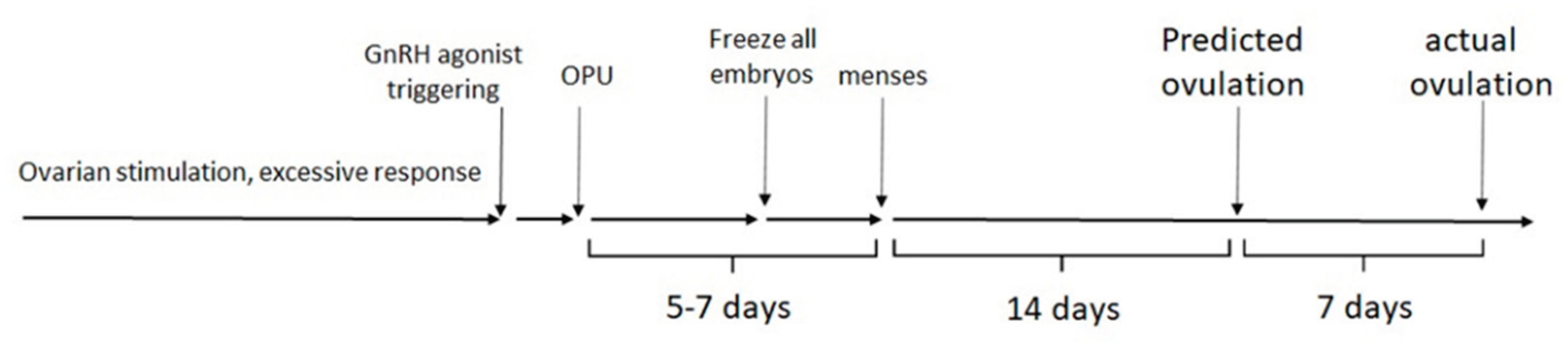

In the classic scenario, a GnRH agonist (GnRH-a) is used to trigger ovulation in an antagonist cycle, and all resulting embryos are vitrified, avoiding a fresh transfer. The subsequent menstrual period typically occurs 5–7 days after oocyte retrieval because of rapid luteolysis, which is a key mechanism by which the risk of OHSS is reduced [

5,

6,

7]. In most cases, however, the patient is eager to proceed with frozen embryo transfer (FET) as soon as clinically feasible.

In routine practice, many patients are understandably eager to proceed with frozen embryo transfer as soon as possible, especially when a freeze-all decision was made for safety rather than elective reasons [

8].

For frozen embryo transfer (FET) cycles, the endometrium must be prepared in advance to synchronize the endometrial “window of implantation” with the developmental stage of the thawed embryo. Two main approaches are used: an artificial (programmed) cycle and a natural (or modified natural) cycle [

9,

10,

11,

12].

In an artificial or programmed cycle, exogenous estrogens are given to stimulate endometrial proliferation, and once ultrasound and/or blood tests confirm an adequate endometrial lining, progestogen is added to open the implantation window so that the embryo can implant [

9,

10,

11]. The key practical advantage is scheduling flexibility: because progesterone can be started on any chosen day once the endometrium is ready, the embryo transfer can be planned to avoid weekends or peaks in workload, which is convenient for both patients and clinics [

9,

10,

11]. In contrast, a natural-cycle FET relies on endogenous estradiol production by the developing follicle, with ovulation occurring spontaneously or being triggered medically in anovulatory women, so this strategy cannot be used in menopausal patients and offers less control over timing.

In recent years, growing clinical and observational data suggest advantages of natural or modified-natural FET cycles over fully programmed cycles, including at least comparable live birth rates and, in several studies, lower pregnancy loss and better obstetric outcomes [

13,

14,

15,

16]. The underlying endocrine rationale is to preserve a functional corpus luteum (CL), which provides not only progesterone but also vasoactive and angiogenic factors that appear important for normal implantation, placentation, and early maternal cardiovascular adaptation [

17,

18,

19].A functional CL can be obtained either after spontaneous ovulation in an ovulatory woman or after induced ovulation in anovulatory patients, so long as the cycle includes follicular development and ovulation rather than pure HRT. Consequently, natural or modified-natural FET protocols are increasingly used even in patients who previously underwent GnRH-agonist trigger and “freeze-all” for OHSS prevention, because once the acute OHSS risk has resolved, a later cycle with ovulation and a functioning CL can be safely supported and synchronized with FET.

Whether to perform FET immediately after a “freeze-all” cycle or to defer it has been studied, and current evidence generally favors not delaying without a specific medical reason [

20,

21,

22]. Several studies in women after failed fresh IVF have shown that postponing FET does not improve reproductive outcomes compared with proceeding in the first available cycle. Furthermore, other reports found that immediate FET was associated with higher ongoing pregnancy and live birth rates than delayed FET, suggesting that routine deferral may actually be disadvantageous in some settings [

20,

21,

22].

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis reported slightly higher live pregnancy and cumulative pregnancy rates in immediate versus postponed FET cycles, although the absolute differences were modest and individual patient factors must still guide decisions. From the patient’s perspective, the wish to conceive as soon as possible after a “freeze-all” cycle is entirely understandable, and in the absence of contraindications such as unresolved OHSS, inadequate endometrial recovery, or significant intercurrent illness, the available data support offering FET at the earliest appropriate opportunity.

Natural-cycle FET requires multiple clinic visits to monitor follicular development, detect a spontaneous LH surge, or decide on optimal hCG trigger timing for ovulation [

9,

23,

24,

25]. To reduce the number of visits, patients typically start with blood tests and ultrasound about two days before the expected ovulation day, based on their prior menstrual cycle patterns [

23,

24,

25].

However, ovulation timing can be unpredictable after a recent stimulation cycle for oocyte retrieval, as residual effects from the ovarian stimulation or the specific ovulatory trigger (such as GnRH agonist) may alter the natural cycle dynamics. Clinics often use ovulation predictor kits at home or sequential hormone measurements (LH, estradiol, progesterone) to refine timing and schedule embryo transfer precisely—typically 6 days after a spontaneous LH surge or 7 days after hCG trigger—while balancing monitoring burden with accuracy [

23,

24,

25].

This study aims to evaluate whether ovarian stimulation combined with GnRH agonist trigger affects recovery of the reproductive axis in the subsequent cycle. GnRH agonist triggering prevents OHSS through rapid luteolysis, resulting in a profoundly disrupted luteal phase compared with a natural one [

5,

6,

7,

26,

27]. This raises the question of whether ovulation might be delayed in the following cycle; if so, clinic visits could be scheduled later to avoid unnecessary monitoring.

2. Methods

The study took place in a private IVF unit in Northern Israel and retrospectively included 100 ovulatory patients undergoing ovarian stimulation with a GnRH antagonist protocol for IVF from January 2023 to August 2024. GnRH agonist trigger (triptorelin 0.2 mg, Ferring, Switzerland) was used for final oocyte maturation to prevent OHSS in the setting of high ovarian response. All embryos were cryopreserved using vitrification technology. This protocol allows precise control over ovarian stimulation, prevents premature LH surge, and reduces OHSS risk while optimizing oocyte yield and embryo quality [

28,

29,

30].

FET was scheduled according to the patient’s natural ovulation cycle. Patients were monitored via vaginal ultrasound and blood tests for estradiol, progesterone, and LH until the leading follicle reached at least 17 mm in diameter [

23,

24,

25]. On the day the follicle met this criterion, patients were instructed to inject 250 µg hCG (Ovitrelle, Merck Germany) to induce ovulation that evening. A second 250 µg hCG injection was administered five days later. On the same day, patients began daily treatment with dydrogesterone (Duphaston, 30 mg, Abbott, USA) for luteal support. FET was performed that day for embryos frozen on day 3 or two days later for blastocyst-stage embryos, in line with established embryo-endometrium synchronization intervals in modified natural-cycle FET [

23,

24,

25,

31]. This protocol aligns with recommended timing standards for modified natural cycle FET, providing controlled ovulation induction and synchronizing embryo transfer precisely after hCG trigger to optimize implantation potential [

23,

24,

25,

31].

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the IRB committee, Elisha Hospital, 0001-24-MDC, on September 1st, 2024.

3. Results

Patients had a mean (± SD) age of 32.5 ± 5.5 years and BMI of 25.1 ± 5.1 kg/m², consistent with typical IVF cohorts in similar settings. Pretreatment cycle length averaged 28.1 ± 1.6 days, so natural ovulation typically occurred on cycle day 14 in unstimulated cycles. Mean oocytes retrieved was 17.3 ± 5.7, consistent with high responders selected for GnRH agonist trigger and freeze-all.

The mean cycle day for the first hCG injection during FET was 18.9 ± 3.2, so ovulation occurred on cycle day 21—seven days later than predicted from pretreatment cycle length (

Figure 1). On that day, serum estradiol, progesterone, and LH levels averaged 898 ± 415 pmol/L, 1.9 ± 1.1 nmol/L, and 15.6 ± 14.3 IU/L, respectively, consistent with late follicular phase before hCG trigger in modified natural cycles [

23,

24,

25,

32,

33,

34].

Notably, eight patients showed no estradiol rise or dominant follicle after 15–28 days of monitoring and were switched to hormonal FET. Forty patients achieved clinical pregnancy; among them, mean first β-hCG was 621 IU/L, estradiol 1048 pmol/L, and progesterone 50.1 nmol/L, with mean birth weight of 3193 g, values comparable to published natural-cycle FET series [

13,

14,

15,

16,

34].

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the effect of ovarian stimulation combined with a single dose of GnRH agonist trigger (triptorelin 0.2 mg in this study) on the immediate subsequent natural cycle has not been previously reported. Our data clearly indicate that this combination inhibits the reproductive axis for several days, causing a delay of approximately one week in ovulation during the next cycle. In some patients, this inhibition may persist for several weeks, as evidenced by the absence of follicular activity and ovulation during follow-up. Triptorelin’s mechanism includes an initial stimulation followed by desensitization of GnRH receptors, suppressing LH and FSH secretion and leading to disrupted ovulation timing after administration. These findings suggest that ovulation monitoring timing in natural FET cycles following GnRH-a trigger may need adjustment to account for this delay [

35,

36].

In the GnRH agonist “long protocol” for ovarian stimulation, daily GnRH-a administration for 1–2 weeks achieves pituitary downregulation, preventing premature ovulation and enabling controlled stimulation with hCG trigger only [

37,

38,

39]. In contrast, the GnRH antagonist protocol used here permits GnRH-a as a single-dose trigger instead of hCG, specifically to prevent OHSS in high responders.

Despite being a one-time dose (triptorelin 0.2 mg), combined with ovarian stimulation, it still caused significant ovulation delay in the subsequent cycle—unlike the reversible, short-acting suppression typical of antagonists alone. This suggests a prolonged inhibitory effect on the reproductive axis, warranting adjusted monitoring timing for natural FET cycles post-trigger.

When hCG is used for ovulation trigger followed by a freeze-all strategy, its long half-life leads to withdrawal bleeding roughly 10 days after oocyte retrieval. Conversely, GnRH agonist trigger causes rapid luteolysis with withdrawal bleeding occurring 5–7 days post-retrieval [

5,

6,

7]. Despite this quick luteolysis, our findings show about a one-week delay for the reproductive axis to recover and initiate a new natural cycle.

The underlying endocrine mechanism is not fully established but may involve disruption of the natural late luteal phase FSH rise, critical for initiating a new follicular wave, which is likely impaired by the GnRH-a trigger. The GnRH agonist induces a shorter, more transient LH/FSH surge compared to hCG, leading to premature corpus luteum demise and altered luteal phase dynamics, explaining the observed ovulation delay [

40,

41,

42]. Further research is needed to elucidate the precise biological pathways involved.

The primary goal of IVF treatment is to maximize clinical outcomes (pregnancy and live birth) while minimizing patient burden. Hormonal FET offers few clinic visits and complete scheduling flexibility but is associated with potentially worse pregnancy outcomes, including higher rates of hypertensive disorders and abnormal placentation in several recent studies [

13,

14,

15,

16,

43]. Therefore, additional monitoring visits for natural-cycle FET appear justified to achieve superior reproductive results.

5. Conclusion

Following ovarian stimulation and GnRH agonist trigger, monitor natural ovulatory cycles with patience, as ovulation may be delayed by about one week (or longer in some cases). Schedule clinic visits accordingly to optimize monitoring efficiency. This delay does not impair FET cycle outcomes [

13,

14,

15,

16,

20,

21,

22].

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Tatyana Breizman, and Shahar Kol. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Shahar Kol and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding statement

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Ethical considerations

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the IRB committee, Elisha Hospital, 0001-24-MDC, on September 1st, 2024.

Consent to participate

The study has been granted an exemption from requiring written informed consent by the IRB committee, Elisha Hospital, given its retrospective nature.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available since they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants, but are available from the corresponding author [SK] at ivfisrael@gmail.com upon reasonable request.

References

- Roque, M.; Valle, M.; Guimarães, F.; Sampaio, M.; Geber, S. Freeze-all policy: Fresh vs. frozen-thawed embryo transfer. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2015, 30, 387–400.

- Rienzi, L.; Gracia, C.; Maggiulli, R.; et al. Oocyte, embryo and blastocyst cryopreservation in ART: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2017, 23, 15–31.

- Devroey, P.; Polyzos, N.P.; Blockeel, C. An OHSS-free clinic by segmentation of IVF treatment. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 2593–2597.

- Papanikolaou, E.G.; Tournaye, H.; Verpoest, W.; et al. Early and late ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: Early pregnancy outcome and profile. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 20, 636–641.

- Humaidan, P.; Kol, S.; Papanikolaou, E.G. GnRH agonist for triggering of final oocyte maturation: Time for a change of practice? Hum. Reprod. Update 2011, 17, 510–524.

- Engmann, L.; DiLuigi, A.; Schmidt, D.; et al. The use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist for triggering of final oocyte maturation in high risk patients undergoing in vitro fertilization: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 89, 84–91.

- Fatemi, H.M.; Popovic-Todorovic, B. Implantation in assisted reproduction: A look at endometrial receptivity. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2013, 27, 530–538.

- Groenewoud, E.R.; Cohlen, B.J.; Al-Omar, O.; et al. Immediate versus postponed frozen embryo transfer in women with a failed fresh IVF attempt. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 1232–1240.

- Mackens, S.; Santos-Ribeiro, S.; van de Vijver, A.; et al. Frozen embryo transfer: A review on the optimal endometrial preparation and timing. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 2234–2242.

- Ghobara, T.; Vandekerckhove, P. Cycle regimens for frozen-thawed embryo transfer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD003414.

- Groenewoud, E.R.; Macklon, N.S.; Cohlen, B.J. The natural cycle as the simplest form of ovarian stimulation in assisted reproduction: A review. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2013, 28, 669–680.

- Fatemi, H.M.; Kyrou, D.; Bourgain, C.; et al. Cryopreserved-thawed human embryo transfer: Natural versus artificial endometrial preparation. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 2054–2057.

- von Versen-Höynck, F.; Schaub, A.M.; Chi, Y.Y.; et al. Increased preeclampsia risk and altered placental hormone expression after programmed frozen embryo transfer. Hypertension 2019, 73, 640–648.

- Ginström Ernstad, E.; Wennerholm, U.B.; Khatibi, A.; et al. Neonatal and maternal outcome after frozen embryo transfer: A Swedish cohort study. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 125–132.

- Saito, K.; Kuwahara, A.; Ishikawa, T.; et al. Endometrial preparation methods for frozen–thawed embryo transfer and associated maternal and neonatal outcomes: A nationwide cohort study. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 34, 1102–1111.

- Mackens, S.; Polyzos, N.P.; van de Vijver, A.; et al. Frozen single euploid blastocyst transfer in a natural versus artificial cycle: A retrospective cohort study. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 113, 897–905.

- Brosens, I.; Pijnenborg, R.; Vercruysse, L.; Romero, R. The “great obstetrical syndromes” are associated with disorders of deep placentation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 204, 193–201.

- Jabbour, H.N.; Kelly, R.W.; Fraser, H.M.; Critchley, H.O. Endocrine regulation of menstruation. Endocr. Rev. 2006, 27, 17–46.

- Conrad, K.P.; Davison, J.M. The renal circulation in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia: Is there a place for relaxin? Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2014, 306, F1121–F1135.

- Bourdon, M.; Santulli, P.; Maignien, C.; et al. Immediate versus delayed frozen embryo transfer after failed IVF/ICSI cycle: A retrospective cohort study. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2019, 38, 739–748.

- Santos-Ribeiro, S.; Polyzos, N.P.; Haentjens, P.; et al. Is there a preferred interval between failed fresh and frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles? Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 2580–2586.

- Ozgur, K.; Berkkanoglu, M.; Bulut, H.; et al. Immediate versus delayed frozen embryo transfer in freeze-all cycles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2023, 47, 251–261.

- Fatemi, H.M.; Veleva, Z.; Borini, A.; et al. Optimizing natural cycles for frozen-thawed embryo transfer. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 1030–1033.

- Choi, M.H.; Jee, B.C.; Ku, S.Y.; Suh, C.S.; Kim, S.H. Natural cycle frozen-thawed embryo transfer in women with regular menstrual cycles. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2015, 58, 542–548.

- Cédrin-Durnerin, I.; Théron, L.; Belaisch-Allart, J.; et al. Timing of frozen–thawed embryo transfer in natural cycles. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2011, 23, 486–492.

- Griesinger, G. Ovarian stimulation and luteal phase endocrinology. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2012, 24, 249–252.

- Humaidan, P.; Alsbjerg, B.; Bungum, L.; et al. GnRH agonist trigger and luteal phase supplementation with low-dose hCG: A new treatment regimen in IVF. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2010, 21, 455–461.

- Al-Inany, H.G.; Youssef, M.A.; Aboulghar, M.; et al. GnRH antagonist protocols for IVF. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 4, CD001750.

- Kolibianakis, E.M.; Tournaye, H.; Devroey, P. The GnRH antagonist in ovarian stimulation for IVF. Hum. Reprod. Update 2005, 11, 425–441.

- Orvieto, R.; Patrizio, P. GnRH agonist triggering of final follicular maturation—A step toward safer IVF. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 2013, 18, 1–4.

- Barbosa, M.W.P.; Silva, A.A.; Navarro, P.A.; et al. Luteal support in frozen embryo transfer cycles: A randomized trial comparing progesterone and dydrogesterone. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 113, 1150–1157.

- Farhi, J.; Ben-Haroush, A. Distribution of causes of infertility in patients attending primary fertility clinics in Israel. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2011, 13, 51–54.

- Miller, P.B.; Soules, M.R.; et al. Timing of hormone changes in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 1437–1442.

- Groenewoud, E.R.; et al. Natural cycle frozen–thawed embryo transfer: A survey of current practice. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2023, 47, 789–797.

- Albano, C.; Grimbizis, G.; Smitz, J.; et al. The endocrine effects of single-dose triptorelin for triggering of final oocyte maturation. Hum. Reprod. 2000, 15, 1896–1901.

- Bäckström, T.; et al. Endocrine profiles after a single dose of triptorelin in healthy women. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 1991, 125, 205–212.

- Daya, S. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist protocols for in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 2000, 73, 215–226.

- Tarlatzis, B.C.; Zepiridis, L. Ovarian stimulation: GnRH agonists versus antagonists. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1127, 33–40.

- Griesinger, G.; von Otte, S.; Schroer, A.; et al. Long vs. antagonist protocols in IVF. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2005, 11, 370–375.

- Itskovitz, J.; Boldes, R.; Levron, J.; Erlik, Y.; Kahana, L.; Brandes, J.M. Induction of preovulatory luteinizing hormone surge and prevention of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome by gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist. Fertil. Steril. 1991, 56, 213–220.

- Messinis, I.E. Ovarian feedback, follicle development and the role of gonadotropins in the menstrual cycle. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2006, 12, 442–451.

- Filicori, M.; Fazleabas, A.; Huhtaniemi, I.; et al. Novel concepts of human chorionic gonadotropin: Reproductive system interactions and potential in the management of infertility. Fertil. Steril. 2005, 84, 275–284.

- Ginström Ernstad, E.; et al. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes after programmed vs natural FET. BJOG 2022, 129, 1700–1710.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).