Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Definition of input parameters and functional requirements;

- Application of generative design in development of the spur gear;

- Material selection for gear wheels;

- Analysis and simulation;

- Comparison and selection of optimal solution.

2.1. Input Parameters and Geometric Characteristics of Gear Wheel

2.2. Application of Generative Design in Proposal of Spur Gear

- Autodesk Fusion 360 – enables a comprehensive CAD/CAM solution that integrates generative design directly into the design environment and allows the definition of technological, functional, and geometrical constraints. It is popular for its intuitive interface and broad accessibility.

- Siemens NX (Generative Design) – is an advanced tool primarily used in industrial applications, offering a high level of control over the design process and strong integration with other CAE modules.

- PTC Creo (Generative Topology Optimization) – provides shape optimization with an emphasis on integration into the design process and linkage with FEM analysis.

- SolidWorks (3DEXPERIENCE/Topology Optimization) – is widely known in mechanical engineering, it provides topology optimization capabilities and integration with stress analysis.

- Topology – is a modern software focused on advanced shape optimization, suitable for additive manufacturing, offering a high degree of parameterization and computational control.

- Creation of a new generative study and basic project setup;

- Definition of boundary (obstacle) geometry;

- Specification of the design space for the generative proposal;

- Definition of boundary conditions – model constraints;

- Definition of design conditions – loads;

- Definition of design criteria in terms of manufacturing and functionality;

- Selection and definition of materials in generative design.

2.2.1. Creating of New Generative Study and Basic Project Setup

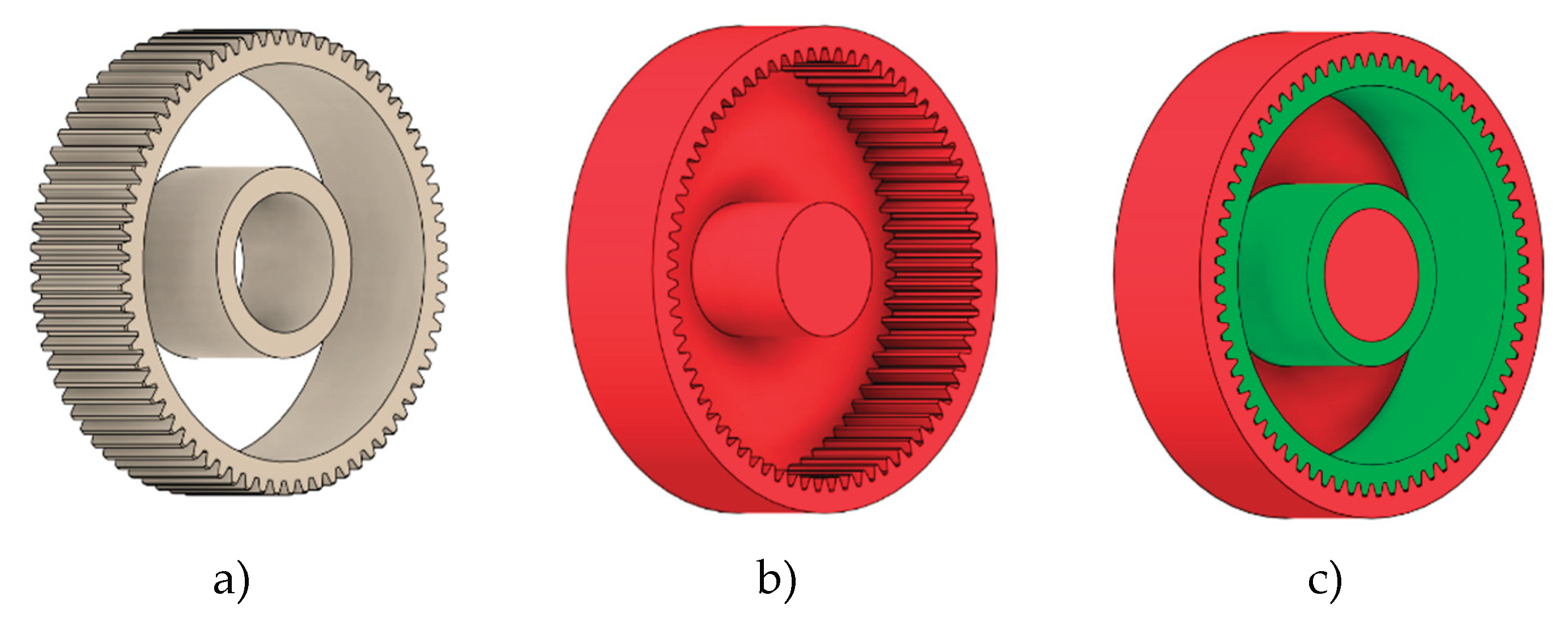

2.2.2. Defining of Bounding (Obstacle) Geometry

2.2.3. Defining of Design Space for Generative Proposal

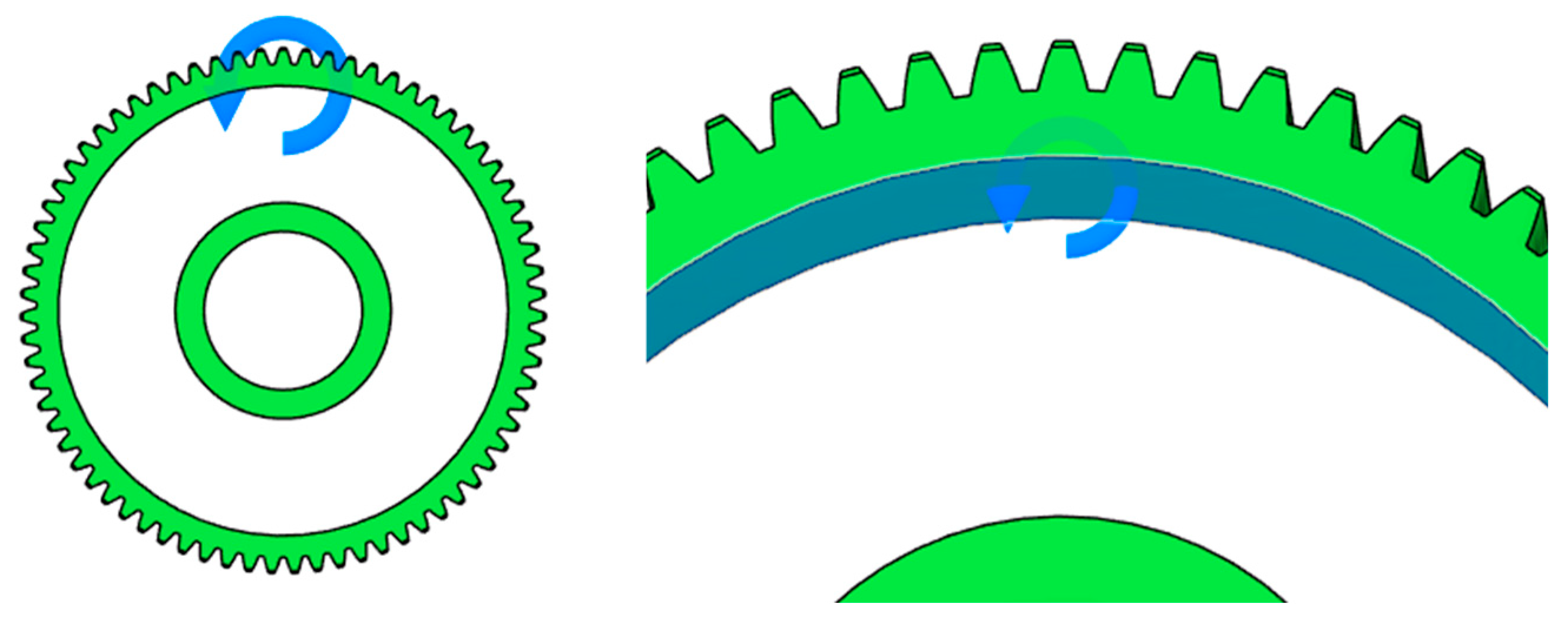

2.2.4. Defining of Boundary Conditions – Model Constraints

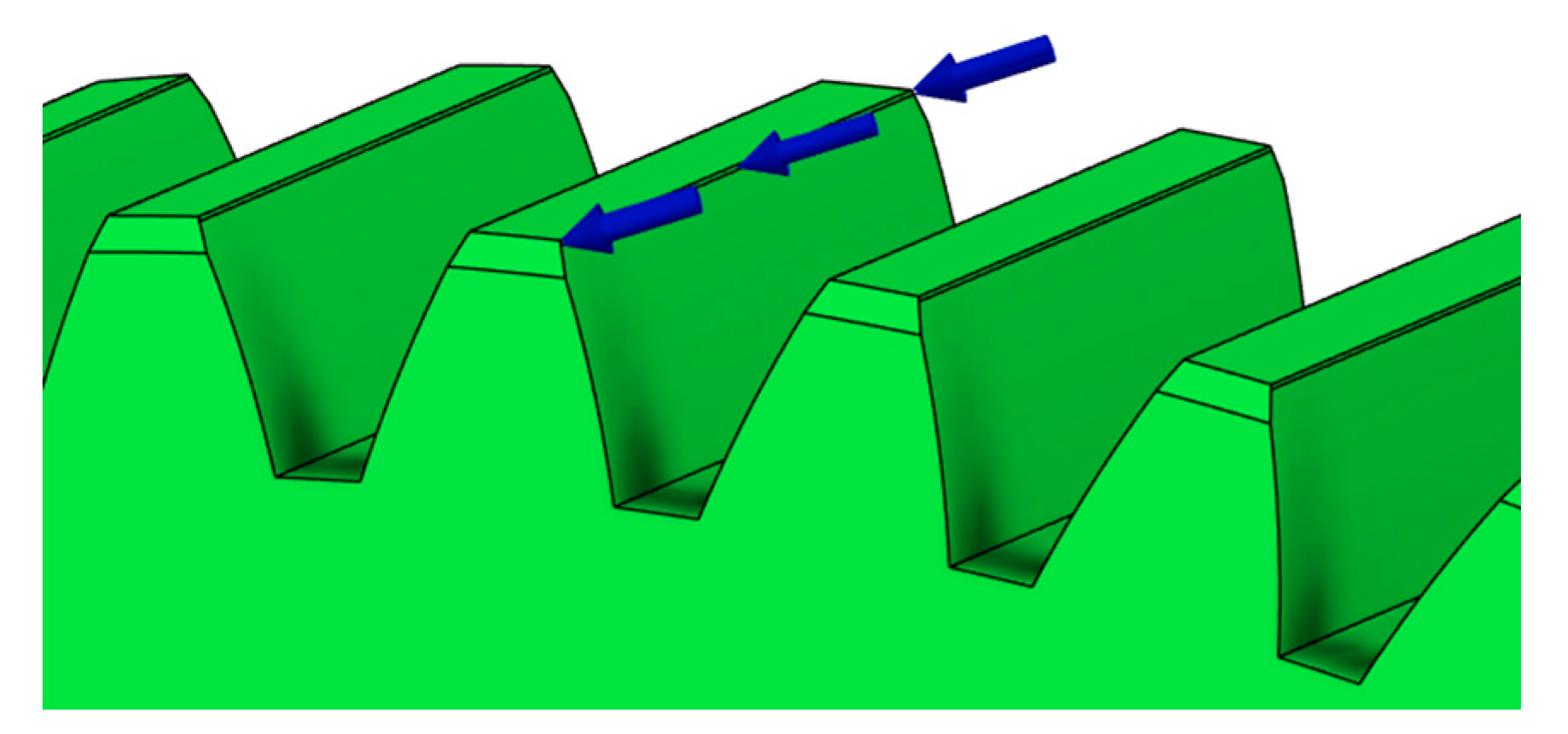

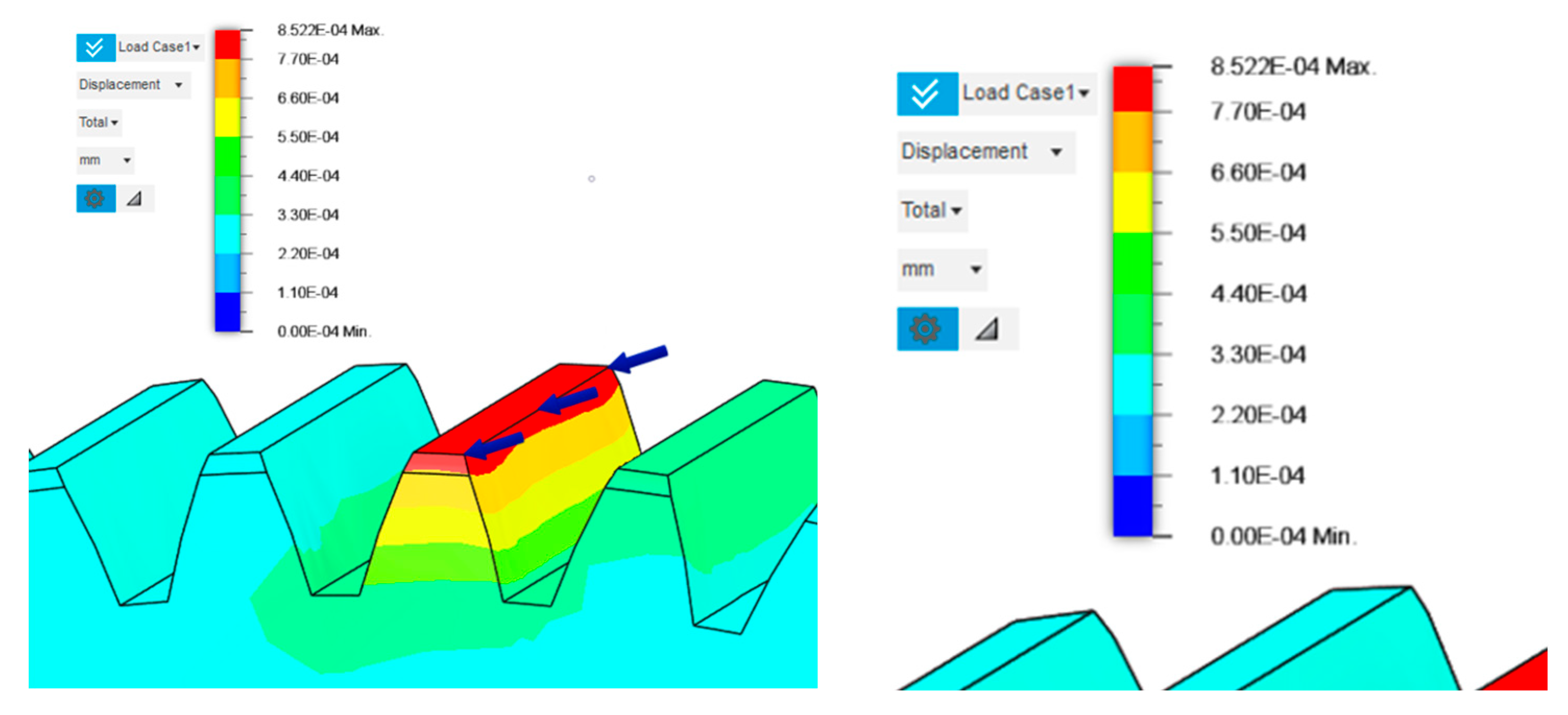

2.2.5. Defining of Design Conditions – Loads

2.2.6. Definition of Design Criteria in Terms of Manufacturing and Functionality

- Safety factor – defines the ratio between the material’s yield strength and the maximum von Mises stress within the model. This parameter ensures that the generated design possesses a sufficient strength reserve and that the material’s load-bearing capacity is not exceeded.

- Target mass – specifies the desired mass of the resulting model and enables a balance to be achieved between material savings and the preservation of the required stiffness. In this study, the design is oriented towards reducing the weight of the gear wheel while maintaining tooth stiffness and the overall strength of the component.

- Modal frequency – allows the inclusion of dynamic performance requirements in the computation. By specifying the minimum frequency of the first natural mode, it is ensured that the design will not be susceptible to resonance at the operational rotational speeds of the gear wheel.

- Displacement (deformation) limit – defines the allowable displacement values in specific regions of the model. This parameter is essential for maintaining the geometric accuracy of the gear teeth and ensuring reliable tooth engagement during torque transmission.

- Additive manufacturing (3D-printing) – allows the creation of complex and organic shapes that would be impossible to produce using conventional methods. It is particularly suitable for prototypes or lightweight structures with an emphasis on saving material.

- Subtractive manufacturing (machining) – includes processes such as milling or turning. Within generative design, it is possible to define the machining direction, tool access axes, and geometric constraints to ensure that the resulting shape is suitable for this type of manufacturing.

- Casting or forging – is mainly used in mass production, where emphasis is placed on repeatability, surface quality, and dimensional accuracy. Generative design can assist in optimising the shape of the casting or forging to reduce weight while maintaining strength.

2.2.7. Selection and Definition of Materials in Generative Design

- Yield strength – is used to calculate the safety factor, ensuring that the design does not exceed the material’s load-bearing capacity and remains resistant to operational loads.

- Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio – these mechanical characteristics are crucial in solving linear stress and deformation problems, enabling the generation of geometries that optimally combine stiffness and weight.

- Material density – is used in calculating the model’s weight as well as in simulations of gravitational loading or dynamic behaviour. The material density must be defined correctly to ensure that the physical simulations accurately influence the resulting geometry of the gear wheel.

2.3. Material Selection for Gear Wheels

- Additive manufacturing (3D-printing)

- PA12 GF30 (Nylon with 30% glass fiber reinforcement);

- CarbonX PA-CF (Nylon reinforced with carbon fibers);

- Zytel® PA-CF by DuPont (carbon fiber–reinforced nylon.

- 2.

- Machining (3-axis and 5-axis milling)

- Carbon steel S45C (equivalent to C45) – suitable for highly loaded gears requiring high strength and toughness after heat treatment;

- Stainless steel SUS420J2 – appropriate for environments demanding resistance to corrosion and wear, such as applications involving contact with water or humidity;

- Alloy steel SCr415 – a material intended for case hardening, suitable for gears requiring a hard surface combined with a tough core;

- Aluminum alloy EN AW-7075 – used for lightweight gears where low weight is prioritized while maintaining high strength.

- 3.

- Casting

3. Results

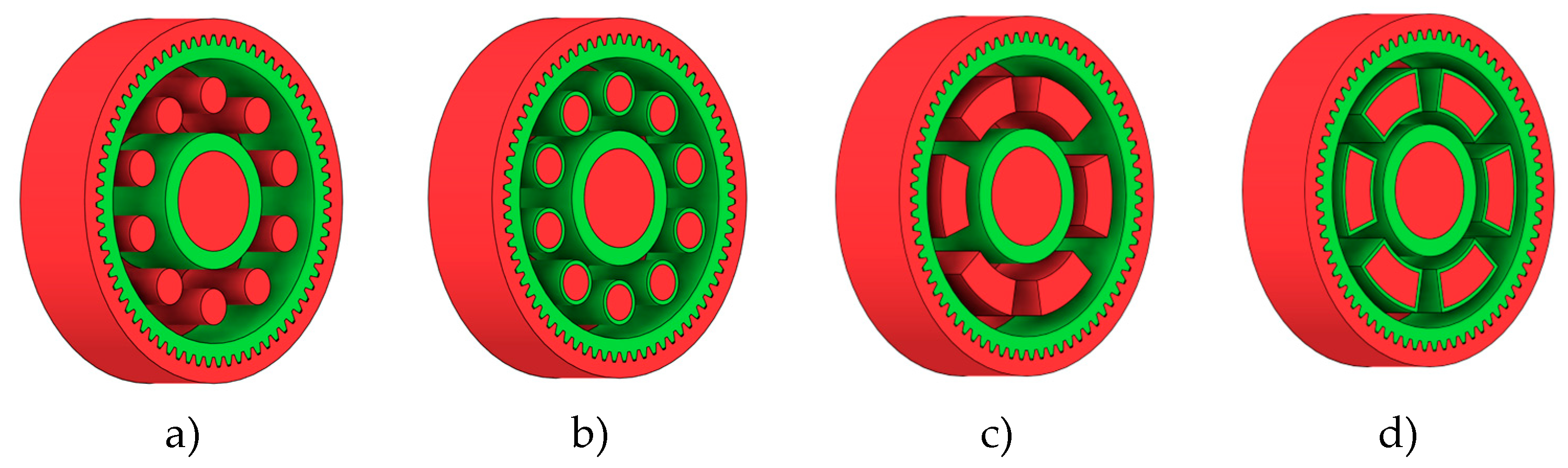

3.1. Generation of Gear Wheel Body Geometry with Definition of Basic Geometrical Constraints

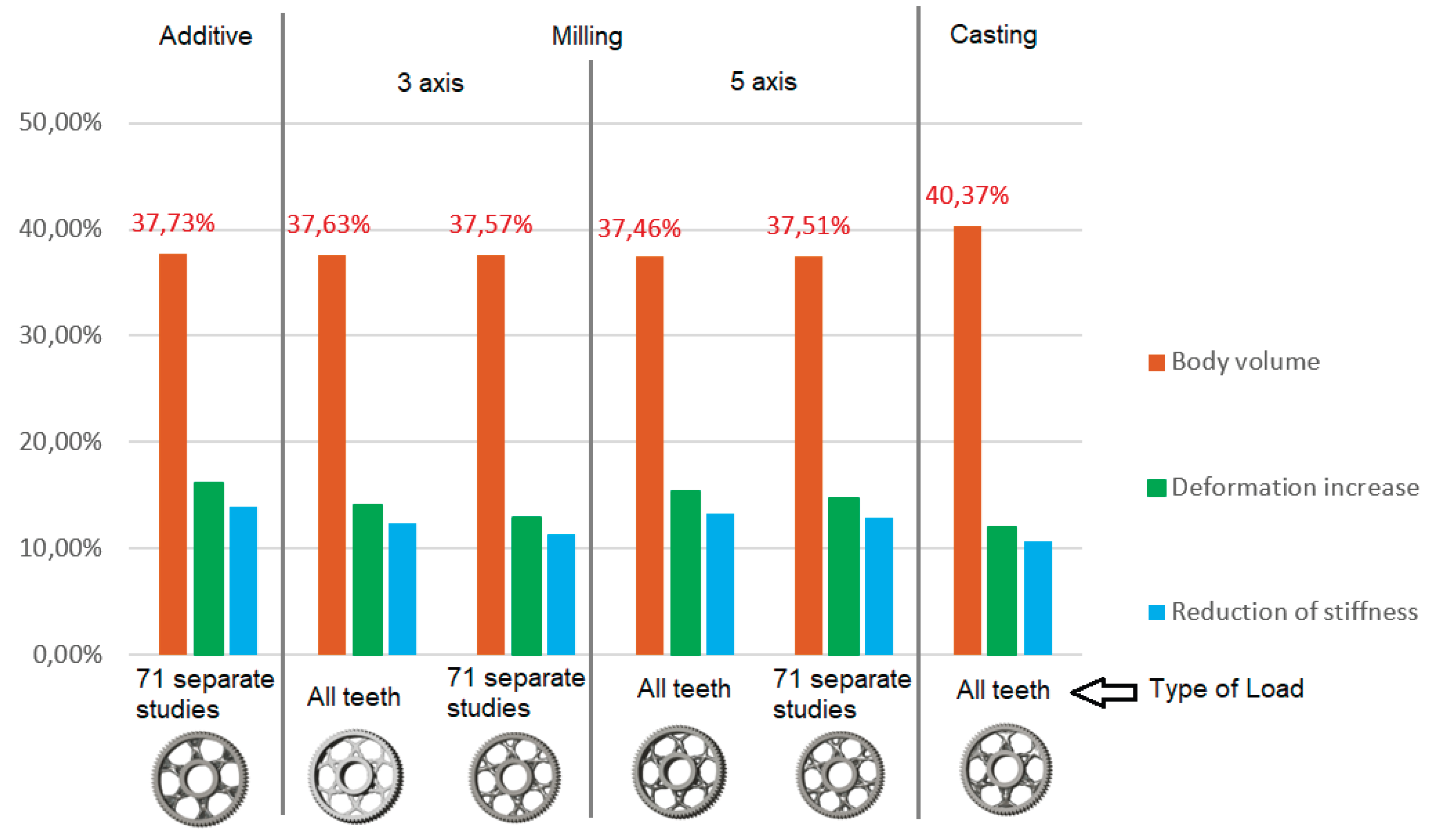

3.2. Design Optimization Using Refinement of Geometric Constraints

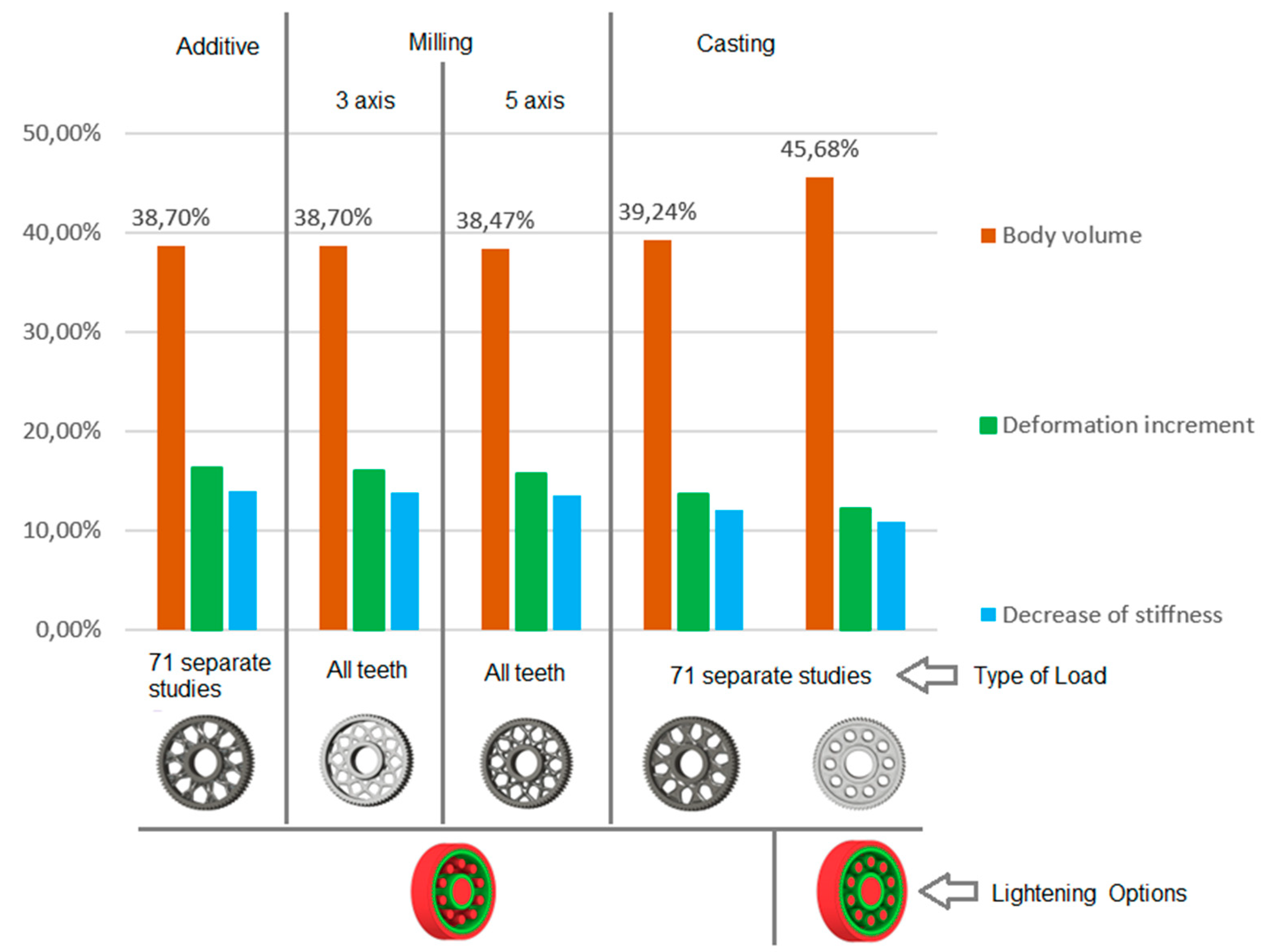

3.3. Design Optimization Using Gear-Tooth Stiffness and Volume of Body Wheel Minimization

4. Conclusions

- Regarding the application of loads in Autodesk Fusion 360, the most suitable approaches involve either applying force to all teeth simultaneously or performing a series of individual simulation studies in which each tooth is loaded separately, both of which provide stable and representative results for generative design;

- When defining geometric constraints in the generative design process, it is preferable to avoid retaining material around lightening holes, as this tends to limit optimization space without providing a significant stiffness benefit;

- In the design of the gear body for additive manufacturing, it is optimal to conduct a series of individual load studies and to avoid leaving material around lightening holes, which allows achieving lower weight and a more efficient internal structure without compromising functionality;

- For subtractive manufacturing such as milling, the use of 5-axis machining is advantageous because it provides greater geometric freedom for material reduction, and applying the load to all teeth simultaneously during simulations yields consistent results in stiffness and deformation analyses;

- In casting, circular lightening holes benefit from retaining material around the holes, which improves local stiffness and resistance to deformation, while loads should be applied to all teeth simultaneously. For non-circular or shaped lightening holes, material near the holes should be removed, and loads should be applied through a series of individual studies to better capture local stress effects.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barbieri, L.; Muzzupappa, M. Performance-Driven Engineering Design Approaches Based on Generative Design and Topology Optimization Tools: A Comparative Study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradišar, L.; Klinc, R.; Turk, Ž.; Dolenc, M. Generative Design Methodology and Framework Exploiting Designer-Algorithm Synergies. Buildings 2022, 12, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Delgado, D.; Jaen-Sola, P.; Oterkus, E. A New Zero Waste Design for a Manufacturing Approach for Direct-Drive Wind Turbine Electrical Generator Structural Components. Machines 2024, 12, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Ying, H. Lightweight Design Process Combining Generative Design and Topology Optimization Based on Fusion 360 and ANSYS: A Case Study of a Biped Robot’s Arch Component. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2025, 26, 1775–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartomacıoğlu, S.; Kaya, E.; Eker, B.; Dağlı, S.; Sarıkaya, M. Characterization, Generative Design, and Fabrication of a Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Industrial Robot Gripper via Additive Manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 3714–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradišar, L.; Dolenc, M.; Klinc, R. Towards Machine Learned Generative Design. Autom. Constr. 2024, 159, 105284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.; Leary, M.; Downing, D.; Brandt, M. Generative Design of Space Frames for Additive Manufacturing Technology. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 127, 4619–4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Yoo, S.; Kang, N. Generative Design by Reinforcement Learning: Enhancing the Diversity of Topology Optimization Designs. Comput.-Aided Des. 2022, 146, 103225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, H. Manufacturability-Aware Deep Generative Design of 3D Metamaterial Units for Additive Manufacturing. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2024, 67, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Jung, Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, I.; Kang, N. Deep Generative Design: Integration of Topology Optimization and Generative Models. J. Mech. Des. 2019, 141, 111405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.; Zhang, W.; Friel, I.; Robinson, T.; McConnell, R.; Nolan, D.; Kilpatrick, P.; Barbhuiya, S.; Kyle, S. Generative Design for Additive Manufacturing Using a Biological Development Analogy. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2022, 9, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podroužek, J.; Marcon, M.; Ninčević, K.; Wan-Wendner, R. Bio-Inspired 3D Infill Patterns for Additive Manufacturing and Structural Applications. Materials 2019, 12, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Hwang, K.H.; Park, J.H.; Kang, N. Integrating Deep Learning into CAD/CAE System: Generative Design and Evaluation of 3D Conceptual Wheel. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2021, 64, 2725–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutiš, V.; Novosad, P.; Záděra, A.; Kaňa, V. Requirements for Hybrid Technology Enabling the Production of High-Precision Thin-Wall Castings. Materials 2022, 15, 3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgyai, N.; Máté, M.; Oancea, G.; Dragoi, M.-V. Gear Hobs—Cutting Tools and Manufacturing Technologies for Spur Gears: The State of the Art. Materials 2024, 17, 3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrakova, E.A.; Korolev, N.O.; Brovkina, Y.I. Topological Optimization of Gear Wheels. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Industrial Engineering; Radionov, A.A., Gasiyarov, V.R., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cristian, L.-N.; Bodur, O.; Walcher, E.; Grozav, S.; Ceclan, V.; Durakbasa, N.M.; Sterca, D.A. Study of Improving Spur Gears with the Generative Design Method. In Towards Industry 5.0; Durakbasa, N.M., Gençyılmaz, M.G., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 473–485. ISBN 978-3-031-24456-8. [Google Scholar]

- Birosz, M.T.; Bátorfi, J.G.; Andó, M. Extending the Usability of the Force-Flow Based Topology Optimization to the Process of Generative Design. Meccanica 2023, 58, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.; Michatz, M.; Frey, A.; Lutter-Guenther, M.; Schlick, G.; Reinhart, G. Methodical Software-Supported, Multi-Target Optimization and Redesign of a Gear Wheel for Additive Manufacturing. Procedia CIRP 2020, 91, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Orquera, M.; Millet, D.; Bernard, A. A New Hybrid Generative Design Method for Functional & Lightweight Structure Generation in Additive Manufacturing. Procedia CIRP 2023, 113, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).