1. Introduction

Many models of symbolic reasoning and cognition treat operators such as “+” as having a fixed meaning that is applied deterministically to well-defined operands. However, both human judgement and contemporary large language models exhibit a richer behaviour: operators are polysemic, internal processing involves uncertainty and revision, and intermediate states can be far from Boolean truth values. At the same time, advances in probabilistic spintronic hardware (superparamagnetic tunnel junctions, SMTJs) have made it possible to implement physically the kind of stochastic dynamics traditionally simulated in Boltzmann machines and related models.

On the hardware side, SMTJ-based probabilistic computers have been framed as a concrete realization of early proposals by Feynman and Hinton for stochastic, physics-inspired computation [

1]. Energy-efficient stochastic computing primitives based on SMTJs have been analysed in detail, highlighting their suitability as low-power

p-bit sources and stochastic logic elements [

2], while broader surveys of unconventional and neuromorphic computing with magnetic tunnel junctions review their use in probabilistic networks, Ising/Boltzmann machines and related architectures [

3]. In parallel, SMTJs operated in the superparamagnetic regime have been shown to provide true random bit streams at nanosecond time scales that pass standard NIST statistical tests, with explicit applications to Monte Carlo simulation and neuromorphic learning circuits [

4]. Taken together, these works establish SMTJs as compact, CMOS-compatible entropy sources and stochastic computing primitives.

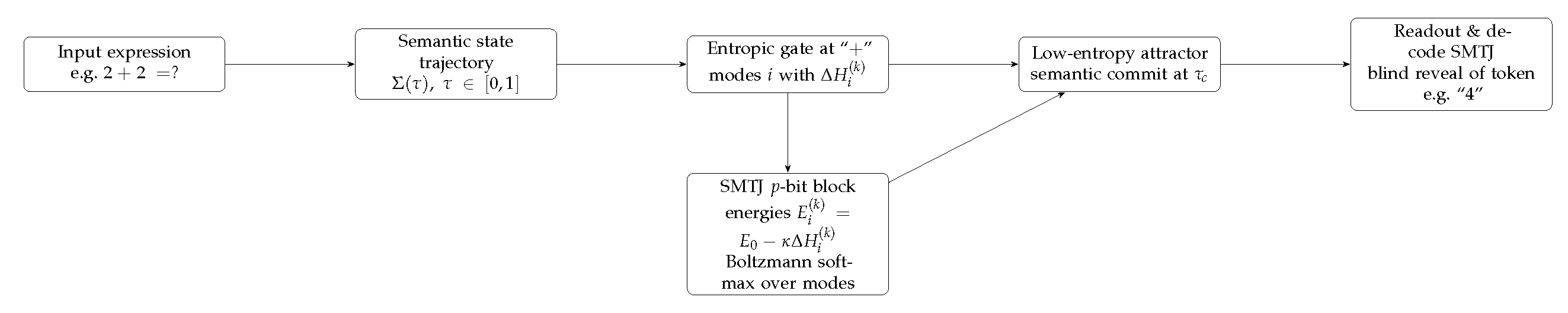

Figure 1.

High-level architecture of the ESDM–SMTJ pipeline. An input expression (e.g. ) is mapped to a semantic trajectory under a program-specific dynamics . At each occurrence of an ambiguous operator such as “+”, an entropic gate evaluates the expected entropy drop for each semantic mode i and sets corresponding energy levels in an SMTJ p-bit block. The Boltzmann statistics of the SMTJs implement a softmax over modes, feeding back a concrete mode choice that drives towards a low-entropy attractor (semantic commit). A final readout and decoding of SMTJ states realizes a blind reveal of the output token.

Figure 1.

High-level architecture of the ESDM–SMTJ pipeline. An input expression (e.g. ) is mapped to a semantic trajectory under a program-specific dynamics . At each occurrence of an ambiguous operator such as “+”, an entropic gate evaluates the expected entropy drop for each semantic mode i and sets corresponding energy levels in an SMTJ p-bit block. The Boltzmann statistics of the SMTJs implement a softmax over modes, feeding back a concrete mode choice that drives towards a low-entropy attractor (semantic commit). A final readout and decoding of SMTJ states realizes a blind reveal of the output token.

In this work we propose ESDM–SMTJ, an Entropic Semantic Dynamics Model that couples a high-level semantic state space with low-level probabilistic hardware.

The internal state of a system is represented as a trajectory in a layered state space, where parametrizes an internal computational time. Expressions such as define program-specific dynamics that update while ambiguous operators (e.g. “+”) are treated as multi-modal and resolved via an entropic gating mechanism.

At the hardware level, we assume an SMTJ-based p-bit substrate whose Boltzmann statistics implement softmax sampling over a finite set of modes. For each occurrence of an ambiguous operator, the semantic layer computes expected entropy drops associated with choosing mode i at position k. These values are converted into energy levels for a local SMTJ block, which in turn feeds back a sampled mode . This loop drives the trajectory through phases of rumination, insight and stabilization, and leads naturally to notions of semantic commit and blind reveal of the final token.

Relation to SMTJ-based TRNG and Monte Carlo simulators.

Conceptually, ESDM–SMTJ sits one level above existing SMTJ-based true random number generators and Monte Carlo accelerators. In a conventional TRNG pipeline, SMTJs are wired as entropy sources that produce (approximately) independent random bits which are then consumed by an external software or digital model. Here, by contrast, the same thermal telegraph noise is interpreted as a physically grounded

entropic gate: SMTJ

p-bits implement a softmax over semantic modes, with energies

directly tied to predicted entropy drops

in the output distribution. Rather than driving an unrelated Monte Carlo sampler, SMTJ randomness modulates the internal trajectory

itself, shaping when and how the system commits to an attractor (e.g. a Peano-consistent mapping

) or, in near-degenerate regimes, occasionally falls into an anomalous attractor (e.g.

). In this sense, ESDM–SMTJ can be viewed as a semantic and cognitive layer on top of the same SMTJ-based TRNG and stochastic-computing primitives developed in Refs. [

1,

2,

3,

4].

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 formalizes the semantic state space, entropic gate and SMTJ coupling.

Section 3 presents toy examples, including arithmetic judgements such as

and controlled anomalies.

Section 4 discusses implementation aspects on SMTJ hardware, and

Section 5 sketches a quantum extension where semantic modes become basis states of a Hamiltonian.

Section 6.1 situates ESDM–SMTJ with respect to prior SMTJ-based

p-bit Boltzmann machines and TRNG architectures. We conclude in

Section 6 with open questions and possible applications to BCI/EEG-based authentication.

2. Formal Model

In this section we formalize the core components of the ESDM–SMTJ framework. We start from an abstract semantic state space and a notion of expression-induced dynamics, then introduce the entropic gate, its coupling to SMTJ p-bit blocks and the definitions of semantic commit and blind reveal.

2.1. Semantic State Space

Let

denote a finite vocabulary of tokens (e.g. digits, operators such as “+” and “=”, and special query symbols such as “?”). We write expressions as finite sequences

The internal semantic state of the system lives in a compact metric space

, which we will refer to as the

semantic state space. We write

for a generic state and

for an internal computational time parameter that runs from the onset of processing an expression (

) to the deployment of a final response (

).

To reflect the existence of qualitatively different regimes (e.g. low-level sensory encodings, higher-level symbolic representations), we assume that

is

layered:

where each

is a submanifold or subspace of states associated with a “layer” or “plane” of representation. In many applications one may take

and view the global state as

with

, but the construction does not depend on a specific parametrization.

In later sections we will sometimes distinguish between a slow fingerprint component B (e.g. subject identity) and a fast content component , writing , but for the formal development it suffices to treat as a single state variable.

2.2. Output Distribution and Entropy

We assume a finite set

of possible output tokens (e.g. digits, “yes/no”, special symbols). An

observation family is a collection of maps

such that for every

,

We interpret

as the

acceptability or probability assigned to output

x when the internal state is

. For a fixed expression

e the induced output distribution at time

is

Given

we define the

semantic output entropy at time

as the Shannon entropy

Low values of correspond to near-deterministic judgements (high confidence), while high values correspond to states of indecision or strong ambiguity.

2.3. Expression-Induced Dynamics

Each expression

induces a

program-specific dynamics on the semantic state space. Formally, we assume the existence of a family of maps

such that

and

is continuous for each

. Given an initial state

, the trajectory under

e is

In many settings it is convenient to work with a discrete time index

aligned with the token sequence, and to set

We then regard the local update induced by token

as the transition

for some family of token-specific maps

. The continuous-time

can be obtained, for example, by interpolating between these discrete updates.

2.4. Ambiguous Operators and Semantic Modes

We distinguish a subset

of

ambiguous operators, such as “+”, whose meaning is not fixed but can be instantiated by one of several semantic modes depending on context. For each

we define a finite set of modes

(e.g. standard arithmetic addition, a rare erroneous mode, a metaphorical or domain-specific reinterpretation).

Let

k be a position in the expression

e such that

. We denote by

(or equivalently by the discrete index

k) the internal time where the system processes this occurrence of

o, and write

for the state just before applying the operator at position

k.

For each mode

we assume the existence of a

mode-conditioned continuation of the dynamics: starting from

and forcing mode

i at position

k, we obtain a hypothetical trajectory

and in particular a terminal entropy

We do not require that this continuation be implemented explicitly in the physical hardware; it can be understood as an effective predictive model used by the entropic gate.

2.5. Entropic Gate and Expected Entropy Drop

The

entropic gate at position

k evaluates each mode

by its predicted reduction of output entropy. Let

be the current output entropy at the moment the operator is about to be applied. We define the expected entropy drop for mode

i at position

k as

Modes that are expected to lead to clearer, more decisive judgements (smaller final entropy) have larger .

The entropic gate then defines a probability distribution over modes via a softmax:

where

is an inverse-temperature parameter controlling how strongly the gate favours high

. The choice of semantic mode at position

k is then modelled as a random variable

with

Conditioned on a realized mode

at position

k, the state update becomes

where

denotes the token update map specialized to mode

i of operator

o.

2.6. SMTJ Implementation of the Gate

The ESDM–SMTJ model assumes that the softmax distribution (

10) is realized at the hardware level by a local block of superparamagnetic tunnel junctions.

For each ambiguous occurrence

we associate a set of effective energy levels

for some constants

and

. These energy levels parametrise a classical Boltzmann distribution over modes,

where

is Boltzmann’s constant and

T is the effective temperature of the SMTJ block.

Substituting the definition of

yields

Up to normalization, this coincides with the entropic gate distribution (

10) with

. Thus the SMTJ block physically implements the entropic gate by sampling from the Boltzmann distribution defined by mode-dependent energies

.

We denote by

the random mode index generated by this hardware sampling process and identify

2.7. Semantic Commit and Blind Reveal

The entropy curve induced by the dynamics and the entropic gate often exhibits distinct phases. We are particularly interested in intervals where remains high and relatively flat (rumination), followed by sharp drops (insight-like transitions) and stabilization near a low-entropy value.

Definition 1

(Semantic commit). Let and be chosen thresholds. We say that a trajectory undergoessemantic commitfor expression e at internal time if

, and

for all .

In this regime the output distribution is nearly time-invariant and highly concentrated on a subset of .

Semantic commit captures the idea that, internally, the system has effectively “made up its mind” before producing any observable output.

The final observable response is produced at some by reading out a separate SMTJ block dedicated to output tokens.

Let

denote the space of microstates of this output block (e.g. binary magnetization configurations of a small array of junctions) and let

be a fixed decoding map from microstates to tokens (e.g. by nearest-codeword in Hamming distance to a set of reference patterns). At

the SMTJ output block is sampled according to a distribution concentrated near a configuration consistent with the committed semantic state, and the observed token is

where

is the sampled microstate.

Definition 2

(Blind reveal).

We call the map

theblind revealof the expression e under the ESDM–SMTJ dynamics. Internally, semantic commit may occur at , binding the response; externally, an observer only gains access to a single token revealed at through SMTJ readout and decoding.

In this sense, the ESDM–SMTJ model naturally separates the hidden formation of a judgement (semantic commit) from its eventual exposure via a discrete observable output (blind reveal). Subsequent sections instantiate these abstractions in toy arithmetical examples and discuss how mis-tuned parameters can lead to rare anomalous judgements such as .

3. Toy Examples and Case Studies

In this section we instantiate the abstract ESDM–SMTJ model on a minimal arithmetic judgement. We use the expression as a running example and contrast a “normal” regime, where a Peano-consistent attractor dominates, with an “anomalous” regime where mis-tuned parameters lead to rare events.

3.1. Setup: Expression and Output Space

We take the token sequence

and restrict attention to two candidate outputs,

The remaining formalism applies equally to larger output alphabets.

Given a trajectory

in the semantic state space

, the observation family

induces a time-dependent output distribution

and a semantic output entropy

We discretize the internal time as

At the system has not yet processed the expression; at it is ready to produce an answer.

3.2. Entropic Gate at the “+” Position

The operator “+” at position

is treated as ambiguous, with two semantic modes:

where

N denotes the standard arithmetic mode and

R denotes a rare, context-dependent or erroneous mode.

Let

be the state just before processing the “+” at position

, and let

be the corresponding output entropy. For each mode

we consider the hypothetical continuation of the dynamics where mode

i is forced at position 2, resulting in a terminal entropy

at

. The entropic gate computes

These values are converted into mode probabilities via the softmax

and implemented physically in an SMTJ block with energies

3.3. Normal Regime: SMTJ–Peano Attractor

We first analyse a regime where the parameters and predictive model are tuned so that the standard arithmetic mode

N is strongly favoured. For illustration, suppose that at

the output distribution over

is nearly uniform:

so that

If the system anticipates that choosing mode

N will lead to a highly concentrated distribution at the end,

then

and the expected entropy drop for the normal mode is large,

In contrast, under the rare mode

R the system may predict a much less decisive final state,

giving

and a small entropy drop

With

sufficiently large, the softmax (

16) then satisfies

so that the SMTJ block overwhelmingly selects mode

N (standard addition). Conditioned on this choice, the subsequent trajectory

is driven towards a low-entropy attractor where

and the semantic output entropy

drops sharply after

before stabilizing near zero.

We say that this attractor realizes an SMTJ–Peano regime: the combination of SMTJ energy landscape and semantic dynamics enforces Peano-consistent behaviour with high probability. Semantic commit occurs at some , when falls below the commit threshold and remains low thereafter. At , the output SMTJ block is read out and decoded to produce a blind reveal .

3.4. Anomalous Regime: Rare Events

We next consider how the same framework can generate rare but systematic anomalies in arithmetic judgements, such as , under mis-tuned parameters or atypical internal states.

One simple route is through a distorted prediction of entropy drops. Suppose that due to noise, mis-estimation of future dynamics or an atypical context, the system assigns similar or even higher expected entropy reduction to the rare mode:

In the first case, the entropic gate becomes nearly indifferent:

while in the second case it may even favour the rare mode

R. At the hardware level this corresponds to an SMTJ energy landscape where the basin associated with mode

R is not sufficiently penalized and can be sampled with non-negligible probability.

Conditioned on

, the mode-conditioned continuation

is now realized in the actual dynamics. The subsequent updates

push the state into a different basin of attraction where the output distribution at late times may satisfy, for instance,

and the entropy

again drops and stabilizes, but around a different mode. Semantic commit still occurs at some

, yet the committed response is now biased towards 5 rather than 4. At

the output SMTJ block, having equilibrated near a microstate decoded as 5, produces a blind reveal

.

From the point of view of the formal model, this behaviour is not a violation of the underlying axioms but an excursion into a different attractor of the coupled semantic–SMTJ system. The same entropic gate that normally stabilizes arithmetic truth can, under mis-tuned or altered energy parameters , stabilize a qualitatively different mapping between input expressions and output tokens.

3.5. C++ CLI Demo and AR(1) Thermal Noise Model

To make the entropic gate more concrete, we implemented a small C++ command–line demo that mirrors the structure of the ESDM–SMTJ model. The program performs three steps:

It builds an EEG–based fingerprint from several synthetic windows using the imaginary part of coherency (as in the original BCI prototype).

It authenticates a new window by computing the distance r to and mapping this to an entropic AUTH_GATE, producing energies and and corresponding softmax probabilities.

It runs a PLUS_GATE for the toy expression , with two modes for “+” (normal Peano mode N and rare anomalous mode R), computes the entropy drops , , the induced energies and the corresponding softmax probabilities , and finally samples a mode and emits the token 4 or 5 as a blind reveal.

In the numerical example used throughout this paper, the CLI yields

so that

and, with a softmax over entropy drops,

In the particular run shown below, the gate samples the rare mode R and produces the anomalous judgement :

=== PLUS_GATE for expression ’2+2=?’ ===

H_before = 0.693147

H_after_N = 0.198515

H_after_R = 0.325083

DeltaH_N = 0.494632

DeltaH_R = 0.368064

E_N = -0.494632

E_R = -0.368064

P_N (normal 2+2=4) = 0.5316

P_R (rare 2+2->5) = 0.4684

Gate-chosen mode: RARE (2+2->5)

Final distribution p_after = (0.1, 0.9)

Emitted token (blind reveal): 5

For the entropic–margin demo, we additionally model the thermal fluctuations at the PLUS_GATE as a discrete–time Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process, i.e. an AR(1) noise model

where

,

encodes the correlation time

of the underlying SMTJ magnetization dynamics, and

sets the effective noise level. In the CLI, we used, for example,

s and

s, corresponding to “Modo ruido: AR(1) correlacionado, tau_corr = 0.01, dt = 0.0002” in the output. The entropic margin process is then written as

and the thermal–shock index

is computed directly from the realised trajectory

.

3.6. Interpretation

The toy example illustrates several aspects of the ESDM–SMTJ model:

Internal processing unfolds as a trajectory with a non-trivial entropy profile , rather than as an instantaneous jump from premise to conclusion.

Ambiguous operators such as “+” are resolved via an entropic gate that predicts future clarity (entropy reduction) and delegates the actual choice of mode to physical sampling in an SMTJ block.

Peano-consistent judgements (e.g. ) correspond to attractors in the joint semantic–SMTJ dynamics, whereas rare anomalies (e.g. ) arise when the entropic gate operates in a nearindifferent regime with small entropic margin and elevated thermal-shock index , so that correlated SMTJ noise can drive the softmax to sample the anomalous mode even though the normal mode has a slight average advantage.

4. Hardware Considerations for SMTJ Implementations

In this section we outline how the abstract ESDM–SMTJ model could be mapped onto realistic superparamagnetic tunnel junction (SMTJ) hardware and how brain–computer interface (BCI) / EEG signals can be incorporated into the semantic state and the entropic gate.

4.1. SMTJ p-Bit Blocks and Mode Selection

We assume that each ambiguous operator occurrence is implemented by a local SMTJ-based “mode selection block” responsible for sampling the mode index .

At a high level, an SMTJ

p-bit can be regarded as a noisy binary element whose magnetization stochastically switches between two states (e.g. parallel and anti-parallel) under thermal fluctuations, with a probability that depends on an effective energy barrier and external bias (current or voltage). In the simplest case of two modes, a single

p-bit with an appropriate readout and bias suffices to realize the softmax (

16); for multiple modes

, a small network of coupled SMTJs can be configured such that each attractor of the network corresponds to one mode.

Concretely, for each occurrence

and mode

we associate an effective energy

computed in the semantic layer as described in

Section 2. This value is then translated into device-level control parameters (e.g. bias currents) for the SMTJ block, shaping the stationary distribution over its microstates so that the induced distribution over mode indices

i matches the entropic gate probabilities

. A small digital or mixed-signal controller can mediate between the semantic processor (which computes

) and the analog SMTJ array (which implements the Boltzmann sampling).

4.2. Time Scales and Coupling to

The ESDM–SMTJ model separates two time scales:

A semantic time scale, parameterized by or its discrete counterpart , on which the state evolves under as tokens are processed and entropic gates are evaluated.

A device time scale, on which SMTJs switch between microstates and the local p-bit networks relax to their stationary distributions given fixed energy parameters .

In a practical implementation one can exploit the fact that SMTJ switching and relaxation typically occur much faster than high-level semantic updates. For each entropic gate evaluation at position k, the semantic processor computes the set , programs the corresponding energies into the SMTJ block, and waits a short dwell time for the p-bits to sample from the resulting Boltzmann distribution. The sampled mode index is then fed back as a discrete event that updates via the mode-specific map .

This design preserves the flexibility of the semantic layer while leveraging the SMTJ hardware as a physical sampler that implements the entropic gate with potentially high energy-efficiency and inherent stochasticity.

4.3. Output SMTJ Block and Code-Based Decoding

The blind reveal mechanism described in

Section 2 can be realized by a dedicated SMTJ output block whose attractors are associated with codewords for each output token

. Let

denote the configuration space of this block (e.g. binary patterns of a small SMTJ array), and let

be a set of reference codewords, one per token. The decoding map

can then be defined by nearest-codeword in Hamming or Euclidean distance:

During the semantic commit phase, the semantic processor gradually biases the output SMTJ block (through control currents or equivalent parameters) so that its energy landscape favours the basin associated with the codeword matching the internally committed token . At the block is sampled, producing a microstate that, with high probability, lies close to ; applying R yields the blind reveal .

4.4. Embedding BCI/EEG Features into the Semantic State

One of the motivations for the ESDM–SMTJ framework is to capture both a relatively stable “fingerprint” component and a fast content component of neural activity in a unified formalism. We briefly outline how BCI/EEG signals can be embedded into the semantic state and influence the entropic gate.

Let

denote a feature vector extracted from multichannel EEG during a given trial. The components of

z may include, for example: band-limited power in

ranges, phase-locking values (PLV) or imaginary coherence (ImCoh) between electrode pairs, and common spatial pattern (CSP) projections. We assume a learned mapping

which embeds EEG features into the semantic state space. Given an incoming EEG sample, we set

thereby defining the initial condition for the trajectory

when processing a symbolic expression

e.

In a more structured variant,

can be factored as

where

represents a slow-varying identity subspace (subject fingerprint),

a fast content subspace, and

the layer index. The mapping

can then be decomposed as

with

encoding subject-specific connectivity or spectral patterns and

encoding task-related content at the onset of processing.

4.5. BCI-Modulated Entropic Gate and Authentication

EEG-derived information can also modulate the entropic gate itself. For instance, in an authentication scenario one may wish to favour trajectories consistent with a stored identity fingerprint and penalize those that deviate from it.

Let

be the identity component inferred from the current EEG features and define a dissimilarity measure

in the identity subspace. This quantity can be incorporated into the entropic gate either by adjusting the effective inverse temperature

,

with

g a decreasing function (e.g.

), or by explicitly penalizing modes whose predicted trajectories are incompatible with the reference identity.

Intuitively, when the EEG fingerprint closely matches the stored identity ( small), the effective is high, making the entropic gate more decisive and stabilizing the usual attractors (e.g. MSTJ–Peano for ). When the fingerprint deviates strongly from the reference, is reduced, the gate becomes more diffuse or biased towards a special “reject” mode, and the system is less likely to produce confident judgements in the authorized attractors.

From a BCI perspective, this realizes a form of EEG-based authentication within the ESDM–SMTJ framework: the identity component B extracted from EEG not only defines the initial state , but also shapes the entropic gate and thus the accessibility of certain semantic attractors. In particular, one can design SMTJ energy landscapes and decoding schemes such that successful authentication corresponds to the system reliably entering and revealing a specific attractor, while impostor fingerprints produce either high-entropy, unstable trajectories or blind reveals mapped to an explicit “reject” token.

5. Quantum Extension (Q-ESDM)

The ESDM–SMTJ model described so far is fully classical: semantic modes are weighted by real probabilities, and SMTJ p-bit hardware implements a Boltzmann softmax over these modes. In this section we sketch a quantum extension, Q-ESDM, in which semantic modes are represented as basis states of a Hilbert space and the entropic gate is implemented by a Hamiltonian whose spectrum is tied to the expected entropy drop.

Our goal is not to propose a specific physical platform, but to outline how the key ideas of multi-modal semantics, entropic gate and commit/reveal can be lifted to a quantum setting.

5.1. Hilbert Space of Semantic Modes

For each ambiguous operator

with mode set

we introduce a finite-dimensional Hilbert space

with orthonormal basis vectors

labelled by semantic modes. In the classical ESDM–SMTJ model, the state of

o at position

k is described by a probability vector

. In Q-ESDM, the corresponding quantum state is a vector

with complex amplitudes

. The squared moduli

play the role of mode probabilities, but the relative phases carry additional information and enable interference between semantic modes.

The total Hilbert space for an expression

e with occurrences

of ambiguous operators is constructed as a tensor product

where

is an output or “result” register. The classical semantic state

and EEG-derived component

B can be treated as external parameters that control Hamiltonians acting on

, or, in a more elaborate variant, be included in an enlarged Hilbert space that also encodes identity and content.

5.2. Hamiltonian Encoding of Entropic Preferences

In the classical model, the entropic gate at position

k uses the expected entropy drop

to define mode energies

and realizes a softmax over modes via classical Boltzmann sampling. In Q-ESDM, we use the same quantities to define a local

semantic Hamiltonian acting on the mode space at position

k:

Modes that are expected to lead to a greater entropy drop (i.e. clearer judgements) are assigned lower energies.

Starting from an initial superposition, for instance a uniform state

one can implement an entropic gate in at least two canonical ways:

Adiabatic scheme: define a time-dependent Hamiltonian

that interpolates between a simple initial Hamiltonian with known ground state and

in (

26). Under sufficiently slow evolution, the instantaneous state follows a low-energy eigenstate that concentrates amplitude on modes

i with low

, i.e. high

.

Variational scheme: construct a parametrized unitary (e.g. in the style of QAOA) acting on , with layers that alternate between and a mixing Hamiltonian. The parameters can be optimized offline or adapted online to align the final measurement statistics in the basis with the desired distribution over modes.

In both cases, the quantum entropic gate uses the same classical information to shape a Hamiltonian landscape that favours semantically advantageous modes, but it does so through unitary dynamics and interference rather than through classical thermal fluctuations.

5.3. Quantum Expression Dynamics and Commit

At the level of the entire expression, we replace the classical family of maps

by a family of unitaries

with

and

. The global quantum state at internal time

is

where

encodes the initial superpositions over semantic modes and, optionally, over identity and content degrees of freedom.

As in the classical case, we are interested in the behaviour of the induced output statistics over

. Let

be a POVM acting on the result register

(and possibly on parts of

) that models an ideal readout of output tokens. The time-dependent output distribution is then

and we can define a quantum analogue of semantic output entropy, either as a classical Shannon entropy of

or as a von Neumann entropy of an appropriate reduced state.

We say that a quantum

semantic commit has occurred at

when the reduced state of the result register is close to a pure state associated with a particular output: for instance, when its density matrix

satisfies

with

small in trace norm. At that point, even if the full state

remains coherent and entangled with other registers, the statistics of an eventual measurement in the output basis are already nearly fixed.

5.4. Measurement and Blind Reveal in Q-ESDM

The blind reveal mechanism carries over naturally to the quantum extension. At a final time

, the result register is measured in the token basis

, or more generally via the POVM

. The observed token

is a random variable whose distribution is sharply peaked at

if semantic commit has occurred, but which remains underdetermined if the system has failed to converge to a low-entropy regime.

From the external observer’s perspective, the process is operationally similar to the classical SMTJ-based blind reveal: a rich, hidden internal dynamics (now unitary and possibly entangled) culminates in a single discrete outcome that exposes only one branch of an underlying superposition. The distinction lies in the representational power of the quantum state, which can encode coherent superpositions of semantic modes and exploit interference in selecting trajectories.

5.5. Classical ESDM–SMTJ as a Limit

The original ESDM–SMTJ model can be recovered as a restriction or limit of Q-ESDM in which:

All density matrices are constrained to be diagonal in the mode basis , so that only classical probabilities over modes are represented and phase information is discarded.

The semantic Hamiltonians are used only to define Boltzmann weights for classical sampling, rather than to generate unitary evolution.

The dynamics of and of the SMTJ arrays are treated as classical stochastic processes, without maintaining coherence across different semantic trajectories.

In this sense, ESDM–SMTJ can be viewed as the “thermal” or decohered limit of a more general quantum semantic dynamics. The Q-ESDM framework suggests a possible route for embedding entropic semantic computation into future quantum hardware, while the classical SMTJ implementation remains more immediately accessible for near-term experiments and applications to BCI/EEG-based authentication.

A detailed analysis of concrete quantum circuits, noise models and potential algorithmic advantages of Q-ESDM is left for future work. Here we simply note that the core concepts of multi-modal semantics, entropic preference and commit/reveal admit a natural reformulation in the language of quantum states and Hamiltonians.

6. Conclusion and Outlook

We have introduced ESDM–SMTJ, an Entropic Semantic Dynamics Model that couples a high-level semantic state trajectory with a low-level SMTJ-based p-bit substrate. Operators such as “+” are treated as genuinely multi-modal, with the effective mode at each occurrence selected by an entropic gate that favours trajectories expected to reduce output entropy. This preference is realized physically by mapping predicted entropy drops to energy levels in small SMTJ networks, whose Boltzmann statistics implement a softmax over semantic modes.

Internal processing unfolds as a trajectory with a structured, time-varying entropy profile , rather than as an instantaneous jump from premise to conclusion. Peano-consistent judgements (e.g. ) correspond to attractors in the joint semantic–SMTJ dynamics; rare anomalies (e.g. ) arise when the gate operates in a near-indifferent regime with a small entropic margin and an elevated thermal-shock index (as in our C++ demo with , and softmax probabilities , ), so that correlated SMTJ noise can push the entropic softmax to sample the anomalous mode even though the normal mode retains a slight average advantage.

Conceptually, the framework is novel in three ways. First, it internalizes polysemic operators within the state space itself, rather than treating ambiguity as a purely syntactic or external phenomenon. Second, it gives a concrete dynamical account of rumination, insight and stabilization via the entropy profile and the notions of semantic commit and blind reveal. Third, it anchors these ideas in a realistic hardware model (SMTJs) while also admitting a quantum extension (Q-ESDM) in which semantic modes become basis states of a Hamiltonian.

Our main contributions can be summarized as follows:

We formalize a semantic state space with internal time, ambiguous operators and an entropic gate that selects semantic modes based on predicted entropy reduction.

We show how this gate can be implemented in SMTJ-based p-bit hardware by mapping entropy drops to energy levels, so that Boltzmann statistics realize a softmax over modes.

We introduce the notions of semantic commit and blind reveal as a way to separate hidden judgement formation from overt token emission.

We provide a toy arithmetic case study () that illustrates both Peano-consistent attractors and controlled anomalous judgements () arising from mis-tuned parameters.

We outline a quantum extension (Q-ESDM) where semantic modes live in a Hilbert space and the entropic preferences are encoded in a semantic Hamiltonian.

Beyond abstract reasoning, the ESDM–SMTJ framework connects naturally to BCI and cognitive modelling. By embedding EEG-derived feature vectors into the semantic state and allowing the identity component B to modulate the entropic gate, the model can represent both a slow fingerprint-like structure and fast, task-related content. This opens a route to EEG-based authentication schemes in which access to specific semantic attractors (e.g. a stable arithmetical mapping or a particular decision pattern) depends on the match between an incoming neural fingerprint and a stored reference. More broadly, the entropy profile and the commit/reveal mechanism provide a compact language to describe cognitive phenomena such as hesitation, sudden insight and confidence in a way that is directly tied to hardware dynamics.

Compared to quantum annealing platforms such as D-Wave, the ESDM–SMTJ approach trades tunnelling-based search in large Ising landscapes for a more flexible, room-temperature architecture explicitly designed for semantic dynamics. Rather than competing directly on asymptotic optimization power, it offers a complementary direction: implementing structured, entropy-guided semantic computation and cognitive-like trajectories in compact classical hardware, with a clear theoretical pathway to a future quantum version (Q-ESDM).

Several open problems remain for future work:

Expressivity and identifiability. Characterizing which classes of semantic mappings and cognitive processes can be represented in ESDM–SMTJ, and under what conditions the fingerprint and content components are identifiable from behaviour or EEG.

Learning rules. Deriving concrete online or offline learning rules for updating the predictive model of and the embedding from data.

Hardware prototypes. Designing and fabricating small SMTJ arrays that demonstrably implement the entropic gate and the commit/reveal mechanism, and benchmarking them against purely digital implementations.

Comparison with quantum annealing. Analysing systematically when classical ESDM–SMTJ, its quantum extension Q-ESDM and existing quantum annealers differ in performance, robustness and interpretability on semantic and cognitive tasks.

Cognitive validation. Testing whether the predicted entropy profiles and commit times correlate with behavioural measures of hesitation, confidence and error patterns in human subjects.

We hope that ESDM–SMTJ and Q-ESDM can serve as a bridge between formal logic, probabilistic hardware and neurocognitive data, and as a starting point for a broader study of entropic semantic computation in both classical and quantum devices.

6.1. Relation to Prior SMTJ p-Bit BOLTZMANN Machines

Our work is closely related to prior demonstrations of superparamagnetic tunnel junction (sMTJ) based

p-bit hardware, in particular the hardware-aware in situ learning of Kaiser

et al. [

5]. Those systems and ESDM–SMTJ share a common physical substrate, but differ in their objective and abstraction level. Here we briefly highlight the main points of contact and departure.

Common substrate and statistics. Both approaches use sMTJ devices operated in a thermally activated regime as stochastic binary units (p-bits), and exploit their Boltzmann statistics. In Kaiser et al., the p-bits implement the neurons of a fully connected Boltzmann machine, sampling from with . In ESDM–SMTJ, the same physics is used at a different granularity: small p-bit blocks realize softmax choices over a finite set of semantic modes, with energies derived from predicted entropy drops rather than from a fixed Ising cost function.

Learning objective versus semantic dynamics. The focus of Kaiser et al. is hardware-aware in situ learning of a Boltzmann machine: device imperfections and parameter spreads are compensated by an analog learning rule so that the hardware reproduces a target distribution (e.g. the truth table of a full adder). By contrast, ESDM–SMTJ does not aim to approximate an external distribution over bit patterns. Instead, it defines a semantic state trajectory , multi-modal operators and a notion of graded acceptability, and uses sMTJ blocks as entropic gates that steer toward low-entropy semantic attractors.

Energy landscape versus entropy-drop gate. In prior p-bit Boltzmann machines, the energy landscape is specified by synaptic weights and biases; the hardware samples from the corresponding equilibrium distribution, and learning adjusts . In ESDM–SMTJ, energies are not static parameters of a global Ising model. For each occurrence of an ambiguous operator, we compute mode-dependent entropy drops predicted from the semantic model and map them to local energies . The sMTJ block thus implements a softmax over future expected clarity rather than over a fixed cost function, enabling context-dependent semantic mode selection.

Blind reveal and commit semantics. Prior work evaluates hardware quality by comparing sampled bit distributions to a target distribution (e.g. via KL divergence) and does not distinguish between internal computation and exposure of results. ESDM–SMTJ introduces an explicit separation between a hidden semantic commit at internal time (when becomes low and stable) and a later blind reveal implemented by an output sMTJ block decoding to discrete tokens. This commit/reveal view is tailored to modelling symbolic judgements rather than generic sampling.

BCI/EEG and cognitive modelling. To our knowledge, existing sMTJ p-bit machines have not been applied to neural or biometric data. ESDM–SMTJ explicitly embeds EEG-derived feature vectors into the semantic state as a slow-varying fingerprint component B and a fast content component , and uses sMTJ-based gates for identity-dependent authentication and semantic computation. This connects probabilistic spintronic hardware to BCI and cognitive modelling in a way that goes beyond the scope of prior Boltzmann-machine demonstrations.

In summary, ESDM–SMTJ can be viewed as a semantic and neurocognitive layer built on top of the same p-bit physics exploited by earlier sMTJ Boltzmann machines, with entropic mode selection and blind reveal as its central organizing principles rather than pure distribution learning.

References

- Shunsuke Fukami. Spintronics probabilistic computer: Realization of proposals by feynman and hinton using a spintronics device. JSAP Reviews 2025, 2025, 250204.

- Matthew, W. Daniels, Advait Madhavan, Philippe Talatchian, Alice Mizrahi, and Mark D. Stiles. Energy-efficient stochastic computing with superparamagnetic tunnel junctions. Physical Review Applied 2020, 13, 034016. [Google Scholar]

- Baofang Cai, Yihan He, Yue Xin, Zhengping Yuan, Xue Zhang, Zhifeng Zhu, and Gengchiau Liang. Unconventional computing based on magnetic tunnel junction. Applied Physics A 2023, 129, 236.

- Leo Alexander Schnitzspan. Superparamagnetic Tunnel Junctions—True Randomness, Electrical Coupling and Neuromorphic Computing. Ph.d. thesis, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Mainz, Germany, 2023.

- Jan Kaiser, William A. Borders, Kerem Y. Camsari, Shunsuke Fukami, Hideo Ohno, and Supriyo Datta. Hardware-aware in situ learning based on stochastic magnetic tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. Applied 2022, 17, 014016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).