1. Introduction

In many parts of the world, cities have expanded faster than transport infrastructures could reasonably adapt. The increasing density of vehicles, combined with rising mobility expectations, has exposed long-standing issues related not only to congestion but also to road safety and environmental impact. These limitations have pushed researchers to rethink what a “modern transportation system” should look like. Today, the shift is no longer simply toward more vehicles on the road, but toward transport networks that communicate, coordinate, and react. Two technological domains play a central role in this transition: Vehicular Ad-Hoc Networks (VANETs) and the Internet of Things (IoT). When brought together, they offer new ways for vehicles and infrastructure to share information, improve awareness, and support more advanced Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) [

1].

VANETs stem from the broader class of Mobile Ad-Hoc Networks, but they present their own characteristics. Vehicles move at high speed, links appear and disappear rapidly, and many applications, especially those related to safety—require very low latency and reliable communication. Technologies such as IEEE 802.11p/DSRC and C-V2X were developed specifically to cope with these constraints by enabling fast exchanges of safety messages such as collision alerts or hazardous-road notifications [

2,

3]. In parallel, IoT systems have spread across cities and transportation infrastructures. Sensors embedded in traffic lights, weather stations, public equipment, or even carried by pedestrians generate a wide range of contextual data that can complement what vehicles detect on their own [

4].

The combination of these two domains is commonly referred to as the Internet of Vehicles (IoV). In this integrated environment, VANETs provide the communication backbone, while IoT enriches the system with additional perception. The resulting network is more capable of identifying events, predicting risks, and coordinating decisions. Instead of relying only on local sensors, vehicles can benefit from the information coming from the surrounding infrastructure, which offers a broader perspective of road and environmental conditions [

5].

Several advantages arise from this integration:

Safety, for example, can be improved when roadside sensors detect problems—like slippery surfaces or objects on the roadway—that a vehicle might not see in time. These alerts, once shared through VANET communication channels, help approaching drivers or automated systems react earlier as highlighted in recent cooperative ITS studies [

7].

Traffic efficiency also benefits from this synergy. VANETs offer local coordination between nearby vehicles, but IoT deployments allow city-level data collection, enabling better adjustments to traffic lights or dynamic rerouting during congestion [

8].

From an environmental perspective, smoother traffic and better routing reduce emissions. Measurements based on IoT of air quality also contribute to environmental monitoring and policy planning [

6,

9].

Finally, the system opens the door to new services, ranging from predictive maintenance to customized on-the-go applications or usage-based insurance models [

10].

In general, integrating VANETs with IoT forms a foundation for more adaptive and intelligent mobility systems. This evolution is a prerequisite for future transportation networks that must respond to increasing mobility demands while maintaining safety, efficiency, and sustainability.

1.1. Current Surveys and Research Gaps

Several surveys have explored different aspects of VANET–IoT integration. Some provide general overviews of network architectures or application categories [

11,

12]. Others focus more specifically on communication aspects, comparing DSRC to C-V2X or discussing the evolution of V2X connectivity in recent deployments [

13,

14]. Several surveys place emphasis on security and privacy, offering taxonomies of threats and reviewing common mitigation mechanisms [

15,

16]. Beyond communication and security, other works discuss enabling technologies such as Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) and task offloading [

17], or they examine how AI and machine learning contribute to perception and decision-making processes [

18,

19]. More recent contributions have begun to consider additional paradigms, including blockchain-based trust management [

20] and UAV-assisted networking [

21].

Although literature covers many important topics, these surveys often treat them as separate issues. For instance, protocol comparisons may not consider the implications for security overhead, and security-focused analyses rarely discuss the interplay between computational load and edge-offloading constraints. Moreover, surveys published several years ago naturally predate the broader adoption of C-V2X, the introduction of 5G-Advanced features, or the early development of 6G concepts. As a result, some analyses no longer reflect the current direction of research or industry deployment.

To better understand how these works relate to one another, and to emphasize their limitations more clearly, we provide in

Table 1 a comparative summary of several representative surveys. The table highlights their main objectives, the technological layers they examine, and their level of coverage regarding emerging paradigms.

As shown in

Table 1, many surveys remain confined to specific layers or technologies, which underlines the need for a more integrated perspective—one that considers architectural, protocol-level, and system-level issues in combination. This is the approach adopted in the present work.

1.2. Main Contributions

Taking into account the gaps identified above, this survey aims to provide an updated and more comprehensive view of VANET–IoT integration. The main contributions can be summarized as follows:

1. A multi-layer architectural perspective: We examine the interactions between the cloud, the edge, and vehicles, and we discuss how decisions at one layer may influence constraints or performance at another.

2. A protocol comparison across several layers of the communication stack: Rather than concentrating solely on access-layer technologies (DSRC, C-V2X), our review also analyzes application-layer protocols such as MQTT and CoAP and their evolving roles in 5G-Advanced and prospective 6G systems.

3. A cross-analysis of system challenges: Latency, scalability, security, and energy consumption are discussed not as isolated issues but as elements that often interact and impose trade-offs within the system.

4. A forward-looking exploration of emerging paradigms: The survey highlights research directions likely to shape the next decade, including Joint Communication and Sensing (JCAS), digital-twin concepts, collaborative intelligence, and certain early ideas derived from quantum computing.

Together, these contributions provide a clearer picture of how VANET and IoT technologies intersect and where future efforts may be directed.

1.3. Organization of the Survey

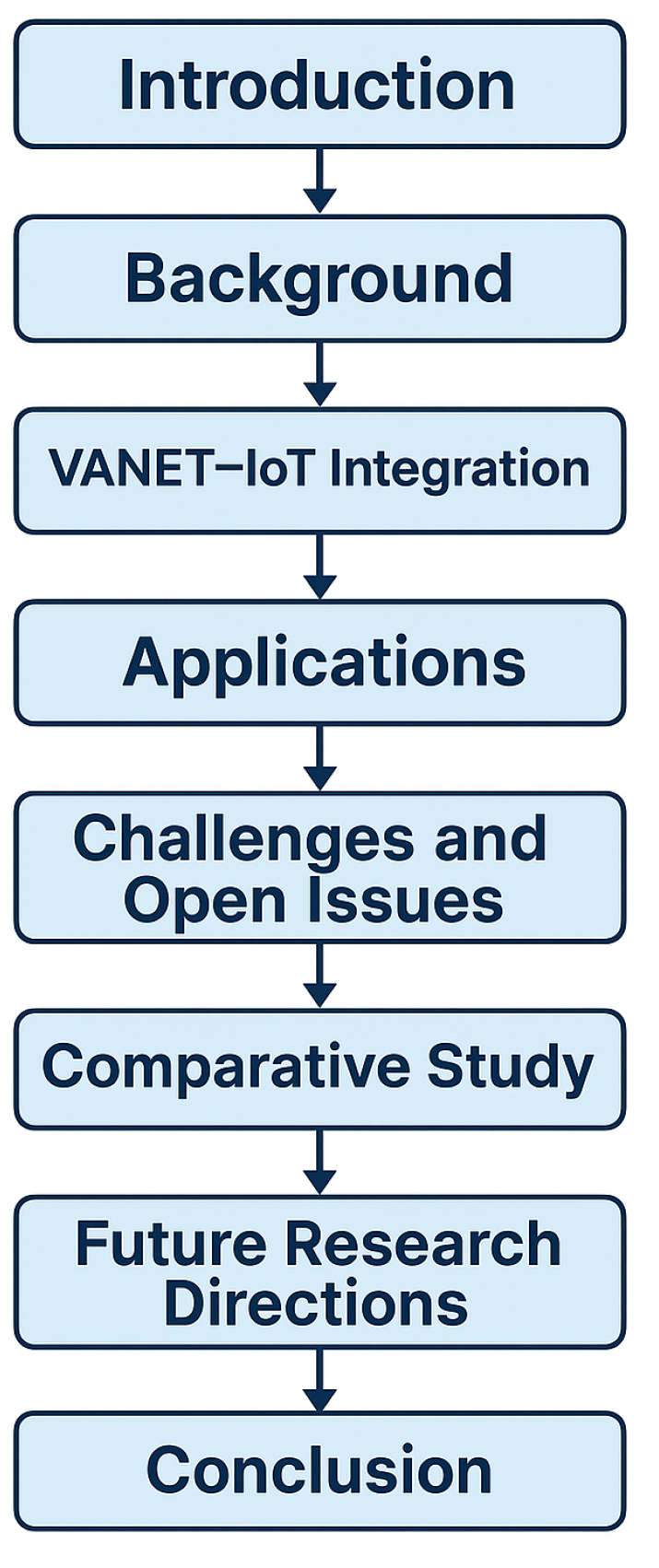

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents background concepts related to VANETs and IoT.

Section 3 discusses enabling technologies and system models, including cloud computing, edge computing, and AI-based approaches.

Section 4 reviews representative applications such as smart-traffic control and emergency-response scenarios.

Section 5 outlines the main challenges associated with VANET–IoT integration.

Section 6 compares different communication protocols and architectural choices.

Section 7 highlights future research directions, including 6G-related developments and beyond.

Section 8 concludes the survey.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the structure of the paper.

2. Background

The integration of Vehicular Ad-Hoc Networks (VANETs) with the Internet of Things (IoT) requires a clear understanding of the communication models, system architectures, and enabling technologies that shape intelligent transportation ecosystems. This section provides an overview of these foundations, starting with the fundamentals of VANET communications, followed by the evolution toward the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) and ending with an examination of communication technologies and distributed computing models that support modern vehicular systems.

2.1. Vehicular Ad-Hoc Networks (VANETs)

VANETs represent a specific class of Mobile Ad-Hoc Networks (MANETs) in which vehicles act as mobile nodes that exchange information dynamically without relying entirely on fixed infrastructure [

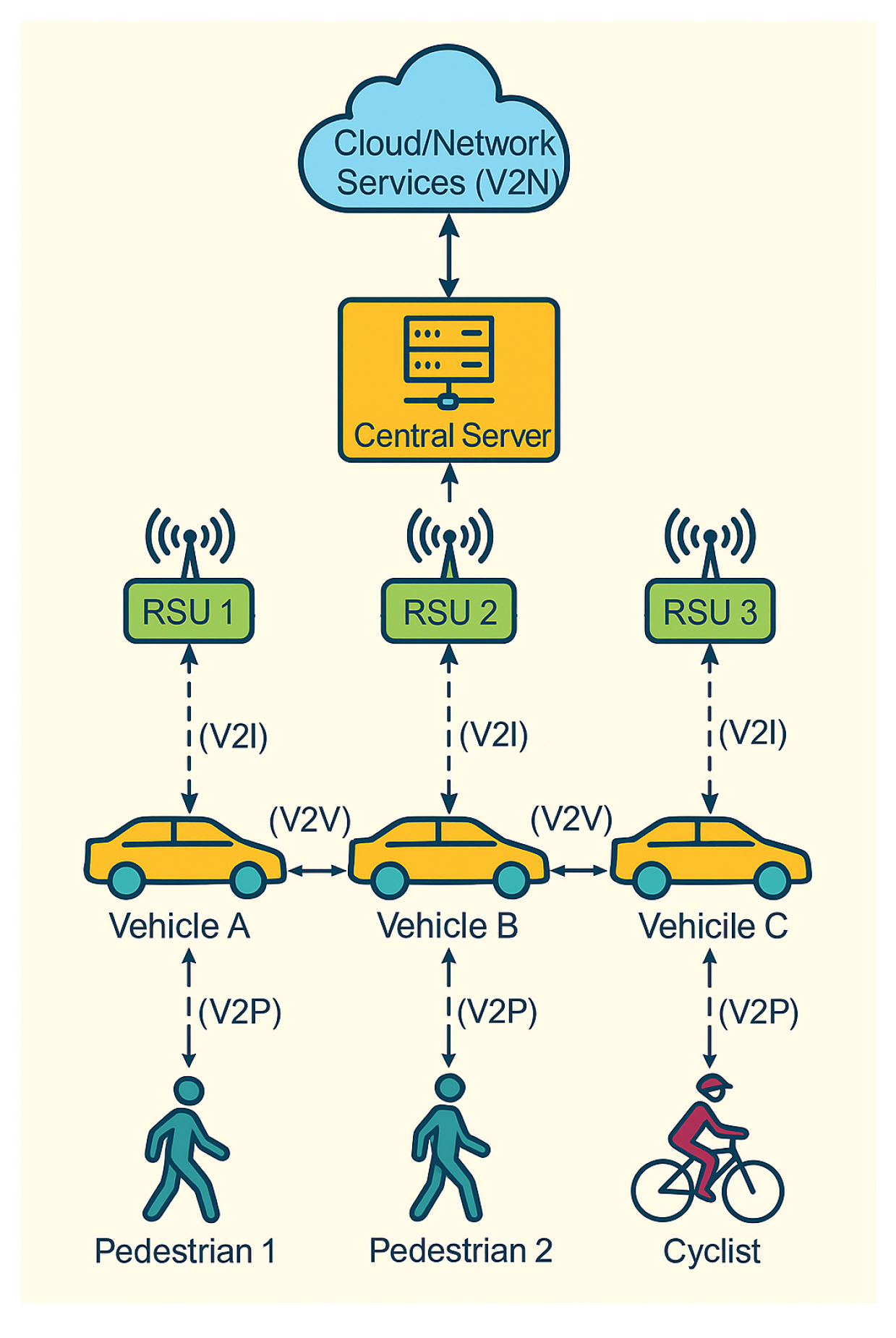

22]. Because of the inherent characteristics of vehicular mobility, high speeds, rapidly changing topology, and strict latency requirements, VANETs require dedicated communication mechanisms and optimized networking protocols. A central component of this ecosystem is Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) communication, which includes interactions between vehicles, infrastructure, pedestrians, and network services.

Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) communication enables the direct exchange of safety messages such as collision warnings or emergency braking information, allowing vehicles to react faster than with sensor perception alone [

23]. Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I) enhances situational awareness through communication with roadside units (RSUs), providing signal phase information, road status alerts, or cooperative traffic strategies [

24]. Vehicle-to-Pedestrian (V2P) interactions rely on personal devices—such as smartphones or wearables—to improve the protection of vulnerable users, particularly in urban settings where visibility is limited [

25]. Vehicle-to-Network (V2N) communication connects vehicles to cloud platforms through cellular infrastructure, enabling large-scale analytics, content distribution, and fleet coordination [

26].

Recent studies on advanced V2X technologies have emphasized the transition toward 5G NR-V2X and its enhanced reliability, latency performance, and integrated sensing capabilities [

13,

14].

Figure 2 illustrates the main V2X communication modes in an intelligent transportation environment. It shows how vehicles interact with RSUs, edge servers, the cloud, vulnerable road users, and other vehicles through V2V, V2I, V2N, and V2P links. The architecture highlights the hierarchical flow of information from OBUs to MEC/Fog servers and cloud services.

Table 2 summarizes the four major V2X communication paradigms—V2V, V2I, V2N, and V2P. For each category, it lists the nodes involved, the underlying communication technologies, typical applications, and core challenges related to latency, reliability, coverage, and deployment constraints.

2.2. From IoT to the Internet of Vehicles (IoV)

IoT technologies have increasingly influenced transportation environments through large-scale sensing, environmental monitoring, and distributed intelligence. Weather stations, traffic cameras, air-quality sensors, and smart parking systems provide contextual data essential for vehicular decision-making [

29]. The emergence of edge-AI modules—compact processors capable of local inference—has transformed many IoT devices into active computational nodes that can preprocess or analyze data before forwarding it [

30]. The heterogeneous and multi-domain nature of IoV deployments builds upon foundational principles from heterogeneous ad-hoc networking, particularly in environments where vehicles, IoT nodes, and RSUs dynamically form distributed topologies [

27].

Building on the interaction between VANETs and IoT devices, the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) extends the vehicular ecosystem into a multi-layer cyber–physical–social system. IoV integrates sensing, networking, cloud services, and human participation to support more informed and efficient decision-making processes [

31].

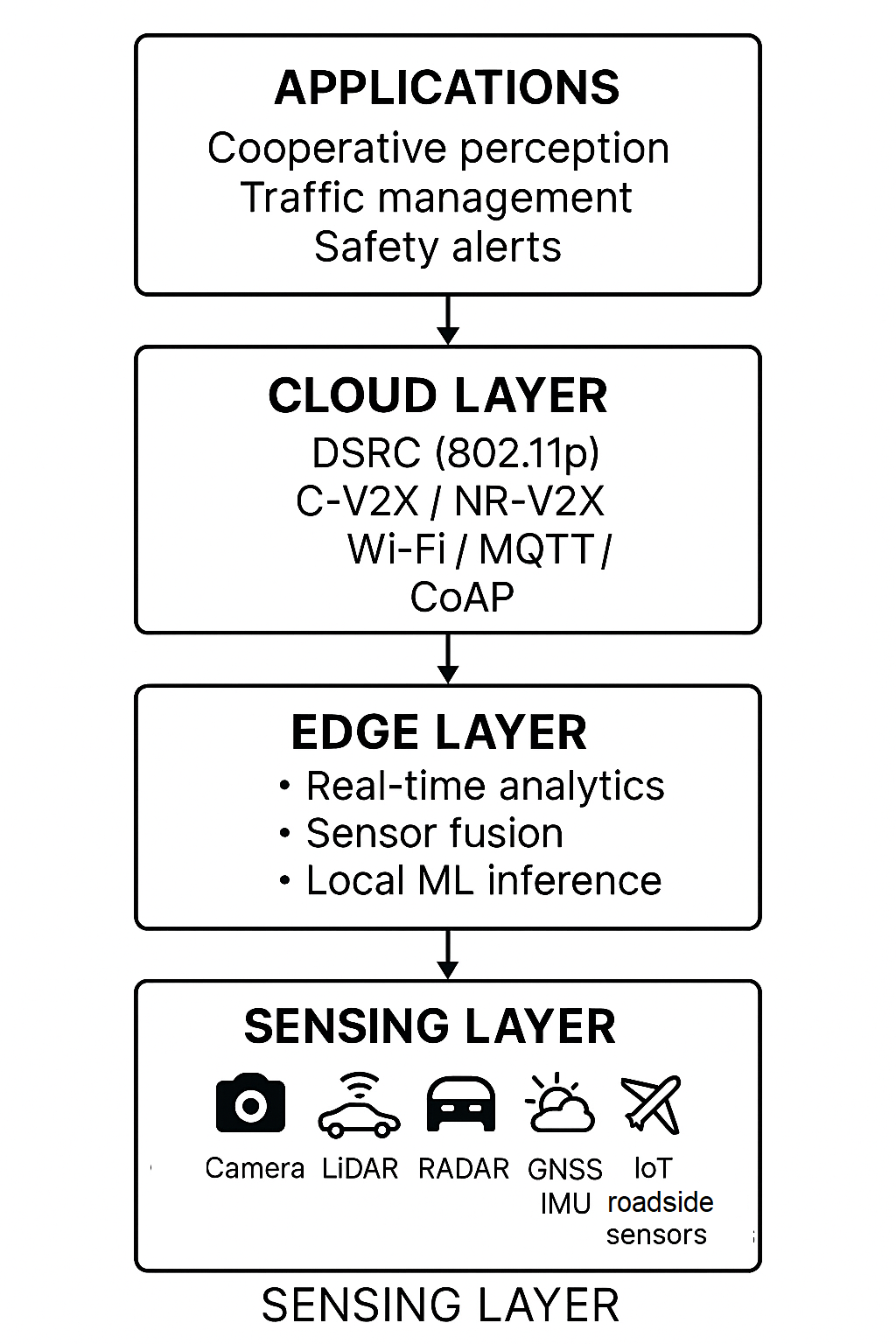

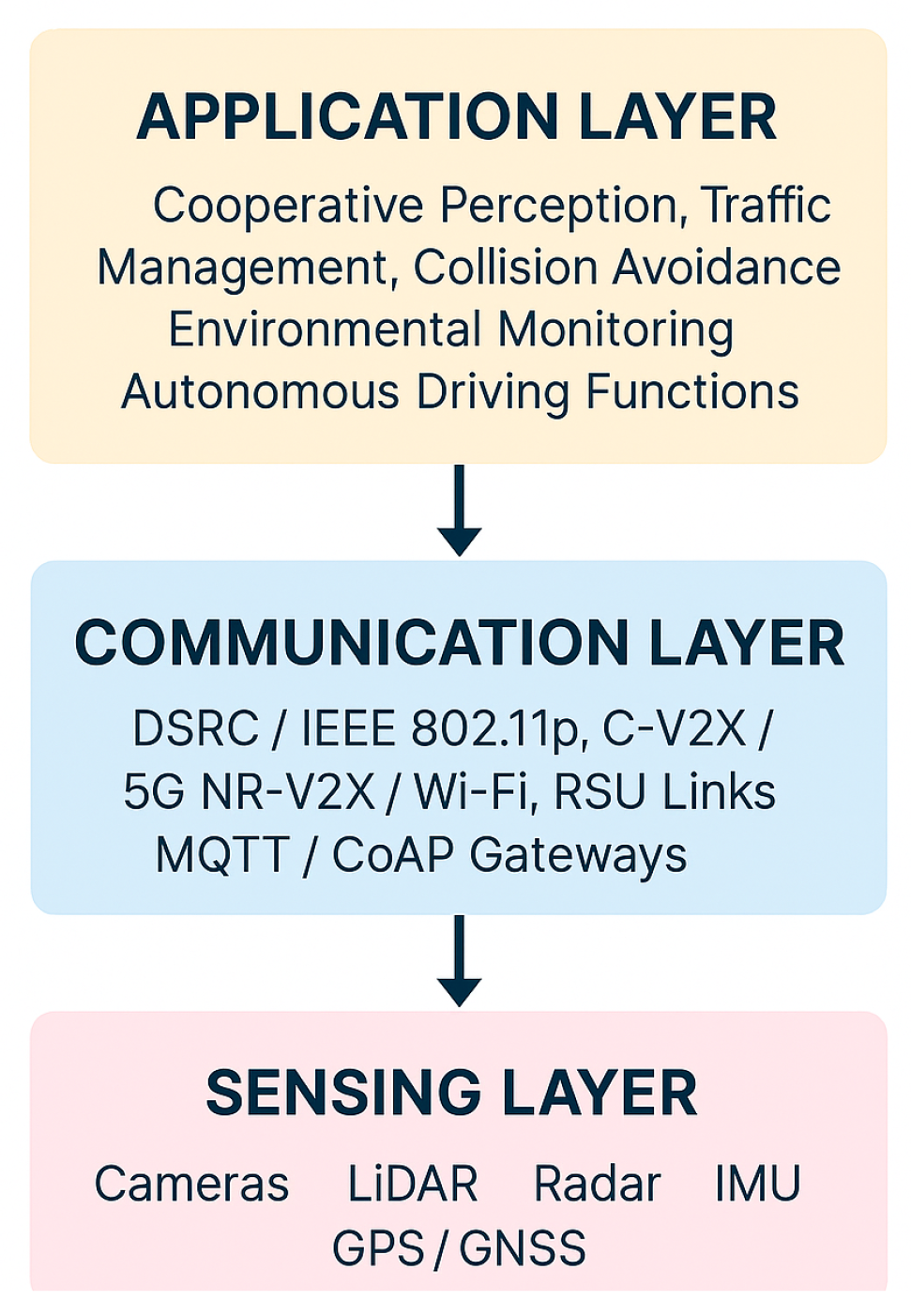

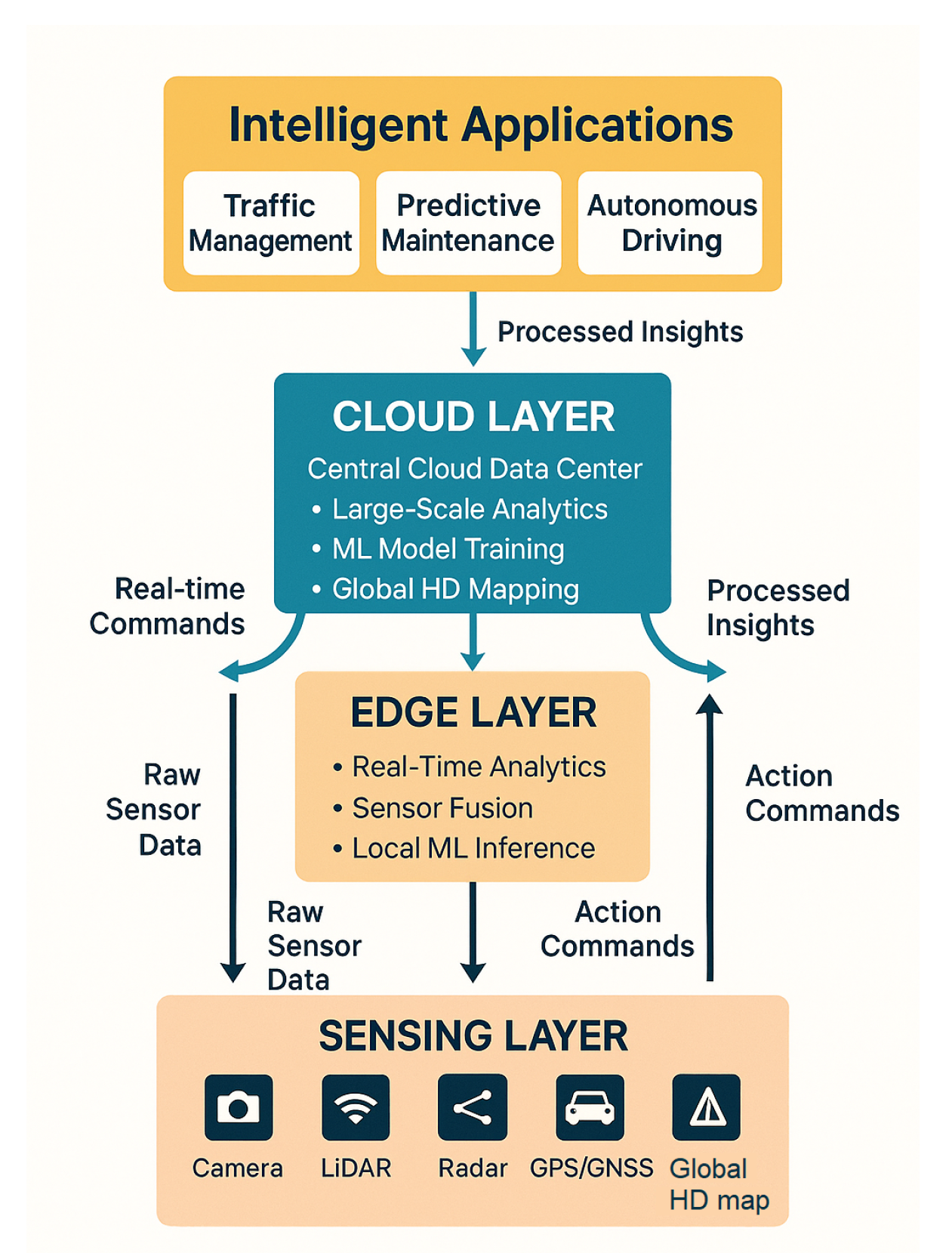

A typical IoV model includes three interconnected layers. The sensing layer collects raw information from vehicle-mounted LiDAR, radar, cameras, and IMUs, as well as from IoT-enabled roadside devices. The communication layer coordinates information exchange among vehicles, RSUs, and pedestrian devices using technologies such as DSRC, C-V2X, Wi-Fi, and cellular networks. The application layer supports tasks such as traffic prediction, cooperative perception, emergency response, and eco-routing [

32]. Recent work emphasizes the importance of cross-layer optimization, showing that communication, sensing, and computing performance are tightly coupled [

33].

Figure 3 illustrates the three-layer architecture commonly used in IoV systems. The sensing layer incorporates vehicle-mounted sensors such as cameras, LiDAR, radar, IMU, and GNSS, which generate raw environmental data. The communication layer enables data exchange through technologies such as DSRC, C-V2X, Wi-Fi, RSU links, and IoT protocols like MQTT and CoAP. The application layer supports higher-level intelligent services including cooperative perception, traffic management, collision avoidance, environmental monitoring, and autonomous driving.

Modern IoV systems rely on a diverse set of sensing technologies deployed both on vehicles and in the environment. Cameras provide rich visual context for lane detection and semantic reasoning, whereas LiDAR offers precise depth estimation through 3D point clouds. Radar contributes robust velocity and distance measurements under adverse weather conditions, and IMUs ensure short-term motion estimation. Roadside IoT devices complement vehicular sensing by monitoring weather, road surface conditions, and pedestrian movement.

Table 3 lists the principal sensor families used in IoV systems, including cameras, LiDAR, RADAR, GNSS, IMUs, OBD-II/CAN sensors, and V2X communication modules. For each sensor, the table summarizes its primary function, produced data type, and typical IoV applications.

2.3. Communication Technologies in IoV

Communication is essential to cooperative vehicular systems. IEEE 802.11p/DSRC offers low-latency broadcast communication over short ranges but suffers from performance degradation under high-density conditions due to channel contention [

34].

Cellular-V2X (C-V2X), introduced in 3GPP Releases 14–15, provides both direct sidelink communication (PC5) and infrastructure-assisted communication (Uu). It has consistently demonstrated higher reliability, superior range, and better scalability compared to DSRC [

32]. With the introduction of 5G NR-V2X (Releases 16–18), vehicular communication benefits from increased throughput, lower latency, improved spectrum allocation, and explicit support for cooperative perception and joint communication–sensing tasks. Research published between 2022 and 2025 shows that NR-V2X significantly enhances automated platooning, sensor fusion, and real-time coordination across multiple vehicles [

35,

36].

At the application layer, lightweight IoT protocols such as MQTT and CoAP play a growing role in vehicular data dissemination. MQTT is suitable for publish–subscribe communication between RSUs and cloud infrastructure, whereas CoAP is common in constrained IoT environments [

37]. Autonomous driving systems increasingly rely on middleware frameworks such as DDS or gRPC to support low-latency, structured communication pipelines [

38].

Table 4 compares DSRC (IEEE 802.11p/1609) and C-V2X (LTE-V2X and NR-V2X) across key dimensions such as standardization, radio access methods, latency, reliability, mobility support, and suitability for cooperative and automated driving scenarios.

2.4. Distributed Computing: Cloud–Edge–Vehicle Continuum

The massive volume of data generated by connected vehicles and IoT systems requires flexible and distributed computational models. Cloud computing supports large-scale analytics, long-term storage, and centralized learning processes but is limited by communication delays that make it unsuitable for time-sensitive safety applications [

39].

Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) reduces these delays by deploying computing resources closer to vehicles, typically at RSUs or cellular base stations. MEC servers can process data streams, perform multi-vehicle perception fusion, and execute offloaded tasks at low latency [

40]. Recent studies (2022–2025) demonstrate that MEC-enhanced cooperative perception improves detection accuracy and reduces redundant onboard computation [

41].

In-vehicle computing has also evolved significantly with the introduction of automotive-grade AI accelerators capable of running deep neural networks for perception, prediction, and planning tasks. Platforms released between 2023 and 2025, such as NVIDIA Orin or Qualcomm Ride, enable real-time processing of multi-sensor data directly within the vehicle [

42].

3. VANET and IoT Integration

The convergence of VANET and IoT technologies is widely recognized as a key driver of next-generation intelligent transportation systems. While VANETs provide low-latency communication among vehicles and infrastructure, the IoT expands the sensing, contextual awareness, and computation capabilities of the environment. When combined, they form an extended Internet of Vehicles (IoV) ecosystem capable of supporting advanced mobility services, cooperative perception, predictive decision-making, and distributed intelligence.

Current research highlights that VANET–IoT integration does not follow a single architectural blueprint. Instead, several complementary models coexist, each designed to address specific challenges such as latency reduction, computational scalability, bandwidth optimization, and trust management. The following subsections summarize the primary integration paradigms reported in contemporary literature and outline their benefits and limitations.

3.1. Cloud-Based VANET–IoT Integration

Cloud-centric architectures remain foundational in large-scale data processing for transportation systems. Data generated by vehicles, RSUs, IoT sensors, and traffic monitoring devices is typically aggregated in remote cloud platforms with virtually unlimited computational and storage capabilities. Such architectures are effective for city-wide analytics, historical modeling, and large-scale AI training, particularly when the timing constraints are not strict [

43].

Vehicles and IoT nodes forward data through RSUs or cellular networks (4G/5G) into cloud infrastructures such as AWS, Azure, or private clouds. These platforms use big-data engines (e.g., Hadoop, Spark) to process terabyte-scale datasets, enabling applications such as long-term traffic pattern analysis, anomaly detection, and predictive modeling. Typical cloud-based applications include:

Predictive Traffic Modeling: Long-horizon forecasting to anticipate congestion patterns and adapt traffic light programming across the city [

44].

Fleet and Logistics Management: Real-time vehicle health monitoring, route optimization, and fuel usage analysis for large corporate fleets [

45].

High-Definition (HD) Map Creation: Cloud servers consolidate sensor data from numerous vehicles to generate updated HD maps used by autonomous driving systems [

46].

Despite their strengths, cloud-based models face two major limitations:

The first: the delay caused by long uplink/downlink transfers makes them unsuitable for safety-critical tasks requiring millisecond-level responses.

The second: continuous upload of raw sensor data (e.g., LiDAR or video) is bandwidth-intensive and costly.

Recent research emphasizes hybrid cloud-edge designs that keep high-level model training in the cloud while pushing latency-critical inference to the edge. Gu et al. [

47] highlight that the cloud is increasingly used to train large-scale DRL models, which are later deployed at the edge for fast inference. Similar findings are reported by Zhang et al. [

48] and Karimi et al. [

49], who observe a shift toward transmitting processed metadata instead of raw sensor streams to reduce bandwidth pressure. Chougule et al. [

50] extend this perspective to EV networks, suggesting the use of cloud-based digital twins to optimize large-scale charging and grid balancing scenarios.

In summary, the cloud excels in macro-level analytics, policy planning, and model training, while its limitations in latency and bandwidth make cloud-only solutions insufficient for real-time systems.

3.2. Edge/Fog-Based VANET–IoT Integration

Edge and Fog architectures aim to overcome the latency and bandwidth limitations of cloud-centric systems by distributing computation closer to vehicles. Processing tasks are moved to RSUs, base-station MEC servers, or clusters of nearby vehicles acting as fog nodes [

67]. Several surveys on vehicular edge computing, including the study in [

28], emphasize the crucial role of RSU-level processing for achieving low-latency and bandwidth-efficient VANET–IoT applications.

In this paradigm, local edge servers process sensor inputs, cooperative events, and safety messages in real time, avoiding the round-trip delays associated with cloud offloading. Typical edge-assisted applications include:

Real-time Collision Avoidance: Edge processors aggregate data from multiple vehicles approaching an intersection and predict collision risks within milliseconds [

51].

Computational Offloading. MEC servers execute heavy modules such as trajectory planning or multi-sensor fusion for autonomous vehicles, reducing onboard computing load [

52].

Low-Latency Caching: Local distribution of frequently accessed content (e.g., map updates or software patches), enabling rapid delivery within specific road segments [

53].

Although edge nodes improve latency, they have limited computing capacity compared to cloud servers. Their effectiveness depends on deployment density, mobility-aware service placement, and resource allocation strategies. The cost and operational complexity of deploying MEC infrastructure across cities also remain challenges.

Recent surveys emphasize the importance of intelligent task scheduling and resource management. Guo et al. [

47] compare proactive and reactive offloading mechanisms and show that predictive, AI-driven strategies significantly reduce latency, albeit at the cost of possible misallocation when prediction errors occur. Habibi et al. [

54] examine vehicular fog architectures and conclude that hybrid coordination schemes—combining centralized RSU-based orchestration with decentralized vehicle cooperation—offer the best compromise between reliability and flexibility.

Figure 4 illustrates the layered computation model used in IoV systems. The vehicle layer generates raw sensor data through on-board sensors such as cameras, LiDAR, radar, IMU, and GNSS. The edge layer, typically implemented through RSUs or MEC nodes, performs real-time analytics, sensor fusion, short-term prediction, and local decision support. The cloud layer provides large-scale processing for long-term learning, traffic forecasting, high-definition map updates, and global coordination. Processed insights flow back toward the edge and vehicle layers to support intelligent applications such as cooperative perception, collision avoidance, and traffic management.

The literature suggests that while edge computing is indispensable for low-latency services, its performance depends heavily on predictive intelligence, topology dynamics, and the accuracy of mobility-aware orchestration. AI-driven resource management is therefore emerging as a critical research direction.

3.3. AI/ML for VANET–IoT Systems

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) play a central role in enabling perception, prediction, and decision-making across cloud, edge, and vehicle layers. Lightweight models deployed at the edge or inside the vehicle support real-time inference, while more complex models are trained in the cloud.

Edge-based Inference: Deep learning models such as YOLO and SqueezeNet can process camera streams to detect and classify objects in real time [

55]. Other ML models perform anomaly detection to identify unsafe driving patterns, unusual traffic behavior, or road hazards [

56].

Cloud-based Training: The cloud provides the large-scale computation required to train predictive analytics models capable of forecasting congestion, estimating travel times, and identifying accident-prone areas [

57].

A significant trend is the rise of Federated Learning (FL), which keeps raw data local while sharing only model updates. Mo et al. [

58] review FL frameworks for IoV and highlight challenges such as communication overhead, non-IID data, and vulnerability to model poisoning.

Another major research theme concerns model compression to support efficient edge inference. Gu et al. [

47] compare pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation techniques, emphasizing the trade-off between accuracy and computational load. Alqubaysi et al. [59] show that FL can match centralized learning accuracy while preserving privacy but often requires more communication rounds.

Overall, AI integration in VANET–IoT systems involves balancing privacy, latency, model accuracy, and communication efficiency. No approach is universally optimal; the most suitable solution depends on application constraints.

3.4. Security and Privacy

The open and wireless nature of VANET–IoT systems exposes them to multiple threats, making security and privacy core design requirements. Cryptographic primitives such as AES and ECDSA are fundamental for message confidentiality, integrity, and authentication. In parallel, blockchain technologies are increasingly explored for trust management and tamper-proof record keeping [

60,

61,

62]. Pseudonymization is another widely used method, allowing vehicles to frequently change identifiers to prevent long-term tracking [

63].

Recent research compares classical cryptographic solutions with emerging blockchain-based mechanisms. Mohammed et al. [

64] analyze consensus protocols for vehicular fog systems and conclude that traditional Proof-of-Work is impractical due to energy and latency constraints, whereas lightweight schemes such as PBFT, PoS, or dPoS provide more suitable alternatives. Choi et al. [

65] discuss limitations of PKI-based V2X authentication, particularly the delays in certificate revocation, and highlight that blockchain can enable faster CRL distribution. Boualouache et al. [

66] survey pseudonym management schemes and observe that hybrid centralized-decentralized approaches—potentially combined with blockchain—achieve the best balance between privacy and performance.

In summary, blockchain is a promising complement to cryptographic mechanisms, particularly for transparent certificate management, but must be integrated carefully to avoid excessive overhead.

3.5. Comparative Summary of VANET–IoT Integration Models

Table 5 summarizes key contributions from recent VANET–IoT integration studies [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

60,

61,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

69], highlighting the diversity of architectures, objectives, and technological enablers. This table compares representative works on VANET–IoT integration across four major categories: cloud-based architectures, edge/fog computing, AI/ML-driven frameworks, and security/privacy solutions. For each category, it summarizes the main objectives, strengths, and remaining limitations identified in the literature. The comparison highlights the trade-offs between latency, scalability, security, and computational demands, helping identify research gaps addressed in subsequent sections.

4. Applications of VANET–IoT Integration

The integration of VANET and IoT technologies has enabled a wide spectrum of applications that support safer, more efficient, and more sustainable mobility systems. By combining vehicular communication networks with large-scale sensing, distributed computation, and intelligent decision-making, emerging transportation infrastructures can optimize traffic, enable cooperative autonomous driving, improve emergency response, and enhance environmental monitoring. This section presents the major application domains structured around the most relevant categories observed in recent research.

4.1. Traffic Optimization and Intelligent Traffic Management

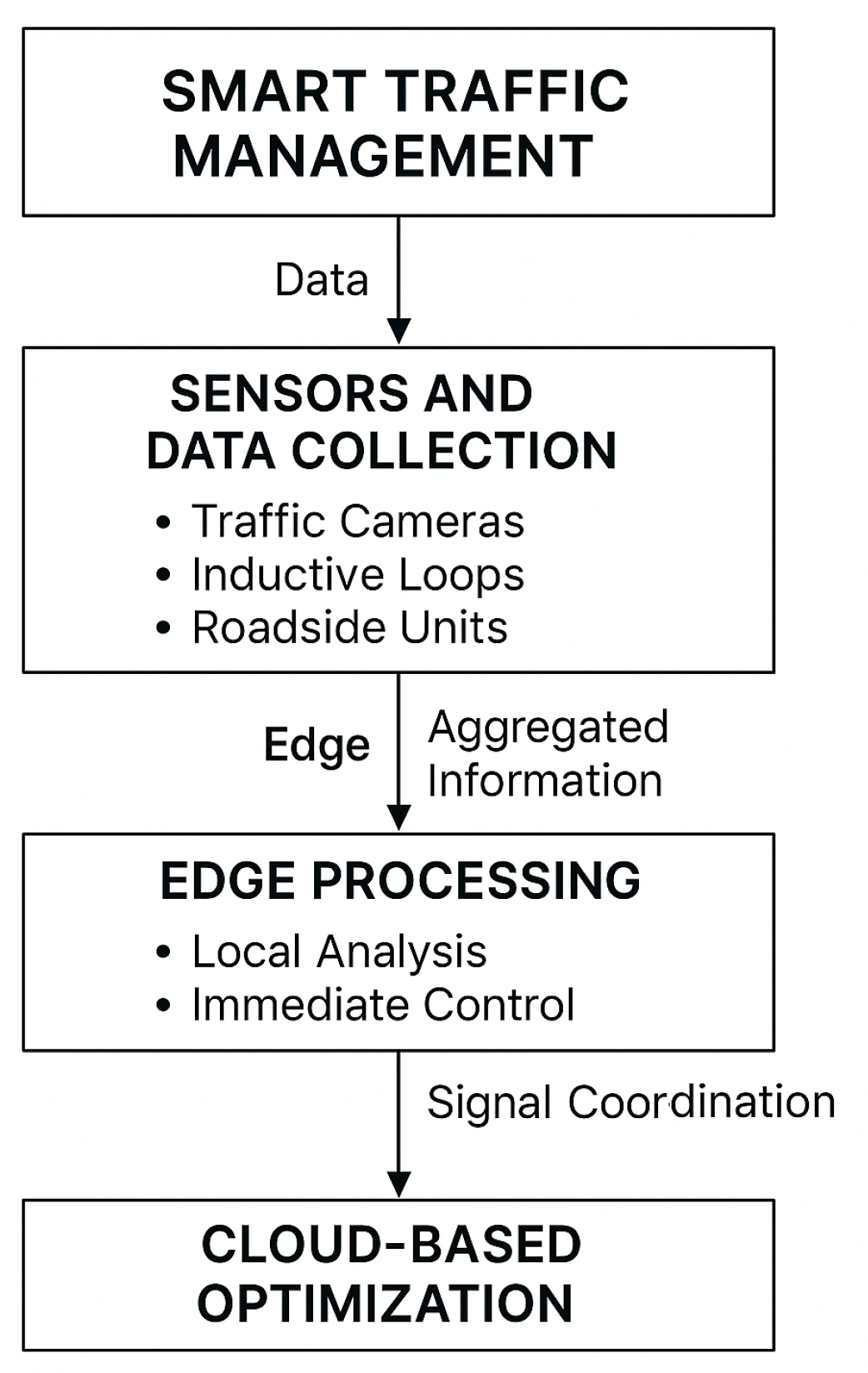

Traffic optimization is one of the most mature and widely studied application areas of VANET–IoT integration. By aggregating data from vehicles, roadside IoT sensors, cameras, and environmental monitoring devices, transportation authorities can generate situational awareness at both local and large scales. Intelligent intersections, adaptive signal control, and congestion-aware routing algorithms rely heavily on this integrated information flow.

Real-time data collected from connected vehicles allow prediction of congestion build-up several minutes before it becomes critical [

68]. IoT-enhanced RSUs equipped with traffic cameras, inductive loops, or radar sensors supplement this data by offering precise measurements of lane occupancy, queue length, and turning flows. Predictive models built on this multimodal dataset can adjust signal timings to minimize delays, prioritize public transport, or mitigate bottlenecks [

69].

Several studies have demonstrated the benefits of cooperative routing strategies in which vehicles exchange local observations through V2V communication while RSUs provide regional traffic information via V2I links. These hybrid approaches improve traffic stability and reduce stop-and-go oscillations, especially in dense urban areas [70]. Cloud platforms play a complementary role by performing long-term analytics and identifying recurring congestion hotspots, enabling strategic planning of infrastructure improvements [

71].

Recent work has further explored decentralized and edge-assisted traffic management. MEC servers positioned at intersections perform local computations—such as real-time vehicle counting, trajectory clustering, or anomaly detection—allowing rapid responses under rapidly changing traffic conditions [

72].

Figure 5 shows how sensing data from connected vehicles and roadside IoT devices flows to edge and cloud layers to enable adaptive traffic management. Vehicles report position, speed, and events through V2X links, while RSUs perform local analytics. Processed data is combined in the cloud to generate large-scale traffic predictions and optimization policies. Updated control strategies are then disseminated back to intersections and vehicles.

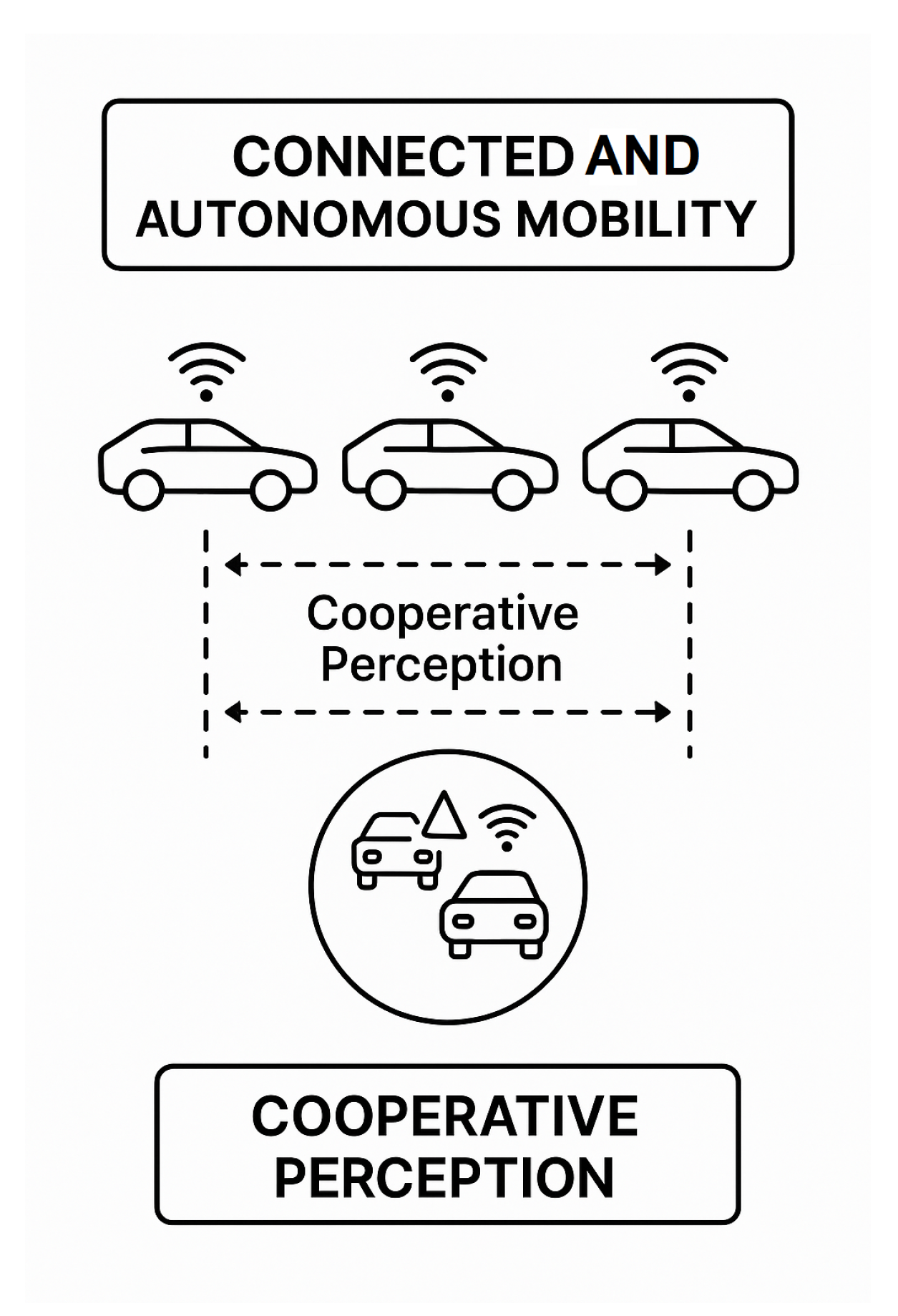

4.2. Connected and Autonomous Mobility (CAV Applications)

Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CAVs) rely on continuous data exchange to enhance situational awareness and improve driving decisions. While onboard sensors provide high-resolution perception, their effectiveness remains limited by occlusions, adverse weather, and field-of-view constraints. Integrating VANET communication with IoT-based infrastructure significantly strengthens perception and decision-making for autonomous systems.

Cooperative Perception (CP): CP systems share object detections, trajectories, and free-space information among vehicles and roadside sensing units to remove blind spots and extend perception range. This cooperative data fusion drastically reduces collision risks in urban areas with heavy occlusions [

73].

Platooning and Cooperative Driving: CAV platoons require stable low-latency communication to maintain tight inter-vehicle spacing. V2V links provide real-time updates on acceleration, braking, and trajectory adjustments, while IoT-enhanced RSUs monitor lane conditions and merging events [

74].

HD Map Maintenance and Localization: Cloud platforms aggregate perception data from multiple vehicles to generate near-real-time HD map updates. Edge servers simultaneously provide positioning corrections and lane-level localization cues using GNSS sensors, LiDAR landmarks, and IoT-based roadside beacons [

75].

Edge-Assisted Autonomy. MEC nodes support compute-intensive tasks such as global path planning, image-based object recognition, and cross-vehicle sensor fusion while maintaining acceptable response times for safety-critical decisions [

76].

These capabilities create a symbiotic relationship in which IoT infrastructure improves automated driving reliability, while connected vehicles enrich the collective knowledge base.

Figure 6 illustrates how connected autonomous vehicles share perception information through V2V communication. Vehicles exchange sensor data, hazard alerts, and situational context, enabling a broader and more reliable perception field than what a single vehicle can achieve independently.

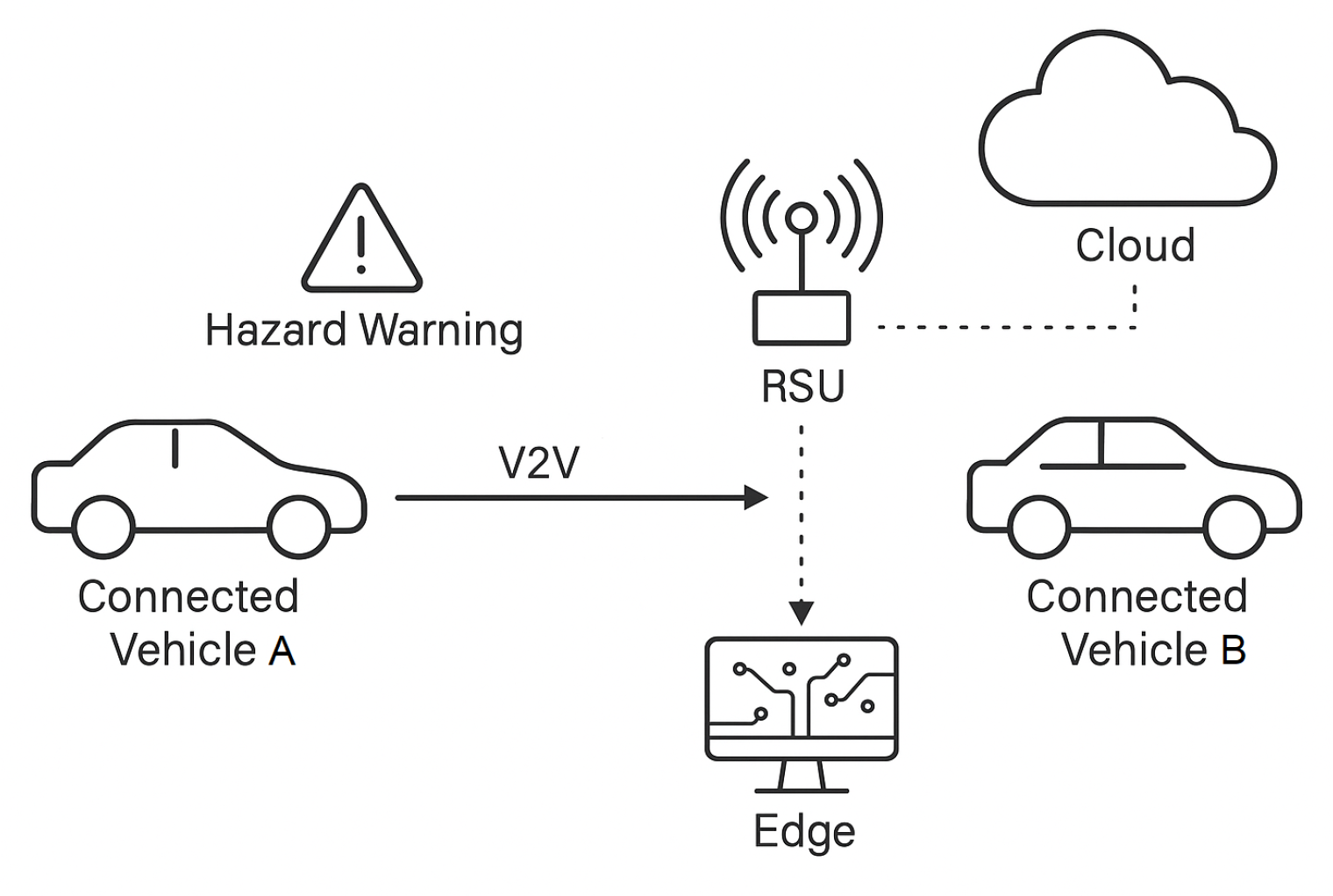

4.3. Cooperative Safety and Emergency Response

Safety applications constitute one of the most critical motivations for integrating VANET and IoT technologies. By leveraging real-time sensing, low-latency communications, and distributed analytics, the network can rapidly detect hazardous situations and disseminate alerts to nearby vehicles.

Figure 7 illustrates how local vehicle sensors, roadside IoT devices, and edge servers collaborate to provide a unified perception view. Vehicles detect objects using onboard cameras, radar, and LiDAR, while RSUs supplement missing information. Edge servers fuse multi-vehicle data streams, support trajectory prediction, and assist autonomous driving modules with low-latency inference.

Hazard and Incident Detection: Vehicles can identify sudden braking, slippery surfaces, lane obstructions, or abnormal driving patterns using onboard sensors and V2V communication. IoT-enabled roadside sensors provide complementary data—such as weather changes, smoke detection, or structural failures—leading to earlier hazard identification [

77].

Emergency Vehicle Coordination: IoT-enhanced RSUs coordinate emergency vehicle routes by broadcasting lane-clearing instructions and signal preemption commands. V2X communication ensures that ambulances, fire trucks, and police vehicles receive right-of-way support through real-time traffic signal adjustments [

78].

Collision Avoidance: Cooperative collision avoidance systems integrate V2V alerts, road friction data, and contextual information from IoT sensors to improve braking decisions and lane-change safety [

79].

Post-Incident Management: Once an incident is detected, cloud-based systems generate rerouting instructions, notify emergency responders, and update long-term safety statistics for infrastructure planning [

80].

Table 6 provides a structured comparison of major safety and emergency response applications supported by VANET–IoT integration, as identified in representative works [

57,

76,

80,

81,

82,

83,

86]. For each safety challenge, it summarizes the enabling technologies, communication mechanisms, and main benefits, along with representative references from recent literature. The applications highlight the crucial role of cooperative sensing, real-time V2X communication, and IoT-enhanced analytics in improving road safety and emergency response efficiency.

4.4. Environmental Monitoring and Urban Sensing

Environmental monitoring has become an essential component of modern smart cities. The combination of vehicular sensors and stationery IoT nodes enables fine-grained assessment of environmental conditions across large areas.

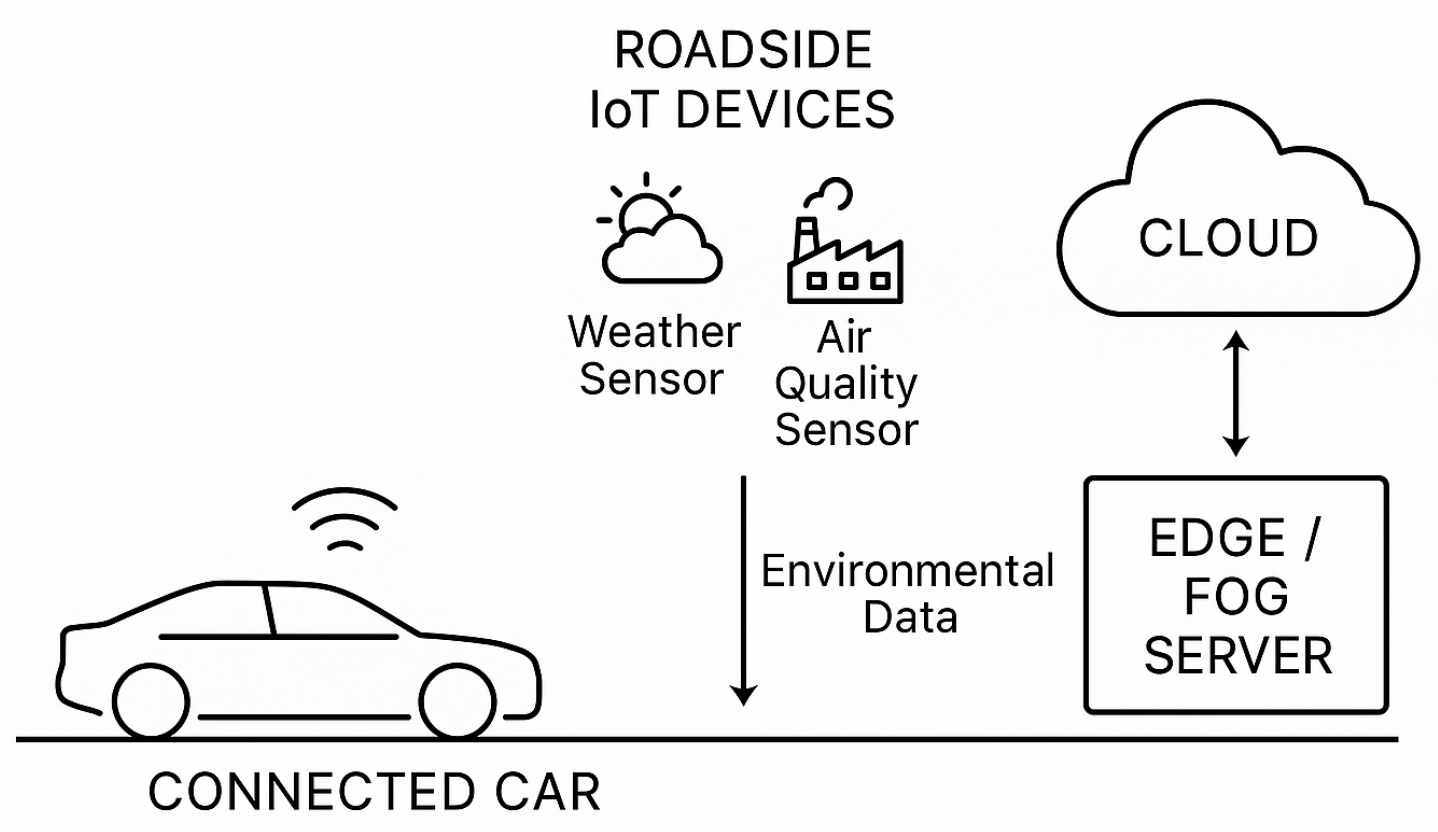

Figure 8 illustrates how connected vehicles and roadside IoT sensors collect environmental data such as weather conditions and air quality. The data is forwarded to edge/fog servers for real-time processing and then to the cloud for large-scale analytics and long-term environmental insights.

Air Quality Monitoring. Vehicles equipped with low-cost gas sensors help monitor pollutants such as

,

, and particulate matter (PM2.5). Their mobility allows dynamic mapping of pollution variations throughout the day [

81].

Weather and Microclimate Monitoring. IoT stations measure temperature, humidity, rainfall, wind speed, and road surface conditions. This data supports route recommendations, road maintenance, and weather hazard prediction [

82].

Road Surface Condition Assessment. Accelerometers, IMUs, and vibration sensors embedded in vehicles can detect potholes, cracks, or icy surfaces. RSUs collect these reports and notify maintenance teams or broadcast warnings [

83].

Noise Mapping and Urban Planning. IoT microphones distributed in dense regions help build noise heatmaps, which support urban planning decisions and smart zoning policies [

84].

The integration of IoT and vehicular sensing ensures wide spatial coverage without deploying a prohibitive number of stationary sensors.

Table 7 summarizes key environmental and urban sensing applications supported by VANET–IoT integration, derived from recent studies [

84,

85,

86,

87]. It highlights how mobile vehicle sensors and stationery IoT devices complement each other to provide high-resolution measurements of air quality, weather conditions, road-surface hazards, and urban noise. The table also identifies the underlying communication mechanisms and the main benefits associated with each application domain.

4.5. Discussion

VANET–IoT integration has demonstrated significant benefits across traffic management, autonomous mobility, safety, and environmental monitoring. However, the practical deployment of these applications depends on the reliability of V2X communication, the scalability of edge resources, the robustness of IoT sensors, and the development of secure and privacy-aware mechanisms. The next section discusses the remaining challenges and identifies research directions needed to achieve fully integrated intelligent transportation systems.

5. Challenges and Open Issues

The integration of VANET and IoT technologies promises to transform transportation systems into highly connected, context-aware, and autonomous environments. Despite these advances, several fundamental challenges hinder the large-scale deployment and reliability of such systems. These challenges emerge from the intrinsic characteristics of vehicular networks, including high mobility, dynamic topologies, latency constraints, and heterogeneous device capabilities—as well as from the limitations of IoT infrastructures that contribute sensing and computational support.

Addressing these issues requires coordinated solutions across communication, computation, and security layers. In particular, ensuring robust trust management, scalable resource allocation, seamless interoperability, and energy-efficient operation remain essential for achieving resilient and sustainable Intelligent Transportation Systems.

The following subsections outline the most prominent challenges identified in recent literature and highlight open research directions that must be addressed to realize the full potential of VANET–IoT integration.

5.1. Security and Privacy Challenges

Security and privacy remain fundamental obstacles to the deployment of large-scale VANET–IoT systems. The open wireless medium, the mobility of vehicles, and the heterogeneity of IoT devices create a broad and dynamic attack surface that increases the risk of message forgery, identity manipulation, data tampering, and unauthorized access. Moreover, the strict latency and reliability requirements of safety-critical applications complicate the integration of conventional cybersecurity frameworks. This subsection reviews key threat categories, evaluates existing mitigation mechanisms, and highlights the limitations of current security architectures in vehicular environments.

5.1.1. Threat Landscape

VANET–IoT ecosystems are exposed to several classes of attacks due to their decentralized and highly mobile nature. Message falsification and injection attacks allow adversaries to disseminate forged hazard alerts, leading to traffic disturbances or intentional rerouting. Sybil attacks, in which a malicious node artificially generates multiple identities, distort traffic density estimations and compromise cooperative perception [

85]. Eavesdropping and data interception exploit the broadcast nature of V2V and V2I communications, enabling attackers to monitor vehicle movements or extract sensitive information. Denial-of-Service (DoS) and jamming attacks target the physical or MAC layers, disrupting channel availability and degrading the performance of time-critical applications [

86].

Finally, malware propagation through IoT devices or compromised RSUs can affect both the vehicular subsystem and the surrounding infrastructure.

5.1.2. Limitations of Classical

Cryptographic Mechanisms Public-key cryptography (PKI) is widely adopted to ensure message authentication and integrity in V2X systems. However, its scalability and latency remain significant concerns. Certificate verification and revocation processes can introduce delays incompatible with real-time safety applications [

87]. The reliance on centralized certificate authorities also creates bottlenecks and single points of failure. Lightweight cryptographic schemes have been proposed for constrained IoT devices, but the heterogeneity of devices further complicates unified key management. Cross-domain trust establishment is particularly challenging when vehicles move across regions served by different operators or authorities.

5.1.3. Privacy and Pseudonymity Constraints

Protecting driver privacy is essential, as continuous broadcasts of location and sensor data can reveal sensitive movement patterns. Short-term pseudonyms aim to prevent long-term tracking, but frequent pseudonym changes generate synchronization overhead and require robust revocation strategies. IoT-assisted RSUs can help manage pseudonym updates, yet adversaries equipped with multi-sensor fusion techniques can still correlate vehicular behavior to re-identify users. Ensuring unlinkability while maintaining accountability remains a difficult trade-off [

88].

5.1.4. Blockchain-based Security: Opportunities and Challenges

Blockchain technologies have attracted significant interest due to their auditability and resilience against tampering. Distributed ledgers can record pseudonym updates, certificate revocations, and event reports in a verifiable manner [

89]. Lightweight consensus mechanisms such as PBFT or Delegated Proof-of-Stake have been proposed to reduce computational overhead. However, blockchain introduces its own challenges:

(1) maintaining low latency under high mobility.

(2) ensuring scalability as the ledger grows.

(3) preventing congestion caused by simultaneous event reporting; and

(4) addressing privacy issues arising from transparent records.

Hybrid architectures combining blockchain with edge computing have shown promise but remain at early stages of development.

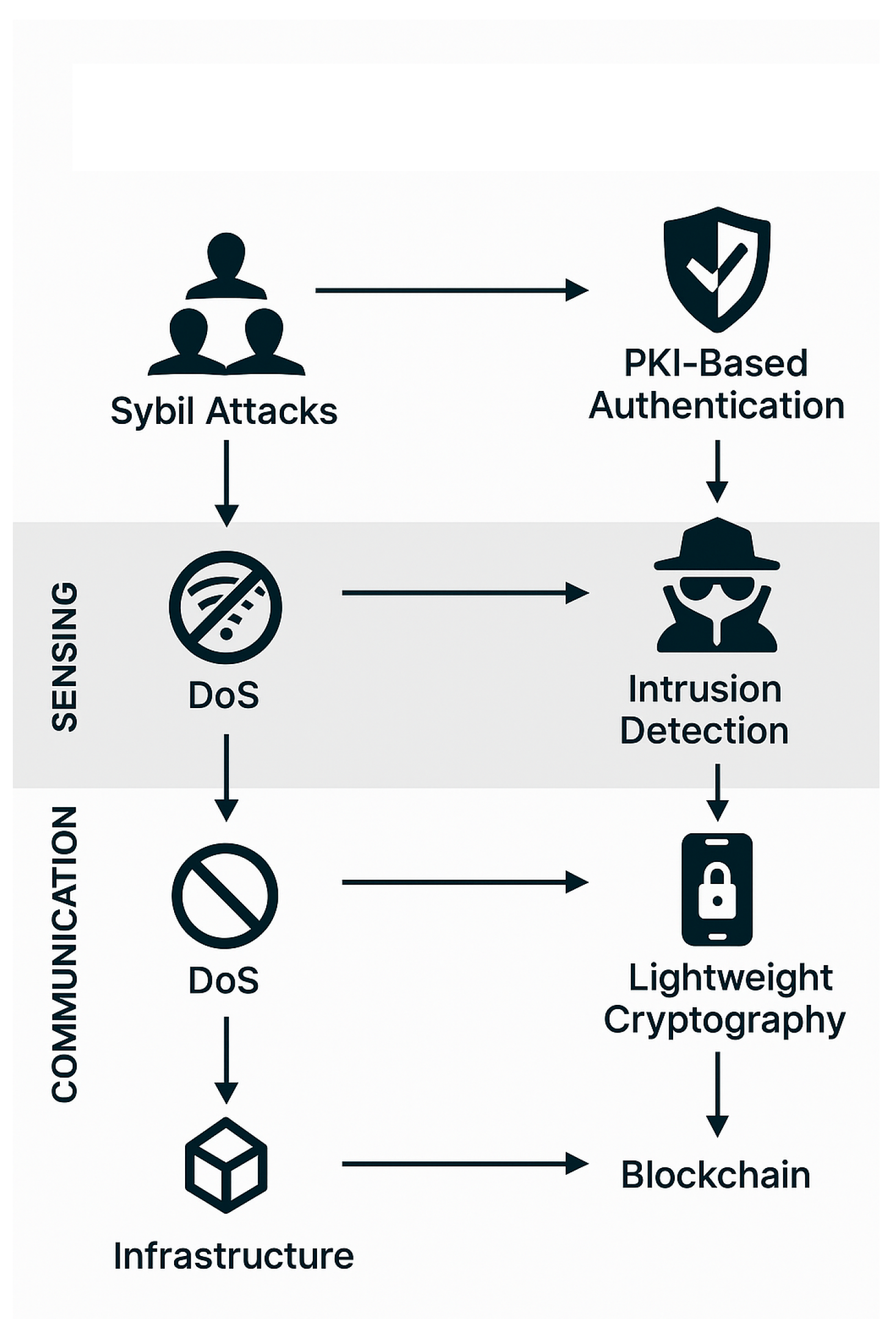

Figure 9 summarizes the principal security threats affecting VANET–IoT systems—including Sybil attacks, message falsification, jamming/DoS, and infrastructure compromise—and maps them to widely adopted defense mechanisms such as PKI-based authentication, intrusion detection systems, lightweight cryptography, and blockchain. The flow highlights the need for multi-layer protection across sensing, communication, and infrastructure tiers.

Table 8 summarizes major security and privacy challenges affecting VANET–IoT integration documented in recent VANET–IoT literature [

105,

106,

107,

108]. It highlights how different classes of attacks exploit the broadcast and distributed nature of V2X communication, and how weaknesses in trust management and privacy preservation impact system reliability.

5.2. Scalability and Mobility Management

Scalability and mobility management represent central challenges in VANET–IoT systems due to the highly dynamic and unpredictable nature of vehicular environments. As vehicle density fluctuates, communication links are frequently established and broken, producing rapid variations in network topology. These conditions significantly affect packet delivery reliability, channel contention, and computing resource allocation at both RSUs and edge servers. Ensuring that the system remains responsive under high density and high mobility is essential for supporting latency-sensitive applications such as cooperative perception and collision avoidance.

5.2.1. Network Congestion and Density Fluctuations

In dense traffic scenarios—such as highways during rush hours or crowded urban intersections, simultaneous transmissions may saturate the wireless channel. High message arrival rates increase the likelihood of packet collisions, leading to degraded reliability and delayed delivery [

90]. Furthermore, beaconing—periodic broadcasting of safety messages—escalates channel load when many vehicles occupy the same region. IoT-enabled RSUs may also become overloaded when processing multiple streams of sensor data from vehicles and environmental sensing devices.

Adaptive congestion control techniques have been proposed to mitigate this problem, including dynamic beaconing, transmit power adaptation, and priority-aware scheduling. However, most approaches require accurate, real-time estimation of traffic density, which remains difficult under rapidly changing mobility conditions.

5.2.2. Dynamic Topology and Link Instability

High-speed mobility causes frequent link disruptions, making routing decisions particularly challenging. Traditional MANET routing protocols struggle to maintain route stability when vehicles travel at high speeds or move rapidly across RSU coverage zones [

91]. IoT devices in the environment—such as cameras or weather stations—can help predict mobility patterns, but their spatial distribution is often sparse or irregular.

Multi-hop V2V routing is especially susceptible to link breaks, while V2I communication depends on the density and placement of RSUs. Maintaining reliable communication under such conditions requires both predictive mobility models and cross-layer optimization strategies that combine sensing, communication, and edge computation.

5.2.3. Edge Resource Overload and Task Offloading Constraints

As more vehicles request cooperative services, edge servers may face resource contention, particularly in regions with high traffic density. Computationally expensive tasks—such as trajectory prediction, sensor fusion, and image processing—can overload MEC servers, causing increased latency. Task offloading strategies must therefore account for available computing power, channel conditions, and vehicle mobility to avoid congestion at the edge [

92].

Several studies propose learning-based approaches to predict future workload and distribute tasks among multiple edge nodes. However, these models require accurate mobility forecasts and sufficient training data, both of which remain difficult to obtain in large-scale deployments.

5.2.4. Multi-Domain Scalability Challenges

VANET–IoT systems operate across multiple domains—communication, sensing, computing, and storage—which scale differently as the number of vehicles and IoT nodes increases. Cloud systems can handle large datasets but suffer from higher delays, while edge nodes offer low latency but limited computing capacity. Achieving a balanced allocation of tasks remains an open research problem.

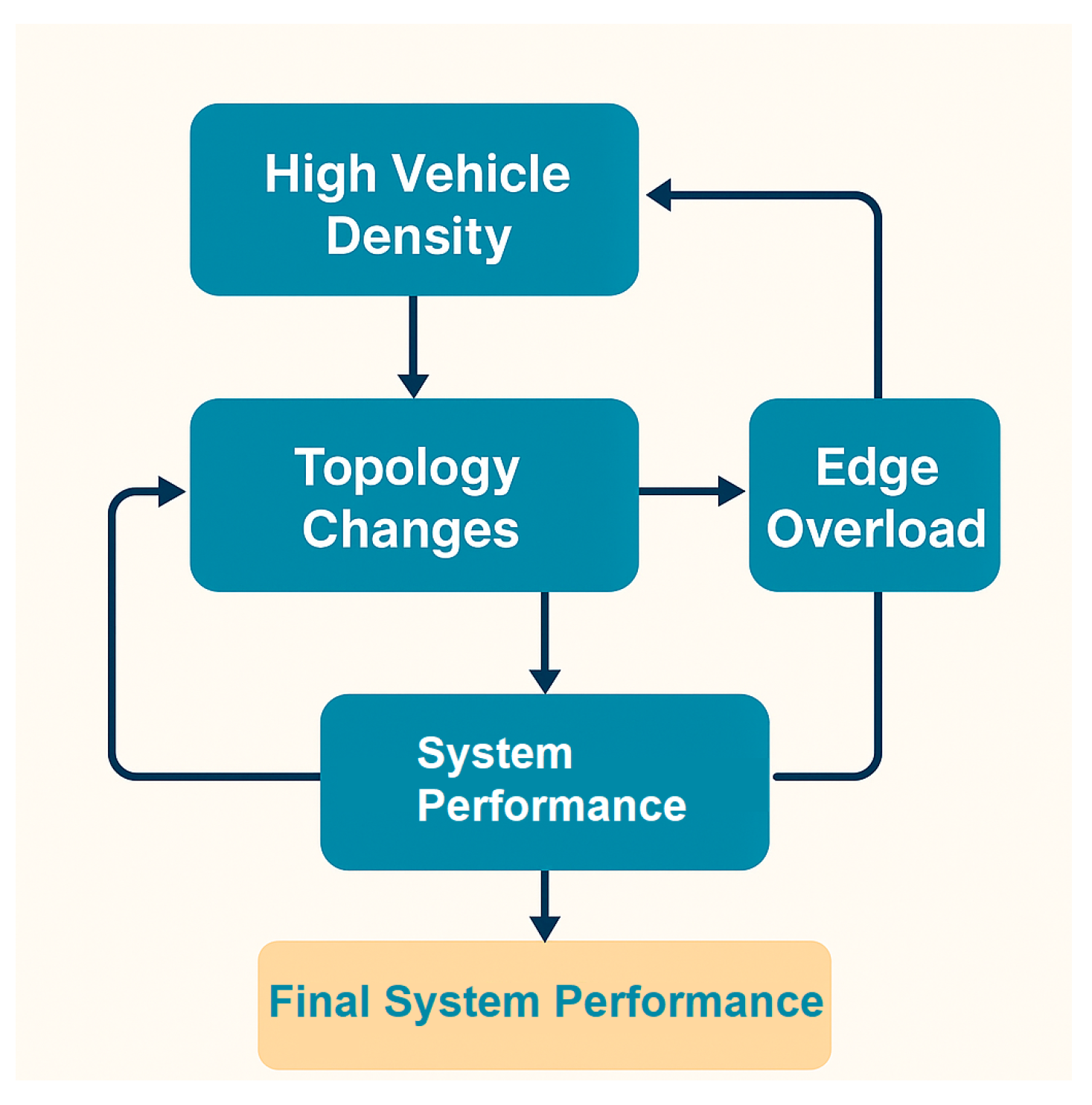

Figure 10 illustrates the main scalability and mobility challenges in VANET–IoT systems. High vehicle density increases channel contention, topology changes cause frequent link disruptions, and edge server overload leads to variable processing delays. Together, these factors degrade overall system performance and create a cyclical feedback loop that must be addressed through adaptive congestion control, mobility prediction, and coordinated edge resource management.

In addition, integrating heterogeneous IoT platforms—each with different communication standards, sampling rates, and data formats—introduces scalability issues at both the data management and application layers.

Table 9 summarizes the main scalability and mobility challenges in VANET–IoT systems, outlining root causes, mitigation techniques, and their limitations [

110,

111,

112]. It highlights the need for adaptive congestion control, predictive mobility modeling, and coordinated edge resource management.

5.3. Interoperability and Standardization Issues

Interoperability is a central challenge in the deployment of large-scale VANET–IoT systems. Vehicles, roadside units, and IoT devices originate from different vendors, operate under distinct communication standards, and exchange heterogeneous data formats. This diversity complicates cross-platform operation and reduces the reliability of cooperative applications. Achieving seamless interoperability across sensing, communication, networking, and application layers is therefore critical for creating a unified, scalable, and dependable vehicular ecosystem.

5.3.1. Heterogeneous Communication Technologies

Modern vehicular environments combine IEEE 802.11p/DSRC, LTE-V2X, NR-V2X, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, ZigBee, and LoRaWAN depending on the device type and communication range. While this diversity increases flexibility, it also introduces compatibility issues. DSRC and C-V2X follow fundamentally different channel access mechanisms, making coexistence and interoperability difficult without additional coordination layers [

93]. Similarly, IoT devices using lightweight protocols such as MQTT or CoAP may not natively integrate with V2X safety messaging standards, requiring translation or gateway-based adaptation.

5.3.2. Semantic and Data-Level Incompatibilities

Even when communication links are established, the meaning, structure, and granularity of exchanged data may not align. Vehicles produce high-rate sensor streams, while IoT devices often rely on low-frequency environmental measurements. Differences in message formats—such as Cooperative Awareness Messages (CAM), Basic Safety Messages (BSM), and IoT sensor payloads—require semantic harmonization to avoid misinterpretation or data loss. Without common data models, cooperative perception and decision-making processes suffer degradation due to inconsistent or incomplete information [

94].

5.3.3. Multi-Layer Standardization Gaps

Current V2X and IoT standards provide fragmented guidance across the protocol stack. While standards bodies such as ETSI, IEEE, and 3GPP define communication rules, they offer limited support for multi-layer interactions. Application-layer standardization remains weak, resulting in incompatible APIs, inconsistent data sampling rates, and divergent system configurations. Interoperability testing across vendors is also insufficient, making large-scale deployment error-prone and costly [

95].

5.3.4. Cross-Domain Integration Challenges

Full integration of VANET and IoT infrastructures requires harmonizing two distinct technological domains. IoT systems prioritize low power consumption, simple communication, and high device heterogeneity. In contrast, VANET applications demand ultra-low latency, strong reliability, and high mobility support. Aligning these conflicting requirements is challenging. For example, IoT devices may not generate data at a frequency sufficient to support real-time driving decisions, while vehicles may overload IoT gateways with high-rate sensor flows.

Hybrid architectures—combining edge processing, protocol translation, and semantic middleware—have been proposed, but achieving full interoperability remains an open problem. Continuous standardization efforts and cross-industry collaboration are necessary to ensure consistent behavior across devices and infrastructures.

Table 10 outlines major interoperability challenges in VANET–IoT systems, covering communication, data, and application layers as discussed in [

113,

114,

115]. It highlights how fragmented standards and heterogeneous technologies hinder large-scale, reliable integration.

5.4. Energy and Resource Constraints

Energy and resource constraints constitute another major barrier to the deployment of large-scale VANET–IoT systems. While vehicles typically have access to ample power, roadside IoT devices, environmental sensors, and edge nodes often operate under strict energy budgets. In addition, the continuous flow of high-rate sensor data, cooperative perception exchanges, and task offloading requests impose significant computational and communication burdens on edge servers and network infrastructure. Ensuring energy-efficient operation across heterogeneous devices is therefore crucial for maintaining long-term sustainability and reliable service quality.

5.4.1. Energy Limitations of IoT and Roadside Devices

Many IoT sensors deployed along roadsides or embedded in urban infrastructure run on batteries or energy-harvesting modules. These devices must balance sensing frequency, communication overhead, and local processing demands. High-frequency sampling can quickly drain available power, while infrequent sampling may produce outdated or incomplete environmental information. Furthermore, protocols such as MQTT, CoAP, and LoRaWAN have different energy footprints, making it challenging to define unified communication strategies suitable for all device types [

96].

5.4.2. Computational Constraints and Offloading Overheads

Task offloading is widely used to reduce the workload on vehicles by transferring compute-intensive tasks—such as object detection or multi-vehicle data fusion—to MEC servers. However, offloading itself carries energy and latency costs. Transmitting large sensor frames consumes substantial power, and frequent offloading can overwhelm edge servers, degrading the performance of latency-sensitive applications [97]. Additionally, fluctuating vehicle mobility complicates scheduling decisions, since a task may not be completed before the vehicle leaves the coverage of the serving edge node.

5.4.3. Resource Fragmentation Across the Cloud–Edge–Vehicle Continuum

VANET–IoT systems rely on distributed computation across cloud servers, multiple edge nodes, and in-vehicle platforms. These resources differ significantly in capacity, availability, and connectivity. Without coordinated orchestration, tasks may be assigned to overloaded nodes, resulting in inefficient energy use and unpredictable delays. Recent efforts propose hierarchical task scheduling models and energy-aware resource allocation to distribute computation more effectively, but cross-layer optimization remains an open research problem [

98].

5.4.4. Energy-Aware Communication and Sensing Strategies

Energy efficiency must also be addressed at the communication level. Adaptive transmission power control can extend device lifetime, but it must be balanced with link reliability and safety requirements. Similarly, context-aware sensing strategies—where sensors adjust sampling rates based on environmental conditions—can reduce unnecessary measurements and communication overhead. AI-based predictive models have been explored to dynamically tune sensing frequencies and offloading decisions based on mobility patterns, expected workload, or predicted battery levels [

99].

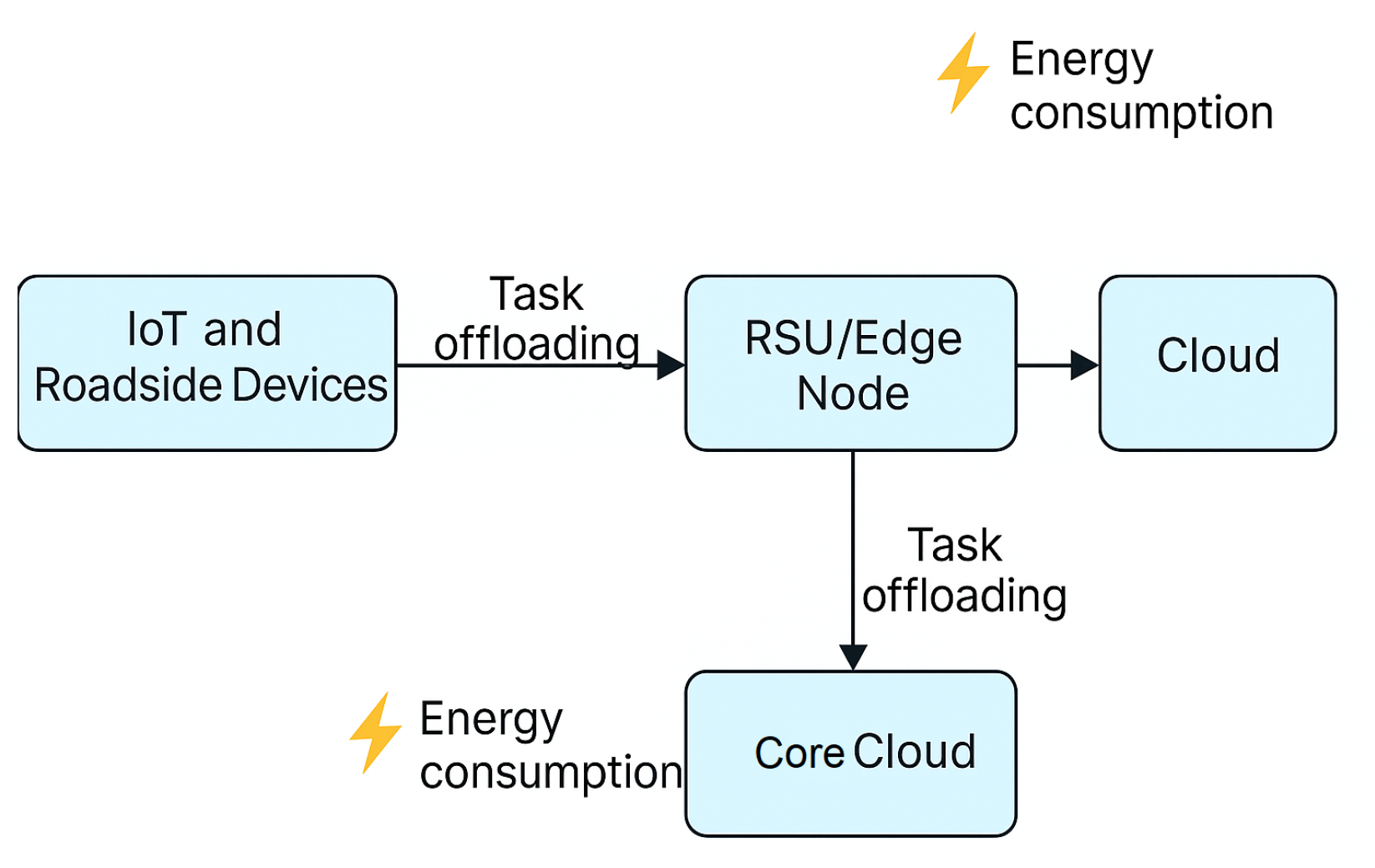

Figure 11 illustrates how energy consumption and computational load are distributed across IoT roadside devices, RSU/edge nodes, and cloud servers in VANET–IoT systems. Task offloading occurs at multiple stages, and each step in the chain introduces additional energy costs. The diagram highlights the need for energy-aware sensing, communication, and computation strategies.

Table 11 summarizes major energy and resource challenges in VANET–IoT systems, drawing from studies [

17,

48,

80,

112]. It outlines the causes of energy constraints across heterogeneous devices and computing tiers, and highlights representative mitigation strategies along with their intrinsic limitations. Addressing these challenges requires coordinated optimization across sensing, communication, and computation layers.

6. Comparative Study

This section synthesizes the main architectural, communication, and protocol-level considerations of VANET–IoT integration. While previous sections have examined technical components individually, the goal here is to provide a cross-dimensional comparison that highlights the trade-offs and complementarities between existing approaches. The comparative analysis is organized into three perspectives: (1) cloud-, edge-, and hybrid-based architectures; (2) V2X communication technologies; and (3) IoT data exchange protocols. Each comparison aims to clarify the strengths, limitations, and suitability of different technologies for VANET–IoT applications.

6.1. Cloud-Based, Edge-Based, and Hybrid Architectures

Architectural choices significantly affect the performance, scalability, and responsiveness of integrated VANET–IoT systems. Cloud-based architectures offer substantial computational power, large-scale analytics, and global context awareness. They are well suited for applications involving long-term traffic modeling, HD map generation, and historical data aggregation [

100]. However, their reliance on backhaul connectivity introduces latency that limits their effectiveness for safety-critical tasks.

In contrast, edge-based architectures provide low-latency processing by executing computation closer to vehicles, typically through RSUs or MEC servers. These architectures are ideal for real-time tasks such as cooperative perception, collision avoidance, and local anomaly detection [

101]. Their main limitations stem from constrained computational capacity and uneven geographic deployment.

Hybrid architectures combine cloud and edge strengths by distributing workload based on latency requirements, computational complexity, and mobility context. Time-sensitive tasks can be executed at the edge, while the cloud handles storage-intensive or computation-heavy workloads. This distributed model is increasingly recognized as a promising foundation for next-generation intelligent transportation systems, though it introduces challenges related to task orchestration, model synchronization, and cross-layer coordination [

102].

6.2. Comparison of V2X Communication Technologies

V2X connectivity is fundamental to enabling cooperation between vehicles, infrastructure, and IoT devices. DSRC (IEEE 802.11p) provides low-latency broadcast communication and has been widely studied due to its simplicity and decentralized operation. It performs well under moderate vehicle density but suffers from channel contention and packet collisions in congested environments [

103].

LTE-V2X and NR-V2X, standardized by 3GPP, offer enhanced reliability and communication range. LTE-V2X supports both direct sidelink communication and network-assisted connectivity, enabling broader service coverage. NR-V2X enhances scheduling flexibility, quality-of-service management, and the ability to support cooperative perception through high-throughput links [

104]. However, these cellular technologies depend on operator-managed infrastructure, which may not be uniformly available across all regions.

From an IoT integration perspective, the coexistence of DSRC, LTE-V2X, cellular IoT, Wi-Fi, and LPWAN introduces interoperability challenges. Each technology offers distinct trade-offs in terms of latency, range, bandwidth, and deployment cost. Selecting the appropriate communication technology depends on application requirements and the density and capabilities of roadside infrastructure.

6.3. IoT Communication Protocols: MQTT, CoAP, and DDS

IoT data exchange protocols further influence the efficiency and reliability of VANET–IoT systems. MQTT, a lightweight publish/subscribe protocol, is widely used for cloud-centric communication and asynchronous data dissemination. Its low overhead and scalability make it suitable for environmental monitoring and vehicle-to-cloud data flows, although its reliance on a broker introduces a single point of failure [

105].

CoAP, designed for constrained devices, enables request/response communication over UDP and supports confirmable messaging. It is typically used in roadside IoT nodes where low-power operation is essential [

106]. CoAP is effective for event-driven sensing but may require additional adaptation layers to interact with V2X safety messages.

DDS (Data Distribution Service) provides real-time publish/subscribe communication with fine-grained quality-of-service control. DDS is increasingly used in autonomous driving platforms to support deterministic data sharing among sensors, control modules, and perception systems [

107]. However, DDS implementations tend to be computationally demanding compared to MQTT and CoAP.

Table 12 provides a comparative analysis of architecture options, V2X technologies, and IoT protocols based on recent contributions [

31,

32,

33,

35,

47,

49,

50]. It highlights the strengths and limitations of cloud-, edge-, and hybrid-based computing models; compares major V2X technologies; and contrasts the characteristics of common IoT protocols based on their suitability for vehicular applications.

7. Future Research Directions

The integration of VANET and IoT technologies continues to evolve rapidly, driven by advances in wireless communication, distributed intelligence, and large-scale sensing infrastructures. Although current systems already demonstrate significant capabilities in cooperative awareness, traffic management, and environmental monitoring, emerging technologies have the potential to reshape the architectural and operational foundations of next-generation intelligent transportation systems. This section outlines promising research directions, focusing on foundational technological shifts, innovative use cases, and key open challenges that must be addressed to fully realize the vision of connected, autonomous, and sustainable mobility.

7.1. Foundational Advancements

7.1.1. 6G-Enabled Vehicular Intelligence

The emergence of 6G networks introduces new opportunities for VANET–IoT integration through sub-THz communication, ultra-low latency, holographic beamforming, and AI-native network control. 6G architectures aim to support extremely dense connectivity with millisecond-level reliability, enabling fine-grained cooperative perception, high-definition map sharing, and swarm-level decision-making [

108]. For vehicular applications, these features can significantly enhance sensing fidelity, reduce communication uncertainty, and facilitate dynamic coordination among vehicles, RSUs, drones, and cloud services.

7.1.2. Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces (RIS)

RIS technology allows the propagation environment itself to be dynamically manipulated. Programmable reflecting surfaces can correct non-line-of-sight conditions, reshape radio beams, and extend communication coverage in dense urban areas [

109]. Incorporating RIS into vehicular networks could mitigate blockage caused by buildings, trucks, or adverse weather, enabling more reliable high-frequency communication between vehicles and infrastructure.

7.1.3. Joint Communication and Sensing (JCAS)

JCAS systems aim to unify radar sensing and communication into a single hardware and waveform framework. For vehicular networks, this enables simultaneous data exchange and real-time perception, reducing hardware redundancy and improving spectral efficiency. Emerging research explores cooperative JCAS, where vehicles jointly sense the environment and share sensing information through V2X links, unlocking new possibilities for collaborative driving and high-resolution environmental reconstruction.

7.1.4. Neuro-Symbolic and Federated Vehicular AI

Traditional deep learning struggles with explainability and cross-domain generalization. Neuro-symbolic AI—which combines neural reasoning with logical structures—offers the potential for safer, more transparent decision-making in vehicular environments [

110]. Furthermore, federated learning (FL) provides a privacy-preserving approach to training AI models across distributed vehicles and edge nodes without sharing raw data. Integrating FL with vehicular edge computing may enable continuously updated perception and prediction models tailored to local traffic conditions.

7.1.5. Quantum-Assisted Vehicular Computing

Although still exploratory, quantum pre-processing and quantum-inspired optimization could accelerate complex vehicular tasks such as multi-agent planning, resource allocation, and secure cryptographic operations [

111]. These capabilities may become increasingly relevant as cooperative perception and V2X data volumes continue to grow.

7.2. Emerging Use Cases

7.2.1. Aerial and Space-Assisted Vehicular Networks (A-V2X)

Future transportation systems will increasingly rely on aerial platforms such as UAVs, stratospheric balloons, and low-Earth-orbit satellites. These platforms can extend connectivity to rural areas, assist in incident detection, and provide rapidly deployable communication infrastructure during emergencies [

112]. Integrating airborne sensing with ground-level vehicular data enables multi-layer situational awareness and enhances resilience.

7.2.2. Industrial Vehicle-to-Everything (IV2X)

Beyond urban mobility, V2X technologies are expanding into industrial environments, including warehouses, ports, and smart logistics hubs. Automated guided vehicles, drones, and robotic equipment require deterministic latency and precise coordination. IoT-enhanced V2X communication can support collision avoidance, task orchestration, and digital-twin-based operational optimization [

113].

7.2.3. Metaverse-Driven Simulation and Digital Twins

The convergence of VANET–IoT systems with metaverse-based digital twins offers powerful tools for modeling large-scale transportation systems [

114]. These environments integrate real-time data from vehicles and IoT sensors with virtual simulation platforms, enabling scenario testing, predictive maintenance, and hybrid human–machine interaction models. Such systems can support infrastructure planning, fleet optimization, and proactive traffic policy design.

7.2.4. Extended Reality (XR) for Cooperative Driving

Emerging XR interfaces can assist drivers, pedestrians, and road workers by overlaying situational information onto the physical environment. Combined with V2X communication, XR systems may provide real-time hazard visualization, augmented navigation cues, and collaborative driving assistance [

115].

7.3. Open Research Challenges for Future VANET–IoT

Despite the rapid progress outlined above, several open research questions remain central to the advancement of next-generation vehicular networks.

7.3.1. AI Trustworthiness and Safety Guarantees

As AI becomes embedded in perception, prediction, and planning modules, ensuring transparency, robustness, and certifiable safety remains challenging. Methods for verifying AI components under extreme mobility, diverse environments, and rare events are still immature.

7.3.2. Spectrum Coexistence and High-Frequency Reliability

6G and sub-THz communications require reliable propagation under mobility, but susceptibility to blockage and reflection poses challenges. Effective coexistence between DSRC, C-V2X, NR-V2X, Wi-Fi, and IoT protocols must also be ensured through adaptive spectrum sharing and interference management.

7.3.3. Large-Scale Digital Twin Synchronization

Digital twin–enabled transport systems need continuous synchronization between physical and virtual environments. Achieving this at city scale requires highly efficient data ingestion pipelines, semantic consistency, and coordinated updates between vehicles, IoT sensors, and cloud platforms.

7.3.4. Cross-Domain Privacy and Data Governance

Future VANET–IoT ecosystems must integrate heterogeneous data from public agencies, private fleets, individual vehicles, drones, and roadside IoT sensors. Ensuring privacy while maintaining data utility for learning and optimization remains an open challenge that requires advances in differential privacy, federated learning, and policy-driven data governance.

Table 13 highlights emerging research directions shaping future VANET–IoT systems, with representative examples from [

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

114,

115]. It highlights emerging technologies, their expected contributions to vehicular ecosystems, and the remaining scientific challenges that must be addressed in upcoming research.

8. Conclusions

This survey examined the technological, architectural, and operational foundations of VANET–IoT integration and highlighted its transformative potential for future intelligent transportation systems. By analyzing communication models, computing paradigms, and protocol choices, the study showed that the evolution toward the Internet of Vehicles relies on a coordinated interplay between cloud, edge, and in-vehicle computing. Technologies such as C-V2X and NR-V2X, when combined with IoT-driven sensing and adaptive offloading mechanisms, are essential to meeting the stringent latency, reliability, and scalability requirements of cooperative mobility.

Across the system stack, the review identified security, interoperability, mobility-induced instability, and energy constraints as persistent challenges. These issues are not independent; rather, they form an interconnected landscape in which improvements at one layer influence—and often depend on—advances at others. Addressing these challenges requires unified approaches that combine lightweight security mechanisms, standardized data models, intelligent resource allocation, and cross-layer optimization strategies. Looking ahead, emerging technologies such as 6G communication, reconfigurable intelligent surfaces, joint communication-and-sensing frameworks, AI-enhanced digital twins, and quantum-assisted optimization have the potential to reshape the design of vehicular networks. At the same time, new application domains, including aerial V2X, industrial automation, and metaverse-enabled simulation, will demand unprecedented levels of integration between vehicles, infrastructure, and distributed sensing systems.

Realizing this vision will require sustained research efforts focused on trustworthy AI, large-scale interoperability, comprehensive standardization, and energy-efficient architecture. By addressing these open issues, the integration of VANET and IoT can evolve from an emerging paradigm into a robust and pervasive foundation for safe, efficient, and sustainable transportation ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. and S.N.; Methodology, K.K. and S.N.; Formal Analysis, K.K. and L.B.; Investigation, K.K., L.B., and H.B.; Resources, S.N. and H.B.; Data Curation, L.B. and H.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, K.K.; Writing—Review and Editing, S.N., L.B., and H.B.; Visualization, K.K.; Supervision, S.N. and H.B.; Project Administration, K.K. and S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the faculty members, researchers, and technical staff who contributed valuable insights during the preparation of this survey. Their feedback helped refine the structure, improve the clarity of the analysis, and strengthen the overall quality of the manuscript. The authors also acknowledge the support of their respective institutions for providing access to research facilities, scientific resources, and academic databases that enabled the completion of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| BSM |

Basic Safety Message |

| CAM |

Cooperative Awareness Message |

| CAN |

Controller Area Network |

| C-V2X |

Cellular Vehicle-to-Everything |

| CoAP |

Constrained Application Protocol |

| DDS |

Data Distribution Service |

| DENM |

Decentralized Environmental Notification Message |

| DoS |

Denial of Service |

| DT |

Digital Twin |

| FL |

Federated Learning |

| GNSS |

Global Navigation Satellite System |

| HD Map |

High Definition Map |

| IMU |

Inertial Measurement Unit |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| IoV |

Internet of Vehicles |

| ITS |

Intelligent Transportation System |

| JCAS |

Joint Communication and Sensing |

| MEC |

Mobile Edge Computing |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| MQTT |

Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| NR-V2X |

New Radio Vehicle-to-Everything |

| OBU |

On-Board Unit |

| PC5 |

Direct Sidelink Interface |

| PKI |

Public Key Infrastructure |

| QoS |

Quality of Service |

| RIS |

Reconfigurable Intelligent Surface |

| RSU |

Roadside Unit |

| Uu |

Cellular Uplink/Downlink Interface |

| URLLC |

Ultra-Reliable Low-Latency Communication |

| V2I |

Vehicle-to-Infrastructure |

| V2N |

Vehicle-to-Network |

| V2P |

Vehicle-to-Pedestrian |

| V2V |

Vehicle-to-Vehicle |

| V2X |

Vehicle-to-Everything |

| VANET |

Vehicular Ad-Hoc Network |

| XR |

Extended Reality |

References

- Vogt, J.; Schotten, H.D.; Wieker, H. Intelligent transportation system protocol interoperability evaluation. IEEE Open J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 6, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, K. Joint use of DSRC and C-V2X for V2X communications in the 5.9 GHz ITS band. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 15, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzi, A.; Berthet, A.O.; Campolo, C.; Masini, B.M.; Molinaro, A.; Zanella, A. On the design of sidelink for cellular V2X: A literature review and outlook for future. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 97953–97980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, M.; Pascale, F.; Santaniello, D. Internet of Things: A general overview between architectures, protocols and applications. Information 2021, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y. Digital twin networks: A survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 13789–13804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedar, R.; Lopez, O.; Heinrich, R.; García, M.; Kowalski, T.; Novak, P.; Schmidt, F.; Rossi, L.; Kumar, A.; Zhang, Y. Standards-compliant multi-protocol on-board unit for the evaluation of connected and automated mobility services in multi-vendor environments. Sensors 2021, 21, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jooriah, M.; Datsenko, D.; Almeida, J.; Sousa, A.; Silva, J.; Ferreira, J. A co-simulation platform for V2X-based cooperative driving automation systems. In Proc. 2024 IEEE Veh. Netw. Conf. (VNC); 2024; pp. 227–230.

- Cui, G.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Yao, L.; Fang, Z. Cooperative perception technology of autonomous driving in the Internet of Vehicles environment: A review. Sensors 2022, 22, 5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthurs, P.; Gillam, L.; Krause, P.; Wang, N.; Halder, K.; Mouzakitis, A. A taxonomy and survey of edge cloud computing for intelligent transportation systems and connected vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 6206–6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostefaoui, A.; Merzoug, M.A.; Haroun, A.; Nassar, A.; Dessables, F. Big data architecture for connected vehicles: Feedback and application examples from an automotive group. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 134, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbaje, P.; Anjum, A.; Mitra, A.; Al-Dulaimi, A.; Mohanty, A. Survey of interoperability challenges in the Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 22838–22861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zuo, F.; Yang, D.; Wang, Y.; Ozbay, K.; Seeley, M. Toward equitable progress: A review of equity assessment and perspectives in emerging technologies and mobility innovations in transportation. J. Transp. Eng. 2025, 151, 03124003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, J.; Mullins, D.; Deegan, B.; Horgan, J.; Ward, E.; Eising, C.; Denny, P.; Jones, E.; Glavin, M. Wireless access for V2X communications: Research, challenges and opportunities. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 26, 2082–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.H.C.; Molina-Galan, A.; Boban, M.; Gozalvez, J.; Coll-Perales, B.; Şahin, T.; Kousaridas, A. A tutorial on 5G NR V2X communications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 1972–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Saha, R.; Kumar, G.; Kim, T. The security perspectives of vehicular networks: A taxonomical analysis of attacks and solutions. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amari, H.; El Houda, Z.A.; Khoukhi, L.; Belguith, L.H. Trust management in vehicular ad-hoc networks: Extensive survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 47659–47680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Liu, J.; Ren, J.; Zhang, Y. Intelligent task offloading in vehicular edge computing networks. IEEE Wireless Commun. 2020, 27, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Jin, Y.; Lang, C.; Li, Y. Collaborative perception in autonomous driving: Methods, datasets, and challenges. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2023, 15, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebamikyous, H.; Kashef, R. Autonomous vehicles perception (AVP) using deep learning: Modeling, assessment, and challenges. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 10523–10535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]