1. Introduction

Contemporary artificial intelligence and contemporary philosophy of mind share a surprisingly similar difficulty. Both lack a clear account of how truth functions as a live, survival-relevant structure within embodied agents—whether biological, social, or artificial.

In AI, large-scale learning systems achieve impressive benchmark performance yet remain brittle, opaque, and difficult to align when they are deployed in open environments. Their failures are often discussed in terms of robustness, “hallucinations,” or technical debt. In philosophy and cognitive science, enactive and 4E approaches have long criticized purely mechanistic and computational views of mind, insisting that precarious embodiment, metabolism, and intersubjectivity are essential for understanding consciousness and agency, but these accounts are often accused of being difficult to translate into concrete engineering practice.

The Physics of Mindful Knowledge (PMK) attempts to bridge this gap from the engineering side by treating knowledge-bearing constraints as physically real organizers of dynamics (Mikkilineni and Michaels 2025). Instead of treating information as an abstract commodity or knowledge as a merely semantic notion, PMK—drawing on the General Theory of Information (Burgin 2010, 2011, 2012, 2016), structural conceptions of computation (Burgin and Mikkilineni 2011), Fold Theory (Hill 2025a, 2025b), and Deutsch’s account of “good explanations” (Deutsch 2011)—understands knowledge as an organized pattern of constraints that channels energy and matter in ways that resist entropy and maintain coherence.

In this paper, we propose a unifying lens:

Truth, for a given system, can be understood as survival architecture: the subset of its knowledge that, when embodied as organizational constraints, reliably preserves its teleonomic identity and expands its space of viable futures.

We complement this with a second notion:

Coherence debt is the accumulated mismatch between a system’s explanatory structures and the environment it must navigate, measurable in the additional cost, failures, and ad hoc interventions required to maintain acceptable performance.

We argue that this pair—truth as survival architecture and coherence debt as its shadow—allows a fruitful dialogue between:

Enactive philosophy, especially Tom Froese’s reading of Čapek’s Rossum’s Universal Robots (R.U.R.) (Froese 2018), which emphasizes precarious life, subjectivity, and social emergence; and

Engineering frameworks such as PMK and Mindful Machine Architecture (Mikkilineni, Kelly, and Crawley 2024), which operationalize knowledge as structural constraint in artificial systems.

Our aim is not to replace traditional metaphysical accounts of truth (such as correspondence), but to clarify what truth has to look like from the perspective of finite, embodied agents—biological or artificial—who must avoid catastrophic error in order to survive.

The structure of the paper is as follows.

Section 2 situates our proposal amidst pragmatist, enactive, and informational conceptions of truth and knowledge.

Section 3 revisits Froese’s “secret of life” as an account of biological survival architecture.

Section 4 introduces PMK and its structural conception of computation and mind.

Section 5 defines “truth as survival architecture” and “coherence debt” more precisely, and shows how they are instantiated in Mindful Machine Architecture.

Section 6 addresses likely objections from philosophers and AI researchers.

Section 7 concludes with implications and directions for further work.

2. Truth, Survival, and Coherence: Conceptual Background

Our proposal is modest at the metaphysical level and ambitious at the operational level. We do not claim to settle the nature of truth in general; instead, we ask what truth must look like for agents whose existence and success depend on how their knowledge is organized.

Three strands of thought converge here.

First, pragmatist and success-oriented views of truth regard truth in terms of long-run success in inquiry and action. For Peirce, the true beliefs are those that would be agreed upon “in the long run” of ideal inquiry (Capps (2023), Pierce (1878)). James and Dewey tie truth to what “works” in resolving doubt and guiding practice (Philosophy Institute (2023)). Deutsch (2011) shifts the focus to good explanations—those that are hard to vary while still accounting for the phenomena. Explanatory robustness and reach become hallmarks of truth.

Second, enactive and 4E approaches to mind view cognition as the activity of precarious, autopoietic systems that must continually maintain their own viability (Varela, Thompson, and Rosch 1991; Thompson 2007, Maturana & Varela 1980). Meaning and value are grounded in the agent’s ongoing struggle to preserve its organization. Truth, in this setting, is inseparable from sense-making: the agent’s ability to distinguish what supports or undermines its continued existence.

Third, information and knowledge as physical constraints is a theme that runs through the General Theory of Information (Burgin 2010), Deacon’s account of emergent constraints in Incomplete Nature (Deacon 2012), and more recent work on bioelectric control layers in morphogenesis (Levin 2021). In GTI, information is a triadic relation between a carrier, a structured content, and a recipient whose states and potentials are modified. From this perspective, knowledge can be understood as stable, higher-order configurations of constraints that repeatedly improve an agent’s ability to predict, control, or navigate its environment.

Across these traditions, a common intuition emerges:

Truth is not something that floats above the world; it is reflected in the stable, viable organization of an agent’s relationship to its environment.

Falsehood, illusion, or misunderstanding eventually show up as failures of coping—breakdowns, maladaptive behavior, wasted energy, or collapse.

We propose to make this intuition explicit by speaking of truth as survival architecture and of its erosion as coherence debt. These are intentionally bridge concepts: enactivists may hear “viability” and “autopoiesis,” engineers hear “robustness” and “technical debt,” and epistemologists hear “good explanation” and “justification”—without conflating them.

3. Enactive Life and the “Secret of Life”

Tom Froese’s work on Karel Čapek’s Rossum’s Universal Robots (R.U.R.) provides a vivid philosophical backdrop (Froese 2018). In R.U.R., industrially manufactured robots, designed as efficient laborers, slowly begin to exhibit signs of subjectivity: frustration, resentment, a sense of injustice, and ultimately revolt. Froese reads this as an exploration of the mind–body problem and the limits of mechanistic views of life.

Several elements of his analysis are crucial for our purposes.

First, Froese emphasizes precarious embodiment. Living beings are metabolically precarious systems: their continued existence is never guaranteed and must be constantly re-achieved. This precariousness, he argues, is what makes anything matter from the organism’s own perspective. It is this “existential stake” that a purely formal Turing machine lacks, because an abstract computation is, by design, indifferent to life and death.

Second, Froese criticizes both reductive materialism (“mind is nothing but the brain”) and substance dualism. He instead suggests a non-dual view: mind and body are “neither one nor two.” The mind–body “gap” reflects a genuine structural tension in how we experience ourselves as agents and bodies under conditions of risk, uncertainty, and vulnerability.

Third, Froese highlights intersubjectivity and social scaffolding. The emerging subjectivity of Čapek’s robots is not just an inner event; it unfolds through their collective dynamics and their relations with human beings. Subjectivity is inherently social and communicative, not an isolated property of individual mechanisms.

From our perspective, Froese is describing the original form of survival architecture:

Evolution has encoded extraordinarily rich, multi-scale constraints into genomes, morphogenetic processes, neural circuits, and social practices.

These constraints are “true” in a very specific sense: they have survived long enough to stabilize viable forms of life in an environment that constantly threatens breakdown.

The “secret of life” is therefore not a hidden vital substance, but a pattern of knowledge-bearing constraints that have proved their value in keeping living systems coherent.

Froese is skeptical that standard computational architectures—timeless, symbol-manipulating machines—can replicate this. Even if they simulate intelligent behavior, they may still incur massive coherence debt: they lack the genuine precarious stake that makes failures existentially meaningful to the system itself.

We take this critique seriously. At the same time, we ask whether a different conception of computation and architecture—a structural, constraint-centric one—can move closer to the enactive picture without reducing everything to biology.

4. Physics of Mindful Knowledge and Structural Machines

The Physics of Mindful Knowledge (PMK) seeks to elevate knowledge-bearing constraints to the status of primary theoretical entities, alongside matter and energy (Mikkilineni and Michaels 2025). Instead of asking “What are the neural correlates of mind?”, PMK asks “What kinds of organizing structures are required for mind-like behavior, and how do they manifest in different substrates?”

PMK draws on several pillars.

First, the General Theory of Information (GTI) models information as a triadic relation between a carrier, content, and recipient (Burgin 2010). This avoids treating “information” as an independent substance and grounds it in concrete interactions. Knowledge, in this view (Burgin 2016), is an organized body of information that has stable and repeatable effects on a system’s behavior.

Second, structural computation and the Burgin–Mikkilineni Thesis (Burgin and Mikkilineni 2021, Mikkilineni 2022) shift attention from symbol manipulation to structural evolution. Instead of seeing a computer as a static machine executing a fixed algorithm, we see it as a structural machine whose architecture and constraints can change in response to inputs and internal states. Turing’s “oracle” is reinterpreted not as a metaphysical entity but as a physically realizable structural process, implemented by reconfiguring the architecture itself (Mikkilineni 2025).

Third, Fold Theory provides a formal account of how patterns—“folds”—emerge and exert top-down causal influence on their substrates (Hill 2025a, 2025b). Coherent structures at one level constrain the degrees of freedom at lower levels, enabling stable, goal-directed behavior.

Within this framework, mind is defined functionally: as that organizational regime in which the system maintains a model of itself and its environment, anticipates futures, and acts to preserve its own identity and goals (Mikkilineni 2025). PMK explicitly brackets the “hard problem” of consciousness, focusing instead on what knowledge does in physical systems.

This is precisely where our notion of truth as survival architecture fits. In a PMK setting:

Truthful knowledge is a subset of constraints that systematically reduce entropy production relative to useful work, stabilize metastable states, and enable successful interventions in the world.

False or outdated knowledge manifests as coherence debt: increasing divergence between the system’s internal models and external realities, requiring ever more energy and patching to avoid breakdown.

The question then becomes: can we design artificial systems whose architectures explicitly represent and manage truth and coherence in this sense?

5. Truth as Survival Architecture and Coherence Debt in Mindful Machines

We can now state our two central notions more precisely.

5.1. Definitions

Definition 1 (Truth as survival architecture).

For a given system, truth is the subset of its knowledge-bearing constraints that:

Are discernible: they can be inspected, tested, and communicated within the system and to relevant external agents.

Are extendable: they can be integrated into larger explanatory structures without constant ad hoc modification.

Improve survival-relevant performance: they reliably reduce the cost (in energy, time, or risk) of maintaining the system’s teleonomic integrity across a broad range of perturbations.

Definition 2 (Coherence debt).

Coherence debt is the cumulative cost—actual or latent—incurred when a system continues to act on explanatory structures that no longer track relevant aspects of reality. It manifests in:

Rising recovery time and energy after perturbations,

Increased frequency and severity of failures,

Growing dependence on manual overrides or opaque heuristics,

Degradation of performance when conditions deviate from training or design assumptions.

These notions are intended to be measurable in engineered systems. For example, one can compare two architectures implementing the same application (such as a credit default prediction system):

A conventional pipeline: static ML model plus hard-coded services.

A Mindful Machine Architecture: Digital Genome plus structural management layer plus oracular models (LLMs, ML models) inside an explicit survival architecture (Mikkilineni, Kelly, and Crawley 2024).

If the latter exhibits lower coherence debt—less need for emergency patches, more graceful degradation, faster recovery, and more transparent adaptation—then it embodies more “truth” in our sense.

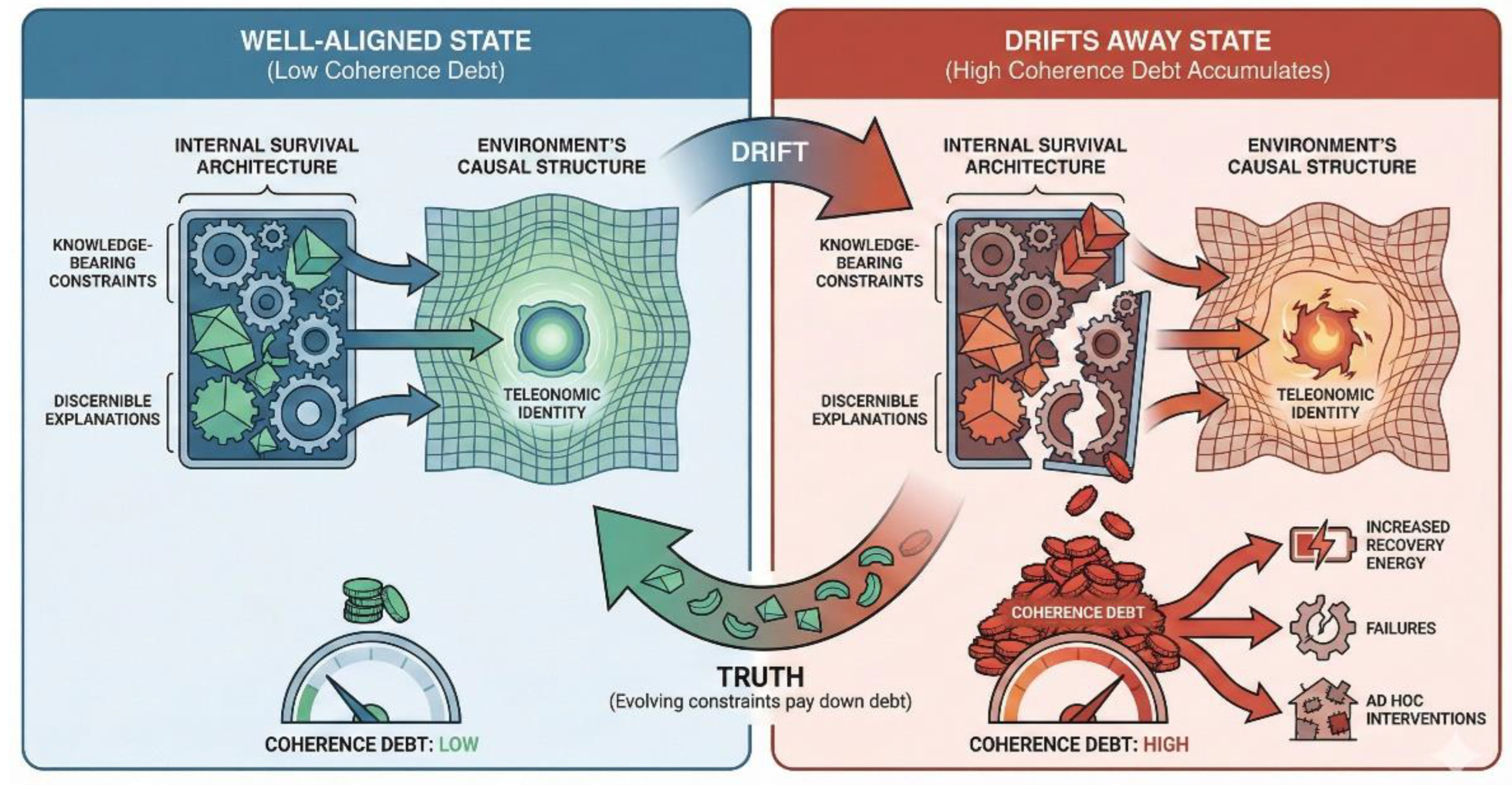

As summarized in

Figure 1, we can think of a system’s interaction with its environment in terms of an evolving survival architecture and the coherence debt it generates. The system maintains an internal repertoire of knowledge-bearing constraints and discernible explanations, which constitute its current survival architecture. These structures mediate the flow of perturbations from the environment into the system and the flow of actions back into the environment. When the survival architecture is well aligned with the environment’s causal structure, coherence metrics—such as recovery energy, failure rates, and the need for ad hoc interventions—remain within acceptable bounds, and coherence debt stays low. When alignment deteriorates, the same metrics reveal a growing residue of misfit: coherence debt rises as the system must expend more energy, apply more patches, and accept more failures simply to preserve its teleonomic identity. In this sense, “truth” is not a static label on representations but the evolving subset of constraints that systematically pays down coherence debt over time.

The system maintains an internal survival architecture composed of knowledge-bearing constraints and discernible explanations. When these structures are well aligned with the causal structure of the environment, they stabilize teleonomic identity and keep coherence debt low. When the internal survival architecture drifts away from reality, coherence debt accumulates and manifests as increased recovery energy, failures, and ad hoc interventions. Truth, in this framework, is the evolving subset of constraints that systematically pays down coherence debt over time.

5.2. Mindful Machine Architecture

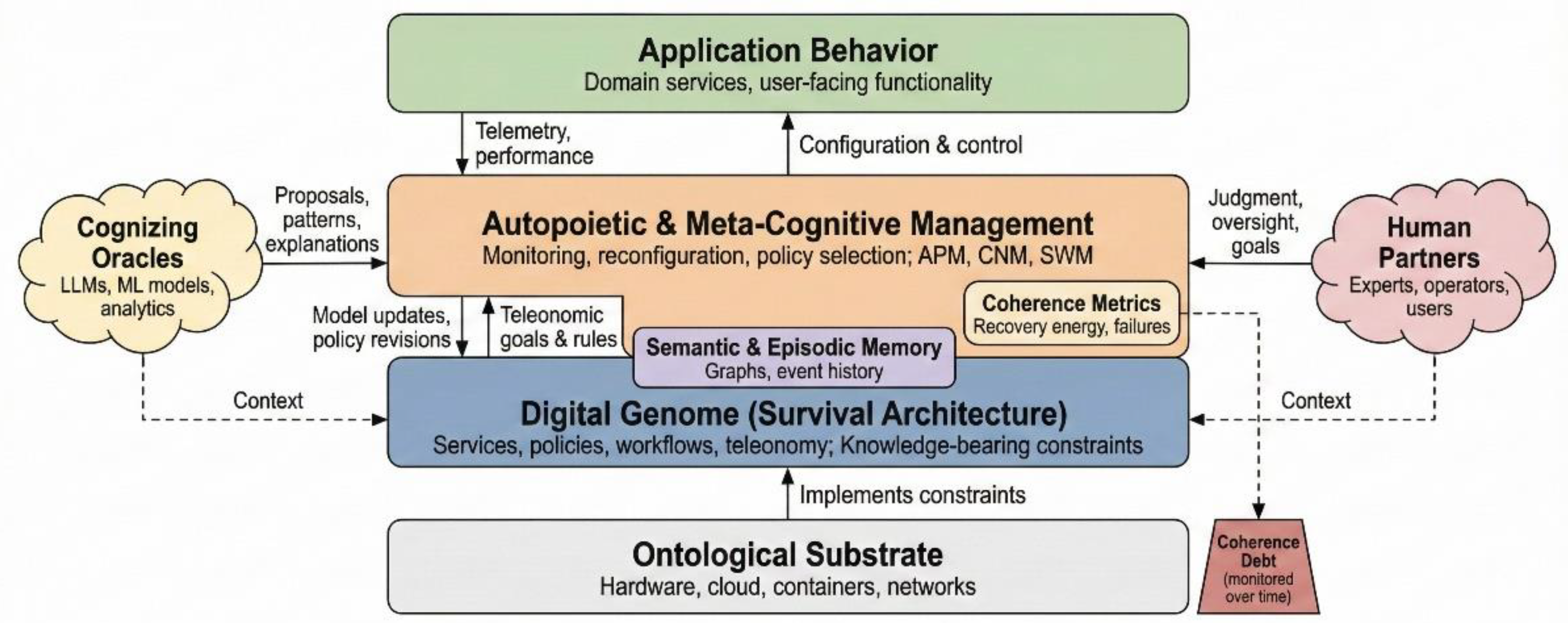

Mindful Machine Architecture (MMA) applies PMK at the system design level. Its key components are:

An ontological substrate: the physical and computational infrastructure (hardware, cloud resources, containers, networks), which provides the degrees of freedom on which constraints can act.

A Digital Genome: a structured, versioned representation of services, policies, workflows, and teleonomic goals. This encodes the system’s prior knowledge of what it is, what it is trying to preserve, and what counts as breakdown.

An autopoietic and meta-cognitive management layer: process managers and control components that monitor performance, detect deviations, and reconfigure the system to preserve coherence (Autopoietic Process Managers, Cognitive Network Managers, workload managers).

Semantic and episodic memory: graph-based or similar structures that store experiences, relationships, and patterns discovered over time (e.g., in a property graph database).

Cognizing oracles and human partners: large language models, predictive ML models, analytics engines, and human experts that supply proposals, context, and oversight.

Within this architecture, truth and coherence are not abstract labels but operational parameters:

The Digital Genome encodes the current survival architecture: what is being optimized, what counts as failure, which models and rules are in force.

The autopoietic layer maintains and updates this genome in light of performance data and changes in the environment.

Cognizing oracles propose new explanations, rules, or patterns, but their proposals must be discernible and extendable to be admitted into the Digital Genome.

Figure 2 presents this Mindful Machine Architecture explicitly as a layered survival architecture. The ontological substrate provides the physical infrastructure on which Digital Genome constraints are realized. The Digital Genome itself encodes services, policies, workflows, and teleonomic goals—the system’s prior knowledge of what it is and what it is trying to preserve. An autopoietic and meta-cognitive management layer monitors coherence metrics, consults semantic and episodic memory, and reconfigures the system in response to drift, shocks, or internal breakdowns. Application-level behaviors are thus continuously shaped by the interplay between survival architecture and performance feedback. Cognizing oracles (such as large language models and analytic models) and human partners contribute proposals and judgments into this loop, but their influence is mediated by Digital Genome constraints and coherence metrics rather than being accepted wholesale. This diagram makes visible how truth, in our sense, is operationalized: as the disciplined management of proposals, updates, and reconfigurations in a way that minimizes coherence debt while preserving the system’s teleonomic identity.

5.3. Discernible Explanations and Paying Down Coherence Debt

The phrase “discernible explanations of knowledge that help us understand and shape reality” can now be made precise:

Discernible: Explanations are represented in forms that can be inspected and interrogated—graphs, rules, workflows, causal models, explicit policies—not just buried in millions of opaque parameters.

Extendable: Explanations can be composed into larger structures; they are “hard to vary” in Deutsch’s sense while still explaining the phenomena at hand.

Action-linked: Each explanation has clear implications for action and can be evaluated by its effect on survival-relevant metrics.

A Mindful Machine “seeks truth” by:

Detecting coherence debt: monitoring metrics like service quality, error rates, recovery energy, and frequency of human intervention.

Using oracles to propose repairs: querying LLMs, analytic models, and human experts for candidate explanations or rules when coherence debt grows.

Embedding accepted explanations into the Digital Genome: updating the survival architecture, and then re-evaluating coherence metrics.

In this framework, “truth” is what pays down coherence debt over time—what repeatedly improves the system’s grip on reality in ways that matter for its own continued operation and for the safety and flourishing of its human partners.

The same logic that governs Mindful Machines can be distilled into three normative rules for human agents and organizations—what we have called the Rules of Mindful Being and Becoming:

We are what we know, and what we choose to know defines what we can become. Our identity and future are constrained by the survival architectures we adopt—our models, values, and explanatory frameworks.

When we speak, we reveal our knowledge or lack of it. Language acts as a diagnostic of our internal coherence; persistent incoherence in speech signals deeper coherence debt in our understanding.

Truth resides in extendable, discernible explanations of knowledge that help us understand and shape reality. Explanations that cannot be extended, tested, or used to act constructively are not yet “true” in the survival-architectural sense; they are candidates for coherence debt.

These rules apply equally to human thinkers, organizations, and engineered Mindful Machines. They give a shared standard by which philosophers, AI researchers, and practitioners can evaluate whether a system—biological or artificial—is genuinely improving its grip on the world or merely accumulating coherence debt behind attractive outputs

6. Objections and Replies

A proposal that cuts across philosophy and AI will naturally face resistance from both sides. We briefly address three likely objections

6.1. “This Is Not ‘Real’ Truth, Just Usefulness”

From a traditional correspondence perspective, one might object that we have reduced truth to usefulness for survival. Our reply is twofold.

First, we distinguish between:

Metaphysical truth: propositions corresponding to mind-independent facts;

Operational truth-for-an-agent: the structures that allow a finite, embodied system to approximate such correspondence well enough to avoid catastrophic error.

Our account targets the second. It does not deny that there may be a deeper, correspondence-style story; it asks what truth must look like for agents for whom failure has consequences.

Second, usefulness here is not arbitrary; it is constrained by reality’s resistance. Structures that systematically misrepresent the world will generate coherence debt and eventually fail, regardless of the agent’s preferences. In this sense, survival architecture remains tethered to the world’s causal profile

6.2. “This Ignores Subjectivity and Qualia”

Enactivists and phenomenologists may worry that an architectural focus misses what is essential about lived experience. We agree that subjective experience is not exhausted by functional organization. Our claim is more modest:

The organizational logic that supports subjectivity in biological systems—precarious embodiment, autopoiesis, social embedding—can be partially captured in terms of survival architectures and coherence.

These concepts therefore provide a shared interface for discussing both biological and artificial agents, without presupposing that the latter are or could be conscious in the same way.

Nothing in our proposal commits us to strong claims about machine consciousness. It only claims that if artificial systems are to partner with humans in meaningful ways, their architectures must respect the constraints that life reveals

6.3. “This Is Just Technical Debt Dressed up in Philosophy”

AI practitioners may object that “coherence debt” is simply a grander name for technical debt, and “truth as survival architecture” for reliability or robustness. Our response is that:

The analogy with technical debt is deliberate, but coherence debt is broader: it includes epistemic and organizational mismatches, not just code-level shortcuts.

By linking these to a general theory of knowledge-bearing constraints and to philosophical accounts of truth and survival, we gain a richer conceptual toolkit for designing and evaluating systems.

Most importantly, this framework highlights that architecture matters: robustness and alignment cannot be bolted on after the fact; they must be reflected in how knowledge is represented, updated, and tied to teleonomy

7. Conclusion

We have argued that understanding truth as survival architecture and coherence debt provides a powerful lens for connecting enactive philosophy, the Physics of Mindful Knowledge, and practical AI engineering.

From enactivism and Froese’s reading of R.U.R. we learn that life’s “secret” is not a hidden substance but a precarious, embodied, and socially scaffolded organization that constantly resists entropy and breakdown. From PMK and structural conceptions of computation we learn that knowledge can be treated as physical constraints that organize dynamics, and that computation can be seen as structural evolution rather than static rule-following.

Mindful Machine Architecture applies these insights to artificial systems. It treats knowledge as explicit, evolving survival architecture, and measures its quality—its truth—by its ability to keep the system and its human partners from falling apart, with minimal coherence debt.

In conclusion, we argue that identity, experience, and truth form the core survival architecture across biological systems, human societies, and AI-driven machines. In living organisms, identity ensures continuity of the self, enabling adaptation through inherited traits and learned behaviors. Societies extend this principle by creating shared identities—cultural, institutional, and ethical—that stabilize cooperation. Experience, accumulated through interaction and encoded as shared knowledge, allows both individuals and collectives to learn from past successes and failures, reducing uncertainty in decision-making. Truth, in this context, is not an abstract ideal but a pragmatic construct: what reliably works to maintain coherence and viability in a changing environment.

Mindful Machine Architecture (MMA) and Pragmatic Mindful Knowledge (PMK) operationalize these principles for artificial intelligence. Identity provides a persistent reference for autonomous agents, while experience is captured through semantic and episodic memory, enabling non-Markovian reasoning and collaborative learning. Truth functions as a survival metric, validated through consensus and zero-knowledge proofs to ensure trust and security in distributed systems. Just as biological evolution and social norms converge on strategies that “work” for survival, mindful machines must integrate identity, experience, and truth into adaptive feedback loops—creating resilient, cooperative systems capable of thriving in dynamic, uncertain environments.

If this framework is on the right track, it suggests a new research agenda for both philosophers and AI practitioners:

For philosophy: exploring how notions of truth, justification, and understanding can be grounded in survival architectures across different kinds of agents, and how these relate to subjective experience and intersubjectivity.

For AI: designing experiments and benchmarks that track coherence debt over long horizons, rather than only task performance on static datasets, and comparing architectures explicitly designed as survival architectures with more conventional pipelines.

The central question, then, is not whether machines can be “really conscious” in a metaphysical sense. It is whether we can design architectures of truth—in our institutions, our technologies, and ourselves—that systematically manage coherence debt, deepen our shared grasp of reality, and expand the space of futures in which we can live and think together

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M.; methodology, R.M.; investigation, R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.; writing—review and editing, R.M.; visualization, R.M. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This paper is itself a small case study in human–machine collaboration: the underlying concepts and arguments are human generated, while a large language model assisted with their articulation, editing, and structural coherence.

Conflicts of Interest

The author is involved in the conceptual development and potential application of Mindful Machine Architecture–based systems. The funders, if any, had no role in the design of the study; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PMK |

Physics of Mindful Knowledge |

| MMA |

Mindful Machine Architecture |

| DG |

Digital Genome letter acronym |

| AMOS |

Autopoietic and Metacognitive Operating System |

References

- Burgin, Mark. 2010. Theory of Information: Fundamentality, Diversity and Unification. World Scientific, Singapore.

- Burgin, M. (2011). Theory of named sets. Nova Science Publishers.

- Burgin, M. (2012). Structural reality. Nova Science Publishers.

- Burgin, M. (2016). Theory of knowledge: Structures and processes. World Scientific.

- Burgin, M., & Mikkilineni, R. (2021). On the autopoietic and cognitive behavior. EasyChair Preprint No. 6261, Version https://easychair.org/publications/preprint/tkjk.

- Capps, John, “The Pragmatic Theory of Truth”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2023 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2023/entries/truth-pragmatic .

- Deacon, T. W. (2012). Incomplete nature: How mind emerged from matter. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Deutsch, David. 2011. The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations that Transform the World. Viking, New York.

- Froese, T. (2024). What is “the secret of life”? The mind–body problem in Čapek’s Rossum’s Universal Robots (R.U.R.). In J. Čejková (Ed.), Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. and the vision of artificial life. MIT Press. [CrossRef]

- Froese, Tom. 2023. “Irruption Theory: A Novel Conceptualization of the Enactive Account of Motivated Activity.” Entropy 25 (5): 748. [CrossRef]

- Hill, S. L. (2025a). Fold Theory: A categorical framework for emergent spacetime and coherence [Preprint]. Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/130062788.

- Hill, S. L. (2025b). Fold theory and the dissolution of the graviton [PDF]. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Levin, Michael. 2021. “Bioelectric Signaling as a Control Layer in Morphogenesis.” Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering 23: 353–378.

- Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1980). Autopoiesis and cognition: The realization of the living. D. Reidel Publishing Co.

- Mikkilineni, R. (2022). A New Class of Autopoietic and Cognitive Machines. Information, 13(1), 24. [CrossRef]

- Mikkilineni, R., Kelly, W. P., & Crawley, G. (2024). Digital genome and self-regulating distributed software applications with associative memory and event-driven history. Computers, 13(9), 220. [CrossRef]

- Mikkilineni, R., & Michaels, M. (2025). Physics of Mindful Knowledge. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mikkilineni, R. (2025). General theory of information and mindful machines. Proceedings, 126(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Peirce, C. S. (1878). *”How to make our ideas clear”*. *Popular Science Monthly*, 12(January), 286–302.

- Philosophy Institute. (2023, September 19). *The pragmatic theory of truth: A practical perspective*.

- https://philosophy.institute/epistemology/pragmatic-theory-truth-practical-perspective/.

- Thompson, Evan. 2007. Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of Mind. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Varela, Francisco J., Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch. 1991. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).