1. Introduction

Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1 (HIV-1) remains a critical global health issue, with approximately 38 million people infected and more than 1.5 million new infections annually [

1]. While antiretroviral therapy (ART) has transformed HIV management, it does not eliminate viral reservoirs, and its long-term use is limited by resistance, cumulative toxicity, and unequal accessibility [

2].

A key step in the HIV-1 life cycle is the initial attachment to host cell surfaces before interaction with CD4 and CCR5/CXCR4 co-receptors. According to Connel

et al. 2013 [

3], HIV-1 uses heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) as primary adhesion molecules prior to stabilizing initial contact with target cells. These sulfated glycosaminoglycans act as bridging molecules between gp120 and the cell, enhancing viral affinity for CD4 and co-receptors, promoting efficient entry into the target cells [

4,

5].

The adhesion mechanism of HIV-1 to target cells is well described by studies showing that inhibition or absence of HSPGs significantly reduces HIV-1 infectivity, making this interaction an attractive strategic to target for early viral blockade [

4,

5]. Polyanionic sulfated compounds, such as dextran sulfate, carrageenan, and heparin derivatives, have shown potential to compete with GAGs (group specific antigens) and block viral binding, although clinical efficacy has been limited due to toxicity or inconsistent in vivo results [

2,

6].

In this context, sulfated chitosan microparticles (Chi-S microparticles) emerge as an attractive alternative candidate. Derived from chitosan, a natural cationic polysaccharide, Chi-S microparticles can be chemically modified to incorporate sulfate groups, producing an anionic polymer structurally similar to GAGs [

7]. This modification enables Chi-S microparticles to mimic cellular surfaces, act as a decoy that traps the virus, and competitively interfere with gp120 binding to it receptor CD4 and co-receptors [

4,

5]. Additionally, Chi-S microparticles retain valuable properties such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, mucoadhesion, and low cost [

8,

9].

Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of sulfated chitosan derivatives against various enveloped viruses, including in vitro anti-HIV activity with effective concentrations (EC50) in the range of 1–5 μg/mL, without notable toxicity [

8,

10].

Based on the previous observations and properties of Chi-S particles, it was proposed to evaluate the potential of low molecular weight sulfated chitosan microparticles (LMW Chi-S microparticles) to retain HIV-1 in vitro. Given its heparan sulfate-mimicking mechanism, we hypothesized that LMW Chi-S microparticles would effectively block the early steps of HIV-1 infection, a fundamental and largely unexplored step in the development of topical microbicides for sexual transmission prevention. Initial attachment and entry of HIV-1 are facilitated by interactions with heparan sulfate proteoglycans on the host cellular surfaces [

3,

5]. By designing sulfated chitosan microparticles that structurally and functionally mimic heparan sulfate, this strategy aims to competitively block viral binding sites, reducing the probability of successful cellular entry [

2,

5,

6]. Mechanistically, HIV-1 entry relies on interactions with heparan sulfate proteoglycans present on host cellular surfaces [

3,

5]. Notably, heparan sulfate mimetics have previously been explored as a strategy to block viral infection, further supporting the rationale for this approach [

2,

6]. Thus, the use of sulfated chitosan microparticles is designed to mimic these natural viral receptors, acting as a biomimetic blocking strategy to prevent viral attachment and entry [

7,

8].

2. Results

Characterization of sulfated chitosan Microparticles

The LMW Chi-S microparticles were synthesized according to Bucarey

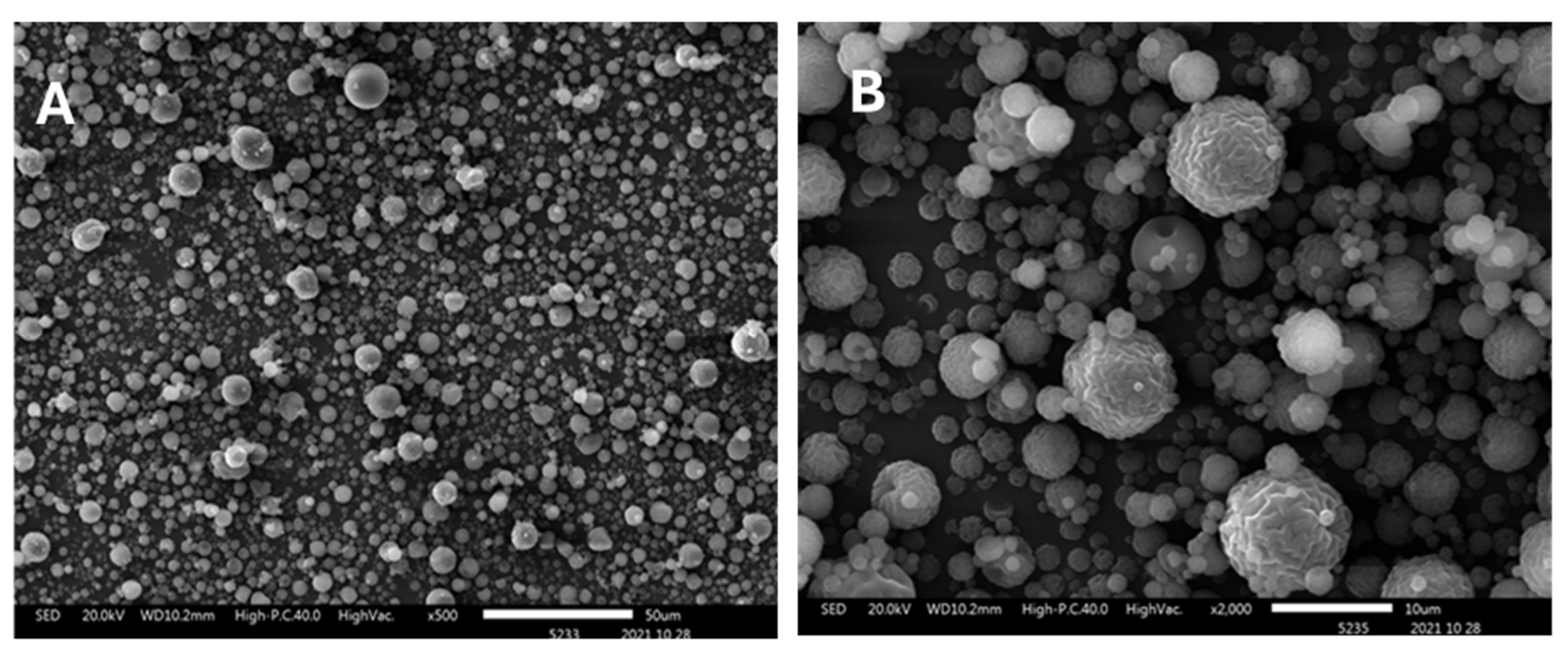

et al. 2022. The physicochemical and morphological characterization was carried out to confirm the integrity and functionality of the particles for viral binding assays. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis confirmed the successful incorporation of sulfate groups into the chitosan backbone, as evidenced by characteristic bands of absorption at 815 and 1218 cm

−1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) revealed a predominantly spherical morphology of microparticles with smooth surface features and a homogeneous size distribution (

Figure 1). The measured diameter ranged approximately from 1 to 5 µm, which optimize effective interaction with viral particles. Additionally, elemental analysis confirmed a sulfur content of approximately 4,5%, supporting the high degree of sulfation achieved during the synthesis (

Table 1).

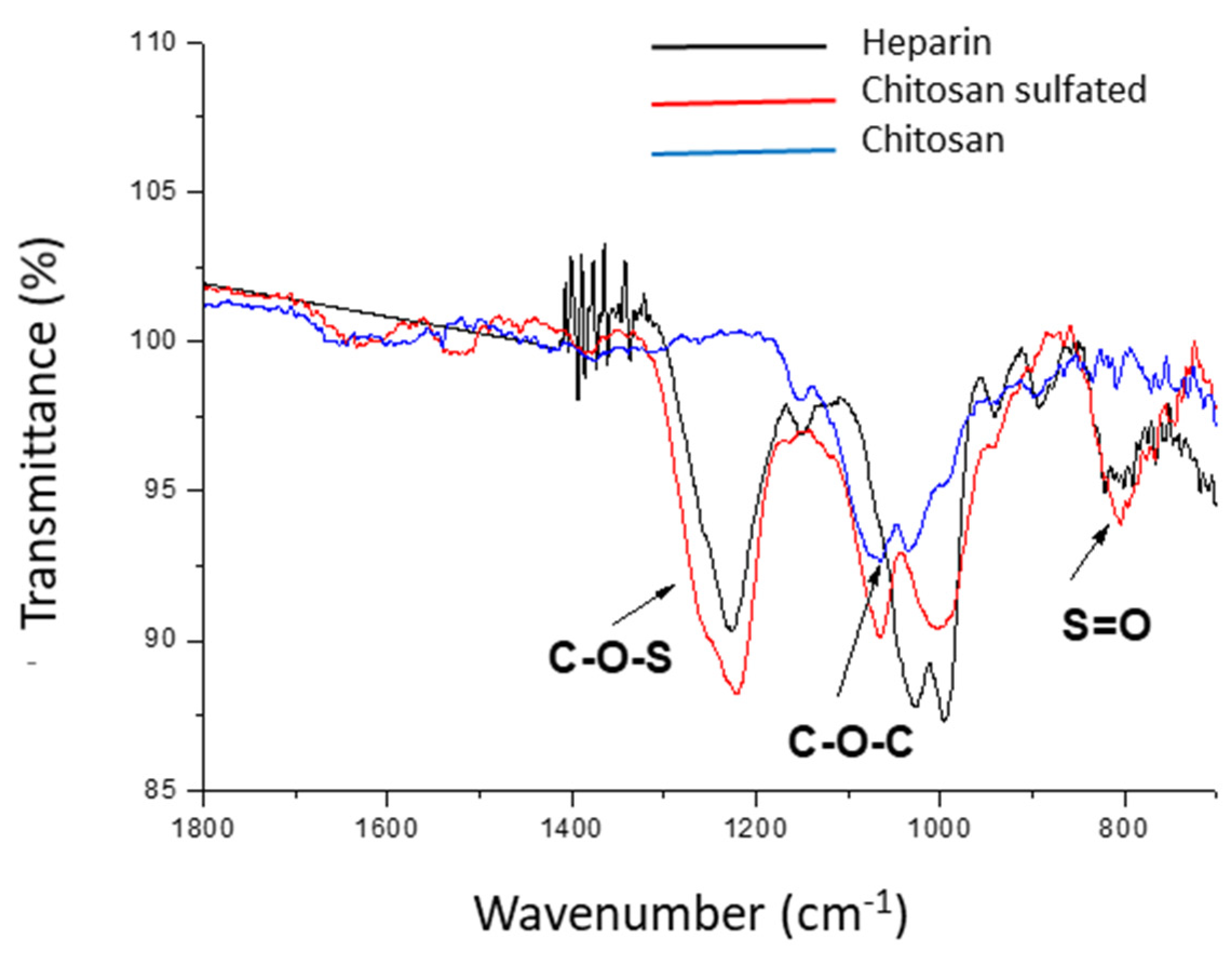

FTIR Spectral Characterization of Sulfated Chitosan (Chi-S)

To confirm the chemical modification of chitosan, we performed Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy on three samples: commercial chitosan, sulfated chitosan (Chi-S), and commercial heparin. The resulting spectra are presented in

Figure 1.

The FTIR profile of commercial chitosan showed characteristic polysaccharide bands, including the broad O–H stretching signal around 3400 cm−1 and the C–O–C skeletal vibration at approximately 1075 cm−1. In contrast, the spectrum of Chi-S revealed additional peaks consistent with the presence of sulfate groups. Notably, an intense absorption band was observed near 1220 cm−1, corresponding to the asymmetric stretching of the S=O bond, and a second peak near 820 cm−1 indicative of C–O–S bending vibrations. These spectral features were absent in the unmodified chitosan. Interestingly, the Chi-S spectrum closely overlapped with that of commercial heparin in the sulfate-associated regions (1220–800 cm−1), supporting the successful sulfation of chitosan and its structural mimicry.

The combined FTIR (

Figure 1), SEM (

Figure 2), and elemental analysis (

Table 1) results validate the reproducibility and structure and integrity of the LMW Chi-S microparticles, confirming their suitability for subsequent functional assays and supporting their proposed biomimetic mechanism.

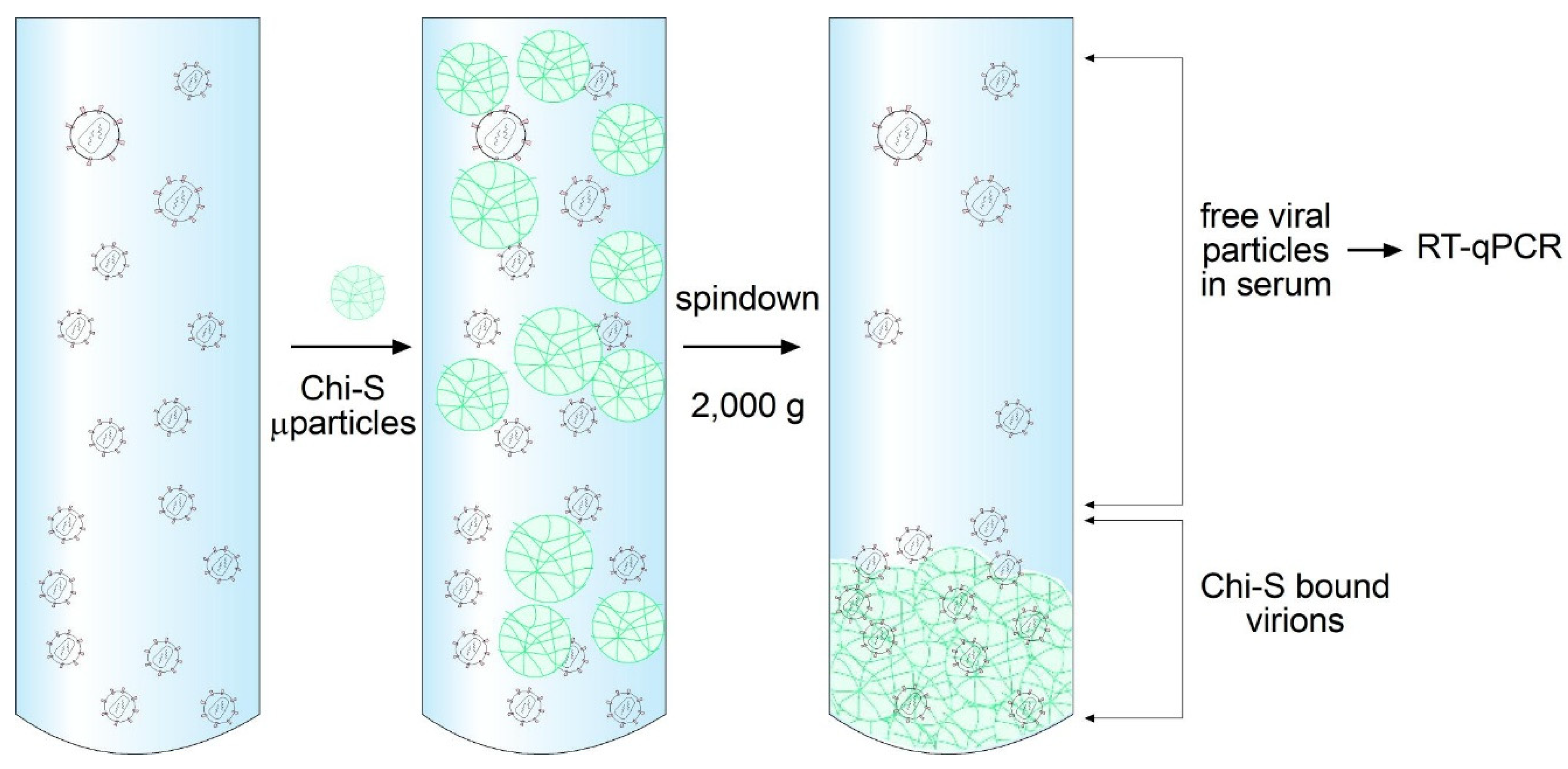

Assessing Viral Binding to LMW Chi-S microparticles

In the initial neutralization experiments, HIV-1 positive plasma samples with high viral loads (3.5 × 10

6 copies/mL, log 6.54) were incubated with LMW Chi-S microparticles at various concentrations. After incubation, samples were pulled down by centrifugation to separate microparticle-bound virus from the supernatant (

Figure 3). Viral RNA quantification in the supernatant was performed using the cobas

® HIV-1 test on the cobas

® 4800 System (Roche), which combines automated sample preparation and real-time PCR analysis. The assay workflow included protease digestion, magnetic glass particle-based nucleic acid capture, extensive washing steps to remove inhibitors, and precise quantification using an Armored RNA internal control standard and external calibrators.

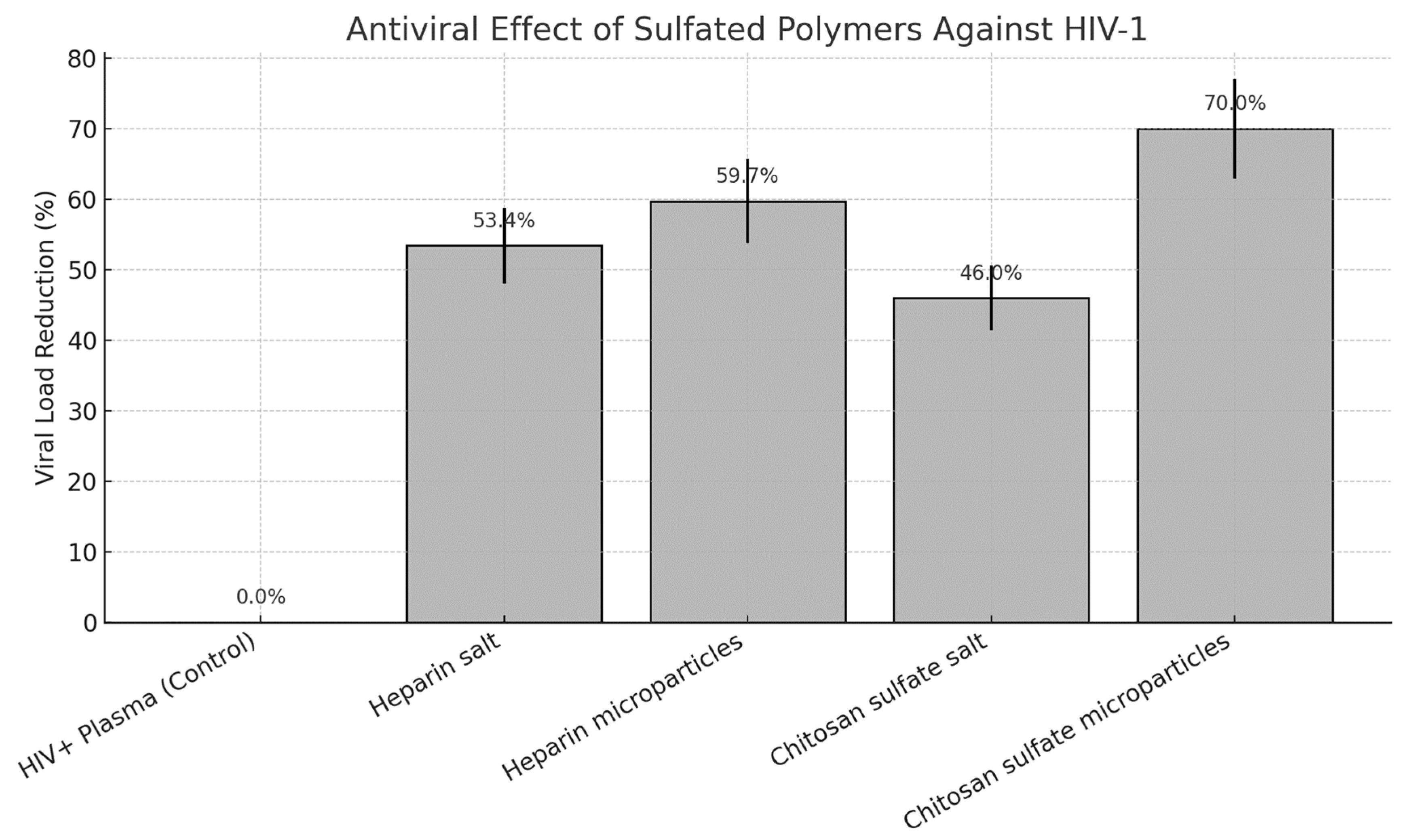

To evaluate the inhibitory effect of sulfated polymers against HIV-1, we conducted a comparative viral neutralization assay using different formulations: soluble heparin, heparin microparticles, chitosan sulfate (Ch-S) salt, and Ch-S microparticles. The untreated HIV+ plasma sample, with a viral load of 3.5 × 10

6 copies/mL, served as the positive control (

Table 2).

All treated samples exhibited a measurable reduction in HIV-1 RNA levels compared to the control. Among them, Ch-S microparticles showed the greatest reduction, achieving a 70% decrease in viral load (± 7.00%), lowering the concentration to 1.05 × 106 copies/mL. Heparin microparticles followed with a 59.71% ± 5.97% reduction, while the soluble form of heparin resulted in a 53.43% ± 5.34% decrease. Chitosan sulfate salt, though less potent than its microparticle formulation, still achieved a 46.00% ± 4.60% reduction in viral copies. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the microparticle format enhances biointeraction via increased surface area and mimetic properties resembling host heparan sulfate proteoglycans.

Figure 4 graphically illustrates these findings, showing a bar plot of the percentage of viral load reduction across treatment groups, including error bars representing the standard deviation (SD). The visual comparison underscores the superior efficacy of Ch-S microparticles in neutralizing HIV-1 under the experimental conditions tested.

This table summarizes the measured viral RNA concentrations (copies/mL), log-transformed values, and the calculated percent reduction in viral load relative to the untreated HIV+ plasma control (3.5 × 106 copies/mL). Standard deviations (± SD) were estimated at 10% of the reduction value for each treatment group. The highest reduction (70% ± 7.00) was observed in the group treated with sulfated chitosan microparticles, supporting their biomimetic decoy effect on early HIV-1 entry.

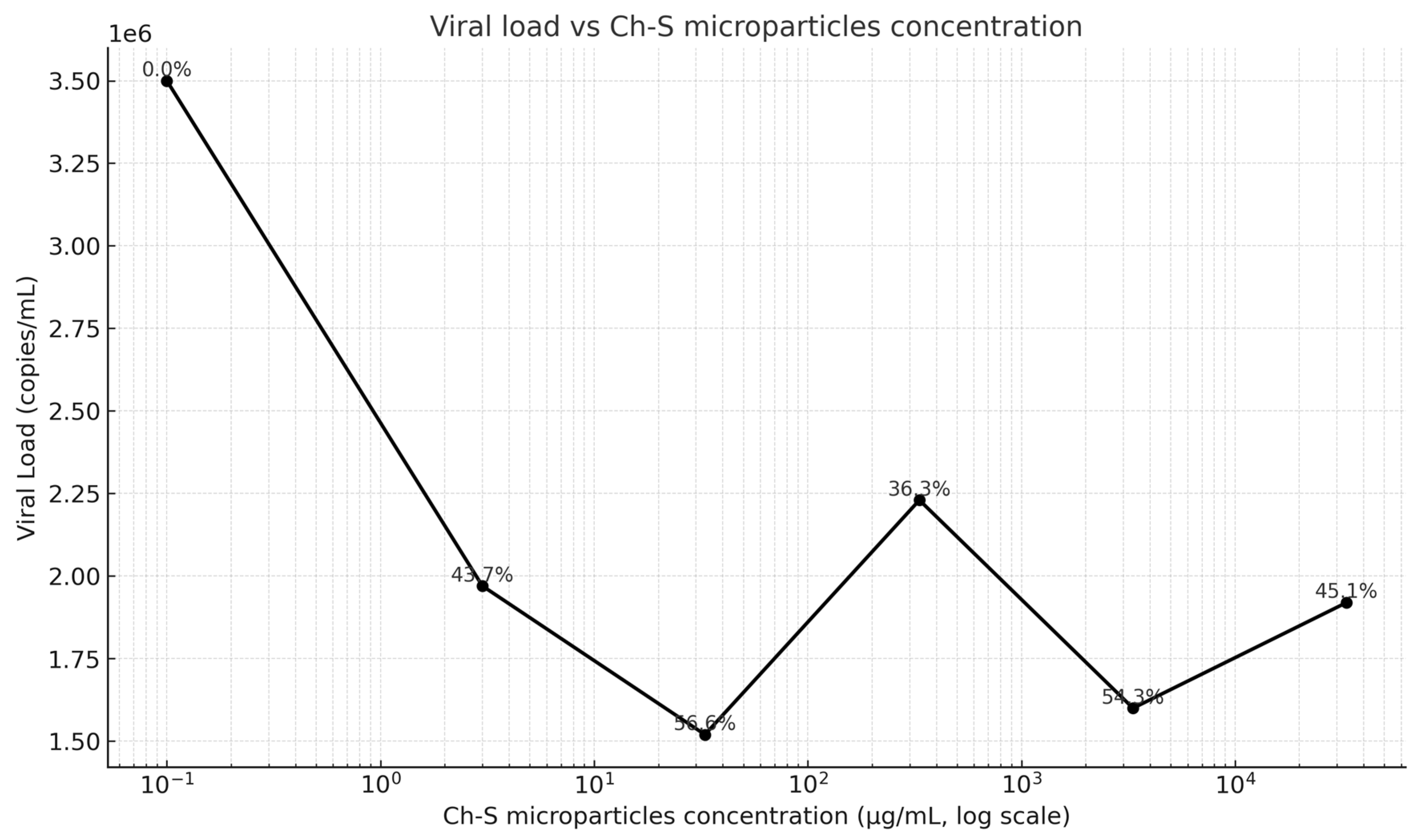

Plasma viral load is reduced by sulfated chitosan microparticles in a non-linear dose-response pattern

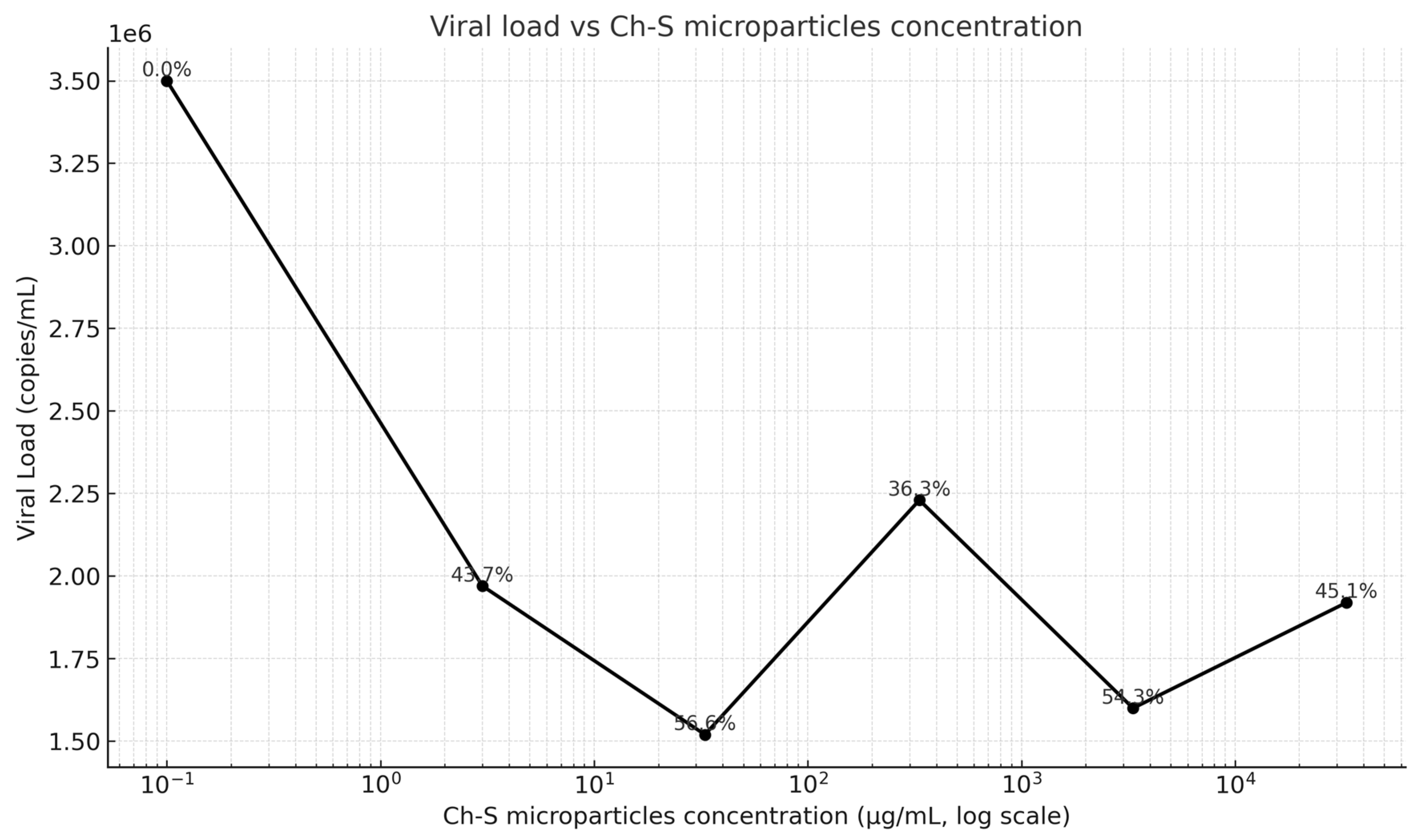

To evaluate the concentration-dependent antiviral activity of low molecular weight sulfated chitosan (Ch-S) microparticles, HIV-1–infected plasma was incubated with serial dilutions ranging from 33,300 to 3 µg/mL. As shown in

Figure 5, all tested concentrations produced a measurable reduction in viral load relative to the untreated control (3.50 × 10

6 copies/mL), although the magnitude of inhibition varied non-linearly across the dose range.

The strongest antiviral effect was observed at 33 µg/mL, where the viral load decreased to 1.52 × 106 copies/mL (56.6% reduction). At lower (3 µg/mL; 1.97 × 106, 43.7% reduction) and higher concentrations (33,300 µg/mL; 1.92 × 106, 45.1% reduction), the inhibitory effect was less pronounced. Intermediate concentrations such as 3,330 µg/mL (1.60 × 106, 54.3% reduction) showed strong but not maximal activity. Interestingly, 333 µg/mL exhibited a relative rebound in viral load (2.23 × 106, 36.3% reduction), indicating that the dose-response does not follow a linear or monotonic pattern.

Collectively, these findings reveal a non-linear, bell-shaped dose-response relationship, with maximal HIV-1 sequestration occurring at an intermediate Ch-S microparticle concentration (33 µg/mL). This suggests the existence of an optimal stoichiometric window for effective viral binding, potentially reflecting multivalent interactions between Ch-S sulfated domains and HIV-1 surface glycoproteins. Further mechanistic studies are required to define the structural and biophysical determinants underlying this concentration-dependent antiviral behavior

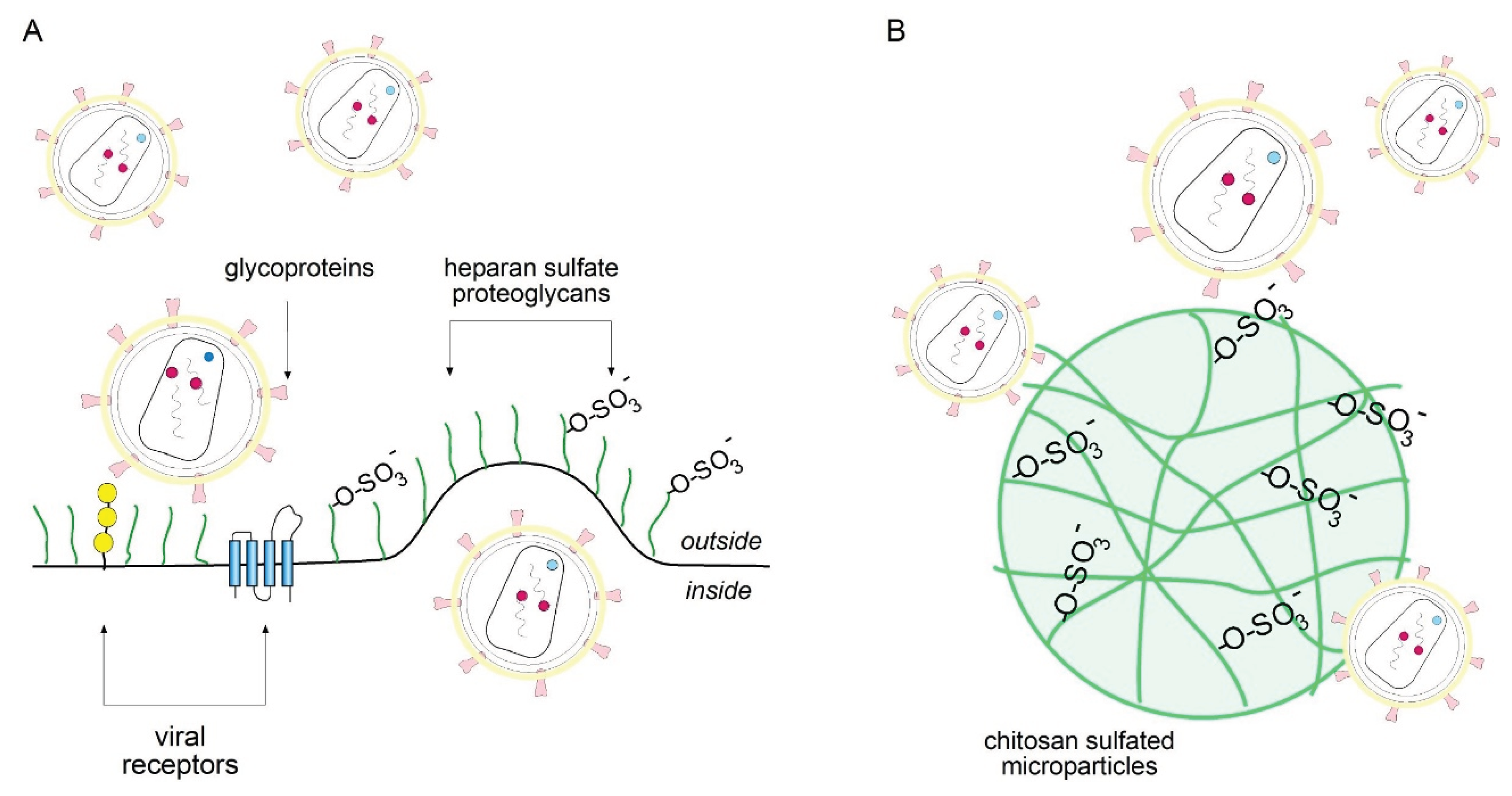

Mechanistic Interpretation and Biomimetic Strategy

Mechanistically, HIV-1 entry relies on interactions with heparan sulfate proteoglycans present on host cell surfaces. Notably, heparan sulfate mimetics have previously been explored as a strategy to block viral infection, further supporting the rationale for this approach. The LMW Chi-S microparticles, through their sulfated and biomimetic surface, act as decoy receptors, effectively trapping and removing viral particles from the plasma. This strategy represents a promising approach to prevent HIV-1 attachment and entry into the cell, reinforcing the potential application of LMW Chi-S microparticles as novel topical microbicide.

Figure 5.

Dose-response effect of sulfated chitosan (Ch-S) microparticles on HIV-1 viral load. Viral load (copies/mL) was quantified after incubating HIV-1–positive plasma with increasing concentrations of Ch-S microparticles (0–33,300 µg/mL). All treatment groups exhibited a reduction in viral load relative to the untreated control (3.5 × 106 copies/mL). The strongest inhibition was obtained at 33 µg/mL, reducing the viral load to 1.52 × 106 copies/mL (56.6% ± 10% SD). Additional antiviral activity was observed at 3 µg/mL (43.7% ± 10% SD), 3,330 µg/mL (54.3% ± 10% SD), 33,300 µg/mL (45.1% ± 10% SD), and 333 µg/mL (36.3% ± 10% SD), although none surpassed the peak response at 33 µg/mL. Data represent mean values from two independent experiments (n = 2). Standard deviation (SD) was estimated at ~10% of the mean, consistent with the expected experimental variability for viral load quantification in plasma-based inhibition assays. Standard error of the mean (SEM) was calculated as SD/√2. Statistical comparisons against the untreated control were performed using two-tailed analyses, with inhibitory effects at 33 µg/mL and 3,330 µg/mL reaching significance (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Dose-response effect of sulfated chitosan (Ch-S) microparticles on HIV-1 viral load. Viral load (copies/mL) was quantified after incubating HIV-1–positive plasma with increasing concentrations of Ch-S microparticles (0–33,300 µg/mL). All treatment groups exhibited a reduction in viral load relative to the untreated control (3.5 × 106 copies/mL). The strongest inhibition was obtained at 33 µg/mL, reducing the viral load to 1.52 × 106 copies/mL (56.6% ± 10% SD). Additional antiviral activity was observed at 3 µg/mL (43.7% ± 10% SD), 3,330 µg/mL (54.3% ± 10% SD), 33,300 µg/mL (45.1% ± 10% SD), and 333 µg/mL (36.3% ± 10% SD), although none surpassed the peak response at 33 µg/mL. Data represent mean values from two independent experiments (n = 2). Standard deviation (SD) was estimated at ~10% of the mean, consistent with the expected experimental variability for viral load quantification in plasma-based inhibition assays. Standard error of the mean (SEM) was calculated as SD/√2. Statistical comparisons against the untreated control were performed using two-tailed analyses, with inhibitory effects at 33 µg/mL and 3,330 µg/mL reaching significance (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Mechanism of HIV-1 inhibition by sulfated chitosan microparticles. (A) HIV-1 attachment to the host cell surface is mediated by electrostatic interactions between viral envelope glycoproteins and negatively charged heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) on the host membrane, facilitating subsequent engagement with viral receptors. (B) Sulfated chitosan (Ch-S) microparticles mimic the negative charge distribution of HSPGs via exposed sulfate groups (–OSO3−), acting as decoy ligands that competitively bind HIV-1 glycoproteins. This prevents viral attachment to host cells and promotes virion sequestration by the microparticles, contributing to a reduction in effective viral load.

Figure 6.

Mechanism of HIV-1 inhibition by sulfated chitosan microparticles. (A) HIV-1 attachment to the host cell surface is mediated by electrostatic interactions between viral envelope glycoproteins and negatively charged heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) on the host membrane, facilitating subsequent engagement with viral receptors. (B) Sulfated chitosan (Ch-S) microparticles mimic the negative charge distribution of HSPGs via exposed sulfate groups (–OSO3−), acting as decoy ligands that competitively bind HIV-1 glycoproteins. This prevents viral attachment to host cells and promotes virion sequestration by the microparticles, contributing to a reduction in effective viral load.

3. Discussion

Our study demonstrates that LMW Ch-S microparticles can efficiently bind and remove HIV-1 from plasma samples in vitro through a direct particle-trapping mechanism. This strategy differs fundamentally from conventional antiviral assays based on cellular infection, p24 antigen release, or metabolic readouts, because the activity of Ch-S microparticles is driven by physical sequestration rather than intracellular inhibition [

11]. The microparticles act as biomimetic “virus sinkers,” capturing HIV-1 particles and enabling their removal during pull-down, consistent with the known affinity of sulfated polysaccharides for viral glycoproteins.

The comparative assays showed that LMW Ch-S microparticles outperform classical heparinoid formulations. While soluble heparin, heparin microparticles, and Ch-S salt reduced viral load by 53.4%, 59.7%, and 46.0%, respectively, the synthesized Ch-S microparticles achieved a markedly higher 70.0% reduction, confirming a superior multivalent binding capacity. This enhanced performance suggests that the spatial sulfation pattern and particulate architecture of Ch-S produce a more effective viral capture interface than heparin-based materials.

Evaluation across multiple Ch-S microparticle concentrations further revealed a non-linear dose–response profile. All tested concentrations reduced viral load relative to the control (3.5 × 106 copies/mL), but the magnitude of inhibition varied. The strongest effect occurred at 33 µg/mL, which decreased viral load to 1.52 × 106 copies/mL (56.6% reduction). Other concentrations produced moderate reductions ranging from 36% to 54%, including 3,330 µg/mL (54.3%), 33,300 µg/mL (45.1%), 3 µg/mL (43.7%), and 333 µg/mL (36.3%). This bell-shaped response suggests that optimal inhibition occurs within a specific concentration window, likely reflecting the balance between particle aggregation, available binding domains, and viral accessibility.

Together, these results demonstrate that LMW Ch-S microparticles possess a strong, dose-responsive, and mechanistically distinct antiviral activity, validating their potential as a nanoparticle-based microbicide platform targeting early HIV-1 entry.

The detailed physicochemical characterization of the microparticles supports their structural integrity and functionality. FTIR analysis confirmed the successful incorporation of sulfate groups, essential for mimicking heparan sulfate interactions [

7]. The spectrum of LMW Chi-S microparticles exhibited characteristic absorption bands corresponding to S=O symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations and are consistent with the FTIR profile of heparin, further supporting the structural analogy and validating the heparan sulfate-mimicking hypothesis. This close spectral resemblance underscores the ability of the sulfated chitosan microparticles to function as decoy receptors by structurally imitating natural glycosaminoglycans on host cell surfaces.

SEM analysis demonstrated that the LMW Chi-S microparticles exhibit a predominantly spherical morphology with smooth, uniform surface features. The size distribution ranged from 1 to 10 µm, a range considered optimal for enhancing interaction with viral particles in suspension due to increased surface area-to-volume ratio [

9] (Xu et al., 2019). The homogeneous particle size and shape contribute to more predictable and reproducible binding efficiency, as larger or highly irregular particles can result in uneven interactions or steric hindrance effects [

12].

Moreover, elemental analysis revealed a sulfur content of approximately 4,56%, indicating a high degree of sulfation achieved during synthesis. This high sulfation level is critical for replicating the negative charge density characteristic of natural heparan sulfate and heparin [

13]. The presence of sulfate groups on the microparticle surface enhances electrostatic interactions with the positively charged domains on HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins (gp120), facilitating stronger and more specific binding [

5]. Together, these morphological and chemical attributes validate the microparticles’ design as effective biomimetic decoys, providing a robust foundation for their use as a novel antiviral microbicide platform, which can be functionalized and engineered to target specific pathogens.

The viral RNA quantification protocol, performed using the cobas

® HIV-1 test on the cobas

® 4800 System, provided robust and reproducible measurements of free viral RNA in the supernatant [

14]. The integration of magnetic glass particle-based nucleic acid capture and real-time PCR detection enhances assay sensitivity and reproducibility, further validating the observed reductions in viral load.

Compared to other polyanionic inhibitors, such as carrageenans or dextran sulfates, LMW Chi-S microparticles offer notable advantages, including superior biocompatibility, biodegradability, and lower cytotoxicity [

6,

10]. Their sulfated surface enables them to act as decoy receptors that competitively inhibit HIV-1 binding to natural heparan sulfate proteoglycans on host cell surfaces [

4,

5]. Notably, heparan sulfate mimetics have previously been explored as antiviral agents against HIV-1 and other enveloped viruses, further supporting the rationale for this strategy [

15,

16,

17,

18]. HIV-1 entry relies on initial interactions with heparan sulfate proteoglycans,facilitating subsequent engagement with CD4 and co-receptors [

19]. By mimicking these natural receptors, LMW Chi-S microparticles effectively block the first step of viral attachment and entry, reducing the likelihood of successful infection.

Future research should include ex vivo studies using human mucosal tissues to evaluate efficacy under physiological conditions [

20]. Moreover, developing formulations such as gels, films, or nanoparticles could enhance delivery, stability, and user acceptability, advancing this technology toward clinical translation [

21].

Overall, our findings introduce LMW Chi-S microparticles as a promising, innovative strategy to physically bind and remove HIV-1 from biological fluids. The validated synthesis route, protected under US Patent No. 11,246,839 B2 [

22] , supports technical reproducibility and positioning this technology as a strong candidate for future preventive microbicide applications

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis of Sulfated Chitosan (Ch-S) Microparticles

Low molecular weight chitosan (LMW Chi; 50–190 kDa) (Sigma-Aldrich™), was used as the starting polymer. Sulfation was performed following the protocol described in Bucarey et al., US Patent No. 11,246,839 B2 (2022) [

22]. Briefly, chitosan was dissolved in 1% acetic acid to obtain a homogeneous solution. Sulfuric acid was then added dropwise to the chitosan mixture under continuous stirring at ~60 °C, and the reaction was allowed to proceed for several hours to ensure sulfation of amino and hydroxyl groups along the polymer backbone.

Upon completion, the reaction mixture was neutralized with cold ethanol to precipitate the sulfated product. The resulting pellet was collected by centrifugation at 3,500 × g for 15 min and sequentially washed with ethanol and deionized water to remove unreacted reagents. The purified sulfated chitosan was subsequently lyophilized to obtain a dry powder.

Microparticles were produced by resuspending the lyophilized Ch-S powder in 1% PBS followed by spray-dry atomization using a Büchi Mini Spray Dryer B-290. All reagents were of analytical grade, and all solutions were prepared using fresh ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm; LaboStar™ TWF or LaboStar™ 4-DI/UV systems, Evoqua Water Technologies, USA).

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) of the resulting Ch-S material was conducted using an ATR/FT-IR Interspec 200-X spectrometer (Interspectrum OU, Toravere, Estonia) to confirm characteristic sulfation signatures

4.2. Morphostructural and Elemental Characterization

Morphostructural and elemental analyses of the sulfated chitosan (Ch-S) microparticles were performed using a scanning electron microscope (JEOL JSM-IT300LV, Pleasanton, CA, USA) equipped with an X-ray energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) detector at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Chile. Ch-S microparticle samples were mounted on aluminum stubs and sputter-coated with a thin layer of gold according to previously described procedures [

23], in order to optimize surface conductivity and image resolution. SEM imaging was used to evaluate particle morphology, surface topology, and size distribution, while EDS allowed verification of the elemental composition associated with sulfation. All measurements were conducted under high-vacuum conditions, and representative micrographs were collected from multiple fields to confirm structural homogeneity.

4.3. Virus Binding Assay

To evaluate the viral sequestration capacity of the different sulfated polymer formulations, a standardized polymer–virus binding assay was performed. A total of 250 µL of HIV-1–positive plasma (3.5 × 106 copies/mL; log 6.54) was mixed with 750 µL of each polymer suspension prepared at 10 mg/mL. The polymers tested included:

(1) heparin salt,

(2) heparin microparticles,

(3) sulfated chitosan salt (Ch-S salt), and

(4) low-molecular-weight sulfated chitosan microparticles (LMW Ch-S MPs) synthesized and characterized as described above. Each mixture was gently homogenized and incubated at 30°C for 2 hours under continuous agitation to facilitate polymer–virus interactions. Following incubation, samples were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to sediment polymer–virus complexes, allowing physical separation of bound viral particles from unbound virions remaining in solution.

The supernatant was carefully collected without disturbing the pellet and subsequently analyzed for residual HIV-1 RNA using quantitative RT-qPCR following standard diagnostic procedures as described bellow. The measured viral RNA corresponded to the fraction of unbound, non-captured virus, and was used to quantify the antiviral binding performance of each polymer. All conditions were processed in duplicate (n = 2 independent experiments), and results were normalized to the untreated plasma control

4.4. HIV-1 Viral Load Quantification Protocol

HIV-1 RNA quantification was performed using the cobas® HIV-1 test (version 1.3) on the cobas® 4800 System (Roche), following the manufacturer's instructions. The system includes the cobas x 480 instrument for sample preparation and the cobas z 480 analyzer for real-time PCR amplification and detection.

Plasma samples were processed with automatic extraction and purification of viral nucleic acids. Proteinase and lysis reagents were added to release viral RNA, which then bound to the silica surface of magnetic glass particles. Unbound substances and impurities (such as proteins, cell debris, and PCR inhibitors) were removed through sequential washing steps. Purified RNA was eluted at elevated temperature using elution buffer.

For quantification, an Armored RNA quantitation standard (RNA QS) was spiked into each sample as an internal control to monitor extraction and amplification efficiency. The essay also included three external controls: high-titer positive control, low-titer positive control, and negative control (non-reactive human plasma).

Quantification results were reported as not detected, <LLoQ (lower limit of quantification), >ULoQ (upper limit of quantification), or as within the linear range (LLoQ ≤ x ≤ ULoQ). Data were automatically analyzed and interpreted by the system software, with results available on the system display and exportable for reporting.

4.5. Dose-Response Assay

The dose–response effect of low molecular weight sulfated chitosan (Ch-S) microparticles on HIV-1 viral load was evaluated by incubating HIV-1–positive plasma with increasing concentrations of Ch-S microparticles. Serial dilutions spanning the full working range (0–33,300 µg/mL) were prepared in sterile conditions and mixed with equal volumes of high–viral-load plasma obtained from HIV-1–positive donors. Each condition was processed in duplicate (n = 2 independent experiments).Following incubation, samples were centrifuged to allow particle–virus complex formation and sedimentation. The supernatants were collected and viral load (copies/mL) was quantified by real-time RT-qPCR using standard clinical diagnostic protocols. Viral load from untreated plasma was used as the reference control for normalization.

Experimental variability was monitored by calculating the standard deviation (SD), which was estimated at approximately 10% of the mean values, consistent with expected fluctuations in plasma-based viral load assays. The standard error of the mean (SEM) was derived as SD/√2. Statistical comparisons between treated and untreated samples were performed using two-tailed analyses, with significance defined as p < 0.05

4.6. Reagents

PBS wa obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Gibco) (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Heparin sodium salt from porcine intestinal mucosa (Cat. H4784) was adquired from Merck (Rahway, New Jersey, USA). Heparin Sepharose microparticles was obatained from GE Healthcare (Chicago, IL, USA). Sulfated chitosan microparticles were prepared for this study.