Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

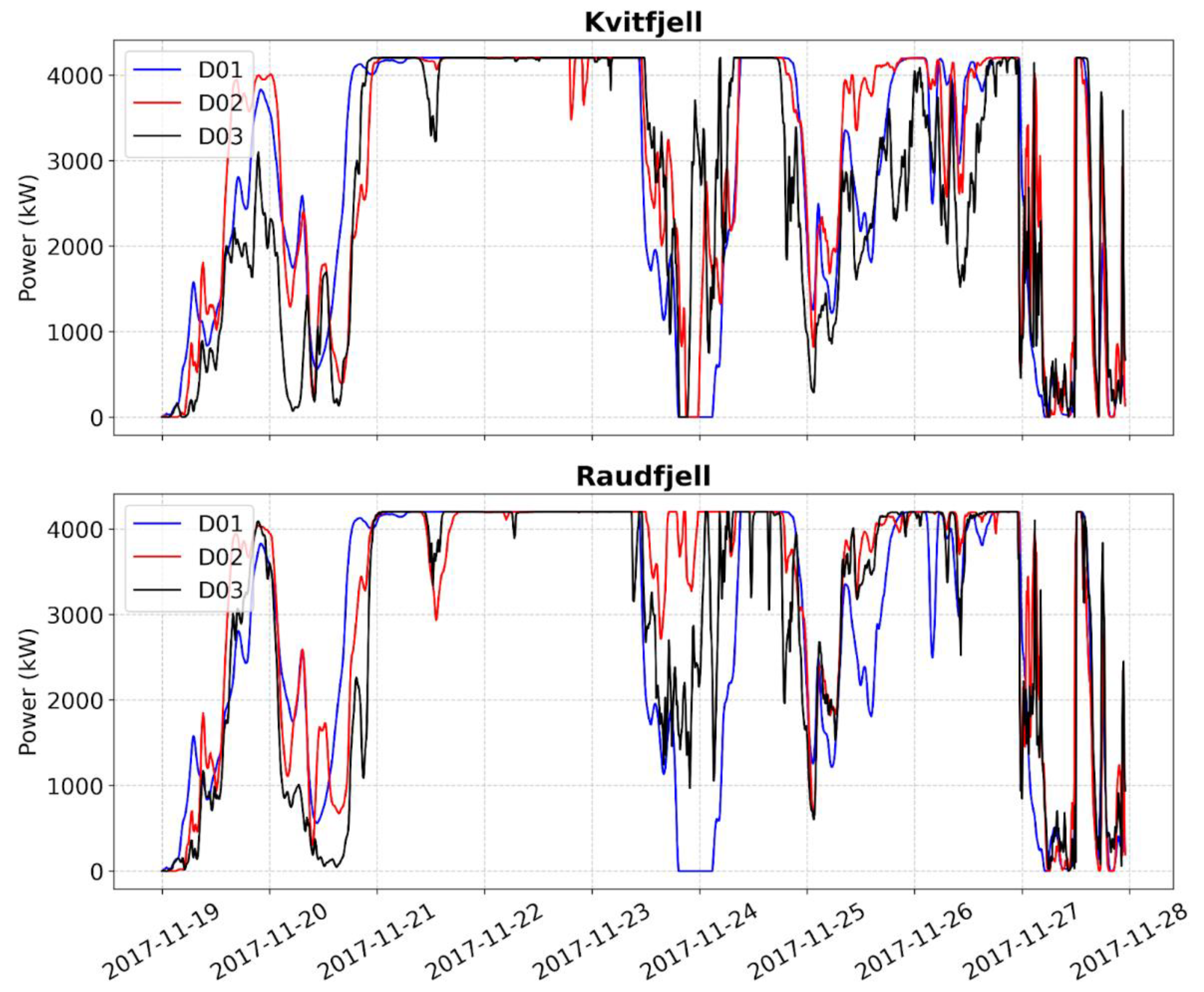

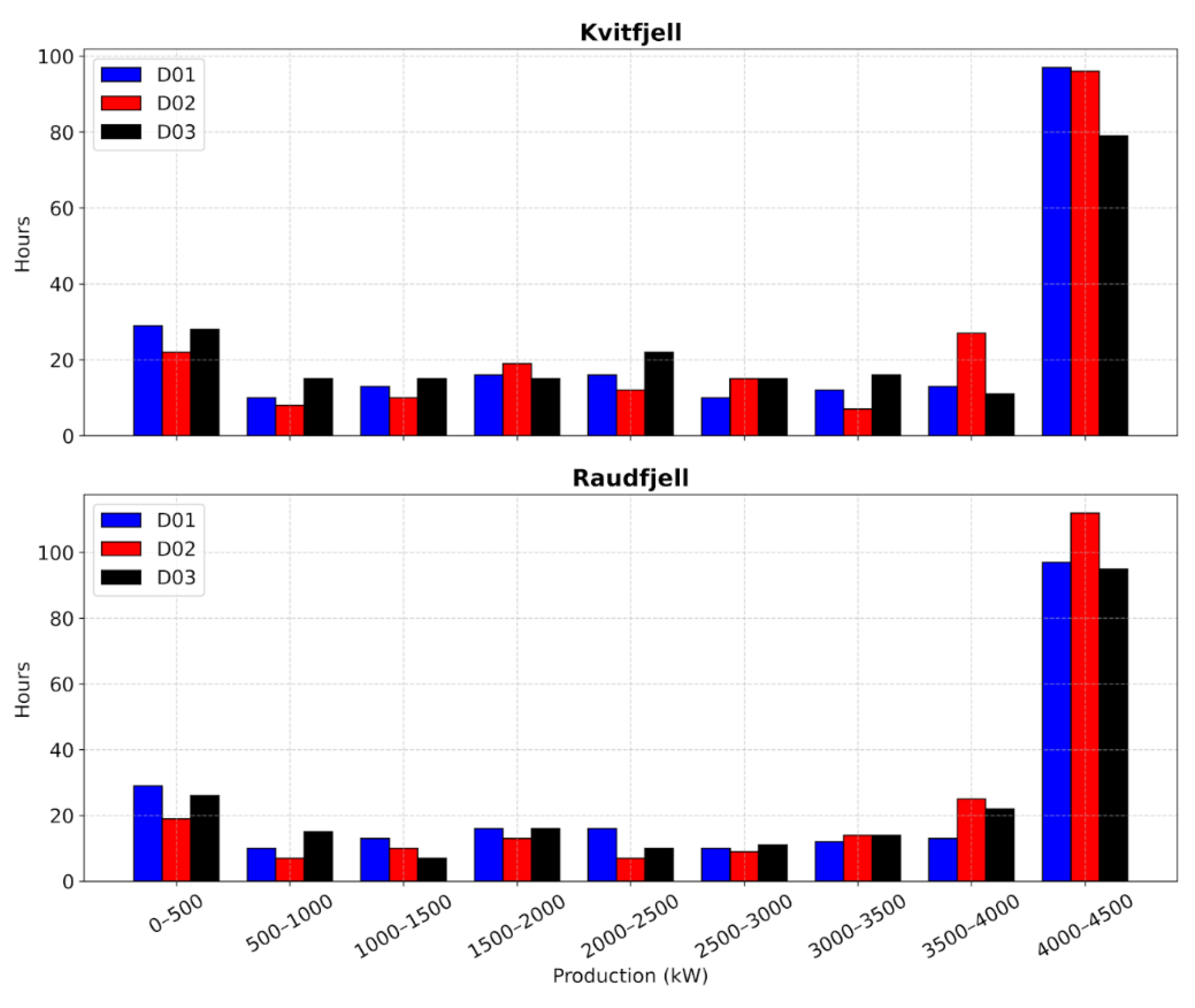

Wind energy has the potential to become an important source of energy for remote Arctic regions. However, there are risks associated with the exposure of coastal wind parks to extremely strong winds caused by storms and polar lows. Extreme winds can either enhance or reduce wind energy production. The outcomes largely depend on the coastal landscape surrounding the wind park. To address these questions, we conducted a series of simulations using the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model. This study focuses on one of the strongest wind events along the western Norwegian coast - the landfall of the storm “Ylva” (November 24–27, 2017). The study employs terrain-resolving downscaling by zooming in on the area of the Kvitfjell-Raudfjell wind park, Norway. The terrain-resolving WRF simulations reveal stronger winds at turbine hub height (80 m to 100 m above the ground level) in the coastal area. However, it was previously overlooked that the landfall of an Atlantic storm, which approaches this area from the southwest, brings the strongest winds from southeast directions, i.e., from the land. This creates geographically extensive and vertically deep wind-sheltered areas along the coast. Wind speeds at hub height in these sheltered areas are reduced, while they remain extreme over wind-channeling sea fjords. The study demonstrates that optimal wind park siting can take advantage of both sustained westerly winds during normal weather conditions and wind sheltering during extreme storm conditions. We found that the Kvitfjell-Raudfjell location is nearly optimal with respect to the extreme winds of “Ylva.”

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Extreme Weather System (Storm) “Ylva”

2.2. The Study Site: Kvitfjell-Raudfjell Wind Park

2.3. Datasets

2.4. Statistical Methods for Wind Climate Evaluation

2.5. Configuration of the WRF Model

3. Results

3.1. Landfall of “Ylva”: Evolution of Winds in Models

3.2. Intercomparison of Models and Observations at Selected Sites

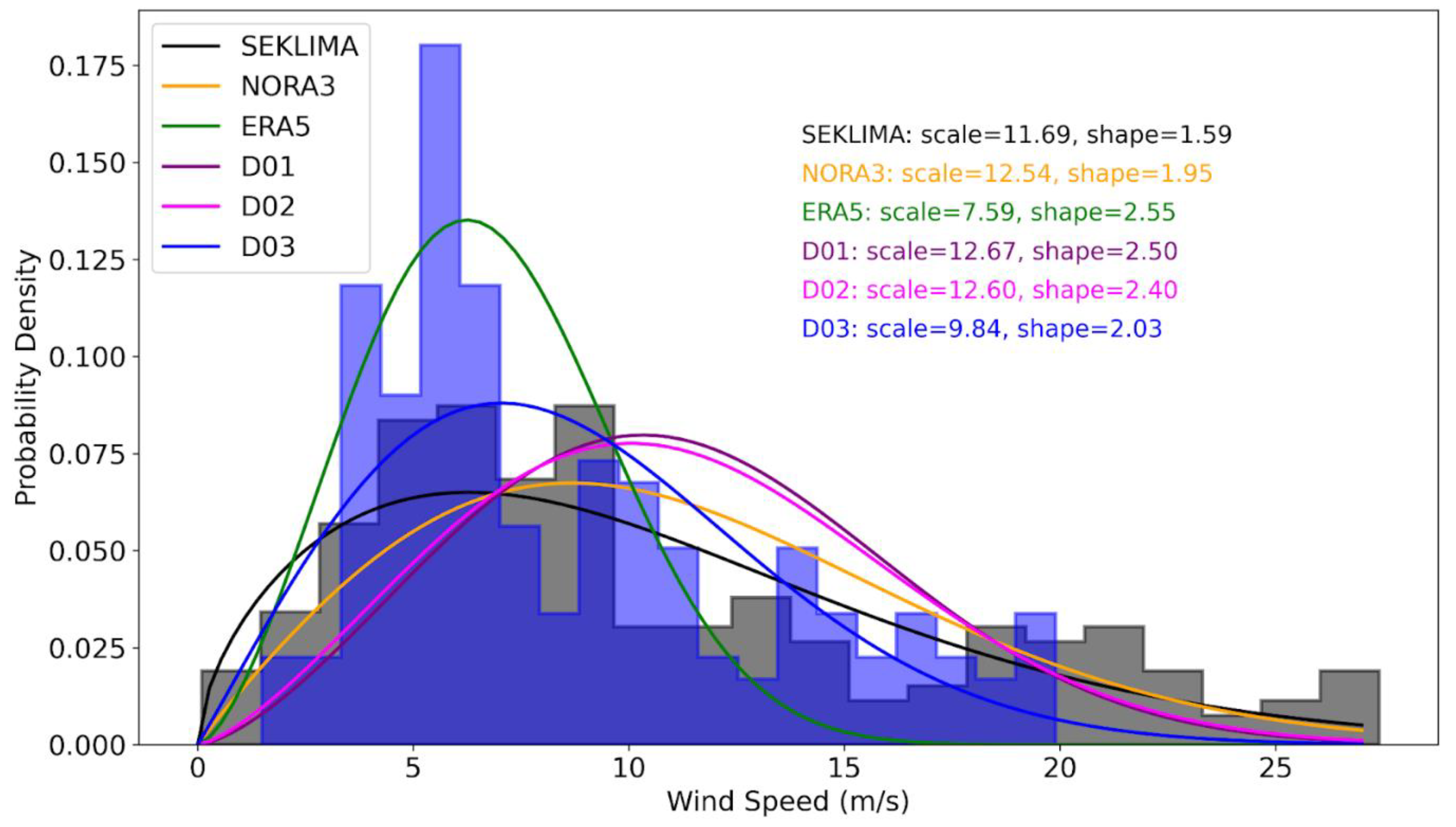

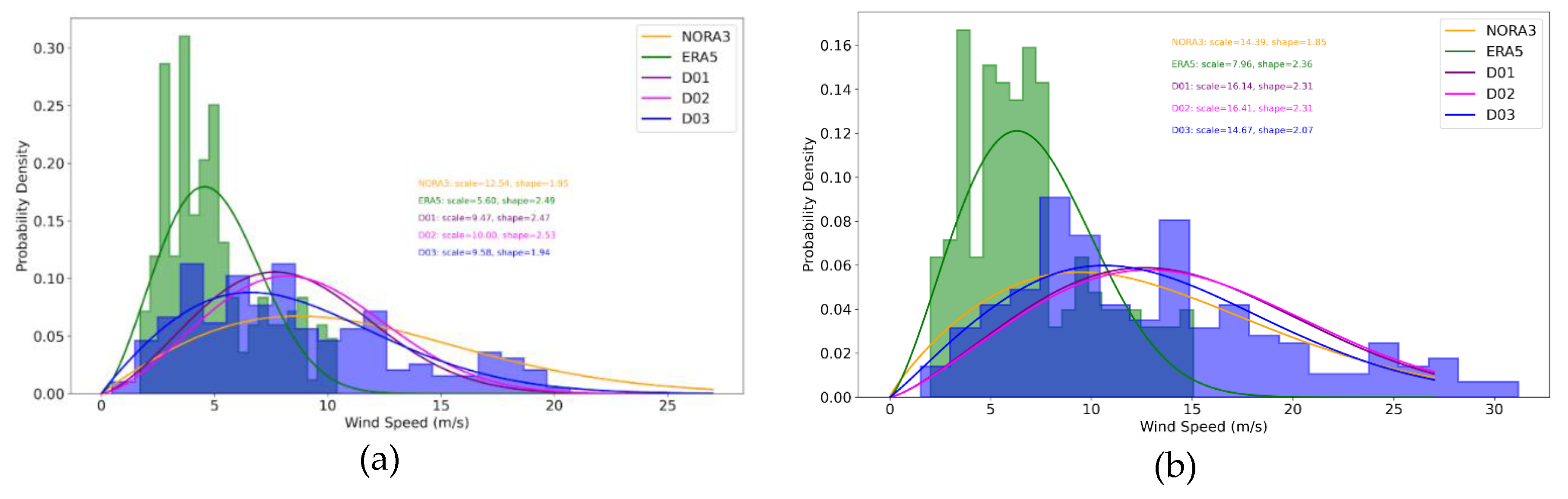

3.3. Comparative Statistical Analysis of Winds

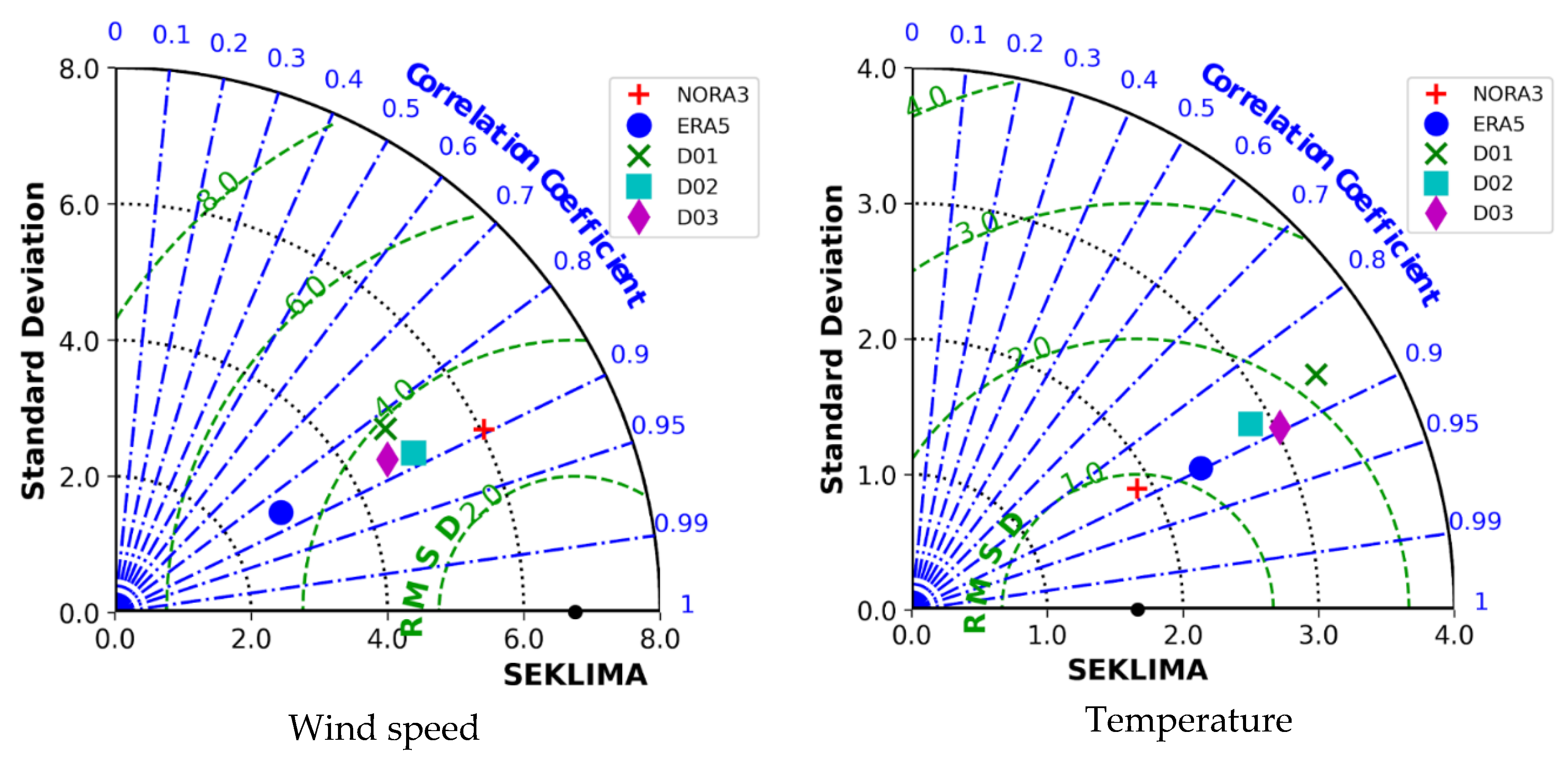

3.4. Assessment of the Model Simulations Against Direct Observations

4. Discussion

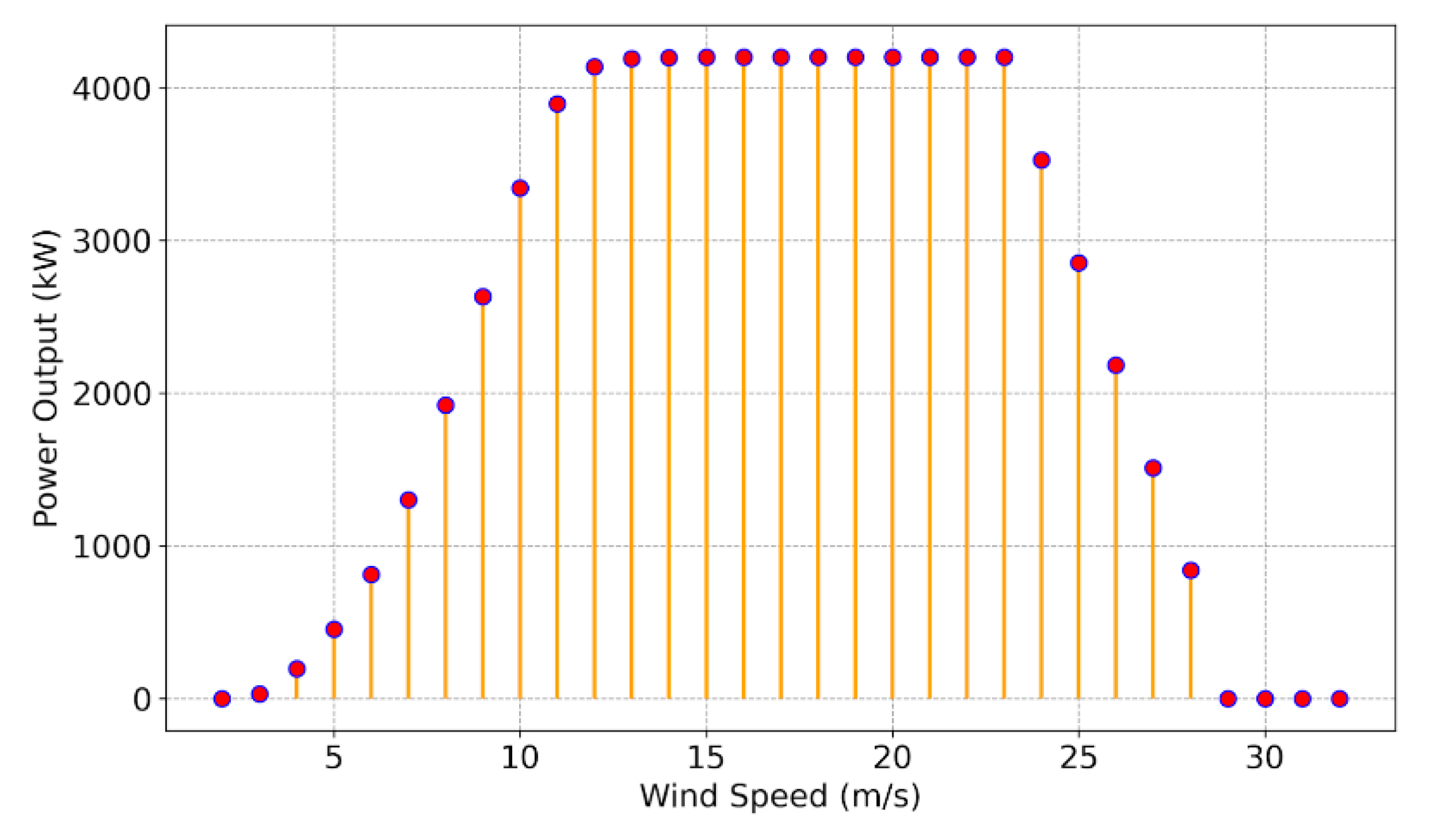

4.1. The “Ylva” Impact on Wind Power Production

4.2. Sheltering from Extreme Winds Along the Norwegian West Coast

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WRF | Weather Research and Forecasting model |

| NORA3 | NORwegian Reanalysis Archive with a 3 km resolution |

| ERA5 | European center for medium and long-term weather forecast Reanalysis version 5 |

| SEKLIMA | Observations and analysis archive of the Norwegian Meteorological Institute |

References

- Clifton, A.; Barber, S.; Stökl, A.; Frank, H.; Karlsson, T. Research challenges and needs for the deployment of wind energy in hilly and mountainous regions. Wind Energy Sci. 2022, 7(6), 2231–2254. [CrossRef]

- Pryor, S.C.; Barthelmie, R.J. A global assessment of extreme wind speeds for wind energy applications. Nature Energy 2021, 6(3), 268–276. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Tao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yan, J.; Zeng, Z. Increasing extreme winds challenge offshore wind energy resilience. Nature Comms. 2025, 16(1), 9529. [CrossRef]

- Christakos, K.; Varlas, G.; Reuder, J.; Katsafados, P.; Papadopoulos, A. Analysis of a low-level coastal jet off the Western coast of Norway. Energy Procedia 2014, 53(C), 162–172. [CrossRef]

- Solbrekke, I.M.; Sorteberg, A. Norwegian offshore wind power—Spatial planning using multi-criteria decision analysis. Wind Energy 2024, 27, 5–32. [CrossRef]

- Enevoldsen, P.; Permien, F.-H.; Bakhtaoui, I.; Krauland, A.-K.; Jacobson, M.Z.; and 5 co-authors. How much wind power potential does Europe have? Examining European wind power potential with an enhanced socio-technical atlas. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 1092–1100. [CrossRef]

- Minola, L.; Azorin-Molina, C.; Guijarro, J.A.; Zhang, G.; Son, S.; Chen, D. Climatology of Near-Surface Daily Peak Wind Gusts Across Scandinavia: Observations and Model Simulations. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 2021, 126(7). [CrossRef]

- Katsaprakakis, D. Al.; Papadakis, N.; Ntintakis, I. A Comprehensive Analysis of Wind Turbine Blade Damage. Energies 2021, 14(18), 5974. [CrossRef]

- Simensen, T.; Erikstad, L.; Halvorsen, R. Diversity and distribution of landscape types in Norway. Norwegian J. Geography 2021, 75(2), 79–100. [CrossRef]

- Grønås, S.; Sandvik, A.D. Numerical simulations of local winds over steep orography in the storm over north Norway on October 12, 1996. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 1999, 104(D8), 9107–9120. [CrossRef]

- Nawri, N.; Harstveit, K. Variability of surface wind directions over Finnmark, Norway, and coupling to the larger-scale atmospheric circulation. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2012, 107(1–2), 15–33. [CrossRef]

- Solbakken, K.; Birkelund, Y.; Samuelsen, E.M. Evaluation of surface wind using WRF in complex terrain: Atmospheric input data and grid spacing. Env. Mod. Soft. 2021, 145, 105182. [CrossRef]

- Henkies, M.; Høyland, K.V.; Shestov, A.; Duscha, C.; Sjöblom, A. The Arctic Fjord Breeze: Characteristics of a Combined Sea Breeze and Valley Wind in a Svalbard Fjord Valley. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 2023, 189(1–3), 281–304. [CrossRef]

- Feser, F.; Barcikowska, M.; Krueger, O.; Schenk, F.; Weisse, R.; Xia, L. Storminess over the North Atlantic and northwestern Europe—A review. QJRMS 2015, 141, 350–382. [CrossRef]

- Jaison, A.; Sorteberg, A.; Michel, C.; Breivik, Ø. Assessment of wind–damage relations for Norway using 36 years of daily insurance data. Nat. Haz. Earth Sys. Sci. 2024, 24(4), 1341–1355. [CrossRef]

- Solbrekke, I.M.; Sorteberg, A.; Haakenstad, H.The 3 km Norwegian reanalysis (NORA3)-a validation of offshore wind resources in the North Sea and the Norwegian Sea. Wind Energy Sci. 2021, 6(6), 1501–1519. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wu, D.; Wu, K.; Yu, K.; Zheng, C. Interdecadal Variation Trend of Arctic Wind Energy. Energies 2023, 16(18), 6545. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Esau, I. Determining the ideal length of wind speed series for wind speed distribution and resource assessment, Wind Energ. Sci. Discuss. 2025 [preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Wais, P. A review of Weibull functions in wind sector. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 1099–1107. [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Birkelund, Y.; Homola, M.; Virk, M.S. Wind over complex terrain – Microscale modelling with two types of mesoscale winds at Nygårdsfjell. Renewable Energy, 2016, 99, 647–653. [CrossRef]

- Birkelund, Y. Numerical Weather Modelling and Large Eddy Simulations of Strong-Wind Events in Coastal Mountainous Terrain. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15(14), 7683. [CrossRef]

- Hølleland, S.; Berentsen, G.D.; Otneim, H.; Solbrekke, I.M. Optimal allocation of 30 GW offshore wind power in the Norwegian economic zone. Wind Energy Sci. 2025, 10(1), 293–313. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-González, S.; Martín, M.L.; García-Ortega, E.; Merino, A.; Lorenzana, J.; Sánchez, J.L.; Valero, F.; Rodrigo, J.S. Sensitivity Analysis of the WRF Model: Wind-Resource Assessment for Complex Terrain. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2018, 57, 733–753. [CrossRef]

- Luzia, G.; Hahmann, A.N.; Koivisto, M.J. Evaluating the mesoscale spatio-temporal variability in simulated wind speed time series over northern Europe. Wind Energy Sci. 2022, 7(6), 2255–2270. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.; Rocha, A.; Gómez-Gesteira, M.; Silva Santos, C. Sensitivity of the WRF model wind simulation and wind energy production estimates to planetary boundary layer parameterizations for onshore and offshore areas in the Iberian Peninsula. Appl. Energy 2014, 135, 234–246. [CrossRef]

- Solbakken, K.; Samuelsen, E.M.; Birkelund, Y. Mountain wave and downslope winds impact on wind power production. Wind Energy Sci. 2025, (preprint. [CrossRef]

- Onwukwe, C.; Jackson, P.L. Meteorological Downscaling with WRF Model, Version 4.0, and Comparative Evaluation of Planetary Boundary Layer Schemes over a Complex Coastal Airshed. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2020, 59(8), 1295–1319. [CrossRef]

- Powers, J.G.; Klemp, J.B.; Skamarock, W.C.; Davis, C.A.; Dudhia, J.; and 23 co-authors. The Weather Research and Forecasting Model: Overview, System Efforts, and Future Directions. BAMS 2017, 98(8), 1717–1737. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, I.-T.; Vassbø, T.; Nordhagen, R.; Fossli, I.; Straume, I.; Mamen, J.; Haugen, G. Ekstremværrapport Ylva 22. -24. November 2017, MET.NO 2018, report 15-18, 23 p., Tromsø, ISSN 2387-4201 (available online https://www.met.no/publikasjoner/met-info/met-info-2018/_/attachment/download/23168252-dba3-48a5-bd6b-42601ee5e38a:9aeff6d74147f57dfae2dfa12650b1376a90dcd5/MET-info-15-2018.pdf last accessed 11 September 2024).

- NRK (2017) available from https://www.nrk.no/nordland/_ylva_-odela-for-150-millioner_-_-trodde-ikke-skadeomfanget-ble-sa-stort-1.13809430, last access 21.10.2025.

- Nordlysvid: https://nordlysvind.no/project-information/overview/, last accessed November 6, 2024.

- SVW (2019). The Raudfjell and Kvitfjell wind farm is operating, available on https://svw.no/en/insights/the-raudfjell-and-kvitfjell-wind-farm-is-operating last access 2025-11-26.

- Soci, C.; Hersbach, H.; Simmons, A.; Poli, P.; Bell, B.; and 11 co-authors. The ERA5 global reanalysis from 1940 to 2022. QJRMS 2024, 150(764), 4014–4048. [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.M.; Cohen, L.; Ritzhaupt, N.; Segger, B.; Graversen, R.G.; Rinke, A.; Walden, V.P.; Granskog, M.A.; Hudson, S.R. Evaluation of Six Atmospheric Reanalyses over Arctic Sea Ice from Winter to Early Summer. J. Clim. 2019, 32(14), 4121–4143. [CrossRef]

- Ramon, J.; Lledó, L.; Torralba, V.; Soret, A.; Doblas-Reyes, F.J. What global reanalysis best represents near-surface winds? QJRMS 2019, 145(724), 3236–3251. [CrossRef]

- Gandoin, R.; Garza, J. Underestimation of strong wind speeds offshore in ERA5: evidence, discussion and correction. Wind Energy Sci. 2024, 9(8), 1727–1745. [CrossRef]

- Haakenstad, H.; Breivik, Ø.; Furevik, B.R.; Reistad, M.; Bohlinger, P.; Aarnes, O.J. NORA3: A Nonhydrostatic High-Resolution Hindcast of the North Sea, the Norwegian Sea, and the Barents Sea. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2021, 60(10), 1443–1464. [CrossRef]

- Khachatrian, E.; Asemann, P.; Zhou, L.; Birkelund, Y.; Esau, I.; Ricaud, B. Exploring the Potential of Sentinel-1 Ocean Wind Field Product for Near-Surface Offshore Wind Assessment in the Norwegian Arctic. Atmos. 2024, 15(2). [CrossRef]

- al Oqaily, D.; Giani, P.; Crippa, P. Evaluating WRF Multiscale Wind Simulations in Complex Terrain: Insights From the Perdigão Field Campaign. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos., 2025, 130(15). [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.E. Summarizing multiple aspects of model performance in a single diagram. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 2001, 106(D7), 7183–7192. [CrossRef]

- Skamarock, W.C.; Klemp, J.B.; Dudhia, J.; Gill, D.O.; Liu, Z.; and 7 co-authors. A Description of the Advanced Research WRF Model Version 4. National Center for Atmospheric Research. 2021.

- Dörenkämper, M.; Olsen, B.T.; Witha, B.; Hahmann, A.N.; Davis, N.N.; and 13 co-authors. The Making of the New European Wind Atlas – Part 2: Production and evaluation. Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13(10), 5079–5102. [CrossRef]

- Cheynet, E.; Diezel, J.M.; Haakenstad, H.; Breivik, Ø.; Peña, A.; Reuder, J. Tall wind profile validation of ERA5, NORA3, and NEWA datasets using lidar observations. Wind Energy Sci. 2025, 10(4), 733–754. [CrossRef]

- Hasager, C.B.; Hahmann, A.N.; Ahsbahs, T.; Karagali, I.; Sile, T.; Badger, M.; Mann, J. Europe’s offshore winds assessed with synthetic aperture radar, ASCAT and WRF. Wind Energy Sci. 2020, 5(1), 375–390. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Cao, L.; Li, S.; Zhan, C.; Wang, J.; Zhao, T. Comprehensive sensitivity analysis of the WRF model for meteorological simulations in the Arctic. Atmos. Res. 2024, 299, 107200. [CrossRef]

- Wickström, S.; Jonassen, M.O.; Vihma, T.; Uotila, P. Trends in cyclones in the high-latitude North Atlantic during 1979–2016. QJRMS 2020, 146(727), 762–779. [CrossRef]

- Antonini, E.G.A.; Virgüez, E.; Ashfaq, S.; Duan, L.; Ruggles, T.H.; Caldeira, K. Identification of reliable locations for wind power generation through a global analysis of wind droughts. Communications Earth & Env. 2024, 5(1), 103. [CrossRef]

- NRIS: https://www.uio.no/english/services/it/research/hpc/fram/ last accessed November 6, 2024.

- Wolf-Grosse, T.; Esau, I.; Reuder, J. Sensitivity of local air quality to the interplay between small- and large-scale circulations: a large-eddy simulation study. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17(11), 7261–7276. [CrossRef]

| WRF configuration | D01 | D02 | D03 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal resolution | 9 km | 3 km | 1 km |

| Number of horizontal plain grid points | 97 x 97 | 97 x 97 | 97 x 97 |

| Number of vertical levels | 51 | 51 | 51 |

| Time step | 30 s | 10 s | 3.3 s |

| Sampling interval | 10 min | 10 min | 10 min |

| WRF component | Configuration option |

|---|---|

| Initial and boundary conditions | For D01 from ERA5; D02 from D01; D03 from D02 |

| Domain D01 extent | Longitude: |

| Latitude: | |

| Planetary boundary layer scheme | MYNN 2.5-level TKE |

| Land surface scheme | Noah land surface model |

| Radiation (short-wave and long-wave) scheme | The Rapid Radiative Transfer Model for global circulation (RRTMG) |

| Cumulus cloud scheme | Kain-Fritsch (new Eta) |

| Microphysics scheme | The Thompson scheme with cloud water, cloud ice, snow, graupel, and rain |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).