1. Introduction

Isoniazid (INH) remains foundational to Tuberculosis (TB) therapy, yet its chemical behaviour and exposure profiles can be fragile under real-world handling and patient factors. Computational and mechanistic analyses indicate that INH is prone to reaction pathways (e.g., hydrazone formation and hydrolysis/oxidation routes) that may be triggered or accelerated by formulation environment and processing conditions [

1]. Clinically, INH pharmacokinetics in children show substantial variability, raising the risk of sub-therapeutic concentrations during routine care [

2]. Comparable concerns have been documented in adults, where INH pharmacokinetics measured under programmatic conditions have been linked with treatment outcomes, underscoring the clinical importance of maintaining adequate exposure [

3]. Together, these strands motivate a closer examination of how bedside manipulation and multi-drug co-suspension influence INH integrity and dissolution, issues that can masquerade as microbial resistance rather than formulation-driven failure.

Paediatric tuberculosis management continues to be hampered by the scarcity of stable, child-appropriate dosage forms. In many resource-limited settings, clinical staff or caregivers crush adult tablets and prepare aqueous co-suspensions before dosing. While this offers flexibility, it introduces risks such as chemical degradation, altered dissolution, and reduced bioavailability. This is particularly problematic in children, where sub-therapeutic exposure may drive treatment failure and resistance.

Paediatric TB therapy often relies on the bedside practice of crushing adult tablets and preparing ad hoc aqueous mixtures, which can alter solid-state order, supramolecular interactions, and dissolution. Isoniazid (INH) is susceptible to hydrolysis and carbonyl-driven reactions with reducing excipients; it is also polymorphic, with crystalline forms that may interconvert under such stress. This work investigates how grinding and multi-drug co-suspension affect INH thermal responses, vibrational band signatures, and dissolution, and interprets the findings using a correlative supramolecular framework whilst acknowledging potential polymorphic contributions.

Isoniazid is central to first-line and preventive TB therapy, but it is highly formulation-dependent. When tablets are crushed and mixed with food or common vehicles, the hydrazide can react with reducing sugars and other excipients, promoting hydrazone formation, hydrolysis, and oxidative loss of the active drug [

4]. These manipulation-driven pathways lower dissolution and assayable INH, making the delivered dose unpredictable and sub-therapeutic despite correct nominal dosing [

4]. In practice, such formulation failure can mimic “INH resistance”, confounding clinical decisions unless the preparation is controlled or avoided [

4]. Recent reviews on anti-mycobacterial drug stability underline how degradation during sample handling, storage, or formulation manipulation can compromise assay and therapeutic integrity [

5]. Drug-excipient and drug-drug interactions within multi-component systems are increasingly recognised to influence crystallinity, solubility, and decomposition pathways [

6].

Supramolecularly, the ordered hydrogen-bonding and π–π stacking interactions within crystalline INH underpin its stability in solid form. Disruption of these interactions by mechanical stress, an aqueous medium, or contact with other molecules can promote structural reorganisation, amorphisation, or the formation of new intermolecular complexes [

7]. Such changes may reinforce accelerated degradation or hinder dissolution in manipulated formulations.

Reformulating an immediate-release tablet into an apparent immediate-release suspension is therefore not a trivial conversion. Although both dosage forms are designed for rapid drug release, their physicochemical and supramolecular environments differ substantially. In a tablet, the crystalline INH is stabilised by compression and low molecular mobility, protecting the hydrazide moiety from hydrolysis. Once dispersed in water, however, the hydrated and dynamic environment promotes hydrogen-bond competition, lattice disruption, and accelerated degradation. Designing an effective paediatric suspension thus requires deliberate control of pH, ionic strength, and excipient compatibility to maintain both rapid release and molecular stability.

Here, a systematic approach is mimicked by interrogating how grinding and co-suspension of INH with companion TB drugs affect its supramolecular organisation, thermal stability, spectroscopic signature, and dissolution behaviour. By coupling orthogonal analytical techniques, the aim was to elucidate the molecular underpinnings of degradation and guide future paediatric formulation design that ensures immediate release without loss of chemical integrity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Branded isoniazid tablets (Winthrop, South Africa; excipients include lactose monohydrate, maize starch, magnesium stearate) and additional brands were donated by the Desmond Tutu TB Centre (Stellenbosch University, South Africa). All samples were stored aseptically at 20 ± 2 °C, with batch numbers and expiry dates recorded. Isoniazid raw material (batch AB0600) was supplied by Sanofi, Paris, France. All samples were stored aseptically at 20 ± 2 °C, with batch numbers and expiry dates recorded.

2.2. Sample Preparation

For INH-only testing, a single 100 mg INH tablet was ground in a porcelain mortar and pestle for 5 min and transferred into glass poly-top vials.

For the multi-drug combination mixture (MCM), the dosing reflected that of a 4-year-old child weighing 20 kg: INH 400 mg, pyrazinamide (PZA) 800 mg (Macleods Pyrazinamide 500 SA), ethambutol (EMB) 500 mg (Sandoz Ethambutol 400 mg), ethionamide (ETH) 400 mg (Ethatyl 250 mg (Sanofi-Aventis)), levofloxacin (LEV) 400 mg (Austell Levofloxacin 250 mg / 500 mg (Austell Labs)), and terizidone (TER) 400 mg (Terizidone Macleods 250 mg Capsules (Macleods)). Corresponding tablets/capsules were crushed/emptied and ground for 5 min, then divided as follows: (i) MCM (dry) stored as ground powder; and (ii) MCS (suspension), to which 5 mL of distilled water was added immediately before analysis. The 5 mL water volume approximates bedside manipulation practice, and suspensions were analysed within 10 min of reconstitution.

2.3. Thermal Analyses

Hot-stage microscopy (HSM) was performed using an Olympus microscope equipped with a Linkam SZX7 heating stage, 25 °C to 400 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min⁻¹. Images and interpretations around 190–200 °C correspond to melt/degradation transitions rather than physiological conditions; physiological behaviour was assessed by dissolution at 37 °C.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted on a PerkinElmer TGA 4000 using 3–5 mg samples, heated at 5 °C min⁻¹ to 400 °C under nitrogen at 40 mL min⁻¹.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was conducted on a PerkinElmer DSC 8000 with integrated cooling. Samples (3–5 mg) were sealed in aluminium pans and analysed at 5 °C min⁻¹ to 400 °C under nitrogen at 20 mL min⁻¹.

2.4. Raman Spectroscopy

Spectra were acquired on an Anton Paar Cora 5700 system equipped with a 1064 nm laser. Branded tablets, ground tablets, MCM, and MCS samples were analysed, using 10 accumulations × 20 s per measurement.

2.5. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

FTIR-ATR spectra were acquired on a PerkinElmer Spectrum 400 with an ATR accessory, 4 cm⁻¹ resolution, air as background, and no hydraulic press was used owing to the ATR configuration, over 4000–650 cm⁻¹. For suspension interrogation, MCS was briefly refluxed (~10 min), vacuum-filtered (Rocker 300®), and scanned by ATR.

2.6. Dissolution Testing

Dissolution was performed using a SOTAX Smart System (USP Apparatus I, rotating basket) with 900 mL media: pH 1.2 prepared as 0.01 N HCl and pH 6.8 USP buffer, at 37 ± 0.5 °C, 100 rpm. Test units included: INH API in hard-gelatin capsules (size 0) filled using Cap.M.Quick™ and weighed on a Mettler Toledo AJ100®; intact tablets; ground tablets; and MCS (5 mL). USP Apparatus I was used for both capsules and tablets to maintain consistent hydrodynamics across formulations. Samples were withdrawn at 10, 20, 30, 45, and 60 min, filtered through 0.45 µm nylon membranes validated for >98% INH recovery, and replaced with pre-warmed medium.

Although some profiles exhibited an upward trajectory near 60 min, testing was limited to 60 min to comply with the USP immediate-release specification (≥ 80 % release in 45 min) and to prevent late-phase oxidative degradation that can confound interpretation.

This timeframe captures the clinically relevant dissolution phase for bedside formulations; extending beyond 60 min would not enhance mechanistic understanding and risks secondary degradation artefacts.

2.7. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

Quantitative analysis of INH was performed using a Knauer Azura HPLC system equipped with a Phenomenex Kinetex C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm). The mobile phase comprised 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (NaH₂PO₄, pH 6.8): methanol in a 70:30 v/v ratio, delivered at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Detection was set at 238 nm, shown to be specific for INH without matrix interference via blank matrix scans; the injection volume was set at 10 µL injection volume. Calibration was linear over the range 0.005–72.00 mg/mL (r² = 0.9997). The method was validated for specificity, linearity (0.005–72.00 mg mL⁻¹; r² = 0.9997), accuracy, precision (intra-/inter-day %RSD < 2%), and LOD/LOQ (LOD 0.0015 mg mL⁻¹; LOQ 0.005 mg mL⁻¹) in accordance with ICH Q2(R2). A single INH-selective method was intentionally applied across matrices because the study aimed to quantify INH rather than multiple analytes.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test was applied using GraphPad Prism v8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA); p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Thermal Behaviour

HSM (

Figure 1) showed: (a) the INH API melted sharply between ~173 - 175 °C, consistent with literature values (b) Ground branded INH tablets softened earlier (~120 °C) and exhibited progressive darkening between 195 - 240 °C, whereas (c) MCM began melting between ~170 - 175 °C, with bubbling and matrix collapse by 190 °C. These depressed melting onsets reflect a breakdown of INH’s native supramolecular lattice due to mechanical stress and interstitial incorporation of other molecules.

TGA curves showed a multi-stage % mass loss; the onset temperatures followed the order: INH API (181.4 °C) > ground tablet (173.3 °C) > MCM (156.9 °C). The progressive decline suggests increasing heterogeneity and destabilisation of molecular interactions (

Figure 2).

The DSC curve (

Figure 2) showed the INH API exhibiting a clean endotherm (~171.6 °C) and a broad event at 240–270 °C. The ground-branded tablet displayed attenuated, shifted peaks (~146–170 °C) and an exotherm (~210 °C). MCM lacked resolvable transitions, consistent with amorphous or overlapping supramolecular domains. Overall, thermal blurring indicates loss of long-range order and emergence of new interactions—hallmarks of disrupted supramolecular structure.

Grinding and co-suspension lowered the melting temperature and broadened transitions, signifying reduced crystallinity and enhanced molecular disorder. These findings suggest supramolecular disruption and possible polymorphic transformation.

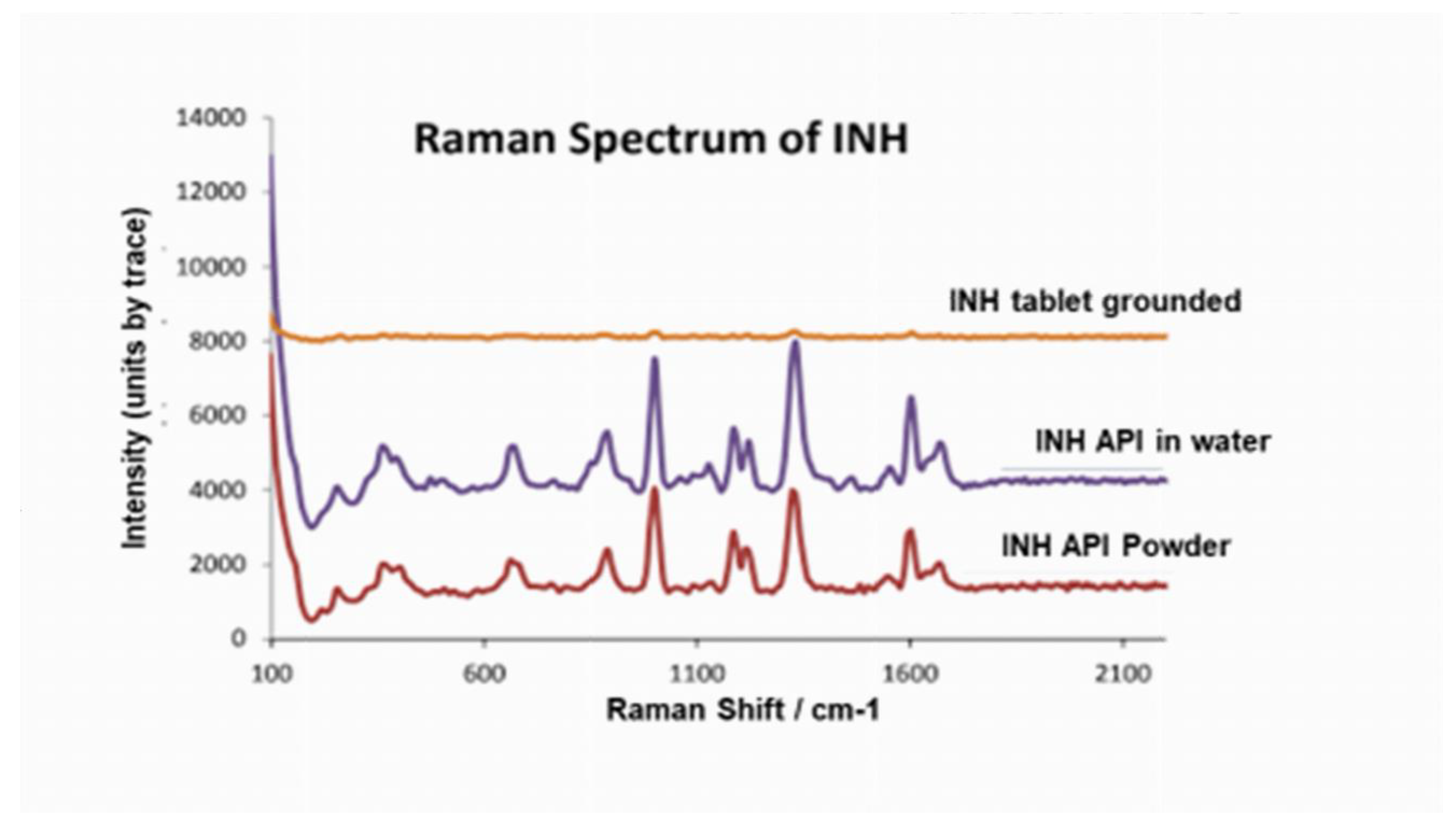

3.2. Raman Spectroscopy

The INH API spectrum featured sharp bands assignable to pyridine, amide, and ring modes. After grinding and aqueous suspension, bands in the OH/NH region broadened, and the pyridine-ring peaks weakened or shifted. These spectral alterations imply the formation of new hydrogen-bond networks between INH molecules and excipients or co-drugs, replacing original intramolecular and intermolecular interactions. Such band broadening reflects competitive hydrogen-bonding between INH and excipients and supports the thermal data.

Figure 3.

Raman spectra of INH API, INH API in water and INH tablet grinded spectra.

Figure 3.

Raman spectra of INH API, INH API in water and INH tablet grinded spectra.

Table 1.

Raman functional groups identified from INH API, INH API in water and INH tablet grinded spectra.

Table 1.

Raman functional groups identified from INH API, INH API in water and INH tablet grinded spectra.

| |

Region

(cm-1)

|

Functional group |

| INH API |

3300 |

υ(C-H) |

| |

2220 – 2255 |

υ(C~N) |

| |

1500 – 1900 |

υ(C=C) |

| |

1400 - 1470 |

δ(CH2)

δ(CH3) |

| |

480 – 660 |

υ(C-I) |

| |

10 – 200 |

Lattice vibrations in crystals, LA modes |

| INH API in water |

550 – 800 |

υ(C-Cl) |

| |

630 – 790 |

υ(C-Cl) aliphatic |

| |

480 - 660 |

υ(C-I) |

| |

250 - 400 |

δ(CC) aliphatic chains |

| |

230 - 550 |

υ(S-S) |

| |

10 – 200 |

Lattice vibrations in crystals, LA modes |

| INH tablet grinded |

|

|

| |

1500- 1900 |

υ(C=C) |

| |

1380 |

δ(CH3) |

| |

600 – 1300 |

Alicyclic, aliphatic chain vibration |

| |

480 - 660 |

υ(C-I) |

| |

150 - 450 |

υ(Xmetal – O) |

| INH tablet ground with water |

10 – 200 |

Lattice vibrations in crystals, LA modes |

| |

150 – 450 |

υ(Xmetal-O) |

| |

10 – 200 |

Lattice vibrations in crystals, LA modes |

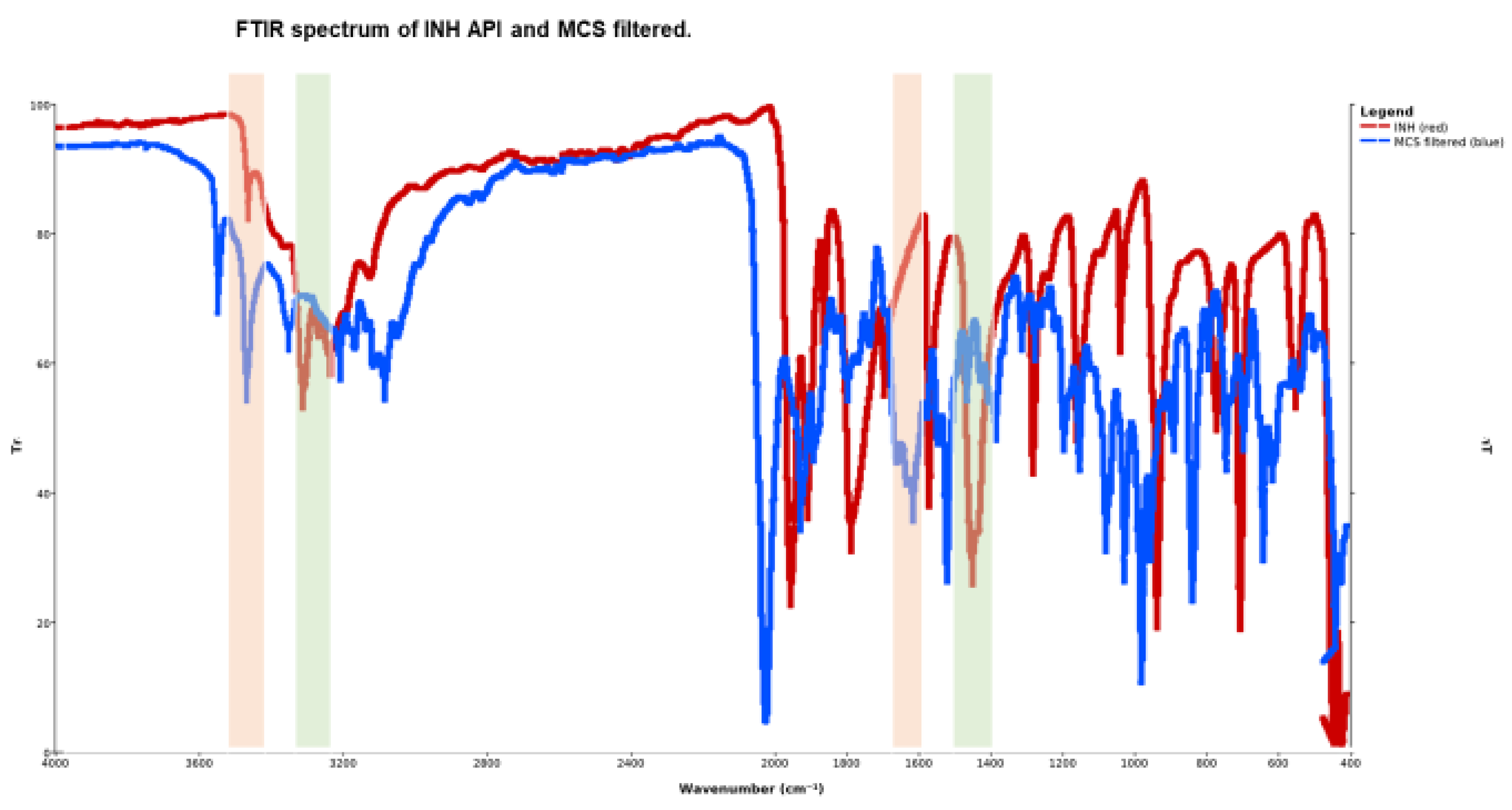

3.3. FTIR Spectroscopy and Molecular Interaction

The FTIR signature of INH API showed aryl C–H (3105–3009 cm⁻¹) and C=O (~1663 cm⁻¹) peaks, and a dominant pyridine-band at 1553 cm⁻¹. In MCM and MCS filtered samples, the NH stretching region (3300–3400 cm⁻¹) intensified and shifted; the pyridine band moved to ~1559 cm⁻¹ with reduced intensity. These changes can be rationalised by hydrogen-bond reorientation, altered donor–acceptor geometry, and the ingress of co-drug moieties into the INH hydrogen-bond network.

Figure 4.

FTIR characteristic frequency bands of INH API and MCS filtered.

Figure 4.

FTIR characteristic frequency bands of INH API and MCS filtered.

Table 2.

FTIR characteristic frequency bands of the INH API, INH-branded tablet ground and MCS filtered.

Table 2.

FTIR characteristic frequency bands of the INH API, INH-branded tablet ground and MCS filtered.

| Compound |

Experimental frequency

(cm-1)

|

Standard frequency

(cm-1)

|

Functional groups |

| INH API |

3303.60

3105.34

1662.77

1602.82 |

3400-3300

3100-3000

1640-1690

1400-1600 |

N-H stretch, primary aliphatic amine

C-H stretch in aromatic portion

Carbonyl stretch, strong

C=C stretching, strong alkene |

| INH-branded tablet grounded |

3412.38

3154.54

2972.10

1700

1644.37 |

3400-3300

2850-3000

2500-3000

1670-1820

1648-1638 |

N-H stretch, primary aliphatic amine

C-H strong aromatic

Aldehyde stretches

Carbonyl stretch, strong

C=C stretching |

| MCS filtered |

3108.30

1665.08

1602.83 |

3100-3000

1685-1666

1620-1610 |

C-H stretching

C=O stretching, strong

C=C stretch, strong |

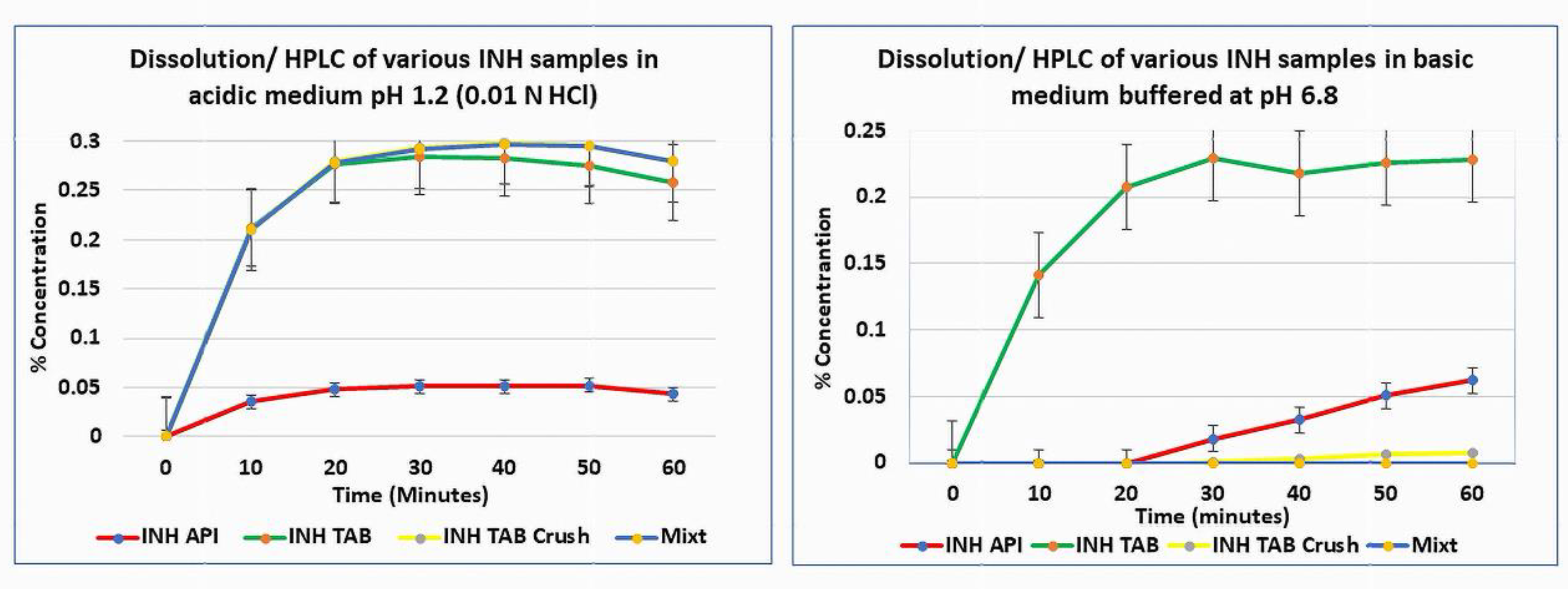

3.4. Dissolution / HPLC

At pH 1.2 (0.01 N HCl), INH API and tablets dissolved as expected. However, in the multi-drug suspension (MCS), visible residue persisted, and INH was below quantification by HPLC in both acidic and neutral media. The inability to quantify INH despite dissolution conditions suggests formation of undissociable supramolecular assemblies – ‘insoluble’ hydrogen-bonded complexes or drug–excipient/co-drug adducts that fail to release free INH into solution. At pH 6.8, the instability of INH is exacerbated, further reducing the recoverable drug. This behaviour aligns with the supramolecular disruption observed in spectroscopic and thermal analyses. The low recovery is attributed to insoluble supramolecular complex formation and/or matrix entrapment.

Profiles did not reach a plateau, and extension beyond 60 min was not performed, as oxidative degradation would confound interpretation. Furthermore, the HPLC assay confirmed selectivity for INH at 238 nm and linearity (r² = 0.9997). LOD 0.0015 mg mL⁻¹ and LOQ 0.005 mg mL⁻¹ were established. No interfering peaks were observed, verifying method specificity

Figure 5.

Dissolution profiles of INH API, INH-branded tablet, INH-branded crushed tablet, and mixture at pH 1.2 and pH 6.8.

Figure 5.

Dissolution profiles of INH API, INH-branded tablet, INH-branded crushed tablet, and mixture at pH 1.2 and pH 6.8.

4. Discussion

4.1. Supramolecular Disruption Drives Instability

The combined thermal, spectroscopic, and dissolution data converge to suggest that supramolecular disruption is a central mechanism of INH instability in manipulated formulations. Mechanical grinding fractures the hydrogen-bond and π–π stacking network, converting regions of the lattice into defects or amorphous domains. The introduction of water and co-drug molecules enables competitive hydrogen bonding, where INH molecules form new bonds with surrounding compounds, thereby further undermining their original lattice cohesion. The observed spectral shifts in OH/NH and pyridine bands, and the suppression of thermal transitions, support this interpretation.

This destabilisation rationalises why INH in multi-drug suspension becomes non-quantifiable in dissolution/HPLC: INH molecules are locked into insoluble complexes or cross-linked networks, resistant to solvation. In effect, the drug loses its molecular mobility and cannot desorb into solution.

These observations substantiate supramolecular disruption as a correlative, rather than in-situ, phenomenon and align with the known polymorphic nature of INH, where stress-induced conversion between crystalline forms can overlap with molecular-level reorganisation.

Thermal behaviour mirrored the spectroscopic changes: samples exhibiting the largest OH/NH band broadening also displayed the lowest onset of melting, consistent with weakened intermolecular cohesion. Such changes arise from mechanical stress and drug–excipient interactions that destabilise the hydrogen-bond network, producing metastable or amorphous states.

When co-suspended with companion drugs, additional competitive hydrogen bonds form, leading to a heterogeneous matrix in which INH molecules are partially immobilised or complexed, reducing effective dissolution and assayable content.

The dissolution profiles provide a practical manifestation of these molecular events. While intact tablets and API met the pharmacopeial specification (≥ 80 % release within 45 min), both the ground and co-suspended mixtures showed markedly slower and incomplete release. The slight upward trajectory of the tablet curves near 60 min represents the normal asymptotic approach to equilibrium under sink conditions rather than incomplete disintegration. Testing was purposefully limited to 60 min to conform with the USP immediate-release specification and to avoid artefacts from post-release oxidative degradation, which becomes significant beyond that window. This timeframe captures the clinically relevant dissolution phase of immediate-release dosage forms; extending beyond it would introduce chemical noise without mechanistic benefit.

Although the INH tablet is classified as immediate-release, conversion into an aqueous “immediate-release suspension” fundamentally changes the physicochemical context. In the compressed solid, the crystalline lattice and low molecular mobility protect the hydrazide moiety from hydrolysis and oxidation. Once dispersed in water and mixed with other drugs or excipients, however, INH encounters a highly dynamic hydrogen-bonding environment that promotes supramolecular reorganisation, polymorphic disturbance, and accelerated degradation. Hence, reformulating an immediate-release tablet into a liquid form demands rational vehicle design rather than mechanical dispersion.

Buffer capacity, antioxidant inclusion, redox control, and excipient compatibility must all be engineered to ensure that rapid dissolution does not compromise chemical integrity. The present findings underscore that pharmacotechnical equivalence between solid and liquid immediate-release systems cannot be assumed, particularly for chemically labile APIs such as INH, where observed dissolution may reflect degradation kinetics rather than true release behaviour.

Although the FDA product label reports safe drug–drug interactions between INH and most agents studied, the current investigation focuses exclusively on pre-administration physicochemical instability under bedside conditions, not systemic pharmacology or toxicity.

Figure 5 schematically summarises the proposed supramolecular pathway, where (a) a stable crystalline lattice sustained by hydrogen bonds and π–π stacking, (b) partial amorphisation after grinding, and (c) formation of new intermolecular hydrogen bonds with co-suspended excipients or drugs, resulting in amorphous or insoluble complexes and diminished dissolution.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram summarising the proposed supramolecular pathways for.(a) a stable crystalline lattice sustained by hydrogen bonds and π–π stacking; (b) partial amorphisation after grinding; and (c) formation of new intermolecular hydrogen bonds with co-suspended excipients or drugs, resulting in amorphous or insoluble complexes and diminished dissolution.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram summarising the proposed supramolecular pathways for.(a) a stable crystalline lattice sustained by hydrogen bonds and π–π stacking; (b) partial amorphisation after grinding; and (c) formation of new intermolecular hydrogen bonds with co-suspended excipients or drugs, resulting in amorphous or insoluble complexes and diminished dissolution.

4.2. Relation to Drug–Excipient Interaction Literature

Our observations echo broader findings in drug-excipient compatibility research: excipient interactions can perturb crystallinity, catalyse degradation, or retard dissolution via microenvironmental effects [

6]. In solid dosage design, supramolecular insights have driven the innovation of stabilising excipient systems (e.g. tailored polymer–drug hydrogen-bond interplay) that preserve molecular order [

8]. The field of supramolecular drug delivery likewise emphasises that dynamic hydrogen-bond networks and host–guest interactions underpin stability and release behaviours [

7].

INH-specific work also underscores the sensitivity of its structural environment. For example, cocrystal engineering and ionic liquid strategies for INH aim to stabilise hydrogen-bonding motifs and resist degradation [

9], while studies on accelerated stability of INH polymorphs emphasise how external micro-environment changes (humidity, molecular perturbation) trigger transitions [

10].

4.3. Practical Implications for Paediatric Formulation

These insights have immediate formulation implications: paediatric products must be engineered to preserve molecular order and avoid undesirable intermolecular interactions. Strategies may include:

Minimising aqueous residence time (e.g., rapid dispersion, immediate dosing).

Designing excipients that preferentially support INH’s native hydrogen-bond network, not compete with it.

Avoiding co-suspension of chemically interacting TB drugs, or spatially segregating them.

Exploring stabilising co-crystals, host–guest inclusion structures, or ionic liquid systems for INH that resist supramolecular collapse.

Extemporaneous INH suspensions prepared at the bedside can be chemically unstable and content-variable, making the delivered dose unpredictable in practice [

11]. Such instability plausibly yields poorly soluble/undissociable species that fail standard dissolution—clinically mimicking “INH resistance” rather than revealing true microbial non-susceptibility [

11]. By triangulating thermal, spectroscopic, and dissolution data, this study operationalises that risk and defines formulation-control levers to prevent misclassification and exposure failure in children [

11].

Critically, the supramolecular framework helps explain variabilities in dosing performance and underscores the risk of ad hoc manipulation in paediatric TB regimens.

4.4. Clinical/Pharmaceutical Significance

Dissolution provides the in vitro proxy for oral bioavailability. The multi-drug suspension prepared by crushing and co-mixing (MCS) failed to release measurable INH within 60 min and did not meet pharmacopoeial performance expectations for INH, whereas intact tablets/API performed substantially better. These findings are concordant with FTIR/Raman (perturbed NH/OH and pyridine bands) and thermal data (earlier mass loss, altered endotherms), supporting pre-administration degradation and drug–excipient/co-drug interactions. Clinically, low plasma INH observed in children given crushed multi-drug slurries may reflect formulation failure, not microbial resistance—risking misclassification as “INH resistance.” Practical implications include: avoiding co-ground multi-drug slurries; administering drugs separately where crushing is unavoidable; minimising hold times and using acidic vehicles when appropriate; and prioritising child-appropriate, dispersible formulations. Dissolution therefore operationalises the mechanistic data and differentiates true resistance from formulation failure.

4.5. Clinical Evidence Supporting the Mechanism

Several clinical datasets are consistent with our bench results. In children treated for tuberculosis, subtherapeutic INH exposures have been repeatedly documented [

2]. In a predominantly HIV-infected adult cohort, INH pharmacokinetics were linked to treatment outcomes, highlighting the clinical importance of adequate exposure [

3]. Programmatic paediatric experience with high-dose INH shows feasibility and potential benefit, but also notes lower observed INH concentrations when drugs are crushed and co-mixed, consistent with our finding that the multi-drug suspension (MCS) releases little measurable INH [

12,

13]. Contemporary guidance recognises circumstances where higher INH doses may be warranted [

14,

15,

16], implicitly acknowledging exposure challenges [

4,

5].

Taken together, these clinical data reinforce our central message: low measured INH levels in patients given crushed multi-drug mixtures may reflect formulation failure rather than microbial resistance. This interpretation aligns with our spectroscopy, thermal analysis, and dissolution results showing pre-administration degradation and impaired release. Clinically, this argues for: (i) avoiding co-ground multi-drug slurries; (ii) administering crushed drugs separately (minimal lag time before dosing); (iii) using acidic vehicles when appropriate; and (iv) prioritising child-appropriate dispersible or liquid formulations to ensure reliable exposure.

5. Conclusions

Crushing and co-suspending INH with companion TB drugs significantly disrupts its supramolecular architecture, triggering lower thermal stability, spectral perturbations, and loss of quantifiable dissolution recovery. These findings connect molecular-level interaction phenomena with clinically relevant drug instability and support urgent development of paediatric formulations designed for molecular integrity and compatibility.

Integrating spectroscopy, thermal analysis, and dissolution, this study shows that poor INH exposure from crushed multi-drug preparations arises from preparation-induced instability and impaired release. These results caution against routine slurry preparation and support the use of child-friendly formulations and acid-stable handling. Most importantly, they differentiate true resistance from formulation failure.

Real-world clinical observations of low INH exposure and variable outcomes with crushed regimens [

2,

3,

12] are mechanistically explained by our data showing structural perturbation and poor dissolution of INH after co-mixing. These results provide a practical framework for differentiating true resistance from formulation failure, supporting immediate adjustments in paediatric dosing practices and formulation choice [

4,

5].

Key Contribution

Supramolecular disruption underlies INH degradation when crushed and co-suspended.

Hydrogen-bond reorganisation is reflected in spectroscopic shifts and masked thermal transitions.

The formation of insoluble supramolecular complexes explains undetectable INH despite dissolution protocols.

Supports the design of paediatric dosage forms that maintain molecular stability and avoid multi-drug co-suspension.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, H.S.; Methodology, H.S.; Investigation, Z.I., C.A., A.-B.D., K.I., N.M., R.S.; Formal analysis, H.S.; Writing—original draft, H.S.; Writing—review & editing, A.J.G.P., J.W., M.A.; Supervision, H.S., M.A.; Funding acquisition, H.S., M.A.

Funding

Supported by the South African Medical Research Council (Self-Initiated Research Grant). The FLAIR Fellowship from the Royal Society & African Academy of Sciences funded the procurement of the Anton Paar Cora 5700 Raman spectrometer.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Further data available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the final-year BPharm students from the University of the Western Cape, School of Pharmacy—Zakiyya Ismail, Carla Arendse, Abu-Bakr Dalvey, Karen Iswalal, Nazeem Mohamed, and Rory Snyders—for their invaluable contributions to sample preparation, experimental setup, instrument operation, and data collation. We also thank the Desmond Tutu TB Centre, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Stellenbosch University, for resource sharing, access to facilities and collegial collaboration throughout this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Haywood, A.; Mangan, M.; Grant, G.; Glass, B. Extemporaneous isoniazid mixture: stability implications. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2005, 35, 181–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chideya, S.; Winston, C.A.; Peloquin, C.A.; Bradford, W.Z.; Hopewell, P.C.; Wells, C.D.; Reingold, A.L.; Kenyon, T.A.; Moeti, T.L.; Tappero, J.W. Isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide pharmacokinetics and treatment outcomes among a predominantly HIV-infected cohort with tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 1685–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomberg, B.; Spinaci, S.; Fourie, B.; Laing, R. The rationale for recommending fixed-dose combination tablets for treatment of tuberculosis. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peloquin, C.A.; Durbin, D.; Childs, J.; Sterling, T.R.; Weiner, M. Stability of antituberculosis drugs mixed in food. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 45, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta-Wright, A.; Tomlinson, G.S.; Rangaka, M.X.; Fletcher, H.A. World TB Day 2018: the challenge of drug-resistant tuberculosis. F1000Research 2018, 7, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, G.F.D.S.; Salgado, H.R.N.; Santos, J.L.D. Isoniazid: a review of characteristics, properties and analytical methods. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2017, 47, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmy, H.E.; Abouelmagd, S.A.; Ibrahim, E.A. New ionic-liquid forms of antituberculosis drug combinations for optimised stability and dissolution. AAPS PharmSciTech 2025, 26, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, C.L.B.; Campelo, T.A.; Frota, C.C.; Ayala, A.P.; Silva, L.M.A.; Rocha, M.V.P.; Santiago-Aguiar, R.S. Crystallisation of isoniazid in choline-based ionic liquids: physicochemical properties and anti-tuberculosis activity. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 394, 124907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatkamp, R.H.; de Souza, A.L.; Corrêa, C.C. Drug–excipient compatibility and its impact on solid-state stability. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 234, 115584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, W.-C.; Chen, Q.; Lin, Z.; Jiang, X.-K.; Wang, R. Supramolecular interactions in drug-delivery assemblies: from molecular recognition to formulation performance. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 4361–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, A.; Vickers, S.; Buckton, G.; Crowley, P.J. Understanding drug–polymer interactions in stabilised amorphous systems. Mol. Pharm. 2022, 19, 1487–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Bottom, R. Thermogravimetric Analysis. In Principles and Applications of Thermal Analysis; Gabbott, P., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 87–118. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, B.; Tanwar, Y.S. Applications of solid dispersions. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2015, 7, 965–978. [Google Scholar]

- Falzon, D.; Schünemann, H.J.; Harausz, E.; González-Angulo, L.; Lienhardt, C.; Jaramillo, E.; Weyer, K. World Health Organization treatment guidelines for drug-resistant tuberculosis, 2016 update. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1602308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Consolidated Guidelines on Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Treatment; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United States Pharmacopeial Convention. Dissolution Methods Database; USP: Rockville, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).