1. Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are functional impairments of the musculoskeletal system that affect muscles, tendons, ligaments or nerves. They are often accompanied by pain or functional limitations and are considered one of the leading causes of work incapacity worldwide [

1,

2,

3]. MSDs are highly prevalent in healthcare professions, particularly in nursing [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Previous review articles have reported prevalence rates in healthcare workers ranging from 57% to 93% annually. The most frequently affected body regions were the lower back (46% - 84%), neck (38% - 71%), shoulders (33% - 74%) and knees (20% - 61%) [

5,

7,

8,

9,

10].

One occupational group in which MSD prevalence has not yet been investigated is perfusion staff. Perfusionists are highly specialized healthcare professionals who operate the heart lung machine (HLM) in the operating room (OR). The HLM is used to supply oxygen and nutrients to organs and tissues during cardiac and vascular surgeries. This machine fully replaces the heart and lung functions of a patient and is to be operated and monitored by perfusionists [

11]. These professionals sit or stand in front of the machine for the entire duration of surgery, which may last several hours per workday. Further their job involves the set-up of single use components and moving the heavy HLM as well as working in forced postures. The long working hours and high workload in the healthcare sector also affect the personnel.

In general, some characteristics of a working environment are known to increase the risk for developing MSDs such as prolonged static positions, standing or sitting for long periods of time, working with a twisted or bent posture, moving heavy equipment and long, fluctuating work schedules [

5,

8,

10,

12,

13,

14]. It is assumed that those risk factors are present in the profession of perfusion.

As of early 2025, approximately 650 perfusionists were practicing in Germany [

15,

16], compared to about 5300 in Europe [

17] and 5000 in the United States [

18]. The already limited workforce, combined with the broader shortage of healthcare professionals, poses a significant risk to the healthcare sector and therefore to the general public. According to Turnage et al. (2017), perfusionists are particularly vulnerable to staffing shortages because replacing such highly specialized professionals is challenging [

19]. Additionally, Lewis et al. (2016) indicate, that 39% of U.S. perfusionists are expected to leave the profession within a decade [

20]. Retaining skilled personnel is therefore crucial.

Given that many established risk factors for MSDs are likely present in the perfusion workplace, the present study aims to investigate the prevalence of MSDs among perfusion staff in Germany and to examine associations with known occupational risk factors.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was composed as a multicenter, cross-sectional, observational analysis of all perfusionists employed in cardiac centers in Germany. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of FH Münster University of Applied Sciences.

All 78 centers listed by the German association of perfusion were invited to participate in the study [

15]. The revised and validated German-language version of the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (FB*MSB) was used [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. The questionnaire records demographic data and the prevalence of MSDs in ten regions of the body. Questionnaires were distributed via the participating cardiac centers and completed individually by the perfusionists. All participants received written information about the study and data protection prior to participation. Written consent was given by all participants included in the study. Completed questionnaires were digitized and analyzed statistically (SPSS version 29.0.1). Continuous variables are shown as mean with 95% confidence interval as well as standard deviation and range. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages. MSD prevalence was calculated for the entire study population and expressed as a percentage of the cohort for each of the ten body regions.

The metric variables of the demographics within the cohort were tested for correlation using the Pearson correlation test. For the analysis, three demographic factors were split into four groups each, based on preceding studies [

12,

14,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Those are age (≤35, 36-45, 46-55, >55 years), BMI (underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese), and years of experience (YoE) as perfusionist (≤5, 6-10, 11-20, >20 YoE).

The occurrence of MSDs among different groups within the cohort was analyzed using the chi squared test. Fisher’s exact test was applied where cell counts were <5. The tests were carried out as paired crosstab tests where one group of interest was tested against the rest of the cohort. This was repeated for all subgroups of a characteristic, so that a total of four tests were performed per characteristic. To account for α-error inflation, p-values were adjusted using Bonferroni Holm correction [

29]. In these tests, the φ-coefficient was calculated to indicate an association between the dichotomous variables. Significance level α < .05 was chosen for all statistical analyses [

30].

3. Results

A total of 45 cardiac centers in Germany participated in the study. From these, 287 questionnaires were included in the analysis, corresponding to a response rate of 58%. According to the German association of perfusion there are currently about 650 active perfusionists in Germany [

15]. Thus, the sample represents 44% of the national perfusion workforce. Of the participants, 25.1% (n = 72) were female and 74.9% (n = 215) were male. The mean age was 42.6 ± 11.9 years with an average professional experience as perfusionist of 13.5 ± 10.9 years. The mean BMI was 26.0 ± 3.7 kg/m2 (

Table 1). With 89.5% (n = 257), the majority of participants reported being right-handed, while 5.6% (n = 16) identified as left-handed and 4.9% (n = 14) as ambidextrous.

A strong positive correlation was observed between age in years and years of professional experience (p < .001; r = .868). Age also presented a weak positive correlation with the BMI (p = .038; r = .123).

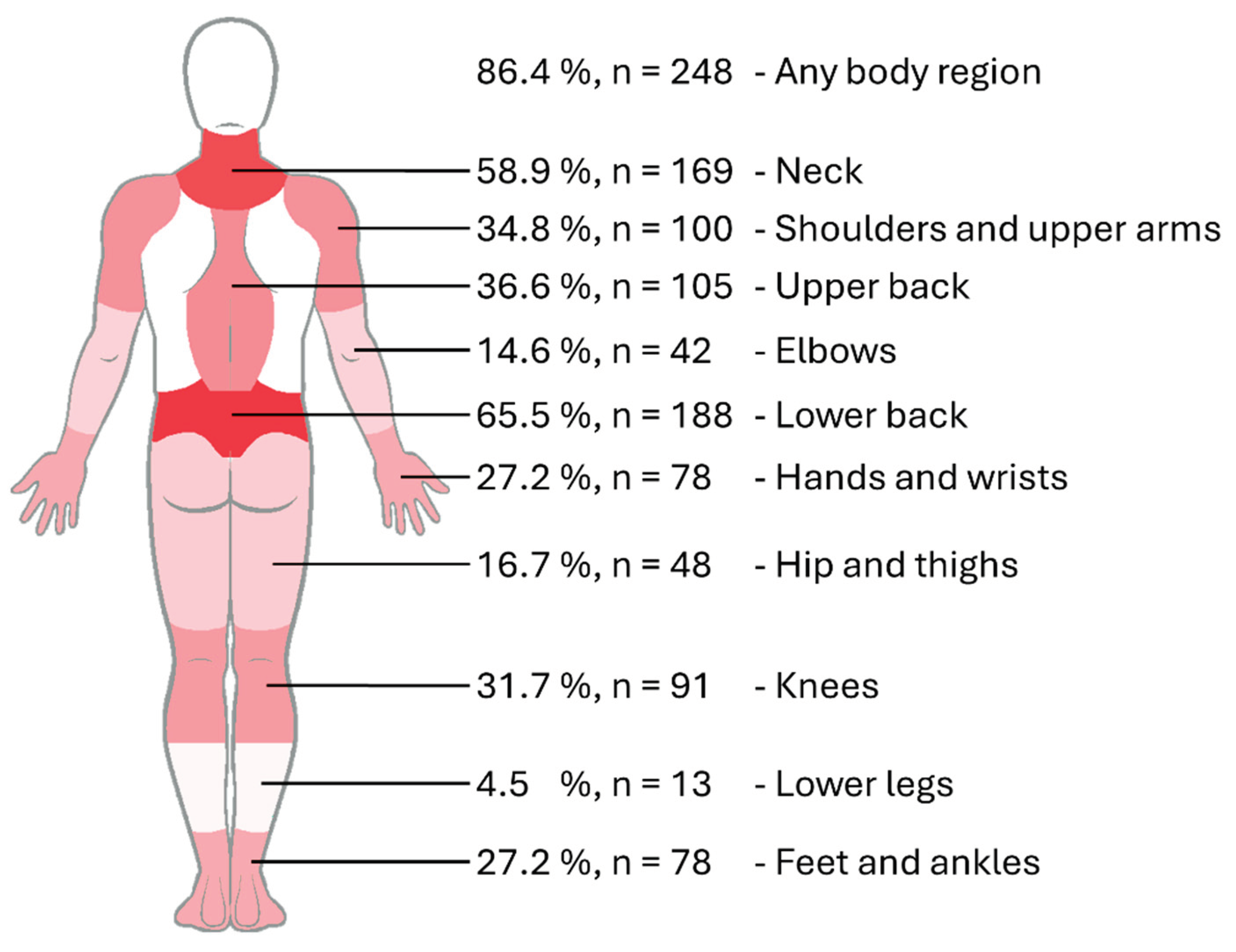

Overall, 86.4% of participants reported experiencing MSDs in at least one body region during the previous 12 months. The most frequently affected body region was the lower back with 65.5%, followed by the neck with 58.9%. More than a third of the respondents reported complaints in the upper back (36.6%), shoulder joints and upper arms (34.8%), and knees (31.7%). In the body regions of the hands and wrists as well as in the feet and ankles, the prevalence was 27.2%. The hip and thighs, elbows and forearms, and lower legs presented annual prevalence rates below 20% (

Figure 1). Participants were categorized by age, BMI, and YoE in perfusion as shown in

Table 2. The Table presents subgroup sizes and their proportions within the overall cohort.

Utilizing the chi-squared test, significant subgroup differences in MSD prevalence were observed in seven of the ten body regions between the age, BMI and YoE groups. The significant results of these tests are displayed in

Table 3. When there were no significant associations (p > .05) the according group is left out.

Regarding BMI, differences were only observed in the feet and ankles, where overweight participants reported a higher prevalence, while normal weight participants reported a lower prevalence. Professional experience of more than 20 YoE was associated with increased MSD prevalence in four body regions. Two of these regions, as well as the lower back revealed significantly fewer MSDs in perfusionists with less professional experience (≤5 YoE). Older perfusionists (>55 years) consistently reported higher rates of MSDs and presented significantly more MSDs in six body regions. Four of these regions also presented significantly lower rates of MSDs in younger participants (≤35 years). No significant associations were found in the body regions of elbows and forearms, upper back and lower legs.

4. Discussion

This nationwide cross-sectional study revealed a high prevalence of MSDs in perfusionists in Germany, with 86% of participants reporting symptoms in a least one body region. This is comparable to prevalence rates in other health professions. Comprehensive review articles on the topic reported rates ranging from 57% to 93% [

5,

8,

9,

10]. It can be assumed that perfusion staff are at a similar risk in developing work-related MSDs.

Age has previously been assessed as a non-modifiable risk factor for developing MSDs [

31]. It can therefore be assumed that the prevalences rates correlate with age, even without occupational overexposure. However, higher age has proven to be a risk factor for developing MSDs in the regions of neck, shoulder, lower back and knees [

9,

10,

27,

32,

33]. In this study, age emerged as the most consistent factor associated with MSDs. Perfusionists at age >55 years showed significantly more MSDs (p < .05) in neck, shoulder, hands and wrists, lower back, hip and thighs as well as knees. In those body regions the age group reported about 20% more MSDs than the rest of the cohort. It is consequently believed that age is a present risk factor in perfusion and must be dealt with accordingly. Additionally, YoE and age are highly correlated, making it difficult to distinguish MSD causes. Therefore, contributing risk factors identified in healthcare workers are extrapolated to perfusion staff where applicable, with age considered as an independent factor.

The highest MSD prevalence was reported in the

lower back (65.5%). It can plausibly be explained by known risk factors such as prolonged static postures, non-neutral trunk positions, and handling of heavy or specialized equipment [

5,

8,

9,

25,

26,

32,

33,

34,

35]. These exposures are present on a daily basis in perfusion when preparing and operating the HLM and could lead to MSD symptoms over the course of a career. Complaints were significantly less common among participants with ≤5 YoE, suggesting that lower back MSDs develop after the first years in perfusion when exposed to risk factors for some time. A connection between professional experience and MSDs has previously been proven, especially with a sharp increase within the first years of employment [

10,

12,

34,

36].

The

neck presented a high prevalence rate (58.9%). This could be attributed to proven risk factors like frequent neck twisting, repetitive movements and static positions [

5,

8,

9,

10]. Although prevalence was highest among older participants, the considerable prevalence observed in younger perfusionists suggests systematic occupational hazards. Those could include monitoring screens in unfavorable OR-layouts and adjusting equipment.

Shoulders and upper arms MSDs (34.8%) were significantly associated with increasing age and YoE. The highest subgroup prevalence rate was observed in participants with >20 YoE (53%). Commonly described risk factors for shoulder discomfort are repetitive use of the upper extremities, working with raised arms, and handling tools [

5,

8,

9,

25,

32]. Since these characteristics are present in perfusion, cumulative exposure is a plausible explanation.

Complaints in the

knees (31.7%) were significantly associated with higher age and increased YoE. Identified risk factors for knee pain were standing for long periods of time, retention of static positions, increasing YoE and age [

8,

9,

27,

32]. Since the perfusion occupation can require long times of standing in the OR, a systematic endangerment could be a strong possibility.

Hand and wrist complaints (27.2%) showed a significant connection to higher age. Although our study did not identify other risk factors, preceding studies on haemodialysis nurses proved a higher risk when assembling and dismantling single-use components on a daily basis [

37,

38]. Since the setup and clearing of the HLM is a key element of the daily tasks of perfusionists, systematic endangerment cannot be ruled out.

In the region of

feet and ankle (27.2%) overweight participants presented a significantly higher prevalence, indicating weight bearing stress as the main contributor [

9]. Also associated was higher professional experience, pointing towards prolonged standing over the course of a career as possible risk factor [

8,

9].

Hip and thigh (16.7%) discomfort was associated with increasing age and higher YoE. Prolonged standing is linked to MSDs [

5,

25], however age correlates with reduced flexibility and MSDs [

10,

25,

27]. The low prevalence among younger participants suggests that risk factors are more age-related than occupation-specific, rendering targeted interventions a low priority.

The upper back (36.6%) prevalence was higher than most of the body regions but lacks statistical significance and is not well reported in the literature. Prevalence in the elbows (14.6%) and lower legs (4.5%) was comparatively low and showed no significant subgroup associations. While these regions may be less systematically affected, they warrant continued observation in future research.

Limitations

The use of a self-administered questionnaire may have introduced recall bias, as participants reported MSDs over the past 12 months. Self-assessment could also lead to over- or underestimation of prevalence. These limitations were accepted to utilize the validated and widely used NMQ questionnaire. Additionally, the study design did not link participants to specific cardiac centers or collect data on workplace conditions, such as tasks, equipment, or schedules. MSD intensity and duration were also not recorded, limiting severity assessment. As the first nationwide survey on MSD prevalence among perfusionists, comparisons with prior research were difficult. Future studies should therefore incorporate ergonomic workplace assessments, direct observations, and movement analyses to identify causal risk factors and guide the development of targeted interventions.

5. Conclusions

This nationwide study revealed a high prevalence of MSDs among perfusionists in Germany, with 86% reporting symptoms in at least one body region within the last 12 months. Age and years of professional experience were identified as risk factors. Occupational risk factors previously described in other healthcare professions, such as prolonged static postures, non-neutral working positions and equipment handling are also likely relevant in developing MSDs in perfusionists. The lower back and neck affected more than half of the participants and were associated with the aforementioned risks, underscoring the need for preventive measures, ergonomic interventions and task-specific assessments. Body regions with moderate and low prevalence rates (shoulders, upper back, hands, knees, hips, and ankles) warrant further investigation, as occupational overexposure cannot be ruled out. In times of workforce shortages in healthcare, maintaining the health of perfusionists is essential to retain experienced staff and ensure long-term sustainability of this highly specialized profession.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.G., N.H. and C.B.; methodology, A.R.G., M.K. and N.H.; formal analysis, A.R.G., C.B. and N.H.; investigation, A.R.G., M.K.; resources, C.B. and N.H.; data curation, A.R.G., M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.G.; writing—review and editing, C.B. and N.H.; visualization, A.R.G., M.K.; supervision, C.B. and N.H.; project administration, C.B. and N.H.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of FH Münster University of Applied Sciences (protocol code 2024-109 on January 17, 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank all cardiac centers and perfusionists therein who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MSD |

Musculoskeletal disorder |

| NMQ |

Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire |

| HLM |

Heart-lung machine |

| OR |

Operating room |

| FB*MSB |

Fragebogen zu Muskel-Skelett-Beschwerden |

| YoE |

Years of experience |

| BMI |

Body-mass-index |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

References

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Selected health conditions and likelihood of improvement with treatment. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jan de Kok, Paul Vroonhof, Jacqueline Snijders, Georgios Roullis, Martin Clarke. Work-related MSDs prevalence costs and demographics in the EU report: This report was commissioned by the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). 2019. [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, B.R.; Vieira, E.R. Risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review of recent longitudinal studies. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 285–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauber, T.; Isusi, I. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders: prevalence, costs and demographics in the EU: National report: Germany. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/sites/default/files/work_related_MSDs_Germany.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Jacquier-Bret, J.; Gorce, P. Prevalence of Body Area Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skela-Savič, B.; Pesjak, K.; Hvalič-Touzery, S. Low back pain among nurses in Slovenian hospitals: cross-sectional study. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2017, 64, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, K.G.; Kotowski, S.E. Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Disorders for Nurses in Hospitals, Long-Term Care Facilities, and Home Health Care: A Comprehensive Review. Hum. Factors 2015, 57, 754–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suganthirababu, P.; Parveen, A.; Mohan Krishna, P.; Sivaram, B.; Kumaresan, A.; Srinivasan, V.; Vishnuram, S.; Alagesan, J.; Prathap, L. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among health care professionals: A systematic review. Work 2023, 74, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Yin, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Cai, W. Prevalence of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among Nurses: A Meta-Analysis. Iran. J. Public Health 2023, 52, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakkol, R.; Karimi, A.; Hassanipour, S.; Gharahzadeh, A.; Fayzi, R. A Multidisciplinary Focus Review of Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Operating Room Personnel. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, J.; Melzer, S. Berufsbild. Available online: https://perfusiologie.de/ueber-uns/berufsbild/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Alwabli, Y.; Almatroudi, M.A.; Alharbi, M.A.; Alharbi, M.Y.; Alreshood, S.; Althwiny, F.A. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Medical Practitioners in the Hospitals of Al'Qassim Region, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2020, 12, e8382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, D.; Campos-Serna, J.; Tobias, A.; Vargas-Prada, S.; Benavides, F.G.; Serra, C. Work-related psychosocial risk factors and musculoskeletal disorders in hospital nurses and nursing aides: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacker, H.; Yasobant, S.; Viramgami, A.; Saha, S. Prevalence and determinants of (work-related) musculoskeletal disorders among dentists - A cross sectional evaluative study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2023, 34, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, J.; Melzer, S. Herzzentren. Available online: https://perfusiologie.de/karriere/herzzentren/ (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- DIE WELT. Kardiotechniker: Die verkannten Lebensretter im OP - WELT. Available online: https://www.welt.de/gesundheit/article168921312/Diese-Maenner-sind-die-verkannten-Lebensretter-im-OP.html (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Debeuckelaere, G.; Klüß, C.; Ruck, K.; Nagaraj, N.G.; Brajlović, E.; Kjellberg, G.; Talmaciu, C.; Lenart, Z.; Muraskauskaite, M.; Ristić, N.; et al. Perfusion education and training in Europe anno 2023. Perfusion 2025, 40, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, W. 2024 Annual Report, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2025. Available online: https://www.abcp.org/UserFiles/2024AnnualReport.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Turnage, C.; DeLaney, E.; Kulat, B.; Guercio, A.; Palmer, D.; Ann Rosenberg, C.; Spear, K.; Boyne, D.; Johnson, C.; Riley, W. A 2015–2016 Survey of American Board of Cardiovascular Perfusion Certified Clinical Perfusionists: Perfusion Profile and Clinical Trends. J Extra Corpor Technol 2017, 49, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, D.M.; Dove, S.; Jordan, R.E. Results of the 2015 Perfusionist Salary Study. J Extra Corpor Technol 2016, 48, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuorinka, I.; Jonsson, B.; Kilbom, A.; Vinterberg, H.; Biering-Sørensen, F.; Andersson, G.; Jørgensen, K. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl. Ergon. 1987, 18, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebers, F.; Freyer, M.; Freitag, S.; Dulon, M.; Hegewald, J.; Latza, U. Fragebogen zu Muskel-Skelett-Beschwerden (FB*MSB), 2022.

- Kreis, L.; Liebers, F.; Dulon, M.; Freitag, S.; Latza, U. Verwendung des Nordischen Fragebogens zu Muskel-Skelett-Beschwerden. Zbl Arbeitsmed 2021, 71, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebers, F.; Freyer, M.; Dulon, M.; Freitag, S.; Michaelis, M.; Latza, U.; Hegewald, J. Neuer deutschsprachiger Fragebogen zur standardisierten Erfassung von Muskel-Skelett-Beschwerden im Betrieb. Zbl Arbeitsmed 2024, 74, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passali, C.; Maniopoulou, D.; Apostolakis, I.; Varlamis, I. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among Greek hospital nursing professionals: A cross-sectional observational study. Work 2018, 61, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Homaid, M.; Abdelmoety, D.; Alshareef, W.; Alghamdi, A.; Alhozali, F.; Alfahmi, N.; Hafiz, W.; Alzahrani, A.; Elmorsy, S. Prevalence and risk factors of low back pain among operation room staff at a Tertiary Care Center, Makkah, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, M.; Borujeni, M.G.; Rezaei, P.; Kabirian Abyaneh, S. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders and Their Associated Factors in Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study in Iran. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 26, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T.; Serranheira, F.; Loureiro, H. Work related musculoskeletal disorders in primary health care nurses. Applied nursing research: ANR 2017, 33, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmerich, W.A. StatistikGuru: Rechner zur Adjustierung des α-Niveaus. Available online: https://statistikguru.de/rechner/adjustierung-des-alphaniveaus.html (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Döring, N. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften, 6., vollständig überarbeitete, aktualisierte und erweiterte Auflage; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2023; ISBN 978-3-662-64762-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mody, G.M.; Brooks, P.M. Improving musculoskeletal health: global issues. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2012, 26, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, G.; Shao, T.; Xu, Y. Prevalence and associated factors of musculoskeletal disorders among Chinese healthcare professionals working in tertiary hospitals: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, A.; Kav, S.; Abbasoglu, A.; Dogan, N. Low back pain: prevalence and associated risk factors among hospital staff. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videman, T.; Ojajärvi, A.; Riihimäki, H.; Troup, J.D.G. Low back pain among nurses: a follow-up beginning at entry to the nursing school. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976) 2005, 30, 2334–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourollahi, M.; Afshari, D.; Dianat, I. Awkward trunk postures and their relationship with low back pain in hospital nurses. Work 2018, 59, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni-Bandpei, M.A.; Ahmad-Shirvani, M.; Golbabaei, N.; Behtash, H.; Shahinfar, Z.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C. Prevalence and risk factors associated with low back pain in Iranian surgeons. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 2011, 34, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibenthal, E.; Hinricher, N.; Nienhaus, A.; Backhaus, C. Hand and wrist complaints in dialysis nurses in Germany: a survey of prevalence, severity, and occupational associations. Ann. Work Expo. Health 2024, 68, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westergren, E.; Lindberg, M. Work-related musculoskeletal complaints among haemodialysis nurses: An exploratory study of the work situation from an ergonomic perspective. Work 2022, 72, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).