1. Introduction

The global burden of work-related musculoskeletal disorders WRMSDs remain the leading cause of lost work-days and disability worldwide, with substantial health and economic costs for workers and theirs employers [

1]. In the health sector significant challenges impose both physical and emotional strains on workers [

2] and nurses, due to the inherent demands of their profession, are particularly susceptible to various health risks, including musculoskeletal disorders WRMSDs [

3]. The specific nature of nursing duties, combined with organizational culture and environmental factors within healthcare environments, exacerbates their vulnerability to physical and psychological ailments, which in turn have a strong influence on the tasks they perform with a high impact on the quality of care provided. and patient safety [

4,

5,

6].

Psychosocial risks in the healthcare environment stem from increased workloads, time pressure, emotional demands, and insufficient support from management and colleagues. These factors create a stressful work atmosphere that negatively impacts nurses' physical and mental health, contributing to a higher incidence of WRMSDs [

1].

Previous studies have established a strong link between the intense pace of work, exposure to suffering and death, emotional overload, and the development of musculoskeletal disorders among nursing professionals [

7,

8,

9]. In addition to psychosocial risks, violence in the workplace is another critical issue that healthcare workers frequently encounter [

10]. Concurrently, workplace violence has escalated post-pandemic; psychological and vicarious aggression not only elevate anxiety and stress but are also associated with greater musculoskeletal pain [

11]. Forms of violence range from verbal abuse and threats to physical assaults, typically from patients or their relatives, but also from colleagues. The repercussions of such violent experiences are severe, affecting both the physical and mental well-being of healthcare workers, reducing job satisfaction, and impairing overall work performance [

12,

13]. Understanding the factors associated with workplace violence and its prevention is essential to mitigating its impact on healthcare workers [

14,

15,

16]. Moreover, mental health concerns, including depression, anxiety, and stress, are prevalent among nurses and significantly affect their susceptibility to WRMSDs [

17]. High job demands, emotional labor, and the burden of caregiving contribute to psychological distress, which in turn exacerbates physical health problems [

18,

19]. This research used three distinct questionnaires to evaluate factors related to psychosocial risks at work, violence dimensions and mental health that could be responsible for the occurrence or aggravation of WRMSDs: the INSAT for psychosocial risk factors related to work, the Aggression and Violence at Work Scale [

20] for dimensions of workplace violence, and the DASS-21 [

21] for mental health dimensions. By comprehensively examining these variables, this study seeks to elucidate the multifaceted influences on the occurrence of WRMSDs in nurses, providing a foundation for targeted interventions and preventive measures to improve the health and well-being of healthcare workers.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Portuguese nurses from public and private hospitals, between June 2024 and November 2024 (this study is part of a larger study applied to professionals working in various activity sectors). All participants provided informed consent to participate in this study, and issues associated with confidentiality and anonymity were ensured, keeping in mind the Data Protection Law Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (General Data Protection Regulation). The Ethics Committee of Fernando Pessoa University approved the study, with the reference FCHS/PI 219/21-2. The study promotion and recruitment were done by social platforms (e.g. Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp), and data collection was conducted online using the Google Forms platform.

The sample consisted of 266 nurses working in hospitals and primary healthcare centers in Portugal, both public (53.4%) and private (46.6%). It was composed of 83.3% females and 16.7% males, aged between 20 and 67 years (M = 36.67; SD = 10.992). Most nurses (61.7%) have been working for less than 16 years. Most of the participants (79.3%) work under permanent contracts.

In this study, three different scales were used: i) INSAT - Health and Work Survey, a self-reported questionnaire that measures working conditions, risk factors, and health problems. Concerning the main goal of the present study, only the psychosocial risk factors and musculoskeletal disorders items were used. The psychosocial risk factors were grouped in categories: work intensity (10 items, α = .918); lack of autonomy (4 items, α = .857); work relations with coworkers and managers (8 items, α = .908); employment relations with the organization (13 items, α = .929); working times (8 items, α = .848); emotional demands (8 items, α = .939) and ethical and value conflicts (4 items, α = .911). Psychosocial-risk items originally measured on a 6-point Likert scale (0 = “not exposed”; 1–5 = “exposed” with increasing discomfort) were dichotomized for analysis: 0 = no exposure and 1 = yes (combining responses 1 through 5). In terms of psychometric properties, the INSAT has good internal consistency obtained by the Rasch Partial Credit Model analysis, with Person Separation Reliability coefficient of 0.8761, and has been used in several health-related studies before [

4,

7,

22]. To measure WRMSDs a four ordered categories item from INSAT was used (0 = no disorder; 1 = disorder not work-related; 2 = disorder present and work aggravates it; 3 = disorder present and work is the primary cause). For this study’s purposes, this variable was transformed into a dichotomous outcome: 0 = no work-related disorder (levels 0 and 1) and 1 = work-related disorder (levels 2 and 3). This collapses non-occupational conditions into the reference category and isolates cases in which work exposure either precipitates or exacerbates the disorder, thereby aligning the dependent variable with the study’s focus on work-related risk; ii) The Violence at Workplace was assessed through Aggression and Violence at Work Scale [

20] that evaluates three dimensions of violence: physical violence (8 items, α = .833), psychological violence (3 items, α = .812), and vicarious violence at work (5 items, α = .916). The physical violence subscale consists of eight items reflecting a variety of physically violent behaviors and threats (e.g., being hit, kicked, or threatened with a weapon). Psychological violence was measured with a three-item subscale representing exposure to psychological aggression at work stemming from three sources: colleagues, supervisors and members of the public (e.g., being yelled at or sworn at). The vicarious violence subscale, with five items, indicates how often they had witnessed or heard about violent events experienced by co-workers, supervisors, friends, or relatives. All three dimensions of violence are covered by a total of 16 items arranged in an ordinal Likert-type scale with four classes that indicate a frequency (ranging from 0 for “never” to 3 for “four or more times”). The measure has been shown to have acceptable construct validity and reliability for the Portuguese version used in this study (Cronbach’s Alpha > 0.68 for all subscales) [

23]; iii) The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale - 21 Items (DASS-21) [

21] is a set of three self-report scales designed to measure the emotional states of depression (7 items, α = .914), anxiety (9 items, α = .937) and stress (5 items, α = .910). These categories have different items measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not applied to me) to 3 (applied to me most of the time).

A descriptive statistical analysis of all variables assessed was performed. Frequency and percentage analyses were performed on the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. Afterwards, a descriptive analysis of all variables from the three questionnaires was performed using frequency measures, central tendency (mean) and dispersion measures (standard deviation, range, minimum and maximum). Then, a Bivariate analysis was performed using point-biserial correlation to identify the psychosocial risk factors, violence factors and mental health factors that could be related to WRMSDs. Subsequently, a multivariable binary-logistic regression was performed using the ENTER method, entering predictors in three sequential blocks (block 1: psychosocial risk items, block 2: DASS-21 anxiety score, block 3: violence exposure scores) to estimate their adjusted associations with the presence of WRMSDs. The threshold for statistical significance was p < 0.05. The regression equations satisfied all assumptions, and the results of the logistic regression analyses were considered reliable. Data were analyzed with the support of the IBM SPSS statistical program for Windows, version 29.0 (SPSS Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

The study was performed with 266 nurses from public (53.4%) and private (46.6%) sector. Participants’ ages ranged between 20 and 67 years (Mean (M) = 36.67 years; Standard Deviation (SD) = 10.992 years). All the sociodemographic characteristics are presented in

Table 1.

The descriptive analysis of the musculoskeletal work-related disorders (WRMSDs) item from INSAT showed that 86% of the participants suffered from WRMSDs.

Table 2 summarizes the descriptive analysis of the INSAT Psychosocial Risk Factors Scale, reporting the proportion of nurses who answered “yes” to each workplace stressor. To highlight the most prevalent issues affecting practice, only items endorsed by ≥ 20 % of respondents are shown.

Within Work Intensity, over 90% of participants reported an intense work pace, and more than 70% indicated dependencies on colleagues or customer demands, strict standards, and frequent interruptions, indicating sustained operational pressure. Working-hours strain is reinforced by unpredictable schedules (53 %) and permanent availability (63 %). Autonomy is limited for roughly four in ten workers, who lack decision latitude or flexible breaks. In contrast, Work Relations show notably lower exposure levels, with fewer than one-third reporting discomfort related to recognition, fairness, or trust among colleagues, suggesting relatively stable interpersonal dynamics. However, Employment Relations highlight substantial concerns, with around 70% citing stagnant career progression, inadequate salary, and lack of recognition, signaling structural dissatisfaction. The Emotional Demands dimension stands out, with nearly all respondents reporting regular public contact (94%) and handling others' suffering (89.4%), underscoring the emotional burden intrinsic to their roles. Finally, Work Values reflect moderate concern, with around 45% expressing dissonance between their actions and values or professional identity. Collectively, these findings point to high emotional strain in the work environment, with key risk zones in work intensity, emotional exposure, and organizational recognition.

The descriptive analysis for the three dimensions of mental health (DASS-21) and of workplace violence (Aggression and Violence at Work Scale), is presented in

Table 3.

Complementary continuous measures (Table 2) reinforce this picture. Mental-health scores were moderate: stress averaged 0.76 (SD = 0.73), slightly exceeding anxiety and depression (both M = 0.58). Mean exposure to psychological violence was highest (M = 1.06, SD = 0.99 on a 0–3 scale), followed by vicarious (M = 0.78, SD = 0.91) and physical violence (M = 0.38, SD = 0.53); all variables spanned the full 0–3 range, indicating that a subset of workers experienced maximum violence. The co-occurrence of elevated emotional demands, frequent psychological and vicarious violence, and measurable anxiety–stress symptomatology underscores a multifaceted psychosocial burden likely to influence musculoskeletal health outcomes examined in subsequent analyses.

The results of the point-biserial analysis are presented in

Table 3, with the statistically significant correlations observed between psychosocial risk factors, mental health factors, workplace violence factors,, and WRMSDs.

Table 4.

Point-Biserial analysis: correlations between psychosocial risk factors, mental health factors, violence factors, and WRMSDs.

Table 4.

Point-Biserial analysis: correlations between psychosocial risk factors, mental health factors, violence factors, and WRMSDs.

| Category |

Psychosocial risk Factors |

r |

p |

| Working Intensity |

WI2 |

Depending on colleagues to carry out my work |

0.131 |

0.033 |

| WI6 |

Lack of clear guidance on my tasks |

0.218 |

<.001 |

| WI7 |

Have to deal with contradictory instructions |

0.284 |

<.001 |

| WI9 |

Constantly changing roles and tasks depending on the needs of the company/organization |

0.166 |

0.007 |

| WI10 |

Hyper-solicitation |

0.251 |

<.001 |

| Working Hours |

WH3 |

Having to sleep at unusual hours because of work demands |

0.199 |

0.001 |

| WH4 |

Having to skip or shorten a meal or reduce break times due to work demands |

0.141 |

0.022 |

| WH5 |

Not knowing my work schedule in advance |

0.2 |

0.001 |

| WH6 |

Conflict in balancing work and personal life |

0.151 |

0.014 |

| WH8 |

Having to travel frequently for work |

0.132 |

0.032 |

| Lack of Autonomy |

AI1 |

Having to complete the work exactly as defined, with no possibility of making changes |

0.197 |

0.001 |

| AI2 |

Having to respect strictly defined break periods, with no option to adjust them |

0.277 |

<.001 |

| AI3 |

Having to follow a strict work schedule, with no possibility of small adjustments |

0.265 |

<.001 |

| AI4 |

Having no opportunity to participate in decisions about my work |

0.292 |

<.001 |

| Work Relations |

WR1 |

Spending many hours in a workspace where I feel uncomfortable |

0.203 |

0.001 |

| WR2 |

Frequently needing help from colleagues but not getting it |

0.282 |

<.001 |

| WR3 |

It’s rare to exchange experiences with colleagues to improve the work |

0.194 |

0.001 |

| WR4 |

My opinion about the functioning of the department/section is disregarded |

0.262 |

<.001 |

| WR6 |

At work, I am not well recognized by my colleagues |

0.262 |

<.001 |

| WR7 |

I have no one I can trust |

0.222 |

<.001 |

| WR8 |

I am not treated fairly and with respect by management |

0.182 |

0.003 |

| Employment Relations |

ER2 |

Career progression is almost impossible |

0.177 |

0.004 |

| ER3 |

My salary does not allow me to maintain a satisfactory standard of living |

0.27 |

<.001 |

| ER4 |

Lack of resources to carry out my work |

0.236 |

<.001 |

| ER5 |

There are conditions that undermine my dignity |

0.143 |

0.02 |

| ER6 |

Lack of opportunities to develop my professional skills |

0.289 |

<.001 |

| ER7 |

Lack of recognition and/or appreciation |

0.203 |

0.001 |

| ER8 |

Lacks the feeling of "useful contribution to society" |

0.142 |

0.02 |

| ER9 |

At work, I feel exploited most of the time |

0.186 |

0.002 |

| ER10 |

I am afraid of suffering an injury caused by the nature of my job. |

0.365 |

<.001 |

| ER11 |

My company shows no concern for my well-being |

0.23 |

<.001 |

| ER12 |

It will be very difficult for me to do my job when I am 60 years old |

0.236 |

<.001 |

| Emotional Demands |

ED1 |

I have to handle tense situations in relationships with the public |

0.167 |

0.016 |

| ED3 |

Have to deal with direct contact with external public |

0.148 |

0.006 |

| ED4 |

I fear the possibility of verbal aggression from the public |

0.357 |

<.001 |

| ED5 |

I fear the possibility of physical aggression from the public |

0.345 |

<.001 |

| ED6 |

I have to deal with other people’s difficulties and/or suffering |

0.162 |

0.008 |

| ED7 |

I have to simulate good mood and/or empathy |

0.197 |

0.001 |

| ED8 |

I have to hide my emotions at workplace (e.g. fear, frustration, anger, sadness, disappointment) |

0.246 |

<.001 |

| Work Values |

WV1 |

I have to do things that I disapprove of |

0.202 |

0.001 |

| WV2 |

My professional conscience is shaken |

0.143 |

0.02 |

| WV3 |

The things I do are seen as underrated |

0.185 |

0.002 |

| WV4 |

Lack of necessary resources to perform a well-done job |

0.214 |

<.001 |

| Mental Health |

|

Anxiety |

0.336 |

<.001 |

| |

Depression |

0.28 |

<.001 |

| |

Stress |

0.337 |

<.001 |

| Workplace Violence |

|

Physical |

0.232 |

<.001 |

| |

Psychological |

0.213 |

<.001 |

| |

Vicarious |

0.26 |

<.001 |

Point-biserial correlations show a positive and statistically robust link between musculoskeletal disorders and a set of psychosocial stressors. The strongest associations (r ≈ .34 – .37, p < .001) appear for specific employment and emotional-threat items: afraid of suffering an injury (r = .365), and fear of verbal aggression from the public (r = .357). Moderate correlations (r ≈ .25 – .30) cluster around lack of autonomy with “Having no opportunity to participate in decisions” (r = .292), “deal with contradictory instructions”/”hyper-solicitation” (r = .284–.251), and employment relations (e.g., low salary, r = .270). Although somewhat smaller, consistently significant (r ≈ .13 – .22) links emerge for work-intensity factors (e.g., “Depending on colleagues”, “Lack of clear guidance”) and work values (“things I do are seen as underrated” or “professional conscience is shaken”). Collectively, these coefficients—ranging from small to moderate—indicate that musculoskeletal complaints are most closely tied to perceived threat and insecurity at work, but they are also sensitively modulated by autonomy, workload clarity, and overall psychosocial climate.

Focusing specifically on DASS-21 mental-health scores and violence exposure, the point-biserial analysis confirms a psychological pathway to WRMSDs. Anxiety and stress are the mental health dimensions with the highest correlations (respectively, r =.336 and r =.337), while depression (r =.280). All dimensions contribute significantly (all p <.001). The three workplace violence’s dimensions (Vicarious violence; r =.260; physical violence, r =.232; and psychological violence, r =.213) had moderately favorable relationships with WRMSDs, indicating that exposure to violence also plays an important role. These results highlight the need for integrated interventions that address emotional well-being and violence prevention, as they imply that both direct and indirect experiences of workplace aggression—as well as elevated affective distress—are independently and cumulatively related to higher odds of WRMSDs.

After this multivariable binary-logistic regression was performed using the ENTER method only with the items considered statistically significant from the previous analysis (

Table 5). The method option was Enter because a model only with significant predictors was the main objective for this work. Before this, the assumptions to use this statistical tool were verified and validated. Due to de possibility of multicollinearity between all independent variables, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was calculated and all VIF > 10.0 were removed from the model to ensure the reliability of the logistic regression model. [

24].

The multivariable logistic-regression results show that both work-related stressors and emotional burdens independently shape the odds of reporting WRMSDs. The analysis of psychosocial risk factors shows that four items markedly raise risk: “There are conditions that undermine my dignity” (ER5, OR = 2.073), “feel exploited most of the time “ (ER9, OR = 2.068), “Lack of clear guidance” (WI6, OR = 4.808), “no opportunity to participate in decisions “ (AI4, OR = 8.940), “needing help from colleagues..” (WR2, OR = 11.753), and “Lack of opportunities to develop professional skills” (ER6, OR = 33.532). Conversely, several conditions appear protective: “Depending on colleagues” (WI2, OR = 0.228) and “Conflict in balancing work and personal life” (WH6, OR=.109) show ORs significantly below 1, suggesting lower WRMSDs odds when these issues are present. The anxiety dimension from mental health is a dominant predictor: each one-unit increase in anxiety multiplies WRMSDs odds nearly twenty-fold (OR = 19.08). Finally, workplace violence is a risk amplifier: exposure to psychological violence (OR = 4.22) and vicarious violence (OR = 4.02) each quadruples the likelihood of WRMSDs, independent of other factors.

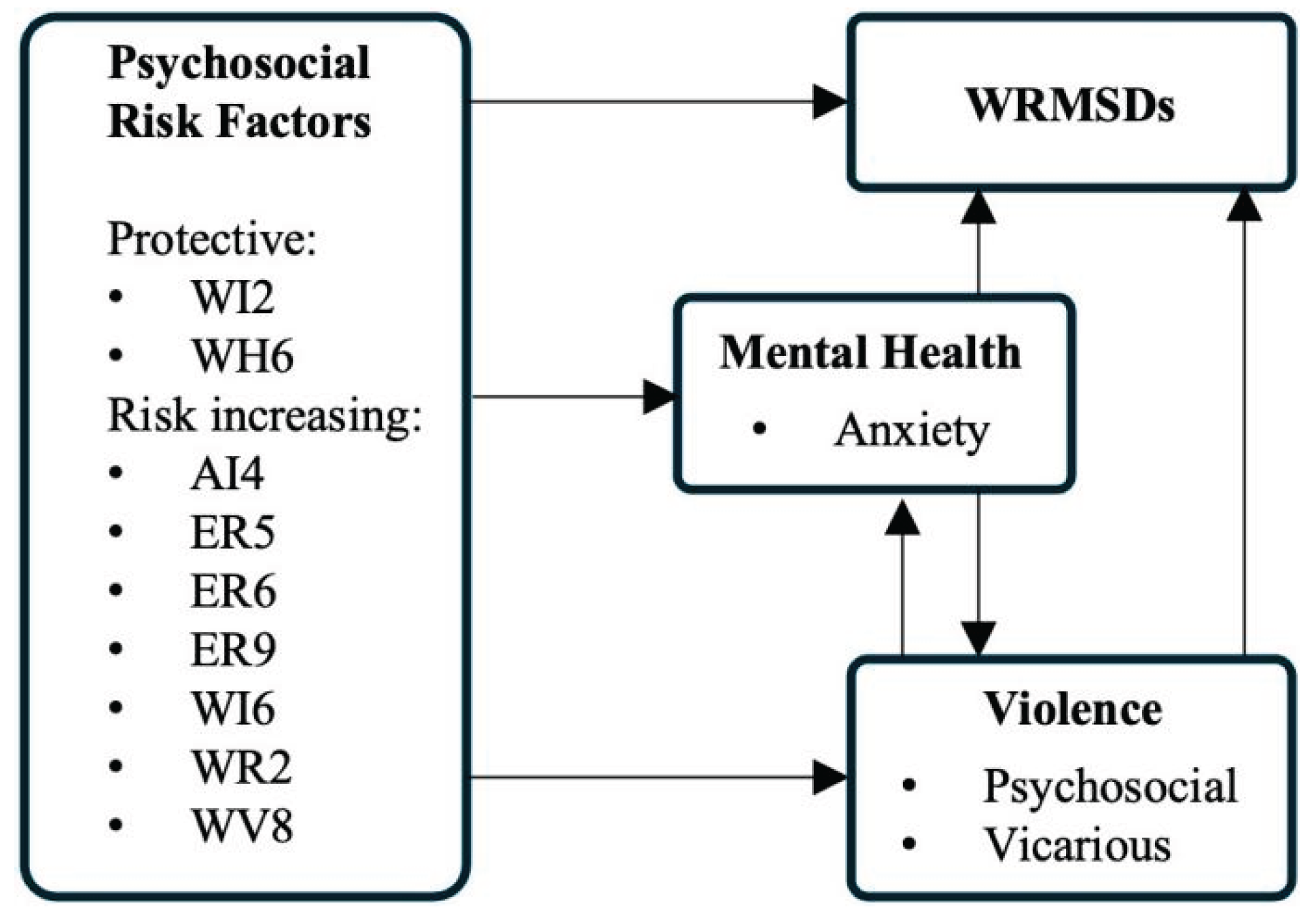

Figure 1 presents an explanatory model structure to visualize the relationship between predictors and WRMSDs.

To resume, inadequate guidance, low decision latitude, skill-development barriers, anxiety, and violence form the principal drivers of WRMSDs in this workforce. In contrast, several seemingly adverse conditions display inverse associations that warrant further qualitative exploration. This model shows that both psychosocial risks, violence at work, and mental health dimensions impact the presence of WRMSDs. The direction and magnitude of these effects provide insights into which factors most strongly influence WRMSDs.

4. Discussion

This study analyzed the complex relationships that exist between psychosocial risk factors, mental health, particularly anxiety, and workplace violence – and WRMSDs in Portuguese nurses. This discussion summarizes the findings in the context of previous research, focusing on three main relationships: 1) between psychosocial risk factors and WRMSDs; 2) between WRMSDs and mental health, especially anxiety; and 3) and between WRMSDs and workplace violence. Finally, a suggested model is presented in

Figure 1 to explain the interrelations among psychosocial risk factors, mental health, and violence.

4.1. WRMSDs and Psychosocial Risk Factors

The bivariate and multivariable analyses identified multiple psychosocial risk factors as significant correlates—or predictors—of WRMSDs. Notably, fear of job-related injury (ER10; r = .365, p < .001) and fear of verbal aggression (ED4; r = .357, p < .001) exhibited the strongest point-biserial correlations with WRMSDs, suggesting that perceived threat and insecurity at work substantially heighten musculoskeletal complaints. This finding aligns with literature which indicates that exposure to threatening work environments amplifies physical tension and muscular strain, thereby exacerbating WRMSDs [

1,

7,

25].

Beyond threat perception, lack of autonomy emerged as a robust predictor. Participants reporting “no opportunity to participate in decisions about my work” (AI4) had higher odds of WRMSDs (OR = 8.94, 95% CI = 1.717–46.562; p = .009), and “following a strict work schedule with no adjustments” (AI3; r = .265, p < .001) correlated positively with WRMSDs. Such associations mirror prior evidence that limited decision latitude fosters muscle tension and reduces opportunities for micro-breaks, both of which are known risk factors for musculoskeletal injury [

7,

18,

26].

On the other hand, some factors showed inverse associations. “Depending on colleagues to carry out my work” (WI2) was associated with lower odds of WRMSDs (OR = 0.228, 95% CI = .057–.922; p = .038). The idea that interdependence promotes social support and shared workload, which might reduce physical strain, is one tenable explanation [

18,

27]. However, where help from colleagues was absent (WR2), the likelihood of WRMSDs significantly rose (OR = 11.753, 95% CI = 2.305–59.939; p = .003), highlighting the importance of perceived (or real) social support as a modifier: its presence reduces the risk of WRMSDs, whereas its absence increases it.

Structural concerns regarding career progression (ER2; r = .177, p = .004), remuneration (ER3; r = .270, p < .001), and skill development (ER6) also predicted WRMSDs. In particular, “lack of opportunities to develop my professional skills” (ER6) conferred dramatically increased odds (OR = 33.532, 95% CI = 6.346–177.178; p < .001). These findings suggest that organizational dissatisfaction—manifested as perceived stagnation or under-utilization—leads to psychological strain that may manifest somatically as muscle tension or other musculoskeletal symptoms [

7,

18,

28].

Taken together, our results corroborate and extend earlier literature: high work intensity, limited autonomy, poor work relations, and structural frustrations each contribute to WRMSDs via psychological and behavioral pathways [

1,

7]. From an intervention standpoint, these psychosocial domains (e.g., autonomy, social support, resource adequacy) should be prioritized in efforts to reduce WRMSD incidence among nurses [

18,

29,

30].

4.2. WRMSDs and Mental Health (Anxiety Focus)

Mental health dimensions—particularly anxiety and stress—were strongly correlated with WRMSDs and remained significant predictors in multivariable models. The point-biserial correlation between anxiety and WRMSDs (r = .336, p < .001) was nearly identical to that for stress (r = .337, p < .001), while depression also showed a more moderate association (r = .280, p < .001). However, when analyzed the logistic regression only anxiety continued as an independent predictor (OR = 19.075, 95% CI = 2.434–149.468; p = .005): This indicates that anxiety may be the primary “mental health” driver of musculoskeletal complaints. This observation is consistent with some studies where were found that hospital nurses with comorbid WRMSDs and depression more frequently reported elevated anxiety levels, suggesting that anxiety both co-occurs and exacerbates musculoskeletal pain [

17,

31]. Another study documented that psychosocial risks at work (e.g., emotional demands, pressure) heighten anxiety, which in turn exacerbates physical discomfort [

18,

19]. Also, evidence shows that, physiologically, anxiety provokes increased muscle tension, altered posture, and hypervigilance—factors that directly increase the mechanical load on musculoskeletal structures [

4,

32].

Musculoskeletal pain may also feed back into anxiety, creating a bidirectional cycle: persistent pain creates anxiety by reducing functional capacity, promotes dramatization, and increases worry about job performance, fostering anxiety [

18]. Clinically, these data emphasize the importance of integrated interventions—combining cognitive-behavioral strategies to reduce anxiety with ergonomic adjustments—to break this cycle and mitigate WRMSDs [

17,

33,

34,

35].

Moderate and significant correlations were obtained between WRMSDs and both direct (physical, psychological) and indirect (vicarious) workplace violence (physical violence: r = .232, p < .001; psychological violence: r = .213, p < .001; vicarious violence: r = .260, p < .001). In the regression model WRMSDs were independently predicted by exposure to psychological violence (OR = 4.215, 95% CI = 1.476–12.045; p = .007) and vicarious violence (OR = 4.022, 95% CI = 1.436–11.037; p = .005). These findings are consistent with several authors who reported that nurses experiencing psychological or vicarious violence have higher levels of musculoskeletal pain. This is probably because of increased stress reactions, hyperarousal, and muscular defense [

15],

Furthermore, long-term exposure to workplace violence predisposes healthcare professionals to physical symptoms such as back and neck discomfort [

12]. Automatically, continuous sympathetic activation brought on by psychological violence (such as verbal abuse or bullying) and watching violence can result in muscle tension, decreased circulatory perfusion, and delayed recovery of tissue [

12,

15]. The results from this study are aligned with other studies that demonstrated that both experienced and vicarious violence contribute to emotional exhaustion and physical symptoms among nurses [

14].

Importantly, the absence of physical violence as an independent predictor in our multivariable model suggests that psychological and vicarious forms may exert a more pervasive, insidious effect on WRMSDs than outright physical assaults. This aligns with some studies, suggesting that psychological aggression often goes unrecognized and unaddressed, leading to chronic stress states that predispose individuals to musculoskeletal strain [

20]

Collectively, these data underline the critical need for violence prevention programs—addressing not only overt physical assaults but also psychological and vicarious exposures—to reduce WRMSD risk and improve overall well-being in healthcare settings [

12,

14].

4.3. Interrelations Between Psychosocial Risks, Mental Health, and Violence

Figure 1 depicts an explanatory model in which psychosocial risk factors, mental health (specifically anxiety), and workplace violence interact to influence WRMSDs. The model positions psychosocial risk factors (e.g., lack of autonomy, resource deficits, work-life conflict) as antecedent conditions that both directly increase WRMSD risk and indirectly exacerbate anxiety and exposure to violence. In turn, elevated anxiety and violence further amplify WRMSD risk.

Psychosocial Risk Factors → Anxiety: High emotional demands (e.g., handling others’ suffering, fear of aggression) and low decision latitude (AI4) precipitate anxiety [

18,

36]. For instance, nurses lacking clear guidance (WI6) reported significantly higher anxiety levels, consistent with other studies that found that unpredictability and conflicting instructions provoke worry and hypervigilance [

7,

37].

Psychosocial Risk Factors → Violence Exposure: Work-related stressors—such as high work intensity and insufficient resources—can foster interpersonal tensions that escalate into psychological violence [

23]. Some studies highlighted that environments lacking social support and clear communication bear higher incidences of bullying and aggressive behaviors [

4].

Anxiety → Violence: Being exposed to violence can cause anxiety as well as cause violence. Anxious workers may be more sensitive or hypervigilant, which can worsen interpersonal miscommunications and perceived threats and raise the risk of psychological aggression [

15]. On the other hand, psychological or vicarious violence exposure exacerbates anxiety through trauma-related pathways [

12,

38].

Mental Health and Violence → WRMSDs: This study’s findings indicate that psychological aggression (OR = 4.215) and anxiety (OR = 19.075) are both independent predictors of WRMSDs. This supports the idea of a psychosomatic pathway where exposure to violence causes chronic stress reactions that accelerate the degradation of the musculoskeletal system, while ongoing anxiety leads to muscle tension and abnormal postures [

15,

17,

38,

39,

40].

Psychosocial Risk Factors → WRMSDs: Even after controlling for anxiety and violence, several psychosocial factors (such as a lack of professional advancement opportunities (ER6) and a lack of support from colleagues (WR2)) continued to have a strong correlation with WRMSDs. This suggests that these risks also have a direct impact on musculoskeletal health, most likely through behavioral pathways (such as fewer micro-breaks or poor ergonomics) and increased muscle tension [

7,

18,

27,

28,

41].

In summary,

Figure 1 encapsulates a multifactorial framework: psychosocial factors not only elevate WRMSD risk directly (e.g., by fostering muscle tension and poor work behaviors) but also indirectly via increased anxiety and violence exposure. A self-reinforcing cycle is also created when violence and anxiety worsen WRMSDs. This concept is in line with some authors who promoted integrated strategies that successfully reduce WRMSDs by addressing both psychological and physical risk factors [

2,

42,

43].

4.4. Implications for Practice and Future Research

Our findings support that ergonomic interventions alone are insufficient to minimize or/and control WRMSD prevalence; comprehensive strategies must include psychosocial risk management, mental health support, and violence prevention. Specifically:

Psychosocial Interventions: Promoting decision autonomy (flexible scheduling, participatory decision-making) can reduce muscle tension and perceived stress [

7,

44]. Instituting regular team-based debriefings and peer-support programs may bolster social support, attenuating the detrimental effects of workload intensity [

45,

46,

47].

Anxiety Management: Onsite encouraging services, resilience training, mentoring programs, and mindfulness-based stress reduction programs can decrease anxiety, thereby disrupting the anxiety–WRMSD cycle [

48,

49,

50].

Future studies should evaluate the efficacy of such interventions in reducing both anxiety and WRMSD incidence longitudinally.

Violence Prevention: Implementing policies for zero–tolerance to psychological aggression and establishing reporting systems are critical. Training workers to recognize and de-escalate potentially violent confronts may reduce both direct and indirect violence exposure [

10,

12,

15,

51,

52].

Integrated Ergonomic-Psychosocial Programs: The underlying drivers of WRMSDs can be holistically addressed by customized interventions that integrate ergonomic assessments (e.g., safe patient-handling training) with psychosocial risk audits [

53,

54,

55].

5. Conclusions

This study clarifies a complex network of factors that contribute to WRMSDs in nurses: psychosocial risk factors (such as a lack of autonomy and inadequate resources) raise musculoskeletal complaints directly while also increasing anxiety and vulnerability to workplace violence, both of which raise the risk of WRMSDs on their own.

Figure 1 effectively integrates these pathways, illustrating that interventions must target psychosocial, mental health, and violence prevention dimensions concurrently to reduce WRMSD burden in healthcare settings. Due to the cross-sectional design, causal inferences are limited. Future studies should be supported by Longitudinal research to examine temporal dynamics among psychosocial risks, anxiety, violence exposure, and WRMSDs. Furthermore, qualitative research examining nurses' perceptions of the relationship between physical discomfort and professional pressures may clarify complex pathways that are not represented by quantitative measures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, PB. and CB.; methodology, PB and CB.; software, PB.; investigation, PB and CB.; writing—original draft preparation, PB and CB.; writing—review and editing, PB, PMS and CB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Fernando Pessoa University, with the reference FCHS/PI 219/21-2.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided informed consent to participate in this study and issues associated with confidentiality and anonymity were ensured keeping in mind the Data Protection Law Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (General Data Protection Regulation).

Data Availability Statement

Data Availability under request to the authors.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Not applicable.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

AI or AI-assisted tools were used to translate from Portuguese to English and to make some grammar corrections in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WRMSD |

Work-related musculoskeletal diseases |

References

- Graveling, R.; Smith, A.; Hanson, M. Musculoskeletal disorders: association with psychosocial risk factors at work Literature review; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; p. 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leka, S.; Jain, A.; Iavicoli, S.; Di Tecco, C. An Evaluation of the Policy Context on Psychosocial Risks and Mental Health in the Workplace in the European Union: Achievements, Challenges, and the Future. BioMed Research International 2015, 2015, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greggi, C.; Visconti, V.V.; Albanese, M.; Gasperini, B.; Chiavoghilefu, A.; Prezioso, C.; Persechino, B.; Iavicoli, S.; Gasbarra, E.; Iundusi, R. , et al. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baylina, P.; Barros, C.; Fonte, C.; Alves, S.; Rocha, Á. Healthcare Workers: Occupational Health Promotion and Patient Safety. Journal of Medical Systems 2018, 42, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzenetidis, V.; Kotsakis, A.; Gouva, M.; Tsaras, K.; Malliarou, M. Examining Psychosocial Risks and Their Impact on Nurses' Safety Attitudes and Medication Error Rates: A Cross-Sectional Study. Preprints, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietschert, M.; Bahadurzada, H.; Kerrissey, M. Revisiting organizational culture in healthcare: Heterogeneity as a resource. Social Science & Medicine 2024, 356, 117165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, J.; Barros, C.; Baylina, P. The influence of psychosocial risk factors on the development of musculoskeletal disorders. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças 2021, 22, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorce, P.; Jacquier-Bret, J. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorder Prevalence by Body Area Among Nurses in Europe: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Yin, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Cai, W. Prevalence of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among Nurses: A Meta-Analysis. Iranian Journal of Public Health 2023, 52, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangão, M.O.; Gemito, L.; Serra, I.; Cruz, D.; Barros, M.D.; Chora, M.A.; Santos, C.; Coelho, A.; Alves, E. Knowledge and Consequences of Violence Against Health Professionals in Southern Portugal. Nursing Reports 2024, 14, 3206–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, C.J.; van Zundert, A.A.J.; Barach, P.R. The growing burden of workplace violence against healthcare workers: trends in prevalence, risk factors, consequences, and prevention – a narrative review. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnavita, N.; Meraglia, I.; Viti, G.; Gasbarri, M. Tracking Workplace Violence over 20 Years. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Sastre, V. Workplace violence and intention to quit in the English NHS. Social Science & Medicine 2024, 340, 116458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.; Meneses, R.F.; Sani, A.; Baylina, P. Workplace violence in healthcare settings: work-related predictors of violence behaviours. Psych 2022, 4, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, C.J.; van Zundert, A.A.J.; Barach, P.R. The growing burden of workplace violence against healthcare workers: trends in prevalence, risk factors, consequences, and prevention: a narrative review. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-U.; Yoon, J.-H.; Won, J.-U. Reciprocal longitudinal associations of supportive workplace relationships with depressive symptoms and self-rated health: A study of Korean women. Social Science & Medicine 2023, 333, 116176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; ElGhaziri, M.; Nasuti, S.; Duffy, J.F. The Comorbidity of Musculoskeletal Disorders and Depression: Associations with Working Conditions Among Hospital Nurses. Workplace Health & Safety 2020, 68, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, C.; Baylina, P. Disclosing Strain: How Psychosocial Risk Factors Influence Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders in Healthcare Workers Preceding and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, V.; Pronzato, R. The emotional ambiguities of healthcare professionals’ platform experiences. Social Science & Medicine 2024, 357, 117185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, K.-A.; Kelloway, E.K. Violence at work: Personal and organizational outcomes. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 1997, 2, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour research and therapy 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.; Baylina, P. Stress and associated factors among nursing workers in pandemic times. In Occupational and Environmental Safety and Health IV. Stuides in Systems, Decision and Control, Arezes, P., Baptista, J. S., Melo, R., Barroso, M., Branco, J. C., Carneiro, P., Colim A., Costa N., Costa S., Duarte J., Guedes J., Perestrelo, G., Ed. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022, 449, 271–282.

- Marques, D.; S., S.I. Violência no trabalho: Um estudo com enfermeiros/as em hospitais portugueses. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho 2017, 17, 226–234. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J Anesthesiol 2019, 72, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Gonzalez, L.; Rodríguez-Suárez, J.; Llosa, J.A. A systematic review of the association between job insecurity and work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Hum. Factors Man. 2024, 34, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Molen, H.F.; Foresti, C.; Daams, J.G.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W.; Kuijer, P.P.F.M. Work-related risk factors for specific shoulder disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2017, 74, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyaerts, S.; Godderis, L.; Delvaux, E.; Daenen, L. The association between work-related physical and psychosocial factors and musculoskeletal disorders in healthcare workers: Moderating role of fear of movement. Journal of Occupational Health 2022, 64, e12314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezzina, A.; Austin, E.; Nguyen, H.; James, C. Workplace Psychosocial Factors and Their Association With Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Workplace Health & Safety 2023, 71, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolly, P.M.; Kong, D.T.; Kim, K.Y. Social support at work: An integrative review. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2021, 42, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsharian, A.; Dollard, M.F.; Glozier, N.; Morris, R.W.; Bailey, T.S.; Nguyen, H.; Crispin, C. Work-related psychosocial and physical paths to future musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs). Safety Science 2023, 164, 106177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Campo, M.T.; E., R.P.; E., d.l.H.R.; Miguel, V.J.; and Mahíllo-Fernández, I. Anxiety and depression predict musculoskeletal disorders in health care workers. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health 2017, 72, 39–44. [CrossRef]

- Hämmig, O. Work- and stress-related musculoskeletal and sleep disorders among health professionals: a cross-sectional study in a hospital setting in Switzerland. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2020, 21, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.; Baylina, P.; Fernandes, R.; Ramalho, S.; Arezes, P. Healthcare workers’ mental health in pandemic times: the predict role of psychosocial risks. Saf Health Work 2022, 13, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishi, E.; Osmani, H.; Aghaei, A.; Moloud, E.A. Hidden risk factors and the mediating role of sleep in work-related musculoskeletal discomforts. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2024, 25, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.O.S.; Cheng, S.-T. Effectiveness of physical and cognitive-behavioural intervention programmes for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0223367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Muñoz, A.; Antino, M.; León-Pérez, J.M.; Ruiz-Zorrilla, P. Workplace Bullying, Emotional Exhaustion, and Partner Social Undermining: A Weekly Diary Study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2020, 37, NP3650–NP3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Molen, H.F.; Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; H. W. Frings-Dresen, M.; Groene, G. Work-related psychosocial risk factors for stress-related mental disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034849. [CrossRef]

- Pauksztat, B.; Salin, D.; Kitada, M. Bullying behavior and employee well-being: how do different forms of social support buffer against depression, anxiety and exhaustion? International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 2022, 95, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudrias, V.; Trépanier, S.-G.; Salin, D. A systematic review of research on the longitudinal consequences of workplace bullying and the mechanisms involved. Aggression and Violent Behavior 2021, 56, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, K.; Torkelson, E.; Bäckström, M. Workplace incivility as a risk factor for workplace bullying and psychological well-being: a longitudinal study of targets and bystanders in a sample of swedish engineers. BMC Psychology 2022, 10, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhang, L.; Xu, C.; Qiao, J. Relationship Between the Exposure to Occupation-related Psychosocial and Physical Exertion and Upper Body Musculoskeletal Diseases in Hospital Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Asian Nursing Research 2021, 15, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gideon Asuquo, E.; Tighe, S.M.; Bradshaw, C. Interventions to reduce work-related musculoskeletal disorders among healthcare staff in nursing homes; An integrative literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances 2021, 3, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.G.; Kotowski, S.E. Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Disorders for Nurses in Hospitals, Long-Term Care Facilities, and Home Health Care: A Comprehensive Review. Human Factors 2015, 57, 754–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glauzy, A.; Montlahuc-Vannod, A. The voice of sacrifice: The silence of healthcare professionals in the service of productivity. The case of a French hospital. Social Science & Medicine 2025, 377, 118110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandall, C., J.; Danz, M.; Huynh, D.; Baxi, S.M.; Rubenstein, L.V.; Thompson, G.; Al-Ibrahim, H.; Larkin, J.; Motala, A.; Akinniranye, G., et al. Peer-to-Peer Support Interventions for Health Care Providers. Availabe online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA428-2.html (accessed on.

- Abdul Halim, N.S.S.; Mohd Ripin, Z.; Ridzwan, M.I.Z. Efficacy of Interventions in Reducing the Risks of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Workplace Health & Safety 2023, 71, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydorenko, A.Y.; Kiel, L.; Spindler, H. Psychosocial challenges of Ukrainian healthcare professionals in wartime: Addressing the need for management support. Social Science & Medicine 2025, 364, 117504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzler, A.M.; Helmreich, I.; Chmitorz, A.; König, J.; Binder, H.; Wessa, M.; Lieb, K. Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020, 10.1002/14651858.CD012527.pub2. [CrossRef]

- Hämmig, O.; Vetsch, A. Stress-Buffering and Health-Protective Effect of Job Autonomy, Good Working Climate, and Social Support at Work Among Health Care Workers in Switzerland. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2021, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohue, T.; Menta, M. Effectiveness of Mentorship Using Cognitive Behavior Therapy to Reduce Burnout and Turnover among Nurses: Intervention Impact on Mentees. In Nursing Reports, 2024, 14, 1026–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundey, N.; Terry, V.; Gow, J.; Duff, J.; Ralph, N. Preventing Violence against Healthcare Workers in Hospital Settings: A Systematic Review of Nonpharmacological Interventions. Journal of Nursing Management 2023, 2023, 3239640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, J.; Qin, Z.; Wang, H.; Hu, X. Evaluating the impact of an information-based education and training platform on the incidence, severity, and coping resources status of workplace violence among nurses: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Nurs 2023, 22, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, G.; Sala, E.; Albertelli, I.F.; Donatoni, C.; Mazzali, M.; Merlino, V.; Paraggio, E.; De Palma, G.; Lopomo, N.F. Musculoskeletal disorders and diseases in healthcare workers. A scoping review. WORK 2024, 79, 1603–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijkants, C.H.; van Hooff, M.L.M.; de Wind, A.; Geurts, S.A.E.; Boot, C.R.L. Effectiveness of a team-level participatory approach aimed at improving sustainable employability among long-term care workers: a randomized controlled trial. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 2025, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, K.; Yilmaz, S.; Karabay, D. Effects of Psychosocial and Ergonomic Risk Perceptions in the Hospital Environment on Employee Health, Job Performance, and Absenteeism. Healthcare 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).