1. Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are now the primary drivers of premature mortality worldwide, prompting a shift in health systems from episodic care to continuous, data-informed management. However, diagnosis remains inadequate, particularly in low-resource settings where laboratories, surveillance, and referral pathways are limited. These deficiencies lead to delays in detection, increased costs, and heightened inequities. In this context, Diabetes Mellitus (DM) and Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) emerge as critical indicators for examining how missed or delayed diagnoses influence health trajectories throughout the life course.

This work highlights the global and African burden of NCDs, then maps the comparative epidemiology of DM and SCD across African contexts and high-income countries. Additionally, it assesses the potential of AI-driven diagnostics, including machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models that utilize multimodal data, to facilitate earlier risk stratification, newborn and antenatal screening, and complication detection under real-world constraints such as limited computational resources and offline use. This study emphasizes the need for equity and safety, explainability, subgroup performance auditing, data governance, and human-in-the-loop workflows. Furthermore, the study highlights translation of these considerations into opportunities and challenges for aligning AI-enabled diagnostics with national strategies and the global response to NCDs.

This paper is organised into the following sections: introduction, related work, diagnostic infrastructure and screening gaps for DM and SCD in Africa versus high-income countries, ML and DL diagnostics for NCDs, ML and DL prospects and obstacles in Africa, policy implications and global health impact, summary, and conclusion.

1.1. NCDs Global Burden and African Disparities

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as cardiovascular diseases (CVD), cancers, diabetes mellitus (DM), sickle cell disease (SCD), and chronic respiratory diseases have emerged as the predominant health challenge in sub-Saharan Africa. [

1,

2]. Currently, these long-term conditions account for approximately 37% of all mortality in the region, up from 24% in 2000, indicating a significant transition in the epidemiological landscape. Projections suggest that by 2030, NCDs will surpass communicable diseases, as well as maternal, neonatal, and nutritional disorders, collectively becoming the leading cause of death. [

3,

4].

This epidemiological transition can largely be attributed to the increasing prevalence of risk factors associated with urbanization and lifestyle changes. [

5]. These include poor dietary practices, decreased physical activity, rising obesity rates, increased rates of comorbidities, hypertension, and heightened exposure to air pollution and various environmental hazards. The convergence of these factors underscores the urgent need for comprehensive public health strategies to address this emerging crisis [

3,

6].

The increasing prevalence of NCDs is placing a significant strain on already overburdened health systems across the African region. The current health infrastructure is poorly equipped to manage this shift: there is a considerable lack of awareness among both communities and healthcare providers, diagnostic capabilities are limited, and resources are disproportionately allocated to communicable diseases [

7,

8].

In sub-Saharan Africa, there is a notable shift in healthcare dynamics due to the escalating prevalence of NCDs, which are increasingly taxing limited healthcare resources [

9]. In Kenya, NCD-related hospital admissions have surged to approximately 50% of total bed occupancy, indicating a pronounced transition from care predominantly focused on infectious diseases to the long-term management of chronic conditions [

10,

11]. Similarly, Nigeria is experiencing a significant rise in NCDs, which account for roughly 29% of total mortality, with premature mortality rates among individuals aged 30 to 69 reaching 22%. As of 2022, hypertension is prevalent in nearly 40% of Nigerian adults over the age of 25, marking a significant rise compared to previous years [

5,

12,

13].

Recent data also indicate a concerning upward trend in diabetes prevalence, frequently coexisting with obesity, which now affects up to 22% of Nigerian adults. This intersection of conditions exacerbates the risks associated with cardiovascular diseases, stroke, chronic kidney disease, and high mortality, thereby highlighting the urgent need for strategic healthcare interventions and resource allocation focused on these chronic health challenges. These developments reflect shifting health patterns and highlight the urgent need for targeted interventions [

3,

12,

14].

Furthermore, not only in Kenya and Nigeria but also in several other sub-Saharan African countries, the economic impact of these chronic diseases is significant. High out-of-pocket expenditures, coupled with loss of productivity and the repercussions of long-term disability, exacerbate household financial vulnerability and contribute to widening health inequities across populations [

15]. Tackling these complex challenges requires not only improved clinical pathways but also strategic health policy interventions aimed at reducing economic burdens and enhancing access to comprehensive care [

2,

3].

National strategies, such as Kenya's incorporation of NCD services within primary healthcare frameworks and Nigeria's National Multi-Sectoral Action Plan (2019–2025), present effective blueprints for enhancing the prevention, early detection, and ongoing management of both metabolic and genetic chronic diseases. Furthermore, specialized initiatives such as the WHO PEN-Plus strategy for managing severe and chronic NCDs underscore the potential of targeted interventions. Nonetheless, to effectively curb the escalating NCD burden and its associated comorbidities across the region, it is imperative to ensure sustained financial investment, bolster surveillance mechanisms, and foster robust community engagement [

3,

12,

16].

1.2. AI-Driven Approaches for DM and SCD in the African Context

The application of artificial intelligence (AI) in NCDs such as diabetes and SCD management begins with sophisticated multimodal risk stratification. This process integrates routine clinical and laboratory data (such as HbA1c levels in DM and hemoglobin profiles in SCD), point-of-care outputs, imaging, and time-series data from mobile devices and wearables to generate calibrated probabilities for disease presence and complication risks [

17]. Recent reviews focusing on implementations in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) and telehealth workflows indicate strong technical performance, yet highlight significant gaps in implementation, particularly in workflow integration, workforce training, and patient follow-up [

18]. In diabetes care, validated algorithms for retinal imaging can enhance screening capabilities in low-resource settings, facilitating triage to specialist care and minimizing preventable vision loss [

19]. For SCD, ML models trained on longitudinal vital sign data and digital remote monitoring have been explored to predict vaso-occlusive crises, thereby enabling the prioritization of timely interventions. This indicates a transition from research prototypes to actionable clinical decision support systems [

20,

21].

Successful implementation in African contexts relies on offline-first strategies, favouring low-computation deployments with well-defined pathways linking AI-generated flags to clinical care. Practical design considerations include distilled and quantized models capable of running on entry-level mobile devices, bilingual user interfaces, and periodic synchronization with district servers [

22]. These approaches have been effectively piloted in related public health mobile systems and can be directly adapted for NCD screening. Recent literature in healthcare demonstrates increasing feasibility of an AI-driven approach, while also acknowledging challenges related to governance, dataset heterogeneity, and evaluation standards. [

23]. Benchmarking should assess not only accuracy metrics such as sensitivity at action thresholds, area under the ROC curve (AUROC), and F1-score, but also practical usability factors, including inference time, battery consumption, and safety parameters, such as calibration and the availability of human-in-the-loop overrides. Given the limitations of single-site datasets, federated learning presents a viable strategy for multi-centre model enhancement without necessitating raw data sharing [

24,

25,

26].

Equity and trust can be fostered through transparency and continuous monitoring. Explainable AI methods (XAI), such as feature attributes and Grad-CAM heatmaps for imaging data, can assist clinicians in interpreting AI outputs and enhance patient counselling. However, recent evaluations underscore the limitations of these techniques, highlighting the need for validation in medical contexts. [

27]. Following deployment, AI programs in Africa should implement regular audits of subgroup performance, monitor model drift, and ensure that AI thresholds align with national NCD strategies regarding referrals, confirmatory testing, and follow-up care. A comprehensive examination of AI in healthcare across African settings reveals both significant opportunities (increased access and reduced costs) and inherent risks (dataset bias and contextual misalignment). This reinforces the necessity for governance-by-design and community-centered implementation approaches. [

28,

29].

1.3. NCDs Comorbidities and Shared Risk Patterns

The coexistence of diabetes mellitus and sickle cell disease in sub-Saharan Africa presents a complex clinical dilemma, mainly due to shared pathophysiological mechanisms that involve vascular, renal, and metabolic pathways. SCD is notably prevalent in this region, accounting for over 75% of global cases [

30,

31]. The disease predisposes affected individuals to chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction, factors that also exacerbate the complications associated with diabetes. SCD possesses a distinct array of chronic comorbidities that overlap with those encountered in diabetes, particularly affecting the renal and cardiovascular systems. Sickle cell nephropathy can present with proteinuria, diminished glomerular filtration rate, or progress to end-stage kidney disease [

32]. Its pathophysiological characteristics parallel those of diabetic nephropathy, including glomerular hyperfiltration and progressive fibrosis. When these conditions coexist, the resulting interplay of ischemic tubular injury, hyperfiltration, and diabetic nephropathy can synergistically accelerate the progression of chronic kidney disease [

33]. Additionally, SCD is frequently linked to cardiovascular complications such as pulmonary hypertension, arrhythmia, cardiomyopathy, and stroke. These conditions further compound the risk for individuals with concurrent metabolic disorders such as diabetes, significantly heightening their overall risk profile [

32,

34].

Individuals with Sickle Cell Trait (SCT) or Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) may experience heightened susceptibility to diabetes-related complications due to the convergence of vascular and metabolic pathways. Research conducted in Senegal indicates that individuals with both type 2 diabetes (T2D) and SCT demonstrate a significantly higher prevalence of retinopathy, hypertension, and impaired renal function, alongside increased arterial stiffness and blood viscosity compared to T2D patients without SCT. [

31]. These observations imply that SCT may exacerbate microvascular dysfunction and inflammation, which are critical features of diabetic complications. The intersection of genetic predisposition and metabolic dysfunction underscores the importance of heightened vigilance in clinical management, including regular screening for metabolic markers and the implementation of personalized risk-assessment protocols. Healthcare providers treating diabetic patients in areas with high SCT prevalence should be particularly aware of the risk of accelerated end-organ damage [

31].

The intersection of renal and vascular complications in DM and SCD is significantly influenced by socio-economic and systemic factors endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. Access to continuous healthcare services is severely limited, exacerbated by high out-of-pocket expenses and inadequate integration of NCD management [

31]. This scenario contributes to delayed diagnoses and suboptimal therapeutic interventions for both conditions. The rising incidence of DM can be attributed to nutritional transitions, urbanization, and declining physical activity levels. Conversely, SCD persists as a condition with high mortality rates, mainly due to insufficient newborn screening programs and restricted availability of hydroxyurea [

35,

36]. Collectively, these dynamics impose a dual burden on health systems, necessitating long-term, multidisciplinary care for patients presenting with both DM-SCD services that are infrequently available at the primary healthcare level. To effectively tackle these comorbidities in the sub-Saharan context, there is an urgent need for the implementation of integrated chronic disease management programs, the expansion of WHO’s Package of Essential Noncommunicable Disease (PEN-Plus) services, and targeted research to assess the prevalence and health outcomes associated with the co-occurrence of DM and SCD [

5,

12,

37].

The complex interplay of comorbidities between SCD and diabetes highlights the critical necessity for integrated longitudinal care frameworks. This is particularly pressing in sub-Saharan Africa, where there is a simultaneous increase in the prevalence of genetic and metabolic NCDs.

2. Related Works

2.1. AI-Driven Diagnostics for DM and SCD

AI-driven diagnostics leverage ML and DL models to transform a variety of clinical signals, including symptoms, vital signs, laboratory results, medical imaging, and data from mobile or wearable devices, into calibrated risk scores. These scores facilitate earlier detection, triage, and referral processes [

38]. By discerning patterns across diverse data modalities, these systems can effectively scale screening efforts beyond specialist clinics, operate on cost-efficient edge devices, and provide standardized decision support in high-traffic clinical environments [

39]. Successful implementation requires rigorous external validation, precise calibration at clinically relevant thresholds, well-defined human-in-the-loop workflows, and continuous monitoring for performance drift. Additionally, robust measures for privacy, data governance, transparency, and subgroup fairness are essential to ensure reliable performance across different populations and devices [

40]. When these elements are synchronized, AI-enabled diagnostic tools can significantly broaden diagnostic access, minimize treatment delays, and enhance equitable health outcomes [

41].

The application of AI in diabetic retinopathy (DR) has emerged as a leading example of autonomous diagnostics, illustrating how ML and DL can extend non-communicable disease (NCD) screening beyond specialist settings. In 2018, IDx-DR (now LumineticsCore) [

42] received FDA clearance as the first fully autonomous medical AI for detecting more-than-mild DR within primary care environments, thereby setting a regulatory benchmark for subsequent systems. Prospective implementations in low- and middle-income countries have demonstrated the feasibility of scaling this technology, while advanced retinal foundation models like RETFound, trained on millions of images, enhance the generalization capabilities across diverse devices and populations [

43]. The recent FDA approval of a handheld fundus camera integrated with AI further emphasizes the evolving landscape toward portable, point-of-care screening options suitable for resource-limited environments [

44,

45].

In the context of SCD, evidence is emerging in the early stages but advancing rapidly. DL pipelines utilizing smartphone microscopy have achieved notable accuracy for automating sickle cell detection in peripheral blood smears, harbouring potential for low-cost screening where laboratory infrastructure is sparse [

46]. Complementary research is investigating non-invasive and remote monitoring techniques; pilot studies leveraging wearables [

47] Routine vital sign assessments aim to predict vaso-occlusive pain episodes, enabling earlier intervention and reduction of preventable hospital admissions [

20,

48]. These initiatives, including AI-assisted microscopy, image enhancement and segmentation, and time-series predictions from wearable data, form a practical research agenda aimed at translating lab-based prototypes into clinical decision support systems for outpatient and community care settings.

Effective implementation of these innovations within African health systems hinges on tailored implementation science and governance strategies. Key priorities encompass the development of offline-first, low-compute models suitable for entry-level mobile devices, external validation across diverse clinical sites and imaging devices, comprehensive calibration and subgroup audits (addressing variables such as age, sex, geography, and device specifications), and the establishment of clear “human-in-the-loop” escalation pathways aligned with national NCD guidelines [

49]. Global organizations have produced frameworks for evaluation and governance, including WHO’s directives on AI initiatives (particularly with large multimodal models) and the ITU/WHO AI4H framework, which prioritize safety, efficacy, bias mitigation, and post-deployment monitoring [

40]. Together, alongside the development of emerging portable, autonomous diagnostic tools for diabetes and SCD, these frameworks provide a foundational structure to align AI-driven diagnostics with adequate screening and referral strategies, thereby fortifying equitable responses to NCDs.

2.2. Epidemiological Overview of Diabetes Mellitus and Sickle Cell Disease

When evaluating the epidemiological trajectories of DM and SCD in Africa, one can observe both intersecting and divergent patterns that underscore a dual burden on healthcare systems. Sickle cell disease is predominantly prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, accounting for 75–80% of global cases due to high carrier rates, which can range from 10% to 40% in particular West African cohorts. This prevalence is exacerbated by inadequate access to early detection and disease-modifying therapies [

50,

51]. High-income countries, such as the United States and many European nations, have substantially decreased childhood mortality associated with SCD. This has been achieved through interventions like universal newborn screening [

36], penicillin prophylaxis, vaccination programs, and comprehensive specialized care. As a result, a significant number of patients are now able to live into middle age or beyond [

52,

53].

In contrast, the incidence of diabetes has seen a marked escalation in Africa over recent decades, with prevalence increasing from 6.4% in 1990 to 10.5% in 2022. Projections indicate that nearly 60 million adults could be affected by 2045. While diabetes has a more global distribution, its prevalence is heavily influenced by modifiable risk factors, including diet, physical inactivity, and obesity, amid increasing urbanization and economic transition [

54,

55].

In Nigeria, SCD is a prevalent genetic disorder, with mortality rates indicating that 70% to 90% of affected individuals do not survive past age five, primarily due to delays in diagnosis and insufficient access to healthcare resources [

56]. Concurrently, there is a rapid increase in the prevalence of DM, particularly T2D, contributing to its spectrum of microvascular complications, including retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy, as well as macrovascular issues like cardiovascular disease. The intersection of SCD and DM introduces significant clinical complexity. For instance, sickle nephropathy in SCD predisposes patients to glomerular injury and chronic kidney disease. In contrast, the presence of diabetic nephropathy can exacerbate renal deterioration and elevate the risk of progressing to end-stage renal disease [

57]. Furthermore, both SCD and DM are associated with vascular dysfunction, inflammatory processes, and tissue ischemia, which collectively amplify cardiovascular risk beyond the individual effects of each condition [

32,

58].

The burden of comorbidities faced by patients with SCD is considerably exacerbated by socio-demographic factors such as income level and access to healthcare, as well as systemic factors like healthcare discrimination and inadequate insurance coverage [

57]. Many of these individuals encounter stigma, socioeconomic disadvantages, and disruptions in educational access, all of which hinder their ability to obtain care, adhere to prescribed treatments, and engage in preventive health measures. Concurrently, the management of diabetes necessitates ongoing monitoring, pharmacological intervention, and lifestyle modifications, where these resources are often lacking in various Nigerian contexts [

13,

14]. Consequently, individuals grappling with both SCD and diabetes face a compounded healthcare challenge, characterized by an increased risk of organ complications and diminished quality of life. To effectively address this dual burden, it is imperative to develop integrated care models that encompass comprehensive screening, patient education, and support mechanisms for multimorbidity, specifically tailored to the constraints of sub-Saharan Africa's healthcare infrastructure and resource limitations [

59,

60].

Despite their etiological differences, both NCD conditions present with similar clinical symptoms. Both diseases necessitate sustained lifelong management and pose significant risks for severe end-organ complications, notably in the kidney, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular systems [

60,

61]. Moreover, both conditions confront considerable diagnostic and therapeutic deficits in Africa relative to high-income settings, characterized by late presentation, exorbitant out-of-pocket expenses, and fragmented chronic care services, all of which contribute to preventable morbidity and mortality. This intersection highlights the urgent need for strategies that integrate and appropriately address the challenges posed by both genetic and metabolic chronic diseases [

37].

Building on these findings, this research will demonstrate a comparative epidemiological analysis of these diseases, highlighting the urgent need for targeted interventions, addressing the inequities in non-communicable disease outcomes (especially DM and SCD), as well as the necessity of enhancing screening programs, expanding early intervention strategies, and investing in strengthening health systems, both in Africa and globally.

3. Diagnostic Infrastructure and Screening Gaps of DM and SCD in Africa versus High-Income Countries

3.1. Overview

In the context of diabetes management and sickle cell disease, a significant diagnostic capacity gap persists. Approximately 50% of the global population lacks adequate access to diagnostic services, a challenge particularly pronounced in low- and middle-income regions, including large parts of Africa [

31,

62]. This inadequacy stems from deficiencies in primary care laboratories, supply chain logistics, quality assurance systems, and workforce capabilities. The fourth edition of the World Health Organization’s Essential In Vitro Diagnostics List (WHO-EDL 4) identifies cost-effective diagnostic tests, such as glucose and HbA1c, appropriate for various care levels; however, the implementation of these recommendations is inconsistent [

63]. Consequently, there is substantial underdiagnosis in the African demographic, with an estimated 73% of adults with diabetes remaining undiagnosed [

62].

Furthermore, global spending on diabetes care remains disproportionately low, at roughly US

$10 billion. In contrast, high-income nations have integrated routine diabetes screening into primary care protocols. For instance, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for adults aged 35 to 70 years who are overweight or obese, supported by extensive access to HbA1c testing and quality-assured laboratory facilities [

64]. The shortage of reliable laboratory equipment and trained personnel highlights the critical requirement for enhanced diagnostic infrastructure in resource-limited regions. Improving these capabilities is essential for facilitating early detection and effective management of diabetes [

65].

In sub-Saharan Africa, over 75% of global newborn sickle cell disease (SCD) cases occur, yet national newborn screening (NBS) is rarely implemented outside of pilot programs [

66,

67]. This is concerning as early diagnosis significantly improves survival outcomes. While efforts, such as the American Society of Hematology’s Consortium on Newborn Screening in Africa [

68], aim to create sustainable NBS frameworks, challenges like financing and laboratory capabilities persist [

69,

70]. In contrast, high-income countries, like the U.S. and the U.K., have established universal NBS, allowing for timely SCD identification and effective care pathways for infants [

65,

71].

Therefore, Africa's elevated rates of undiagnosed DM and inconsistent screening for SCD underscore systemic diagnostic deficiencies rather than an actual scarcity of these conditions. To address this gap, it is essential to align national health policies with WHO-EDL. Additionally, investing in primary healthcare laboratories and implementing point-of-care testing for glucose, HbA1c, and hemoglobinopathy assessments, alongside scaling up national newborn screening (NBS) programs, represents an effective strategy to bridge the divide with high-income health care systems.

3.2. Diabetes Mellitus in Africa: Prevalence and Management Compared to Global Trends.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by persistent hyperglycemia resulting from impaired insulin secretion, diminished insulin action, or a combination of both [

62,

72]. This condition is linked to a wide array of complications, including but not limited to cardiovascular morbidity, chronic kidney disease, neuropathy, retinopathy, and an increased risk of infections [

73]. DM poses a major global health challenge, exacerbated by factors such as population aging, urbanization, dietary changes, and reduced physical activity. Its prevalence is rapidly escalating, underscoring the need for effective management strategies and interventions [

54,

74].

Over the past thirty years, the global prevalence of diabetes among adults aged 20 to 79 years has experienced a significant escalation, rising from approximately 7% in 1990 to 14% in 2022. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Diabetes Atlas 2025, 11.1% of the adult population, or about 1 in 9 individuals globally, are currently living with diabetes. Alarmingly, around 43% of these cases remain undiagnosed, which poses a considerable risk for the development of preventable complications and increases the likelihood of premature mortality [

62,

75].

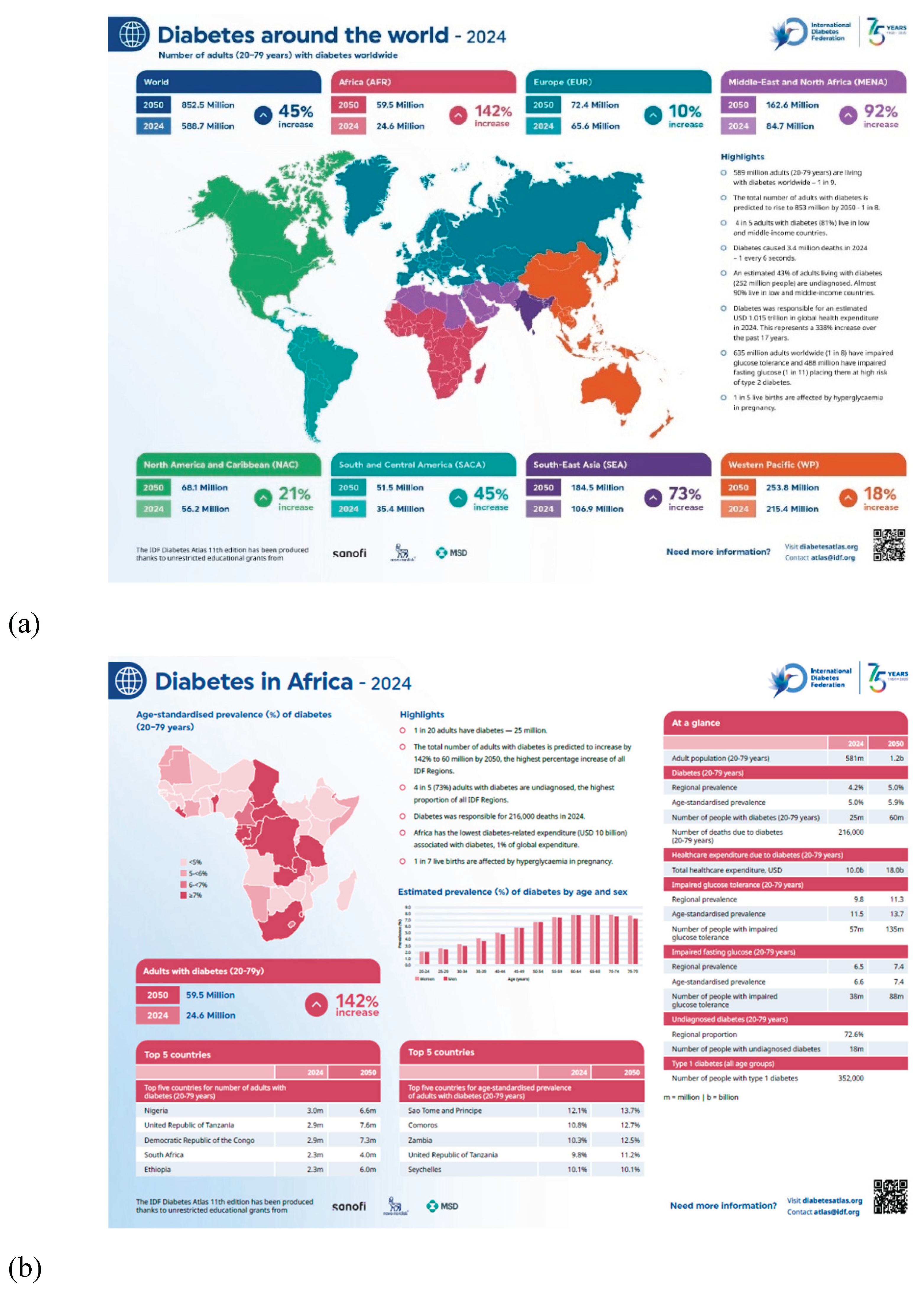

Figure 1(a) and (b) depict the 2024 position of diabetes across the globe and in Africa, as well as their respective projections for future prevalence rates.

In the African region, DM prevalence has surged from 6.4% in 1990 to 10.5% in 2022, driven by significant lifestyle changes and demographic shifts. As of 2024, it is estimated that approximately 24.6 million adults in Africa are living with diabetes, with projections indicating that this figure could rise to nearly 60 million by 2045 [

33,

76]. Furthermore, Africa exhibits one of the highest rates of undiagnosed diabetes globally, with estimates suggesting that up to 72% of cases remain unrecognized. This situation often results in delayed diagnoses and advanced complications, including renal failure, visual impairment, and increased cardiovascular risk [

62,

77].

In 2024, diabetes accounted for an estimated 216,000 fatalities across Africa; however, total health expenditure dedicated to managing the disease reached only USD 10 billion, constituting a mere 1% of global expenditure on diabetes. This significant disparity between the disease burden and financial resource allocation underscores the critical need for enhanced prevention, early detection, and management strategies that are specifically adapted to the unique health system challenges faced by the continent [

62,

74].

3.3. Diabetes Diagnostic Gaps, Strengths and Challenges in African Health Systems

Within the WHO African Region, awareness of diabetes remains disturbingly low, with only approximately 46% of individuals living with the condition aware of their status. This figure falls significantly below the 2030 global target of 80% diagnosed cases, highlighting systemic deficiencies in screening, laboratory infrastructure, and healthcare workforce capacity [

5]. A multi-country analysis of health research services categorizes many African nations as having limited capacity for effective diabetes management. Moreover, even after controlling for income levels and prevalence rates, the analysis reveals a disproportionate burden of diabetes-related mortality in these regions [

78].

Multiple barriers hinder progress in diabetes care, including overstretched primary care facilities, a shortage of trained professionals, and misconceptions about diabetes and insulin therapy. Many still rely on traditional remedies due to fears about treatment. Additionally, the affordability and accessibility of glucose testing, particularly self-monitoring strips, are significant obstacles [

79,

80]. The region also allocates the least funding for diabetes care globally, limiting access to essential diagnostics and supplies. These factors contribute to late diagnoses and an increase in diabetes-related complications [

62].

In OECD member states, guidelines for screening and advanced data management systems enhance early detection of diabetes and risk-factor monitoring. Electronic health records (EHRs) and national screening protocols help healthcare providers identify at-risk individuals. The USPSTF recommends using HbA1c or fasting plasma glucose assays for adults aged 35–70 who are overweight or obese, and this recommendation is supported by JAMA. Comprehensive registries and audit systems, like the National Diabetes Audit in England and Wales, combine primary and secondary care data to promote benchmarking and quality improvement [

64,

81].

The 2023 edition of OECD’s “Health at a Glance” includes a focused chapter on digital health, highlighting varying but generally high levels of readiness among member nations. This includes advancements in electronic health records and health-data governance, which are crucial for effective population health management and the prevention of complications. Together, these components, widespread screening, comprehensive registries, and a robust digital infrastructure, illustrate why high-income countries such as Sweden and Canada can detect diabetes at earlier stages and manage associated complications more efficiently compared to many low- and middle-income regions [

5,

81].

In Nigeria, the Federal Government of Nigeria has established a policy framework for diabetes and NCDs through the National Multi-Sectoral Action Plan 2019–2025 and corresponding guidelines. Implementation at the community level relies on civil society efforts, with interventions like training health workers and community screening led by organizations such as the World Diabetes Foundation and the Diabetes Association of Nigeria [

82].

In South Africa, the National Strategic Plan for NCDs (2022–2027) addresses diabetes, but access issues persist, particularly in rural areas. Community organizations play a crucial role in facilitating screening and education. Grassroots support groups have been active during the COVID-19 pandemic, while national coalitions and platforms provide essential resources [

55,

83].

Likewise, in Kenya, the National NCD Strategic Plan (2021–2026) emphasizes integrating chronic disease care into primary health systems. Collaborations with organizations such as the Kenya Defeat Diabetes Association have led to extensive awareness campaigns and the training of peer educators. The AMPATH program exemplifies an effective approach by integrating diabetes management across various levels of care, highlighting the importance of community networks in improving access to resources and supporting national policy efforts. Overall, these grassroots initiatives enhance healthcare delivery and bridge gaps in access and management of diabetes care [

84].

3.4. Sickle Cell Disease in Africa: Prevalence and Outcomes Compared to the Global Context

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an autosomal recessive blood disorder caused by mutations in the beta-globin gene, leading to the production of abnormal hemoglobin (HbS) [

85,

86]. Under low-oxygen conditions, red blood cells become sickle-shaped, which reduces their deformability and increases the risk of vaso-occlusive events, leading to microinfarctions and ischemia in various tissues [

34]. Patients often experience acute pain episodes and chronic complications from hemolytic anemia, including splenic dysfunction, increased infection risk, and damage to vital organs [

87]. Prompt diagnosis and effective management are crucial to reduce morbidity and mortality, particularly in early childhood when symptoms can be severe [

30,

88,

89].

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is a predominant hereditary NCD in Africa, where the continent bears over 75% of the global burden of the condition [

30]. In Nigeria, approximately 150,000 children are born with SCD each year, yet the infant mortality rate for those affected is alarmingly high, between 50% and 80%, due to factors such as delayed diagnosis, insufficient access to newborn screening programs, bone-marrow complications, and inadequate clinical care infrastructure [

5]. The presence of SCD alongside other chronic conditions, including diabetes, cancer, hypertension and renal disease, results in intricate comorbidity profiles necessitating ongoing, multidisciplinary management strategies [

59,

90].

SCD is a major public health challenge in sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for about 75-80% of the global disease burden, according to the 2021 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study [

50,

91]. As one of the leading genetic contributors to mortality in this region, the incidence remains alarmingly high, with over 300,000 infants diagnosed with SCD each year. The mortality rate among affected children is distressingly high, with estimates suggesting that between 50% and 80% succumb before reaching the age of five, primarily due to the lack of widespread newborn screening initiatives and insufficient access to comprehensive healthcare management strategies [

53,

92].

The prevalence of sickle cell trait carriers ranges from 10% to 40% in certain West African nations, contrasting with lower rates in East Africa [

50,

93]. This highlights the potential for vertical genetic transmission in these populations. In high-income nations like the U.S. and parts of Europe, universal neonatal screening and comprehensive care have significantly reduced childhood mortality rates and increased life expectancy for individuals with sickle cell disease, enabling many to live into middle age and beyond [

34,

52,

87].

3.5. Sickle Cell Disease: Universal Newborn Screening in Africa, Barriers to Implementation

Sub-Saharan Africa faces a significant public health challenge with the lack of universal newborn screening (NBS) for sickle cell disease (SCD), despite accounting for over 75% of global SCD births. This contributes to high under-5 mortality rates, with the WHO estimating that 50-80% of affected infants in Africa do not survive past age five. Recent pilot programs, like the ASH-CONSA network, tested nearly 74,000 blood samples across seven countries in April 2024. However, challenges such as sustainable financing and long-term follow-up remain. Integrating NBS into existing immunization and newborn care frameworks may offer a viable solution, necessitating strong policy and data management systems [

34,

66,

86]..

SCD’s studies on newborn screening in six African nations identified several systemic barriers, including weak governance, inconsistent funding, limited laboratory capacity, high staff turnover, and poor referral systems that disrupt care continuity. Demand-side issues, such as stigma and misconceptions about SCD, further hinder care-seeking behaviours [

94]. Despite this, families are generally receptive to NBS when programs are well-communicated and linked to services. The main challenges are structural rather than community resistance. Addressing these barriers will require coordinated investments in governance, laboratory networks, and community education through trusted channels [

69,

95].

High-income countries, like the US, UK, and several European nations, implement universal NBS for sickle cell, linking early identification to effective interventions such as prophylactic penicillin, immunizations, and hydroxyurea [

96]. These measures have significantly improved outcomes, with over 95% of children diagnosed with and receiving comprehensive care surviving to adulthood, despite challenges during the transition to adult services. The success of these programs highlights the importance of universal NBS and reliable access to treatments, providing a model for African programs as they enhance financing, laboratory capacity, and follow-up systems [

96,

97]

3.6. Diabetes and Sickle Cell: Shared Challenges and Key Differences

3.6.1. Laboratory Infrastructure

Many African health systems lack adequate laboratory networks, cold-chain capabilities and specimen-transport infrastructure for accurate diagnostics. The Lancet Commission on diagnostics in [

98], documented that nearly half the global population lacks access to diagnostics, with a major impact in low- and middle-income countries. Although a tiered, networked laboratory system is recommended, it remains uncommon in Africa. Regional efforts are promoting better lab management, but Hb1Ac testing remains inconsistent in rural LMICs. In contrast, high-income countries have robust quality-assured laboratory networks [

99,

100].

3.6.2. Governance and Policy

Africa faces challenges scaling up screening due to governance issues like poor diagnostic methods, weak health information systems, and limited integration of NCD services into primary care, for example, Kenya’s diabetes and hypertension screening [

101,

102], and Ghana’s SCD newborn screening [

68,

69,

98,

103]. Evaluation shows uneven progress and recommends standard chronic-care models [

53,

104]. In contrast, high-income countries employ robust data infrastructure and policy, such as the NHS’s newborn blood-spot program and integrated diabetes audits in England and Wales. OECD findings highlight strong digital health systems supporting registries, surveillance and population management [

81].

3.6.3. Training and Human Development

Diagnosis in sub-Saharan Africa is often affected by workforce shortages, including both laboratory staff and specialists such as endocrinologists and hematologists. Hematology perspectives note limited specialized resources for paediatric blood diseases, such as SCD, while reports from the WHO and Africa CDC identify shortages and uneven distribution of key healthcare roles [

105]. These factors contribute to delays in screening, diagnostic confirmation, and patient care. In contrast, high-income countries typically have structured laboratory support and specialist-led diagnostic pathways. For example, the NHS provides systematic SCT laboratory guidance to maintain consistent quality across prenatal and neonatal services [

106].

3.6.4. Funding and Sustainability

Many African diagnostic programs, including SCD newborn screening and early treatment, rely on external financing from initiatives like ASH's CONSA and the Bristol Myers-Squibb Foundation's partnerships, raising sustainability concerns after funding ends [

66,

81]. Broader studies show ongoing donor dependence and cross-country inequalities in health financing. The OECD reports that about 75% of health spending is public, with programmes like NHS neonatal screening centrally funded. High-income countries usually finance diagnostics via public budgets and mandatory insurance [

107].

4. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Diagnostics for NCDs

4.1. Diabetes Prediction and Detection: Methodology and Techniques

Recent evaluations of diabetes detection systems emphasize two primary design strategies that are commonly implemented in low-resource settings. The first strategy involves prioritizing non-laboratory, anthropometric, or symptom-based predictors to reduce costs and improve accessibility. The second strategy focuses on addressing class imbalance and managing high-dimensional feature spaces by employing techniques such as oversampling and dimensionality reduction before model training [

108]. These optimized pipelines consistently demonstrate enhanced discriminative power and improved calibration compared to naïve baselines, particularly in the context of limited clinical datasets [

109].

A recent study published in eClinicalMedicine conducted a comprehensive multi-ethnic development and validation of such tools, demonstrating that simple questionnaire-based assessments can reliably predict both prevalence and incidence of T2DM across various demographic groups [

110]. This approach offers a scalable, cost-effective strategy for population-level risk stratification, focusing on targeted confirmatory testing. Notably, the comparison between questionnaire-only models and those incorporating physical measurements or biomarkers showed that the former still maintained robust discriminatory power, thus endorsing their implementation in primary care settings and community outreach programs [

110,

111].

Recent advancements have embraced hybrid and ensemble methodologies, particularly stacking and voting, that synergize tree-based algorithms with DL architectures. These approaches have been shown to enhance performance consistency and decrease variance, particularly in datasets exhibiting characteristics akin to electronic health records [

110]. This study employs latent class analysis to evaluate countries' varying capacities to manage diabetes effectively. The research investigates whether management competencies in healthcare organizations are associated with changes in diabetes-related mortality rates and healthcare expenditures. It offers valuable insights that can inform policymakers in their decision-making processes [

78].

A comprehensive 2024 review by Modak and Jha [

112] synthesizes findings across a range of common learners, including SVM, RF, GB, and deep neural networks (DNN), and demonstrates that no single model consistently outperforms the others. Instead, performance is influenced by factors such as data curation, feature selection (like recursive feature elimination – RFE), and strategies to address class imbalance. The review highlights the growing use of hybrid and ensemble methods, such as stacking, voting, and gradient-boosted trees, often combined with deep feature extraction, to improve accuracy and calibration across diverse diabetes datasets. Recent open-access evaluations support this trend, indicating that ensembles, combined with thoughtful pre-processing techniques (such as resampling (SMOTE, ADASYN), feature selection, and thorough cross-validation), consistently surpass single baseline models and exhibit better generalization on noisy or incomplete clinical data [

113].

Recent advancements in sequence-aware architectures that integrate convolutional layers with recurrent neural network blocks have demonstrated impressive performance on benchmark diabetes datasets. For instance, the Convolutional Neural Network-Long Short-Term Memory network (CNN–LSTM) framework (DNet) achieved approximately 99.79% accuracy and 99.98% ROC-AUC during cross-validation [

114,

115]. Simultaneously, more streamlined DL models achieve competitive results when combined with effective explicit class-balancing techniques. A back-propagation neural network (BPNN) that utilized resampling methods attained an accuracy of about 89.8% on the PIMA dataset, which contains medical data for diabetes prediction [

108,

116]. The model achieved an impressive accuracy of approximately 95.3% when tested on the BIT Mesra dataset. This dataset is widely recognized as a standard benchmark for evaluating classification performance. This underscores that meticulous data management practices can yield results that rival those produced by more complex models.

In a study involving a three-class imbalanced dataset of Iraqi diabetes, a weighted multi-classifier ensemble was implemented, with hyperparameters fine-tuned through both grid search and Bayesian optimization. This ensemble approach significantly outperformed standalone classifiers, including k-Nearest Neighbour (k-NN), SVM, Decision Trees (DT), RF, AdaBoost, and Gaussian Naive Bayes [

111]. The resulting pipeline achieved nearly perfect discrimination (AUC ≈ 0.999) and high scores across accuracy, precision, recall, and F1. This underscores the critical importance of meticulous pre-processing, effective feature selection methods like Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR), and careful ensemble weighting, all of which are as vital as the choice of base learners in achieving optimal performance [

117,

118].

4.2. Sickle Cell Disease: Detection and Prediction

A revolutionary study revealed that an affordable smartphone-based microscopy system, integrated with a two-network DL framework, can effectively detect sickled erythrocytes in stained blood smears. The first neural network (NN) focuses on standardizing and enhancing image quality to a level comparable to benchtop microscopy (image normalization), while the second network conducts semantic segmentation and classification to ascertain SCD status at the patient level (image segmentation) [

46]. In a blind evaluation of 96 distinct smears (32 SCD-positive), the system achieved approximately 98% accuracy, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.998, highlighting its significant potential for implementation in resource-limited environments [

46,

119].

In a comparative analysis of pre-trained image classifiers applied to an identical SCD smear dataset, we observed significant variations in performance contingent upon architectural design and data characteristics. Inception V3 achieved a notable accuracy of 97.3%, while VGG19 followed closely at 97.0%; in contrast, ResNet50 lagged at 82%, all evaluated under consistent conditions [

120]. Additionally, transfer-learning assessments on the ErythrocytesIDB dataset corroborated the superior efficacy of VGG and ResNet architectures when appropriately fine-tuned for cytological images. This underscores the importance of dataset attributes and optimization strategies in shaping model performance [

120,

121].

A comparative transfer-learning analysis utilizing GoogLeNet, ResNet18, and ResNet50 identified ResNet50 as the highest-performing model for SCD image classification, achieving an accuracy of 94.9%. Notably, the study integrated Grad-CAM saliency mapping to elucidate the discriminative features on erythrocyte images, enhancing clinician confidence and facilitating error analysis in ambiguous cases [

122]. This approach represents a significant advancement toward the implementation of reliable decision support systems in hematology laboratories.

A systematic review conducted in 2024 examined ML applications in SCD focusing on diagnosis and outcome prediction, including organ failure risk, pain-crisis stratification, and treatment optimization. The review highlighted the efficacy of algorithms such as RFs, CNNs, and LSTMs, while underscoring the challenge posed by small and incomplete datasets, which limit the generalizability of findings [

123]. In a related study based in Senegal [

119] various algorithms were tested for their effectiveness in flagging likely SCD cases in newborns at birth, suggesting targeted screening pathways in regions without universal screening programs. Collectively, these studies illustrate the development of a sophisticated toolkit ranging from point-of-care imaging triage to early-life risk assessment [

124,

125].

A recent systematic review examines the role of ML models in improving the prediction, diagnosis, progression, and management of DM. It explores advancements in diabetes progression and prediction from 2016 to 2024, using diverse data sources, including clinical, genomic, and electronic medical records. Key applications discussed include risk prediction, glucose monitoring, complication detection, and personalized interventions, highlighting improvements in early detection and care strategies. The paper also addresses challenges such as data privacy, generalizability, and integrating various data sources. It emphasizes the need for model interpretability and external validation, advocating for solutions such as federated learning, differential privacy, IoT integration, and interoperable data systems to enhance diabetes care [

126].

4.3. Differences Diabetes Mellitus and SCD: Key Challenges and Limitations

4.3.1. Interpretability and Transparency of Small and Imbalanced Datasets

Several studies aimed at predicting diabetes still depend on small, retrospective cohorts and a limited array of public datasets, notably the PIMA Diabetes Database. This reliance on small sample sizes and unequal class distributions increases the risk of overfitting and limits external validity across different clinical contexts and populations. Recent reviews have emphasized the heterogeneous nature of study designs, the scarcity of prospective data, and the frequent lack of rigorous external validation, factors that can inflate apparent accuracy but are less applicable beyond the original dataset. Addressing these issues typically necessitates careful preprocessing, resampling, and feature selection; however, the reporting of these steps is often inconsistent [

127,

128].

For successful clinical implementation, predictive models must elucidate their driving factors and potential failure points. Current guidelines for diabetic retinopathy (DR) screening, arguably the most advanced application of ML in diabetes management, underscore the necessity for transparent workflows and clinician-facing interpretability. Recent studies have highlighted the effectiveness of SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) in enhancing the interpretability of DL models, facilitating robust error analysis. Systematic reviews further emphasize that explainability and rigorous reporting are essential prerequisites for the safe incorporation of these models into clinical care pathways [

43,

129,

130].

However, a prominent challenge in SCD image analysis research is reliance on small, bespoke datasets with class imbalance, which can artificially inflate accuracy metrics and compromise external validity. A recent systematic review examining ML applications for SCD underscores prevalent issues such as incomplete data, limited sample sizes, and heterogeneous methodological approaches, all of which exacerbate overfitting risks and complicate cross-site benchmarking efforts. The potential of smartphone microscopy for low-resource screening highlights these concerns. In their study, de Haan et al. [

46] reported high accuracy based on an analysis of just 96 smears. Conversely, this limited sample size raises important concerns about the reliability of their findings when applied across different laboratories, staining techniques, and patient demographics. Beyond the need for greater data volume and balance, the clinical uptake of these methods depends on transparency. Techniques like Grad-CAM provide pixel-level heatmaps that clarify the network's focus during analysis, thereby enhancing user understanding. Nonetheless, many existing systems remain opaque, which hinders clinician confidence and poses challenges for safe implementation in clinical settings [

131]

Therefore, advancements in ML and DL methodologies are significantly enhancing diagnostic capabilities for DM and SCD, with numerous models demonstrating accuracy exceeding 95% and AUC values approaching 1.0 in controlled experimental conditions. Techniques such as ensemble pipelines, hybrid NN architectures, and transfer learning are yielding remarkable results when applied to both structured health datasets and medical imaging. However, translating these technologies into real-world applications in African clinical settings is hampered by challenges such as insufficient datasets, resource constraints, and a notable lack of model explainability. Future research and development should focus on generating localised datasets, ensuring ethical algorithm design, and facilitating infrastructure-compatible deployment to effectively translate theoretical advancements in these algorithms into tangible health benefits for sub-Saharan African populations.

4.3.2. Infrastructure Barriers, Biases and Generalizability

Training cutting-edge AI models requires significant computing power, reliable electricity, and efficient data pipelines, resources which many facilities in sub-Saharan Africa currently lack. Although inference can be conducted on lower-cost devices, such as those used in edge deployments within screening workflows, ongoing usage hinges on the availability of robust optics and devices, connectivity for regular updates, and adequate maintenance support. Regional assessments of digital health readiness highlight these challenges and advocate for phased, context-sensitive deployments that are integrated with primary-care workflows rather than executed as isolated pilots [

43].

Performance degradation frequently occurs when ML models are applied across different hospitals, devices, or demographic groups, highlighting the domain shift challenge, particularly evident in DR classification and relevant to tabular models for diabetes risk assessment. Systematic reviews advocate multicenter, prospective validation studies and the incorporation of diverse training datasets to mitigate biases that affect underrepresented populations. Additionally, findings in domain generalization research underscore that tuning models on a single data source often fails to provide robust performance across varied environments. In the context of sub-Saharan Africa, it is crucial to utilize locally sourced and meticulously curated datasets, along with evaluations conducted on African cohorts, before scaling these models [

129,

132,

133].

High-performing convolutional models often require substantial computational resources during training, along with the need for strong device support for inference and ongoing maintenance. While mobile microscopy illustrates the feasibility of edge-based local inference, its sustained application hinges on the reliability of optics, the quality of staining, power availability, and the need for periodic recalibration [

46]. A key challenge lies in the generalizability of models across different populations. Even in well-established radiological applications, models developed in one healthcare setting frequently exhibit performance degradation when applied to external datasets due to domain shifts arising from variations in equipment, clinical protocols, and demographic factors [

134].

Recent research [

135] has highlighted the impact of cross-population domain shifts and demonstrated that model performance can be significantly enhanced by adapting development processes to African datasets. This highlights the crucial importance of localized training and validation before scaling applications. Furthermore, governance bodies emphasize the risks of bias and inequity that can be exacerbated by a lack of diverse data and insufficient accountability mechanisms. This reinforces the necessity for datasets that accurately reflect local demographics and mandates transparent reporting standards to ensure equitable and reliable model deployment [

40].

5. Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Africa: Prospects and Obstacles

5.1. Prospects for Digital Platforms and Health Systems Integration

5.1.1. Mobile-based screening and M-Health programs

Mobile technologies are revolutionizing lower-cost diagnostics and remote management of chronic diseases in sub-Saharan Africa. Recent trials and pilot studies focusing on diabetes have demonstrated that mHealth interventions, including SMS and app-based support, remote coaching, and teleconsultations, can lead to statistically significant reductions in HbA1c levels. However, it’s important to note that the studies conducted thus far are limited in number and exhibit considerable heterogeneity [

136]. In parallel, advancements in point-of-care image acquisition using smartphones have shown significant promise for rapid screening of SCD. A two-stage DL pipeline utilizing a smartphone microscope effectively standardizes smear images to a quality comparable to benchtop analysis and subsequently segments and classifies sickled cells. This method has achieved approximately 98% accuracy with an AUC of 0.998 across 96 distinct smears, underscoring its potential for implementation in rural screening workflows that are integrated with confirmatory testing [

46].

5.1.2. Alignment with the National Digital Health Strategy

Regionally, there is significant momentum underpinning policy development: the WHO African Region's framework for operationalizing the Global Strategy on Digital Health has established 2023 benchmarks for national strategy development, governance training, and the utilization of the Digital Health Atlas. According to the latest progress report, 38 Member States (approximately 81%) have successfully formulated a national digital health strategy, complemented by advancements in telemedicine and artificial intelligence capacity-building [

137]. However, notable implementation gaps remain. Many countries continue to grapple with fragmented systems, inadequate ICT infrastructure, and a paucity of detailed costed implementation plans. This highlights the imperative to convert strategic frameworks into actionable, funded execution roadmaps [

138].

5.1.3. Innovation Networks and Public-Private Collaboration

Innovation challenges and accelerators are instrumental in aligning startup initiatives with healthcare system priorities. The HealthTech Hub Africa (HTHA) 2024 Innovation Challenge has supported seven enterprises from Nigeria, Ghana, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania by providing catalytic funding and fostering public-private partnerships (PPPs). The collaborations aim to improve the scalability of interventions focused on enhancing access to care, elevating quality, and promoting client-centered services. This is particularly relevant in the context of digital solutions for addressing non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including diabetes and sickle cell disease (SCD). These programs provide mentorship, funding, and access to healthcare networks, ensuring startups focus on real-world systems challenges. The initiative exemplifies how PPPs can mitigate risks associated with pilot programs, ensure alignment with national health strategies, and facilitate the generation of robust evidence to support scaling efforts.

5.1.4. Wearables for Predicting Vaso-occlusive Crisis (VOC) in SCD

Platforms for remote monitoring that combine consumer wearables with sophisticated ML algorithms are improving early detection of complications associated with SCD [

139]. Recent studies indicate that longitudinal data, such as heart rate, activity levels, sleep metrics, and patient-reported outcomes, can effectively predict pain severity and the likelihood of vaso-occlusive crises (VOC) [

48]. This supports the implementation of proactive interventions and tailored care plans. Additionally, the feasibility of using biometrics collected from smartwatches in clinical settings has been validated. Although these findings are preliminary, they suggest a promising avenue for at-home risk stratification in conjunction with specialist follow-up care [

21].

5.2. Implementation Considerations: Constraints and Potential Vulnerabilities

5.2.1. Data Scarcity, Privacy and Sharing Constraints.

The scarcity of extensive, well-annotated clinical datasets from sub-Saharan Africa presents significant challenges for the external validation and generalizability of predictive models. Federated learning (FL) presents a promising solution by enabling model training across multiple institutions without requiring the exchange of raw data [

140]. However, the practical implementation of FL in this region faces several obstacles, including limitations in connectivity, variability in device capabilities, and communication overheads that can prolong training times and increase the likelihood of failures [

141]. These challenges are further exacerbated by the mobile internet usage gap and inconsistent broadband availability, complicating synchronization and updates necessary for effective collaboration across sites. To enable scalable, privacy-preserving partnerships, it is essential to enhance data stewardship, optimize federated learning algorithms for low-bandwidth environments, and invest in improving connectivity infrastructure [

142].

5.2.2. Ethics and Governance Frameworks

Prediction models intended for clinical application require stringent, transparent reporting standards and a phased evaluation approach. The TRIPOD-AI update offers standardized guidance for studies employing regression or ML methodologies [

143]. Concurrently, DECIDE-AI outlines essential reporting elements for early-stage, real-world assessments of decision-support systems, emphasizing the inclusion of human-factors considerations [

38]. Additionally, emerging research on digital health in Africa reveals how historical power imbalances influence data ownership, agenda-setting, and benefit-sharing. This underscores the critical importance of integrating fairness-aware design, fostering local stakeholder engagement, and ensuring accountability throughout the evaluation and scaling processes [

144].

5.2.3. Capacity and Workforce Challenges

Effective oversight of predictive analytics in healthcare requires collaboration between clinical champions and technical leaders. However, the region is grappling with significant workforce shortages. According to data from the World Bank and the WHO, sub-Saharan Africa has a considerably lower physician density than high-income regions. Furthermore, the WHO's African health statistics report highlights that the density of healthcare workers is below the thresholds required for achieving universal health coverage, which places immense pressure on healthcare services to manage chronic non-communicable disease (NCD) care in conjunction with advancing digital health initiatives [

145]. To navigate these challenges, it is crucial to develop cross-disciplinary expertise encompassing clinical informatics, biostatistics, and biomedical engineering. Additionally, institutionalizing continuous professional development will be vital for the safe implementation and adoption of these predictive tools in clinical settings.

5.2.4. Consideration regarding Infrastructure Limitations and Sustainability

Reliable access to electricity, computing resources, and internet connectivity is critical for the effective implementation of digital diagnostics and monitoring systems in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 50% of hospitals in sub-Saharan Africa lack a consistent electricity supply, while over 10% of healthcare facilities operate without any electricity. These deficiencies pose serious risks to device uptime, data integrity, and the efficacy of cold-chain reliant treatments [

137]. Similarly, other reports highlight significant gaps in mobile internet usage, which hinder telehealth services, model updates, and federated learning processes [

142]. Promising solutions include facility electrification, particularly through solar battery systems, and a strategic, phased deployment of connectivity-aware technologies. These initiatives have the potential to stabilize and enhance the operational frameworks for diabetes management and sickle cell disease programs.

5.2.5. Decentralization of Pilot Programs and Scale-Up Limitations

Despite successful pilot initiatives, achieving consistent national coverage for sickle cell disease newborn screening remains sporadic across Africa. CONSA has successfully demonstrated the feasibility of such screening in seven countries, conducting tens of thousands of dried blood spot tests [

58]. However, universal screening programs for SCD remain infrequent, often hampered by challenges related to funding, laboratory capacity, and inadequate longitudinal data systems [

69]. A recent qualitative review consolidating findings from various African contexts has identified common barriers to effective implementation: high costs, suboptimal record-keeping systems, weaknesses in supply chain management, and limited follow-up mechanisms [

66]. Moreover, recent case studies from specific regions, such as Kano in Nigeria, illustrate that strong local leadership can play a pivotal role in institutionalizing screening processes and improving linkage to care [

146]. To bridge the existing gap, it is essential to transition from pilot programs to comprehensive, costed national plans that establish clear indicators for screening coverage, turnaround times, and retention rates in care management.

5.3. Constrictive Strategy Recommendations for Sub-Saharan Africa.

5.3.1. Digital and Data Networks Enhancements

Enhancing national stewardship of digital health initiatives and improving cross-sector data infrastructure to facilitate the transparent, secure deployment of clinical decision-support systems. Recent progress reports from WHO-AFRO indicate a substantial adoption of relevant policies across the region; nevertheless, they also highlight critical gaps in funded implementation plans, interoperability capabilities, and governance capacity within health ministries. The African Union's Data Policy Framework provides complementary guidance, outlining expectations for shared data spaces, defined stewardship roles, and compliant data-flow mechanisms—essential to ensuring reliable analytics and audit trails. Collectively, these frameworks warrant strategic investments in leadership units, comprehensive catalogues of national health datasets, and transparent registers for model utilization to bolster trust and accountability in health informatics.

5.3.2. Prioritizing Local Data Generalization and Model Localization

To enhance clinical validity, it is essential to prioritize the generation of local data and the localization of models. African countries should invest in multicenter registries, such as maternal-newborn cohorts and clinics for diabetes and sickle cell disease, while also planning for privacy-preserving collaboration in scenarios where direct data sharing is impractical. Systematic reviews indicate that federated learning techniques can facilitate cross-site model training without the need to exchange raw data [

147]. Successful pilot implementations in Africa have demonstrated that this approach is viable even with bandwidth constraints; however, consistent connectivity and infrastructure challenges must be systematically addressed from the outset [

148]. Integrating these initiatives into the framework of learning health systems, which encompasses continuous feedback loops, model retraining, and external validation, will be critical for maintaining model performance over time [

149].

5.3.3. Promoting explainable and fair tools

Adoption of predictive models should hinge on robust explainability and thorough reporting standards. The TRIPOD+AI update outlines essential reporting standards for research that employs regression or ML techniques in predictive modelling. This ensures that studies adhere to a consistent framework, facilitating clarity and comparability in the reporting of findings. Additionally, the DECIDE-AI guidelines emphasize the necessity of comprehensive early clinical evaluation reporting, assessments of human factors, and safety [

38,

143] [

150]. There is growing concern about historical power imbalances that may affect governance and benefit-sharing related to the implementation of AI technologies in Africa. This issue is highlighted in a growing body of literature that warns against the potential negative impacts these imbalances could have on equitable distribution and oversight in the technological landscape. This highlights the imperative for fairness audits and structured community engagement efforts, alongside achieving technical interpretability through methods such as SHAP and Grad-CAM, before any large-scale implementation.

5.3.4. Ensuring Alignment of Diagnostics Tools with Real Workforce

Regarding diabetes management, findings from trials and systematic reviews conducted in Africa suggest that mHealth interventions can significantly lower HbA1c levels and enhance follow-up adherence when embedded within primary care and community health worker (CHW) networks. The integration facilitates essential functions, including patient referrals, medication titration in accordance with established protocols, and continuous monitoring of patient outcomes over time [

151]. In the context of sickle cell disease (SCD), smartphone-based microscopy systems demonstrate exceptional efficacy in triaging smears at the point of care, achieving high discrimination rates. The real value of these systems emerges when results are combined with verified diagnoses, penicillin prophylaxis, vaccination initiatives, and the availability of hydroxyurea. This integration is particularly effective within decentralized care models, such as PEN-Plus [

46,

136,

152].

5.3.5. Promoting Effective Communication between Pilots and Policy Makers

To successfully expand promising initiatives, it is essential to incorporate them into national strategies. This integration should include detailed financial plans, standardized measurement indicators, and firm commitments to ensure the integrity of supply chains. Notable recent collaborations involve Texas Children’s Global HOPE, Baylor Global Health, and the Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation, which are actively implementing comprehensive sickle cell disease (SCD) programs in Tanzania and Uganda. These programs specifically focus on embedding newborn screening and early intervention protocols within primary care frameworks, with plans for geographic expansion. Concurrently, the ASH’s CONSA network is actively validating multi-site newborn screening and establishing care linkages across seven countries. This generates a robust evidence base that governments can leverage to formalize national newborn screening (NBS) frameworks and chronic care policies, ultimately enhancing health outcomes for affected populations [

63,

105].

Africa offers a promising environment for the implementation of machine learning and deep learning-based diagnostics in managing diabetes and SCD. The potential for advancements is bolstered by the growth of mobile health (mHealth), the availability of wearable technology data, and the presence of local innovation hubs. However, to fully capitalize on these opportunities, several significant challenges must be addressed. These include insufficient data, infrastructure barriers, workforce shortages, and the risk of algorithmic bias. To achieve lasting improvements in NCD care and promote equity, it is crucial to invest strategically in governance, develop effective data strategies, build capacity, and foster sustainable collaborations between the public and private sectors

6. Policy Implications and Global Health Impact

6.1. Guidelines for Fairness in Diagnostics Practices

Equitable diagnostics within African health systems necessitate a design approach that prioritizes fairness, contextual relevance, and community empowerment. It is imperative that models and workflows actively address historical structural inequities to prevent the perpetuation of extractive or apathetic power dynamics. Equity encompasses more than mere diagnostic accuracy; it demands the inclusion of representative datasets, genuine accessibility for marginalised populations, cultural and linguistic sensitivity, and clear, actionable communication for both patients and healthcare providers.

Furthermore, there must be an equitable distribution of benefits across diverse communities and institutions. These principles should permeate all phases of the diagnostic process, ranging from problem identification and data acquisition to validation, implementation, and ongoing oversight.

6.2. Inclusive Design: Enhancing Accessibility and Expanding Reach

Effective practical access to health services depends on developing tools and systems that align with the realities of service delivery. Affordable, offline-first diagnostic solutions tailored for low-end devices can facilitate rapid test interpretation by minimally trained personnel in remote healthcare settings. This is particularly effective when diagnostic methods are integrated with clear referral and treatment pathways, such as triage for sickle cell disease connected to newborn screening, penicillin prophylaxis, and hydroxyurea accessibility, or diabetes risk assessment tools that incorporate follow-up from community health workers.

Co-designing these tools with local health workers, patients, and caregivers is crucial to ensure that interfaces, languages, and workflows are appropriate for actual usage contexts. Failing to engage in this process can lead to low adoption rates and unintended biases. Additionally, expanding capacity is essential alongside the implementation of these tools; comprehensive training programs for laboratory scientists, nurses, clinicians, and data stewards in data literacy and informatics are vital.

Furthermore, employing privacy-preserving collaborative methods, such as federated or distributed learning, enhances model performance without exchanging raw data. Addressing the challenges of varying bandwidth, device compatibility, and maintenance capacities is essential. This necessitates intentional design and engineering efforts to ensure effective solutions. Establishing regional initiatives and networks, such as integrated laboratory systems, innovation hubs, and cross-border partnerships, can effectively pool expertise and standardise quality while ensuring governance remains locally managed.

6.3. Strategic Framework for Governance, Financial Structuring and Accountability for Scalable Solutions

Equity in health systems necessitates the establishment of robust governance frameworks, supported by consistent resources and well-defined measurable outcomes. Governance practices must be infused with communal ethics, such as Ubuntu, alongside inclusive, participatory processes that engage all stakeholders —communities, frontline workers, clinicians, ethicists, and policymakers —in setting risk thresholds, designing user interfaces, formulating escalation and referral protocols, and establishing data stewardship norms.

Infrastructure investments must align with the realities of rural power and connectivity, incorporating decentralized laboratories, edge computing, and portable battery-operated devices. Moreover, addressing data equity is critical; it entails creating African-representative datasets that are validated locally across diverse populations.

Sustainable financing models should integrate public budgets, philanthropic contributions, and private capital to foster local innovation while mitigating risks associated with vendor lock-in and preserving sovereignty in contracts. Continuous accountability mechanisms are essential to ensure a feedback loop; routine equity audits should be conducted to assess beneficiary demographics, identify areas of suboptimal uptake, and evaluate improvements in health outcomes, such as reduced infant mortality rates related to Sickle Cell Disease (SCD), earlier diagnosis of diabetes, and enhanced follow-up procedures.

Key metrics to assess progress should include outreach effectiveness in rural and low-income areas, disaggregated performance data by region, gender, and age, levels of user trust and understanding, and documented community feedback that informs ongoing iterative improvements.

7. Summary and Conclusion

7.1. Summary